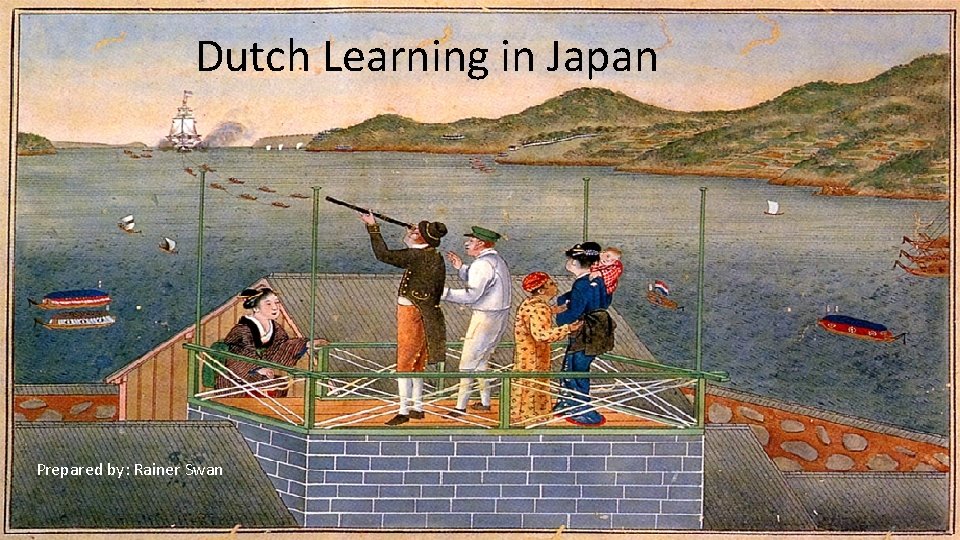

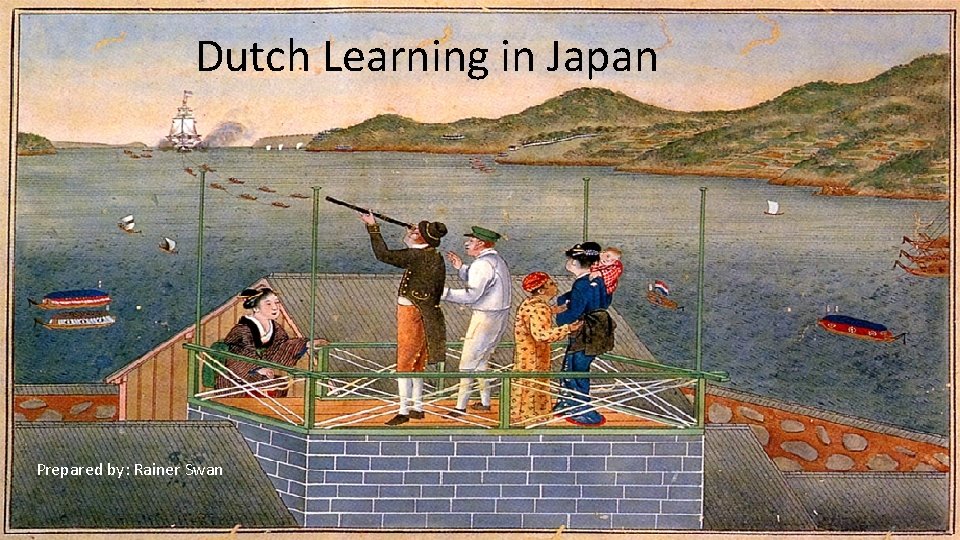

Dutch Learning in Japan Dutch Learning Rangaku in

- Slides: 29

Dutch Learning in Japan Dutch Learning “Rangaku” in 17 th and 18 th Century-Japan Prepared by: Daniel Salazar, Justin Sanchez, Rainer Swan, Jonathan Van Lysebettens, Ken Williams, Hunter Wood Prepared by: Rainer Swan

The Japanese refer to “Dutch Learning” as “Rangaku” or learning from the West. The Dutch were the largest influence on the Japanese because they didn’t push religion and were viewed as fair in trade dealings They learned Japanese and taught Dutch to their Japanese “friends” and exposed them to what was happening outside their homeland Thus a lot of opinions the Japanese have are a result of Dutch influence

