Discrete Maths 240 213 Semester 1 2021 2022

- Slides: 42

Discrete Maths 240 -213 , Semester 1, 2021 -2022 3. Predicate Logic • Objective to introduce predicate logic (also called the predicate calculus) 1

Overview 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Motivation Predicate Logic Quantifiers From English to Logic Domain Affects Translation Examples The Barber Paradox More Information 2

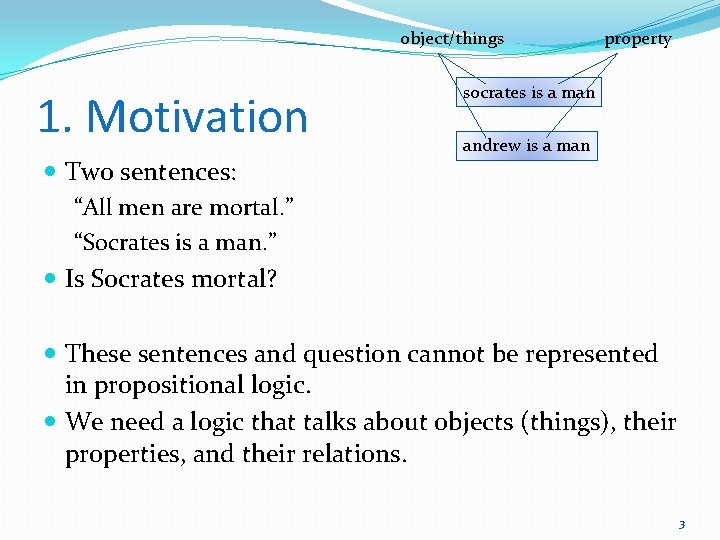

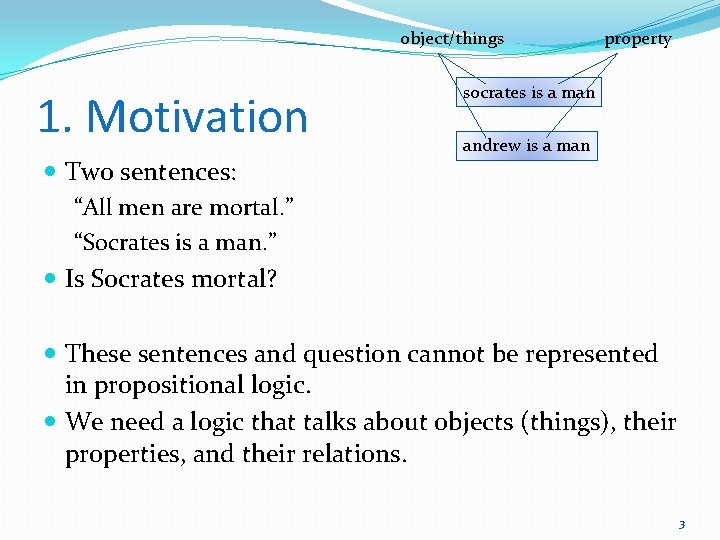

object/things 1. Motivation Two sentences: “All men are mortal. ” “Socrates is a man. ” Is Socrates mortal? property socrates is a man andrew is a man These sentences and question cannot be represented in propositional logic. We need a logic that talks about objects (things), their properties, and their relations. 3

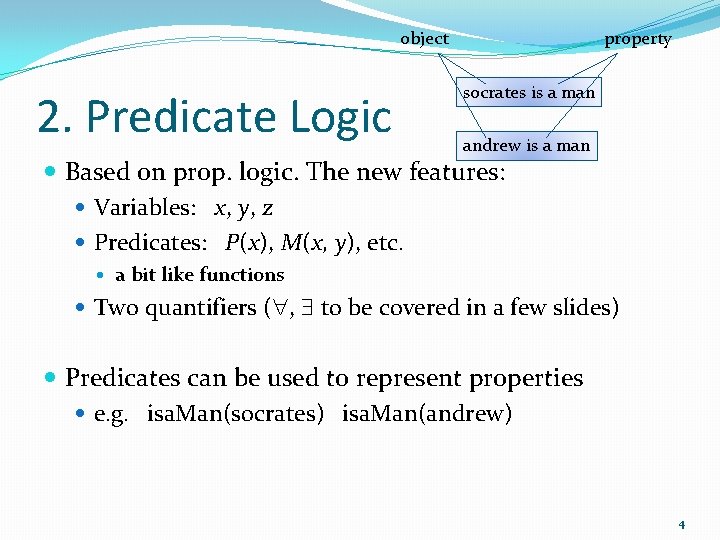

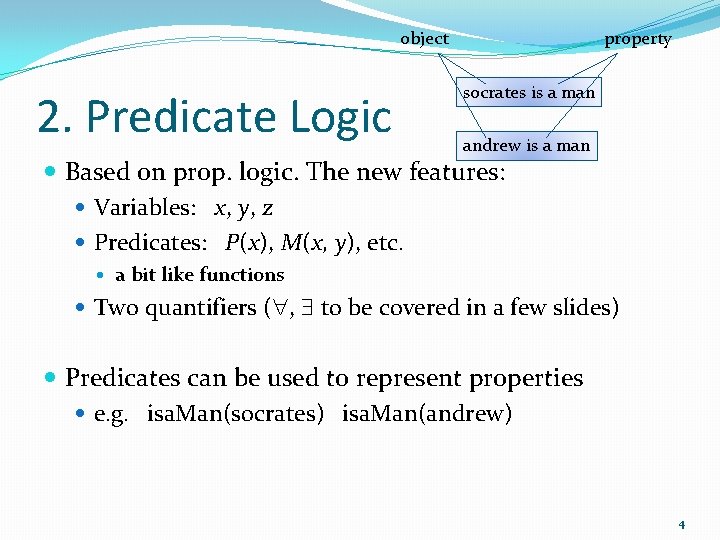

object 2. Predicate Logic property socrates is a man andrew is a man Based on prop. logic. The new features: Variables: x, y, z Predicates: P(x), M(x, y), etc. a bit like functions Two quantifiers ( , to be covered in a few slides) Predicates can be used to represent properties e. g. isa. Man(socrates) isa. Man(andrew) 4

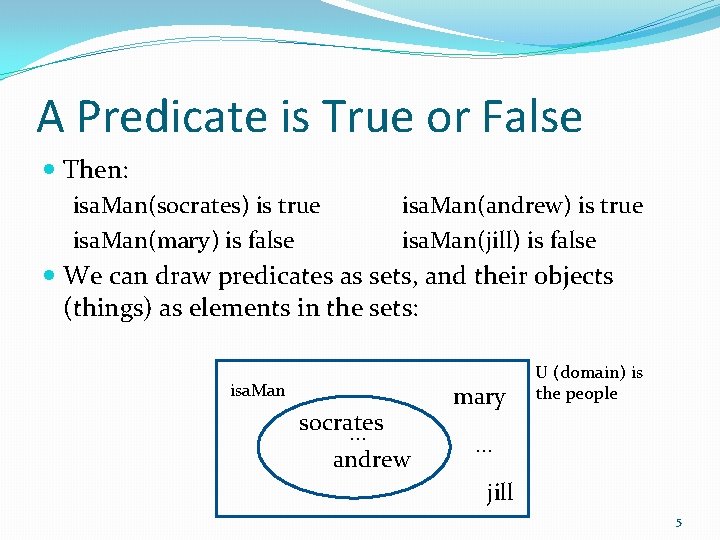

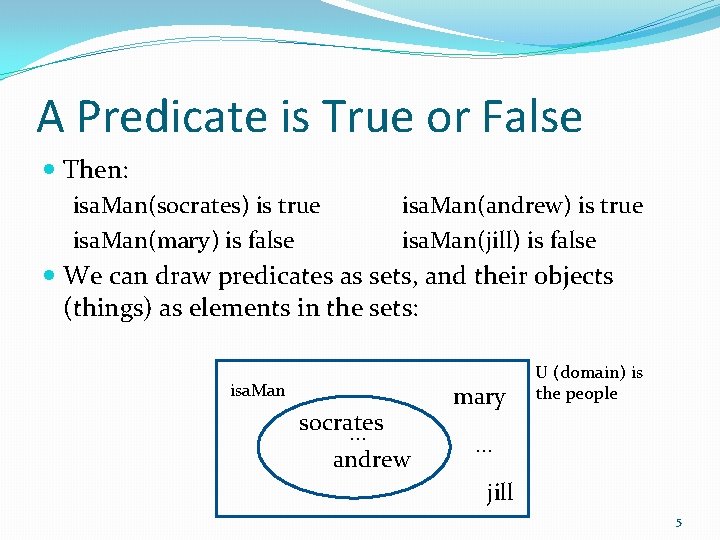

A Predicate is True or False Then: isa. Man(socrates) is true isa. Man(andrew) is true isa. Man(mary) is false isa. Man(jill) is false We can draw predicates as sets, and their objects (things) as elements in the sets: isa. Man socrates. . . andrew mary U (domain) is the people . . . jill 5

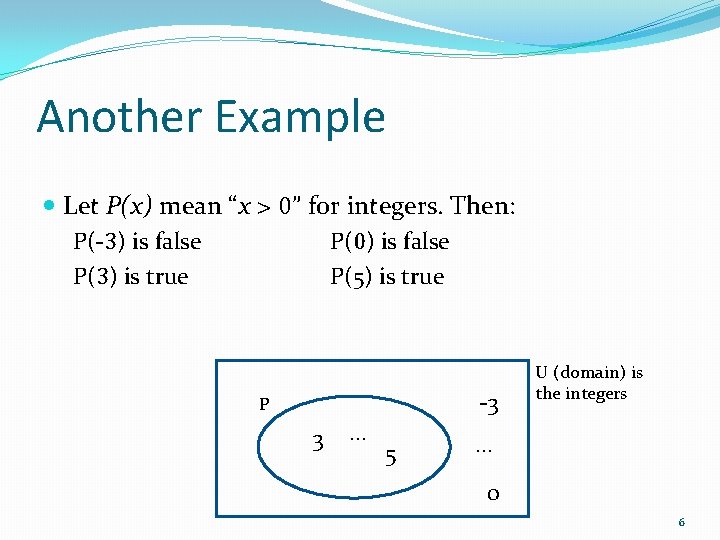

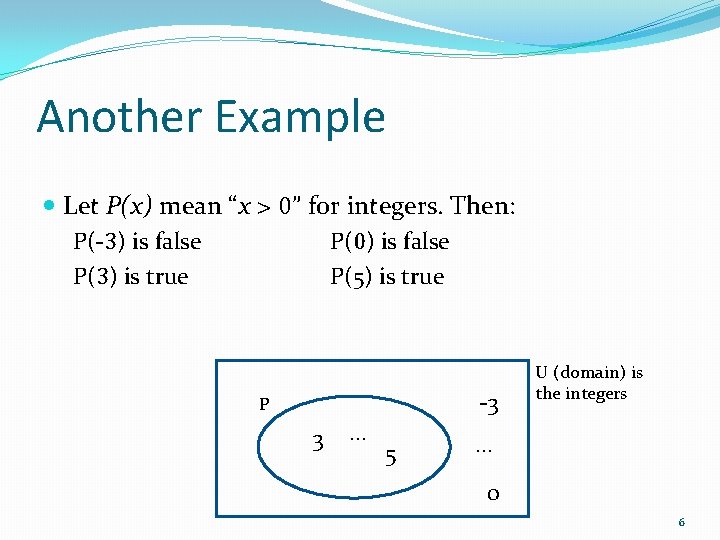

Another Example Let P(x) mean “x > 0” for integers. Then: P(-3) is false P(0) is false P(3) is true P(5) is true -3 P 3 . . . 5 U (domain) is the integers . . . 0 6

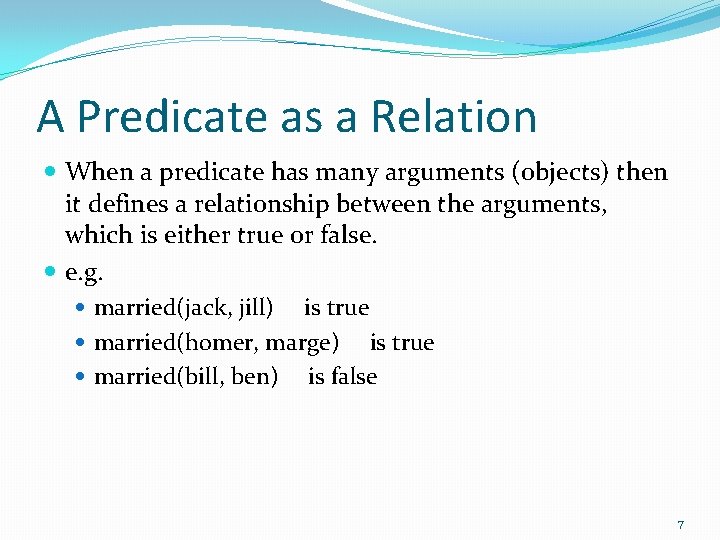

A Predicate as a Relation When a predicate has many arguments (objects) then it defines a relationship between the arguments, which is either true or false. e. g. married(jack, jill) is true married(homer, marge) is true married(bill, ben) is false 7

