Energy Storage and The Integration of Renewable Energy

Energy Storage and The Integration of Renewable Energy Into The Grid University of Colorado at Boulder Department of Electrical, Computer, and Energy Engineering Energy Storage Research Group Frank S Barnes frank. barnes@colorado. edu 303. 492. 8225 http: //www. colorado. edu/engineering/energystorage/

Acknowledgements The work leading to this talk was conducted by • • Jonah Levine Michelle Lim Mohit Chhabra Brad Lutz Greg Martin Muhammad Awan Taha Harnesswala • Richard Moutoux • Camelia Bouf • Kimberly Newman 2

Outline of Our Work 1. Potential Location of Pumped Hydroelectric Storage in Colorado 2. Issues in Compressed Air Storage at 1500 m in Eastern Colorado 3. The use of battery storage for frequency control and voltage regulation 4. Feed In Angle for Solar Power 5. The Optimization of Energy Use in Water Systems. 6. Detection of Power Theft 7. Optimization of Energy Use in Water 3

Obstacles to Integration of Wind and Solar Energy The Variability of Wind, Solar and Hydroelectric Power and Mismatch to the Loads 2. The Integration and Control of a Large Number of Distributed Sources in to the Grid 3. Lack of low cost convenient energy storage systems 1. 4

![San Luis Valley Solar Data (09/11/2010) Good Day [1] 5 San Luis Valley Solar Data (09/11/2010) Good Day [1] 5](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/2e4c17cc6d31a9c0c058e9934c378a10/image-5.jpg)

San Luis Valley Solar Data (09/11/2010) Good Day [1] 5

![San Luis Valley Solar Data (09/12/2010) Bad Day [1] 6 San Luis Valley Solar Data (09/12/2010) Bad Day [1] 6](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/2e4c17cc6d31a9c0c058e9934c378a10/image-6.jpg)

San Luis Valley Solar Data (09/12/2010) Bad Day [1] 6

Intermittent Wind Generation 7 7

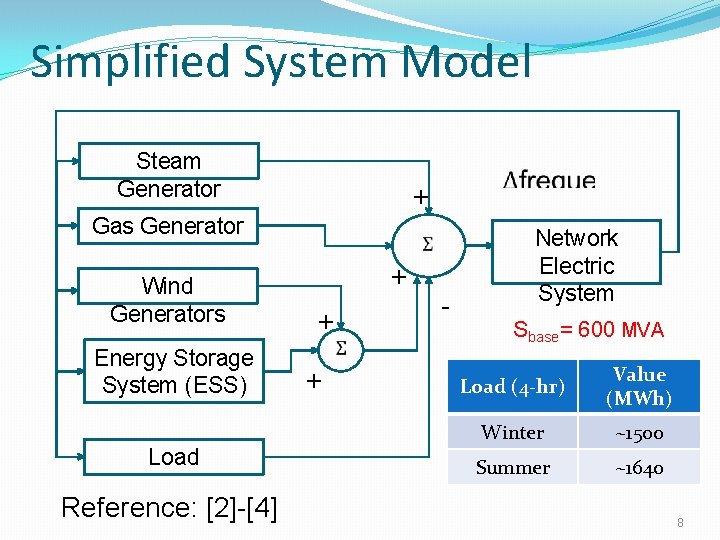

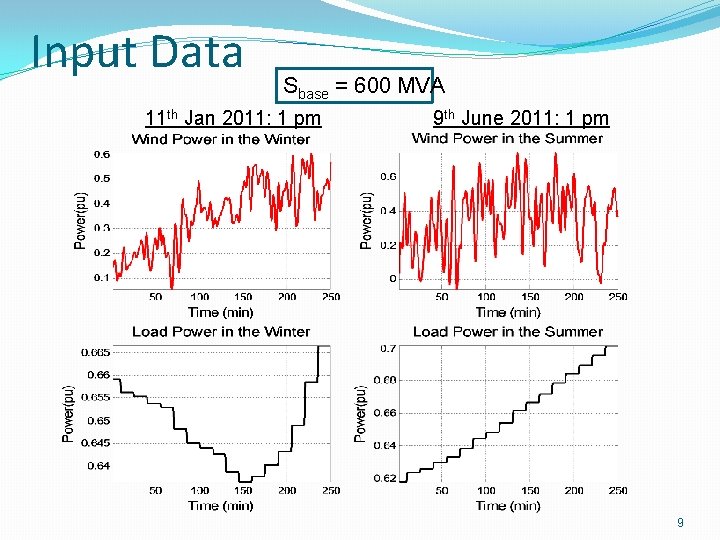

Simplified System Model Steam Generator + Gas Generator Wind Generators Energy Storage System (ESS) Load Reference: [2]-[4] + + + - Network Electric System Sbase= 600 MVA Load (4 -hr) Value (MWh) Winter ~1500 Summer ~1640 8

Input Data Sbase = 600 MVA 11 th Jan 2011: 1 pm 9 th June 2011: 1 pm 9

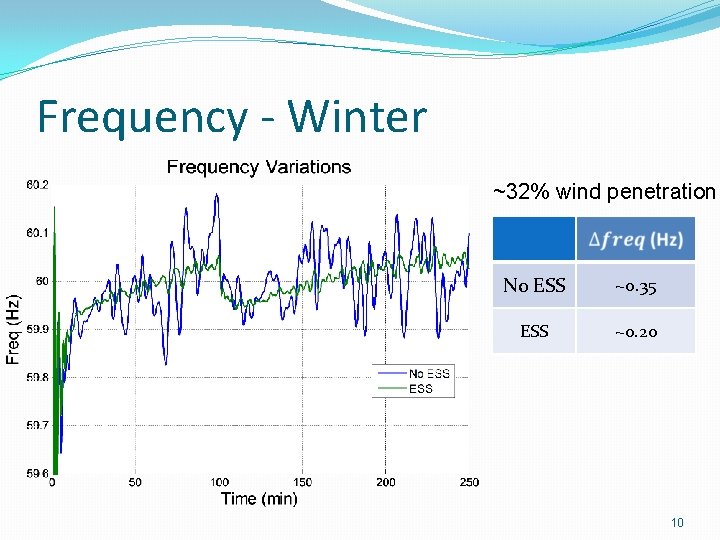

Frequency - Winter ~32% wind penetration No ESS ~0. 35 ESS ~0. 20 10

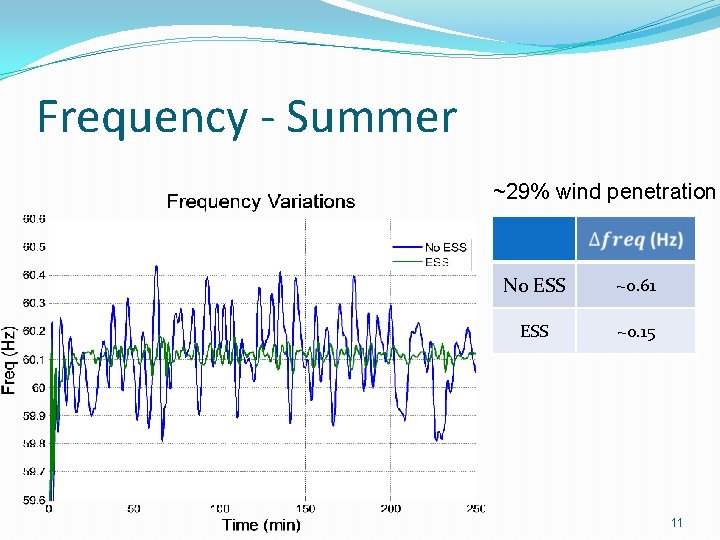

Frequency - Summer ~29% wind penetration No ESS ~0. 61 ESS ~0. 15 11

![Power Spectrum [1] Turbine upper limit small magnitude turbine acts as low-pass filter Short-term Power Spectrum [1] Turbine upper limit small magnitude turbine acts as low-pass filter Short-term](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/2e4c17cc6d31a9c0c058e9934c378a10/image-12.jpg)

Power Spectrum [1] Turbine upper limit small magnitude turbine acts as low-pass filter Short-term Storage Time Scale : ≈ 10 sec – 3 hrs Energy Storage 278 hour s 27. 8 hour s 2. 78 hour s 16. 7 min 100 sec 10 sec 2 sec 12

![References [1] J. Apt, “The spectrum of power from wind turbines”, Journal of Power References [1] J. Apt, “The spectrum of power from wind turbines”, Journal of Power](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/2e4c17cc6d31a9c0c058e9934c378a10/image-13.jpg)

References [1] J. Apt, “The spectrum of power from wind turbines”, Journal of Power Sources, v. 169, March 2007 [2] G. Lalor, A. Mullane, M. O’Malley, "Frequency Control and Wind Turbine Technologies“, IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, v. 20, no. 4, November 2005 [3] R. Doherty et al, “An Assessment of the Impact of Wind Generation on System Frequency Control", IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, v. 25, no. 11, February 2010 [4] P. Kundur, Power System Stability & Control, Mc. Graw-Hill, 1994 13

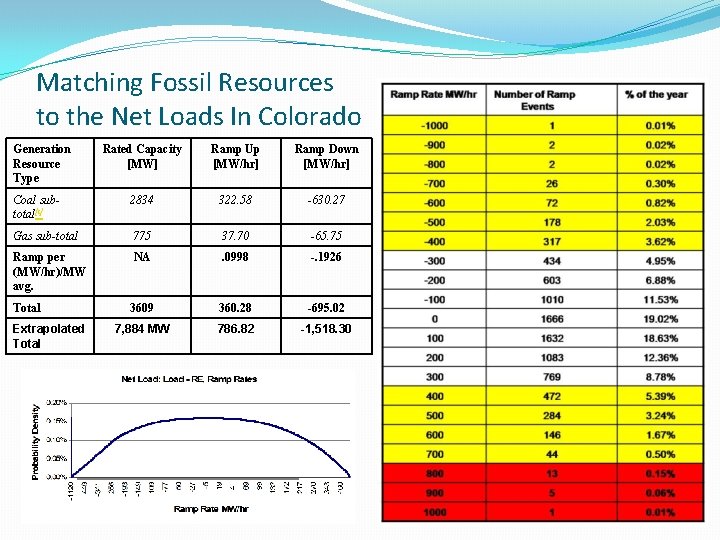

Matching Fossil Resources to the Net Loads In Colorado Generation Resource Type Rated Capacity [MW] Ramp Up [MW/hr] Ramp Down [MW/hr] Coal subtotal[i] 2834 322. 58 -630. 27 Gas sub-total 775 37. 70 -65. 75 Ramp per (MW/hr)/MW avg. NA . 0998 -. 1926 Total 3609 360. 28 -695. 02 7, 884 MW 786. 82 -1, 518. 30 Extrapolated Total

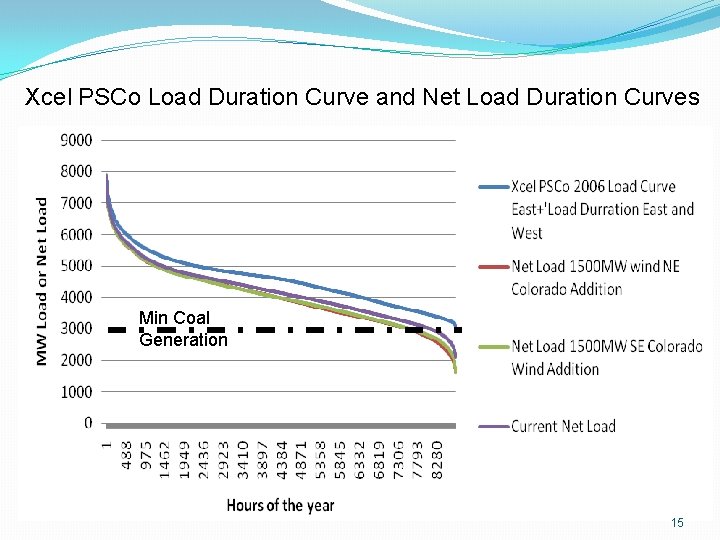

Xcel PSCo Load Duration Curve and Net Load Duration Curves Min Coal Generation 15

