EECS 647 Introduction to Database Systems Instructor Luke

EECS 647: Introduction to Database Systems Instructor: Luke Huan Spring 2007

Administrative l l Homework 4 is due today Homework 5 is assigned today, it is due April 23. 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 2

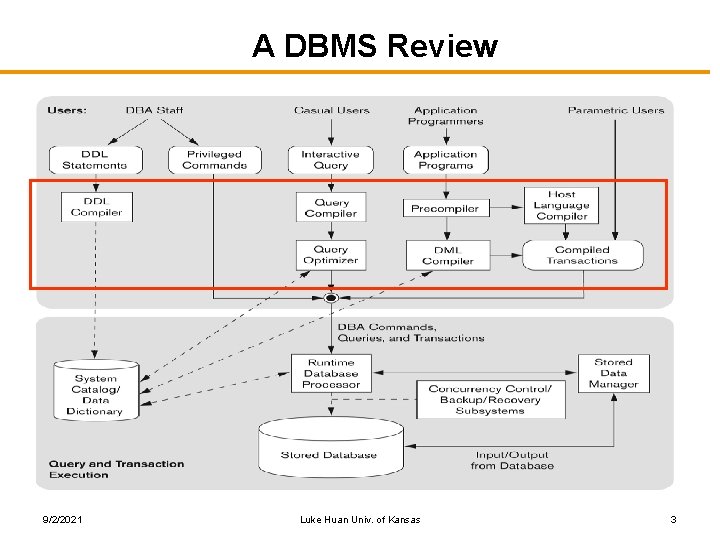

A DBMS Review 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 3

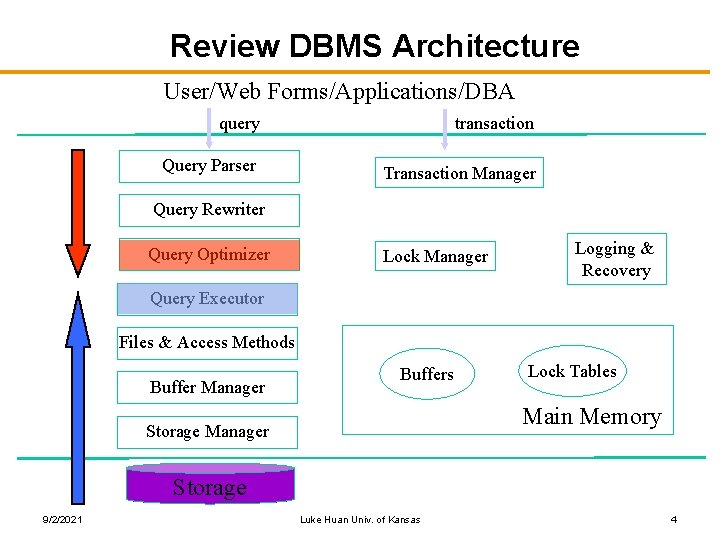

Review DBMS Architecture User/Web Forms/Applications/DBA query transaction Query Parser Transaction Manager Query Rewriter Query Optimizer Lock Manager Logging & Recovery Query Executor Files & Access Methods Buffer Manager Buffers Lock Tables Main Memory Storage Manager Storage 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 4

Review Operators in QP l Logical operators: l l Physical operators: l l what they do how they do it Exercise: L: logical operator, P: physical operator l l Union Join Nested loop join Sort-merge join 9/2/2021 L L P P Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 5

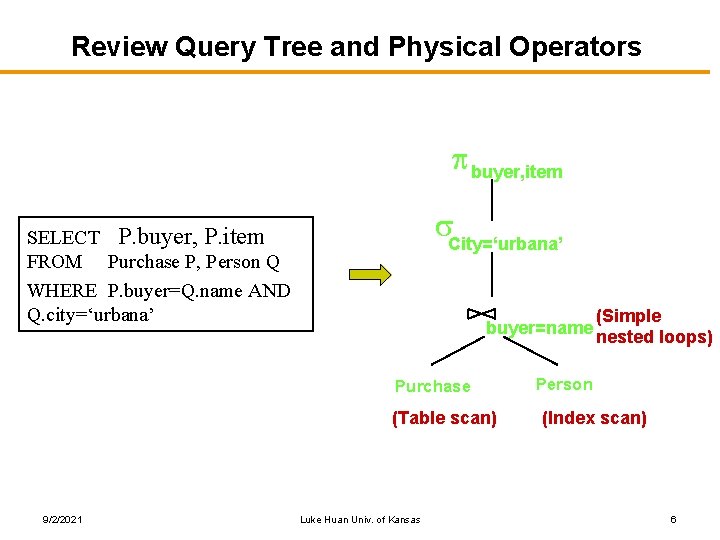

Review Query Tree and Physical Operators buyer, item City=‘urbana’ SELECT P. buyer, P. item FROM Purchase P, Person Q WHERE P. buyer=Q. name AND Q. city=‘urbana’ buyer=name Purchase (Table scan) 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas (Simple nested loops) Person (Index scan) 6

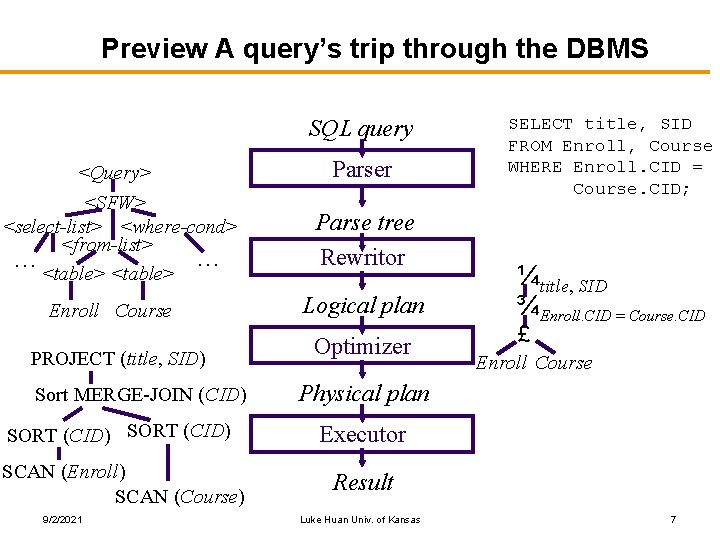

Preview A query’s trip through the DBMS SQL query <Query> <SFW> <select-list> <where-cond> <from-list> … … <table> Enroll Course PROJECT (title, SID) Sort MERGE-JOIN (CID) Parser Parse tree Rewritor Logical plan Optimizer ¼title, SID ¾Enroll. CID = Course. CID £ Enroll Course Physical plan SORT (CID) Executor SCAN (Enroll) SCAN (Course) Result 9/2/2021 SELECT title, SID FROM Enroll, Course WHERE Enroll. CID = Course. CID; Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 7

