Distributed Systems Atomicity Decision Making Faults Snapshots Slides

Distributed Systems: Atomicity, Decision Making, Faults, Snapshots Slides adapted from Ken's CS 514 lectures

Announcements • Prelim II coming up next week: – – In class, Thursday, November 20 th, 10: 10— 11: 25 pm 203 Thurston Closed book, no calculators/PDAs/… Bring ID • Topics: – Everything after first prelim – Lectures 14 -22, chapters 10 -15 (8 th ed) • Review Session Tonight, November 18 th, 6: 30 pm– 7: 30 pm – Location: 315 Upson Hall 2

Review: What time is it? • In distributed system we need practical ways to deal with time – E. g. we may need to agree that update A occurred before update B – Or offer a “lease” on a resource that expires at time 10: 10. 0150 – Or guarantee that a time critical event will reach all interested parties within 100 ms 3

Review: Event Ordering • Problem: distributed systems do not share a clock – Many coordination problems would be simplified if they did (“first one wins”) • Distributed systems do have some sense of time – Events in a single process happen in order – Messages between processes must be sent before they can be received – How helpful is this? 4

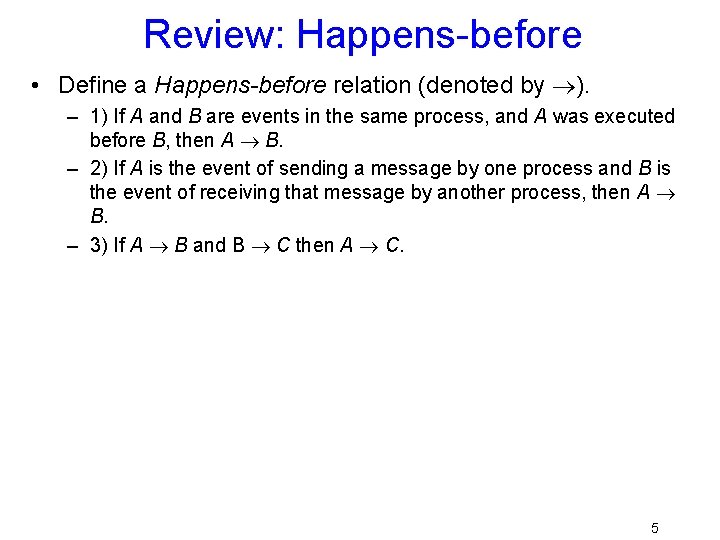

Review: Happens-before • Define a Happens-before relation (denoted by ). – 1) If A and B are events in the same process, and A was executed before B, then A B. – 2) If A is the event of sending a message by one process and B is the event of receiving that message by another process, then A B. – 3) If A B and B C then A C. 5

Review: Total ordering? • Happens-before gives a partial ordering of events • We still do not have a total ordering of events – We are not able to order events that happen concurrently • Concurrent if (not A B) and (not B A) 6

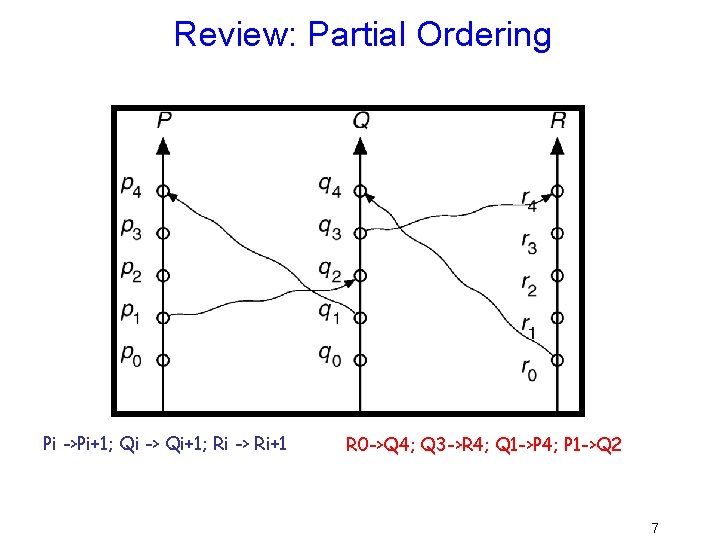

Review: Partial Ordering Pi ->Pi+1; Qi -> Qi+1; Ri -> Ri+1 R 0 ->Q 4; Q 3 ->R 4; Q 1 ->P 4; P 1 ->Q 2 7

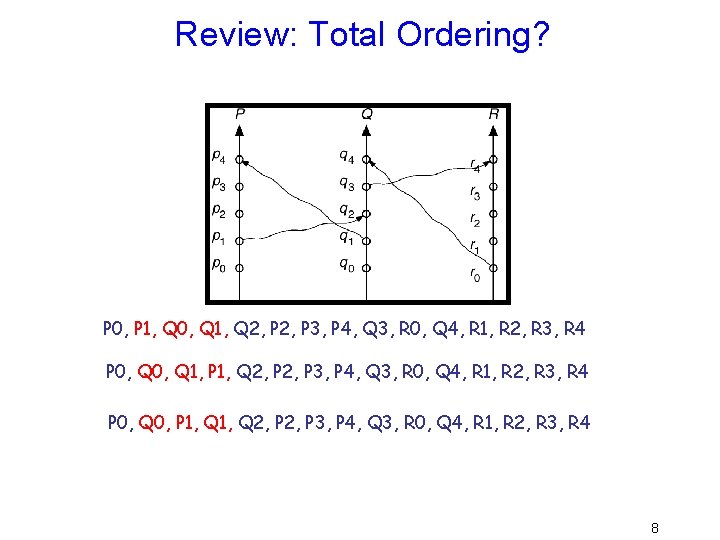

Review: Total Ordering? P 0, P 1, Q 0, Q 1, Q 2, P 3, P 4, Q 3, R 0, Q 4, R 1, R 2, R 3, R 4 P 0, Q 1, P 1, Q 2, P 3, P 4, Q 3, R 0, Q 4, R 1, R 2, R 3, R 4 P 0, Q 0, P 1, Q 2, P 3, P 4, Q 3, R 0, Q 4, R 1, R 2, R 3, R 4 8

Review: Timestamps • Assume each process has a local logical clock that ticks once per event and that the processes are numbered – Clocks tick once per event (including message send) – When send a message, send your clock value – When receive a message, set your clock to MAX( your clock, timestamp of message + 1) • Thus sending comes before receiving • Only visibility into actions at other nodes happens during communication, communicate synchronizes the clocks – If the timestamps of two events A and B are the same, then use the process identity numbers to break ties. • This gives a total ordering! 9

Review: Distributed Mutual Exclusion • Want mutual exclusion in distributed setting – The system consists of n processes; each process Pi resides at a different processor – Each process has a critical section that requires mutual exclusion – Problem: Cannot use atomic test. And. Set primitive since memory not shared and processes may be on physically separated nodes • Requirement – If Pi is executing in its critical section, then no other process Pj is executing in its critical section • Compare three solutions • Centralized Distributed Mutual Exclusion (CDME) • Fully Distributed Mutual Exclusion (DDME) • Token passing 10

Today • Atomicity and Distributed Decision Making • Faults in distributed systems • What time is it now? – Synchronized clocks • What does the entire system look like at this moment? 11

Atomicity • Recall: – Atomicity = either all the operations associated with a program unit are executed to completion, or none are performed. • In a distributed system may have multiple copies of the data – (e. g. replicas are good for reliability/availability) • PROBLEM: How do we atomically update all of the copies? – That is, either all replicas reflect a change or none 12

E. g. Two-Phase Commit • Goal: Update all replicas atomically – Either everyone commits or everyone aborts – No inconsistencies even in face of failures – Caveat: Assume only crash or fail-stop failures • Crash: servers stop when they fail – do not continue and generate bad data • Fail-stop: in addition to crash, fail-stop failure is detectable. • Definitions – Coordinator: Software entity that shepherds the process (in our example could be one of the servers) – Ready to commit: side effects of update safely stored on non-volatile storage • Even if crash, once I say I am ready to commit then a recover procedure will find evidence and continue with commit protocol 13

Two Phase Commit: Phase 1 • Coordinator send a PREPARE message to each replica • Coordinator waits for all replicas to reply with a vote • Each participant replies with a vote – Votes PREPARED if ready to commit and locks data items being updated – Votes NO if unable to get a lock or unable to ensure ready to commit 14

