Digestive System Diseases Ruminants Actinomycosis Lumpy jaw l

- Slides: 55

Digestive System Diseases Ruminants

Actinomycosis “Lumpy jaw” l l Actinomyces spp are normal flora of the oral and nasopharyngeal mucous membranes. Members of the genus Actinomyces are gram-positive, non-acid -fast rods A bovis is the etiologic agent of lumpy jaw in cattle

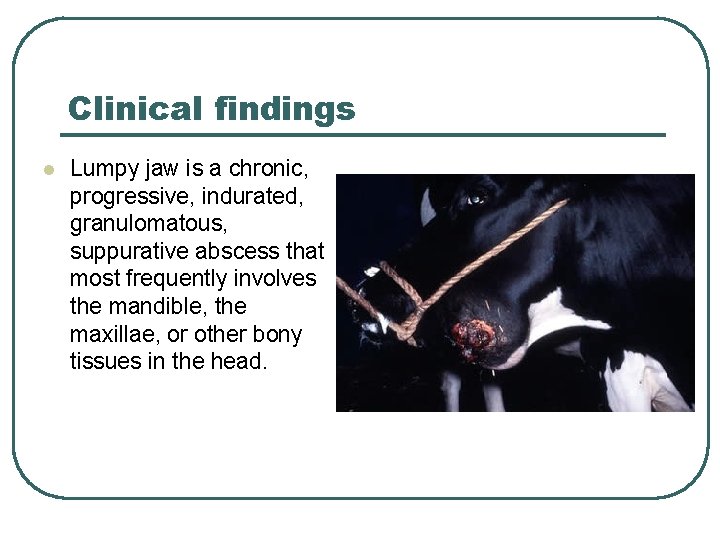

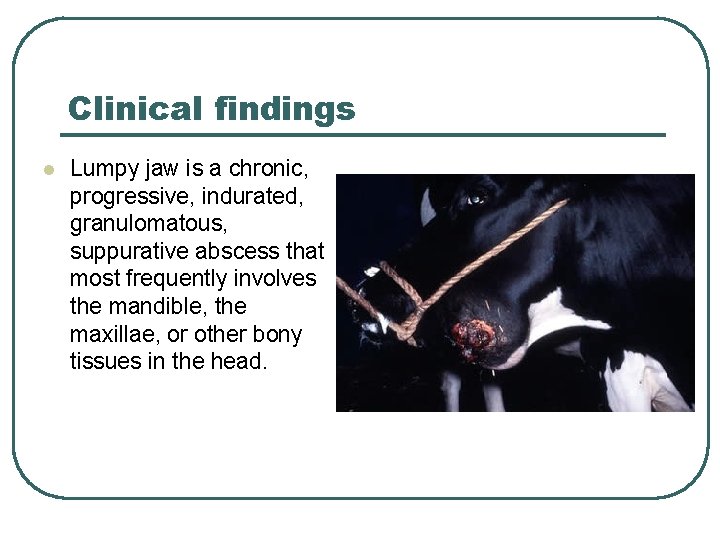

Clinical findings l Lumpy jaw is a chronic, progressive, indurated, granulomatous, suppurative abscess that most frequently involves the mandible, the maxillae, or other bony tissues in the head.

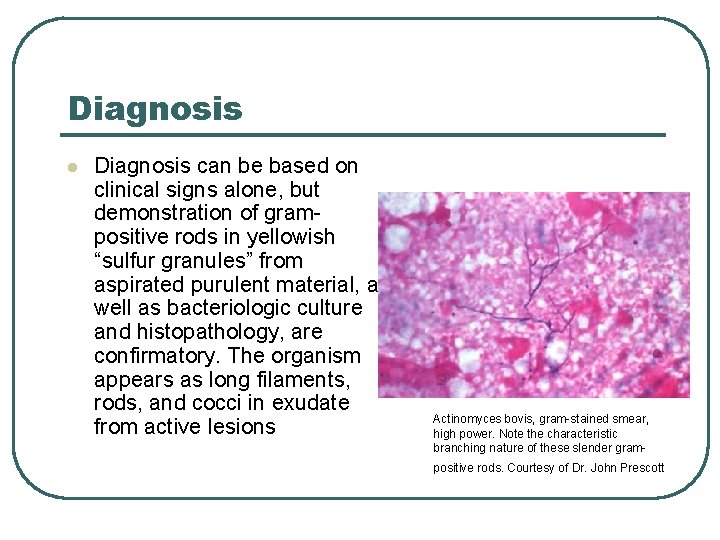

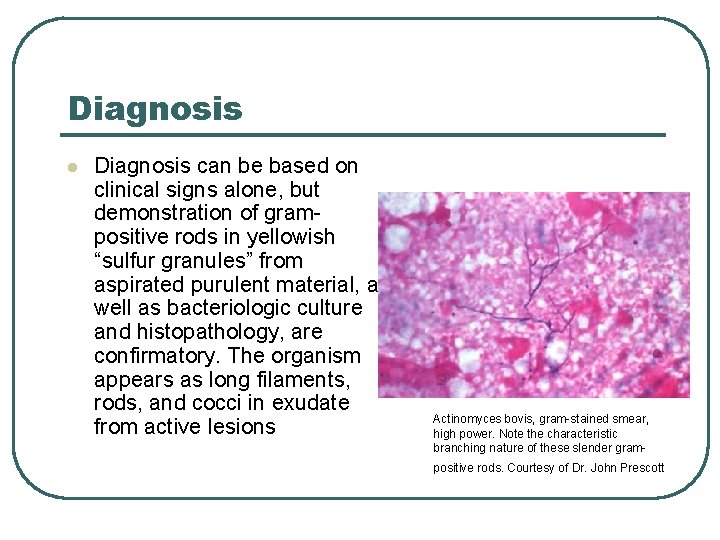

Diagnosis l Diagnosis can be based on clinical signs alone, but demonstration of grampositive rods in yellowish “sulfur granules” from aspirated purulent material, as well as bacteriologic culture and histopathology, are confirmatory. The organism appears as long filaments, rods, and cocci in exudate from active lesions Actinomyces bovis, gram-stained smear, high power. Note the characteristic branching nature of these slender grampositive rods. Courtesy of Dr. John Prescott

Treatment l l l is rarely successful in chronic cases in which bone is extensively involved, due to poor penetration of antibacterial agents into the site of infection. In less advanced cases, penicillin may be effective. Systemic treatment with potassium iodide has been used successfully in the past, but is no longer recommended due to food safety issues.

Actinobacillosis l Actinobacillosis, caused by gramnegative coccobacilli in the genus Actinobacillus (Actinobacillus lignieresii) , may present in several different forms, depending on the specific agent and the host. Soft- tissue infections are common, and lymph node involvement is frequently a step in systemic spread; adjacent bony tissue may also be affected.

Grain Overload (Lactic acidosis, Carbohydrate engorgement, Rumen impaction) l Grain overload is an acute disease of ruminants that is characterized by indigestion, rumen stasis, dehydration, acidosis, toxemia, incoordination, collapse, and frequently death.