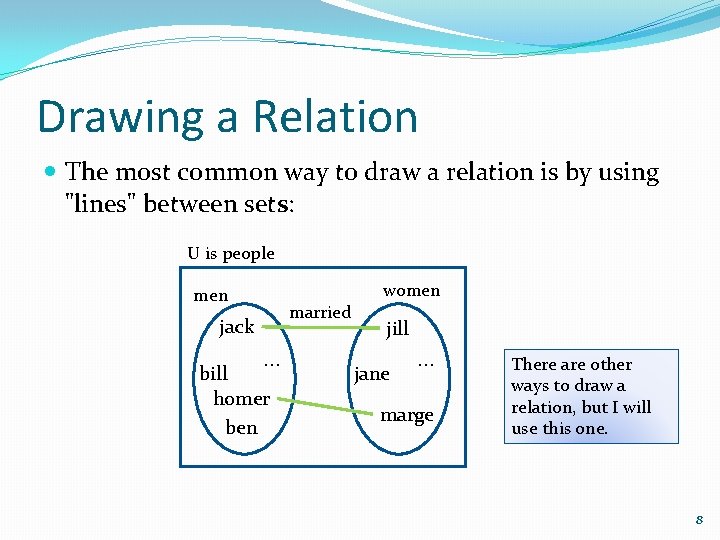

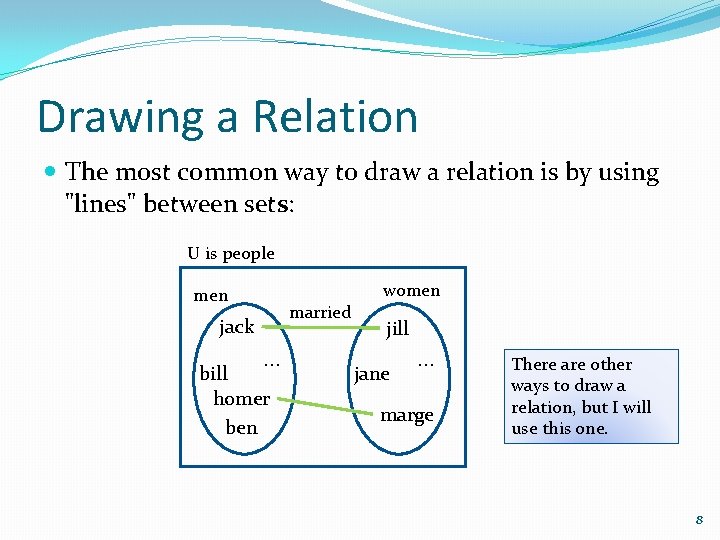

Drawing a Relation The most common way to draw a relation is by using "lines" between sets: U is people women married jack . . . bill homer ben jill jane . . . marge There are other ways to draw a relation, but I will use this one. 8

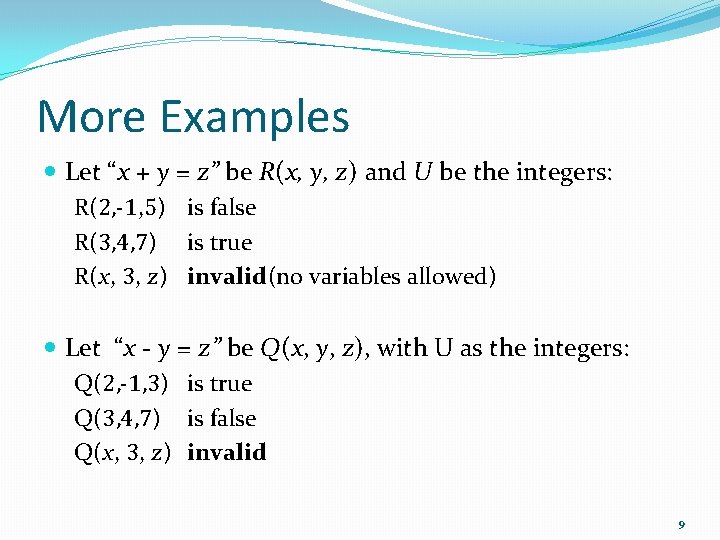

More Examples Let “x + y = z” be R(x, y, z) and U be the integers: R(2, -1, 5) is false R(3, 4, 7) is true R(x, 3, z) invalid (no variables allowed) Let “x - y = z” be Q(x, y, z), with U as the integers: Q(2, -1, 3) is true Q(3, 4, 7) is false Q(x, 3, z) invalid 9

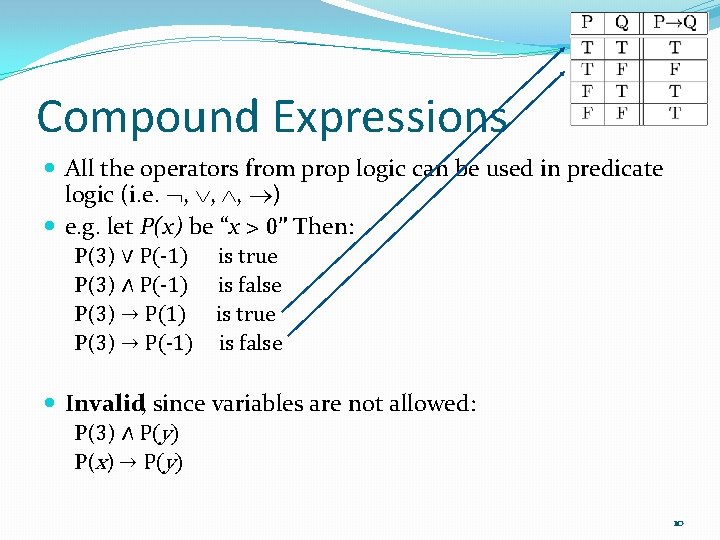

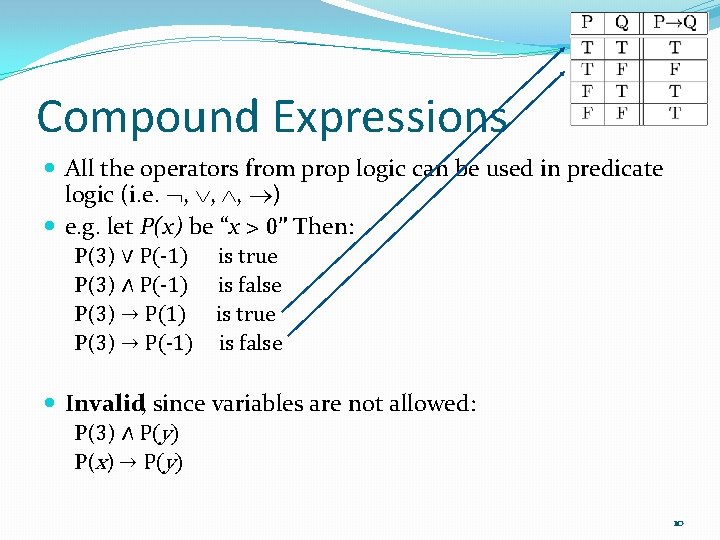

Compound Expressions All the operators from prop logic can be used in predicate logic (i. e. , , , ) e. g. let P(x) be “x > 0” Then: P(3) ∨ P(-1) is true P(3) ∧ P(-1) is false P(3) → P(1) is true P(3) → P(-1) is false Invalid, since variables are not allowed: P(3) ∧ P(y) P(x) → P(y) 10

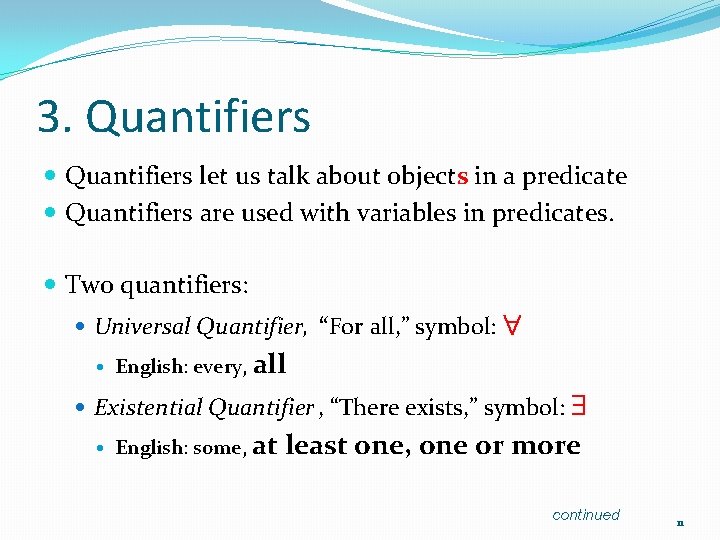

3. Quantifiers let us talk about objects in a predicate Quantifiers are used with variables in predicates. Two quantifiers: Universal Quantifier, “For all, ” symbol: English: every, all English: some, at least one, one or more Existential Quantifier , “There exists, ” symbol: continued 11

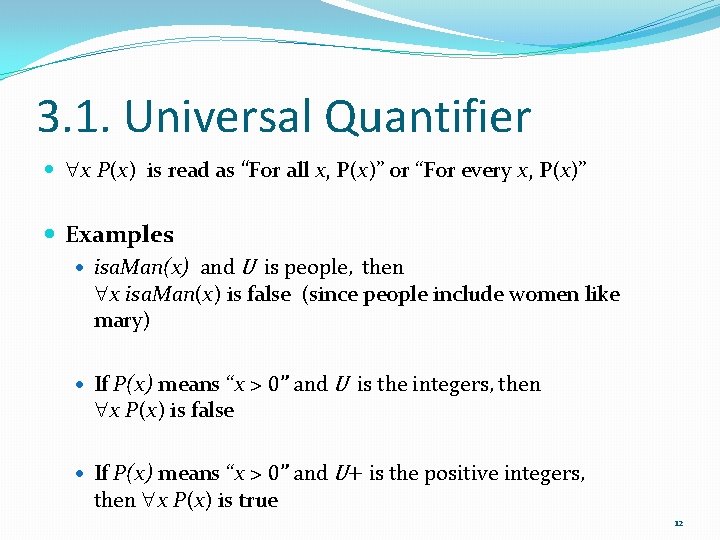

3. 1. Universal Quantifier x P(x) is read as “For all x, P(x)” or “For every x, P(x)” Examples: isa. Man(x) and U is people, then x isa. Man(x) is false (since people include women like mary) If P(x) means “x > 0” and U is the integers, then x P(x) is false If P(x) means “x > 0” and U+ is the positive integers, then x P(x) is true 12

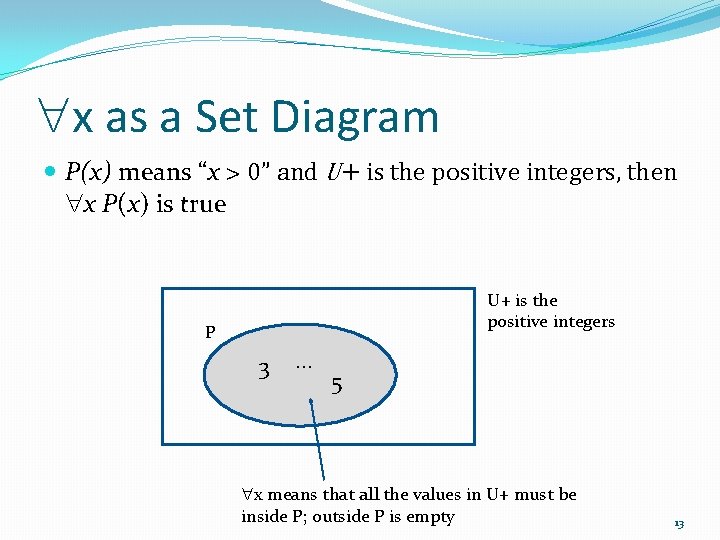

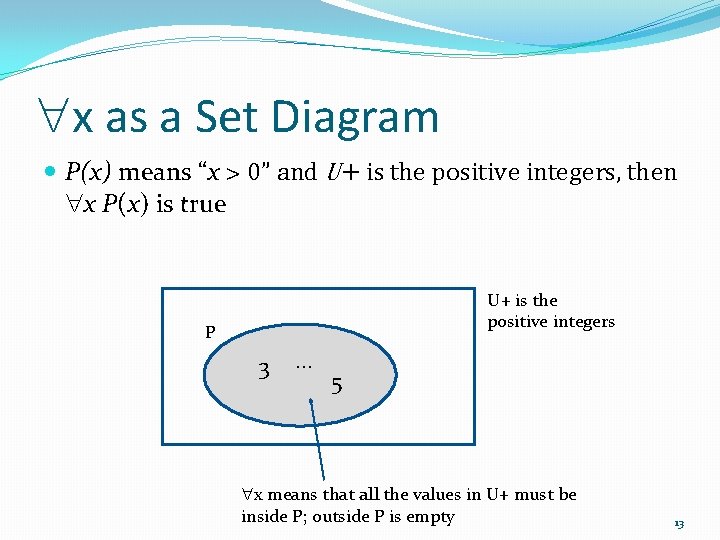

x as a Set Diagram P(x) means “x > 0” and U+ is the positive integers, then x P(x) is true U+ is the positive integers P 3 . . . 5 x means that all the values in U+ must be inside P; outside P is empty 13

