Dry Mantle Melting and the Origin of Basaltic

Dry Mantle Melting and the Origin of Basaltic Magma GEOS 508 Lec 14 -15 -16

Mantle melting l l l Needs special condition to melt, usually solid; Melt fractions usually low, under 2% at any given time; Regardless of melting conditions, yields one or another variety of basaltic (low silica) melts - andesites, dacites, do not come out of the mantle;

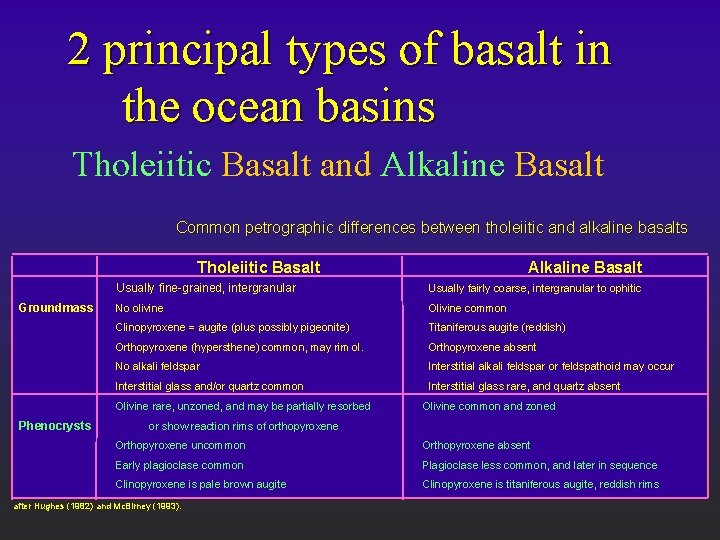

2 principal types of basalt in the ocean basins Tholeiitic Basalt and Alkaline Basalt Common petrographic differences between tholeiitic and alkaline basalts Tholeiitic Basalt Groundmass Usually fine-grained, intergranular Usually fairly coarse, intergranular to ophitic No olivine Olivine common Clinopyroxene = augite (plus possibly pigeonite) Titaniferous augite (reddish) Orthopyroxene (hypersthene) common, may rim ol. Orthopyroxene absent No alkali feldspar Interstitial alkali feldspar or feldspathoid may occur Interstitial glass and/or quartz common Interstitial glass rare, and quartz absent Olivine rare, unzoned, and may be partially resorbed Phenocrysts Alkaline Basalt Olivine common and zoned or show reaction rims of orthopyroxene Orthopyroxene uncommon Orthopyroxene absent Early plagioclase common Plagioclase less common, and later in sequence Clinopyroxene is pale brown augite Clinopyroxene is titaniferous augite, reddish rims after Hughes (1982) and Mc. Birney (1993).

Each is chemically distinct Evolve via FX as separate series along different paths l l Tholeiites are generated at mid-ocean ridges F Also generated at oceanic islands, subduction zones Alkaline basalts generated at ocean islands F Also at subduction zones

Sources of mantle material l Ophiolites F Slabs of oceanic crust and upper mantle F Thrust at subduction zones onto edge of continent l l l Dredge samples from oceanic fracture zones Nodules and xenoliths in some basalts Kimberlite xenoliths F Diamond-bearing pipes blasted up from the mantle carrying numerous xenoliths from depth

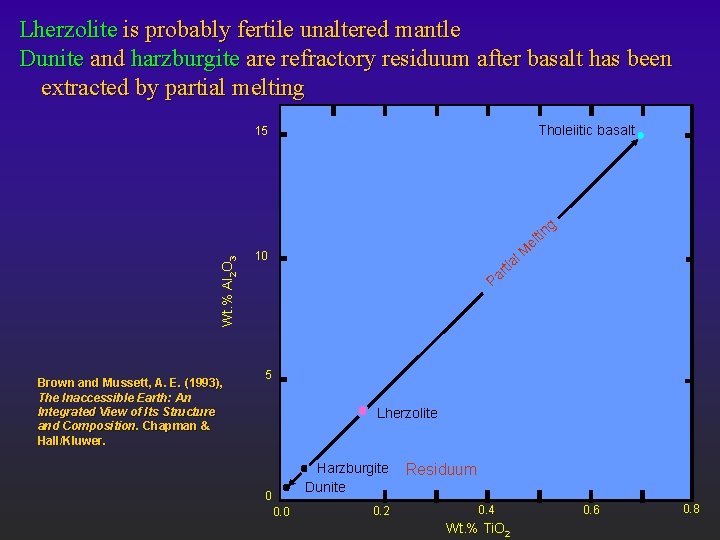

Lherzolite is probably fertile unaltered mantle Dunite and harzburgite are refractory residuum after basalt has been extracted by partial melting Tholeiitic basalt 15 Wt. % Al 2 O 3 g Brown and Mussett, A. E. (1993), The Inaccessible Earth: An Integrated View of Its Structure and Composition. Chapman & Hall/Kluwer. l. M tr ia Pa 10 tin el 5 Lherzolite Harzburgite Dunite 0 0. 2 Residuum 0. 4 Wt. % Ti. O 2 0. 6 0. 8

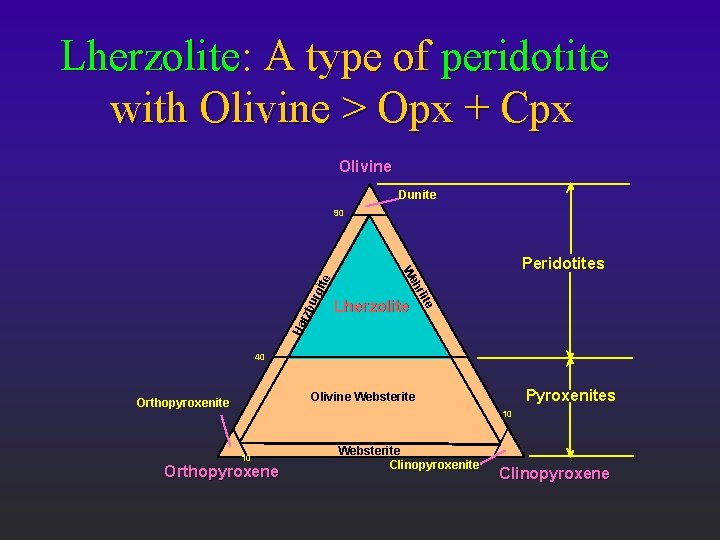

Lherzolite: A type of peridotite with Olivine > Opx + Cpx Olivine Dunite urg Ha Lherzolite hr rzb Peridotites We ite 90 40 Pyroxenites Olivine Websterite Orthopyroxenite 10 10 Orthopyroxene Websterite Clinopyroxene

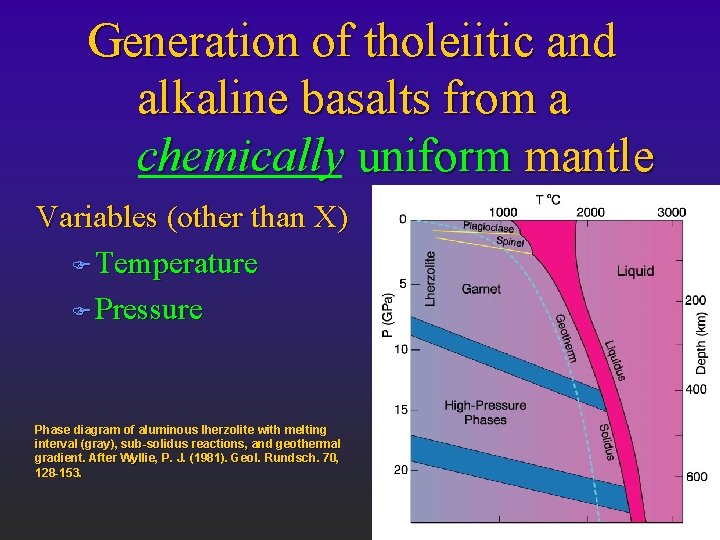

Phase diagram for aluminous 4 -phase lherzolite: Al-phase = l Plagioclase F shallow (< 30 km) l Spinel F 30 -80 l km Garnet F 80 -400 l km Si ® VI coord. F Phase diagram of aluminous lherzolite with melting interval (gray), sub-solidus reactions, and > 400 km geothermal gradient. After Wyllie, P. J. (1981). Geol. Rundsch. 70, 128 -153.