Today’s Topic l A system view of DBMS query processing process l l l Parser Rewriter Optimizer Executor Query optimization l l Heuristic based methods Cost based methods 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 8

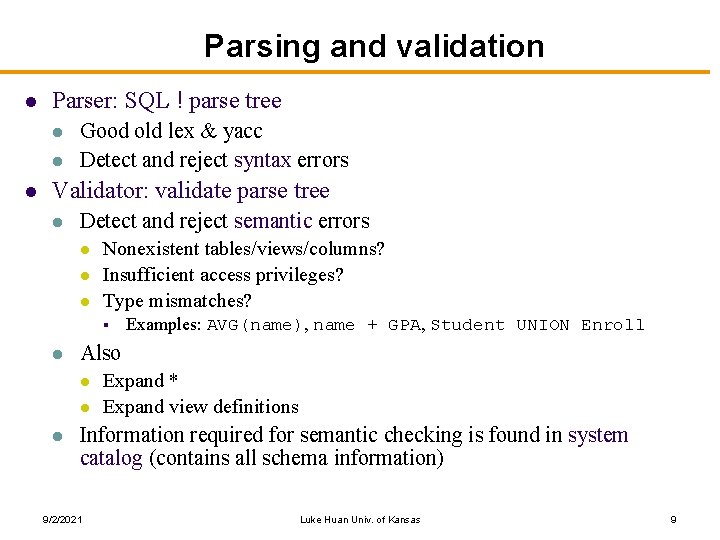

Parsing and validation l Parser: SQL ! parse tree l l l Good old lex & yacc Detect and reject syntax errors Validator: validate parse tree l Detect and reject semantic errors l l l Nonexistent tables/views/columns? Insufficient access privileges? Type mismatches? § l Also l l l Examples: AVG(name), name + GPA, Student UNION Enroll Expand * Expand view definitions Information required for semantic checking is found in system catalog (contains all schema information) 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 9

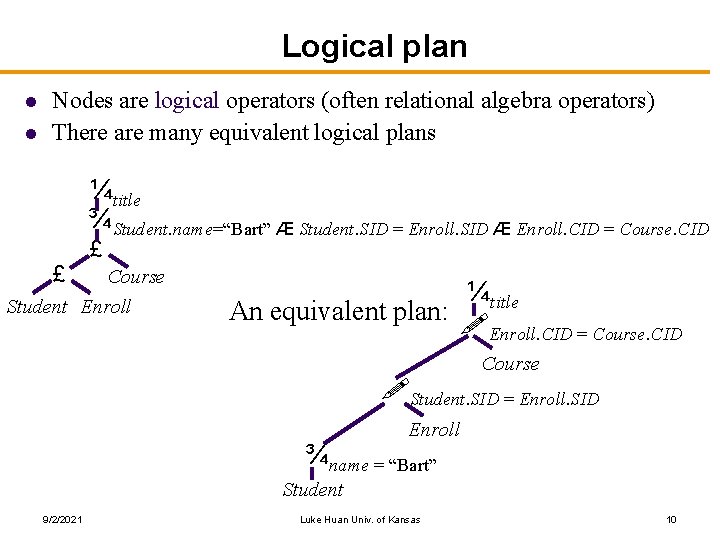

Logical plan l l Nodes are logical operators (often relational algebra operators) There are many equivalent logical plans ¼title ¾Student. name=“Bart” Æ Student. SID = Enroll. SID Æ Enroll. CID = Course. CID £ £ Course Student Enroll ¼title An equivalent plan: ! Enroll. CID = Course. CID Course !Student. SID = Enroll. SID Enroll ¾name = “Bart” Student 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 10

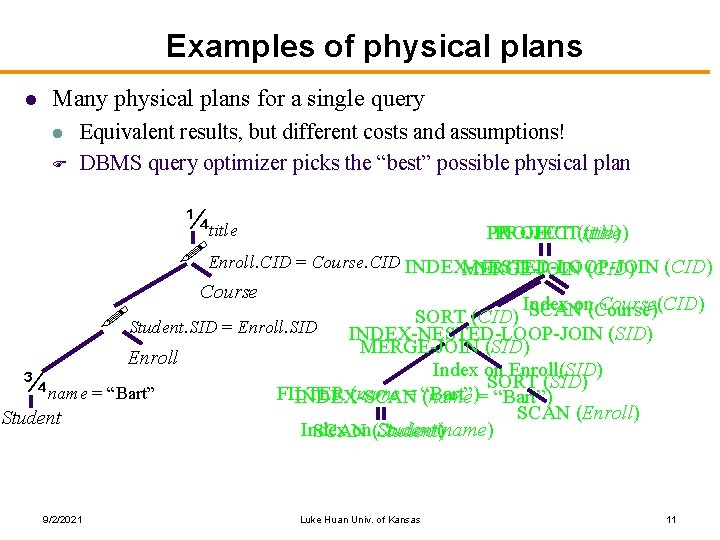

Examples of physical plans l Many physical plans for a single query l F Equivalent results, but different costs and assumptions! DBMS query optimizer picks the “best” possible physical plan ¼title PROJECT(title) !Enroll. CID = Course. CID INDEX-NESTED-LOOP-JOIN MERGE-JOIN (CID) Course Index Course(CID) SCANon(Course) SORT (CID) !Student. SID = Enroll. SID INDEX-NESTED-LOOP-JOIN (SID) MERGE-JOIN (SID) Enroll Index on Enroll(SID) SORT (SID) ¾name = “Bart” FILTER (name = “Bart”) INDEX-SCAN (name = “Bart”) SCAN (Enroll) Student Index on(Student) Student(name) SCAN 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 11