Two Phase Commit: Phase 2 • If coordinator receives PREPARED vote from all replicas then it may decide to commit or abort • Coordinator send its decision to all participants • If participant receives COMMIT decision then commit changes resulting from update • If participant received ABORT decision then discard changes resulting from update • Participant replies DONE • When Coordinator received DONE from all participants then can delete record of outcome 15

Performance • In absence of failure, 2 PC (two-phase-commit) makes a total of 2 (1. 5? ) round trips of messages before decision is made – – Prepare Vote NO or PREPARE Commit/abort Done (but done just for bookkeeping, does not affect response time) 16

Failure Handling in 2 PC – Replica Failure • The log contains a <commit T> record. – In this case, the site executes redo(T). • The log contains an <abort T> record. – In this case, the site executes undo(T). • The log contains a <ready T> record – In this case consult coordinator Ci. • If Ci is down, site sends query-status T message to the other sites. • The log contains no control records concerning T. – In this case, the site executes undo(T). 17

Failure Handling in 2 PC – Coordinator Ci Failure • If an active site contains a <commit T> record in its log, then T must be committed. • If an active site contains an <abort T> record in its log, then T must be aborted. • If some active site does not contain the record <ready T> in its log then the failed coordinator Ci cannot have decided to commit T. Rather than wait for Ci to recover, it is preferable to abort T. • All active sites have a <ready T> record in their logs, but no additional control records. In this case we must wait for the coordinator to recover. – Blocking problem – T is blocked pending the recovery of site Si. 18

Failure Handling • • Failure detected with timeouts If participant times out before getting a PREPARE can abort If coordinator times out waiting for a vote can abort If a participant times out waiting for a decision it is blocked! – Wait for Coordinator to recover? – Punt to some other resolution protocol • If a coordinator times out waiting for done, keep record of outcome • other sites may have a replica. 19

Failures in distributed systems • We may want to avoid relying on a single server/coordinator/boss to make progress • Thus want the decision making to be distributed among the participants (“all nodes created equal”) => the “consensus problem” in distributed systems. • However depending on what we can assume about the network, it may be impossible to reach a decision in some cases! 20

Impossibility of Consensus • Network characteristics: – Synchronous - some upper bound on network/processing delay. – Asynchronous - no upper bound on network/processing delay. • Fischer Lynch and Paterson showed: – With even just one failure possible, you cannot guarantee consensus. • Cannot guarantee consensus process will terminate • Assumes asynchronous network – Essence of proof: Just before a decision is reached, we can delay a node slightly too long to reach a decision. • But we still want to do it. . Right? 21

Distributed Decision Making Discussion • Why is distributed decision making desirable? – Fault Tolerance! Also, atomicity in distributed system. – A group of machines can come to a decision even if one or more of them fail during the process – After decision made, result recorded in multiple places • Undesirable if algorithm is blocking (e. g. two-phase commit) – One machine can be stalled until another site recovers: – A blocked site holds resources (locks on updated items, pages pinned in memory, etc) until learns fate of update • To reduce blocking – add more rounds (e. g. three-phase commit) – Add more replicas than needed (e. g. quorums) • What happens if one or more of the nodes is malicious? – Malicious: attempting to compromise the decision making • Known as Byzantine fault tolerance. More on this next time 22

Faults 23

Categories of failures • Crash faults, message loss – These are common in real systems – Crash failures: process simply stops, and does nothing wrong that would be externally visible before it stops • These faults can’t be directly detected 24

Categories of failures • Fail-stop failures – These require system support – Idea is that the process fails by crashing, and the system notifies anyone who was talking to it – With fail-stop failures we can overcome message loss by just resending packets, which must be uniquely numbered – Easy to work with… but rarely supported 25

Categories of failures • Non-malicious Byzantine failures – This is the best way to understand many kinds of corruption and buggy behaviors – Program can do pretty much anything, including sending corrupted messages – But it doesn’t do so with the intention of screwing up our protocols • Unfortunately, a pretty common mode of failure 26

Categories of failure • Malicious, true Byzantine, failures – Model is of an attacker who has studied the system and wants to break it – She can corrupt or replay messages, intercept them at will, compromise programs and substitute hacked versions • This is a worst-case scenario mindset – In practice, doesn’t actually happen – Very costly to defend against; typically used in very limited ways (e. g. key mgt. server) 27

Models of failure • Question here concerns how failures appear in formal models used when proving things about protocols • Think back to Lamport’s happens-before relationship, – Model already has processes, messages, temporal ordering – Assumes messages are reliably delivered 28

Two kinds of models • We tend to work within two models – Asynchronous model makes no assumptions about time • Lamport’s model is a good fit • Processes have no clocks, will wait indefinitely for messages, could run arbitrarily fast/slow • Distributed computing at an “eons” timescale – Synchronous model assumes a lock-step execution in which processes share a clock 29

Adding failures in Lamport’s model • Also called the asynchronous model • Normally we just assume that a failed process “crashes: ” it stops doing anything – Notice that in this model, a failed process is indistinguishable from a delayed process – In fact, the decision that something has failed takes on an arbitrary flavor • Suppose that at point e in its execution, process p decides to treat q as faulty…. ” 30

What about the synchronous model? • Here, we also have processes and messages – But communication is usually assumed to be reliable: any message sent at time t is delivered by time t+ – Algorithms are often structured into rounds, each lasting some fixed amount of time , giving time for each process to communicate with every other process – In this model, a crash failure is easily detected • When people have considered malicious failures, they often used this model 31

Neither model is realistic • Value of the asynchronous model is that it is so stripped down and simple – If we can do something “well” in this model we can do at least as well in the real world – So we’ll want “best” solutions • Value of the synchronous model is that it adds a lot of “unrealistic” mechanism – If we can’t solve a problem with all this help, we probably can’t solve it in a more realistic setting! – So seek impossibility results 32

Fischer, Lynch and Patterson • Impossibility of Consensus • A surprising result – Impossibility of Asynchronous Distributed Consensus with a Single Faulty Process • They prove that no asynchronous algorithm for agreeing on a one-bit value can guarantee that it will terminate in the presence of crash faults – And this is true even if no crash actually occurs! – Proof constructs infinite non-terminating runs – Essence of proof: Just before a decision is reached, we can delay a node slightly too long to reach a decision. 33

Tougher failure models • We’ve focused on crash failures – In the synchronous model these look like a “farewell cruel world” message – Some call it the “failstop model”. A faulty process is viewed as first saying goodbye, then crashing • What about tougher kinds of failures? – Corrupted messages – Processes that don’t follow the algorithm – Malicious processes out to cause havoc? 34

Here the situation is much harder • Generally we need at least 3 f+1 processes in a system to tolerate f Byzantine failures – For example, to tolerate 1 failure we need 4 or more processes • We also need f+1 “rounds” • Let’s see why this happens 35

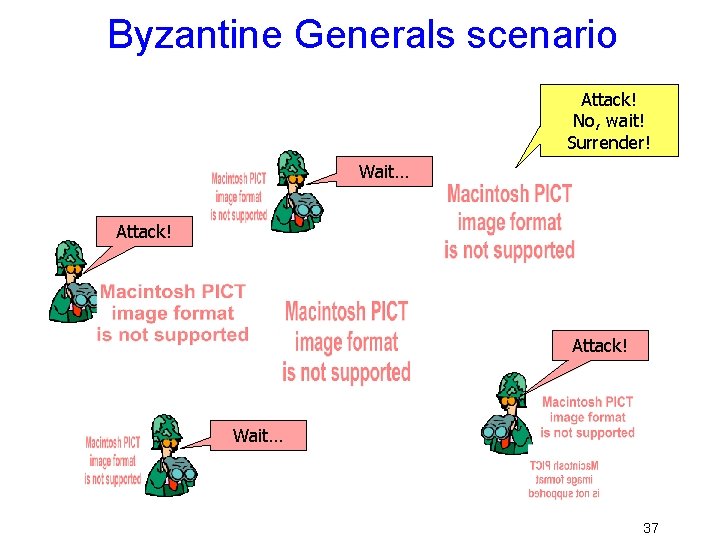

Byzantine Generals scenario • Generals (N of them) surround a city – They communicate by courier • Each has an opinion: “attack” or “wait” – In fact, an attack would succeed: the city will fall. – Waiting will succeed too: the city will surrender. – But if some attack and some wait, disaster ensues • Some Generals (f of them) are traitors… it doesn’t matter if they attack or wait, but we must prevent them from disrupting the battle – Traitor can’t forge messages from other Generals 36

