Early Modern 1500 1750 AD Christianity still strong

- Slides: 4

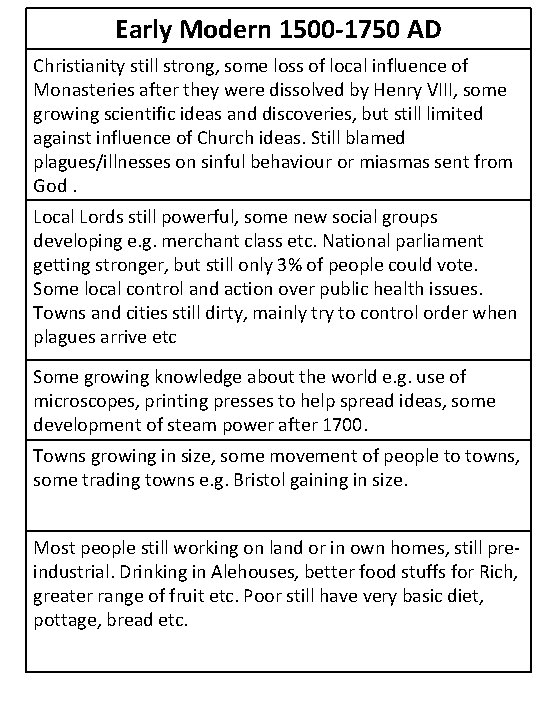

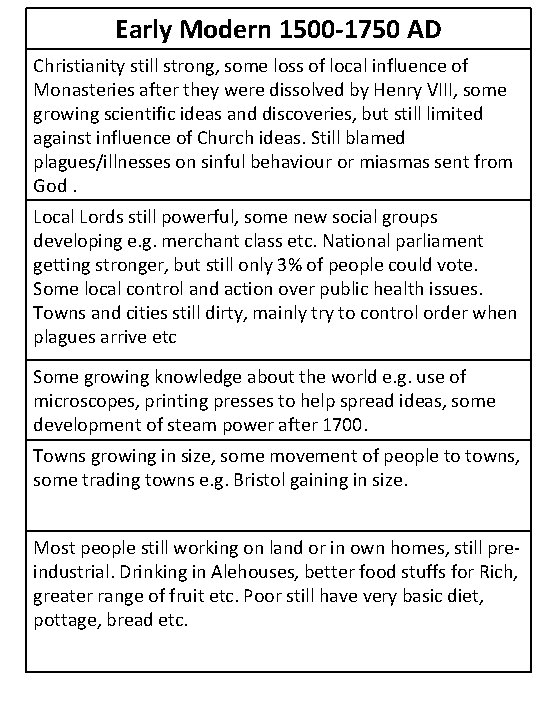

Early Modern 1500 -1750 AD Christianity still strong, some loss of local influence of Monasteries after they were dissolved by Henry VIII, some growing scientific ideas and discoveries, but still limited against influence of Church ideas. Still blamed plagues/illnesses on sinful behaviour or miasmas sent from God. Local Lords still powerful, some new social groups developing e. g. merchant class etc. National parliament getting stronger, but still only 3% of people could vote. Some local control and action over public health issues. Towns and cities still dirty, mainly try to control order when plagues arrive etc Some growing knowledge about the world e. g. use of microscopes, printing presses to help spread ideas, some development of steam power after 1700. Towns growing in size, some movement of people to towns, some trading towns e. g. Bristol gaining in size. Most people still working on land or in own homes, still preindustrial. Drinking in Alehouses, better food stuffs for Rich, greater range of fruit etc. Poor still have very basic diet, pottage, bread etc.

