EM Waves and Guide Structures Course Code ECEG4305

- Slides: 41

EM Waves and Guide Structures Course Code: ECEG-4305 Program: B Sc in ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING Course credit (hours / week): 3(2 Hours-Lecture, 3 Hours-Tutorial) Year / Semester: 4 / 1 Course Instructor: Dr. M V Raghavendra E-Mail: miriampally@gmail. com

CHAPTER I Review of Vectors and Maxwell's Equations. v. Line, Surface, & Volume Integrals v. Gradient of a Scalar field v. Divergence & Curl of a Vector Field v. Divergence & Stokes's Theorems v. Laplacian of a Scalar Field; v. Solenoidal & Irrotational Vector Fields v. Helmholtz’s Theorem v. Maxwell's Equations v. Time-Harmonic Fields. v. Boundary Conditions v. Poison’s and Laplace’s Equations 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 2

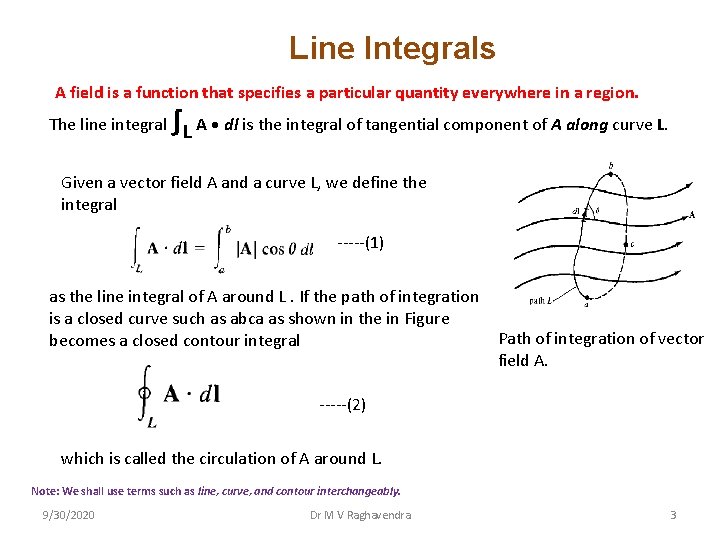

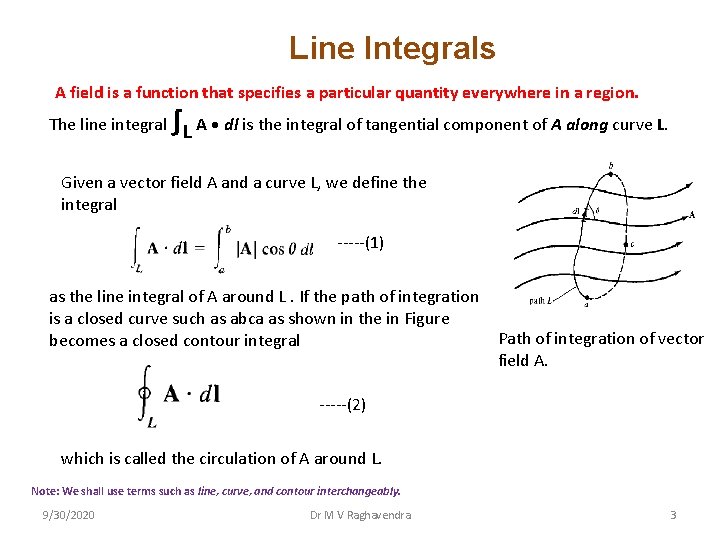

Line Integrals A field is a function that specifies a particular quantity everywhere in a region. ∫ The line integral L A • dl is the integral of tangential component of A along curve L. Given a vector field A and a curve L, we define the integral -----(1) as the line integral of A around L. If the path of integration is a closed curve such as abca as shown in the in Figure becomes a closed contour integral Path of integration of vector field A. -----(2) which is called the circulation of A around L. Note: We shall use terms such as line, curve, and contour interchangeably. 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 3

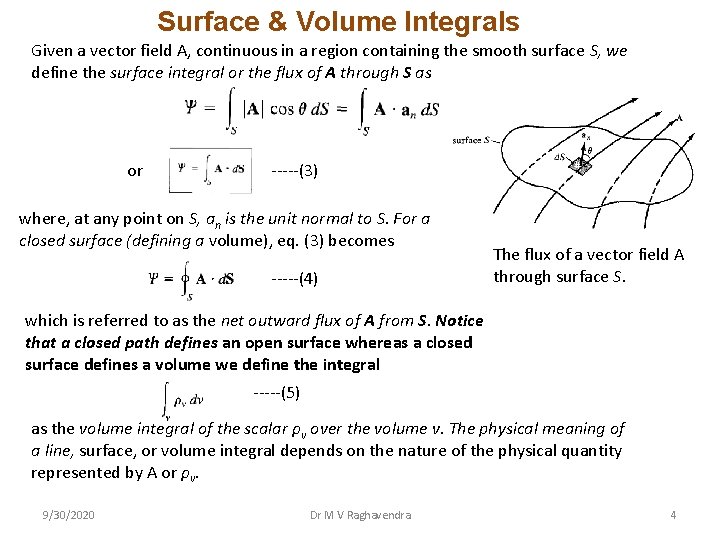

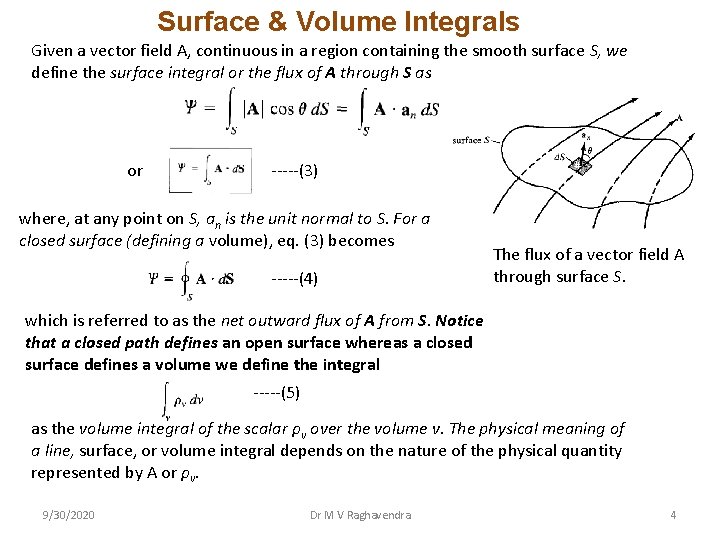

Surface & Volume Integrals Given a vector field A, continuous in a region containing the smooth surface S, we define the surface integral or the flux of A through S as or -----(3) where, at any point on S, an is the unit normal to S. For a closed surface (defining a volume), eq. (3) becomes -----(4) The flux of a vector field A through surface S. which is referred to as the net outward flux of A from S. Notice that a closed path defines an open surface whereas a closed surface defines a volume we define the integral -----(5) as the volume integral of the scalar ρv over the volume v. The physical meaning of a line, surface, or volume integral depends on the nature of the physical quantity represented by A or ρv. 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 4

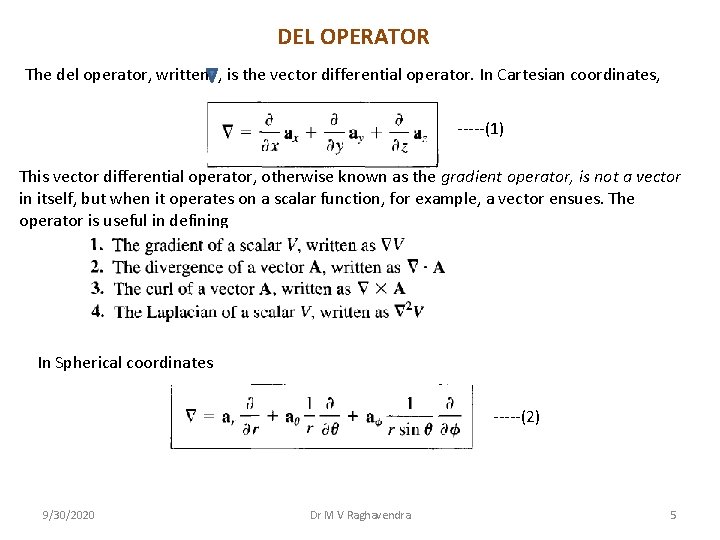

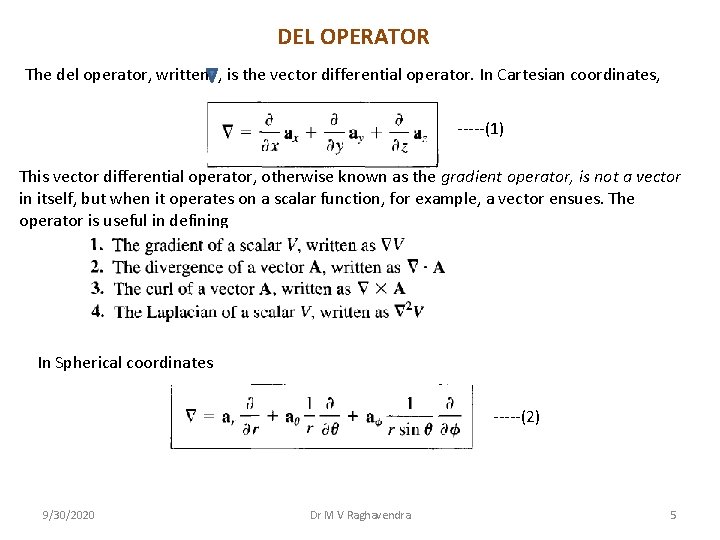

DEL OPERATOR The del operator, written , is the vector differential operator. In Cartesian coordinates, -----(1) This vector differential operator, otherwise known as the gradient operator, is not a vector in itself, but when it operates on a scalar function, for example, a vector ensues. The operator is useful in defining In Spherical coordinates -----(2) 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 5

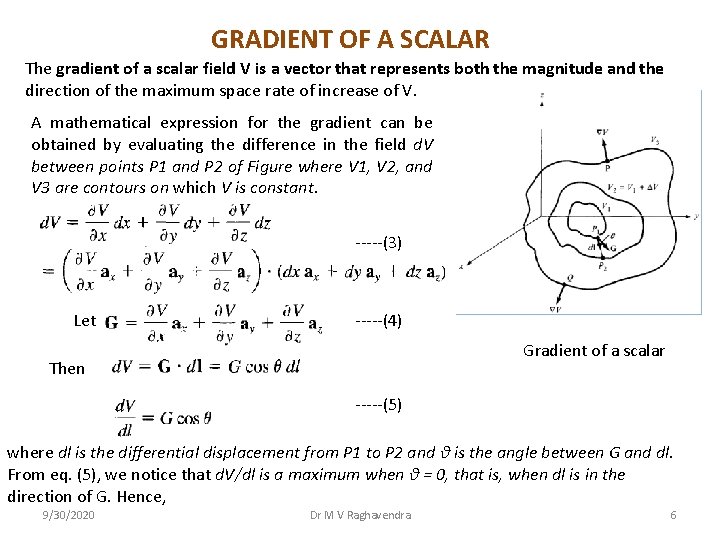

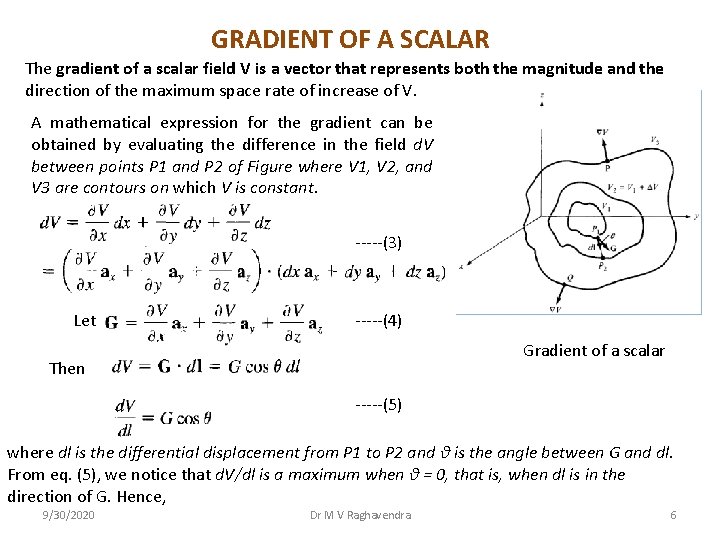

GRADIENT OF A SCALAR The gradient of a scalar field V is a vector that represents both the magnitude and the direction of the maximum space rate of increase of V. A mathematical expression for the gradient can be obtained by evaluating the difference in the field d. V between points P 1 and P 2 of Figure where V 1, V 2, and V 3 are contours on which V is constant. -----(3) Let -----(4) Gradient of a scalar Then -----(5) where dl is the differential displacement from P 1 to P 2 and θ is the angle between G and dl. From eq. (5), we notice that d. V/dl is a maximum when θ = 0, that is, when dl is in the direction of G. Hence, 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 6

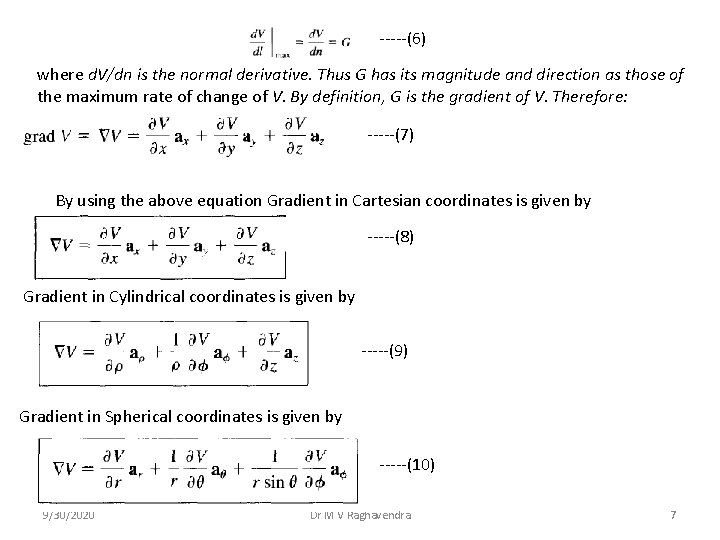

-----(6) where d. V/dn is the normal derivative. Thus G has its magnitude and direction as those of the maximum rate of change of V. By definition, G is the gradient of V. Therefore: -----(7) By using the above equation Gradient in Cartesian coordinates is given by -----(8) Gradient in Cylindrical coordinates is given by -----(9) Gradient in Spherical coordinates is given by -----(10) 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 7

