Does EarlyLife Income Inequality Predict LaterLife SelfReported Health

- Slides: 18

Does Early-Life Income Inequality Predict Later-Life Self-Reported Health? Evidence from Three Countries Dean R. Lillard 1, 3, Richard V. Burkhauser 2, 3, 4, Markus H. Hahn 4 and Roger Wilkins 4 1 Ohio State University, 2 Cornell University, 3 DIW-Berlin, 4 Melbourne Institute, University of Melbourne July 2013 www. fbe. unimelb. edu. a u

Introduction – What’s the link between inequality and health? (And why does it matter? ) Hypothesised effects (Leigh, Jencks and Smeeding, 2009) • Absolute income hypothesis (health concave in income) • Relative income (or relative deprivation) hypothesis (“status anxiety” – chronic stress from relative deprivation) • Violent crime (including second-order effects on stress) • Public spending (not necessarily only health-related) • Social capital and trust (“income inequality hypothesis” of Wilkinson (1996) – various mechanisms, including effects on demands for public spending) (Matters for both health policy and redistribution policy) www. fbe. unimelb. edu. a u

Empirical evidence – Earlier studies (mostly 1980 s and 1990 s) (+) Infant mortality (–) Life expectancy (–) Average at death (+) Mortality risk (–) Self-reported health www. fbe. unimelb. edu. a u

Shortcomings of older literature • Cross-sectional data • Health usually measured by aggregate statistic for whole country • Not always comparable across countries • Often for single or limited number of years • Failure to account for substantial heterogeneity (lack of controls) • Weak theoretical support • Relates current health to current inequality www. fbe. unimelb. edu. a u

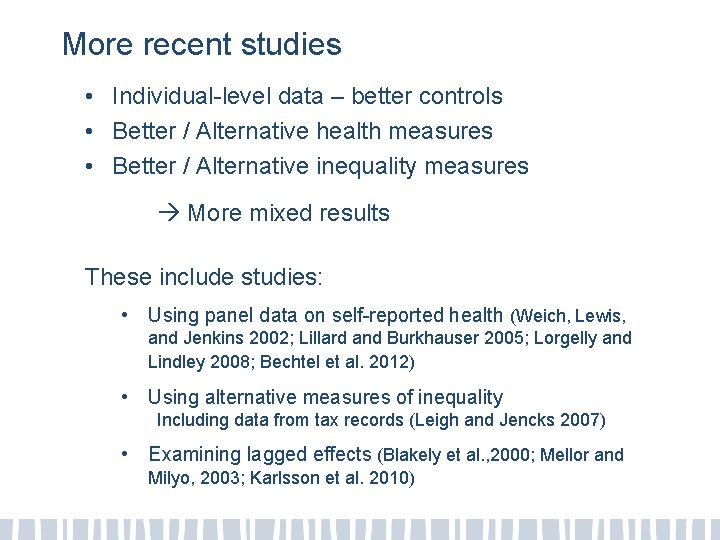

More recent studies • Individual-level data – better controls • Better / Alternative health measures • Better / Alternative inequality measures More mixed results These include studies: • Using panel data on self-reported health (Weich, Lewis, and Jenkins 2002; Lillard and Burkhauser 2005; Lorgelly and Lindley 2008; Bechtel et al. 2012) • Using alternative measures of inequality Including data from tax records (Leigh and Jencks 2007) • Examining lagged effects (Blakely et al. , 2000; Mellor and Milyo, 2003; Karlsson et al. 2010) www. fbe. unimelb. edu. a u