Etiology and Pathogenesis: l l l The disease is most common in cattle that accidentally gain access to large quantities of readily digestible carbohydrates, particularly grain. It also is common in feedlot cattle when they are introduced to heavy grain diets too quickly. Ingestion of toxic amounts of highly fermentable carbohydrates is followed within 2 -6 hr by a change in the microbial population in the rumen. The number of grampositive bacteria ( Streptococcus bovis ) increases markedly, which results in the production of large quantities of lactic acid. The rumen p. H falls to ≤ 5. The lactic acid causes a chemical rumenitis, and its absorption results in lactic acidosis. In addition to acidosis and dehydration, the pathophysiologic consequences are hemoconcentration, cardiovascular collapse, renal failure, muscular weakness, shock, and death

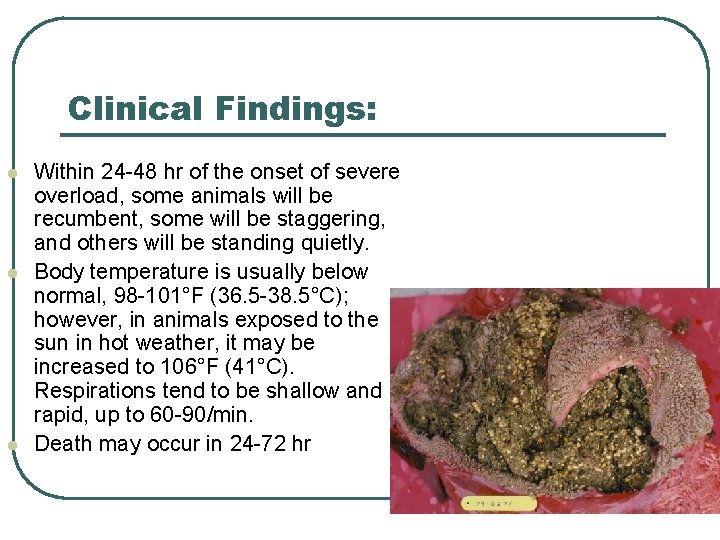

Clinical Findings: l l l Within 24 -48 hr of the onset of severe overload, some animals will be recumbent, some will be staggering, and others will be standing quietly. Body temperature is usually below normal, 98 -101°F (36. 5 -38. 5°C); however, in animals exposed to the sun in hot weather, it may be increased to 106°F (41°C). Respirations tend to be shallow and rapid, up to 60 -90/min. Death may occur in 24 -72 hr

Diagnosis l The diagnosis is usually obvious if the history is available. It may be confirmed by the clinical findings, a low ruminal p. H (<5), and examining the microflora of the rumen for the presence of live protozoa

Treatment: l l For all cattle suspected of having eaten large quantities of concentrate, it is important to restrict water intake for the first 18 -24 hr. If overload is serious, slaughter for salvage should be considered. Emptying the rumen should be followed by rumen inoculation. Initially, over a period of ~30 min, 5% sodium bicarbonate solution should be given IV (5 L/450 kg). During the next 6 -12 hr, a balanced electrolyte solution, or a 1. 3% solution of sodium bicarbonate in saline, may be given IV, up to as much as 60 L/450 kg body wt. In less severe cases, emptying the rumen is unnecessary. In these, magnesium hydroxide (500 g/450 kg body wt) should be added to warm water, pumped into the rumen

Prevention l Accidental access to concentrates for which the cattle have developed an appetite, in quantities to which they are unaccustomed, should be avoided

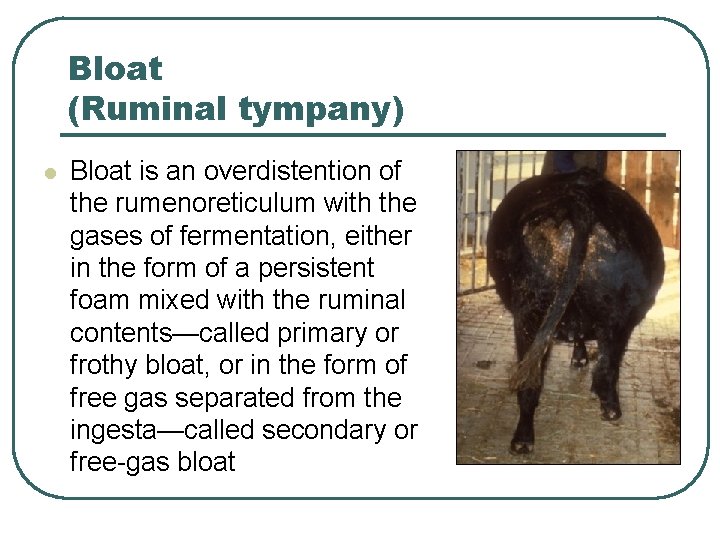

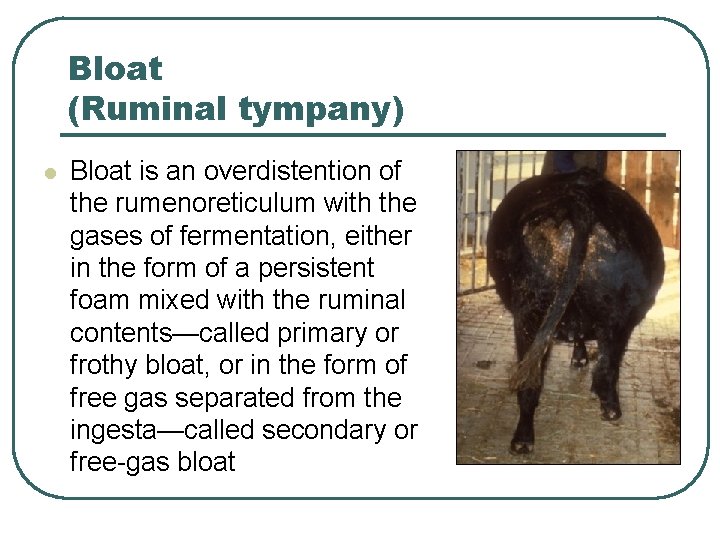

Bloat (Ruminal tympany) l Bloat is an overdistention of the rumenoreticulum with the gases of fermentation, either in the form of a persistent foam mixed with the ruminal contents—called primary or frothy bloat, or in the form of free gas separated from the ingesta—called secondary or free-gas bloat

Etiology and Pathogenesis l l In primary ruminal tympany, or frothy bloat, the cause is entrapment of the normal gases of fermentation in a stable foam. Coalescence of the small gas bubbles is inhibited, and intraruminal pressure increases because eructation cannot occur. Several factors, both animal and plant, influence the formation of a stable foam. Bloat is most common in animals grazing legume or legume-dominant pastures, particularly alfalfa, ladino, and red and white clovers, but also is seen with grazing of young green cereal crops, rape, kale, turnips, and legume vegetable crops