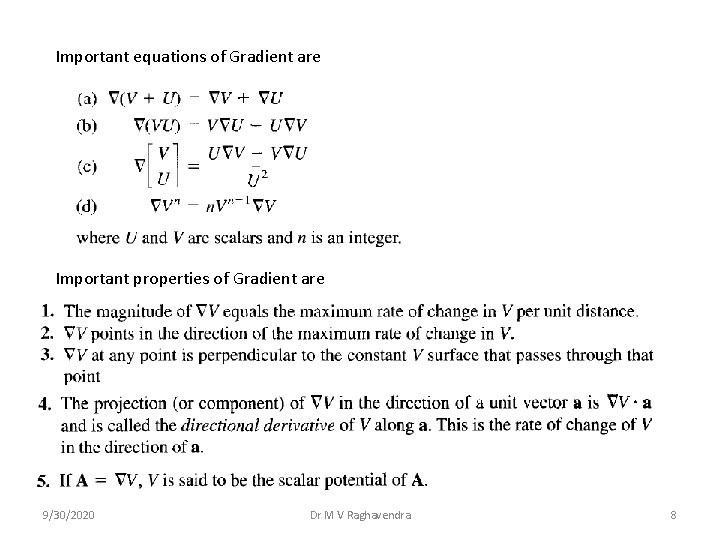

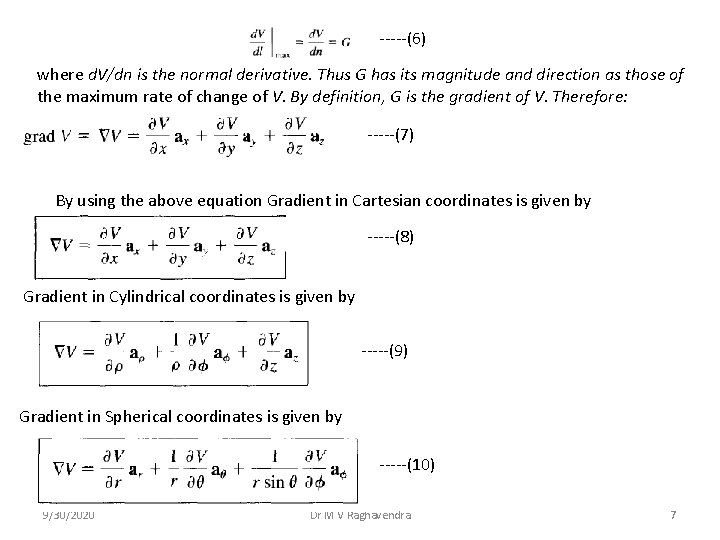

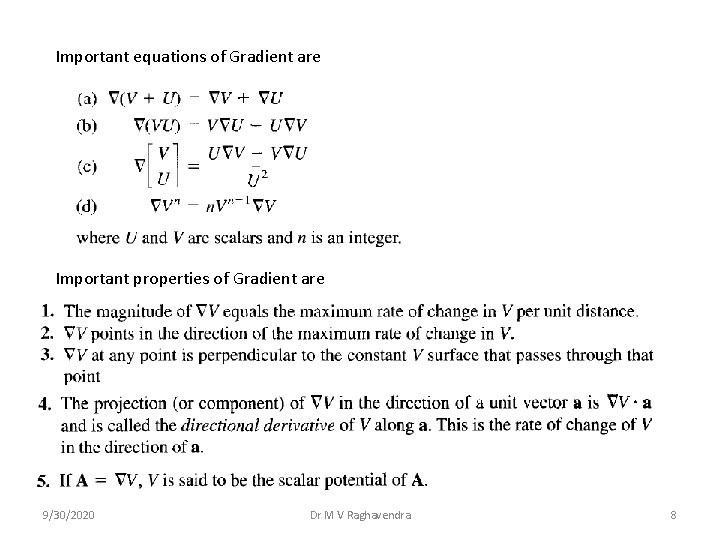

Important equations of Gradient are Important properties of Gradient are 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 8

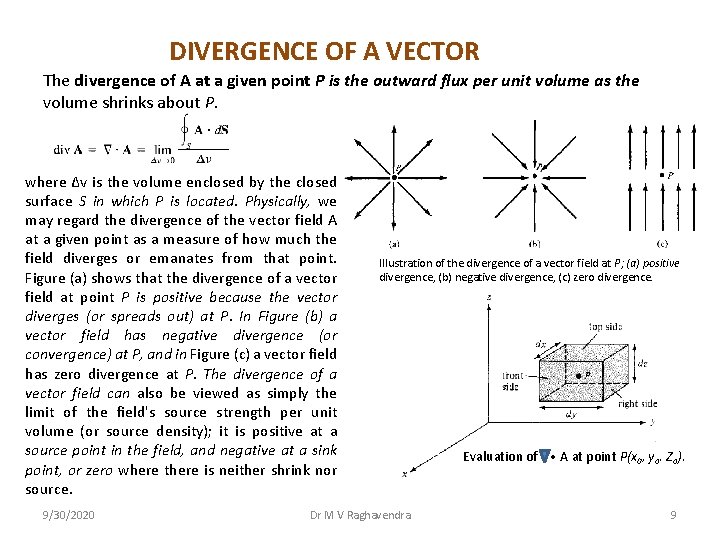

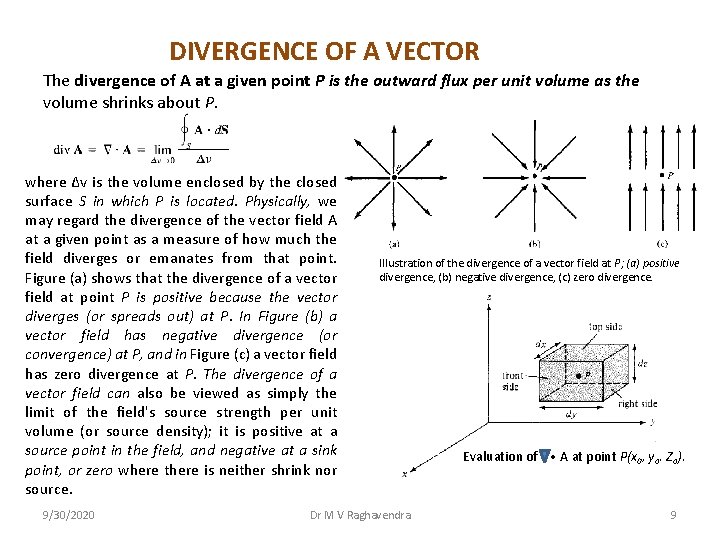

DIVERGENCE OF A VECTOR The divergence of A at a given point P is the outward flux per unit volume as the volume shrinks about P. where ∆v is the volume enclosed by the closed surface S in which P is located. Physically, we may regard the divergence of the vector field A at a given point as a measure of how much the field diverges or emanates from that point. Figure (a) shows that the divergence of a vector field at point P is positive because the vector diverges (or spreads out) at P. In Figure (b) a vector field has negative divergence (or convergence) at P, and in Figure (c) a vector field has zero divergence at P. The divergence of a vector field can also be viewed as simply the limit of the field's source strength per unit volume (or source density); it is positive at a source point in the field, and negative at a sink point, or zero where there is neither shrink nor source. 9/30/2020 Illustration of the divergence of a vector field at P; (a) positive divergence, (b) negative divergence, (c) zero divergence. Dr M V Raghavendra Evaluation of • A at point P(x 0, yo. Zo). 9

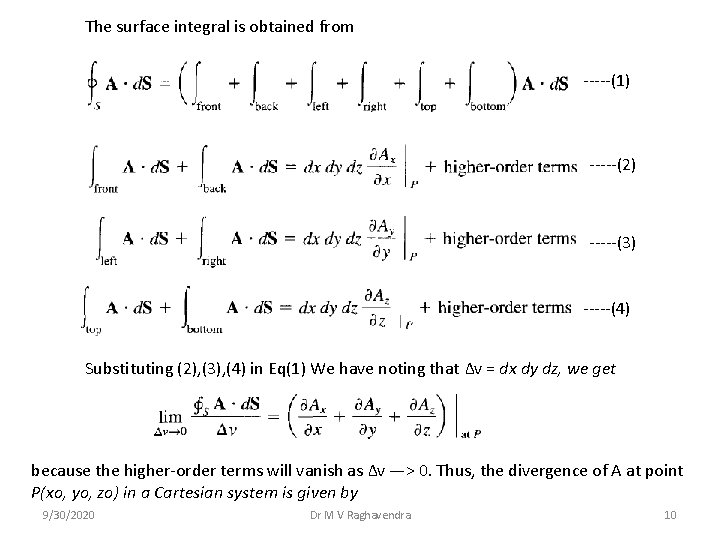

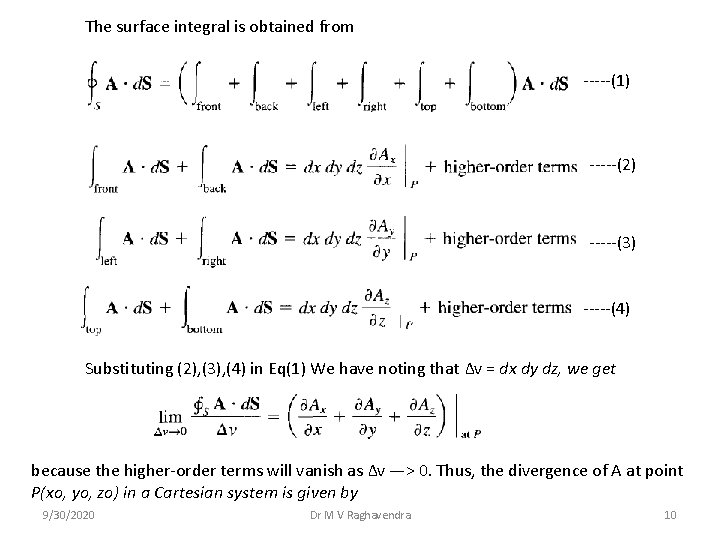

The surface integral is obtained from -----(1) -----(2) -----(3) -----(4) Substituting (2), (3), (4) in Eq(1) We have noting that ∆v = dx dy dz, we get because the higher-order terms will vanish as ∆v —> 0. Thus, the divergence of A at point P(xo, yo, zo) in a Cartesian system is given by 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 10

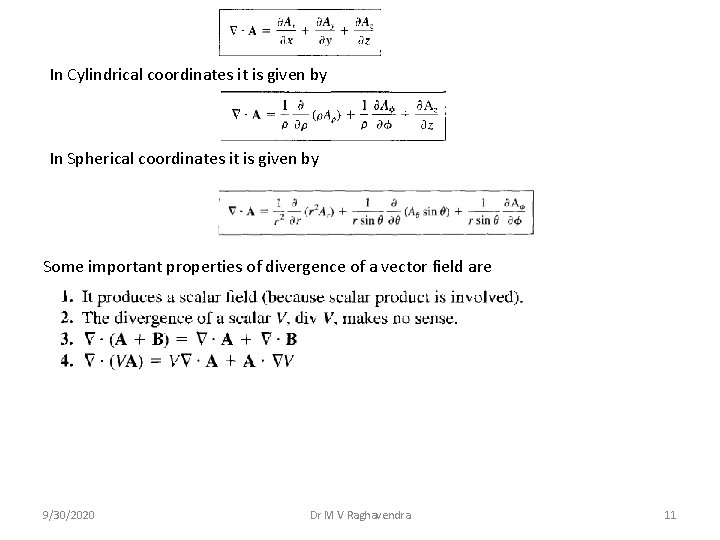

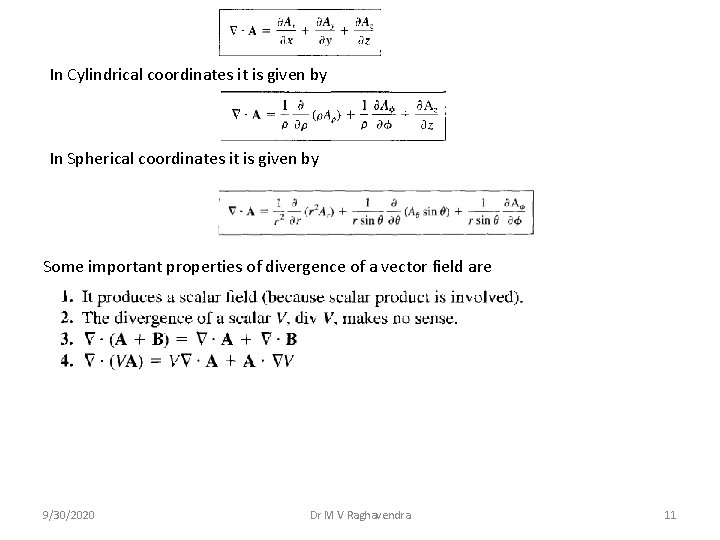

In Cylindrical coordinates it is given by In Spherical coordinates it is given by Some important properties of divergence of a vector field are 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 11

