Effect of Elementary School Library Checkout Policies on

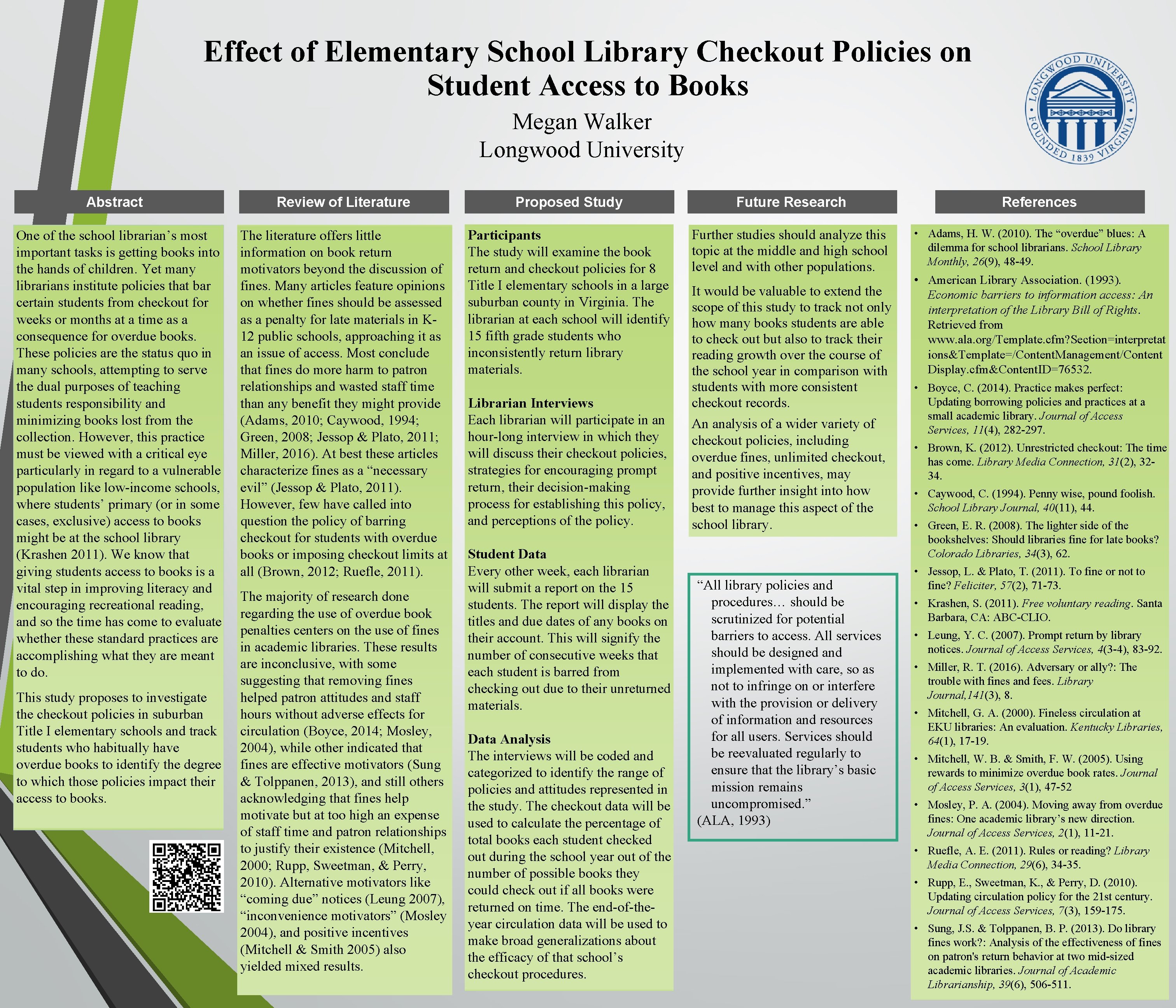

Effect of Elementary School Library Checkout Policies on Student Access to Books Megan Walker Longwood University Abstract One of the school librarian’s most important tasks is getting books into the hands of children. Yet many librarians institute policies that bar certain students from checkout for weeks or months at a time as a consequence for overdue books. These policies are the status quo in many schools, attempting to serve the dual purposes of teaching students responsibility and minimizing books lost from the collection. However, this practice must be viewed with a critical eye particularly in regard to a vulnerable population like low-income schools, where students’ primary (or in some cases, exclusive) access to books might be at the school library (Krashen 2011). We know that giving students access to books is a vital step in improving literacy and encouraging recreational reading, and so the time has come to evaluate whether these standard practices are accomplishing what they are meant to do. This study proposes to investigate the checkout policies in suburban Title I elementary schools and track students who habitually have overdue books to identify the degree to which those policies impact their access to books. Review of Literature Proposed Study Future Research The literature offers little information on book return motivators beyond the discussion of fines. Many articles feature opinions on whether fines should be assessed as a penalty for late materials in K 12 public schools, approaching it as an issue of access. Most conclude that fines do more harm to patron relationships and wasted staff time than any benefit they might provide (Adams, 2010; Caywood, 1994; Green, 2008; Jessop & Plato, 2011; Miller, 2016). At best these articles characterize fines as a “necessary evil” (Jessop & Plato, 2011). However, few have called into question the policy of barring checkout for students with overdue books or imposing checkout limits at all (Brown, 2012; Ruefle, 2011). Participants The study will examine the book return and checkout policies for 8 Title I elementary schools in a large suburban county in Virginia. The librarian at each school will identify 15 fifth grade students who inconsistently return library materials. Further studies should analyze this topic at the middle and high school level and with other populations. • Adams, H. W. (2010). The “overdue” blues: A dilemma for school librarians. School Library Monthly, 26(9), 48 -49. It would be valuable to extend the scope of this study to track not only how many books students are able to check out but also to track their reading growth over the course of the school year in comparison with students with more consistent checkout records. An analysis of a wider variety of checkout policies, including overdue fines, unlimited checkout, and positive incentives, may provide further insight into how best to manage this aspect of the school library. • Boyce, C. (2014). Practice makes perfect: Updating borrowing policies and practices at a small academic library. Journal of Access Services, 11(4), 282 -297. The majority of research done regarding the use of overdue book penalties centers on the use of fines in academic libraries. These results are inconclusive, with some suggesting that removing fines helped patron attitudes and staff hours without adverse effects for circulation (Boyce, 2014; Mosley, 2004), while other indicated that fines are effective motivators (Sung & Tolppanen, 2013), and still others