Dialect on trial Bias against AAVE influences juror

Dialect on trial: Bias against AAVE influences juror appraisals and potentially decision making Courtney Kurinec, M. A. , & Charles Weaver III, Ph. D. Baylor University AP-LS 2018

Speaker dialect and perception • Style of speech can activate stereotypes about a speaker • Standard speakers are evaluated more positively than non-standard speakers Bucholtz & Hall (2005); Smalls (2004)

Dialect in the courtroom • Witnesses using foreign-accented speech are seen as less credible • Suspects using non-standard dialects are viewed as more criminal, more likely to be guilty Dixon & Mahoney (2004); Dixon, Mahoney, & Cocks (2002); Frumkin

Problem: How are AAVE speakers viewed in the courtroom? • African American Vernacular English (AAVE) speakers are often viewed as less competent and less educated than speakers of General American English (GAE) • AAVE use may activate listeners’ implicit or explicit racial biases • This may unintentionally disadvantage AAVE speakers in the courtroom Billings (2005); Purnell, Idsardi, & Baugh (1999)

Research questions 1. Does use of AAVE influence juror perceptions of the speaker and ultimately their decision making? 2. Does race interact with AAVE use, such that Black AAVE speakers are evaluated more negatively than Black GAE speakers?

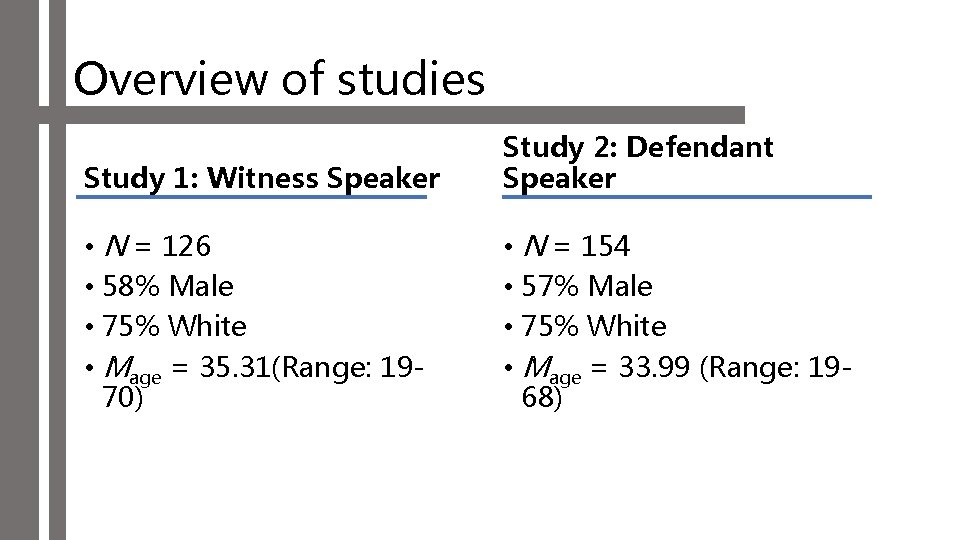

Overview of studies Study 1: Witness Speaker Study 2: Defendant Speaker • N = 126 • 58% Male • 75% White • Mage = 35. 31(Range: 1970) • N = 154 • 57% Male • 75% White • Mage = 33. 99 (Range: 1968)

