ESTONIAN AMONG THE LANGUAGES OF EUROPE HELLE METSLANG

- Slides: 53

ESTONIAN AMONG THE LANGUAGES OF EUROPE HELLE METSLANG IN TE RNATIONAL CO NFERENC E ON F INNO-UGRIC LANGUAGES UN IVE RSITÀ DI BO LOGNA , 1. 3. 2018 1

Emakeele Selts (Mother Tongue Society ) • Was founded at the University of Tartu in 1920 • Joined the Academy of Sciences in 1946 • Mission to promote the use, teaching and research of the Estonian language in Estonia and abroad • Main activities : oscholarly communication opopularization of linguistic knowledge opublication of research and language materials (yearbook, books, popular journal Oma Keel) olanguage management

Outline • Estonian in myths and facts • Estonian as a Finnic language • Estonian and common features of European languages • Estonian as a language of the Circum Baltic area 3

Estonian in myths: language beauty contests in Europe and Estonia A legend: once upon a time Estonian won the second prize after Italian at the beauty contest of European languages with the sentence Sõida tasa üle silla ‘Ride slowly across the bridge’. In 2008 a contest of the most typical and beautiful sounding Estonian sentence, the winner: Ema tuli koju ‘Mother came home’

Is Estonian a difficult language? There is a myth that Estonian is a difficult language to learn. It is true that e. g. 14 cases or object case alternation makes Estonian different from the Indo European languages, which learners are mostly familiar with. However, the main categories, lexicalization and grammaticalization processes, and the abundance of loan vocabulary blend Estonian into the European context. Categories e. g. : number, case, tense, mood, voice, person; syntactic functions (subject, predicate, etc. ) Vocabulary: borrowings (via German, Russian or English) from Latin: protsent (< pro centum), fookus (focus), punkt (punctum) from Italian: karussell, kastan, klarnet, kuppel, salat, salong, valuuta (cf. carosello, castagna, clarinetto, cupola, insalata, salone, valuta)

Is Estonian a small and disappearing language? By the number of speakers (about 1 million), Estonian belongs to the top 6% of the world’s languages Estonian is the official language of the Republic of Estonia (from 1919), protected by the constitution, language law and the development plan of the Estonian language Estonian is used in all spheres of public and private life The Estonian language is among the • 200 national languages • 50 languages of higher education • 30 languages with language technology • 24 official languages of the European Union.

The development of Estonian evolved into an independent language between the 13 th 16 th centuries: common changes in the local tribal dialects resulted in the formation of the common language Estonian was influenced by various Germanic, Baltic and Slavonic languages. This is proved e. g. by multiple loan words. German influence in the 13 th 19 th century (the upper class were Germans) Standard Estonian started to take shape in the 16 th– 17 th centuries, it was mostly developed by the German clergy

Estonian as a Finnic language Estonian belongs to the Finnic group of the Finno Ugric language family Other Finnic languages: Finnish, Livonian, Vepsian, Votian, Karelian, Izhorian

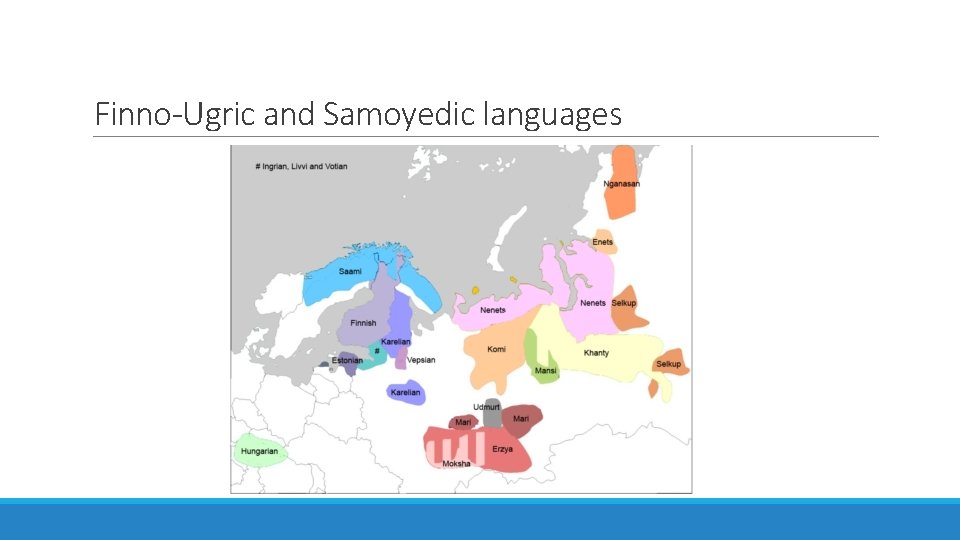

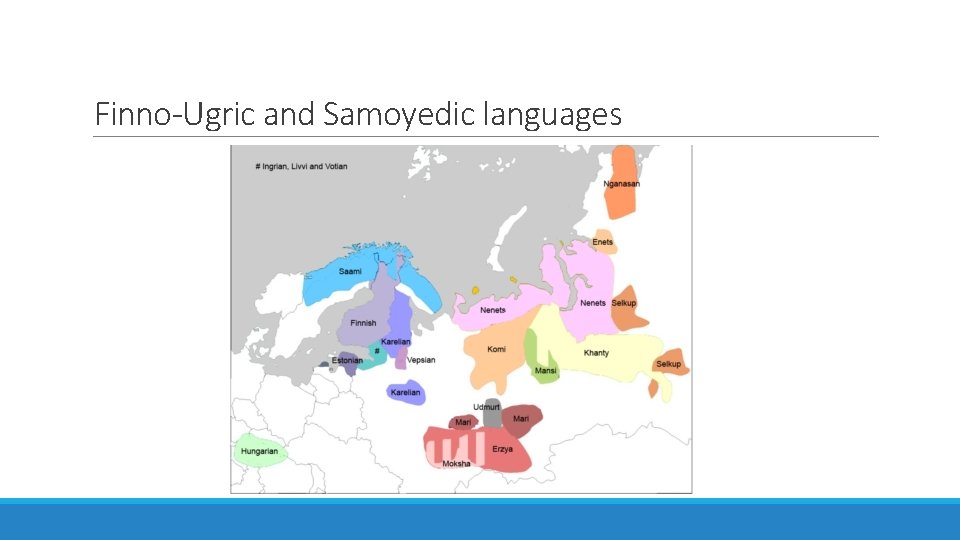

Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic languages

Some Finnic features in Estonian 1 o. Large number of cases (14 productive cases) o. Grade alternation (tuba: toa: tuba ‘room’ N, G, P cases) o. No articles (either definite or indefinite) o. No grammatical gender either of nouns or personal pronouns. (As the pronoun tema can refer to both men and women (and even to a thing), an Estonian speaker does not face problems of political correctness as do those who speak Indo European languages) Possessive construction with the auxiliary ‘be’ Perfect and pluperfect with the auxiliary ‘be’ (on elanud, oli elanud ‘has/had lived’)

Some Finnic features in Estonian 2 Alternation between total and partial forms ◦ In objects: ostsin raamatu / raamatut ‘I bought/was buying a book’ ◦ In subjects: vanaemal on hallid juuksed / halle juukseid ‘grandma has gray hair’ ◦ In adverbials: olen siin töötanud aasta / aastaid ‘I have worked here for a year/years’ ◦ In nominaal predicates: ta on mu parim sõber / mu parimaid sõpru ‘she is my best friend/one of my best friends' No accusative case – the object can be in the partitive, genitive or nominative case

