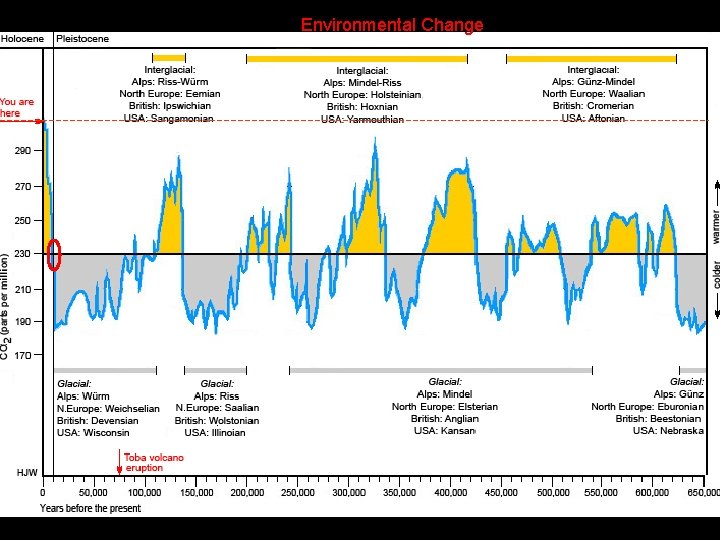

Environmental Change Domestication Domestication production of new species

- Slides: 54

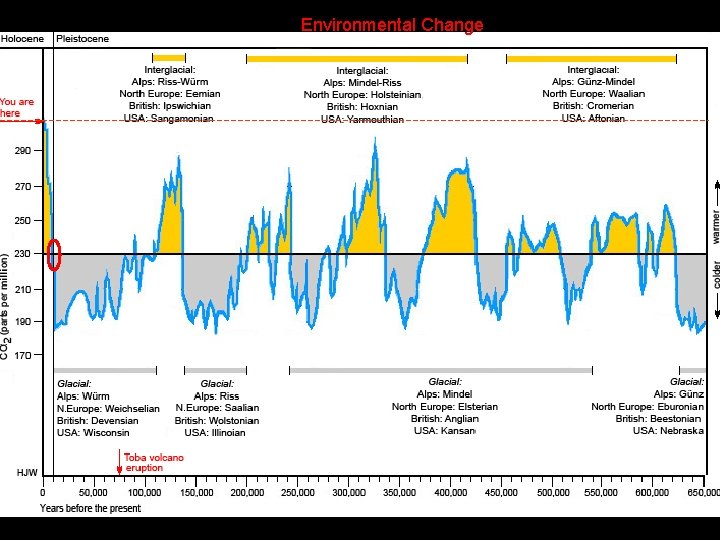

Environmental Change

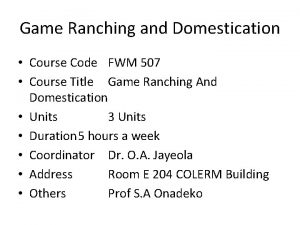

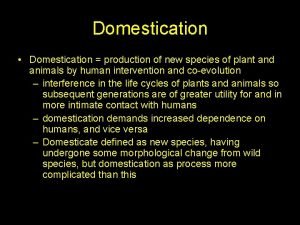

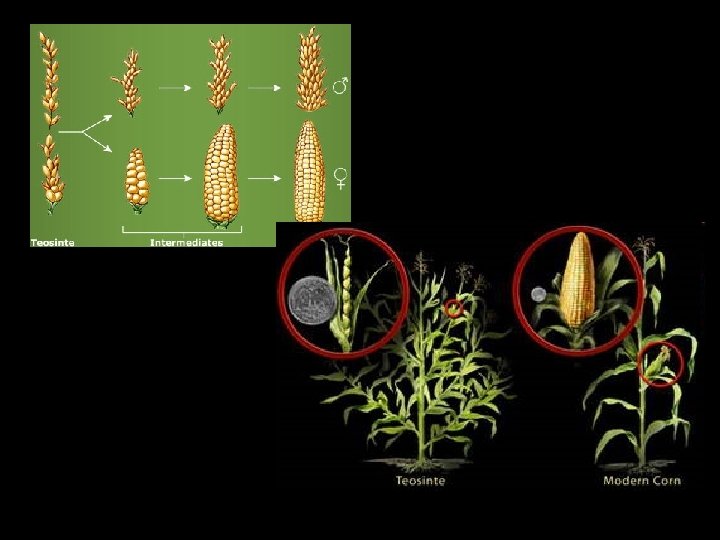

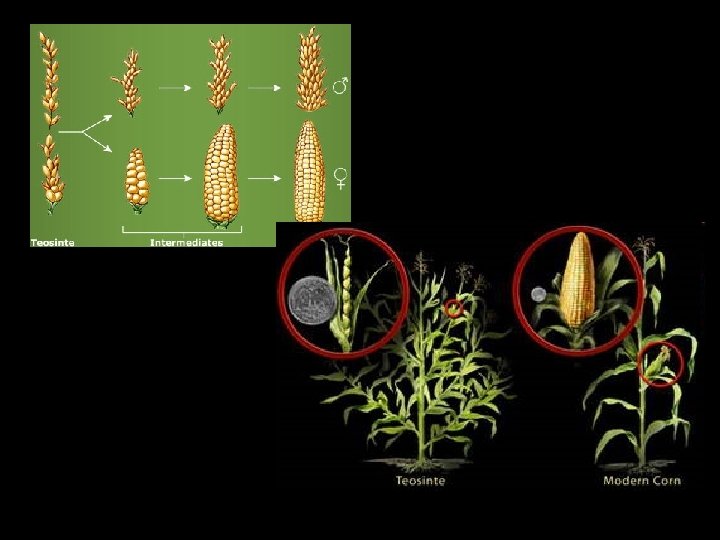

Domestication • Domestication = production of new species of plant and animals by human intervention and co-evolution – interference in the life cycles of plants and animals so subsequent generations are of greater utility for and in more intimate contact with humans – domestication demands increased dependence on humans, and vice versa – Domesticate defined as new species, having undergone some morphological change from wild species, but domestication as process more complicated than this; some full domesticates fully dependent on humans for survival.

Domestication and Management • Management and casual tending • Domestication: biological process that involves changes in the genotypes and phenotypes of plants and animals as they become dependent on humans for reproductive success (intentionality and co-evolution) • Cultivation: intentional preparation and management of planting areas • Herding: intentional changes in relations between humans and gregarious animals • Agriculture: commitment to this relationship between humans and plants and animals. Production of food and goods through farming and forestry. Agriculture was the key development that led to the rise of human civilization, with the husbandry of domesticated animals and plants (i. e. crops) creating food surpluses that enabled the development of more densely populated and stratified societies. • Population and Landscape domestication

Canis lupus 12/05 Canis lupus familiaris

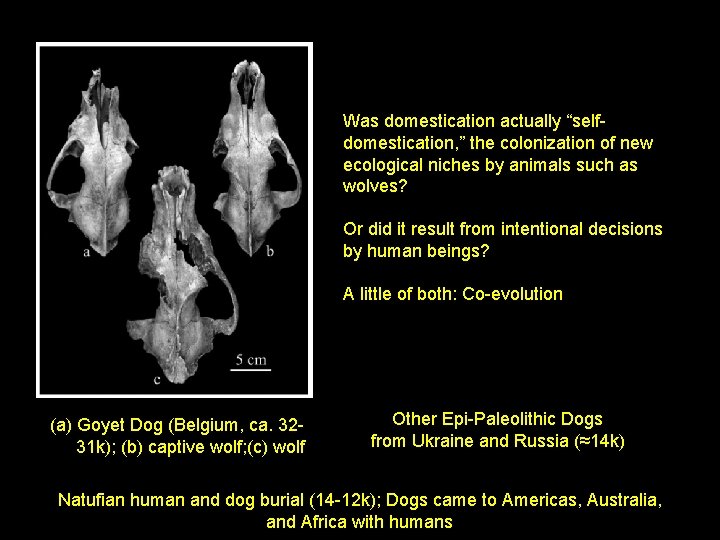

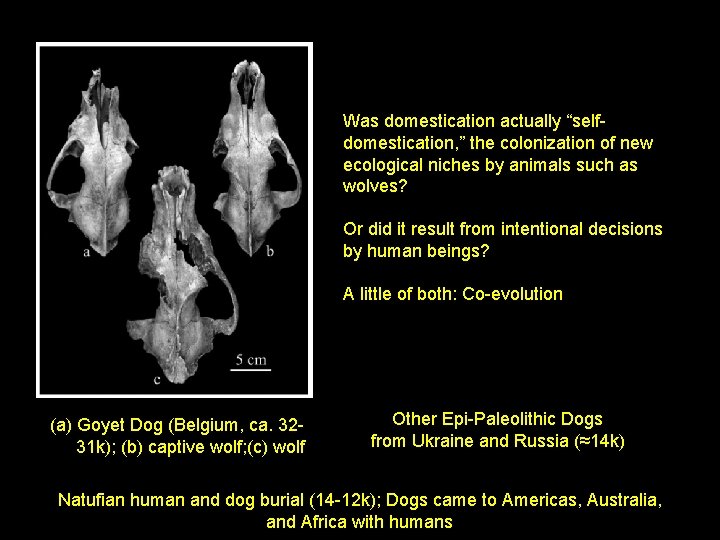

Was domestication actually “selfdomestication, ” the colonization of new ecological niches by animals such as wolves? Or did it result from intentional decisions by human beings? A little of both: Co-evolution (a) Goyet Dog (Belgium, ca. 3231 k); (b) captive wolf; (c) wolf Other Epi-Paleolithic Dogs from Ukraine and Russia (≈14 k) Natufian human and dog burial (14 -12 k); Dogs came to Americas, Australia, and Africa with humans

Paleolithic Dog DNA, 15 -100 k Geographic range of Canis lupus

Camp followers, new niche Dingos in Australia with humans

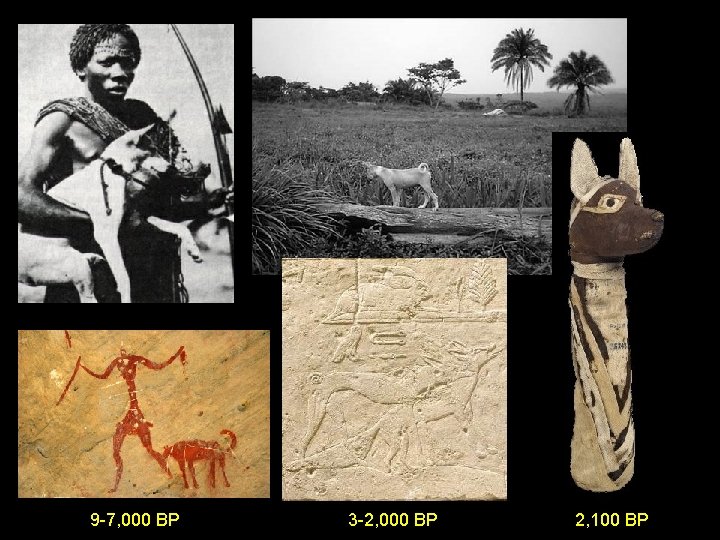

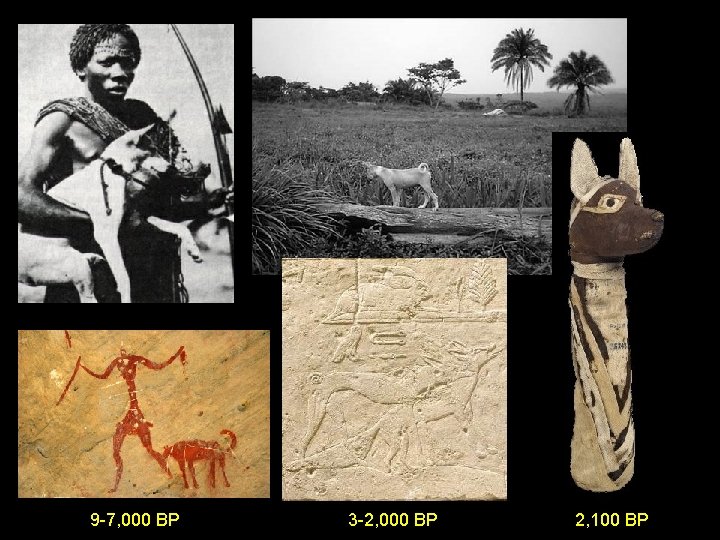

9 -7, 000 BP 3 -2, 000 BP 2, 100 BP

Dimitry Belyaev (late 1950 s) behavioral experiment: From a farm breed population of Silver Foxes (20 -30 generations to domesticate; 10 to usable levels) “To evaluate the foxes for tameness, we give them a series of tests. When a pup is one month old, an experimenter offers it food from his hand while trying to stroke and handle the pup. . The pups are tested twice, once in a cage and once while moving freely with other pups in an enclosure, where they can choose to make contact either with the human experimenter or with another pup. The test is repeated monthly until the pups are six or seven months old. At seven or eight months, when the foxes reach sexual maturity, they are scored for tameness and assigned to one of three classes. The least domesticated foxes, those that flee from experimenters or bite when stroked or handled, are assigned to Class III. (Even Class III foxes are tamer than the calmest farm-bred foxes. Among other things, they allow themselves to be hand fed. ) Foxes in Class II let themselves be petted and handled but show no emotionally friendly response to experimenters. Foxes in Class I are friendly toward experimenters, wagging their tails and whining. In the sixth generation bred for tameness we had to add an even higher-scoring category. Members of Class IE, the “domesticated elite, ” are eager to establish human contact, whimpering to attract attention and sniffing and licking experimenters like dogs. They start displaying this kind of behavior before they are one month old. By the tenth generation, 18 percent of fox pups were elite; by the 20 th, the figure had reached 35 percent. Today elite foxes make up 70 to 80 percent of our experimentally selected population. Now, 40 years and 45, 000 foxes after Belyaev began, our experiment has achieved an array of concrete results. The most obvious of them is a unique population of 100 foxes (at latest count), each of them the product of between 30 and 35 generations of selection. They are unusual animals, docile, eager to please and unmistakably domesticated. ” from L. Trut, American Scientist (1999)

