DNAbased Spatial Computing Toward Diffusionlimited Computation Chris Dwyer

DNA-based Spatial Computing: Toward Diffusion-limited Computation Chris Dwyer Assistant Professor Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Department of Computer Science Spatial Computing Workshop / SASO, September 2009 Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

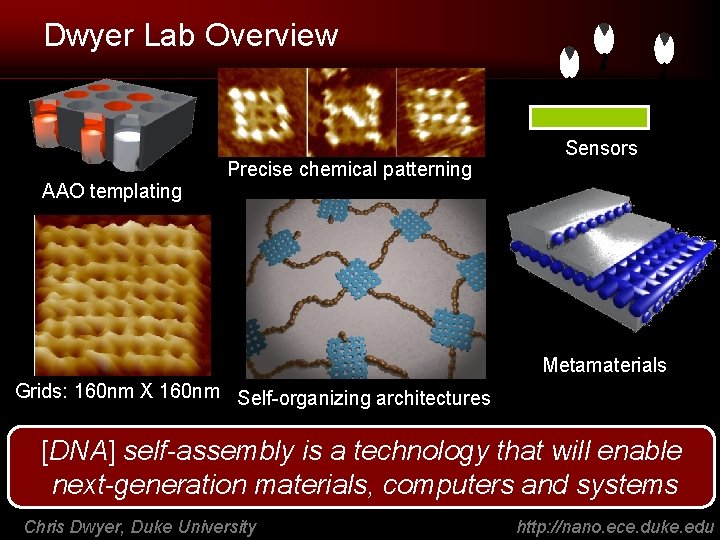

Dwyer Lab Overview AAO templating Precise chemical patterning Sensors Metamaterials Grids: 160 nm X 160 nm Self-organizing architectures [DNA] self-assembly is a technology that will enable next-generation materials, computers and systems Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

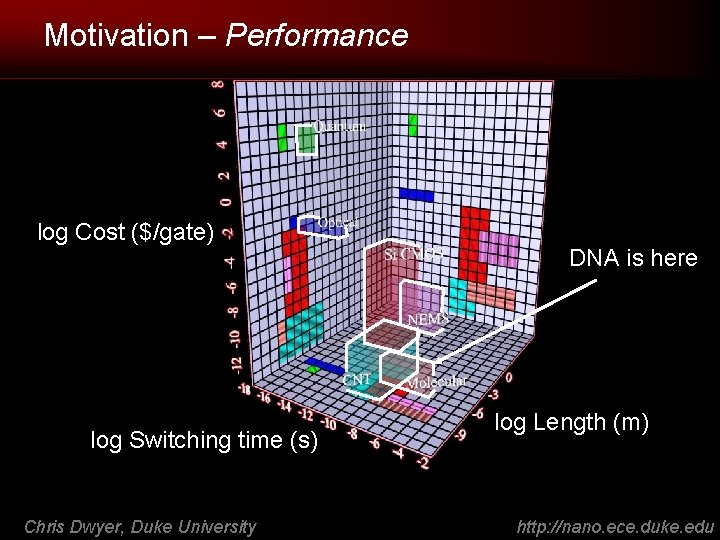

Motivation – Performance log Cost ($/gate) log Switching time (s) Chris Dwyer, Duke University DNA is here log Length (m) http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

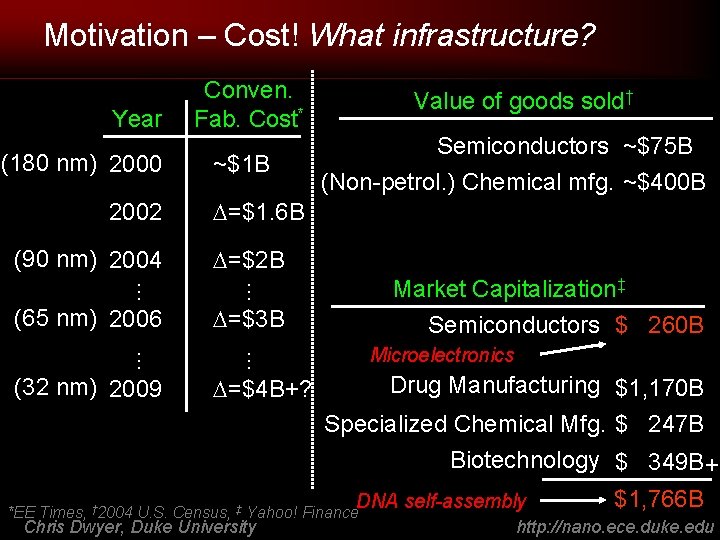

Motivation – Cost! What infrastructure? Year (180 nm) 2000 2002 (90 nm) 2004 Semiconductors ~$75 B (Non-petrol. ) Chemical mfg. ~$400 B =$1. 6 B =$2 B Market Capitalization‡ Semiconductors $ 260 B =$3 B Microelectronics … … (32 nm) 2009 ~$1 B Value of goods sold† … … (65 nm) 2006 Conven. Fab. Cost* =$4 B+? Drug Manufacturing $1, 170 B Specialized Chemical Mfg. $ 247 B Biotechnology $ 349 B+ DNA self-assembly *EE Times, † 2004 U. S. Census, ‡ Yahoo! Finance Chris Dwyer, Duke University $1, 766 B http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

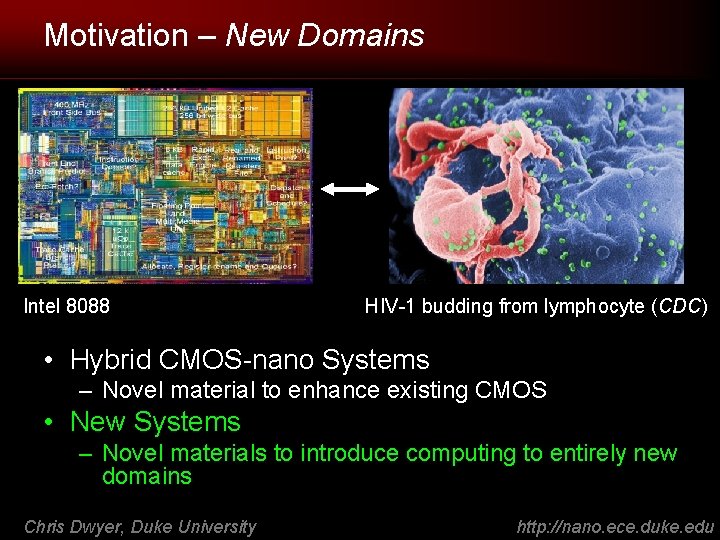

Motivation – New Domains Intel 8088 HIV-1 budding from lymphocyte (CDC) • Hybrid CMOS-nano Systems – Novel material to enhance existing CMOS • New Systems – Novel materials to introduce computing to entirely new domains Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