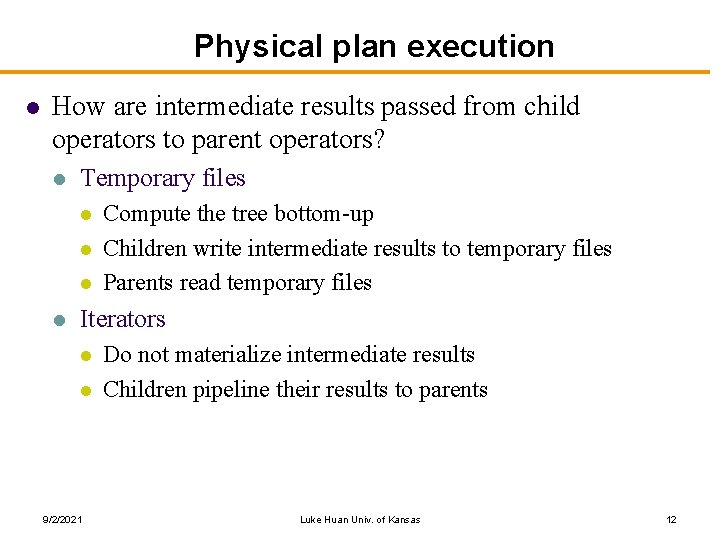

Physical plan execution l How are intermediate results passed from child operators to parent operators? l Temporary files l l Compute the tree bottom-up Children write intermediate results to temporary files Parents read temporary files Iterators l l 9/2/2021 Do not materialize intermediate results Children pipeline their results to parents Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 12

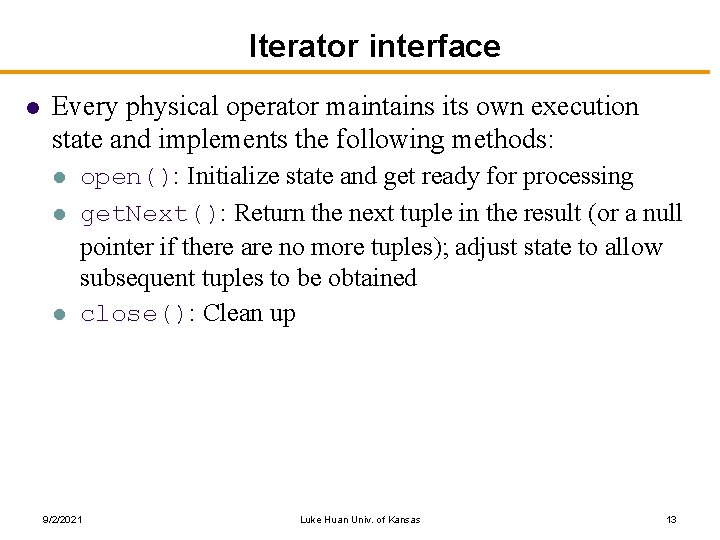

Iterator interface l Every physical operator maintains its own execution state and implements the following methods: l l l open(): Initialize state and get ready for processing get. Next(): Return the next tuple in the result (or a null pointer if there are no more tuples); adjust state to allow subsequent tuples to be obtained close(): Clean up 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 13

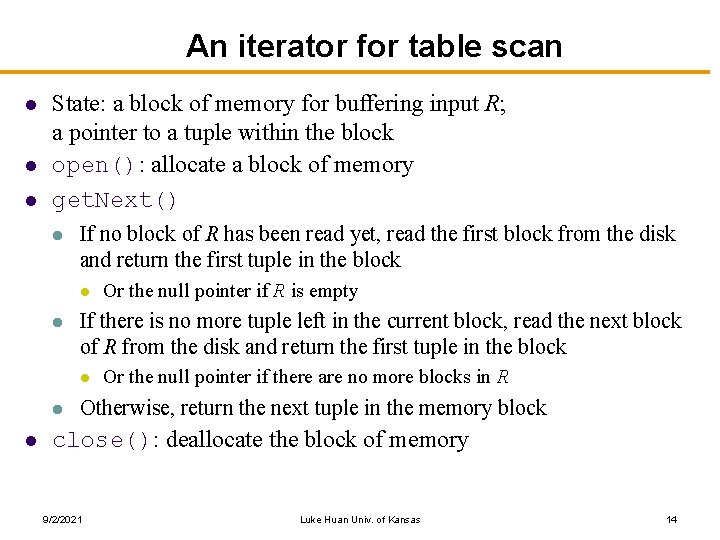

An iterator for table scan l l l State: a block of memory for buffering input R; a pointer to a tuple within the block open(): allocate a block of memory get. Next() l If no block of R has been read yet, read the first block from the disk and return the first tuple in the block l l If there is no more tuple left in the current block, read the next block of R from the disk and return the first tuple in the block l l l Or the null pointer if R is empty Or the null pointer if there are no more blocks in R Otherwise, return the next tuple in the memory block close(): deallocate the block of memory 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 14

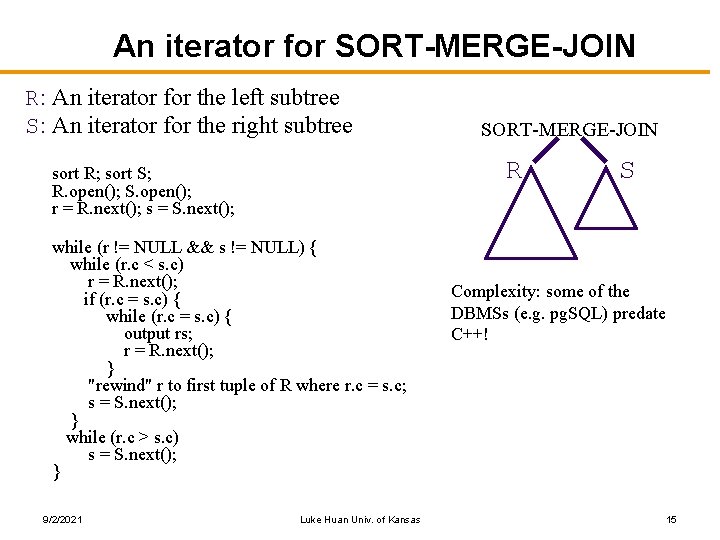

An iterator for SORT-MERGE-JOIN R: An iterator for the left subtree S: An iterator for the right subtree R sort R; sort S; R. open(); S. open(); r = R. next(); s = S. next(); while (r != NULL && s != NULL) { while (r. c < s. c) r = R. next(); if (r. c = s. c) { while (r. c = s. c) { output rs; r = R. next(); } "rewind" r to first tuple of R where r. c = s. c; s = S. next(); } while (r. c > s. c) s = S. next(); } 9/2/2021 SORT-MERGE-JOIN Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas S Complexity: some of the DBMSs (e. g. pg. SQL) predate C++! 15