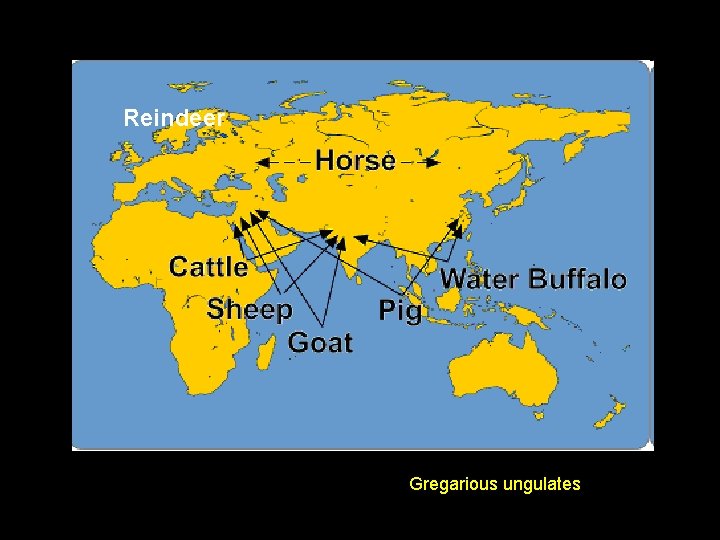

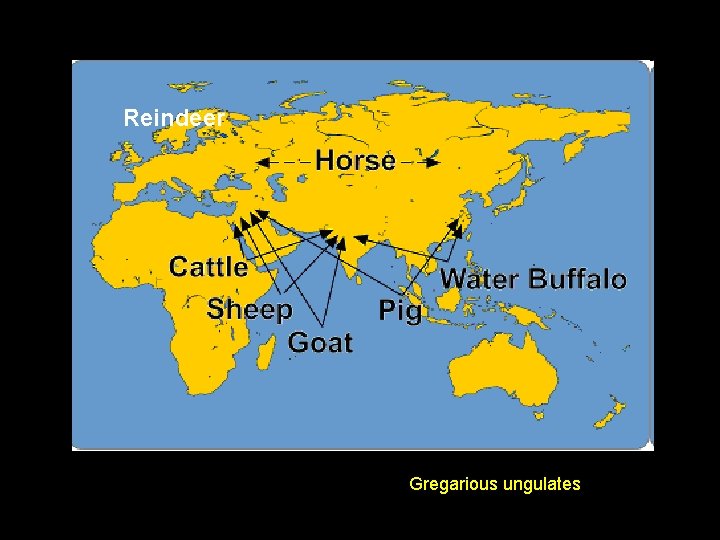

Darwin noted in chapter 1 of On the Origin of Species, “not a single domestic animal can be named which has not in some country drooping ears”—a feature not found in any wild animal except the elephant. • In a wide range of mammals— herbivores and predators, large and small — domestication seems to have brought with it strikingly similar changes in appearance and behavior: changes in size, changes in coat color, animals’ reproductive cycles, docility. • Of 148 large terrestrial herbivorous mammals, only 14 have been successfully domesticated

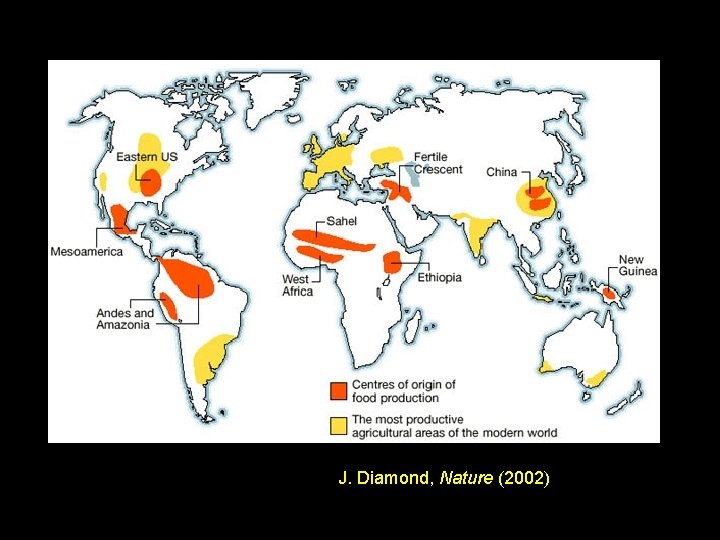

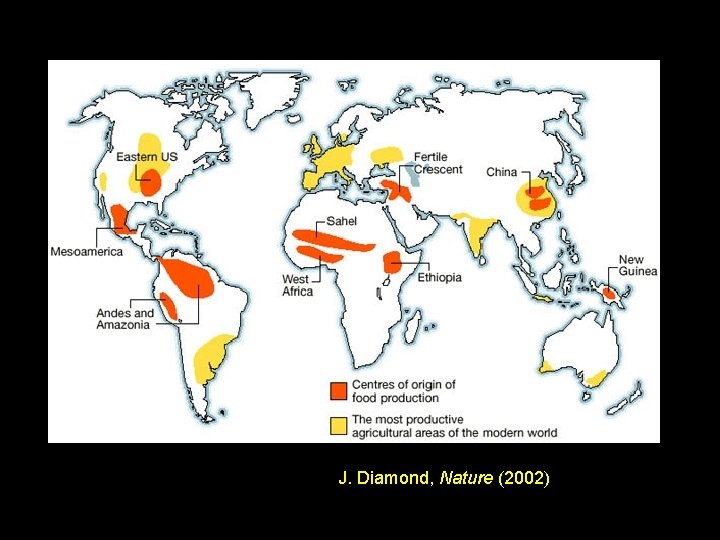

Among wild mammal species that were never domesticated, the six main obstacles proved to be a diet not easily supplied by humans (hence no domestic anteaters), slow growth rate and long birth spacing (for example, elephants and gorillas), nasty disposition (grizzly bears and rhinoceroses), reluctance to breed in captivity (pandas and cheetahs), lack of follow-the-leader dominance hierarchies (bighorn sheep and antelope), and tendency to panic in enclosures or when faced with predators (gazelles and deer, except reindeer). J. Diamond, Nature (2002)

Reindeer Gregarious ungulates

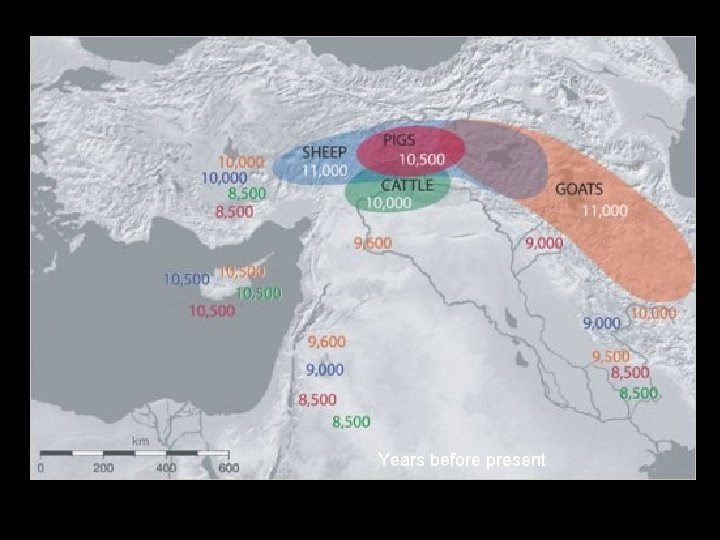

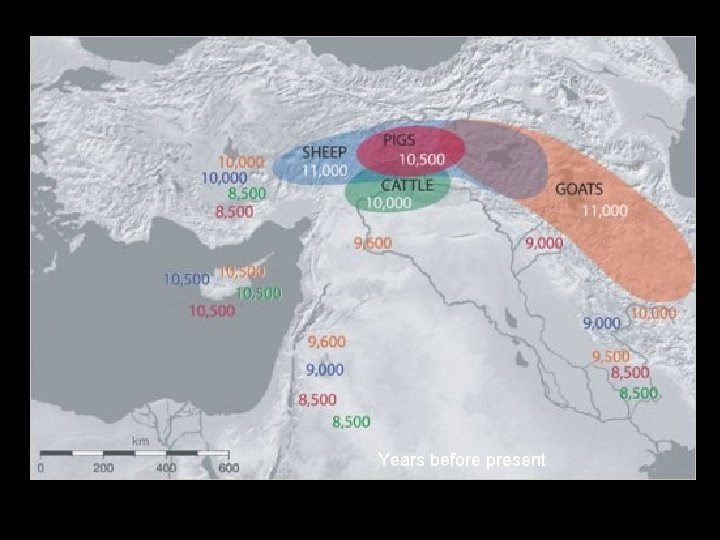

Years before present

Sus scrofa domesticus

Eurasian wild pig (Sus scrofa)

Geographic positions of European and Near Eastern pig haplotypes over the past 13, 000 years Larson G et al. PNAS 2007; 104: 15276 -15281

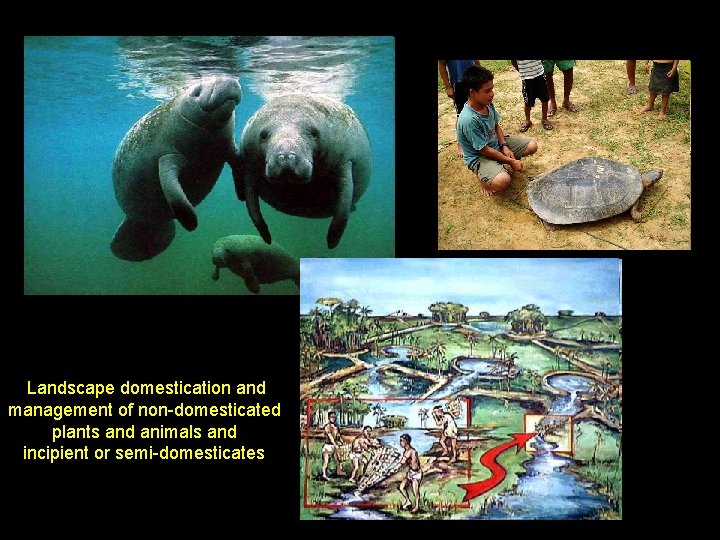

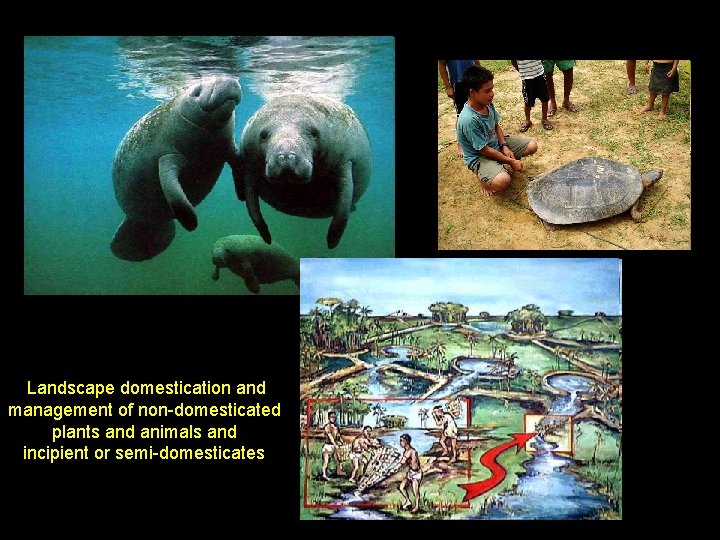

Landscape domestication and management of non-domesticated plants and animals and incipient or semi-domesticates