Case When Wind Energy Exceeds Capacity. Current Law Requires use of Wind Energy The wind energy may exceed the amount of gas fired energy that can be shut off and require the reduction of heat rate to coal fired plants This reduces electric power generation efficiency and increase emissions of SO 2, NOx and CO 2 for old plants It is expected to up to double the costs of maintenance. 16

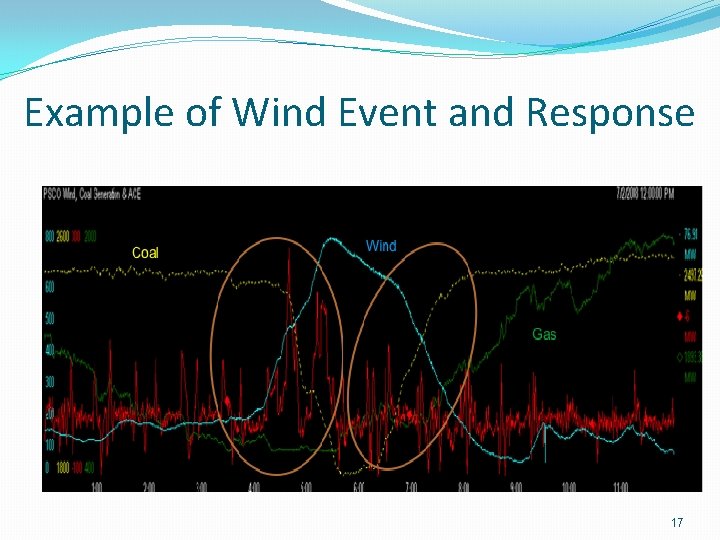

Example of Wind Event and Response 17

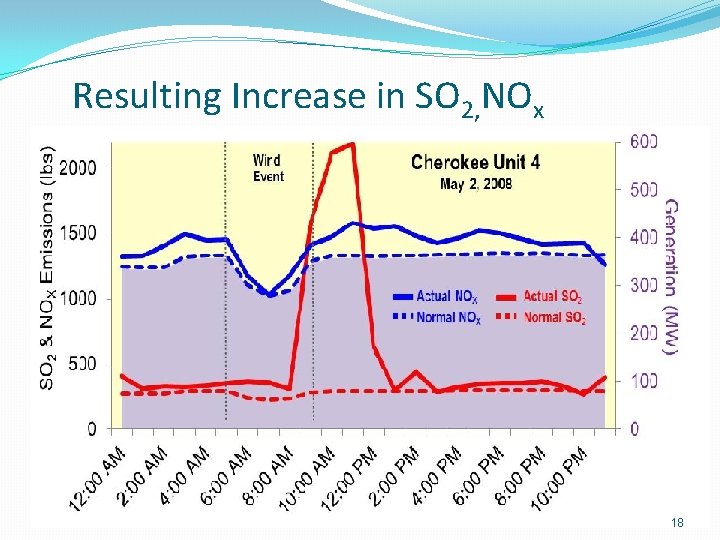

Resulting Increase in SO 2, NOx 18

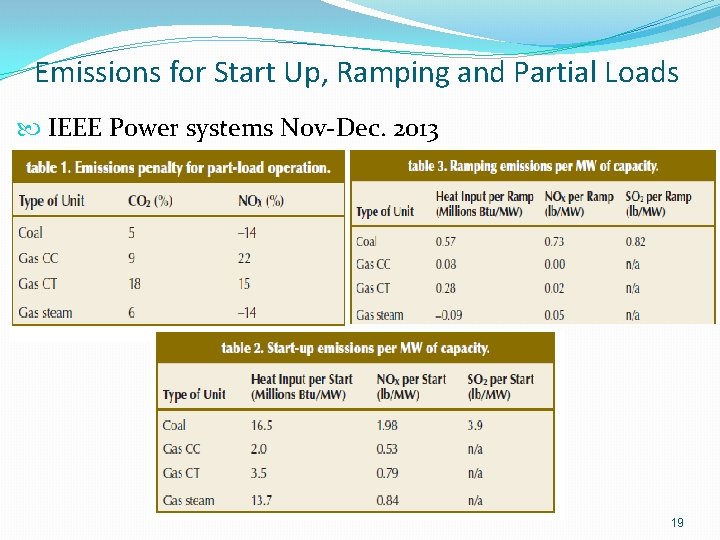

Emissions for Start Up, Ramping and Partial Loads IEEE Power systems Nov-Dec. 2013 19

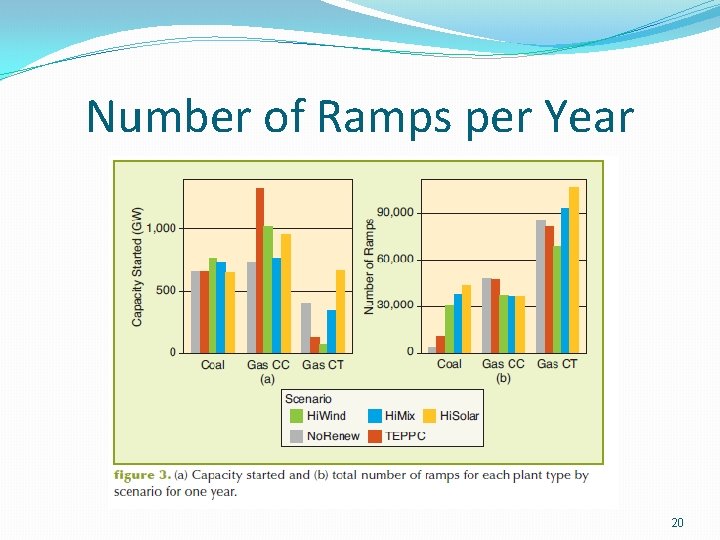

Number of Ramps per Year 20

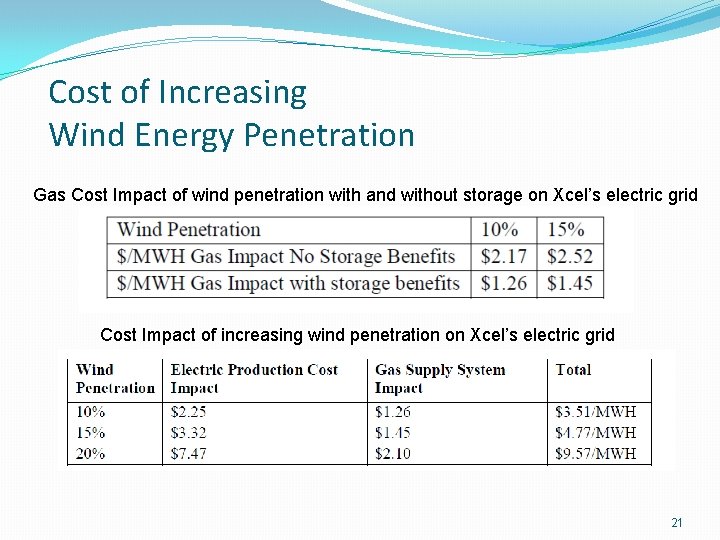

Cost of Increasing Wind Energy Penetration Gas Cost Impact of wind penetration with and without storage on Xcel’s electric grid Cost Impact of increasing wind penetration on Xcel’s electric grid 21

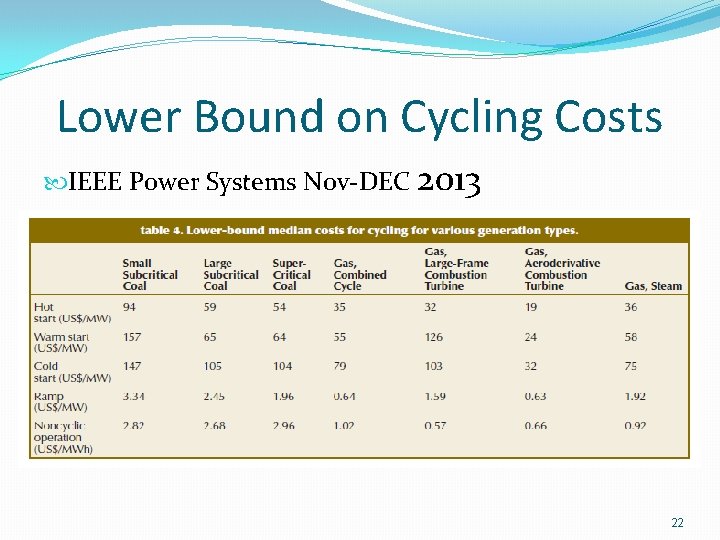

Lower Bound on Cycling Costs IEEE Power Systems Nov-DEC 2013 22

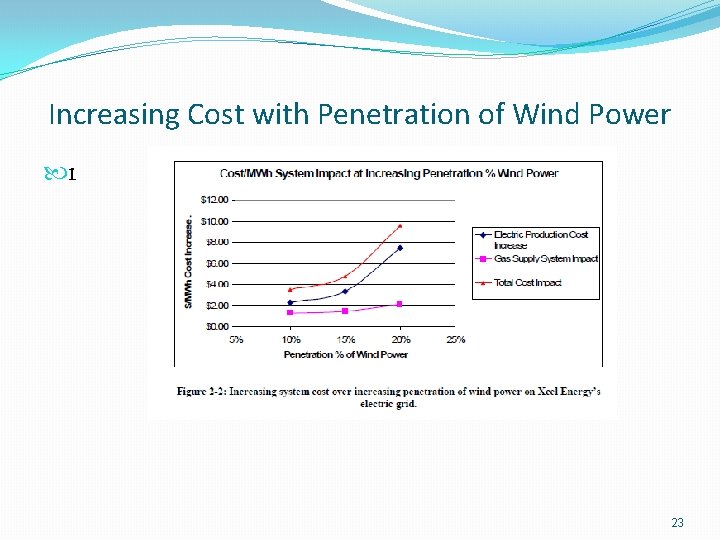

Increasing Cost with Penetration of Wind Power 1 23

Approaches to Solving the Variability Issues. At low penetration grid spinning reserves. Gas fired generators Storage 1. 2. 3. a. b. 4. 5. Batteries, super capacitors, fly wheels Pumped Hydroelectric systems, CAES Demand Response Biomass, geothermal 24

