Dr Christopher Morrow UAE University cmorrowuaeu ac ae

- Slides: 28

Dr. Christopher Morrow UAE University cmorrow@uaeu. ac. ae iteach. co. nr How Important is English in Elementary School?

Early English is increasingly seen as a vehicle of globalization AND early exposure is often seen as a key to success and a solution to all problems in language education BUT: it may be perceived as a threat to first language development and identity. DOES it corrupt young children’s minds and threaten their L 1 literacy and identity?

Benefits of Multilingualism in Europe A recent European language policy document states that it is a priority to ensure effective language learning in the kindergarten and primary school, as in such programs “attitudes towards other languages and cultures are formed, and the foundations for later language learning are laid” (Commission of the European Communities, 2003, p. 7).

Benefits of bilingualism Besides socioaffective and linguistic gains, research on early bilinguals (Bialystok, 2001, 2005) emphasizes that bilingualism is associated with more effective controlled processing in children, as the constant management of two competing languages enhances executive functions (Bialystok, Craik, Klein, & Viswanathan, 2004)

A Myriad of Connected Issues Social, political, economic, cognitive, and psychological factors can affect early language teaching and learning practices The specific costs and benefits of early English are often hard to isolate. Famous Theory = The Critical Period Hypothesis

Faulty research conclusions (Marinova. Todd, Marshall, & Snow, 2000) Researchers have often committed the same blunders as the general public: misinterpretation of the facts relating to speed of acquisition (underestimating time of exposure) misattribution of age differences in language abilities to neurobiological factors, underemphasis on adults who master L 2 s to nativelike levels.

Myths that die hard Earlier is better More time studying a language leads to more success Older students are slower and ultimately less successful Multilingualism confuses children

