Differences in the behavior organization structure of Aedes

Differences in the behavior organization structure of Aedes albopictus, Anopheles stephensi & Culex pipiens fourth instar larvae; an insight into potential ways for developing a larvacide. Itaki. R, Suguri. S, Arif. H, Fujimoto. C, Harada. M Department of International Medical Zoology, Faculty of Medicine, Kagawa University.

Introduction n Mosquitoes as vectors transmit several human parasitic and viral diseases. Certain species that were previously regarded as nonvectors have become a threat to humans as they find new habitats to establish themselves. Example Aedes albopictus in North America (Durhopf & Benny 1990). Emergence of potential vectors has been attributed to changes in environment and influence of modern life (Gould 2006).

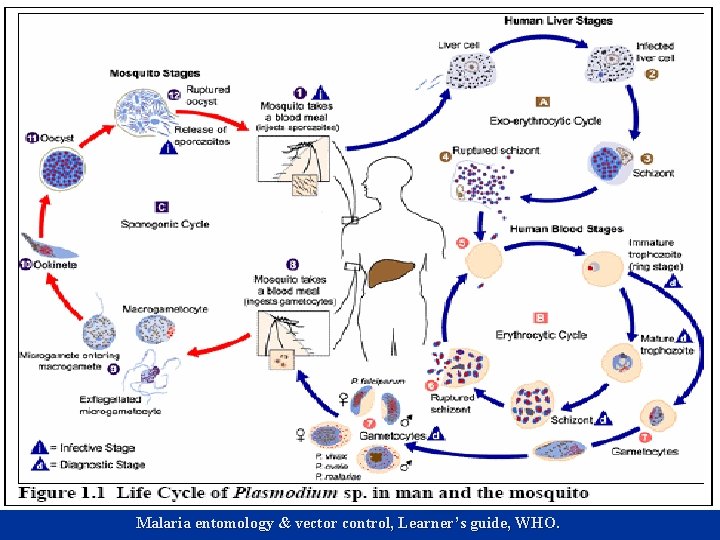

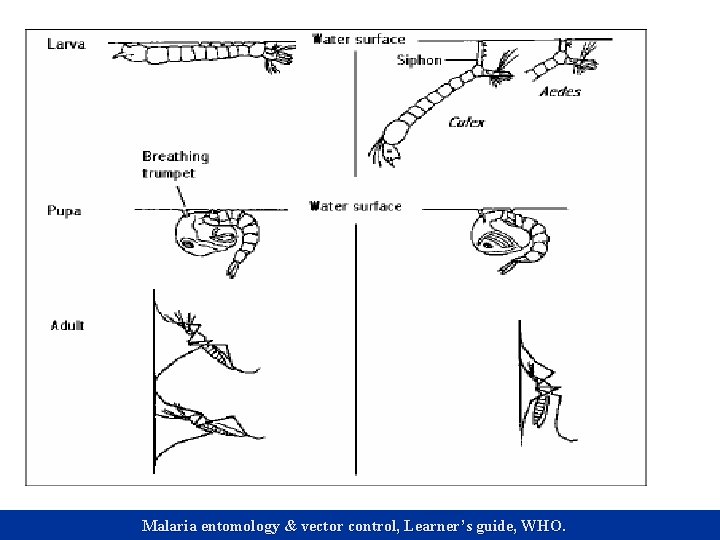

Malaria entomology & vector control, Learner’s guide, WHO.

Introduction n Indeed the ability to establish itself in a new environment and change in host feeding behavior patterns have resulted in emergence of new diseases among humans (Gould 2006). Therefore the ability of the mosquito to establish itself in a new environment is directly affected by the ability of the larva to exploit its aquatic habitat. ‘Airport malaria in non-endemic countries is due to lack of mosquito to establish resident population.

