ENDOSCOPIC FEATURES OF COLORECTAL POLYPS Colorectal cancer is

- Slides: 61

ENDOSCOPIC FEATURES OF COLORECTAL POLYPS

• Colorectal cancer is defined clinically as invasion of dysplastic cells into the submucosa. Lesions with submucosal invasion but without invasion into the muscularis propria are generally called malignant polyps (includes polypoid and flat or depressed lesions). In the TMN classification such lesions are p. T 1.

• Without submucosal invasion, the term cancer should be avoided. Although some pathologists consider cancer in the lamina propria to be “invasive, ” dysplastic changes in the lamina propria alone does not meet the clinically accepted definition of colorectal cancer. • A patient management problem arises when terms such as intramucosal adenocarcinoma are used to describe changes in the lamina propria of the mucosa, because any use of the word adenocarcinoma can be easily misinterpreted by clinicians and patients as equivalent to cancer, and thereby lead to incorrect decisions.

• Based on our experience and discussion with Japanese experts, it is more common in the United States than in Japan for clinicians to incorrectly believe that colorectal neoplasia confined to the lamina propria and described as intramucosal adenocarcinoma has the potential for distant metastasis. • Therefore, many experts in the United States and other western countries recommend that such lesions be termed “high-grade dysplasia. ”

• Regardless of how they are described by a pathologist, such lesions must be understood by clinicians to have negligible risk of lymphatic or distant spread and are thus considered “benign. ” • That is, all lesions with highgrade dysplasia that are completely resected endoscopically have been cured, and do not require salvage surgical treatment.

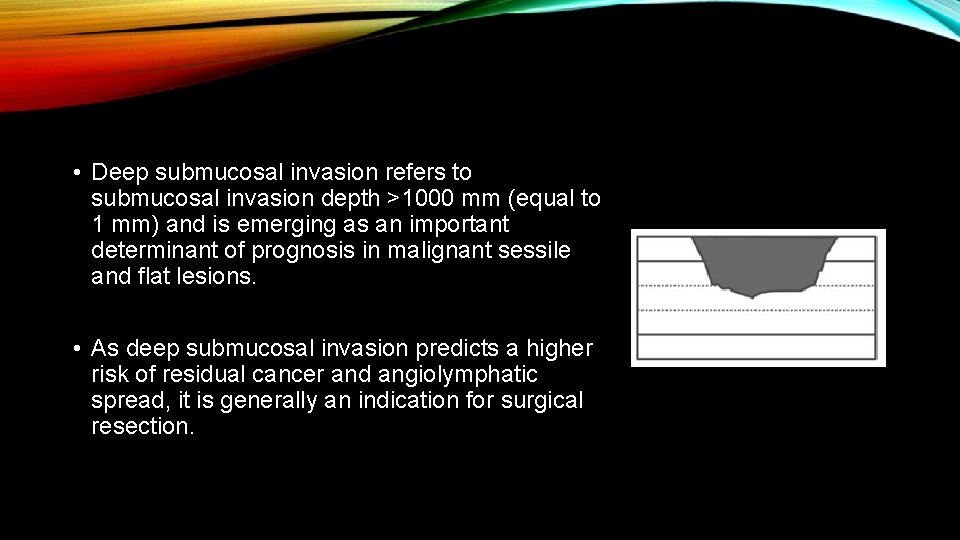

• Deep submucosal invasion refers to submucosal invasion depth >1000 mm (equal to 1 mm) and is emerging as an important determinant of prognosis in malignant sessile and flat lesions. • As deep submucosal invasion predicts a higher risk of residual cancer and angiolymphatic spread, it is generally an indication for surgical resection.

• Superficial submucosal invasion refers to submucosal invasion depth <1000 mm, and is associated with a much lower risk of residual cancer in bowel wall angiolymphatic spread.

• However, accurate measurement of depth of invasion requires en bloc endoscopic resection, special handling of the resected specimen, and a trained pathologist.

