DISTRIBUTION OF MOMENTS IN SLABS 3 DISTRIBUTION OF

DISTRIBUTION OF MOMENTS IN SLABS 3

DISTRIBUTION OF MOMENTS IN SLABS The total moment Mo that is resisted by a slab equals the sum of the maximum positive and negative moments in the span. It is the same as the total moment that occurs in a simply supported beam. For a uniform load it is as follows: In this expression l 1 is the span length, center to center, of supports in the direction in which moments are being taken and l 2 is the length of the span transverse to l 1, measured center to center of the supports. 4

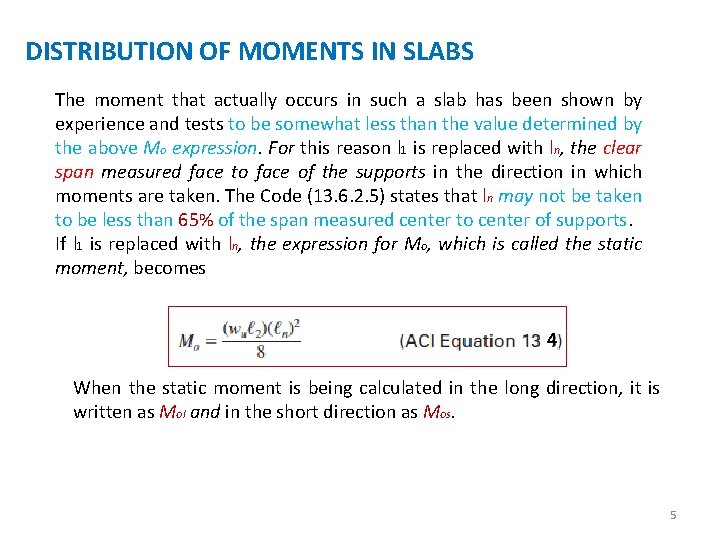

DISTRIBUTION OF MOMENTS IN SLABS The moment that actually occurs in such a slab has been shown by experience and tests to be somewhat less than the value determined by the above Mo expression. For this reason l 1 is replaced with ln, the clear span measured face to face of the supports in the direction in which moments are taken. The Code (13. 6. 2. 5) states that ln may not be taken to be less than 65% of the span measured center to center of supports. If l 1 is replaced with ln, the expression for Mo, which is called the static moment, becomes 4 When the static moment is being calculated in the long direction, it is written as Mol and in the short direction as Mos. 5

DISTRIBUTION OF MOMENTS IN SLABS It is necessary to know what proportions of these total moments are positive and what proportions are negative. If a slab was completely fixed at the end of each panel, the division would be as it is in a fixedend beam, two-thirds negative and one-third positive, as shown in next figure. This division is reasonably accurate for interior panels where the slab is continuous for several spans in each direction with equal span lengths and loads. In effect, the rotation of the interior columns is assumed to be small, and moment values of 0. 65 Mo for negative moment and 0. 35 Mo for positive moment are specified by the Code (13. 6. 3. 2). For cases where the span lengths and loadings are different, the proportion of positive and negative moments may vary appreciably, and the use of a more detailed method of analysis is desirable. 6

DISTRIBUTION OF MOMENTS IN SLABS The relative stiffness’s of the columns and slabs of exterior panels are of far greater significance in their effect on the moments than is the case for interior panels. The magnitudes of the moments are very sensitive to the amount of torsional restraint supplied at the discontinuous edges. This restraint is provided both by the flexural stiffness of the slab and by the flexural stiffness of the exterior column. 7

DISTRIBUTION OF MOMENTS IN SLABS Should the stiffness of an exterior column be quite small, the end negative moment will be very close to zero. If the stiffness of the exterior column is very large, the positive and negative moments will still not be the same as those in an interior panel unless an edge beam with a very large torsional stiffness is provided that will substantially prevent rotation of the discontinuous edge of the slab. If a 2 -ft-wide beam were to be framed into a 2 -ft-wide column of infinite flexural stiffness in the plane of the beam, the joint would behave as would a perfectly fixed end, and the negative beam moment would equal the fixed-end moment. 8