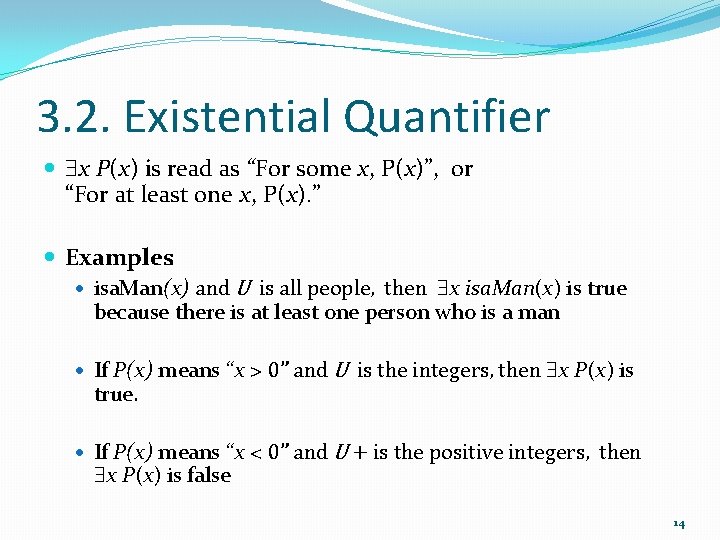

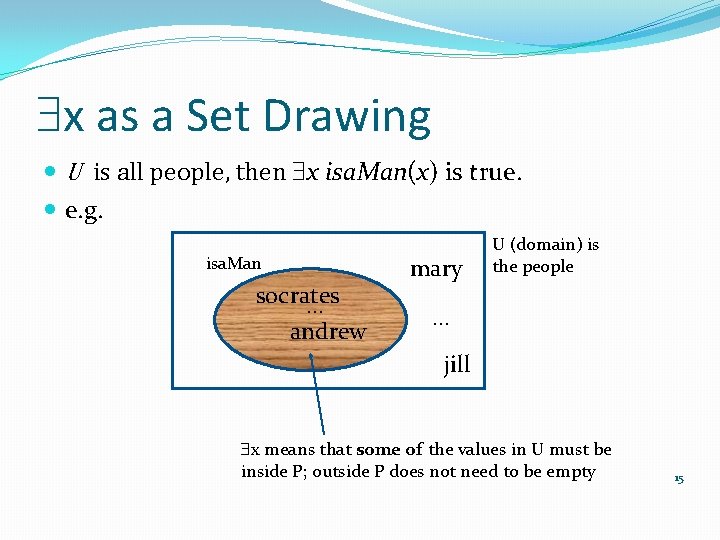

3. 2. Existential Quantifier x P(x) is read as “For some x, P(x)”, or “For at least one x, P(x). ” Examples: isa. Man(x) and U is all people, then x isa. Man(x) is true because there is at least one person who is a man If P(x) means “x > 0” and U is the integers, then x P(x) is true. If P(x) means “x < 0” and U + is the positive integers, then x P(x) is false 14

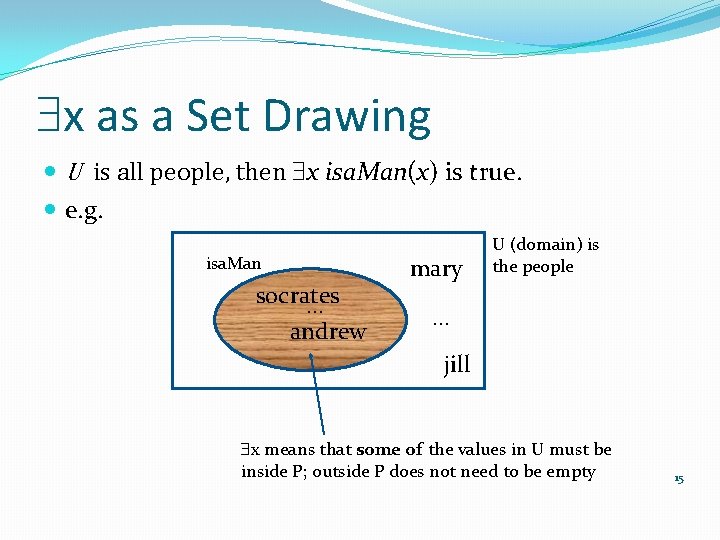

x as a Set Drawing U is all people, then x isa. Man(x) is true. e. g. isa. Man socrates. . . andrew mary U (domain) is the people . . . jill x means that some of the values in U must be inside P; outside P does not need to be empty 15

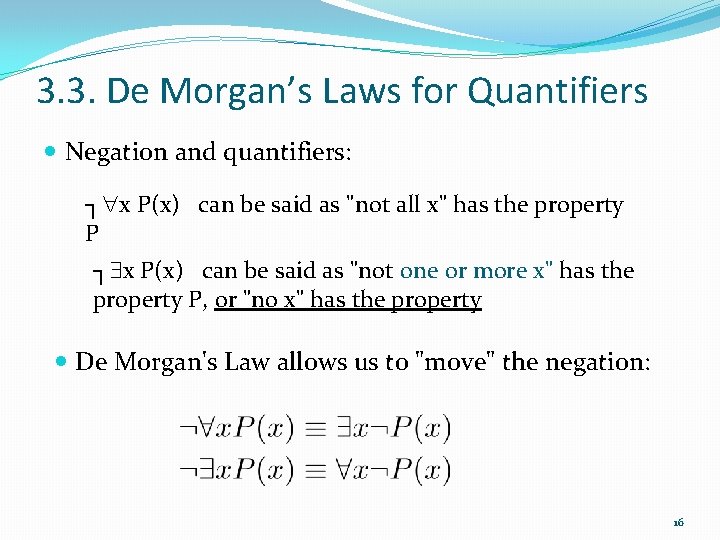

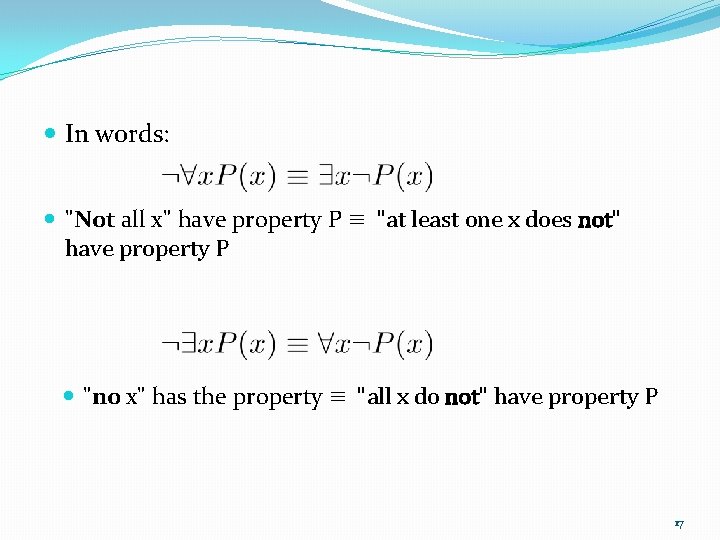

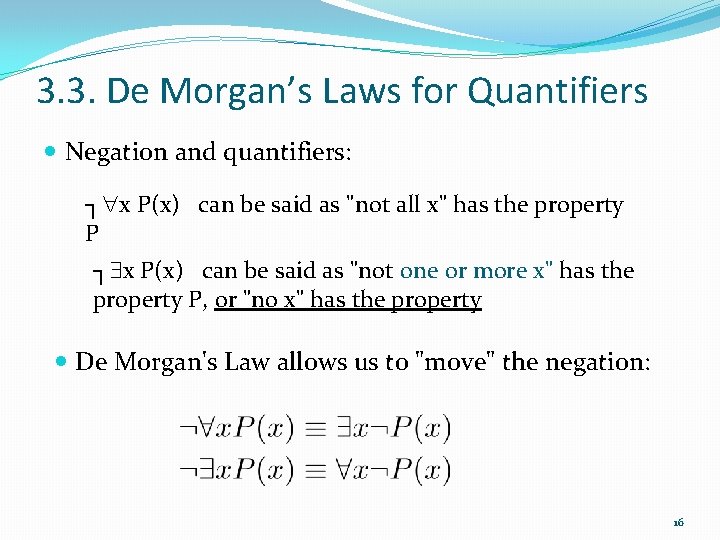

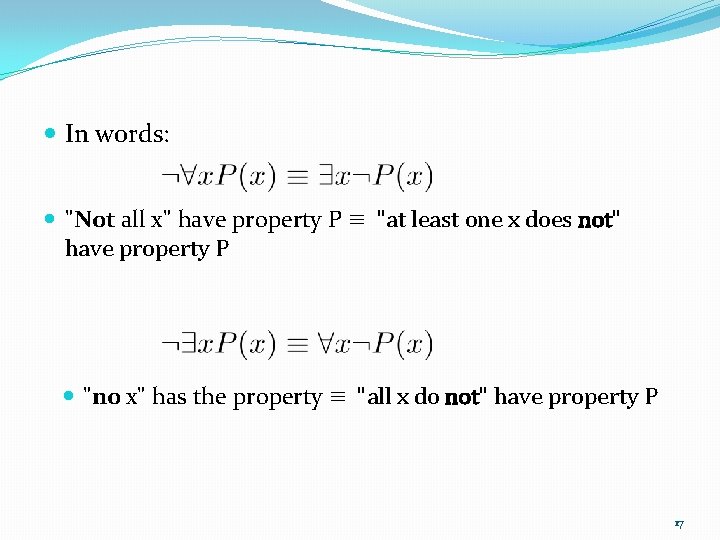

3. 3. De Morgan’s Laws for Quantifiers Negation and quantifiers: ┐ x P(x) can be said as "not all x" has the property P ┐ x P(x) can be said as "not one or more x" has the property P, or "no x" has the property De Morgan's Law allows us to "move" the negation: 16

In words: "Not all x" have property P ≡ "at least one x does not" have property P "no x" has the property ≡ "all x do not" have property P 17

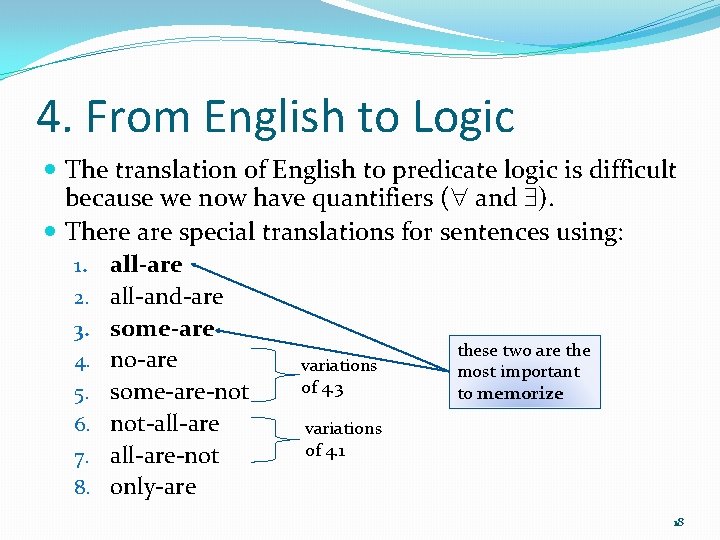

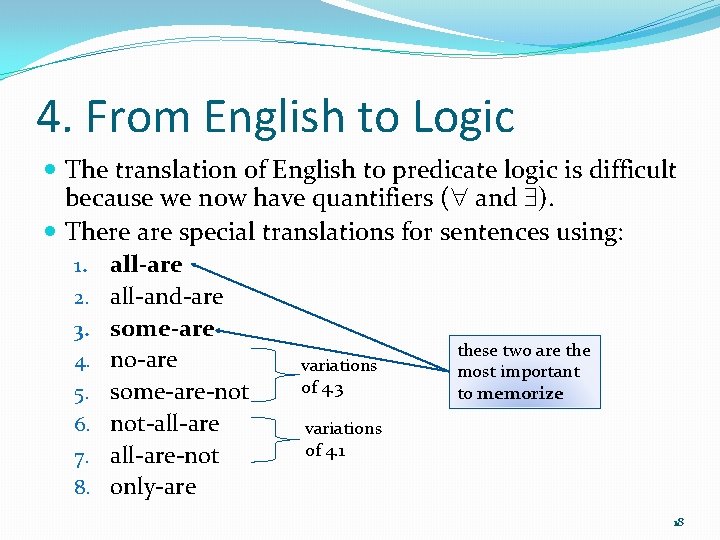

4. From English to Logic The translation of English to predicate logic is difficult because we now have quantifiers ( and ). There are special translations for sentences using: 1. all-are 2. all-and-are 3. some-are these two are the 4. no-are variations most important of 4. 3 to memorize 5. some-are-not 6. not-all-are variations of 4. 1 7. all-are-not 8. only-are 18