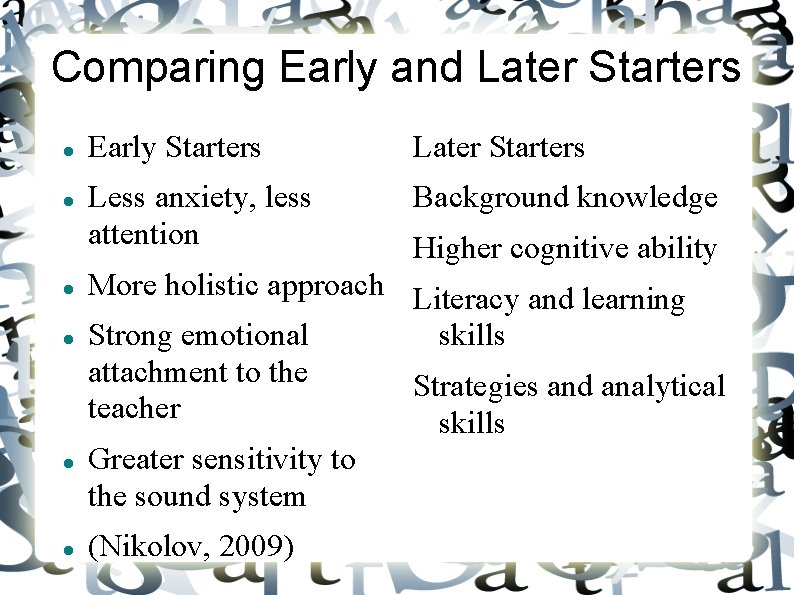

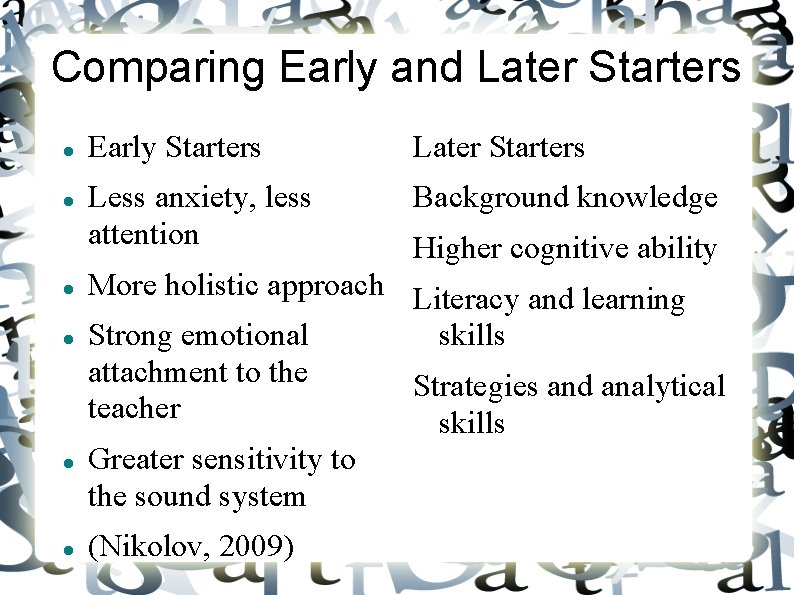

Comparing Early and Later Starters Early Starters Later Starters Less anxiety, less attention Background knowledge Higher cognitive ability More holistic approach Literacy and learning Strong emotional skills attachment to the Strategies and analytical teacher skills Greater sensitivity to the sound system (Nikolov, 2009)