Byzantine Generals scenario Attack! No, wait! Surrender! Wait… Attack! Wait… 37

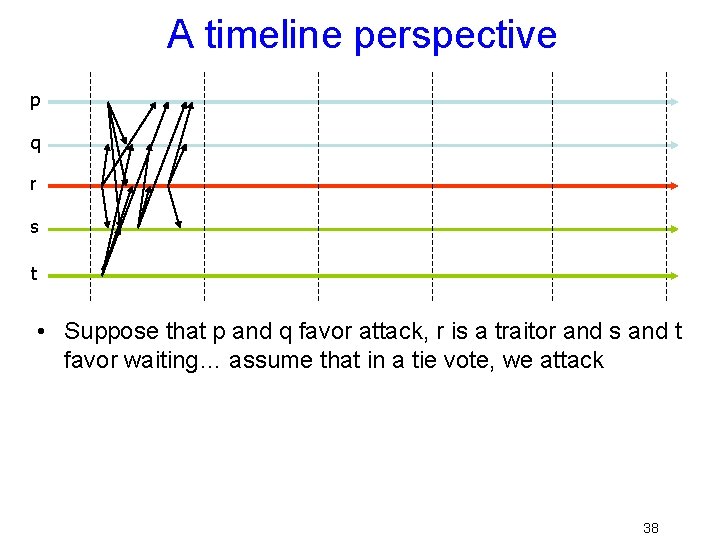

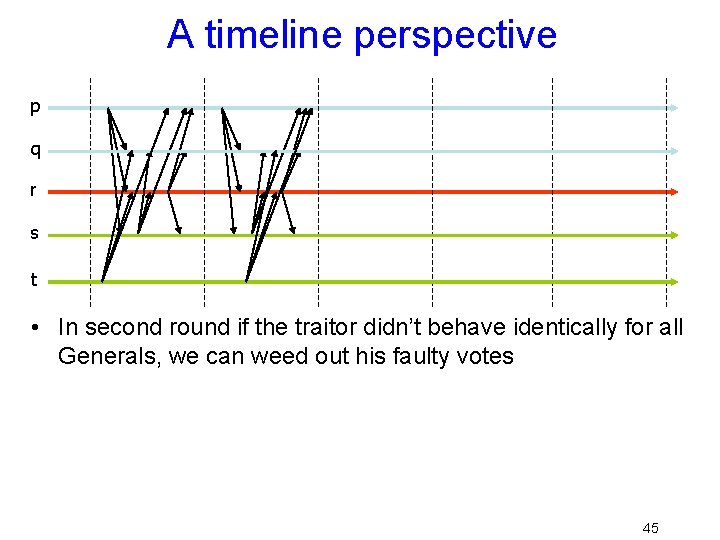

A timeline perspective p q r s t • Suppose that p and q favor attack, r is a traitor and s and t favor waiting… assume that in a tie vote, we attack 38

A timeline perspective p q r s t • After first round collected votes are: – {attack, wait, traitor’s-vote} 39

What can the traitor do? • Add a legitimate vote of “attack” – Anyone with 3 votes to attack knows the outcome • Add a legitimate vote of “wait” – Vote now favors “wait” • Or send different votes to different folks • Or don’t send a vote, at all, to some 40

Outcomes? • Traitor simply votes: – Either all see {a, a, a, w, w} – Or all see {a, a, w, w, w} • Traitor double-votes – Some see {a, a, a, w, w} and some {a, a, w, w, w} • Traitor withholds some vote(s) – Some see {a, a, w, w}, perhaps others see {a, a, a, w, w, } and still others see {a, a, w, w, w} • Notice that traitor can’t manipulate votes of loyal Generals! 41

What can we do? • Clearly we can’t decide yet; some loyal Generals might have contradictory data – Anyone with 4 votes can “decide” – But with 3 votes to “wait” or “attack, ” a General isn’t sure (one could be a traitor…) • So: in round 2, each sends out “witness” messages: here’s what I saw in round 1 – General Smith send me: “attack(signed) Smith” 42

Digital signatures • These require a cryptographic system – For example, RSA – Each player has a secret (private) key K-1 and a public key K. • She can publish her public key – RSA gives us a single “encrypt” function: • Encrypt(M, K), K-1) = Encrypt(M, K-1), K) = M • Encrypt a hash of the message to “sign” it 43

With such a system • A can send a message to B that only A could have sent – A just encrypts the body with her private key • … or one that only B can read – A encrypts it with B’s public key • Or can sign it as proof she sent it – B can recompute the signature and decrypt A’s hashed signature to see if they match • These capabilities limit what our traitor can do: he can’t forge or modify a message 44

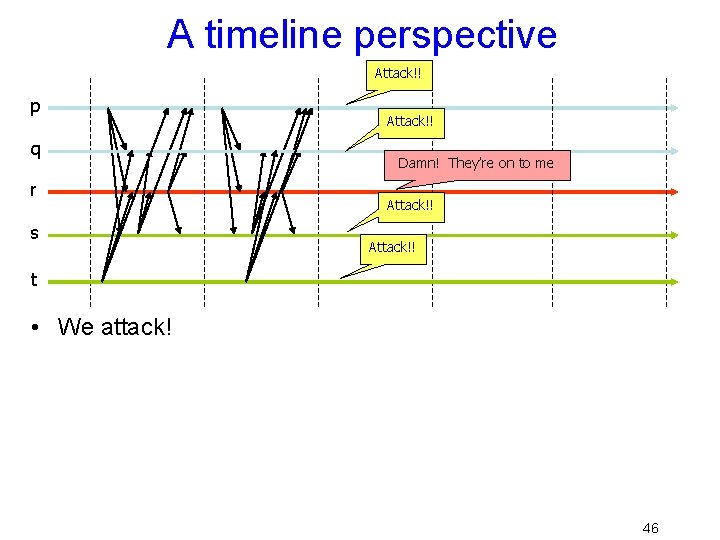

A timeline perspective p q r s t • In second round if the traitor didn’t behave identically for all Generals, we can weed out his faulty votes 45

A timeline perspective Attack!! p q r s Attack!! Damn! They’re on to me Attack!! t • We attack! 46

Traitor is stymied • Our loyal generals can deduce that the decision was to attack • Traitor can’t disrupt this… – Either forced to vote legitimately, or is caught – But costs were steep! • (f+1)*n 2 , messages! • Rounds can also be slow…. – “Early stopping” protocols: min(t+2, f+1) rounds; t is true number of faults 47

Distributed Snapshots 48

Introducing “wall clock time” • Back to the notion of time… • Distributed systems sometimes needs more precise notion of time other than happens-before • There are several options – Instead of network/process identitity to break ties… – “Extend” a logical clock with the clock time and use it to break ties • Makes meaningful statements like “B and D were concurrent, although B occurred first” • But unless clocks are closely synchronized such statements could be erroneous! – We use a clock synchronization algorithm to reconcile differences between clocks on various computers in the network 49

Synchronizing clocks • Without help, clocks will often differ by many milliseconds – Problem is that when a machine downloads time from a network clock it can’t be sure what the delay was – This is because the “uplink” and “downlink” delays are often very different in a network • Outright failures of clocks are rare… 50

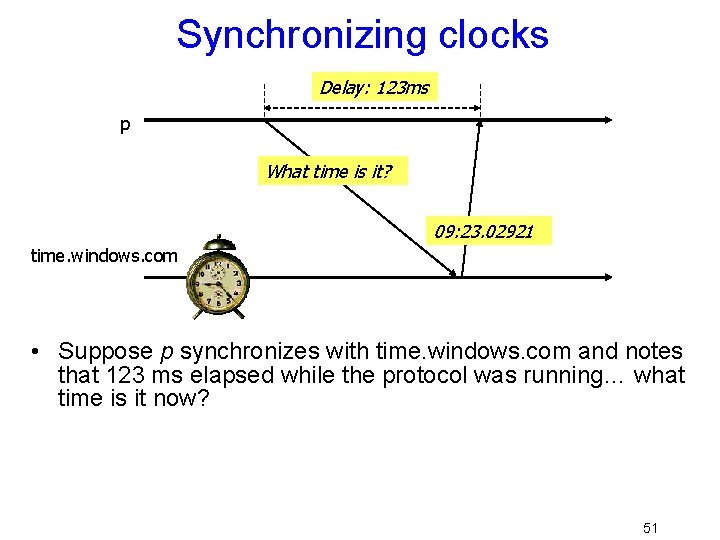

Synchronizing clocks Delay: 123 ms p What time is it? 09: 23. 02921 time. windows. com • Suppose p synchronizes with time. windows. com and notes that 123 ms elapsed while the protocol was running… what time is it now? 51