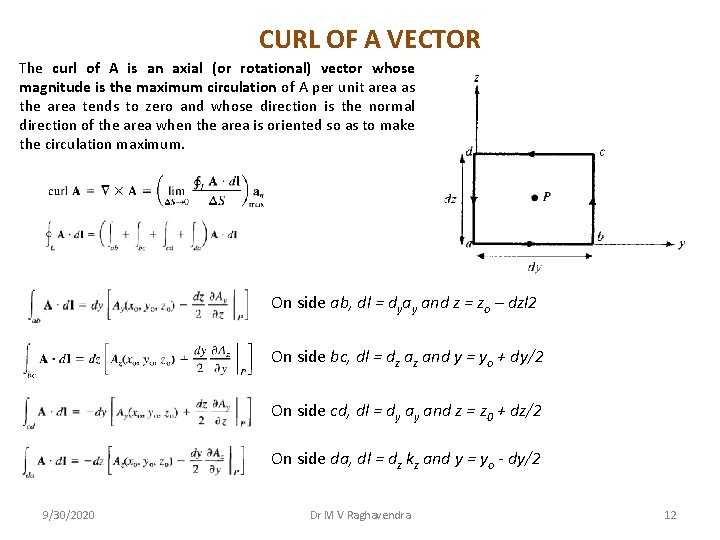

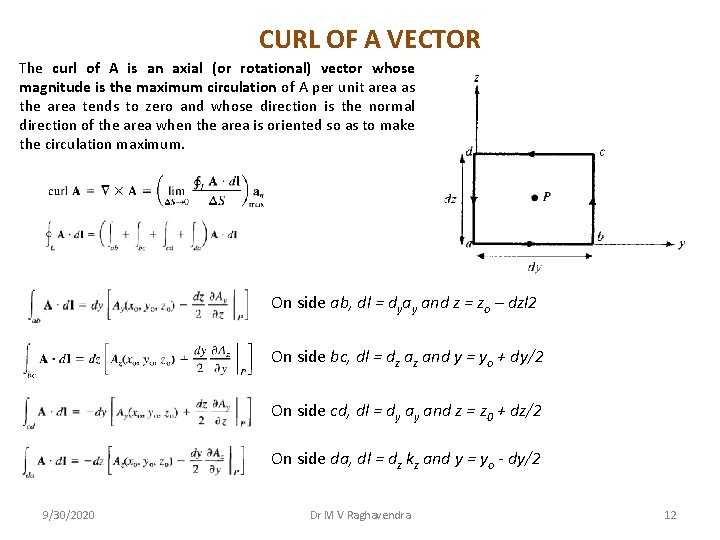

CURL OF A VECTOR The curl of A is an axial (or rotational) vector whose magnitude is the maximum circulation of A per unit area as the area tends to zero and whose direction is the normal direction of the area when the area is oriented so as to make the circulation maximum. On side ab, dl = dyay and z = zo – dzl 2 On side bc, dl = dz az and y = yo + dy/2 On side cd, dl = dy ay and z = z 0 + dz/2 On side da, dl = dz kz and y = yo - dy/2 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 12

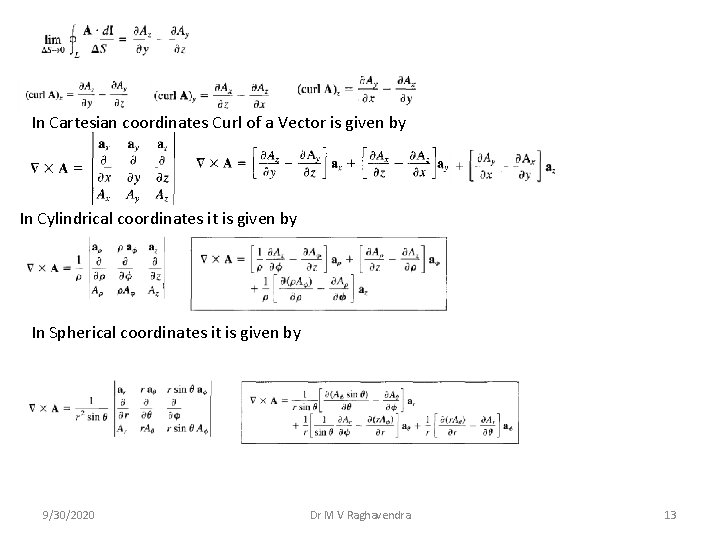

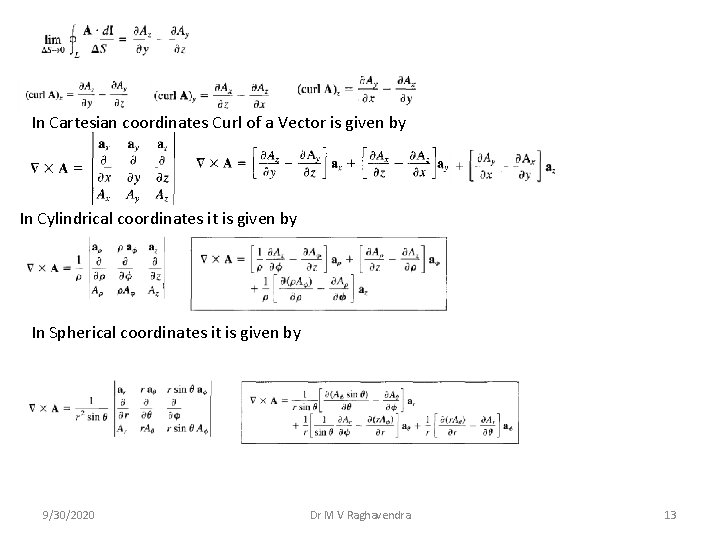

In Cartesian coordinates Curl of a Vector is given by In Cylindrical coordinates it is given by In Spherical coordinates it is given by 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 13

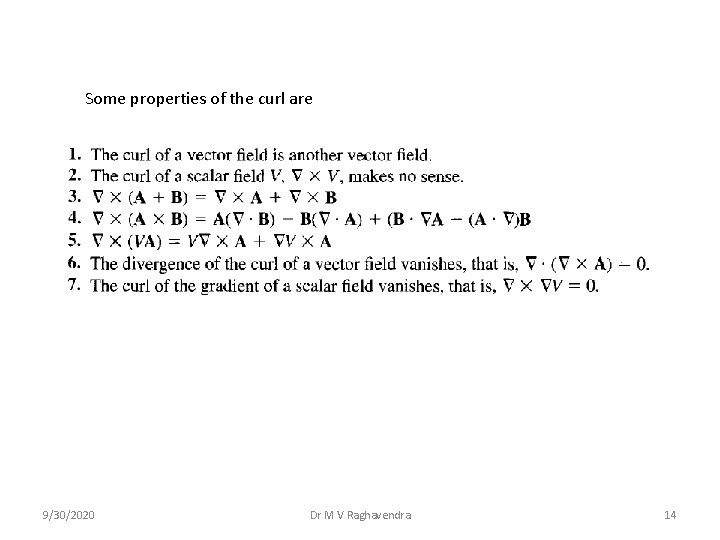

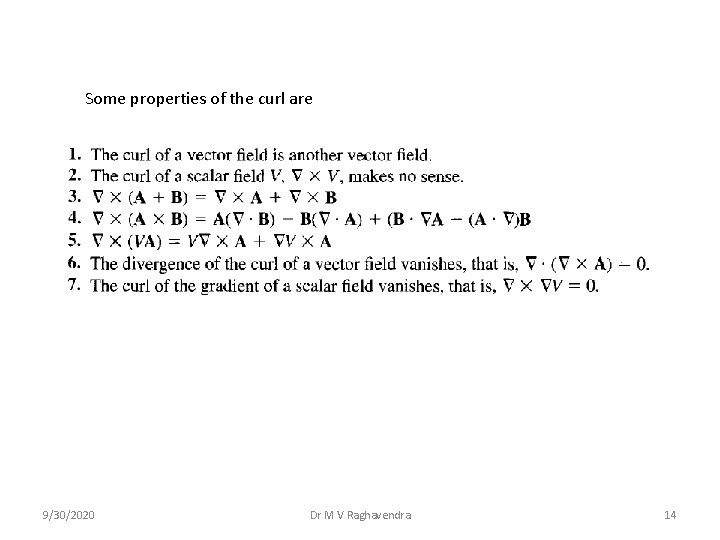

Some properties of the curl are 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 14

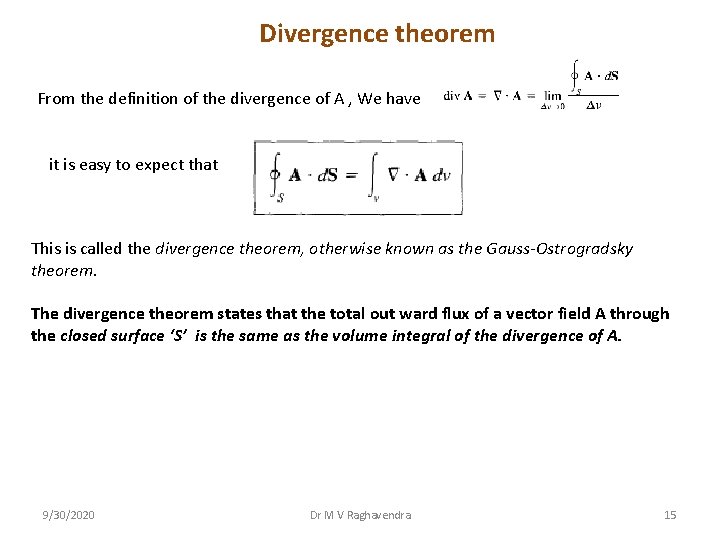

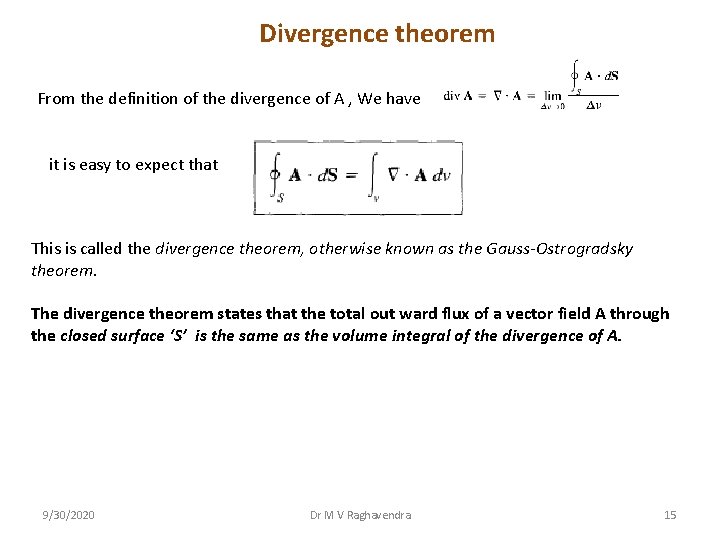

Divergence theorem From the definition of the divergence of A , We have it is easy to expect that This is called the divergence theorem, otherwise known as the Gauss-Ostrogradsky theorem. The divergence theorem states that the total out ward flux of a vector field A through the closed surface ‘S’ is the same as the volume integral of the divergence of A. 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 15

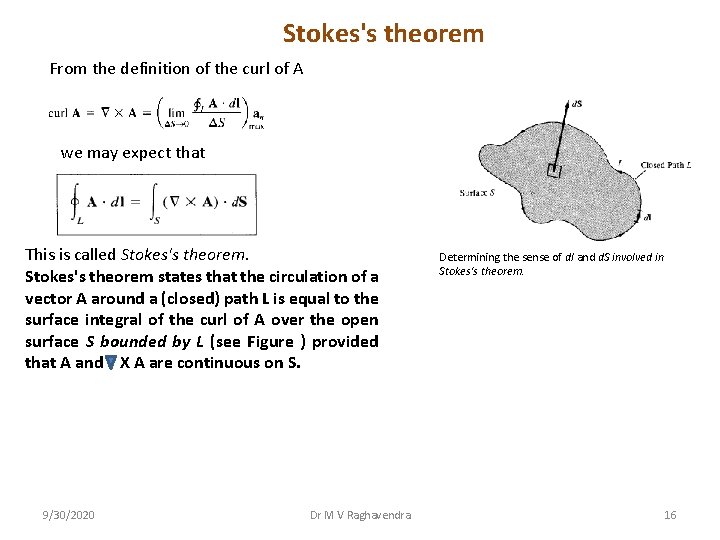

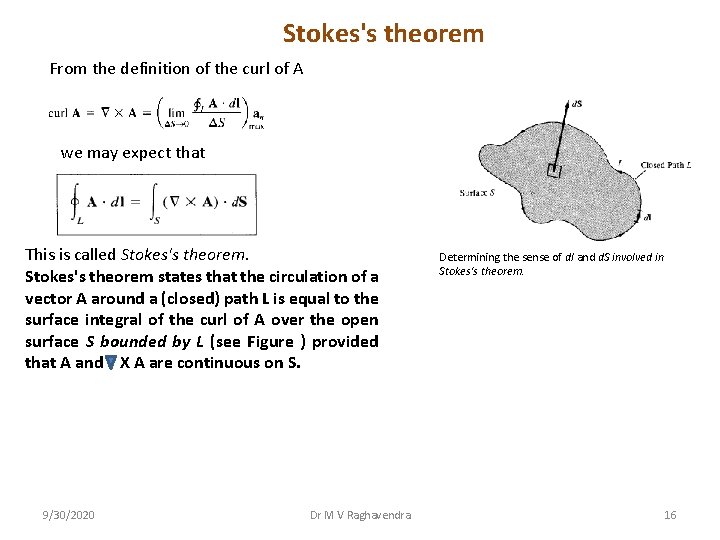

Stokes's theorem From the definition of the curl of A we may expect that This is called Stokes's theorem states that the circulation of a vector A around a (closed) path L is equal to the surface integral of the curl of A over the open surface S bounded by L (see Figure ) provided that A and X A are continuous on S. 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra Determining the sense of dl and d. S involved in Stokes's theorem. 16

