ESL 8150 Lesson 4 ffe Syntactic relations explored

![Summary (cont’d) 3. Smokey [left [the room]]. In the VP left the room, the Summary (cont’d) 3. Smokey [left [the room]]. In the VP left the room, the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/0672841783f0987f130b9027017af6af/image-3.jpg)

- Slides: 15

ESL 8150 Lesson 4, ffe • Syntactic relations explored further and more on syntactic universals • Data/material collection methods 1

Summary of Lesson #3 covered head-complement dependency relationships & and universals/typology based upon head-complement ordering and marking across languages. The term head refers to the essential piece in any given phrase (be that an NP, VP, Adv. P, or PP) and the term complement refers to all and any elements that are part of the same phrase as the head. These complements (or dependents) can be optional or obligatory. Examples: 1. Smokey is a cat. (cat #1 cohabiting with F. Erku) Smokey=NP, consists of a head only; is a cat=VP, where the copula be is the head and the NP a cat is the complement. At the sentence level, NP-VP, the subject is the head (main argument) in the sentence and being a cat is the complement of this NP. Phrases are nested within phrases; thus, more than one level of head-complement relationship 2. Smokey is a very demanding cat. Within the VP, is a very demanding cat, we have the head verb (is, a copula be form), followed by an NP=a very demanding cat. This NP consists of an adjectival phrase plus the head noun cat. Within the adjectival phrase a very demanding, demanding is the head of the phrase and the words a and very function as the complement of the head 2

![Summary contd 3 Smokey left the room In the VP left the room the Summary (cont’d) 3. Smokey [left [the room]]. In the VP left the room, the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/0672841783f0987f130b9027017af6af/image-3.jpg)

Summary (cont’d) 3. Smokey [left [the room]]. In the VP left the room, the room is an optional complement as we could simply say, “Smokey left. ” 4. Smokey [hates Mitzie] (cat #2). In the VP hates Mitzie, Mitzie is an obligatory dependent/complement given the transitive status of the verb. Additionally, it was noted that languages can be classified as head-initial (especially with regard to the position of the object with respect to the verb) and some as head final. The terms VO languages and OV languages refer to the same categorization. This is an important distinction for applied linguistics in that it helps us anticipate potential errors—doesn’t entail they’ll happen Proceeding to new material 3

The notions of unmarked & marked The term unmarked: technical term in linguistics, describing items found more commonly, and are, in some sense, simpler and more basic. For example, the sound [t], a voiceless dental stop, as in tin and take is unmarked in contrast to the voiceless dental fricative [θ] sound as in thin and thorough—a sound considered more marked Markedness: applicable in all areas of language study. See preceding paragraph for an ex from phonetics/phonology • Morphologically/semantically speaking, a term to mean ‘mom’ would occur more commonly than one meaning ‘earth sciences’ across languages • Markedness applies not only cross-linguistically but also intralinguistically—to the study of a single language. For example, in English the word simultaneously would be considered more marked than nicely. 4

Marked/unmarked word orders Now applying the notions of marked/unmarked to the study of word order, most languages have a preferred, neutral word order that is used more commonly and is considered the basic word order by the speakers of that language. In English, the order of SVO is the basic word order and variations to this order usually serve an additional grammatical and/or pragmatic function. Examples: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Jerry lives in Bloomington Jerry is the one living in Bloomington It is Jerry who lives in Bloomington It is in Bloomington that Jerry lives Bloomington is where Jerry lives 1 -5 have the same propositional, basic meaning but clearly not the same constituent ordering. #1 would be picked out as the unmarked one. 5

Word orders—cont’d As noted in your textbook, some languages, especially those with sophisticated case marking of nominals, have more flexible word orders. In languages with rich morphology, you don’t have to rely on the word order as much to determine the subjects and objects in the language. For example, in Turkish and Malayalam (a Dravidian language spoken in India), direct objects are marked with an accusative ending. In Turkish, ordinarily the primary object could be in its unmarked position— preceding the verb. It could also be placed in sentence-initial position and continue to be interpreted as the object—given the accusative suffix. Case marking can be linked to subject deletion in some languages. For ex, in Spanish b/c verb endings indicate who the subject is, subject pronoun deletion is allowed. Called pro-drop language 6