Brief History

Some brief history: - In 1543 Japan is “discovered” by Portuguese traders - Shortly the Jesuits follow and benefit from friendship and patronage of Oda Nobunaga, though Buddhist priests are hostile to their efforts to convert Japanese - In 1587 Hideyoshi (successor to Nobunaga) issues an edict banning all priests in Japan and declares Japan to be a “divine land” (shinkoku) and Catholicism a “devilish law” and claims the Jesuits are inciting converts to destroy Shinto and Buddhist temples - Jesuits continue to quietly conduct religion services

- In 1592 and 1593 Spanish Catholic missionaries cause Japanese to believe the padres are preparing the ground for eventual military conquest by Spain and/or Portugal - Hideyoshi orders six Spanish Franciscan monks arrested and 18 of their converts crucified and missionary buildings burned - That effectively ends the Spanish and Portuguese efforts at trade but Jan 1614 Tokugawa Ieyasu formally bans all Catholic missions from Japan - In 1624 all Spanish are deported…the previous year the English, unable to compete with the Dutch, voluntarily leave

- In 1598 Dutch ships leave Amsterdam and Rotterdam heading to the East Indies - In 1600 a foreign ship foundered on the coast of Bunga in present day Oita Prefecture, Kyushu. This was the ship “De Liefde” from the Netherlands - The pilot of the Dutch ship with 23 starving crew was William Adams (aka Miura Anjin) an English pilot of the Dutch ship and he was welcomed into the court of Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu - Adams is the subject of the novel “Shogun” by James Clavell - In 1609 the Dutch, who had heard from Adams, sent two ships to Japan and received permission to establish a trading post in Hirado, Nagasaki

- The British also established a post there and competition soon flared among the Portuguese, Dutch, British, Chinese and Japanese traders - The Dutch established their trade (or “factory”) as part of the East India trade company and initially traded cloth with the Japanese in exchange for silk and silver - A big condition placed on the Dutch to keep doing trade was to spy on activities of the Spanish and Portuguese. Any information gleaned was signed by an interpreter and a Dutch director, and then sent to the seat of the Shogunate in Edo

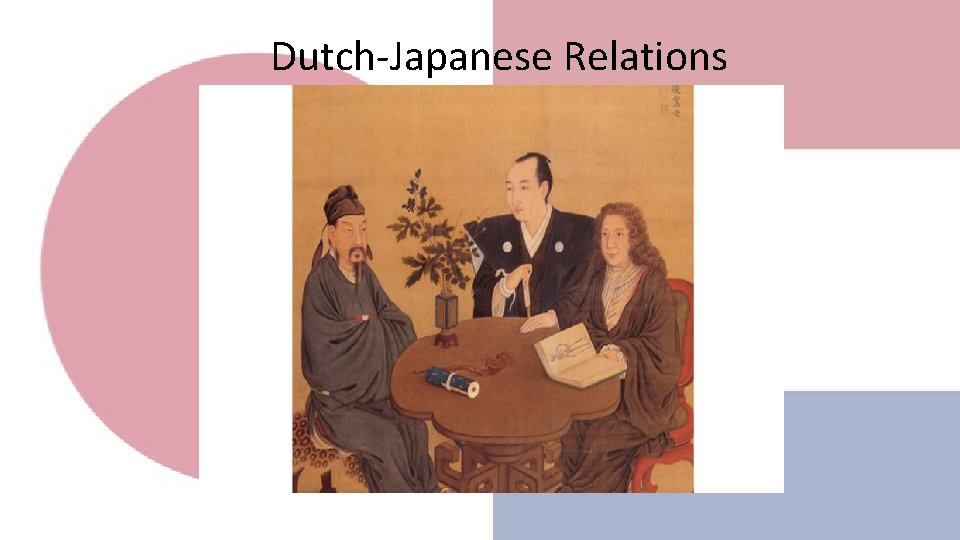

Dutch-Japanese Relations

- Dutch made annual trips to Edo to update the Shogun every year on world events. This 1, 250 kilometer trip usually took 5 -8 weeks - The Dutch were asked to helped solidify the Shogun’s ban on Christianity in Japan and provide information on all Catholic priests - In 1637 the Shimabura Rebellion occurred whereby the Shogunate decided to expel the Portuguese - The Dutch gained the trust of the Japanese by bombarding the location where the insurgents were holed up - This gained the Dutch a monopoly on European trade with Japan

