Dynamic Routing Distance Vector and Link State RIP

- Slides: 42

Dynamic Routing Distance Vector and Link State RIP OSPF

Internet Routing • IP implements datagram forwarding • Both hosts and routers • Have an IP module • Forward datagrams • IP forwarding is table-driven • Table known as routing table

Routing Tables • Static routing • Fixes routes at boot time • Requires human intervention • Useful only for simplest cases • Dynamic routing • Table initialized at boot time • Routers communicate to learn new information and update their routing tables continuously: • Protocols used for information exchange to propagate route data • Data inserted/updated by protocols

Autonomous Systems • An autonomous system (AS) is a region of the Internet that is administered by a single entity and that has a unified routing policy • Each autonomous system is assigned an Autonomous System Number (ASN). Each ASN is either 16 bits or 32 bits • ASN assigned by Regional Internet Registries • Some are reserved for private use and never appear on the Internet • Example ASNs • U of T’s campus network (AS 239) • Sprint (AS 1239, AS 1240, AS 6211, …) 4

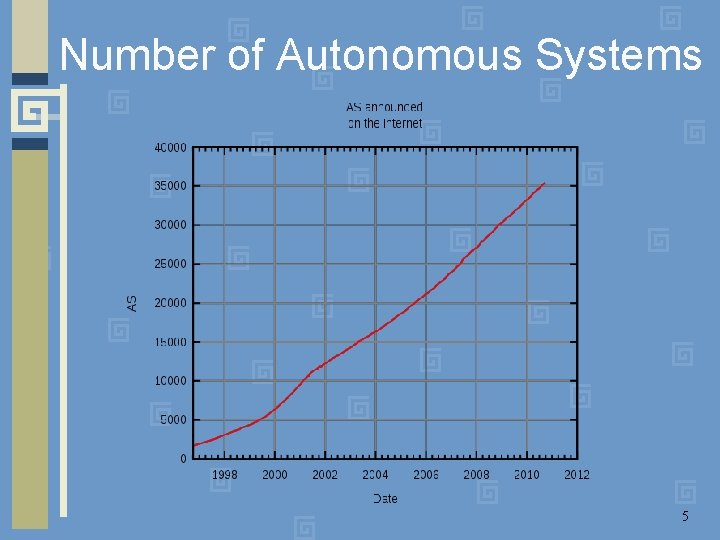

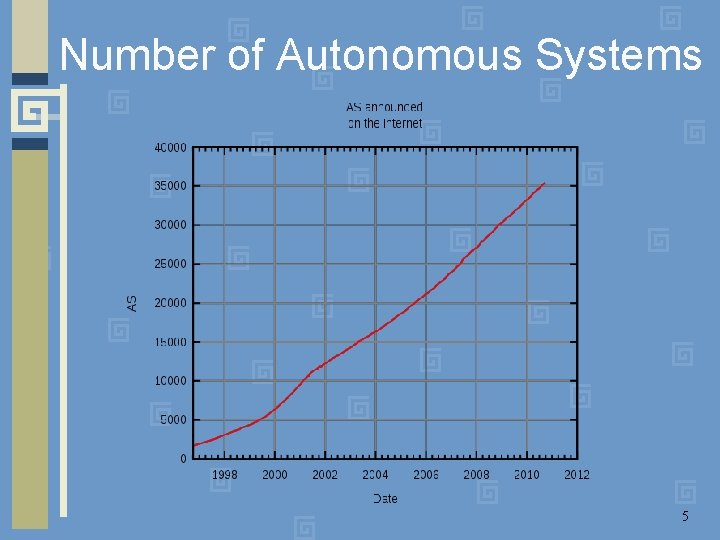

Number of Autonomous Systems 5

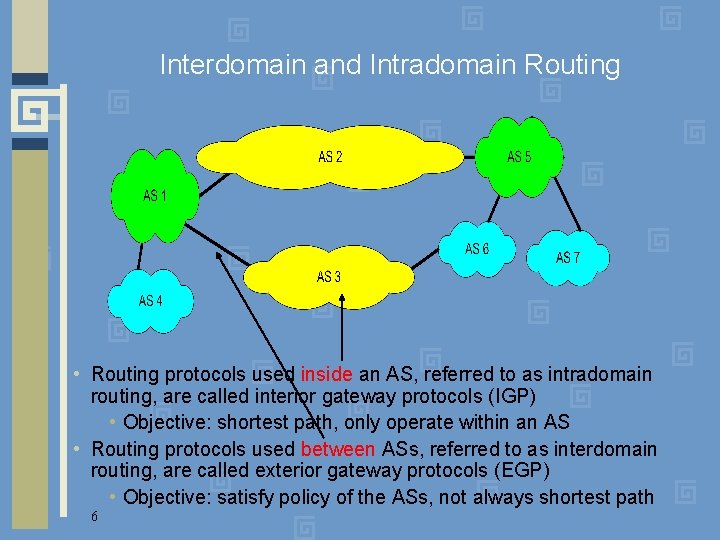

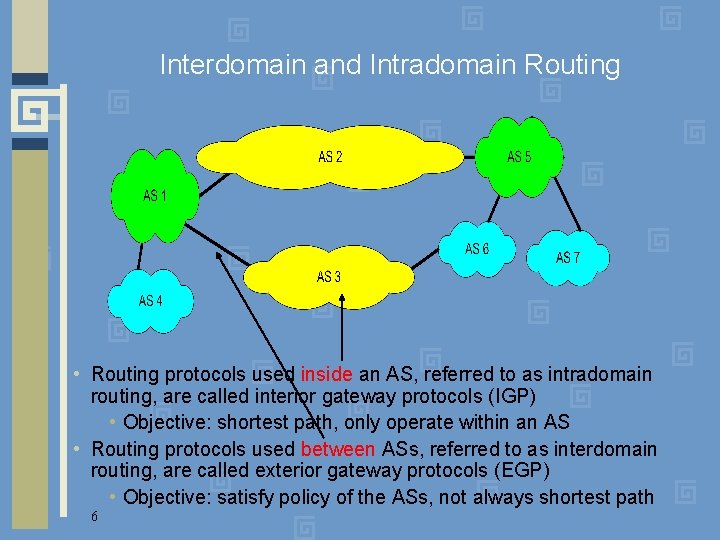

Interdomain and Intradomain Routing • Routing protocols used inside an AS, referred to as intradomain routing, are called interior gateway protocols (IGP) • Objective: shortest path, only operate within an AS • Routing protocols used between ASs, referred to as interdomain routing, are called exterior gateway protocols (EGP) • Objective: satisfy policy of the ASs, not always shortest path 6

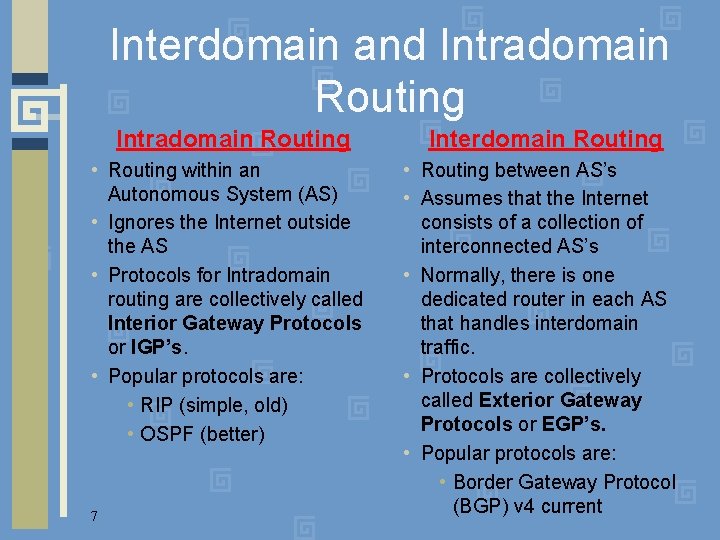

Interdomain and Intradomain Routing Interdomain Routing • Routing within an Autonomous System (AS) • Ignores the Internet outside the AS • Protocols for Intradomain routing are collectively called Interior Gateway Protocols or IGP’s. • Popular protocols are: • RIP (simple, old) • OSPF (better) • Routing between AS’s • Assumes that the Internet consists of a collection of interconnected AS’s • Normally, there is one dedicated router in each AS that handles interdomain traffic. • Protocols are collectively called Exterior Gateway Protocols or EGP’s. • Popular protocols are: • Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) v 4 current 7

EGP and IGP 1 • Interior Gateway Protocol (IGP) • Routing is done based on metrics • Routing domain is one AS • Exterior Gateway Protocol (EGP) 8 • Routing is done based on policies • Routing domain is the entire Internet