Core arguments: subjects, agents & objects Earlier, we talked about grammatical relations (subject & object roles primarily) being distinct from semantic roles (being an agent, patient, etc. ) While some subjects are agents (i. e. , they are involved in a conscious act and are perceived as instigators of such acts), others are not. Let us look over some examples: 1. Bob greeted Felicity (Bob=subject and agent; Felicity=object) 2. Bob was tired (Bob=subject) 3. Bob married Felicity twice (Bob=subject and agent; Felicity=object) twice=is not a core argument; it is an adverb with an adjunct function) 4. Bob is upstairs (Bob=subject). This is a single-argument sentence. 5. Bob kissed Felicity in the back yard (multi-argument sentence; Bob=subject and agent; Felicity=Object and in the back yard=PP used as an adverbial. This PP is not a core argument) Now consider the following data 7

Core arguments (cont’d) 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. He kissed her She was gone They helped us We rested We helped her The additional data suggest that personal pronouns in English are marked distinctly to express core grammatical roles—well, it is not a perfect paradigm but for the most part we have subjective (nominal) and objective (accusative) forms of personal pronouns: I/me, you/you, he/him, she/her, it/it, we/us, you/you and finally they/them. . Sentences 1 -10 indicate that regardless of transitivity of the verb (i. e. , in both singleargument and multi-argument sentences), subjects and agents behave the same (they precede the verbs) and have distinct forms if personal pronouns. These sentences also show that objects are distinguished from subjects by constituent ordering (they follow the verbs) and by morphological marking in the case of personal pronouns 8

Processing time: mini exercise (identifying roles) Identify the core arguments (subjects/agents and direct objects) in the following sentences. What do you rely on in determining these roles? 1. My sister is a teacher 2. She prepares her lectures every weekend 3. Jim broke the window 4. The window was broken by Jim 5. 5. I slept 1. My sister=subject; no object in the sentence. Being a teacher=complement 2. She=subject and agent; her lectures=direct object; every weekend=is not a core argument—it is an adverbial adjunct 3. Jim=subject and agent and the window=object 4. Jim’s agency is maintained in #4 and the window is still the object. (Promotion of object NP and demotion of subject NP via passivization) 5. And finally #5: I is the subject; no object We rely on: word order, subject-verb agreement, and morphological shape of the pronoun along with passive morphology in determining what is subject/agent & object and what is not. Let’s proceed to next slide 9

Universals based on grammatical relations Having read some of the chapters in Tallerman (and recalling what was covered in other classes), you won’t be surprised to hear for almost all linguistic phenomena studied, linguists have attempted to come up with generalizations/universals. In regard to how grammatical relations are expressed across languages, scholars have noted the following systematization. (Note: detailed subcategories are not given below; what I provide here should suffice for the purposes of this class). 1. Nominative/accusative systems 2. Ergative/absolutive systems 3. Split systems In nominative/accusative systems (accusative for short), nominals are marked for subjecthood/agenthood and for objecthood—although they may not be necessarily differentiated to the full extent. Remember in English, which is considered an accusative language, there is case marking in pronouns and where the pronoun occurs in the sentence is significant as well, along with agreement. 10

Universals (cont’d) Let’s look at 1 -4: 1. 2. 3. 4. I dance He dances I like him He likes me Subject pronouns (nominative) are I and he and object pronouns (accusative case) are him and me, as you are already aware. French is another example of an accusative language: 1. 2. 3. 4. Je mange ‘I eat’ Il mange ‘he eats’ Je le vois ‘I see him’ Il me voit ‘he sees me’ Important note: Remember, in linguistics zero marking (lack of an affix/particle) is considered marking, i. e. , it is a way to single something out. ) 11

Universals (cont’d) In accusative systems, subjects of transitive and intransitive clauses behave similarly. That is, regardless of whether a verb takes an object or not, we have the same marking on the nominal. For instance, in 1 -4 above, dance is an intransitive verb and like is transitive. And despite this difference the same subject pronoun is used. Let me underscore this once more, before moving on to ergative languages: In accusative languages, subjects of transitive and intransitive clauses (subjects & agents) are marked in the same way (behave similarly), while objects of transitive clauses are marked differently (behave differently). Thus subjects and agents constitute one group and objects another group. In absolutive/ergative systems (ergative for short), objects of transitive clauses are marked the same way as subjects of intransitive clauses, while transitive subjects (agents) are marked differently. This may sound like a tongue twister; it is actually easier than it sounds: agents constitute one group and non-agent arguments constitute another group. Just be aware that some languages spoken in Australia, Central Asia and South America may show this pattern. Let me give an example from Walmatjari (spoken in Australia). See next slide. 12