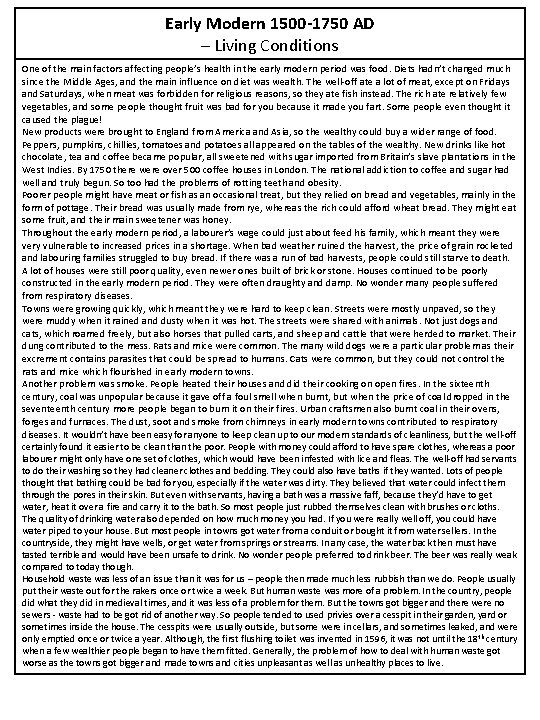

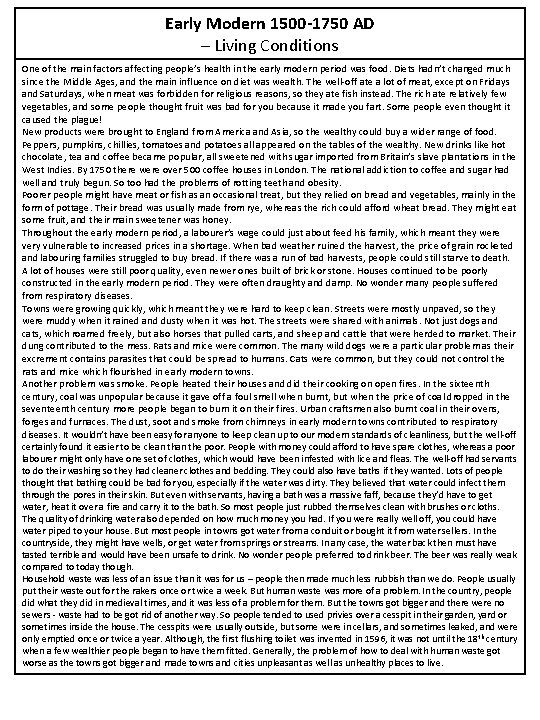

Early Modern 1500 -1750 AD – Living Conditions One of the main factors affecting people’s health in the early modern period was food. Diets hadn’t changed much since the Middle Ages, and the main influence on diet was wealth. The well-off ate a lot of meat, except on Fridays and Saturdays, when meat was forbidden for religious reasons, so they ate fish instead. The rich ate relatively few vegetables, and some people thought fruit was bad for you because it made you fart. Some people even thought it caused the plague! New products were brought to England from America and Asia, so the wealthy could buy a wider range of food. Peppers, pumpkins, chillies, tomatoes and potatoes all appeared on the tables of the wealthy. New drinks like hot chocolate, tea and coffee became popular, all sweetened with sugar imported from Britain’s slave plantations in the West Indies. By 1750 there were over 500 coffee houses in London. The national addiction to coffee and sugar had well and truly begun. So too had the problems of rotting teeth and obesity. Poorer people might have meat or fish as an occasional treat, but they relied on bread and vegetables, mainly in the form of pottage. Their bread was usually made from rye, whereas the rich could afford wheat bread. They might eat some fruit, and their main sweetener was honey. Throughout the early modern period, a labourer’s wage could just about feed his family, which meant they were very vulnerable to increased prices in a shortage. When bad weather ruined the harvest, the price of grain rocketed and labouring families struggled to buy bread. If there was a run of bad harvests, people could still starve to death. A lot of houses were still poor quality, even newer ones built of brick or stone. Houses continued to be poorly constructed in the early modern period. They were often draughty and damp. No wonder many people suffered from respiratory diseases. Towns were growing quickly, which meant they were hard to keep clean. Streets were mostly unpaved, so they were muddy when it rained and dusty when it was hot. The streets were shared with animals. Not just dogs and cats, which roamed freely, but also horses that pulled carts, and sheep and cattle that were herded to market. Their dung contributed to the mess. Rats and mice were common. The many wild dogs were a particular problem as their excrement contains parasites that could be spread to humans. Cats were common, but they could not control the rats and mice which flourished in early modern towns. Another problem was smoke. People heated their houses and