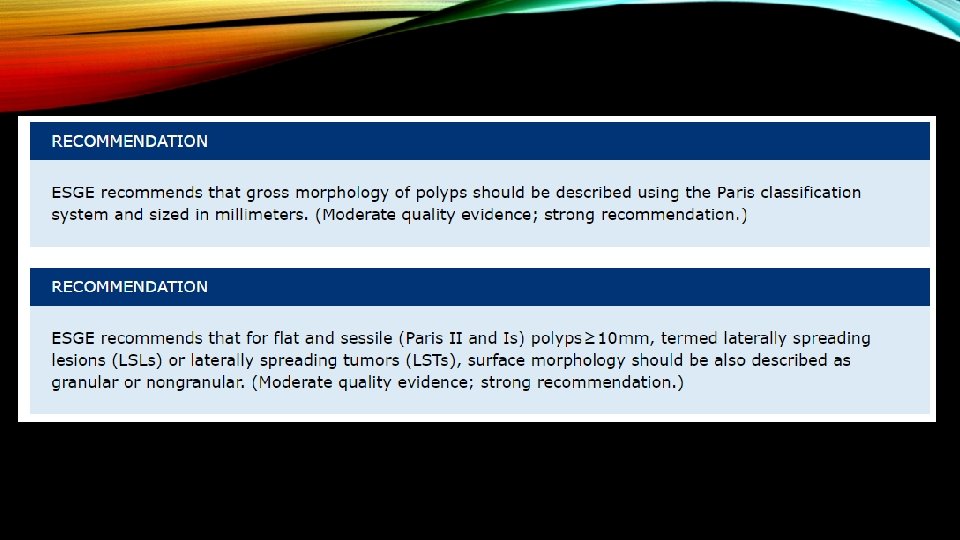

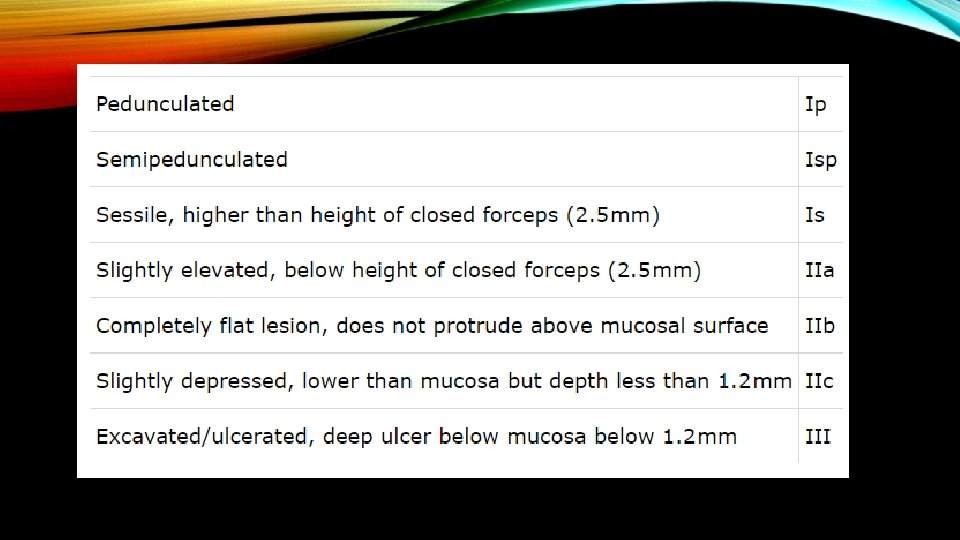

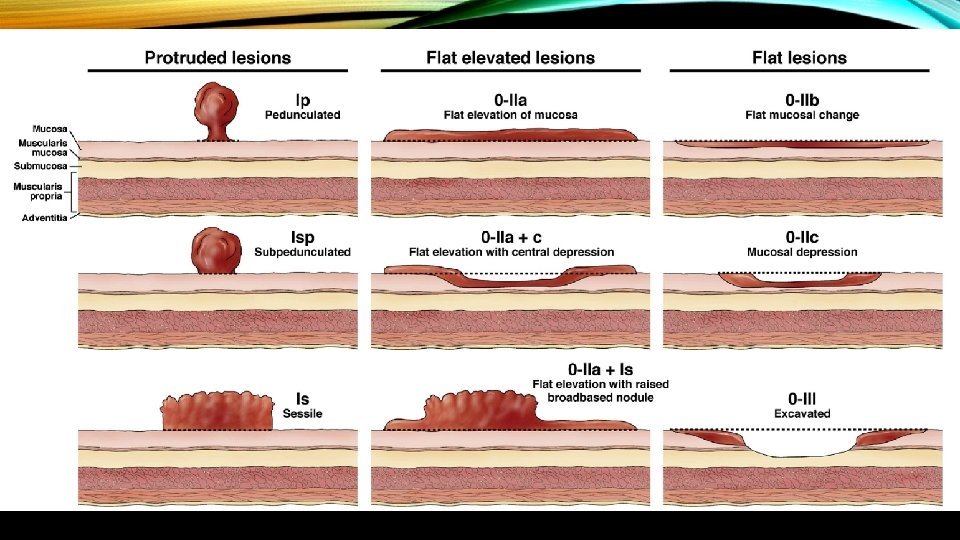

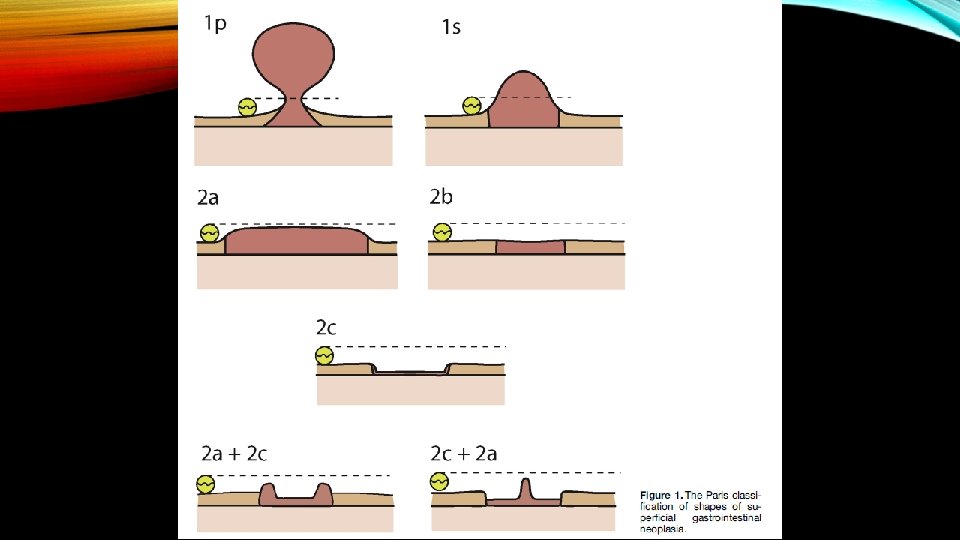

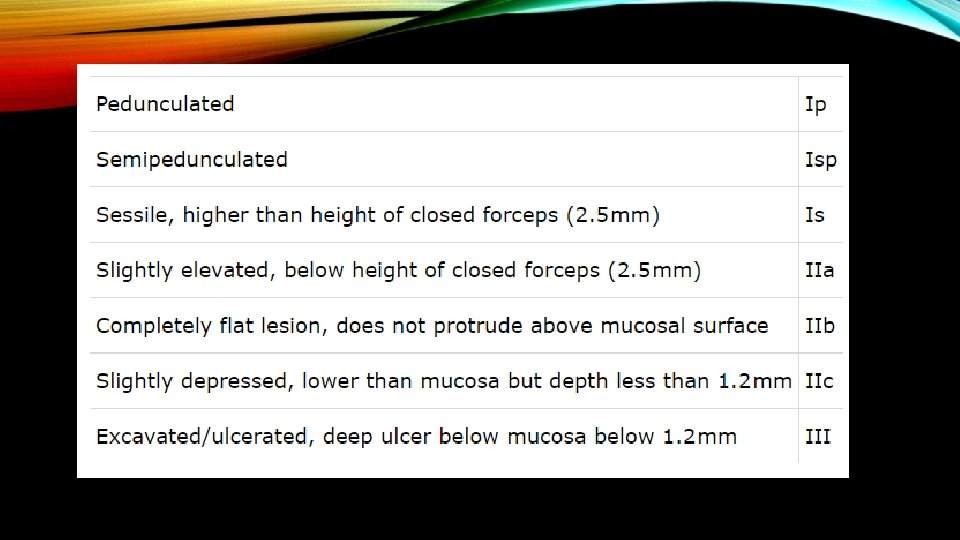

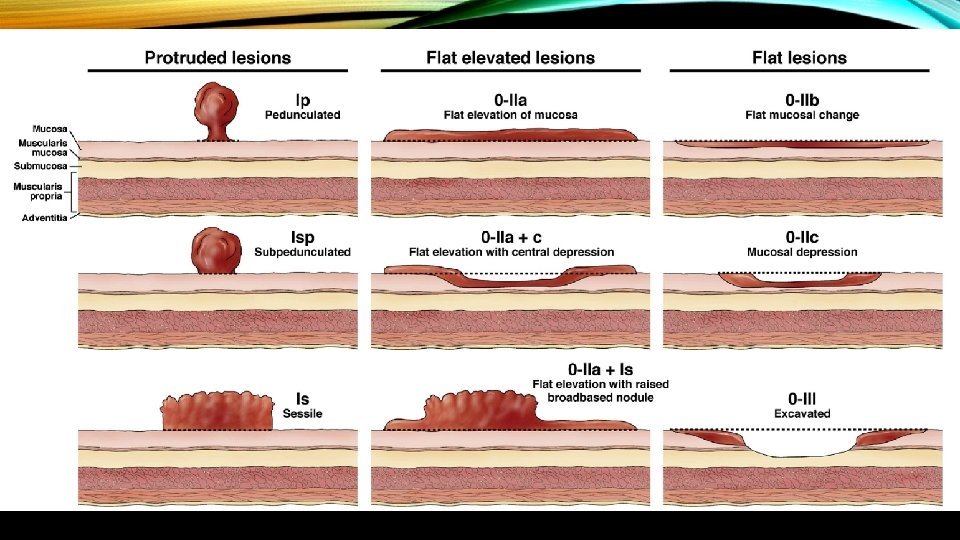

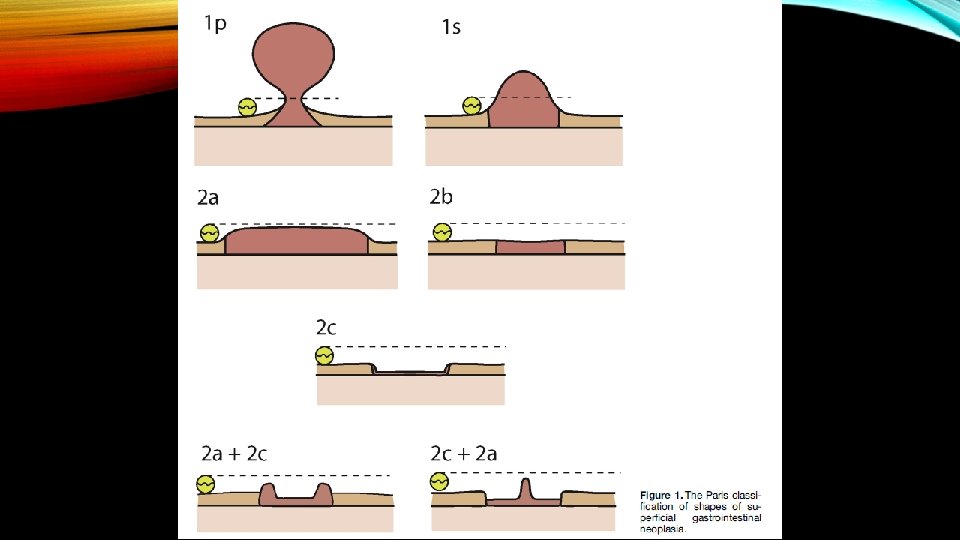

Paris 0 -1 ≤ 5 mm lesions have essentially 0% risk of harboring invasive cancer to 90% for 0 -III > 15 mm lesions. In general Paris 0 -2 B and 0 -2 C carry higher risk of colorectal invasion and high grade dysplasia. Depressed lesions with ulcerations or gross wall deformity have a high probability of harboring deeply invasive cancer.