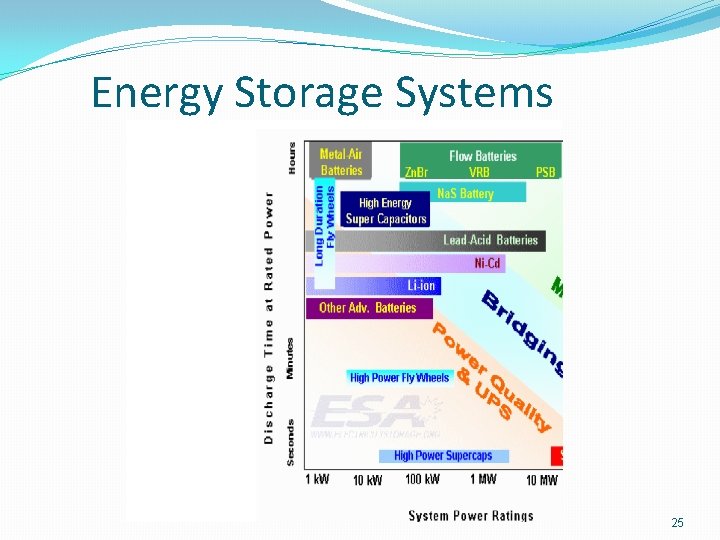

Energy Storage Systems 25

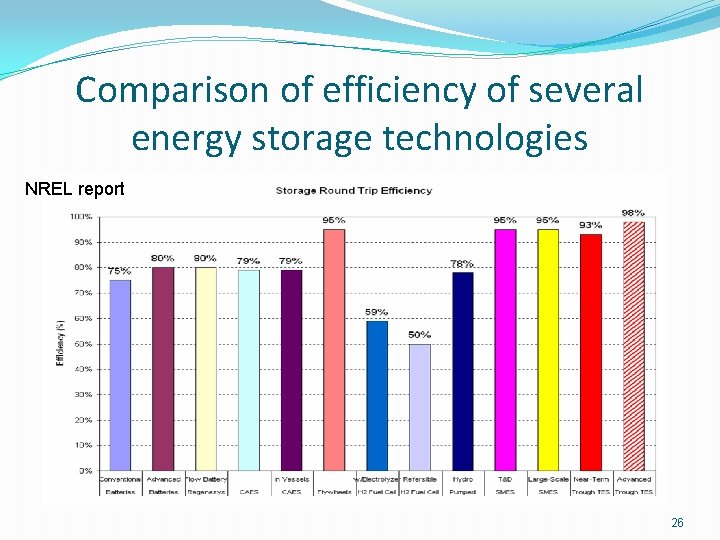

Comparison of efficiency of several energy storage technologies NREL report 26

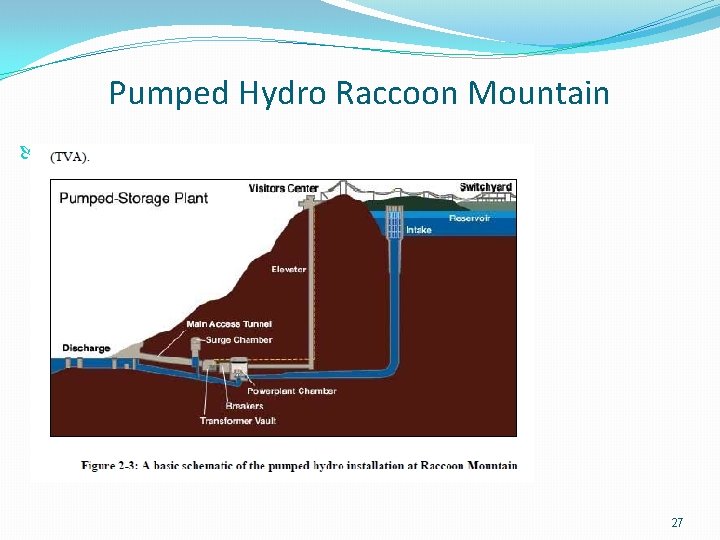

Pumped Hydro Raccoon Mountain 1 27

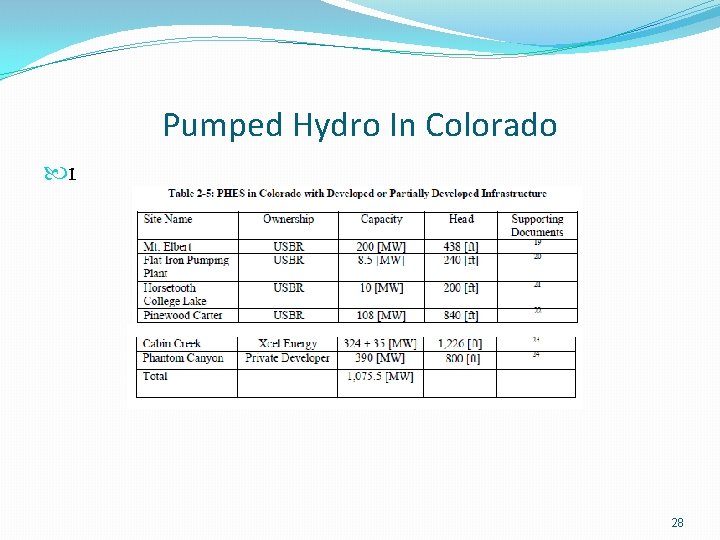

Pumped Hydro In Colorado 1 28

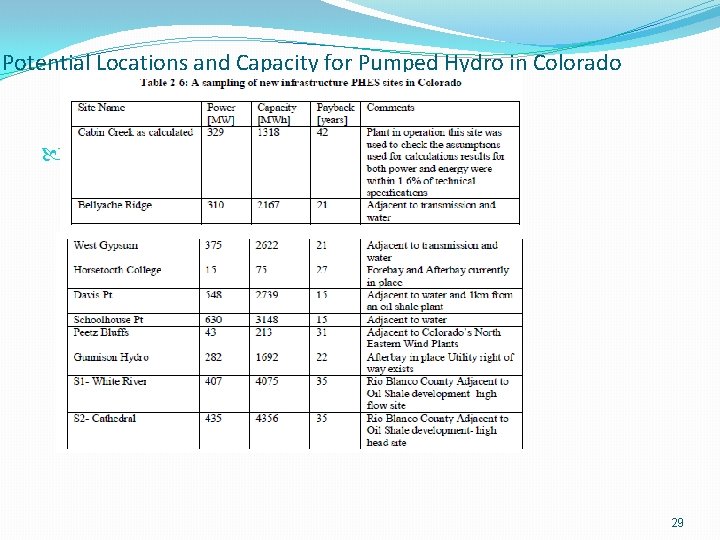

Potential Locations and Capacity for Pumped Hydro in Colorado 1 29

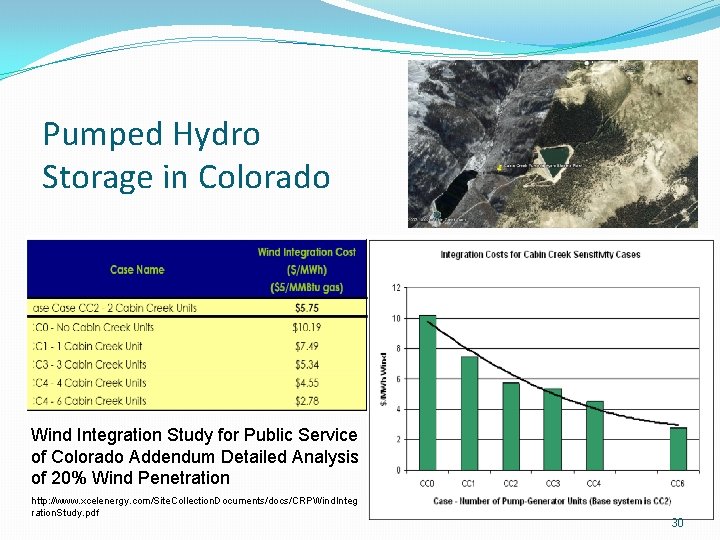

Pumped Hydro Storage in Colorado Wind Integration Study for Public Service of Colorado Addendum Detailed Analysis of 20% Wind Penetration http: //www. xcelenergy. com/Site. Collection. Documents/docs/CRPWind. Integ ration. Study. pdf 30

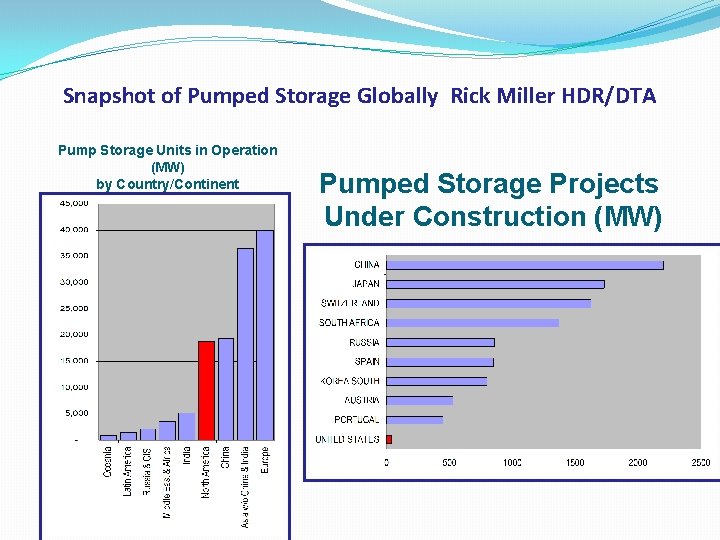

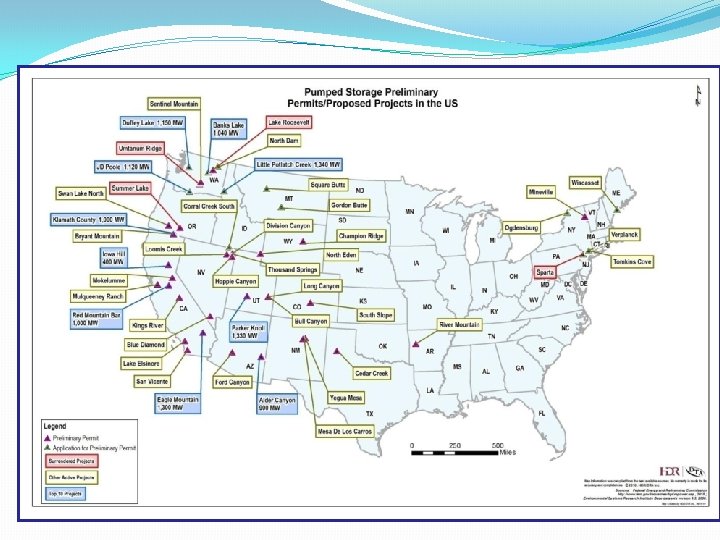

Snapshot of Pumped Storage Globally Rick Miller HDR/DTA Pump Storage Units in Operation (MW) by Country/Continent Pumped Storage Projects Under Construction (MW)

ECEN 2060 Lecture 37 December 2, 2013 Compressed Air Energy Storage CAES 33

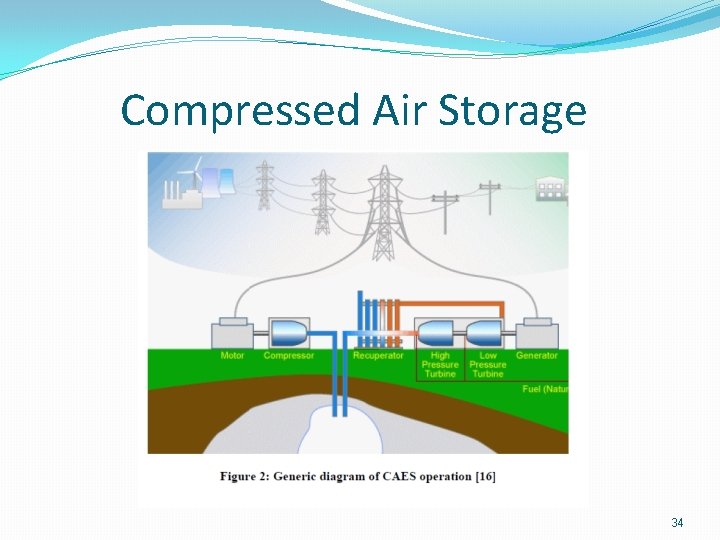

Compressed Air Storage 34

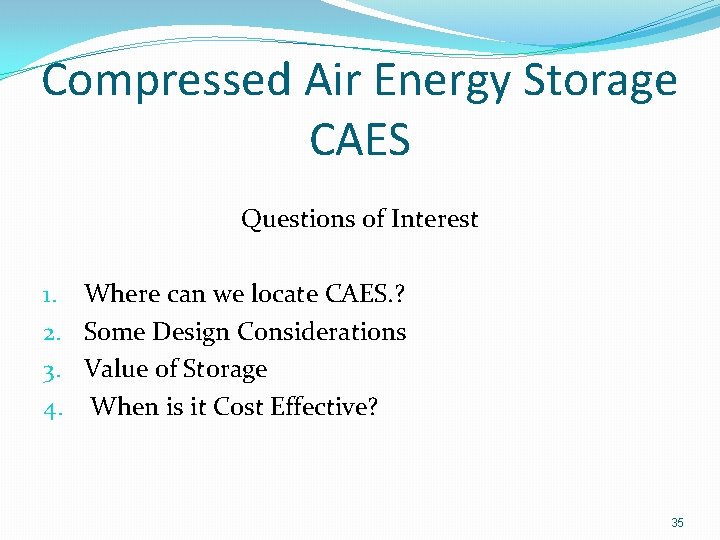

Compressed Air Energy Storage CAES Questions of Interest 1. Where can we locate CAES. ? 2. Some Design Considerations 3. Value of Storage 4. When is it Cost Effective? 35

