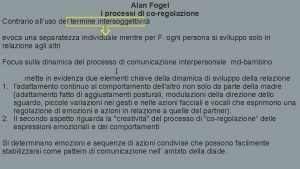

Eighteen to Twenty Four Months Fogel Chapter 10

- Slides: 101

Eighteen to Twenty -Four Months Fogel Chapter 10 Created by Ilse De. Koeyer-Laros, Ph. D.

Overview Chapter 10 • Motor & Cognitive Development • Emotional Development • Social and Language Development • Family and Society Experiential Exercises

Between 18 and 24 months, toddlers • walk & start to run • feed themselves • start to dress themselves • are likely to start toilet learning (between 18 & 36 months) • still nap in the afternoon; it is not uncommon for them to wake occasionally at night Picture from: http: //jackandjillnursery. co. uk/wb/pages/oxton-nursery. php

Motor & Cognitive Development Sensorimotor Stage VI (18 to 24 months) – the invention of new means through mental combinations – children can think about the possible paths to a goal, eliminate the most improbable ones, and only then act – they now have clear object permanence

Motor & Cognitive Development: Symbolic Play Symbol – a representation of a thing or event that is conventionally shared among the members of a community • in Stage VI, the symbol becomes detached from its original context • it becomes something that can be manipulated and explored Picture from: www. doh. state. fl. us/. . . /module 4/lesson 1_4. html

Motor & Cognitive Development: Symbolic Play Between 18 and 24 months, toddlers develop the ability to execute complex play sequences that require multiple symbols & advance planning Pictures from: www. dalianmitmita. com

Motor & Cognitive Development The Ability to Categorize Objects By 18 months, infants learn to categorize by sequential order, or by cause and effect • they remember better if items & events are organized into a sequence – e. g. , a teddy bear is undressed, put into the tub, washed, and then dried • they can remember sequences up to 2 weeks later (whether familiar or unfamiliar)

Motor & Cognitive Development The Ability to Categorize Objects Script – an organization of concepts and memories in terms of how the events are related to each other in time – become increasingly important to represent reality & remember action sequences – 2 -year-olds cannot memorize long lists of new words or concepts, but they can execute complex sequences of related actions

Motor & Cognitive Development Favorite Toys Between 18 and 24 months, children love • pegboards in which they can fit objects of different shapes in the corresponding holes • containers (and putting things in them) • nesting-cup toys, in which smaller cups are placed inside successively larger cups Pictures from: http: //mae 12. wordpress. com/ simplebounty. wordpress. com/2008/01/

Motor & Cognitive Development Smart Toys, TV, & the Internet Between 18 and 24 months, infants become more interested in TV and ‘smart toys’ – about 40% of 3 -month-olds in the US regularly watch TV, DVDs, or videos – babies under age 1 watch on average 1 hr/day; at age 2, this is 1. 5 hours per day – about 75% of parents report that their infants under age 2 watches TV; 1 in 5 watches at least 2 hrs/day – reasons for using these media: • entertainment, babysitting, and education

Motor & Cognitive Development Smart Toys, TV, & the Internet One study showed that smart toys are neither beneficial nor harmful – if infants engage with the world at their own level, it makes little difference what kind of toy is available so long as it is interesting – parents can encourage development with inexpensive low-tech toys as easily as with expensive ones

Motor & Cognitive Development Smart Toys, TV, & the Internet TV, DVD, and video viewing has been shown to have harmful effects on cognition and brain development for children under the age of 3 Picture from: parentzing. wordpress. com

Motor & Cognitive Development Smart Toys, TV, & the Internet • Regardless of other risk factors, more hours of TV, DVD or video at ages 1 and 3 were related to — more aggression at age 4 — attention & hyperactivity at age 7 • For every hour of TV watched per day, 2 -yearolds knew 6 -8 fewer words

Motor & Cognitive Development Smart Toys, TV, & the Internet Parents should carefully monitor children’s TV viewing & limit the amount of time children are allowed to watch (max. 15 -30 minutes per day) — infants learn best by acting and not by simply observing — pots and pans will make a baby just as smart as an expensive toy Picture from: hubpages. com/hub/The-Importance-of-Play

Motor & Cognitive Development Smart Toys, TV, & the Internet In the US, children spend an average of only 30 minutes of unstructured outdoor time per week — outdoor play and other nature experiences have been shown to lower depression, improve attention and concentration, and increase self-discipline Picture from: gennasuspapillons. blogspot. com

Emotional Development Between 18 and 24 months, emotional expressions continue to become more complex & more related to communicative situations Picture from: camdennguyen. blogspot. com/

Emotional Development Positive Emotions After 18 months, infants are more likely – to smile during joint activity & attention with their mothers – to smile when they experience periods of affective sharing – to initiate positive emotions in their communications with the parent

Emotional Development Positive Emotions In the 2 nd year, laughter • takes on specific meaning within the motherinfant communication system • serves to get attention • mother-infant dyads develop their own styles of laughing together – one mother would frame an opportunity for infant laughter by providing all the facial features of a laugh, and waiting until the infant provided the actual laugh before she laughed in unison

Emotional Development Symbolic Thought & Emotional Experience • After 18 months, fear can be evoked by a symbolic mental image – children develop fears of the dark and of things that might lurk behind doors, refrigerators, and other unseen places • Dreams can also be a source of fears — but nightmares do not appear until after the second birthday