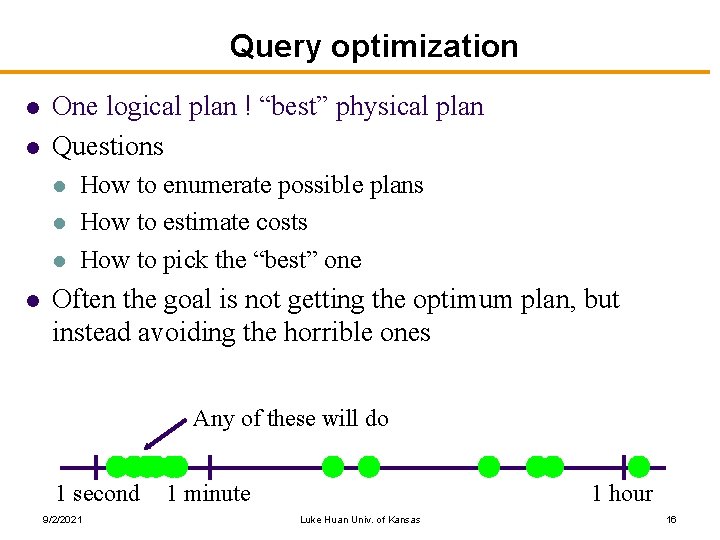

Query optimization l l One logical plan ! “best” physical plan Questions l l How to enumerate possible plans How to estimate costs How to pick the “best” one Often the goal is not getting the optimum plan, but instead avoiding the horrible ones Any of these will do 1 second 9/2/2021 1 minute 1 hour Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 16

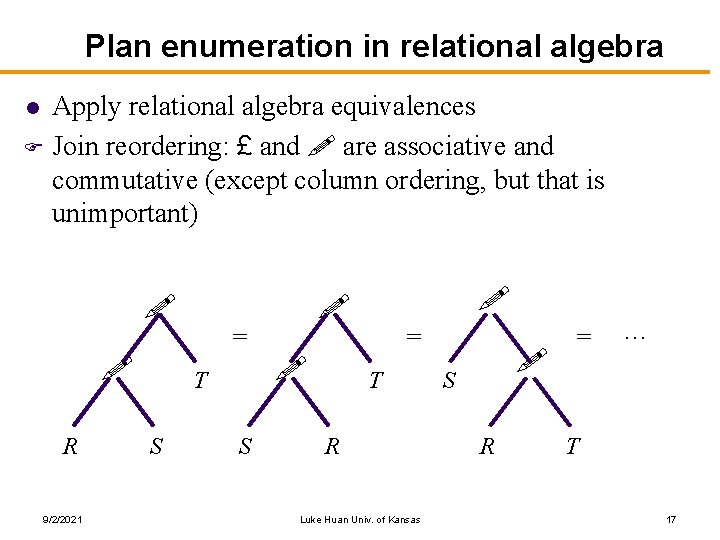

Plan enumeration in relational algebra Apply relational algebra equivalences F Join reordering: £ and ! are associative and commutative (except column ordering, but that is unimportant) l ! ! ! = ! R 9/2/2021 ! T S = S T R Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas ! S R = … T 17

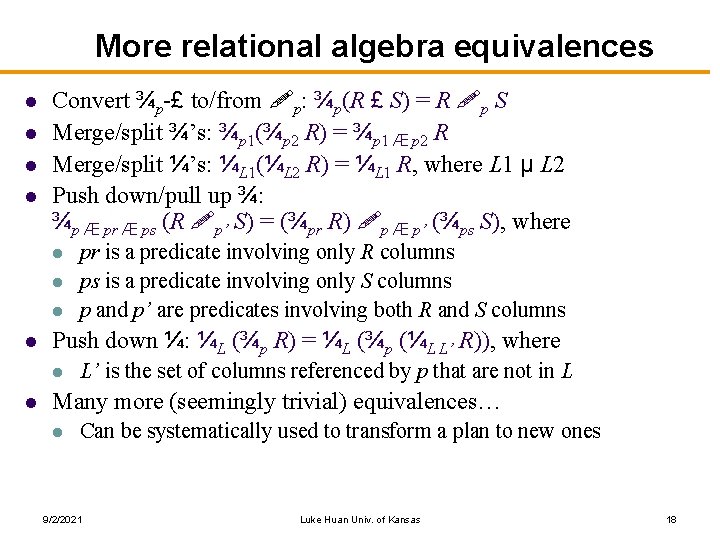

More relational algebra equivalences l l Convert ¾p-£ to/from !p: ¾p(R £ S) = R !p S Merge/split ¾’s: ¾p 1(¾p 2 R) = ¾p 1 Æ p 2 R Merge/split ¼’s: ¼L 1(¼L 2 R) = ¼L 1 R, where L 1 µ L 2 Push down/pull up ¾: ¾p Æ pr Æ ps (R !p’ S) = (¾pr R) !p Æ p’ (¾ps S), where l l Push down ¼: ¼L (¾p R) = ¼L (¾p (¼L L’ R)), where l l pr is a predicate involving only R columns ps is a predicate involving only S columns p and p’ are predicates involving both R and S columns L’ is the set of columns referenced by p that are not in L Many more (seemingly trivial) equivalences… l Can be systematically used to transform a plan to new ones 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 18