Synchronizing clocks • Options? – p could guess that the delay was evenly split, but this is rarely the case in WAN settings (downlink speeds are higher) – p could ignore the delay – p could factor in only “certain” delay, e. g. if we know that the link takes at least 5 ms in each direction. Works best with GPS time sources! • In general can’t do better than uncertainty in the link delay from the time source down to p 52

Consequences? • In a network of processes, we must assume that clocks are – Not perfectly synchronized. • We say that clocks are “inaccurate” – Even GPS has uncertainty, although small – And clocks can drift during periods between synchronizations • Relative drift between clocks is their “precision” 53

Temporal distortions • Things can be complicated because we can’t predict – Message delays (they vary constantly) – Execution speeds (often a process shares a machine with many other tasks) – Timing of external events • Lamport looked at this question too 54

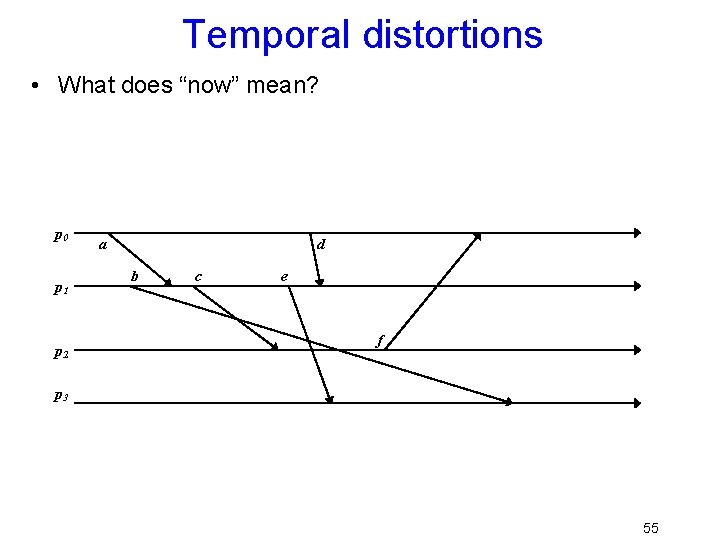

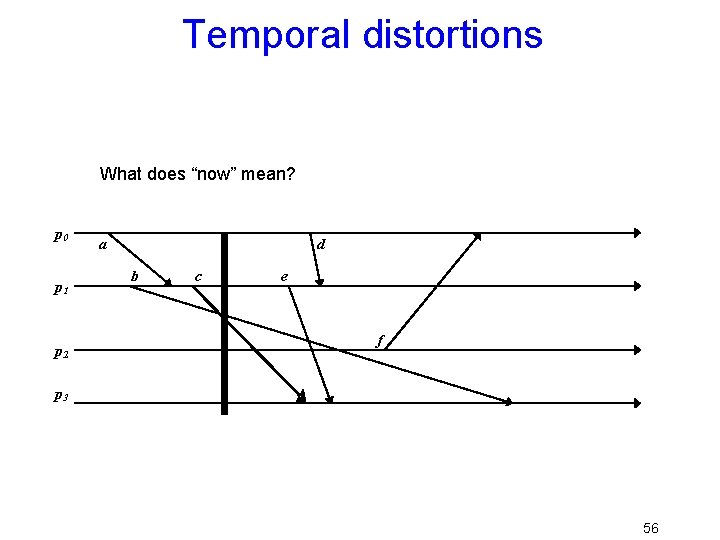

Temporal distortions • What does “now” mean? p 0 p 1 p 2 a d b c e f p 3 55

Temporal distortions What does “now” mean? p 0 p 1 p 2 a d b c e f p 3 56

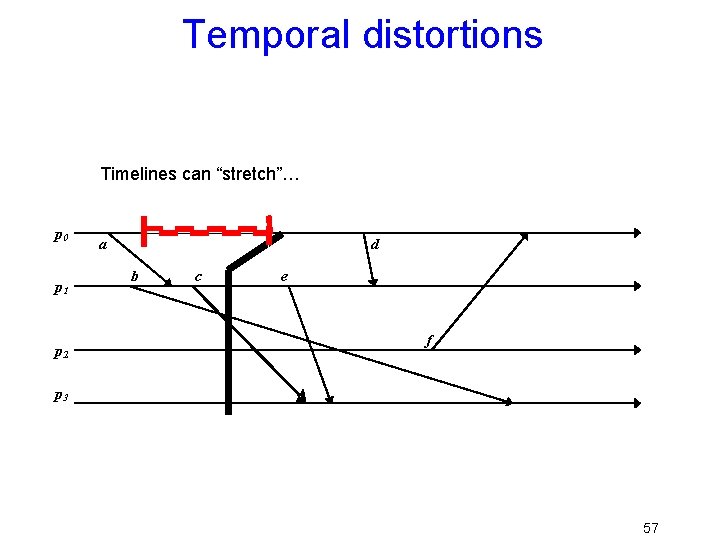

Temporal distortions Timelines can “stretch”… p 0 p 1 p 2 a d b c e … caused by scheduling effects, message delays, message loss… f p 3 57

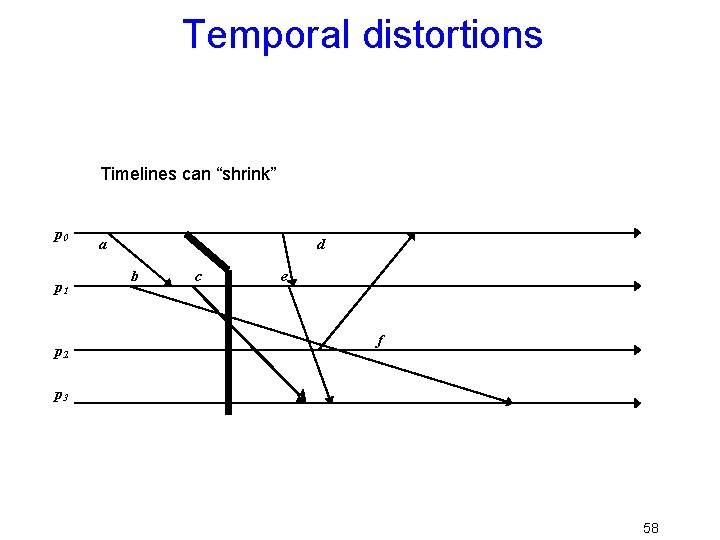

Temporal distortions Timelines can “shrink” p 0 p 1 p 2 a d b c e E. g. something lets a machine speed up f p 3 58

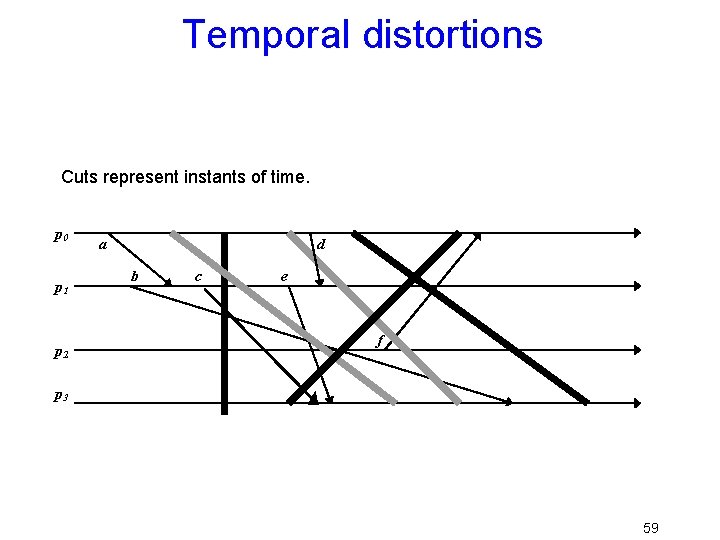

Temporal distortions Cuts represent instants of time. p 0 p 1 a d b c e But not every “cut” makes sense Black cuts could occur but not gray ones. p 2 f p 3 59