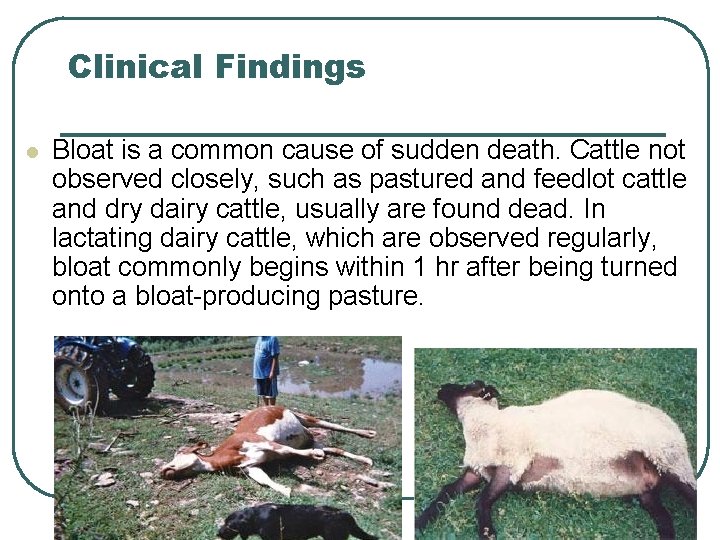

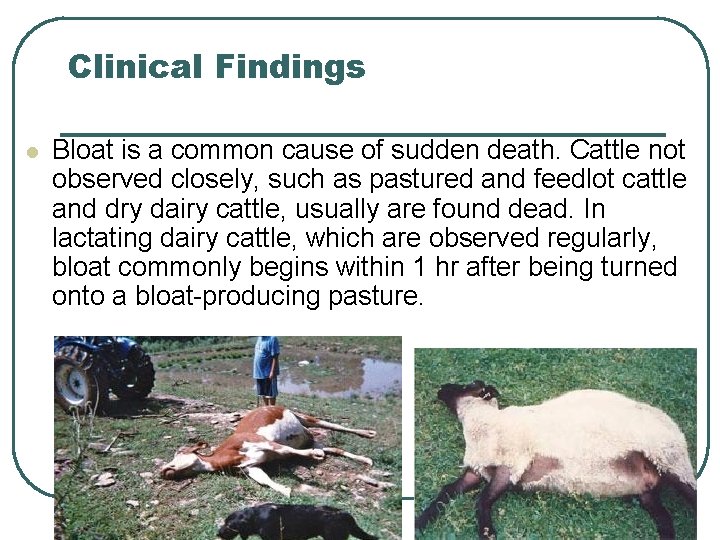

Clinical Findings l Bloat is a common cause of sudden death. Cattle not observed closely, such as pastured and feedlot cattle and dry dairy cattle, usually are found dead. In lactating dairy cattle, which are observed regularly, bloat commonly begins within 1 hr after being turned onto a bloat-producing pasture.

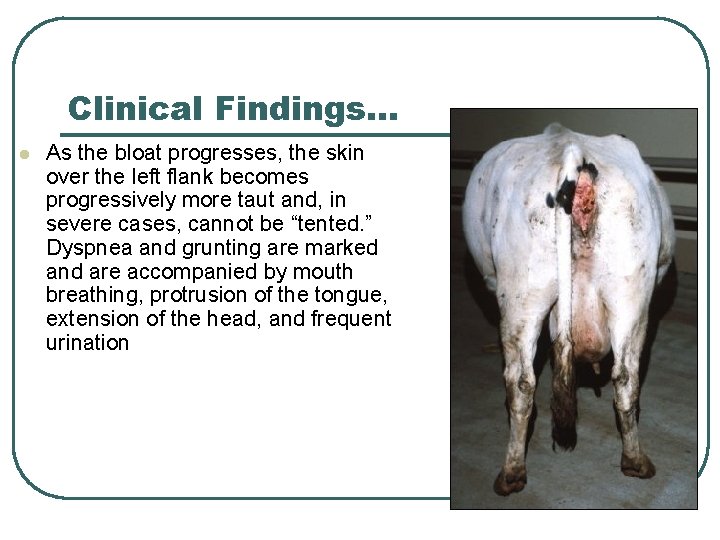

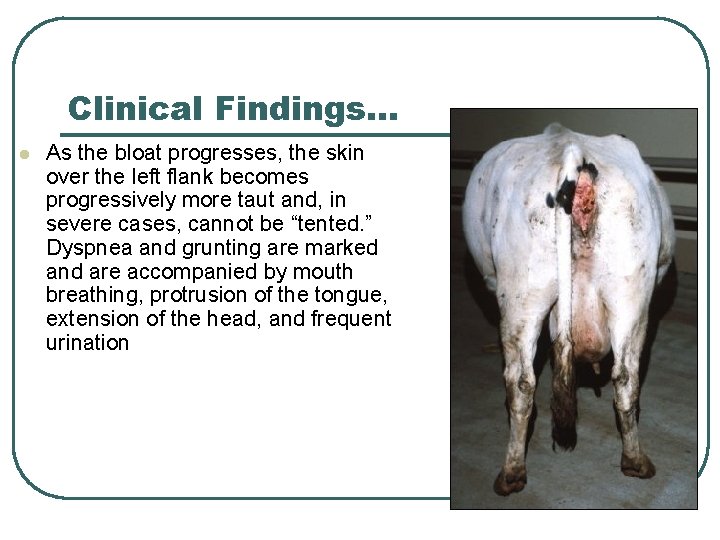

Clinical Findings… l As the bloat progresses, the skin over the left flank becomes progressively more taut and, in severe cases, cannot be “tented. ” Dyspnea and grunting are marked and are accompanied by mouth breathing, protrusion of the tongue, extension of the head, and frequent urination

Diagnosis: Usually, the clinical diagnosis of frothy bloat is obvious. The causes of secondary bloat must be ascertained by clinical examination to determine the cause of the failure of eructation

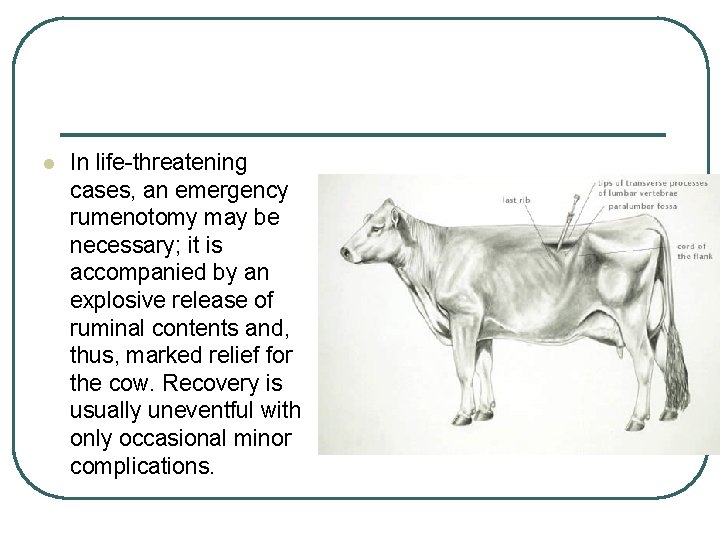

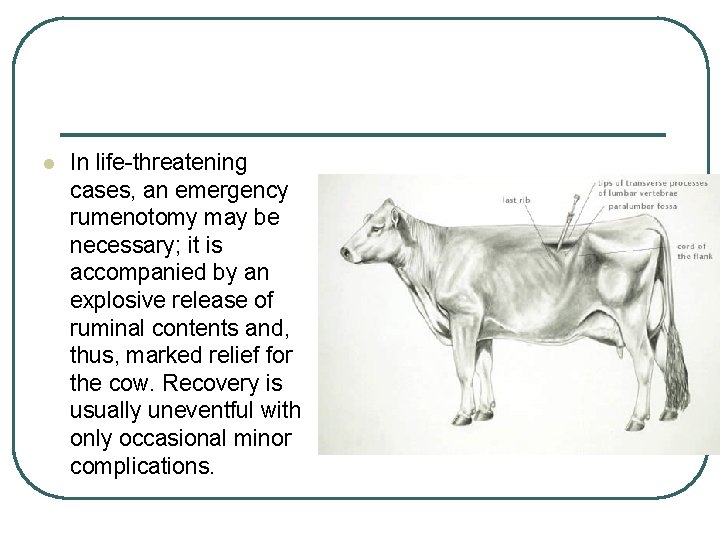

l In life-threatening cases, an emergency rumenotomy may be necessary; it is accompanied by an explosive release of ruminal contents and, thus, marked relief for the cow. Recovery is usually uneventful with only occasional minor complications.