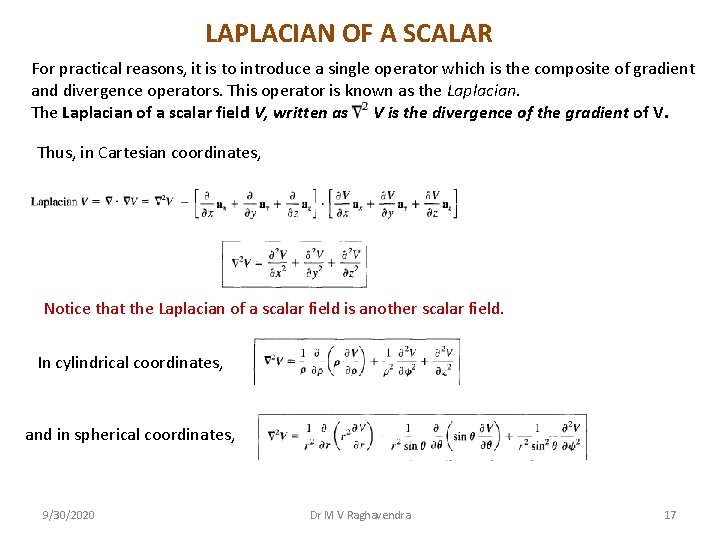

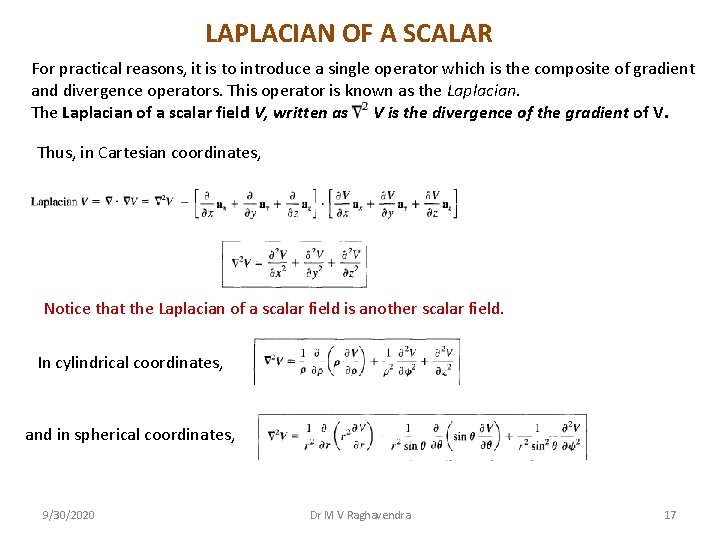

LAPLACIAN OF A SCALAR For practical reasons, it is to introduce a single operator which is the composite of gradient and divergence operators. This operator is known as the Laplacian. The Laplacian of a scalar field V, written as V is the divergence of the gradient of V. Thus, in Cartesian coordinates, Notice that the Laplacian of a scalar field is another scalar field. In cylindrical coordinates, and in spherical coordinates, 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 17

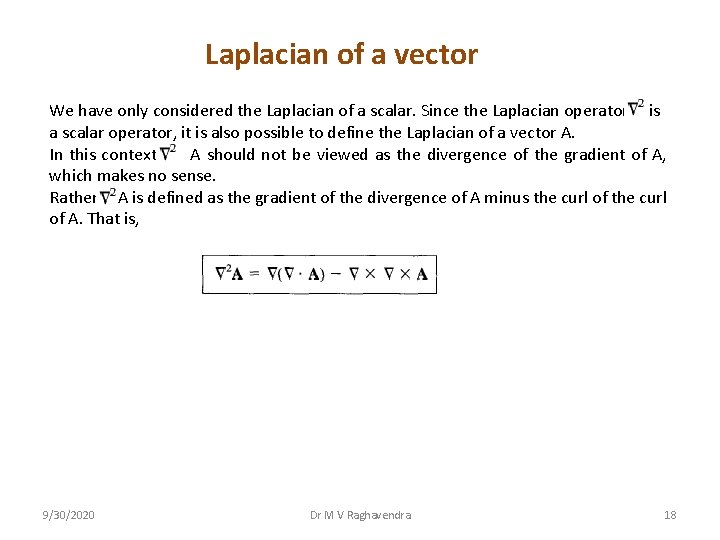

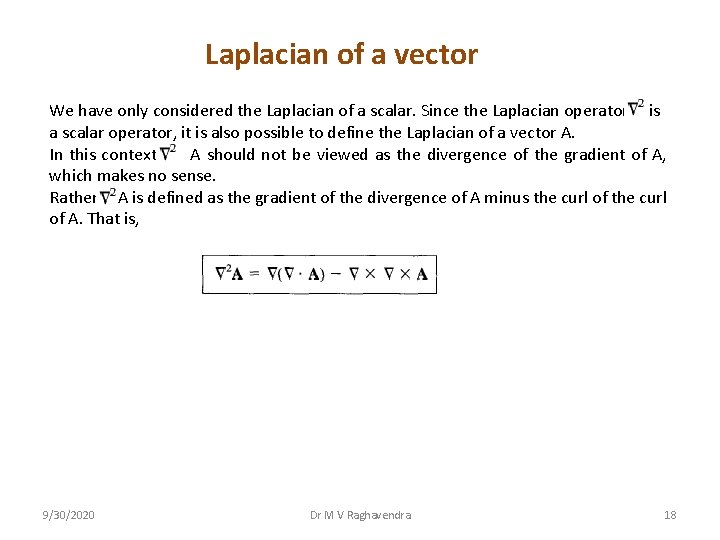

Laplacian of a vector We have only considered the Laplacian of a scalar. Since the Laplacian operator is a scalar operator, it is also possible to define the Laplacian of a vector A. In this context, A should not be viewed as the divergence of the gradient of A, which makes no sense. Rather, A is defined as the gradient of the divergence of A minus the curl of A. That is, 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 18

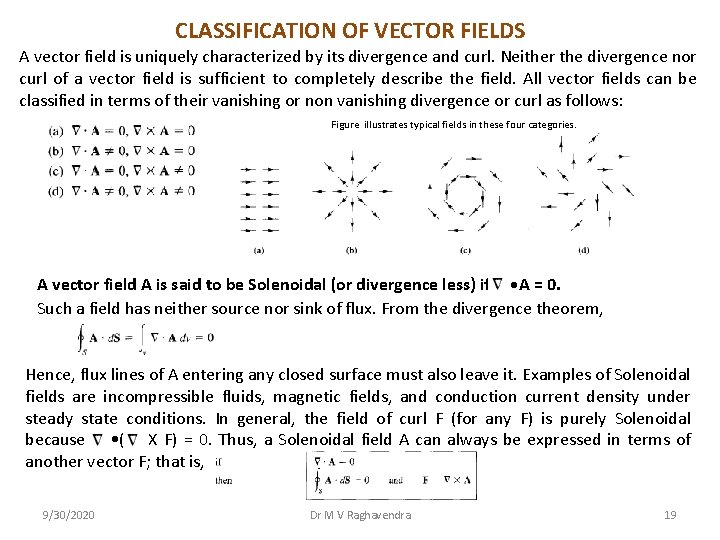

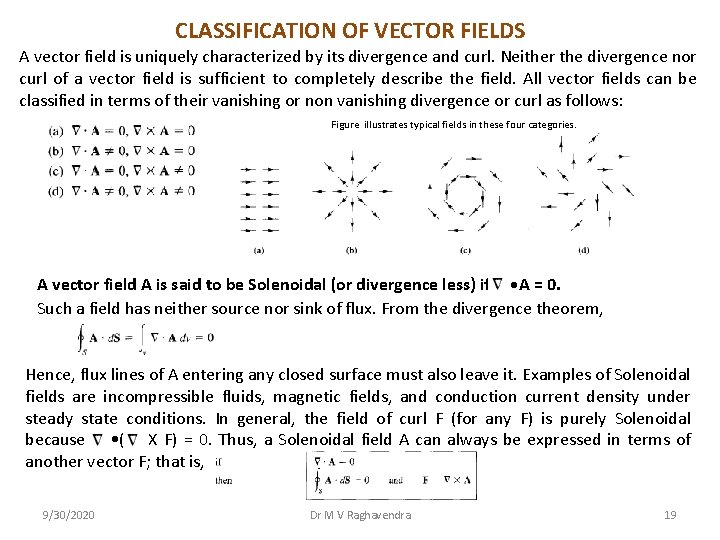

CLASSIFICATION OF VECTOR FIELDS A vector field is uniquely characterized by its divergence and curl. Neither the divergence nor curl of a vector field is sufficient to completely describe the field. All vector fields can be classified in terms of their vanishing or non vanishing divergence or curl as follows: Figure illustrates typical fields in these four categories. A vector field A is said to be Solenoidal (or divergence less) if • A = 0. Such a field has neither source nor sink of flux. From the divergence theorem, Hence, flux lines of A entering any closed surface must also leave it. Examples of Solenoidal fields are incompressible fluids, magnetic fields, and conduction current density under steady state conditions. In general, the field of curl F (for any F) is purely Solenoidal because • ( X F) = 0. Thus, a Solenoidal field A can always be expressed in terms of another vector F; that is, 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 19

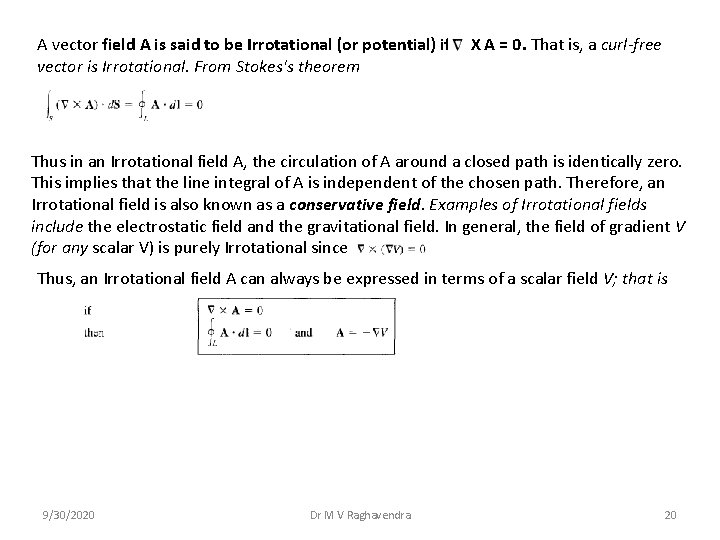

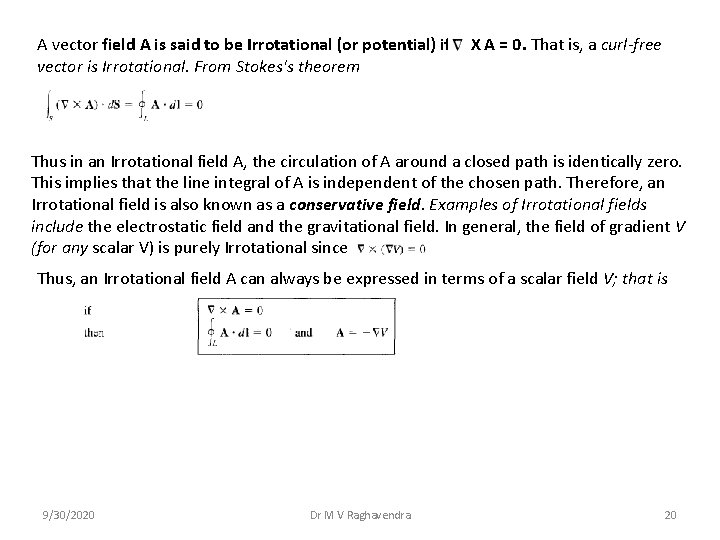

A vector field A is said to be Irrotational (or potential) if vector is Irrotational. From Stokes's theorem X A = 0. That is, a curl-free Thus in an Irrotational field A, the circulation of A around a closed path is identically zero. This implies that the line integral of A is independent of the chosen path. Therefore, an Irrotational field is also known as a conservative field. Examples of Irrotational fields include the electrostatic field and the gravitational field. In general, the field of gradient V (for any scalar V) is purely Irrotational since Thus, an Irrotational field A can always be expressed in terms of a scalar field V; that is 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 20

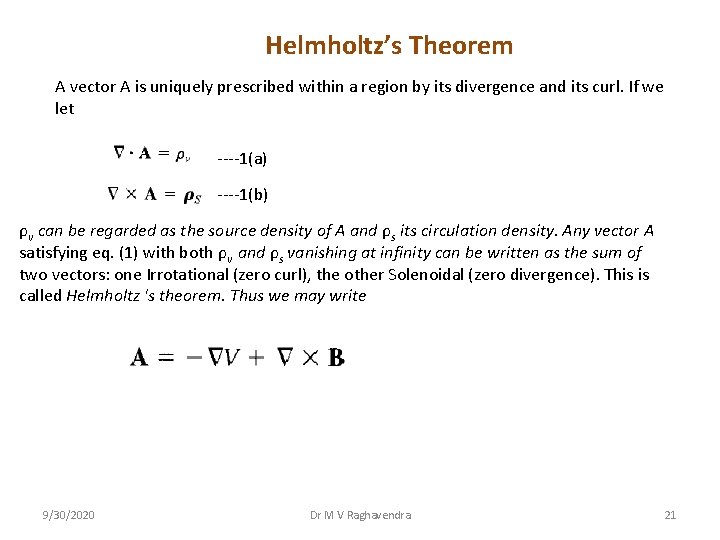

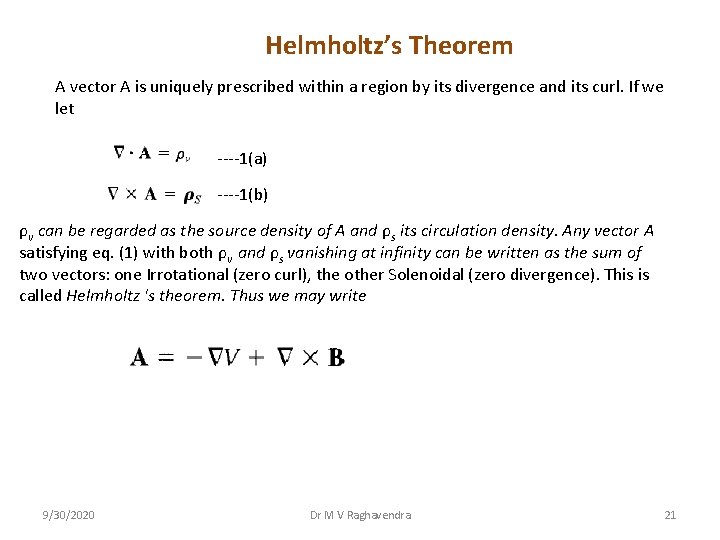

Helmholtz’s Theorem A vector A is uniquely prescribed within a region by its divergence and its curl. If we let ----1(a) ----1(b) ρv can be regarded as the source density of A and ρs its circulation density. Any vector A satisfying eq. (1) with both ρv and ρs vanishing at infinity can be written as the sum of two vectors: one Irrotational (zero curl), the other Solenoidal (zero divergence). This is called Helmholtz 's theorem. Thus we may write 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 21