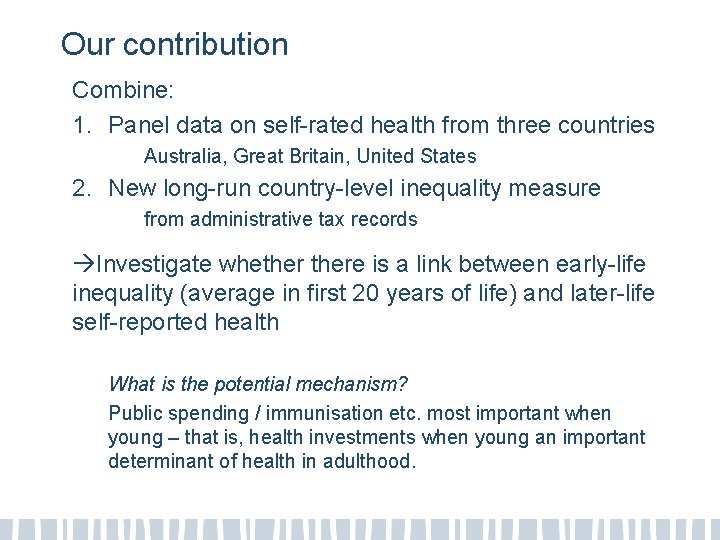

Our contribution Combine: 1. Panel data on self-rated health from three countries Australia, Great Britain, United States 2. New long-run country-level inequality measure from administrative tax records Investigate whethere is a link between early-life inequality (average in first 20 years of life) and later-life self-reported health What is the potential mechanism? Public spending / immunisation etc. most important when young – that is, health investments when young an important determinant of health in adulthood. www. fbe. unimelb. edu. a u

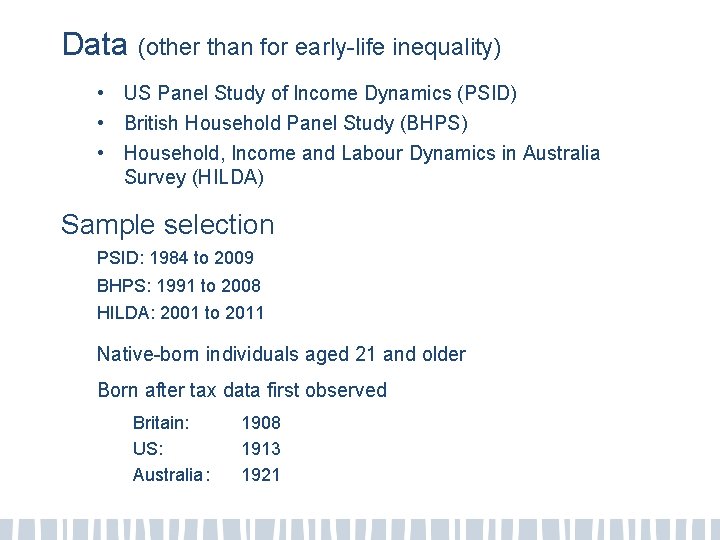

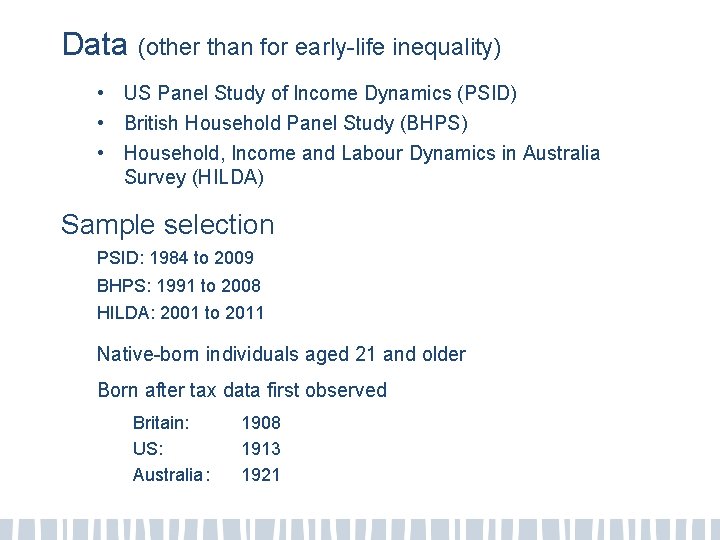

Data (other than for early-life inequality) • US Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) • British Household Panel Study (BHPS) • Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey (HILDA) Sample selection PSID: 1984 to 2009 BHPS: 1991 to 2008 HILDA: 2001 to 2011 Native-born individuals aged 21 and older Born after tax data first observed Britain: US: Australia : www. fbe. unimelb. edu. a u 1908 1913 1921

