Efficient FFTs On VIRAM Randi Thomas and Katherine

- Slides: 43

Efficient FFTs On VIRAM Randi Thomas and Katherine Yelick Computer Science Division University of California, Berkeley IRAM Winter 2000 Retreat {randit, yelick} @cs. berkeley. edu

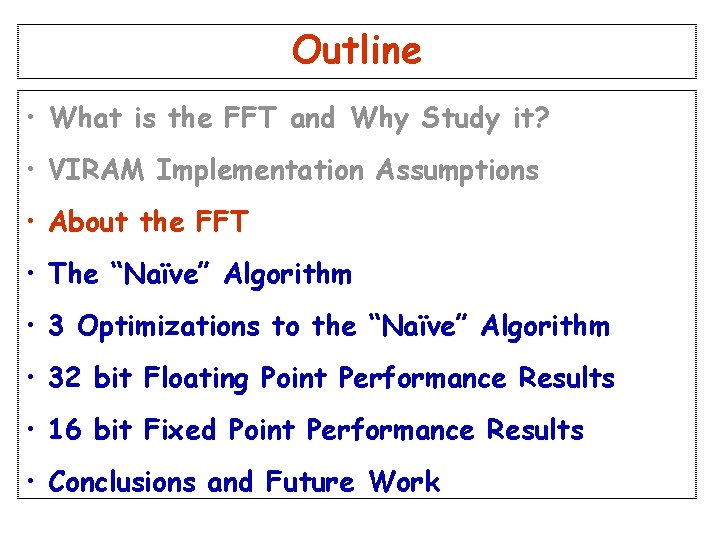

Outline • What is the FFT and Why Study it? • VIRAM Implementation Assumptions • About the FFT • The “Naïve” Algorithm • 3 Optimizations to the “Naïve” Algorithm • 32 bit Floating Point Performance Results • 16 bit Fixed Point Performance Results • Conclusions and Future Work

What is the FFT? The Fast Fourier Transform converts a time-domain function into a frequency spectrum

Why Study The FFT? • 1 D Fast Fourier Transforms (FFTs) are: – Critical for many signal processing problems – Used widely for filtering in Multimedia Applications » Image Processing » Speech Recognition » Audio & video » Graphics – Important in many Scientific Applications – The building block for 2 D/3 D FFTs All of these are VIRAM target applications!

Outline • What is the FFT and Why Study it? • VIRAM Implementation Assumptions • About the FFT • The “Naïve” Algorithm • 3 Optimizations to the “Naïve” Algorithm • 32 bit Floating Point Performance Results • 16 bit Fixed Point Performance Results • Conclusions and Future Work

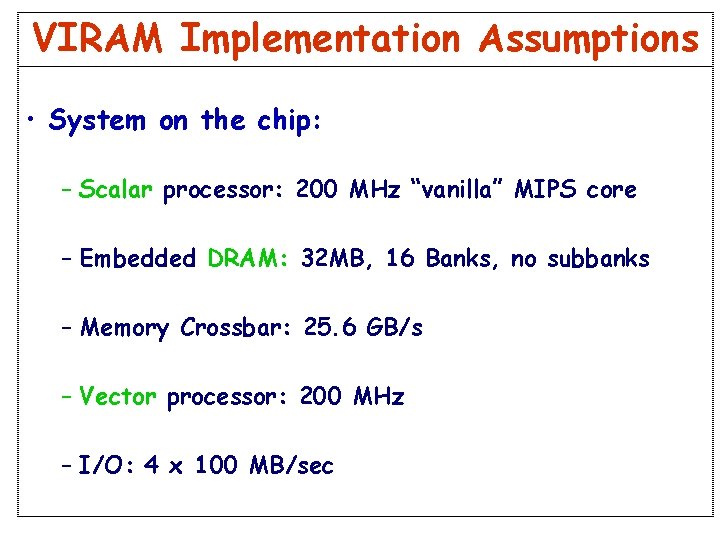

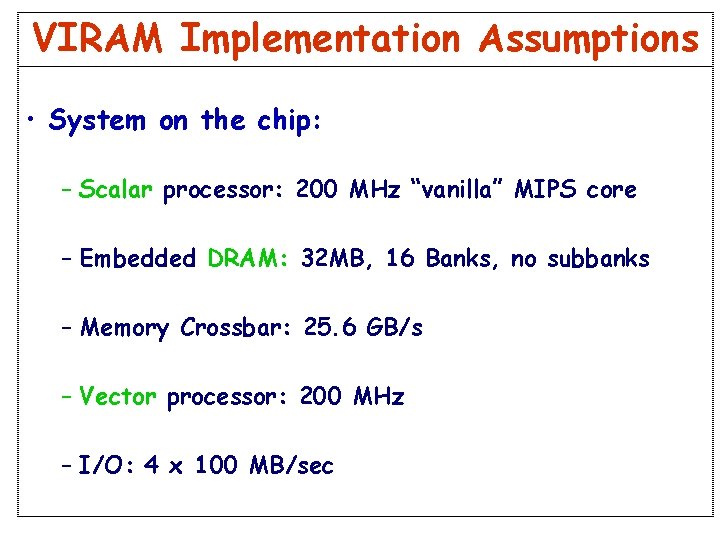

VIRAM Implementation Assumptions • System on the chip: – Scalar processor: 200 MHz “vanilla” MIPS core – Embedded DRAM: 32 MB, 16 Banks, no subbanks – Memory Crossbar: 25. 6 GB/s – Vector processor: 200 MHz – I/O: 4 x 100 MB/sec

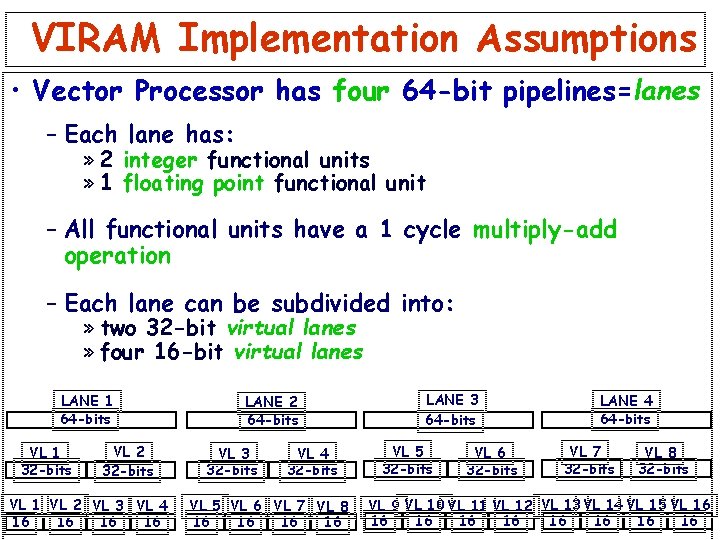

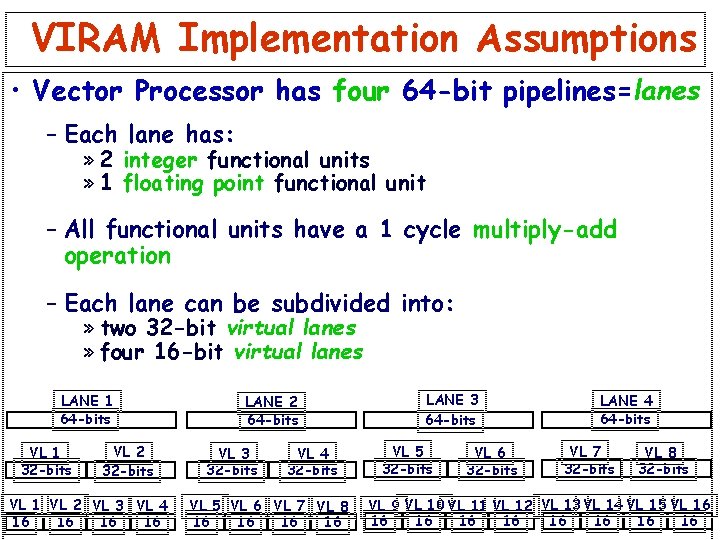

VIRAM Implementation Assumptions • Vector Processor has four 64 -bit pipelines=lanes – Each lane has: » 2 integer functional units » 1 floating point functional unit – All functional units have a 1 cycle multiply-add operation – Each lane can be subdivided into: » two 32 -bit virtual lanes » four 16 -bit virtual lanes LANE 1 64 -bits VL 1 32 -bits VL 2 32 -bits VL 1 VL 2 VL 3 VL 4 16 16 LANE 2 64 -bits VL 3 32 -bits VL 4 32 -bits VL 5 VL 6 VL 7 VL 8 16 16 LANE 3 64 -bits VL 5 32 -bits VL 6 32 -bits LANE 4 64 -bits VL 7 32 -bits VL 8 32 -bits VL 9 VL 10 VL 11 VL 12 VL 13 VL 14 VL 15 VL 16 16 16