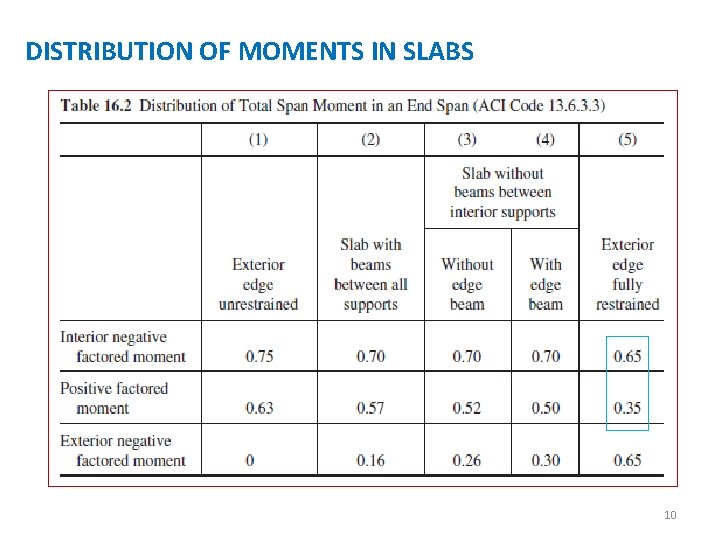

DISTRIBUTION OF MOMENTS IN SLABS If a two-way slab 24 ft wide were to be framed into this same 2 -ft-wide column of infinite stiffness, the situation of no rotation would occur along the part of the slab at the column. For the remaining 11 -ft widths of slab on each side of the column, there would be rotation varying from zero at the side face of the column to maximums 11 ft on each side of the column. As a result of this rotation, the negative moment at the face of the column would be less than the fixed-end moment. Thus the stiffness of the exterior column is reduced by the rotation of the attached transverse slab. To take into account the fact that the rotation of the edge of the slab is different at different distances from the column, the exterior columns and slab edge beam are replaced with an equivalent column that has the same estimated flexibility as the column plus the edge beam. It can be seen that this is quite an involved process; therefore, instead of requiring a complicated analysis, the Code (13. 6. 3. 3) provides a set of percentages for dividing the total factored static moment into its positive and negative parts in an end span. 9

DISTRIBUTION OF MOMENTS IN SLABS 10

DISTRIBUTION OF MOMENTS IN SLABS These divisions, which are shown in the last table, include values for unrestrained edges (where the slab is simply supported on a masonry or concrete wall) and for restrained edges (where the slab is constructed integrally with a very stiff reinforced concrete wall so that the little rotation occurs at the slab-to-wall connection). In next figure the distribution of the total factored moment for the interior and exterior spans of a flat-plate structure is shown. The plate is assumed to be constructed without beams between interior supports and without edge beams. 11

DISTRIBUTION OF MOMENTS IN SLABS

DISTRIBUTION OF MOMENTS IN SLABS The next problem is to estimate what proportion of these moments is taken by the column strips and what proportion is taken by the middle strips. For this discussion a flat plate structure is assumed, and the moment resisted by the column strip is estimated by considering the tributary areas as shown. 13

DISTRIBUTION OF MOMENTS IN SLABS If you sketch in the approximate deflected shape of a panel, you will see that a larger portion of the positive moment is carried by the middle strip than by the column strip, and vice versa for the negative moments. As a result, about 60% of the positive Mo and about 70% of the negative Mo are expected to be resisted by the column strip. 14

