Disclosing personal information on social networking sites and

- Slides: 1

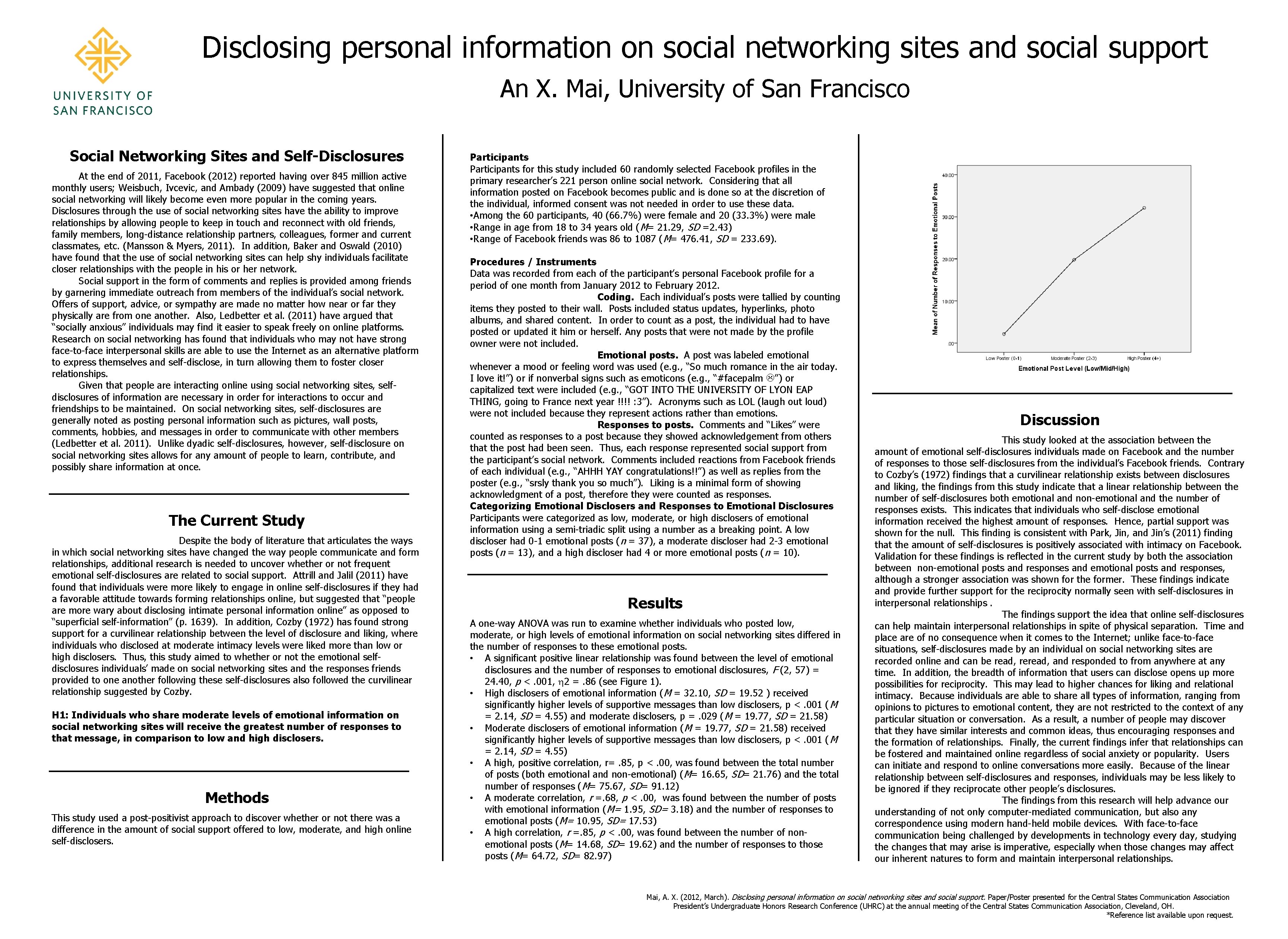

Disclosing personal information on social networking sites and social support An X. Mai, University of San Francisco Social Networking Sites and Self-Disclosures At the end of 2011, Facebook (2012) reported having over 845 million active monthly users; Weisbuch, Ivcevic, and Ambady (2009) have suggested that online social networking will likely become even more popular in the coming years. Disclosures through the use of social networking sites have the ability to improve relationships by allowing people to keep in touch and reconnect with old friends, family members, long-distance relationship partners, colleagues, former and current classmates, etc. (Mansson & Myers, 2011). In addition, Baker and Oswald (2010) have found that the use of social networking sites can help shy individuals facilitate closer relationships with the people in his or her network. Social support in the form of comments and replies is provided among friends by garnering immediate outreach from members of the individual’s social network. Offers of support, advice, or sympathy are made no matter how near or far they physically are from one another. Also, Ledbetter et al. (2011) have argued that “socially anxious” individuals may find it easier to speak freely on online platforms. Research on social networking has found that individuals who may not have strong face-to-face interpersonal skills are able to use the Internet as an alternative platform to express themselves and self-disclose, in turn allowing them to foster closer relationships. Given that people are interacting online using social networking sites, selfdisclosures of information are necessary in order for interactions to occur and friendships to be maintained. On social networking sites, self-disclosures are generally noted as posting personal information such as pictures, wall posts, comments, hobbies, and messages in order to communicate with other members (Ledbetter et al. 2011). Unlike dyadic self-disclosures, however, self-disclosure on social networking sites allows for any amount of people to learn, contribute, and possibly share information at once. The Current Study Despite the body of literature that articulates the ways in which social networking sites have changed the way people communicate and form relationships, additional research is needed to uncover whether or not frequent emotional self-disclosures are related to social support. Attrill and Jalil (2011) have found that individuals were more likely to engage in online self-disclosures if they had a favorable attitude towards forming relationships online, but suggested that “people are more wary about disclosing intimate personal information online” as opposed to “superficial self-information” (p. 1639). In addition, Cozby (1972) has found strong support for a curvilinear relationship between the level of disclosure and liking, where individuals who disclosed at moderate intimacy levels were liked more than low or high disclosers. Thus, this study aimed to whether or not the emotional selfdisclosures individuals’ made on social networking sites and the responses friends provided to one another following these self-disclosures also followed the curvilinear relationship suggested by Cozby. H 1: Individuals who share moderate levels of emotional information on social networking sites will receive the greatest number of responses to that message, in comparison to low and high disclosers. Methods This study used a post-positivist approach to discover whether or not there was a difference in the amount of social support offered to low, moderate, and high online self-disclosers. Participants for this study included 60 randomly selected Facebook profiles in the primary researcher’s 221 person online social network. Considering that all information posted on Facebook becomes public and is done so at the discretion of the individual, informed consent was not needed in order to use these data. • Among the 60 participants, 40 (66. 