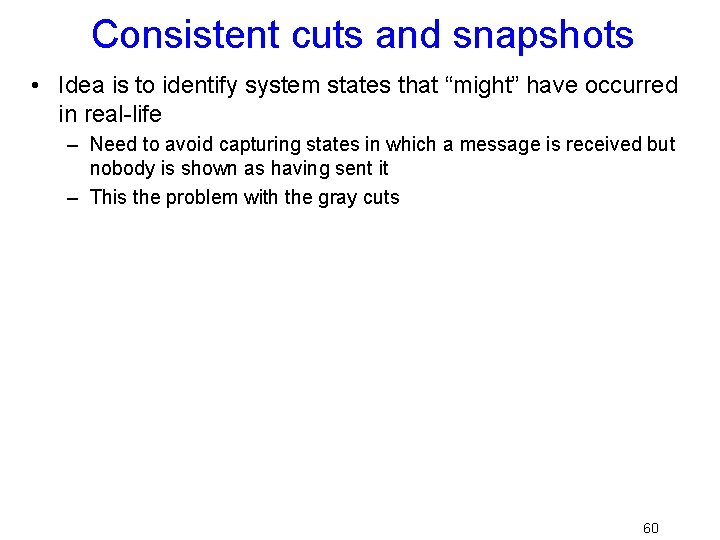

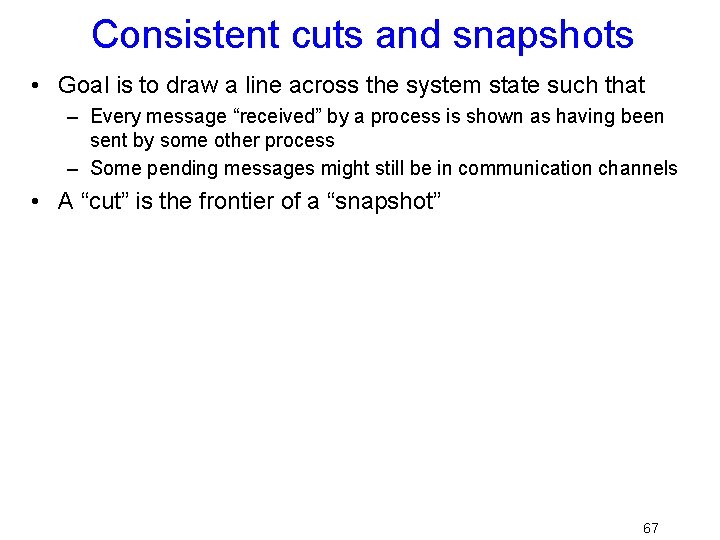

Consistent cuts and snapshots • Idea is to identify system states that “might” have occurred in real-life – Need to avoid capturing states in which a message is received but nobody is shown as having sent it – This the problem with the gray cuts 60

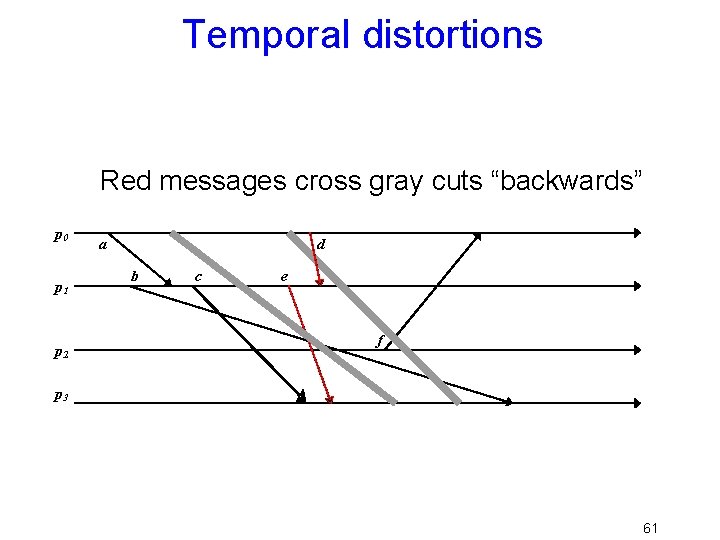

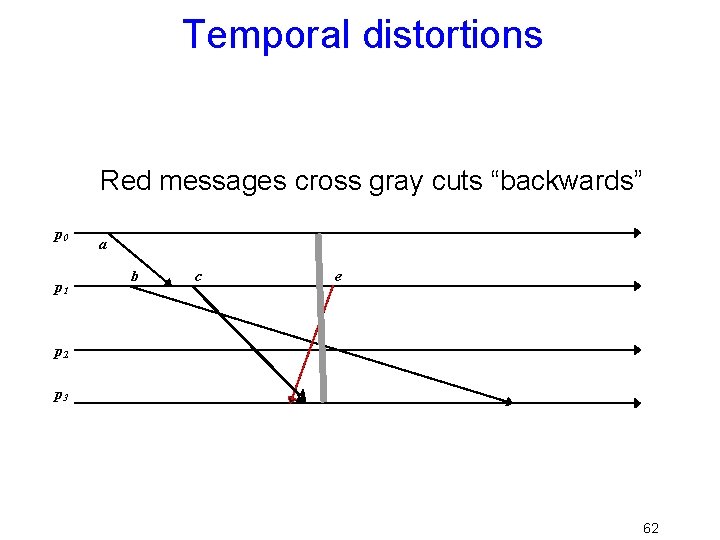

Temporal distortions Red messages cross gray cuts “backwards” p 0 p 1 p 2 a d b c e f p 3 61

Temporal distortions Red messages cross gray cuts “backwards” p 0 p 1 a b c e p 2 p 3 In a nutshell: the cut includes a message that “was never sent” 62

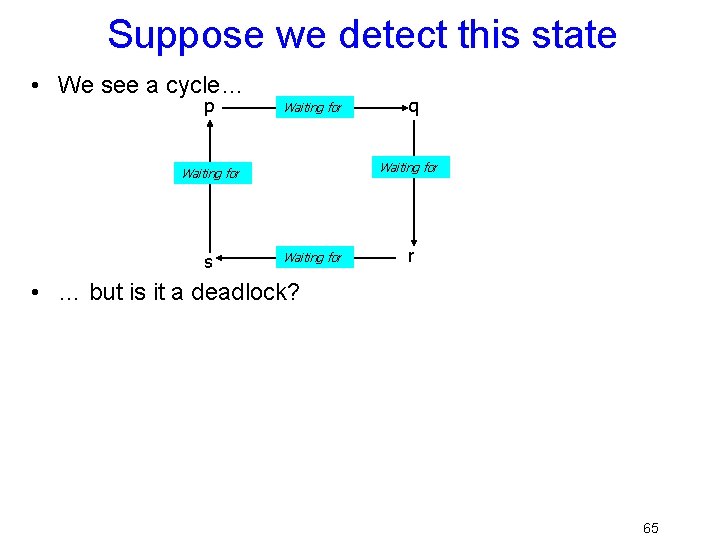

Who cares? • Suppose, for example, that we want to do distributed deadlock detection – System lets processes “wait” for actions by other processes – A process can only do one thing at a time – A deadlock occurs if there is a circular wait 63

Deadlock detection “algorithm” • p worries: perhaps we have a deadlock • p is waiting for q, so sends “what’s your state? ” • q, on receipt, is waiting for r, so sends the same question… and r for s…. And s is waiting on p. 64

Suppose we detect this state • We see a cycle… p Waiting for s q Waiting for r • … but is it a deadlock? 65

Phantom deadlocks! • Suppose system has a very high rate of locking. • Then perhaps a lock release message “passed” a query message – i. e. we see “q waiting for r” and “r waiting for s” but in fact, by the time we checked r, q was no longer waiting! • In effect: we checked for deadlock on a gray cut – an inconsistent cut. 66

Consistent cuts and snapshots • Goal is to draw a line across the system state such that – Every message “received” by a process is shown as having been sent by some other process – Some pending messages might still be in communication channels • A “cut” is the frontier of a “snapshot” 67