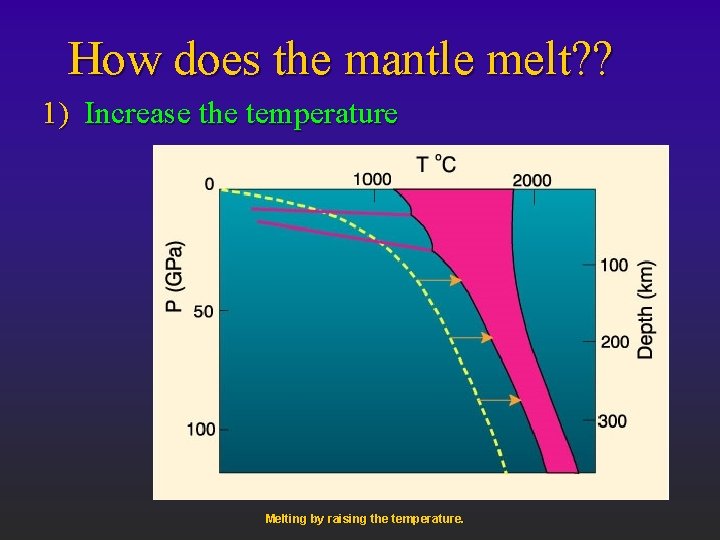

How does the mantle melt? ? 1) Increase the temperature Melting by raising the temperature.

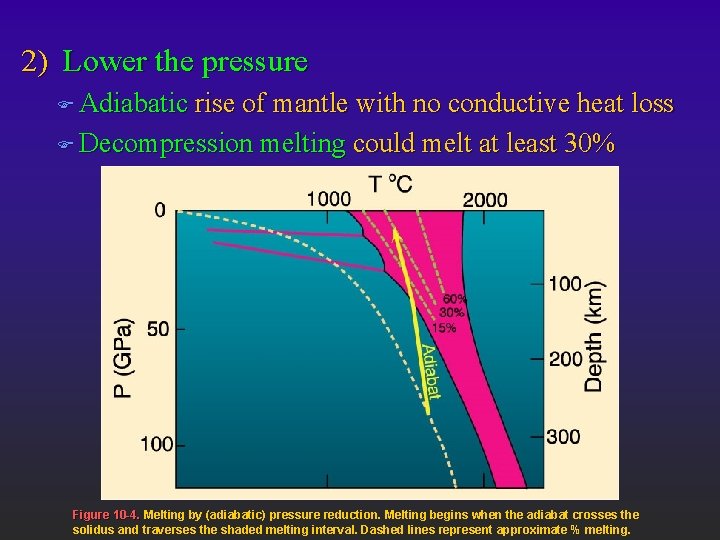

2) Lower the pressure F Adiabatic rise of mantle with no conductive heat loss F Decompression melting could melt at least 30% Figure 10 -4. Melting by (adiabatic) pressure reduction. Melting begins when the adiabat crosses the solidus and traverses the shaded melting interval. Dashed lines represent approximate % melting.

HW 7 l l Use p. MELTS to determine if the sub SWUS upwelling mantle would melt along an adiabat that contains the PT point of 14500 C and 15 kbar. A typical composition of the SWUS mantle is given via a San Carlos peridotite; calculate the fraction of melt and phases in equilibrium with the liquid? What is the composition and melt fraction at 10 kbar (at the Moho), assume 1390 C?

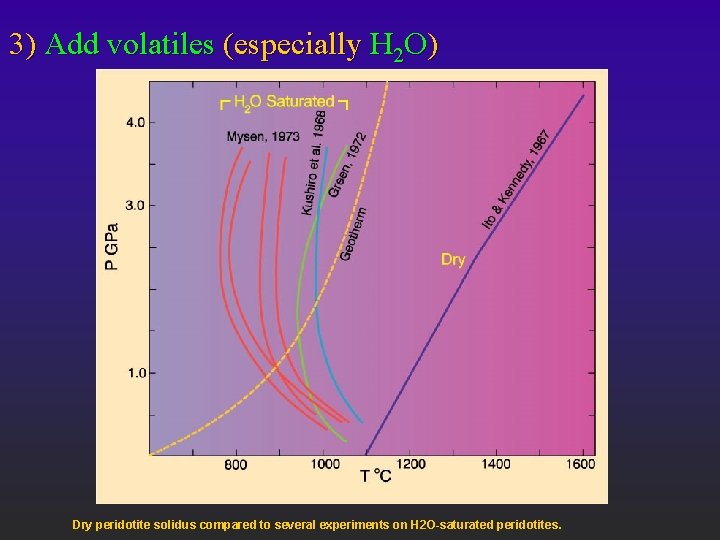

3) Add volatiles (especially H 2 O) Dry peridotite solidus compared to several experiments on H 2 O-saturated peridotites.

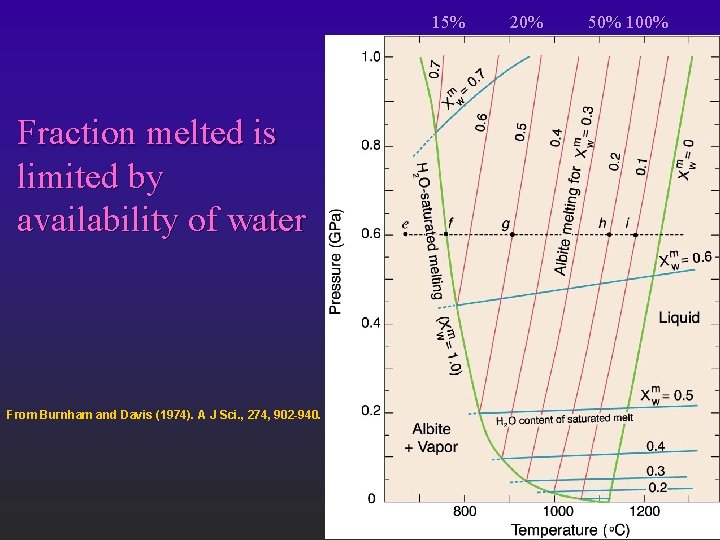

15% Fraction melted is limited by availability of water From Burnham and Davis (1974). A J Sci. , 274, 902 -940. 20% 50% 100%

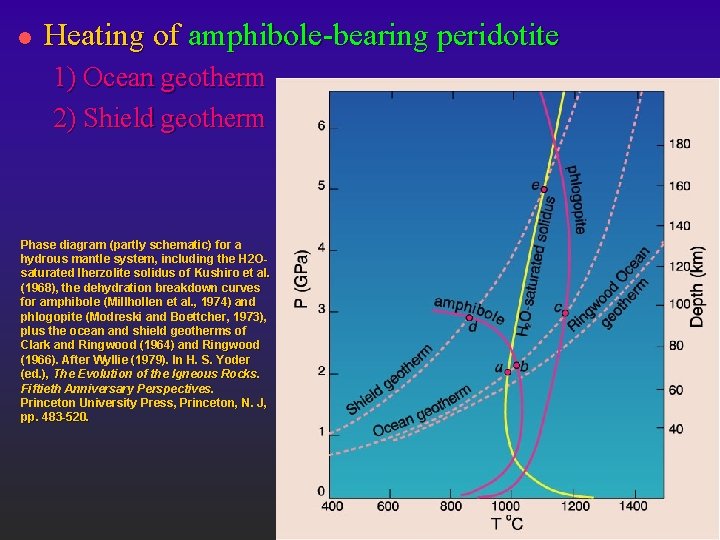

l Heating of amphibole-bearing peridotite 1) Ocean geotherm 2) Shield geotherm Phase diagram (partly schematic) for a hydrous mantle system, including the H 2 Osaturated lherzolite solidus of Kushiro et al. (1968), the dehydration breakdown curves for amphibole (Millhollen et al. , 1974) and phlogopite (Modreski and Boettcher, 1973), plus the ocean and shield geotherms of Clark and Ringwood (1964) and Ringwood (1966). After Wyllie (1979). In H. S. Yoder (ed. ), The Evolution of the Igneous Rocks. Fiftieth Anniversary Perspectives. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N. J, pp. 483 -520.

Melts can be created under realistic circumstances l l l Plates separate and mantle rises at midocean ridges F Adibatic rise ® decompression melting Hot spots ® localized plumes of melt Fluid fluxing may give LVL F Also important in subduction zones and other settings

Generation of tholeiitic and alkaline basalts from a chemically uniform mantle Variables (other than X) F Temperature F Pressure Phase diagram of aluminous lherzolite with melting interval (gray), sub-solidus reactions, and geothermal gradient. After Wyllie, P. J. (1981). Geol. Rundsch. 70, 128 -153.