did their cooking on open fires. In the sixteenth century, coal was unpopular because it gave off a foul smell when burnt, but when the price of coal dropped in the seventeenth century more people began to burn it on their fires. Urban craftsmen also burnt coal in their ovens, forges and furnaces. The dust, soot and smoke from chimneys in early modern towns contributed to respiratory diseases. It wouldn’t have been easy for anyone to keep clean up to our modern standards of cleanliness, but the well-off certainly found it easier to be clean the poor. People with money could afford to have spare clothes, whereas a poor labourer might only have one set of clothes, which would have been infested with lice and fleas. The well-off had servants to do their washing so they had cleaner clothes and bedding. They could also have baths if they wanted. Lots of people thought that bathing could be bad for you, especially if the water was dirty. They believed that water could infect them through the pores in their skin. But even with servants, having a bath was a massive faff, because they’d have to get water, heat it over a fire and carry it to the bath. So most people just rubbed themselves clean with brushes or cloths. The quality of drinking water also depended on how much money you had. If you were really well off, you could have water piped to your house. But most people in towns got water from a conduit or bought it from water sellers. In the countryside, they might have wells, or get water from springs or streams. In any case, the water back then must have tasted terrible and would have been unsafe to drink. No wonder people preferred to drink beer. The beer was really weak compared to today though. Household waste was less of an issue than it was for us – people then made much less rubbish than we do. People usually put their waste out for the rakers once or twice a week. But human waste was more of a problem. In the country, people did what they did in medieval times, and it was less of a problem for them. But the towns got bigger and there were no sewers - waste had to be got rid of another way. So people tended to used privies over a cesspit in their garden, yard or sometimes inside the house. The cesspits were usually outside, but some were in cellars, and sometimes leaked, and were only emptied once or twice a year. Although, the first flushing toilet was invented in 1596, it was not until the 18 th century when a few wealthier people began to have them fitted. Generally, the problem of how to deal with human waste got worse as the towns got bigger and made towns and cities unpleasant as well as unhealthy places to live.