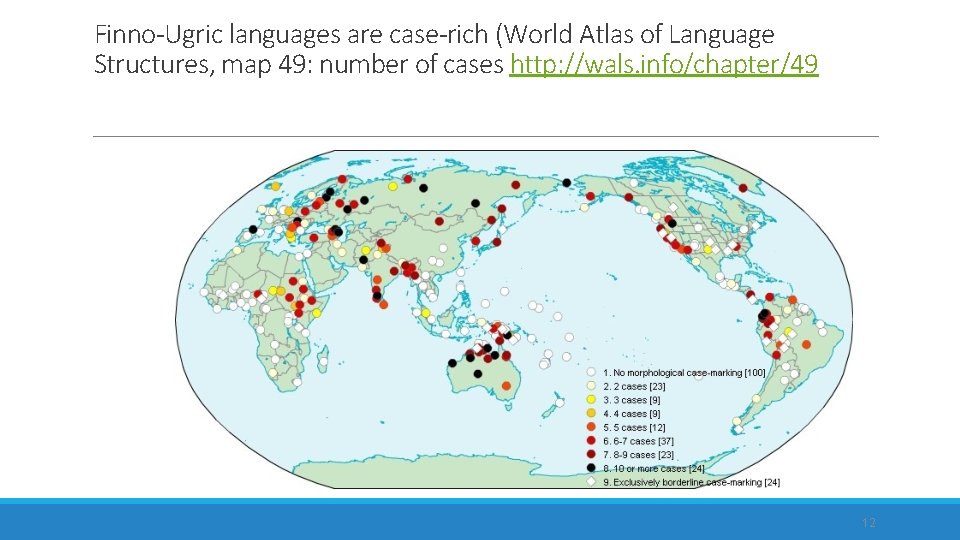

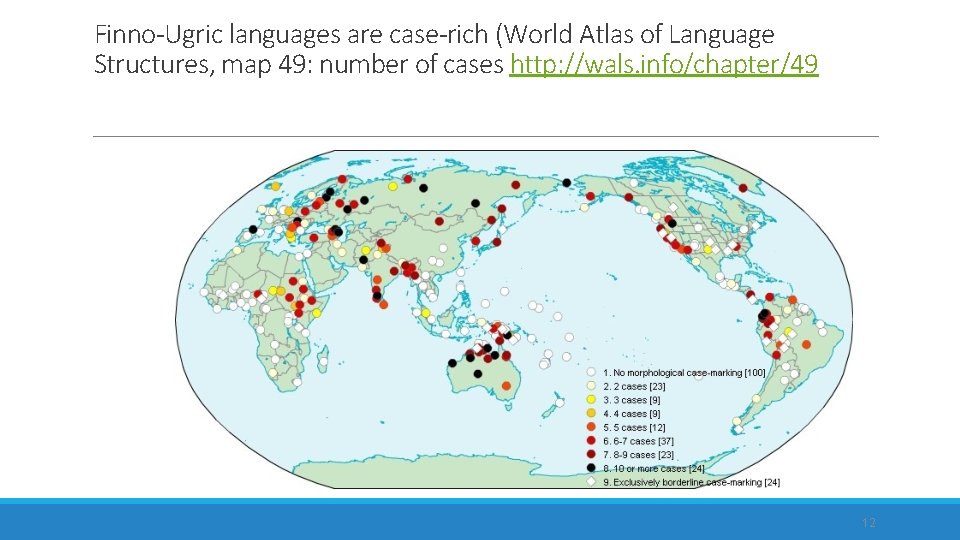

Finno-Ugric languages are case-rich (World Atlas of Language Structures, map 49: number of cases http: //wals. info/chapter/49 12

Estonian and common features of European languages Geographically close languages share similar features (e. g. the perfect and pluperfect with the verb to be in Estonian, Livonian, Latvian and Lithuanian) Regions with common linguistic features are called linguistic areas (German sprachbund), e. g. the Balkan linguistic area Searches for European and Circum Baltic language areas Euroversals, SAE (Standard Average European) etc. 13

Standard Average European (SAE) Benjamin Lee Whorf 1939. The concept arose from comparing the North American indigenous languages with European languages. “Since, with respect to the traits compared, there is little difference between English, French, German, or other European languages with the 'possible' (but doubtful) exception of Balto Slavic and non Indo European, I have lumped these languages into one group called SAE, or "Standard Average European“. “ (Whorf 1956: 138) 14

Standard Average European (SAE): features typical of European languages Martin Haspelmath 1998, 2001: 12 typical structural features (concentrated in Europe, rare outside of Europe) and some other possible common features Common features likely emerged during the great period of migration at the beginning of the formation of the European cultural space. The SAE linguistic area is also called the Charlemagne linguistic area. 15

SAE features (Haspelmath 2001) 12 primarily morphosyntactic features, e. g. ◦ definite and indefinite articles (the book, a book) ◦ Relative clauses with declinable relative pronouns: I woke up a student who had nodded off ◦ HAVE perfect (has done) 16

SAE linguistic area (Haspelmath 2001) Measure of SAE membership: how many of the 9 SAE features are present in a given language. SAE languages with 5 9 SAE features: Romance, Germanic, Baltic, Slavic, Albanian, Greek, Hungarian The remaining languages, with no more than 2 of the common features, fall outside of SAE: Finnish, Estonian, Welsh, Irish Gaelic, Basque, Breton, Maltese, and others. 17

Degrees of SAE membership (map from Heine & Kuteva 2006) 18

SAE features 1 Relative clauses follow the noun; the clause opens with a declinable relative pronoun (e. g. der/die/das/welcher/welches; who, whose, whom) (+) Äratasin tudengi, kes oli tukkuma jäänud ‘I woke up a student who had nodded off’ 19