Emotional Development Symbolic Thought & Emotional Experience By 20 months, about one-third of all children will talk about one or more of the following states: – sleep/fatigue (“tired”) – pain (“ouch”) – distress (“sad”) – disgust (“yuck”) – affection (“love Mommy”) – value (“good, ” “bad”)

Emotional Development Symbolic Thought & Emotional Experience • By 24 months, toddlers — engage in conversations about their feelings — talk about the causes of their feelings — play games with siblings in which they pretend to have certain kinds of feelings • The verbal expression of internal experience is one of the major characteristics of the existential self

Emotional Development Self-Conscious Emotions • Toddlers recognize themselves in a mirror & tend to show embarrassment when they do – embarrassment (or shame) is a self-conscious emotion – one has to realize that others are different from the self & that the self is exposed, separate, and likely to be evaluated by others • Other self-conscious emotions emerge around the 2 nd birthday – guilt, jealousy, and pride Picture from: raisingchildren. net. au/. . . /context/752

Emotional Development Self-Conscious Emotions Pride • the result of meeting their own standards • awareness of having accomplished a personal goal in the eyes of another person Picture from: www. cremedelacreme. com/programs/toddlers. asp

Emotional Development Self-Conscious Emotions Pride & shame develop within the context of communication about success or failure in meeting standards, rules, & achievements in one study, children were more likely to show guilt, when their parents responded more positively to the child’s achievements Picture from: http: //thankgoodnesschildcare. com/Toddlers. html

Emotional Development Self-Conscious Emotions Feelings related to anger • defiance, negativism, and aggression, due to – a growing sense of independence – a feeling that the self is separate from others • Erikson: – two emotional poles of this phase are autonomy (pride, defiance) & shame (doubt, disappointment)

Emotional Development Coping with Stress Teddy bears & favorite blankets are used to selfcomfort in stressful situations & when parents are not around toddlers can become attached to these objects: they constantly want them close & show signs of anxiety & distress when separated from them Picture from: reviews. ebay. com

Emotional Development Coping with Stress • A blanket seems to be an effective substitute for the mother, at least for brief periods – blankets are soft and cuddly – they carry familiar smells that may remind the child of home & impart an sense of security • Attachment objects have been called transitional objects – seem to serve as a bridge between a child’s total reliance on the mother & the development of individuation

Emotional Development Coping with Stress There seems to be little need for transitional objects when children have continued access to physical contact – 4. 9% of rural Italian children had transitional objects, vs. 31. 1% of children in Rome – only 38% of Japanese infants had an object attachment compared to 62% of US infants Picture from: www. abibitumikasa. com

Emotional Development Coping with Stress • In one study, infants were exposed to a variety of frustrating situations – some children showed distress by screaming, hitting, kicking, or banging – more distressed children were less able to selfcomfort (e. g. , distracting themselves) • Mothers of more distressed children were more likely to try to help rather than letting the children solve the problem themselves

Emotional Development Coping with Stress Parents play a crucial role in the development of emotion regulation skills children are better regulated if mothers have talked with them about children’s feelings Picture from: http: //www. parents-in-a-pickle. com

Emotional Development Coping with Stress • Early deficits in neurological development that may also play a role in emotion regulation – children whose mothers smoked prenatally are more disruptive & less able to self-calm than other infants • Emotion regulation difficulties were more likely by the end of the 2 nd year if infants had been less able to establish joint attention with parents in the 1 st year

Emotional Development Coping with Stress Children adopt the emotional regulation styles found in their families • For example, – 2 -year-olds tended to seek comfort & assistance from preschool caregivers with a family history similar to that of their mothers • Adults typically choose partners who have similar family histories & attachment styles

Emotional Development Coping with Stress Children develop internal working models – expectations for particular kinds of attachment styles • they continue to replicate those even when it is not in their best interest • breaking out of the cycle of difficult interpersonal relationships often requires individual, couple, or family psychotherapy Picture from: www. bostonmarriagetherapy. com/

Emotional Development Coping with Stress In sum, • the parent-infant relationship & the active role of adults are crucial for emotion regulation • transitional objects are useful but can’t replace an adult • even though toddlers begin to acquire language, most emotion regulation is nonverbal – this may help explain the lasting effect on the formation of later interpersonal relationships

Emotional Development Separations from Primary Caregivers By the end of the 2 nd year, toddlers understand that parents will return after a separation In one study (in a public park), boys left parents more often than girls, but they did not wander off further or longer

Emotional Development Separations from Primary Caregivers Infants separate more easily • if the parent prepares the child & gives instructions for what to do during separation • if dropped off at a familiar setting • if the caregiver stays at a distances shortly before departure • if dropped of by father rather than mother (mothers took longer to leave the children)

Social & Language Development Important changes in language between 18 and 24 months: 1. a dramatic increase in vocabulary 2. the beginning of multiword sentences Picture from: http: //amazingtrips. blogspot. com/2007_02_01_archive. html

Social & Language Development The Vocabulary Spurt Vocabulary spurt: rapid increase in vocabulary around 18 months – children begin to acquire 5 or more words per week (primarily object names) – it is as if they discover that objects have names and become obsessed with naming things & asking for object names – the naming insight

