Ethical nonnaturalism Michael Lacewing enquiriesalevelphilosophy co uk Michael

- Slides: 12

Ethical non-naturalism Michael Lacewing enquiries@alevelphilosophy. co. uk © Michael Lacewing

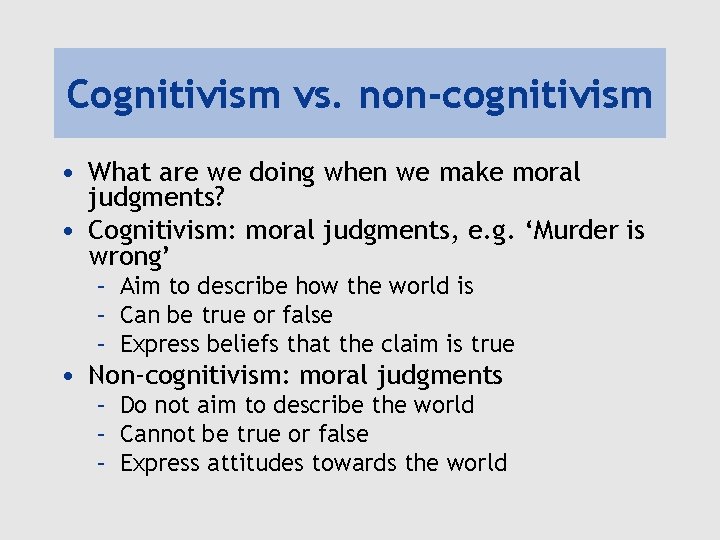

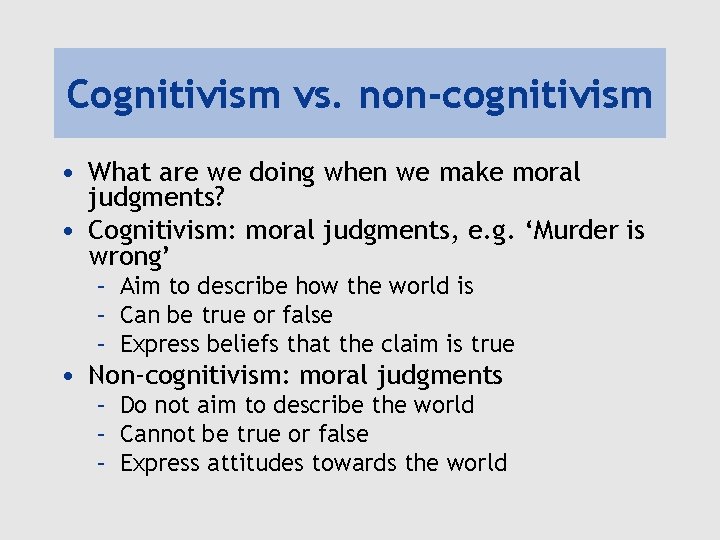

Cognitivism vs. non-cognitivism • What are we doing when we make moral judgments? • Cognitivism: moral judgments, e. g. ‘Murder is wrong’ – Aim to describe how the world is – Can be true or false – Express beliefs that the claim is true • Non-cognitivism: moral judgments – Do not aim to describe the world – Cannot be true or false – Express attitudes towards the world

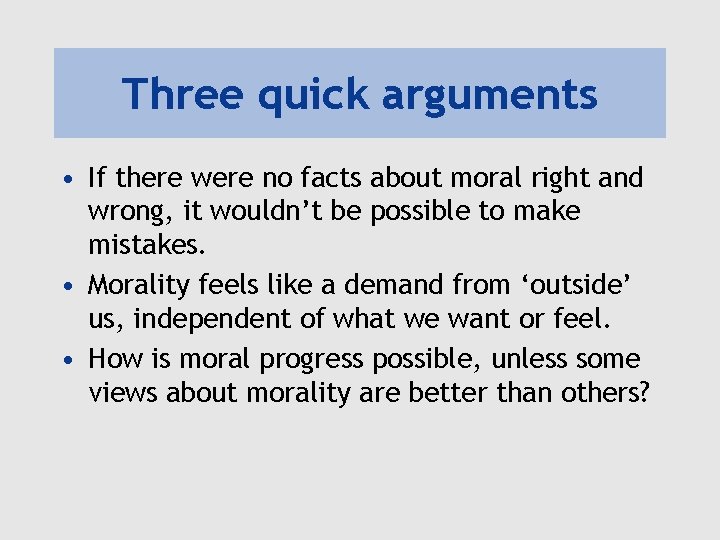

Three quick arguments • If there were no facts about moral right and wrong, it wouldn’t be possible to make mistakes. • Morality feels like a demand from ‘outside’ us, independent of what we want or feel. • How is moral progress possible, unless some views about morality are better than others?

Types of realism • Moral realism: good and bad are properties of situations and people, right and wrong are properties of actions • Moral judgements are true or false depending on whether they ascribe the moral properties something actually has • What is the nature of these properties?