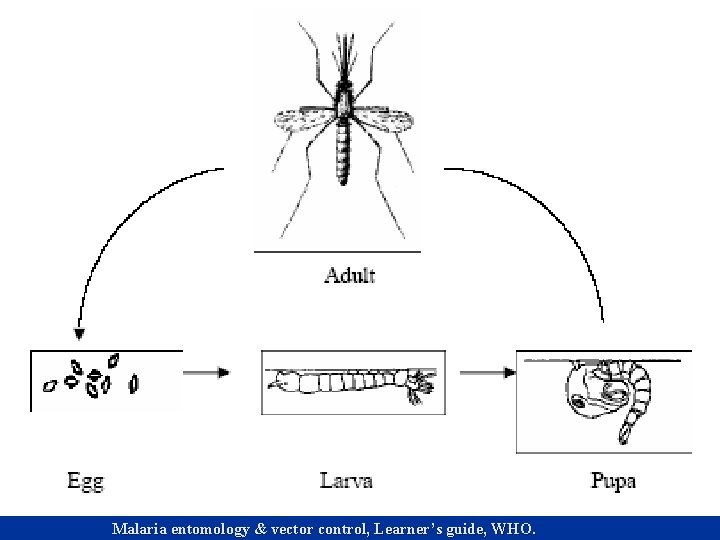

Malaria entomology & vector control, Learner’s guide, WHO.

Previous studies on larva behavior n n n Jones (1954) listed Anopheles quadrimaculatus behaviors. Walker & Merritt (1991) developed a catalogue of behaviors for Aedes triseriatus. Durhopf & Benny (1990) looked at the alarm responses of several strains of Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti. Tuno et al (2004) examined the submergence time of Anopheles gambiae Giles larva. Response to visual stimuli, to waves at water’s surface, to falling water droplets and to vibration have all been studied to some degree (Clements 1999).

Previous studies on larva behavior The different behaviors observed have been proposed to be survival mechanisms to escape predators or from being washed away in container breeding mosquitoes during rainfall. n In a controlled environment larva become habituated to the stimulus. This habituation is lost with a new stimulus. n

Studies on feeding behavior & larval toxins n n n Development of bacterially (B. thuringiensis israelensis; B. sphaericus) derived stomach toxins as control agents for mosquito larva (Lacey & Undeen 1986) resulted in an increased interest in their feeding behavior. Difference in feeding behavior may result in different abilities to exploit their habitat (Duhrkopf & Benny 1990). Species –specific differences in larval behavior may allow certain species to adapt more quickly to new environment and establish themselves more rapidly (Workman & Walton 2003, Yee et al 2004).

Previous studies on larva behavior n n Aedes species tend to use their entire habitat for feeding (Walker & Merritt 1991). Anopheles species generally feed at the air-water interface but can dive and feed at the bottom of their aquatic environments (Tuno et al 2004). Culex species forage primarily by filtering the water column and tend to concentrate their effort near the water’s surface (Yee et al 2004). Yee et al (2004) found out that mosquito larvae tend to modify their feeding behavior according to the food environment.

Rationale for this study n n General differences in the larval behavior of Anopheles species compared to Aedes and Culex species can be deduced from other studies but the details are obscure. Few studies on Anopheles larva behavior.

Aims & objectives To observe and compare the behaviors of Anopheles, Aedes and Culex mosquito larvae. n Determine the differences in the organizational structure of their behavior. n Determine the differences in the amount of time larvae spent in each behavioral state. n

Malaria entomology & vector control, Learner’s guide, WHO.

Materials & method – species & larvae n n n Aedes albopictus, Anopheles stephansi & Culex pipiens. Larvae & adults maintained using standard protocols in an insectary (temp. 26 o. C, RH 65%) with a 15 hrs, 8 hrs day-night cycle. Light provided by x 4 40 -watt fluorescent light bulbs. Eggs hatched in 250 ml of de-chlorinated tap H 2 O in plastic cups. 2 -3 instar stage larvae transferred to a 33 x 24 x 7 -cm pans. Larvae fed on Tetra Min baby fish food.