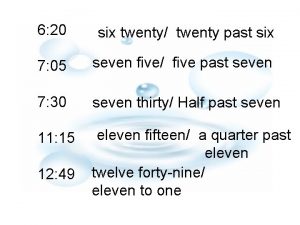

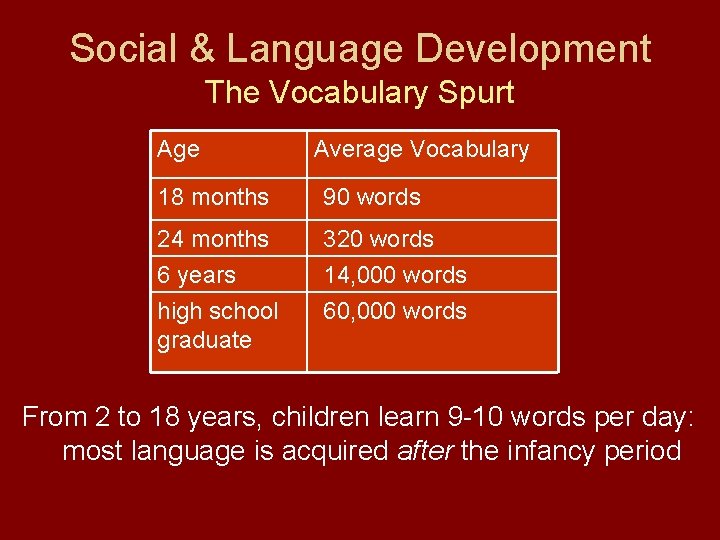

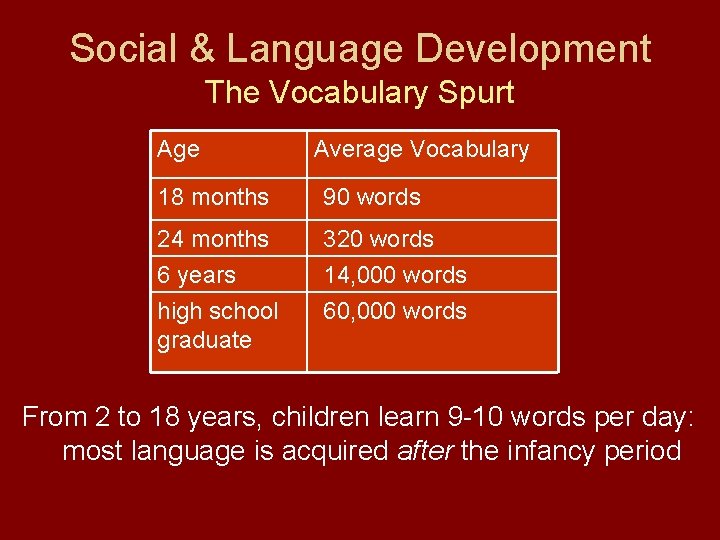

Social & Language Development The Vocabulary Spurt Age Average Vocabulary 18 months 90 words 24 months 320 words 6 years high school graduate 14, 000 words 60, 000 words From 2 to 18 years, children learn 9 -10 words per day: most language is acquired after the infancy period

Social & Language Development The Vocabulary Spurt • Nouns predominate in all languages • Toddlers of this age also acquire: – verbs (play, kiss) – adjectives (hot, yucky) – adverbs (up, more) • They can use words to make comments – on objects (gone, dirty) – on their own actions and feelings (uh-oh, tired)

Social & Language Development The Vocabulary Spurt Just before the acquisition of multiword speech, infants use single words in more complex ways that suggest a subject and a predicate – after 18 months, infants may point to a shoe and say “dirty” or “Mommy” – this could be interpreted as “the shoe is dirty” or “this is Mommy’s shoe”

Social & Language Development Multiword Speech Around 20 months, sentences emerge & children begin to – pursue objects after multiple hidings – use tools in deliberate ways – engage in symbolic play

Social & Language Development Multiword Speech Cognitive abilities guide language learning • Children – combine symbolic objects & gestures in novel ways – classify objects by sorting – solve complex problems mentally without trial-and-error behavior Picture from: compassionatesolutions. ca

Social & Language Development Multiword Speech • Prior to using 2 -word sentences, children may combine a gesture & a word – seeing a sleeping bird, the child might point at the bird and say “nap” – a month later, the child can say “bird nap” to mean the same thing: the bird is taking a nap • Toddlers discover they can create new meanings simply by changing the word order • The first 2 -word combinations are idiosyncratic usages that only later become conventional

Social & Language Development Multiword Speech • Toddlers discover they can create new meanings simply by changing the word order • The first 2 -word combinations are idiosyncratic usages that only later become conventional – this is similar to the early idiosyncratic use of communication gestures that gradually develops into conventional communication signs

Social & Language Development Multiword Speech Telegraphic speech leaves out small words such as prepositions and word endings such as -ing, s sounds, and -ed, – these additional refinements to the meaning of words and sentences – simpler endings such as -ing, the plural -s, and the possessive -’s are acquired first – next, the more difficult use of the verb “to be” with all its tenses, auxiliaries, and contractions

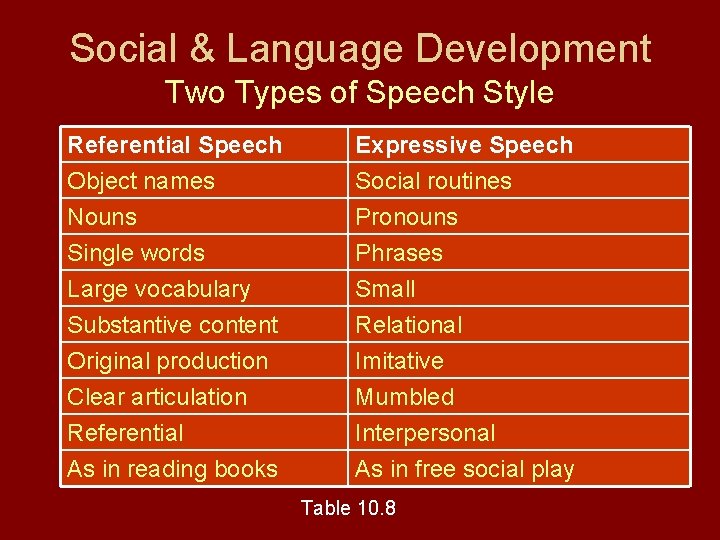

Social & Language Development Two Types of Speech Style Young children show two distinct styles of vocabulary acquisition – referential speech – expressive speech