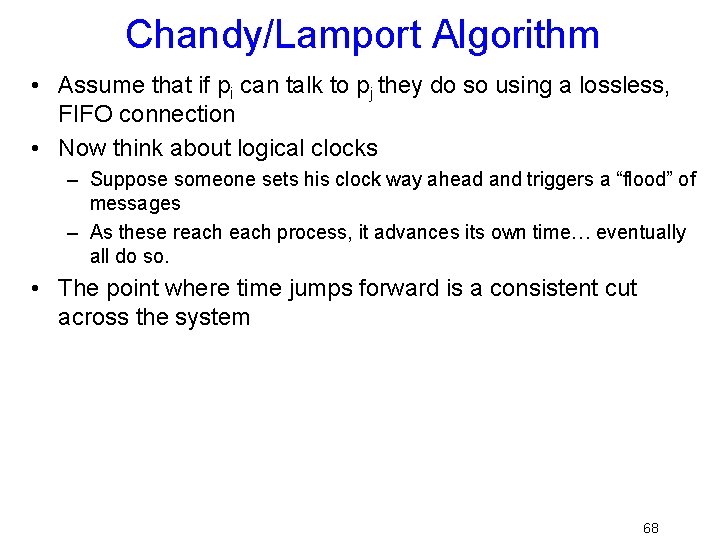

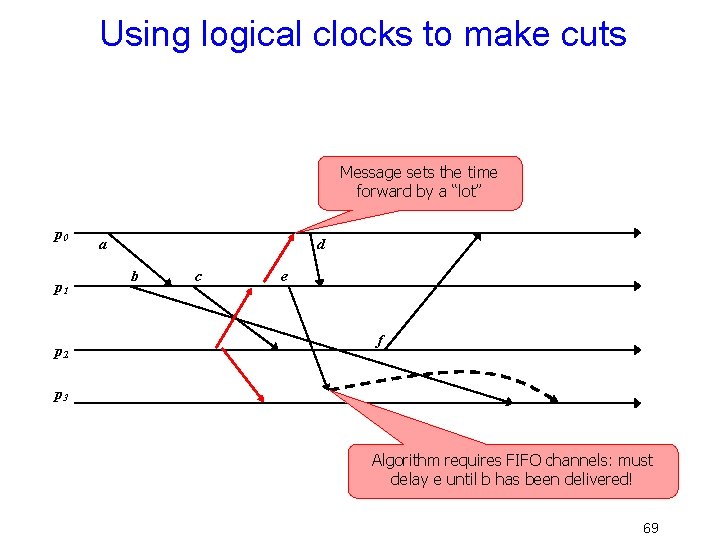

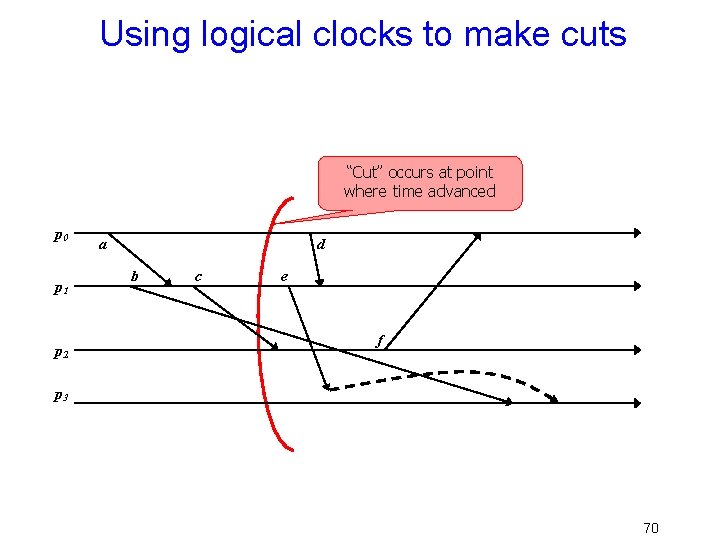

Chandy/Lamport Algorithm • Assume that if pi can talk to pj they do so using a lossless, FIFO connection • Now think about logical clocks – Suppose someone sets his clock way ahead and triggers a “flood” of messages – As these reach process, it advances its own time… eventually all do so. • The point where time jumps forward is a consistent cut across the system 68

Using logical clocks to make cuts Message sets the time forward by a “lot” p 0 p 1 p 2 a d b c e f p 3 Algorithm requires FIFO channels: must delay e until b has been delivered! 69

Using logical clocks to make cuts “Cut” occurs at point where time advanced p 0 p 1 p 2 a d b c e f p 3 70