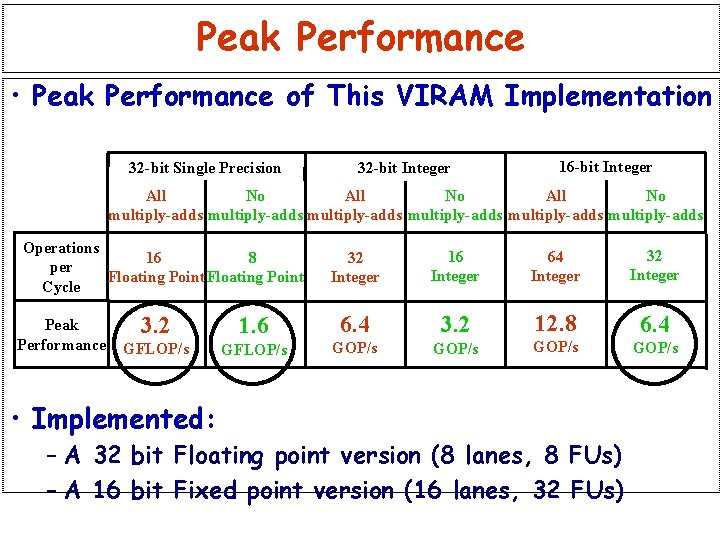

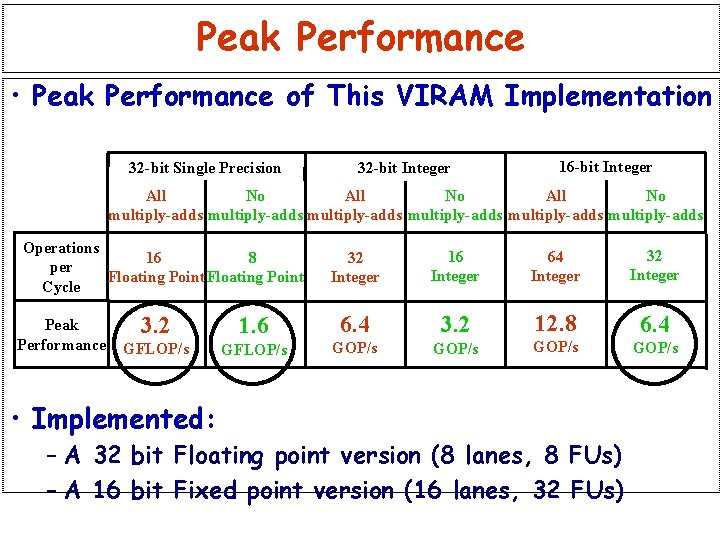

Peak Performance • Peak Performance of This VIRAM Implementation 32 -bit Single Precision 32 -bit Integer 16 -bit Integer All No multiply-adds multiply-adds Operations 16 8 per Floating Point Cycle Peak Performance 32 Integer 16 Integer 64 Integer 32 Integer 3. 2 1. 6 6. 4 3. 2 12. 8 6. 4 GFLOP/s GOP/s • Implemented: – A 32 bit Floating point version (8 lanes, 8 FUs) – A 16 bit Fixed point version (16 lanes, 32 FUs)

Outline • What is the FFT and Why Study it? • VIRAM Implementation Assumptions • About the FFT • The “Naïve” Algorithm • 3 Optimizations to the “Naïve” Algorithm • 32 bit Floating Point Performance Results • 16 bit Fixed Point Performance Results • Conclusions and Future Work

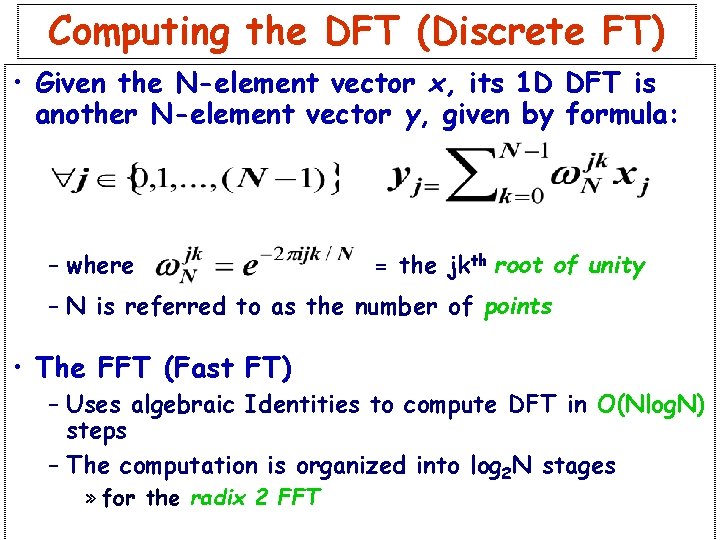

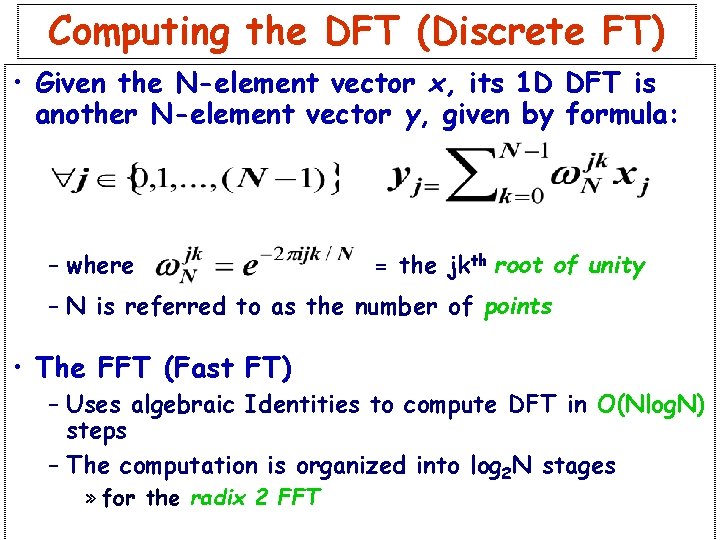

Computing the DFT (Discrete FT) • Given the N-element vector x, its 1 D DFT is another N-element vector y, given by formula: – where = the jkth root of unity – N is referred to as the number of points • The FFT (Fast FT) – Uses algebraic Identities to compute DFT in O(Nlog. N) steps – The computation is organized into log 2 N stages » for the radix 2 FFT

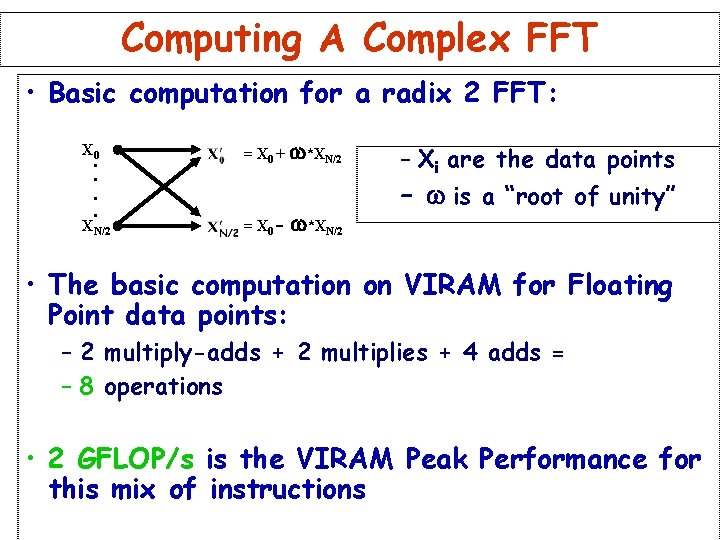

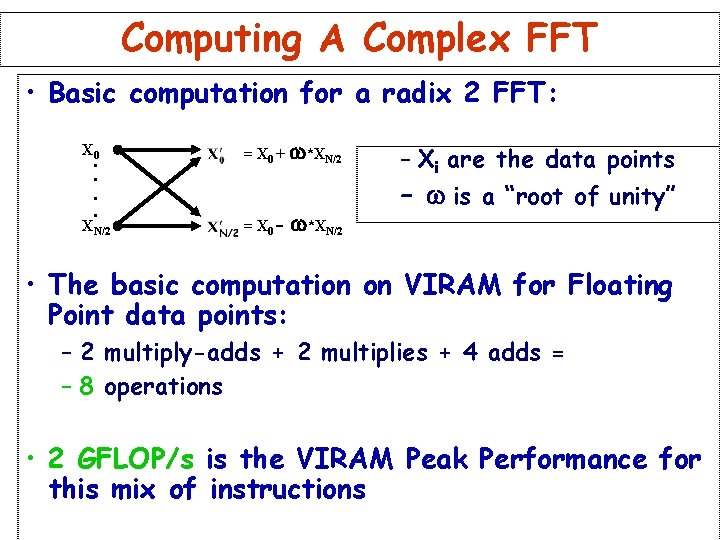

Computing A Complex FFT • Basic computation for a radix 2 FFT: X 0 = X 0 + w*XN/2 = X 0 - . . w*XN/2 – Xi are the data points – w is a “root of unity” • The basic computation on VIRAM for Floating Point data points: – 2 multiply-adds + 2 multiplies + 4 adds = – 8 operations • 2 GFLOP/s is the VIRAM Peak Performance for this mix of instructions

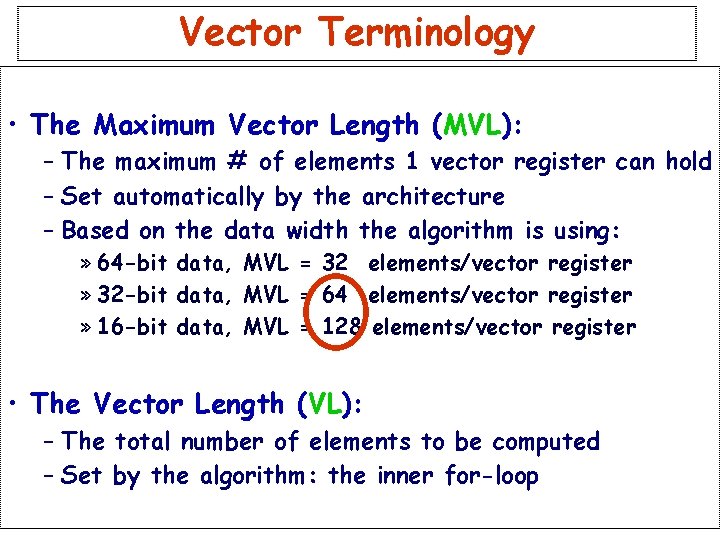

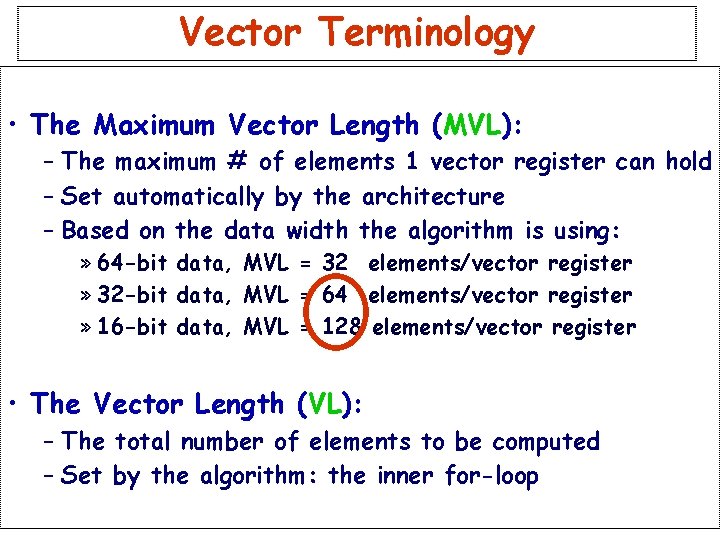

Vector Terminology • The Maximum Vector Length (MVL): – The maximum # of elements 1 vector register can hold – Set automatically by the architecture – Based on the data width the algorithm is using: » 64 -bit data, MVL = 32 elements/vector register » 32 -bit data, MVL = 64 elements/vector register » 16 -bit data, MVL = 128 elements/vector register • The Vector Length (VL): – The total number of elements to be computed – Set by the algorithm: the inner for-loop