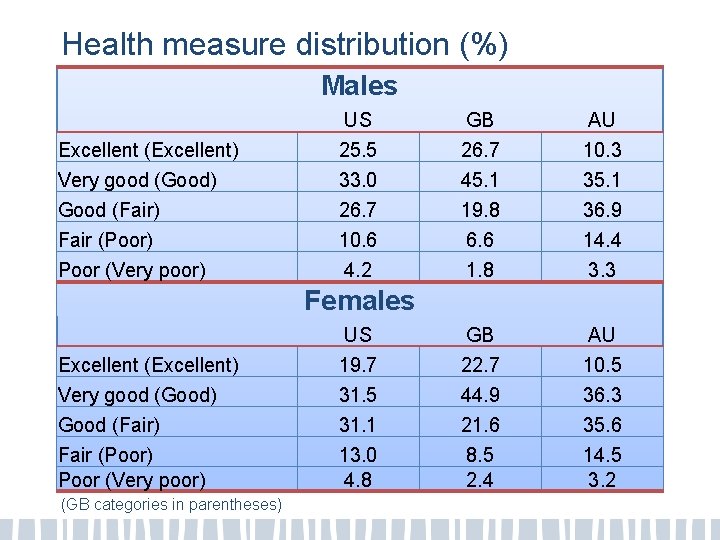

Health measure 5 -point scale in all countries: PSID: Would you say your health in general is excellent, very good, fair or poor? BHPS: Please think back over the last 12 months about how your health has been. Compared to people of your own age, would you say that your health has on the whole been excellent, good, fair, poor or very poor? HILDA: In general, would you say your health is excellent, very good, fair or poor? Limitations: • Not entirely certain what is being measured, especially by HILDA and PSID (time frame, reference point) • Potential endogeneity (eg, Johnston et al. , 2009) www. fbe. unimelb. edu. a u

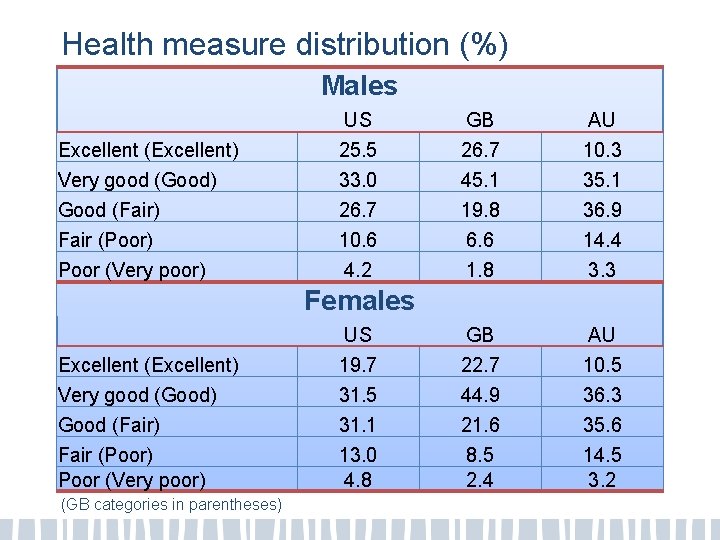

Health measure distribution (%) Males Excellent (Excellent) Very good (Good) Good (Fair) Fair (Poor) Poor (Very poor) US 25. 5 33. 0 26. 7 10. 6 4. 2 GB 26. 7 45. 1 19. 8 6. 6 1. 8 AU 10. 3 35. 1 36. 9 14. 4 3. 3 GB 22. 7 44. 9 21. 6 8. 5 2. 4 AU 10. 5 36. 3 35. 6 14. 5 3. 2 Females Excellent (Excellent) Very good (Good) Good (Fair) Fair (Poor) Poor (Very poor) (GB categories in parentheses) US 19. 7 31. 5 31. 1 13. 0 4. 8