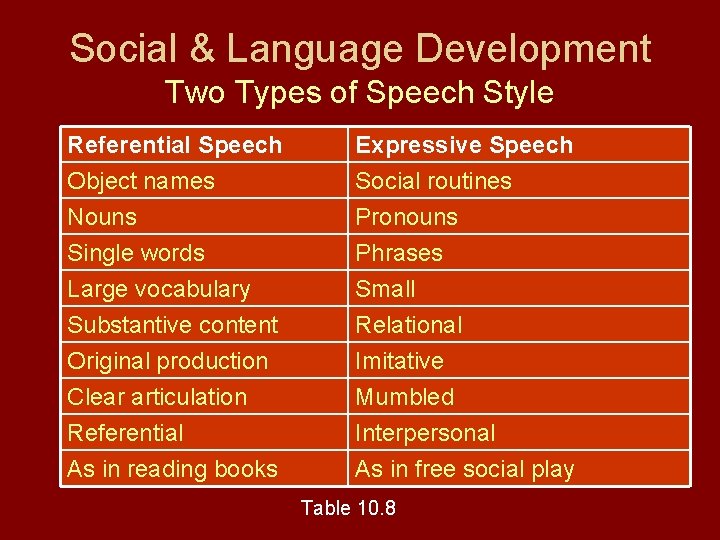

Social & Language Development Two Types of Speech Style Referential Speech Object names Nouns Single words Expressive Speech Social routines Pronouns Phrases Large vocabulary Substantive content Original production Clear articulation Referential As in reading books Small Relational Imitative Mumbled Interpersonal As in free social play Table 10. 8

Social & Language Development Two Types of Speech Style These styles of language acquisition • are used by most children in different contexts • may reflect the speech spoken to them – if a caregiver clearly labels objects, the child may focus more on individual words (referential) – if the caregiver uses social language like “D’ya wanna go out” or “I dunno where it is, ” the child is likely to hear these as whole phrases (expressive)

Social & Language Development Language & the Social Environment • Adults increasingly rely on verbal suggestions and commands – requests: asking for information through “what” and “where” questions (“Where’s the doggie? ”) – comments are responses to the children’s utterances or attempts to initiate a conversation (“Yes, that’s an apple”; “This is the same car we saw the other day”) • After children’s mispronunciation, mothers simply repeated the correct pronunciation

Social & Language Development Language & the Social Environment The child develops greater linguistic competence when the adult – uses speech that is more responsive to the child’s focus of interest – uses the child’s interest to achieve a joint focus of attention before talking – uses clear speech Picture from: http: //www. toddler-activities-at-home. com

Social & Language Development Guided Participation Guided participation – the active role that children take in observing & participating in the organized activities of the family & society – from the adult’s perspective, the child is merely “playing games” or “playing at” cooking or taking care of a doll – from the child’s perspective, the child is actually doing the task as an active participant

Social & Language Development Guided Participation • establish coordinated joint attention based on the child’s initiatives • the adult must also constrain the child’s participation (e. g. , for safety) • the adult transfers responsibility for larger segments of the task to the child Picture from: www. cyfernet. org/local_spotlight/04 -08. htm

Social & Language Development Guided Participation Cultural differences • Mothers from the U. S. were compared with Maya Indian mothers from Guatemala on how they helped their 20 -month-olds use a set of nesting dolls – the U. S. mothers acted more like peers, wanting to take turns in combining dolls and commenting on the process – the Maya mothers retained more of an adult-child status differential

Social & Language Development Guided Participation When adults participate in children’s spontaneous actions, children can achieve higher levels of language, play, and cognitive development – they develop higher levels of symbolic play when mothers give more options that stimulate creativity – coordinated joint attention is less likely if mothers are depressed or have a low sense of self-efficacy Picture from: www. littlebundles. ca

Social & Language Development Guided Participation Individual differences • sharing and mutuality vary with the task or situation – shared pretend play evokes more sharing • children with difficult temperament or attachment problems receive more explicit instructions (more by fathers than mothers) Picture from: www. discoverytoyslink. com

Social & Language Development Guided Participation Functions of parent-child pretend play • just for fun • to meta-communicate about conflicts or disagreements – mothers may engage in pretend play to give the child something to do, to redirect an otherwise undesirable activity, or to make light of a negative emotion • for guidance, such as teaching proper conduct – more likely in Taiwanese than in North American families

Social & Language Development Discipline & Compliance Authoritative parents combine empathy & firmness They – use firm demands – express their own anger or distress appropriately – do not use power to control the child Picture from: www. whattoexpect. com

Social & Language Development Discipline & Compliance Children of authoritative parents • show purposive, independent behavior • are cooperative with adults • show friendliness to peers • are more likely to imitate their mothers • are likely to become upset after violating standards of conduct Picture from: http: //www. njkidfit. com/childrensprograms. nxg

