DIAGNOSING CUTANEOUS VASCULITIS By Dr Donna Braham Objectives

DIAGNOSING CUTANEOUS VASCULITIS By: Dr. Donna Braham

Objectives • Classify Vasculitis • Know when to consider Vasculitis • Rule out mimickers of Vasculitis • Diagnose cutaneous small vessel vasculitis – In particular Henoch–Schönlein Purpura, Essential Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis and Cutaneous Leukocytoclastic angiitis

Vasculitis • Specific pattern of inflammation of the blood vessel wall and it can occur in any size vessel and in any organ system of the body. • Cutaneous vasculitis may be: • (1) a skin-limited disease • (2) a primary cutaneous vasculitis with secondary systemic involvement • (3) a cutaneous manifestation of a systemic vasculitis

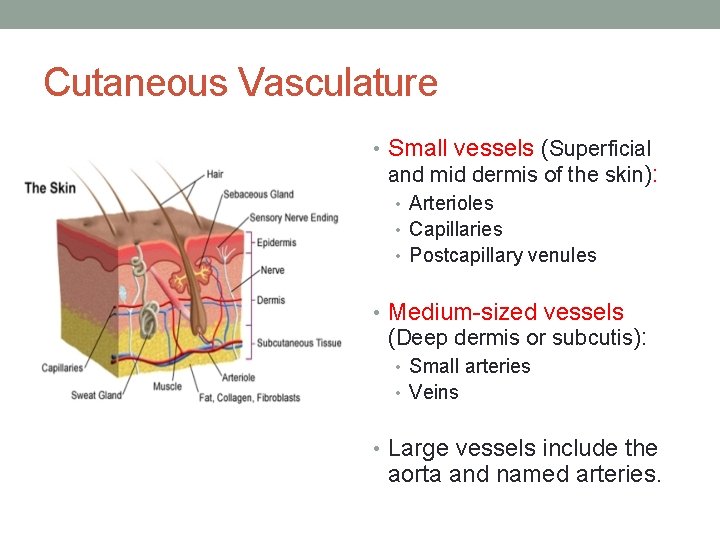

Cutaneous Vasculature • Small vessels (Superficial and mid dermis of the skin): • Arterioles • Capillaries • Postcapillary venules • Medium-sized vessels (Deep dermis or subcutis): • Small arteries • Veins • Large vessels include the aorta and named arteries.

Chapel Hill Consensus Conference on the Nomenclature of Systemic Vasculitis • Small Vessel Vasculitis • Granulomatosis with • • • Polyangiitis (GPA) Wegener’s Granulomatosis Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) Churg-Strauss Syndrome Microscopic Polyangiitis (MPA) Henoch-Schonlein purpura (HSP) Essential Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis Cutaneous Leukocytoclastic angiitis (CSVV) • Medium-sized Vessel Vasculitis • Polyarteritis Nodosa • Kawasaki Disease • Large-sized Vessel Vasculitis • Giant cell (temporal) arteritis • Takayasu arteritis

Epidemiology • The incidence of biopsy-proven cutaneous vasculitis of all types is 15– 60 patients per million per year. • Cutaneous vasculitis occurs in all age groups • mean age in adults, 47 years; mean age in children, 7 years • Much more common in adults than in children • Slight female predominance • The majority of children have Henoch–Schönlein purpura which is associated with pesticide and drugs. • All are more common in whites compared with other populations • Genetic and environmental factors, including infection, drugs, and silica play a role

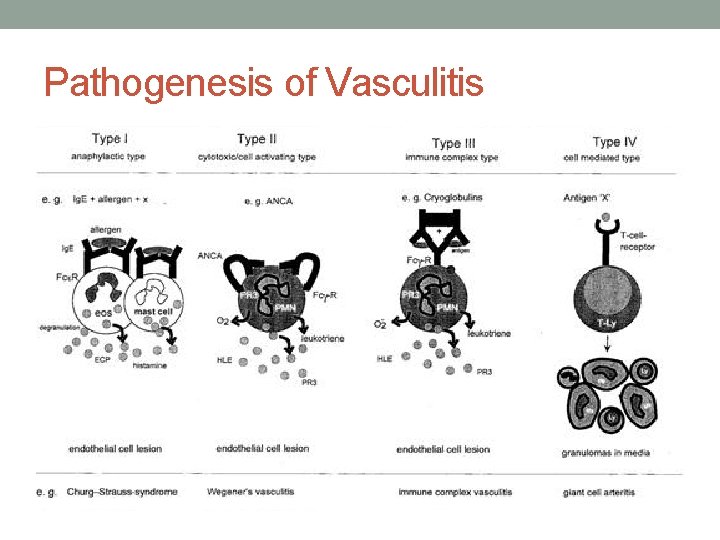

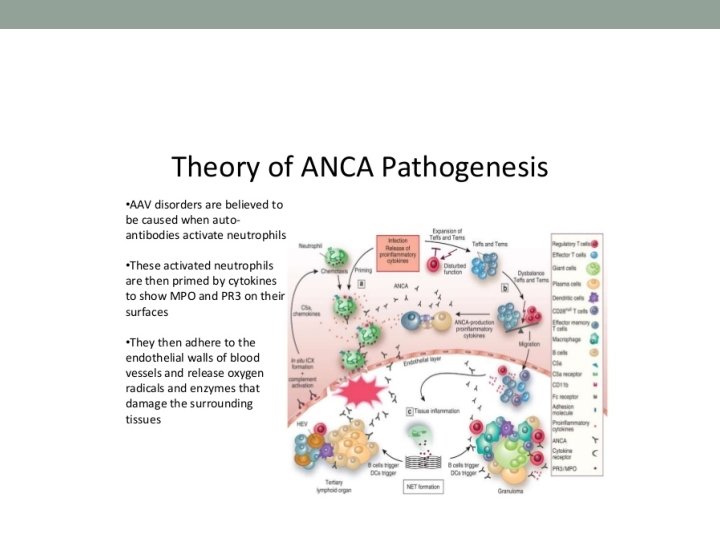

Pathogenesis 1. Immune complex-mediated inflammation • Polyarteritis nodosa, • Cryoglobulinaemia • Henoch-Schönlein purpura 2. Autoantibody-mediated inflammation (ANCA) • Wegener's granulomatosis • Churg-Strauss syndrome • Microscopic polyangiitis • Necrotizing glomerulonephritis 3. Cell-mediated inflammation • GCA