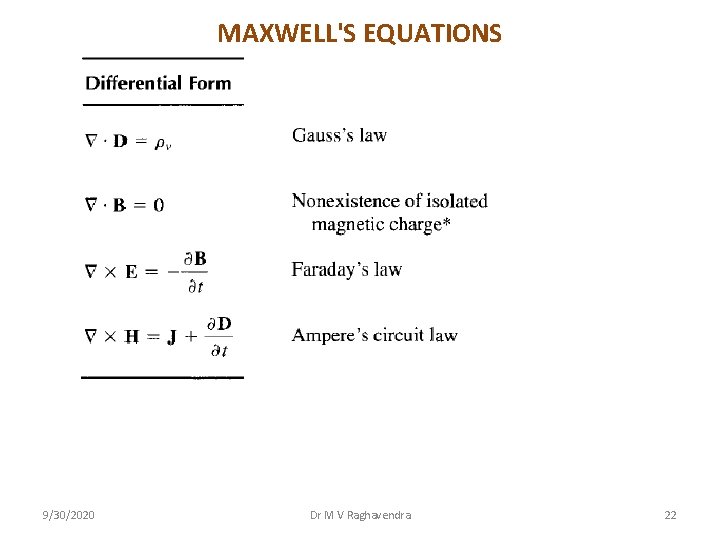

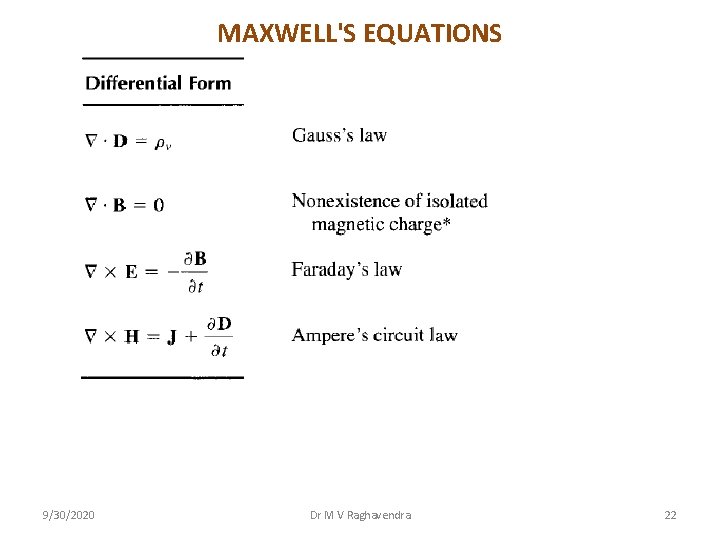

MAXWELL'S EQUATIONS 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 22

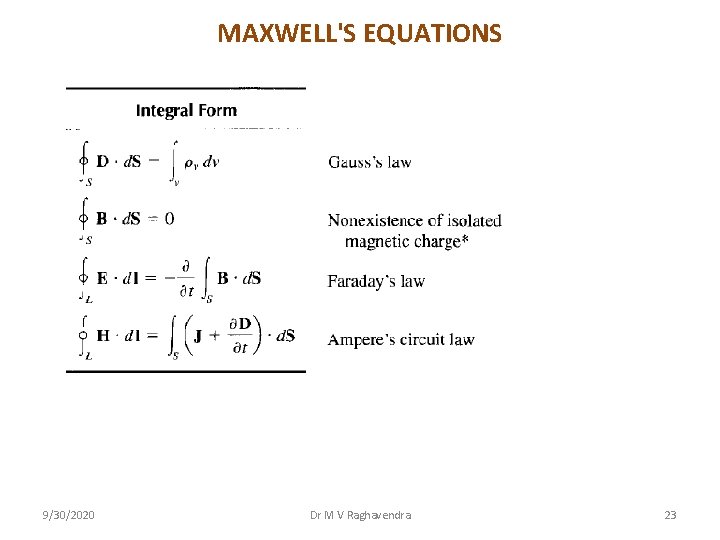

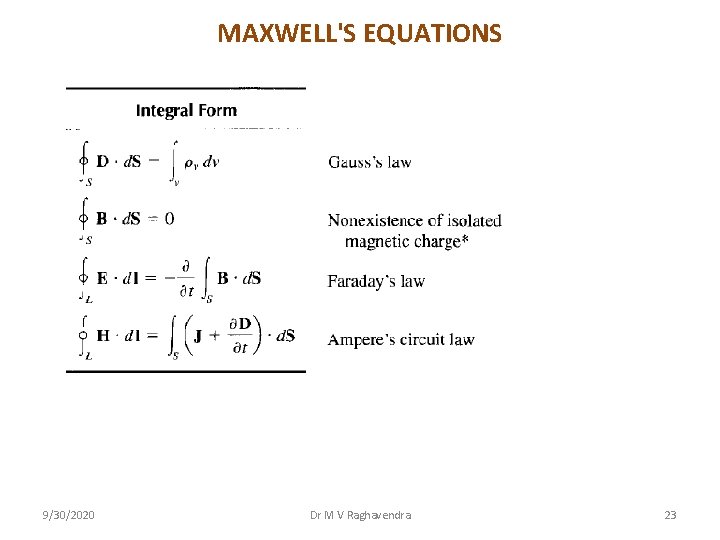

MAXWELL'S EQUATIONS 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 23

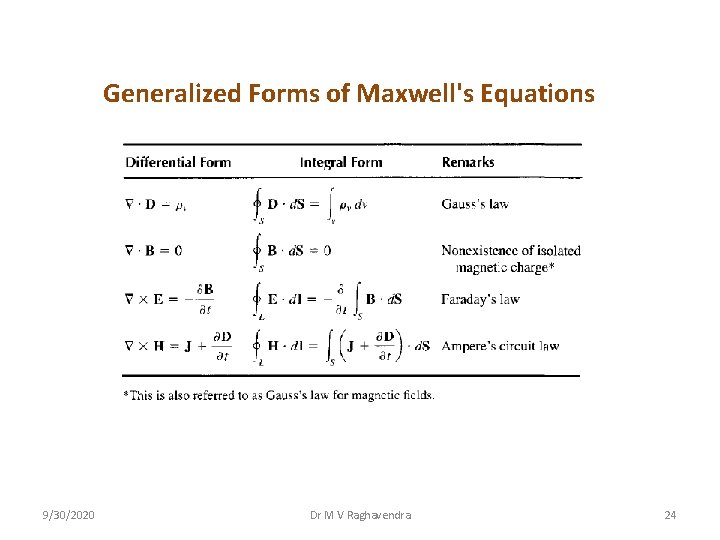

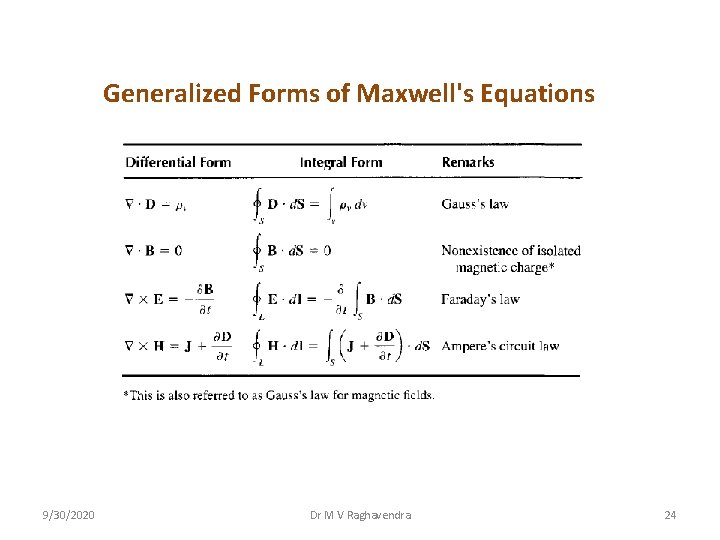

Generalized Forms of Maxwell's Equations 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 24

ELECTRIC BOUNDARY CONDITIONS we have considered the existence of the electric field in a homogeneous medium. If the field exists in a region consisting of two different media, the conditions that the field must satisfy at the interface separating the media are called boundary conditions. These conditions are helpful in determining the field on one side of the boundary if the field on the other side is known. Obviously, the conditions will be dictated by the types of material the media are made of. We shall consider the boundary conditions at an interface separating Ø Dielectric (εr 1) and dielectric (εr 2) Ø Conductor and dielectric Ø Conductor and free space To determine the boundary conditions, we need to use Maxwell's equations: -----(1) ------(2) Also we need to decompose the electric field intensity E into two orthogonal components: E = Et + En ------(3) where Et and En are, respectively, the tangential and normal components of E to the interface of interest. A similar decomposition can be done for the electric flux density D. 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 25

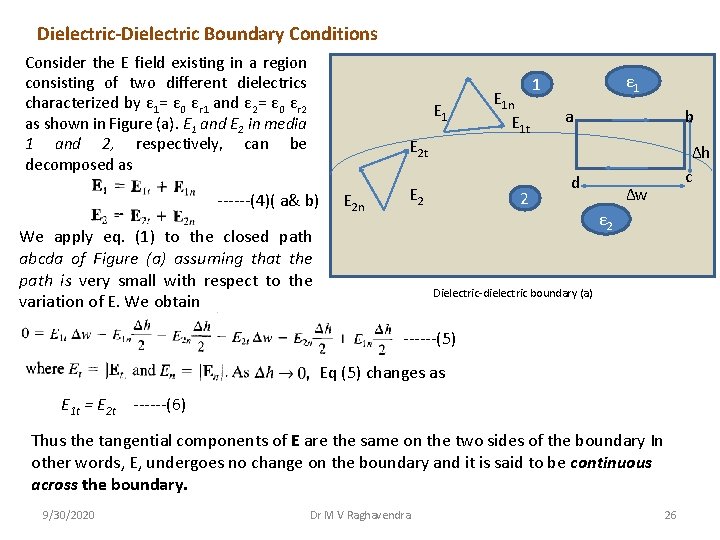

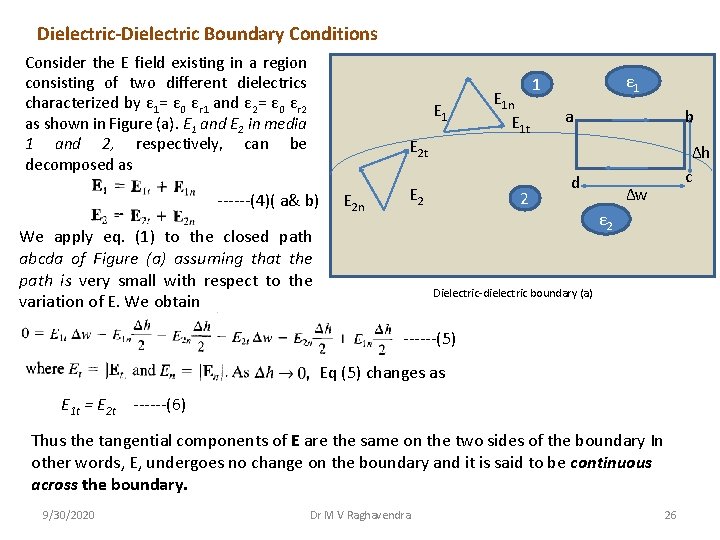

Dielectric-Dielectric Boundary Conditions Consider the E field existing in a region consisting of two different dielectrics characterized by ε 1= ε 0 εr 1 and ε 2= ε 0 εr 2 as shown in Figure (a). E 1 and E 2 in media 1 and 2, respectively, can be decomposed as E 1 E 2 t ------(4)( a& b) E 2 n E 2 We apply eq. (1) to the closed path abcda of Figure (a) assuming that the path is very small with respect to the variation of E. We obtain E 1 t 2 ε 1 1 a b d ∆h c ∆w ε 2 Dielectric-dielectric boundary (a) ------(5) Eq (5) changes as E 1 t = E 2 t ------(6) Thus the tangential components of E are the same on the two sides of the boundary In other words, E, undergoes no change on the boundary and it is said to be continuous across the boundary. 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 26

