DR DUAA HIASAT Case 1 A 35 yearold

![• antihypertensive medications (angiotensin- • • • converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers). • antihypertensive medications (angiotensin- • • • converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers).](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/00007df0b38184a114c1ff57b635c977/image-12.jpg)

- Slides: 57

DR. DUAA HIASAT

Case 1 A 35 -year-old nonsmoking man complains of heartburn relieved by belching. These symptoms occur daily. He also complains of an occasional nighttime sour taste in the mouth followed by an episode of coughing usually after a fatty meal and/or alcohol consumption. The symptoms began a few years ago. The patient denies a loss of appetite, dysphagia, or weight loss. He attributes the symptoms to gastroesophageal reflux and excessive coffee drinking. The patient occasionally taks antacids as needed and they relieve his symptoms. He asks you about the need for an upper endoscopy to investigate his symptoms further.

Case 2 A 44 -year-old man presents with a history of frequent epigastric pain for the past month that is burning in nature. He notes it is relieved after eating a meal or drinking milk. He has no change in his bowel movements and no melena or hematochezia. A friend gave him some esomeprazole tablets which helps when used. On examination, the patient has stable vital signs and is in no distress. At the time of your exam, he has no epigastric tenderness. His rectal exam shows heme-negative stool. He asks for a prescription of esomeprazole to relieved his symptoms.

Clinical questions: 1. What are the most common and important causes of dyspepsia? 2. What is the best strategy for the family physician to use in diagnosing the cause of a patient’s dyspepsia? 3. What are the most effective treatments for different causes of dyspepsia?

KEY POINTS Most patients with dyspepsia have no structural abnormality (nonulcer dyspepsia). Patients without alarm symptoms should be tested for Helicobacter pylori and, if test results are positive, treated with an appropriate antibiotic regimen. Patients with nonulcer dyspepsia may be treated with a proton pump inhibitor or histamine-2 blocking agent (H 2 blocker).

Essentials of Diagnosis Epigastric pain or burning, early satiety, or postprandial fullness. Endoscopy is warranted in patients with alarm features or in those older than 60 years. All other patients should first undergo testing for Helicobacter pylori or a trial of empiric proton pump inhibitor.

Definition Dyspepsia is characterized by epigastric discomfort or pain and can be associated with epigastric heaviness or fullness, belching or regurgitation, bloating, early satiety, heartburn, food intolerance, nausea, or vomiting. Lower bowel function is usually not affected.

Common causes Food or Drug Intolerance Acute, self-limited "indigestion" may be caused by overeating, eating too quickly, eating high-fat foods, eating during stressful situations, or drinking too much alcohol or coffee. Many medications cause dyspepsia, including: • aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). • antibiotics (metronidazole, macrolides). • diabetes drugs (metformin, α-glucosidase inhibitors, amylin analogs, GLP-1 receptor agonists).

![antihypertensive medications angiotensin converting enzyme ACE inhibitors angiotensinreceptor blockers • antihypertensive medications (angiotensin- • • • converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers).](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/00007df0b38184a114c1ff57b635c977/image-12.jpg)

• antihypertensive medications (angiotensin- • • • converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers). cholesterol-lowering agents (niacin, fibrates). neuropsychiatric medications (cholinesterase inhibitors [donepezil, rivastigmine]), SSRIs (fluoxetine, sertraline), serotoninnorepinephrine-reuptake inhibitors (venlafaxine, duloxetine), Parkinson's drugs (dopamine agonists, monoamine oxidase [MAO]-B inhibitors). corticosteroids, estrogens, digoxin, iron, and opioids.

Luminal Gastrointestinal Tract Dysfunction • Peptic ulcer disease is present in 5– 15% of patients • • • with dyspepsia. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is present in up to 20% of patients with dyspepsia, even without significant heartburn. Gastric cancer is identified in 1% but is extremely rare in persons under age 55 years with uncomplicated dyspepsia. Other causes include gastroparesis (especially in diabetes mellitus), lactose intolerance or malabsorptive conditions, and parasitic infection (Giardia, Strongyloides).