acknowledging that fines help motivate but at too high an expense of staff time and patron relationships to justify their existence (Mitchell, 2000; Rupp, Sweetman, & Perry, 2010). Alternative motivators like “coming due” notices (Leung 2007), “inconvenience motivators” (Mosley 2004), and positive incentives (Mitchell & Smith 2005) also yielded mixed results. Librarian Interviews Each librarian will participate in an hour-long interview in which they will discuss their checkout policies, strategies for encouraging prompt return, their decision-making process for establishing this policy, and perceptions of the policy. Student Data Every other week, each librarian will submit a report on the 15 students. The report will display the titles and due dates of any books on their account. This will signify the number of consecutive weeks that each student is barred from checking out due to their unreturned materials. Data Analysis The interviews will be coded and categorized to identify the range of policies and attitudes represented in the study. The checkout data will be used to calculate the percentage of total books each student checked out during the school year out of the number of possible books they could check out if all books were returned on time. The end-of-theyear circulation data will be used to make broad generalizations about the efficacy of that school’s checkout procedures. “All library policies and procedures… should be scrutinized for potential barriers to access. All services should be designed and implemented with care, so as not to infringe on or interfere with the provision or delivery of information and resources for all users. Services should be reevaluated regularly to ensure that the library’s basic mission remains uncompromised. ” (ALA, 1993) References • American Library Association. (1993). Economic barriers to information access: An interpretation of the Library Bill of Rights. Retrieved from www. ala. org/Template. cfm? Section=interpretat ions&Template=/Content. Management/Content Display. cfm&Content. ID=76532. • Brown, K. (2012). Unrestricted checkout: The time has come. Library Media Connection, 31(2), 3234. • Caywood, C. (1994). Penny wise, pound foolish. School Library Journal, 40(11), 44. • Green, E. R. (2008). The lighter side of the bookshelves: Should libraries fine for late books? Colorado Libraries, 34(3), 62. • Jessop, L. & Plato, T. (2011). To fine or not to fine? Feliciter, 57(2), 71 -73. • Krashen, S. (2011). Free voluntary reading. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. • Leung, Y. C. (2007). Prompt return by library notices. Journal of Access Services, 4(3 -4), 83 -92. • Miller, R. T. (2016). Adversary or ally? : The trouble with fines and fees. Library Journal, 141(3), 8. • Mitchell, G. A. (2000). Fineless circulation at EKU libraries: An evaluation. Kentucky Libraries, 64(1), 17 -19. • Mitchell, W. B. & Smith, F. W. (2005). Using rewards to minimize overdue book rates. Journal of Access Services, 3(1), 47 -52 • Mosley, P. A. (2004). Moving away from overdue fines: One academic library’s new direction. Journal of Access Services, 2(1), 11 -21. • Ruefle, A. E. (2011). Rules or reading? Library Media Connection, 29(6), 34 -35. • Rupp, E. , Sweetman, K. , & Perry, D. (2010). Updating circulation policy for the 21 st century. Journal of Access Services, 7(3), 159 -175. • Sung, J. S. & Tolppanen, B. P. (2013). Do library fines work? : Analysis of the effectiveness of fines on patron's return behavior at two mid-sized academic libraries. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 39(6), 506 -511.

- Slides: 1