Social & Language Development Discipline & Compliance By this age, the father begins to play a substantial role in family processes more sensitive & involved fathers have children who are more socially competent and less defiant Pictures from: www. fathers. com & www. camh. net

Social & Language Development Discipline & Compliance Parental proactive behavior – any action that has the goal of a positive outcome for the child – e. g. , joining the infant’s play and then try to make the child do something else – avoiding problems by proactively controlling, or regulating access to, the environment – preventive measures • e. g. , talking to the child & giving something to eat while shopping to avoid tantrums

Social & Language Development Discipline & Compliance Coercive & controlling discipline • in one study, mothers & fathers in “troubled” families were more likely to use control instead of guidance & authoritative approaches – children in these families showed the most defiance and the most negative emotion • teenage mothers – are more coercive (on average) – tend to infer more anger & defiance in infants’ emotion expressions Picture from: www. squidoo. com

Social & Language Development Discipline & Compliance • Corporal punishment – using physical force that causes pain to the child but not injury • A review of 88 studies (n=36, 309) found that corporal punishment in the early years related to – poor self control – poor relationship with parents throughout childhood – more criminal or antisocial behavior – abuse of children’s own children or spouse in adulthood

Social & Language Development Discipline & Compliance Some suggest that occasional spanking may be used in serious offenses (e. g. , running into the street), especially if the spanking is later accompanied by – explanations – recognition of the child’s feelings – expressions of love Picture from: www. parentlineplus. org. uk

Social & Language Development Discipline & Compliance Ethnic differences • Caucasian-American children who were spanked were at 5 times greater risk for later behavior problems • for African-American and Hispanic-American families, there was no relationship – spanking is viewed as a normal parental behavior and is rarely done impulsively or in anger

Social & Language Development Discipline & Compliance • In general, – focus on praise, proactive parenting, respect for the child’s point of view, and mild sanctions – toddler defiance is often a way for children to express their feelings, assert their budding self-awareness, & experiment with taking initiative and taking charge • Defiance that is aggressive or violent is typically a sign of an emerging vicious cycle implicating parental coercion and aggression

Social & Language Development Peer Interactions • Toddler-peer play is different in quality from toddler-parent play • When given a choice, toddlers almost always choose a peer over their mothers to play with – they spend more time with the peer and make fewer bids for their mother’s attention when a peer is present Picture from: student. britannica. com

Social & Language Development Peer Interactions Between 18 and 24 months, peer play begins to take on a more game-like quality – children take simple turns • e. g. , offering & accepting, throwing & catching, or simple verbal exchange – words are used, but not at the same level of elaboration as in adult-infant games – there is little cooperation & collaboration

Social & Language Development Peer Interactions Relationship – a continuing pattern of communication between two or more people in which past encounters provide a historical background for future encounters it is not until the end of the 2 nd year that children can form lasting relationships with other children Picture from: www. bigelowcoop. org

Social & Language Development Peer Interactions Differences in peer relationships • compatible friends – direct mostly positive behaviors toward each other & refrain from conflicts • enemies or fighting friends – tend to engage in conflicts most of the time • other children tend not to interact with each other (ignoring), either positively or negatively

Social & Language Development Peer Interactions • The types of toys used in peer play influence the types of interactions between the children • In one study, researchers found – more sophisticated interaction between 18 -month-olds & a greater expression of positive emotion with large play equipment (ladders, slides, boxes) – with small portable toys, more conflict & negative emotion was expressed – children were most creative in the no-toy situation

Social & Language Development The Sense of an Existential Self The existential self: 18 -month-olds begin to create a whole picture of themselves as someone who can be recognized & distinguished They – recognize themselves in a mirror – categorize & remember familiar sequences of events (scripts) Picture from: www. parentingtoddlers. net

Social & Language Development The Sense of an Existential Self Use of personal pronouns begins around the same time as mirror self-recognition – expressing intended actions (“I do it, ” “I hold it”) – making requests or proposals (“I wanna play with that one”) – stating propositions (“I have the crayon”)

Social & Language Development The Sense of an Existential Self After 18 months, infants are also beginning to reason about other people’s desires • In one study, 14 - and 18 -month-olds watched while adults ate either crackers or broccoli – 14 -month-olds offered the adult only crackers, assuming that the adult would like what the child liked, regardless of the adult’s expressed preferences – 18 -month-olds, offered whichever food the adult seemed to prefer

Social & Language Development The Sense of an Existential Self Infants who are more self- and other-aware • are more securely attached to their mothers & fathers • show more concern for other’s distress • can coordinate mirror image imitation • are more competent with peers

Social & Language Development Infantile Autism • Autism – a developmental psychopathology that may be reliably diagnosed during this age period – impaired ability to interact socially – speech and language deficits – unusual movements of the body • 6 to 13 out of every 1, 000 individuals – affects 2 to 4 times more males than females Picture from: www. bukisa. com

Social & Language Development Infantile Autism Difficulty with coordinated joint attention & intersubjectivity – don’t use social referencing or affective sharing – don’t respond appropriately to the desires or distress of others – less distressed at separation from mothers – less likely to imitate others – don’t pretend – unlikely to initiate social interaction – don’t talk, or only in monologues

Social & Language Development Infantile Autism Many children with autism never develop a sense of an existential self & other – do not show embarrassment in front of a mirror or when getting a photo taken – do not seem to have a sense of guilt • suggests that they cannot see themselves in the eyes of others – are less likely to use personal pronouns or to refer to themselves in conversations Picture from: www. redbookmag. com