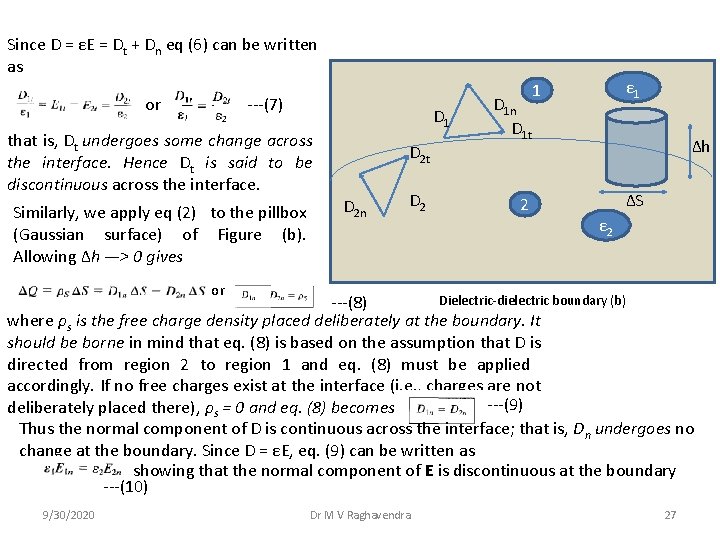

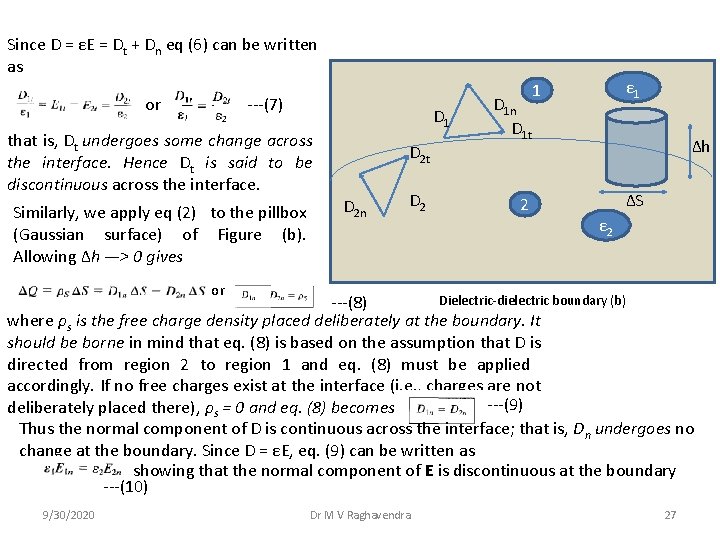

Since D = εE = Dt + Dn eq (6) can be written as or ---(7) D 1 that is, Dt undergoes some change across the interface. Hence Dt is said to be discontinuous across the interface. Similarly, we apply eq (2) to the pillbox (Gaussian surface) of Figure (b). Allowing ∆h —> 0 gives D 2 t D 2 n D 2 D 1 n D 1 t 2 ε 1 1 ∆h ∆S ε 2 or Dielectric-dielectric boundary (b) ---(8) where ρs is the free charge density placed deliberately at the boundary. It should be borne in mind that eq. (8) is based on the assumption that D is directed from region 2 to region 1 and eq. (8) must be applied accordingly. If no free charges exist at the interface (i. e. , charges are not ---(9) deliberately placed there), ρs = 0 and eq. (8) becomes Thus the normal component of D is continuous across the interface; that is, Dn undergoes no change at the boundary. Since D = εE, eq. (9) can be written as showing that the normal component of E is discontinuous at the boundary ---(10) 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 27

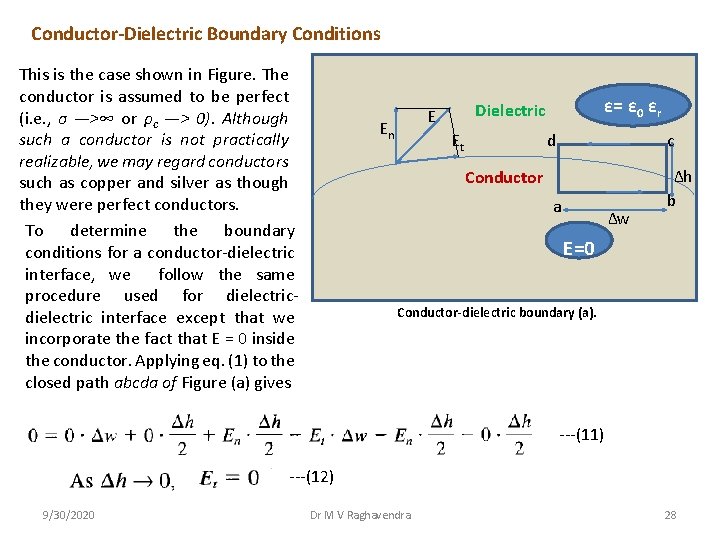

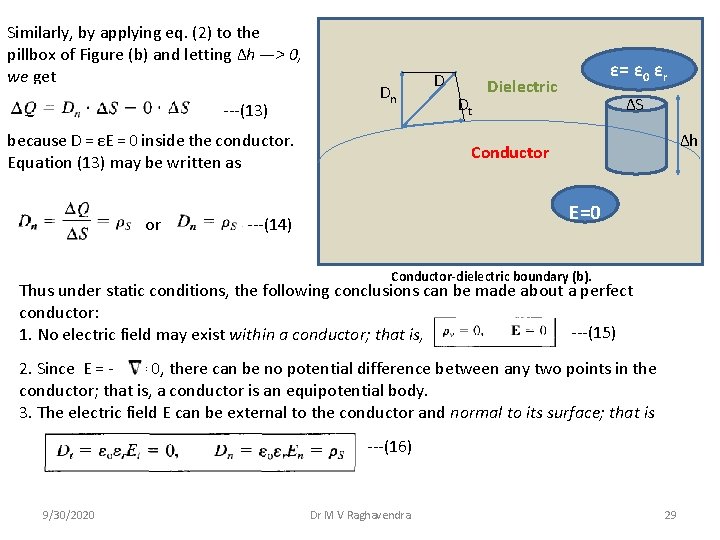

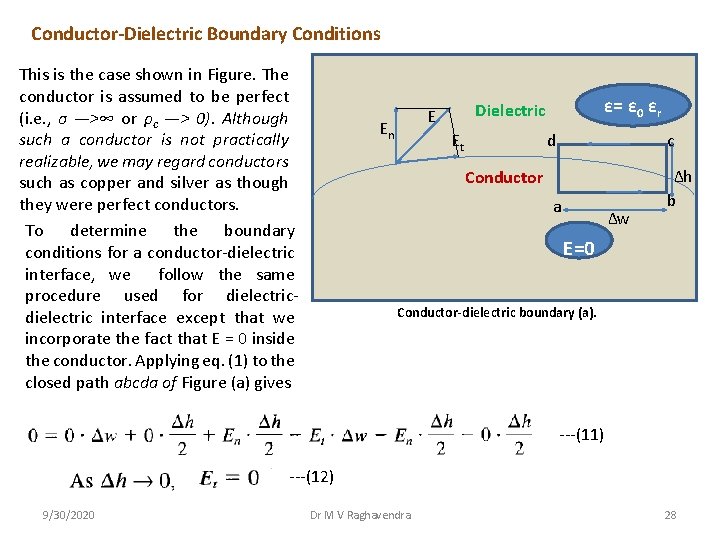

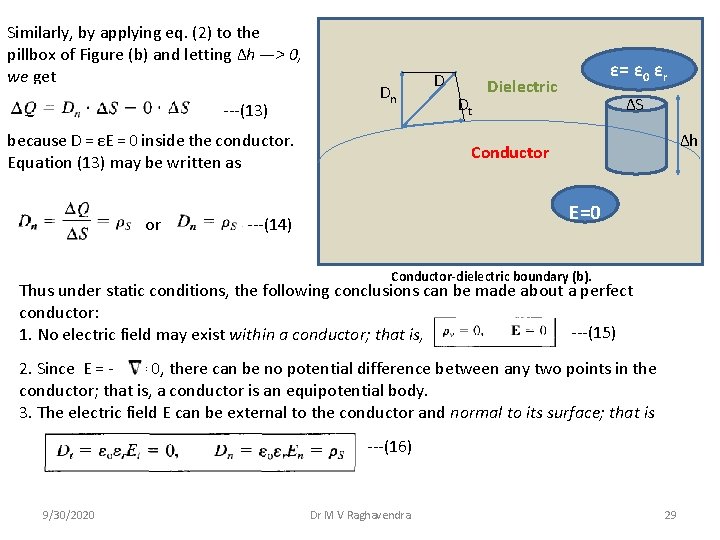

Conductor-Dielectric Boundary Conditions This is the case shown in Figure. The conductor is assumed to be perfect (i. e. , σ —>∞ or ρc —> 0). Although such a conductor is not practically realizable, we may regard conductors such as copper and silver as though they were perfect conductors. To determine the boundary conditions for a conductor-dielectric interface, we follow the same procedure used for dielectric interface except that we incorporate the fact that E = 0 inside the conductor. Applying eq. (1) to the closed path abcda of Figure (a) gives En ε= ε 0 εr Dielectric E Et d c Conductor a ∆w ∆h b E=0 Conductor-dielectric boundary (a). ---(11) ---(12) 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 28

Similarly, by applying eq. (2) to the pillbox of Figure (b) and letting ∆h —> 0, we get ---(13) Dn because D = εE = 0 inside the conductor. Equation (13) may be written as or D Dt ε= ε 0 εr Dielectric ∆S ∆h Conductor E=0 ---(14) Conductor-dielectric boundary (b). Thus under static conditions, the following conclusions can be made about a perfect conductor: ---(15) 1. No electric field may exist within a conductor; that is, 2. Since E = - V= 0, there can be no potential difference between any two points in the conductor; that is, a conductor is an equipotential body. 3. The electric field E can be external to the conductor and normal to its surface; that is ---(16) 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 29

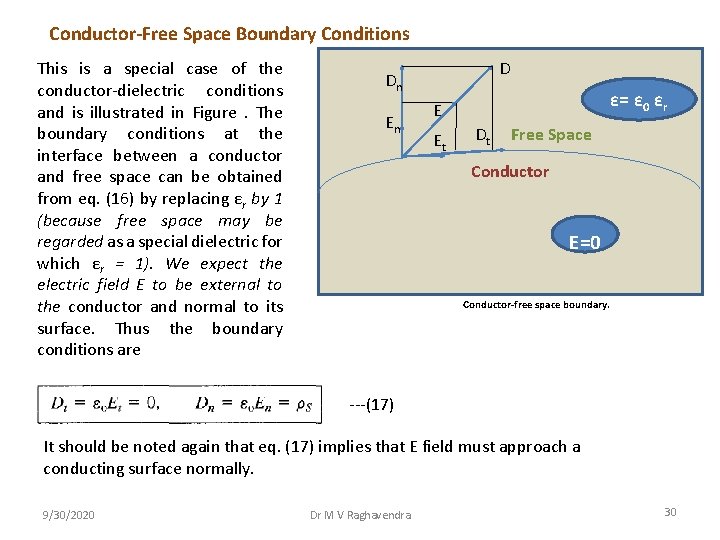

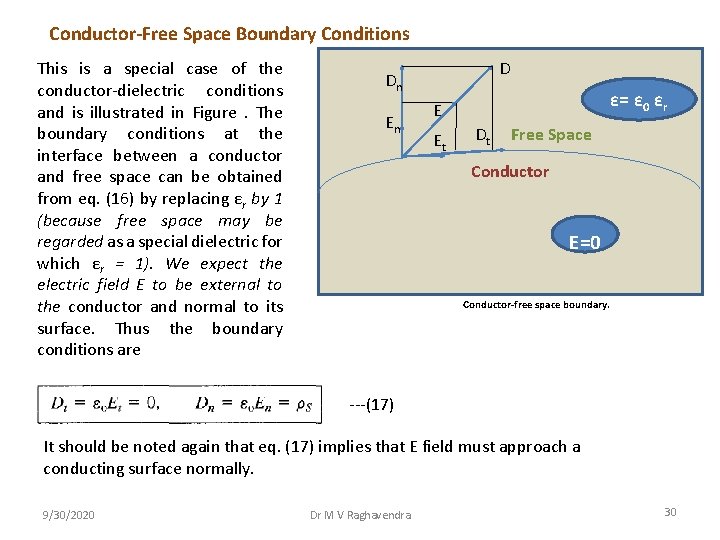

Conductor-Free Space Boundary Conditions This is a special case of the conductor-dielectric conditions and is illustrated in Figure. The boundary conditions at the interface between a conductor and free space can be obtained from eq. (16) by replacing εr by 1 (because free space may be regarded as a special dielectric for which εr = 1). We expect the electric field E to be external to the conductor and normal to its surface. Thus the boundary conditions are D Dn En ε= ε 0 εr E Et Dt Free Space Conductor E=0 Conductor-free space boundary. ---(17) It should be noted again that eq. (17) implies that E field must approach a conducting surface normally. 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 30