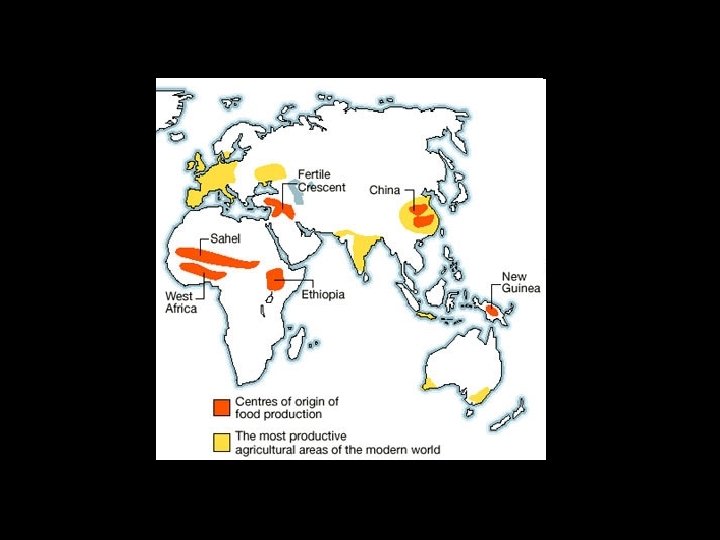

J. Diamond, Nature (2002)

Manioc

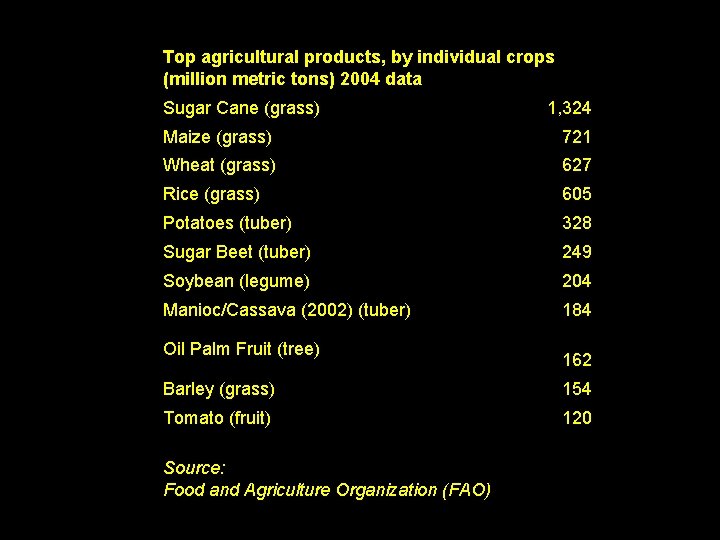

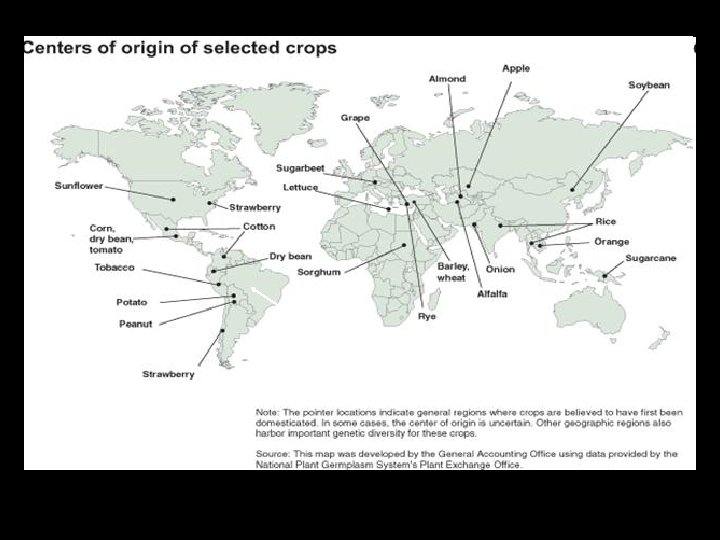

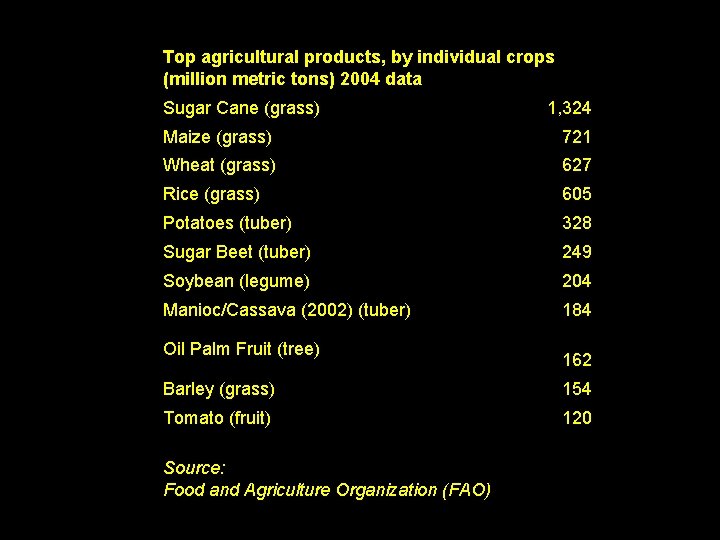

Top agricultural products, by individual crops (million metric tons) 2004 data Sugar Cane (grass) 1, 324 Maize (grass) 721 Wheat (grass) 627 Rice (grass) 605 Potatoes (tuber) 328 Sugar Beet (tuber) 249 Soybean (legume) 204 Manioc/Cassava (2002) (tuber) 184 Oil Palm Fruit (tree) 162 Barley (grass) 154 Tomato (fruit) 120 Source: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

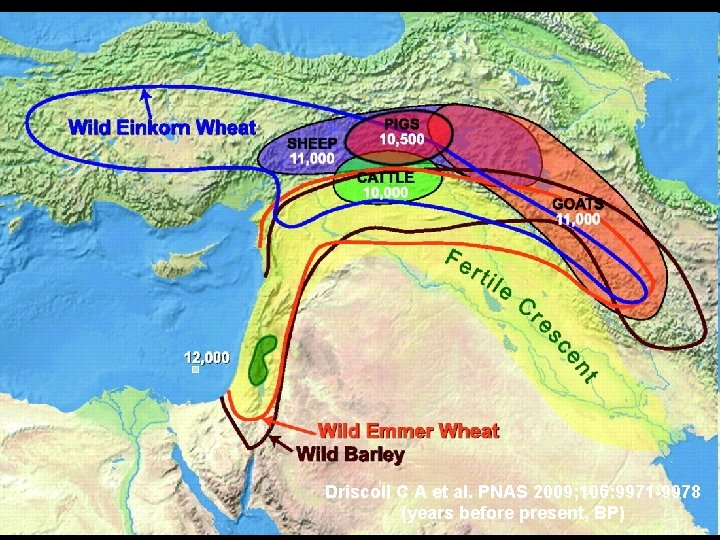

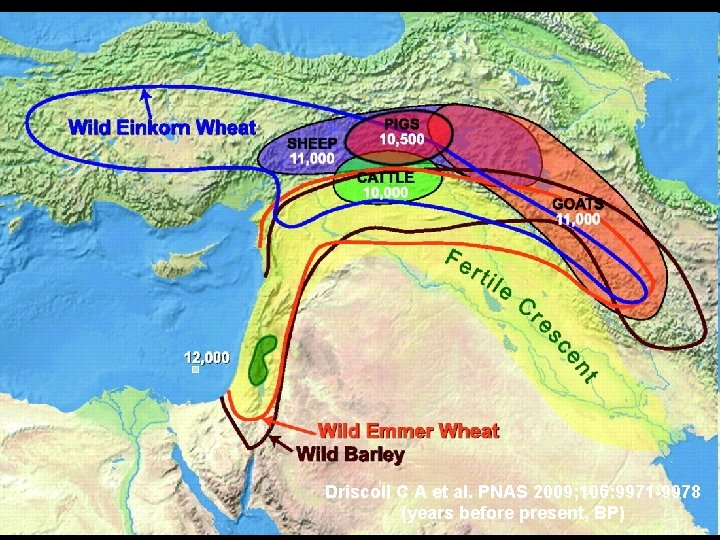

Driscoll C A et al. PNAS 2009; 106: 9971 -9978 (years before present, BP)

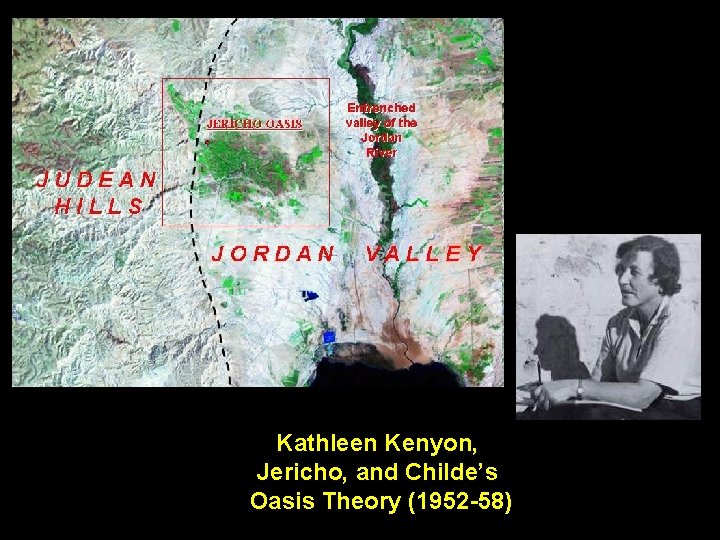

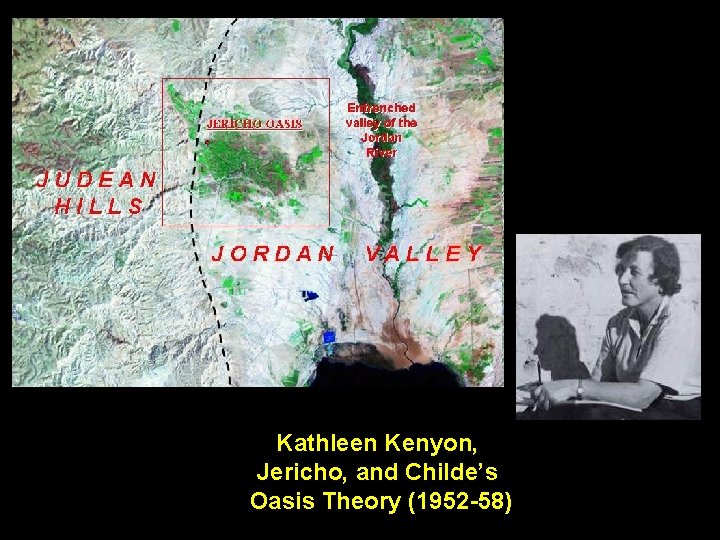

Levant Corridor (Jericho) Zagros Mountains (Jarmo)