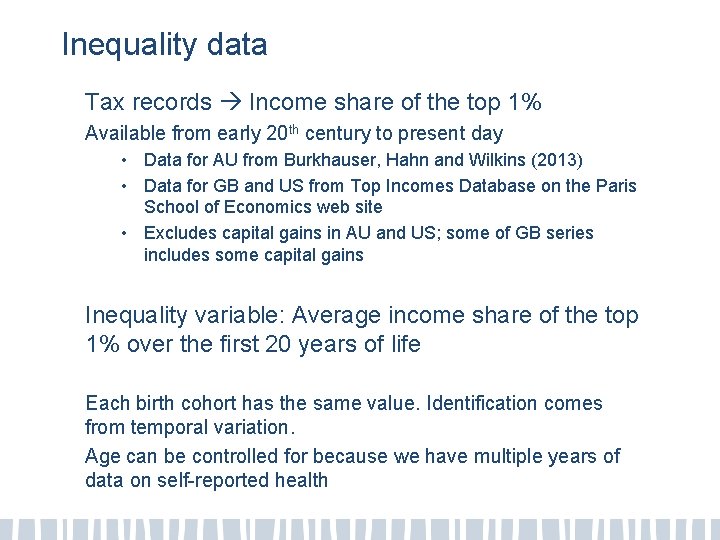

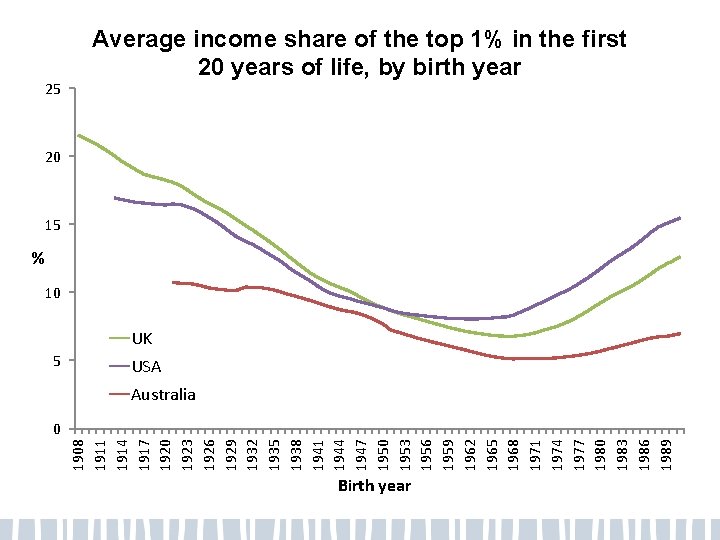

Inequality data Tax records Income share of the top 1% Available from early 20 th century to present day • Data for AU from Burkhauser, Hahn and Wilkins (2013) • Data for GB and US from Top Incomes Database on the Paris School of Economics web site • Excludes capital gains in AU and US; some of GB series includes some capital gains Inequality variable: Average income share of the top 1% over the first 20 years of life Each birth cohort has the same value. Identification comes from temporal variation. Age can be controlled for because we have multiple years of data on self-reported health www. fbe. unimelb. edu. a u

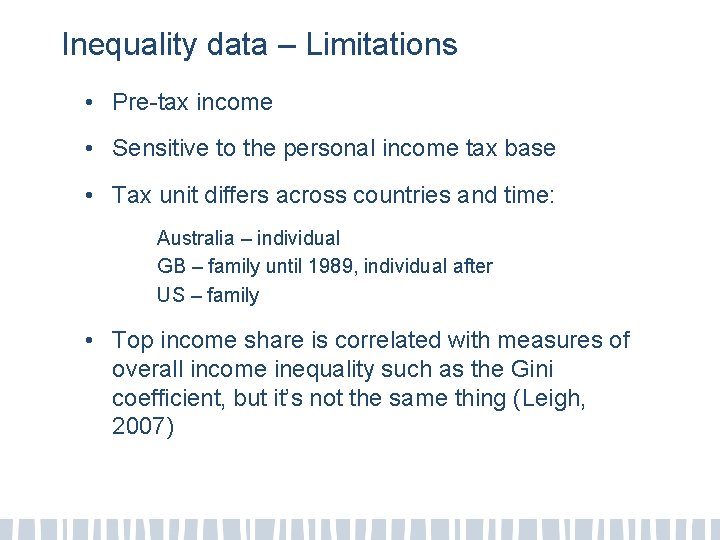

Inequality data – Limitations • Pre-tax income • Sensitive to the personal income tax base • Tax unit differs across countries and time: Australia – individual GB – family until 1989, individual after US – family • Top income share is correlated with measures of overall income inequality such as the Gini coefficient, but it’s not the same thing (Leigh, 2007) www. fbe. unimelb. edu. a u