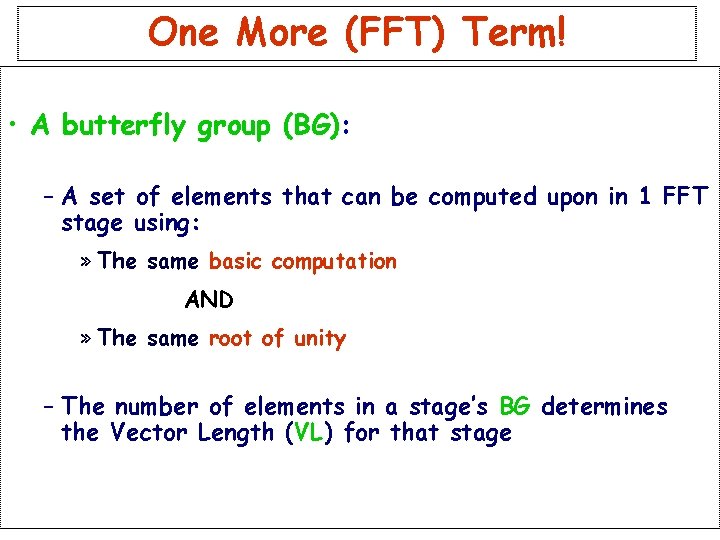

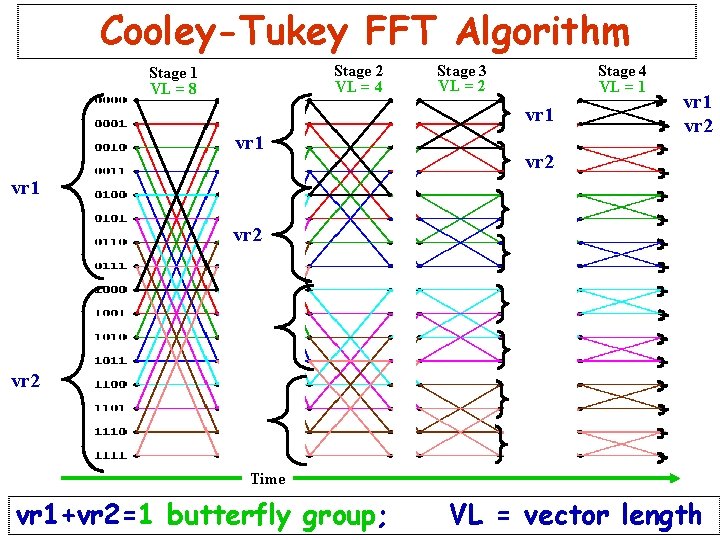

One More (FFT) Term! • A butterfly group (BG): – A set of elements that can be computed upon in 1 FFT stage using: » The same basic computation AND » The same root of unity – The number of elements in a stage’s BG determines the Vector Length (VL) for that stage

Outline • What is the FFT and Why Study it? • VIRAM Implementation Assumptions • About the FFT • The “Naïve” Algorithm • 3 Optimizations to the “Naïve” Algorithm • 32 bit Floating Point Performance Results • 16 bit Fixed Point Performance Results • Conclusions and Future Work

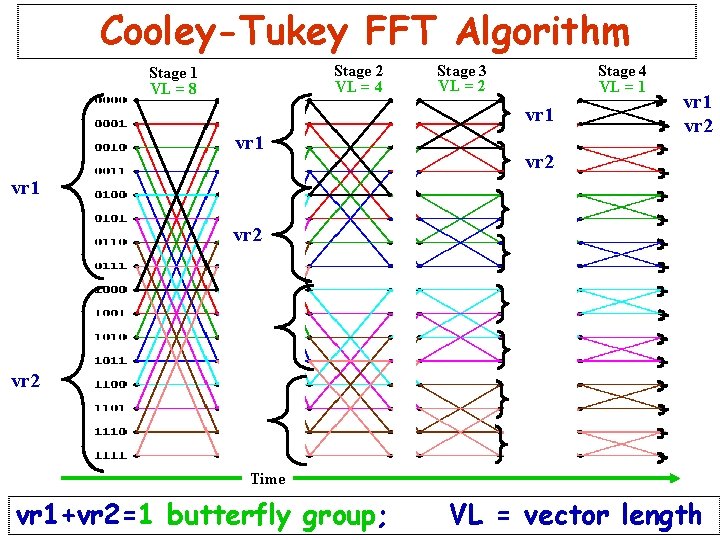

Cooley-Tukey FFT Algorithm Stage 2 VL = 4 Stage 1 VL = 8 Stage 3 VL = 2 Stage 4 VL = 1 vr 2 vr 1 vr 2 Time vr 1+vr 2=1 butterfly group; VL = vector length

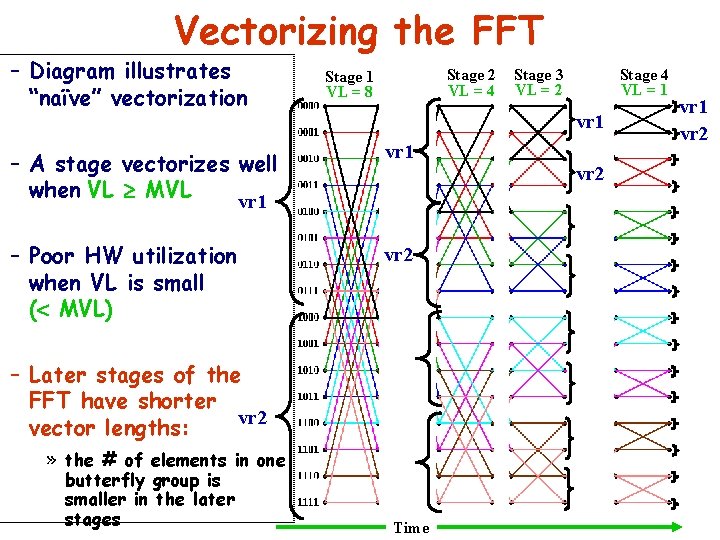

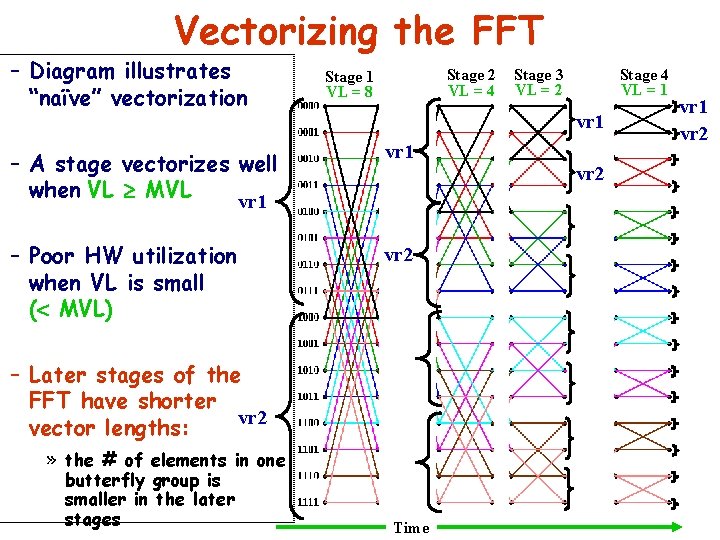

Vectorizing the FFT – Diagram illustrates “naïve” vectorization Stage 2 VL = 4 Stage 1 VL = 8 Stage 4 VL = 1 vr 1 – A stage vectorizes well when VL ³ MVL vr 1 – Poor HW utilization when VL is small (< MVL) vr 2 vr 1 – Later stages of the FFT have shorter vr 2 vector lengths: » the # of elements in one butterfly group is smaller in the later stages Stage 3 VL = 2 Time vr 2 vr 1 vr 2

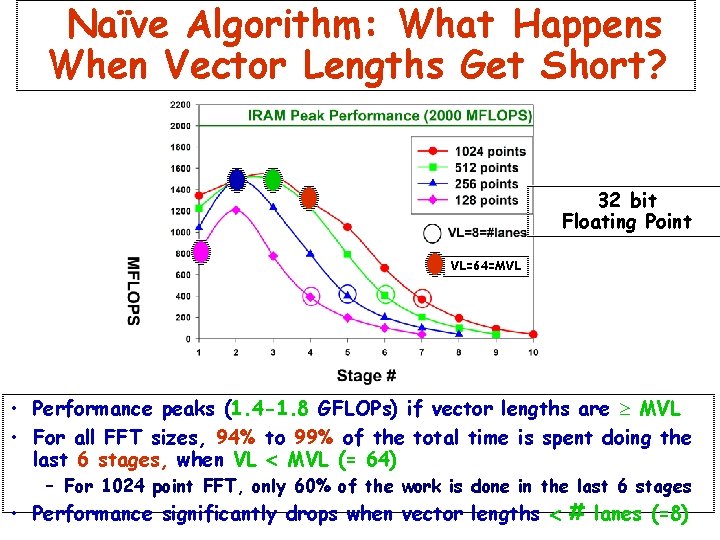

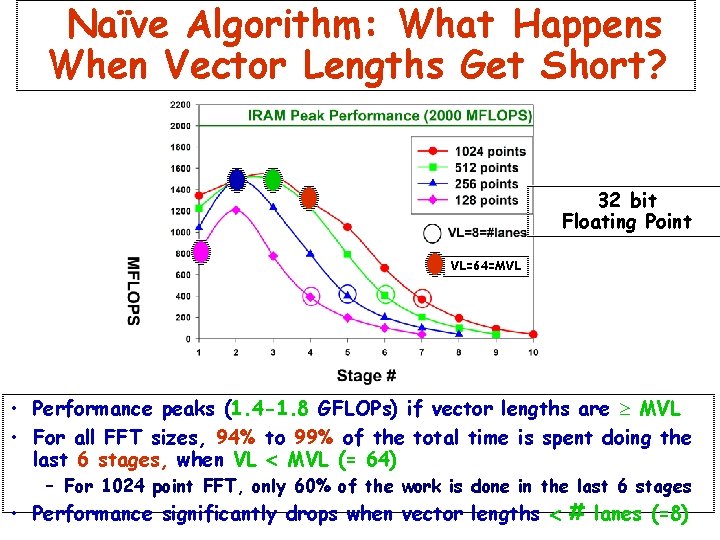

Naïve Algorithm: What Happens When Vector Lengths Get Short? 32 bit Floating Point VL=64=MVL • Performance peaks (1. 4 -1. 8 GFLOPs) if vector lengths are ³ MVL • For all FFT sizes, 94% to 99% of the total time is spent doing the last 6 stages, when VL < MVL (= 64) – For 1024 point FFT, only 60% of the work is done in the last 6 stages • Performance significantly drops when vector lengths < # lanes (=8)