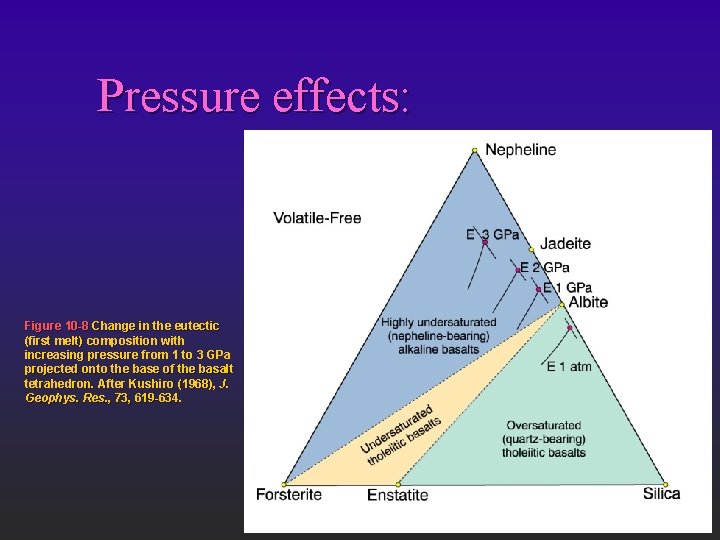

Pressure effects: Figure 10 -8 Change in the eutectic (first melt) composition with increasing pressure from 1 to 3 GPa projected onto the base of the basalt tetrahedron. After Kushiro (1968), J. Geophys. Res. , 73, 619 -634.

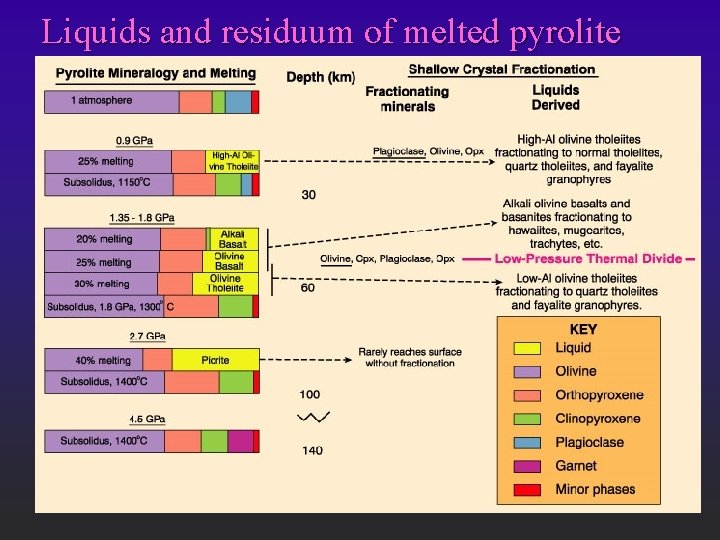

Liquids and residuum of melted pyrolite

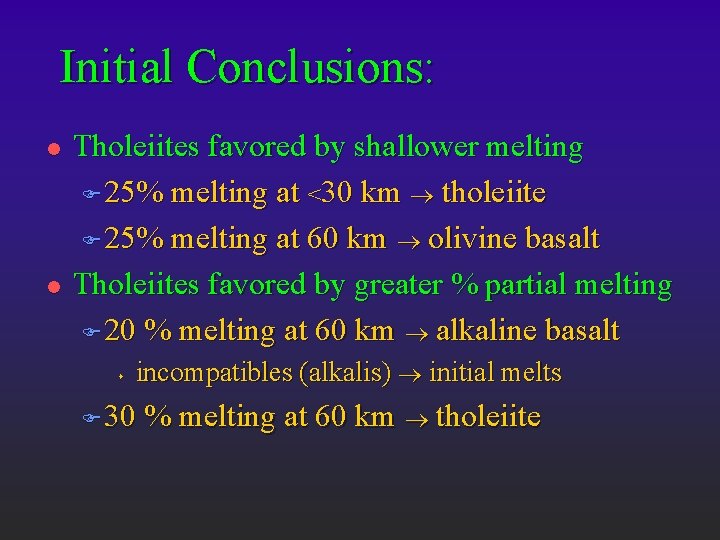

Initial Conclusions: l l Tholeiites favored by shallower melting F 25% melting at <30 km ® tholeiite F 25% melting at 60 km ® olivine basalt Tholeiites favored by greater % partial melting F 20 % melting at 60 km ® alkaline basalt s incompatibles (alkalis) ® initial melts F 30 % melting at 60 km ® tholeiite

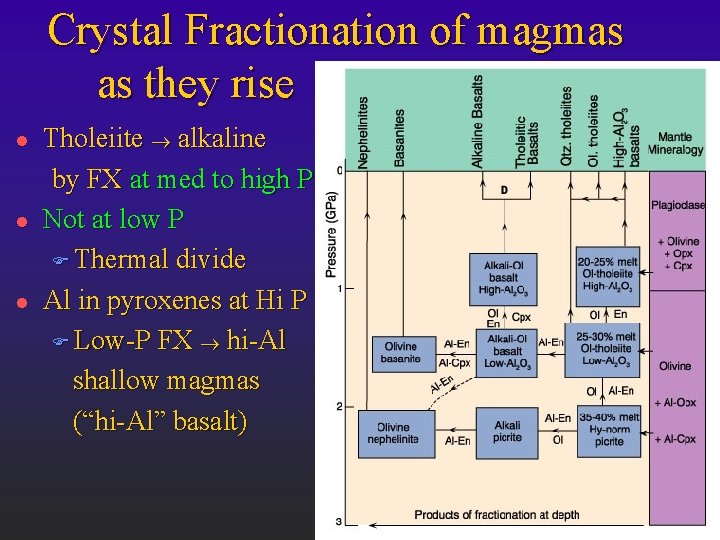

Crystal Fractionation of magmas as they rise l l l Tholeiite ® alkaline by FX at med to high P Not at low P F Thermal divide Al in pyroxenes at Hi P F Low-P FX ® hi-Al shallow magmas (“hi-Al” basalt)

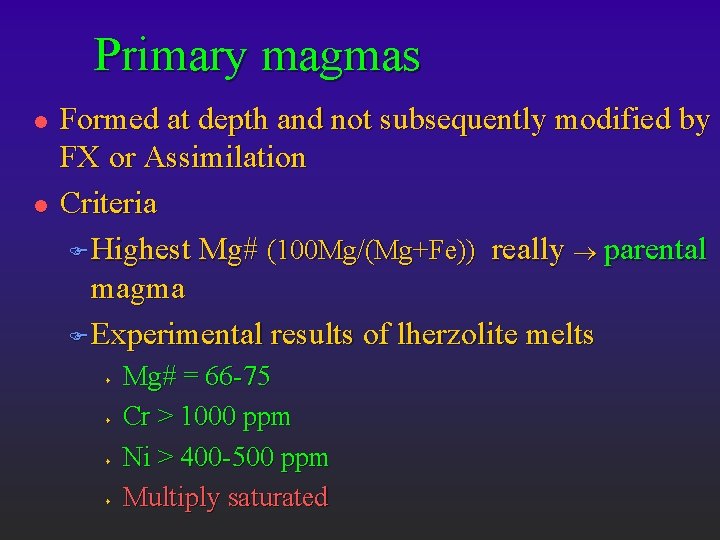

Primary magmas l l Formed at depth and not subsequently modified by FX or Assimilation Criteria F Highest Mg# (100 Mg/(Mg+Fe)) really ® parental magma F Experimental results of lherzolite melts s s Mg# = 66 -75 Cr > 1000 ppm Ni > 400 -500 ppm Multiply saturated

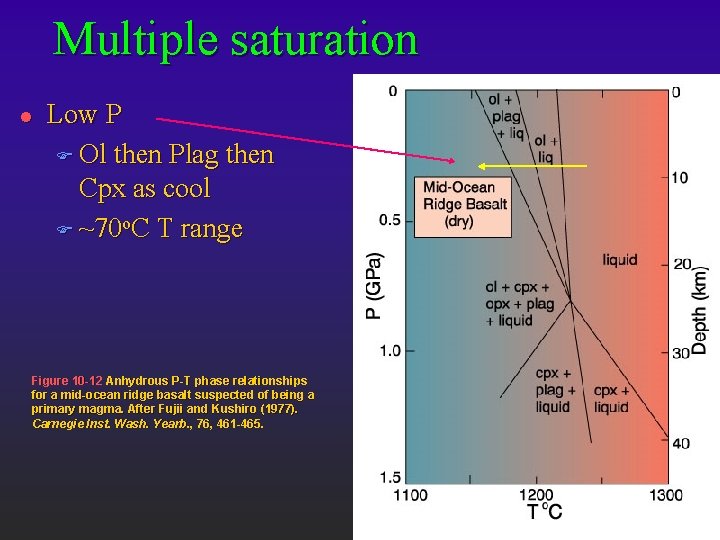

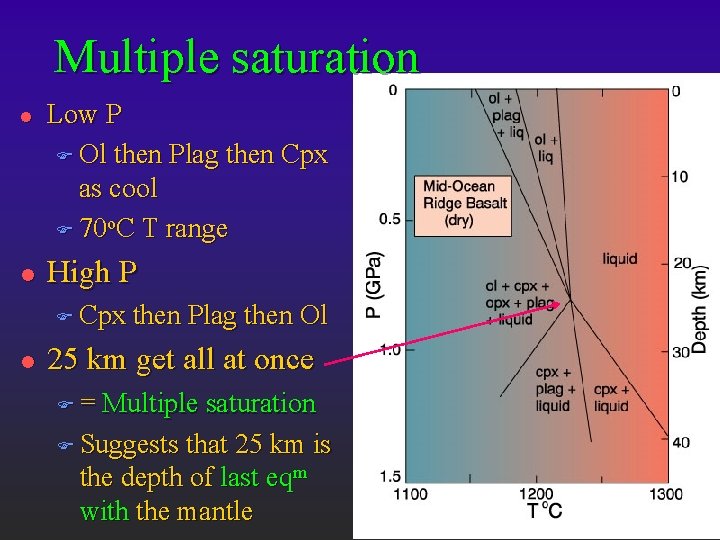

Multiple saturation l Low P F Ol then Plag then Cpx as cool F ~70 o. C T range Figure 10 -12 Anhydrous P-T phase relationships for a mid-ocean ridge basalt suspected of being a primary magma. After Fujii and Kushiro (1977). Carnegie Inst. Wash. Yearb. , 76, 461 -465.