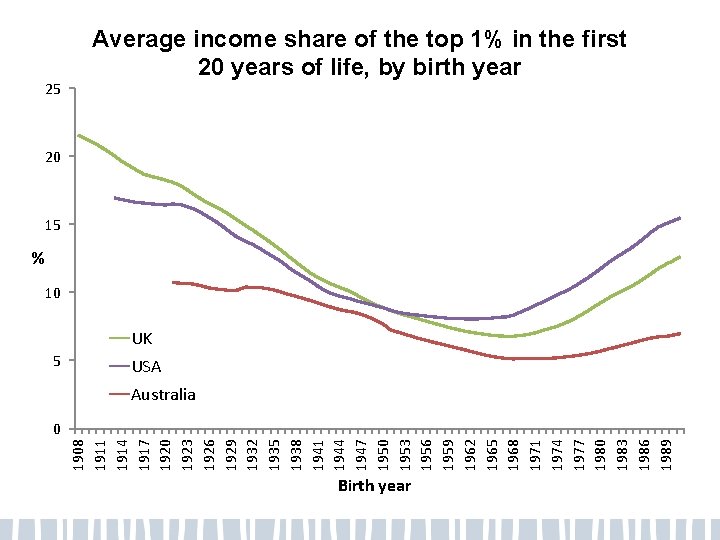

25 Average income share of the top 1% in the first 20 years of life, by birth year 20 15 % 10 UK 5 USA Australia 1908 1911 1914 1917 1920 1923 1926 1929 1932 1935 1938 1941 1944 1947 1950 1953 1956 1959 1962 1965 1968 1971 1974 1977 1980 1983 1986 1989 0 Birth year www. fbe. unimelb. edu. a u