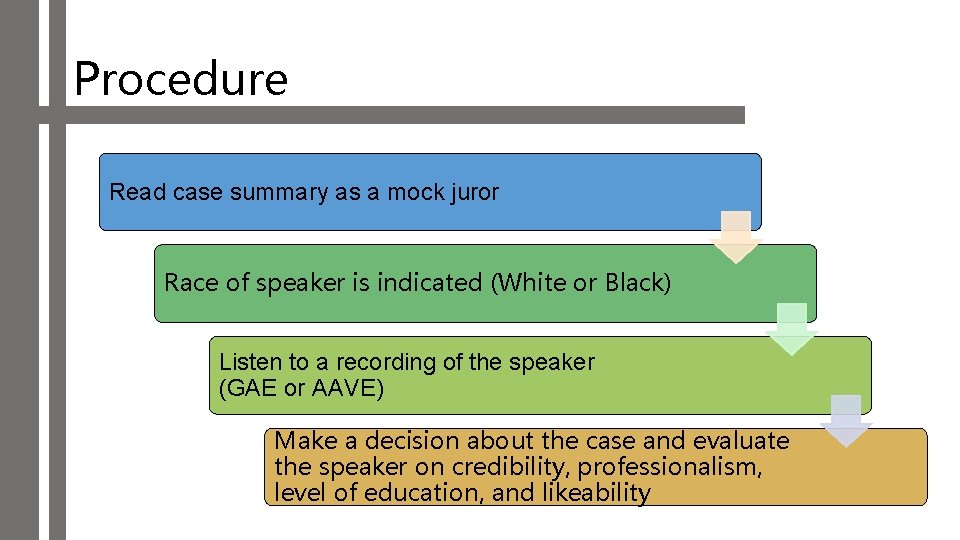

Procedure Read case summary as a mock juror Race of speaker is indicated (White or Black) Listen to a recording of the speaker (GAE or AAVE) Make a decision about the case and evaluate the speaker on credibility, professionalism, level of education, and likeability

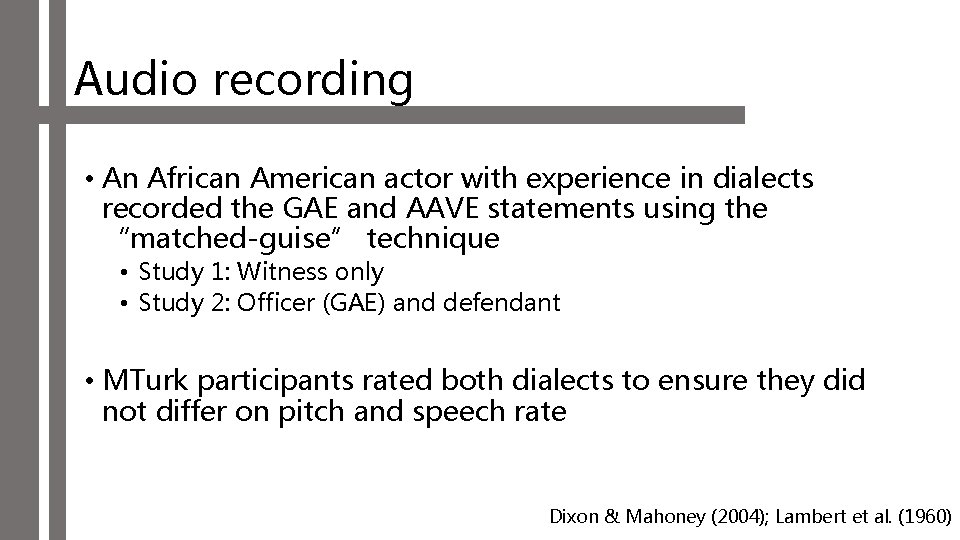

Audio recording • An African American actor with experience in dialects recorded the GAE and AAVE statements using the “matched-guise” technique • Study 1: Witness only • Study 2: Officer (GAE) and defendant • MTurk participants rated both dialects to ensure they did not differ on pitch and speech rate Dixon & Mahoney (2004); Lambert et al. (1960)