Outline • What is the FFT and Why Study it? • VIRAM Implementation Assumptions • About the FFT • The “Naïve” Algorithm • 3 Optimizations to the “Naïve” Algorithm • 32 bit Floating Point Performance Results • 16 bit Fixed Point Performance Results • Conclusions and Future Work

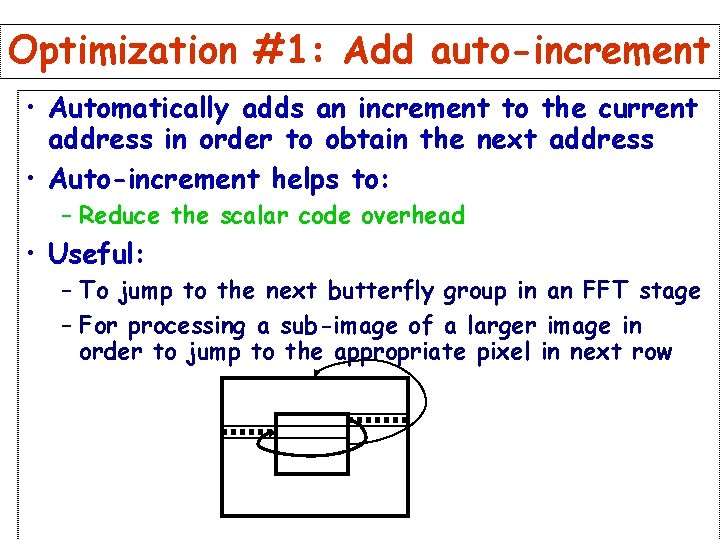

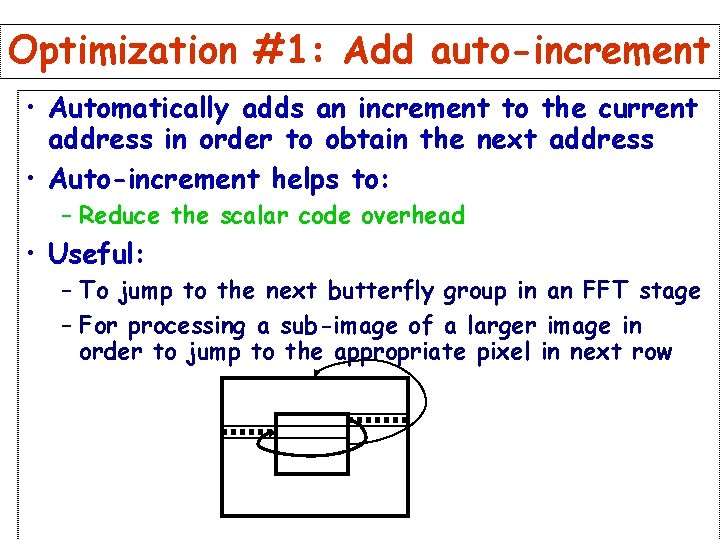

Optimization #1: Add auto-increment • Automatically adds an increment to the current address in order to obtain the next address • Auto-increment helps to: – Reduce the scalar code overhead • Useful: – To jump to the next butterfly group in an FFT stage – For processing a sub-image of a larger image in order to jump to the appropriate pixel in next row

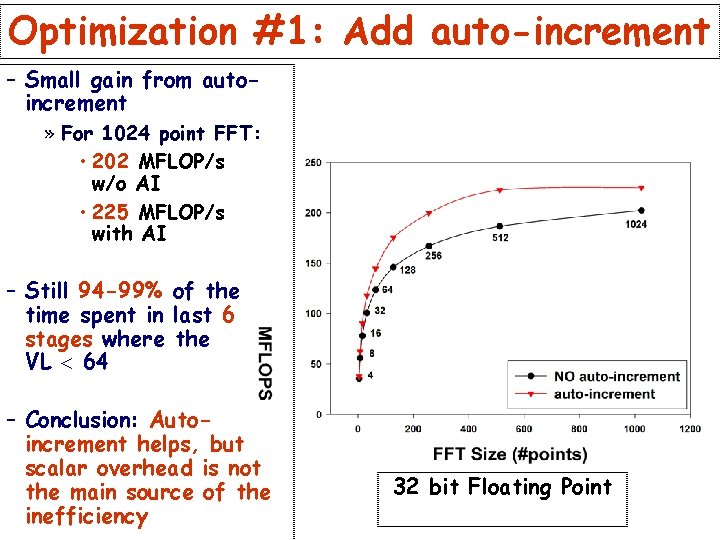

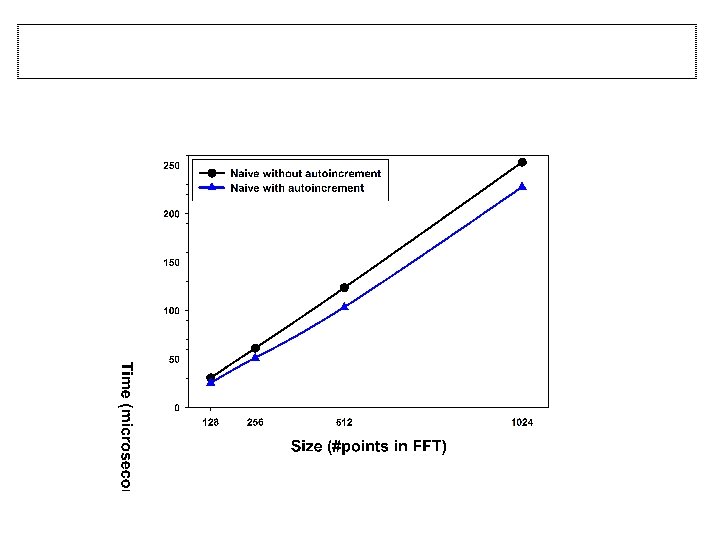

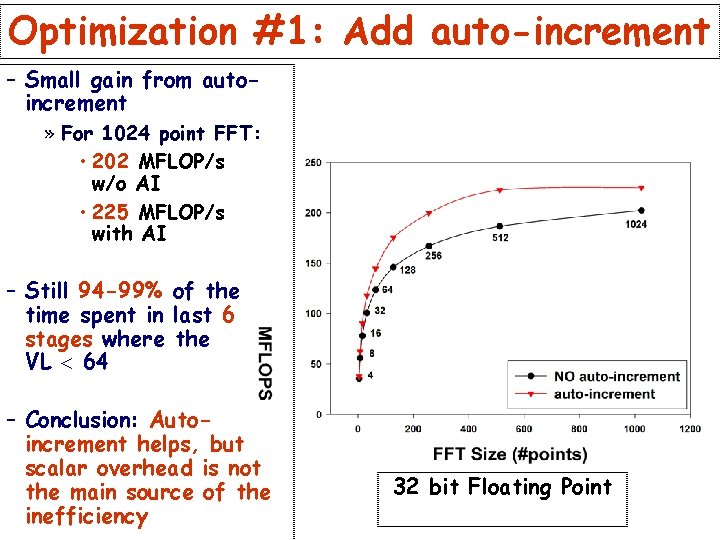

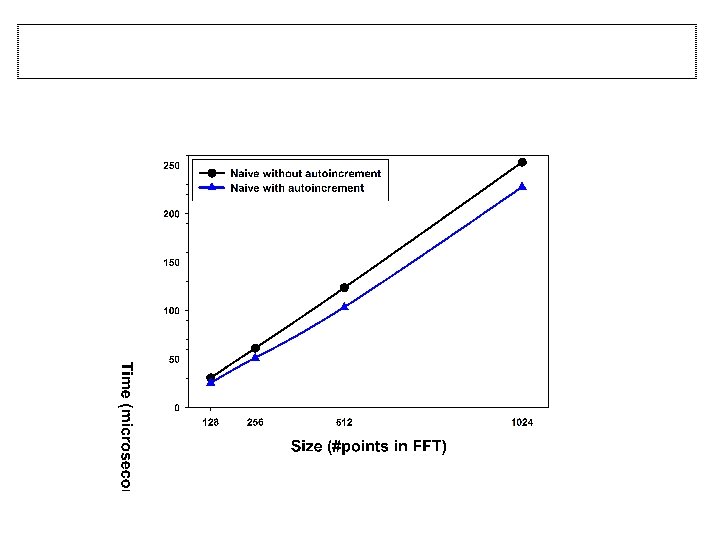

Optimization #1: Add auto-increment – Small gain from autoincrement » For 1024 point FFT: • 202 MFLOP/s w/o AI • 225 MFLOP/s with AI – Still 94 -99% of the time spent in last 6 stages where the VL < 64 – Conclusion: Autoincrement helps, but scalar overhead is not the main source of the inefficiency 32 bit Floating Point