7%) were female and 20 (33. 3%) were male • Range in age from 18 to 34 years old (M= 21. 29, SD =2. 43) • Range of Facebook friends was 86 to 1087 (M= 476. 41, SD = 233. 69). Procedures / Instruments Data was recorded from each of the participant’s personal Facebook profile for a period of one month from January 2012 to February 2012. Coding. Each individual’s posts were tallied by counting items they posted to their wall. Posts included status updates, hyperlinks, photo albums, and shared content. In order to count as a post, the individual had to have posted or updated it him or herself. Any posts that were not made by the profile owner were not included. Emotional posts. A post was labeled emotional whenever a mood or feeling word was used (e. g. , “So much romance in the air today. I love it!”) or if nonverbal signs such as emoticons (e. g. , “#facepalm ”) or capitalized text were included (e. g. , “GOT INTO THE UNIVERSITY OF LYON EAP THING, going to France next year !!!! : 3”). Acronyms such as LOL (laugh out loud) were not included because they represent actions rather than emotions. Responses to posts. Comments and “Likes” were counted as responses to a post because they showed acknowledgement from others that the post had been seen. Thus, each response represented social support from the participant’s social network. Comments included reactions from Facebook friends of each individual (e. g. , “AHHH YAY congratulations!!”) as well as replies from the poster (e. g. , “srsly thank you so much”). Liking is a minimal form of showing acknowledgment of a post, therefore they were counted as responses. Categorizing Emotional Disclosers and Responses to Emotional Disclosures Participants were categorized as low, moderate, or high disclosers of emotional information using a semi-triadic split using a number as a breaking point. A low discloser had 0 -1 emotional posts (n = 37), a moderate discloser had 2 -3 emotional posts (n = 13), and a high discloser had 4 or more emotional posts ( n = 10). Results A one-way ANOVA was run to examine whether individuals who posted low, moderate, or high levels of emotional information on social networking sites differed in the number of responses to these emotional posts. • A significant positive linear relationship was found between the level of emotional disclosures and the number of responses to emotional disclosures, F (2, 57) = 24. 40, p <. 001, 2 =. 86 (see Figure 1). • High disclosers of emotional information (M = 32. 10, SD = 19. 52 ) received significantly higher levels of supportive messages than low disclosers, p <. 001 ( M = 2. 14, SD = 4. 55) and moderate disclosers, p =. 029 (M = 19. 77, SD = 21. 58) • Moderate disclosers of emotional information (M = 19. 77, SD = 21. 58) received significantly higher levels of supportive messages than low disclosers, p <. 001 ( M = 2. 14, SD = 4. 55) • A high, positive correlation, r=. 85, p <. 00, was found between the total number of posts (both emotional and non-emotional) (M= 16. 65, SD= 21. 76) and the total number of responses (M= 75. 67, SD= 91. 12) • A moderate correlation, r =. 68, p <. 