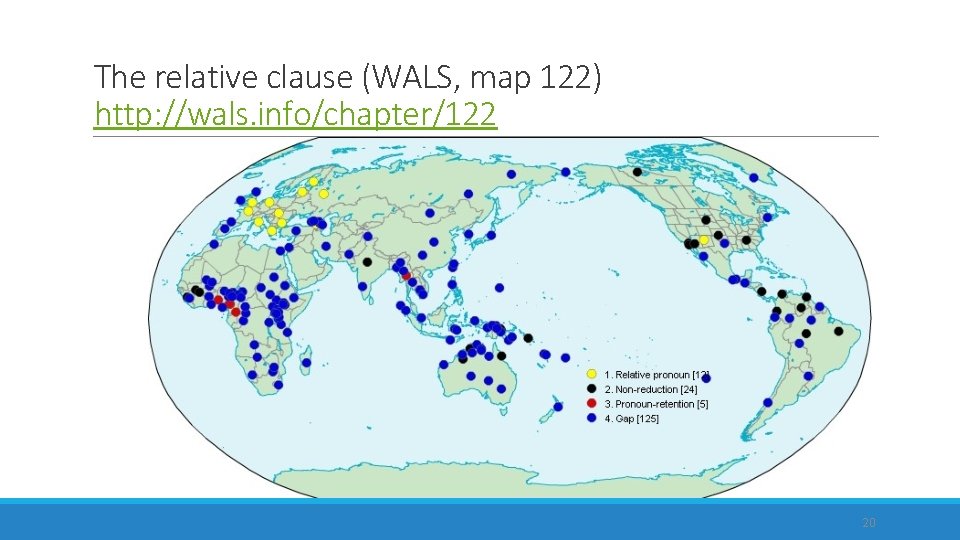

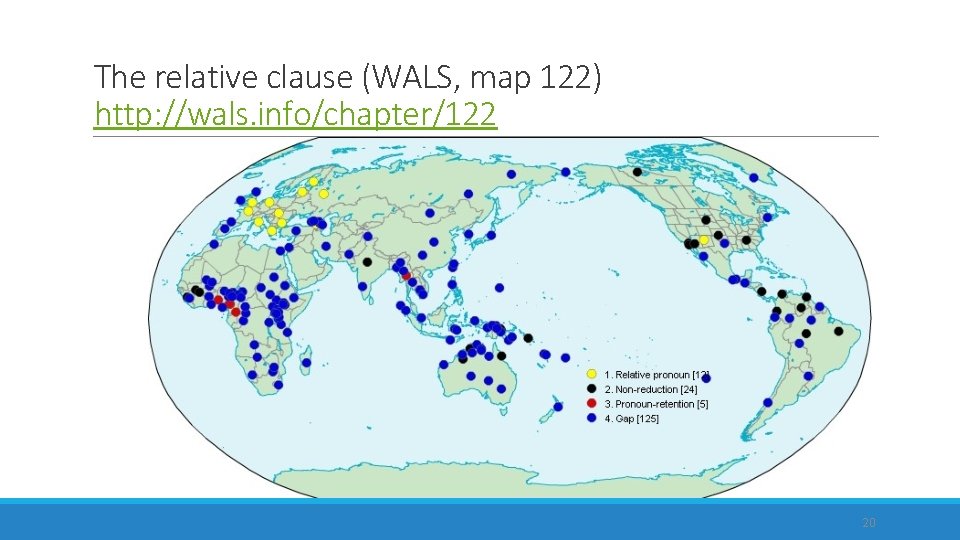

The relative clause (WALS, map 122) http: //wals. info/chapter/122 20

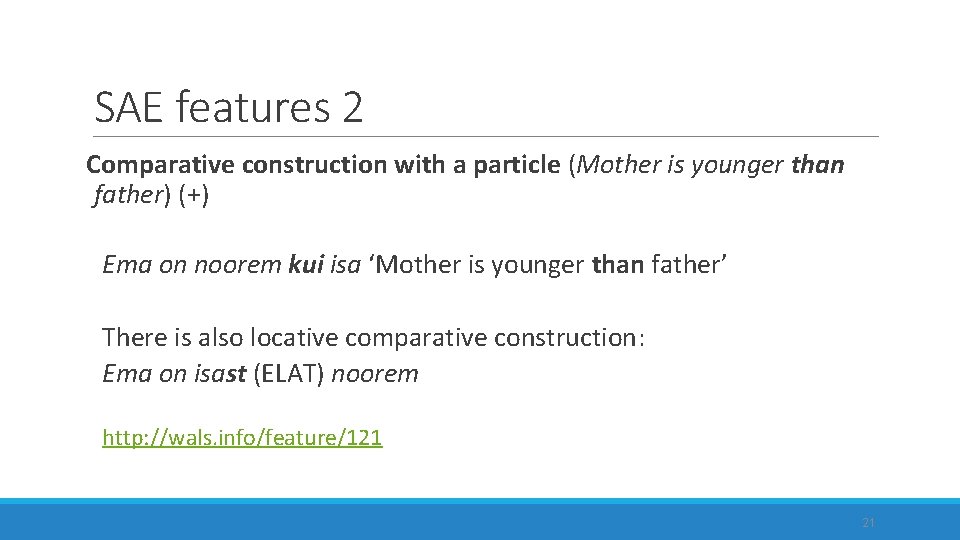

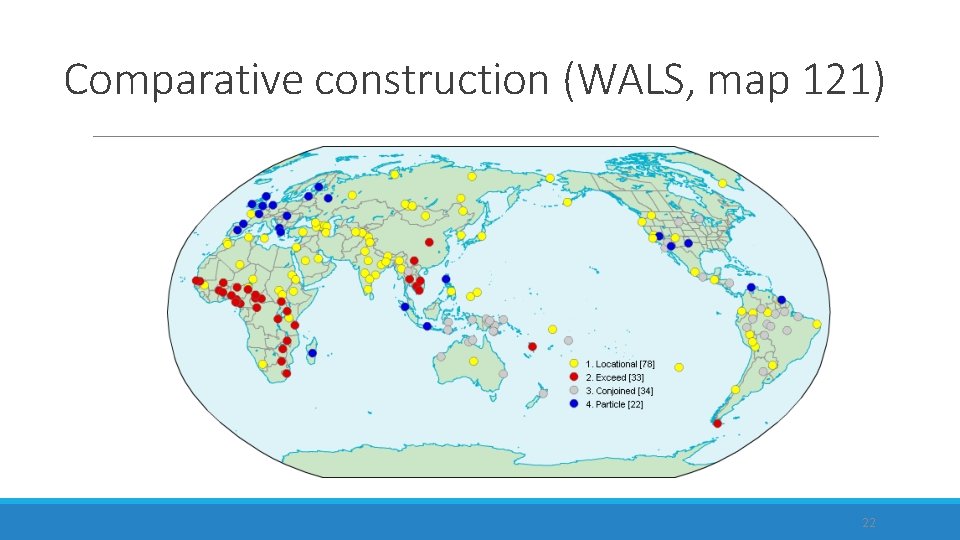

SAE features 2 Comparative construction with a particle (Mother is younger than father) (+) Ema on noorem kui isa ‘Mother is younger than father’ There is also locative comparative construction: Ema on isast (ELAT) noorem http: //wals. info/feature/121 21

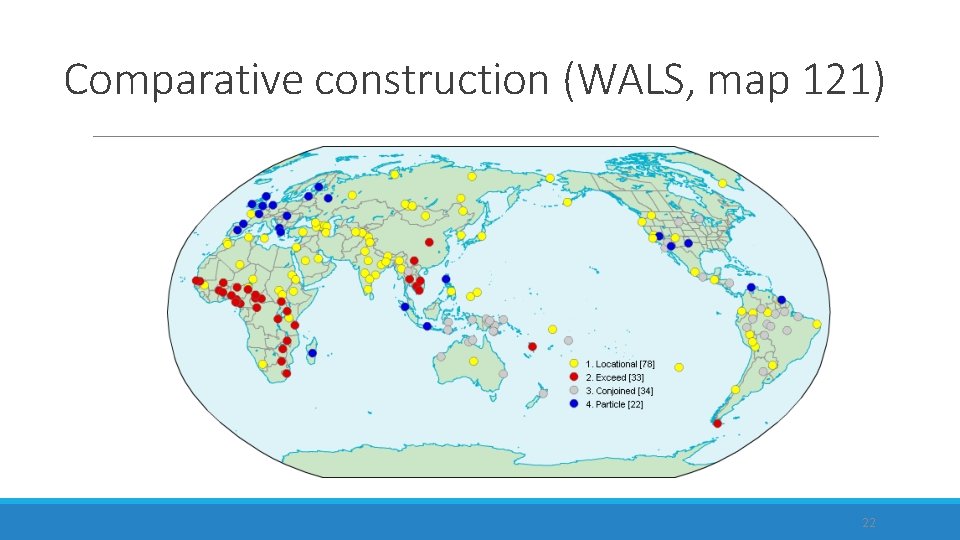

Comparative construction (WALS, map 121) 22

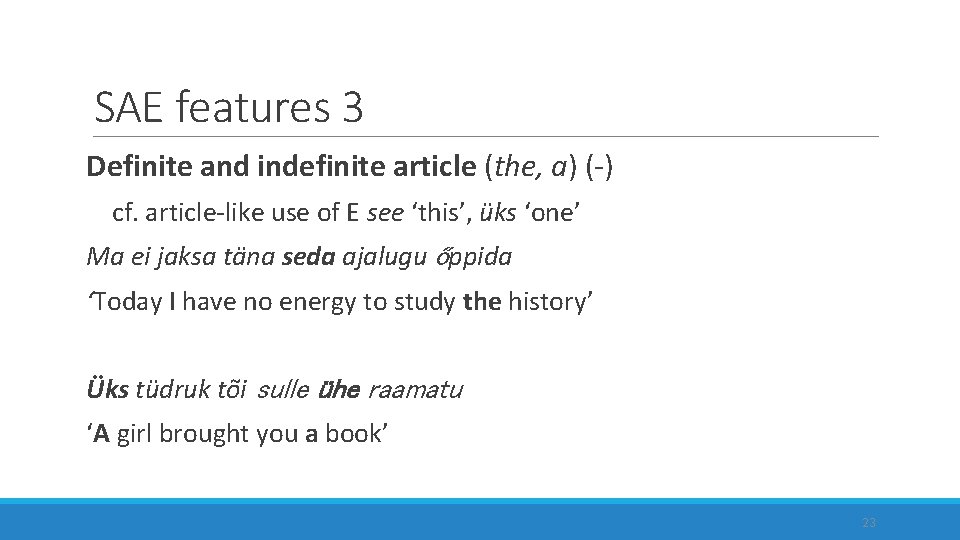

SAE features 3 Definite and indefinite article (the, a) ( ) cf. article like use of E see ‘this’, üks ‘one’ Ma ei jaksa täna seda ajalugu őppida ‘Today I have no energy to study the history’ Üks tüdruk tõi sulle ühe raamatu ‘A girl brought you a book’ 23

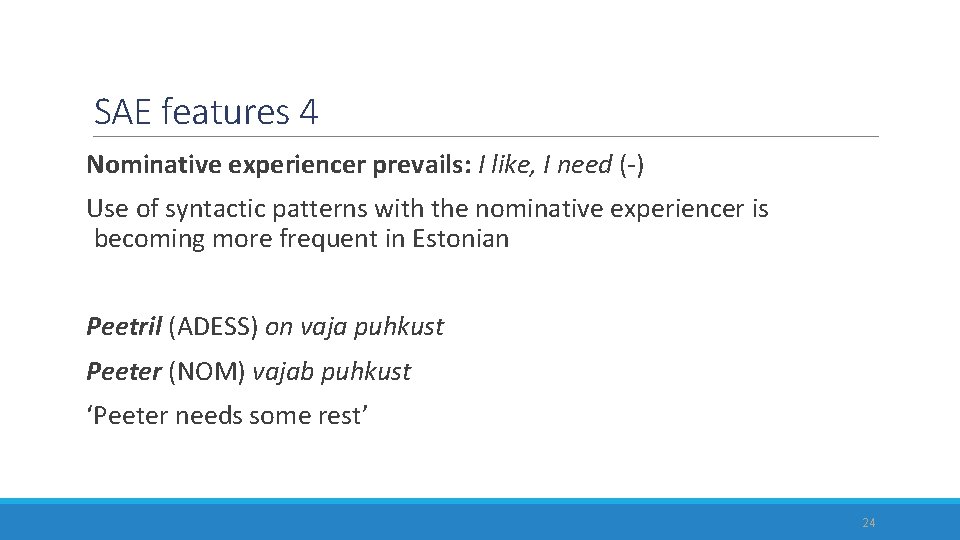

SAE features 4 Nominative experiencer prevails: I like, I need ( ) Use of syntactic patterns with the nominative experiencer is becoming more frequent in Estonian Peetril (ADESS) on vaja puhkust Peeter (NOM) vajab puhkust ‘Peeter needs some rest’ 24

SAE features 5 HAVE-perfect ( ) But possessive syntactic structures with the impersonal / passive perfect are spreading. cf. ownership/possession: Mul on pilet I. ADE is ticket ‘I have a ticket’ possessive perfect: Mul on pilet ostetud ‘I have a ticket bought’; 25