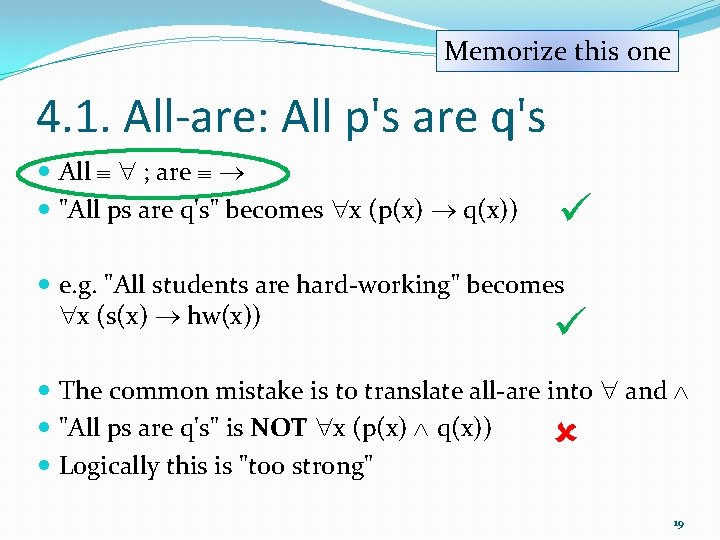

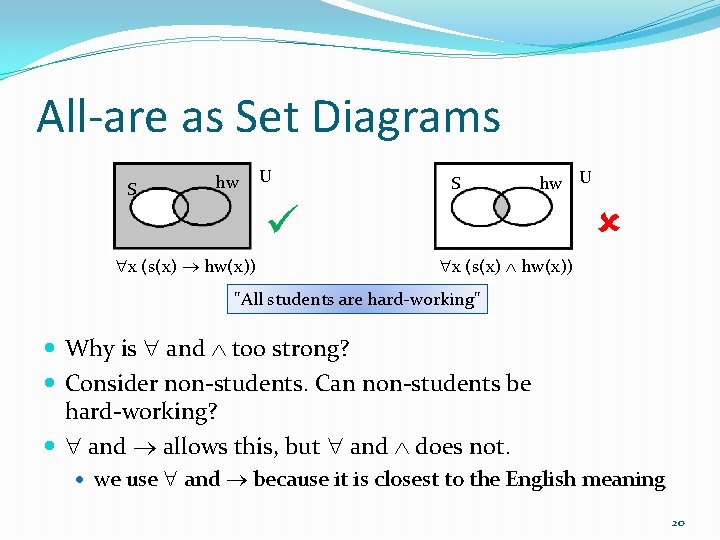

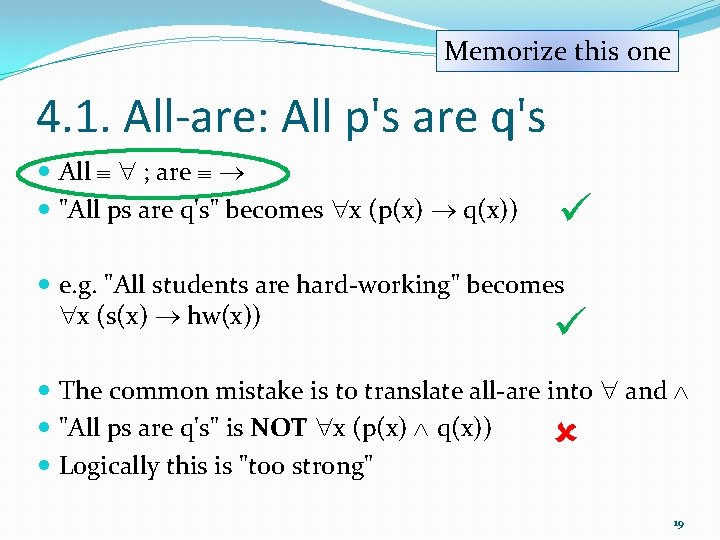

Memorize this one 4. 1. All-are: All p's are q's All ; are "All ps are q's" becomes x (p(x) q(x)) e. g. "All students are hard-working" becomes x (s(x) hw(x)) The common mistake is to translate all-are into and "All ps are q's" is NOT x (p(x) q(x)) Logically this is "too strong" 19

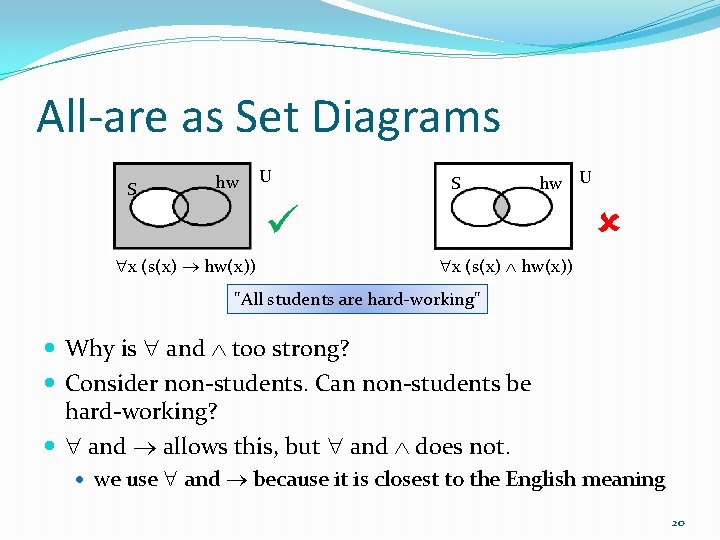

All-are as Set Diagrams S hw U x (s(x) hw(x)) "All students are hard-working" Why is and too strong? Consider non-students. Can non-students be hard-working? and allows this, but and does not. we use and because it is closest to the English meaning 20

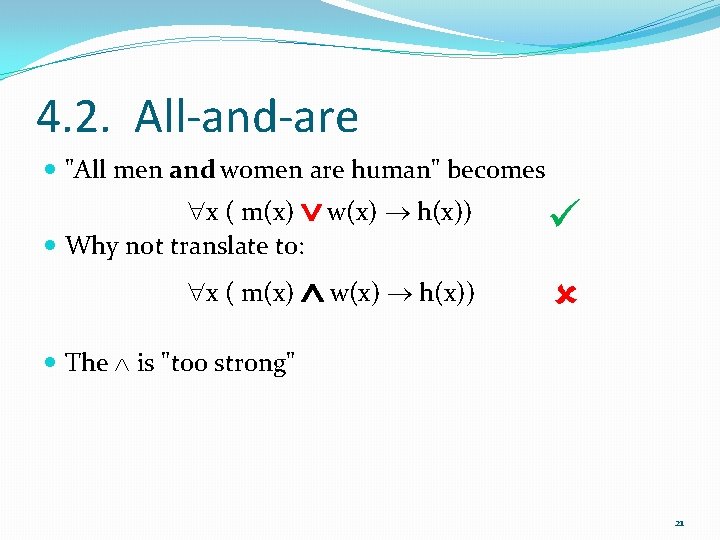

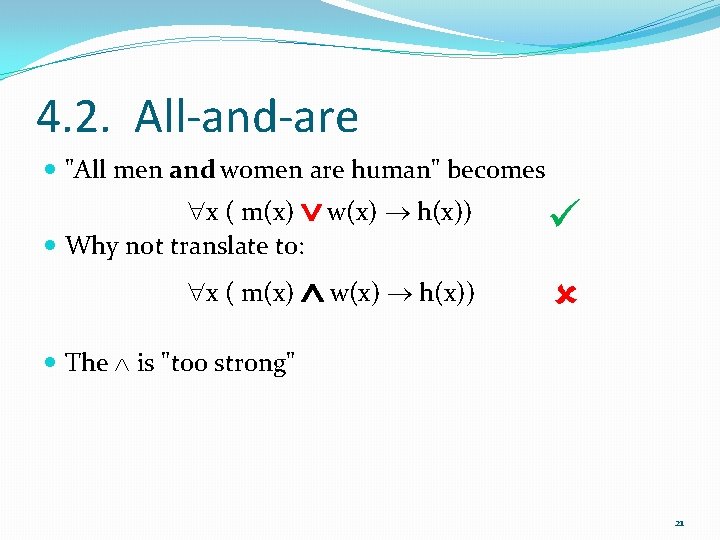

4. 2. All-and-are "All men and women are human" becomes x ( m(x) w(x) h(x)) Why not translate to: x ( m(x) w(x) h(x)) The is "too strong" 21

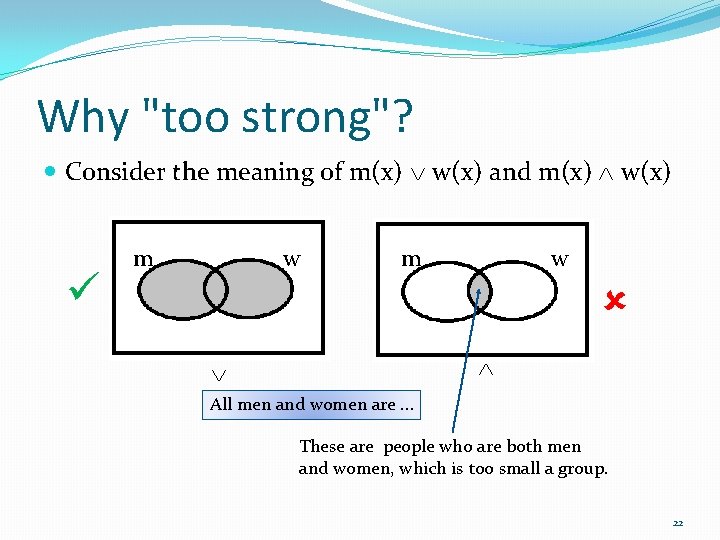

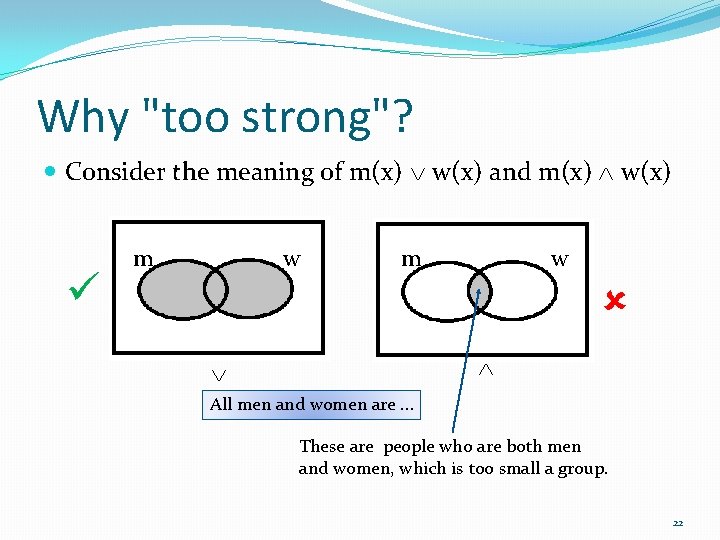

Why "too strong"? Consider the meaning of m(x) w(x) and m(x) w(x) m w All men and women are. . . These are people who are both men and women, which is too small a group. 22