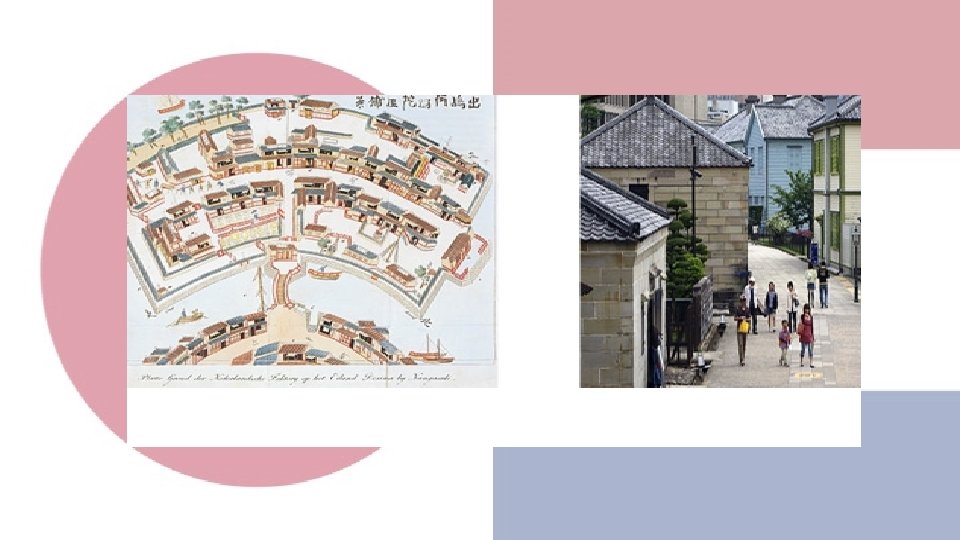

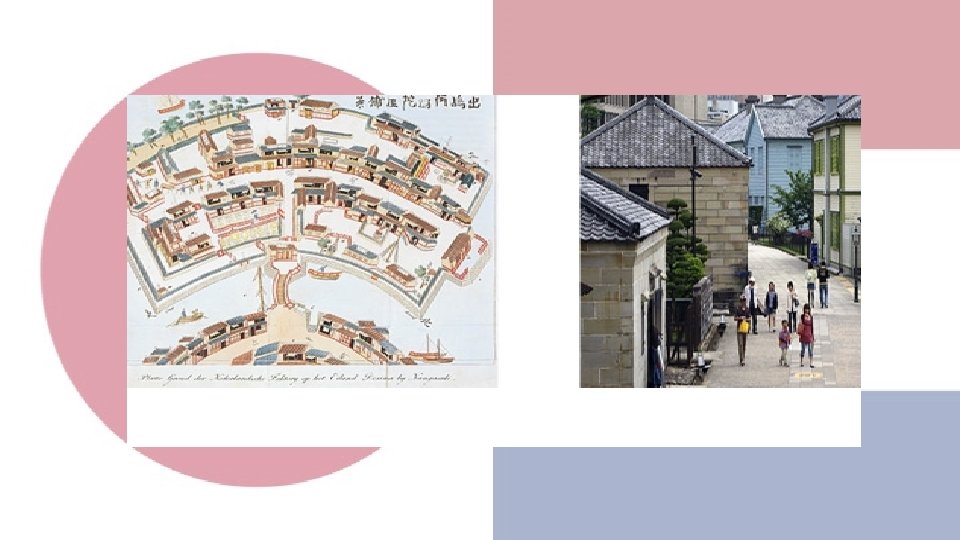

- Dejima was little more than a vegetable garden and a few farm animals with some basic buildings - No more than a “musket shot” from Nagasaki proper - Connected by a narrow bridge, heavily guarded to prevent unsanctioned crossings - Placards warned the island’s inhabitants weren’t permitted to leave unless authorized, usually to go to Nagasaki’s pleasure quarters - The least reputable females in Japan were alone and “suffered to…serve them”