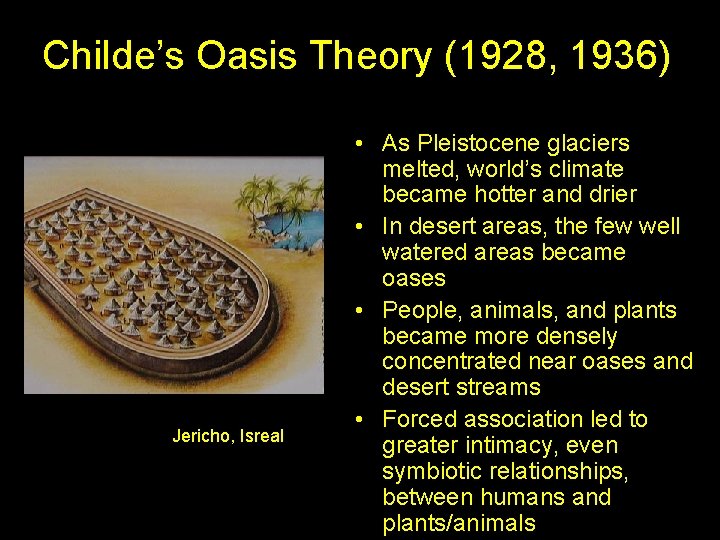

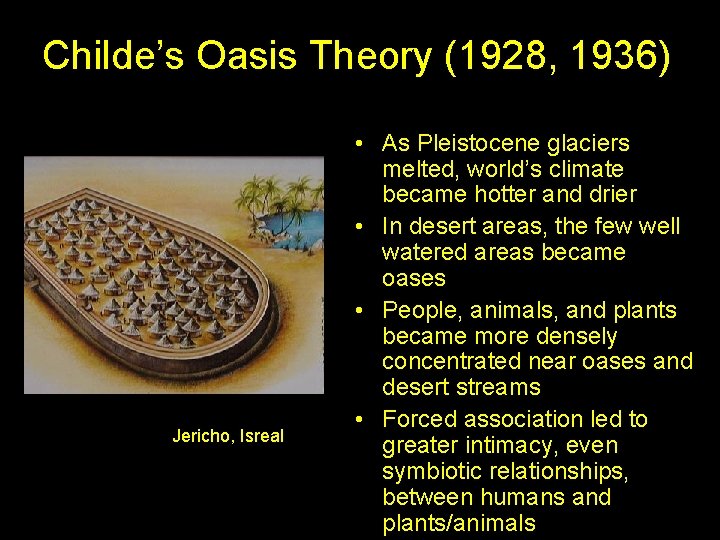

Childe’s Oasis Theory (1928, 1936) Jericho, Isreal • As Pleistocene glaciers melted, world’s climate became hotter and drier • In desert areas, the few well watered areas became oases • People, animals, and plants became more densely concentrated near oases and desert streams • Forced association led to greater intimacy, even symbiotic relationships, between humans and plants/animals

Kathleen Kenyon, Jericho, and Childe’s Oasis Theory (1952 -58)

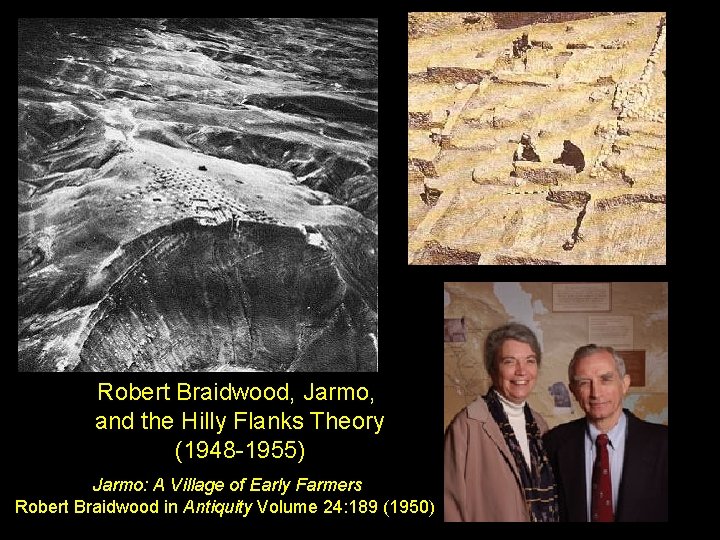

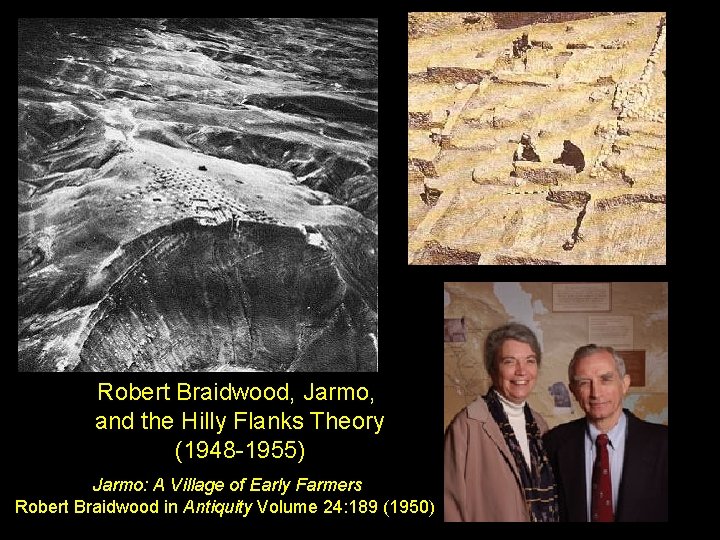

Braidwood’s Hilly Flanks Theory • Hilly flanks of Zagros Mountains, Iraq: rich natural habitat for wild grasses (natural habitat zone hypothesis; Peake-Fleur, 1927) • No evidence of dramatic post-Pleistocene dessication • Agriculture was logical outcome of cultural experimentation and elaboration as huntersgatherers settled-in in those areas where wild grasses were present • Like Childe’s model, assumes agriculture is logical outcome of humanity seeking to improve its condition

Robert Braidwood, Jarmo, and the Hilly Flanks Theory (1948 -1955) Jarmo: A Village of Early Farmers Robert Braidwood in Antiquity Volume 24: 189 (1950)

Farming Towns • Food production and more sedentary ways of life resulted in growth in settlement size and provided foundation for numerous cultural innovations outside of subsistence • Domestication and settled village life were traditionally seen as happening more or less simultaneously, although more recent research shows a more complicated story

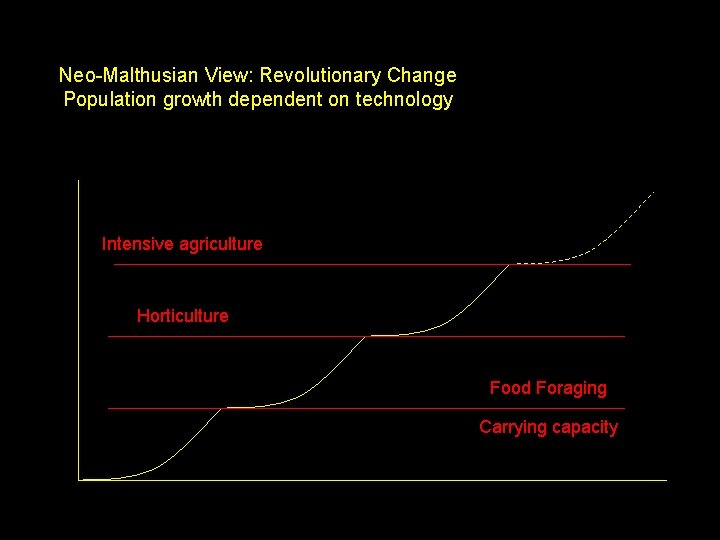

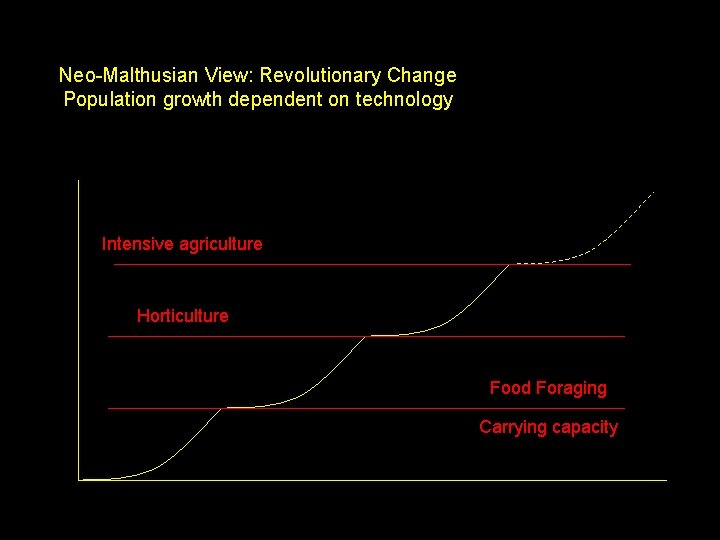

Thomas Malthus • An essay on the principle of population as it affects the future improvement of society (1798) • Population naturally grows until something dramatic occurs Population growth kept in check through mortality (misery, war, famine, epidemics) Neo-Malthusian premise: population growth is dependent variable, determined by preceding changes in subsistence potential as population reaches critical threshold, or “carrying capacity, ” population growth is checked (held in place) by some cultural or natural factor (contraception, infanticide, disease, famine) • • •

Neo-Malthusian View: Revolutionary Change Population growth dependent on technology Intensive agriculture Horticulture Food Foraging Carrying capacity

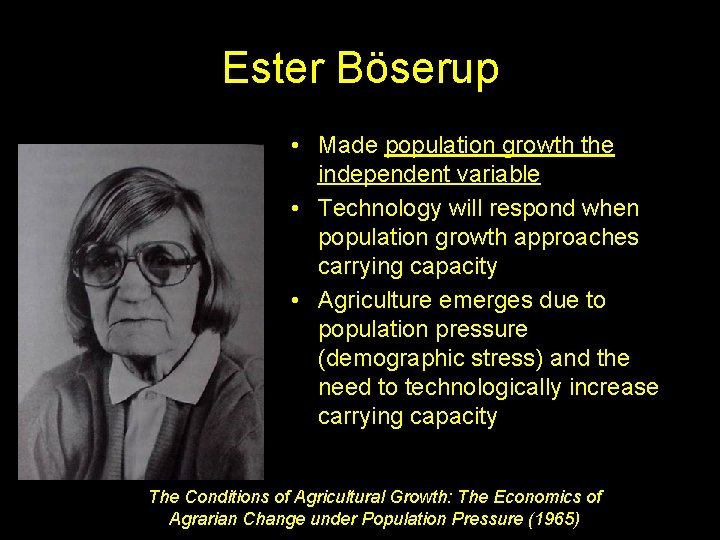

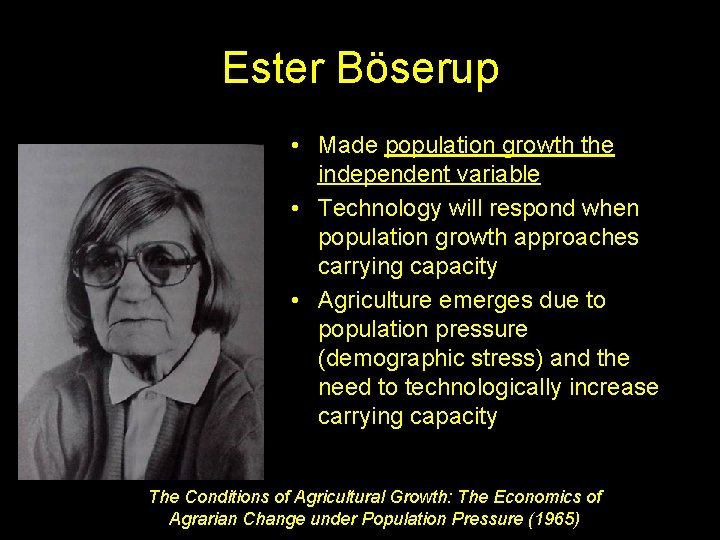

Ester Böserup • Made population growth the independent variable • Technology will respond when population growth approaches carrying capacity • Agriculture emerges due to population pressure (demographic stress) and the need to technologically increase carrying capacity The Conditions of Agricultural Growth: The Economics of Agrarian Change under Population Pressure (1965)