Control and Prevention: l Prevention of pasture bloat can be difficult. Management practices that have been used to reduce the risk of bloat include feeding hay before turning cattle on pasture, maintaining grass dominance in the sward, or using strip grazing to restrict intake,

Traumatic Reticuloperitonitis (Hardware disease, Traumatic gastritis) l Traumatic reticuloperitonitis develops as a consequence of perforation of the reticulum. It is important in differential diagnosis of other diseases marked by stasis of the GI tract because it causes similar signs

Etiology: l l Swallowed metallic objects, such as nails or pieces of wire, fall directly into the reticulum or pass into the rumen and are subsequently carried over the ruminoreticular fold into the cranioventral part of the reticulum by ruminal contractions. The reticulo-omasal orifice is elevated above the floor, which tends to retain heavy objects. Perforation of the wall of the reticulum allows leakage of ingesta and bacteria, which contaminates the peritoneal cavity

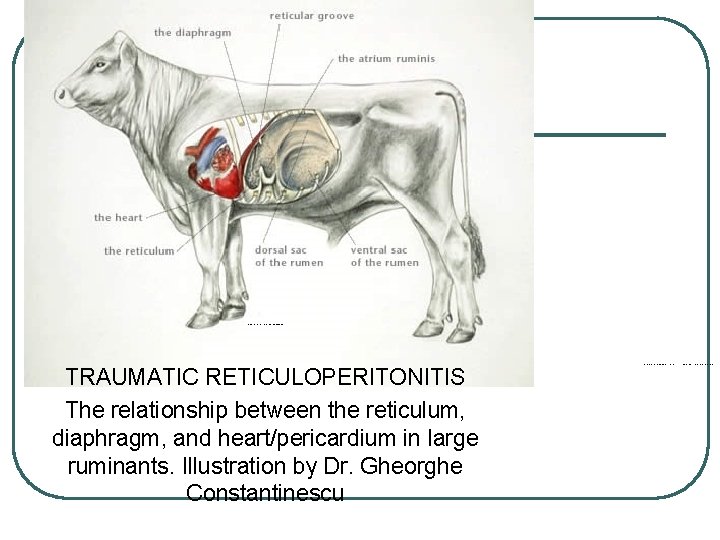

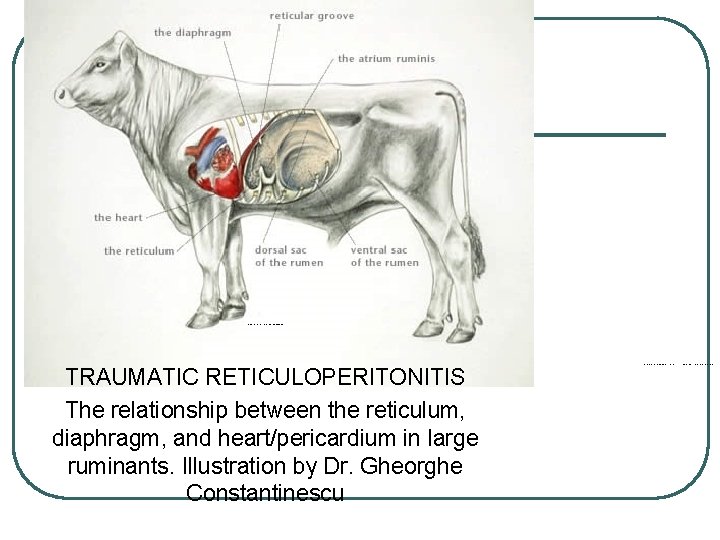

TRAUMATIC RETICULOPERITONITIS The relationship between the reticulum, diaphragm, and heart/pericardium in large ruminants. Illustration by Dr. Gheorghe Constantinescu The relationship between the reticulum, diaphragm, and heart/pericardium in

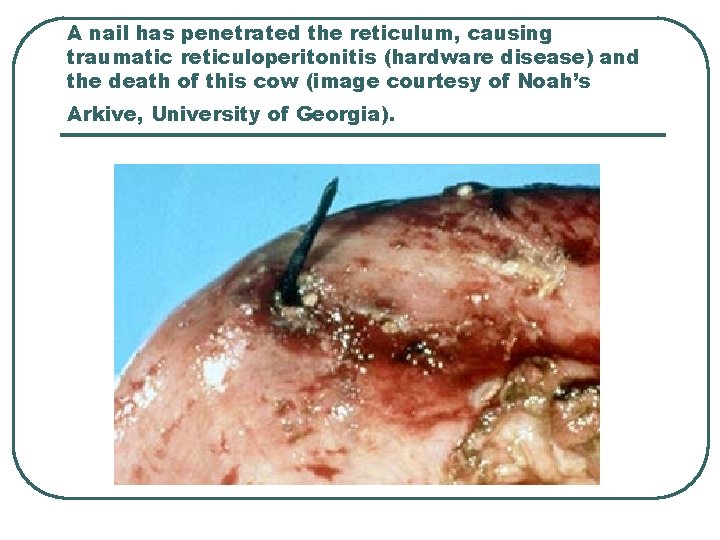

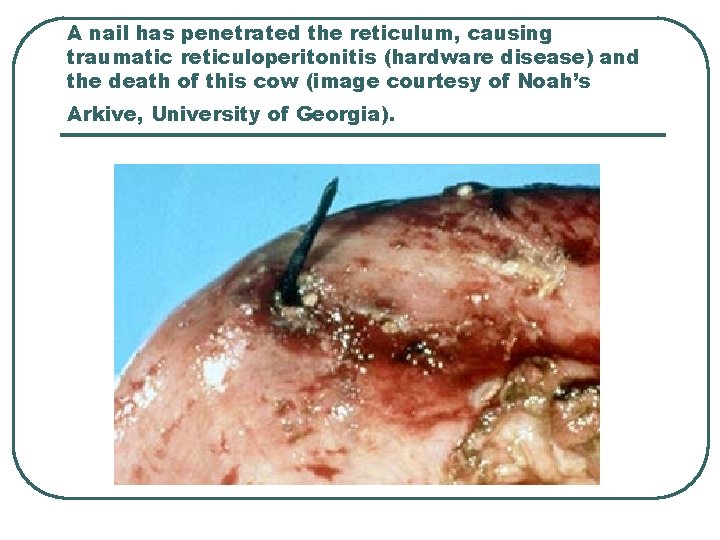

A nail has penetrated the reticulum, causing traumatic reticuloperitonitis (hardware disease) and the death of this cow (image courtesy of Noah’s Arkive, University of Georgia).

Clinical Findings: l The initial attack is characterized by sudden onset of ruminoreticular atony and a sharp fall in milk production. Fecal output is decreased.

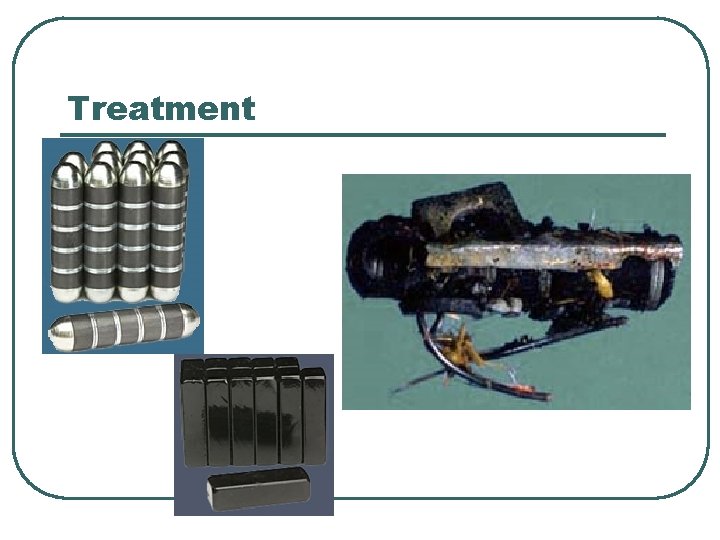

Treatment

Treatment…. l Affected cattle should also receive 3 -7 days of systemic antibiotic therapy (penicillin, ceftiofur, ampicillin, or tetracycline), stall rest and other supportive therapy as indicated. Affected cattle should be re-evaluated in 48 -72 hours. If a magnet is already in place or conservative therapy is not successful, an exploratory laparotomy/rumenotomy is indicated for removal of the foreign body