- Island life reflected that of incarceration due to heavy restrictions on movement from the island to mainland Japan. Typically the Dutch numbered no more than 20. - Despite their lack of interest in proselytizing, they were constantly watched by resident guards and interpreters and subjected to “endless humiliations and indignities” - Women were not allowed on the island - Children of Dutch men and Japanese women were not permitted to stay in Japan. - A former Dutch resident said the Japanese were “foul and fearful. ” - Dutch stayed busy learning Japanese or teaching Japanese to a very select few - All in all, the poor Dutch were said to be treated worse than European Jews during the Middle Ages

- As time went on, the Japanese decided to further limit trade with the foreigners - In 1685 the Shogunate imposed a limit on trade, limiting the number of Dutch ships allowed entry into Nagasaki - Beginning in 1715 only two ships per year were allowed in - In 1790 this was further reduced to one per year in an attempt to further isolate Japan from the foreigners - Between 1715 to 1790 trade volume was reduced from 3, 000 kanme (11. 25 tons) in silver to 700 kanme (2. 625 tons)

Domestic Sphere

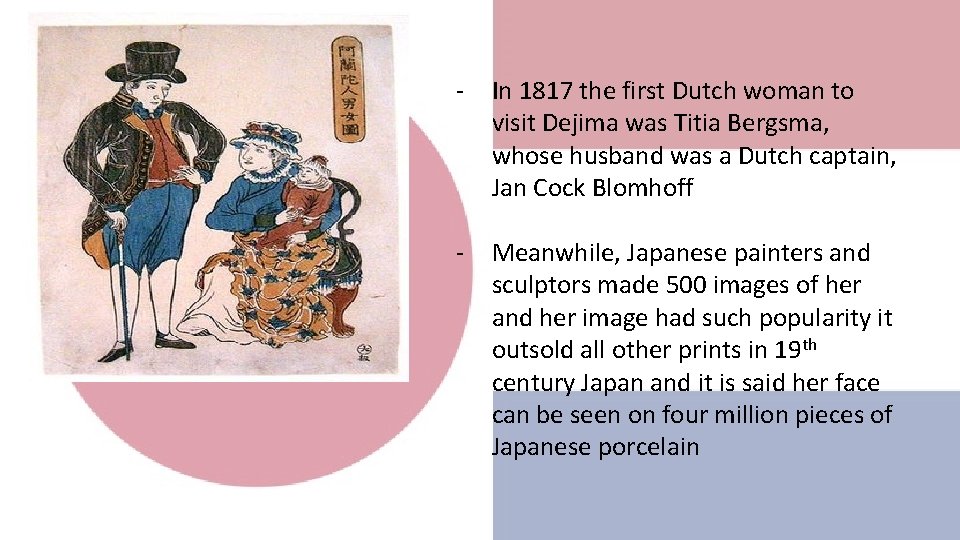

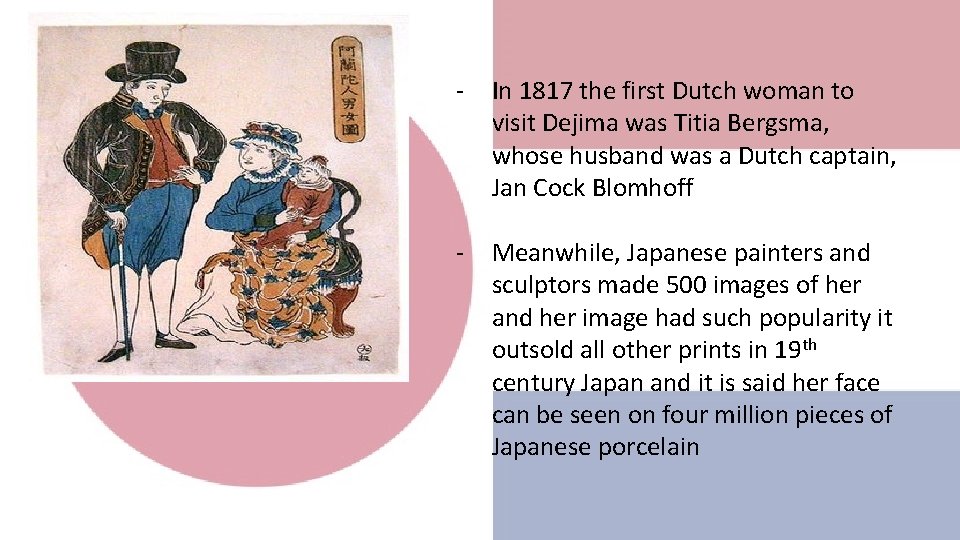

- In 1817 the first Dutch woman to visit Dejima was Titia Bergsma, whose husband was a Dutch captain, Jan Cock Blomhoff - Meanwhile, Japanese painters and sculptors made 500 images of her and her image had such popularity it outsold all other prints in 19 th century Japan and it is said her face can be seen on four million pieces of Japanese porcelain