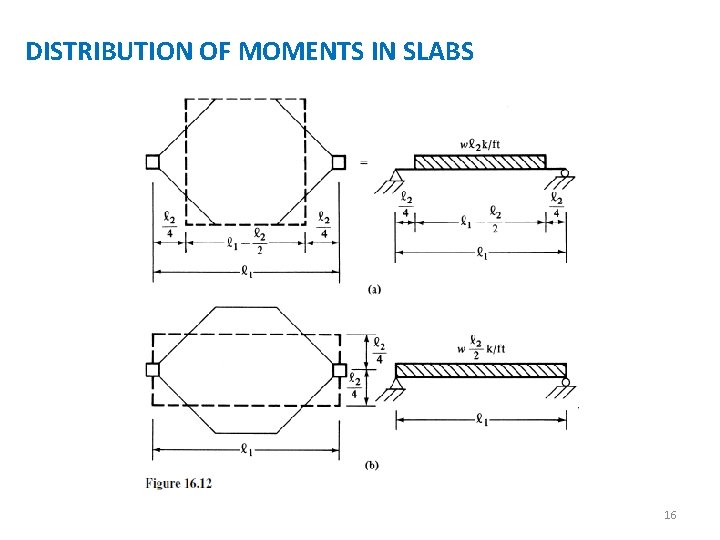

DISTRIBUTION OF MOMENTS IN SLABS To simplify the mathematics, the load to be supported is assumed to fall within the dashed lines shown in either part (a) or (b) of the next figure. The corresponding load is placed on the simple span, and its centerline moment is determined as an estimate of the portion of the static moment taken by the column strip. In Figure 16. 12(a), the load is spread uniformly over a length near the mid -span of the beam, thus causing the moment to be overestimated a little, while in Figure 16. 12(b) the load is spread uniformly from end to end, causing the moment to be underestimated. Based on these approximations, the estimated moments in the column strips for square panels will vary from 0. 5 Mo to 0. 75 Mo, where Mo = the absolute sum of the positive and average negative factored moments in each direction =. As l 1 becomes larger than l 2, the column strip takes a larger proportion of the moment. For such cases, about 60– 70% of Mo will be resisted by the column strip. 15