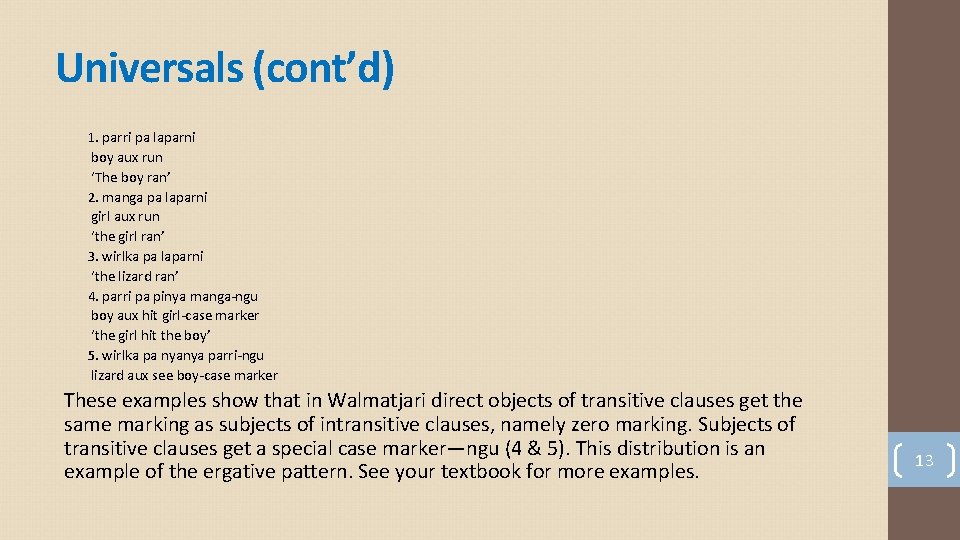

Universals (cont’d) 1. parri pa laparni boy aux run ‘The boy ran’ 2. manga pa laparni girl aux run ‘the girl ran’ 3. wirlka pa laparni ‘the lizard ran’ 4. parri pa pinya manga-ngu boy aux hit girl-case marker ‘the girl hit the boy’ 5. wirlka pa nyanya parri-ngu lizard aux see boy-case marker These examples show that in Walmatjari direct objects of transitive clauses get the same marking as subjects of intransitive clauses, namely zero marking. Subjects of transitive clauses get a special case marker—ngu (4 & 5). This distribution is an example of the ergative pattern. See your textbook for more examples. 13

Universals—one final point & moving on Now in split systems both ergative and accusative case marking patterns are found. For example, pronouns may take accusative marking while common nouns take ergative marking. Dyirbal (spoken in Australia) exhibits split ergativity. Additional language samples are provided in MT, ch 6. ESL IMPLICATIONS Reflecting upon what’s covered in this lesson (and its associated exercises, etc. ), the following are worthy of note: • There is a lot more to subjects and objects than we may have assumed before. When we talk about subjects and objects in our ESL classrooms, usually there’s the assumption that we can clearly identify them and describe what they are. In this lesson, we’ve underscored the fact that a core grammatical relation, e. g. , that of subjecthood, may have a different semantic role associated with it depending on the sentence. I am not suggesting you categorize the subjects as agents, patients, experiencer, etc, and have your students do the same! However, defining subjects as “nominals describing an action” may not be sufficient and might be confusing to the student. As we said earlier, be sure to include examples illustrating all roles. 14

ESL Implications (cont’d) • Languages may employ different structural features (what we called morphosyntactic marking) to express grammatical relations—from word order to case marking. Again it is interesting to note that the notion of grammatical relation seems to be a universal, while how it is marked is not. Knowing how a home language differs from English in regard to these structural features might help you with error analysis and correction. • Just because English and other Indo-European languages are accusative (with subjects/agents in transitive and intransitive clauses behaving the same way) does not mean that other languages are also accusative. Be grateful if you have no students whose home languages are ergative! If you happen to have some, keep in mind that acquiring different patterns of marking may take longer and may require further focussed practice. This concludes my “instructor’s notes, set #1” for Lesson #4. 15