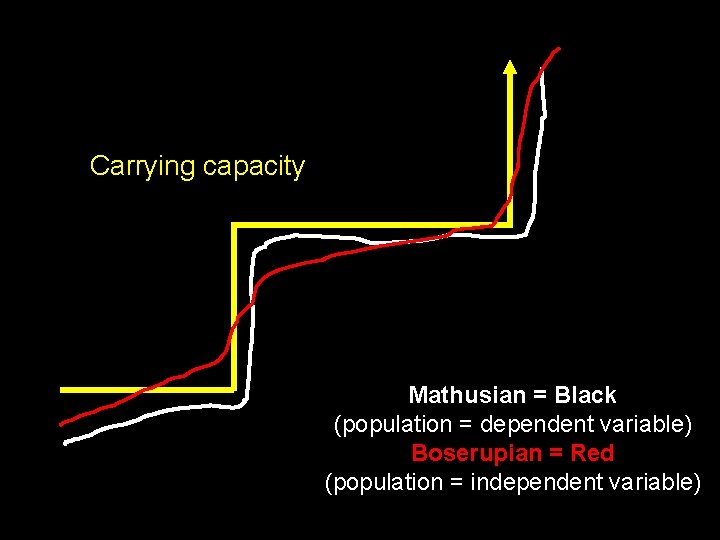

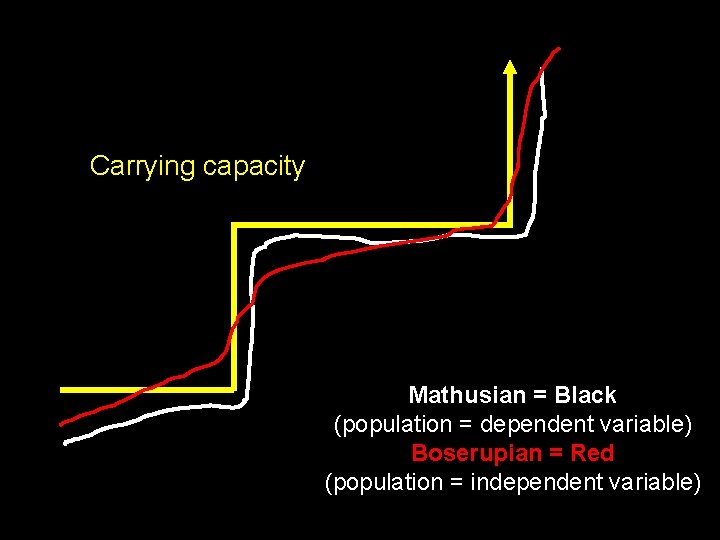

Carrying capacity Mathusian = Black (population = dependent variable) Boserupian = Red (population = independent variable)

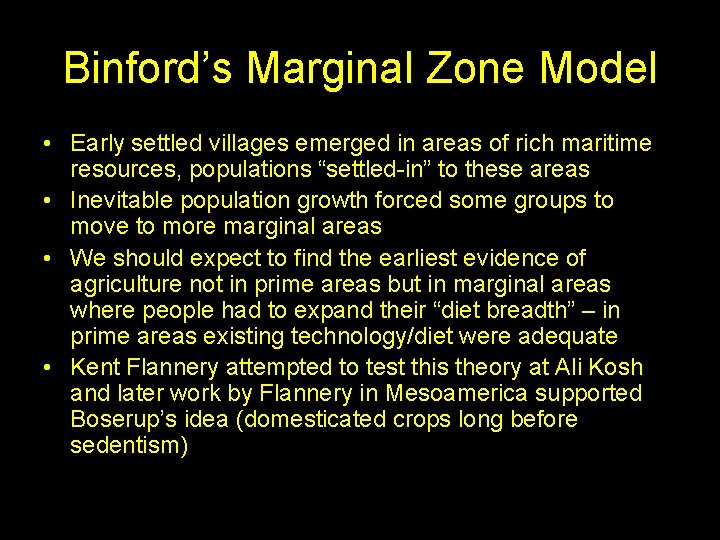

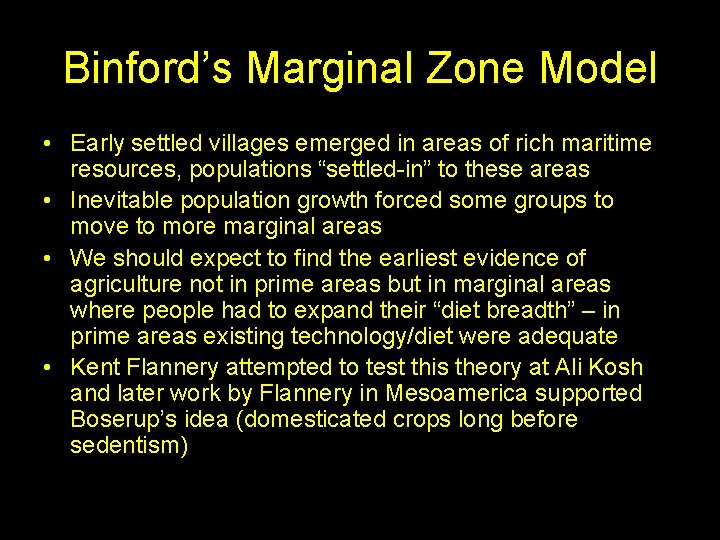

Binford’s Marginal Zone Model • Early settled villages emerged in areas of rich maritime resources, populations “settled-in” to these areas • Inevitable population growth forced some groups to move to more marginal areas • We should expect to find the earliest evidence of agriculture not in prime areas but in marginal areas where people had to expand their “diet breadth” – in prime areas existing technology/diet were adequate • Kent Flannery attempted to test this theory at Ali Kosh and later work by Flannery in Mesoamerica supported Boserup’s idea (domesticated crops long before sedentism)

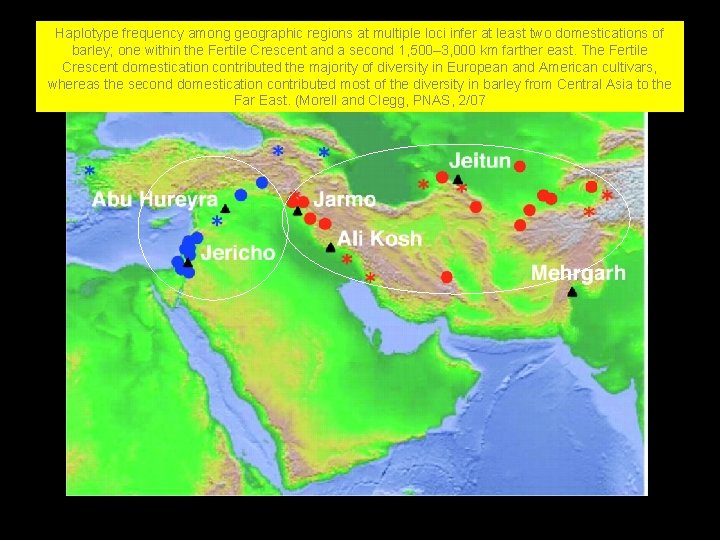

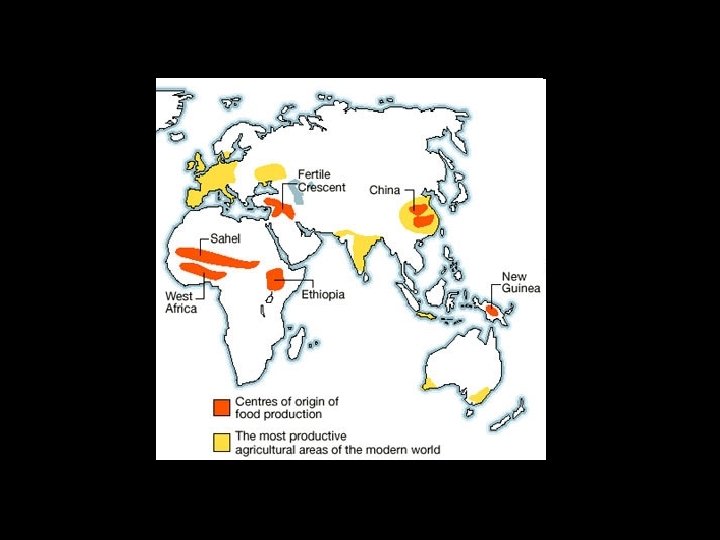

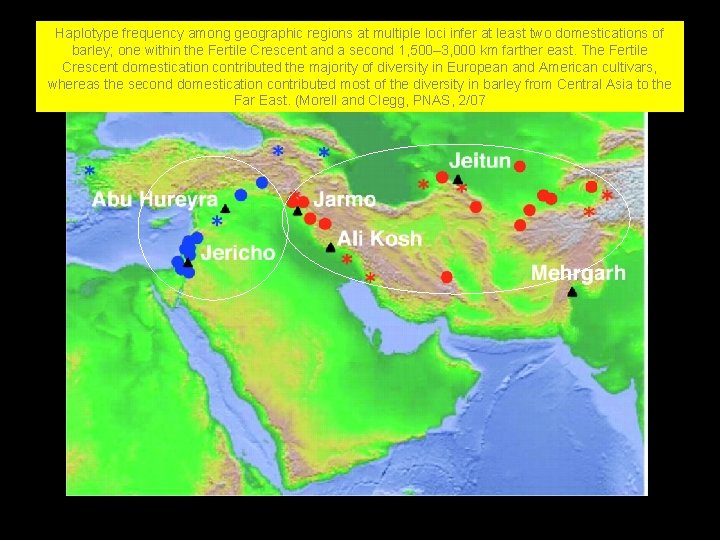

Haplotype frequency among geographic regions at multiple loci infer at least two domestications of barley; one within the Fertile Crescent and a second 1, 500– 3, 000 km farther east. The Fertile Crescent domestication contributed the majority of diversity in European and American cultivars, whereas the second domestication contributed most of the diversity in barley from Central Asia to the Far East. (Morell and Clegg, PNAS, 2/07