Outline • Self-assembled Nanostructures – DNA – Scaffolds • Devices – Fluorescence Resonance Energy Pathways and Logic • Self-assembled Systems – Fusing Logic and Sensors – Diffusion-limited Computation • Conclusions Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

DNA • A DNA strand: – A linear array of bases (A, T, G, and C) – Directional (one end is distinct from the other) – In nature, the source of genetic information • DNA will form a double helix: – When the bases on each strand (aligned “head-totoe”) are complementary: A with T, and G with C – But only under certain “natural” environmental conditions (low) temperatures (Tm: sequence dependent) and in an ionic solution. Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

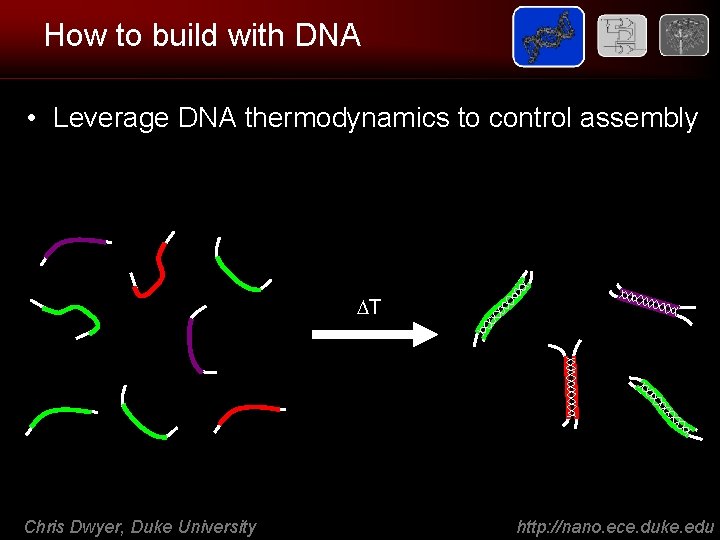

How to build with DNA • Leverage DNA thermodynamics to control assembly T Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

How to build with DNA • Double helix (B-form) has well-known geometric properties: – 3. 4 Å per base pitch along the helix – One complete turn between every 10 th and 11 th base • Flexibility: the bonds along the sugarphosphodiester backbone reptate – single stranded DNA has a strongly sequence dependent persistence length (but, it’s small ~1 nm) – double stranded DNA has a ~50 nm persistence length Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

Outline • Self-assembled Nanostructures – DNA – Scaffolds • Devices – Fluorescence Resonance Energy Pathways and Logic • Self-assembled Systems – Fusing Logic and Sensors – Diffusion-limited Computation • Conclusions Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

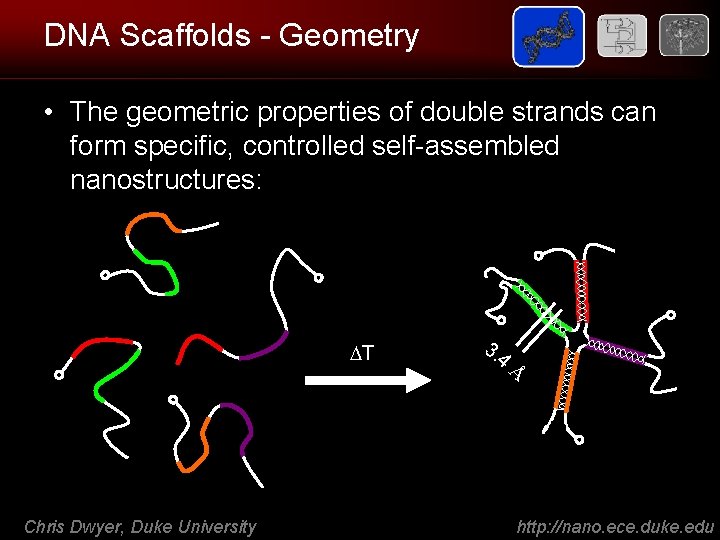

DNA Scaffolds - Geometry • The geometric properties of double strands can form specific, controlled self-assembled nanostructures: T Chris Dwyer, Duke University 3. 4 Å http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

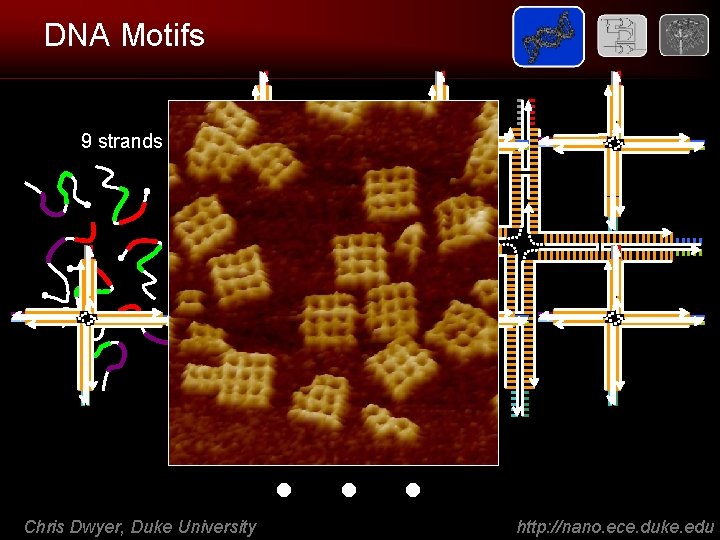

DNA Motifs 9 strands Chris Dwyer, Duke University . . . http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

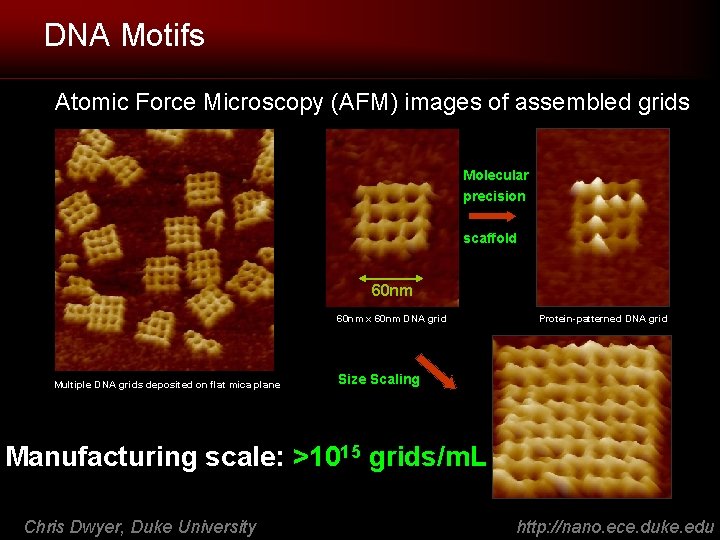

DNA Motifs Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) images of assembled grids Molecular precision scaffold 60 nm x 60 nm DNA grid Multiple DNA grids deposited on flat mica plane Protein-patterned DNA grid Size Scaling Manufacturing scale: >1015 grids/m. L Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