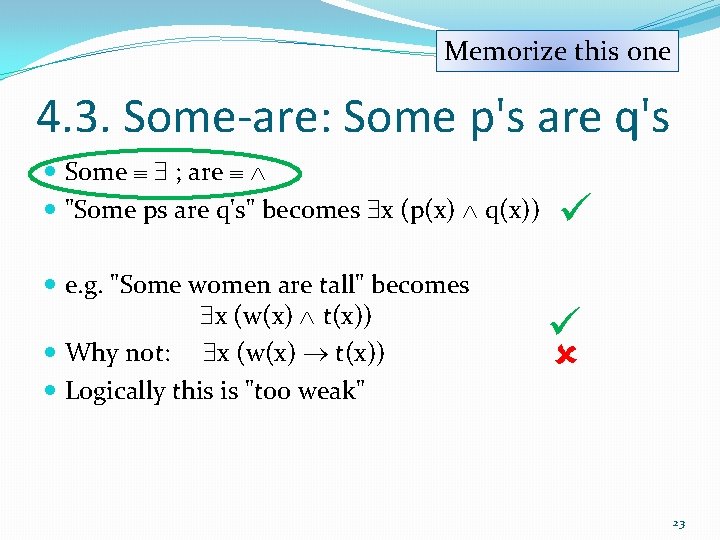

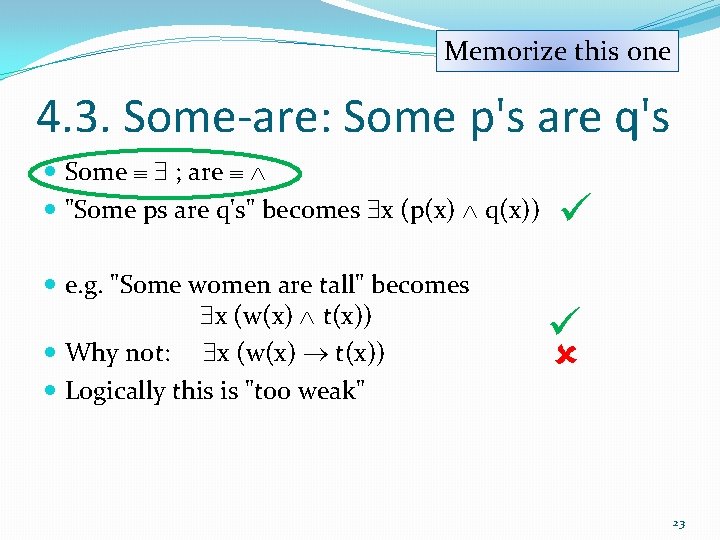

Memorize this one 4. 3. Some-are: Some p's are q's Some ; are "Some ps are q's" becomes x (p(x) q(x)) e. g. "Some women are tall" becomes x (w(x) t(x)) Why not: x (w(x) t(x)) Logically this is "too weak" 23

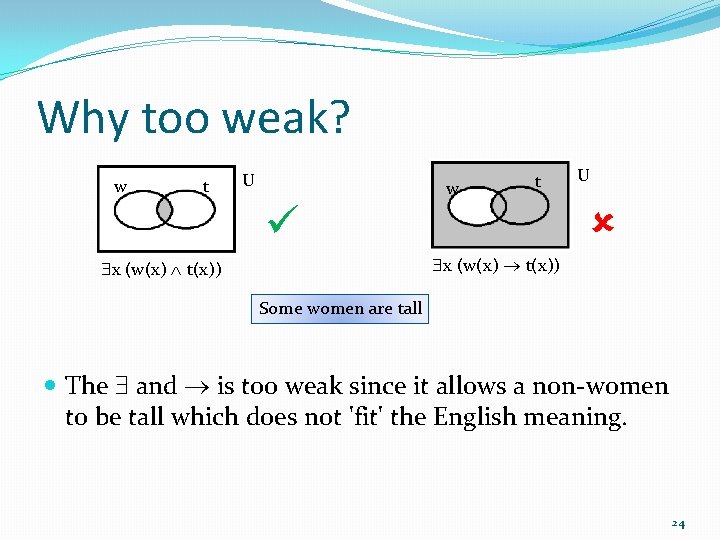

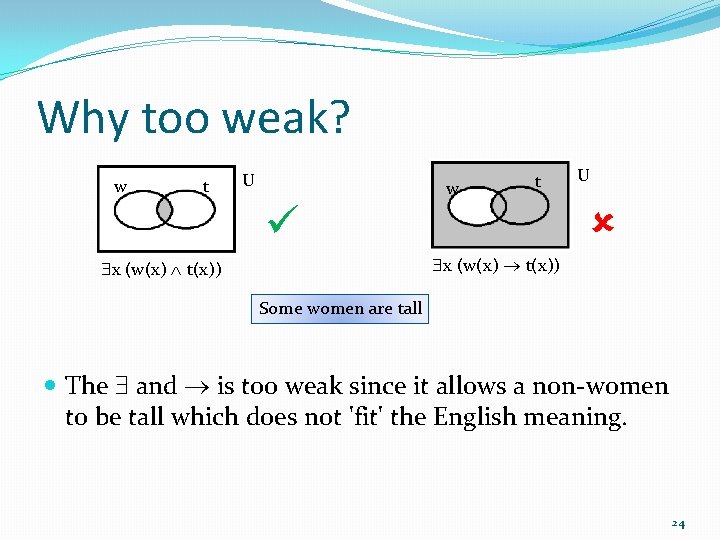

Why too weak? w t U x (w(x) t(x)) Some women are tall The and is too weak since it allows a non-women to be tall which does not 'fit' the English meaning. 24

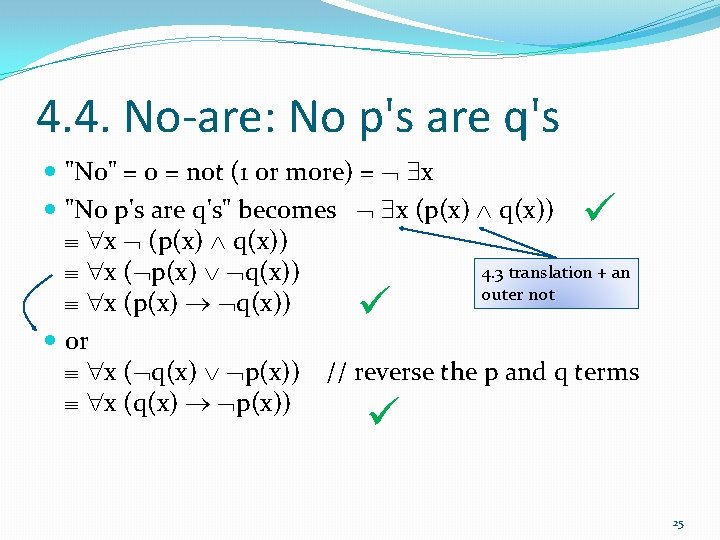

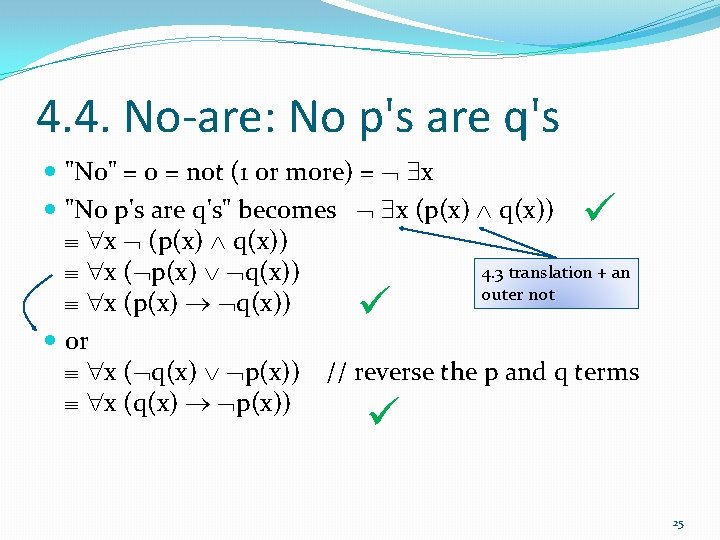

4. 4. No-are: No p's are q's "No" = 0 = not (1 or more) = x "No p's are q's" becomes x (p(x) q(x)) x (p(x) q(x)) 4. 3 translation + an x ( p(x) q(x)) outer not x (p(x) q(x)) or x ( q(x) p(x)) // reverse the p and q terms x (q(x) p(x)) 25

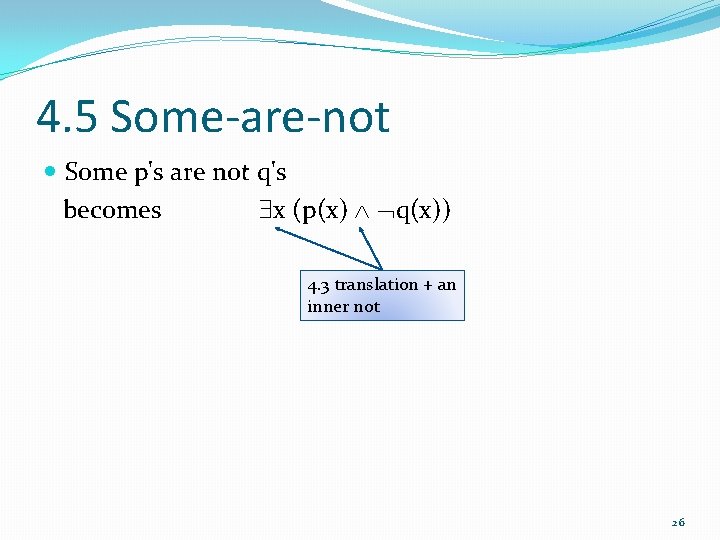

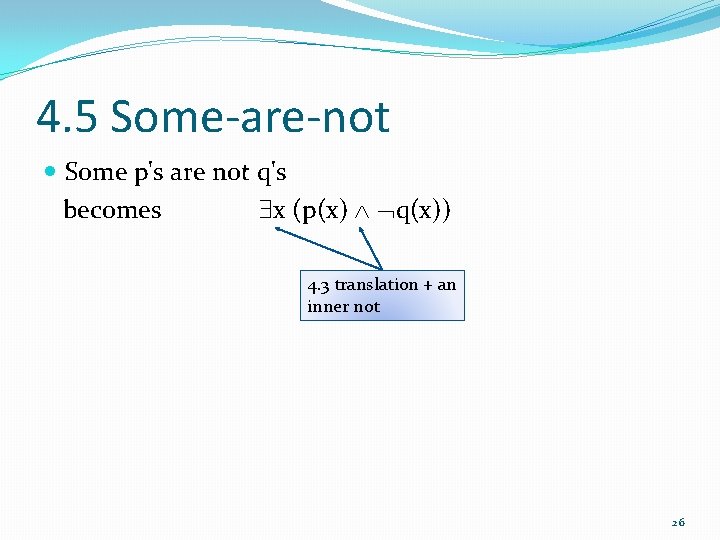

4. 5 Some-are-not Some p's are not q's becomes x (p(x) q(x)) 4. 3 translation + an inner not 26

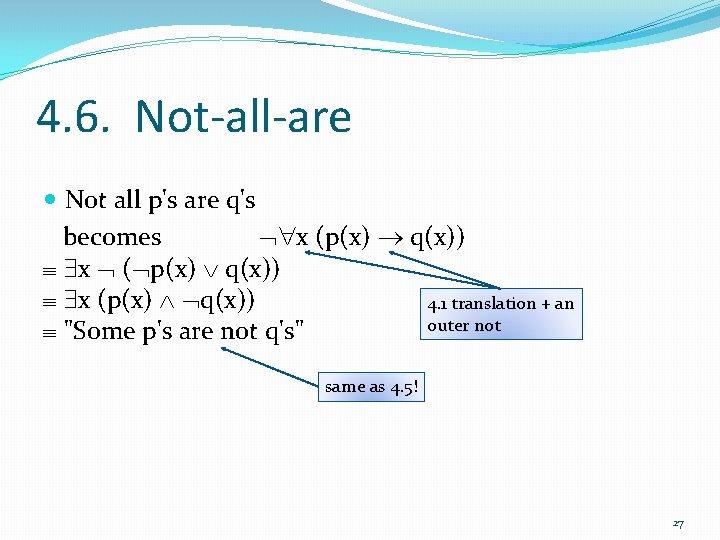

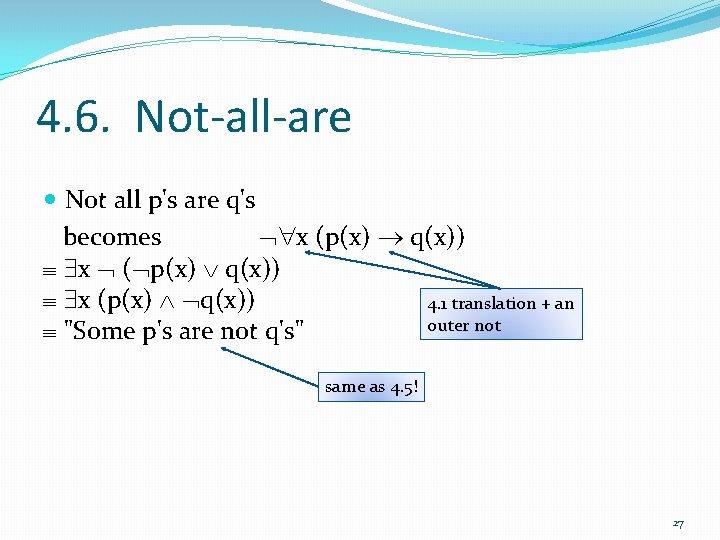

4. 6. Not-all-are Not all p's are q's becomes x (p(x) q(x)) x ( p(x) q(x)) x (p(x) q(x)) 4. 1 translation + an outer not "Some p's are not q's" same as 4. 5! 27