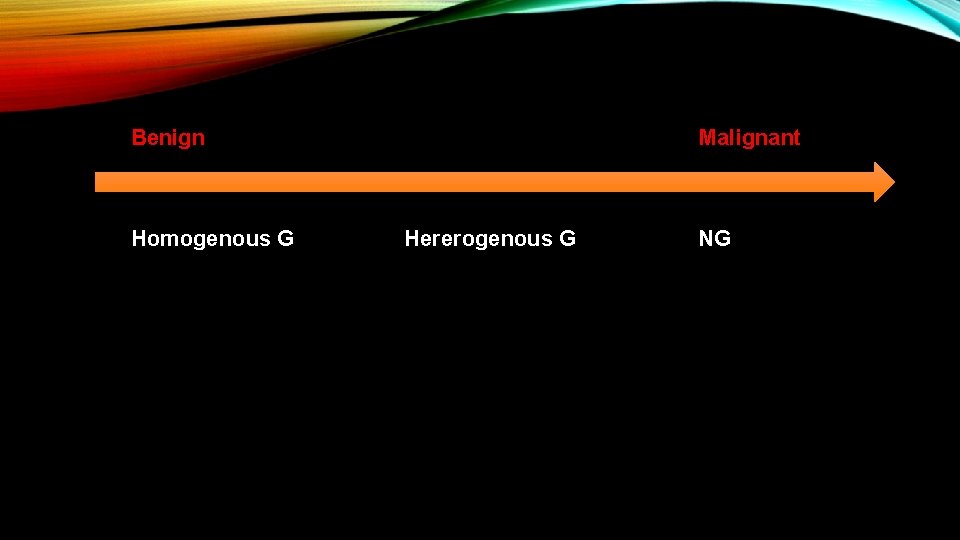

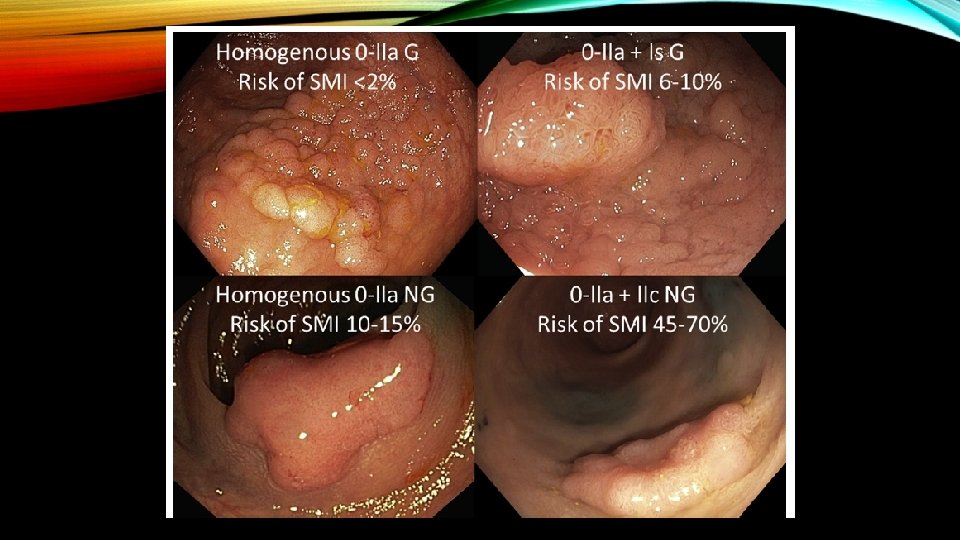

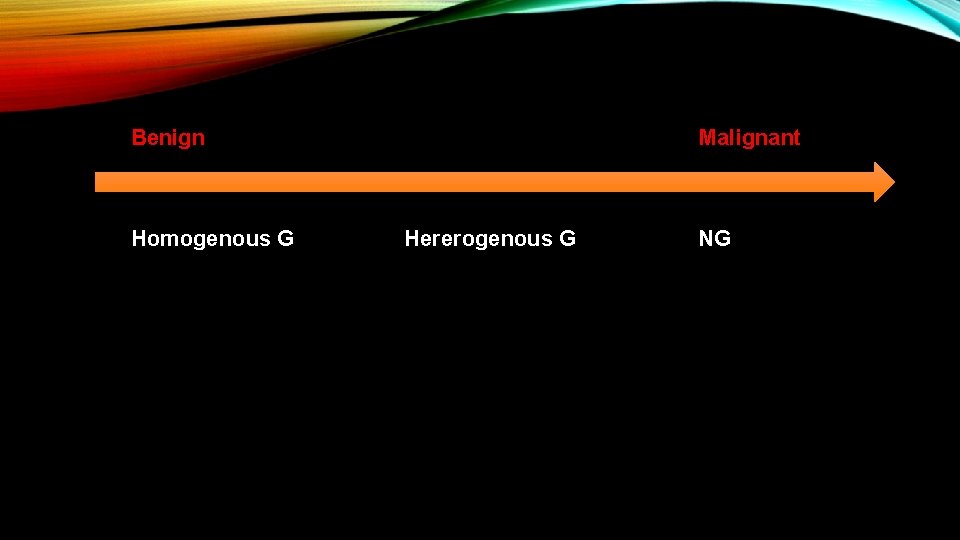

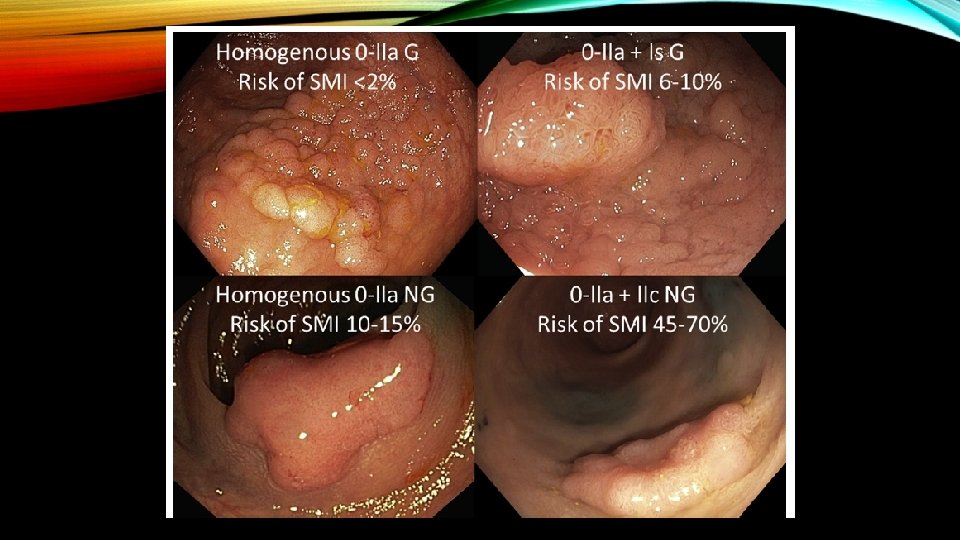

LST-Gs smooth surface(homogenous) have lower risk of local invasion (<2%) compared to LST-Gs with mixed-size nodules (heterogenous) (7% for <20 mm and 38% for >30 mm). The risk of invasion further increases for LST-NGs type having thinner center (also called as pseudo-depression): 12. 5% for <20 mm and 83% for >30 mm.

Benign Homogenous G Malignant Hererogenous G NG

• The surface is also assessed for features that predict deep submucosally invasive cancer (Narrow Band Imaging International Colorectal Endoscopic Classification [NICE] Type 3 features or Kudo class V/Vn).

Numerous endoscopic technologies including i. Scan, flexible spectral imaging colour enhancement (FICE) and narrow band imaging (NBI) have been available to assist in interrogating the surface pattern and microvascular architecture of colorectal polyps. Several studies have demonstrated that NBI is equivalent to chromoendoscopy in distinguishing neoplastic and nonneoplastic colonic polyps. SUBRAMANIAM V. GASTROINTEST ENDOSC 2009; 69: AB 277

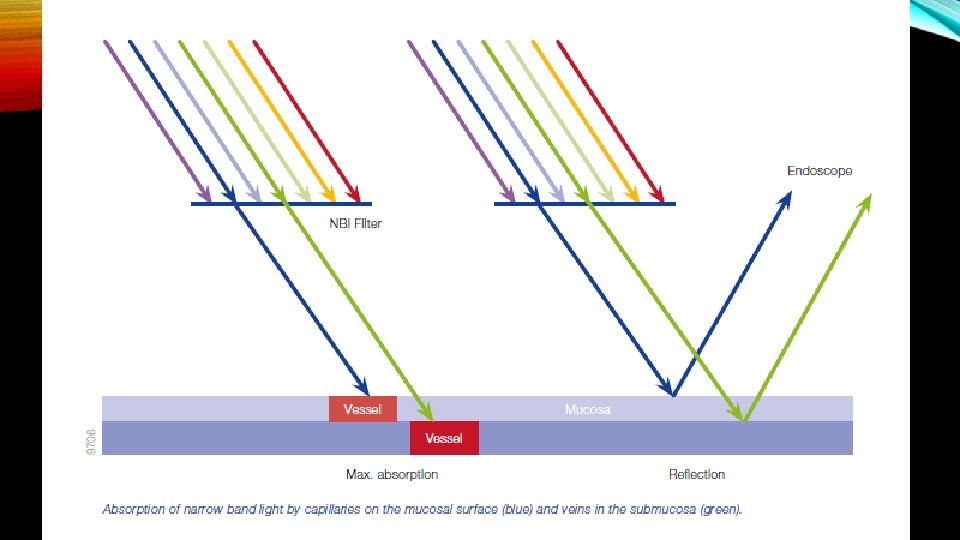

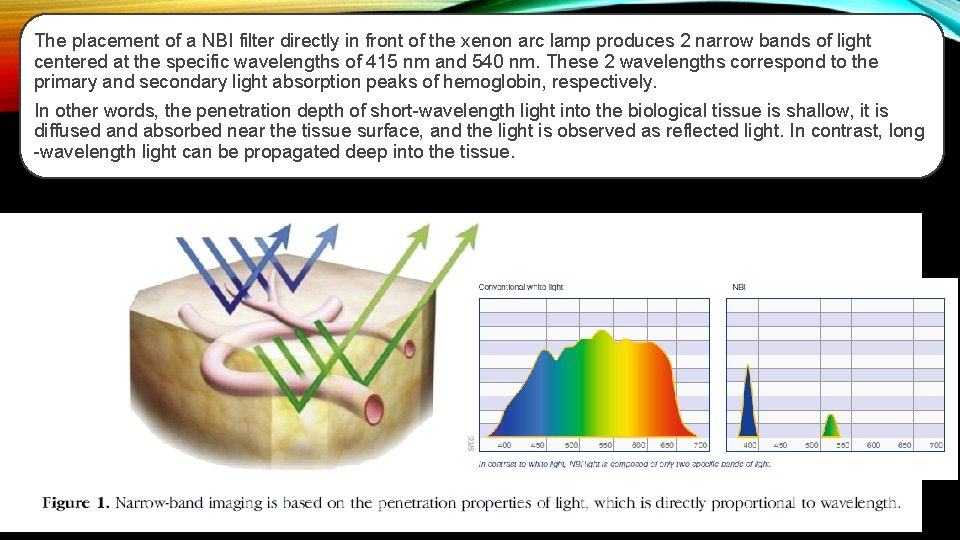

Narrow-band imaging NBI is an endoscopic optical image enhancement technology, proprietary of Olympus Medical Systems. NBI is based on the penetration properties of light, which is directly proportional to wavelength. Short wavelengths penetrate only superficially into the mucosa, whereas longer wavelengths are capable of penetrating more deeply into tissue.

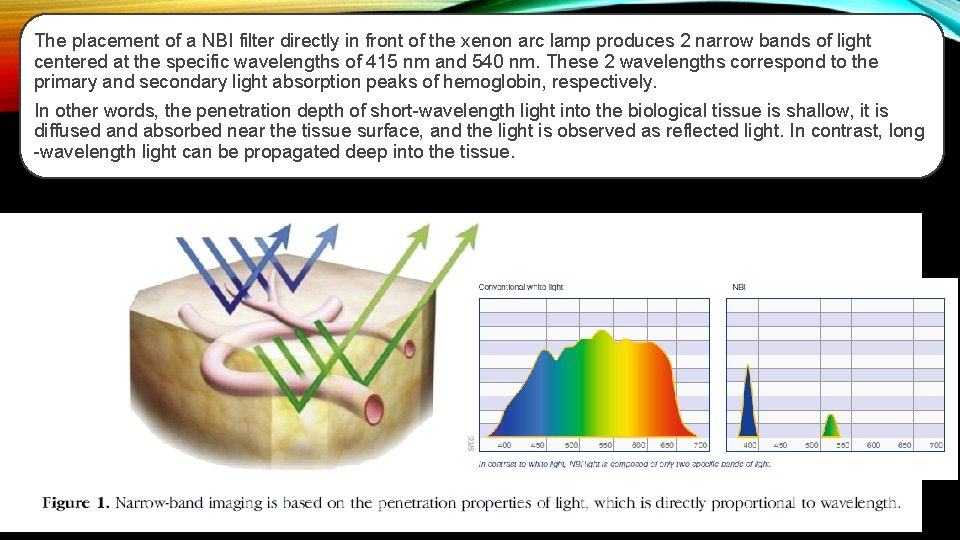

The placement of a NBI filter directly in front of the xenon arc lamp produces 2 narrow bands of light centered at the specific wavelengths of 415 nm and 540 nm. These 2 wavelengths correspond to the primary and secondary light absorption peaks of hemoglobin, respectively. In other words, the penetration depth of short-wavelength light into the biological tissue is shallow, it is diffused and absorbed near the tissue surface, and the light is observed as reflected light. In contrast, long -wavelength light can be propagated deep into the tissue.