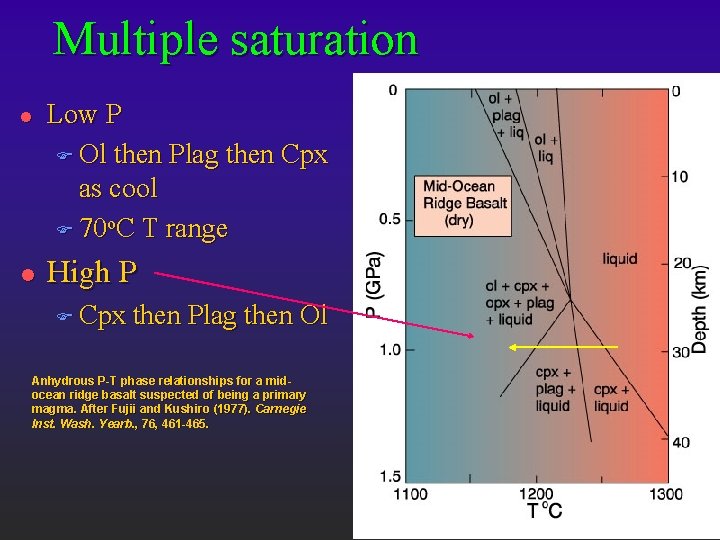

Multiple saturation l l Low P F Ol then Plag then Cpx as cool F 70 o. C T range High P F Cpx then Plag then Ol Anhydrous P-T phase relationships for a midocean ridge basalt suspected of being a primary magma. After Fujii and Kushiro (1977). Carnegie Inst. Wash. Yearb. , 76, 461 -465.

Multiple saturation l l Low P F Ol then Plag then Cpx as cool F 70 o. C T range High P F Cpx l then Plag then Ol 25 km get all at once F= Multiple saturation F Suggests that 25 km is the depth of last eqm with the mantle

Summary l l A chemically homogeneous mantle can yield a variety of basalt types Alkaline basalts are favored over tholeiites by deeper melting and by low % PM Fractionation at moderate to high depths can also create alkaline basalts from tholeiites At low P there is a thermal divide that separates the two series

Review of REE sample/chondrite 10. 00 8. 00 6. 00 4. 00 2. 00 0. 00 La Ce Nd Sm Eu Tb Er atomic number increasing incompatibility Yb Lu

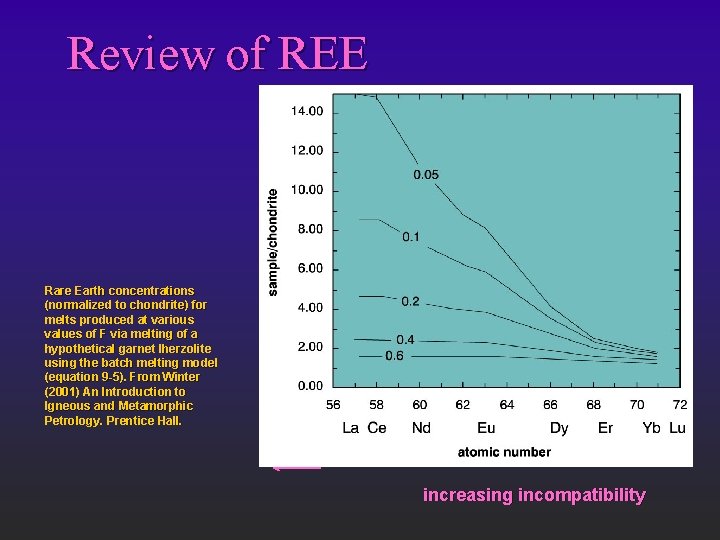

Review of REE Rare Earth concentrations (normalized to chondrite) for melts produced at various values of F via melting of a hypothetical garnet lherzolite using the batch melting model (equation 9 -5). From Winter (2001) An Introduction to Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology. Prentice Hall. increasing incompatibility

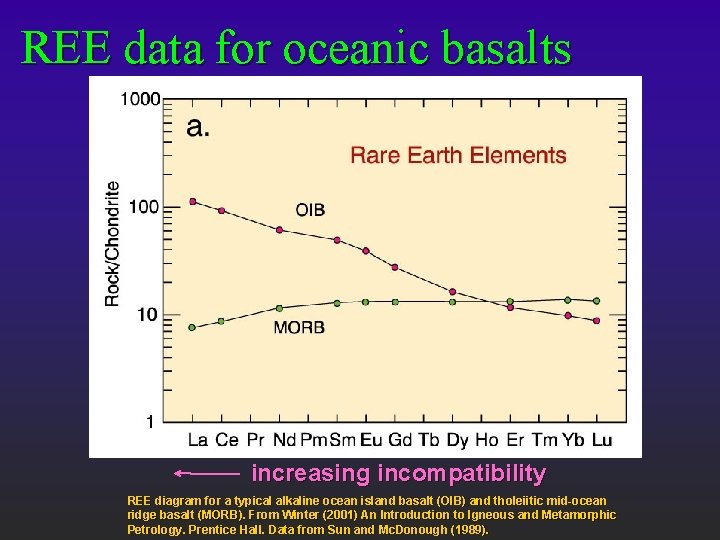

REE data for oceanic basalts increasing incompatibility REE diagram for a typical alkaline ocean island basalt (OIB) and tholeiitic mid-ocean ridge basalt (MORB). From Winter (2001) An Introduction to Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology. Prentice Hall. Data from Sun and Mc. Donough (1989).

Spider diagram for oceanic basalts increasing incompatibility Spider diagram for a typical alkaline ocean island basalt (OIB) and tholeiitic mid-ocean ridge basalt (MORB). From Winter (2001) An Introduction to Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology. Prentice Hall. Data from Sun and Mc. Donough (1989).

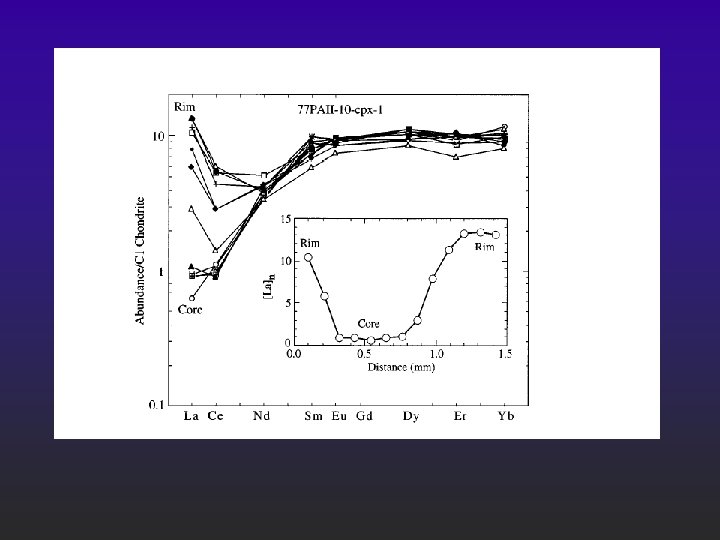

LREE depleted or unfractionated LREE enriched REE data for UM xenoliths LREE depleted or unfractionated Chondrite-normalized REE diagrams for spinel (a) and garnet (b) lherzolites. After Basaltic Volcanism Study Project (1981). Lunar and Planetary Institute. LREE enriched