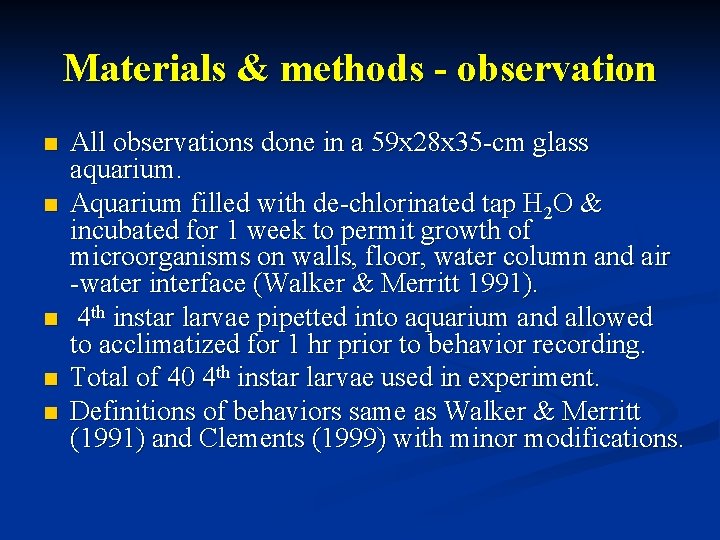

Materials & methods - observation n n All observations done in a 59 x 28 x 35 -cm glass aquarium. Aquarium filled with de-chlorinated tap H 2 O & incubated for 1 week to permit growth of microorganisms on walls, floor, water column and air -water interface (Walker & Merritt 1991). 4 th instar larvae pipetted into aquarium and allowed to acclimatized for 1 hr prior to behavior recording. Total of 40 4 th instar larvae used in experiment. Definitions of behaviors same as Walker & Merritt (1991) and Clements (1999) with minor modifications.

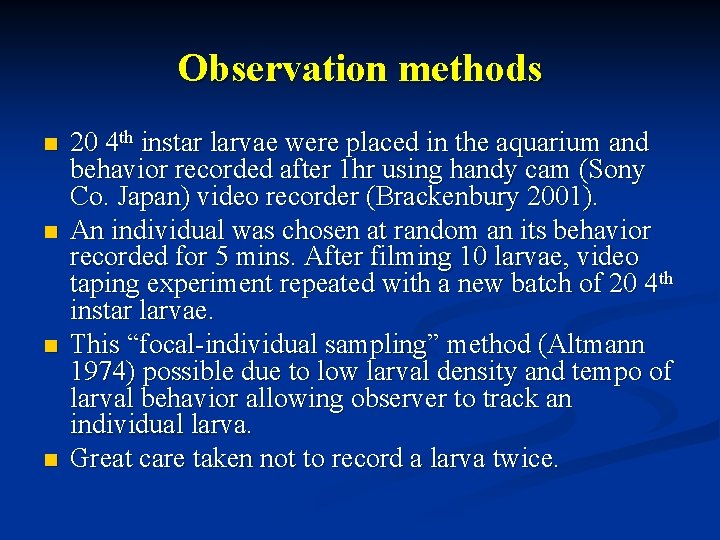

Observation methods n n 20 4 th instar larvae were placed in the aquarium and behavior recorded after 1 hr using handy cam (Sony Co. Japan) video recorder (Brackenbury 2001). An individual was chosen at random an its behavior recorded for 5 mins. After filming 10 larvae, video taping experiment repeated with a new batch of 20 4 th instar larvae. This “focal-individual sampling” method (Altmann 1974) possible due to low larval density and tempo of larval behavior allowing observer to track an individual larva. Great care taken not to record a larva twice.