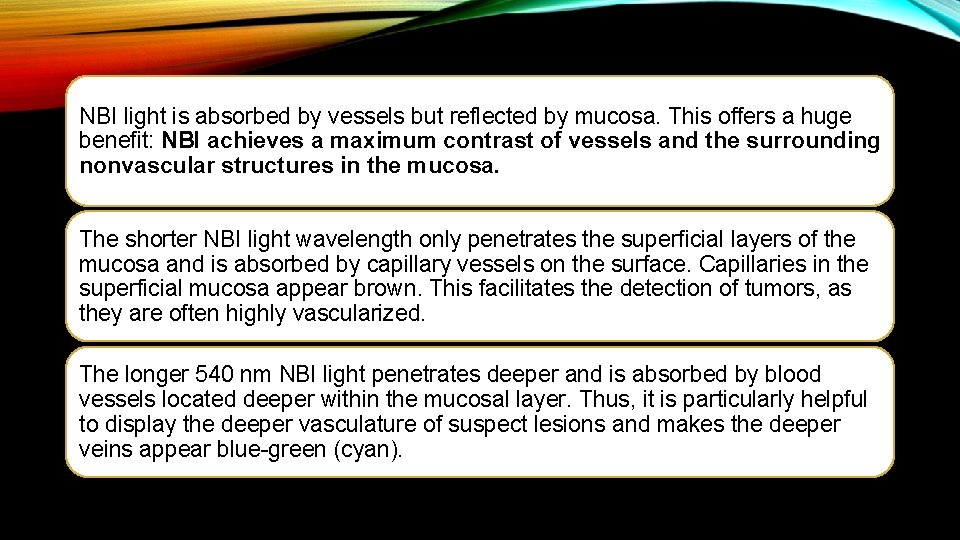

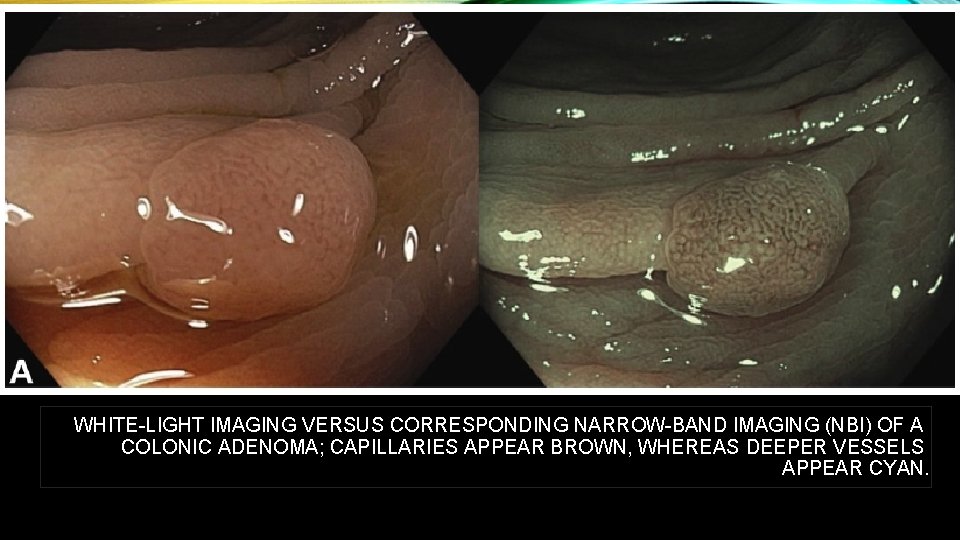

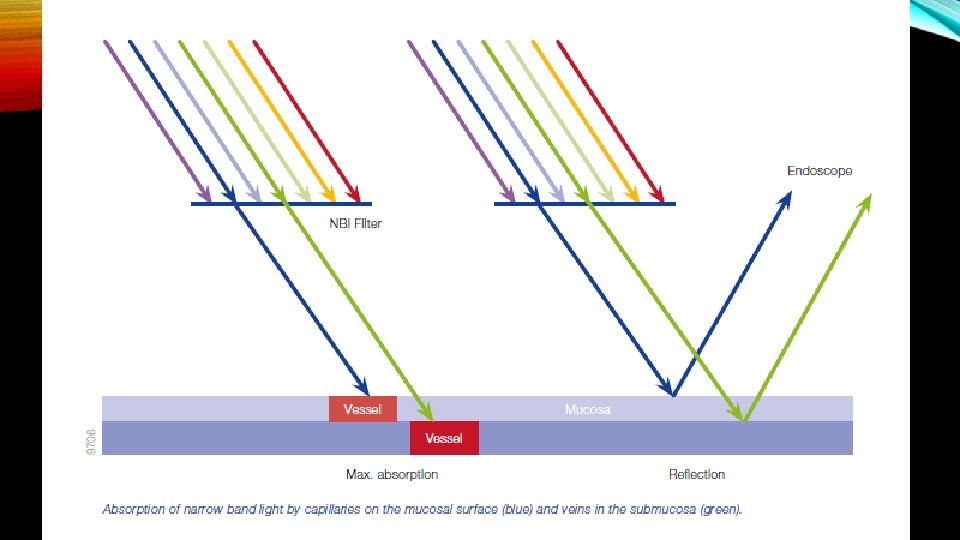

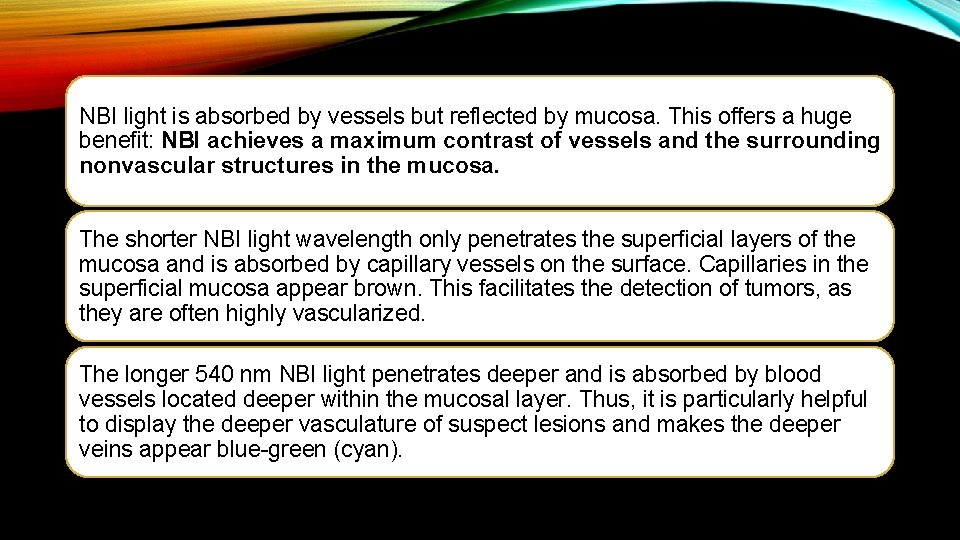

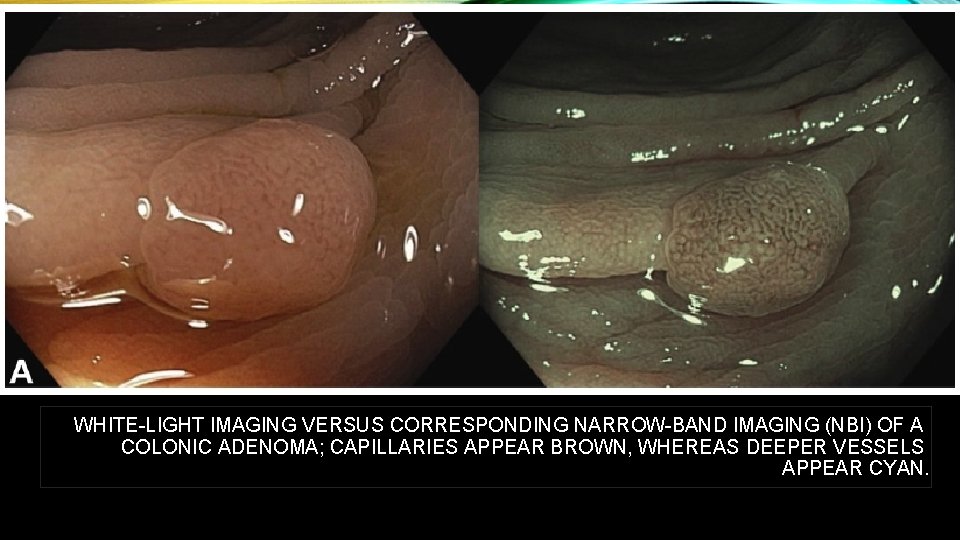

NBI light is absorbed by vessels but reflected by mucosa. This offers a huge benefit: NBI achieves a maximum contrast of vessels and the surrounding nonvascular structures in the mucosa. The shorter NBI light wavelength only penetrates the superficial layers of the mucosa and is absorbed by capillary vessels on the surface. Capillaries in the superficial mucosa appear brown. This facilitates the detection of tumors, as they are often highly vascularized. The longer 540 nm NBI light penetrates deeper and is absorbed by blood vessels located deeper within the mucosal layer. Thus, it is particularly helpful to display the deeper vasculature of suspect lesions and makes the deeper veins appear blue-green (cyan).

WHITE-LIGHT IMAGING VERSUS CORRESPONDING NARROW-BAND IMAGING (NBI) OF A COLONIC ADENOMA; CAPILLARIES APPEAR BROWN, WHEREAS DEEPER VESSELS APPEAR CYAN.