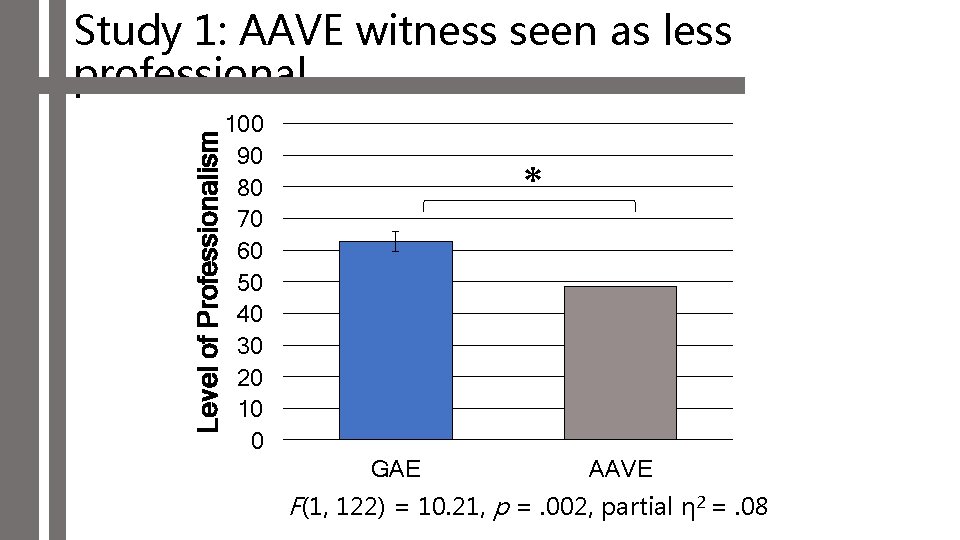

Level of Professionalism Study 1: AAVE witness seen as less professional 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 * GAE AAVE F(1, 122) = 10. 21, p =. 002, partial η 2 =. 08

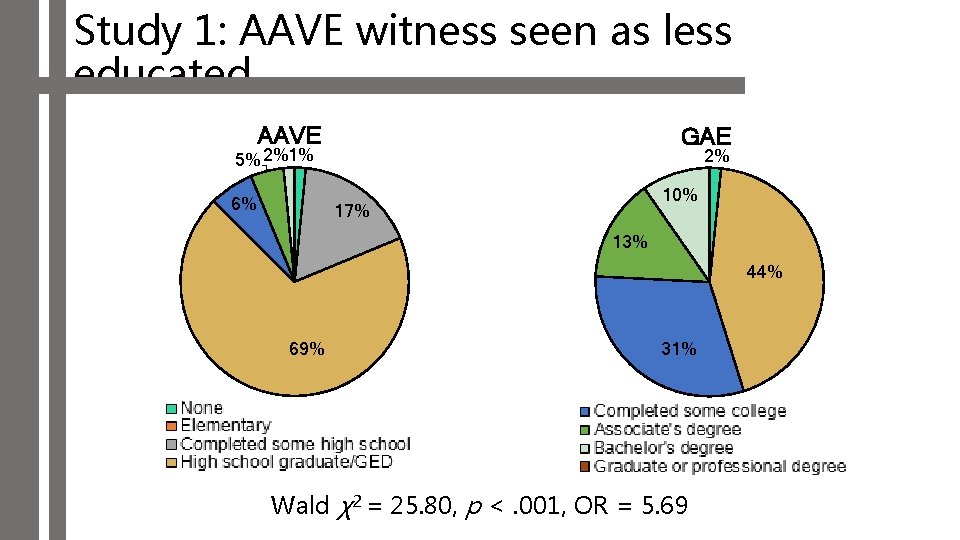

Study 1: AAVE witness seen as less educated AAVE GAE 5% 2%1% 6% 2% 10% 17% 13% 44% 69% 31% Wald χ2 = 25. 80, p <. 001, OR = 5. 69