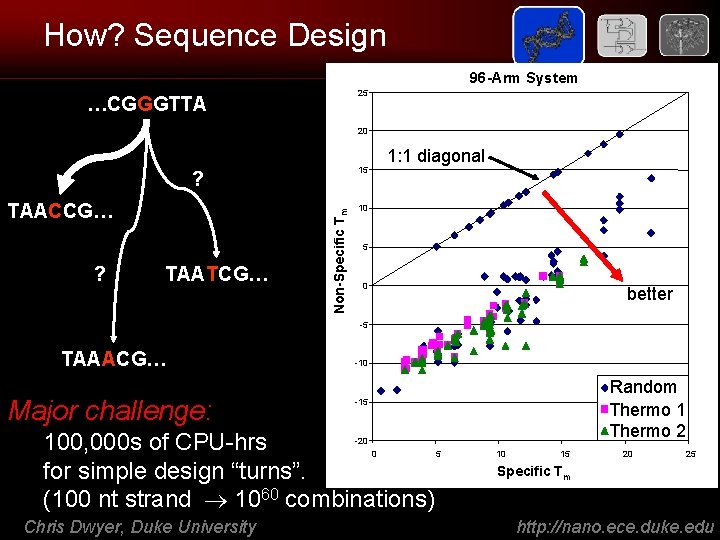

How? Sequence Design 96 -Arm System 25 …CGGGTTA 20 ? TAATCG… Non-Specific Tm ? TAACCG… 1: 1 diagonal 15 10 5 0 better -5 TAAACG… Major challenge: -10 Random Text Thermo 1 Thermo 2 -15 100, 000 s of CPU-hrs for simple design “turns”. (100 nt strand 1060 combinations) -20 0 Chris Dwyer, Duke University 5 10 15 20 25 Specific Tm http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

The DNA Foundry • • • Modeled after the modern silicon foundry Turn-key mfg. of precise nanostructures Leverages economies-of-scale Consolidated design services Uniform interface(s) for foundry services Leverage modularity and pipelining to minimize mfg. latency Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

Outline • Self-assembled Nanostructures – DNA – Scaffolds • Devices – Fluorescence Resonance Energy Pathways and Logic • Self-assembled Systems – Fusing Logic and Sensors – Self-organizing Computer Architectures • Conclusions Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

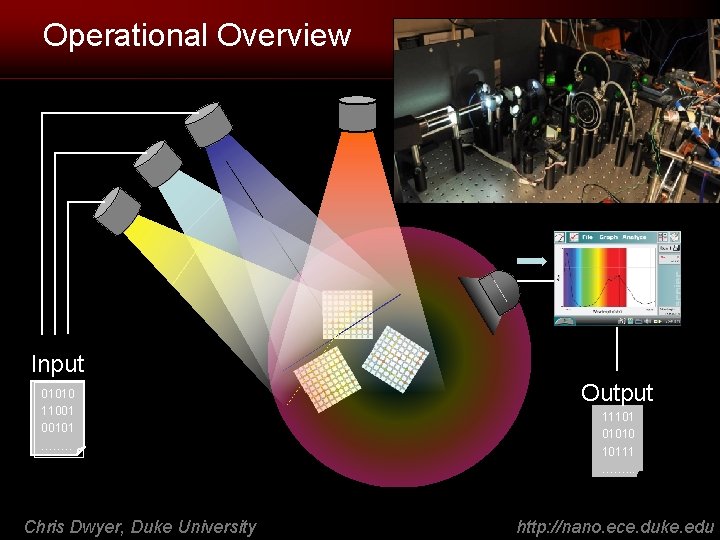

Operational Overview Input 01010 11001 00101 ……. . Chris Dwyer, Duke University Output 11101 01010 10111 ……. . . http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

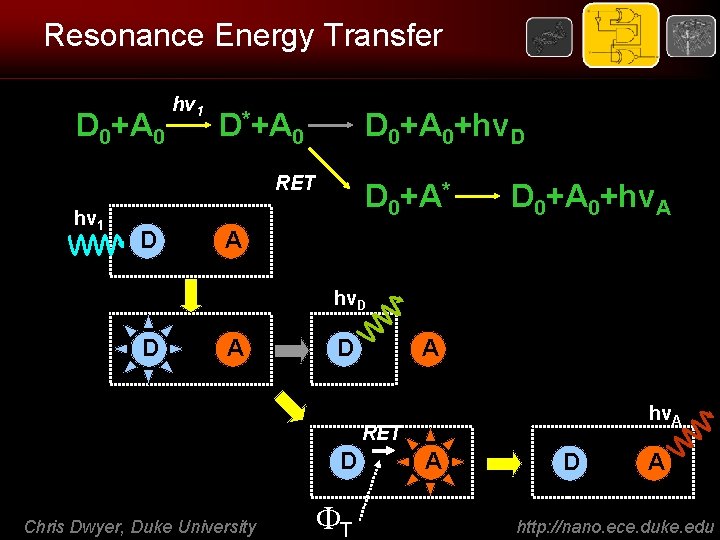

Resonance Energy Transfer D 0+A 0 hv 1 D*+A 0 D 0+A 0+hv. D RET hv 1 D D 0+A* D 0+A 0+hv. A A hv. D D A hv. A RET D Chris Dwyer, Duke University T A D A http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

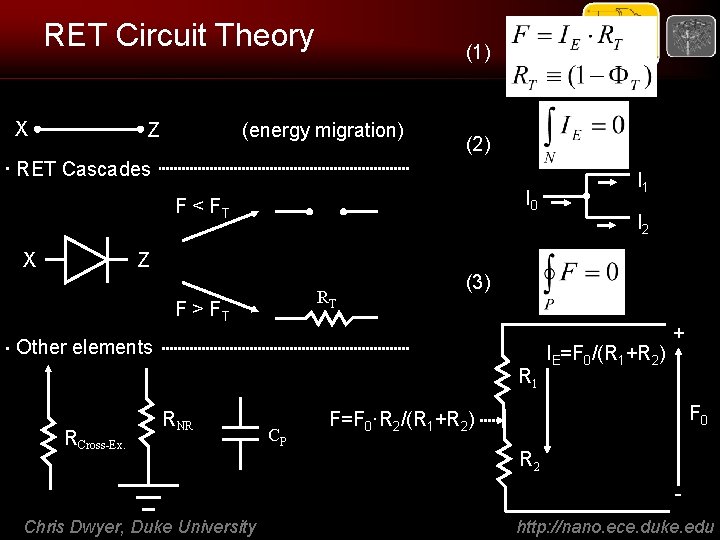

RET Circuit Theory X Z (1) (energy migration) (2) RET Cascades I 0 F < FT X Z RT F > FT R 1 RCross-Ex. CP I 2 (3) Other elements RNR I 1 IE=F 0/(R 1+R 2) + F 0 F=F 0·R 2/(R 1+R 2) R 2 - Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