Estonian and the features of SAE 3 features of 12 are present in Estonian, another 5 show developments in Estonian in the direction of SAE. Estonian currently has: • relative clause raamat, mida ma lugesin ‘the book that I read’ • comparative construction suurem kui härg ‘bigger than a bull’ Developing or expanding their usage spheres are the following: ◦ articles: üks mees ‘a man’, see vanaema ‘the grandmother’ ◦ nominative experiencer: ma vajan puhkust ‘I need rest’ ◦ possessive perfect: mul on töö tehtud ‘I have the work done’ ◦ passive: sa oled ülikooli vastu võetud ‘you are accepted into the university’ 26

Language change and variation The concept of SAE: ◦ relies on static descriptions of languages ◦ parallel forms and language variation are not taken into account ◦ categorization is discrete (the feature is either present or absent) It is necessary to consider developments taking place within a language, parallel forms, dialects, sublanguages etc. 27

Some typical developments in European languages (Heine & Kuteva 2006) • Emergence of articles • Emergence of the possessive perfect • Development of modal usages of the verbs ‘threaten’ and ‘promise’ 28

Possessive perfect in the Circum-Baltic area Estonian: Mul on pilet ostetud ‘I have a ticket bought’ Estonian Russian: U tebja bilet kuplen? ‘Have you bought a ticket? ’ North Russian: U menja ruka poraneno ‘My hand is hurt’ (lit. ‘I have my hand hurt’) Votic: Silla on vetettu bābuškalt üvä tširja kāsa ‘You have taken a good letter from grandma’ Latvian: Viņam viss jaubija izteikts ‘He had already said everything’ 29

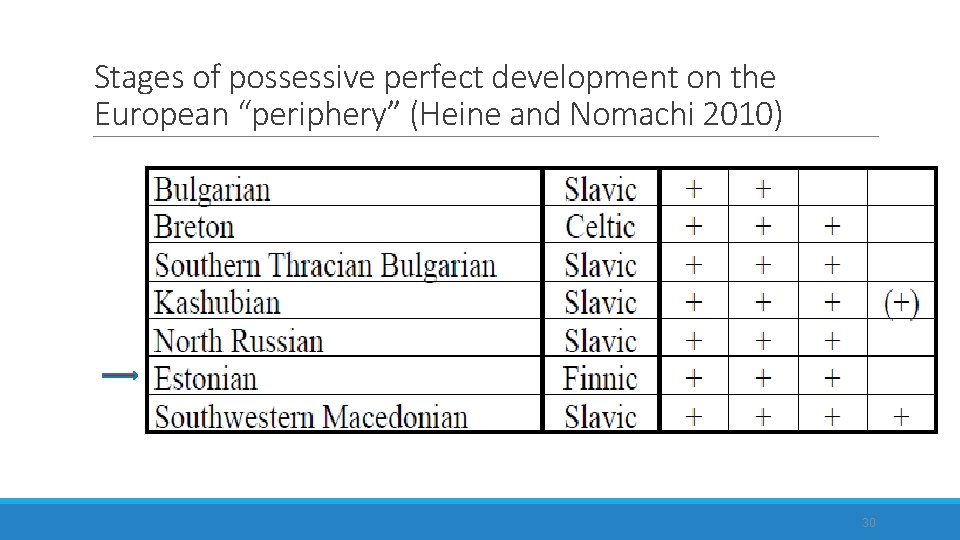

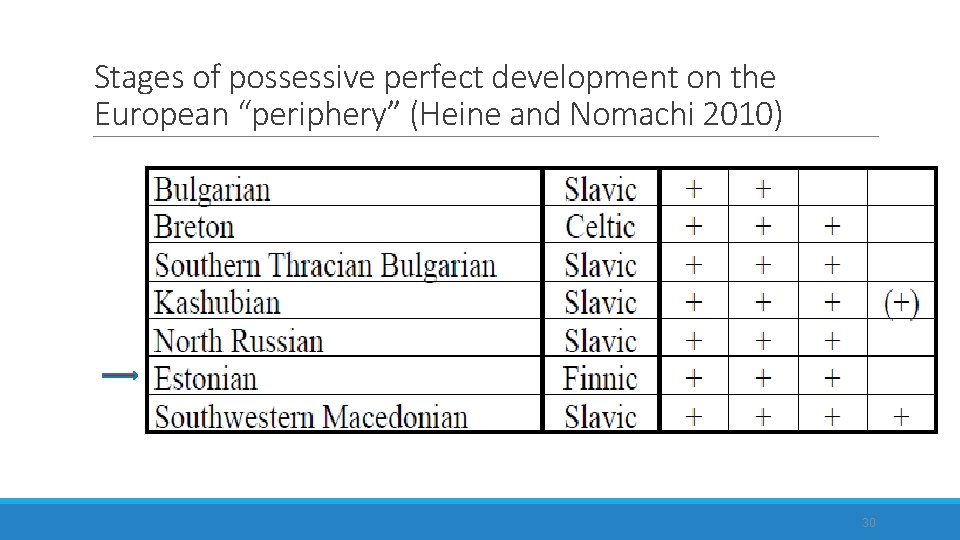

Stages of possessive perfect development on the European “periphery” (Heine and Nomachi 2010) 30