Helicobacter pylori Infection Although chronic gastric infection with H pylori is an important cause of peptic ulcer disease, it is an uncommon cause of dyspepsia in the absence of peptic ulcer disease. The prevalence of H pyloriassociated chronic gastritis in patients with dyspepsia without peptic ulcer disease is 20– 50%, the same as in the general population.

Pancreatic Disease Pancreatic carcinoma and chronic pancreatitis may present with dyspepsia. Biliary Tract Disease The abrupt onset of epigastric or right upper quadrant pain due to cholelithiasis or choledocholithiasis should be readily distinguished from dyspepsia.

Other Conditions Ø Diabetes mellitus Ø thyroid disease Ø chronic kidney disease Ø myocardial ischemia Ø intra-abdominal malignancy Ø gastric volvulus or paraesophageal hernia Ø pregnancy are sometimes accompanied by dyspepsia. * Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, chronic pancreatitis, abdominal angina, and coronary artery disease are uncommon.

Symptoms A. Heartburn, and regurgitation are reliable symptoms of reflux. B. Alarm symptoms. The presence of alarm symptoms including age older than 60 zzzc xmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmb years, significant weight loss, persistent vomiting, melena, hematemesis, or dysphagia should prompt immediate work-up, usually with endoscopy. C. Symptoms that poorly discriminate between specific disease and NUD. These include relief with antacids or food, nocturnal pain, food intolerance (eg, fatty food intolerance), duration of pain, pain that occurs within 1 hour of eating,

D. Symptoms that may identify patients with complications of PUD. Symptoms that indicate complications of PUD or other specific causes of dyspepsia are: • Hematemesis, melena, or both indicate gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. • Dizziness, especially upon sitting or standing, or syncope may indicate significant blood loss. • Persistent vomiting is a symptom of gastric outlet obstruction.

• Pain that radiates straight through to the back may indicate a perforated ulcer, leaking abdominal aneurysm, pancreatitis, or pancreatic cancer. • Pain radiating to the shoulder may result from diaphragmatic irritation due to pus, blood, or free air.

Signs In general, the physical examination is not helpful in determining the cause of dyspepsia. In uncomplicated cases, the examination usually reveals only mild to moderate epigastric tenderness. The following signs may be helpful in identifying patients with complications of PUD or serious systemic illness.

Unexplained tachycardia (pulse >120) or postural hypotension (orthostatic change in blood pressure >20 mm Hg) may indicate significant blood loss from GI bleeding. Abdominal rebound or rigidity suggests peritoneal irritation. A perforated viscus, blood, or infection cause peritoneal irritation. Blood in the stool may indicate upper GI tract bleeding. Jaundice may indicate biliary tract obstruction from pancreatic cancer or cholelithiasis.

Laboratory Tests A. Tests that may be useful include: 1 -Tests for H pylori. These can be either noninvasive (serology, or urea breath test) or invasive (rapid urease test, obtained at the time of upper endoscopy). Serology is the easiest and least costly. 2 -Upper GI series. The upper GI series is noninvasive and relatively inexpensive. The false-negative rate of this technique exceeds 18% the false-positive rate is between 13% and 35%. Even with double-contrast studies, the falsenegative rate is still between 9% and 17%, and the falsepositive rate is approximately 10%.

v In a patient with GERD, only severe esophagitis may be detected, although reflux and motility disorders of the esophagus can be seen. The presence of a hiatal hernia does not correlate with GERD. 3 -Upper endoscopy. Upper endoscopy is a relatively safe procedure, with a complication rate of 1. 32 or less per 1000 cases. Over half of the complications (eg, hives and thrombophlebitis) Upper endoscopy is preferred to upper GI barium study because lesions can be directly visualized and biopsy can be performed. In addition, testing for H pylori can be performed.