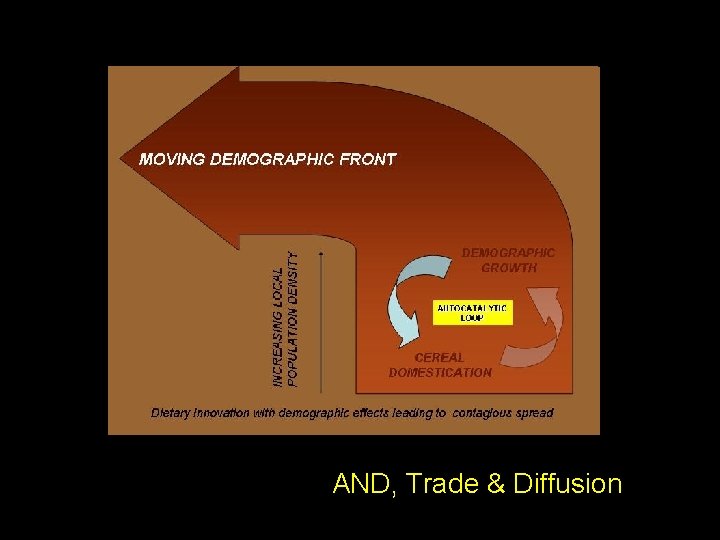

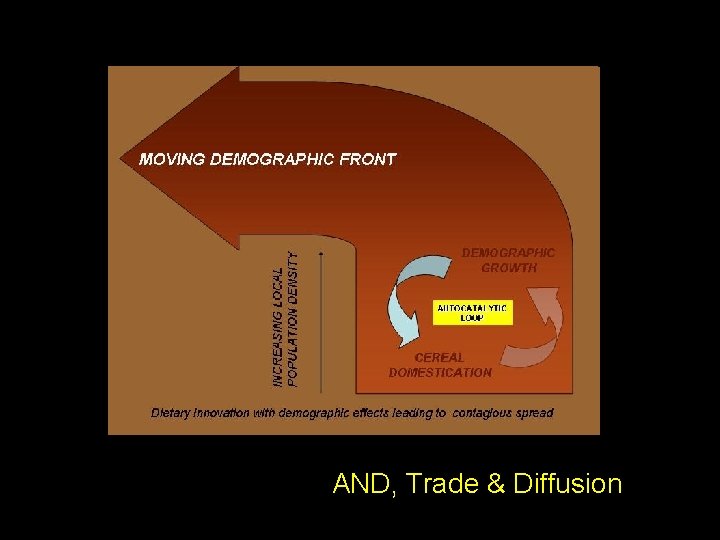

AND, Trade & Diffusion

7300 BP Balkans 7500 BP Macedonia 8000 BP Anatolia 8700 BP Franchti Cave Crete Cyprus 10, 000 BP E. Med. /Jordan valley

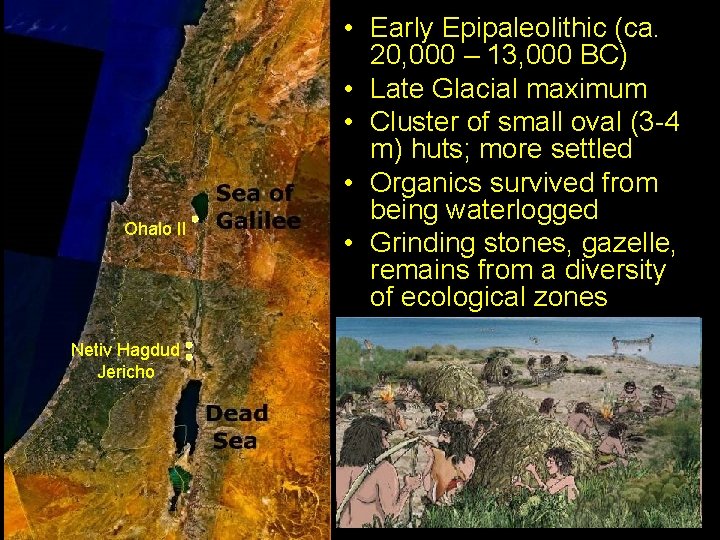

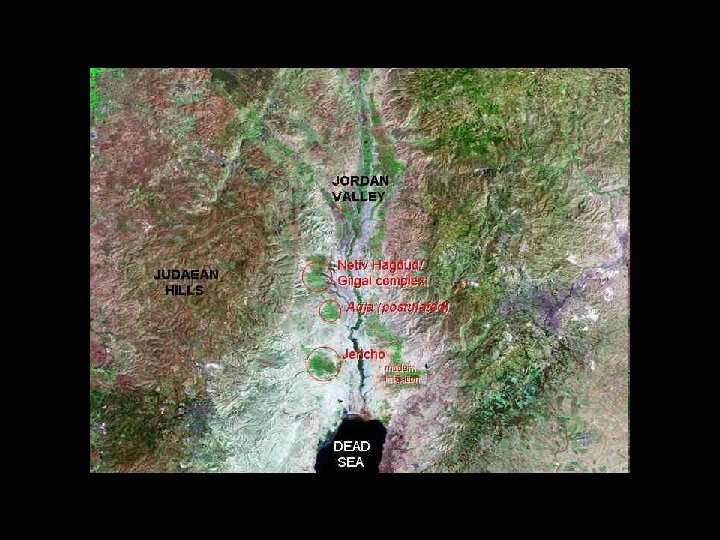

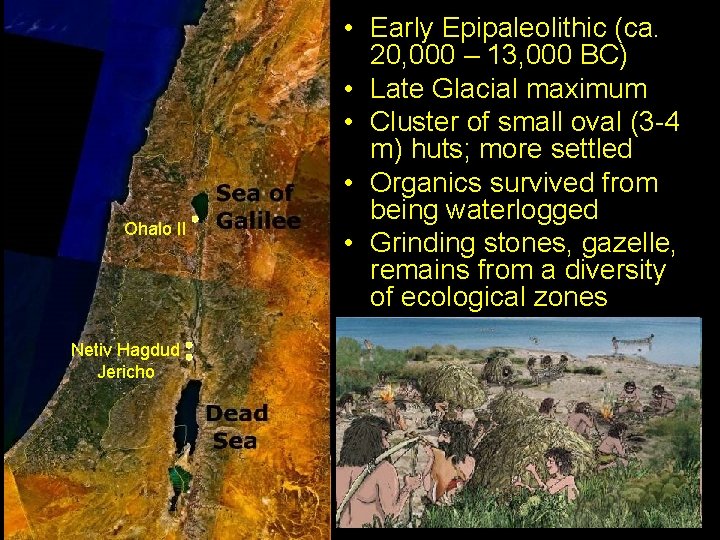

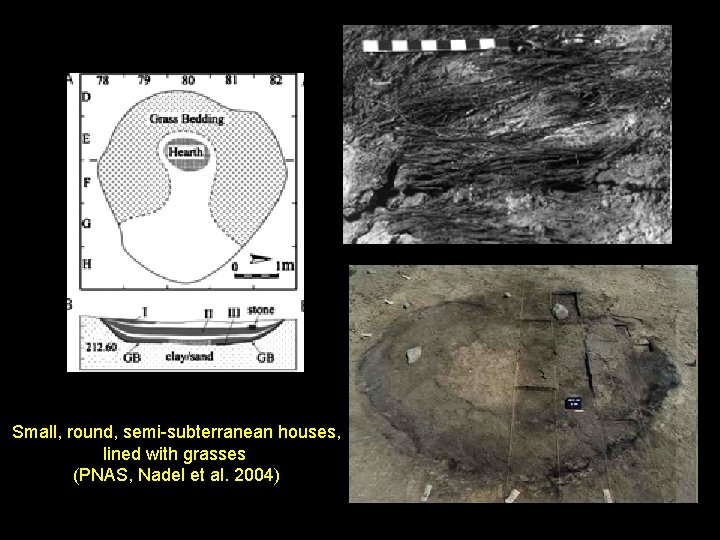

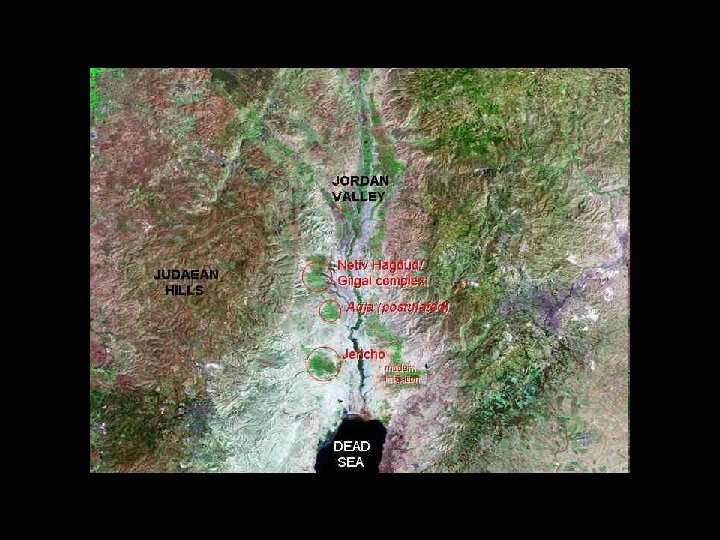

Ohalo II Netiv Hagdud Jericho • Early Epipaleolithic (ca. 20, 000 – 13, 000 BC) • Late Glacial maximum • Cluster of small oval (3 -4 m) huts; more settled • Organics survived from being waterlogged • Grinding stones, gazelle, remains from a diversity of ecological zones

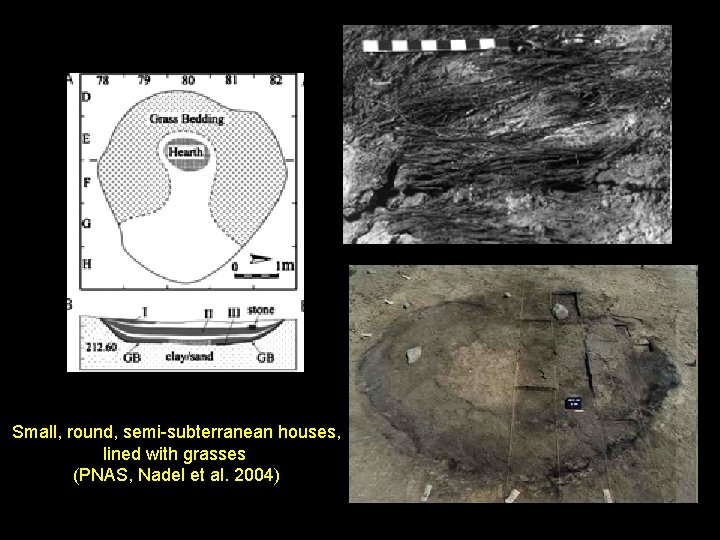

Small, round, semi-subterranean houses, lined with grasses (PNAS, Nadel et al. 2004)

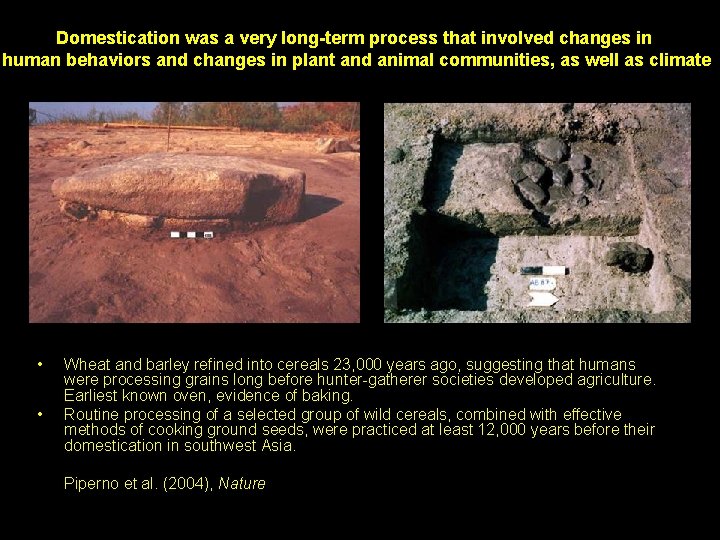

Domestication was a very long-term process that involved changes in human behaviors and changes in plant and animal communities, as well as climate • • Wheat and barley refined into cereals 23, 000 years ago, suggesting that humans were processing grains long before hunter-gatherer societies developed agriculture. Earliest known oven, evidence of baking. Routine processing of a selected group of wild cereals, combined with effective methods of cooking ground seeds, were practiced at least 12, 000 years before their domestication in southwest Asia. Piperno et al. (2004), Nature

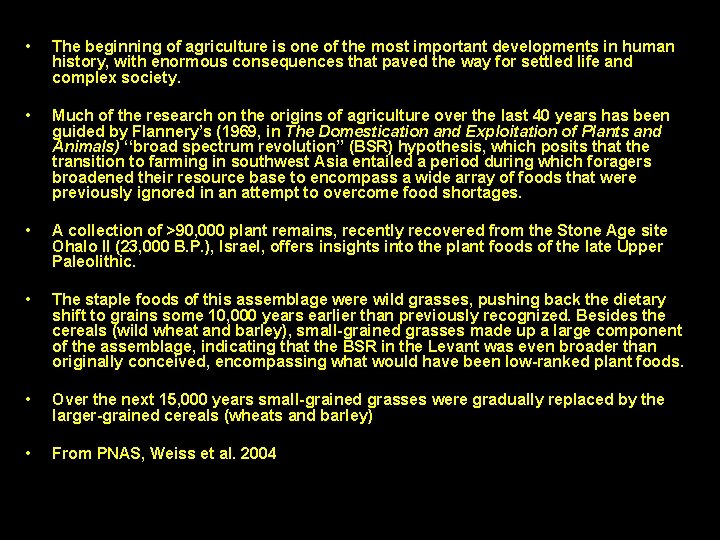

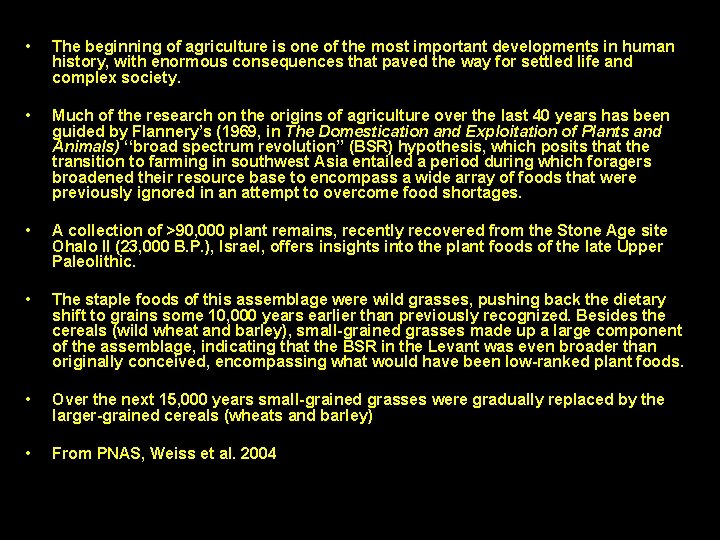

• The beginning of agriculture is one of the most important developments in human history, with enormous consequences that paved the way for settled life and complex society. • Much of the research on the origins of agriculture over the last 40 years has been guided by Flannery’s (1969, in The Domestication and Exploitation of Plants and Animals) ‘‘broad spectrum revolution’’ (BSR) hypothesis, which posits that the transition to farming in southwest Asia entailed a period during which foragers broadened their resource base to encompass a wide array of foods that were previously ignored in an attempt to overcome food shortages. • A collection of >90, 000 plant remains, recently recovered from the Stone Age site Ohalo II (23, 000 B. P. ), Israel, offers insights into the plant foods of the late Upper Paleolithic. • The staple foods of this assemblage were wild grasses, pushing back the dietary shift to grains some 10, 000 years earlier than previously recognized. Besides the cereals (wild wheat and barley), small-grained grasses made up a large component of the assemblage, indicating that the BSR in the Levant was even broader than originally conceived, encompassing what would have been low-ranked plant foods. • Over the next 15, 000 years small-grained grasses were gradually replaced by the larger-grained cereals (wheats and barley) • From PNAS, Weiss et al. 2004