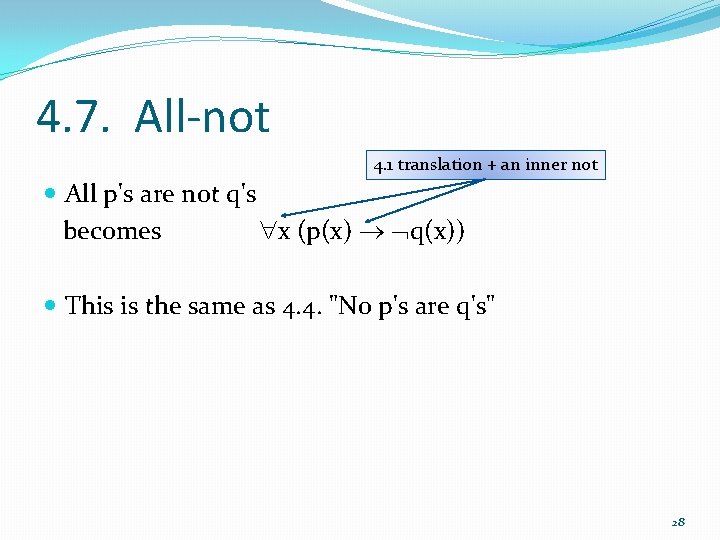

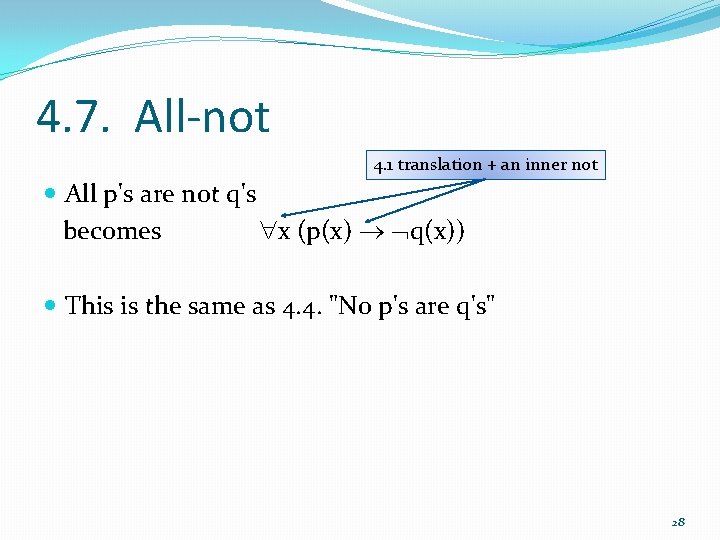

4. 7. All-not 4. 1 translation + an inner not All p's are not q's becomes x (p(x) q(x)) This is the same as 4. 4. "No p's are q's" 28

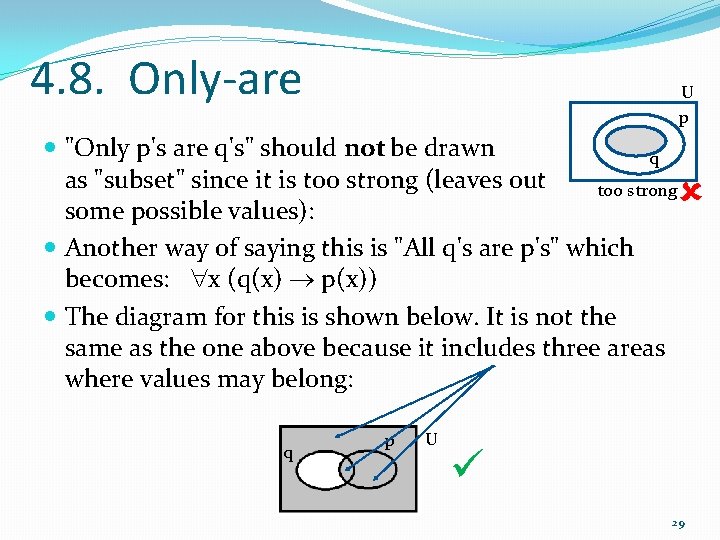

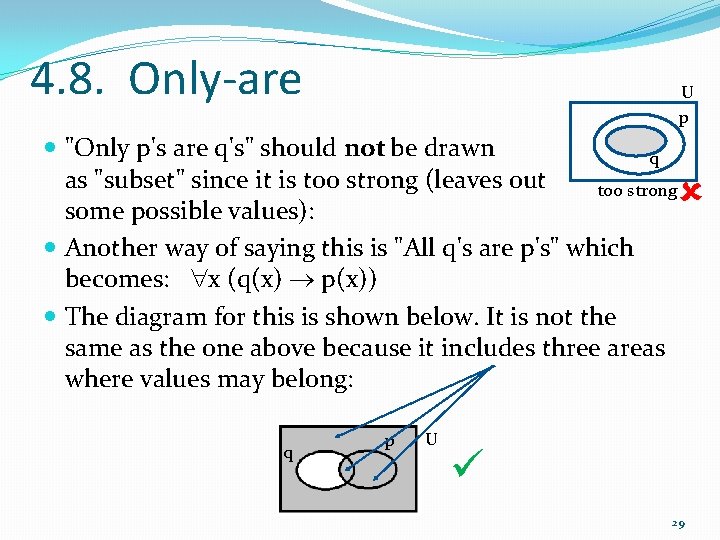

4. 8. Only-are U p "Only p's are q's" should not be drawn q as "subset" since it is too strong (leaves out too strong some possible values): Another way of saying this is "All q's are p's" which becomes: x (q(x) p(x)) The diagram for this is shown below. It is not the same as the one above because it includes three areas where values may belong: q p U 29

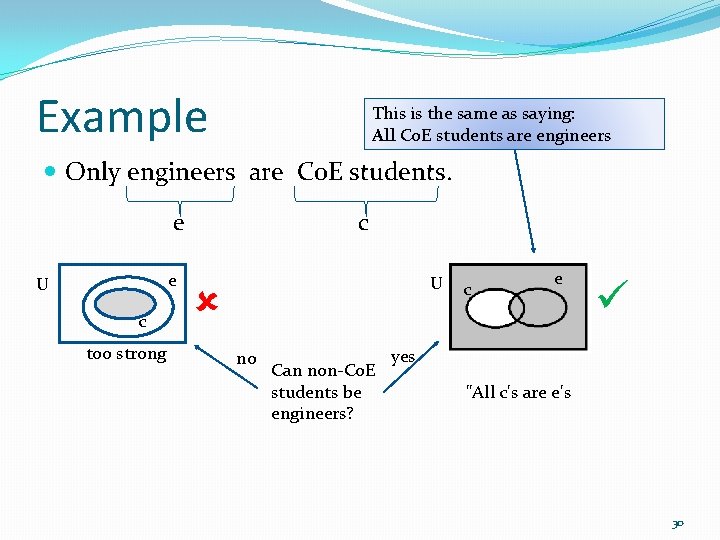

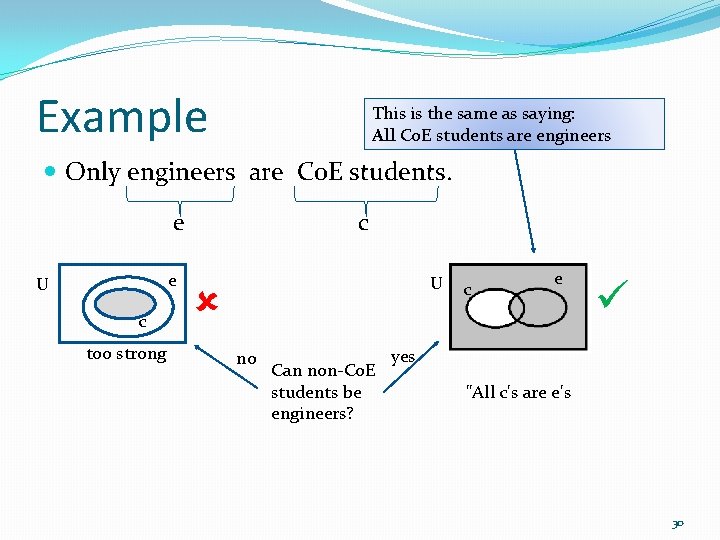

Example This is the same as saying: All Co. E students are engineers Only engineers are Co. E students. e e U c too strong c U no Can non-Co. E students be engineers? c e yes "All c's are e's 30

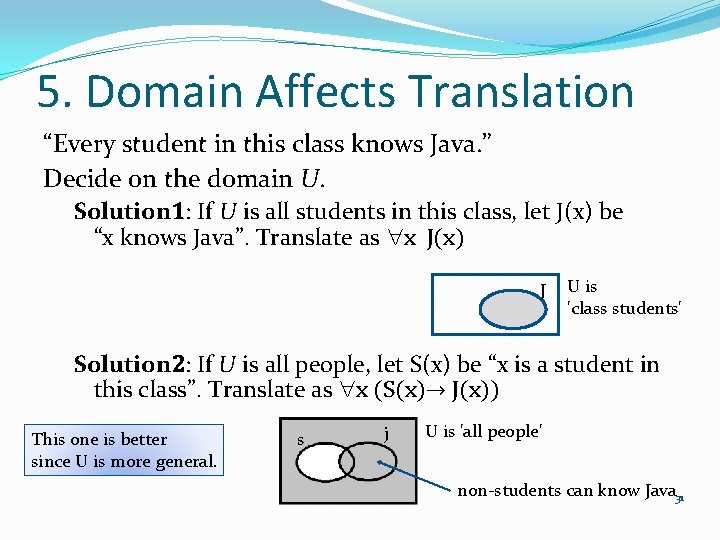

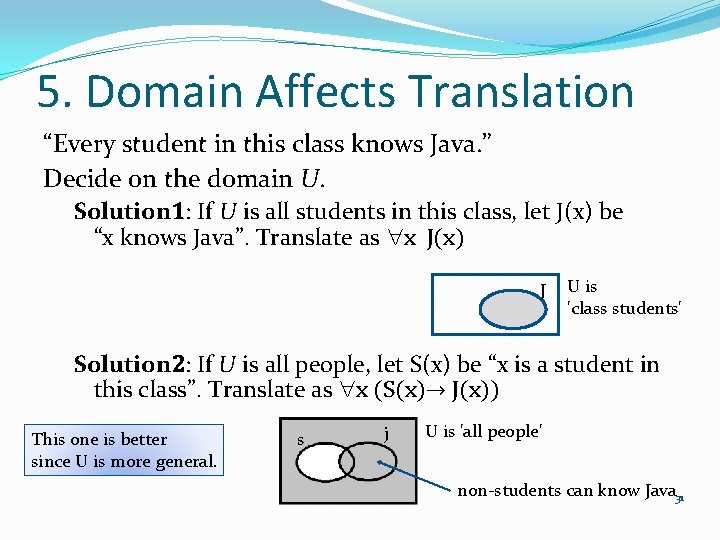

5. Domain Affects Translation “Every student in this class knows Java. ” Decide on the domain U. Solution 1: If U is all students in this class, let J(x) be “x knows Java”. Translate as x J(x) J U is 'class students' Solution 2: If U is all people, let S(x) be “x is a student in this class”. Translate as x (S(x)→ J(x)) This one is better since U is more general. s j U is 'all people' non-students can know Java 31