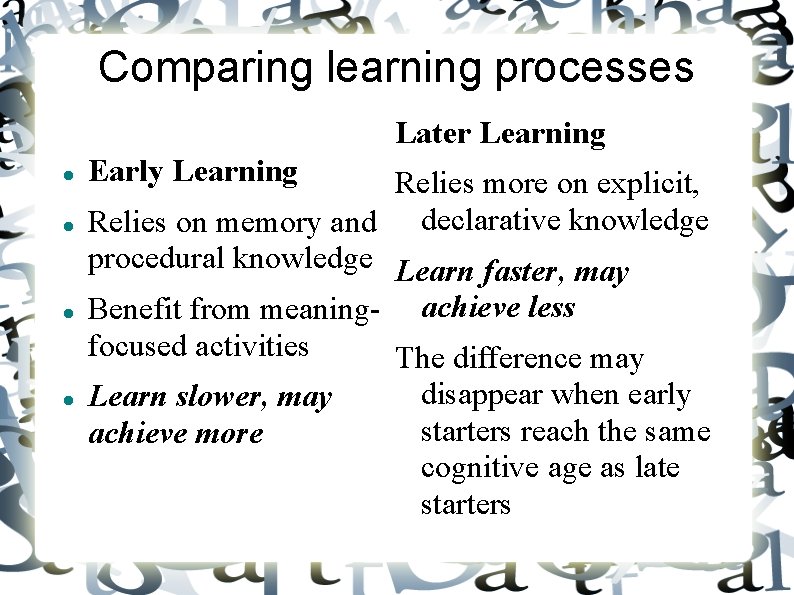

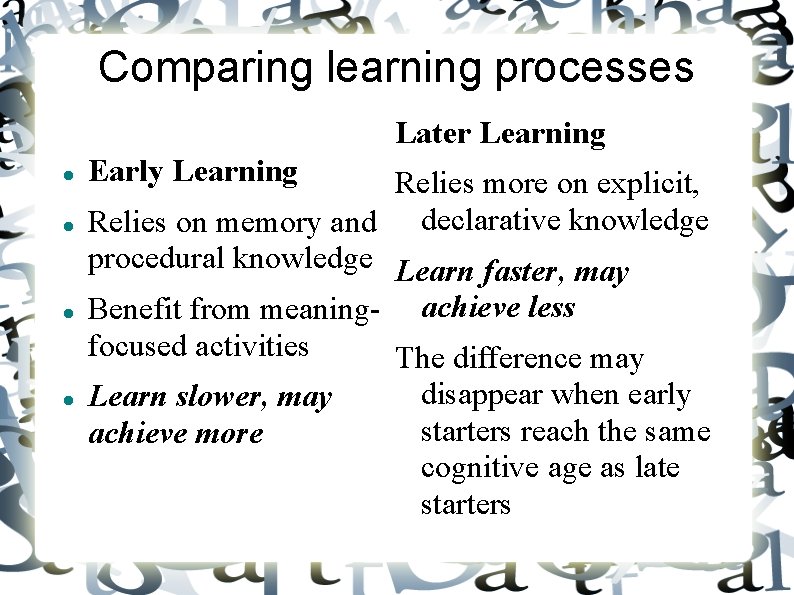

Comparing learning processes Later Learning Early Learning Relies more on explicit, Relies on memory and declarative knowledge procedural knowledge Learn faster, may Benefit from meaning- achieve less focused activities The difference may disappear when early Learn slower, may starters reach the same achieve more cognitive age as late starters

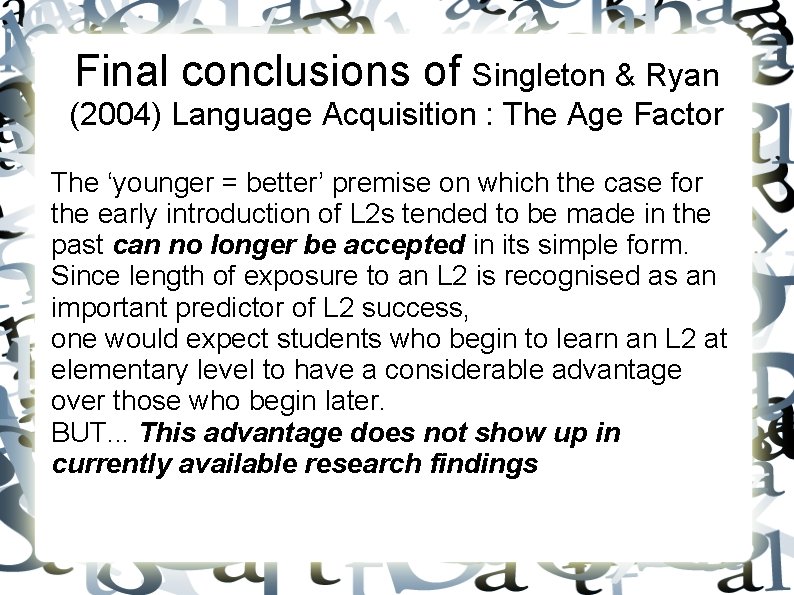

Final conclusions of Singleton & Ryan (2004) Language Acquisition : The Age Factor The ‘younger = better’ premise on which the case for the early introduction of L 2 s tended to be made in the past can no longer be accepted in its simple form. Since length of exposure to an L 2 is recognised as an important predictor of L 2 success, one would expect students who begin to learn an L 2 at elementary level to have a considerable advantage over those who begin later. BUT. . . This advantage does not show up in currently available research findings