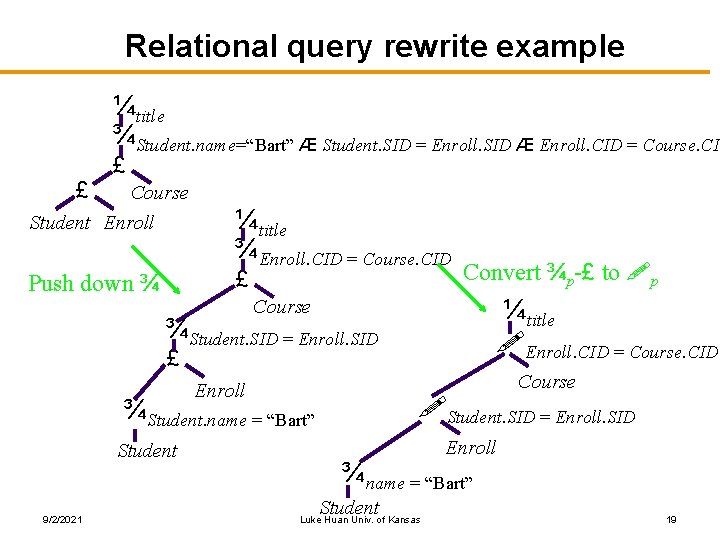

Relational query rewrite example ¼title ¾Student. name=“Bart” Æ Student. SID = Enroll. SID Æ Enroll. CID = Course. CID £ £ Course Student Enroll ¼title ¾Enroll. CID = Course. CID £ Push down ¾ Convert ¾p-£ to !p ¼title !Enroll. CID = Course. CID Course ¾Student. SID = Enroll. SID £ Course Enroll !Student. SID = Enroll. SID ¾Student. name = “Bart” Student 9/2/2021 Enroll ¾name = “Bart” Student Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 19

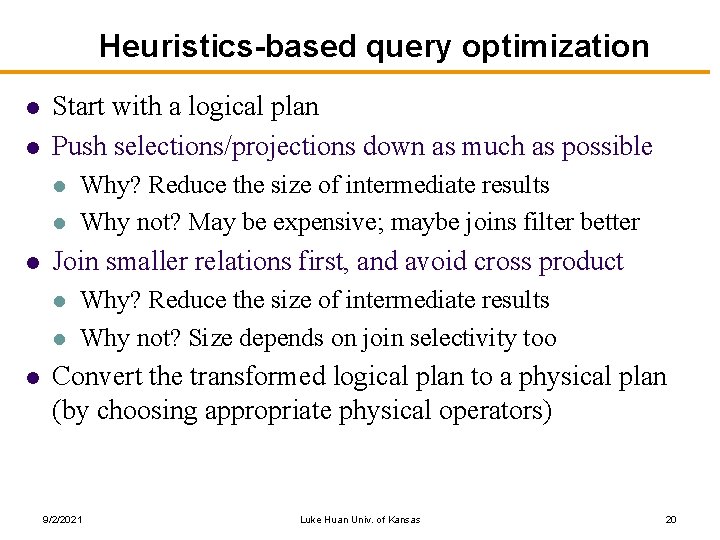

Heuristics-based query optimization l l Start with a logical plan Push selections/projections down as much as possible l l l Join smaller relations first, and avoid cross product l l l Why? Reduce the size of intermediate results Why not? May be expensive; maybe joins filter better Why? Reduce the size of intermediate results Why not? Size depends on join selectivity too Convert the transformed logical plan to a physical plan (by choosing appropriate physical operators) 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 20

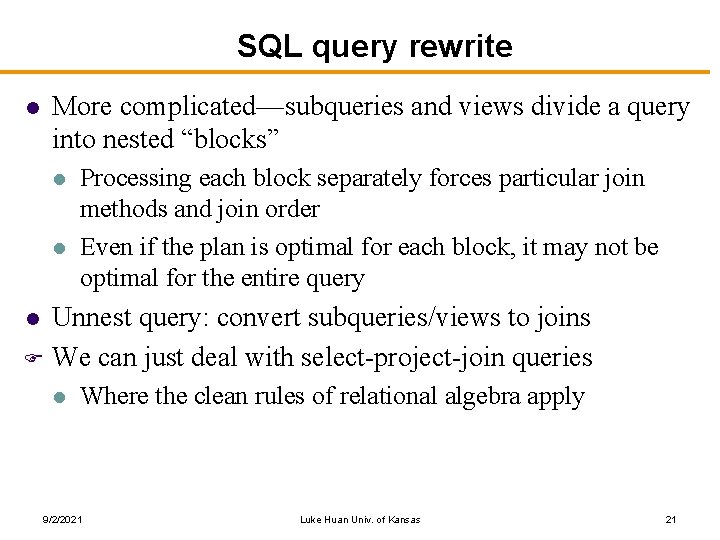

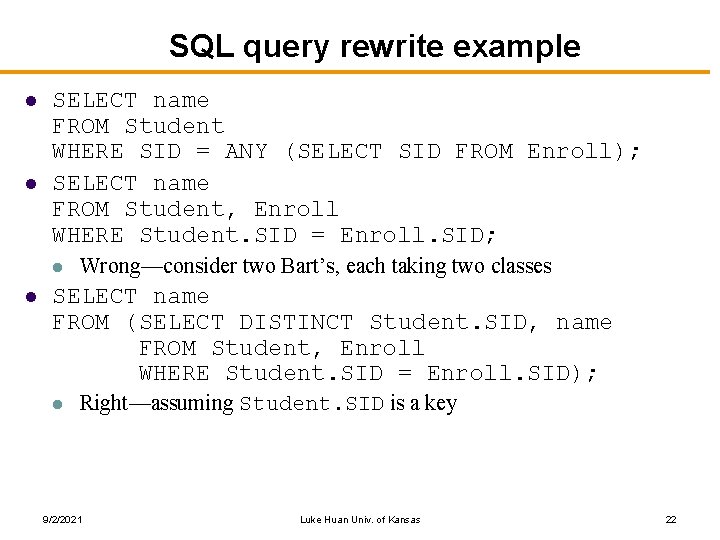

SQL query rewrite l More complicated—subqueries and views divide a query into nested “blocks” l l Processing each block separately forces particular join methods and join order Even if the plan is optimal for each block, it may not be optimal for the entire query Unnest query: convert subqueries/views to joins F We can just deal with select-project-join queries l l Where the clean rules of relational algebra apply 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 21