Social & Language Development Infantile Autism They can • develop secure attachments with their mothers – although they are more likely than others to develop disorganized attachment relationships • point & use gestures to ask for what they want • be advanced in some perceptual and objectrelated skills • imitate object-related tasks better than typically developing children

Social & Language Development Infantile Autism • Play is less likely to be symbolic & more likely to be aggressive or self-stimulatory – less likely to initiate social play with peers – tend to use toys in ways different from their appropriate functions (e. g. , banging a toy telephone rather than pretending to talk) • These children can acquire pretend play when adults use guided participation Picture from: characteristicsofautism. net

Social & Language Development Infantile Autism • A small number of children with autism show exceptional skills in one area – some are gifted artists but draw only one subject, such as public buildings and monuments • High-functioning autistics may be able to hold jobs & create a life for themselves • Most children with autism will change little and acquire only minimal social skills & self-care

Social & Language Development Infantile Autism Causes • believed to have origins in early infancy & prenatal development • genetic & chromosomal abnormalities • possibly brain & other physiological problems that emerge during early development – abnormalities in the limbic system (e. g. , amygdale) – abnormalities in the auditory region of the brain stem – myelin pathologies

Social & Language Development Infantile Autism • Autism originates in early infancy, but typically isn’t diagnosed until age 4 or 5 • One study found that at 18 months, children later diagnosed with autism showed a lack of – pointing, showing objects, looking at others, and orienting to their name Picture from: sfari. org

Social & Language Development Infantile Autism Another study found that 2 or more of the following at 18 months predicted autism at 30 months: – a lack of pretend play – a lack of pointing – a lack of interest in social relationships – an absence of social play – an inability to establish joint attention with the caregiver

Social & Language Development Infantile Autism Treatments for young children • Most focus on improving the ability to engage with another person & to develop coordinated joint attention • Early intervention may have more lasting effects • Studies of sensorimotor deficits may lead to new treatments for infants that might positively affect brain development

Family & Society Informal Support Systems Parents, particularly mothers, who receive more support – – – are less likely to be punitive are more likely to play & be affectionate respond more quickly to babies’ cries have more secure attachments are more nurturant have more positive attitudes about child rearing – abuse their infants less Picture from: www. drinktoglow. com

Family & Society Informal Support Systems A larger & more complex support network is related to better-quality support and to parental competence in child rearing Two main sources of support • spouses • maternal grandmothers Picture from: familyplayandlearn. com/June. Activities. html

Family & Society Informal Support Systems Social support is less likely to occur when • infants have special needs (e. g. , preterm) • parents are abusive and/or have poor interpersonal skills • parents distrust sources of support – e. g. , due to cultural reasons Picture from: www. ehponline. org

Family & Society Informal Support Systems Social networks are more supportive when • the psychological stress of the parents is relatively low • the family is experiencing an expected or understandable life transition (e. g. , a temporary job loss, a death in the family) • the source of stress is a single event rather than a long-term problem

Family & Society Formal Support Systems • Formal support systems offer services including – childbirth education well-baby care, parent training programs, early childhood education for disadvantaged toddlers • Educational interventions for parents can be enormously effective – especially when combined with health care & income support Picture from: www. stmark-elca. org

Family & Society Formal Support Systems • For families at risk, a comprehensive effort is most effective • Successful programs combine – preschool education – a nurse–home visitor – an effort to link parents up with other formal and informal community supports • education, job training and placement, recreational facilities, etc.

Family & Society Formal Support Systems • Multisite, multimethod intervention programs have been shown to – decrease reliance on welfare – reduce parental substance abuse – lower the incidence of criminal acts when the infants become adolescents • Neither parent education alone nor child care alone is as effective as the two are in combination

Family & Society Formal Support Systems Head Start • Participating children 15 years later: – had fewer teen pregnancies – had a higher high school graduation rate – were more likely to be employed – were less likely to have been arrested • Head Start children have a more enriched early childhood and do better in preschool & elementary school than controls

Family & Society Formal Support Systems Experimental programs include: • including children under age 3 • family service centers • transition to elementary school programs • comprehensive child developmental centers • family child-care projects – these efforts combine services for the developing child with attempts to lift the family from poverty Picture from: blog. mlive. com

Family & Society Infant-Parent Mental Health (IPMH) • an emerging multi-disciplinary specialization • focuses on the relational context of the development of young children • commitment to trans-disciplinary integration and to the treatment of developmental, relational, and emotional distress from a whole-child-in-relationship perspective Picture from: www. cimhd. org

Family & Society Infant-Parent Mental Health (IPMH) Clinical Practice in IPMH • the caregiver-child relationship is the “client” • intervention with parents can break the cycle of intergenerational transmission of pathology • IPMH is ultimately a preventative approach, responding to difficulties in the infant-parent relationship before they become major problems Picture from: cehd. umn. edu