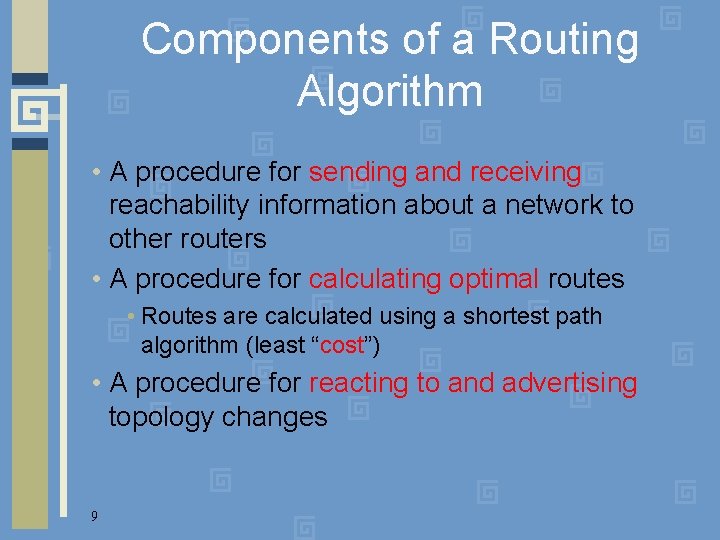

Components of a Routing Algorithm • A procedure for sending and receiving reachability information about a network to other routers • A procedure for calculating optimal routes • Routes are calculated using a shortest path algorithm (least “cost”) • A procedure for reacting to and advertising topology changes 9

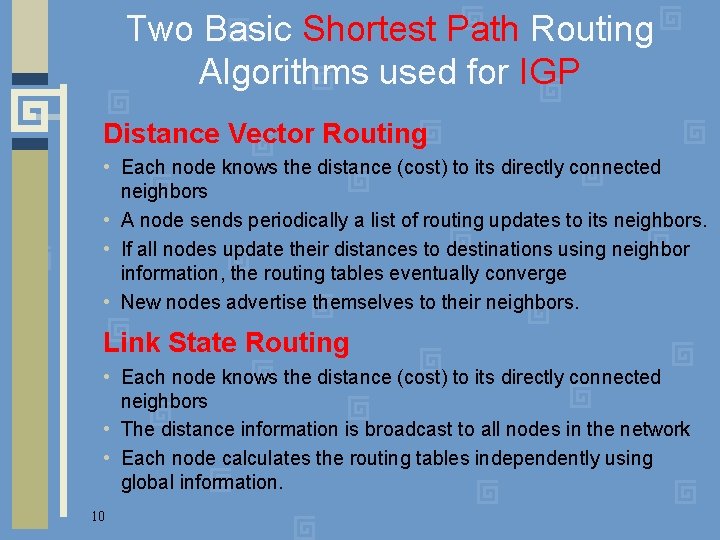

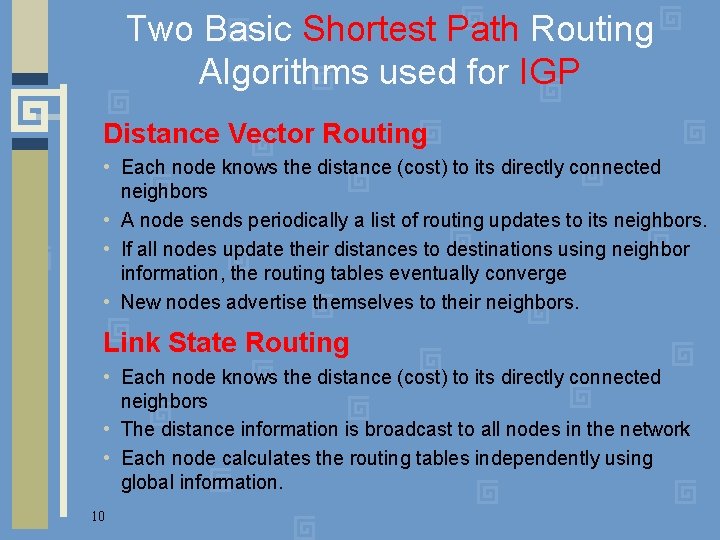

Two Basic Shortest Path Routing Algorithms used for IGP Distance Vector Routing • Each node knows the distance (cost) to its directly connected neighbors • A node sends periodically a list of routing updates to its neighbors. • If all nodes update their distances to destinations using neighbor information, the routing tables eventually converge • New nodes advertise themselves to their neighbors. Link State Routing • Each node knows the distance (cost) to its directly connected neighbors • The distance information is broadcast to all nodes in the network • Each node calculates the routing tables independently using global information. 10

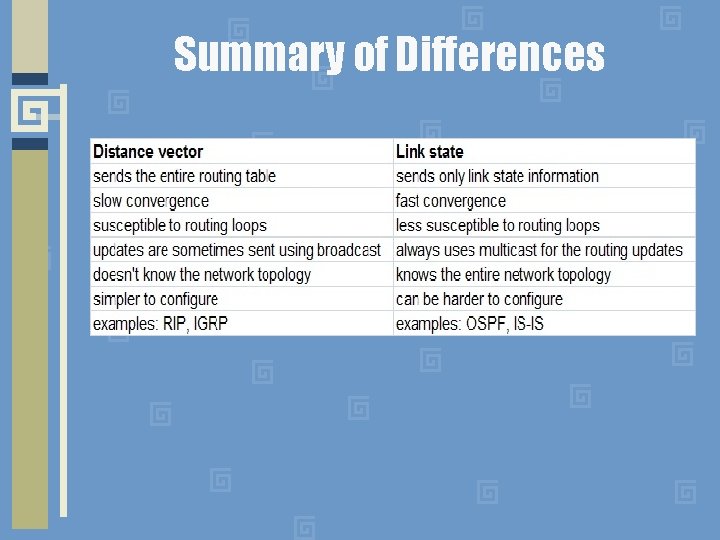

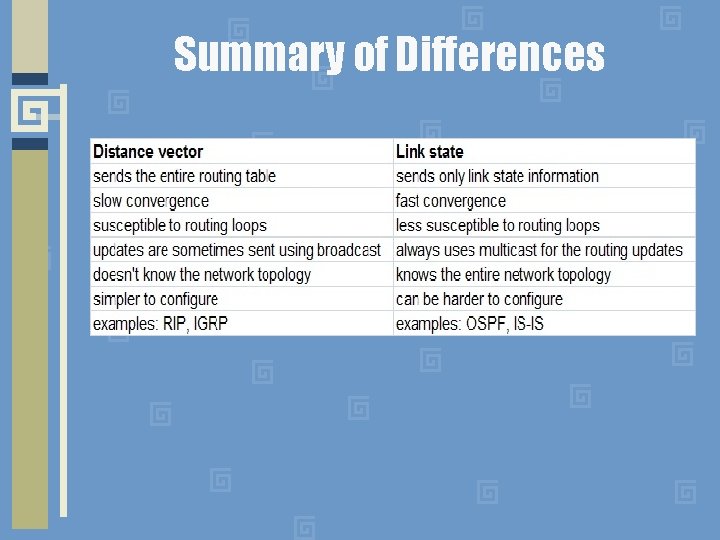

Summary of Differences

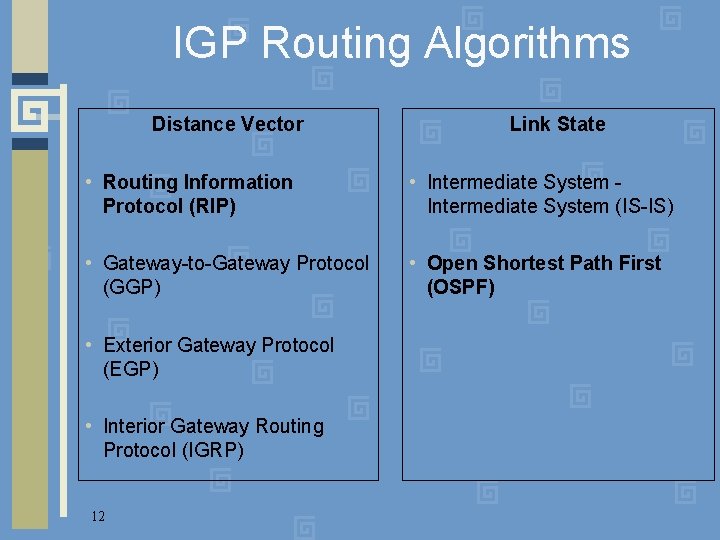

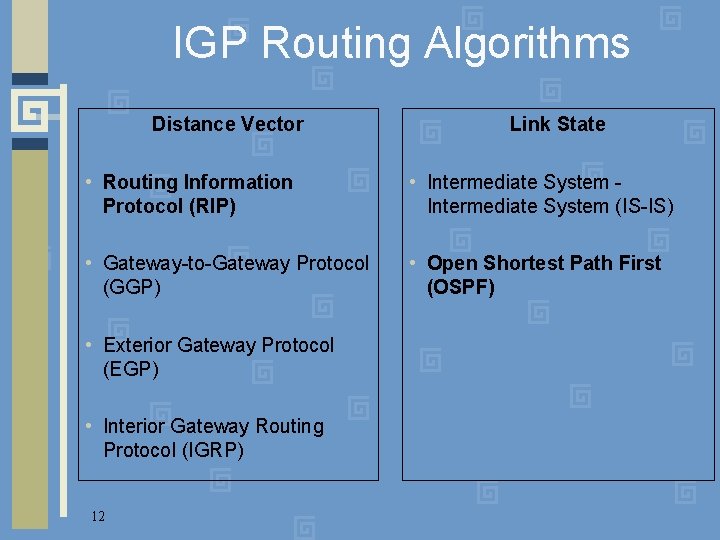

IGP Routing Algorithms Distance Vector Link State • Routing Information Protocol (RIP) • Intermediate System - Intermediate System (IS-IS) • Gateway-to-Gateway Protocol (GGP) • Open Shortest Path First (OSPF) • Exterior Gateway Protocol (EGP) • Interior Gateway Routing Protocol (IGRP) 12