00, was found between the number of posts with emotional information (M= 1. 95, SD= 3. 18) and the number of responses to emotional posts (M= 10. 95, SD= 17. 53) • A high correlation, r =. 85, p <. 00, was found between the number of nonemotional posts (M= 14. 68, SD= 19. 62) and the number of responses to those posts (M= 64. 72, SD= 82. 97) Discussion This study looked at the association between the amount of emotional self-disclosures individuals made on Facebook and the number of responses to those self-disclosures from the individual’s Facebook friends. Contrary to Cozby’s (1972) findings that a curvilinear relationship exists between disclosures and liking, the findings from this study indicate that a linear relationship between the number of self-disclosures both emotional and non-emotional and the number of responses exists. This indicates that individuals who self-disclose emotional information received the highest amount of responses. Hence, partial support was shown for the null. This finding is consistent with Park, Jin, and Jin’s (2011) finding that the amount of self-disclosures is positively associated with intimacy on Facebook. Validation for these findings is reflected in the current study by both the association between non-emotional posts and responses and emotional posts and responses, although a stronger association was shown for the former. These findings indicate and provide further support for the reciprocity normally seen with self-disclosures in interpersonal relationships. The findings support the idea that online self-disclosures can help maintain interpersonal relationships in spite of physical separation. Time and place are of no consequence when it comes to the Internet; unlike face-to-face situations, self-disclosures made by an individual on social networking sites are recorded online and can be read, reread, and responded to from anywhere at any time. In addition, the breadth of information that users can disclose opens up more possibilities for reciprocity. This may lead to higher chances for liking and relational intimacy. Because individuals are able to share all types of information, ranging from opinions to pictures to emotional content, they are not restricted to the context of any particular situation or conversation. As a result, a number of people may discover that they have similar interests and common ideas, thus encouraging responses and the formation of relationships. Finally, the current findings infer that relationships can be fostered and maintained online regardless of social anxiety or popularity. Users can initiate and respond to online conversations more easily. Because of the linear relationship between self-disclosures and responses, individuals may be less likely to be ignored if they reciprocate other people’s disclosures. The findings from this research will help advance our understanding of not only computer-mediated communication, but also any correspondence using modern hand-held mobile devices. With face-to-face communication being challenged by developments in technology every day, studying the changes that may arise is imperative, especially when those changes may affect our inherent natures to form and maintain interpersonal relationships. Mai, A. X. (2012, March). Disclosing personal information on social networking sites and social support. Paper/Poster presented for the Central States Communication Association President’s Undergraduate Honors Research Conference (UHRC) at the annual meeting of the Central States Communication Association, Cleveland, OH. *Reference list available upon request.