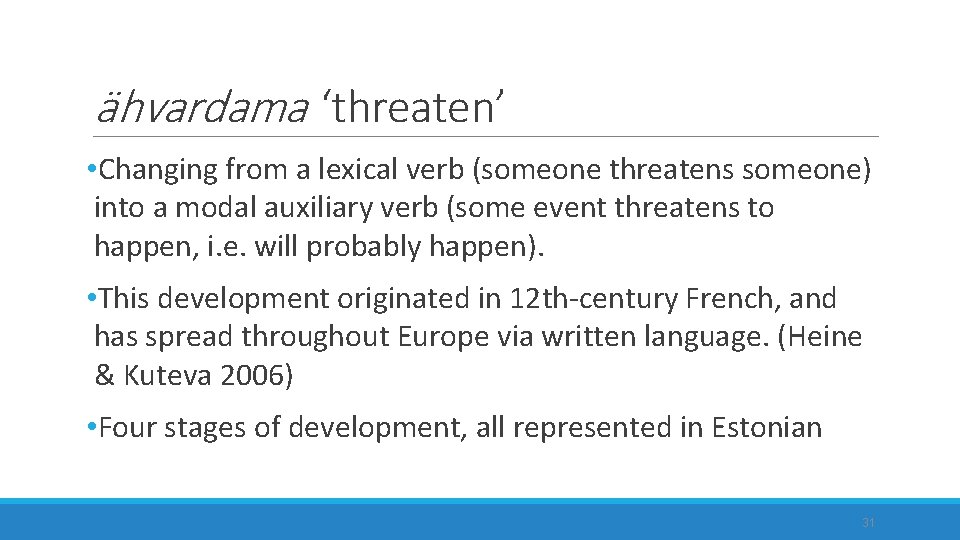

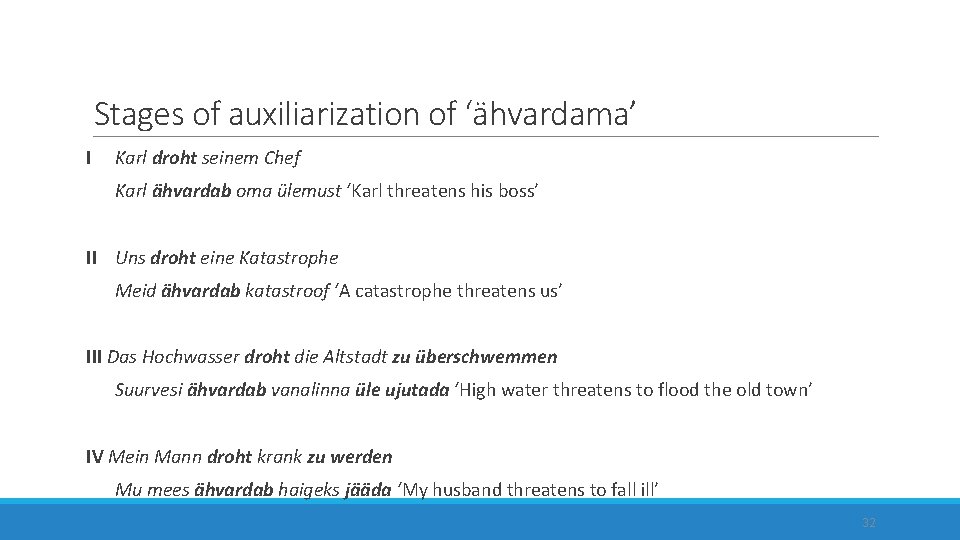

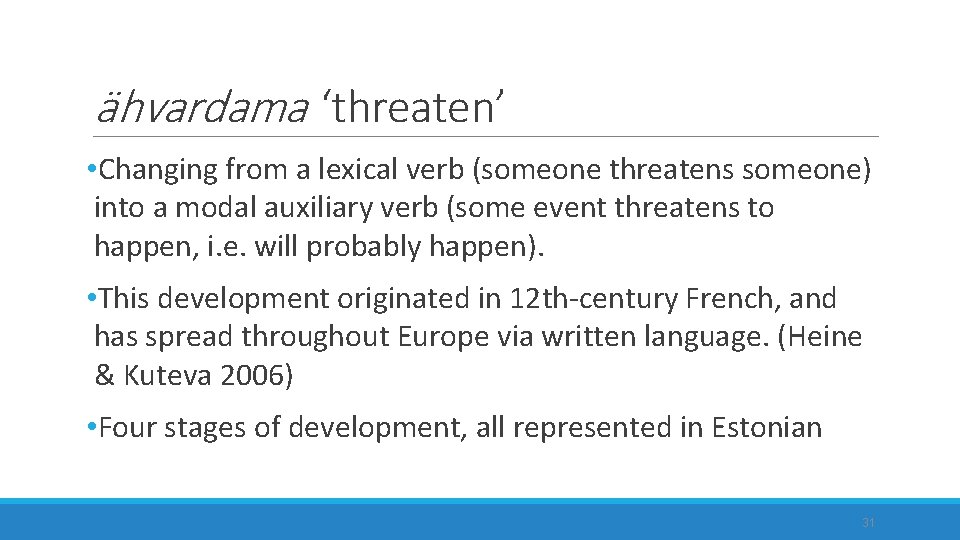

ähvardama ‘threaten’ • Changing from a lexical verb (someone threatens someone) into a modal auxiliary verb (some event threatens to happen, i. e. will probably happen). • This development originated in 12 th century French, and has spread throughout Europe via written language. (Heine & Kuteva 2006) • Four stages of development, all represented in Estonian 31

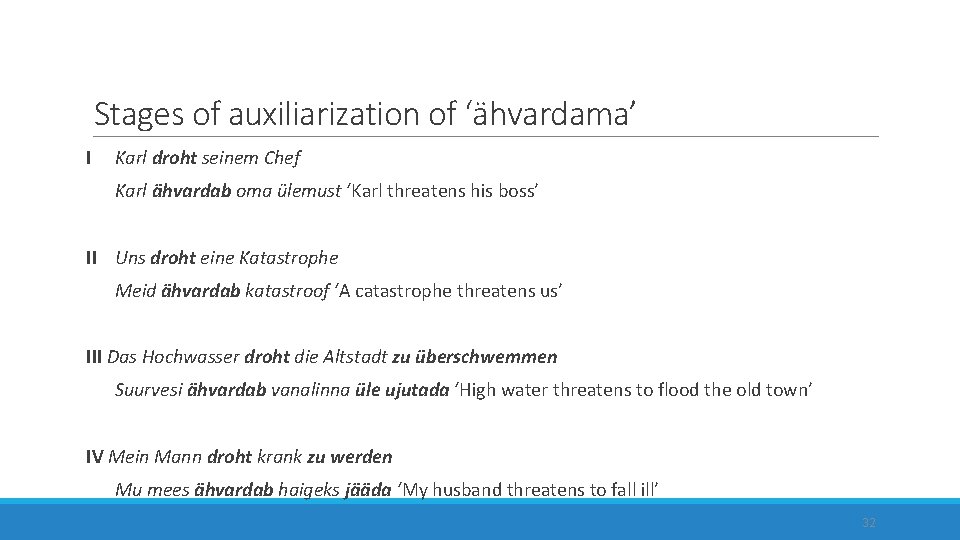

Stages of auxiliarization of ‘ähvardama’ I Karl droht seinem Chef Karl ähvardab oma ülemust ‘Karl threatens his boss’ II Uns droht eine Katastrophe Meid ähvardab katastroof ‘A catastrophe threatens us’ III Das Hochwasser droht die Altstadt zu überschwemmen Suurvesi ähvardab vanalinna üle ujutada ‘High water threatens to flood the old town’ IV Mein Mann droht krank zu werden Mu mees ähvardab haigeks jääda ‘My husband threatens to fall ill’ 32

Stages of development of ‘threaten’ constructions in European languages (Heine ja Nomachi 2010) 33

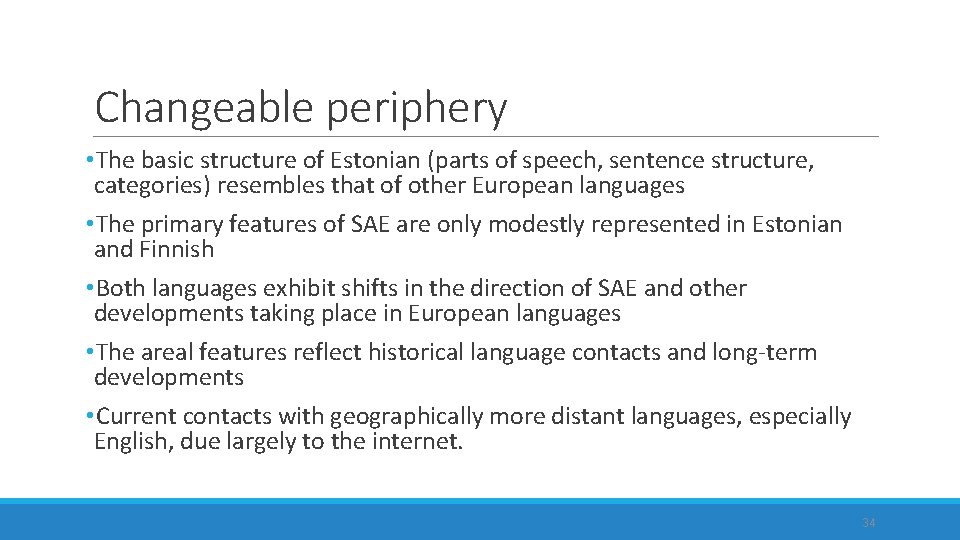

Changeable periphery • The basic structure of Estonian (parts of speech, sentence structure, categories) resembles that of other European languages • The primary features of SAE are only modestly represented in Estonian and Finnish • Both languages exhibit shifts in the direction of SAE and other developments taking place in European languages • The areal features reflect historical language contacts and long term developments • Current contacts with geographically more distant languages, especially English, due largely to the internet. 34

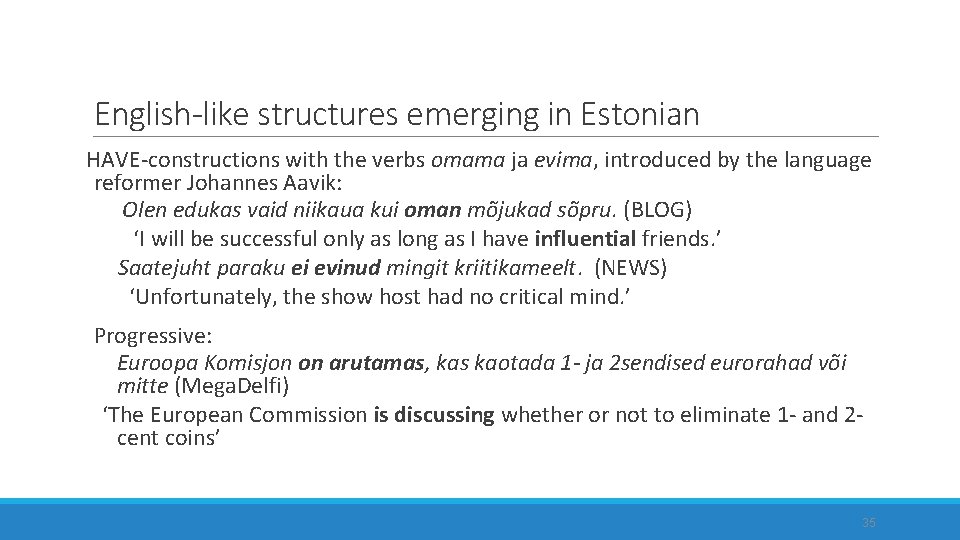

English-like structures emerging in Estonian HAVE constructions with the verbs omama ja evima, introduced by the language reformer Johannes Aavik: Olen edukas vaid niikaua kui oman mõjukad sõpru. (BLOG) ‘I will be successful only as long as I have influential friends. ’ Saatejuht paraku ei evinud mingit kriitikameelt. (NEWS) ‘Unfortunately, the show host had no critical mind. ’ Progressive: Euroopa Komisjon on arutamas, kas kaotada 1 - ja 2 sendised eurorahad või mitte (Mega. Delfi) ‘The European Commission is discussing whether or not to eliminate 1 and 2 cent coins’ 35