4 -Intraesophageal p. H monitoring. Most physicians consider this procedure to be the single best test for diagnosis for GERD. Coupled with a symptom diary, 24 -hour monitoring has a sensitivity between 87% and 93% and a specificity of 92 -97% for GERD. 5 -Scintigraphy. Scintigraphy is best used to detect delayed gastric emptying. GERD and delayed gastric emptying can be detected using [99 m. Tc] sulfur colloid, although intraesophageal p. H monitoring is a better test for reflux.

B. Indications for further testing: A diagnostic investigation should be started promptly in patients with clinically obvious conditions, such as severe systemic illness, bleeding, perforation, symptoms of upper GI tract obstruction, or evidence of cancer. Persistence of symptoms after empiric treatment in patients previously not evaluated with endoscopy or upper GI series requires further evaluation. In patients who experience a recurrence of dyspepsia and who have previously been treated empirically for the condition, a specific diagnosis should be made.

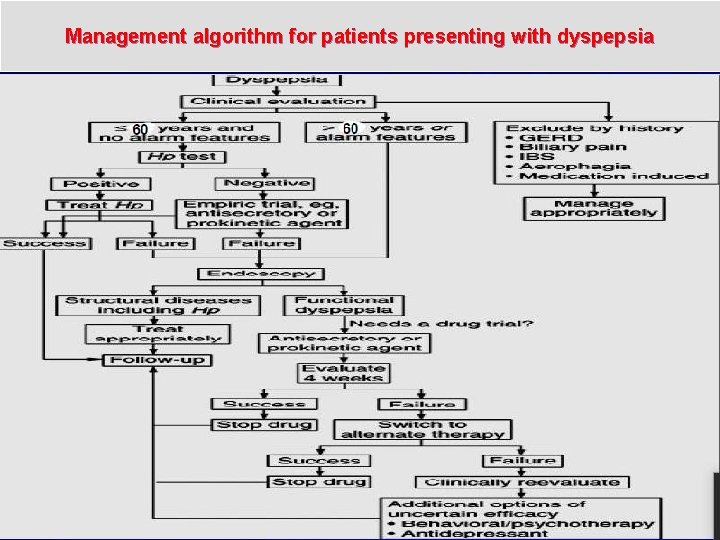

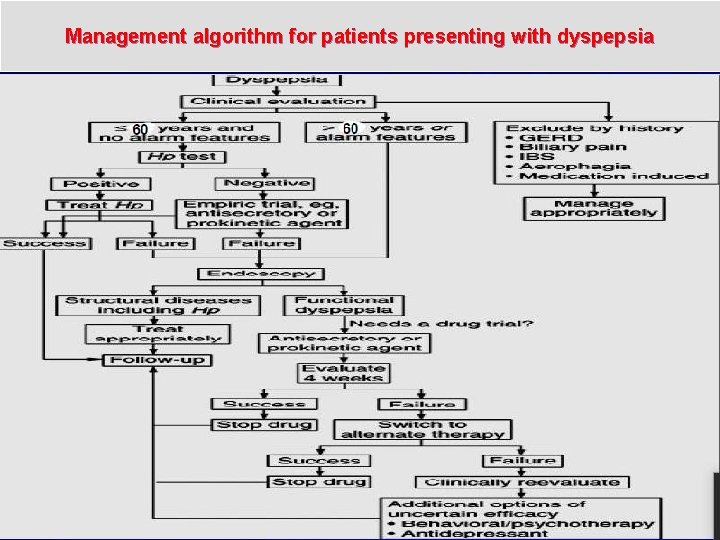

Management algorithm for patients presenting with dyspepsia

Treatment Initial empiric treatment is warranted for patients who are less than 60 years and who have no alarm features (defined above). All other patients as well as patients whose symptoms fail to respond or relapse after empiric treatment should undergo upper endoscopy with subsequent treatment directed at the specific disorder (eg, peptic ulcer, gastroesophageal reflux, cancer). Most patients will have no significant findings on endoscopy and will be given a diagnosis of functional dyspepsia.