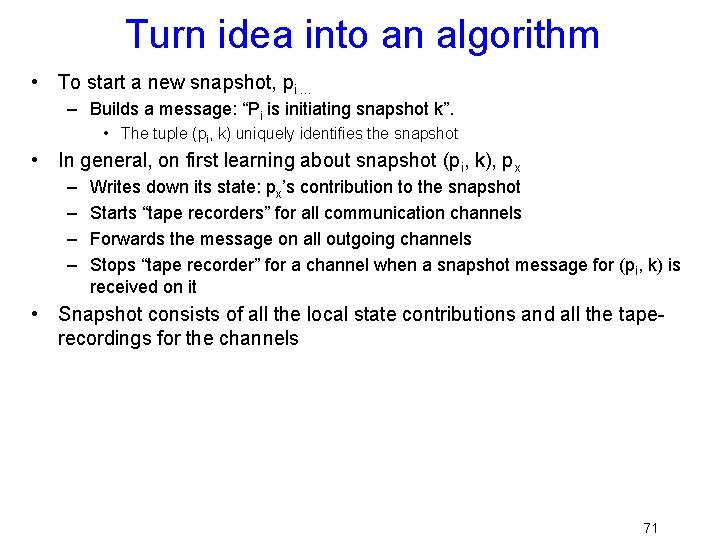

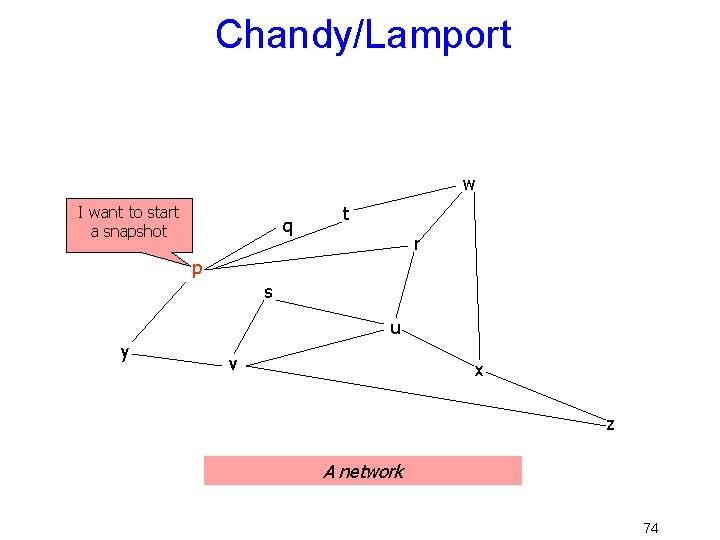

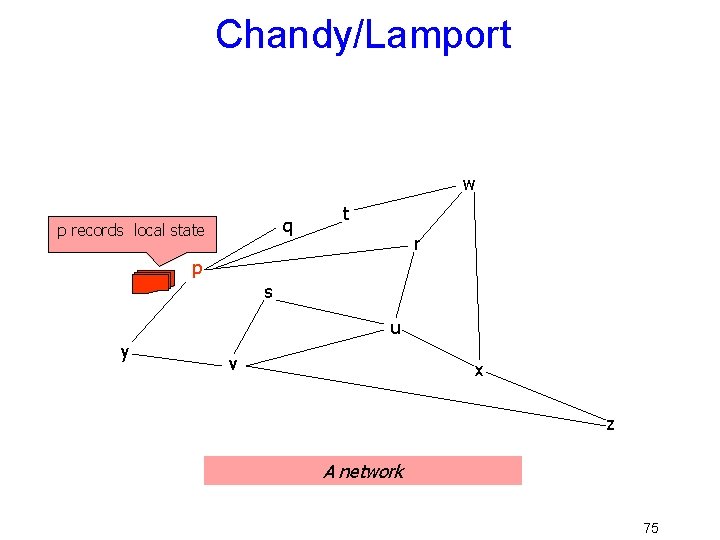

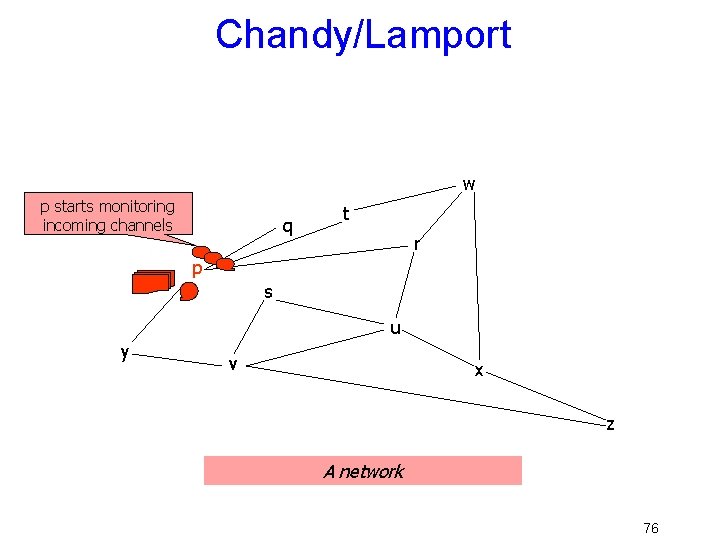

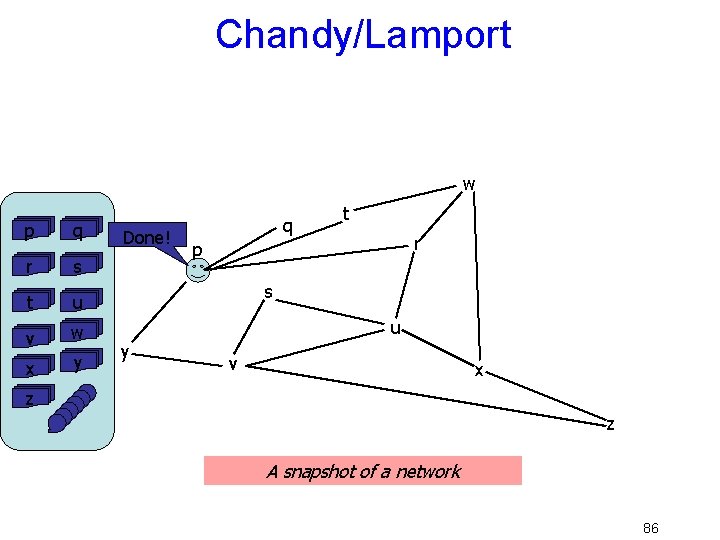

Turn idea into an algorithm • To start a new snapshot, pi … – Builds a message: “Pi is initiating snapshot k”. • The tuple (pi, k) uniquely identifies the snapshot • In general, on first learning about snapshot (pi, k), px – – Writes down its state: px’s contribution to the snapshot Starts “tape recorders” for all communication channels Forwards the message on all outgoing channels Stops “tape recorder” for a channel when a snapshot message for (pi, k) is received on it • Snapshot consists of all the local state contributions and all the taperecordings for the channels 71

Chandy/Lamport • This algorithm, but implemented with an outgoing flood, followed by an incoming wave of snapshot contributions • Snapshot ends up accumulating at the initiator, pi • Algorithm doesn’t tolerate process failures or message failures. 72

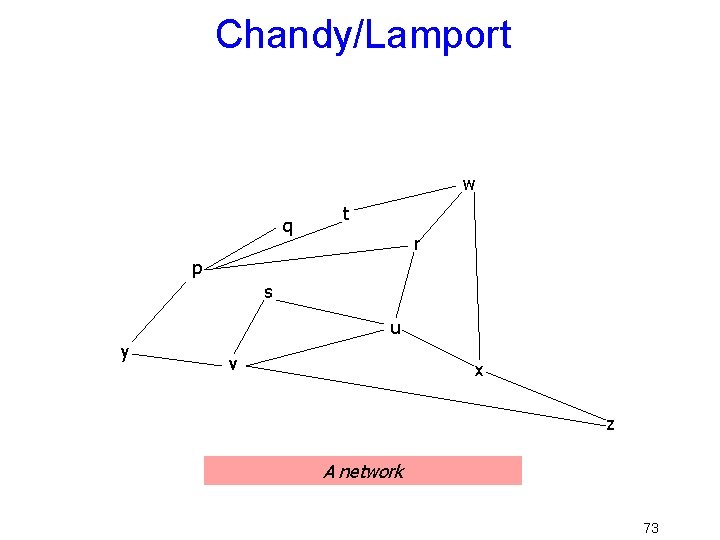

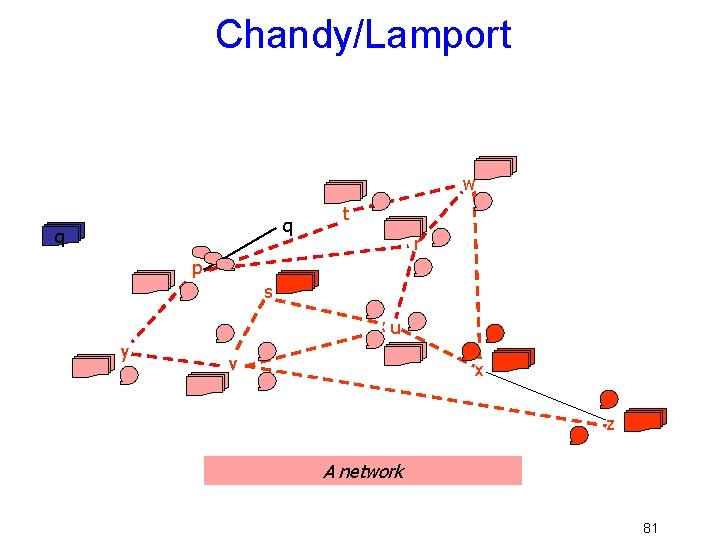

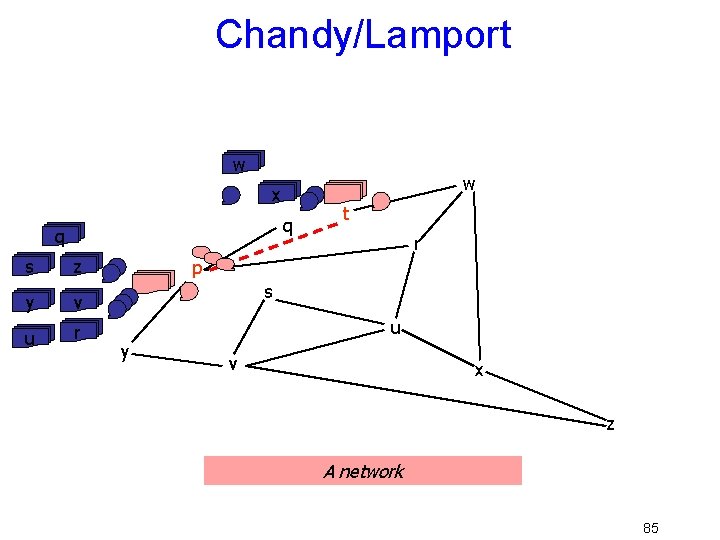

Chandy/Lamport w q t r p s u y v x z A network 73

Chandy/Lamport w I want to start a snapshot q t r p s u y v x z A network 74

Chandy/Lamport w q p records local state t r p s u y v x z A network 75

Chandy/Lamport w p starts monitoring incoming channels q t r p s u y v x z A network 76

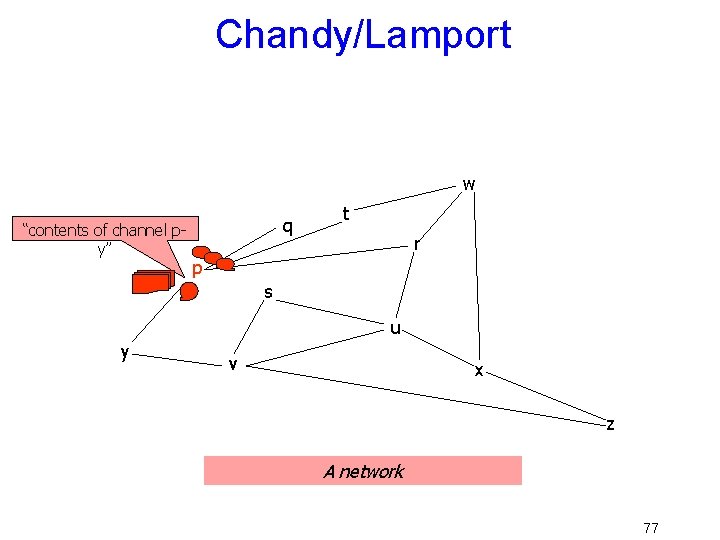

Chandy/Lamport w “contents of channel py” q t r p s u y v x z A network 77

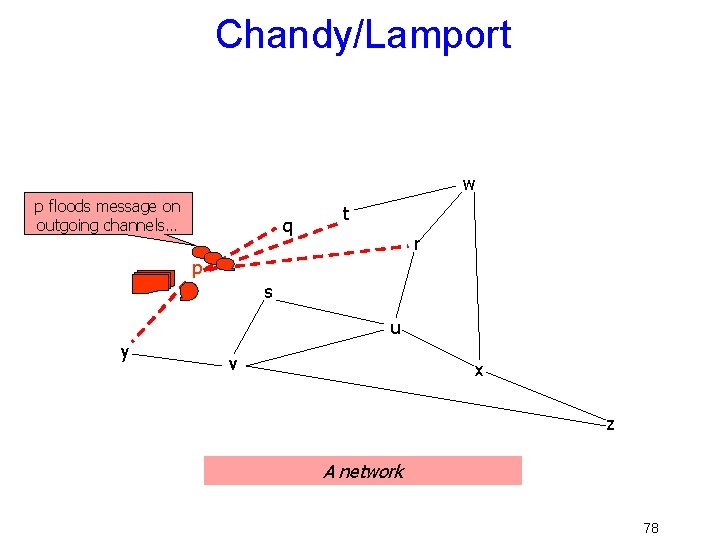

Chandy/Lamport w p floods message on outgoing channels… q t r p s u y v x z A network 78