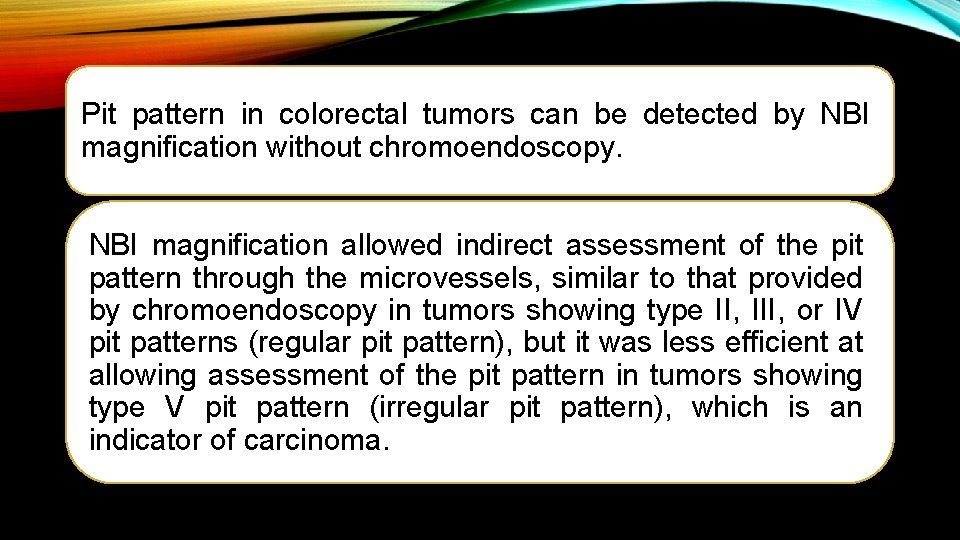

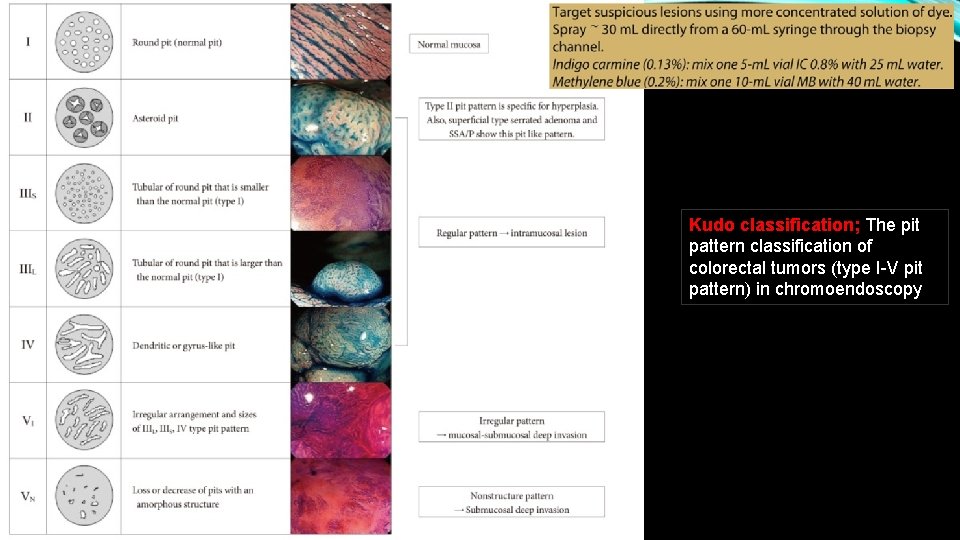

Pit pattern in colorectal tumors can be detected by NBI magnification without chromoendoscopy. NBI magnification allowed indirect assessment of the pit pattern through the microvessels, similar to that provided by chromoendoscopy in tumors showing type II, III, or IV pit patterns (regular pit pattern), but it was less efficient at allowing assessment of the pit pattern in tumors showing type V pit pattern (irregular pit pattern), which is an indicator of carcinoma.

NBI has several advantages over chromoendoscopy. For example, it allows the acquisition of endoscopic images with a uniform mucosal pattern across images without dye-spraying. Furthermore, it enables enhanced visualization of vascular features on the mucosal surfaces of lesions that would be difficult to observe by chromoendoscopy, thus augmenting the diagnostic accuracy. To date, many reports have highlighted the clinical usefulness, improved diagnostic accuracy, and increased sensitivity of NBI magnification for observing the surface microstructure (i. e. , surface pattern) together with the surface microvessels (i. e. , vascular pattern) of colorectal lesions, thus enabling the diagnoses of histologic grade and invasion depth.

Magnified chromoendoscopy

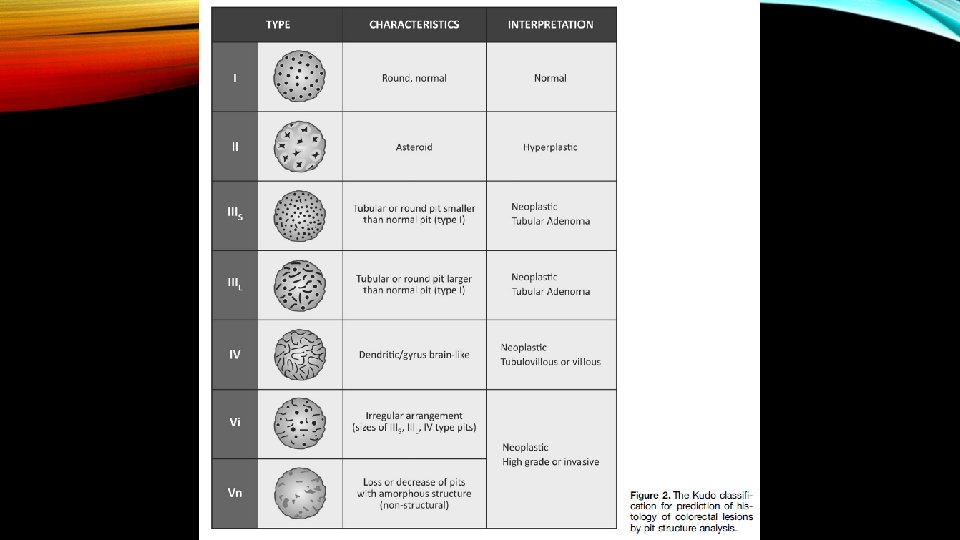

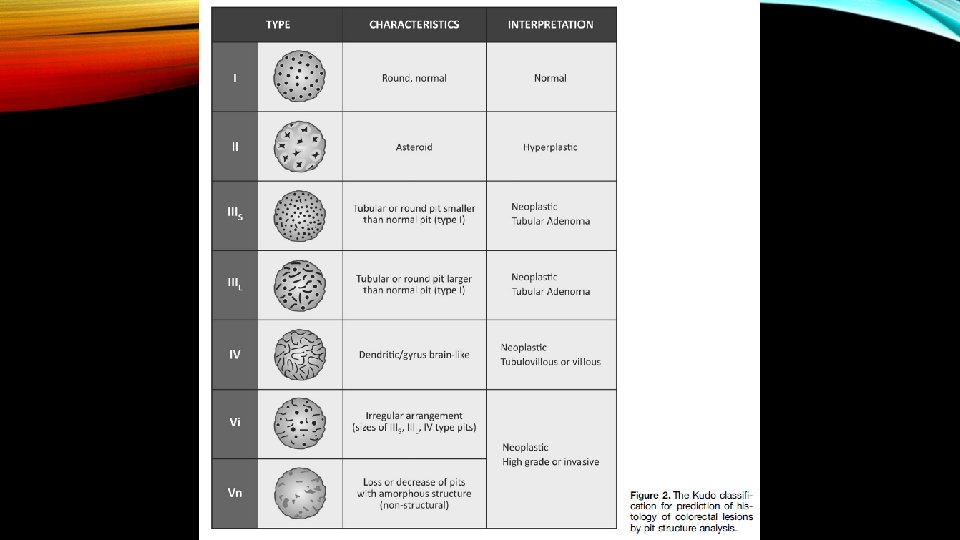

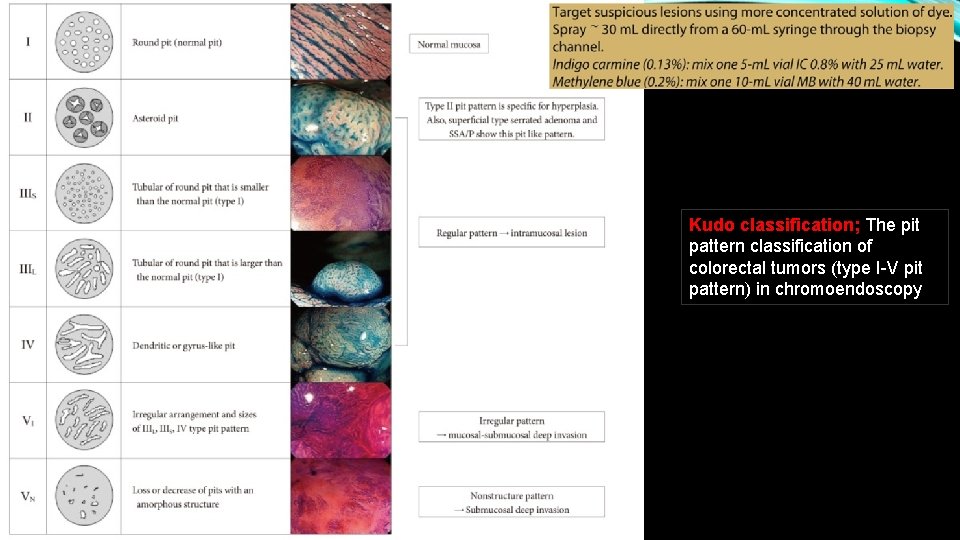

Kudo classification; The pit pattern classification of colorectal tumors (type I-V pit pattern) in chromoendoscopy