Diarrhea Johne’s Disease

What is Johne’s Disease? (paratuberculosis) • Pronounced “YO-KNEES”, it is a chronic bacterial infection of the lower small intestine of ruminants caused by the bacterium, Mycobacterium paratuberculosis • It has been diagnosed in cattle, sheep, goats, and camelids and currently no treatment or cure exists • The disease can be spread through contaminated manure, soil, and water • When ingested, it infects the small intestine causing the lining to thicken and be unable to digest nutrients

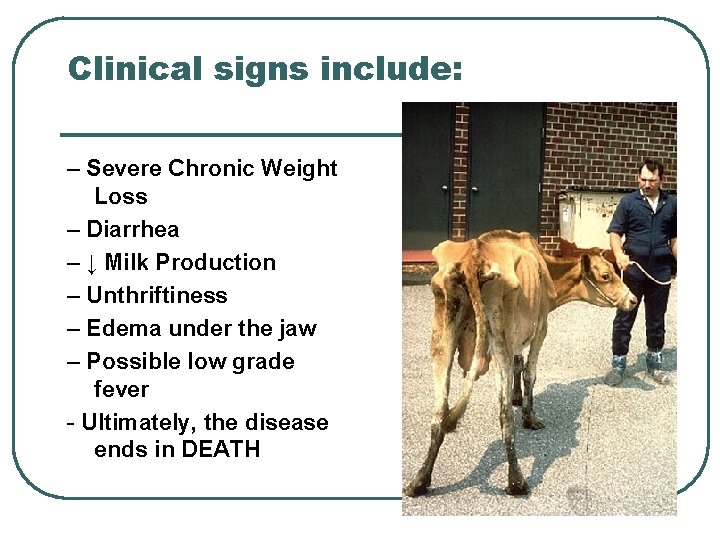

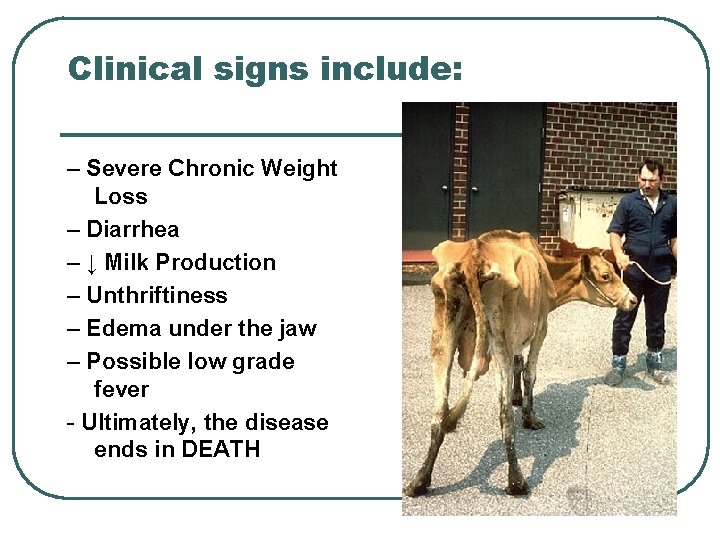

Clinical signs include: – Severe Chronic Weight Loss – Diarrhea – ↓ Milk Production – Unthriftiness – Edema under the jaw – Possible low grade fever - Ultimately, the disease ends in DEATH

How is Johne’s Spread? • Johne’s is spread through manure • Infected animals can carry the disease until death • Anything contaminated with manure • All cattle can be infected • Young calves are most susceptible • Calves can be infected by manure on teats or directly from colostrum of an infected cow

Johne’s Control Measures 1. Closed herd or purchase only Johne’s negative cattle. 2. Quarantine and test new cattle 3. Separate calves immediately 4. Routinely test • Cull infected individuals

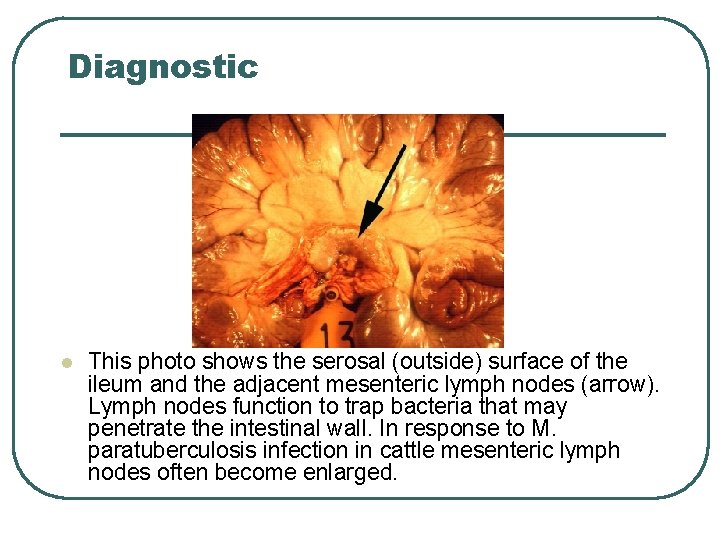

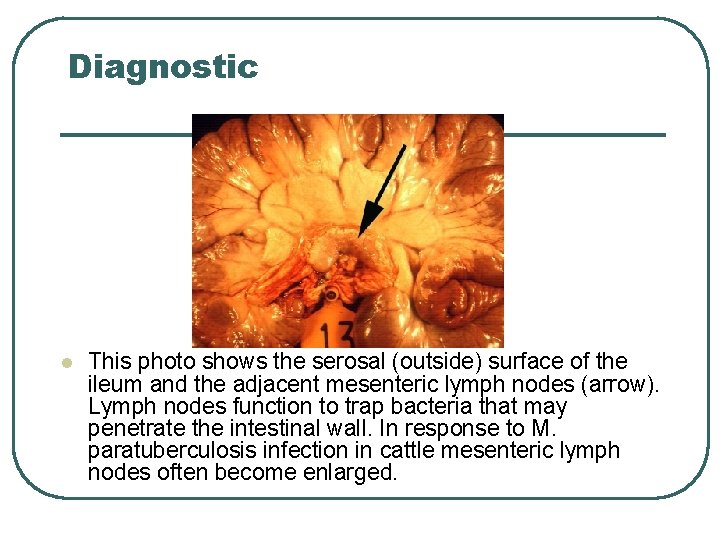

Diagnostic l This photo shows the serosal (outside) surface of the ileum and the adjacent mesenteric lymph nodes (arrow). Lymph nodes function to trap bacteria that may penetrate the intestinal wall. In response to M. paratuberculosis infection in cattle mesenteric lymph nodes often become enlarged.