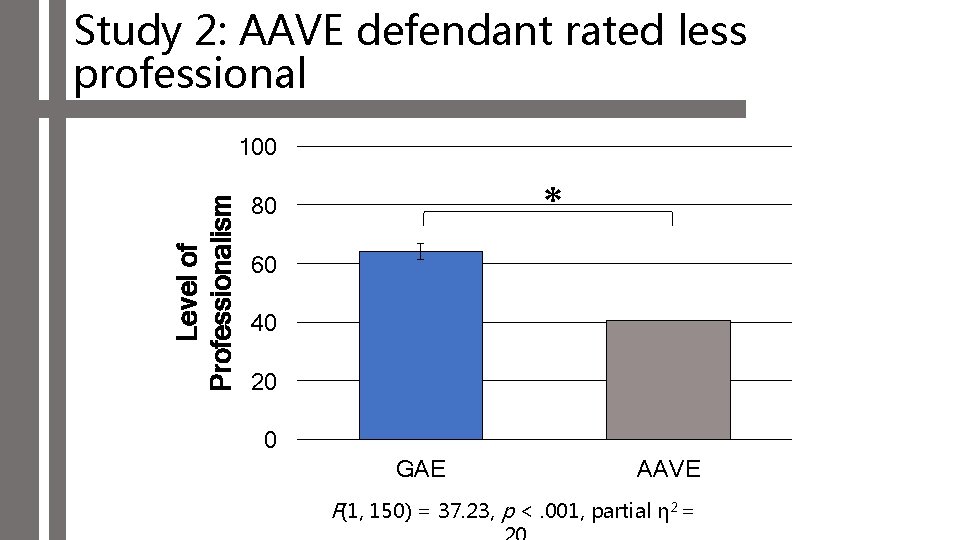

Study 2: AAVE defendant rated less professional Level of Professionalism 100 * 80 60 40 20 0 GAE AAVE F(1, 150) = 37. 23, p <. 001, partial η 2 =

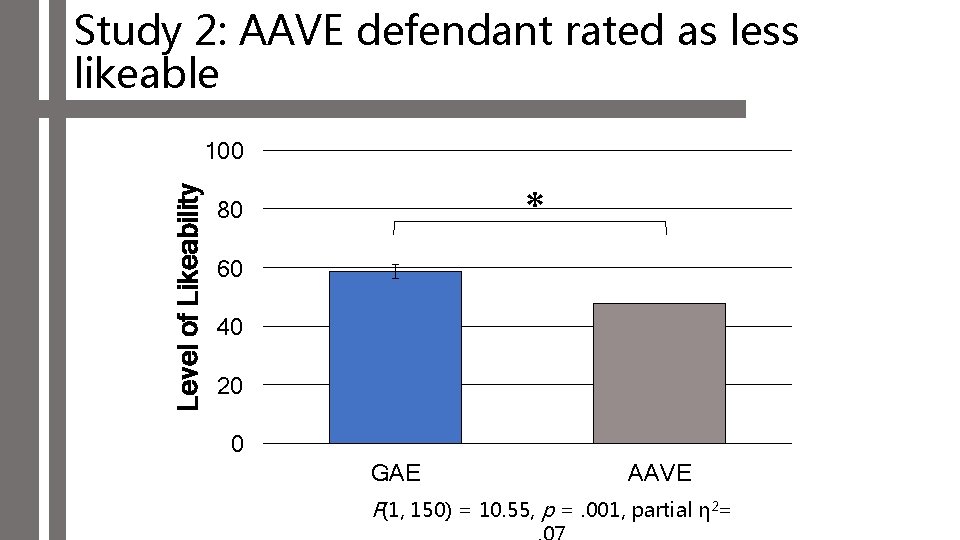

Study 2: AAVE defendant rated as less likeable Level of Likeability 100 * 80 60 40 20 0 GAE AAVE F(1, 150) = 10. 55, p =. 001, partial η 2=