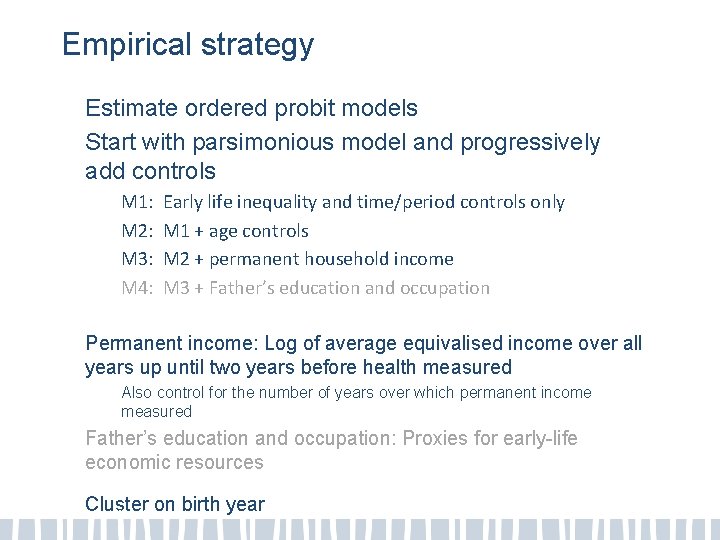

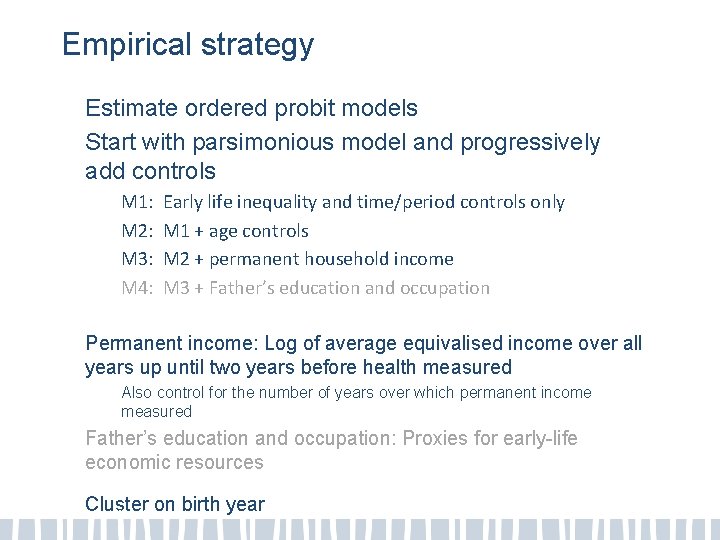

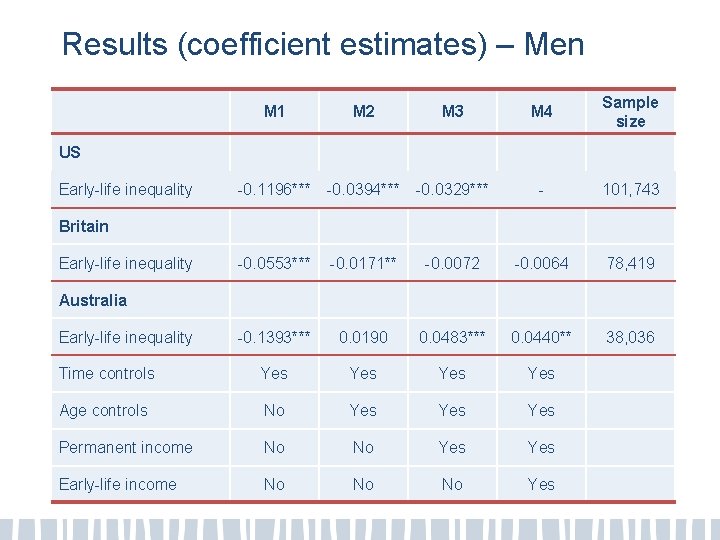

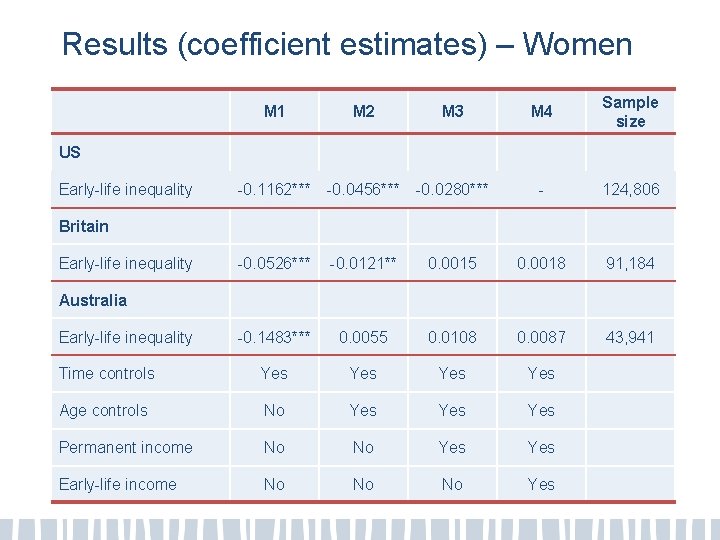

Empirical strategy Estimate ordered probit models Start with parsimonious model and progressively add controls M 1: M 2: M 3: M 4: Early life inequality and time/period controls only M 1 + age controls M 2 + permanent household income M 3 + Father’s education and occupation Permanent income: Log of average equivalised income over all years up until two years before health measured Also control for the number of years over which permanent income measured Father’s education and occupation: Proxies for early-life economic resources Cluster on birth year www. fbe. unimelb. edu. a u