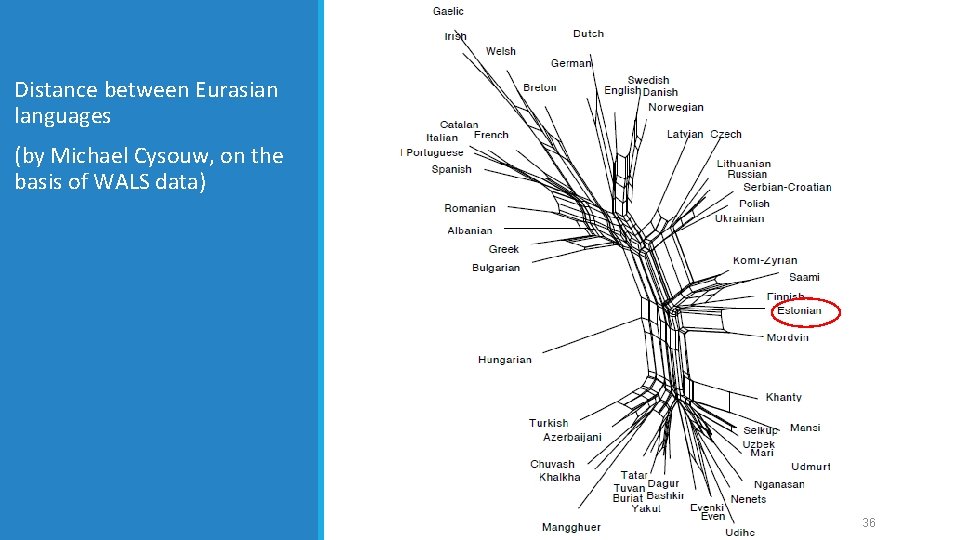

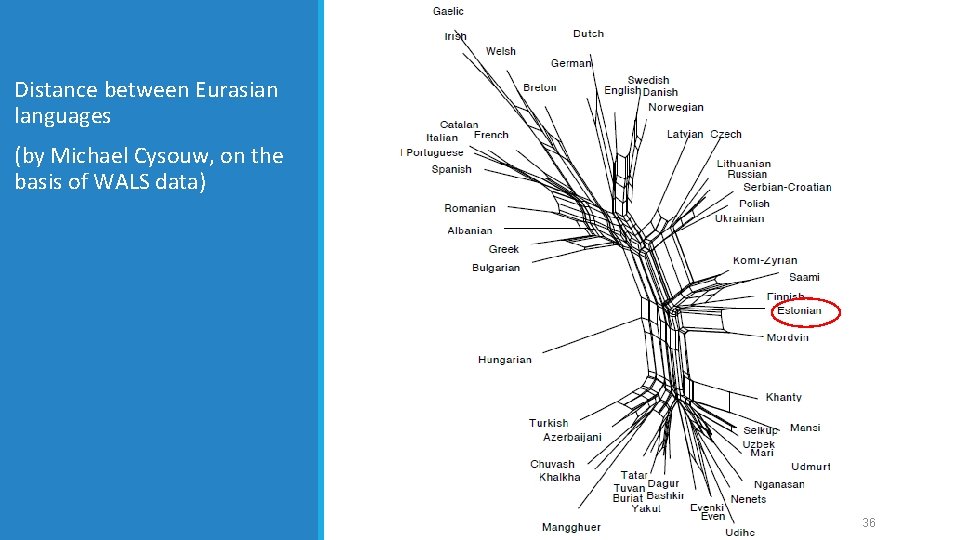

Distance between Eurasian languages (by Michael Cysouw, on the basis of WALS data) 36

Estonian as a Circum-Baltic language The languages spoken near the Baltic Sea share certain similarities, which could be due to: • related languages: Finnic, Baltic (Latvian, Lithuanian), Germanic (Swedish, Danish, German), Slavic (Russian, Polish) • Long term language contacts by both land sea • Similar language internal developments in various languages 37

The Circum-Baltic language area 1 • Linguistic area? Rather a contact superposition zone (Koptjevskaja Tamm & Wälchli 2001) • Power and borders in the region have shifted throughout history and there has not been one single center of political control • Nor have the shared linguistic features converged in any one central area 38

Object and subject case alternation Found in Finnic, Baltic, and Eastern Slavic languages. Mutual influence. Est laual on raamat (NOM) / laual ei ole raamatut (PART) Fin pöydällä on kirja (NOM) / pöydällä ei ole kirjaa (PART) Rus na stole kniga (NOM) / na stole net knigi (GEN) ‘There is a book / no book on the table’ Lit Jis davė man knygą (ACC) / Jis nedavė man knygos (GEN) Est Ta andis mulle raamatu (GEN) / ei andnud mulle raamatut (PART) ‘He gave me a book/did not give me a book’ 39

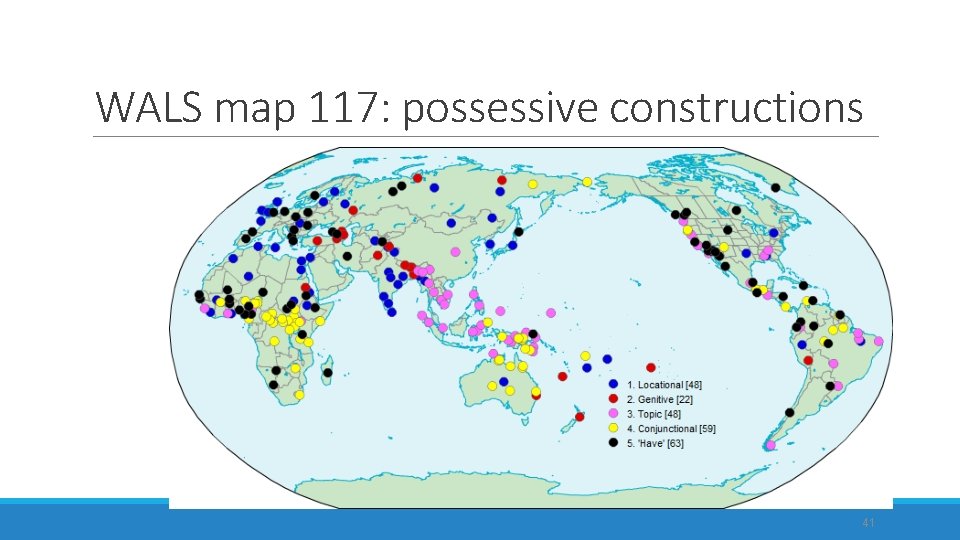

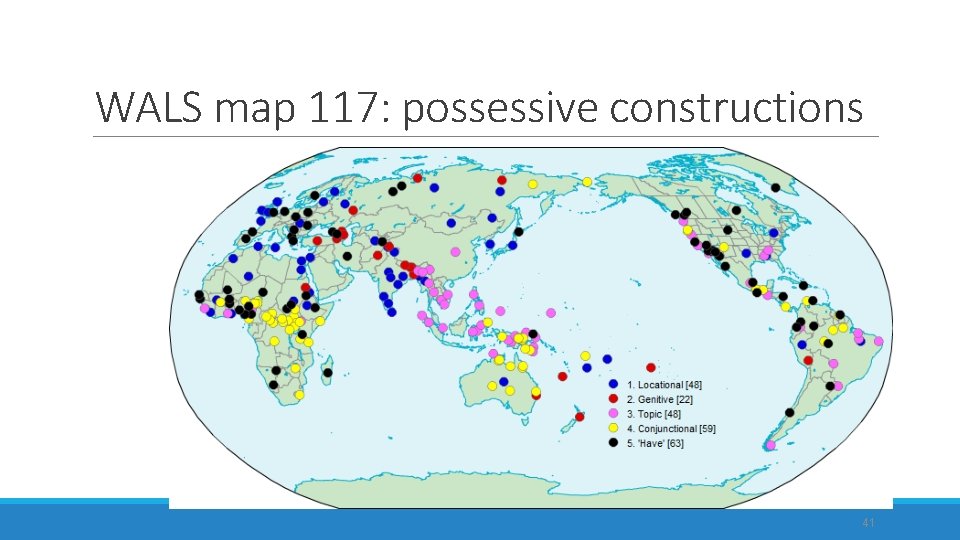

Possessive construction Locative construction with the verb ‘be’ in Finnic, Latvian, Russian, unlike the ‘have’ construction which is widespread in Europe. http: //wals. info/feature/117 A Est Mul on uus auto Fin Minulla on uusi auto Rus U menja novaja mašina ‘I have a new car’ 40