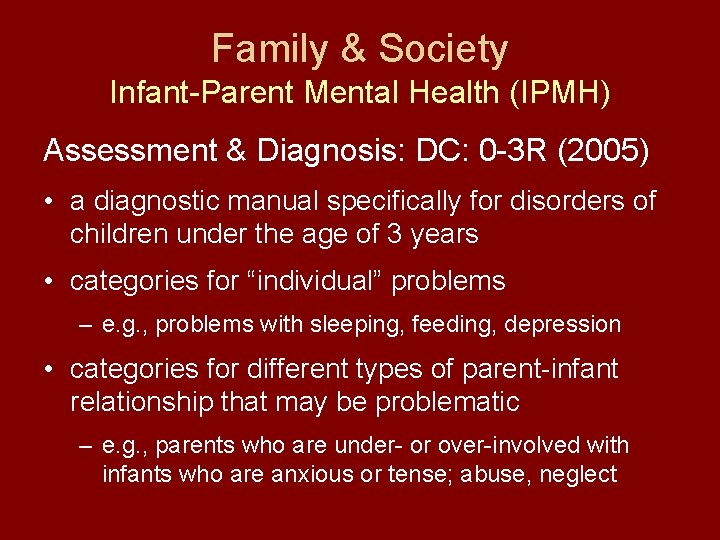

Family & Society Infant-Parent Mental Health (IPMH) Assessment & Diagnosis: DC: 0 -3 R (2005) • a diagnostic manual specifically for disorders of children under the age of 3 years • categories for “individual” problems – e. g. , problems with sleeping, feeding, depression • categories for different types of parent-infant relationship that may be problematic – e. g. , parents who are under- or over-involved with infants who are anxious or tense; abuse, neglect

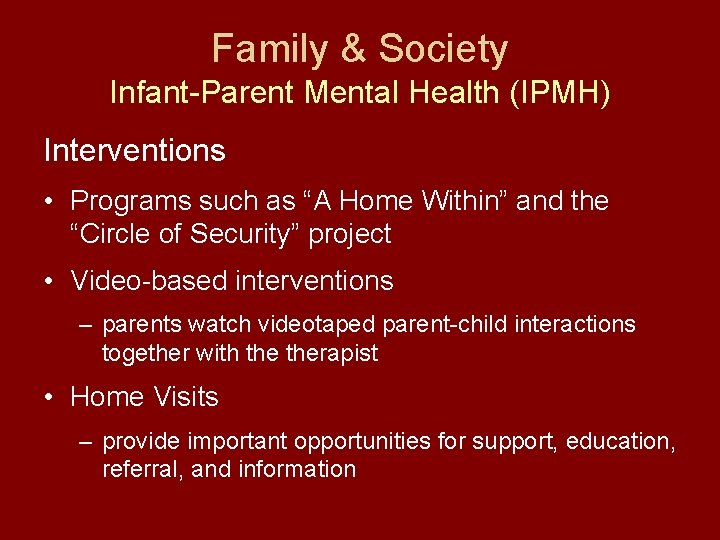

Family & Society Infant-Parent Mental Health (IPMH) Interventions • Programs such as “A Home Within” and the “Circle of Security” project • Video-based interventions – parents watch videotaped parent-child interactions together with therapist • Home Visits – provide important opportunities for support, education, referral, and information

Experiential Exercises: Words & Feelings This exercise centers around the experience infants have when they begin to use symbolic language and thought. • Lying on the floor, relax: notice your breathing, your heartbeat, pressure on your body, your eyes blinking. Notice your thoughts coming and going. • Your partner now slowly reads you a list of words (see p. 523), using appropriate accents and intonations. Notice how your thoughts change with each word & notice the pictures and images that run through your mind. • Think about the experience a young child might have when they heard these words. What would go through a young child’s mind after having attempted to form some of these words on his or her own?

Experiential Exercises: Mirror self-recognition The purpose of this exercise is to evoke the experience of seeing oneself in a mirror for the very first time, and thus imagine the sense of otherness or foreignness of the mirror image, sense of shame or pride, etc. • Sit at a desk or table with a mirror, a blank piece of paper and a pencil. • Close your eyes for 2 -3 minutes and relax. • Open your eyes & examine your face in the mirror. As you study your face, remain aware of your sensations and emotions. • Write down your experience, then close your eyes once more and relax for another 2 -3 minutes.

Experiential Exercises: Mirror self-recognition • Open your eyes & cover one eye with your hand. • Study your face for second time using the uncovered eye. Notice your feelings and experience during this portion of the exercise. Do you see yourself differently than before? Write down your experience • Close your eyes for another 2 minutes and repeat this portion of the exercise with the opposite eye uncovered. • Compare your three experiences. Imagine the different ways in which an infant may see himself when looking into a mirror for the first time. What do you imagine would go through an infant’s mind?

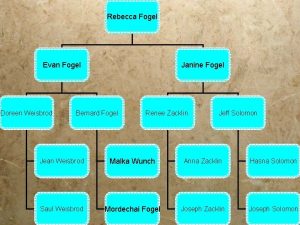

Dr bernard fogel

Dr bernard fogel Alan fogel

Alan fogel Sap trade management

Sap trade management Micah fogel

Micah fogel How did daisy react after gatsby left for military service

How did daisy react after gatsby left for military service Module 36 thinking and language

Module 36 thinking and language How many years is four score and seven years

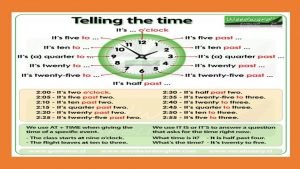

How many years is four score and seven years It's twenty past eight

It's twenty past eight How much is four score and seven years

How much is four score and seven years Summer winter autumn spring months

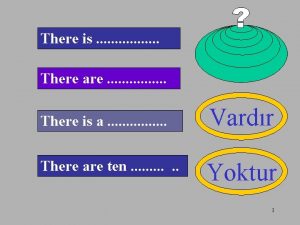

Summer winter autumn spring months Do not say there are four months

Do not say there are four months Antarctic journal four months at the bottom of the world