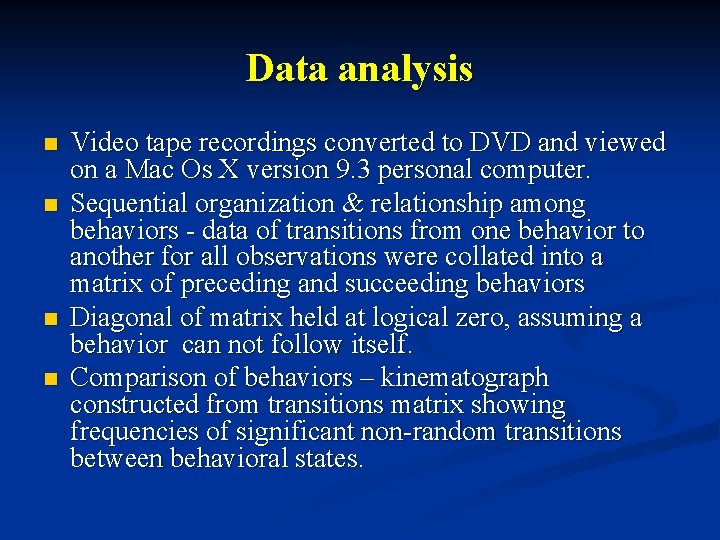

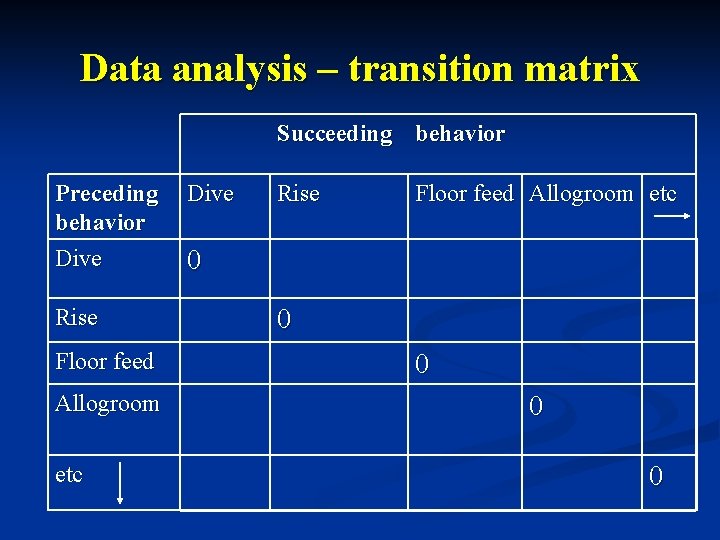

Data analysis n n Video tape recordings converted to DVD and viewed on a Mac Os X version 9. 3 personal computer. Sequential organization & relationship among behaviors - data of transitions from one behavior to another for all observations were collated into a matrix of preceding and succeeding behaviors Diagonal of matrix held at logical zero, assuming a behavior can not follow itself. Comparison of behaviors – kinematograph constructed from transitions matrix showing frequencies of significant non-random transitions between behavioral states.

Data analysis – transition matrix Succeeding behavior Preceding behavior Dive Rise Floor feed Allogroom etc 0 0 0

Data analysis n n n Time budget also created for each behavior. Transition matrix collapsed about the cell of interest to form a 2 x 2 contingency table for significant testing. Significant testing for first-order transitions done by G statistics (P<0. 005) on Microsoft excel. Mean time spent for each behavior compared by oneway ANOVA for 3 independent samples. Significant differences in mean time further analyzed by pair-wise comparison using Tukey HSD test.