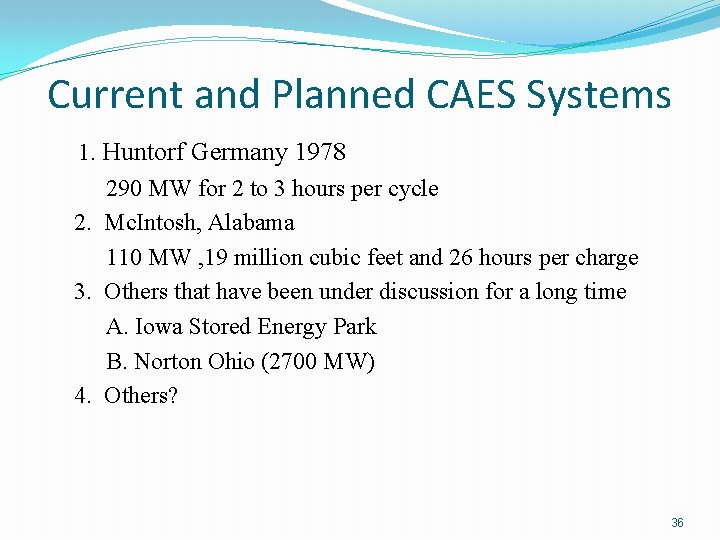

Current and Planned CAES Systems 1. Huntorf Germany 1978 290 MW for 2 to 3 hours per cycle 2. Mc. Intosh, Alabama 110 MW , 19 million cubic feet and 26 hours per charge 3. Others that have been under discussion for a long time A. Iowa Stored Energy Park B. Norton Ohio (2700 MW) 4. Others? 36

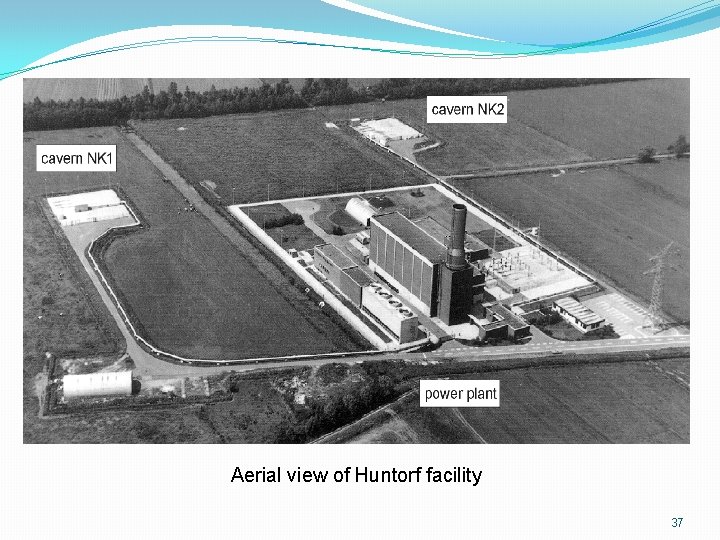

Aerial view of Huntorf facility 37

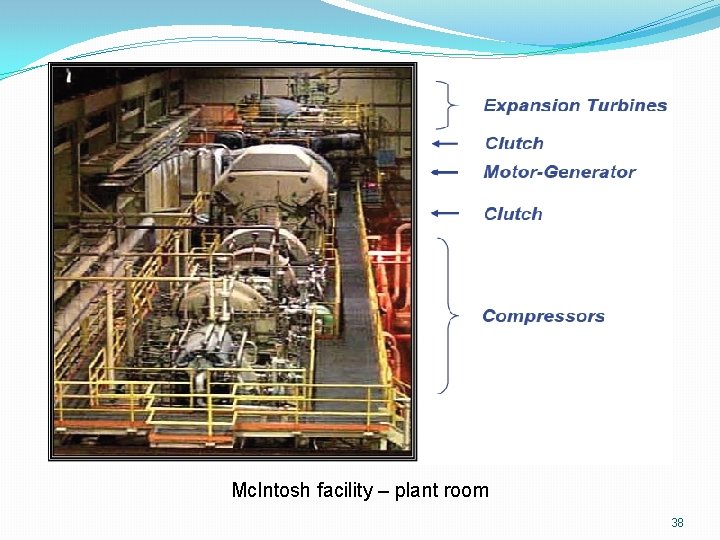

Mc. Intosh facility – plant room 38

CAES Characteristics 1. It is a hybrid system with energy stored in compressed air and need heat from another source as well. 2. Require 0. 7 to 0. 8 k. Wh off peak electrical energy and 4100 to 4500 Btu (1. 2 -1. 3 k. Wh) of natural gas for 1 k. Wh of dispatchable electricity 3. This compares with ~ 11, 000 Btu/k. Wh for conventional gas fired turbine generators. 4. Efficiency of electrical energy out to electrical plus natural gas energy in ~ 50% 39

CAES Characteristics Another way to calculate efficiency is comparing to the normal low efficiency of natural gas turbines with heat rate of 11000 Btu/k. Wh yielding 0. 39 k. Wh of electricity and adding 0. 75 k. Wh off peak electricity to get 1. 14 k. Wh’s to get 1 k. Wh of dispatchable electricity This gives an efficiency of 88% There are two types of CAES systems o Underground CAES o Above ground CAES 40

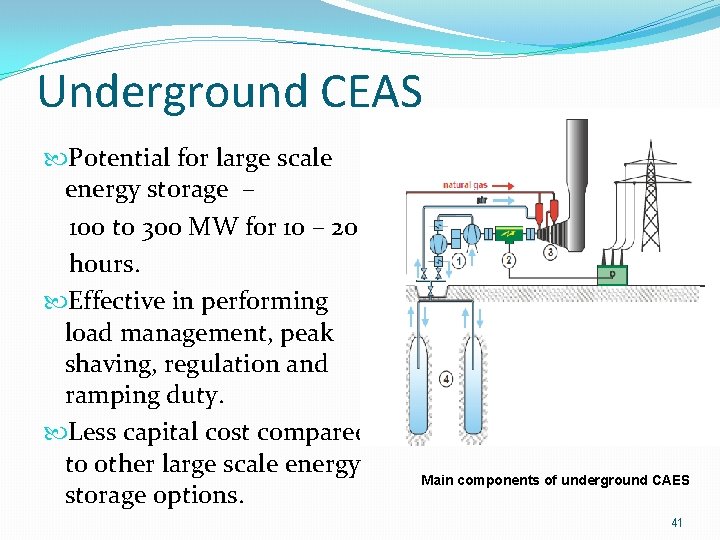

Underground CEAS Potential for large scale energy storage – 100 to 300 MW for 10 – 20 hours. Effective in performing load management, peak shaving, regulation and ramping duty. Less capital cost compared to other large scale energy storage options. Main components of underground CAES 41

Challenges associated with Underground CAES Identification of suitable site for setting up a underground facility. Optimizing the compression process to reduce the compression work required. Thermal management – efficiently extracting, storing and reusing the available heat of compression, thus improving the efficiency of the system. Understanding the effect of cyclic loading and unloading on the structural integrity of the underground cavern. 42

Deep CAES Deep compressed air energy storage is an underground CAES facility where the cavern is formed at depths of >4000 ft. as against 1000 -2000 ft. in case of conventional facilities. The main advantage of going deep are, o Maximum permissible operating pressure of a cavern increases with depth. - A good approximation will be 0. 75 to 1. 13 psi/ft. based on the local geology. o Hence going deep helps store air at higher pressures in much smaller cavern volume, hence higher energy density. The possibility of setting up a deep compressed air energy storage facility in Eastern Colorado is being currently investigated by Energy Storage Research group at CU, Boulder. 43

Challenges associated with Deep CAES brings in additional challenges, which are Utilizing the high pressure compressed air effectively. Most of the off-the-self gas turbines operate in the range of 70100 bars, hence it is necessary to design the system such that high pressures can be utilized. Understanding the effect of high pressure & temperature on the cavern structure. Identifying suitable equipment's / material to operate at high pressure. Potential for leakage through faults. 44

Criteria for Site Selection 1. Tight Cavern 2. Adequate natural gas 3. Ability to withstand 600 to 1200 psi for conventional & 2000 – 5000 psi for deep CAES. 4. Proximity to Wind or Load to minimize transmission line losses. 5. Appropriate geology 6. A report by Cohn et al. 1991 “Applications of air saturation to integrated coal gasification/CAES power plants. ASME 91 -JPGC-GT-2 says that this can be found in 85% of the US. 45

Possible Geologies 1. Abandoned Natural Gas fields. 2. Old Mines 3. Dome Aquifers 4. Porous Sandstone 4. Salt Domes 5. Bedded Salt 46

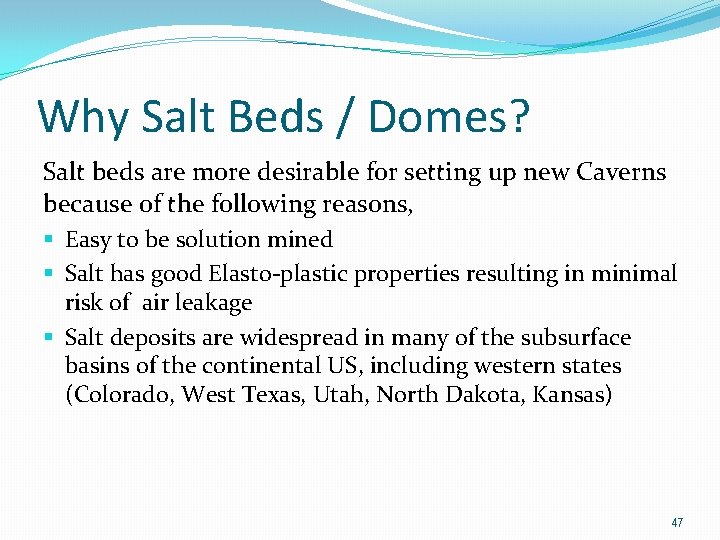

Why Salt Beds / Domes? Salt beds are more desirable for setting up new Caverns because of the following reasons, § Easy to be solution mined § Salt has good Elasto-plastic properties resulting in minimal risk of air leakage § Salt deposits are widespread in many of the subsurface basins of the continental US, including western states (Colorado, West Texas, Utah, North Dakota, Kansas) 47