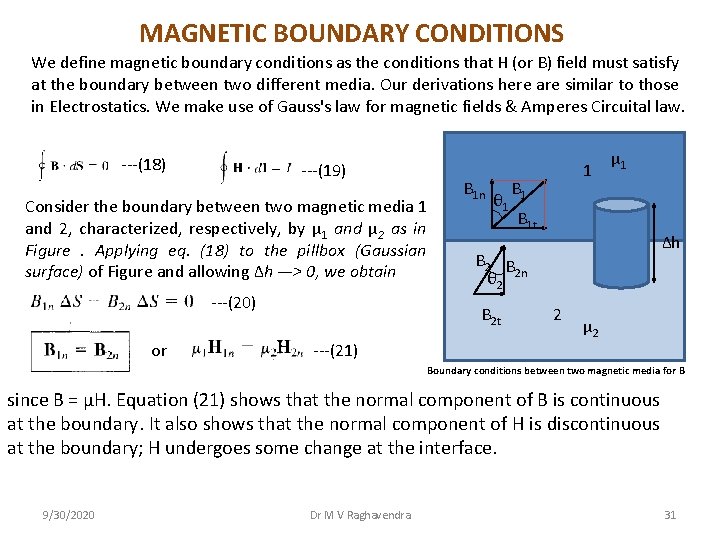

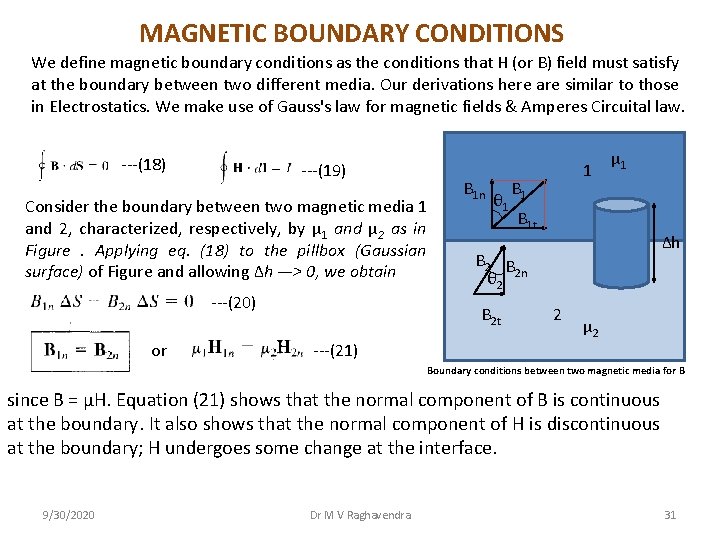

MAGNETIC BOUNDARY CONDITIONS We define magnetic boundary conditions as the conditions that H (or B) field must satisfy at the boundary between two different media. Our derivations here are similar to those in Electrostatics. We make use of Gauss's law for magnetic fields & Amperes Circuital law. ---(18) ---(19) Consider the boundary between two magnetic media 1 and 2, characterized, respectively, by μ 1 and μ 2 as in Figure. Applying eq. (18) to the pillbox (Gaussian surface) of Figure and allowing ∆h —> 0, we obtain ---(20) or B 1 n θ 1 B 1 μ 1 B 1 t ∆h B 2 B θ 2 2 n B 2 t ---(21) 1 2 μ 2 Boundary conditions between two magnetic media for B since B = μH. Equation (21) shows that the normal component of B is continuous at the boundary. It also shows that the normal component of H is discontinuous at the boundary; H undergoes some change at the interface. 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 31

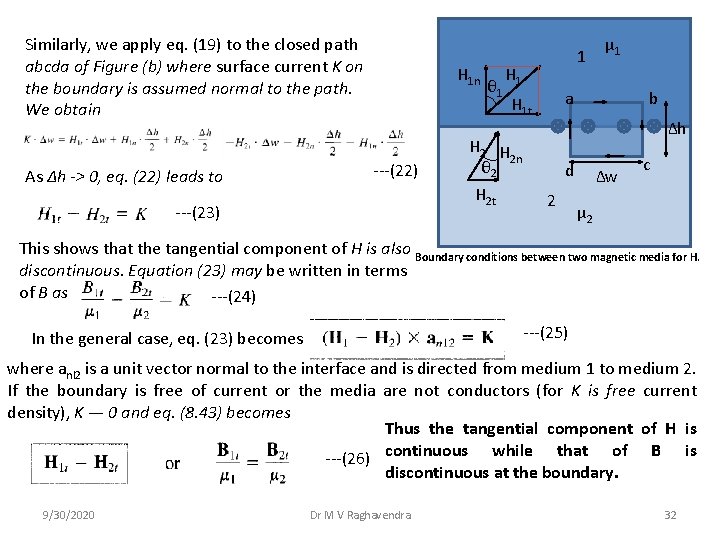

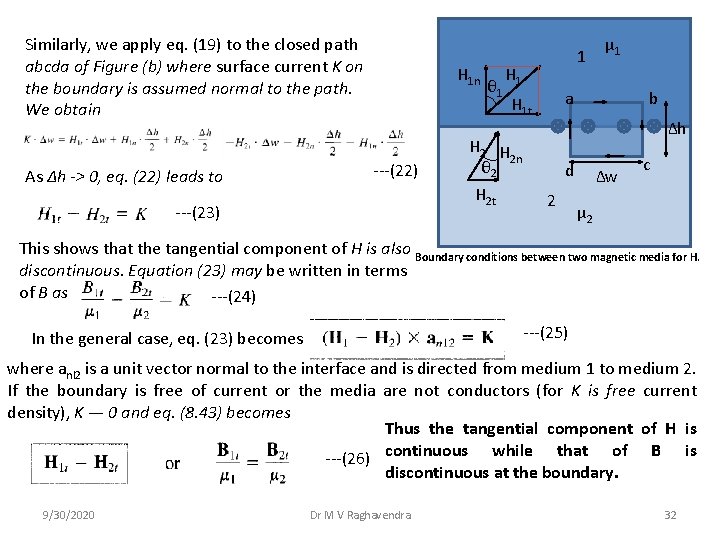

Similarly, we apply eq. (19) to the closed path abcda of Figure (b) where surface current K on the boundary is assumed normal to the path. We obtain As ∆h -> 0, eq. (22) leads to H 1 n ---(22) θ 1 H 1 μ 1 a H 1 t b ∆h H 2 n θ 2 H 2 t ---(23) 1 d 2 ∆w c μ 2 This shows that the tangential component of H is also Boundary conditions between two magnetic media for H. discontinuous. Equation (23) may be written in terms of B as ---(24) ---(25) In the general case, eq. (23) becomes where anl 2 is a unit vector normal to the interface and is directed from medium 1 to medium 2. If the boundary is free of current or the media are not conductors (for K is free current density), K — 0 and eq. (8. 43) becomes Thus the tangential component of H is ---(26) continuous while that of B is discontinuous at the boundary. 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 32

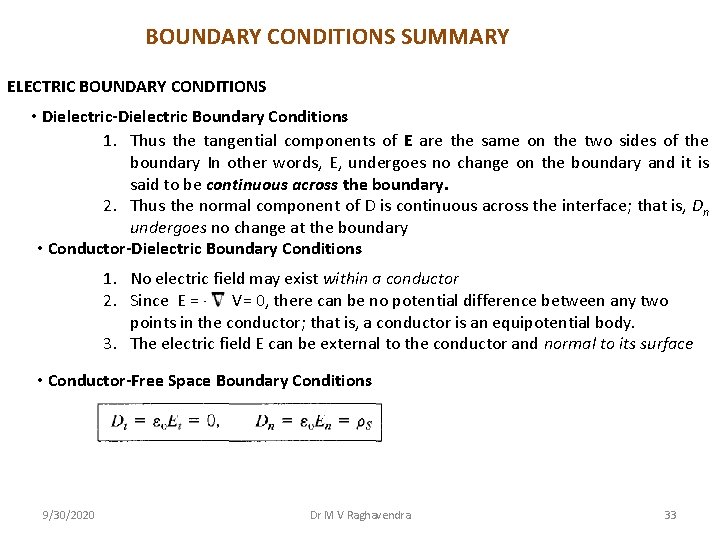

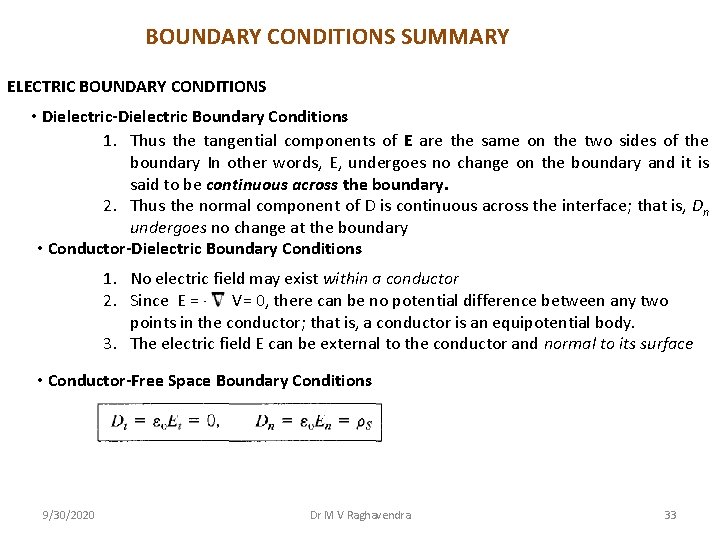

BOUNDARY CONDITIONS SUMMARY ELECTRIC BOUNDARY CONDITIONS • Dielectric-Dielectric Boundary Conditions 1. Thus the tangential components of E are the same on the two sides of the boundary In other words, E, undergoes no change on the boundary and it is said to be continuous across the boundary. 2. Thus the normal component of D is continuous across the interface; that is, Dn undergoes no change at the boundary • Conductor-Dielectric Boundary Conditions 1. No electric field may exist within a conductor 2. Since E = - V= 0, there can be no potential difference between any two points in the conductor; that is, a conductor is an equipotential body. 3. The electric field E can be external to the conductor and normal to its surface • Conductor-Free Space Boundary Conditions 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 33

MAGNETIC BOUNDARY CONDITIONS FOR B 1. the normal component of B is continuous at the boundary. 2. the normal component of H is discontinuous at the boundary. MAGNETIC BOUNDARY CONDITIONS FOR H 1. tangential component of H is continuous at the boundary. 2. the Tangential component of B is discontinuous at the boundary. 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 34

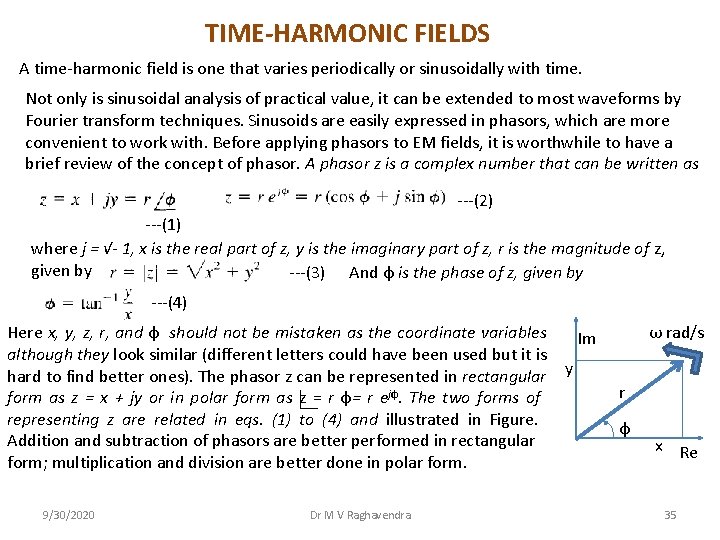

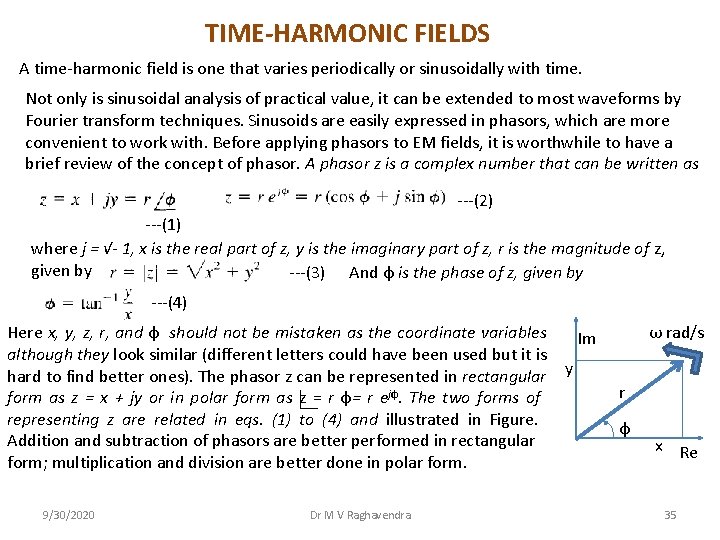

TIME-HARMONIC FIELDS A time-harmonic field is one that varies periodically or sinusoidally with time. Not only is sinusoidal analysis of practical value, it can be extended to most waveforms by Fourier transform techniques. Sinusoids are easily expressed in phasors, which are more convenient to work with. Before applying phasors to EM fields, it is worthwhile to have a brief review of the concept of phasor. A phasor z is a complex number that can be written as ---(2) ---(1) where j = √- 1, x is the real part of z, y is the imaginary part of z, r is the magnitude of z, given by ---(3) And ф is the phase of z, given by ---(4) Here x, y, z, r, and ф should not be mistaken as the coordinate variables although they look similar (different letters could have been used but it is hard to find better ones). The phasor z can be represented in rectangular form as z = x + jy or in polar form as z = r ф= r ejф. The two forms of representing z are related in eqs. (1) to (4) and illustrated in Figure. Addition and subtraction of phasors are better performed in rectangular form; multiplication and division are better done in polar form. 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra ω rad/s Im y r ф x Re 35

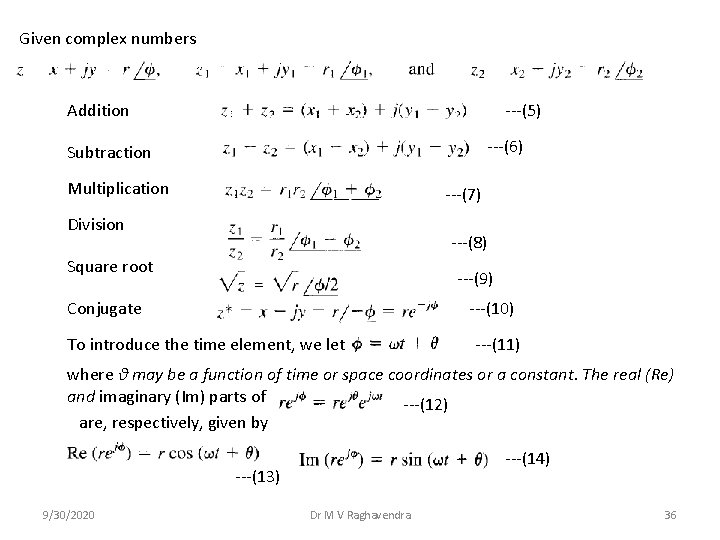

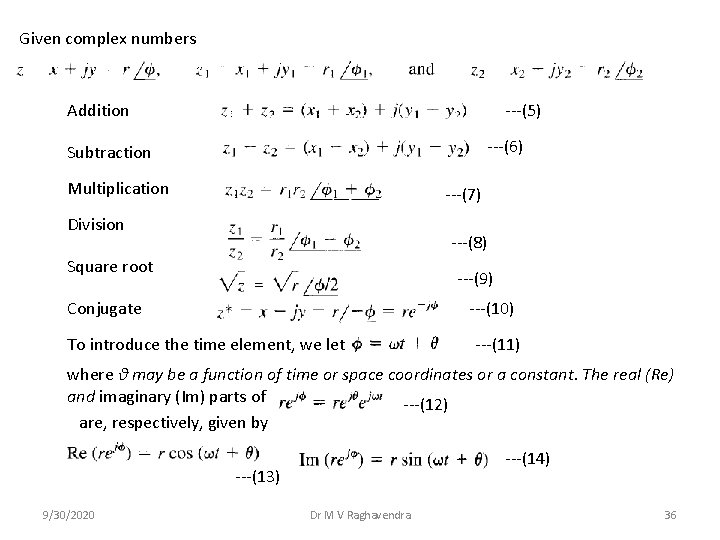

Given complex numbers Addition ---(5) ---(6) Subtraction Multiplication ---(7) Division ---(8) Square root ---(9) Conjugate ---(10) To introduce the time element, we let ---(11) where θ may be a function of time or space coordinates or a constant. The real (Re) and imaginary (Im) parts of ---(12) are, respectively, given by ---(14) ---(13) 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 36