Moore on the ‘naturalistic fallacy’ • Moral properties, e. g. good, may be correlated with certain natural properties, e. g. happiness – But they are not identical • Goodness is a simple, unanalyzable property – Cp. ‘yellow’ – can’t be defined, even in terms of wavelengths of light – To identify good with any natural property is the ‘naturalistic fallacy’ • Unlike colour, goodness can’t be investigated empirically – it is a ‘non-natural’ property

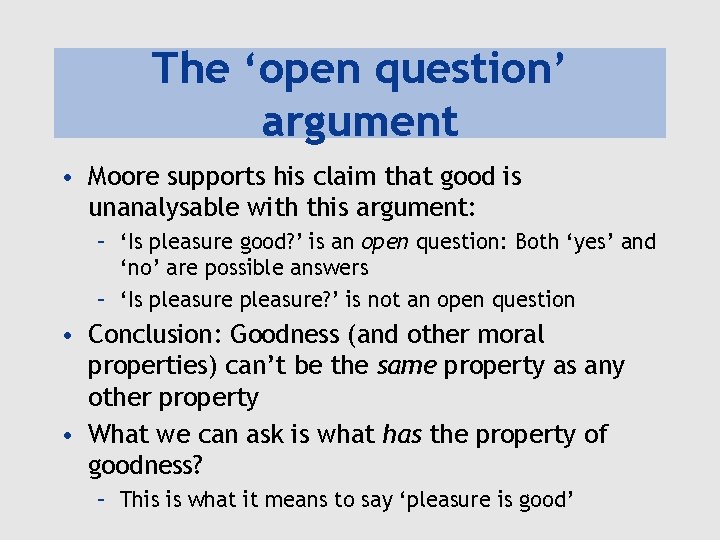

The ‘open question’ argument • Moore supports his claim that good is unanalysable with this argument: – ‘Is pleasure good? ’ is an open question: Both ‘yes’ and ‘no’ are possible answers – ‘Is pleasure? ’ is not an open question • Conclusion: Goodness (and other moral properties) can’t be the same property as any other property • What we can ask is what has the property of goodness? – This is what it means to say ‘pleasure is good’

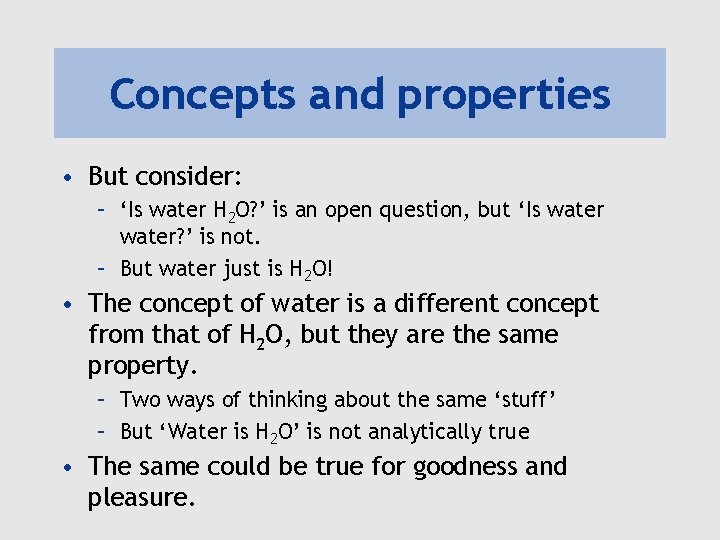

Concepts and properties • But consider: – ‘Is water H 2 O? ’ is an open question, but ‘Is water? ’ is not. – But water just is H 2 O! • The concept of water is a different concept from that of H 2 O, but they are the same property. – Two ways of thinking about the same ‘stuff’ – But ‘Water is H 2 O’ is not analytically true • The same could be true for goodness and pleasure.

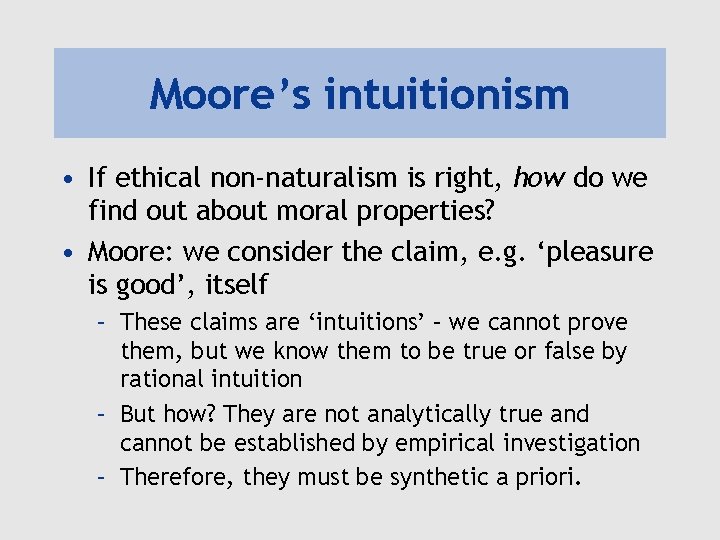

Moore’s intuitionism • If ethical non-naturalism is right, how do we find out about moral properties? • Moore: we consider the claim, e. g. ‘pleasure is good’, itself – These claims are ‘intuitions’ – we cannot prove them, but we know them to be true or false by rational intuition – But how? They are not analytically true and cannot be established by empirical investigation – Therefore, they must be synthetic a priori.