SQL query rewrite example l l SELECT name FROM Student WHERE SID = ANY (SELECT SID FROM Enroll); SELECT name FROM Student, Enroll WHERE Student. SID = Enroll. SID; l l Wrong—consider two Bart’s, each taking two classes SELECT name FROM (SELECT DISTINCT Student. SID, name FROM Student, Enroll WHERE Student. SID = Enroll. SID); l Right—assuming Student. SID is a key 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 22

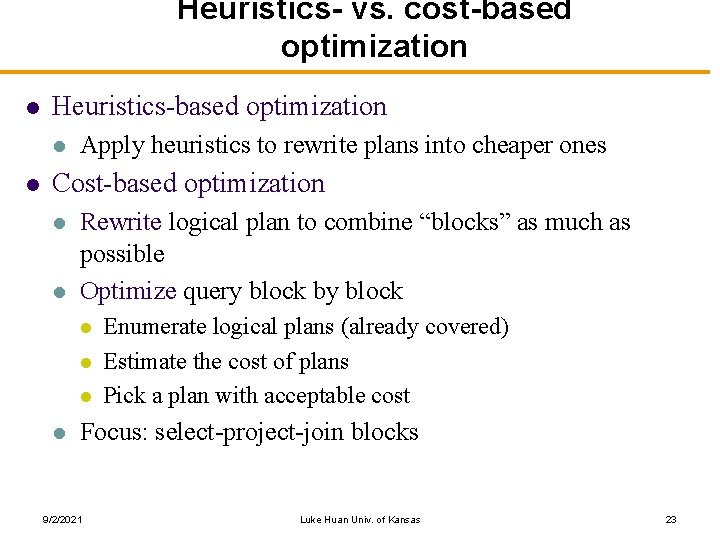

Heuristics- vs. cost-based optimization l Heuristics-based optimization l l Apply heuristics to rewrite plans into cheaper ones Cost-based optimization l l Rewrite logical plan to combine “blocks” as much as possible Optimize query block by block l l Enumerate logical plans (already covered) Estimate the cost of plans Pick a plan with acceptable cost Focus: select-project-join blocks 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 23

Recap of Query Processing in DBMS l l l Parser: SQL ! parse tree Rewriter: parse tree ! Logical plan Next: l Optimizer: logical plan ! Physcial plan 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 24

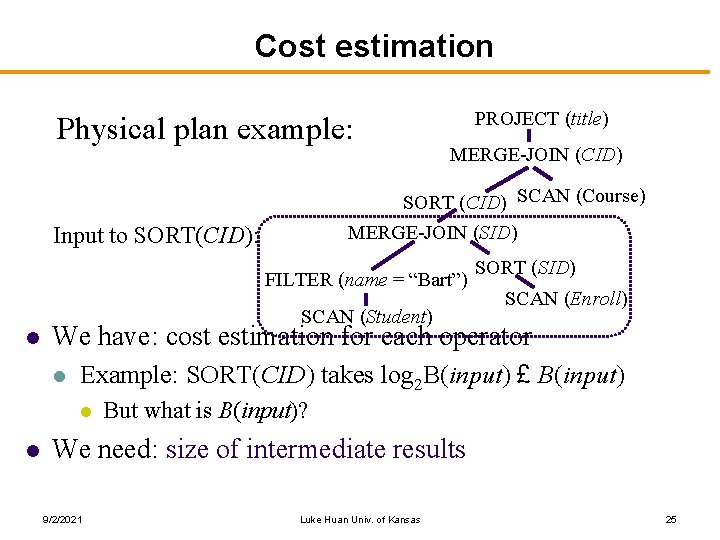

Cost estimation Physical plan example: PROJECT (title) MERGE-JOIN (CID) SORT (CID) SCAN (Course) MERGE-JOIN (SID) Input to SORT(CID): FILTER (name = “Bart”) l SCAN (Student) SCAN (Enroll) We have: cost estimation for each operator l Example: SORT(CID) takes log 2 B(input) £ B(input) l l SORT (SID) But what is B(input)? We need: size of intermediate results 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 25

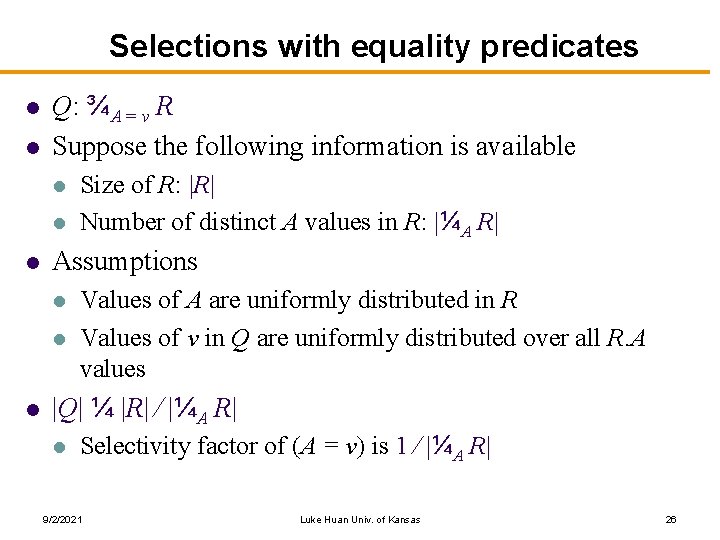

Selections with equality predicates l l Q: ¾A = v R Suppose the following information is available l l l Assumptions l l l Size of R: |R| Number of distinct A values in R: |¼A R| Values of A are uniformly distributed in R Values of v in Q are uniformly distributed over all R. A values |Q| ¼ |R| ⁄ |¼A R| l Selectivity factor of (A = v) is 1 ⁄ |¼A R| 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 26