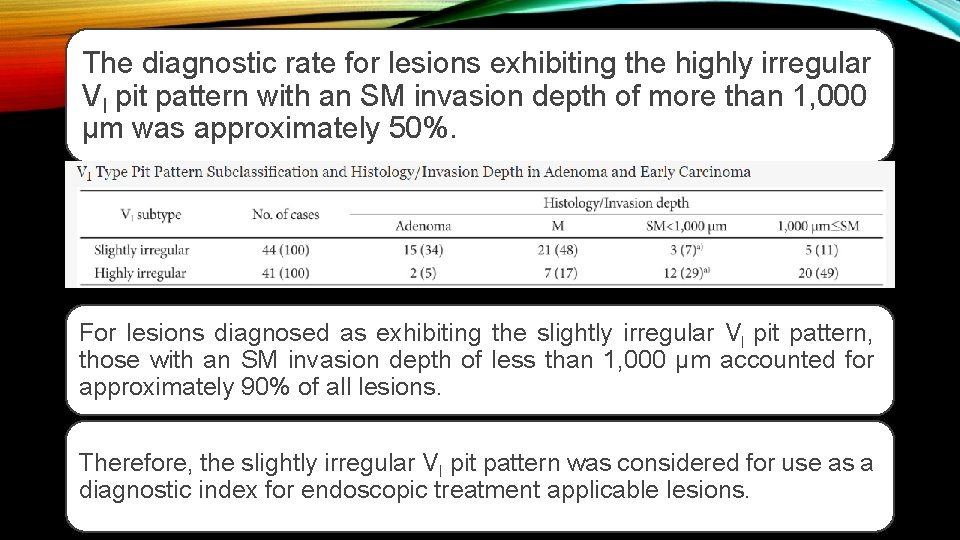

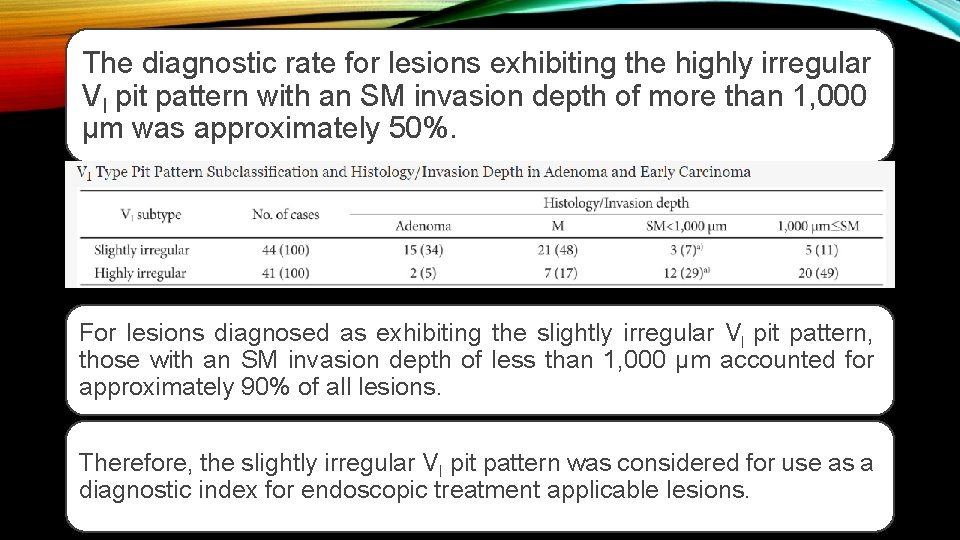

The diagnostic rate for lesions exhibiting the highly irregular VI pit pattern with an SM invasion depth of more than 1, 000 µm was approximately 50%. For lesions diagnosed as exhibiting the slightly irregular VI pit pattern, those with an SM invasion depth of less than 1, 000 µm accounted for approximately 90% of all lesions. Therefore, the slightly irregular VI pit pattern was considered for use as a diagnostic index for endoscopic treatment applicable lesions.

• Decision point : Does the lesion have endoscopic features of deep submucosal invasion?

• If the lesion has endoscopic features of deep submucosal invasion, then generally the approach should be to obtain cold biopsy specimens from the portion of the lesion that demonstrates the features, and the patient should be referred for surgical resection. • Deep submucosal invasion refers histologically to >1000 mm (1 mm) of invasion into the submucosa. This depth of invasion (which requires measurement with an optical micrometer) for accuracy, is associated with a high risk of lymph node metastases.

• When present, the endoscopic features of deep submucosal invasion are generally ulceration of the lesion surface, and inspection of the ulcerated area demonstrates disruption of the normal vascular and pit pattern. • These vascular and pit features are embodied in Type 3 of NICE and Type V/Vn of the Kudo classification.

• Only in instances of a patient who is a very poor surgical candidate should a sessile or flat lesion with endoscopic features of deep submucosal invasion undergo endoscopic resection.

• Endoscopists should understand that regardless of the method of endoscopic resection, including ESD, the presence of deep submucosal invasion generally indicates the need of surgical resection. • Thus, patients with deep submucosal invasion do not benefit from endoscopic resection including ESD.

• The previous comments do not necessary apply to a pedunculated lesion that has features of deep submucosal invasion. • In a pedunculated lesion a deeper level of submucosal invasion could still be correlated with overall favorable histologic features, and might not warrant subsequent surgical resection.

• Thus, en bloc endoscopic snare resection is acceptable in the case of pedunculated adenomas that have features in the polyp head consistent with deep submucosal invasion (eg, ulceration, NICE Type 3 features, Kudo Vn pits, stiffness in the polyp head, unusual thickening of the stalk).

• Large pedunculated polyps, regardless of whethere are features of deep submucosal invasion in the inspected polyp head, should be resected en bloc. • That is, extensive efforts should be made to get the snare entirely over the polyp head and around the stalk only, so that the polyp head will not be resected piecemeal.

• Moving the snare further down the stalk toward the bowel wall increases the chance that any cancer present will be adequately resected. • To correctly assess any cancer that may be present, the pedunculated polyp should be bisected through the head and stalk of the polyp by the pathology department.

• Decision point : If the lesion lacks features of deep submucosal invasion, then generally it is a candidate for endoscopic resection, either locally if there is sufficient endoscopic expertise, or at a center with advanced endoscopic expertise.

• Unfortunately, unlike the case for endoscopic features of deep submucosal invasion, there are no endoscopic predictors of superficial submucosal invasion that have adequate sensitivity or specificity. • The endoscopist can only identify predictors associated with a relatively increased risk of superficial invasion, while realizing most lesions with these features will have no submucosal invasion.

• From the perspective of endoscopic resection, these issues apply only to nonpedunculated polyps. • Pedunculated lesions lacking features of deep submucosal invasion but with substantial size should, like all pedunculated lesions, be resected en bloc, and in the case of large size some consideration should be given to moving the snare close to the bowel wall. • This positioning increases the length of stalk on the specimen, and increases the possibility of a clear resection margin in pedunculated malignant polyps.

• For lesions with a broad attachment to the colon wall (nonpedunculated), and lacking endoscopic features of deep submucosal invasion, an increased risk of superficial submucosal invasion is associated with nongranular morphology (particularly with depression or bulky sessile shape), with depression in granular lateral spreading tumors (G-LST), and with dominant nodules in G-LSTs.