- No foreign women were supposed to be allowed, but the governor of Nagasaki allowed her to enter the island - Five weeks later, when shogun Tokagawa Ienari (1787 -1837) found out, he ordered her to leave. She went back to Holland, never to see her husband again

Japanese Usage of Dutch Technology

- More than 700 Dutch ships visited Japan between 1621 and 1847 - After anchoring at harbor, the Dutch ships underwent inspection and then were allowed to unload their cargo - Merchants gathered to bid on the cargo being imported, which included printed cotton cloth, velvet, pepper, sugar, glass and books - The Dutch introduced the Japanese to clocks and microscopes and pumps, spectacles, maps, globes, birds, dogs, donkeys and other “rarities” - The Dutch (actually a German assigned with the Dutch) started a “medical school” to train Japanese in western medicine and was allowed to examine cadavers to translate the organs into Japanese

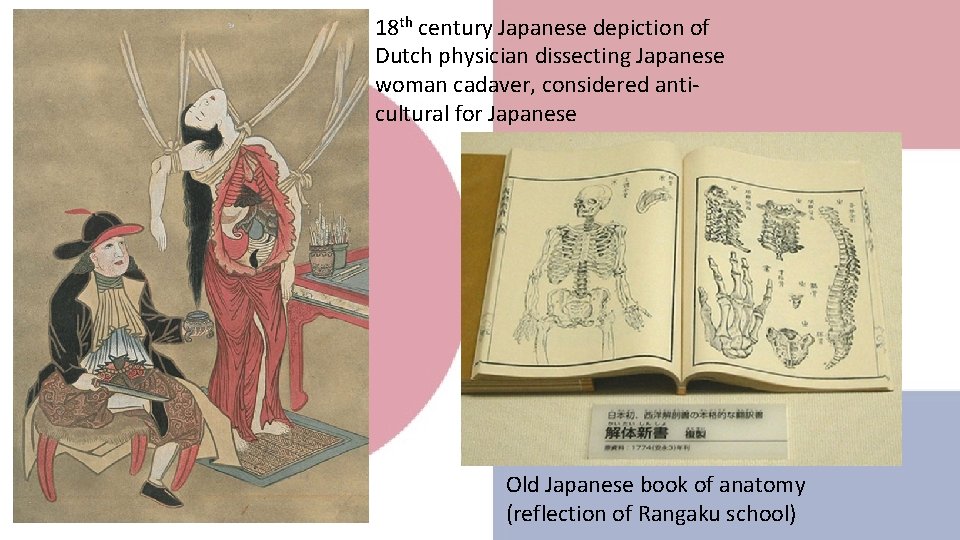

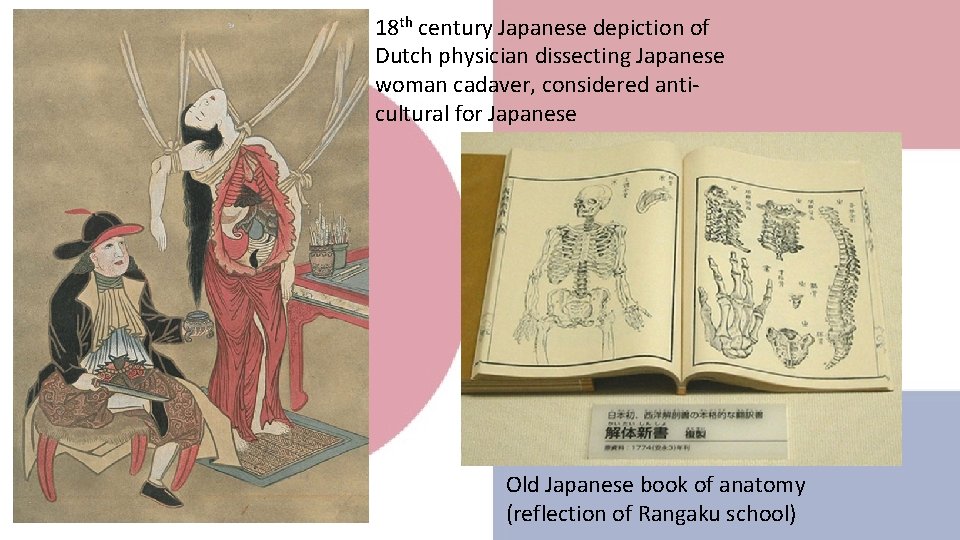

18 th century Japanese depiction of Dutch physician dissecting Japanese woman cadaver, considered anticultural for Japanese Old Japanese book of anatomy (reflection of Rangaku school)

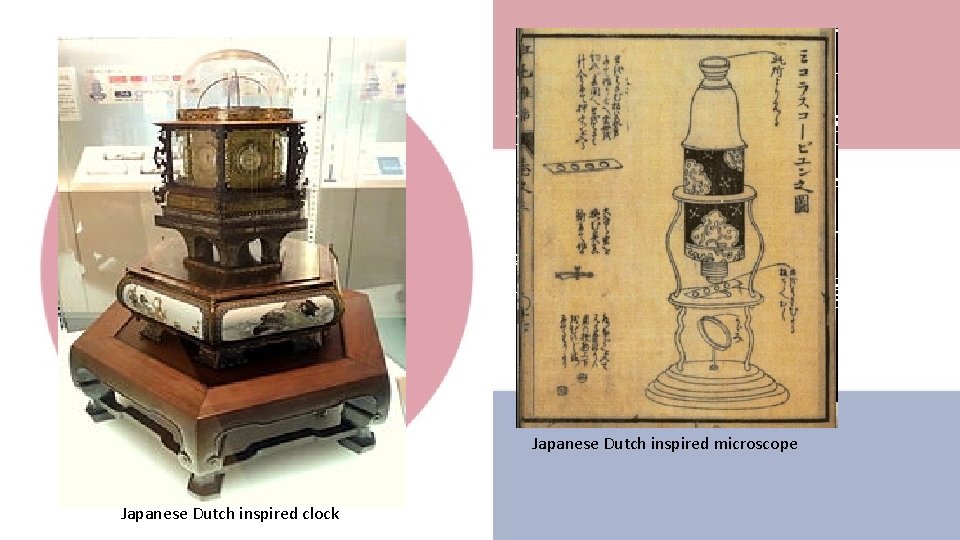

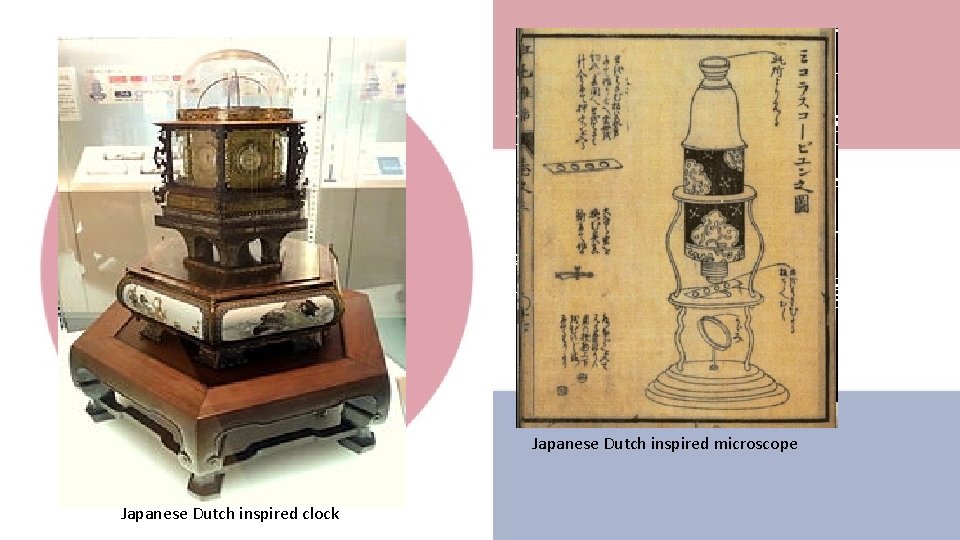

Japanese Dutch inspired microscope Japanese Dutch inspired clock

- Exported Japanese items were silver, raw silk, copper, camphor, porcelain, paper, lacquerware, among other items - Much Japanese porcelain and cook ware was copied by the Dutch. They were highly valued. Many items were used as coffee-urns, vases, bowls and plates - Japanese porcelain was superior to Chinese, and on a par or better than European…especially items in the colors blue and red