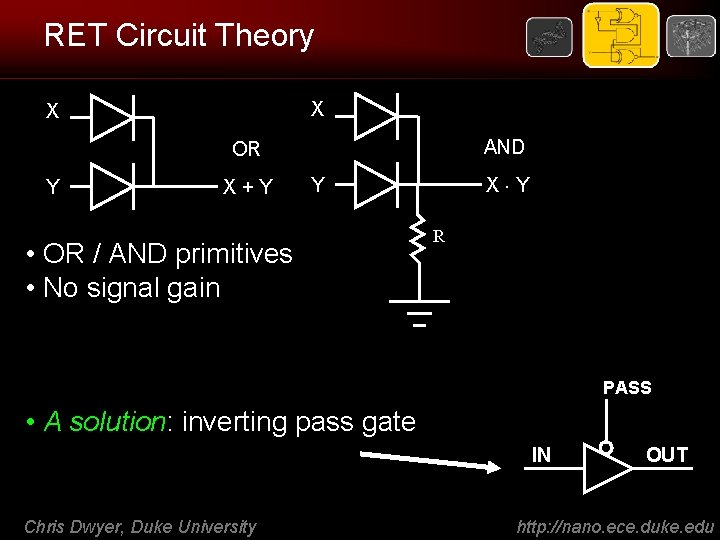

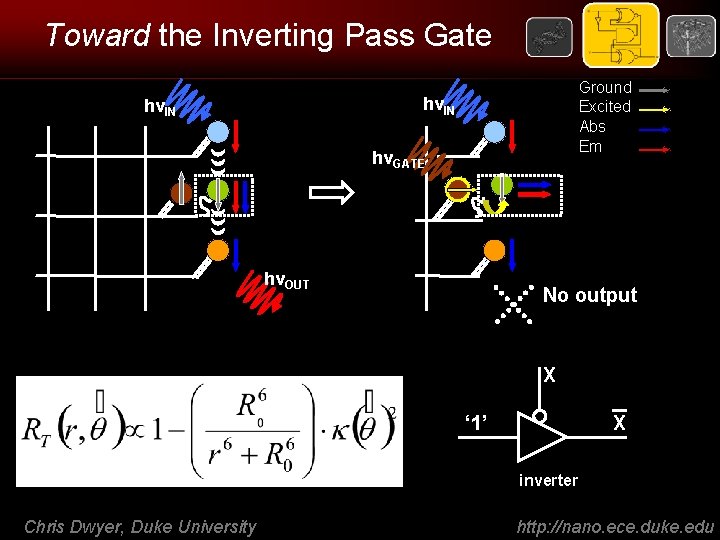

RET Circuit Theory X X AND OR Y X+Y X Y Y • OR / AND primitives • No signal gain R PASS • A solution: inverting pass gate IN Chris Dwyer, Duke University OUT http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

Toward the Inverting Pass Gate Ground Excited Abs Em hνIN hνGATE hνOUT No output X ‘ 1’ X inverter Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

Outline • Self-assembled Nanostructures – DNA – Scaffolds • Devices – Fluorescence Resonance Energy Pathways and Logic • Self-assembled Systems – Fusing Logic and Sensors – Diffusion-limited Computation • Conclusions Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

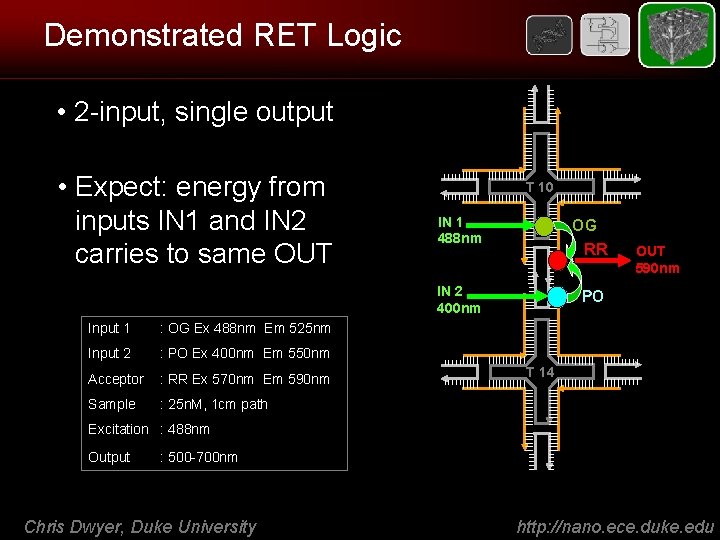

Demonstrated RET Logic • 2 -input, single output • Expect: energy from inputs IN 1 and IN 2 carries to same OUT Input 1 : OG Ex 488 nm Em 525 nm Input 2 : PO Ex 400 nm Em 550 nm Acceptor : RR Ex 570 nm Em 590 nm Sample : 25 n. M, 1 cm path T 10 IN 1 488 nm OG RR IN 2 400 nm PO OUT 590 nm T 14 Excitation : 488 nm Output : 500 -700 nm Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

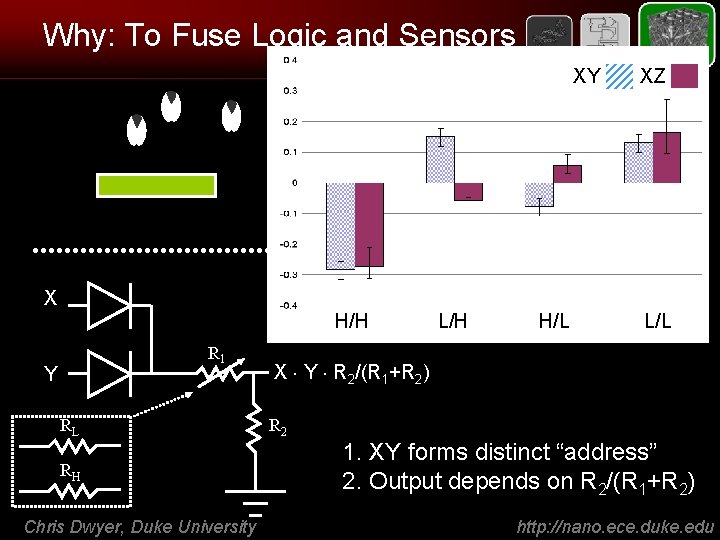

Why: To Fuse Logic and Sensors XY XZ Ligand-receptor binding (by AFM) - RNA - proteins - etc. X H/H R 1 Y RL RH Chris Dwyer, Duke University L/H H/L L/L X Y R 2/(R 1+R 2) R 2 1. XY forms distinct “address” 2. Output depends on R 2/(R 1+R 2) http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

Where to now? • Historically, the development of a circuit technology takes decades – RET logic is to the “handful” of gates (LSI) stage… • Given the alternatives, a new technology must have the potential to achieve fundamentally new capabilities DNA self-assembled systems can compute in spaces where conventional technologies cannot. Focus: biological environments Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