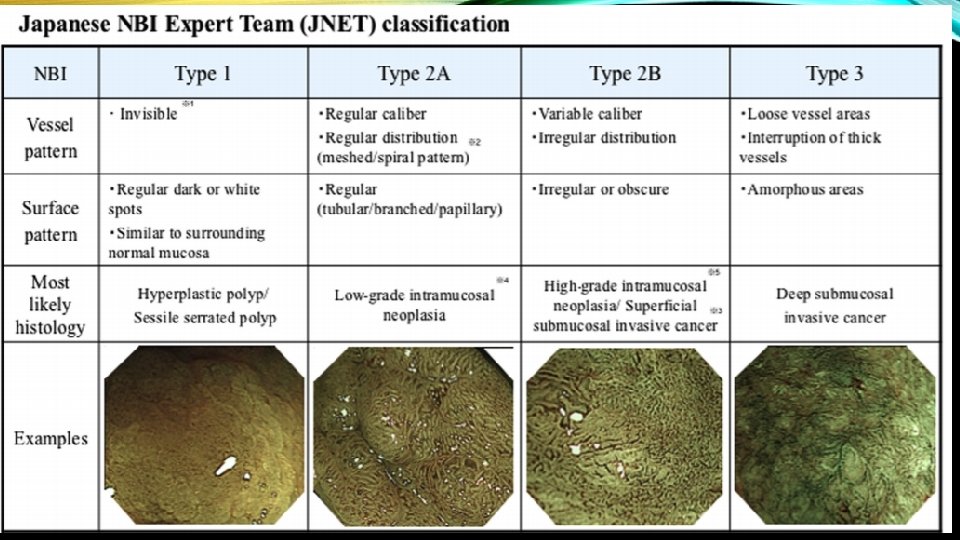

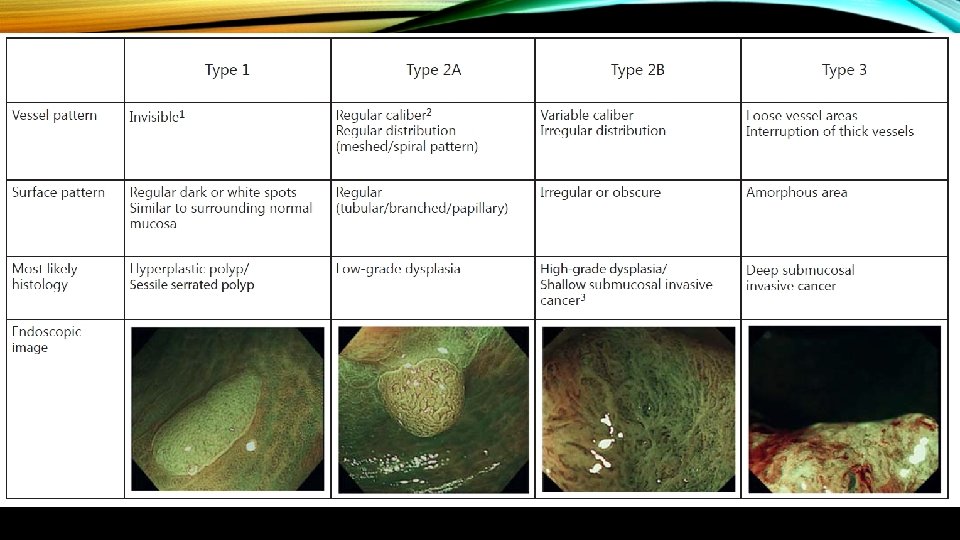

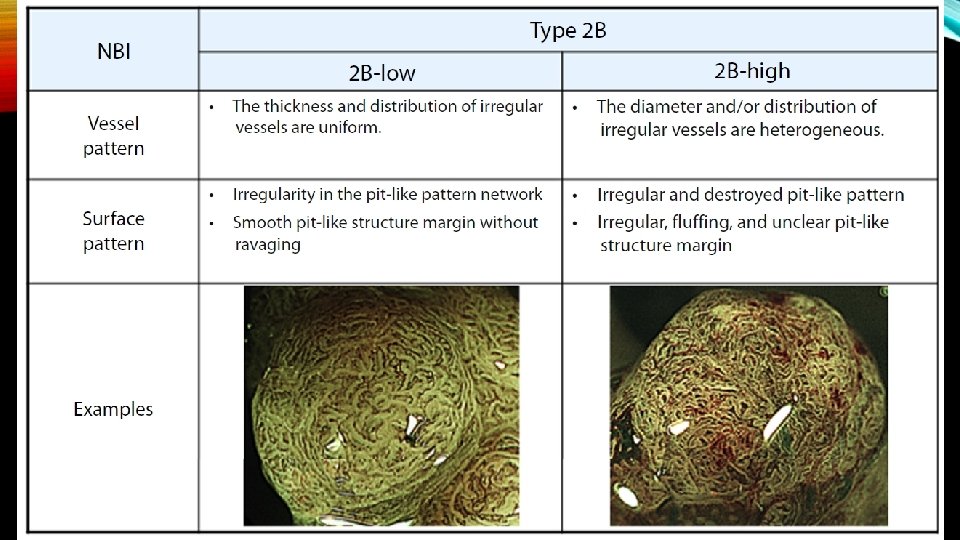

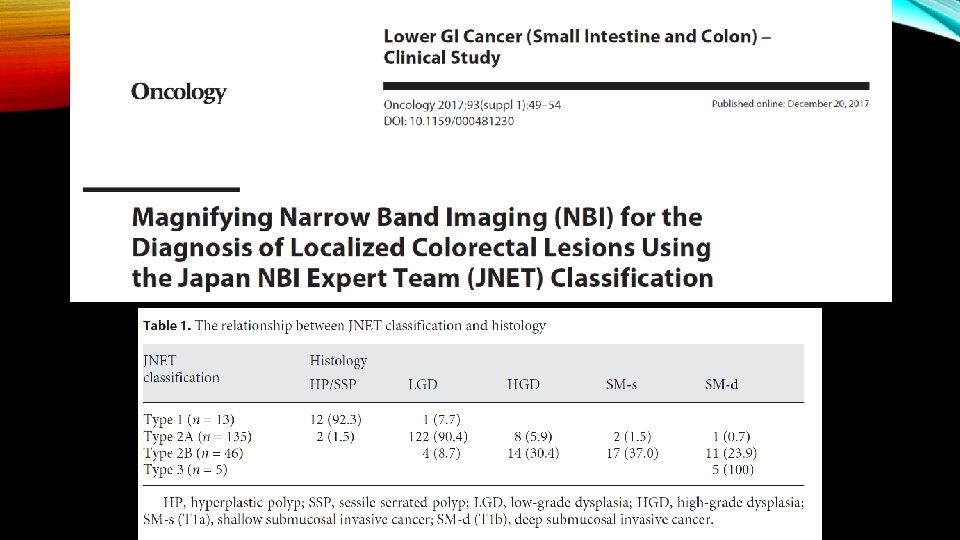

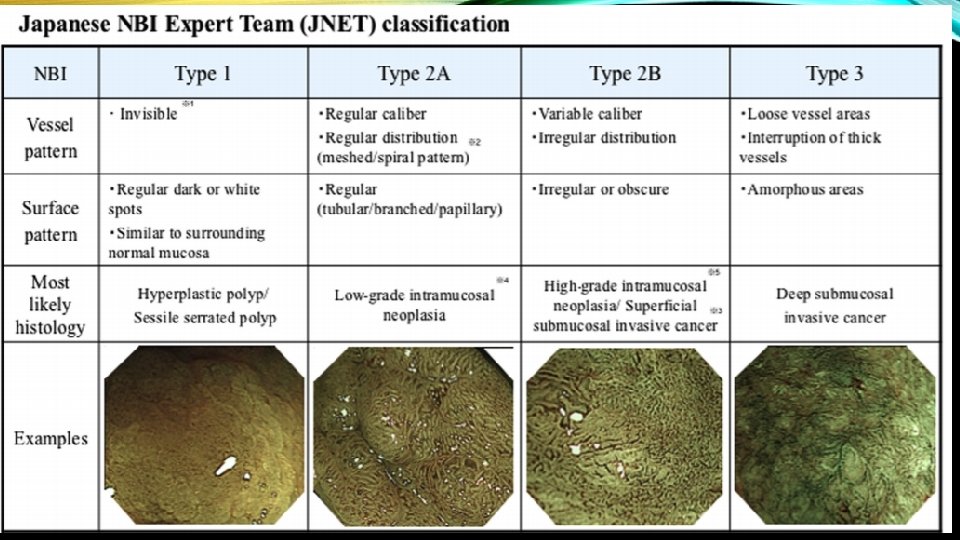

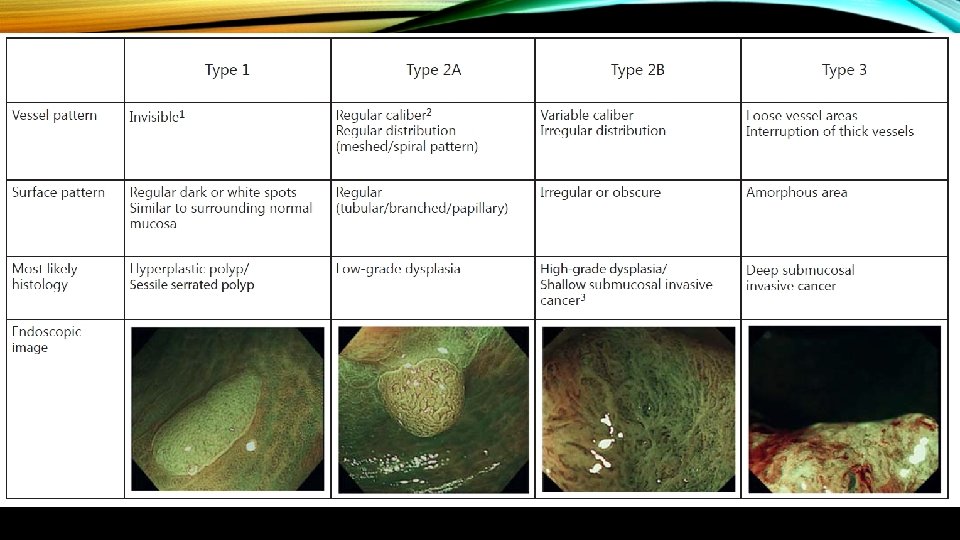

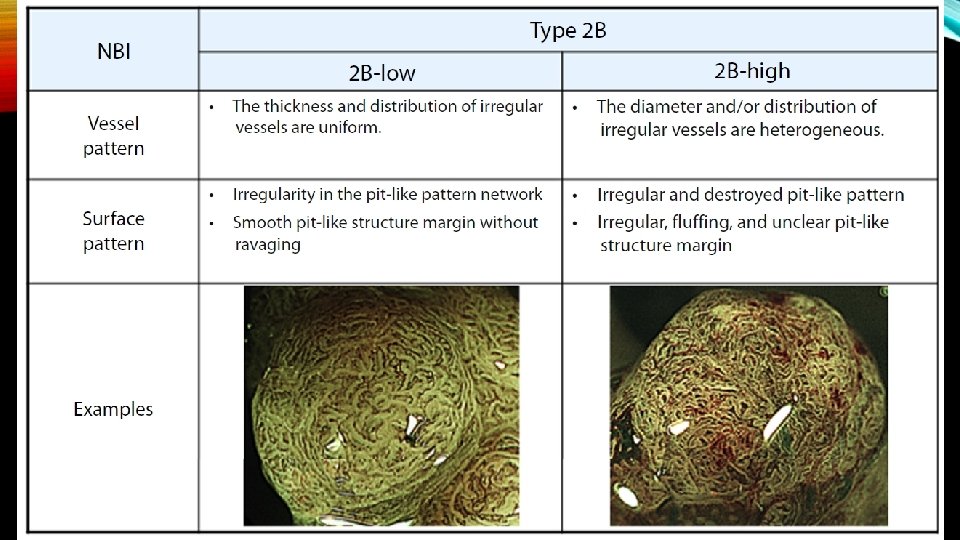

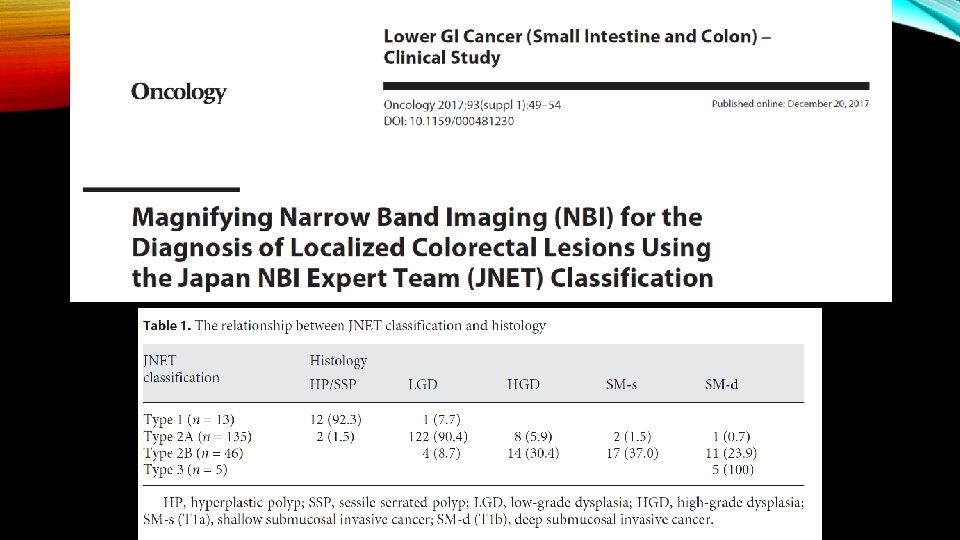

• The surface pattern is also helpful at predicting superficial submucosal invasion. Recently, the Japan Narrow Band Imaging Expert Team Classification (JNET) expands on the NICE to divide the NICE Type 2 lesions (conventional adenomas) into JNET Type 2 A and Type 2 B , with Type 2 B having an increased risk of superficial submucosal invasion.