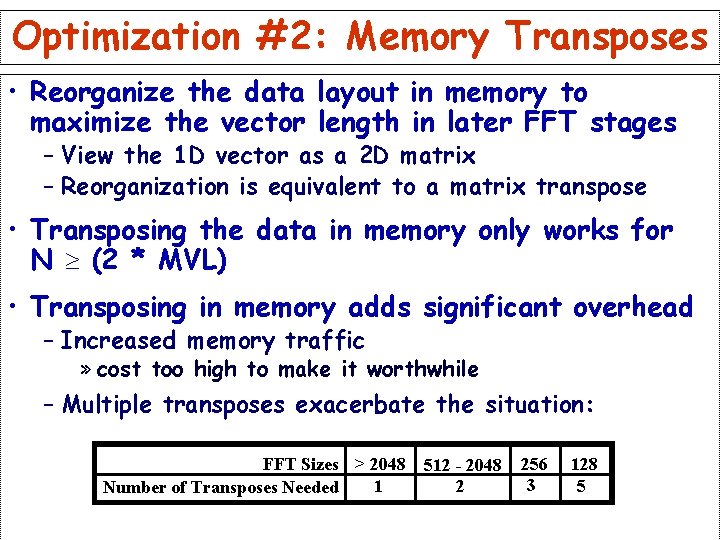

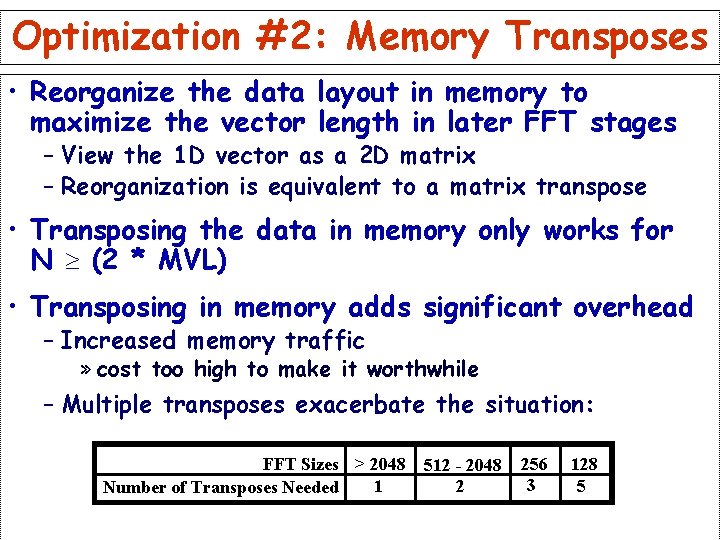

Optimization #2: Memory Transposes • Reorganize the data layout in memory to maximize the vector length in later FFT stages – View the 1 D vector as a 2 D matrix – Reorganization is equivalent to a matrix transpose • Transposing the data in memory only works for N ³ (2 * MVL) • Transposing in memory adds significant overhead – Increased memory traffic » cost too high to make it worthwhile – Multiple transposes exacerbate the situation: FFT Sizes > 2048 512 - 2048 1 2 Number of Transposes Needed 256 3 128 5

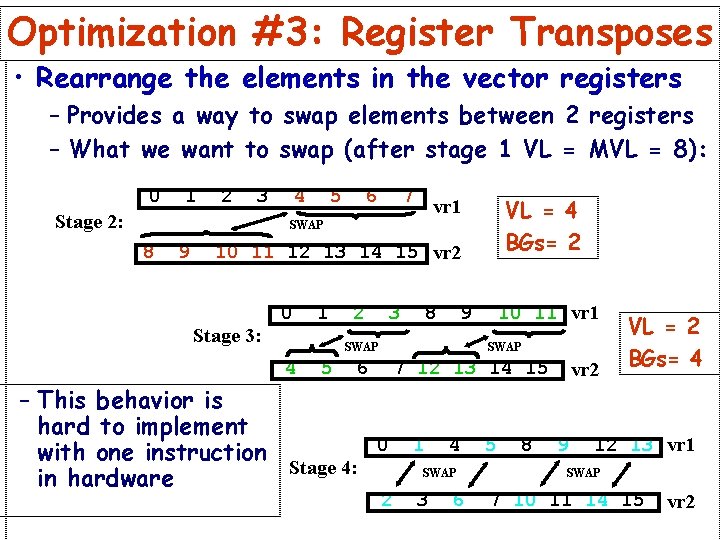

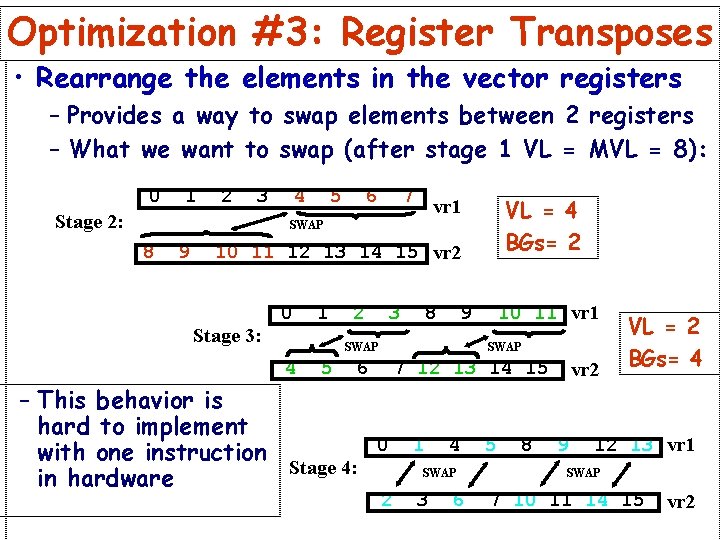

Optimization #3: Register Transposes • Rearrange the elements in the vector registers – Provides a way to swap elements between 2 registers – What we want to swap (after stage 1 VL = MVL = 8): 0 1 2 3 Stage 2: 4 5 6 7 VL = 4 BGs= 2 vr 1 SWAP 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 vr 2 Stage 3: 0 1 2 3 8 9 SWAP 4 5 10 11 vr 1 SWAP 6 7 12 13 14 15 vr 2 VL = 2 BGs= 4 – This behavior is hard to implement 0 1 4 5 8 9 12 13 vr 1 with one instruction Stage 4: SWAP in hardware 2 3 6 7 10 11 14 15 vr 2

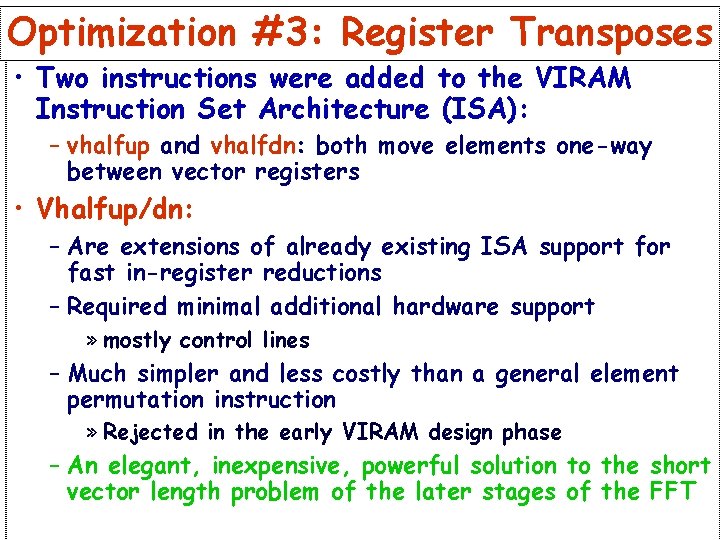

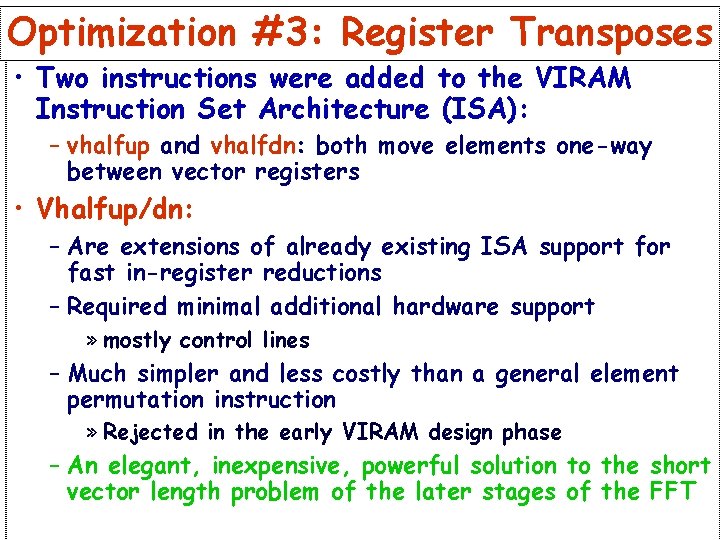

Optimization #3: Register Transposes • Two instructions were added to the VIRAM Instruction Set Architecture (ISA): – vhalfup and vhalfdn: both move elements one-way between vector registers • Vhalfup/dn: – Are extensions of already existing ISA support for fast in-register reductions – Required minimal additional hardware support » mostly control lines – Much simpler and less costly than a general element permutation instruction » Rejected in the early VIRAM design phase – An elegant, inexpensive, powerful solution to the short vector length problem of the later stages of the FFT

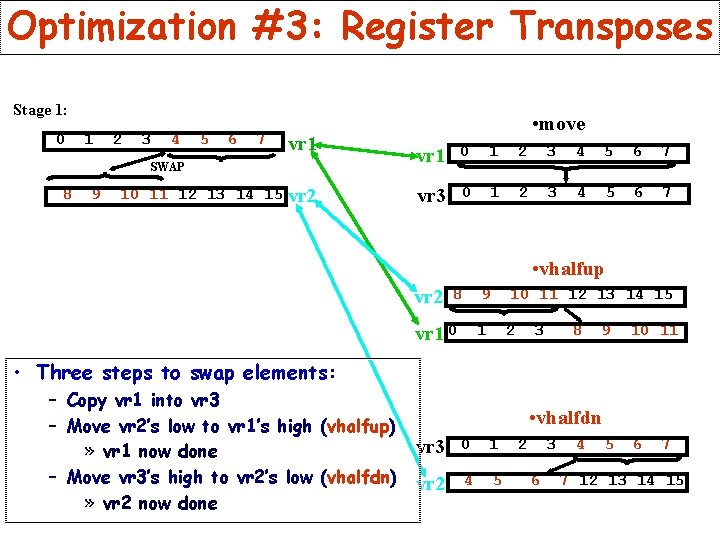

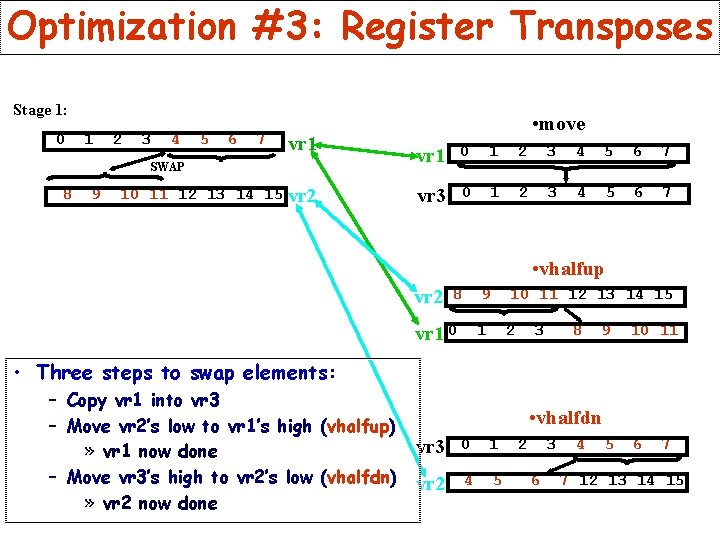

Optimization #3: Register Transposes Stage 1: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 vr 1 SWAP 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 vr 2 • move vr 1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 vr 3 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 • vhalfup vr 2 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 vr 1 0 1 2 3 8 9 10 11 5 6 • Three steps to swap elements: – Copy vr 1 into vr 3 – Move vr 2’s low to vr 1’s high (vhalfup) » vr 1 now done – Move vr 3’s high to vr 2’s low (vhalfdn) » vr 2 now done • vhalfdn vr 3 0 1 vr 2 4 5 2 3 6 4 7 7 12 13 14 15