DISTRIBUTION OF MOMENTS IN SLABS 16

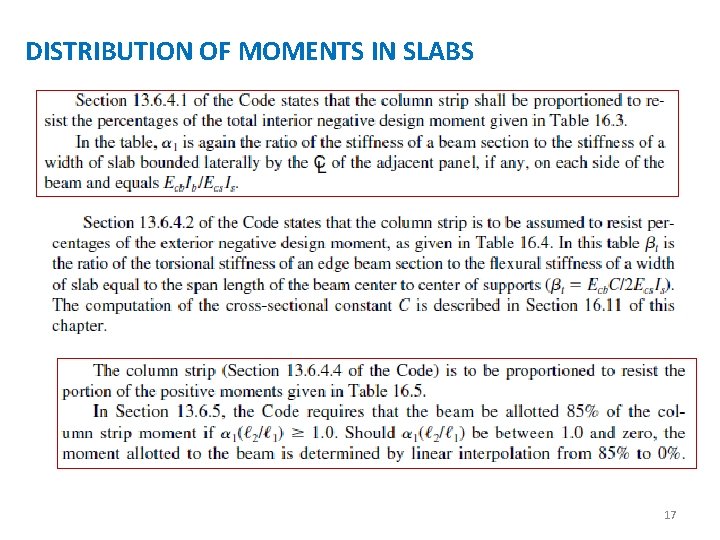

DISTRIBUTION OF MOMENTS IN SLABS 17

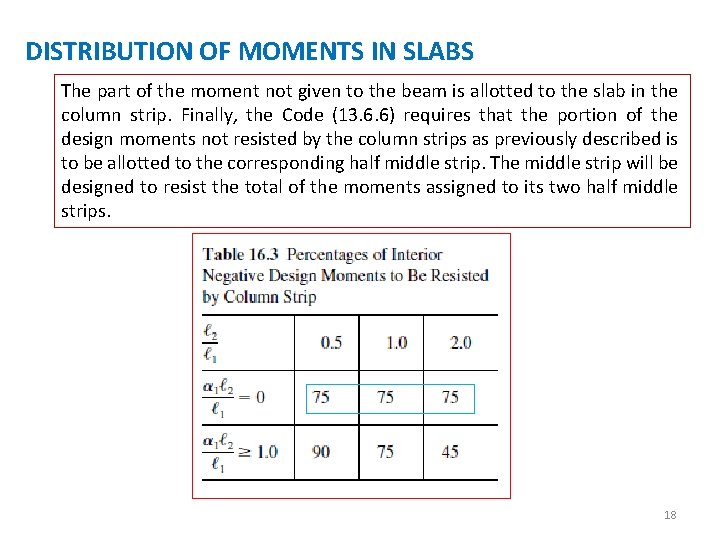

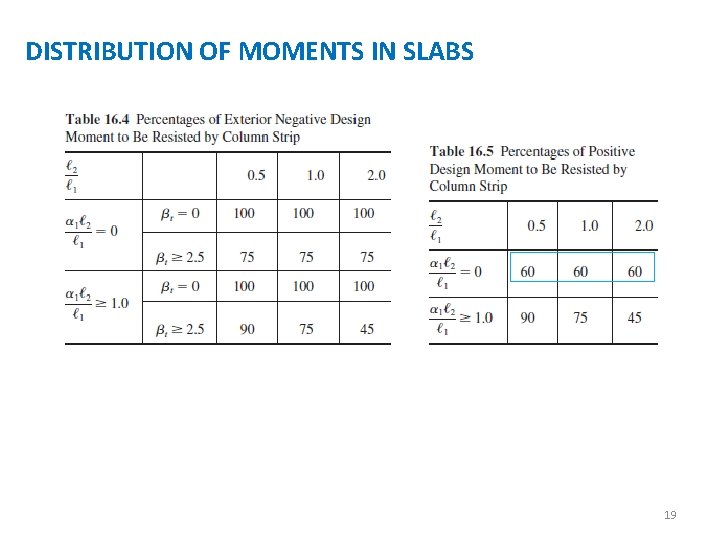

DISTRIBUTION OF MOMENTS IN SLABS The part of the moment not given to the beam is allotted to the slab in the column strip. Finally, the Code (13. 6. 6) requires that the portion of the design moments not resisted by the column strips as previously described is to be allotted to the corresponding half middle strip. The middle strip will be designed to resist the total of the moments assigned to its two half middle strips. 18

DISTRIBUTION OF MOMENTS IN SLABS 19

DESIGN OF AN INTERIOR FLAT PLATE 20

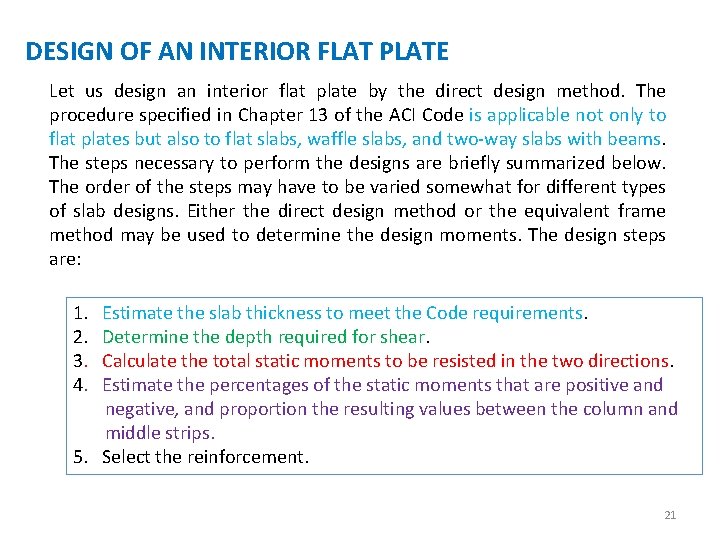

DESIGN OF AN INTERIOR FLAT PLATE Let us design an interior flat plate by the direct design method. The procedure specified in Chapter 13 of the ACI Code is applicable not only to flat plates but also to flat slabs, waffle slabs, and two-way slabs with beams. The steps necessary to perform the designs are briefly summarized below. The order of the steps may have to be varied somewhat for different types of slab designs. Either the direct design method or the equivalent frame method may be used to determine the design moments. The design steps are: 1. 2. 3. 4. Estimate the slab thickness to meet the Code requirements. Determine the depth required for shear. Calculate the total static moments to be resisted in the two directions. Estimate the percentages of the static moments that are positive and negative, and proportion the resulting values between the column and middle strips. 5. Select the reinforcement. 21