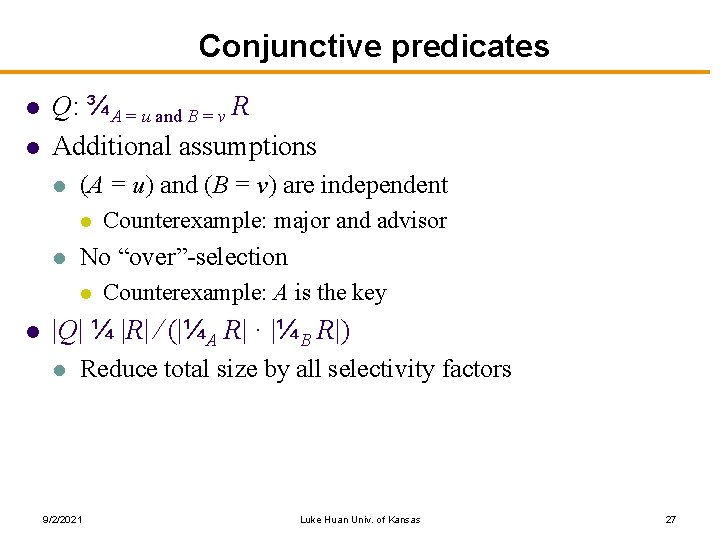

Conjunctive predicates l l Q: ¾A = u and B = v R Additional assumptions l (A = u) and (B = v) are independent l l No “over”-selection l l Counterexample: major and advisor Counterexample: A is the key |Q| ¼ |R| ⁄ (|¼A R| · |¼B R|) l Reduce total size by all selectivity factors 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 27

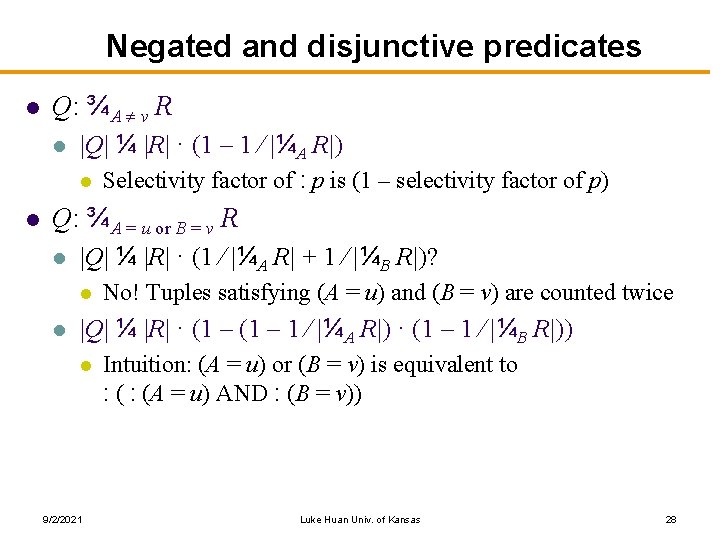

Negated and disjunctive predicates l Q: ¾A ¹ v R l |Q| ¼ |R| · (1 – 1 ⁄ |¼A R|) l l Selectivity factor of : p is (1 – selectivity factor of p) Q: ¾A = u or B = v R l |Q| ¼ |R| · (1 ⁄ |¼A R| + 1 ⁄ |¼B R|)? l l No! Tuples satisfying (A = u) and (B = v) are counted twice |Q| ¼ |R| · (1 – 1 ⁄ |¼A R|) · (1 – 1 ⁄ |¼B R|)) l 9/2/2021 Intuition: (A = u) or (B = v) is equivalent to : (A = u) AND : (B = v)) Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 28

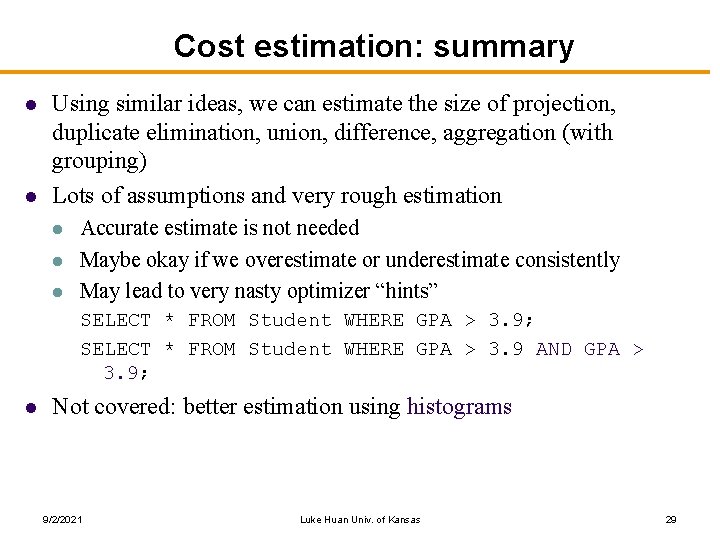

Cost estimation: summary l l Using similar ideas, we can estimate the size of projection, duplicate elimination, union, difference, aggregation (with grouping) Lots of assumptions and very rough estimation l l l Accurate estimate is not needed Maybe okay if we overestimate or underestimate consistently May lead to very nasty optimizer “hints” SELECT * FROM Student WHERE GPA > 3. 9; SELECT * FROM Student WHERE GPA > 3. 9 AND GPA > 3. 9; l Not covered: better estimation using histograms 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 29

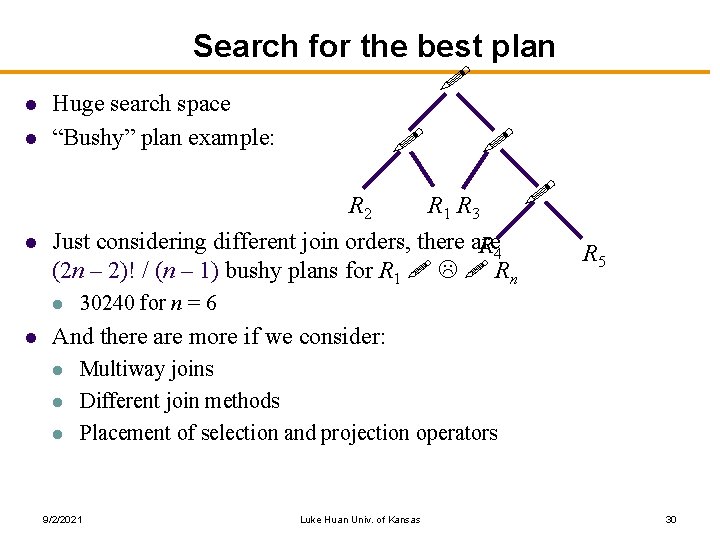

l l Search for the best plan ! Huge search space “Bushy” plan example: ! R 2 l R 1 R 3 Just considering different join orders, there are R 4 (2 n – 2)! / (n – 1) bushy plans for R 1 ! L ! Rn l l ! ! R 5 30240 for n = 6 And there are more if we consider: l l l Multiway joins Different join methods Placement of selection and projection operators 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 30