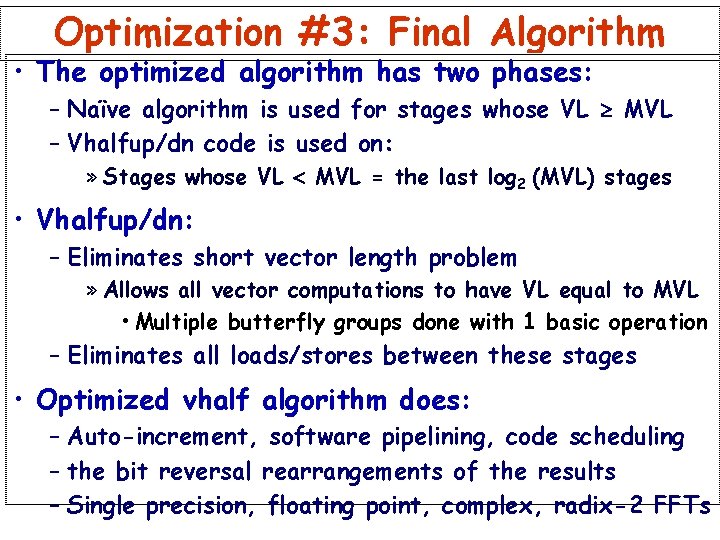

Optimization #3: Final Algorithm • The optimized algorithm has two phases: – Naïve algorithm is used for stages whose VL ³ MVL – Vhalfup/dn code is used on: » Stages whose VL < MVL = the last log 2 (MVL) stages • Vhalfup/dn: – Eliminates short vector length problem » Allows all vector computations to have VL equal to MVL • Multiple butterfly groups done with 1 basic operation – Eliminates all loads/stores between these stages • Optimized vhalf algorithm does: – Auto-increment, software pipelining, code scheduling – the bit reversal rearrangements of the results – Single precision, floating point, complex, radix-2 FFTs

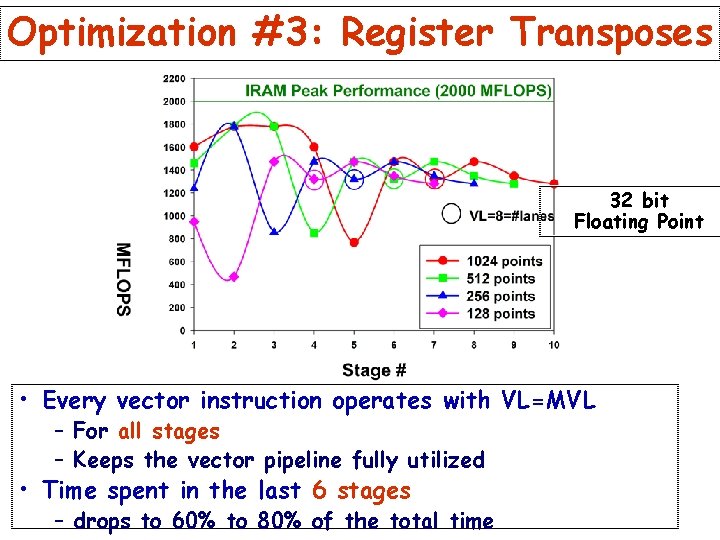

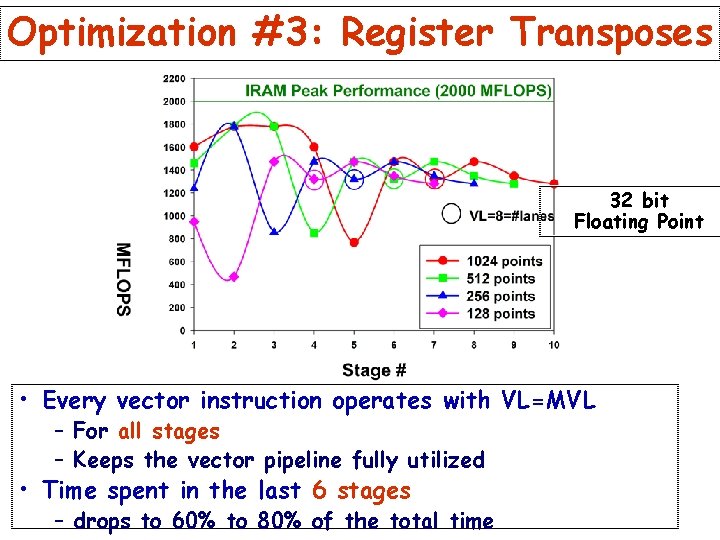

Optimization #3: Register Transposes 32 bit Floating Point • Every vector instruction operates with VL=MVL – For all stages – Keeps the vector pipeline fully utilized • Time spent in the last 6 stages – drops to 60% to 80% of the total time

Outline • What is the FFT and Why Study it? • VIRAM Implementation Assumptions • About the FFT • The “Naïve” Algorithm • 3 Optimizations to the “Naïve” Algorithm • 32 bit Floating Point Performance Results • 16 bit Fixed Point Performance Results • Conclusions and Future Work

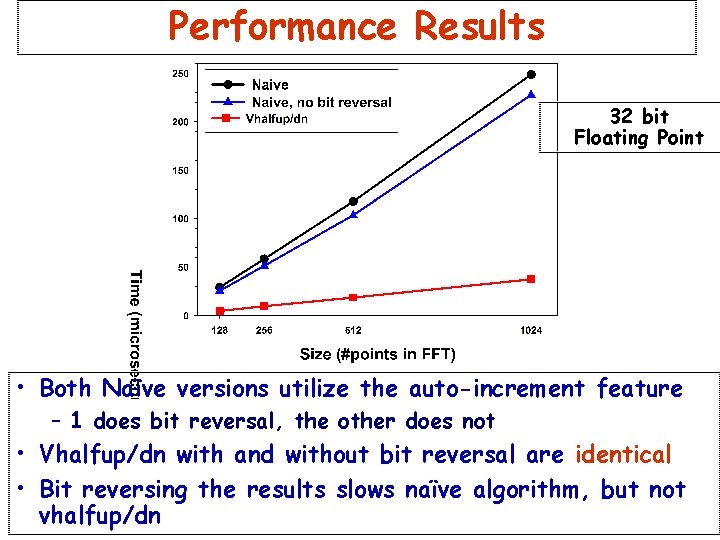

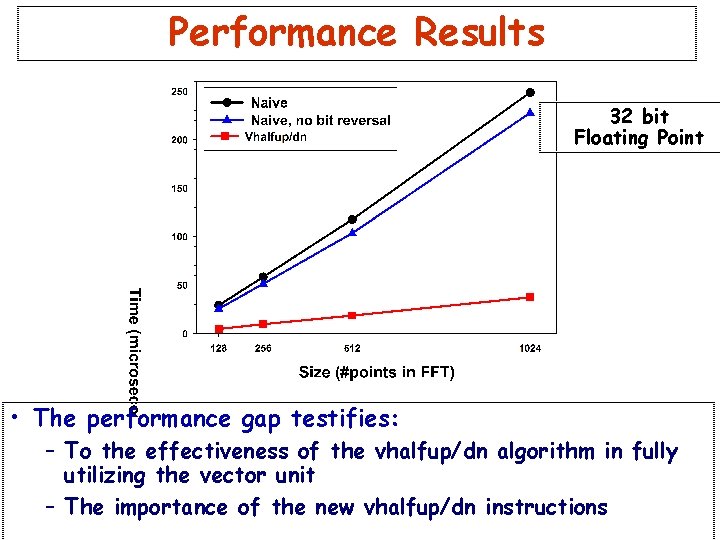

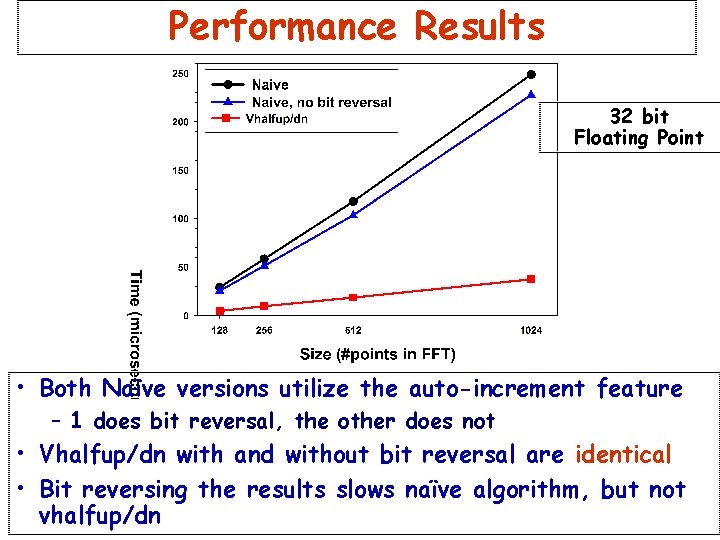

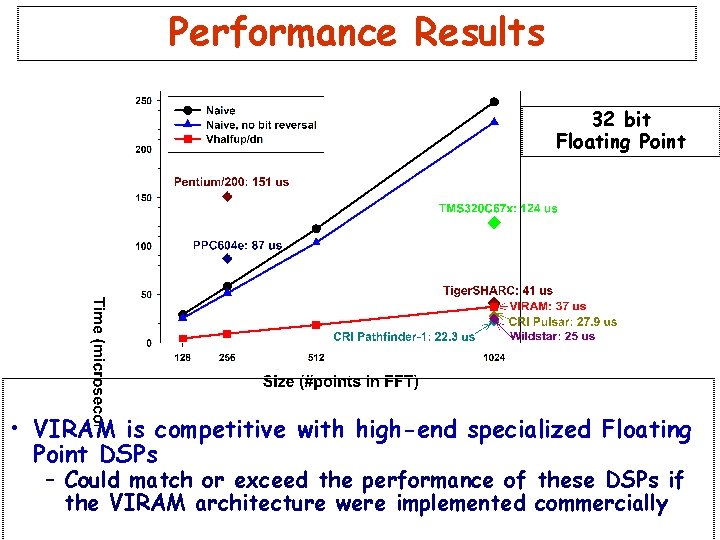

Performance Results 32 bit Floating Point • Both Naïve versions utilize the auto-increment feature – 1 does bit reversal, the other does not • Vhalfup/dn with and without bit reversal are identical • Bit reversing the results slows naïve algorithm, but not vhalfup/dn