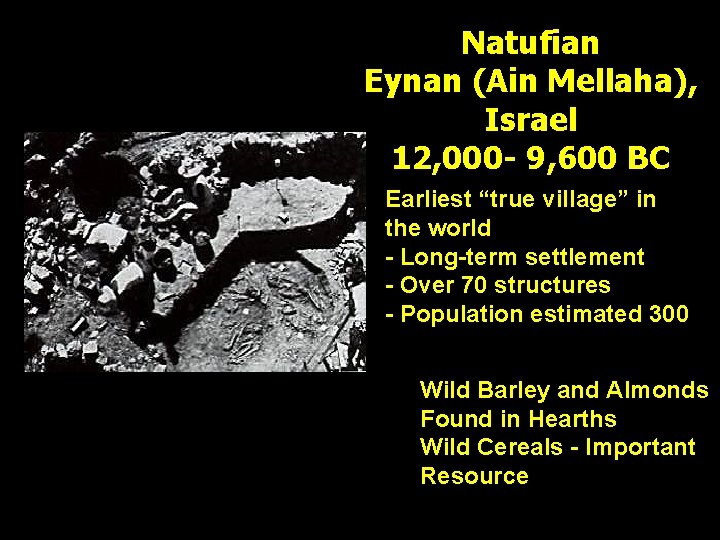

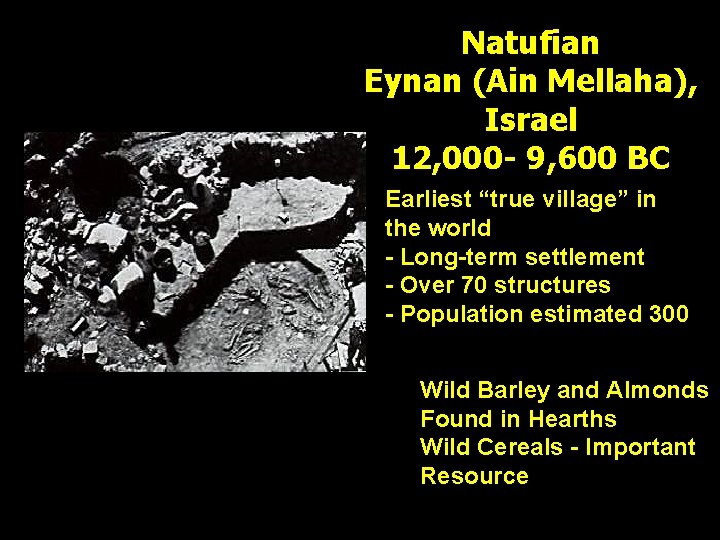

Natufian Eynan (Ain Mellaha), Israel 12, 000 - 9, 600 BC Earliest “true village” in the world - Long-term settlement - Over 70 structures - Population estimated 300 Wild Barley and Almonds Found in Hearths Wild Cereals - Important Resource

Netiv Hagdud, Israel • Very early evidence of domesticated plants (c. 11, 800 -11, 500 BP) • Hunting gazelle, fish, waterfowl, 50 species of wild plants, especially wild cereal grasses harvested with sickles (included a semi-tough rachis, two-row domesticated barley) • Mud-houses, cereals stored in bins • Cereal seeds– supplementary food

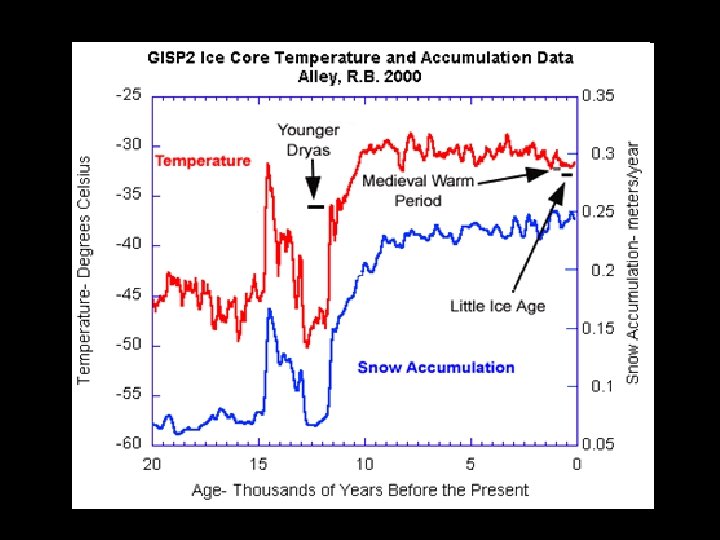

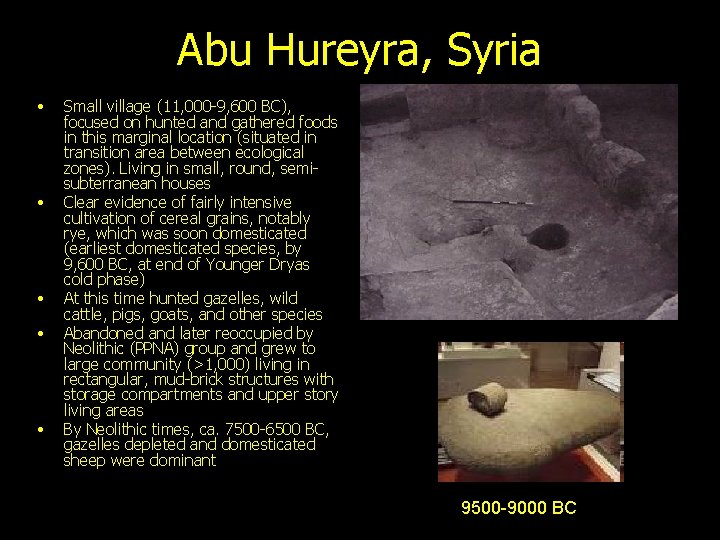

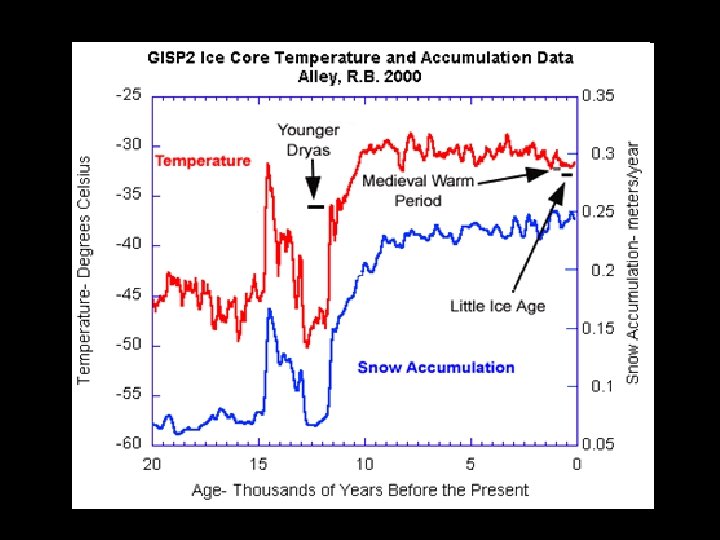

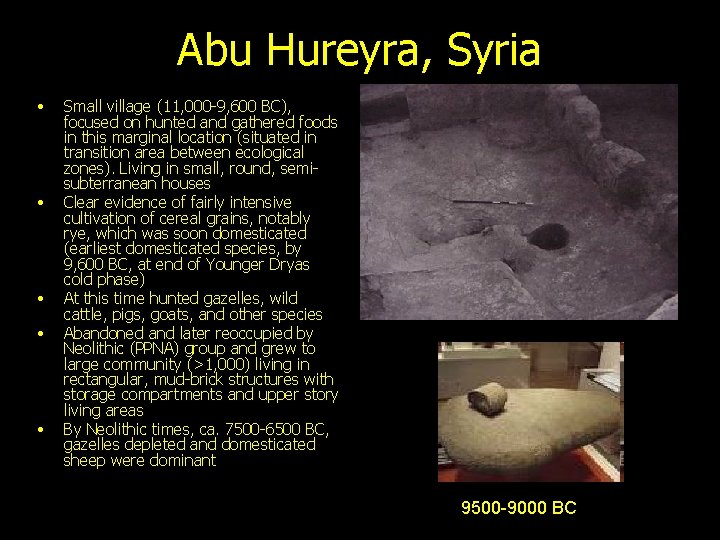

Abu Hureyra, Syria • • • Small village (11, 000 -9, 600 BC), focused on hunted and gathered foods in this marginal location (situated in transition area between ecological zones). Living in small, round, semisubterranean houses Clear evidence of fairly intensive cultivation of cereal grains, notably rye, which was soon domesticated (earliest domesticated species, by 9, 600 BC, at end of Younger Dryas cold phase) At this time hunted gazelles, wild cattle, pigs, goats, and other species Abandoned and later reoccupied by Neolithic (PPNA) group and grew to large community (>1, 000) living in rectangular, mud-brick structures with storage compartments and upper story living areas By Neolithic times, ca. 7500 -6500 BC, gazelles depleted and domesticated sheep were dominant 9500 -9000 BC

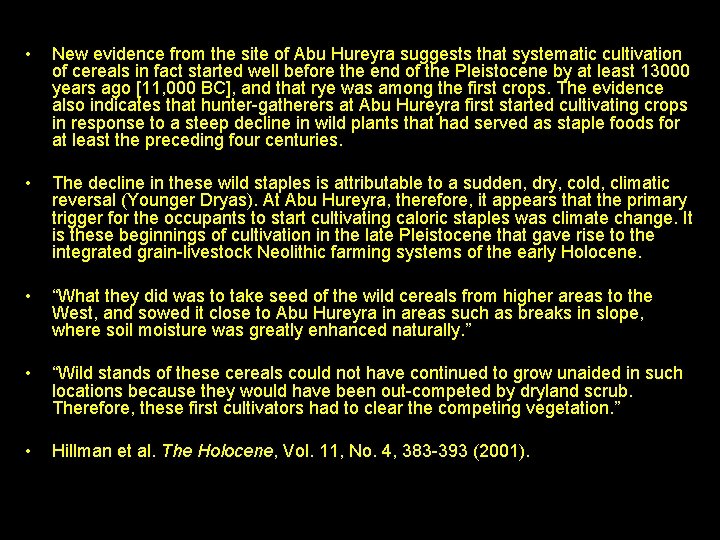

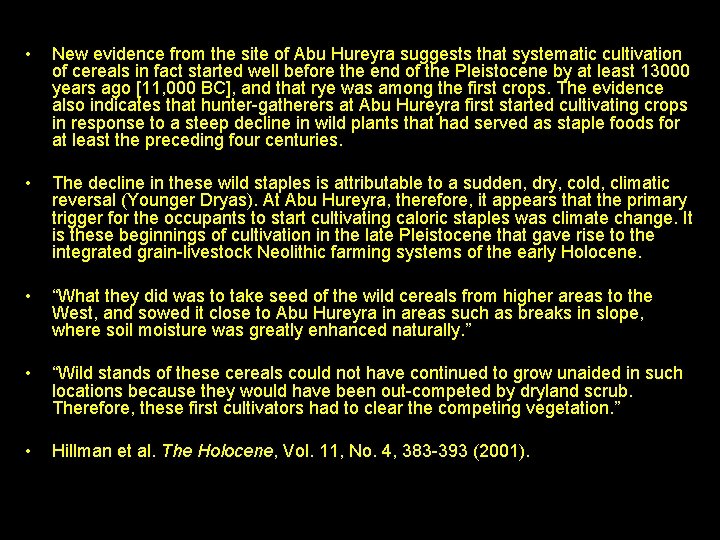

• New evidence from the site of Abu Hureyra suggests that systematic cultivation of cereals in fact started well before the end of the Pleistocene by at least 13000 years ago [11, 000 BC], and that rye was among the first crops. The evidence also indicates that hunter-gatherers at Abu Hureyra first started cultivating crops in response to a steep decline in wild plants that had served as staple foods for at least the preceding four centuries. • The decline in these wild staples is attributable to a sudden, dry, cold, climatic reversal (Younger Dryas). At Abu Hureyra, therefore, it appears that the primary trigger for the occupants to start cultivating caloric staples was climate change. It is these beginnings of cultivation in the late Pleistocene that gave rise to the integrated grain-livestock Neolithic farming systems of the early Holocene. • “What they did was to take seed of the wild cereals from higher areas to the West, and sowed it close to Abu Hureyra in areas such as breaks in slope, where soil moisture was greatly enhanced naturally. ” • “Wild stands of these cereals could not have continued to grow unaided in such locations because they would have been out-competed by dryland scrub. Therefore, these first cultivators had to clear the competing vegetation. ” • Hillman et al. The Holocene, Vol. 11, No. 4, 383 -393 (2001).