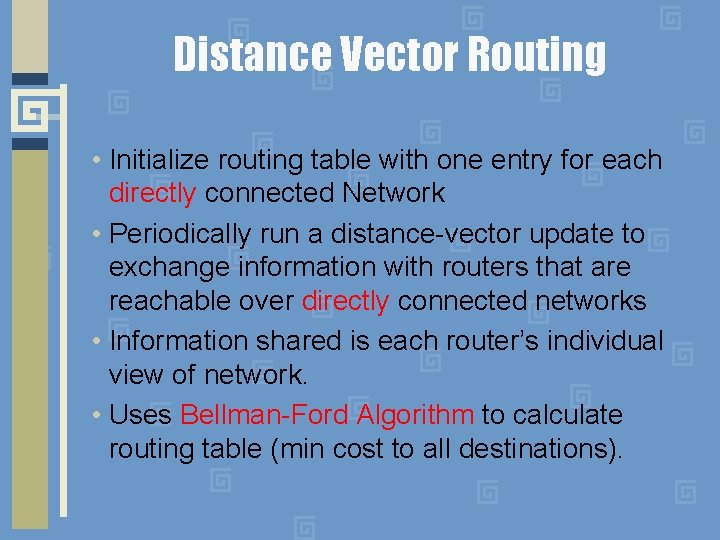

Distance Vector Routing • Initialize routing table with one entry for each directly connected Network • Periodically run a distance-vector update to exchange information with routers that are reachable over directly connected networks • Information shared is each router’s individual view of network. • Uses Bellman-Ford Algorithm to calculate routing table (min cost to all destinations).

Distance Vector Dynamic Updates • Every router sends a list of its routes to all its neighbors • List contains pairs of: destination network, distance • Receiver replaces/updates entries in its routing table if routing through a neighbor costs less than the current route in its table • Receiver propagates new routes and updates next time it sends out an update • Update Algorithm has well-known shortcomings (we will see an example later)

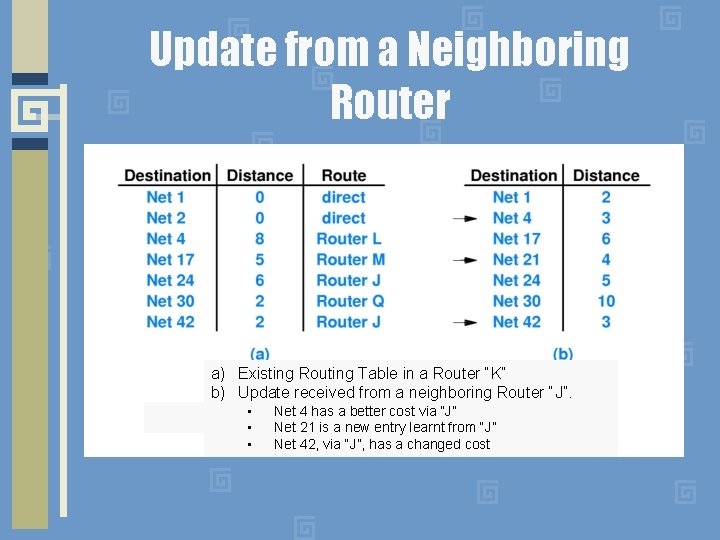

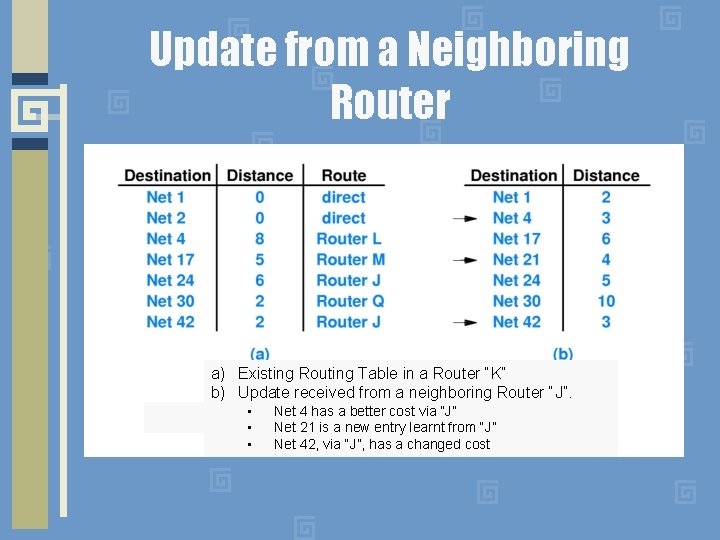

Update from a Neighboring Router a) Existing Routing Table in a Router “K” b) Update received from a neighboring Router “J”. • • • Net 4 has a better cost via “J” Net 21 is a new entry learnt from “J” Net 42, via “J”, has a changed cost

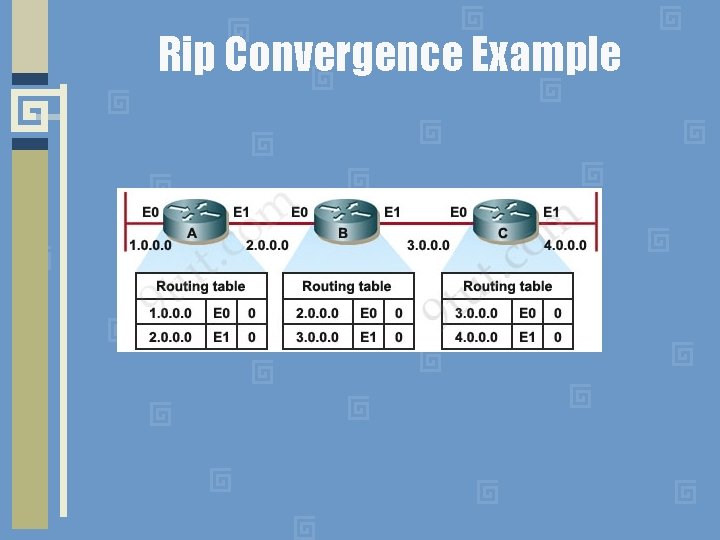

Example of Distance Vector Assume: • link cost is 1 on all hops • all updates occur simultaneously • initially each router only knows its directly connected interfaces -> cost = 0