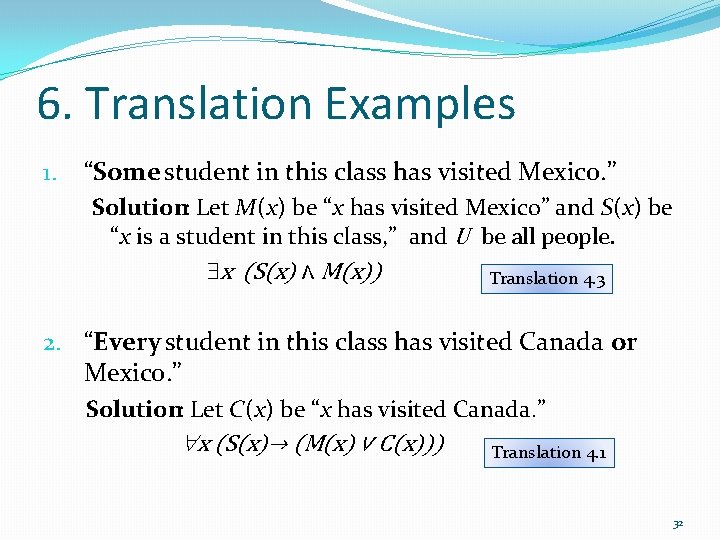

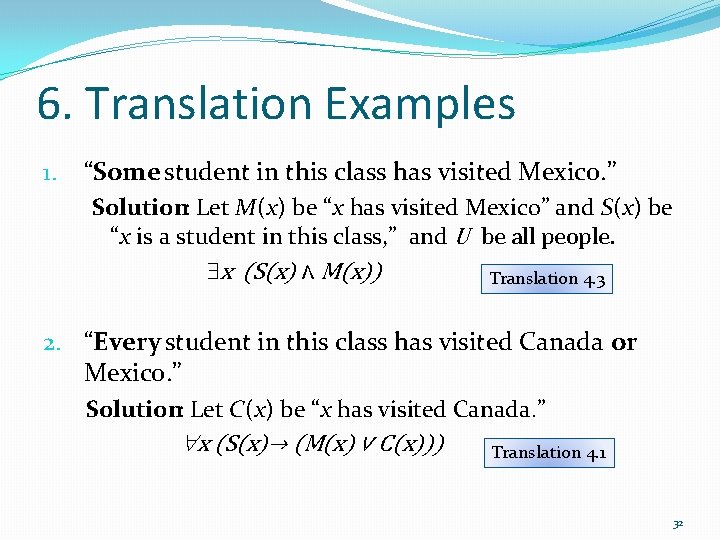

6. Translation Examples 1. “Some student in this class has visited Mexico. ” Solution: Let M(x) be “x has visited Mexico” and S(x) be “x is a student in this class, ” and U be all people. x (S(x) ∧ M(x)) Translation 4. 3 2. “Every student in this class has visited Canada or Mexico. ” Solution: Let C(x) be “x has visited Canada. ” x (S(x)→ (M(x) ∨ C(x))) Translation 4. 1 32

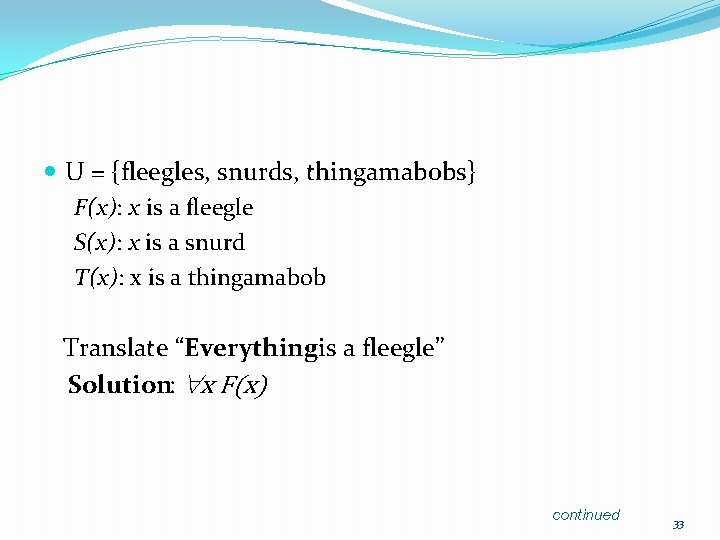

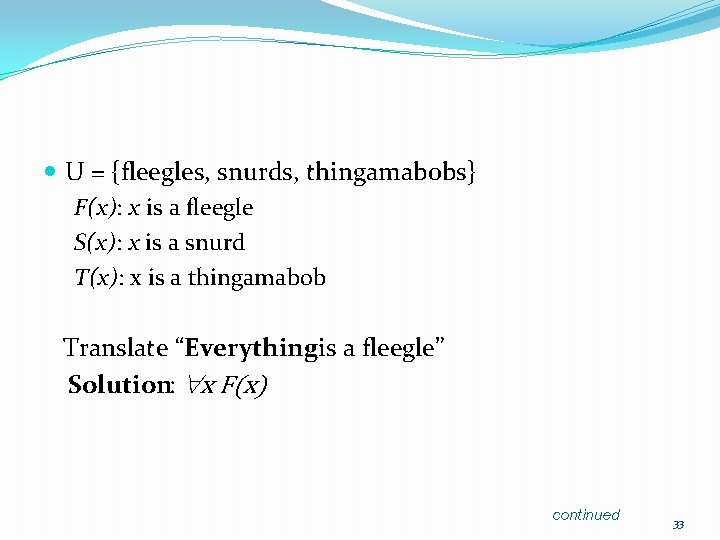

U = {fleegles, snurds, thingamabobs} F(x): x is a fleegle S(x): x is a snurd T(x): x is a thingamabob Translate “Everythingis a fleegle” Solution: x F(x) continued 33

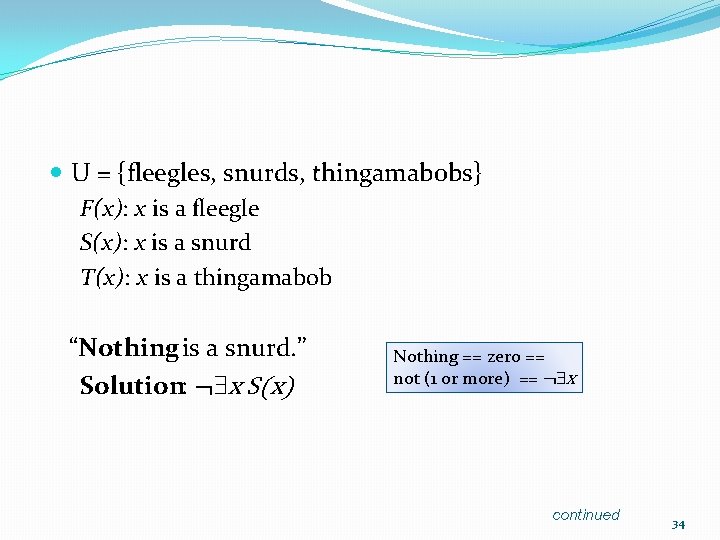

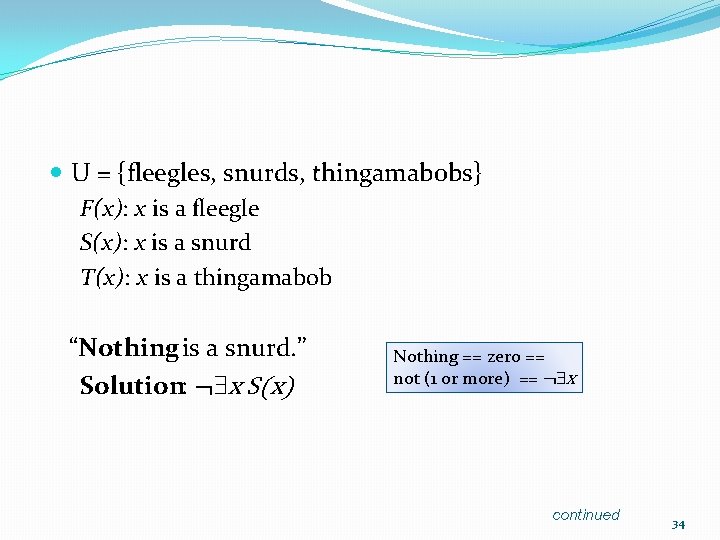

U = {fleegles, snurds, thingamabobs} F(x): x is a fleegle S(x): x is a snurd T(x): x is a thingamabob “Nothing is a snurd. ” Solution: ¬ x S(x) Nothing == zero == not (1 or more) == ¬ x continued 34

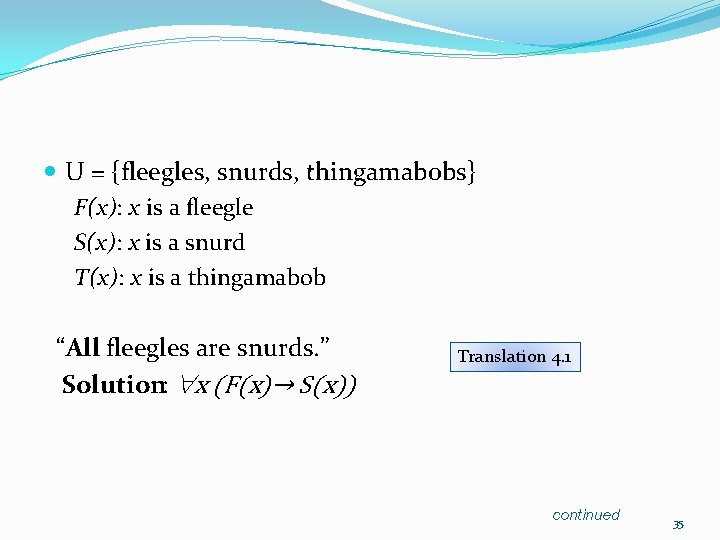

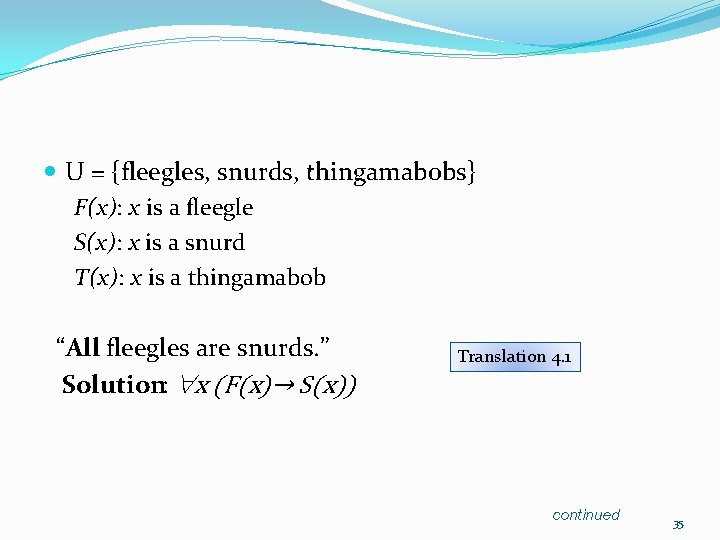

U = {fleegles, snurds, thingamabobs} F(x): x is a fleegle S(x): x is a snurd T(x): x is a thingamabob “All fleegles are snurds. ” Solution: x (F(x)→ S(x)) Translation 4. 1 continued 35

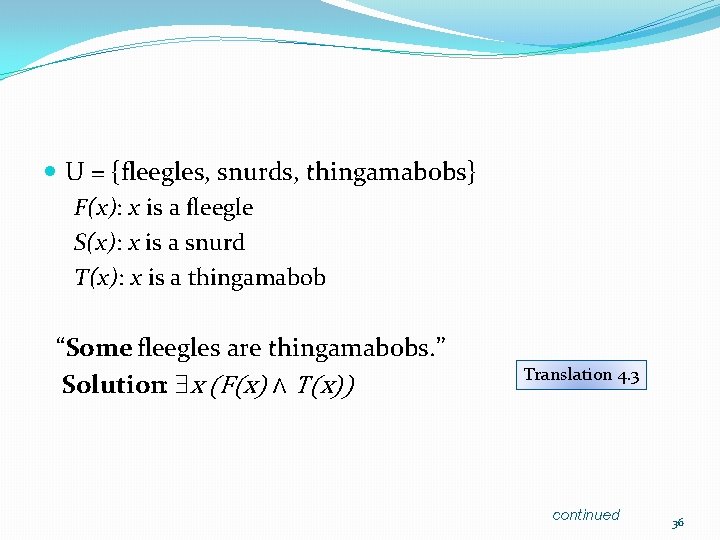

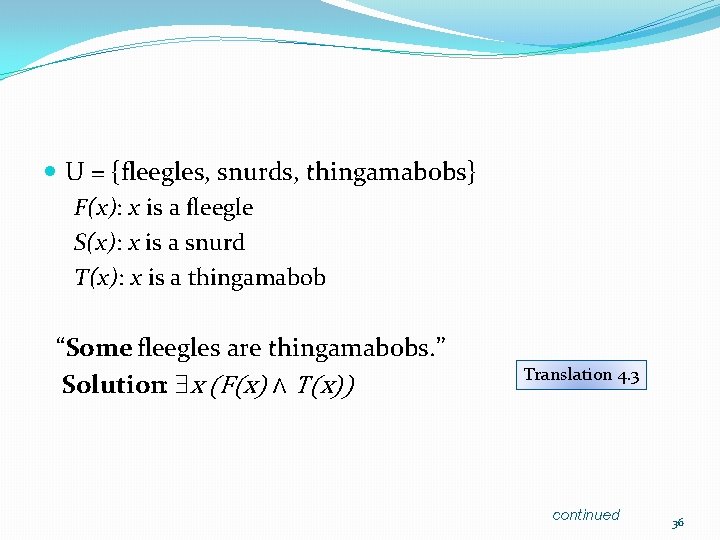

U = {fleegles, snurds, thingamabobs} F(x): x is a fleegle S(x): x is a snurd T(x): x is a thingamabob “Some fleegles are thingamabobs. ” Solution: x (F(x) ∧ T(x)) Translation 4. 3 continued 36