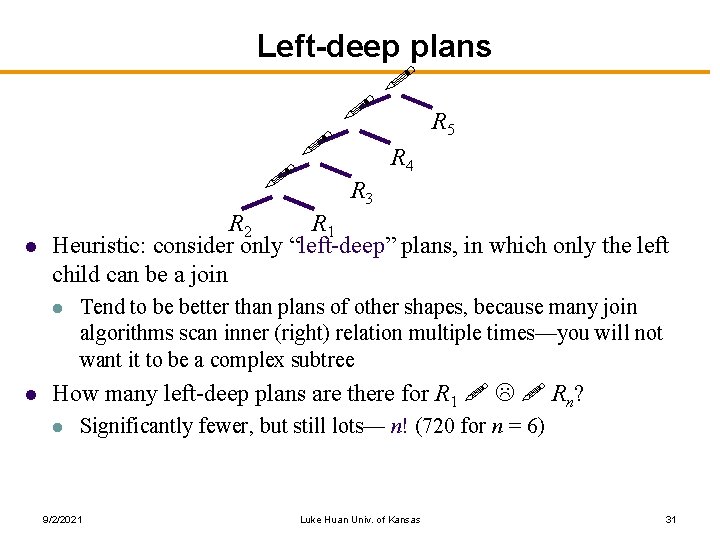

Left-deep plans ! ! R 5 ! R 4 ! R 3 l R 2 R 1 Heuristic: consider only “left-deep” plans, in which only the left child can be a join l l Tend to be better than plans of other shapes, because many join algorithms scan inner (right) relation multiple times—you will not want it to be a complex subtree How many left-deep plans are there for R 1 ! L ! Rn? l Significantly fewer, but still lots— n! (720 for n = 6) 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 31

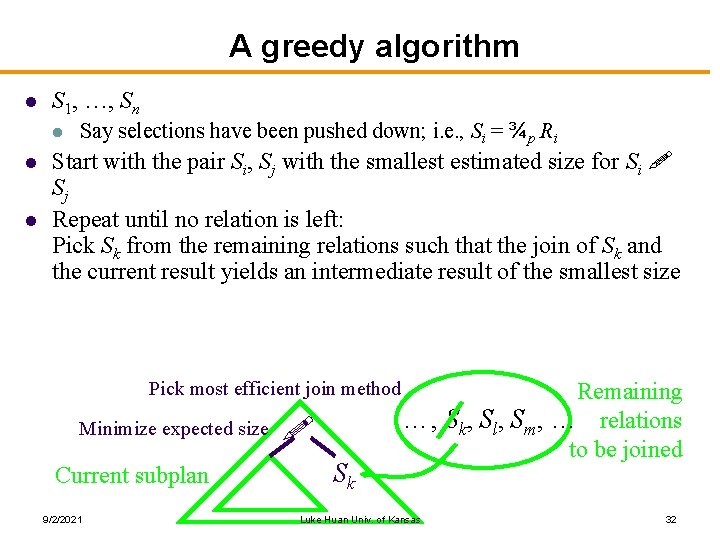

A greedy algorithm l S 1, …, Sn l l l Say selections have been pushed down; i. e. , Si = ¾p Ri Start with the pair Si, Sj with the smallest estimated size for Si ! Sj Repeat until no relation is left: Pick Sk from the remaining relations such that the join of Sk and the current result yields an intermediate result of the smallest size Pick most efficient join method Minimize expected size Current subplan 9/2/2021 ! Sk Remaining …, Sk, Sl, Sm, … relations to be joined Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 32

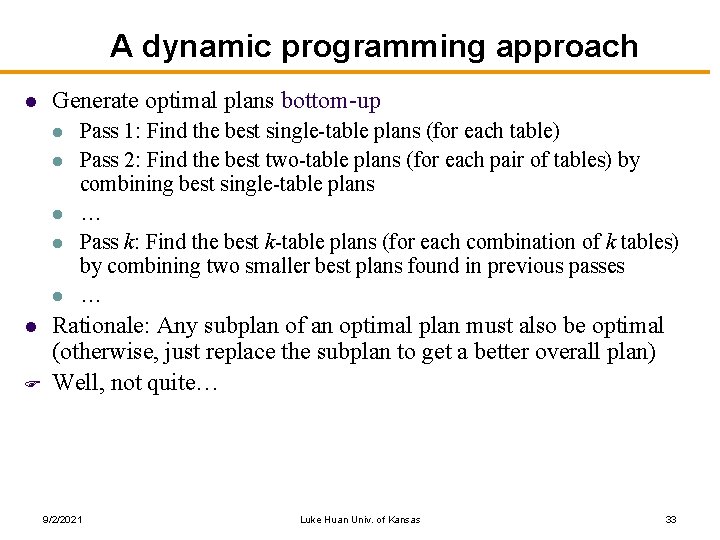

A dynamic programming approach l Generate optimal plans bottom-up l l l F Pass 1: Find the best single-table plans (for each table) Pass 2: Find the best two-table plans (for each pair of tables) by combining best single-table plans … Pass k: Find the best k-table plans (for each combination of k tables) by combining two smaller best plans found in previous passes … Rationale: Any subplan of an optimal plan must also be optimal (otherwise, just replace the subplan to get a better overall plan) Well, not quite… 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 33

The need for “interesting order” l l l Example: R(A, B) ! S(A, C) ! T(A, D) Best plan for R ! S: hash join (beats sort-merge join) Best overall plan: sort-merge join R and S, and then sort-merge join with T l l Subplan of the optimal plan is not optimal! Why? l l The result of the sort-merge join of R and S is sorted on A This is an interesting order that can be exploited by later processing (e. g. , join, duplicate elimination, GROUP BY, ORDER BY, etc. )! 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 34

Summary l l Relational algebra equivalence SQL rewrite tricks Heuristics-based optimization Cost-based optimization l l l Need statistics to estimate sizes of intermediate results Greedy approach Dynamic programming approach 9/2/2021 Luke Huan Univ. of Kansas 35

- Slides: 35