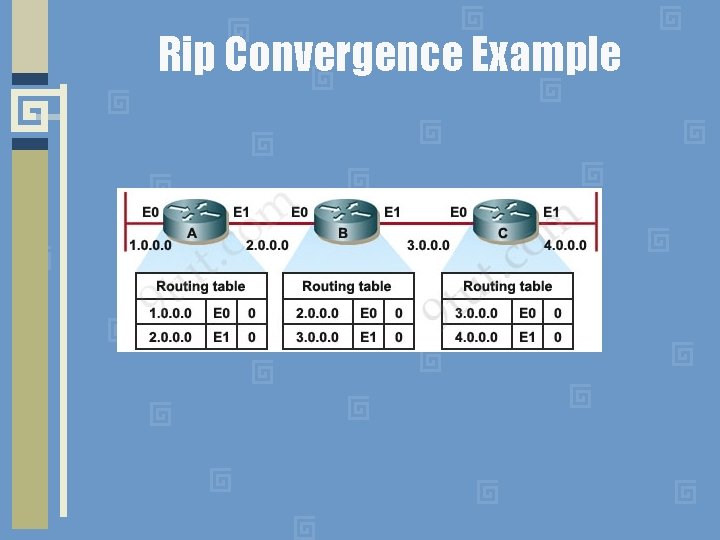

Rip Convergence Example

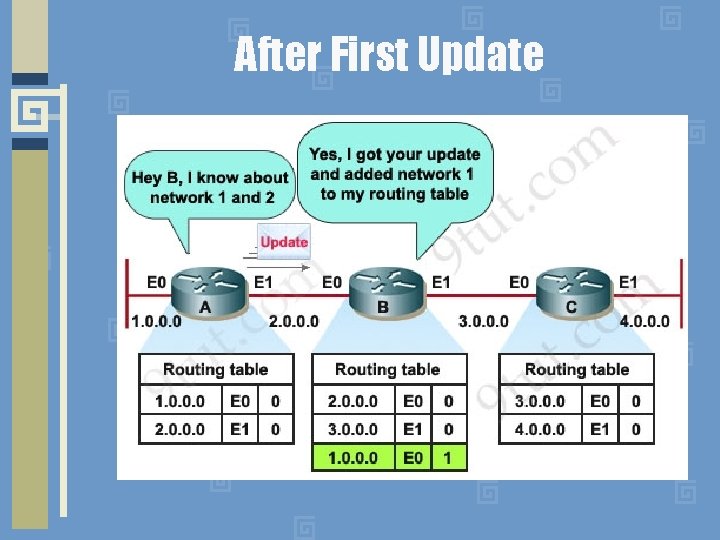

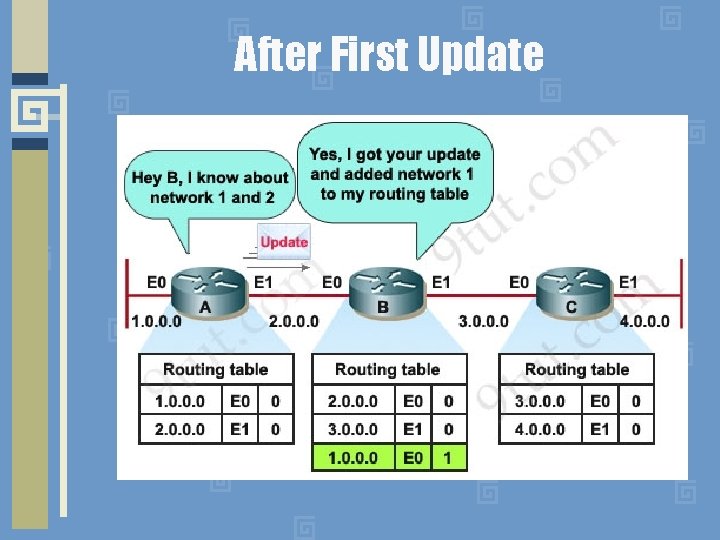

After First Update

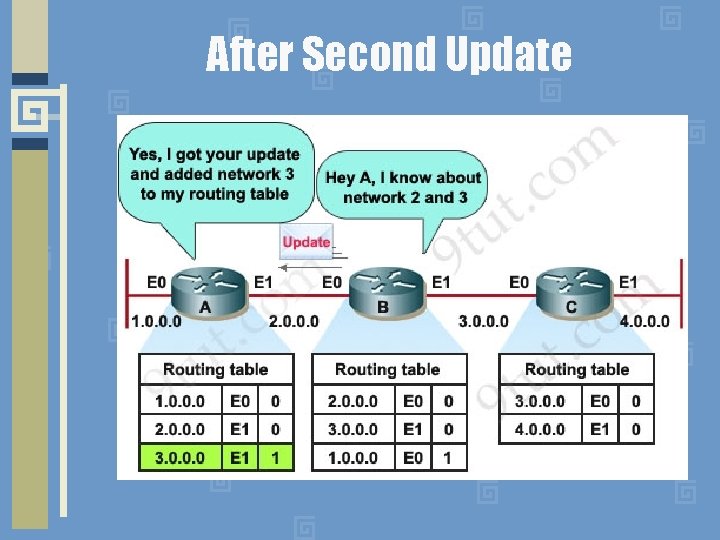

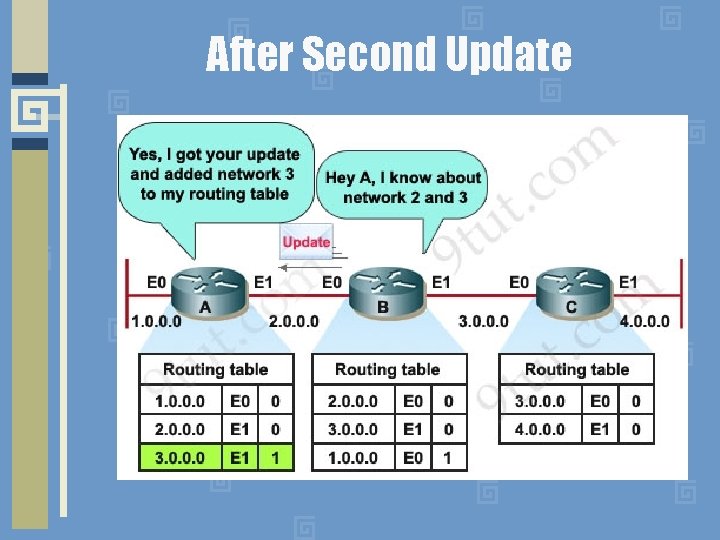

After Second Update

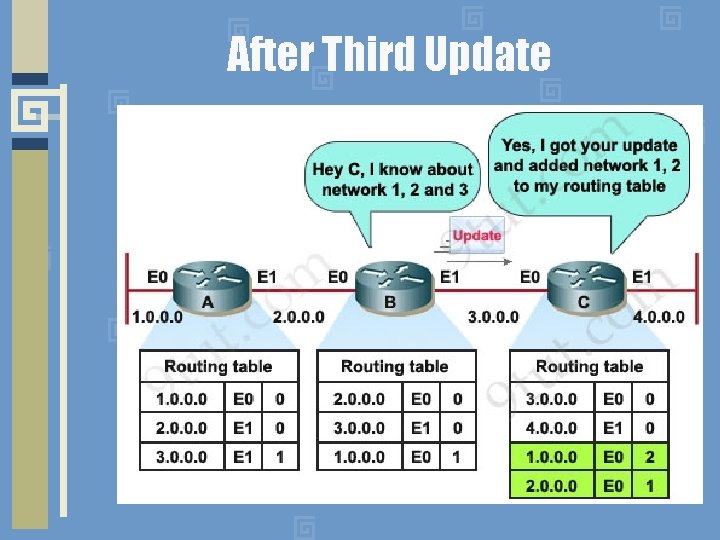

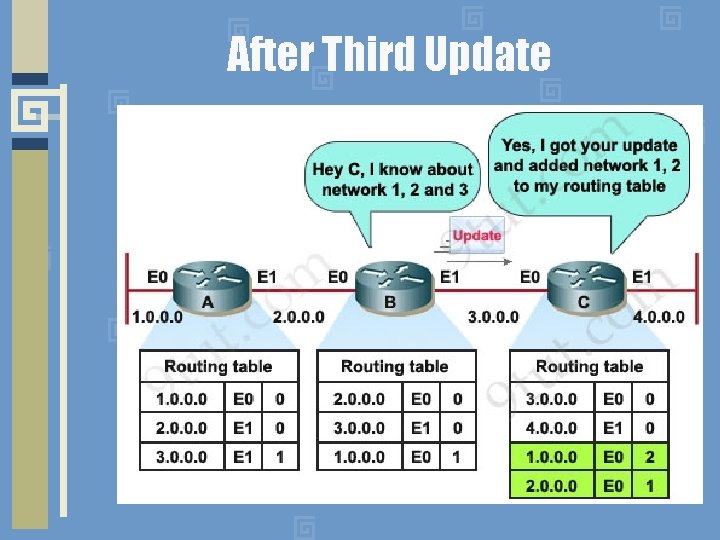

After Third Update

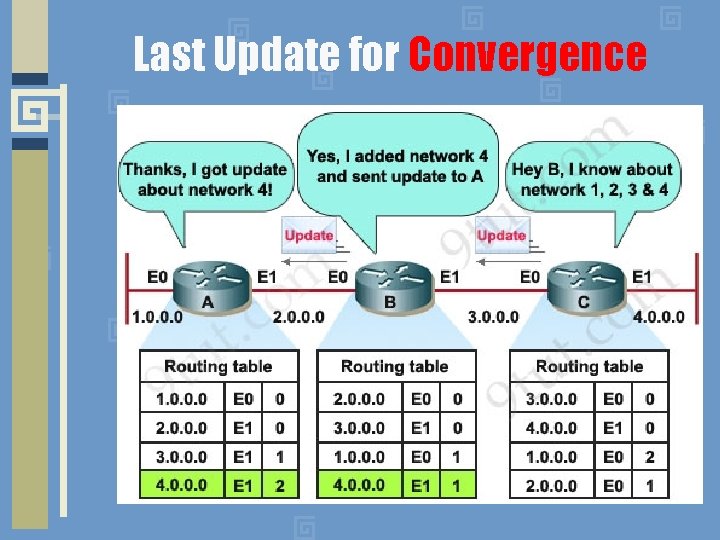

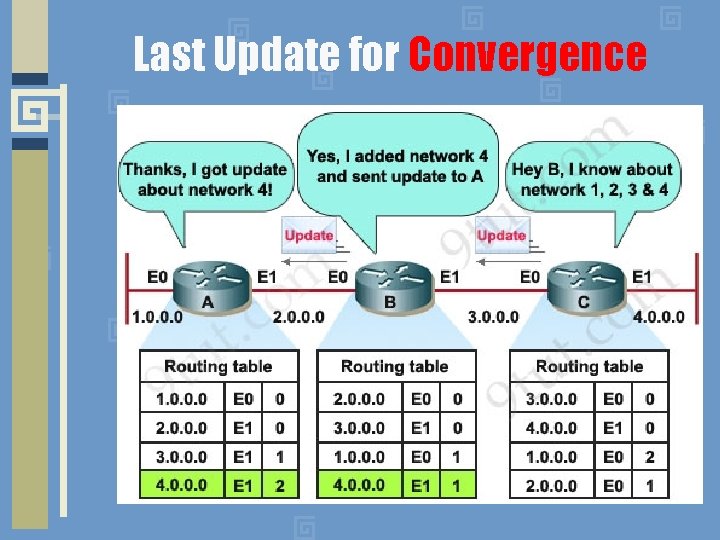

Last Update for Convergence

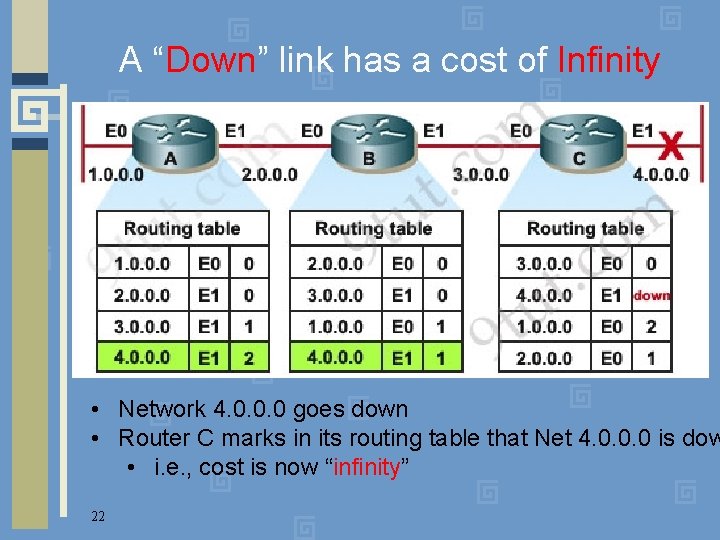

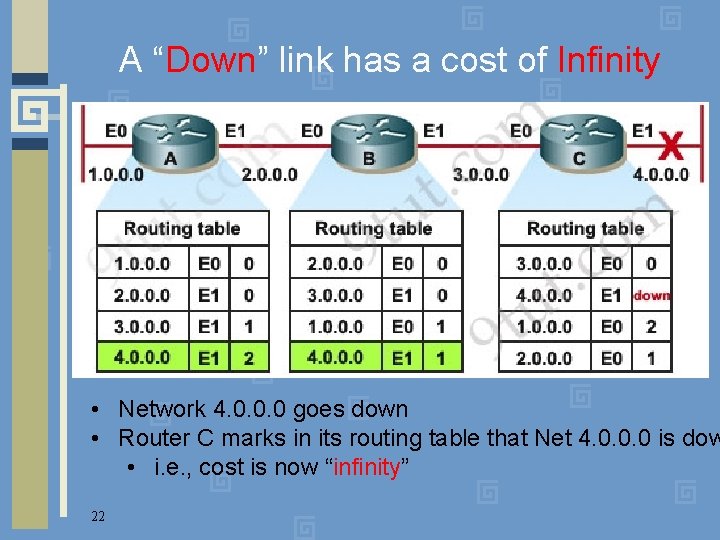

A “Down” link has a cost of Infinity 1 1 • Network 4. 0. 0. 0 goes down • Router C marks in its routing table that Net 4. 0. 0. 0 is dow • i. e. , cost is now “infinity” 22

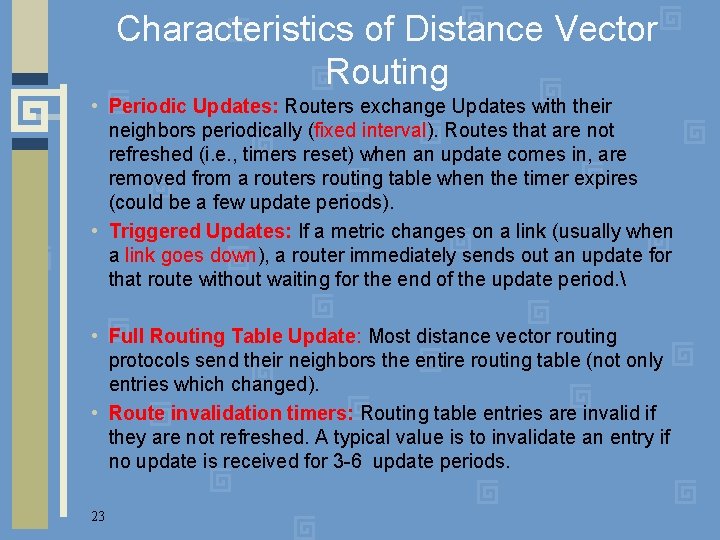

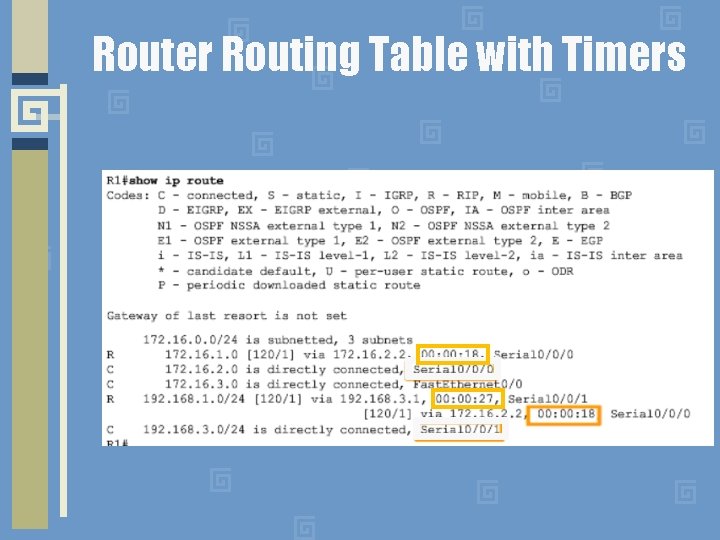

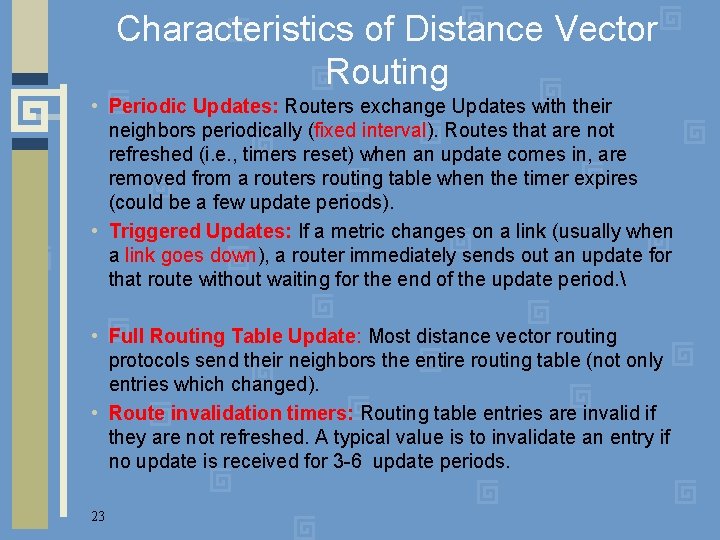

Characteristics of Distance Vector Routing • Periodic Updates: Routers exchange Updates with their neighbors periodically (fixed interval). Routes that are not refreshed (i. e. , timers reset) when an update comes in, are removed from a routers routing table when the timer expires (could be a few update periods). • Triggered Updates: If a metric changes on a link (usually when a link goes down), a router immediately sends out an update for that route without waiting for the end of the update period. • Full Routing Table Update: Most distance vector routing protocols send their neighbors the entire routing table (not only entries which changed). • Route invalidation timers: Routing table entries are invalid if they are not refreshed. A typical value is to invalidate an entry if no update is received for 3 -6 update periods. 23