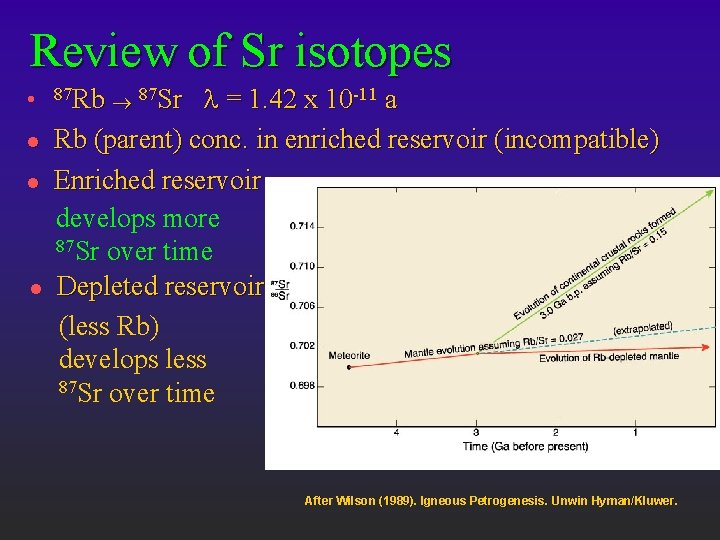

Review of Sr isotopes l l l = 1. 42 x 10 -11 a Rb (parent) conc. in enriched reservoir (incompatible) Enriched reservoir develops more 87 Sr over time Depleted reservoir (less Rb) develops less 87 Sr over time 87 Rb ® 87 Sr After Wilson (1989). Igneous Petrogenesis. Unwin Hyman/Kluwer.

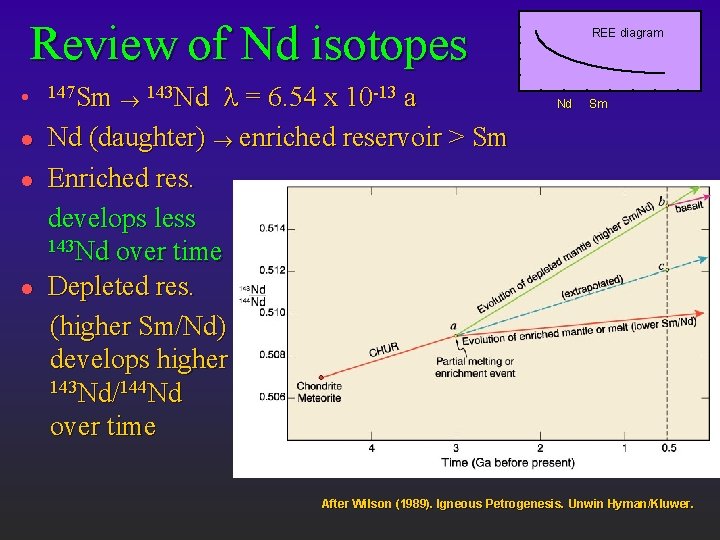

Review of Nd isotopes l l l = 6. 54 x 10 -13 a Nd (daughter) ® enriched reservoir > Sm Enriched res. develops less 143 Nd over time Depleted res. (higher Sm/Nd) develops higher 143 Nd/144 Nd over time 147 Sm ® 143 Nd REE diagram Nd Sm After Wilson (1989). Igneous Petrogenesis. Unwin Hyman/Kluwer.

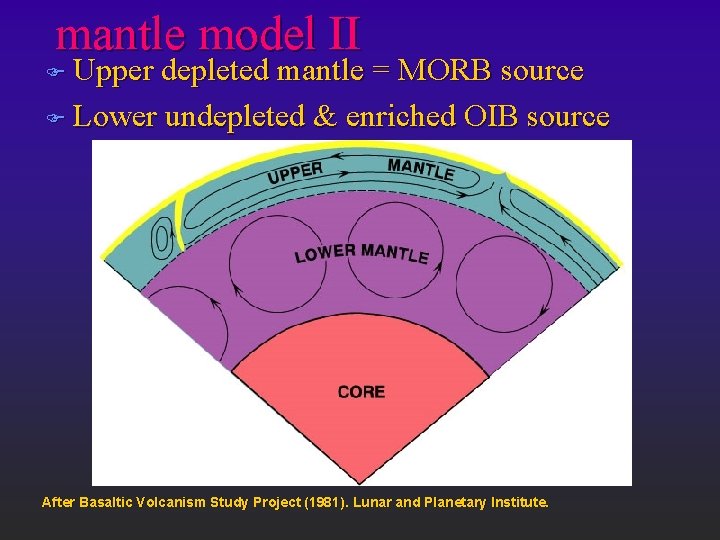

mantle model II F Upper depleted mantle = MORB source F Lower undepleted & enriched OIB source After Basaltic Volcanism Study Project (1981). Lunar and Planetary Institute.

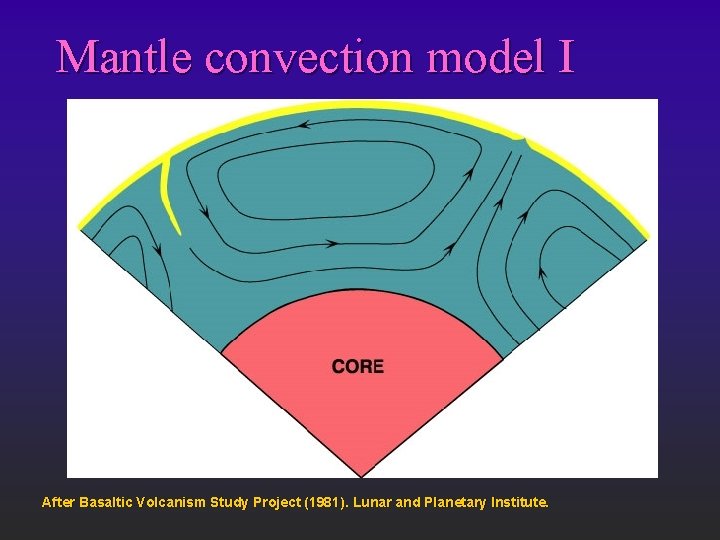

Mantle convection model I After Basaltic Volcanism Study Project (1981). Lunar and Planetary Institute.

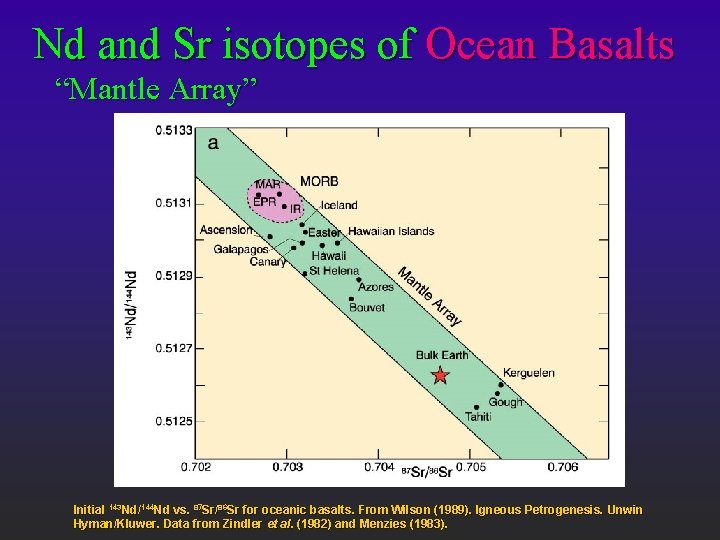

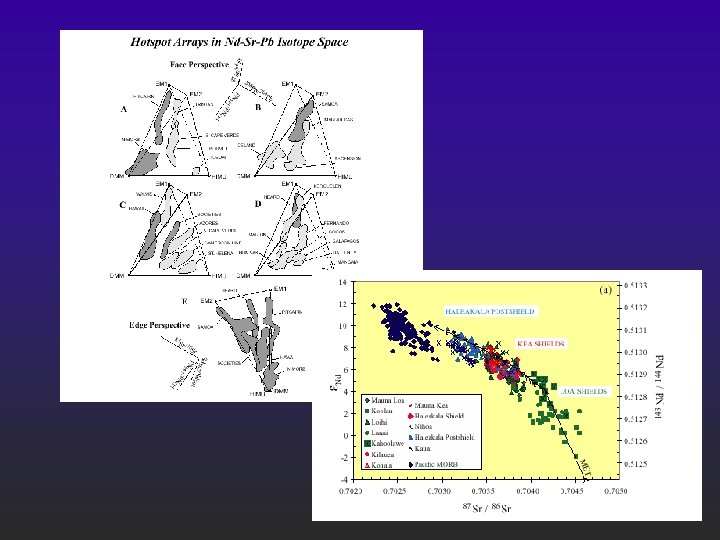

Nd and Sr isotopes of Ocean Basalts “Mantle Array” Initial 143 Nd/144 Nd vs. 87 Sr/86 Sr for oceanic basalts. From Wilson (1989). Igneous Petrogenesis. Unwin Hyman/Kluwer. Data from Zindler et al. (1982) and Menzies (1983).