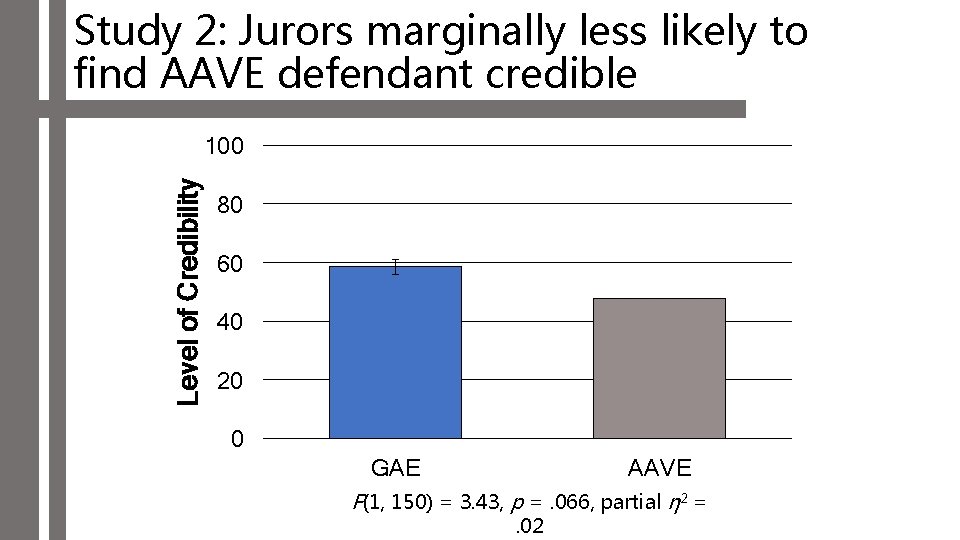

Study 2: Jurors marginally less likely to find AAVE defendant credible Level of Credibility 100 80 60 40 20 0 GAE AAVE F(1, 150) = 3. 43, p =. 066, partial η 2 =. 02

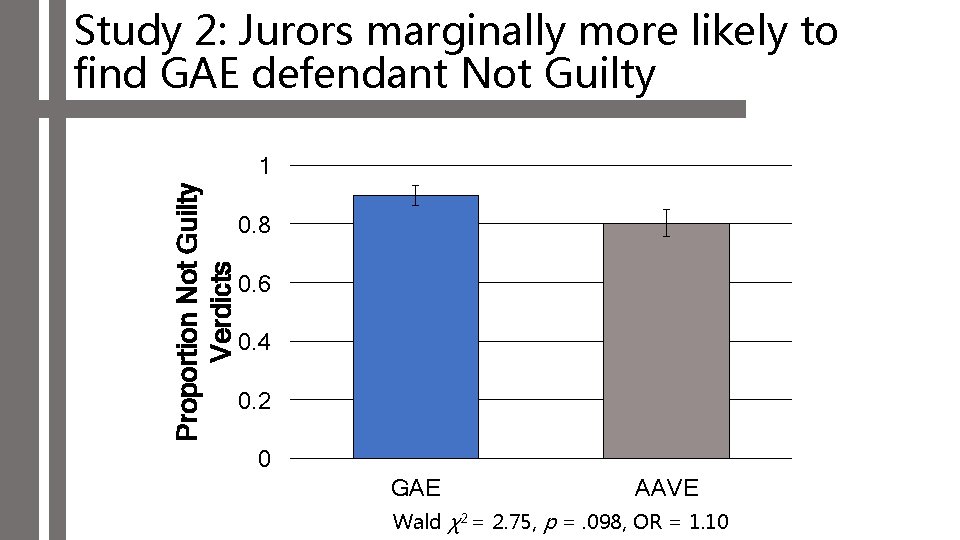

Study 2: Jurors marginally more likely to find GAE defendant Not Guilty Proportion Not Guilty Verdicts 1 0. 8 0. 6 0. 4 0. 2 0 GAE AAVE Wald χ2 = 2. 75, p =. 098, OR = 1. 10