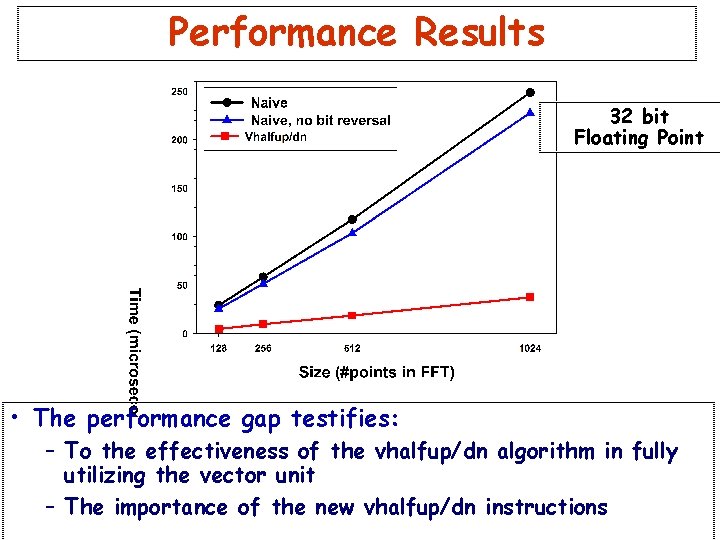

Performance Results 32 bit Floating Point • The performance gap testifies: – To the effectiveness of the vhalfup/dn algorithm in fully utilizing the vector unit – The importance of the new vhalfup/dn instructions

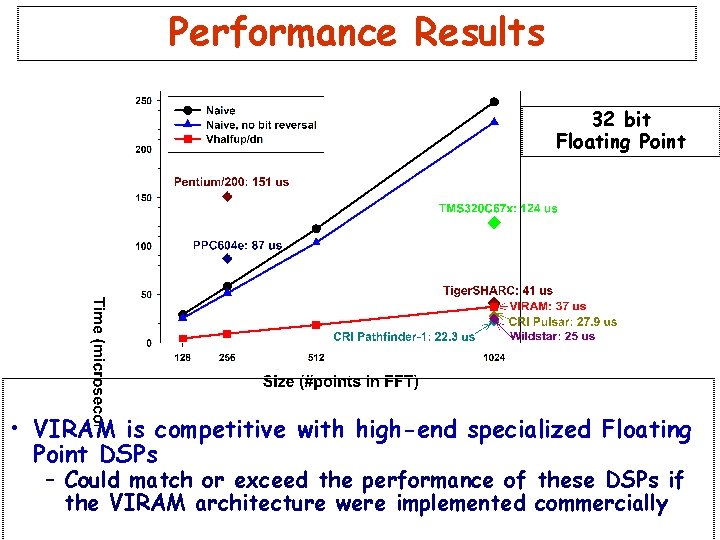

Performance Results 32 bit Floating Point • VIRAM is competitive with high-end specialized Floating Point DSPs – Could match or exceed the performance of these DSPs if the VIRAM architecture were implemented commercially

Outline • What is the FFT and Why Study it? • VIRAM Implementation Assumptions • About the FFT • The “Naïve” Algorithm • 3 Optimizations to the “Naïve” Algorithm • 32 bit Floating Point Performance Results • 16 bit Fixed Point Performance Results • Conclusions and Future Work

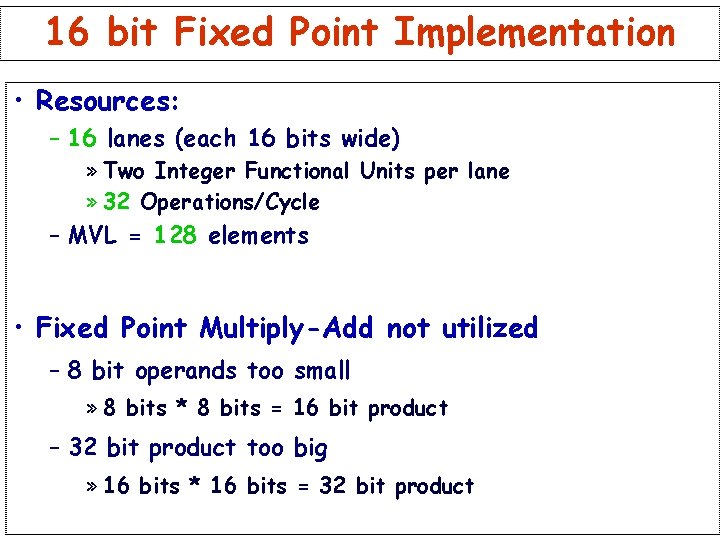

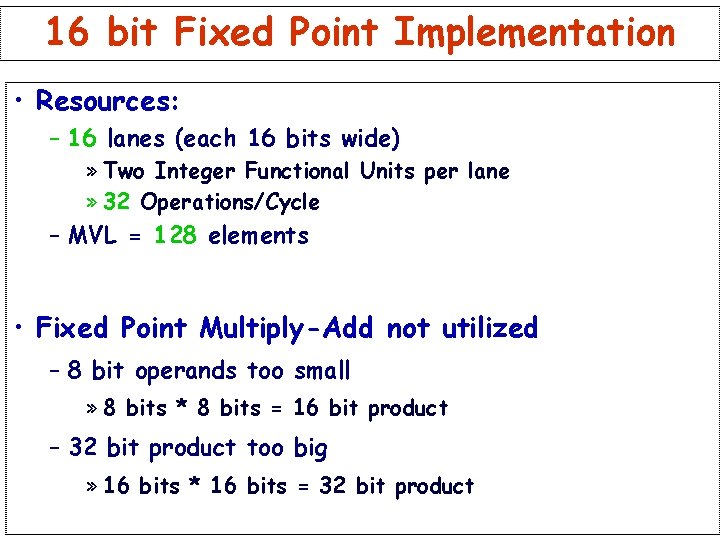

16 bit Fixed Point Implementation • Resources: – 16 lanes (each 16 bits wide) » Two Integer Functional Units per lane » 32 Operations/Cycle – MVL = 128 elements • Fixed Point Multiply-Add not utilized – 8 bit operands too small » 8 bits * 8 bits = 16 bit product – 32 bit product too big » 16 bits * 16 bits = 32 bit product

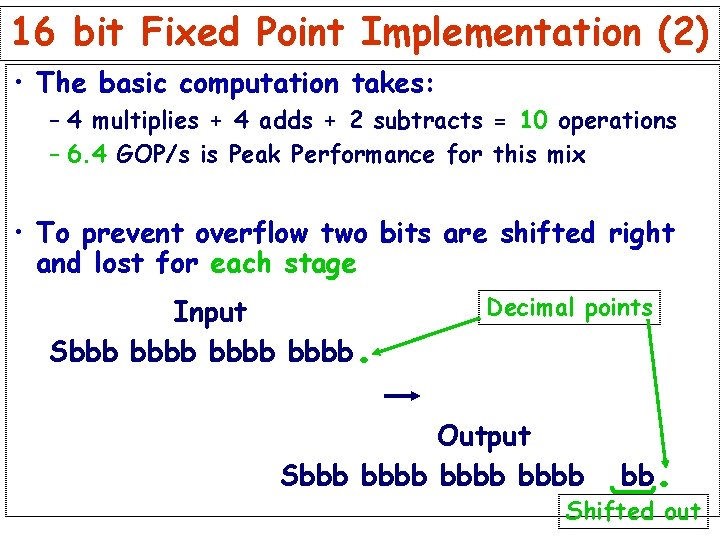

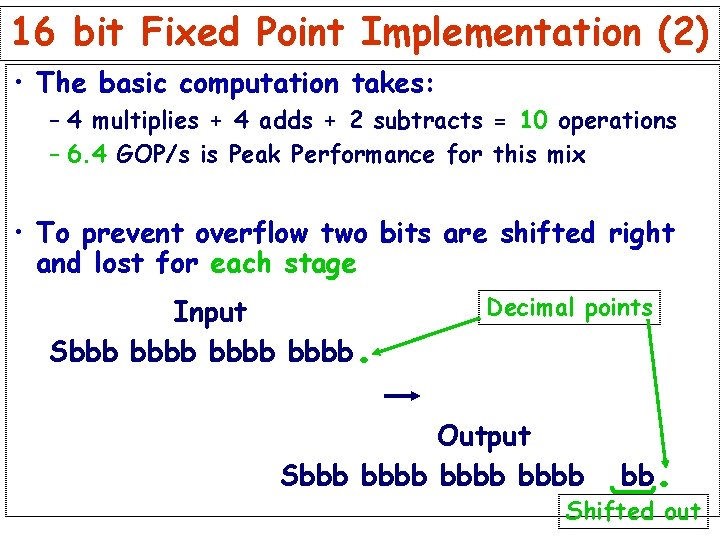

16 bit Fixed Point Implementation (2) • The basic computation takes: – 4 multiplies + 4 adds + 2 subtracts = 10 operations – 6. 4 GOP/s is Peak Performance for this mix • To prevent overflow two bits are shifted right and lost for each stage Input Sbbb bbbb . Decimal points Output Sbbb bbbb bb . Shifted out