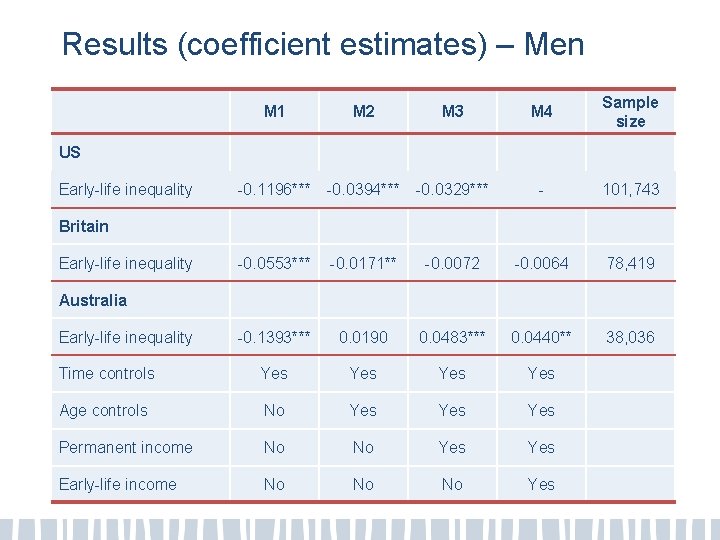

Results (coefficient estimates) – Men M 1 M 2 M 3 M 4 Sample size -0. 1196*** -0. 0394*** -0. 0329*** - 101, 743 -0. 0553*** -0. 0171** US Early-life inequality Britain Early-life inequality -0. 0072 -0. 0064 Australia Early-life inequality 78, 419 -0. 1393*** 0. 0190 0. 0483*** 0. 0440** 38, 036 Time controls Yes Yes Age controls No Yes Yes Permanent income No No Yes Early-life income No No No Yes www. fbe. unimelb. edu. a u

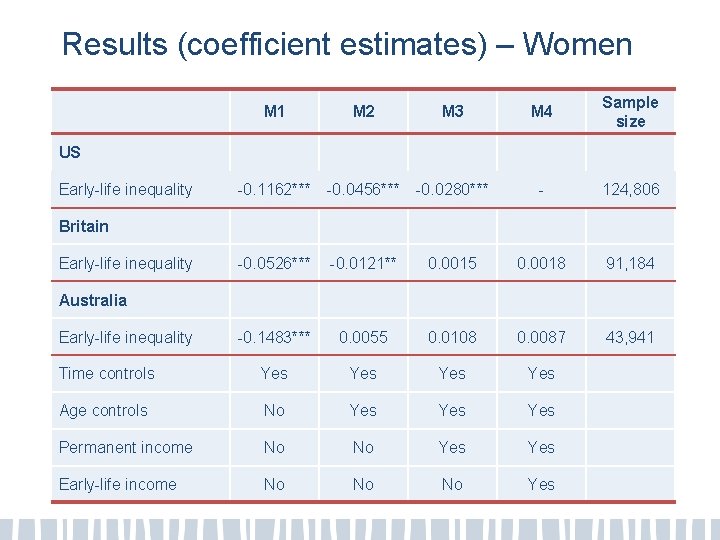

Results (coefficient estimates) – Women M 1 M 2 M 3 M 4 Sample size -0. 1162*** -0. 0456*** -0. 0280*** - 124, 806 -0. 0526*** -0. 0121** -0. 1483*** 0. 0055 0. 0108 0. 0087 43, 941 Time controls Yes Yes Age controls No Yes Yes Permanent income No No Yes Early-life income No No No Yes US Early-life inequality Britain Early-life inequality Australia Early-life inequality www. fbe. unimelb. edu. a u 0. 0015 0. 0018 91, 184