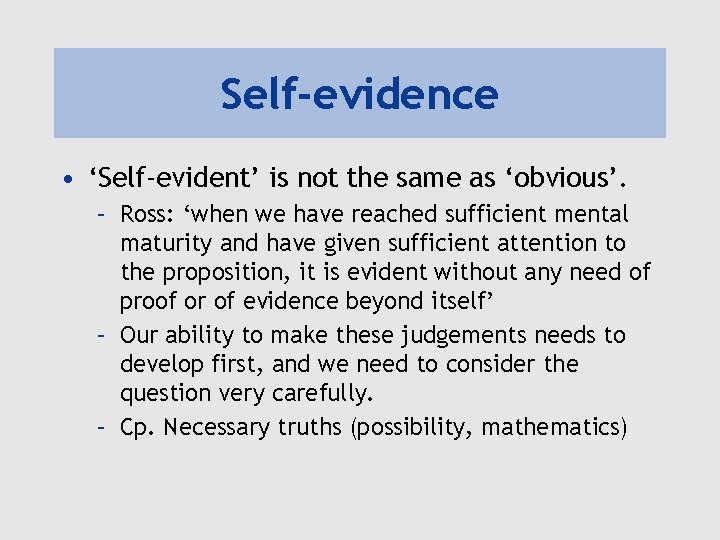

Self-evidence • ‘Self-evident’ is not the same as ‘obvious’. – Ross: ‘when we have reached sufficient mental maturity and have given sufficient attention to the proposition, it is evident without any need of proof or of evidence beyond itself’ – Our ability to make these judgements needs to develop first, and we need to consider the question very carefully. – Cp. Necessary truths (possibility, mathematics)

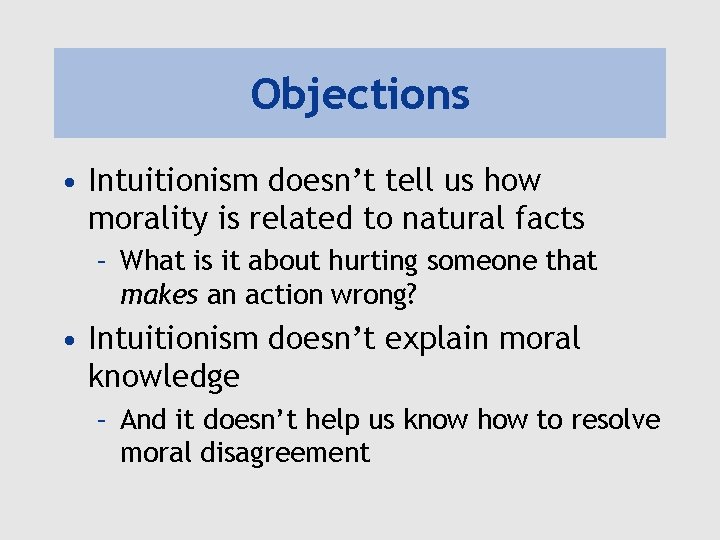

Objections • Intuitionism doesn’t tell us how morality is related to natural facts – What is it about hurting someone that makes an action wrong? • Intuitionism doesn’t explain moral knowledge – And it doesn’t help us know how to resolve moral disagreement

Development • Suppose we could give reasons for thinking that pleasure is good, e. g. because it forms part of a flourishing life for human beings. Is it self-evident that being part of a flourishing life makes something good? • If not, we need to give a further reason for this judgment. And we can ask the same question of any further reason we give.

Reflective equilibrium • Alternatively, we reject self-evidence – All moral judgments are supported by other beliefs that we must consider – This repeats for those other beliefs – All reflection on what is good occurs within a framework of reasons • We justify our judgments by balancing judgments in individual cases and general moral beliefs to reach ‘reflective equilibrium’

Michael lacewing

Michael lacewing Michael lacewing philosophy

Michael lacewing philosophy Michael lacewing

Michael lacewing Michael lacewing

Michael lacewing Michael lacewing

Michael lacewing Michael lacewing

Michael lacewing Indivisibility argument for substance dualism

Indivisibility argument for substance dualism Lacewing trial

Lacewing trial Ethical lenses army

Ethical lenses army Chapter 4 business ethics and social responsibility

Chapter 4 business ethics and social responsibility Ethical decision making and ethical leadership

Ethical decision making and ethical leadership Perbedaan ethical dilemma dan ethical lapse

Perbedaan ethical dilemma dan ethical lapse Kode etik desainer

Kode etik desainer