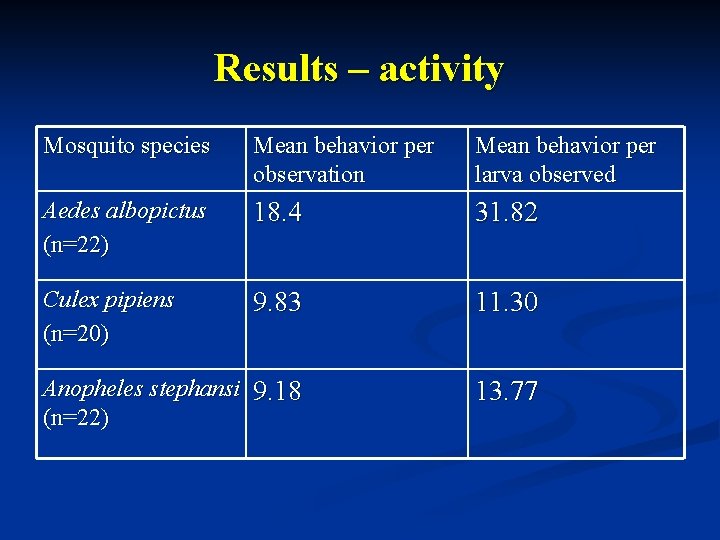

Results – activity Mosquito species Mean behavior per observation Mean behavior per larva observed Aedes albopictus (n=22) 18. 4 31. 82 Culex pipiens (n=20) 9. 83 11. 30 Anopheles stephansi 9. 18 (n=22) 13. 77

Results - activity n n n Aedes albopictus was the most active species compared to Culex pipiens & Anopheles stephansi. Culex pipiens was slightly more active overall when compared with Anopheles stephansi. Individually, Anopheles stephansi was more active than Culex pipiens.

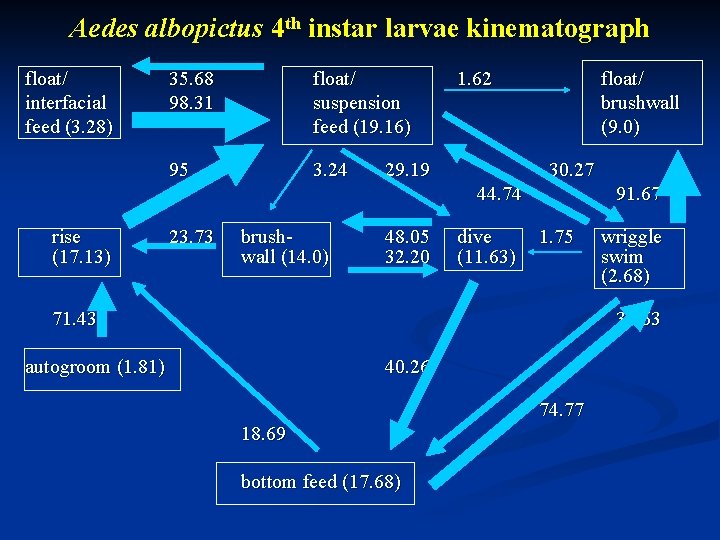

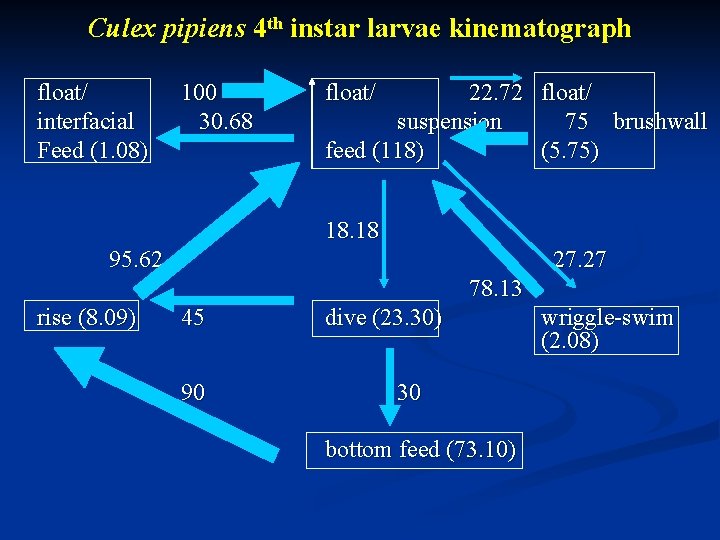

Aedes albopictus 4 th instar larvae kinematograph float/ interfacial feed (3. 28) 35. 68 98. 31 float/ suspension feed (19. 16) 95 3. 24 1. 62 29. 19 float/ brushwall (9. 0) 30. 27 44. 74 rise (17. 13) 23. 73 brushwall (14. 0) 48. 05 32. 20 dive (11. 63) 91. 67 1. 75 71. 43 wriggle swim (2. 68) 31. 63 autogroom (1. 81) 40. 26 74. 77 18. 69 bottom feed (17. 68)