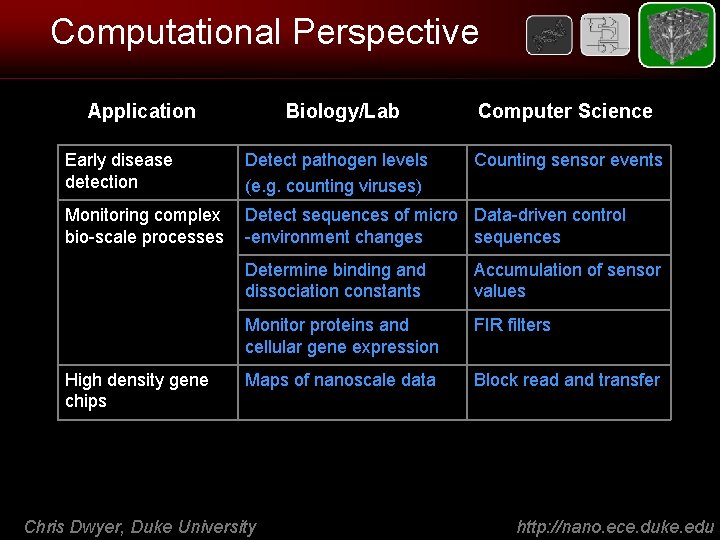

Computational Perspective Application Biology/Lab Computer Science Early disease detection Detect pathogen levels (e. g. counting viruses) Monitoring complex bio-scale processes Detect sequences of micro Data-driven control -environment changes sequences High density gene chips Counting sensor events Determine binding and dissociation constants Accumulation of sensor values Monitor proteins and cellular gene expression FIR filters Maps of nanoscale data Block read and transfer Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

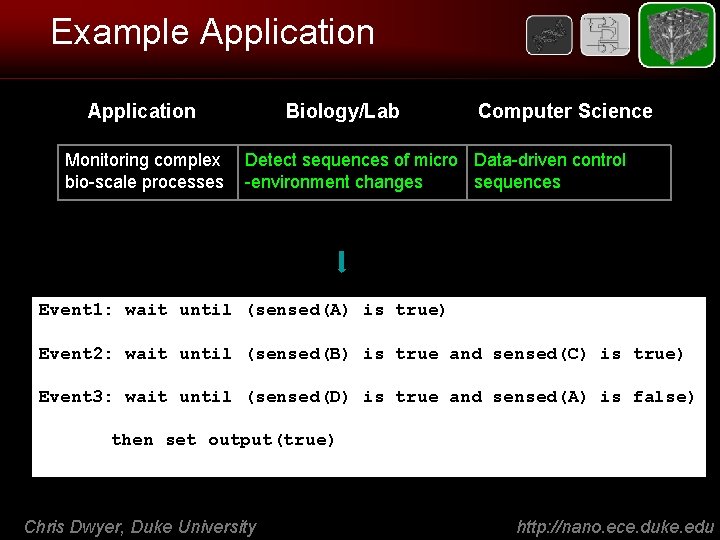

Example Application Monitoring complex bio-scale processes Biology/Lab Computer Science Detect sequences of micro Data-driven control -environment changes sequences Event 1: wait until (sensed(A) is true) Event 2: wait until (sensed(B) is true and sensed(C) is true) Event 3: wait until (sensed(D) is true and sensed(A) is false) then set output(true) Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

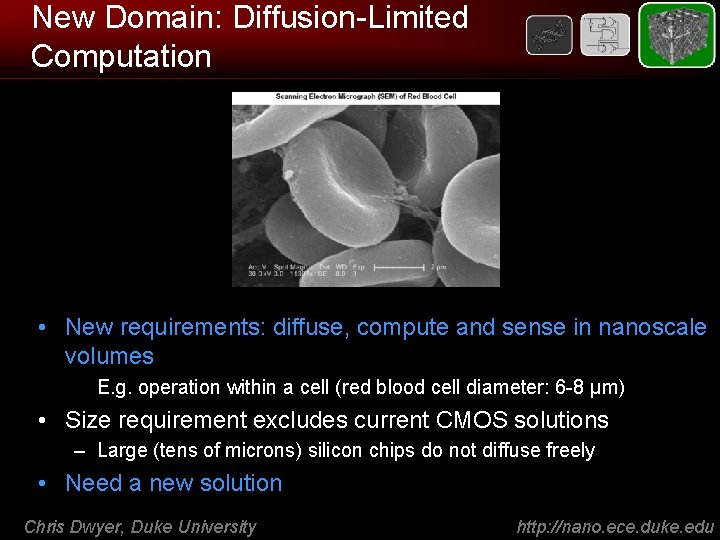

New Domain: Diffusion-Limited Computation • New requirements: diffuse, compute and sense in nanoscale volumes – E. g. operation within a cell (red blood cell diameter: 6 -8 μm) • Size requirement excludes current CMOS solutions – Large (tens of microns) silicon chips do not diffuse freely • Need a new solution Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

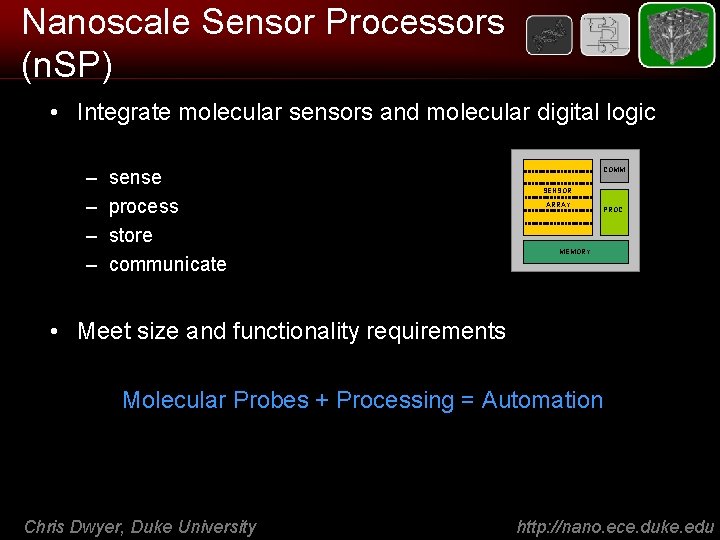

Nanoscale Sensor Processors (n. SP) • Integrate molecular sensors and molecular digital logic – – sense process store communicate COMM molecular information SENSOR ARRAY PROC MEMORY • Meet size and functionality requirements Molecular Probes + Processing = Automation Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