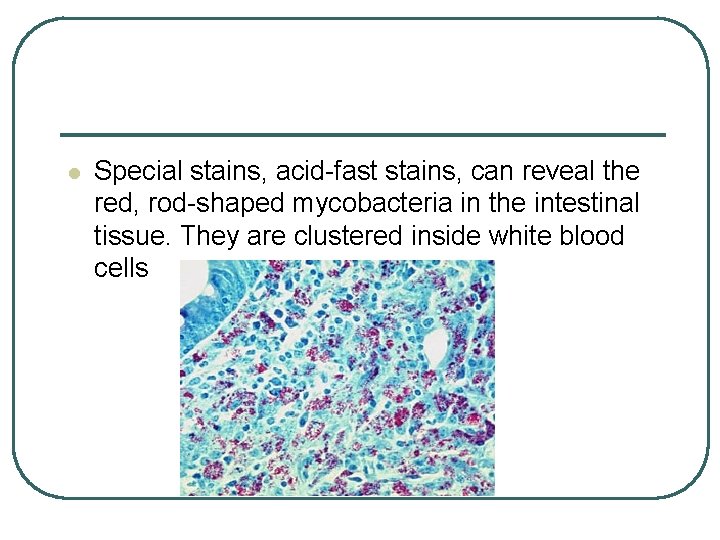

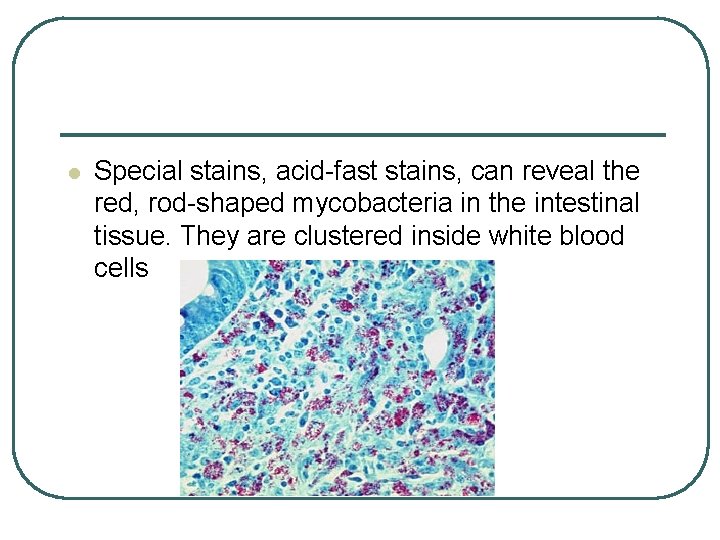

l Special stains, acid-fast stains, can reveal the red, rod-shaped mycobacteria in the intestinal tissue. They are clustered inside white blood cells

Control: l l l No satisfactory treatment is known. Control requires good sanitation and management practices aimed at limiting the exposure of young animals to the organism. A routine testing program for adults can help focus efforts in controlling the disease Vaccination not 100% safe

Salmonella

Salmonella (Salmonella newport) l Salmonella enterica serovar newport has recently been named an emerging disease by the American Association of Veterinary Laboratory Diagnosticians (AAVLD). Salmonell-osis, due to any of 2200 Salmonella serotypes (serovars) is one of the few diseases that is increasing in prevalence

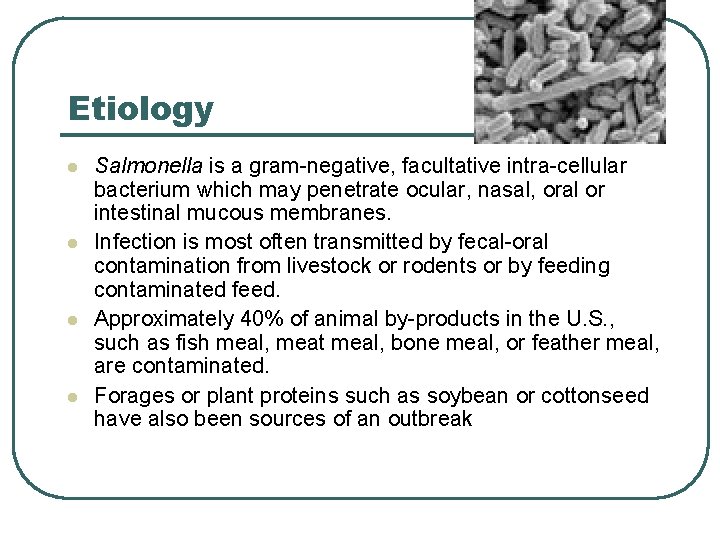

Etiology l l Salmonella is a gram-negative, facultative intra-cellular bacterium which may penetrate ocular, nasal, oral or intestinal mucous membranes. Infection is most often transmitted by fecal-oral contamination from livestock or rodents or by feeding contaminated feed. Approximately 40% of animal by-products in the U. S. , such as fish meal, meat meal, bone meal, or feather meal, are contaminated. Forages or plant proteins such as soybean or cottonseed have also been sources of an outbreak

Clinical signs: l l As with most serotypes, Salmonella spp. Infections can cause a variety of clinical signs, and infections in cattle are most commonly subclinical. Salmonella newport has been implicated most commonly with adult dairy cow diarrhea and chronic weight loss or poor production. When clinical signs are present, the most common are fever and diarrhea, although weakness, dyspnea and sudden death would also be consistent with a diagnosis of suspected salmonellosis. Diarrhea may vary from watery to mucoid with fibrin and blood. Bacteremia may occur rapidly, especially in calves under two months of age. In adult dairy cattle, septicemia, diarrhea or abortion may occur

Diagnosis: l l As gross lesions may vary greatly depending on the course and extent of infection, definitive diagnosis requires culture of the organism from feces, blood, or tissues Salmonella has traditionally been a difficult disease to treat and control, and requires an integrated herd approach. Herd serologic profiling using ELISA can be used

Treatment: l l l Broad-spectrum antibiotics are used parenterally to treat the septicemia. Initial antimicrobial therapy should be based on knowledge of the drug resistance pattern found in the area. Trimethoprim-sulfonamide combinations are often effective. Alternatives are ampicillin, fluoroquinolones, or third-generation cephalosporins. Treatment should be continued daily for up to 6 days.

Control: l l These are major problems because of carrier animals and contaminated feedstuffs. Drain swabs or milk filters may be cultured to monitor the salmonellae status of a herd. The principles of control include prevention of introduction and limitation of spread within a herd. Ensuring that feed supplies are free of salmonellae depends on the integrity of the source.

Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus

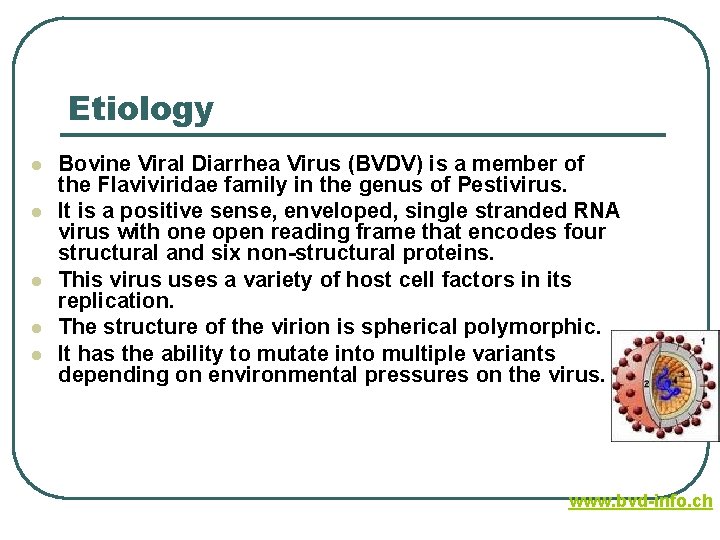

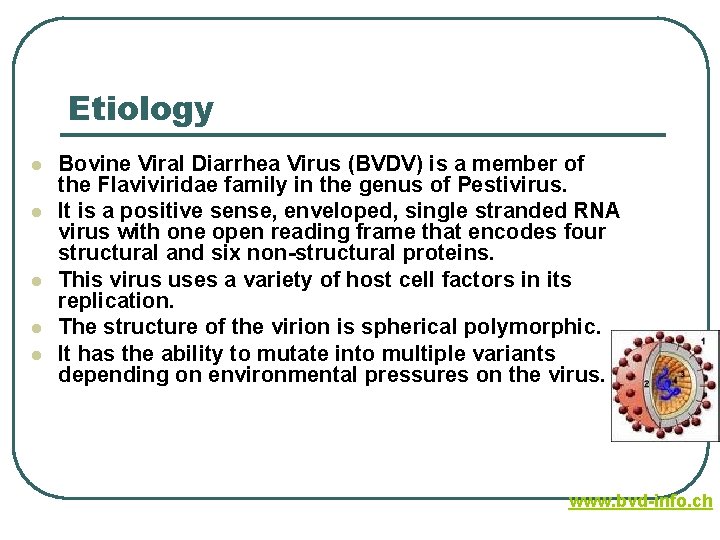

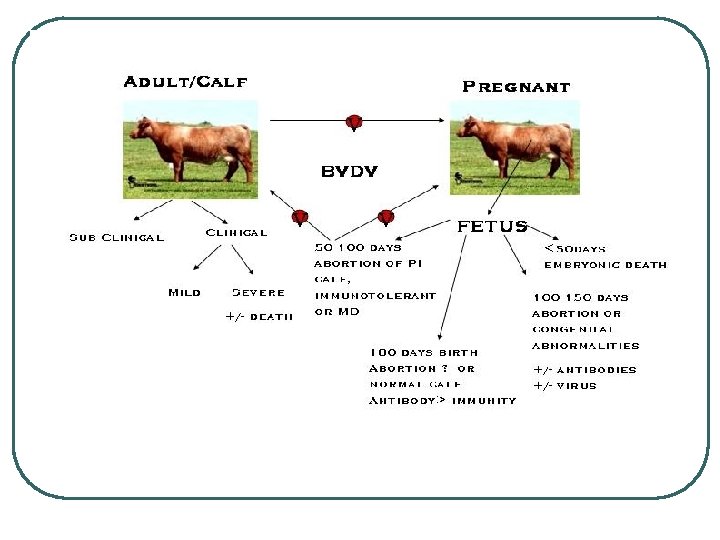

Etiology l l l Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus (BVDV) is a member of the Flaviviridae family in the genus of Pestivirus. It is a positive sense, enveloped, single stranded RNA virus with one open reading frame that encodes four structural and six non-structural proteins. This virus uses a variety of host cell factors in its replication. The structure of the virion is spherical polymorphic. It has the ability to mutate into multiple variants depending on environmental pressures on the virus. www. bvd-info. ch

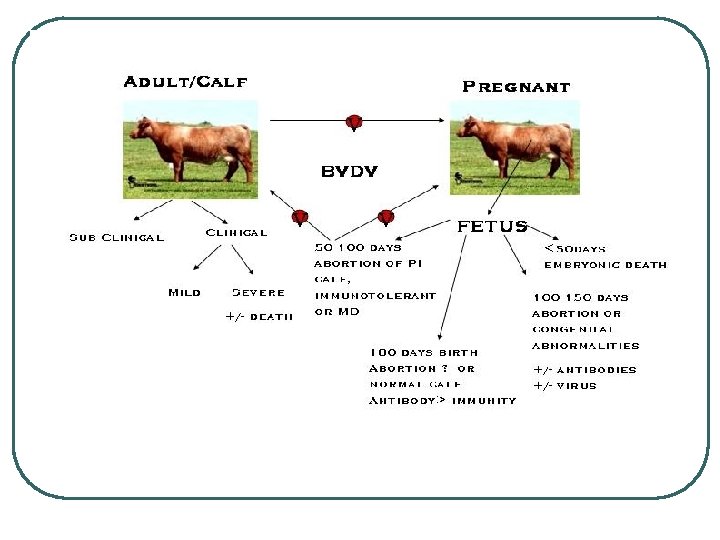

Transmission and Pathogenesis Courtesy Dr. Donal O’Toole

Transmission Factors l Four Main Factors • How infectious is the strain of virus? • How often do infectious and susceptible • • • animals come into contact with each other? How long is the infectious period? How many animals in your herd are infected? How many animals are susceptible and have a poor immune system?

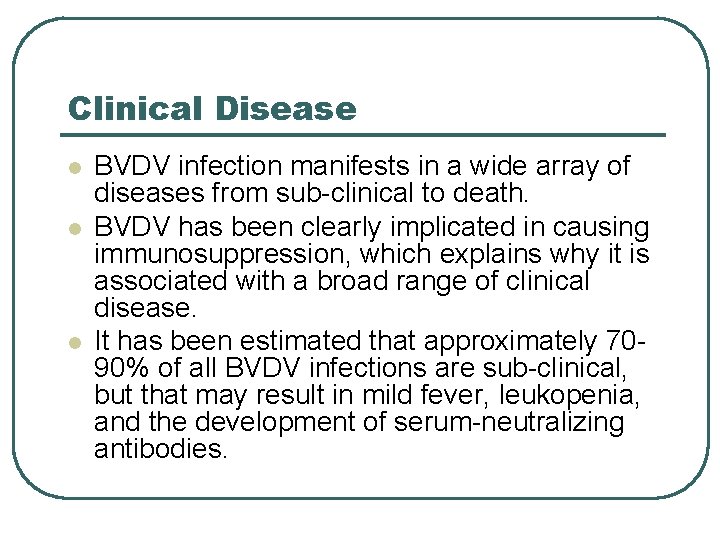

Clinical Disease l l l BVDV infection manifests in a wide array of diseases from sub-clinical to death. BVDV has been clearly implicated in causing immunosuppression, which explains why it is associated with a broad range of clinical disease. It has been estimated that approximately 7090% of all BVDV infections are sub-clinical, but that may result in mild fever, leukopenia, and the development of serum-neutralizing antibodies.

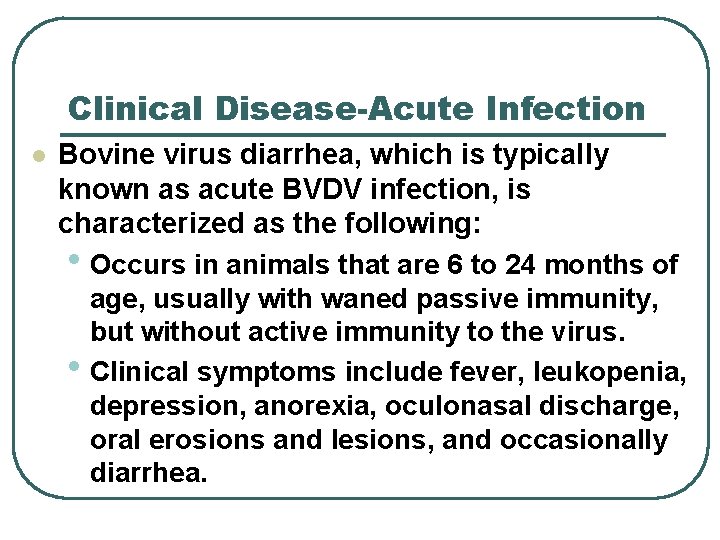

Clinical Disease-Acute Infection l Bovine virus diarrhea, which is typically known as acute BVDV infection, is characterized as the following: • Occurs in animals that are 6 to 24 months of age, usually with waned passive immunity, but without active immunity to the virus. • Clinical symptoms include fever, leukopenia, depression, anorexia, oculonasal discharge, oral erosions and lesions, and occasionally diarrhea.