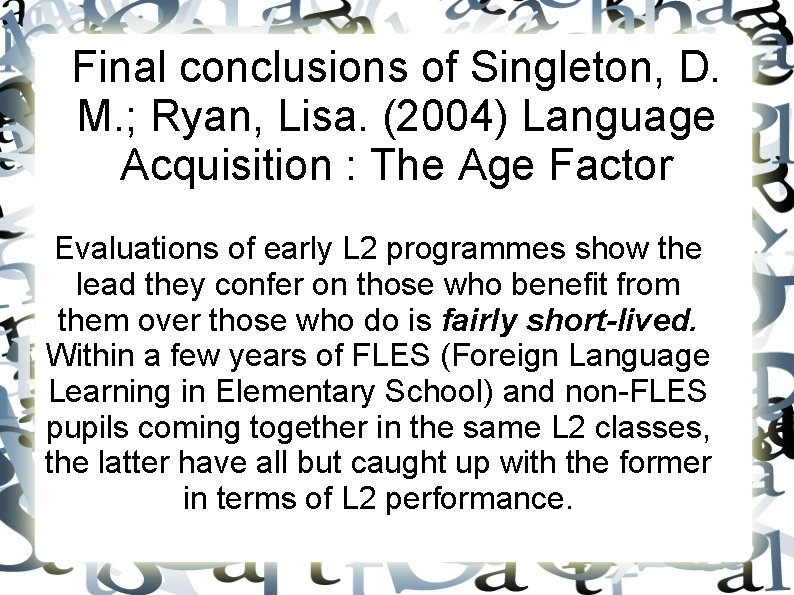

Final conclusions of Singleton, D. M. ; Ryan, Lisa. (2004) Language Acquisition : The Age Factor Evaluations of early L 2 programmes show the lead they confer on those who benefit from them over those who do is fairly short-lived. Within a few years of FLES (Foreign Language Learning in Elementary School) and non-FLES pupils coming together in the same L 2 classes, the latter have all but caught up with the former in terms of L 2 performance.

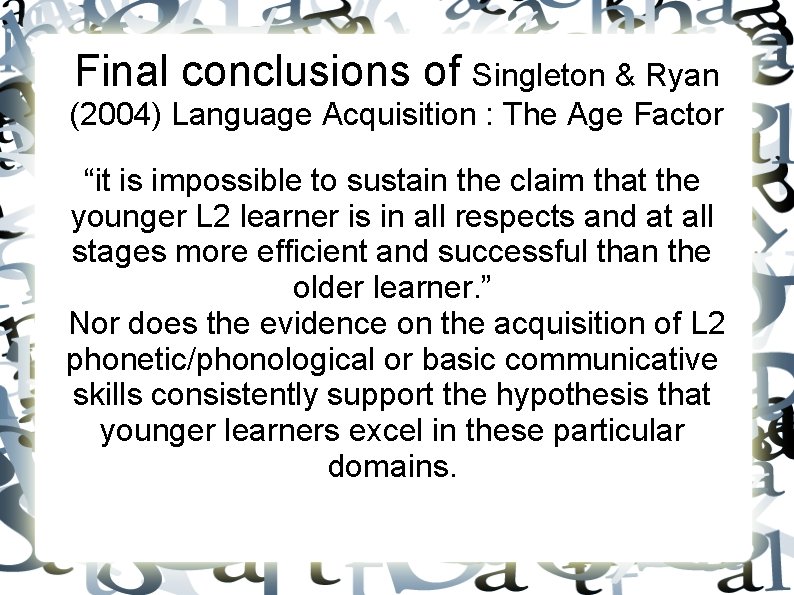

Final conclusions of Singleton & Ryan (2004) Language Acquisition : The Age Factor “it is impossible to sustain the claim that the younger L 2 learner is in all respects and at all stages more efficient and successful than the older learner. ” Nor does the evidence on the acquisition of L 2 phonetic/phonological or basic communicative skills consistently support the hypothesis that younger learners excel in these particular domains.

Choosing Early or Late Immersion It is impossible to decide which is better based on existing evidence (Nikolov & Djigunovic, 2006) BUT- Early start may be preferable more for the way it builds motivation and attitude, not necessarily for language learning gains, AND Early start is typically associated with more long-term exposure

Final conclusions of Singleton & Ryan (2004) Language Acquisition : The Age Factor “It is thus impossible to weigh in an informed fashion the benefits of early L 2 instruction against the costs thereof. ” The long-term positive effects of early L 2 instruction have not yet been firmly established, BUT we can at least rely on there being no negative effects (e. g. , on L 1 learning) associated with the early introduction of an L 2

Canadian Immersion Findings French Immersion research: (two Romance languages) One year of immersion starting in 7 th grade is equal to three years starting in first grade (Hakuta & Gould, 1987)

Final conclusions of Singleton & Ryan (2004) Language Acquisition : The Age Factor Those who favour early instruction must use other arguments, the benefits of increased exposure to the L 2. the desirability of early stimulation generally; the advantage of starting some subjects early in the context of the modern crowded curriculum; the educational merits of early contact with another culture;

Exposure time is crucial UNDISPUTED: Amount of exposure time per se is the crucial factor in differentiating levels of language proficiency. NOT: Age when exposure occurs