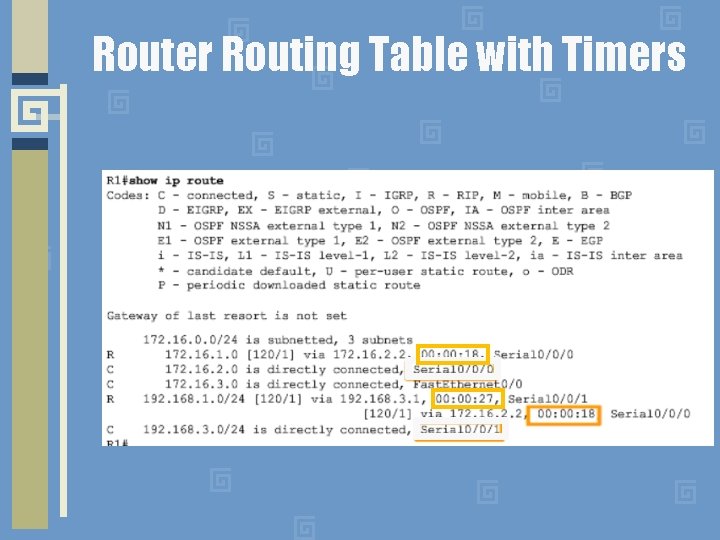

Router Routing Table with Timers

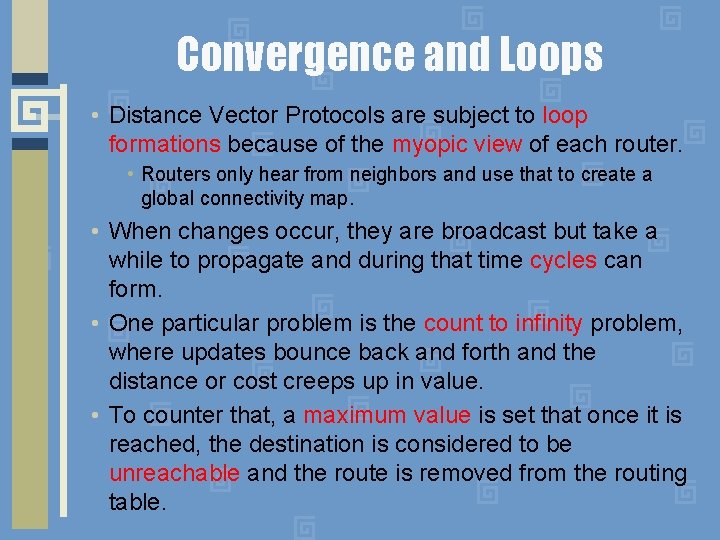

Convergence and Loops • Distance Vector Protocols are subject to loop formations because of the myopic view of each router. • Routers only hear from neighbors and use that to create a global connectivity map. • When changes occur, they are broadcast but take a while to propagate and during that time cycles can form. • One particular problem is the count to infinity problem, where updates bounce back and forth and the distance or cost creeps up in value. • To counter that, a maximum value is set that once it is reached, the destination is considered to be unreachable and the route is removed from the routing table.

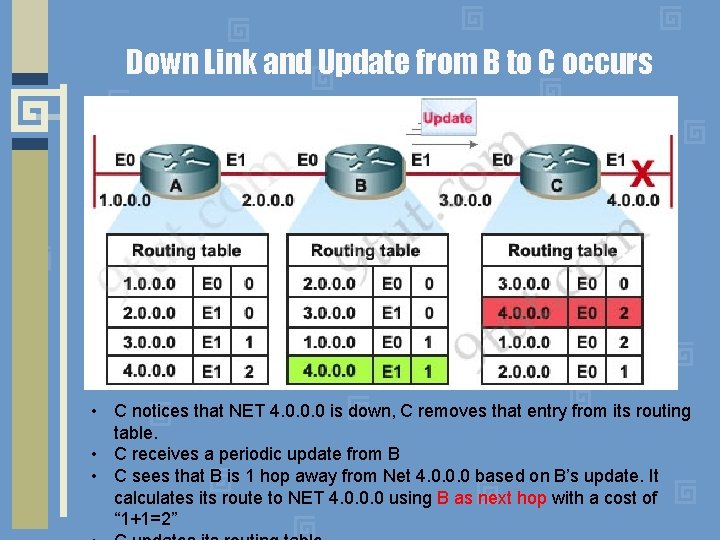

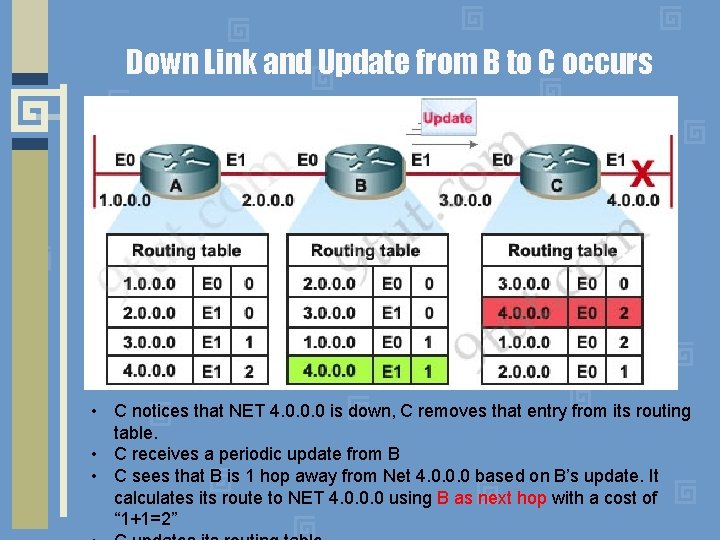

Down Link and Update from B to C occurs • C notices that NET 4. 0. 0. 0 is down, C removes that entry from its routing table. • C receives a periodic update from B • C sees that B is 1 hop away from Net 4. 0. 0. 0 based on B’s update. It calculates its route to NET 4. 0. 0. 0 using B as next hop with a cost of “ 1+1=2”

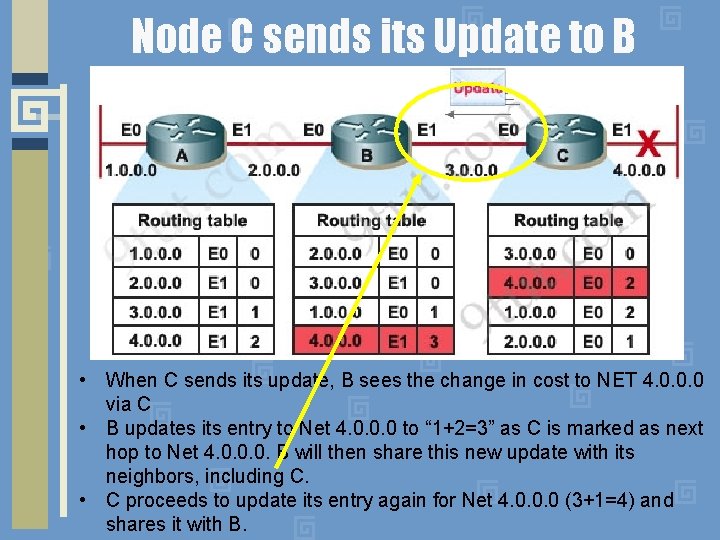

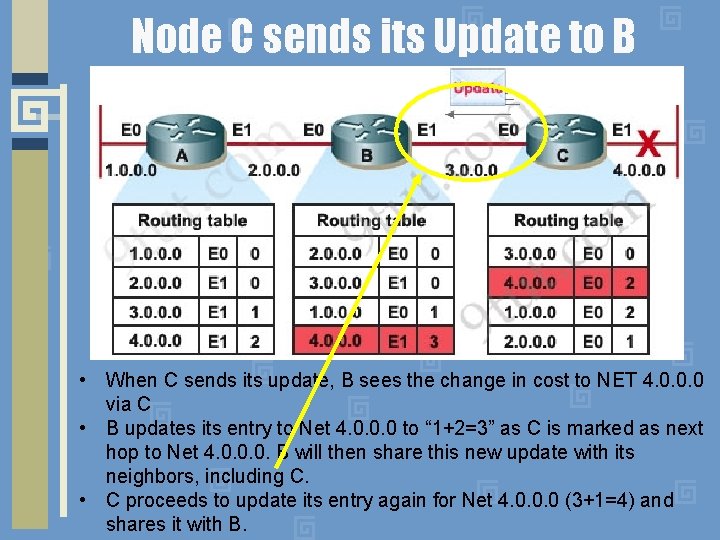

Node C sends its Update to B • When C sends its update, B sees the change in cost to NET 4. 0. 0. 0 via C • B updates its entry to Net 4. 0. 0. 0 to “ 1+2=3” as C is marked as next hop to Net 4. 0. 0. 0. B will then share this new update with its neighbors, including C. • C proceeds to update its entry again for Net 4. 0. 0. 0 (3+1=4) and shares it with B.

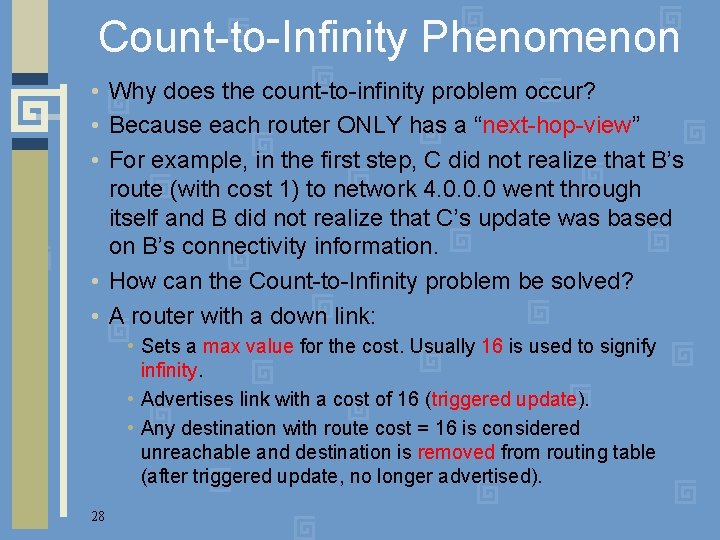

Count-to-Infinity Phenomenon • Why does the count-to-infinity problem occur? • Because each router ONLY has a “next-hop-view” • For example, in the first step, C did not realize that B’s route (with cost 1) to network 4. 0. 0. 0 went through itself and B did not realize that C’s update was based on B’s connectivity information. • How can the Count-to-Infinity problem be solved? • A router with a down link: • Sets a max value for the cost. Usually 16 is used to signify infinity. • Advertises link with a cost of 16 (triggered update). • Any destination with route cost = 16 is considered unreachable and destination is removed from routing table (after triggered update, no longer advertised). 28