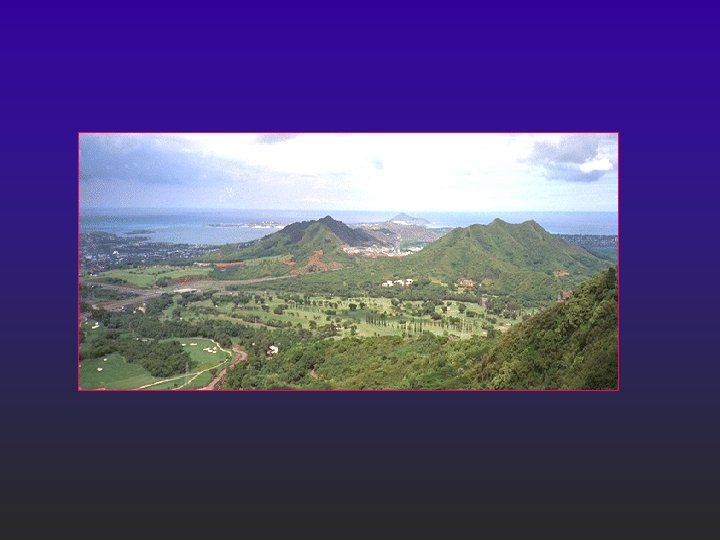

OAHU Pali

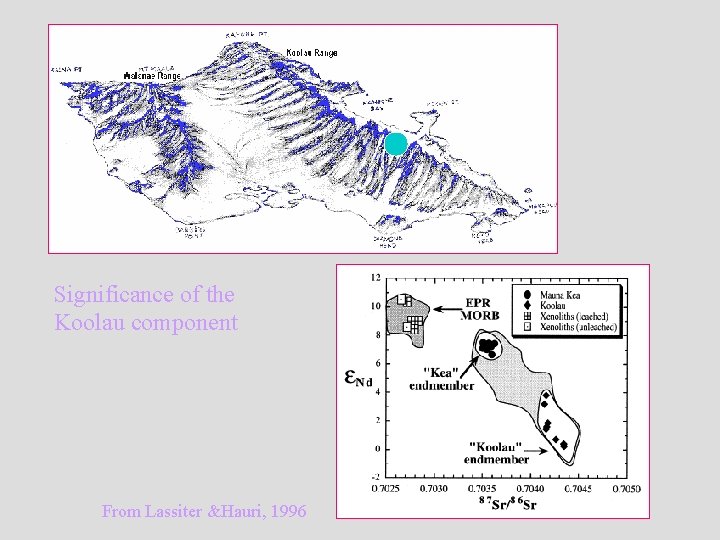

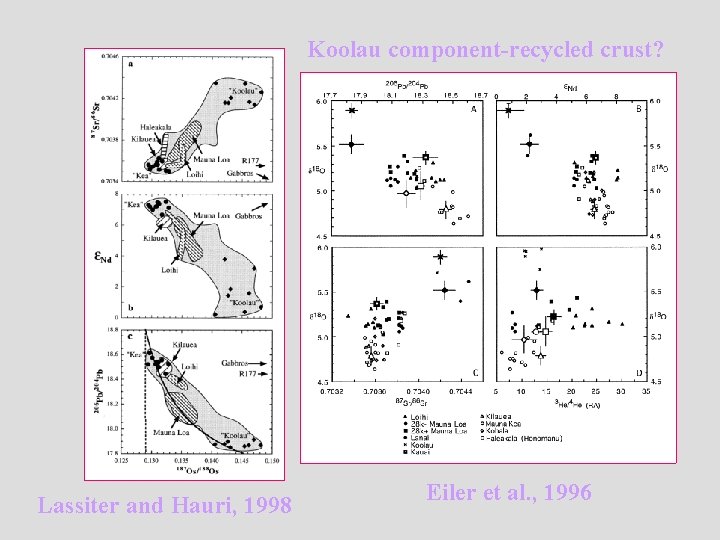

Significance of the Koolau component From Lassiter &Hauri, 1996

Koolau component-recycled crust? Lassiter and Hauri, 1998 Eiler et al. , 1996

2 mm (a, b, c), 1 mm (d) Plg-lherzolite-a, b, c, Sp lherzolite-d a c Take a look at hand specimen too! b d

Sr-Nd isotopes @Pali, Salt Lake Crater & Koolau

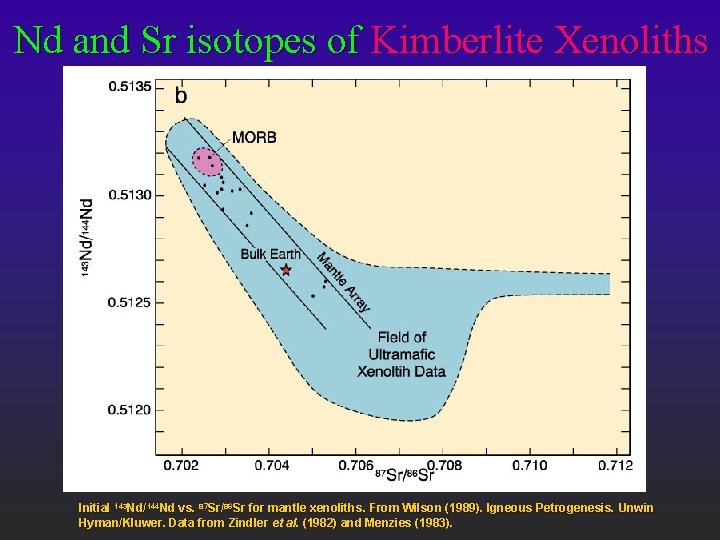

Nd and Sr isotopes of Kimberlite Xenoliths Initial 143 Nd/144 Nd vs. 87 Sr/86 Sr for mantle xenoliths. From Wilson (1989). Igneous Petrogenesis. Unwin Hyman/Kluwer. Data from Zindler et al. (1982) and Menzies (1983).

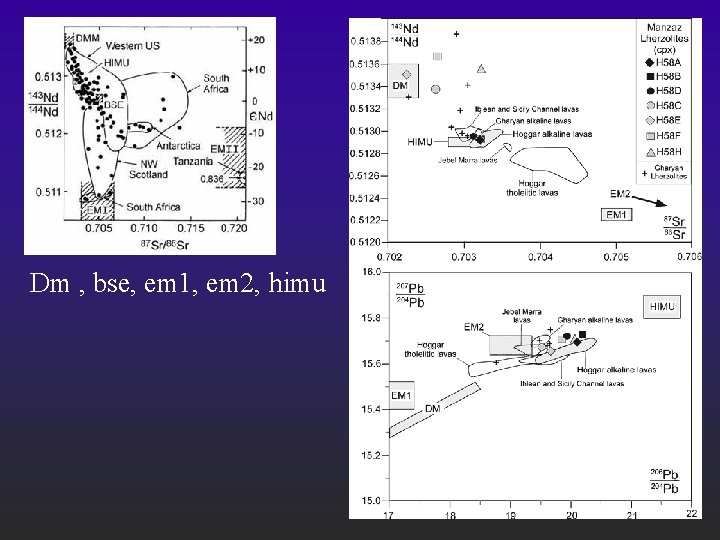

Dm , bse, em 1, em 2, himu

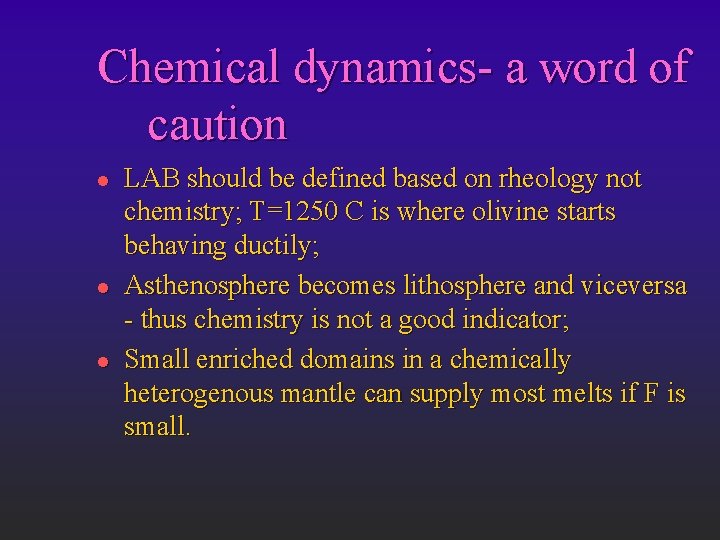

Chemical dynamics- a word of caution l l l LAB should be defined based on rheology not chemistry; T=1250 C is where olivine starts behaving ductily; Asthenosphere becomes lithosphere and viceversa - thus chemistry is not a good indicator; Small enriched domains in a chemically heterogenous mantle can supply most melts if F is small.