Croatian project of early FLL (Mihaljević Djigunović & Vilke, 2000) GOAL: find the optimal starting age Eight-year, tracked over 1, 000 first graders (age 6 -7) Intensive exposure approximated conditions available in natural SL contexts. Experimental group: Year 1, Control group: Year 4 Experimental group was significantly better at pronunciation, orthography, vocabulary and a C-test (requires implicit knowledge of English). ALSO: Better oral, conversational ability BUT, not much better at reading or tests that tapped explicit knowledge of the grammatical system

Ultimate Attainment 'Concerning the hypothesis that those who begin learning a second language in childhood in the long run generally achieve a higher level of proficiency than those who begin later in life, one can say that there is some good supportive evidence and that there is no actual counter-evidence' (Singleton, 1989: 137).

Even of few hours a week of early learning may help (Larson-Hall, 2008) A study of Japanese college-age students controlled for the amount of input: Contrary to predictions that age only plays a role in naturalistic or immersion environments, the present study found evidence that a younger starting age makes a modest difference to both phonological and basic morphosyntactic abilities, BUT advantages only emerged later

Four interacting factors A More Complete Model (Moyer, 2004) 1)Starting age 2)Psychological processing 3)Cognitive processing 4)Social Processing

Final Warnings of Singleton & Ryan (2004) Language Acquisition : The Age Factor In order to avoid a negative L 2 early learning experience, you need. . . appropriate learning materials, teacher training and commitment, positive public attitudes towards the target language Bilingual teachers are better!

The teacher is crucial Hungarian students’ attitudes and motivation (Nikolov, 1999) have shown that the most crucial motivational factors function on the classroom level: the teacher’s role is extremely important, intrinsically motivating and cognitively challenging tasks tuned to learners’ age and level. ALSO Important: Continuity from year to year (Edelenbos & Kubanek, 2009)

Policy recommendations • Develop a very clear understanding of the specific goals of early English education • Assess appropriate outcomes: e. g. , comprehension and social interaction • Allow Arabic in the classroom • Weigh the costs and benefits of delaying English

English medium instruction • Reach a clear threshold before immersing students in a content class taught in English • Make sure content teachers understand support language learning • Don’t rely on indirect acquisition, teach language explicitly • Modify materials, tests, instruction • Be patient: allow more time for reaching language and content goals simultaneously • CLIL = Content Learning Integrated with Language

Competition with Formal Arabic? Research needed on factors like: Diglossia: Formal Arabic vs. spoken dialects Students process formal Arabic as a foreign language (Science. Daily, 2009) Unvoweled orthography Compared to English, the Arabic script appears to make heavy demands on the visualspatial processing of letters, roots, affixes, and short vowels (Abu-Rabia, 2001; Share & Levin, 1999).

References Bialystok, E. , Craik, F. I. , Klein, R. , & Viswanathan, M. (2004). Bilingualism, aging, and cognitive control: Evidence from the Simon task. Psychology and Aging, 19, 290– 303. De. Keyser, R. M. (2000). The robustness of critical period effects in second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 22(04), 499– 533. Edelenbos, P. , & Kubanek, A. (2009). Early foreign language learning: Published research, good practice and main principles. The Age Factor and Early Language Learning, 39. Hakuta, K. , & Gould, L. J. (1987). Synthesis of research on bilingual education. Educational Leadership, 44(6), 38– 45. Larson-Hall, J. (2008). Weighing the benefits of studying a foreign language at a younger starting age in a minimal input situation. Second Language Research, 24(1), 35 -63.

References Marinova-Todd, S. H. , Marshall, D. B. , & Snow, C. E. (2000). Three misconceptions about age and L 2 learning. TESOL quarterly, 34(1), 9– 34. Moyer, A. (2004). Age, accent, and experience in second language acquisition: an integrated approach to critical period inquiry. Multilingual Matters Ltd. Nikolov, M. (2009). The Age Factor and Early Language Learning. Walter de Gruyter. Nikolov, M. , & Djigunovic, J. M. (2006). Recent Research on Age, Second Language Acquisition, and Early Foreign Language Learning. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 26, 234 -260. Singleton, D. (2001). Age and Second Language Acquisition. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 21, 77 -89.