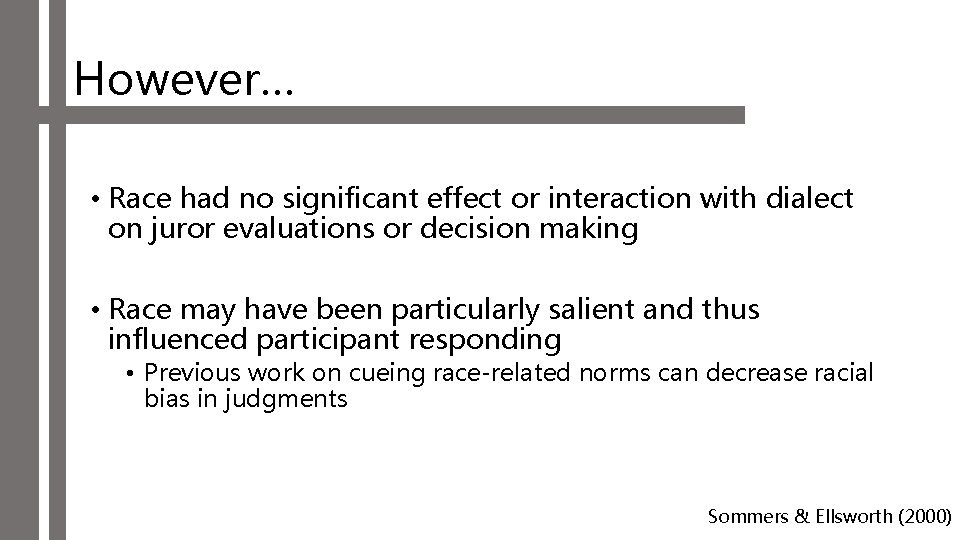

However… • Race had no significant effect or interaction with dialect on juror evaluations or decision making • Race may have been particularly salient and thus influenced participant responding • Previous work on cueing race-related norms can decrease racial bias in judgments Sommers & Ellsworth (2000)

Conclusions • Bias against AAVE can spread to the courtroom • Stereotypes about AAVE can shape jurors’ view of speakers and potentially influence judgments • Professionals representing or preparing AAVE speakers should be particularly attentive to how dialect can influence juror perceptions

Limitations and future directions • Limitations • Using predominantly written mock juror paradigm • Although different recordings, using same speaker • Future directions • Using video rather than written + audio manipulations • Extending to other non-standard dialects

Acknowledgements Memory and Cognition Lab • • Brittany Nesbitt, BS Elysse Reyes Rachel Sangster Tierra Carter Gabi Fowler Ann Iftikhar Erika Arvidson Sam Henderson, MFA

Thank You! Contact: Courtney_Kurinec@baylor. edu

References Billings, A. C. (2005). Beyond the Ebonics debate: Attitudes about Black and Standard American English. Journal of Black Studies, 36, 68 -81. doi: 10. 1177/0021934704271448 Bucholtz, M. , & Hall, K. (2005). Identity and interaction: A sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Studies, 7, 585 -614. doi: 10. 1177/1461445605054407 Dixon, J. A. , & Mahoney, B. (2004). The effect of accent evaluation and evidence on a suspect’s perceived guilt and criminality. The Journal of Social Psychology, 144, 63 -73. doi: 10. 3200/SOCP. 144. 1. 63 -73 Dixon, J. A. , Mahoney, B. , & Cocks, R. (2002). Accents of guilt? Effects of regional accent, race, and crime type on attributions of guilt. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 21, 162 -168.

References Frumkin, L. (2007). Influences of accent and ethnic background on perceptions of eyewitness testimony. Psychology, Crime & Law, 13, 317 – 331. Lambert, W. E. , Hodgson, R. C. , Gardner, R. C. , & Fillenbaum, S. (1960). Evaluational reactions to spoken languages. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 60, 44 -51. Purnell, T. , Idsardi, W. , & Baugh, J. (1999). Perceptual and phonetic experiments on American English dialect identification. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 18, 10 -30. Smalls, D. L. (2004). Linguistic profiling and the law. Stanford Law and Policy Review, 15, 579 -604.

- Slides: 21