- In matters of exchange and commerce, the Dutch provided extensive knowledge - Medicine, science (particularly astronomy), natural history (botany and gardening), navigational charts and history of the world outside Japan - The Dutch were among the best suited to teach Japanese nautical skills - Between 1800 -1829 schools helped spread “Dutch knowledge” even further - Japanese rangakusha (experts in Dutch studies) were thus aware of the danger posed by the West, and how science was applied to the technology of weaponry - The Dutch also educated the Japanese on differences in exchange rates, impacting trade in gold, primarily, but in other goods as well

- Dutch served as interpreters in some exchanges with the Americans, and also trained and educated the Japanese about steam driven engines…especially in the use of modern warfare instruments (guns, artillery, exploding shells) - It was a big deal to be chosen as a Japanese interpreter working for the Dutch, and in effect, serve as a spy for the shogun - The Japanese learned a good deal about the latest in Western mathematics and physics, and the latest in the art of navigation from the Dutch - Additionally, the Japanese learned much that refuted their knowledge of anatomy and treatment of disease, feeling in many ways that the West was much further along in the study of the human body

- The descriptive observations of the West were praised by Japanese scholars interested in such matters - The Dutch discussed European ports and trade routes, exposing the Japanese to celestial navigation and centers of power - The Dutch got into some trouble loaning their flag to be flown onboard other vessels that were allowed into port under the guise of being a Dutch vessel - In 1837 the USS Morrison, under the 28 -year old merchant Charles King tried to present 4 letters of goodwill to the Japanese but was driven away by Japanese cannon fire at Uruga (Yokosuka, near Tokyo Bay) - Though he had three Japanese shipwreck survivors onboard to be repatriated, they elected to go back to Canton

- The Dutch served as teachers and provided the West solid interaction with the Japanese for over 200 years, especially during the Tokugawa era - They explained western hospitals and the state of knowledge and disease - They outlined techniques for painting and printing with copper plates - Based on Dutch description of the first hot air balloon flight in 1783, the Japanese were able to demonstrate the same principals using Japanese paper

- The French Revolution of 1789 exerted a grave effect on the Netherlands and in 1799 the Dutch East India Company was disbanded - From that point onward, Dutch influence began to wane

References Dutch Learning in 17 th and 18 th Century Japan 1. 2. 3. 4. Cook, Harold J. Matters of Exchange, Commerce, Medicine and Science in the Dutch Golden Age. Yale College. 2007 Feifer, George. Breaking Open Japan. New York: Harper Collins, 2006 Gordon, Andrew. A Modern History of Japan, New York: Oxford University Press, 2014 (45, 66 -68, 75, 84) Hallam, Henry. Introduction to Literature in the Fifteenth, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, Vol 1. London: John Murray. 1837 5. Huffman, James L. Modern Japan - A History in Documents. New York: Oxford University Press. 2011 6. Joost, Jonker. Voyages and Travels Mainly During the 16 th and 17 th Centuries, Vol I. Westminster: Archibald Constable & Co, Ltd. 1903 7. Mariyat, Joseph. History of Pottery and Porcelain. London: Albemarle Street. 1850 8. Mc. Omie, William. The Opening of Japan, 1853 -1855. Globe Oriental, Ltd. Kent, UK 2006 9. Meshens, Ad. Practical Mathematics in a Commercial Metropolis. Antwerp Press. 2013 10. Preble, Henry, Rear Admiral, U. S. Navy. The Opening of Japan, A Diary of Discovery in the Far East, 1853 -1856. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman. 1962, (11, 33) 11. http: //afe. easia. columbia. edu/main_pop/kpct/kp_tokugawa. htm 12. http: //japan. nlembassy. org/you-and-netherlands/dutch-japanese-relations. html 13. https: //www. britannica. com/event/rangaku