Antarctic journal four months at the bottom of the world Shape with one side

Shape with one side Skin assessment charting

Skin assessment charting It's twenty to nine

It's twenty to nine Games to play with your partner

Games to play with your partner Twenty questions text games

Twenty questions text games 20 point programme in community health nursing

20 point programme in community health nursing Twenty past eight

Twenty past eight Diana moon glampers

Diana moon glampers Consumer culture theory (cct): twenty years of research

Consumer culture theory (cct): twenty years of research O henry twenty years after

O henry twenty years after It is twenty to six

It is twenty to six Its five past nine

Its five past nine Whats half past

Whats half past A brief description

A brief description Twenty questions original network

Twenty questions original network I can easier teach twenty

I can easier teach twenty 160% proof rum

160% proof rum Introduction to sales management

Introduction to sales management 21 pilots hands

21 pilots hands Twenty-five to six

Twenty-five to six Twenty questions for christmas

Twenty questions for christmas A small group usually has between three and twenty people.

A small group usually has between three and twenty people. It opens at half past six

It opens at half past six It's quarter to two

It's quarter to two I lent a pencil to graham

I lent a pencil to graham Andre courreges biography

Andre courreges biography Rules of the game questions and answers

Rules of the game questions and answers Twenty first century trends in entrepreneurship

Twenty first century trends in entrepreneurship Twenty years before

Twenty years before Twenty questions

Twenty questions 20 questions

20 questions Twenty rules for writing detective stories

Twenty rules for writing detective stories Aa twenty questions

Aa twenty questions Yourt ube

Yourt ube Summer comes after spring

Summer comes after spring Sultan of 11 months

Sultan of 11 months Fall season months

Fall season months Computer power doubles every 18 months

Computer power doubles every 18 months Months of the year backwards

Months of the year backwards Cewt chart 5-11

Cewt chart 5-11 Gelds 24-36 months

Gelds 24-36 months Tsuitachi futsuka mikka

Tsuitachi futsuka mikka Asq se2 60 months

Asq se2 60 months Informal language and abbreviations

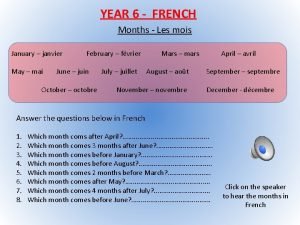

Informal language and abbreviations Janvier fevrier mars avril months in french

Janvier fevrier mars avril months in french Last 4 months

Last 4 months January and october

January and october Mars avril mai juin

Mars avril mai juin A famous monastery

A famous monastery Days of the week and months of the year

Days of the week and months of the year Piagetian and information processing theories 8-18 months

Piagetian and information processing theories 8-18 months Avl tree of months

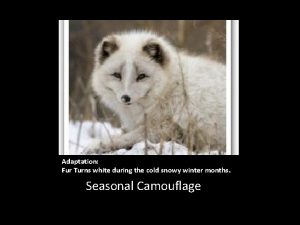

Avl tree of months Fur turns white during the cold snowy winter months

Fur turns white during the cold snowy winter months Nov 22

Nov 22 Twelve months in a year

Twelve months in a year Summer 15 days or 2 1/2 months answer key

Summer 15 days or 2 1/2 months answer key 24 months in days

24 months in days Months in dutch

Months in dutch Homework in sign language

Homework in sign language Jamie markham

Jamie markham Degree in six months

Degree in six months Unit 4 days and months

Unit 4 days and months How many months is 141 days

How many months is 141 days Months of the year

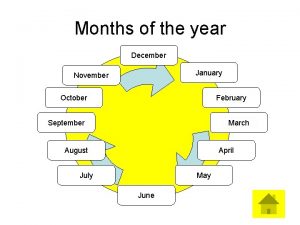

Months of the year American english dates

American english dates Hupostasis

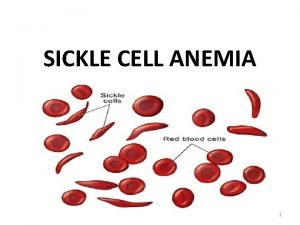

Hupostasis Sickle cell anemia symptoms

Sickle cell anemia symptoms 9 months

9 months 5 months baby in the womb pictures

5 months baby in the womb pictures 6 months before august 31

6 months before august 31 Days of the week in hindi

Days of the week in hindi 9 months before january 26 2009

9 months before january 26 2009 Define months

Define months 9 months before 26 october 2004

9 months before 26 october 2004 The sign of four: chapter 7 summary

The sign of four: chapter 7 summary Chapter 5 sign of four

Chapter 5 sign of four The sign of four chapter 10 summary

The sign of four chapter 10 summary Great gatsby chapters 3-4 summary

Great gatsby chapters 3-4 summary Lord of the flies ch 4 summary

Lord of the flies ch 4 summary Four perfect pebbles chapter 2

Four perfect pebbles chapter 2 The sign of four: chapter 5 summary

The sign of four: chapter 5 summary Great gatsby chapter four summary

Great gatsby chapter four summary Great gatsby chapter four summary

Great gatsby chapter four summary Chapter 5 principles of engine operation

Chapter 5 principles of engine operation Lord of the flies chapter 11

Lord of the flies chapter 11 Logic chapter four

Logic chapter four Presentation of data chapter 4

Presentation of data chapter 4 Chapter 17 ten words in context

Chapter 17 ten words in context 4 moments of hand hygiene poster

4 moments of hand hygiene poster Ways to show respect to others

Ways to show respect to others