DESIGN OF AN INTERIOR FLAT PLATE Example 16. 3 SOLUTION 22

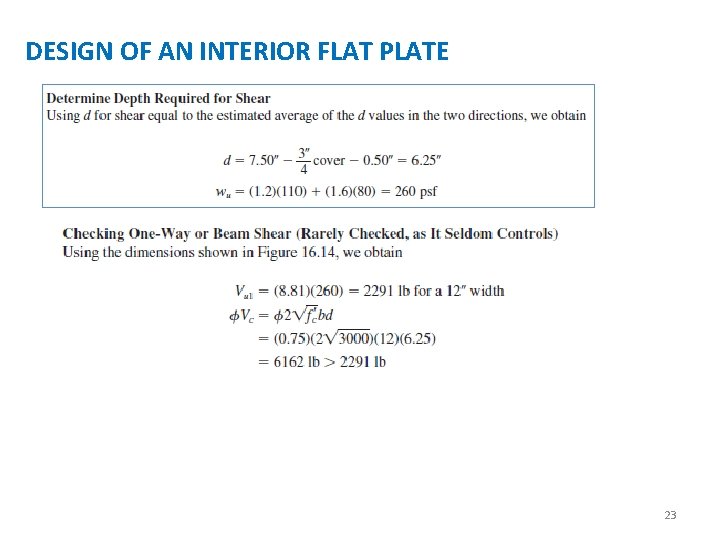

DESIGN OF AN INTERIOR FLAT PLATE 23

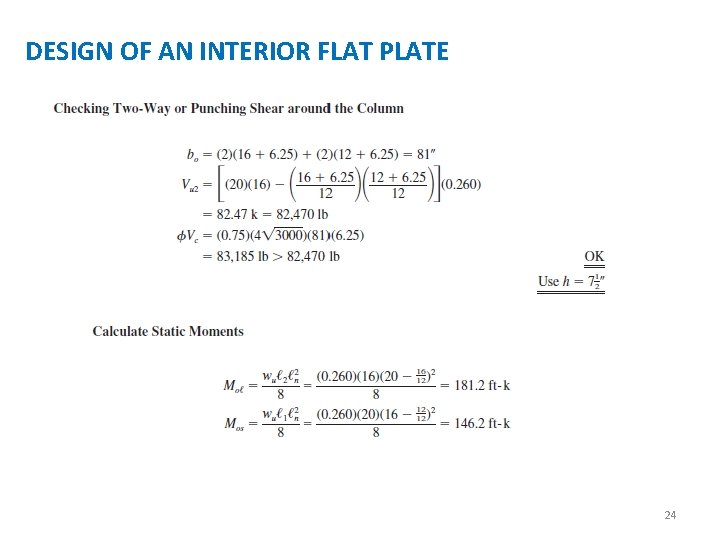

DESIGN OF AN INTERIOR FLAT PLATE 24

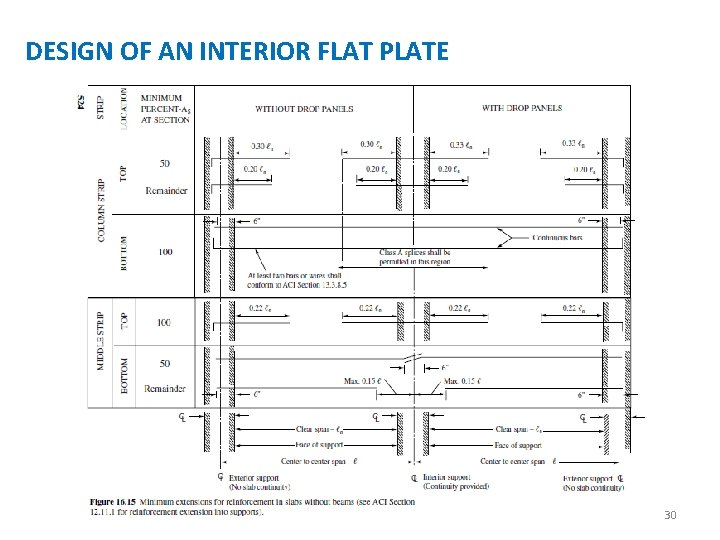

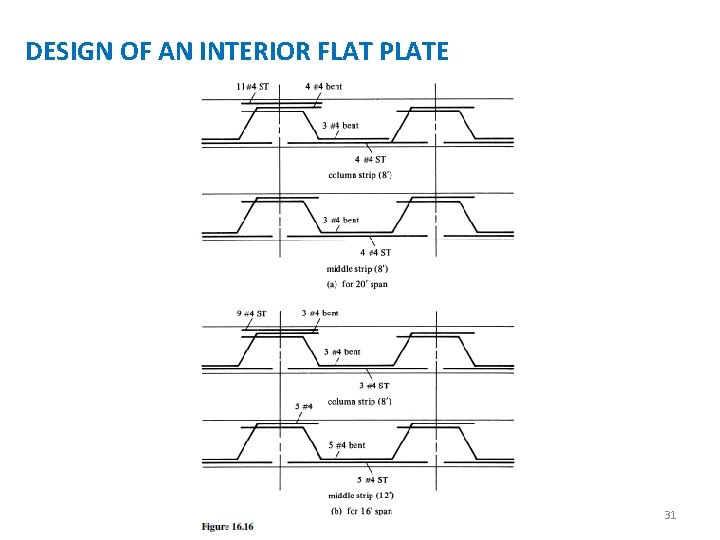

DESIGN OF AN INTERIOR FLAT PLATE Actually, the temperature percentage includes bars in the top and bottom of the slab. In the negative moment region, some of the positive steel bars have been extended into the support region and are also available for temperature and shrinkage steel. If desirable, these positive bars can be lapped instead of being stopped in the support. The selection of the reinforcing bars is the final step taken in the design of this flat plate. The Code Figure 13. 