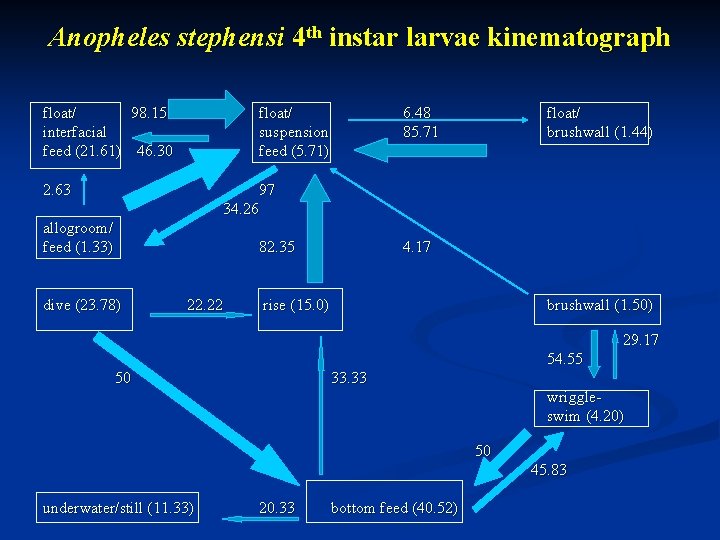

Culex pipiens 4 th instar larvae kinematograph float/ interfacial Feed (1. 08) 100 30. 68 float/ 22. 72 float/ suspension 75 brushwall feed (118) (5. 75) 18. 18 95. 62 27. 27 78. 13 rise (8. 09) 45 90 dive (23. 30) 30 bottom feed (73. 10) wriggle-swim (2. 08)

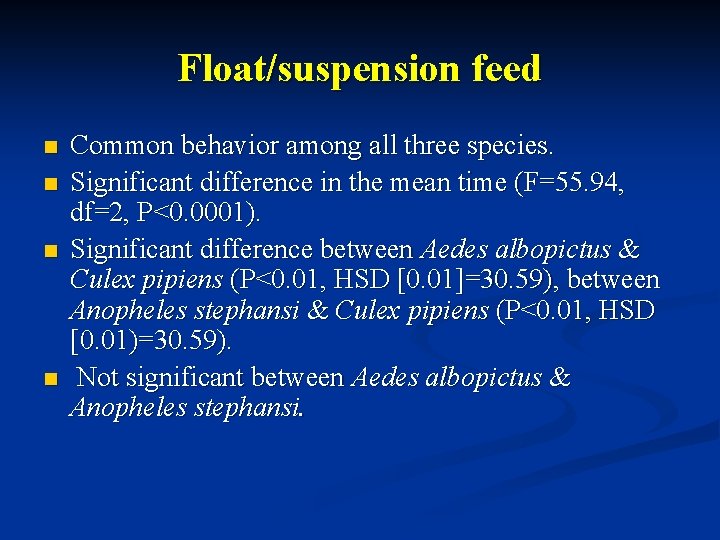

Anopheles stephensi 4 th instar larvae kinematograph float/ 98. 15 interfacial feed (21. 61) 46. 30 float/ suspension feed (5. 71) 2. 63 6. 48 85. 71 float/ brushwall (1. 44) 97 34. 26 allogroom/ feed (1. 33) 82. 35 dive (23. 78) 22. 22 4. 17 rise (15. 0) brushwall (1. 50) 29. 17 54. 55 50 33. 33 wriggleswim (4. 20) 50 45. 83 underwater/still (11. 33) 20. 33 bottom feed (40. 52)