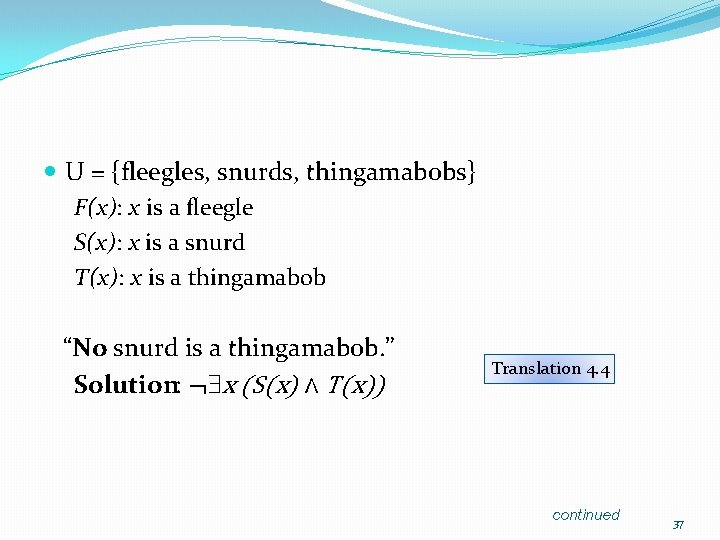

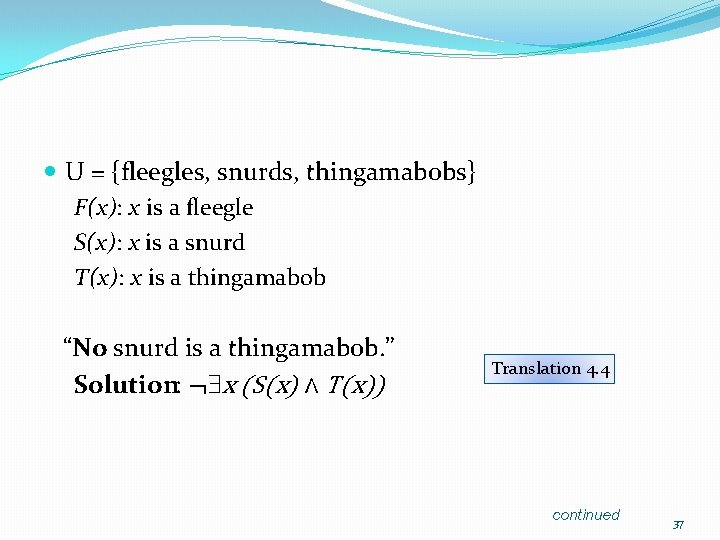

U = {fleegles, snurds, thingamabobs} F(x): x is a fleegle S(x): x is a snurd T(x): x is a thingamabob “No snurd is a thingamabob. ” Solution: ¬ x (S(x) ∧ T(x)) Translation 4. 4 continued 37

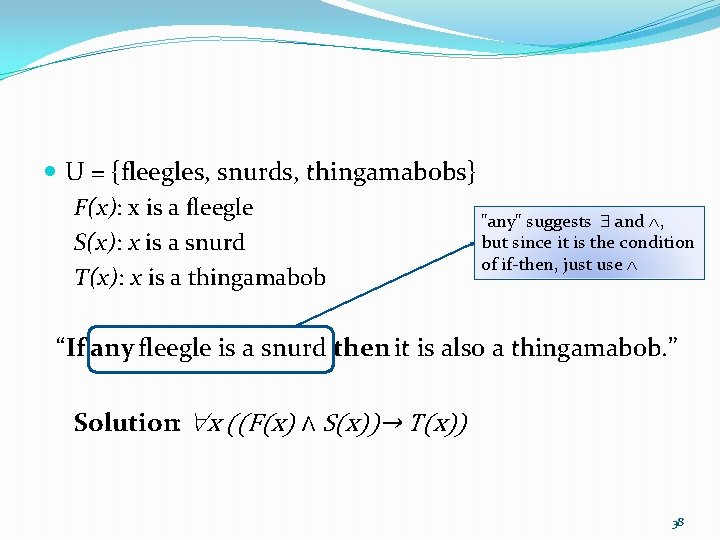

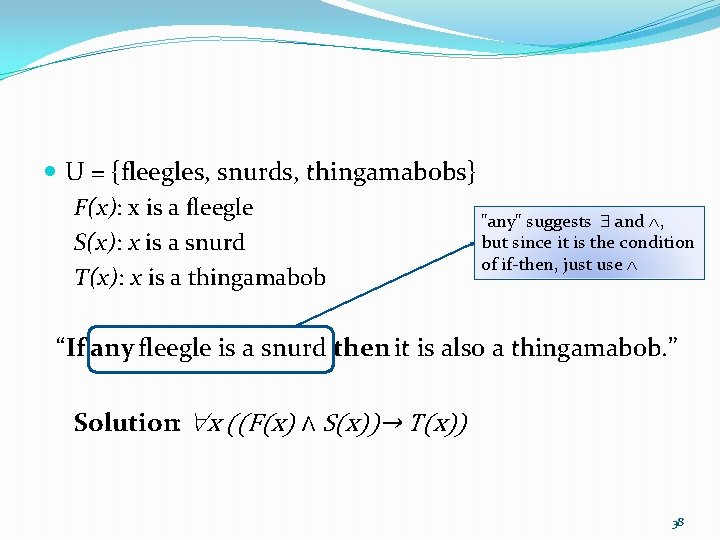

U = {fleegles, snurds, thingamabobs} F(x): x is a fleegle "any" suggests and , but since it is the condition S(x): x is a snurd of if-then, just use T(x): x is a thingamabob “If any fleegle is a snurd then it is also a thingamabob. ” Solution: x ((F(x) ∧ S(x))→ T(x)) 38

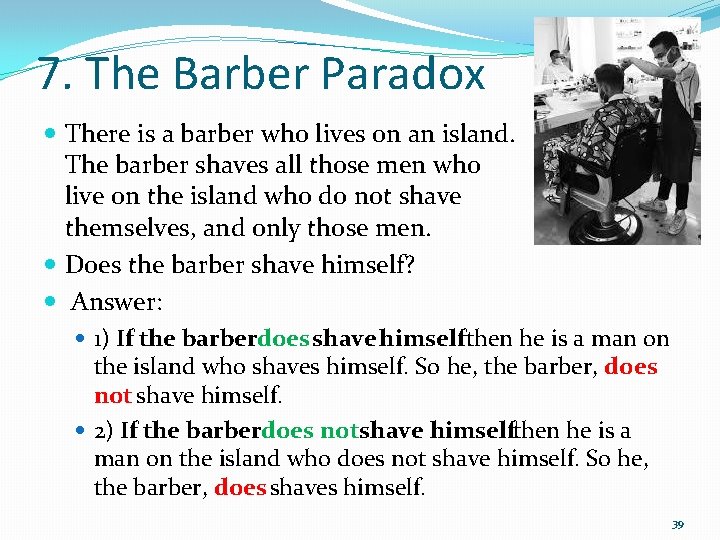

7. The Barber Paradox There is a barber who lives on an island. The barber shaves all those men who live on the island who do not shave themselves, and only those men. Does the barber shave himself? Answer: 1) If the barberdoes shave himselfthen he is a man on the island who shaves himself. So he, the barber, does not shave himself. 2) If the barberdoes notshave himselfthen he is a man on the island who does not shave himself. So he, the barber, does shaves himself. 39

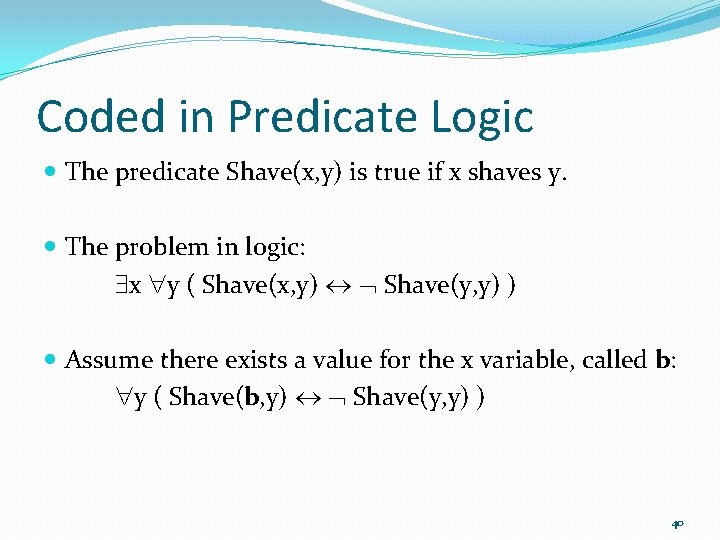

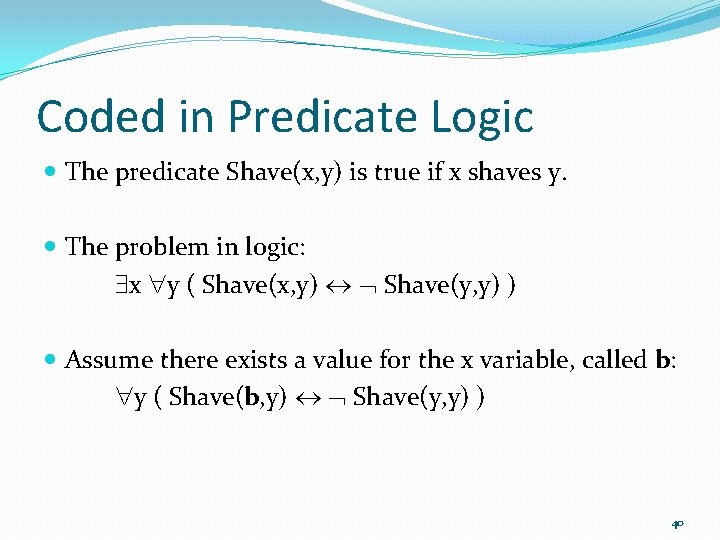

Coded in Predicate Logic The predicate Shave(x, y) is true if x shaves y. The problem in logic: x y ( Shave(x, y) Shave(y, y) ) Assume there exists a value for the x variable, called b: y ( Shave(b, y) Shave(y, y) ) 40

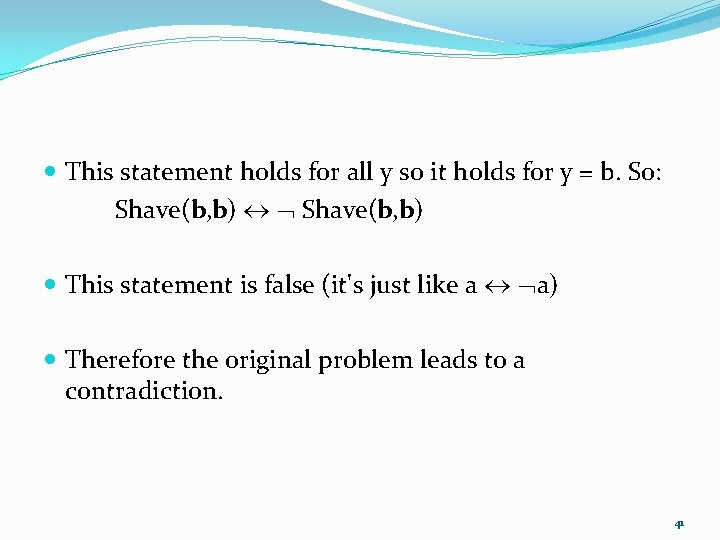

This statement holds for all y so it holds for y = b. So: Shave(b, b) This statement is false (it's just like a a) Therefore the original problem leads to a contradiction. 41

8. More Information • See the "Translation Tips" file on the course website • goes into more detail about English translations • Discrete Mathematics and its Applications Kenneth H. Rosen Mc. Graw Hill, 2007 , 7 th edition • chapter 1, section 1. 4 42