Empiric Therapy ü H pylori–negative patients most likely have functional dyspepsia or atypical GERD and can be treated with an antisecretory agent (proton pump inhibitor) for 4 weeks. For patients who have symptom relapse after discontinuation of the proton pump inhibitor, intermittent or long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy may be considered.

Patients ≥ 60 years of age with dyspepsia should undergo an upper endoscopy. Most patients with a normal upper endoscopy and routine laboratory tests have functional dyspepsia. However, additional evaluation may be required based on symptoms (eg, abdominal imaging with an ultrasound or computed tomography scan in patients with concurrent jaundice or pain suggestive of a biliary/pancreatic source).

In patients <60 years indications for upper endoscopy include: -Clinically significant weight loss (>5 percent usual body weight over 6 to 12 months) -Overt gastrointestinal bleeding ->1 alarm feature (table 2) -Rapidly progressive alarm features

• Patients <60 years of age should be tested and treated for H. pylori. Patients who test positive for an infection with H. pylori should undergo treatment with eradication therapy.

In patients who test negative for H. pyloriand for those with persistent symptoms after H. pylori eradication, we suggest treatment with antisecretory therapy with a proton pump inhibitor four to eight weeks (table 3) (Grade 2 A). ●Patients with continued symptoms of dyspepsia despite a trial of a tricyclic antidepressant and prokinetic, should undergo endoscopic evaluation with an

ü For patients in whom test results are positive for H pylori, antibiotic therapy proves definitive for over 90% of peptic ulcers and may improve symptoms in a small subset (< 10%) of infected patients with functional dyspepsia. Patients with persistent dyspepsia after H pylori eradication can be given a trial of proton pump inhibitor therapy. In clinical settings in which the prevalence of H pylori infection in the population is low (< 10%), it may be more cost-effective to initially treat all young patients with uncomplicated dyspepsia with a 4 -week trial of a proton pump inhibitor. Patients who have symptom relapse after discontinuation of the proton pump inhibitor should be tested for H pylori and treated if positive.

In patients who test negative for H. pyloriand for those with persistent symptoms after H. pylori eradication, we suggest treatment with antisecretory therapy with a proton pump inhibitor four to eight weeks (table 3) (Grade 2 A).

Patients with continued symptoms of dyspepsia despite a trial of a tricyclic antidepressant and prokinetic, should undergo endoscopic evaluation with an upper endoscopy and biopsies, if not previously performed (algorithm 1). Further evaluation for an alternate diagnosis should be performed selectively based on the patient’s symptoms

. Patients with continued symptoms of dyspepsia for three months with symptom onset at least six months before diagnosis and no evidence of structural disease to explain the symptoms should be diagnosed and treated as functional dyspepsia.

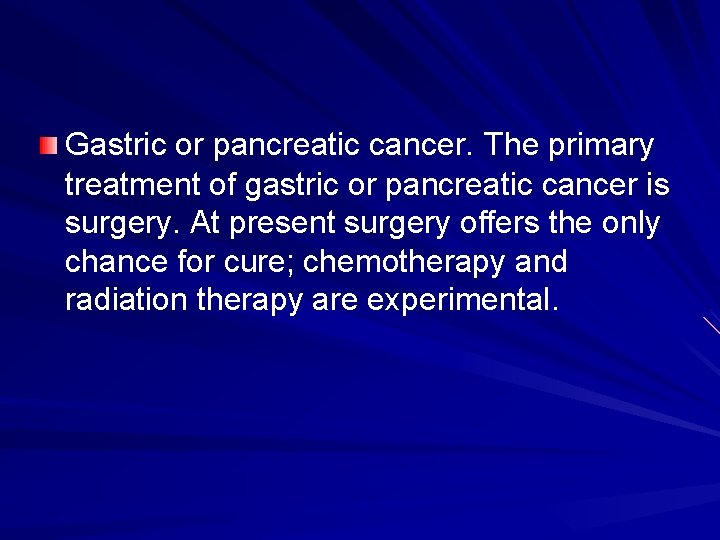

Gastric or pancreatic cancer. The primary treatment of gastric or pancreatic cancer is surgery. At present surgery offers the only chance for cure; chemotherapy and radiation therapy are experimental.