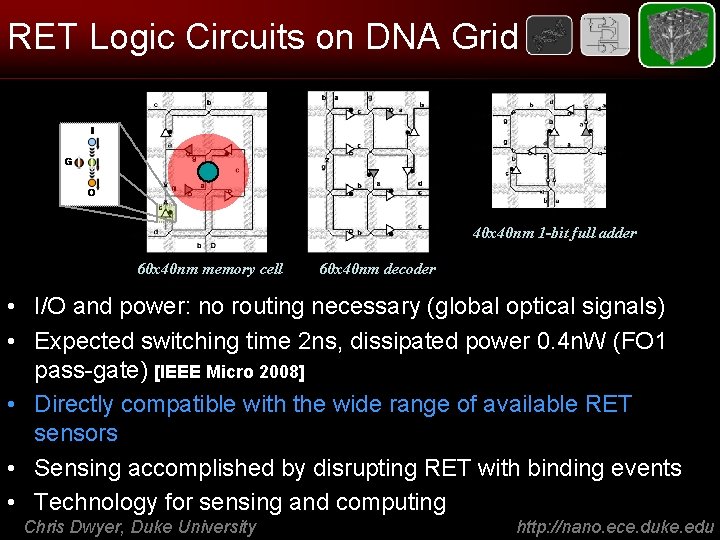

RET Logic Circuits on DNA Grid 40 x 40 nm 1 -bit full adder 60 x 40 nm memory cell 60 x 40 nm decoder • I/O and power: no routing necessary (global optical signals) • Expected switching time 2 ns, dissipated power 0. 4 n. W (FO 1 pass-gate) [IEEE Micro 2008] • Directly compatible with the wide range of available RET sensors • Sensing accomplished by disrupting RET with binding events • Technology for sensing and computing Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

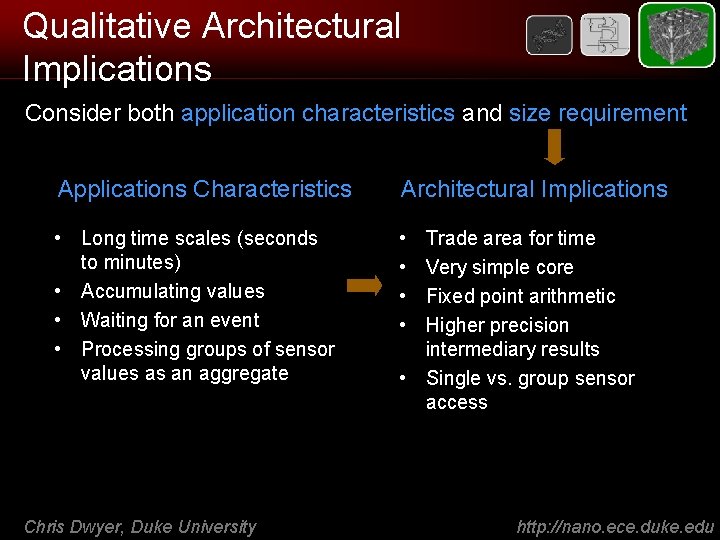

Qualitative Architectural Implications Consider both application characteristics and size requirement Applications Characteristics Architectural Implications • Long time scales (seconds to minutes) • Accumulating values • Waiting for an event • Processing groups of sensor values as an aggregate • • Chris Dwyer, Duke University Trade area for time Very simple core Fixed point arithmetic Higher precision intermediary results • Single vs. group sensor access http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

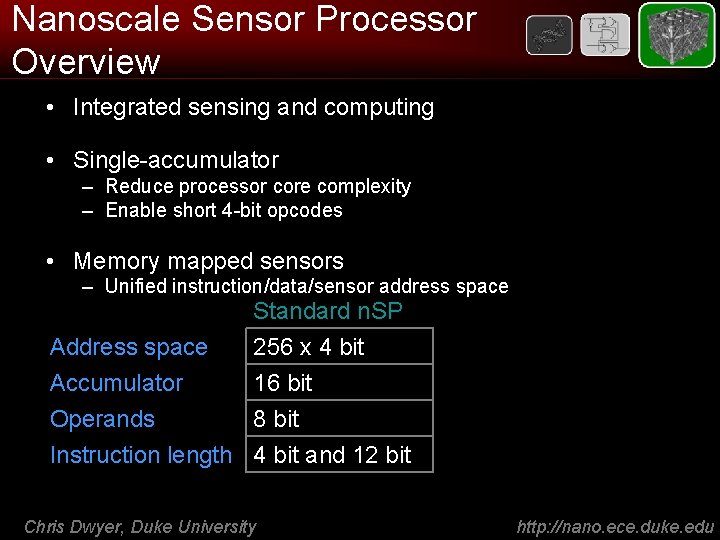

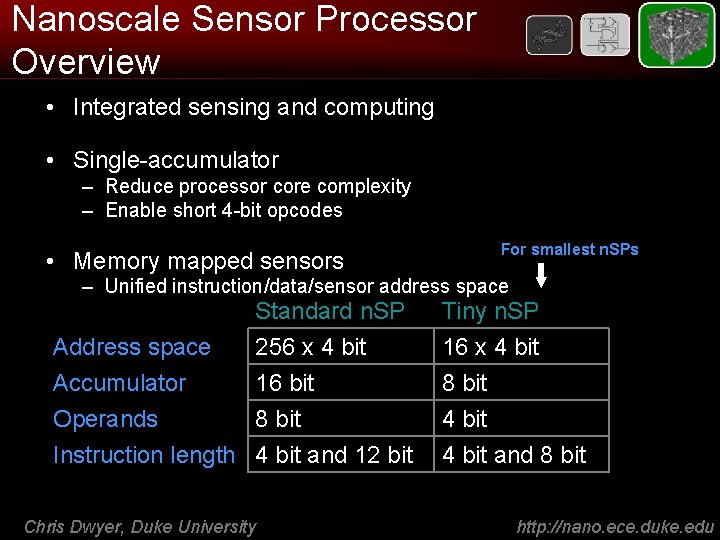

Nanoscale Sensor Processor Overview • Integrated sensing and computing • Single-accumulator – Reduce processor core complexity – Enable short 4 -bit opcodes • Memory mapped sensors – Unified instruction/data/sensor address space Accumulator Operands Standard n. SP 256 x 4 bit 16 bit 8 bit Instruction length 4 bit and 12 bit Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

Nanoscale Sensor Processor Overview • Integrated sensing and computing • Single-accumulator – Reduce processor core complexity – Enable short 4 -bit opcodes • Memory mapped sensors For smallest n. SPs – Unified instruction/data/sensor address space Accumulator Operands Standard n. SP 256 x 4 bit 16 bit 8 bit Instruction length 4 bit and 12 bit Chris Dwyer, Duke University Tiny n. SP 16 x 4 bit 8 bit 4 bit and 8 bit http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

