Emerging Technologies for Games Capability Testing and Advanced

Emerging Technologies for Games Capability Testing and Advanced Direct. X Features CO 3301 Week 8

Today’s Lecture 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Hardware Capabilities Techniques and Capabilities Geometry Shader Stage Stream Output Stage Direct. X Resources

Hardware Capabilities • All lab material so far has made assumptions about graphics capabilities • Real world applications should not do this • Sometimes need to query the system capabilities: – At least ensure minimum spec is met • Adapt to machines of different power: – Enhancements available for high-end hardware – “Degrade gracefully” for lower spec machines • Also optimise data for abilities of given system

Typical Capabilities • Some key graphics capabilities: – – Available screen resolutions, refresh rates Depth and stencil buffer formats / bits per pixel Anti-aliasing abilities (FSAA / MSAA) Texture capabilities: • Minimum / maximum size • Pixel formats • Render-target / cube map / instancing etc. support – Etc. • Many render states also have capabilities to indicate the extent of their availability – E. g. Level of anisotropic filtering

Testing Capabilities • Earlier Direct. X versions needed intricate capability testing – Backwards compatibility meant that you didn’t know if you were running on legacy hardware, a problem for games • However, Direct. X 10 and above define a minimum spec – Makes capability testing easier – No need to detect / support legacy hardware • Still need some testing to check for advanced features • Consoles are largely unaffected by such matters – Specification is fixed • Still need to check for: – Hard drive size, HDTV resolutions, peripherals (controllers, cameras, etc. )

Shaders Revisited • Shaders have been a central topic of the course – The most important area of modern graphics • Shaders also have capabilities… – Shader hardware version • Shaders compiled to machine code • Shader version defines the instruction set available • Higher shader versions have more instructions, e. g. for & if statements, and higher level functions • They also have more registers – Number of instructions in a shader, depth of nesting etc. • Should provide alternative shaders: – For high and low spec machines

Multiple Passes • Complex materials need several rendering passes – i. e. render the same polygons multiple times – Each time with a different render state/shader – Each pass blended with the ones below • Example: Earth shader used in some labs: – Pass 1: Render Earth surface – diffuse lighting, texture changes between night and day based on light level – Pass 2: Render clouds – diffuse lighting, moving UVs, blue tint at a glancing angle, alpha blend with Earth – Pass 3: Render outer atmosphere - inside out (reverse culling), exaggerated diffuse lighting, alpha blend - less alpha (i. e. more transparent) at glancing angle

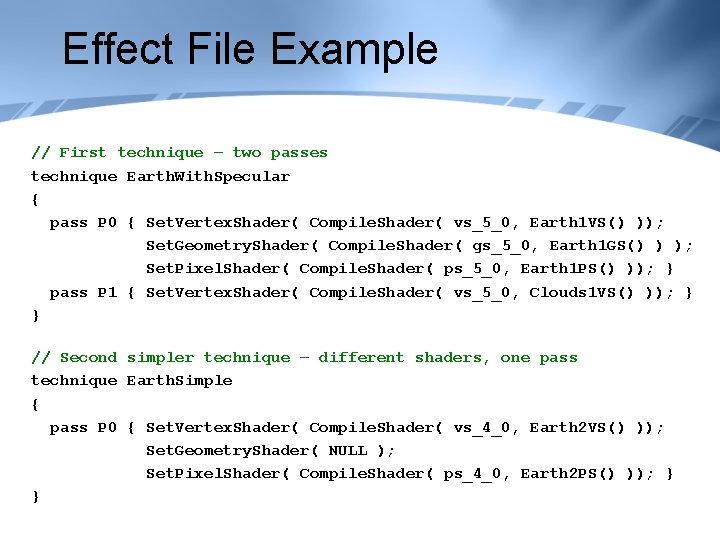

Effects Files for Capabilities • Using effects files (. fx) files we can collect together shader passes and their render states into techniques • Provide a range of techniques for different hardware specifications • If any one pass in a technique fails capability testing, then degrade to a simpler technique • The Direct. X effects file system makes this quite simple