Salt Formations 48

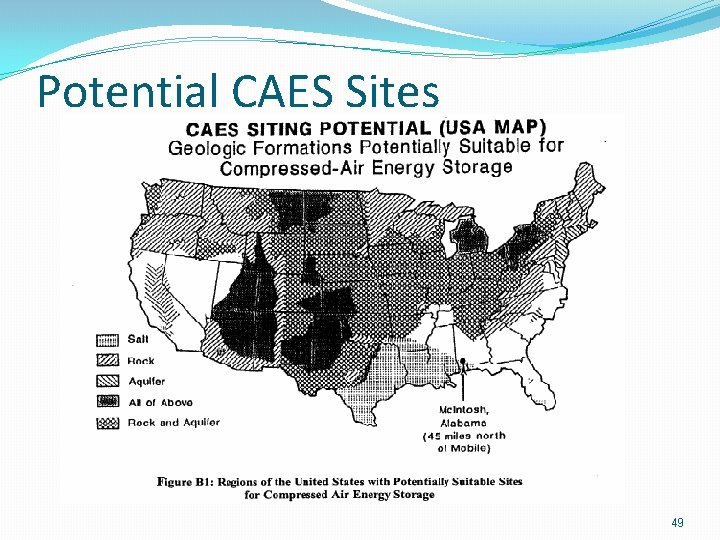

Potential CAES Sites 49

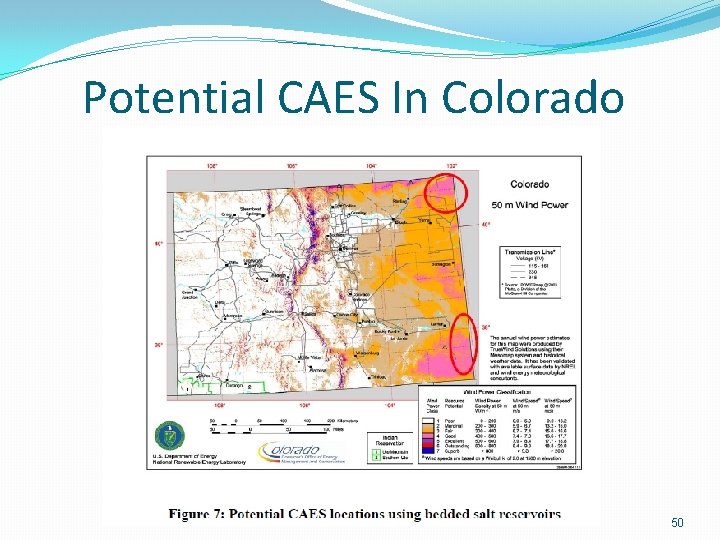

Potential CAES In Colorado 50

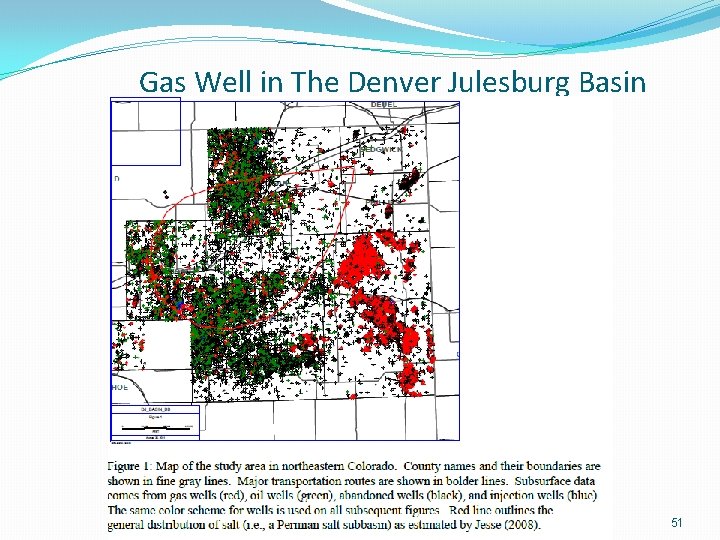

Gas Well in The Denver Julesburg Basin 51

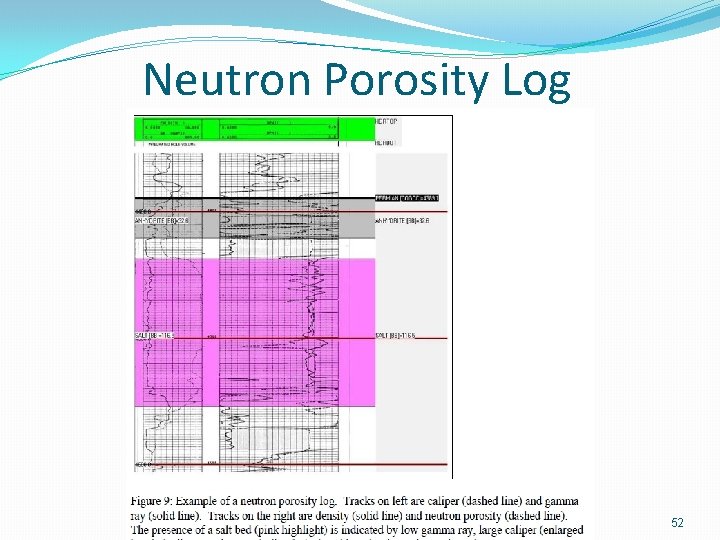

Neutron Porosity Log 52

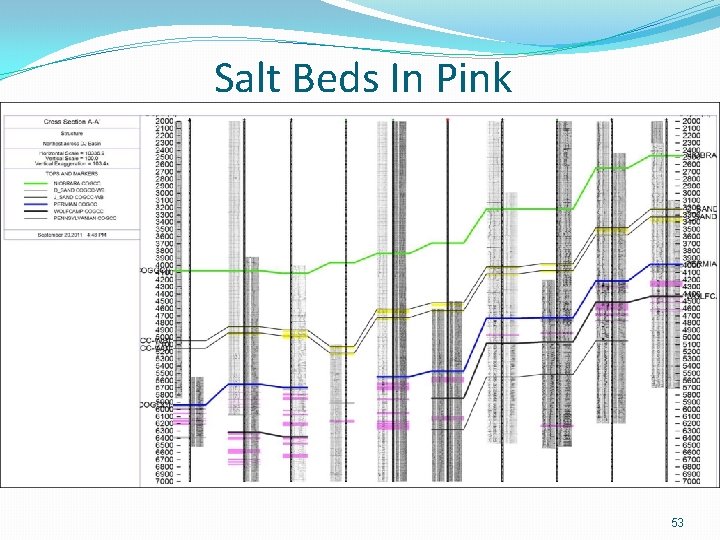

Salt Beds In Pink 53

Salt Beds In Eastern Colorado 1. Salt beds from 4100 ft to 6, 800 ft. 2. Thickness from 3 to 292 ft. 3. Required Operating pressures in the range of 4000 to 7000 psi. 6 At about 6, 000 psi we need about 14, 400 cubic meters per gigawatt hour energy storage or a cavern of about 30 x 22 meters 54

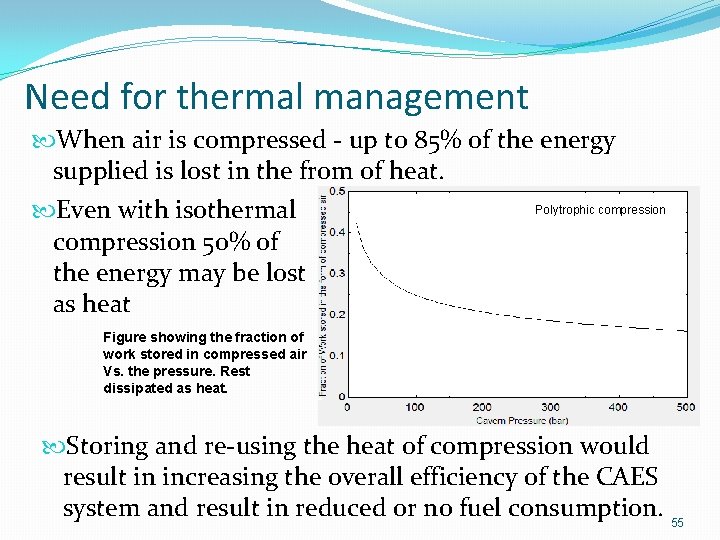

Need for thermal management When air is compressed - up to 85% of the energy supplied is lost in the from of heat. Even with isothermal compression 50% of the energy may be lost as heat Polytrophic compression Figure showing the fraction of work stored in compressed air Vs. the pressure. Rest dissipated as heat. Storing and re-using the heat of compression would result in increasing the overall efficiency of the CAES system and result in reduced or no fuel consumption. 55

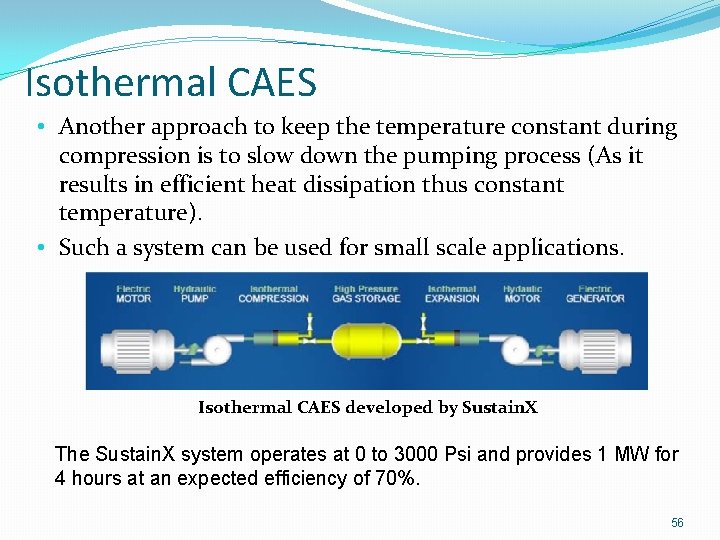

Isothermal CAES • Another approach to keep the temperature constant during compression is to slow down the pumping process (As it results in efficient heat dissipation thus constant temperature). • Such a system can be used for small scale applications. Isothermal CAES developed by Sustain. X The Sustain. X system operates at 0 to 3000 Psi and provides 1 MW for 4 hours at an expected efficiency of 70%. 56

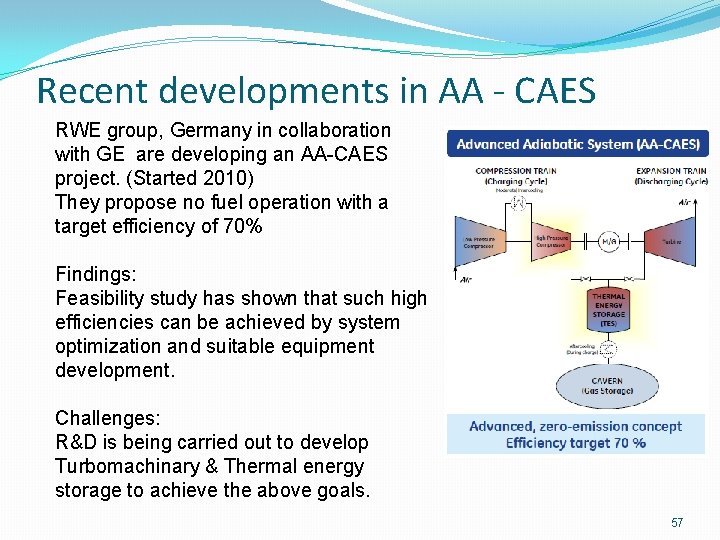

Recent developments in AA - CAES RWE group, Germany in collaboration with GE are developing an AA-CAES project. (Started 2010) They propose no fuel operation with a target efficiency of 70% Findings: Feasibility study has shown that such high efficiencies can be achieved by system optimization and suitable equipment development. Challenges: R&D is being carried out to develop Turbomachinary & Thermal energy storage to achieve the above goals. 57

Lecture 38 ECEN 2060 December 4, 2013 58

Storing & Re-use of compression heat Heat of compression can be stored in two ways o With the help of thermal energy storage facility o By storing the heat in compressed air itself There are two options for utilizing the stored energy o Using the stored heat + Fuel for preheating the air o Only utilizing the stored heat (No Fuel) also called as Advanced Adiabatic CAES (AA-CAES). 59