WALS map 117: possessive constructions 41

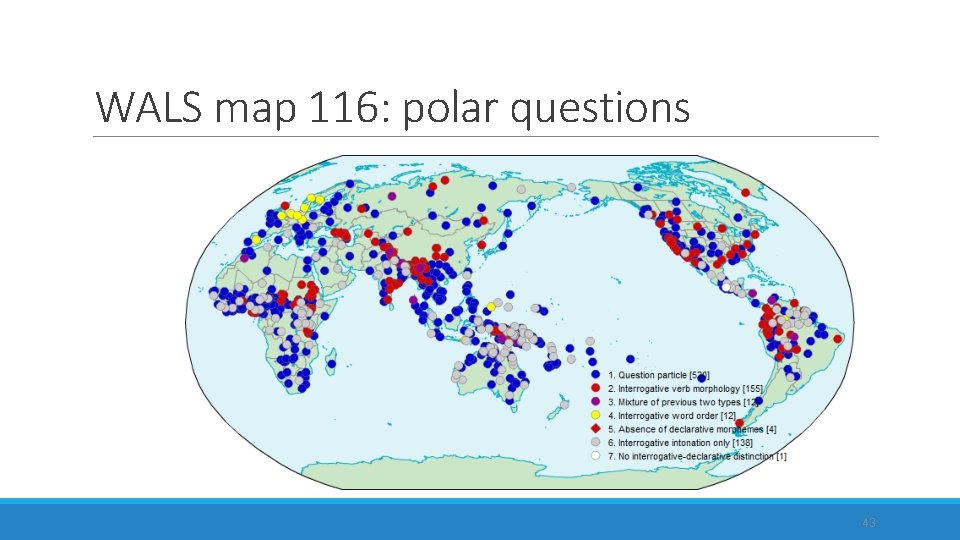

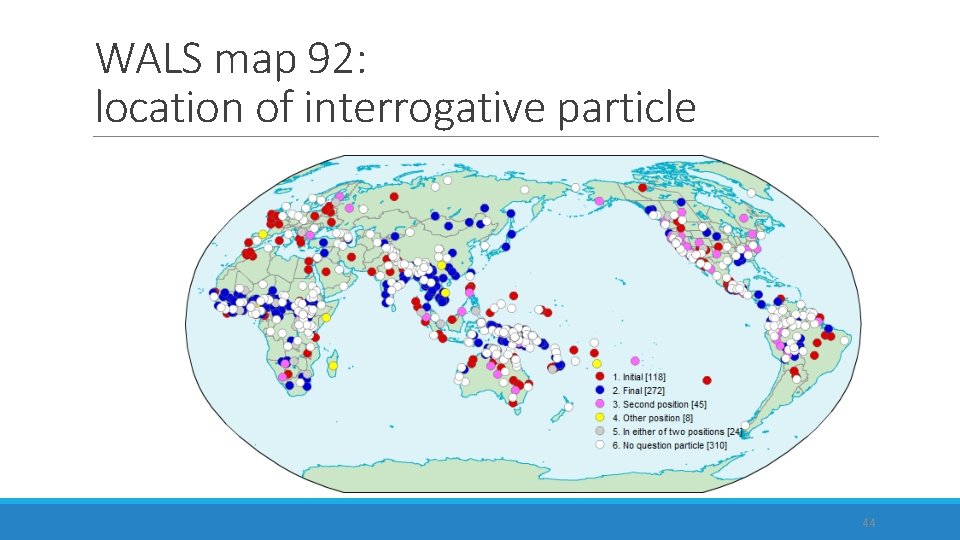

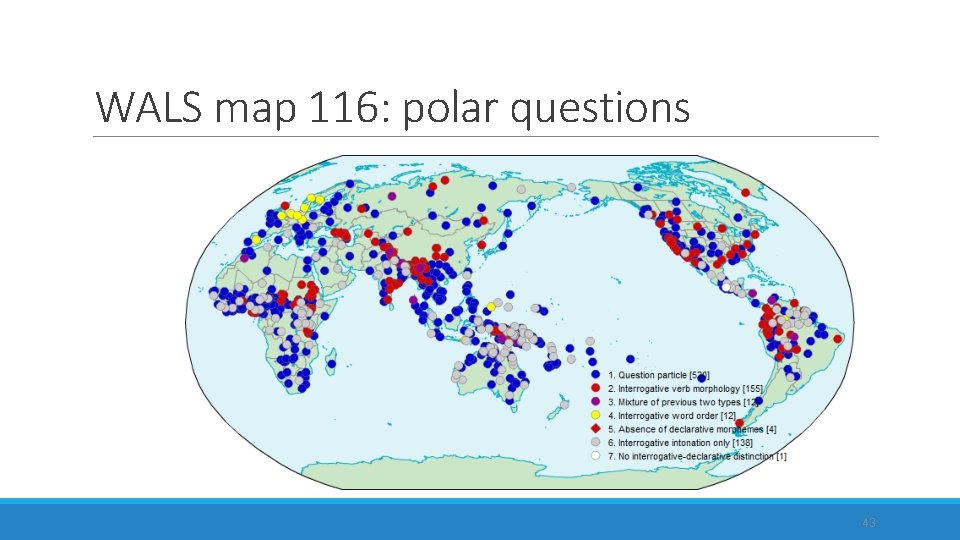

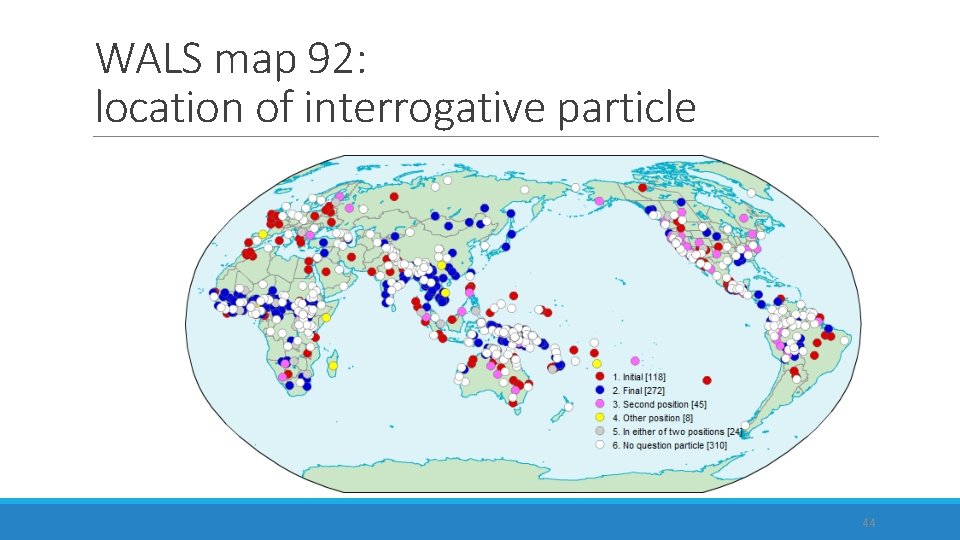

Polar questions Sentence initial interrogative particle – some languages, e. g. Estonian, Livonian, Baltic languages. http: //wals. info/feature/92 A Est. Kas ta tuleb? Liv. Voi ta tulāb? Lith. Ar jis ateis? ‘Is he coming? ’ Verb initial question – Estonian, Finnish, Germanic, Slavic languages. Probably of SAE origin. Oled sa täna kodus? ‘Are you at home today? ’ http: //wals. info/feature/116 A 42