3. 8 (given as Figure 16. 15 here) shows the minimum lengths of slab reinforcing bars for flat plates and for flat slabs with drop panels. This figure shows that some of the positive reinforcing must be run into the support area. The bars selected for this flat plate are shown in Figure 16. Bent bars are used in this example, but straight bars could have been used just as well. There seems to be a trend among designers in the direction of using more straight bars in slabs and fewer bent bars. 25

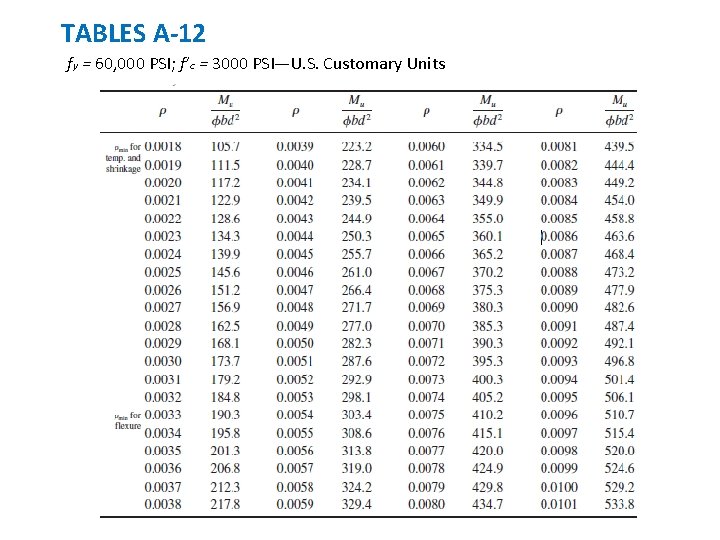

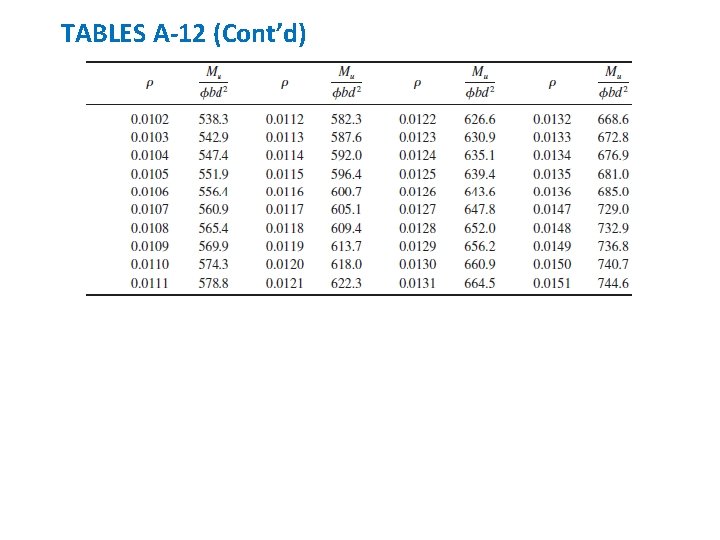

TABLES A-12 fy = 60, 000 PSI; f’c = 3000 PSI—U. S. Customary Units

TABLES A-12 (Cont’d)