Effect File Example // First technique – two passes technique Earth. With. Specular { pass P 0 { Set. Vertex. Shader( Compile. Shader( vs_5_0, Earth 1 VS() )); Set. Geometry. Shader( Compile. Shader( gs_5_0, Earth 1 GS() ) ); Set. Pixel. Shader( Compile. Shader( ps_5_0, Earth 1 PS() )); } pass P 1 { Set. Vertex. Shader( Compile. Shader( vs_5_0, Clouds 1 VS() )); } } // Second simpler technique – different shaders, one pass technique Earth. Simple { pass P 0 { Set. Vertex. Shader( Compile. Shader( vs_4_0, Earth 2 VS() )); Set. Geometry. Shader( NULL ); Set. Pixel. Shader( Compile. Shader( ps_4_0, Earth 2 PS() )); } }

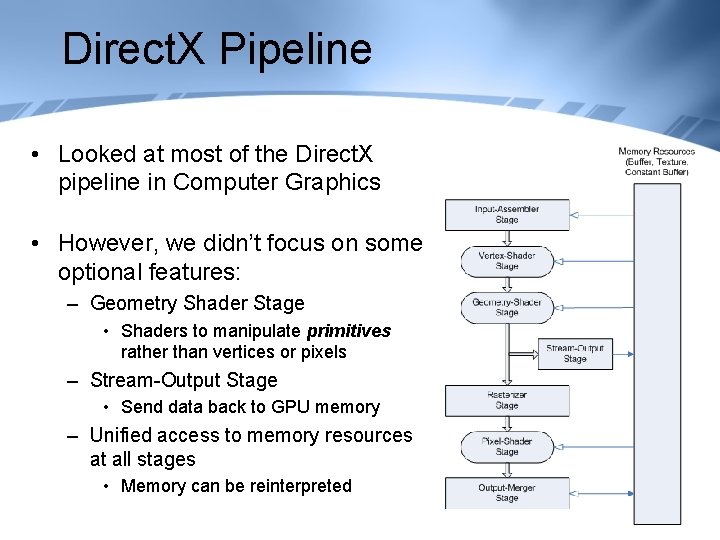

Direct. X Pipeline • Looked at most of the Direct. X pipeline in Computer Graphics • However, we didn’t focus on some optional features: – Geometry Shader Stage • Shaders to manipulate primitives rather than vertices or pixels – Stream-Output Stage • Send data back to GPU memory – Unified access to memory resources at all stages • Memory can be reinterpreted

Geometry Shaders • The new geometry shader stage processes primitives – Triangles or lines • Practically a geometry shader is much like a vertex shader, but working on multiple vertices at once – All three vertices of a triangle, or both points of a line – Allows techniques that can’t be done with only a single vertex • E. g. calculate a face normal (cross product of the triangle edges) • It operates on the output of the vertex shader – This is slightly counter-intuitive • Would expect to start at highest level and work down – Raises questions: which shader does the matrix transformations? • The geometry shader can also create or delete primitives – i. e. The output geometry can be different to the input

Geometry Input / Output • The geometry shader input is an array of vertices – The number depends on the primitive type used • E. g. 3 for triangles, 2 for lines • Geometry shader output is a stream of primitives – The stream type must be specified: • E. g. Triangles, lines etc. • But always output as a strip, not a list – The output stream doesn’t need to match the input • E. g. Could input triangles, but output lines (make a silhouette) • Or input points and output triangles (particle system) • Can output any number of primitives (including 0) – Allows the generation / deletion of primitives