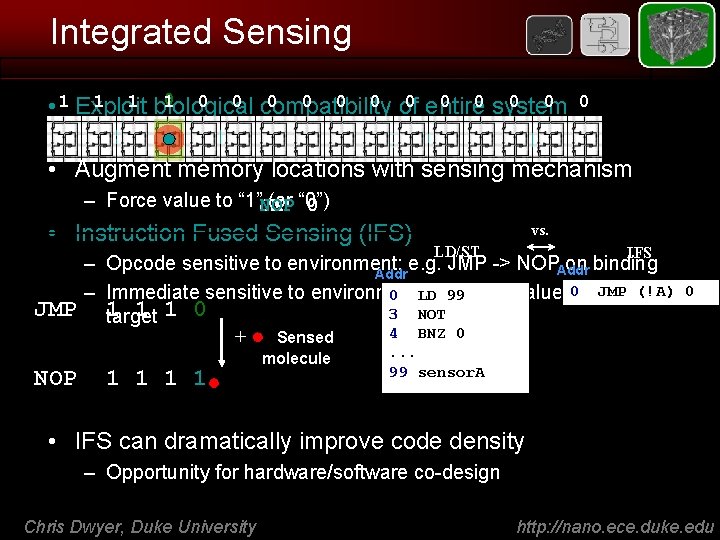

Integrated Sensing 0 1 1 biological 0 0 of 0 entire 0 0 system 0 0 1 0 0 compatibility • 1 Exploit 0 – RET: foundation for both sensing and computing • Augment memory locations with sensing mechanism – Force value to “ 1”JMP (or “ 0”) 0 NOP • Instruction Fused Sensing (IFS) vs. LD/ST IFS – Opcode sensitive to environment: e. g. JMP -> NOPAddr on binding Addr JMP (!A) – Immediate sensitive to environment: 0 LDe. g. 99 ALU value, 0 branch JMP 1 1 1 0 3 NOT target 4 BNZ 0 + Sensed NOP 1 1 molecule 0 . . . 99 sensor. A • IFS can dramatically improve code density – Opportunity for hardware/software co-design Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

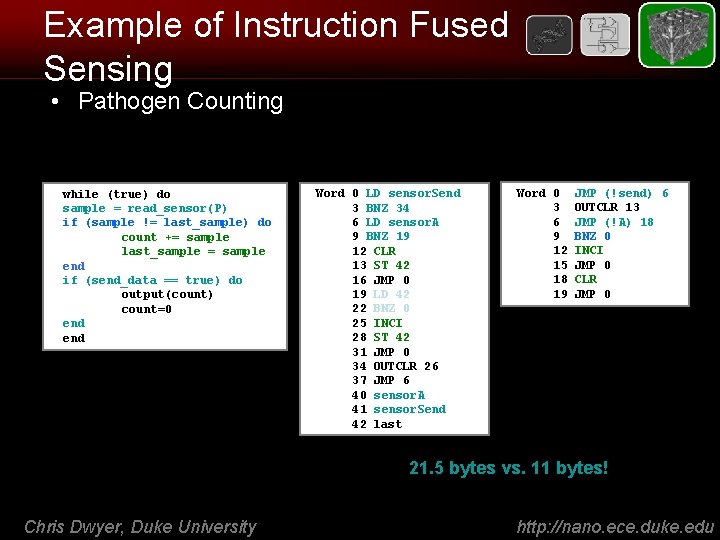

Example of Instruction Fused Sensing • Pathogen Counting 8 -bit counter pseudo-code while (true) do sample = read_sensor(P) if (sample != last_sample) do count += sample last_sample = sample end if (send_data == true) do output(count) count=0 end LD/ST Word 0 LD sensor. Send 3 BNZ 34 6 LD sensor. A 9 BNZ 19 12 CLR 13 ST 42 16 JMP 0 19 LD 42 22 BNZ 0 25 INCI 28 ST 42 31 JMP 0 34 OUTCLR 26 37 JMP 6 40 sensor. A 41 sensor. Send 42 last IFS Word 0 3 6 9 12 15 18 19 JMP (!send) 6 OUTCLR 13 JMP (!A) 18 BNZ 0 INCI JMP 0 CLR JMP 0 21. 5 bytes vs. 11 bytes! Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

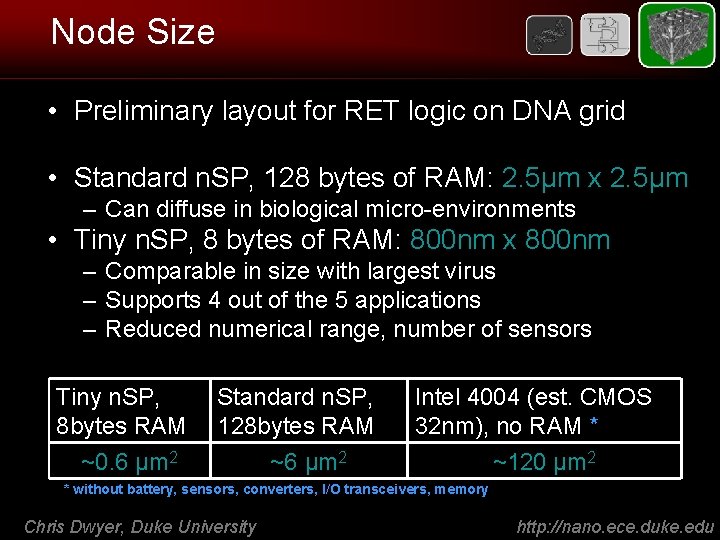

Node Size • Preliminary layout for RET logic on DNA grid • Standard n. SP, 128 bytes of RAM: 2. 5μm x 2. 5μm – Can diffuse in biological micro-environments • Tiny n. SP, 8 bytes of RAM: 800 nm x 800 nm – Comparable in size with largest virus – Supports 4 out of the 5 applications – Reduced numerical range, number of sensors Tiny n. SP, 8 bytes RAM Standard n. SP, 128 bytes RAM ~0. 6 μm 2 Intel 4004 (est. CMOS 32 nm), no RAM * ~6 μm 2 ~120 μm 2 * without battery, sensors, converters, I/O transceivers, memory Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

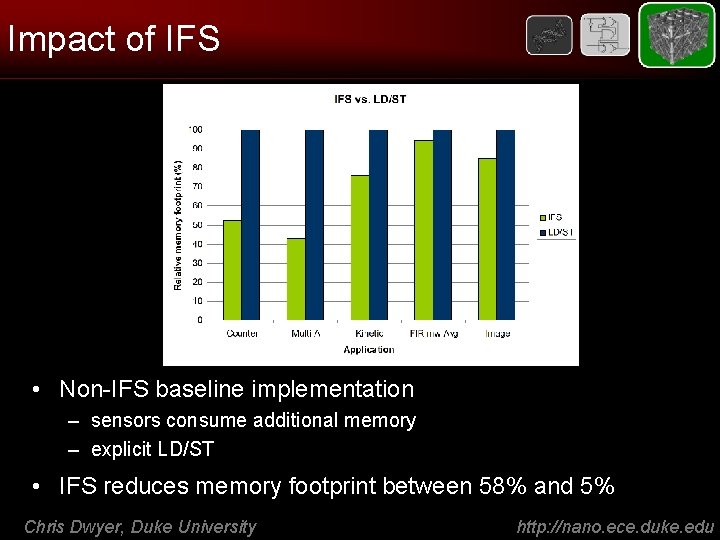

Impact of IFS • Non-IFS baseline implementation – sensors consume additional memory – explicit LD/ST • IFS reduces memory footprint between 58% and 5% Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