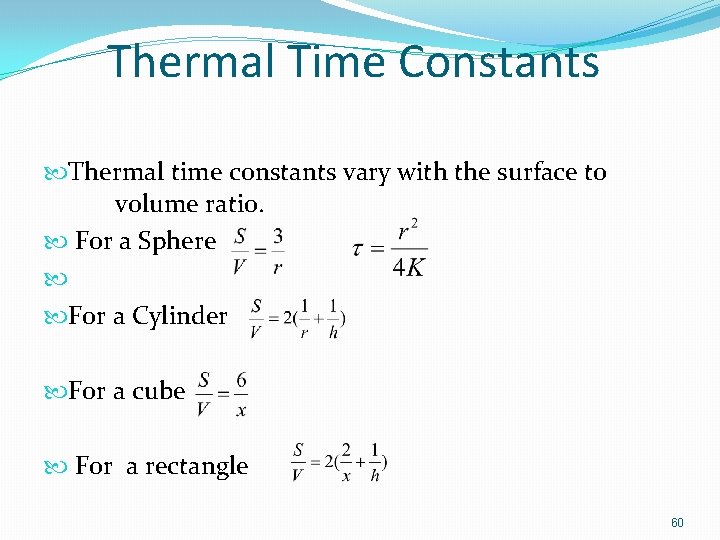

Thermal Time Constants Thermal time constants vary with the surface to volume ratio. For a Sphere For a Cylinder For a cube For a rectangle 60

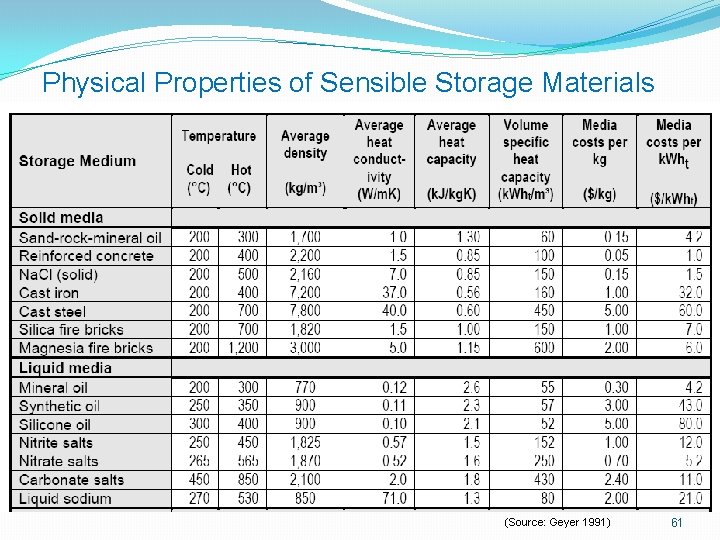

Physical Properties of Sensible Storage Materials (Source: Geyer 1991) 61

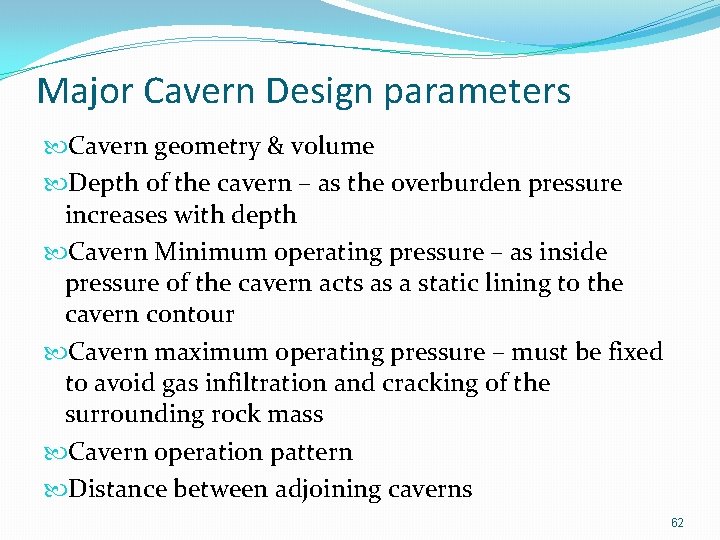

Major Cavern Design parameters Cavern geometry & volume Depth of the cavern – as the overburden pressure increases with depth Cavern Minimum operating pressure – as inside pressure of the cavern acts as a static lining to the cavern contour Cavern maximum operating pressure – must be fixed to avoid gas infiltration and cracking of the surrounding rock mass Cavern operation pattern Distance between adjoining caverns 62

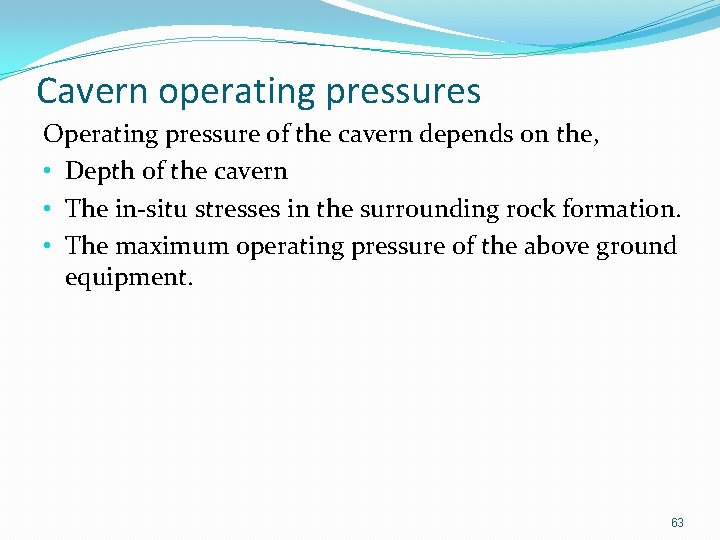

Cavern operating pressures Operating pressure of the cavern depends on the, • Depth of the cavern • The in-situ stresses in the surrounding rock formation. • The maximum operating pressure of the above ground equipment. 63

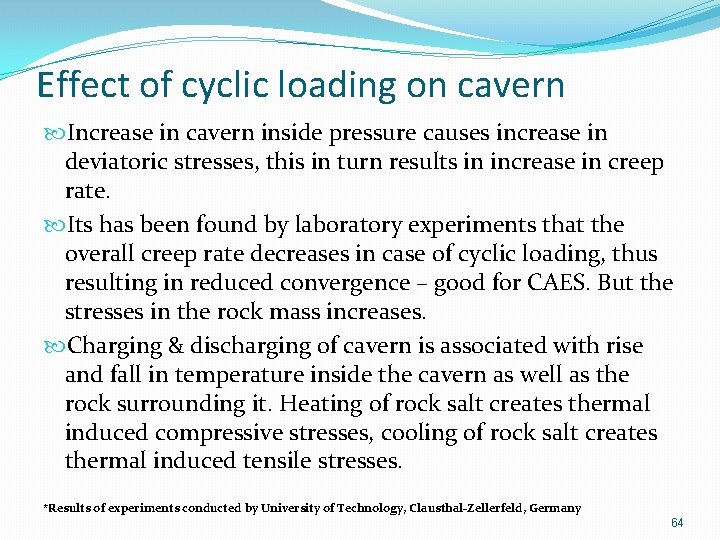

Effect of cyclic loading on cavern Increase in cavern inside pressure causes increase in deviatoric stresses, this in turn results in increase in creep rate. Its has been found by laboratory experiments that the overall creep rate decreases in case of cyclic loading, thus resulting in reduced convergence – good for CAES. But the stresses in the rock mass increases. Charging & discharging of cavern is associated with rise and fall in temperature inside the cavern as well as the rock surrounding it. Heating of rock salt creates thermal induced compressive stresses, cooling of rock salt creates thermal induced tensile stresses. *Results of experiments conducted by University of Technology, Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany 64

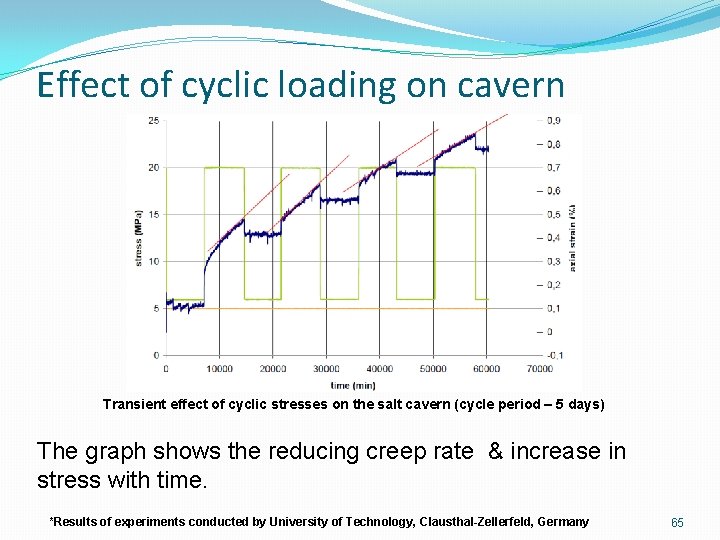

Effect of cyclic loading on cavern Transient effect of cyclic stresses on the salt cavern (cycle period – 5 days) The graph shows the reducing creep rate & increase in stress with time. *Results of experiments conducted by University of Technology, Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany 65

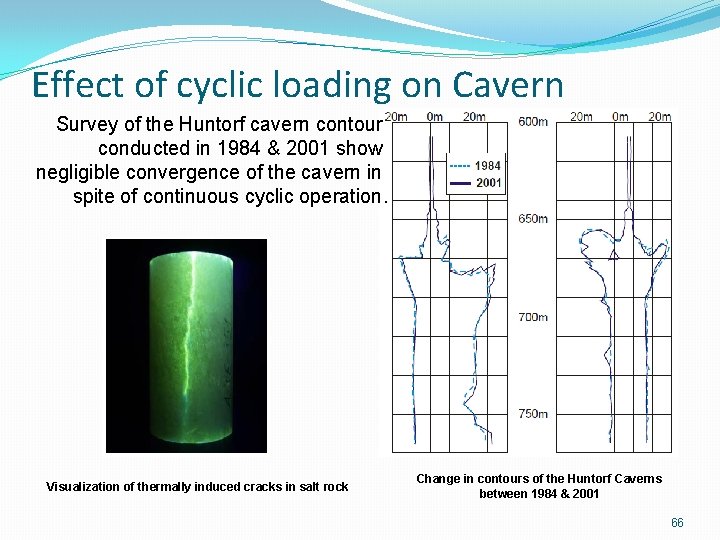

Effect of cyclic loading on Cavern Survey of the Huntorf cavern contour conducted in 1984 & 2001 show negligible convergence of the cavern in spite of continuous cyclic operation. Visualization of thermally induced cracks in salt rock Change in contours of the Huntorf Caverns between 1984 & 2001 66

Effect of cyclic loading on Cavern Further work needed: • Understanding thermo-mechanical effects (convergence & creep) on surround rock at high pressures & temperature. • Effect of different charging and discharging periods / operation patterns • Effect of having a deep cavern at atmospheric pressure for maintenance work. 67

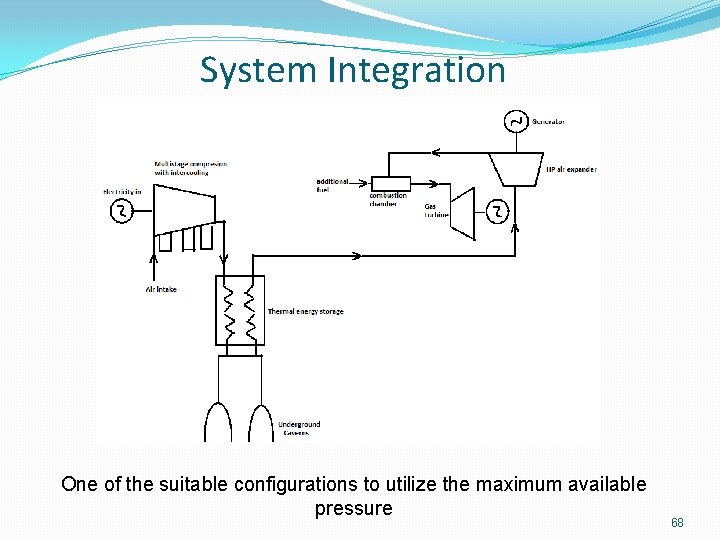

System Integration One of the suitable configurations to utilize the maximum available pressure 68