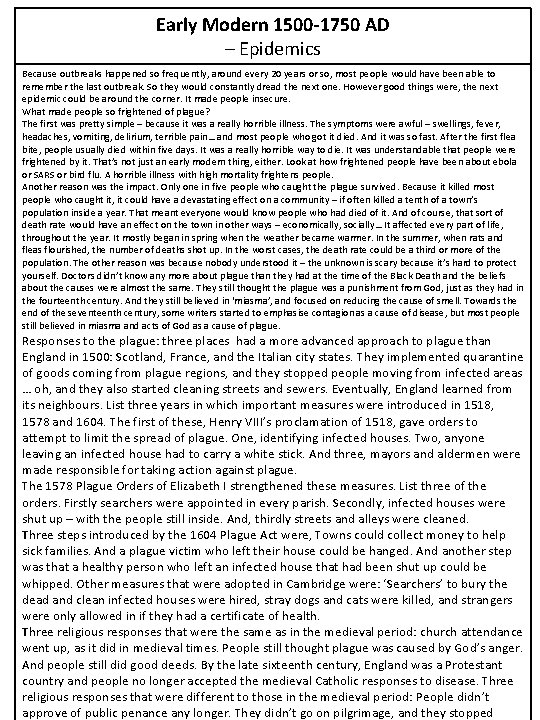

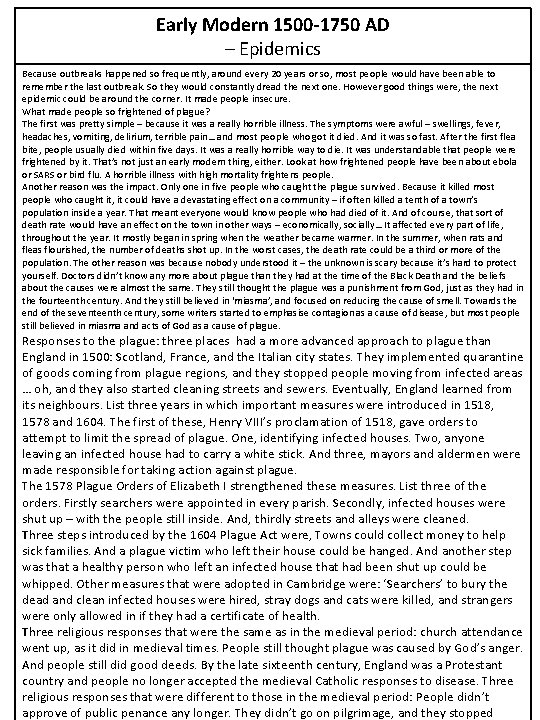

Early Modern 1500 -1750 AD – Epidemics Because outbreaks happened so frequently, around every 20 years or so, most people would have been able to remember the last outbreak. So they would constantly dread the next one. However good things were, the next epidemic could be around the corner. It made people insecure. What made people so frightened of plague? The first was pretty simple – because it was a really horrible illness. The symptoms were awful – swellings, fever, headaches, vomiting, delirium, terrible pain… and most people who got it died. And it was so fast. After the first flea bite, people usually died within five days. It was a really horrible way to die. It was understandable that people were frightened by it. That’s not just an early modern thing, either. Look at how frightened people have been about ebola or SARS or bird flu. A horrible illness with high mortality frightens people. Another reason was the impact. Only one in five people who caught the plague survived. Because it killed most people who caught it, it could have a devastating effect on a community – if often killed a tenth of a town’s population inside a year. That meant everyone would know people who had died of it. And of course, that sort of death rate would have an effect on the town in other ways – economically, socially… It affected every part of life, throughout the year. It mostly began in spring when the weather became warmer. In the summer, when rats and fleas flourished, the number of deaths shot up. In the worst cases, the death rate could be a third or more of the population. The other reason was because nobody understood it – the unknown is scary because it’s hard to protect yourself. Doctors didn’t know any more about plague than they had at the time of the Black Death and the beliefs about the causes were almost the same. They still thought the plague was a punishment from God, just as they had in the fourteenth century. And they still believed in ‘miasma’, and focused on reducing the cause of smell. Towards the end of the seventeenth century, some writers started to emphasise contagion as a cause of disease, but most people still believed in miasma and acts of God as a cause of plague. Responses to the plague: three places had a more advanced approach to plague than England in 1500: Scotland, France, and the Italian city states. They implemented quarantine of goods coming from plague regions, and they stopped people moving from infected areas … oh, and they also started cleaning streets and sewers. Eventually, England learned from its neighbours. List three years in which important measures were introduced in 1518, 1578 and 1604. The first of these, Henry VIII’s proclamation of 1518, gave orders to attempt to limit the spread of plague. One, identifying infected houses. Two, anyone leaving an infected house had to carry a white stick. And three, mayors and aldermen were made responsible for taking action against plague. The 1578 Plague Orders of Elizabeth I strengthened these measures. List three of the orders. Firstly searchers were appointed in every parish. Secondly, infected houses were shut up – with the people still inside. And, thirdly streets and alleys were cleaned. Three steps introduced by the 1604 Plague Act were, Towns could collect money to help sick families. And a plague victim who left their house could be hanged. And another step was that a healthy person who left an infected house that had been shut up could be whipped. Other measures that were adopted in Cambridge were: ‘Searchers’ to bury the dead and clean infected houses were hired, stray dogs and cats were killed, and strangers were only allowed in if they had a certificate of health. Three religious responses that were the same as in the medieval period: church attendance went up, as it did in medieval times. People still thought plague was caused by God’s anger. And people still did good deeds. By the late sixteenth century, England was a Protestant country and people no longer accepted the medieval Catholic responses to disease. Three religious responses that were different to those in the medieval period: People didn’t approve of public penance any longer. They didn’t go on pilgrimage, and they stopped