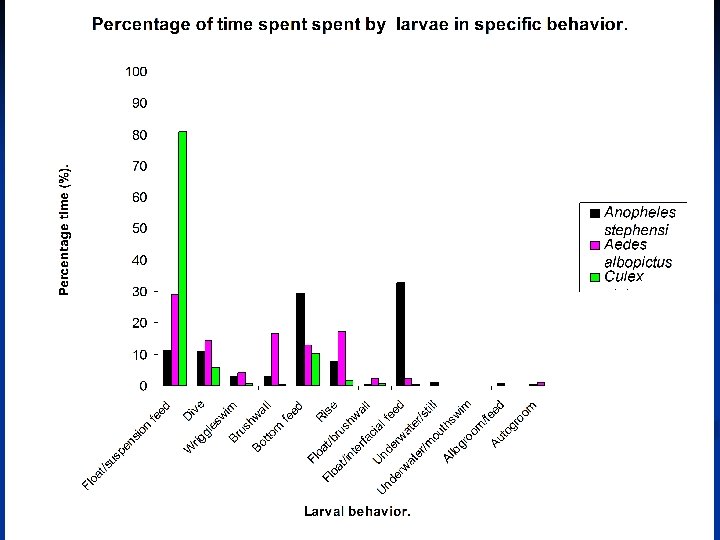

Float/suspension feed n n Common behavior among all three species. Significant difference in the mean time (F=55. 94, df=2, P<0. 0001). Significant difference between Aedes albopictus & Culex pipiens (P<0. 01, HSD [0. 01]=30. 59), between Anopheles stephansi & Culex pipiens (P<0. 01, HSD [0. 01)=30. 59). Not significant between Aedes albopictus & Anopheles stephansi.

Float/interfacial feed Common behavior among all three species. n Significant difference in the mean time (F=11. 16, df=2, P<0. 0001). n Significant difference between Anopheles stephansi & Aedes albopictus and between Anopheles stephansi & Culex pipiens (P<0. 01, HSD[0. 01]=17. 24). n Not significant between Aedes albopictus & Culex pipiens. n

Dive Common behavior among all three species. n Aedes albopictus dived frequently & vertically. n Culex pipiens & Anopheles stephansi did not dive frequently. n Culex pipiens dived at an angle while Anopheles stephansi dived in a zigzag manner & sometimes passively. n

Brushwall Common behavior in Aedes albopictus and Anopheles stephansi but not in Culex pipiens. n Aedes albopictus brushed the wall while at the surface as well as after diving. n Anopheles stephansi brushed the wall only after diving. n No significant difference in the mean time spent among the three species (F=0. 22, df=2, P=0. 81). n

Float/brushwall Common behavior among all three species. n No significant difference in mean time spent performing this behavior. n

Wriggle swim Common behavior among all three species. n Culex pipiens performed this behavior near the surface, Anopheles stephansi at the bottom of the water column. n Aedes albopictus used this behavior both near the surface and the bottom. n No significant difference in the mean time (F=0. 93, df=2, P=0. 4). n

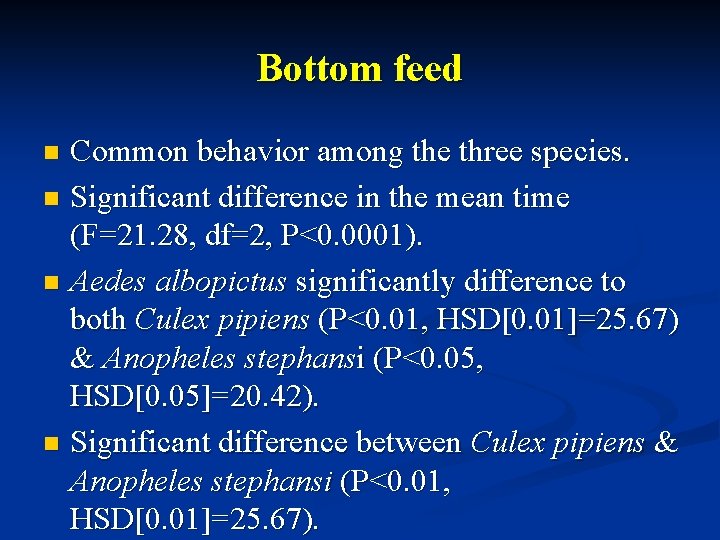

Bottom feed Common behavior among the three species. n Significant difference in the mean time (F=21. 28, df=2, P<0. 0001). n Aedes albopictus significantly difference to both Culex pipiens (P<0. 01, HSD[0. 01]=25. 67) & Anopheles stephansi (P<0. 05, HSD[0. 05]=20. 42). n Significant difference between Culex pipiens & Anopheles stephansi (P<0. 01, HSD[0. 01]=25. 67). n