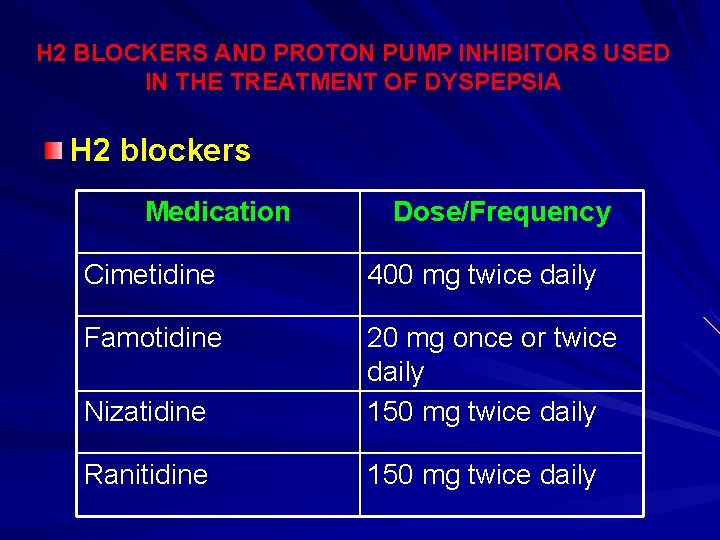

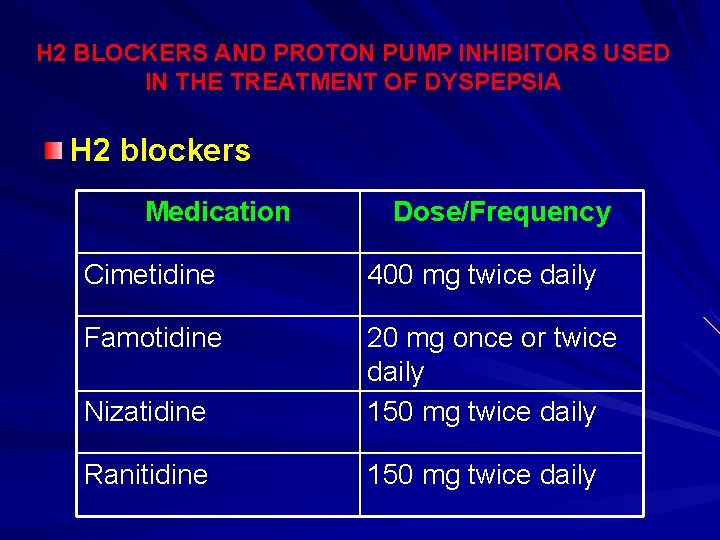

H 2 BLOCKERS AND PROTON PUMP INHIBITORS USED IN THE TREATMENT OF DYSPEPSIA H 2 blockers Medication Dose/Frequency Cimetidine 400 mg twice daily Famotidine Nizatidine 20 mg once or twice daily 150 mg twice daily Ranitidine 150 mg twice daily