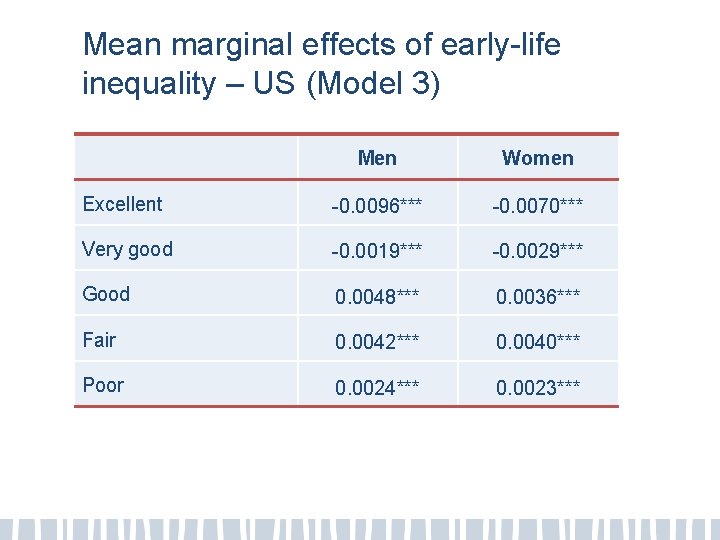

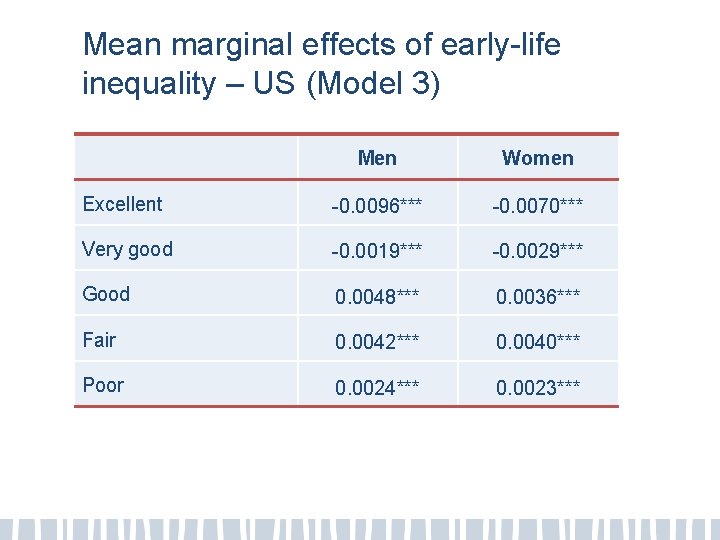

Mean marginal effects of early-life inequality – US (Model 3) Men Women Excellent -0. 0096*** -0. 0070*** Very good -0. 0019*** -0. 0029*** Good 0. 0048*** 0. 0036*** Fair 0. 0042*** 0. 0040*** Poor 0. 0024*** 0. 0023*** www. fbe. unimelb. edu. a u

Robustness checks and caveats • Restrict to the 2001 -2009 period for all countries • Restrict to the 1991 -2009 period for US and GB • Alternative specifications of time effects • Alternative specifications of age effects Yet to examine whether US result robust to inclusion of measures of early-life income. www. fbe. unimelb. edu. a u

Discussion Focus on current inequality and current health theoretically weak We find evidence that early-life inequality matters in the US Permanent income and early-life income also appear to matter Further work: • Early-life income measure for US • Consider differences in effects of early-life income inequality by level of early-life income • Consider inequality at other ages • Explore other (objective? ) measures of health (but data limitations) www. fbe. unimelb. edu. a u

Write a compound inequality as an absolute value inequality

Write a compound inequality as an absolute value inequality How to calculate real gdp per capita

How to calculate real gdp per capita Tax payable

Tax payable Operating income meaning

Operating income meaning Deferred tax asset journal entry

Deferred tax asset journal entry Chcch3 lewis structure

Chcch3 lewis structure What does vsepr stand for

What does vsepr stand for What does the word predict

What does the word predict How to solve inequality

How to solve inequality 6-5 linear inequalities answer key

6-5 linear inequalities answer key Does notes receivable go on the income statement

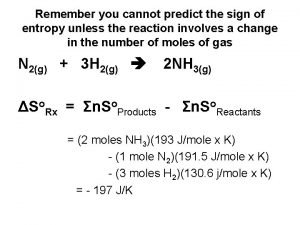

Does notes receivable go on the income statement Predict the sign of the entropy change

Predict the sign of the entropy change Vipers skills

Vipers skills Vipers prediction questions

Vipers prediction questions Nnn zkratka

Nnn zkratka Does isopropanol conduct electricity

Does isopropanol conduct electricity Predictogram

Predictogram Variabel sekunder

Variabel sekunder Predict cyber crime

Predict cyber crime