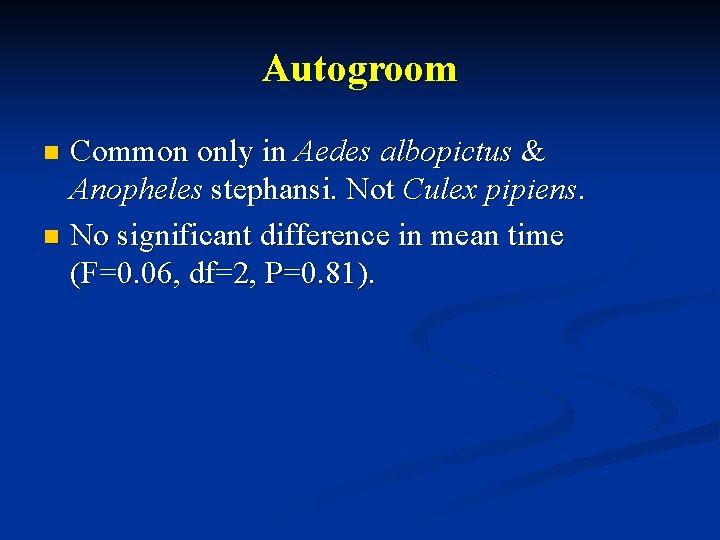

Autogroom Common only in Aedes albopictus & Anopheles stephansi. Not Culex pipiens. n No significant difference in mean time (F=0. 06, df=2, P=0. 81). n

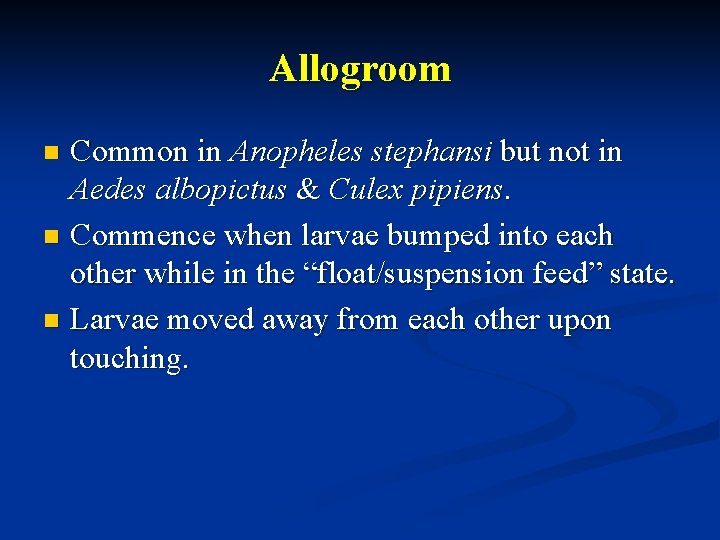

Allogroom Common in Anopheles stephansi but not in Aedes albopictus & Culex pipiens. n Commence when larvae bumped into each other while in the “float/suspension feed” state. n Larvae moved away from each other upon touching. n

Rise Common in all three species. n No significant difference in mean time (F=4. 38, df=2, P=0. 02. n

Underwater still Only observed in Anopheles stephansi. n Not observed in Aedes Albopictus or Culex pipiens. n Underwater mouth-swim not observed in all three species. n

Conclusion n n There is significant difference in the behavioral organization of Aedes albopictus, Anopheles stephansi and Culex pipiens larvae. Some larval behaviors that are common in one species are not observed in other species. There is significant difference in the mean time spent performing each behavior. These differences in larval behavior could be attributed to differences in feeding behavior as well as physiology. These differences can be exploited to design new larval control methods.

Thank you

Thank you

- Slides: 42