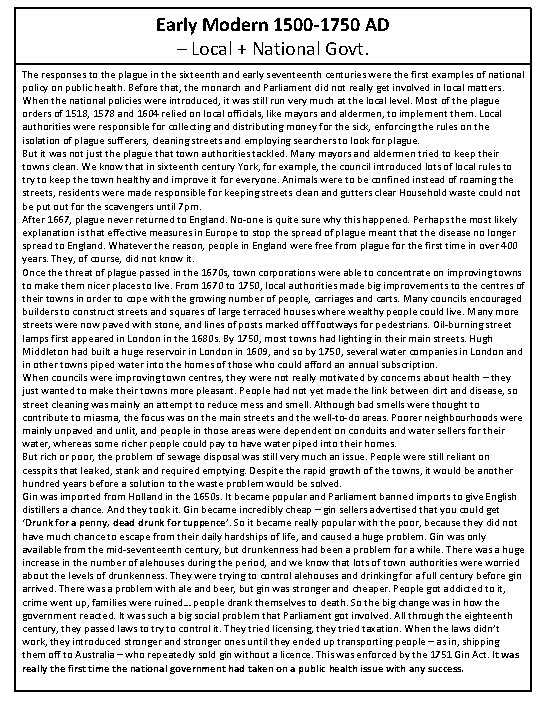

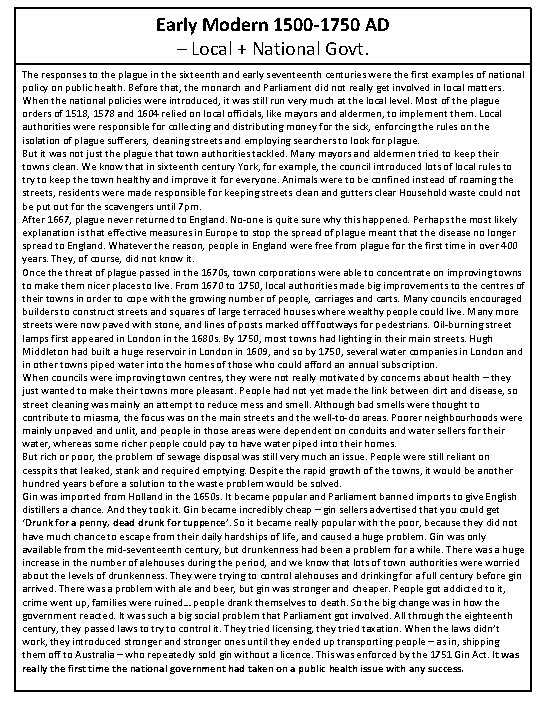

Early Modern 1500 -1750 AD – Local + National Govt. The responses to the plague in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries were the first examples of national policy on public health. Before that, the monarch and Parliament did not really get involved in local matters. When the national policies were introduced, it was still run very much at the local level. Most of the plague orders of 1518, 1578 and 1604 relied on local officials, like mayors and aldermen, to implement them. Local authorities were responsible for collecting and distributing money for the sick, enforcing the rules on the isolation of plague sufferers, cleaning streets and employing searchers to look for plague. But it was not just the plague that town authorities tackled. Many mayors and aldermen tried to keep their towns clean. We know that in sixteenth century York, for example, the council introduced lots of local rules to try to keep the town healthy and improve it for everyone. Animals were to be confined instead of roaming the streets, residents were made responsible for keeping streets clean and gutters clear Household waste could not be put out for the scavengers until 7 pm. After 1667, plague never returned to England. No-one is quite sure why this happened. Perhaps the most likely explanation is that effective measures in Europe to stop the spread of plague meant that the disease no longer spread to England. Whatever the reason, people in England were free from plague for the first time in over 400 years. They, of course, did not know it. Once threat of plague passed in the 1670 s, town corporations were able to concentrate on improving towns to make them nicer places to live. From 1670 to 1750, local authorities made big improvements to the centres of their towns in order to cope with the growing number of people, carriages and carts. Many councils encouraged builders to construct streets and squares of large terraced houses where wealthy people could live. Many more streets were now paved with stone, and lines of posts marked off footways for pedestrians. Oil-burning street lamps first appeared in London in the 1680 s. By 1750, most towns had lighting in their main streets. Hugh Middleton had built a huge reservoir in London in 1609, and so by 1750, several water companies in London and in other towns piped water into the homes of those who could afford an annual subscription. When councils were improving town centres, they were not really motivated by concerns about health – they just wanted to make their towns more pleasant. People had not yet made the link between dirt and disease, so street cleaning was mainly an attempt to reduce mess and smell. Although bad smells were thought to contribute to miasma, the focus was on the main streets and the well-to-do areas. Poorer neighbourhoods were mainly unpaved and unlit, and people in those areas were dependent on conduits and water sellers for their water, whereas some richer people could pay to have water piped into their homes. But rich or poor, the problem of sewage disposal was still very much an issue. People were still reliant on cesspits that leaked, stank and required emptying. Despite the rapid growth of the towns, it would be another hundred years before a solution to the waste problem would be solved. Gin was imported from Holland in the 1650 s. It became popular and Parliament banned imports to give English distillers a chance. And they took it. Gin became incredibly cheap – gin sellers advertised that you could get ‘Drunk for a penny, dead drunk for tuppence’. So it became really popular with the poor, because they did not have much chance to escape from their daily hardships of life, and caused a huge problem. Gin was only available from the mid-seventeenth century, but drunkenness had been a problem for a while. There was a huge increase in the number of alehouses during the period, and we know that lots of town authorities were worried about the levels of drunkenness. They were trying to control alehouses and drinking for a full century before gin arrived. There was a problem with ale and beer, but gin was stronger and cheaper. People got addicted to it, crime went up, families were ruined… people drank themselves to death. So the big change was in how the government reacted. It was such a big social problem that Parliament got involved. All through the eighteenth century, they passed laws to try to control it. They tried licensing, they tried taxation. When the laws didn’t work, they introduced stronger and stronger ones until they ended up transporting people – as in, shipping them off to Australia – who repeatedly sold gin without a licence. This was enforced by the 1751 Gin Act. It was really the first time the national government had taken on a public health issue with any success.