• In addition to an en bloc resection, endoscopists should pin the resected specimen on cork board or similar material so it lays flat before adding it to the formalin container. • If the specimen is placed directly into formalin without pinning, the edges will curl, rendering the measurement of submucosal invasion depth inaccurate. Assessment of the lateral margins may also be compromised.

• For lesions with features associated with an increased risk of superficial submucosal invasion and <2 cm in diameter, en bloc resection can be achieved by using EMR or ESD. Lesions >2 cm usually require ESD to achieve en bloc resection.

• Decision point : The polyp has been resected, and the pathology report demonstrates cancer (submucosal invasion). Should the patient undergo surgical resection? The question generally implies that the lesion was resected en bloc.

• In the case of a pedunculated polyp that has been resected piecemeal, or has not been correctly sectioned in the pathology department so that the both the polyp head and the stalk can be assessed, proper assessment of the malignant features of the polyp may not be possible, and surgical resection may be the best course.

• In a case of a malignant nonpedunculated polyp resected piecemeal, surgical therapy is generally the preferred course.

• In the case of en bloc resection, the approach to deciding on the need for subsequent surgical resection will vary between pedunculated and nonpedunculated polyps:

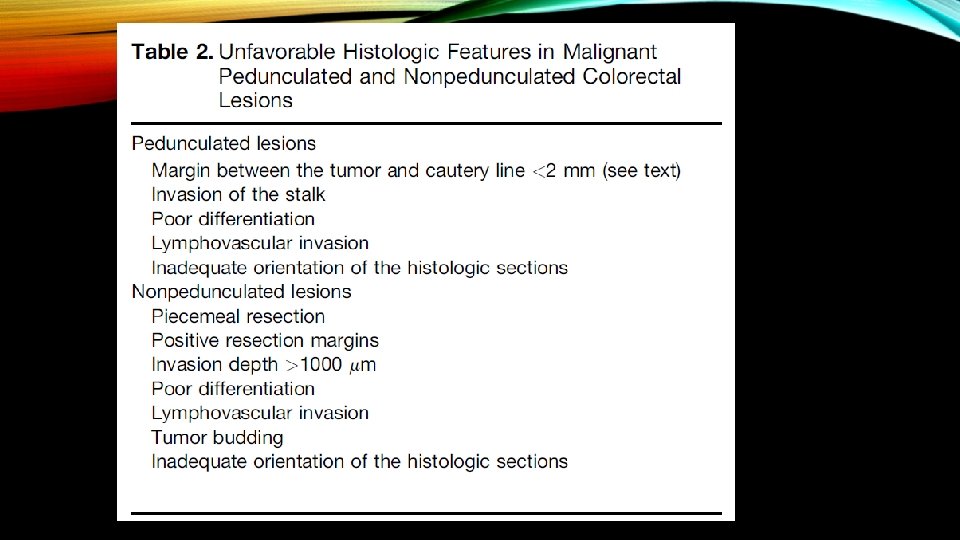

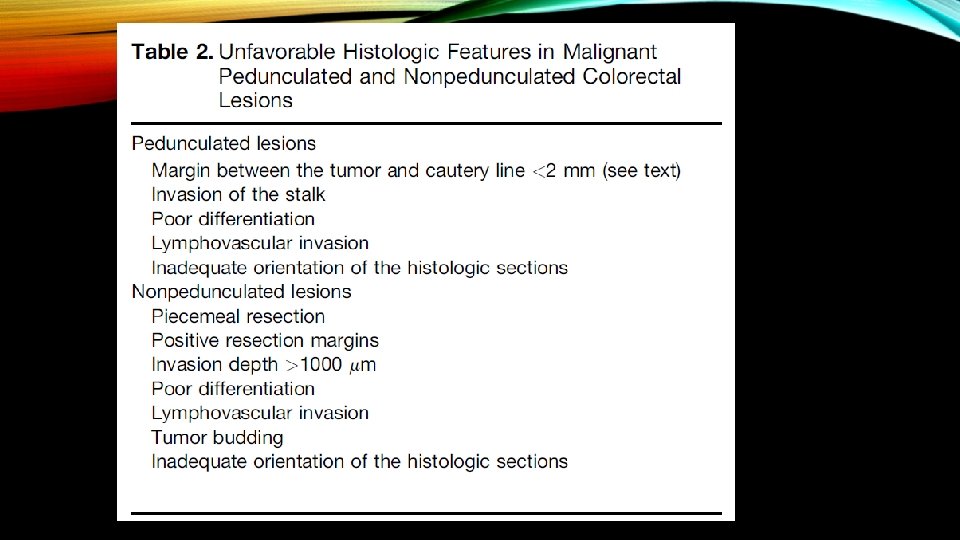

ESTIMATING THE RISK OF RESIDUAL CANCER IN THE BOWEL WALL AND LYMPH NODES AFTER ENDOSCOPIC RESECTION OF MALIGNANT PEDUNCULATED POLYPS • When submucosal invasion (adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum) is identified in an endoscopically resected polyp, the pathologist must comment on the presence or absence of specific features associated with an increased risk of residual cancer in the bowel wall or lymph nodes. • The presence of one or more of these features are generally referred to as the presence of “unfavorable histologic criteria, ” and would warrant a decision to proceed with surgical resection, unless the risk of surgical resection is considered to outweigh the risk of residual cancer.

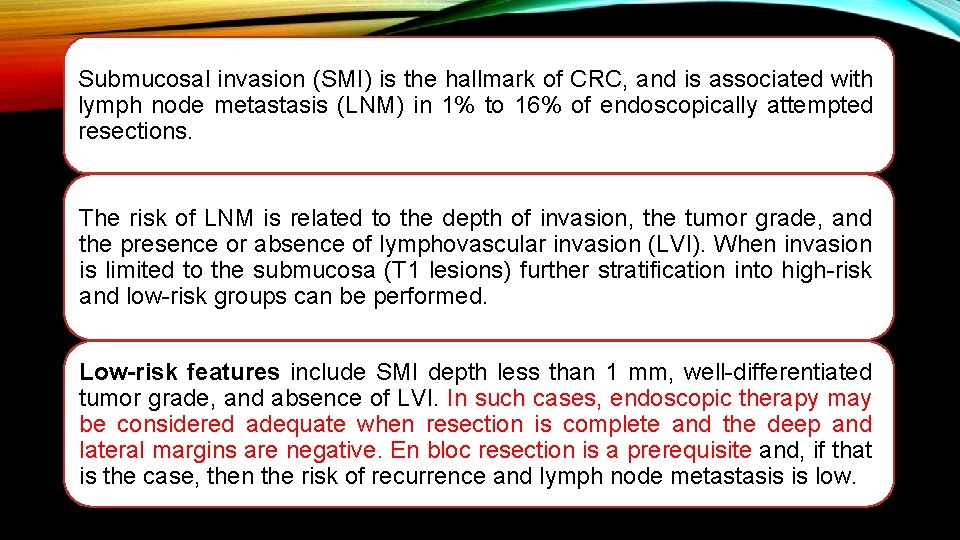

Submucosal invasion (SMI) is the hallmark of CRC, and is associated with lymph node metastasis (LNM) in 1% to 16% of endoscopically attempted resections. The risk of LNM is related to the depth of invasion, the tumor grade, and the presence or absence of lymphovascular invasion (LVI). When invasion is limited to the submucosa (T 1 lesions) further stratification into high-risk and low-risk groups can be performed. Low-risk features include SMI depth less than 1 mm, well-differentiated tumor grade, and absence of LVI. In such cases, endoscopic therapy may be considered adequate when resection is complete and the deep and lateral margins are negative. En bloc resection is a prerequisite and, if that is the case, then the risk of recurrence and lymph node metastasis is low.

High-risk features include tumor budding, LVI, poorly differentiated tumor grade, and SMI depth greater than 1 mm. If found in an EMR specimen or predicted by endoscopic assessment, surgical resection with lymph node dissection is appropriate. Endoscopically removed high-risk lesions carry a significant risk of local and regional recurrence and this treatment cannot be considered adequate in surgically fit patients. However, multiple factors, including patient personal preference, comorbidities, surgical risk profile, location of the lesion, and potential adverse outcomes of surgery, may make endoscopic treatment a viable option in selected cases.

• Poor differentiation, which is present in about 5%– 10% of all colorectal cancers, and lymphovascular invasion, present in perhaps in 30% of all colorectal cancers, are both considered unfavorable histologic criteria. Unfortunately, both are also subject to substantial interobserver variation between pathologists.

• Tumor budding, which refers to separated small (1– 3) groups of cancer cells at the lead edge of the cancer, is less well defined as a poor histologic criterion in pedunculated lesions, but is an unwelcome feature in any malignant polyp.

• Although the original study by Basil Morson suggested the need for “clear resection margin, ” a margin of at least 1 mm is advisable, and a margin of at least 2 mm is preferred. It should be evident that the distance of the tumor from the resection line and the depth of submucosal invasion are two distinct concepts. • At least some evidence suggest that the depth of invasion can be >1000 mm in pedunculated polyps, and an excellent prognosis is preserved if all other criteria are favorable.

• Another approach to risk evaluation in malignant pedunculated polyps is the Haggett criteria, which essentially state that cancer that is confined to the polyp head (Haggett levels 1– 3) is associated with a zero risk of residual cancer, whereas the risk increases with a Haggett level 4 (cancer invading the polyp stalk).