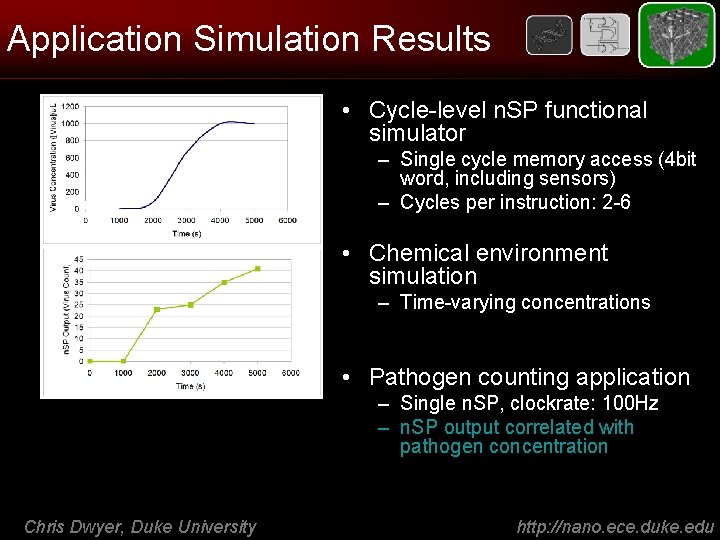

Application Simulation Results • Cycle-level n. SP functional simulator – Single cycle memory access (4 bit word, including sensors) – Cycles per instruction: 2 -6 • Chemical environment simulation – Time-varying concentrations • Pathogen counting application – Single n. SP, clockrate: 100 Hz – n. SP output correlated with pathogen concentration Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

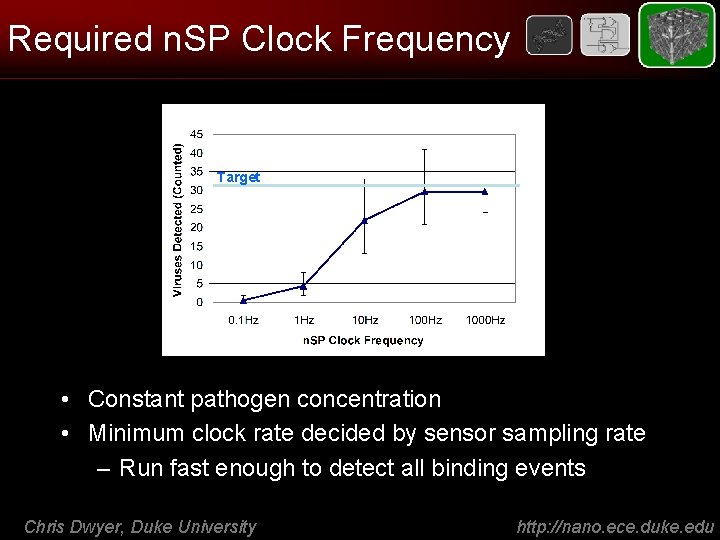

Required n. SP Clock Frequency Target • Constant pathogen concentration • Minimum clock rate decided by sensor sampling rate – Run fast enough to detect all binding events Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

Wrap-up • Self-assembled Nanostructures – DNA – Scaffolds • Devices – Fluorescence Resonance Energy Pathways and Logic • Self-assembled Systems – Fusing Logic and Sensors – Diffusion-limited Computation • Conclusions Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

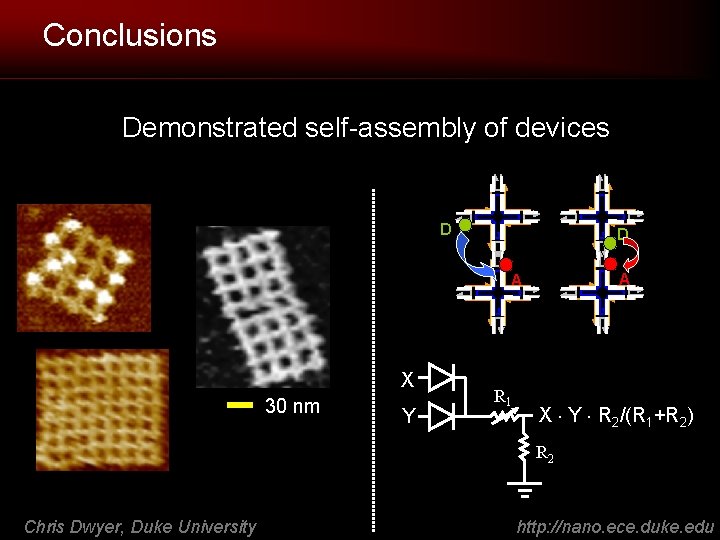

Conclusions Demonstrated self-assembly of devices D D A A X 30 nm Y R 1 X Y R 2/(R 1+R 2) R 2 Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

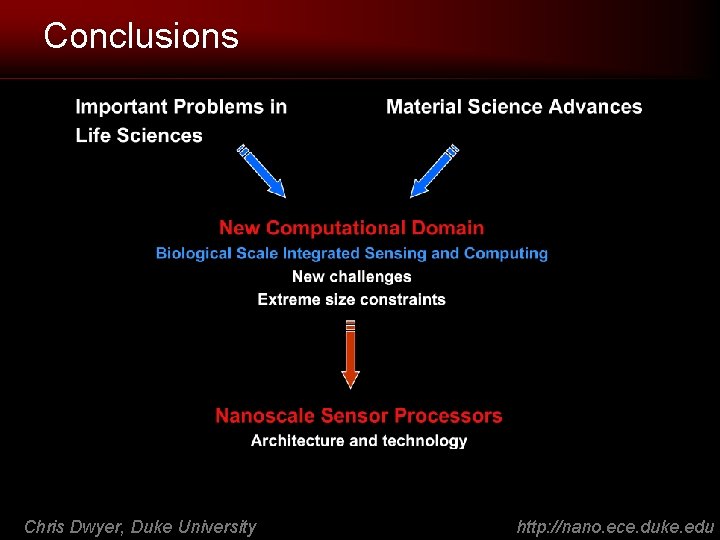

Conclusions Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

DNA-based Spatial Computing: Toward Diffusion-limited Computation Chris Dwyer Assistant Professor Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Department of Computer Science Spatial Computing Workshop / SASO, September 2009 Chris Dwyer, Duke University http: //nano. ece. duke. edu

- Slides: 43