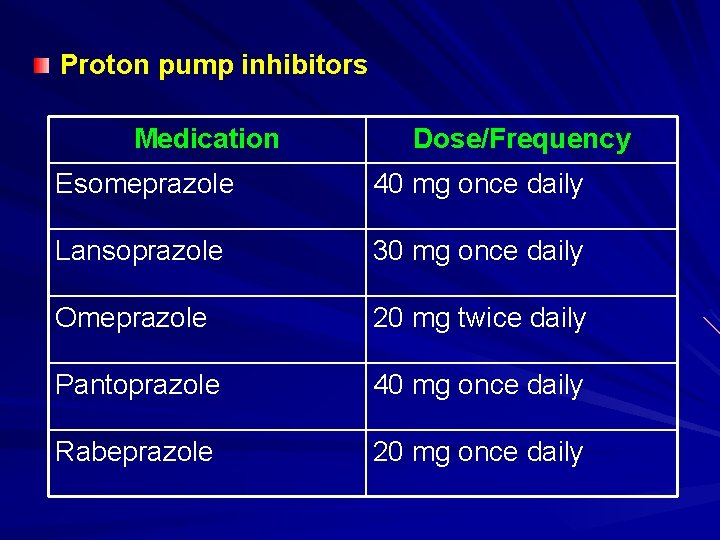

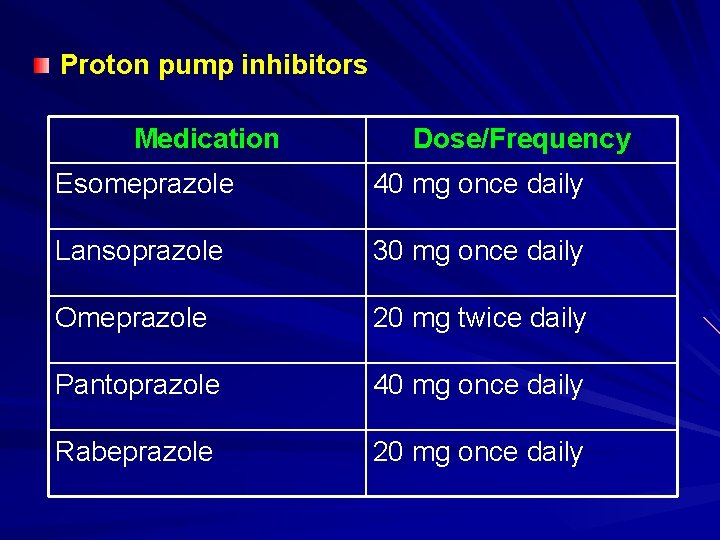

Proton pump inhibitors Medication Dose/Frequency Esomeprazole 40 mg once daily Lansoprazole 30 mg once daily Omeprazole 20 mg twice daily Pantoprazole 40 mg once daily Rabeprazole 20 mg once daily

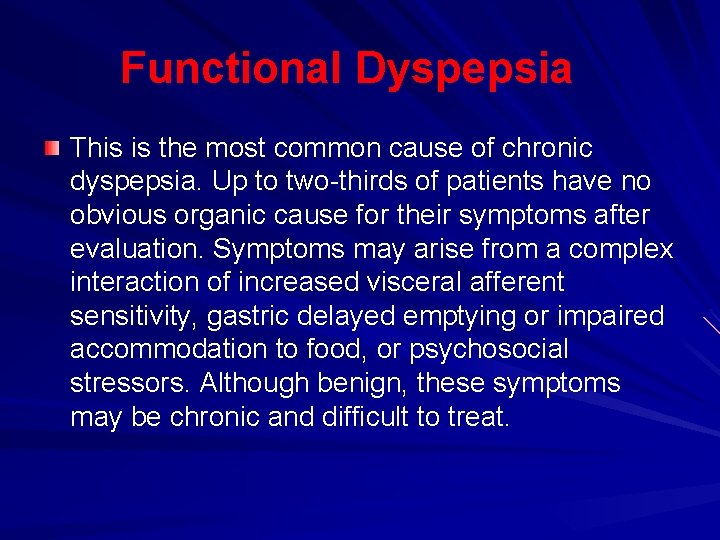

Functional Dyspepsia This is the most common cause of chronic dyspepsia. Up to two-thirds of patients have no obvious organic cause for their symptoms after evaluation. Symptoms may arise from a complex interaction of increased visceral afferent sensitivity, gastric delayed emptying or impaired accommodation to food, or psychosocial stressors. Although benign, these symptoms may be chronic and difficult to treat.