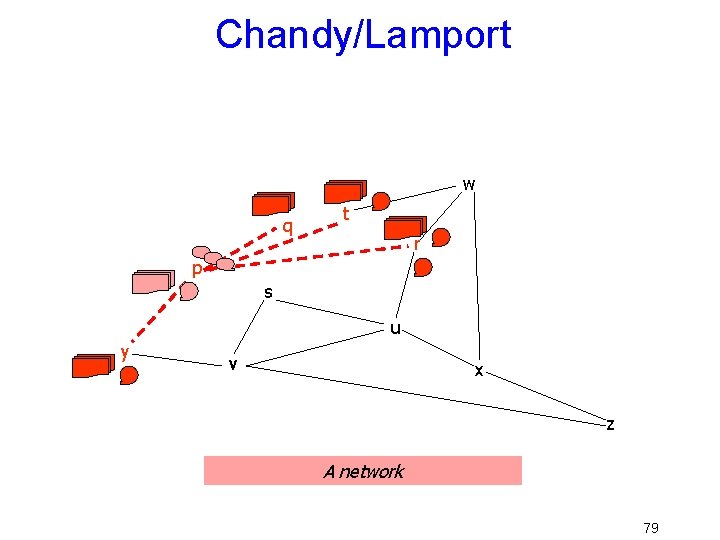

Chandy/Lamport w q t r p s u y v x z A network 79

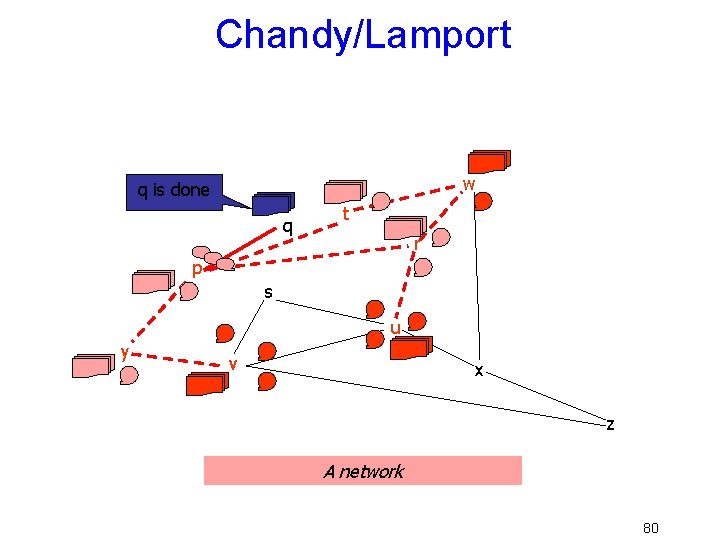

Chandy/Lamport w q is done q t r p s u y v x z A network 80

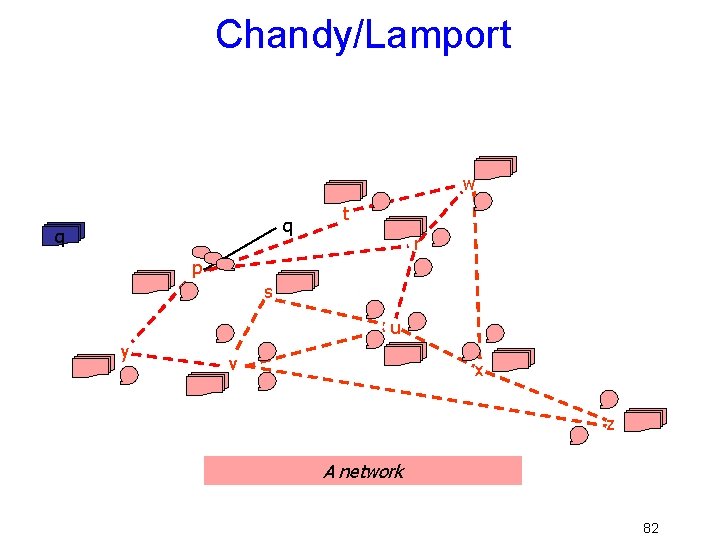

Chandy/Lamport w q q t r p s u y v x z A network 81

Chandy/Lamport w q q t r p s u y v x z A network 82

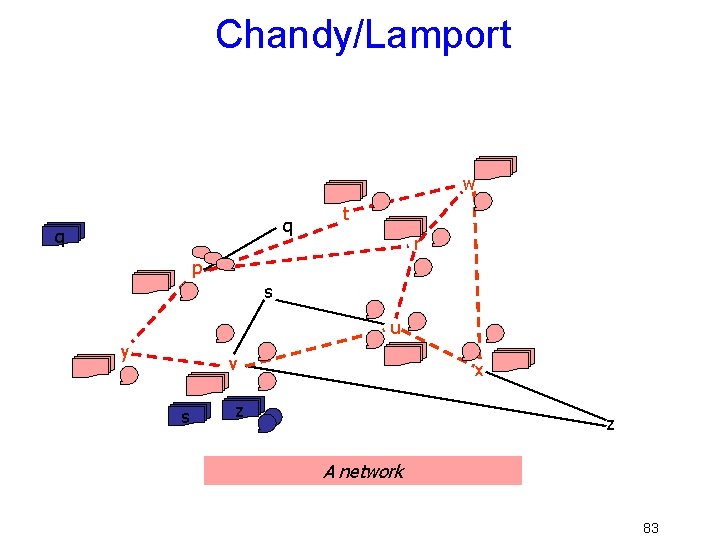

Chandy/Lamport w q q t r p s u y v s x z z A network 83

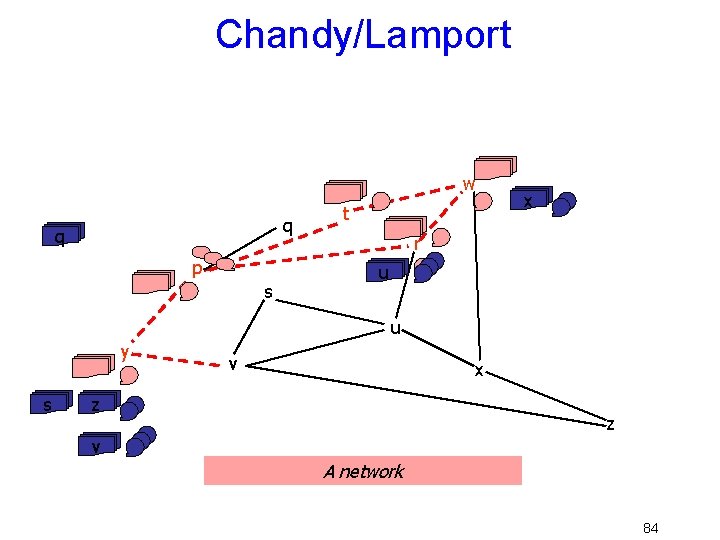

Chandy/Lamport w q q p s t x r u u y s v x z z v A network 84

Chandy/Lamport w w x q q s z y v u r t r p s u y v x z A network 85

Chandy/Lamport w p q r s t u v w x y Done! q t r p s u y v x z z A snapshot of a network 86

What’s in the “state”? • In practice we only record things important to the application running the algorithm, not the “whole” state – E. g. “locks currently held”, “lock release messages” • Idea is that the snapshot will be – Easy to analyze, letting us build a picture of the system state – And will have everything that matters for our real purpose, like deadlock detection 87

Summary • Types of faults – Crash, fail-stop, non-malicious Byzantine, Byzantine • Two-phase commit: distributed decision making – First, make sure everyone guarantees that they will commit if asked (prepare) – Next, ask everyone to commit – Assumes crash or fail-stop faults • Byzantine General’s Problem: distributed decision making with malicious failures – n general: some number of them may be malicious (upto “f” of them) – All non-malicious generals must come to same decision – Only solvable if n 3 f+1, but costs (f+1)*n 2 , messages 88

- Slides: 88