Economics 1. Costs A. A little more than conventional gas fired generators at $4 oo to $500/k. W B. CAES estimates at $600 to $700/k. W (Note these numbers could be low depending on the site etc) C. Low Operating Costs 2. Value A. Smooth out wind fluctuations B. Match to transmission line limits. C. Match to loads increasing capacity factor. 69

Economics 2. Value D. Absorb Energy when the wind power exceeds transmission or load. This is in contrast to gas fired generators E. Arbitrage , buy wind or other energy low and sell high. F. Ancillary services , frequency control, black start etc. G. Reduced natural gas consumption by approximately two thirds. 70

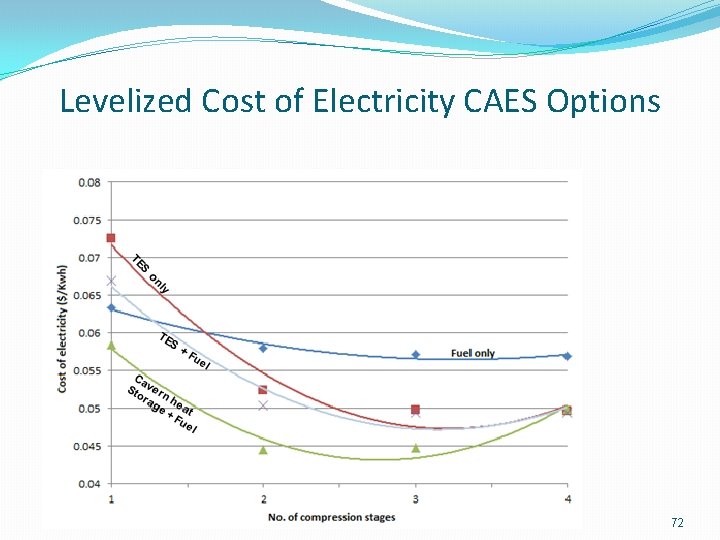

Economics Factors effecting CAES capital cost o CAES site selection Depth of Cavern Local geology Proximity to transmission network Availability of Natural gas o Presence of Thermal energy storage, TES. Factors effecting CAES Operating cost o Cost of off peak energy and/or Wind energy generation cost. o Natural gas requirement based on TES availability 71

Levelized Cost of Electricity CAES Options 72

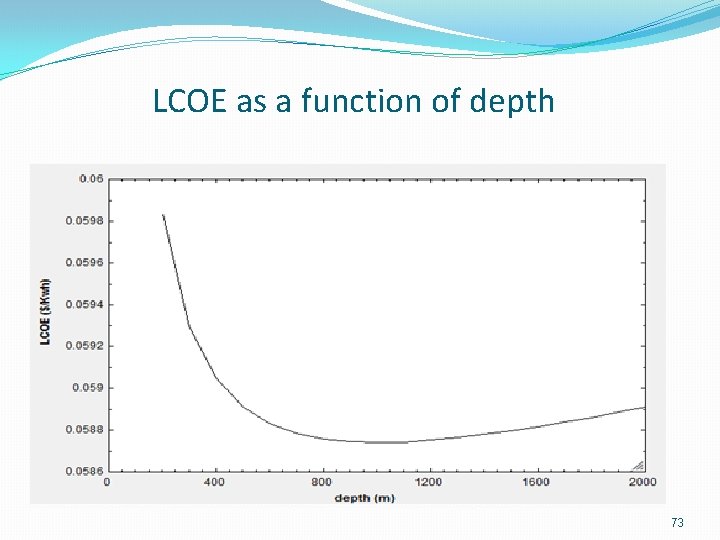

LCOE as a function of depth 73

Batteries 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Lead Acid Metal Hydride Li –Ion Na S Vanadium Redox –Flow 74

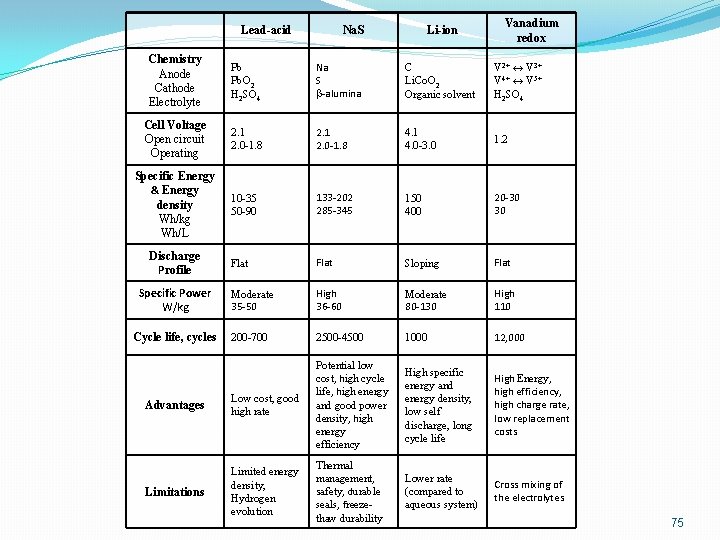

Lead-acid Na. S Li-ion Vanadium redox Chemistry Anode Cathode Electrolyte Pb Pb. O 2 H 2 SO 4 Na S b-alumina C Li. Co. O 2 Organic solvent V 2+ ↔ V 3+ V 4+ ↔ V 5+ H 2 SO 4 Cell Voltage Open circuit Operating 2. 1 2. 0 -1. 8 4. 1 4. 0 -3. 0 1. 2 Specific Energy & Energy density Wh/kg Wh/L 10 -35 50 -90 133 -202 285 -345 150 400 20 -30 30 Flat Sloping Flat Specific Power W/kg Moderate 35 -50 High 36 -60 Moderate 80 -130 High 110 Cycle life, cycles 200 -700 2500 -4500 1000 12, 000 Advantages Low cost, good high rate Potential low cost, high cycle life, high energy and good power density, high energy efficiency High specific energy and energy density, low self discharge, long cycle life High Energy, high efficiency, high charge rate, low replacement costs Limitations Limited energy density, Hydrogen evolution Thermal management, safety, durable seals, freezethaw durability Lower rate (compared to aqueous system) Cross mixing of the electrolytes Discharge Profile 75

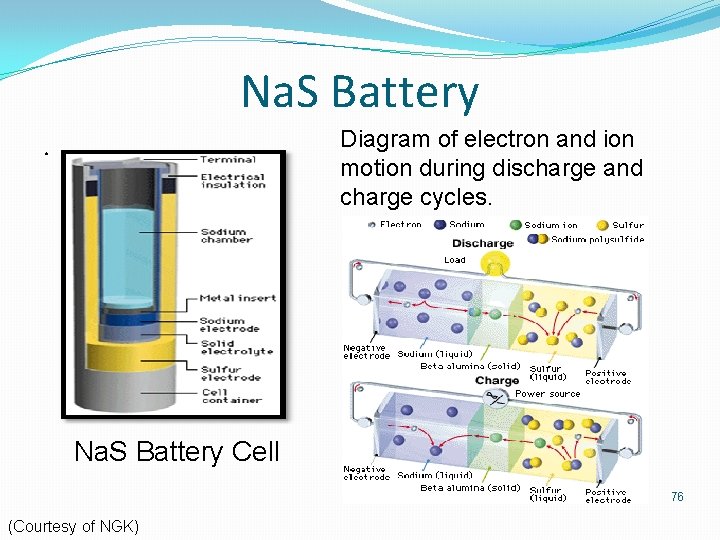

Na. S Battery Diagram of electron and ion motion during discharge and charge cycles. . Na. S Battery Cell 76 (Courtesy of NGK)