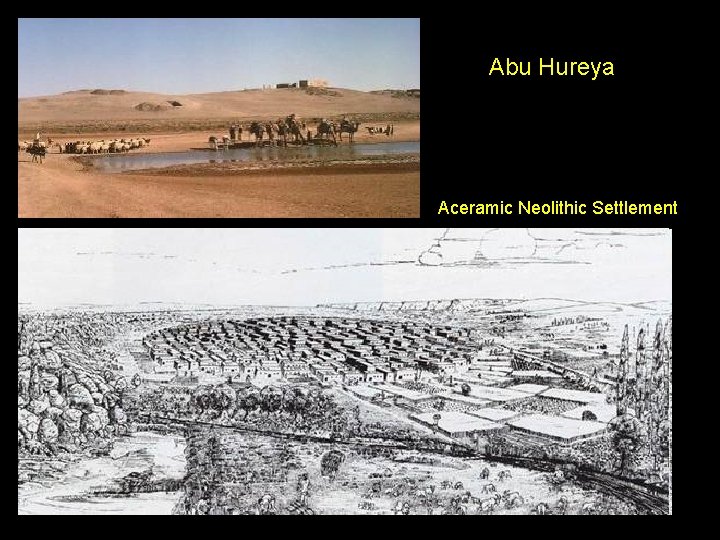

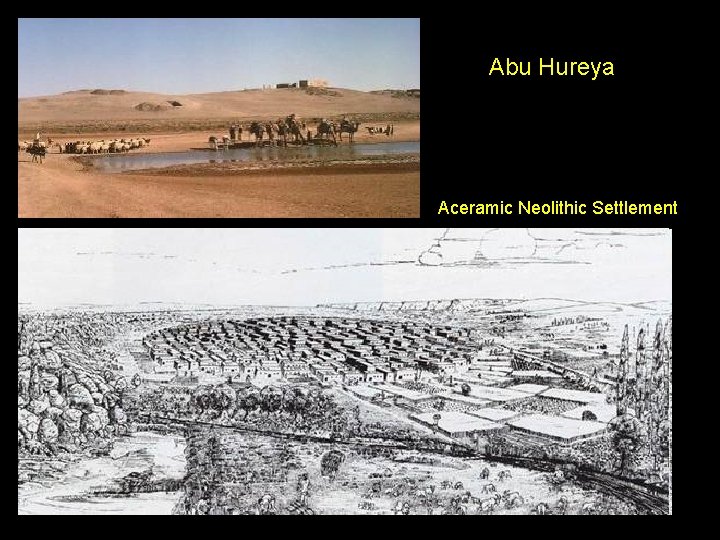

Abu Hureya Aceramic Neolithic Settlement

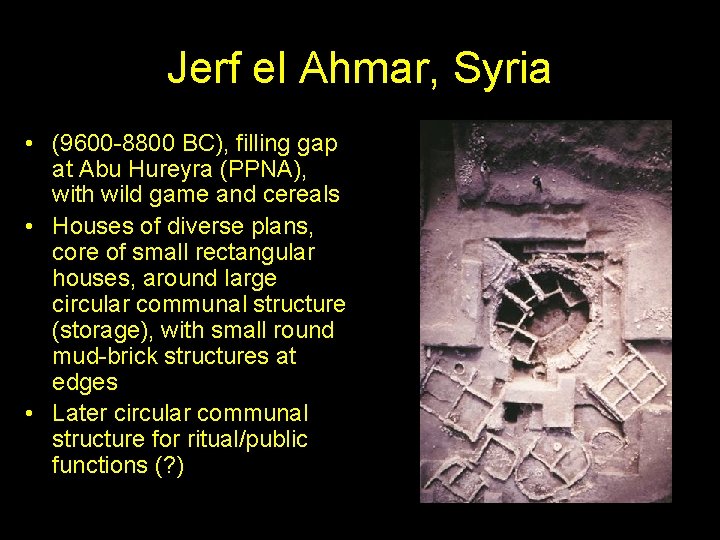

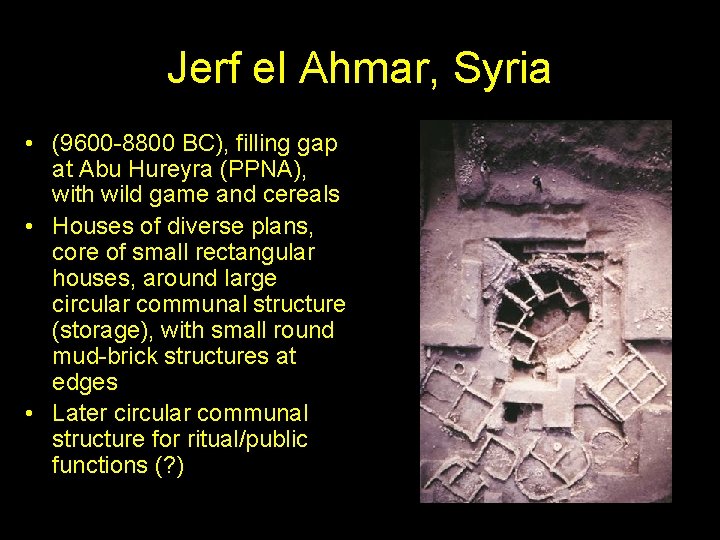

Jerf el Ahmar, Syria • (9600 -8800 BC), filling gap at Abu Hureyra (PPNA), with wild game and cereals • Houses of diverse plans, core of small rectangular houses, around large circular communal structure (storage), with small round mud-brick structures at edges • Later circular communal structure for ritual/public functions (? )

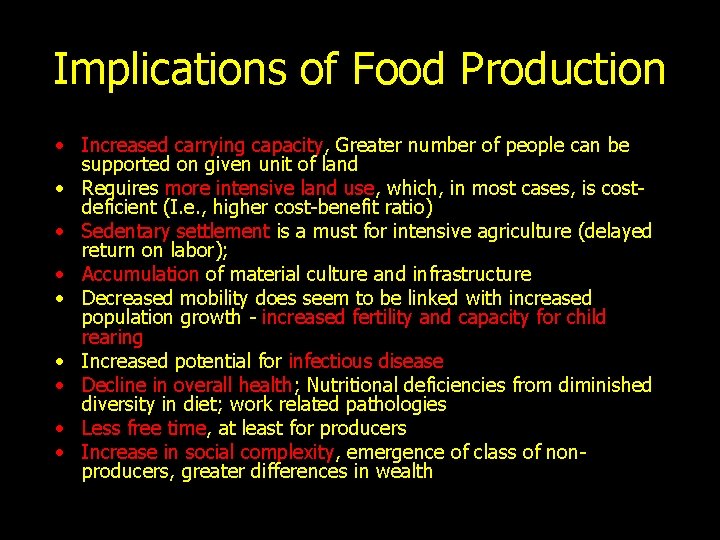

Implications of Food Production • Increased carrying capacity, Greater number of people can be supported on given unit of land • Requires more intensive land use, which, in most cases, is costdeficient (I. e. , higher cost-benefit ratio) • Sedentary settlement is a must for intensive agriculture (delayed return on labor); • Accumulation of material culture and infrastructure • Decreased mobility does seem to be linked with increased population growth - increased fertility and capacity for child rearing • Increased potential for infectious disease • Decline in overall health; Nutritional deficiencies from diminished diversity in diet; work related pathologies • Less free time, at least for producers • Increase in social complexity, emergence of class of nonproducers, greater differences in wealth

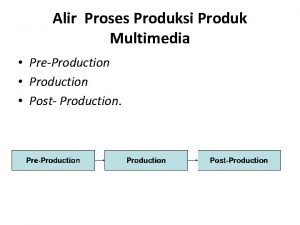

Pengertian post production

Pengertian post production Domestication

Domestication Domestication of animals

Domestication of animals Domestication

Domestication Domestication

Domestication Schleiermacher on the different methods of translating

Schleiermacher on the different methods of translating Plant keystone species

Plant keystone species Mh 605

Mh 605 The gradual change in a species over time

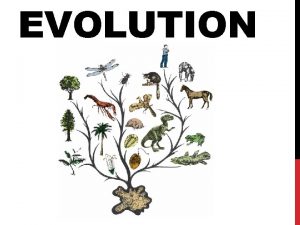

The gradual change in a species over time The gradual change in a species over time is

The gradual change in a species over time is What is evolution and natural selection

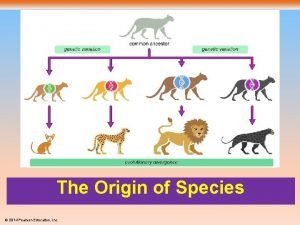

What is evolution and natural selection Describe the conditions under which new species may arise.

Describe the conditions under which new species may arise. Speciation or the formation of new species is

Speciation or the formation of new species is Why does new guinea have more species of birds than bali?

Why does new guinea have more species of birds than bali? The process by which new species originate

The process by which new species originate Topic xiv

Topic xiv New york state environmental facilities corporation

New york state environmental facilities corporation Unit 2 demand supply and consumer choice worksheet

Unit 2 demand supply and consumer choice worksheet S&d analysis practice

S&d analysis practice New grilling technology cuts production time in half

New grilling technology cuts production time in half Painting the wall physical change or chemical change

Painting the wall physical change or chemical change Chemical vs physical change

Chemical vs physical change Absolute change and relative change formula

Absolute change and relative change formula Define integers

Define integers Difference in physical and chemical changes

Difference in physical and chemical changes Decrease in supply vs decrease in quantity supplied

Decrease in supply vs decrease in quantity supplied Change in supply and change in quantity supplied

Change in supply and change in quantity supplied Change your water change your life

Change your water change your life Proactive and reactive change

Proactive and reactive change Which is an example of a physical change

Which is an example of a physical change Spare change physical versus chemical change

Spare change physical versus chemical change Rocks change due to temperature and pressure change

Rocks change due to temperature and pressure change Whats the difference between physical and chemical change

Whats the difference between physical and chemical change Physical change

Physical change Chemical change baking

Chemical change baking Second order change

Second order change Chopping wood is a physical or chemical change

Chopping wood is a physical or chemical change Climate change 2014 mitigation of climate change

Climate change 2014 mitigation of climate change Why do new ideas spark change

Why do new ideas spark change Chapter 14 a new spirit of change

Chapter 14 a new spirit of change Split speech punctuation

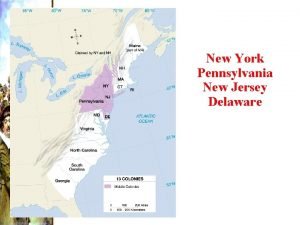

Split speech punctuation New york pennsylvania new jersey delaware

New york pennsylvania new jersey delaware Fresh oil, new wine scripture

Fresh oil, new wine scripture Orchard 14

Orchard 14 Strengths of articles of confederation

Strengths of articles of confederation New-old approach to creating new ventures

New-old approach to creating new ventures New marketing realities

New marketing realities Njbta

Njbta New classical macroeconomics

New classical macroeconomics Chapter 16 toward a new heaven and a new earth

Chapter 16 toward a new heaven and a new earth Both new hampshire and new york desire more territory

Both new hampshire and new york desire more territory New classical and new keynesian macroeconomics

New classical and new keynesian macroeconomics Comparing the progressive presidents

Comparing the progressive presidents Exotic species definition biology

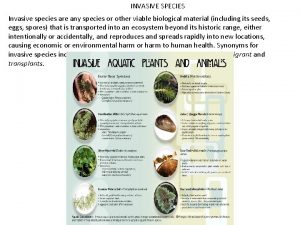

Exotic species definition biology What does a human embryo look like

What does a human embryo look like