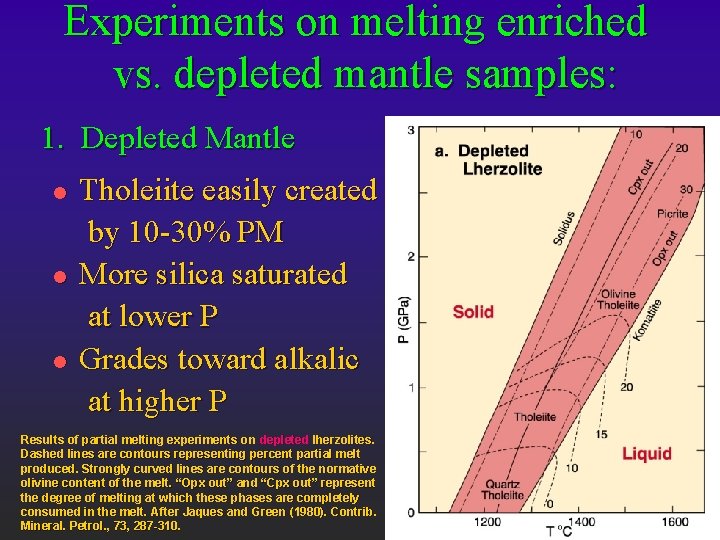

Experiments on melting enriched vs. depleted mantle samples: 1. Depleted Mantle l l l Tholeiite easily created by 10 -30% PM More silica saturated at lower P Grades toward alkalic at higher P Results of partial melting experiments on depleted lherzolites. Dashed lines are contours representing percent partial melt produced. Strongly curved lines are contours of the normative olivine content of the melt. “Opx out” and “Cpx out” represent the degree of melting at which these phases are completely consumed in the melt. After Jaques and Green (1980). Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. , 73, 287 -310.

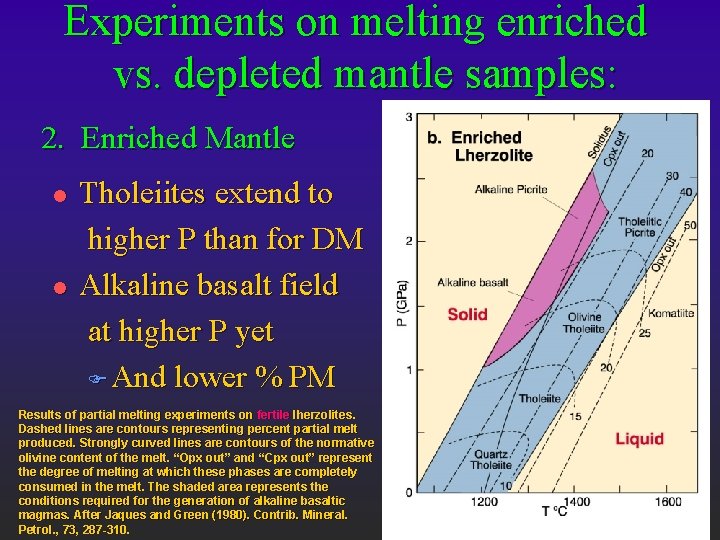

Experiments on melting enriched vs. depleted mantle samples: 2. Enriched Mantle l l Tholeiites extend to higher P than for DM Alkaline basalt field at higher P yet F And lower % PM Results of partial melting experiments on fertile lherzolites. Dashed lines are contours representing percent partial melt produced. Strongly curved lines are contours of the normative olivine content of the melt. “Opx out” and “Cpx out” represent the degree of melting at which these phases are completely consumed in the melt. The shaded area represents the conditions required for the generation of alkaline basaltic magmas. After Jaques and Green (1980). Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. , 73, 287 -310.

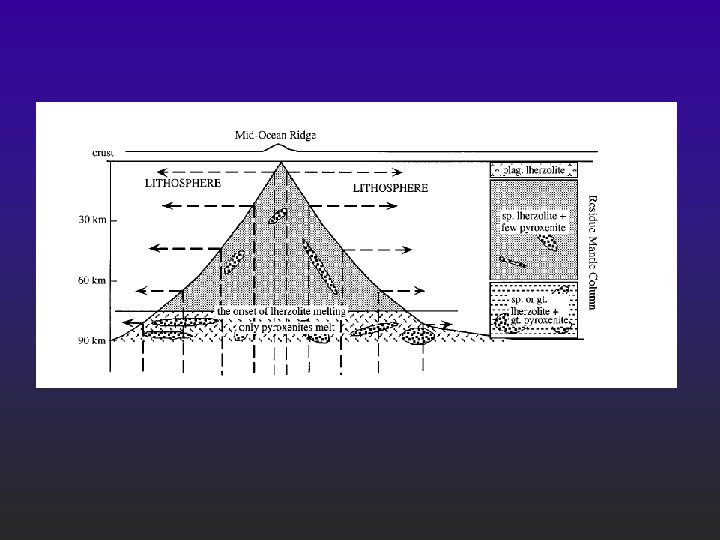

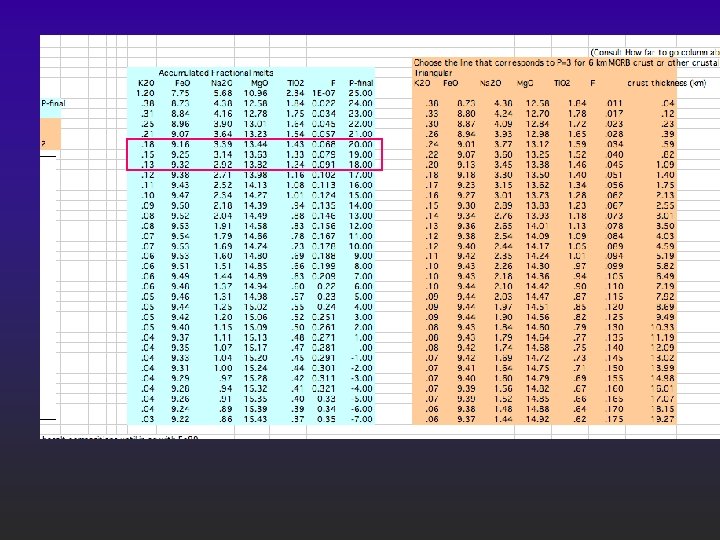

Need to parametrize melting l l l l Will do this for dry melting only; Aim to explain major elements; Assume adiabatic melting; Need a melting function; Need a start depth and an end depth; Assume that Si. O 2 does not change much; Use fractionall melting in increments of 1 kbar

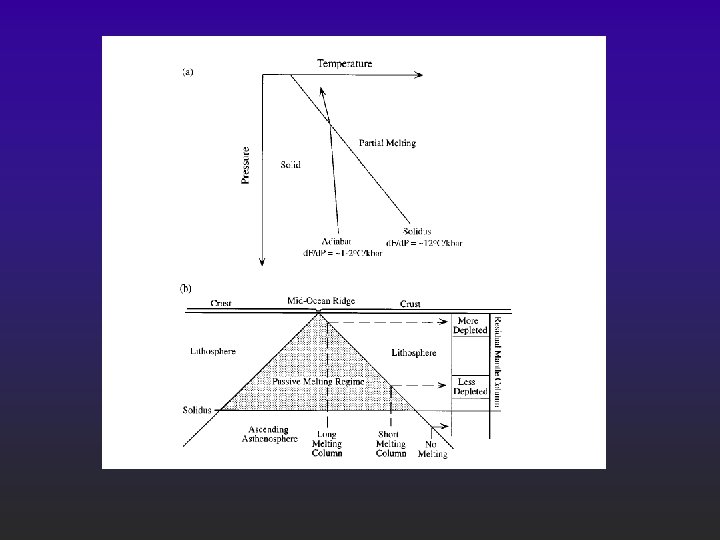

Parametrization l l Melting is linear as a function of depth; Source is only peridotite; Shape of melting domain is triangular; no extra wings to scavenge traces; Based on Mc. Kenzie and Bickle (1988); Langmuir et al. (1992) and Wang et al. (2002).