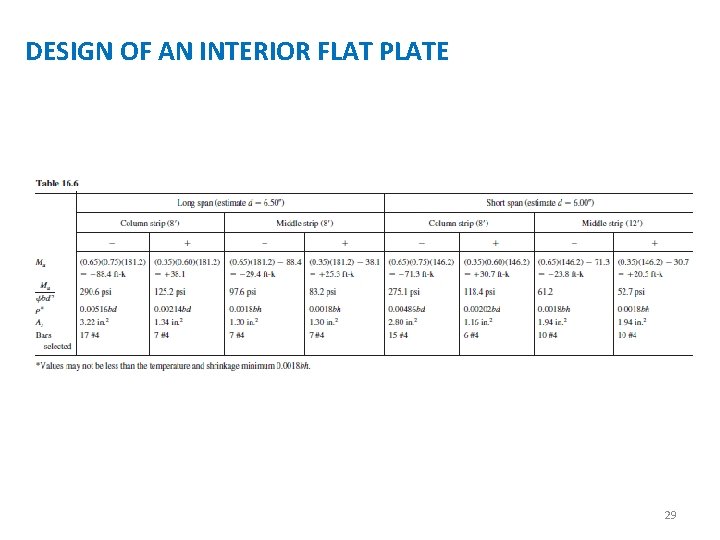

DESIGN OF AN INTERIOR FLAT PLATE 29

DESIGN OF AN INTERIOR FLAT PLATE 30

DESIGN OF AN INTERIOR FLAT PLATE 31

PLACING OF LIVE LOADS 32

PLACING OF LIVE LOADS The moments in a continuous floor slab are appreciably affected by different positions or patterns of the live loads. The usual procedure, however, is to calculate the total static moments, assuming that all panels are subjected to full live load. When different loading patterns are used, the moments can be changed so much that overstressing may occur in the slab. Section 13. 7. 6. 2 of the Code states that if a variable live load does not exceed three fourths of the dead load, or if it is of a type such that all panels will be loaded simultaneously, it is permissible to assume that full live load placed over the entire area will cause maximum moment values throughout the entire slab system. For other loading conditions it may be assumed (according to ACI Section 13. 7. 6. 3) that maximum positive moment at the mid-span of a panel will occur when three-fourths of the full factored live load is placed on the panel in question and on alternate spans. It may be further assumed that the maximum negative moment at a support will occur when threefourths of the full factored live load is placed only on the adjacent spans. 33

PLACING OF LIVE LOADS The Code permits the use of the three-fourths factor because the absolute maximum positive and negative moments cannot occur simultaneously under a single loading condition and also because some redistribution of moments is possible before failure will occur. Although some local overstress may be the result of this procedure, it is felt that the ultimate capacity of the system after redistribution will be sufficient to resist the full factored dead and live loads in every panel. The moment determined as described in the last paragraph may not be less than moments obtained when full factored live loads are placed in every panel (ACI 13. 7. 6. 4). 34

OPENINGS IN SLAB SYSTEMS 35

OPENINGS IN SLAB SYSTEMS According to the Code (13. 4), openings can be used in slab systems if adequate strength is provided and if all serviceability conditions of the ACI, including deflections, are met. 1. If openings are located in the area common to intersecting middle strips, it will be necessary to provide the same total amount of reinforcing in the slab that would have been there without the opening. 2. For openings in intersecting column strips, the width of the openings may not be more than one-eighth the width of the column strip in either span. An amount of reinforcing equal to that interrupted by the opening must be placed on the sides of the opening. 3. Openings in an area common to one column strip and one middle strip may not interrupt more than one-fourth of the reinforcing in either strip. An amount of reinforcing equal to that interrupted shall be placed around the sides of the opening. 4. The shear requirements of Section 11. 12. 5 of the Code must be met. 36

- Slides: 33