Treatment of Functional Dyspepsia General Measures Most patients have mild, intermittent symptoms that respond to reassurance and lifestyle changes. Alcohol, caffeine, and fatty foods should be reduced or discontinued. A food diary, in which patients record their food intake, symptoms, and daily events, may reveal dietary or psychosocial precipitants of pain.

Pharmacologic Agents • Drugs have demonstrated limited efficacy in the treatment of functional dyspepsia. One-third of patients derive relief from placebo. • Antisecretory therapy for 4– 8 weeks with proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole, esomeprazole, or rabeprazole 20 mg, lansoprazole 30 mg, or pantoprazole 40 mg) may benefit 10– 15% of patients, particularly those with dyspepsia characterized as epigastric pain ("ulcer-like dyspepsia") or dyspepsia and heartburn ("reflux-like dyspepsia").

• Low doses of antidepressants (eg, desipramine or nortriptyline, 10– 50 mg at bedtime) are believed to benefit some patients, possibly by moderating visceral afferent sensitivity. However, side effects are common and response is patient -specific. Doses should be increased slowly. • The prokinetic agent metoclopramide (5– 10 mg three times daily) may improve symptoms, but improvement does not correlate with the presence or absence of gastric emptying delay.

v In 2009, the FDA issued a black box warning that metoclopramide use for more than 3 months is associated with a high incidence of tardive dyskinesia and should be avoided. The elderly, particularly elderly women, are most at risk. Recently, a randomized, placebo-controlled study has demonstrated efficacy of the novel prokinetic agent itopride in the treatment of functional dyspepsia. This agent enhances the release of gastric acetylcholine through dual inhibition of D 2 receptors and acetylcholinesterase. This agent is not yet available in the United States.

Anti-H pylori Treatment Meta-analyses have suggested that a small number of patients with functional dyspepsia (< 10%) derive benefit from H pylori eradication therapy. Therefore, patients with functional dyspepsia should be tested and treated for H pylori. Alternative Therapies Psychotherapy and hypnotherapy may be of benefit in selected motivated patients with functional dyspepsia. Herbal therapies (peppermint, caraway) may offer benefit with little risk of adverse effects.

PEDIATRIC GERD Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is fairly common in infants. It is marked by regurgitation with normal weight gain. The peak incidence is at 14 months and is usually resolved by age 1. Can be treated conservatively by reassuring parents and using thickened feedings, hypoallergenic formula, and upright positioning after feedings. Although the supine position leads to less reflux, it is not recommended because of the increased incidence of sudden infant death syndrome in this position.

Infants who present with regurgitation and alarm symptoms such as respiratory problems (stridor, wheezing, cough), poor weight gain or growth, or irritability require further evaluation. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) should be considered in the differential diagnosis of these children. In older children and adolescents, GERD usually presents with heartburn, or lower chest pain.

Infants or children with esophageal atresia with repair, neurologic impairment/delay, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, asthma, or cystic fibrosis have an increased risk of GERD. A pediatric gastroenterologist can help guide the work-up of GERD. Medical management includes H 2 blockers and proton pump inhibitors. Prokinetic agents may have a role.

Case 2 discussion The patient’s symptoms suggest that he may have a duodenal ulcer. The patient has no alarm symptoms, so one can proceed with the test and treat for H. pylori strategy. The patient should be offered an H. pylori urea breath test or stool antigen test. If the results are positive, he should then be offered H. pylori eradication therapy with a triple regimen of medications: PPI, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin. if his H. pylori test is negative, he can then be offered a PPI alone.