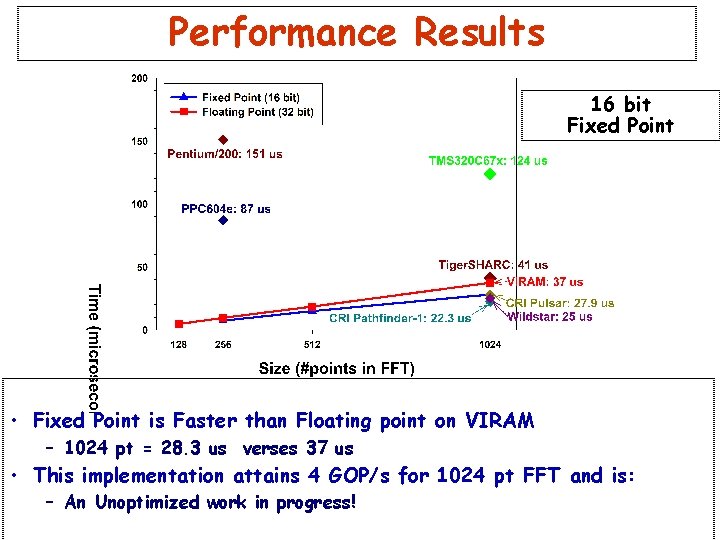

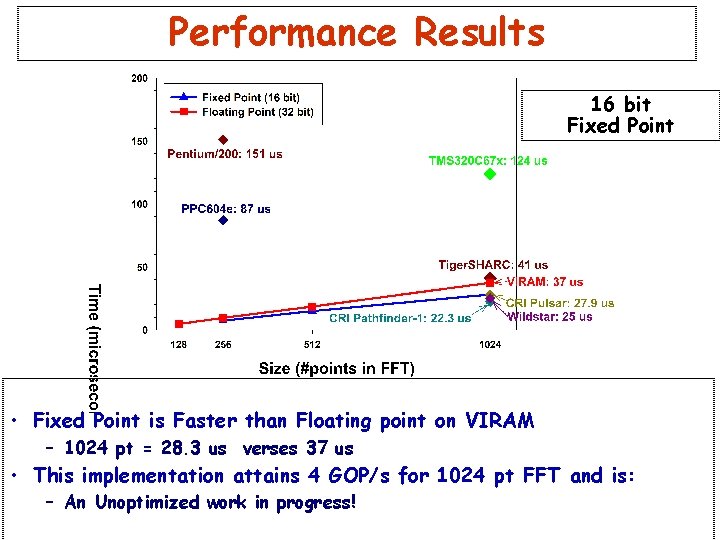

Performance Results 16 bit Fixed Point • Fixed Point is Faster than Floating point on VIRAM – 1024 pt = 28. 3 us verses 37 us • This implementation attains 4 GOP/s for 1024 pt FFT and is: – An Unoptimized work in progress!

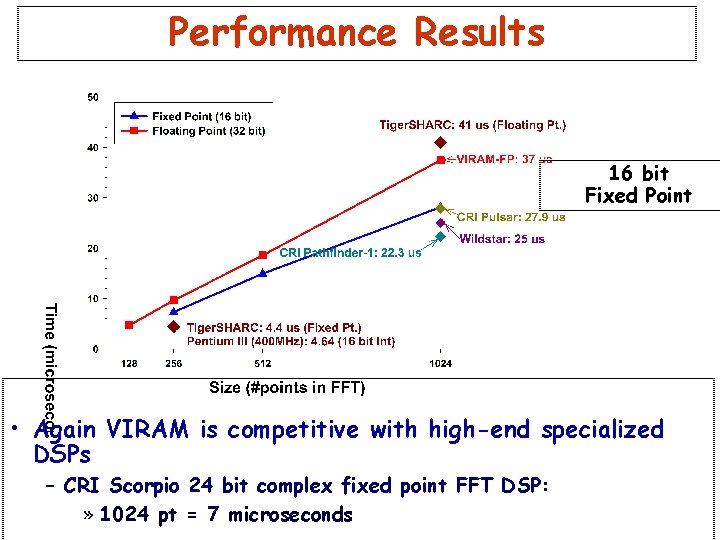

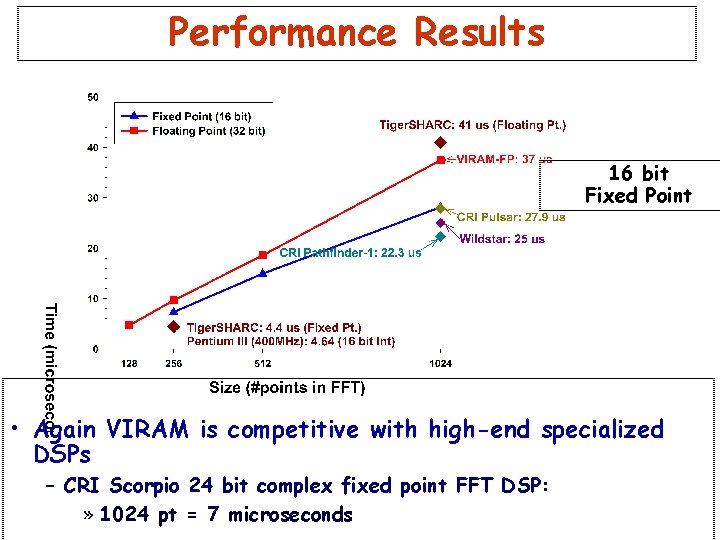

Performance Results 16 bit Fixed Point • Again VIRAM is competitive with high-end specialized DSPs – CRI Scorpio 24 bit complex fixed point FFT DSP: » 1024 pt = 7 microseconds

Outline • What is the FFT and Why Study it? • VIRAM Implementation Assumptions • About the FFT • The “Naïve” Algorithm • 3 Optimizations to the “Naïve” Algorithm • 32 bit Floating Point Performance Results • 16 bit Fixed Point Performance Results • Conclusions and Future Work

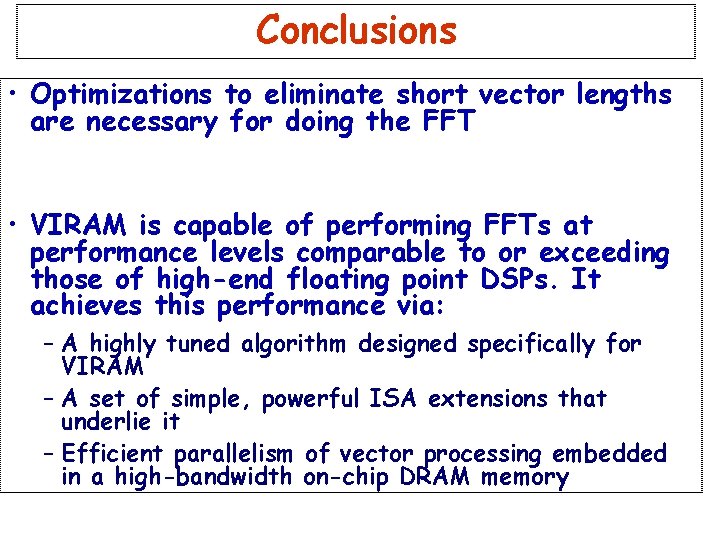

Conclusions • Optimizations to eliminate short vector lengths are necessary for doing the FFT • VIRAM is capable of performing FFTs at performance levels comparable to or exceeding those of high-end floating point DSPs. It achieves this performance via: – A highly tuned algorithm designed specifically for VIRAM – A set of simple, powerful ISA extensions that underlie it – Efficient parallelism of vector processing embedded in a high-bandwidth on-chip DRAM memory

Conclusions (2) • Performance of FFTs on VIRAM has the potential to improve significantly over the results presented here: – 32 -bit fixed point FFTs could run up to 2 times faster than floating point versions – Compared to 32 -bit fixed point FFTs, 16 -bit fixed point FFTs could run up to: » 8 x faster (with multiply-add ops) » 4 x faster (with no multiply-add ops) – Adding a second Floating Point Functional Unit would make floating point performance comparable to the 32 -bit Fixed Point performance. – 4 GOP/s for Unoptimized Fixed Point implementation (6. 4 GOP/s is peak!)

Conclusions (3) • Since VIRAM includes both general-purpose CPU capability and DSP muscle, it shares the same space in the emerging market of hybrid CPU/DSPs as: – Infineon Tri. Core – Hitachi Super. H-DSP – Motorola/Lucent Star. Core – Motorola Power. PC G 4 (7400) • VIRAM’s vector processor plus embedded DRAM design may have further advantages over more traditional processors in: – Power – Area – Performance

Future Work • On Current Fixed Point implementation: – Further optimizations and tests • Explore the tradeoffs between precision & accuracy and Performance by implementing: – A Hybrid of the current implementation which alternates the number of bits shifted off each stage » 2 1 1 1. . . – A 32 bit integer version which uses 16 bit data » If data occupies the 16 most significant bits of the 32 bits, then there are 16 zeros to shift off: Sbbb bbbb b 0000 0000

Backup Slides

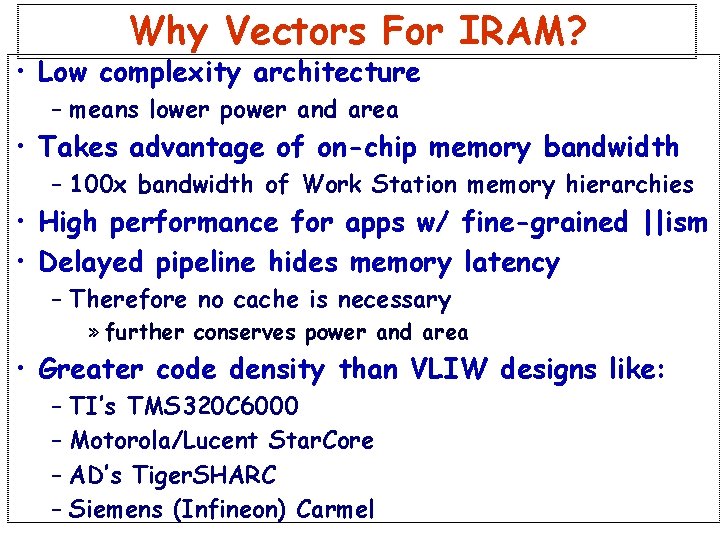

Why Vectors For IRAM? • Low complexity architecture – means lower power and area • Takes advantage of on-chip memory bandwidth – 100 x bandwidth of Work Station memory hierarchies • High performance for apps w/ fine-grained ||ism • Delayed pipeline hides memory latency – Therefore no cache is necessary » further conserves power and area • Greater code density than VLIW designs like: – TI’s TMS 320 C 6000 – Motorola/Lucent Star. Core – AD’s Tiger. SHARC – Siemens (Infineon) Carmel