Na. S Batteries Twenty Na. S Batteries installed in four enclosures 77

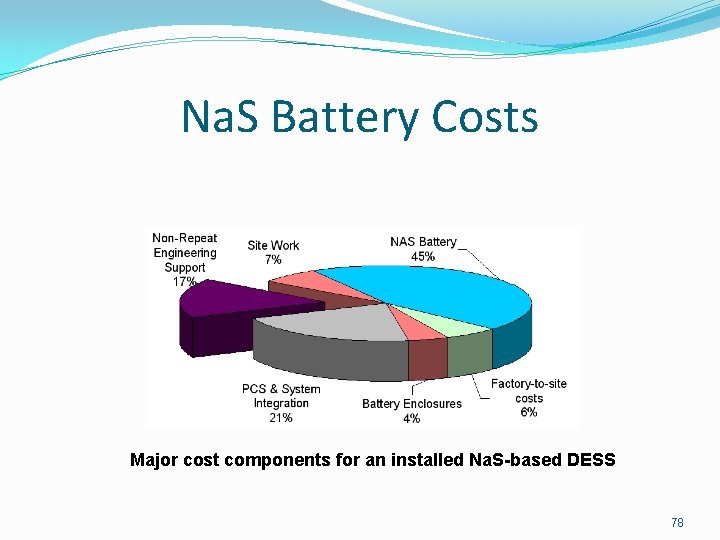

Na. S Battery Costs Major cost components for an installed Na. S-based DESS 78

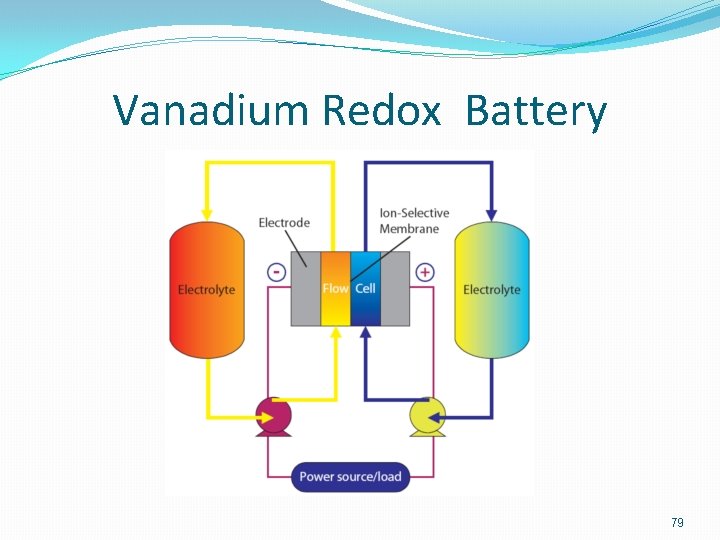

Vanadium Redox Battery 79

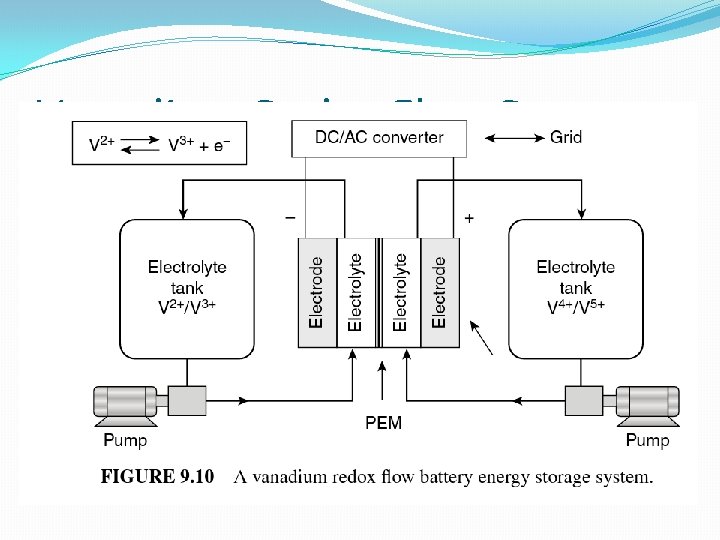

Vanadium Redox Flow Battery

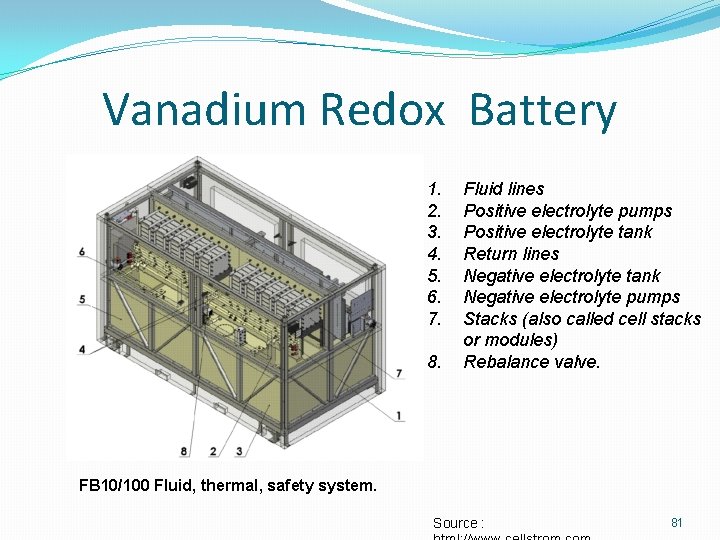

Vanadium Redox Battery 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Fluid lines Positive electrolyte pumps Positive electrolyte tank Return lines Negative electrolyte tank Negative electrolyte pumps Stacks (also called cell stacks or modules) Rebalance valve. FB 10/100 Fluid, thermal, safety system. Source : 81

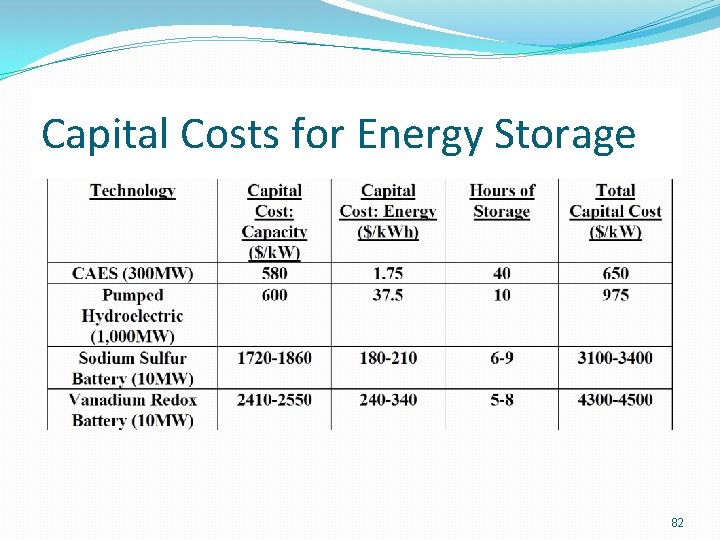

Capital Costs for Energy Storage 82

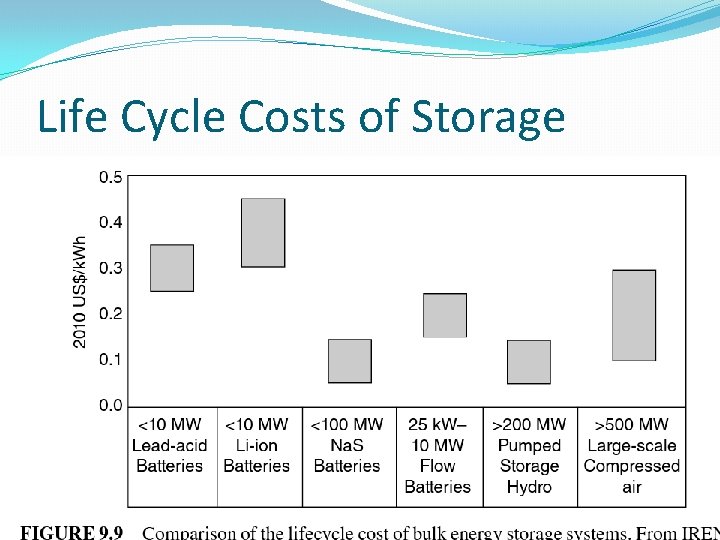

Life Cycle Costs of Storage

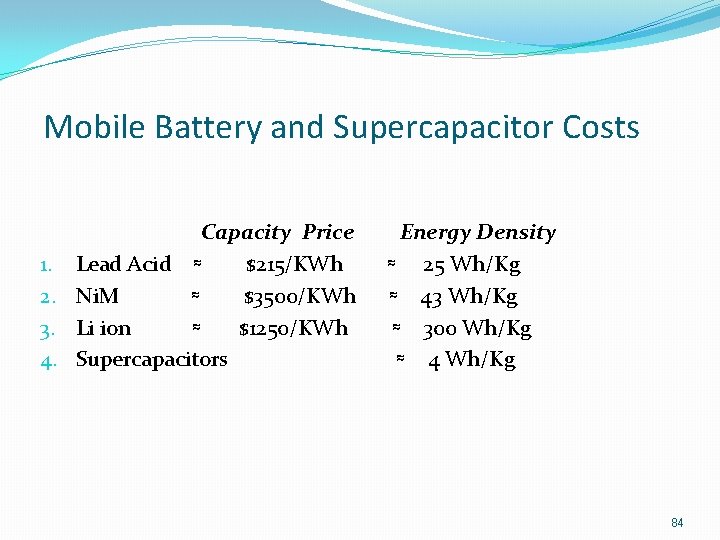

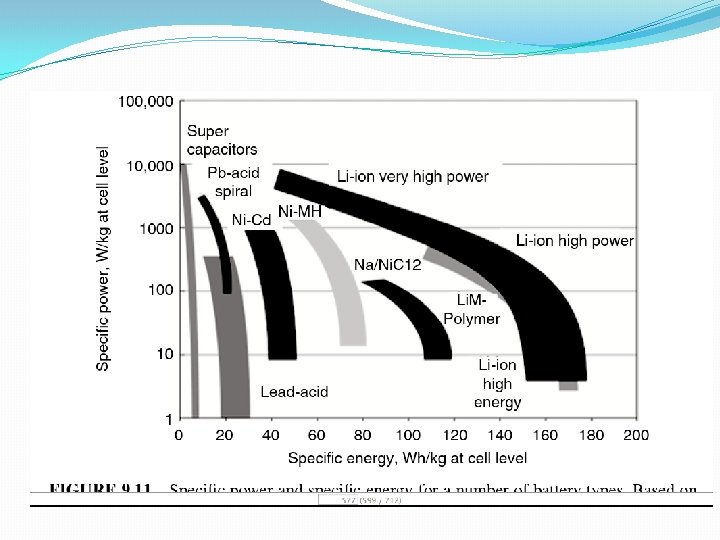

Mobile Battery and Supercapacitor Costs Capacity Price 1. Lead Acid ≈ $215/KWh 2. Ni. M ≈ $3500/KWh 3. Li ion ≈ $1250/KWh 4. Supercapacitors Energy Density ≈ 25 Wh/Kg ≈ 43 Wh/Kg ≈ 300 Wh/Kg ≈ 4 Wh/Kg 84

Energy Density for Batteries

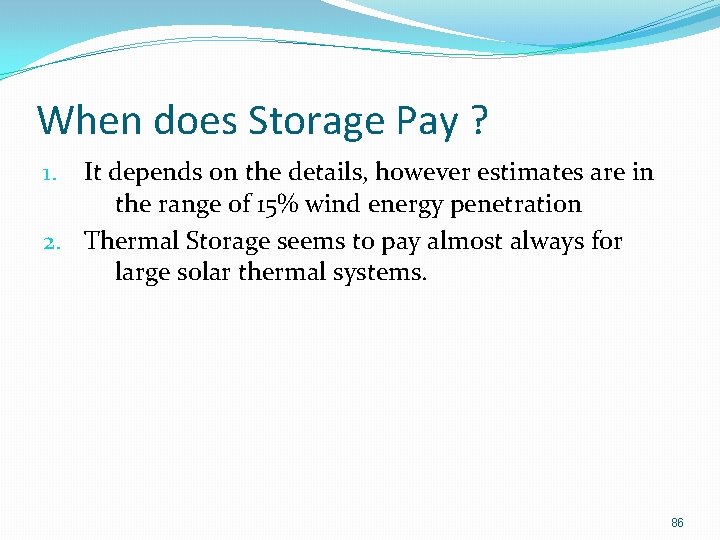

When does Storage Pay ? It depends on the details, however estimates are in the range of 15% wind energy penetration 2. Thermal Storage seems to pay almost always for large solar thermal systems. 1. 86

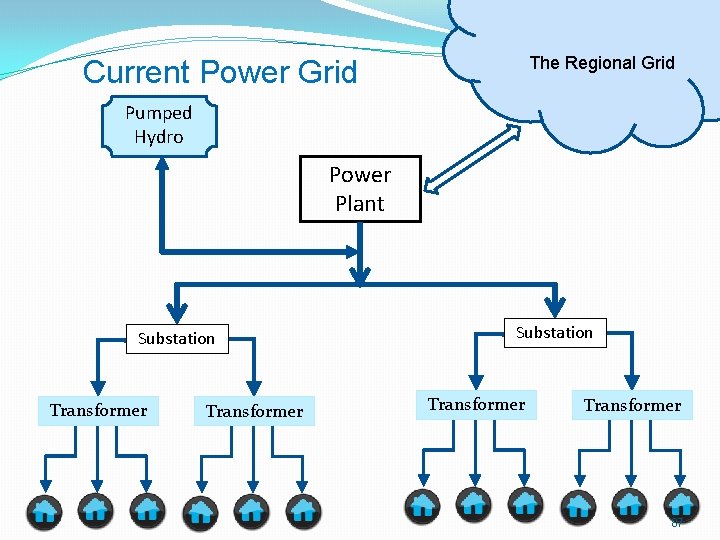

Current Power Grid The Regional Grid Pumped Hydro Power Plant Substation Transformer 87

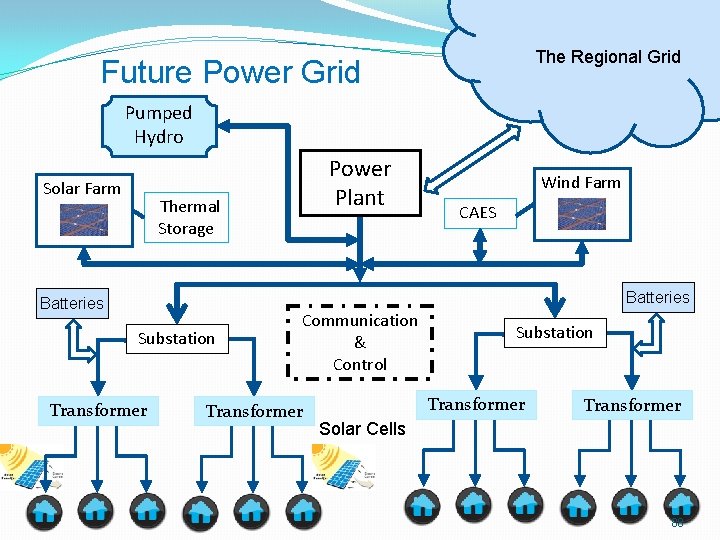

The Regional Grid Future Power Grid Pumped Hydro Solar Farm Power Plant Thermal Storage Wind Farm CAES Batteries Substation Transformer Communication & Control Transformer Substation Transformer Solar Cells 88

- Slides: 88