How to Prevent Count to Infinity • Enhancements proposed to prevent the Count to Infinity problem and routing loops: 1. Split Horizon 2. Route Poisoning 3. Reverse Poison 4. Hold Down Timers

Split Horizon • A router never sends information about a route in the direction from which the original information came. Routers keep track of which neighbor sent information about a route in its routing table. Updates to that route are never sent to that neighbor, unless the latest update is caused by information from a different neighbor. • Router B never sends Router C updates about NET 4. 0. 0. 0 as C is next hop on path to Net 4. 0. 0. 0 • When NET 4. 0. 0. 0 goes down, C removes the entry from its table. • Updates will no longer include NET 4. 0. 0. 0. • B will remove route to NET 4. 0. 0. 0 when the timer expires for that route in its routing table (received no

Route Poisoning and Poison Reverse • Marking a down link as a cost of infinity. • When NET 4. 0. 0. 0 goes down, router C marks it as “cost = infinity” and advertises the new cost of this network to its neighbors in a TRIGGERED UPDATE. • removes the route from its table • When B gets C’s update, it: • sends a triggered update to all its neighbors with the new cost of infinity for that destination (poison reverse supercedes Split horizon if in use) • removes the route from its table • If SPLIT Horizon is not being used: • B’s update might not get to A before A sends B it’s updates that includes the old information related to the unreachable destination. So: • ……. we must use SPLIT Horizon and or HOLD

Hold Down Timers • After receiving a route poisoning (cost = infinity) for a route from a neighboring router, a router starts a hold-down timer for that route. • During the hold-down timer, the “downed” route is marked. • If the router gets an update from that same neighbor with a new cost (< infinity) within the hold-down timer period, the hold-down timer is removed and the table is updated (route no longer marked). • However, if within the hold-down timer, an update is received for that marked route from another router with a better cost, that update is ignored. • In our example, when router B receives a route poisoning update from router C: • It marks NET 4. 0. 0. 0 as “down” in its routing table and starts the holddown timer for NET 4. 0. 0. 0. • In this period, if it receives an update from C informing that NET 4. 0. 0. 0 is recovered then B will accept that information, remove the hold-down timer and reinstitute that destination in its routing table. • But if B receives an update from A informing it that NET 4. 0. 0. 0 can be reached in X hops (X < infinity), that update will be ignored. • When the hold-down timer expires a new update for that route from a

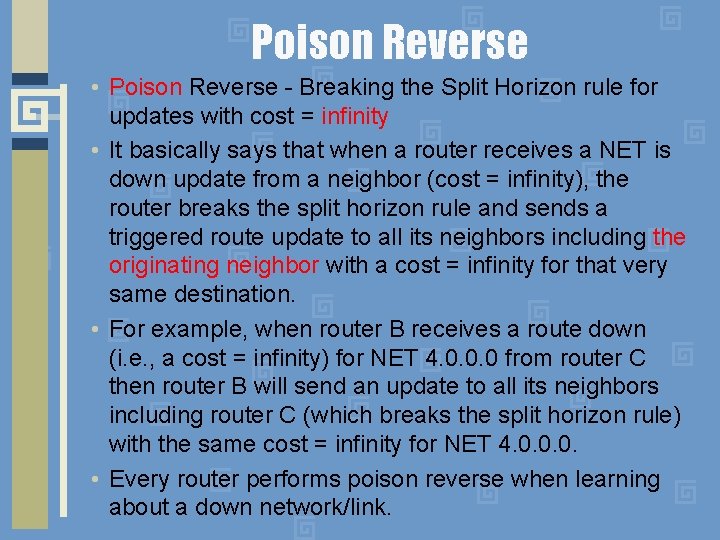

Poison Reverse • Poison Reverse - Breaking the Split Horizon rule for updates with cost = infinity • It basically says that when a router receives a NET is down update from a neighbor (cost = infinity), the router breaks the split horizon rule and sends a triggered route update to all its neighbors including the originating neighbor with a cost = infinity for that very same destination. • For example, when router B receives a route down (i. e. , a cost = infinity) for NET 4. 0. 0. 0 from router C then router B will send an update to all its neighbors including router C (which breaks the split horizon rule) with the same cost = infinity for NET 4. 0. 0. 0. • Every router performs poison reverse when learning about a down network/link.

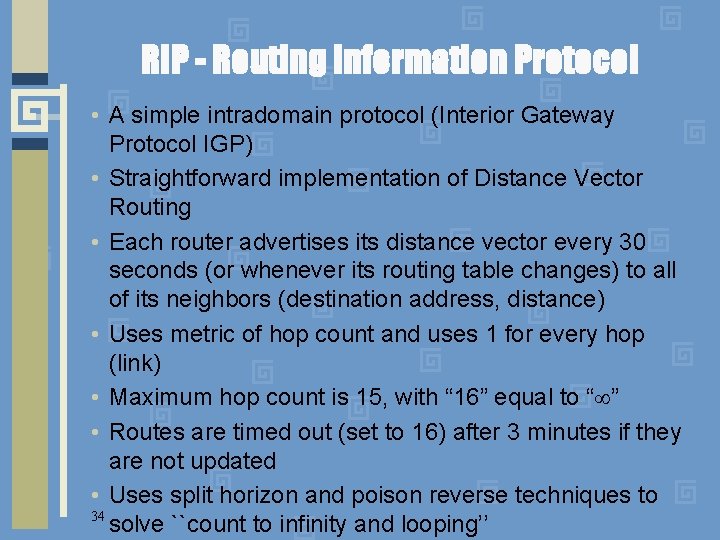

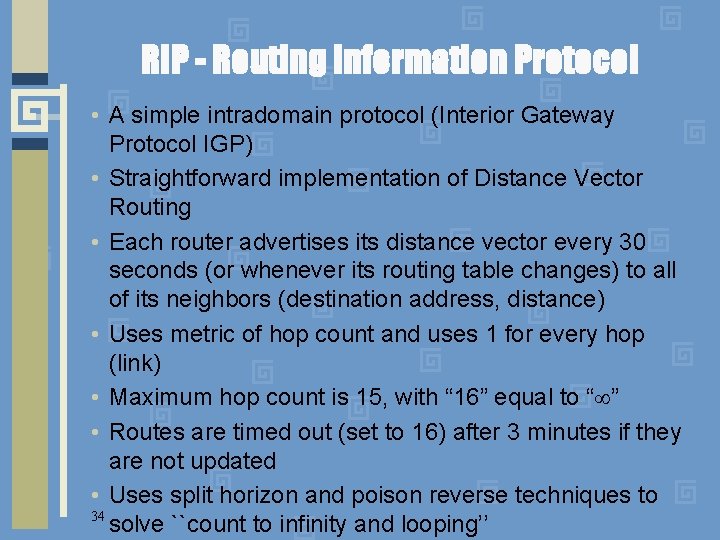

RIP - Routing Information Protocol • A simple intradomain protocol (Interior Gateway Protocol IGP) • Straightforward implementation of Distance Vector Routing • Each router advertises its distance vector every 30 seconds (or whenever its routing table changes) to all of its neighbors (destination address, distance) • Uses metric of hop count and uses 1 for every hop (link) • Maximum hop count is 15, with “ 16” equal to “ ” • Routes are timed out (set to 16) after 3 minutes if they are not updated • Uses split horizon and poison reverse techniques to 34 solve ``count to infinity and looping’’

Two Forms of RIP Active • Used by routers • Broadcasts routing updates periodically • Uses incoming messages to update routes Passive • Used by “non forwarding” hosts • Uses incoming update messages to change route table – changes overwrite ICMP redirects

RIPv 2 • Route Update includes subnet mask • Authentication supported • Explicit next-hop information • Messages are multicast • IP multicast address for RIP is 224. 0. 0. 9