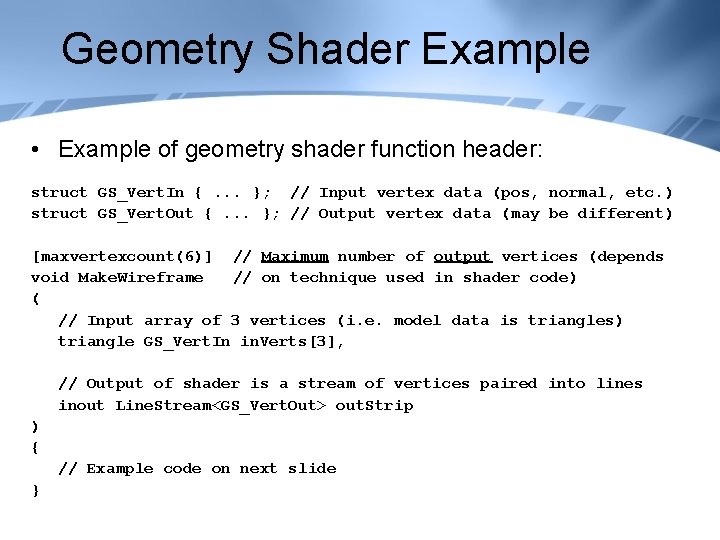

Geometry Shader Example • Example of geometry shader function header: struct GS_Vert. In {. . . }; // Input vertex data (pos, normal, etc. ) struct GS_Vert. Out {. . . }; // Output vertex data (may be different) [maxvertexcount(6)] // Maximum number of output vertices (depends void Make. Wireframe // on technique used in shader code) ( // Input array of 3 vertices (i. e. model data is triangles) triangle GS_Vert. In in. Verts[3], // Output of shader is a stream of vertices paired into lines inout Line. Stream<GS_Vert. Out> out. Strip ) { // Example code on next slide }

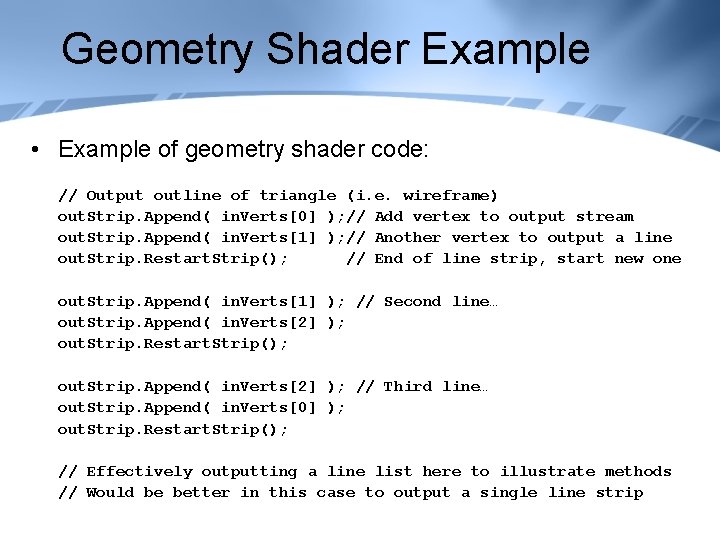

Geometry Shader Example • Example of geometry shader code: // Output outline of triangle (i. e. wireframe) out. Strip. Append( in. Verts[0] ); // Add vertex to output stream out. Strip. Append( in. Verts[1] ); // Another vertex to output a line out. Strip. Restart. Strip(); // End of line strip, start new one out. Strip. Append( in. Verts[1] ); // Second line… out. Strip. Append( in. Verts[2] ); out. Strip. Restart. Strip(); out. Strip. Append( in. Verts[2] ); // Third line… out. Strip. Append( in. Verts[0] ); out. Strip. Restart. Strip(); // Effectively outputting a line list here to illustrate methods // Would be better in this case to output a single line strip