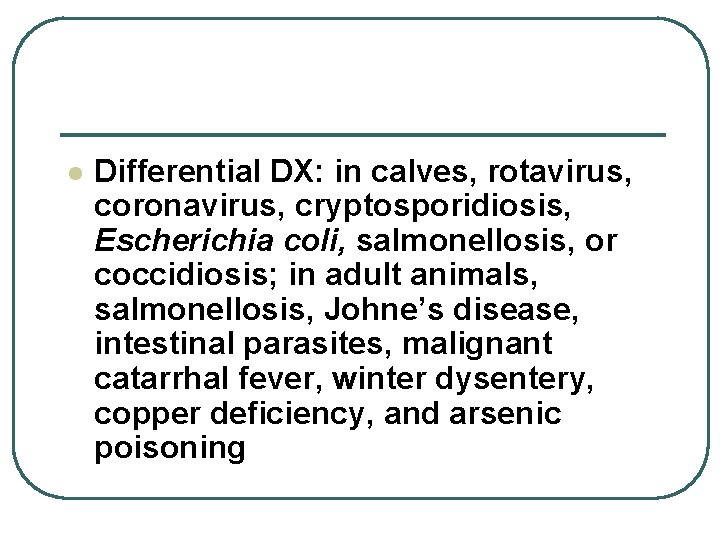

l Differential DX: in calves, rotavirus, coronavirus, cryptosporidiosis, Escherichia coli, salmonellosis, or coccidiosis; in adult animals, salmonellosis, Johne’s disease, intestinal parasites, malignant catarrhal fever, winter dysentery, copper deficiency, and arsenic poisoning

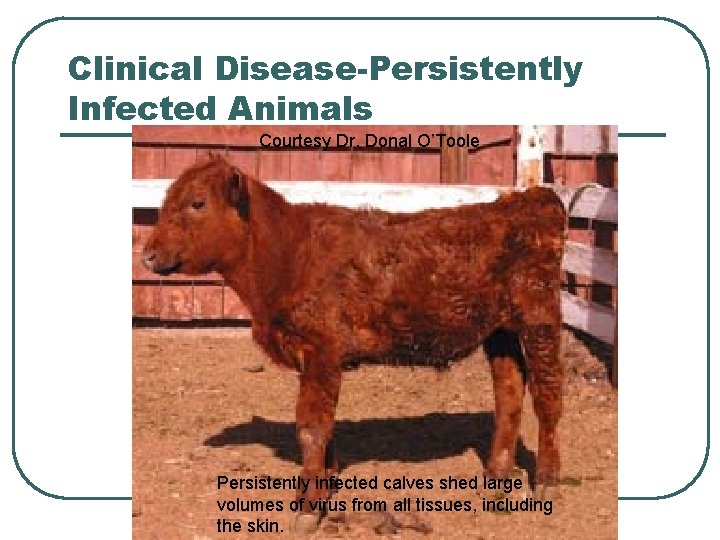

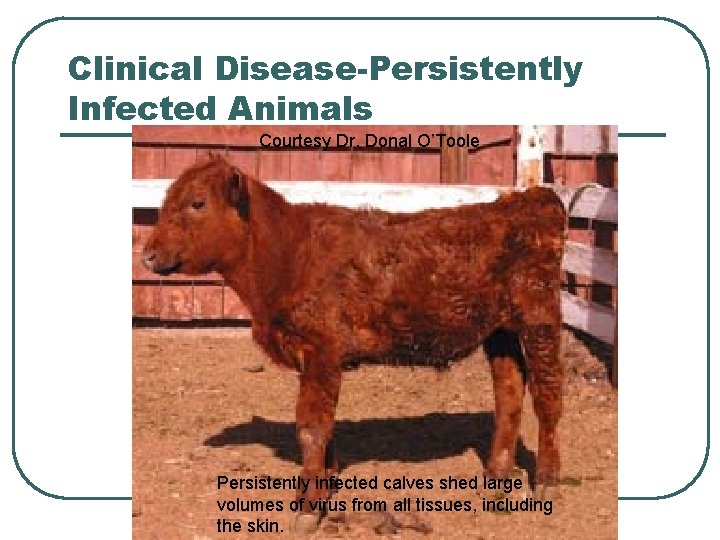

Clinical Disease-Persistently Infected Animals Courtesy Dr. Donal O’Toole Persistently infected calves shed large volumes of virus from all tissues, including the skin.

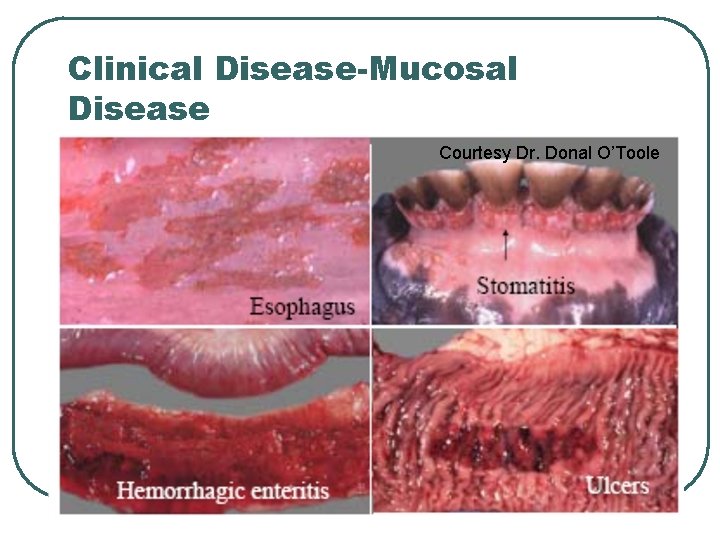

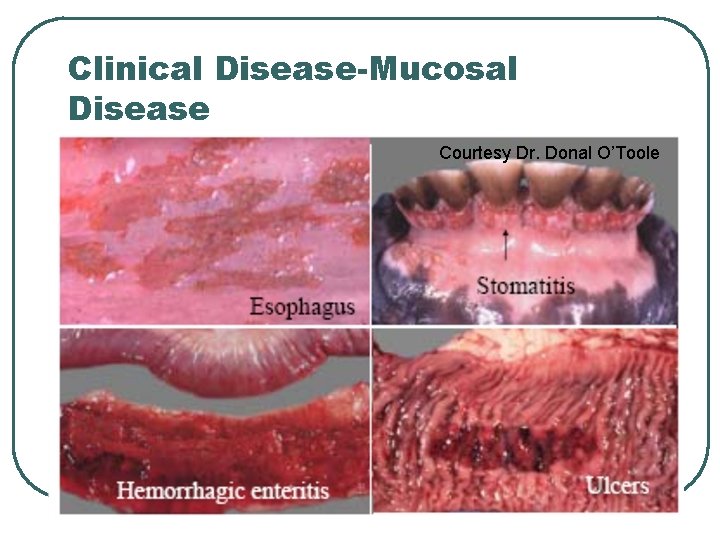

Clinical Disease-Mucosal Disease Courtesy Dr. Donal O’Toole

Clinical Disease-Mucosal Disease • • • Other symptoms associated with acute MD include nasal and corneal discharges, decreased rumination and bloat, excess salivation, corneal opacity, and laminitis or inflammation of the coronary band. Death usually occurs within 3 to 10 days after the onset of clinical disease. Some animals survive the acute stage, but most will simply develop a chronic stage of MD.

Treatment l l Currently, there is no treatment available to cure Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus Treatment Options • Antibiotics for Secondary Infections • If the animal develops Mucosal Disease, there are treatments to alleviate the symptoms, but the animal will eventually die. • Pneumonia etc. • IV fluids for diarrhea and water loss • PI’s should be euthanized to prevent further contamination and potential infection to the rest of the herd.

Control and Prevention l l Controlling BVD virus is the best treatment for any cattle operation. Screening for the virus in all animals is the key to prevent the virus from spreading throughout the herd.

Vaccination l Vaccination does not provide complete protection against BVDV infection • • l • Regular booster shots should be kept up to date according to label or vet Pregnant cattle that are vaccinated have less chance if infected, of transmitting the virus to the fetus. • l It can help to reduce the number of infections Vaccination is not long lasting There is still a chance of abortions in those cattle that are vaccinated Even cattle that are vaccinated may still be able to transmit the disease to other cattle even if there are no symptoms present.