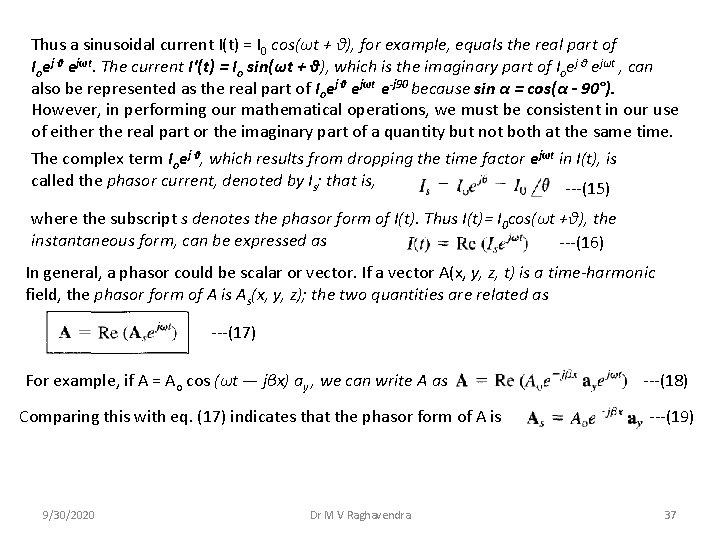

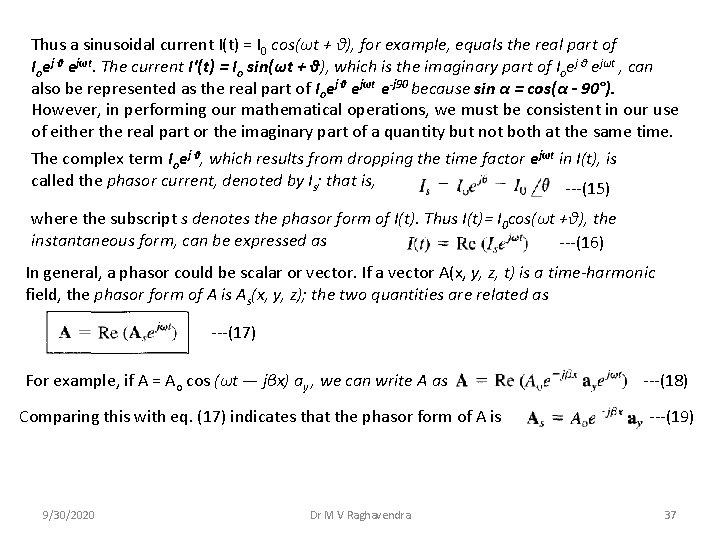

Thus a sinusoidal current I(t) = I 0 cos(ωt + θ), for example, equals the real part of Ioej θ ejωt. The current I'(t) = Io sin(ωt + θ), which is the imaginary part of Ioej θ ejωt , can also be represented as the real part of Ioej θ ejωt e-j 90 because sin α = cos(α - 90°). However, in performing our mathematical operations, we must be consistent in our use of either the real part or the imaginary part of a quantity but not both at the same time. The complex term Ioej θ, which results from dropping the time factor ejωt in I(t), is called the phasor current, denoted by Is; that is, ---(15) where the subscript s denotes the phasor form of I(t). Thus I(t)= I 0 cos(ωt +θ), the instantaneous form, can be expressed as ---(16) In general, a phasor could be scalar or vector. If a vector A(x, y, z, t) is a time-harmonic field, the phasor form of A is As(x, y, z); the two quantities are related as ---(17) For example, if A = Ao cos (ωt — jβx) ay , we can write A as Comparing this with eq. (17) indicates that the phasor form of A is 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra ---(18) ---(19) 37

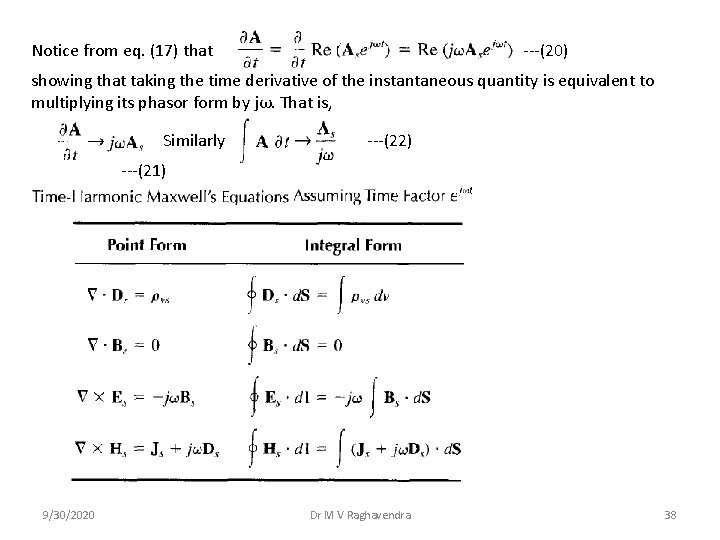

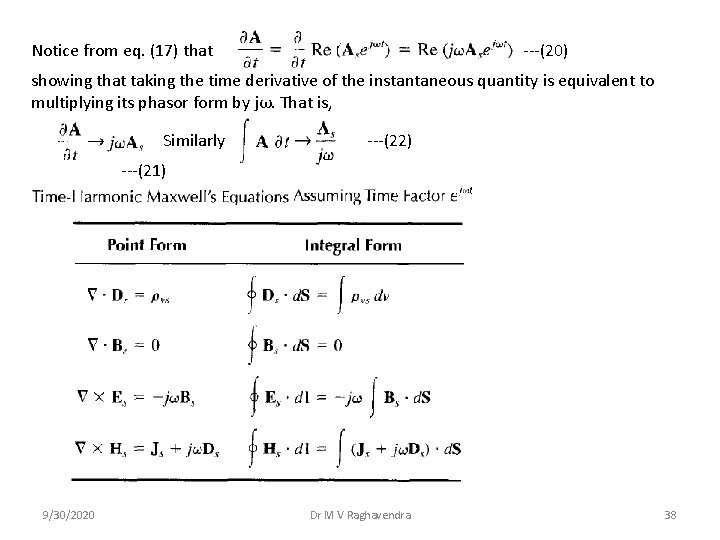

Notice from eq. (17) that ---(20) showing that taking the time derivative of the instantaneous quantity is equivalent to multiplying its phasor form by jω. That is, Similarly ---(22) ---(21) 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 38

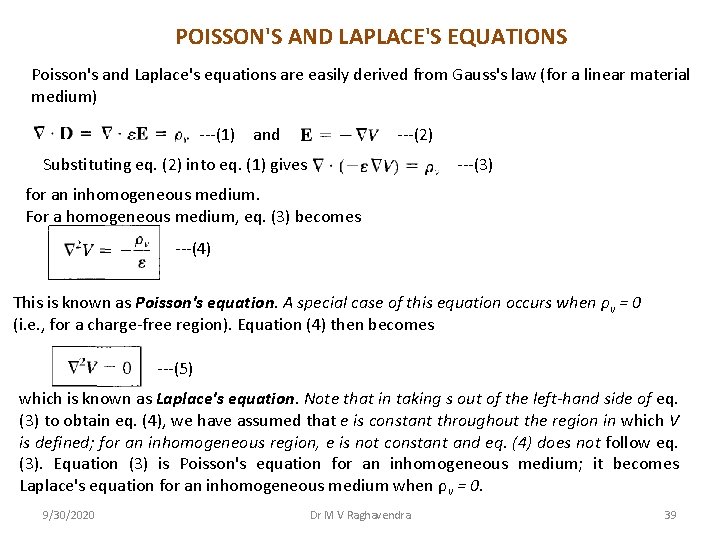

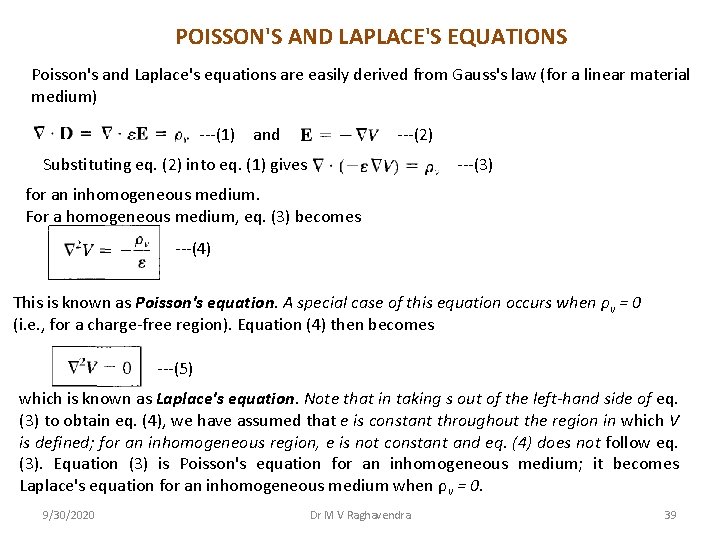

POISSON'S AND LAPLACE'S EQUATIONS Poisson's and Laplace's equations are easily derived from Gauss's law (for a linear material medium) ---(1) and ---(2) Substituting eq. (2) into eq. (1) gives ---(3) for an inhomogeneous medium. For a homogeneous medium, eq. (3) becomes ---(4) This is known as Poisson's equation. A special case of this equation occurs when ρv = 0 (i. e. , for a charge-free region). Equation (4) then becomes ---(5) which is known as Laplace's equation. Note that in taking s out of the left-hand side of eq. (3) to obtain eq. (4), we have assumed that e is constant throughout the region in which V is defined; for an inhomogeneous region, e is not constant and eq. (4) does not follow eq. (3). Equation (3) is Poisson's equation for an inhomogeneous medium; it becomes Laplace's equation for an inhomogeneous medium when ρv = 0. 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 39

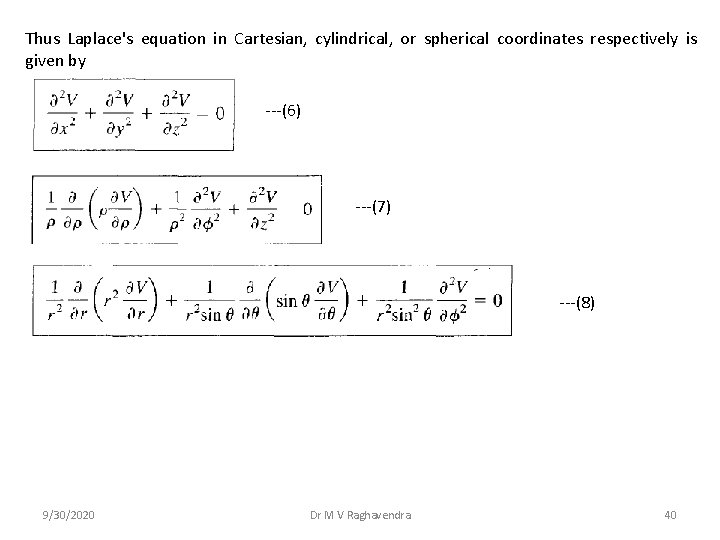

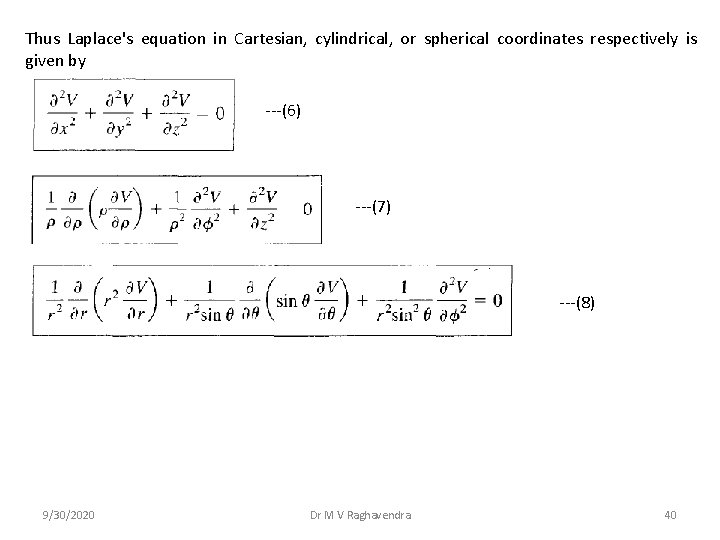

Thus Laplace's equation in Cartesian, cylindrical, or spherical coordinates respectively is given by ---(6) ---(7) ---(8) 9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 40

9/30/2020 Dr M V Raghavendra 41