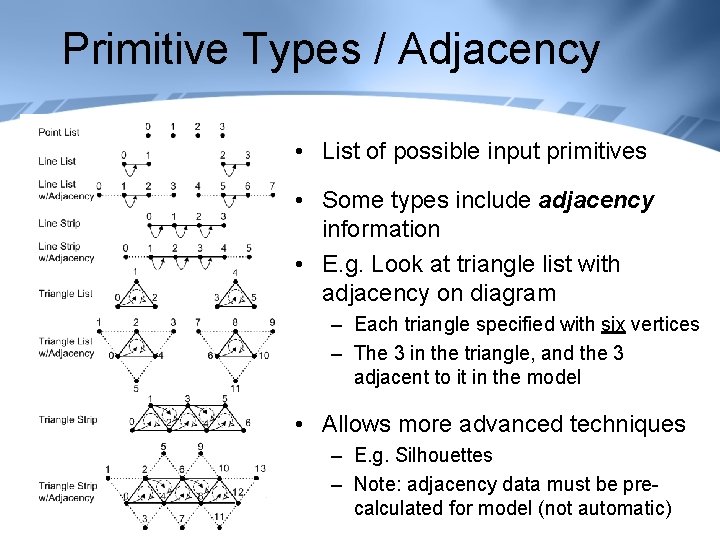

Primitive Types / Adjacency • List of possible input primitives • Some types include adjacency information • E. g. Look at triangle list with adjacency on diagram – Each triangle specified with six vertices – The 3 in the triangle, and the 3 adjacent to it in the model • Allows more advanced techniques – E. g. Silhouettes – Note: adjacency data must be precalculated for model (not automatic)

Geometry Shader Uses • Geometry shaders have a wide range of uses: – Distorting or animating geometry, especially using face normals • Face normals cannot be calculated in vertex shaders – Silhouettes using adjacency data • If one triangle faces camera (use face normal), but adjacent one faces away, then the edge between is a silhouette edge – Creating extra view-dependent geometry • Tesselation of edge on geometry for smoother silhouettes • Create “fins” for fur rendering (see later lab) – Particle systems without instancing: • Input a point list, or a line list. Generate particle geometry in shader – generate a quad for each point / line • More efficient than instancing – And many more, new ideas emerging all the time…

Geometry Shader Considerations • Geometry shaders are not needed for “traditional” geometry rendering methods – Static models, lit with standard lighting approaches – Set geometry shader to “NULL” • Performance of geometry shaders can be an issue: – Older Direct. X 10 GPU’s are not efficient at generating large amounts of new geometry – So certain techniques, e. g. tessellation, are possible with geometry shaders, but not appropriate (see later lecture on tesselation) – Newer hardware is getting better, but this is a area where fall-back methods may be appropriate

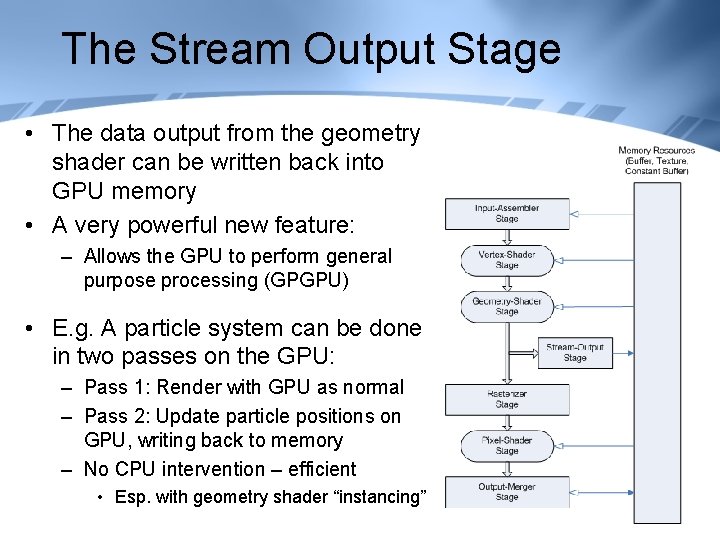

The Stream Output Stage • The data output from the geometry shader can be written back into GPU memory • A very powerful new feature: – Allows the GPU to perform general purpose processing (GPGPU) • E. g. A particle system can be done in two passes on the GPU: – Pass 1: Render with GPU as normal – Pass 2: Update particle positions on GPU, writing back to memory – No CPU intervention – efficient • Esp. with geometry shader “instancing”

Stream Output Considerations • Stream-Output cannot output to the same buffer that is being input from – However, this is usually what we want to do • Work around this by using double buffering – Create two identical buffers of data – Input from one, and output to the other – Swap the buffers between frames • Often need multiple passes to render / update geometry – Some vertex data may be needed for only one or the other pass – I. e. Likely to be some data redundancy – Example in GPU particle system lab later

- Slides: 19