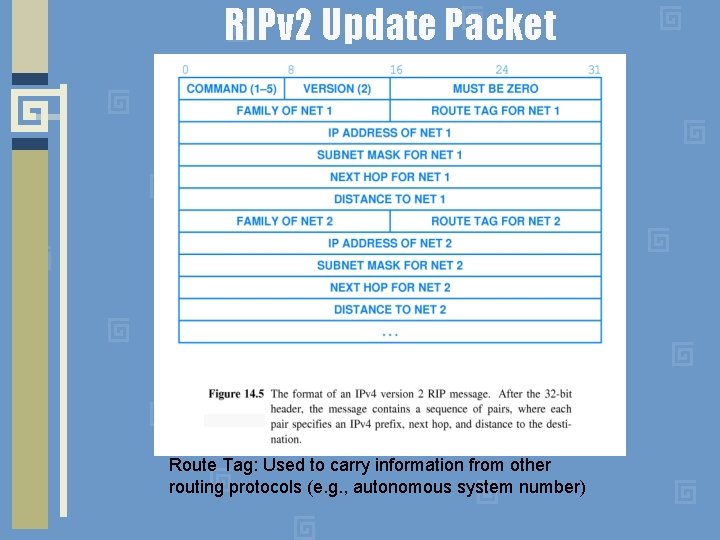

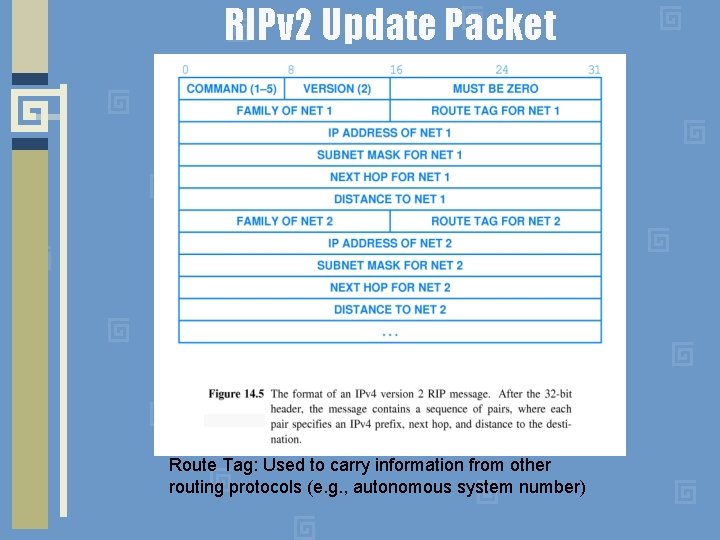

RIPv 2 Update Packet Route Tag: Used to carry information from other routing protocols (e. g. , autonomous system number)

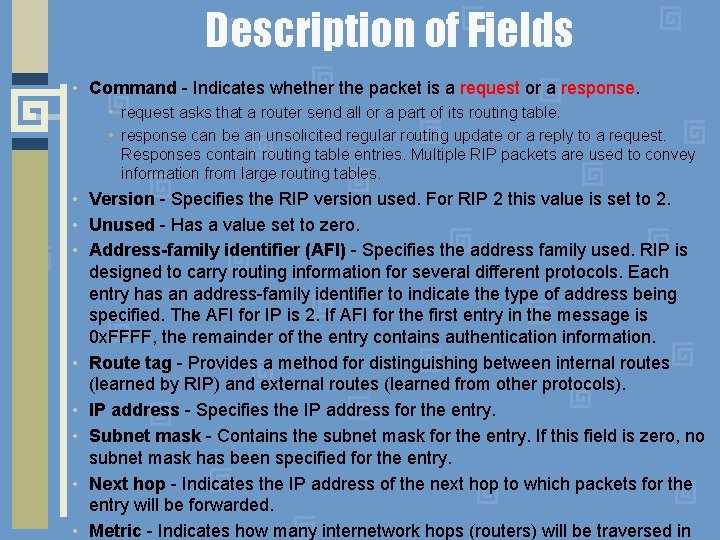

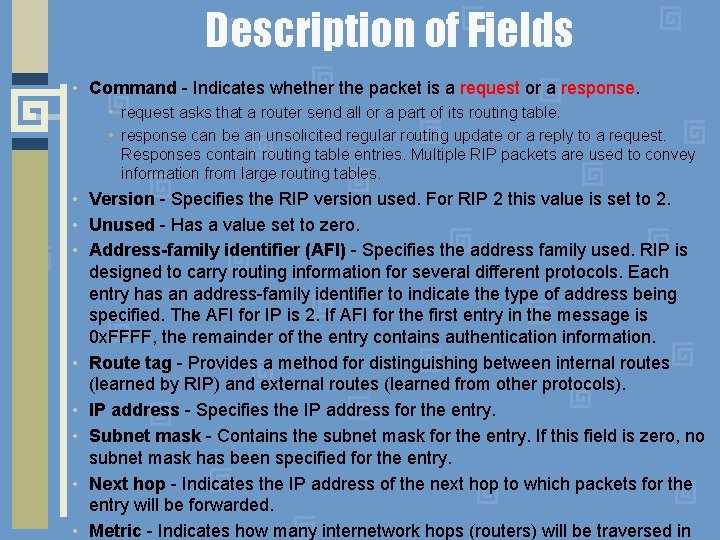

Description of Fields • Command - Indicates whether the packet is a request or a response. • request asks that a router send all or a part of its routing table. • response can be an unsolicited regular routing update or a reply to a request. Responses contain routing table entries. Multiple RIP packets are used to convey information from large routing tables. • Version - Specifies the RIP version used. For RIP 2 this value is set to 2. • Unused - Has a value set to zero. • Address-family identifier (AFI) - Specifies the address family used. RIP is designed to carry routing information for several different protocols. Each entry has an address-family identifier to indicate the type of address being specified. The AFI for IP is 2. If AFI for the first entry in the message is 0 x. FFFF, the remainder of the entry contains authentication information. • Route tag - Provides a method for distinguishing between internal routes (learned by RIP) and external routes (learned from other protocols). • IP address - Specifies the IP address for the entry. • Subnet mask - Contains the subnet mask for the entry. If this field is zero, no subnet mask has been specified for the entry. • Next hop - Indicates the IP address of the next hop to which packets for the entry will be forwarded. • Metric - Indicates how many internetwork hops (routers) will be traversed in

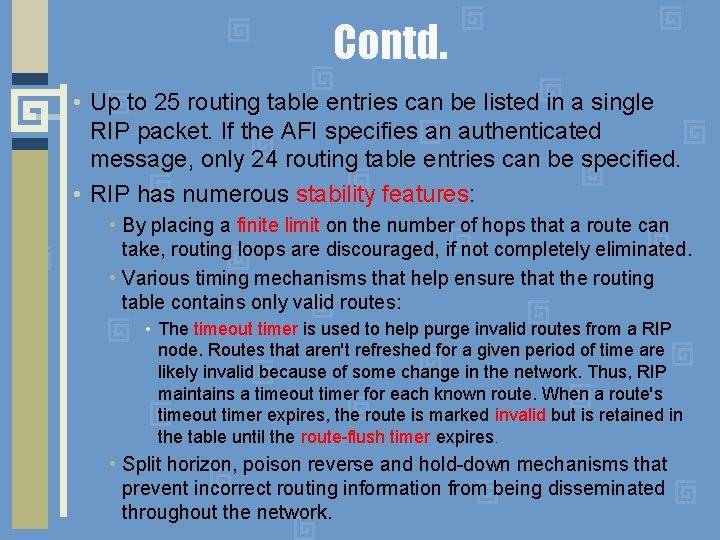

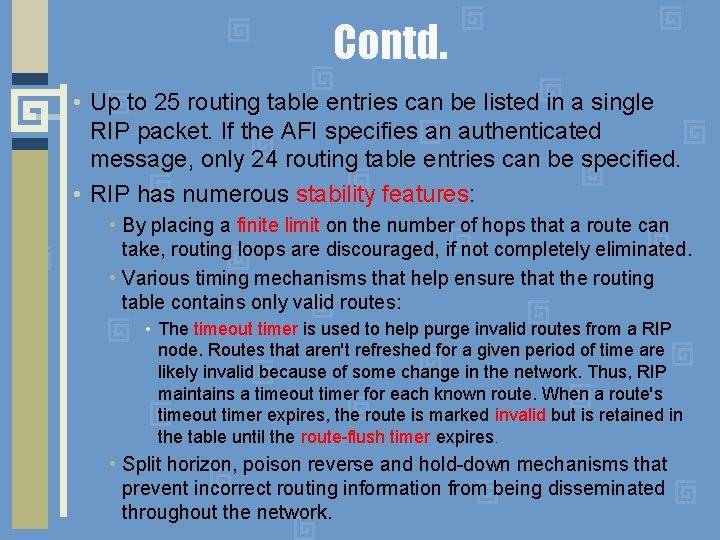

Contd. • Up to 25 routing table entries can be listed in a single RIP packet. If the AFI specifies an authenticated message, only 24 routing table entries can be specified. • RIP has numerous stability features: • By placing a finite limit on the number of hops that a route can take, routing loops are discouraged, if not completely eliminated. • Various timing mechanisms that help ensure that the routing table contains only valid routes: • The timeout timer is used to help purge invalid routes from a RIP node. Routes that aren't refreshed for a given period of time are likely invalid because of some change in the network. Thus, RIP maintains a timeout timer for each known route. When a route's timeout timer expires, the route is marked invalid but is retained in the table until the route-flush timer expires. • Split horizon, poison reverse and hold-down mechanisms that prevent incorrect routing information from being disseminated throughout the network.

RIP Message Exchange • Uses UDP transport • Dedicated port for RIP is UDP port 520 • Two types of command messages: • Request messages • used to ask neighboring nodes for an update • Response messages • contains an update 40

Routing with RIP • Initialization: Send a request packet on all interfaces requesting routing tables from neighboring routers: • RIPv 2 uses multicast address 224. 0. 0. 9 • Request received: Routers that receive above request send their entire routing table • Response received: Update the routing table • Regular routing updates: Every 30 seconds, send all or part of the routing tables to every neighbor in a response message • Triggered Updates: Whenever the metric for a route changes, send updated route. 41

RIP Summary • Slow convergence • Low overhead • Limited to 15 hops (max cost, i. e. , infinity =16) • Only uses local information from immediate neighbors for routing decisions - relies on propagation of information for global view of network