WALS map 116: polar questions 43

WALS map 92: location of interrogative particle 44

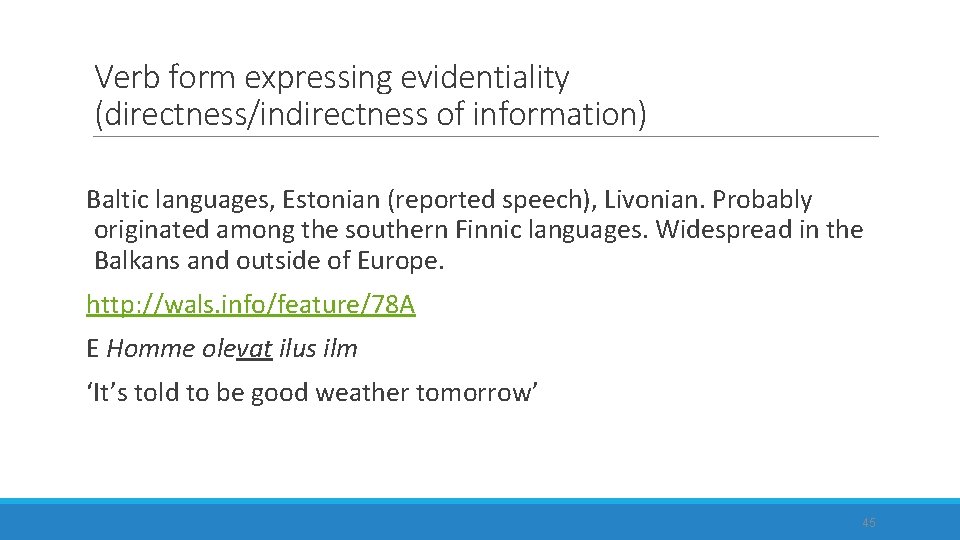

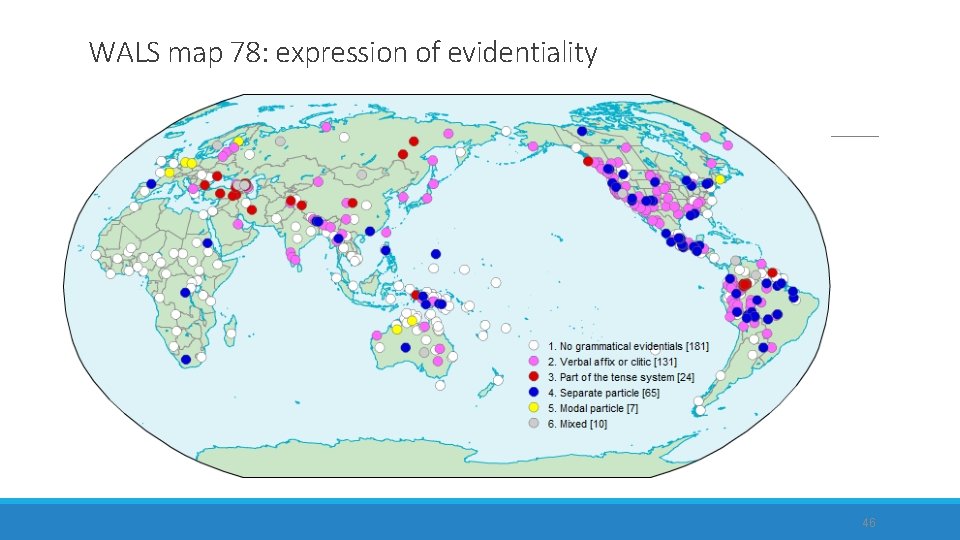

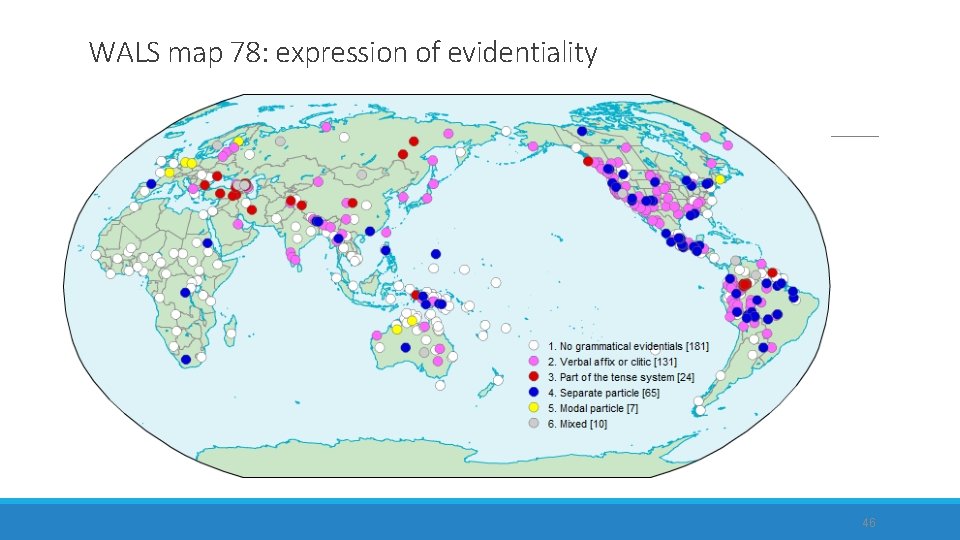

Verb form expressing evidentiality (directness/indirectness of information) Baltic languages, Estonian (reported speech), Livonian. Probably originated among the southern Finnic languages. Widespread in the Balkans and outside of Europe. http: //wals. info/feature/78 A E Homme olevat ilus ilm ‘It’s told to be good weather tomorrow’ 45

WALS map 78: expression of evidentiality 46

Estonian in the Circum-Baltic area Estonian exhibits most of the structural features widespread in the Circum Baltic language area Therefore, Estonian can be considered one of the central Circum Baltic languages 47

Where does Estonian belong: the static perspective • among Finnic languages – the same basic structure • among the central Circum Baltic languages • on the periphery of SAE 48

Where does Estonian belong: the dynamic perspective o. Common developments with other European languages convergence o. Slightly closer to SAE than Finnish is o. Globalization, the information age, and free movement of people serve to bring languages and linguistic changes together – linguistic areas can be reshaped 49

Changeable periphery During the co existence that spans over several millennia the Uralic and Indo European languages around the Baltic Sea have converged while there has been divergence from their genetically related eastern languages. (Dahl 2008) 50

Tuulemaa language (Henn Saari) 51

References 1 Cysouw, Michael 2010, An MDS map based on World Atlas of Language Structures. Dahl, Östen 2008, Kuinka eksoottinen suomen kieli on? Virittäjä 4: 545– 559. Haspelmath, Martin 1998, How young is standard average European? in: Linguistic Sciences, 20. 3: 272 287. Haspelmath, Martin 2001, The European linguistic area: Standard Average European, in: Haspelmath, Martin; König, Ekkehard; Oesterreicher, König & Raible, Wolfgang (eds. ), Language typology and language universals: An international handbook. Vol. 2. (Handbücher zur Sprach und Kommunikations wissenschaft, 20. 2. ) New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1492– 1510 Hasselblatt, Cornelius 1993, Estnisch, Finnisch und Ungarisch: zur Bewertung der Schwierigkeiten für deutsche Muttersprachler. – Linguistica Uralica XXIX, 3: 176 – 181. Heine, Bernd & Kuteva, Tania 2006, The changing languages of Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Heine, Bernd & Motoki Nomachi 2010, Is Europe a Linguistic Area? M. Nomachi (ed. ), Grammaticalization in Slavic Languages: From Areal and Typological Perspectives. (Slavic Eurasian Studies 23. ) Hokkaido University. Klaas, Birute 1997, The quotative mood in the Baltic Sea areal. – Estonian: Typological Studies II. Ed. M. Erelt. (= Publications of the Department of Estonian of the University of Tartu 8. ) Tartu, 73– 97. Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Maria & Wälchli, Bernhard 2001, The Circum Baltic languages: An areal typological approach. − Dahl, Östen & Maria Koptjevskaja Tamm, The Circum Baltic Languages, vol. 2. Grammar and Typology. Benjamins, Amsterdam/Philadelphia; 615− 629; 724− 733.

References 2 Lindström, Liina & Ilona Tragel 2010, The possessive perfect construction in Estonian. – Folia Linguistica 44: 371 399. Lindström, Liina 2013, Between Finnic and Indo European: Variation and change in the Estonian experiencer object construction. Seržant, Ilja A. & Leonid Kulikov, The Diachronic Typology of Non Canonical Subjects. Benjamins, Amsterdam/Philadelphia: 141 164. Metslang, Helle 2009, Estonian grammar between Finnic and SAE: some comparisons. – Linguistic Typology and Universals (STUF) 1/2, 2009: 49− 71. Saari, Henn 2004, Keelehääling. Eesti Raadio „Keeleminutid” 1975– 1999. Tallinn: Eesti Keele Sihtasutus. Seržant, Ilja A. 2012, The so called possessive perfect in North Russian and the Circum Baltic area. A diachronic and areal account. Lingua, Volume 122, issue 4 (March, 2012), p. 356 385. Skalička, Vladimir 1975, Über die Typologie des Estnischen. − Congressus tertius internationalis fenno ugristarum Tal linnae habitus 17. − 23. VIII 1970. Acta redigenda curavit Paul Ariste. Pars I. Acta Linguistica. "Valgus", Tallinn: 369− 373. van der Auwera, Johan 2011, Standard Average European. The Languages and Linguistics of Europe: A Comprehensive Guide. ed. by B. Kortmann & J. van der Auwera. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton, 291 306. WALS = Haspelmath, Martin; Dryer, Matthew, Gil, David; Comrie, Bernhard (eds. ) 2005, The World atlas of language structures. Oxford: Oxford University press. [http//www. wals. info] Whorf, Benjamin Lee 1956. Language, Thought and Reality: Selected Writings of Benjamins Lee Whorf. Edited by John B. Carroll. Cambridge, Mass. : Tha M. I. T. Press. Ziegelmann, Katja & Winkler, Eberhard 2006, Zum Einfluβ des Deutschen auf das Estnische. Arold, Anne; Cherubim, Dieter; Neuendorff, Dagmar & Nikula, Henrik (Hrsg. ), Deutsch am Rande Europas. (Humaniora: Germanistica 1. ) Tartu: Tartu University Press, 43– 70.