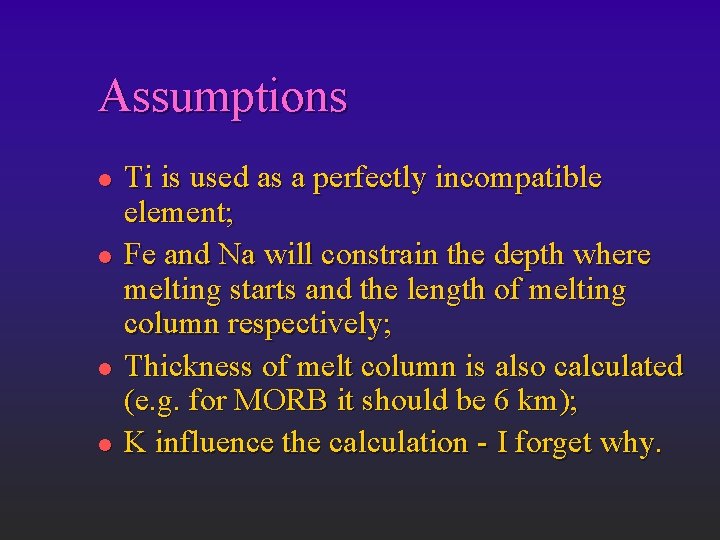

Assumptions l l Ti is used as a perfectly incompatible element; Fe and Na will constrain the depth where melting starts and the length of melting column respectively; Thickness of melt column is also calculated (e. g. for MORB it should be 6 km); K influence the calculation - I forget why.

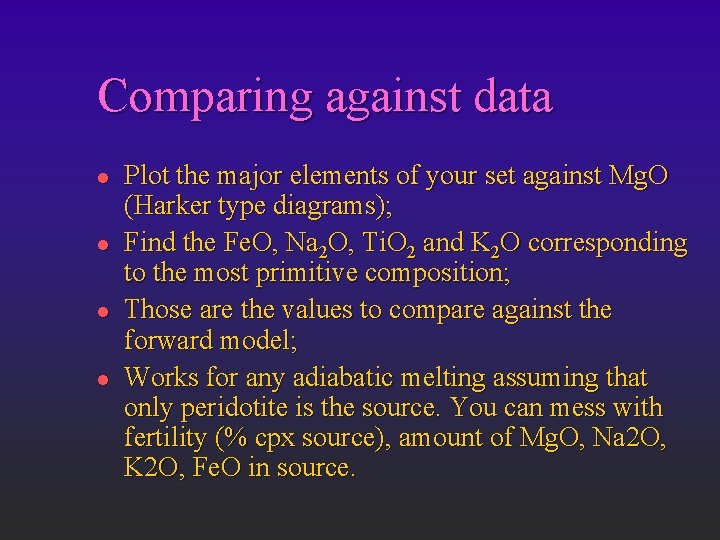

Comparing against data l l Plot the major elements of your set against Mg. O (Harker type diagrams); Find the Fe. O, Na 2 O, Ti. O 2 and K 2 O corresponding to the most primitive composition; Those are the values to compare against the forward model; Works for any adiabatic melting assuming that only peridotite is the source. You can mess with fertility (% cpx source), amount of Mg. O, Na 2 O, K 2 O, Fe. O in source.

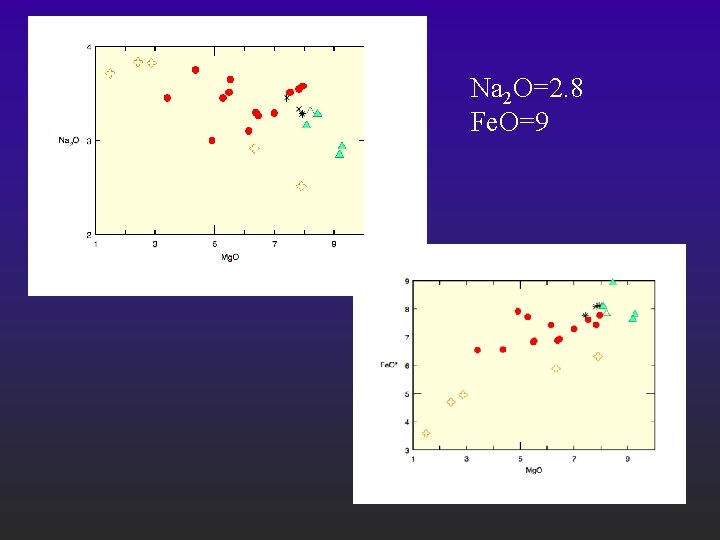

Na 2 O=2. 8 Fe. O=9

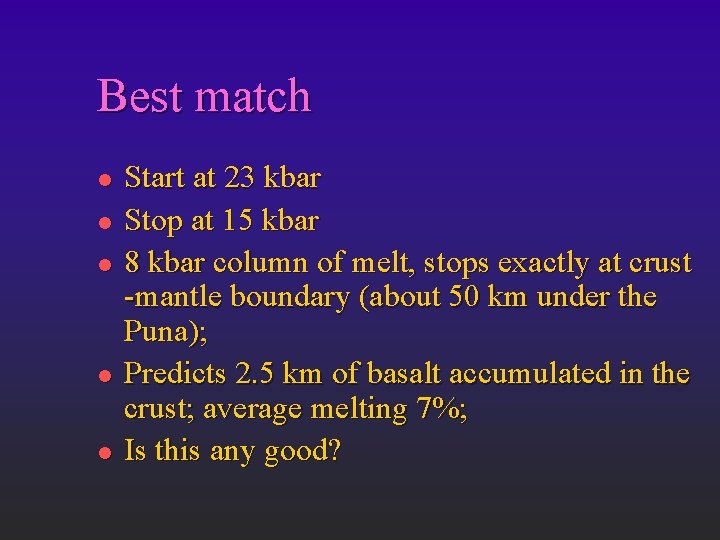

Best match l l l Start at 23 kbar Stop at 15 kbar 8 kbar column of melt, stops exactly at crust -mantle boundary (about 50 km under the Puna); Predicts 2. 5 km of basalt accumulated in the crust; average melting 7%; Is this any good?

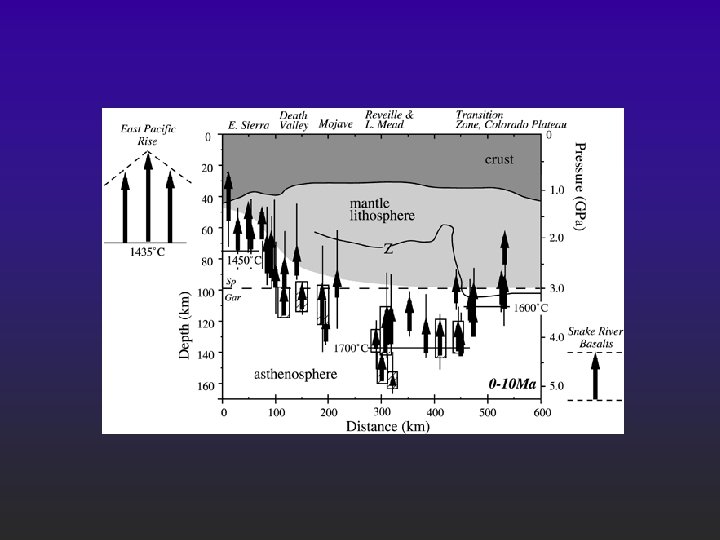

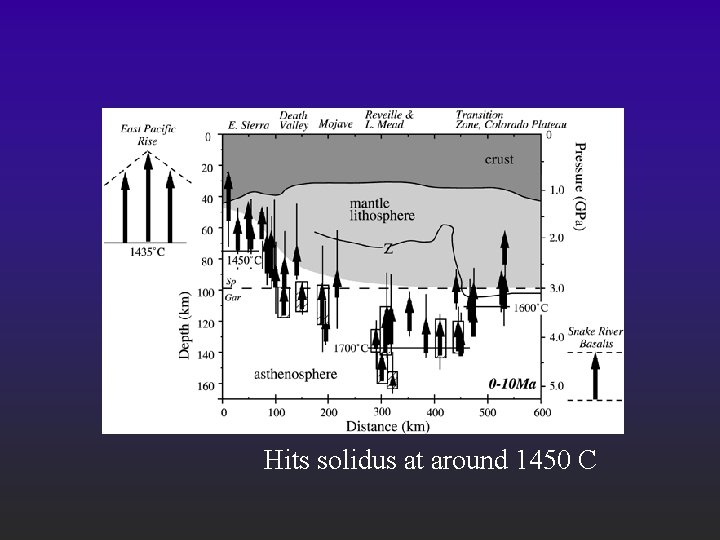

Hits solidus at around 1450 C

Other constraints l l l Use ol-glass thermometer for magma temp; Get xenoliths to find out how depleted/fertile a peridotite from under the Puna is; Crustal and lithospheric thickness constraints from seismo people;

HW 8 l l Use Blondes et al major element data for the Papoose flows only to determine the Fe. O and Na 2 O corresponding to the most primitive Mg. O; Use LPK model to determine the melt starting pressure, ending pressure, melt thickness and average F

- Slides: 73