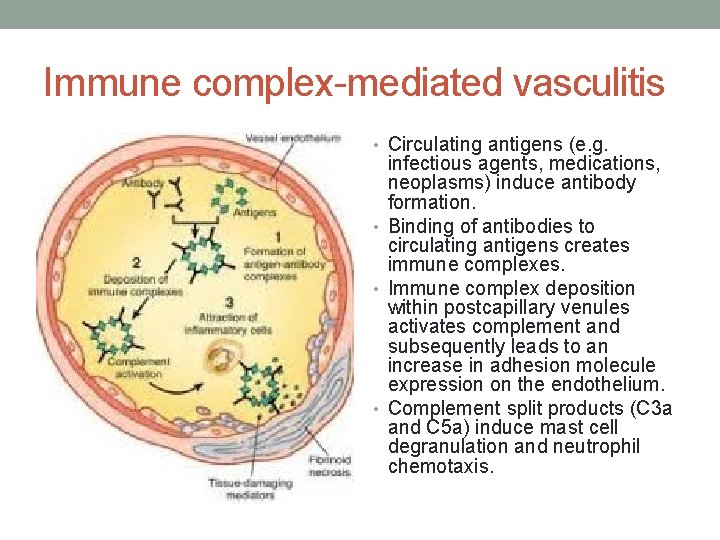

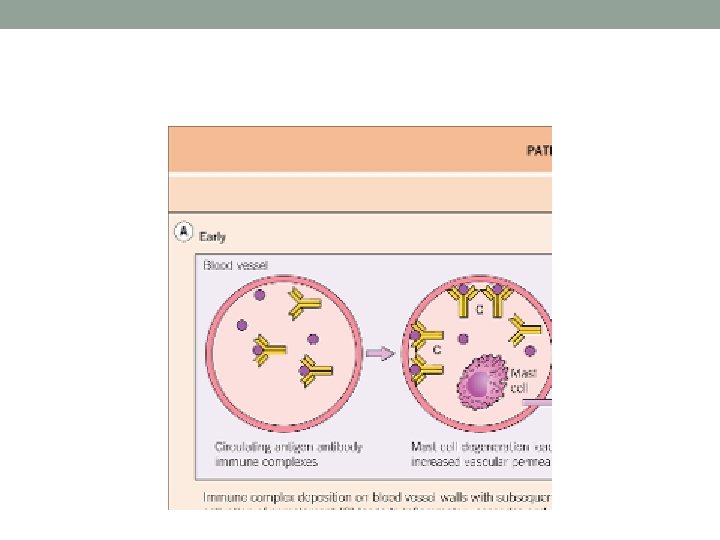

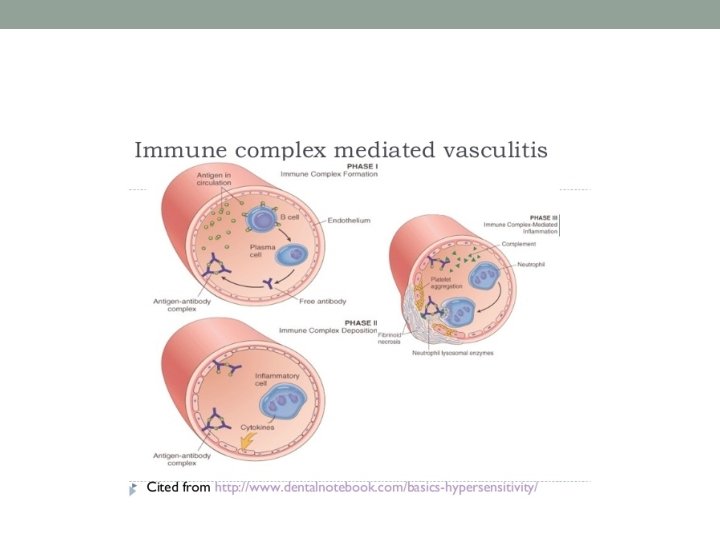

Immune complex-mediated vasculitis • Circulating antigens (e. g. infectious agents, medications, neoplasms) induce antibody formation. • Binding of antibodies to circulating antigens creates immune complexes. • Immune complex deposition within postcapillary venules activates complement and subsequently leads to an increase in adhesion molecule expression on the endothelium. • Complement split products (C 3 a and C 5 a) induce mast cell degranulation and neutrophil chemotaxis.

Immune complex-mediated vasculitis • Mast cell degranulation leads to increased vascular dilation and permeability, enhancing immune complex deposition and leukocyte tethering to endothelium • Neutrophils release proteolytic enzymes (such as collagenases and elastases) and free oxygen radicals that damage the vessel wall. • In addition, formation of the membrane attack complex (C 5–C 9) on the endothelium leads to the activation of the clotting cascade and the release of cytokines and growth factors with ensuing thrombosis, inflammation and angiogenesis.

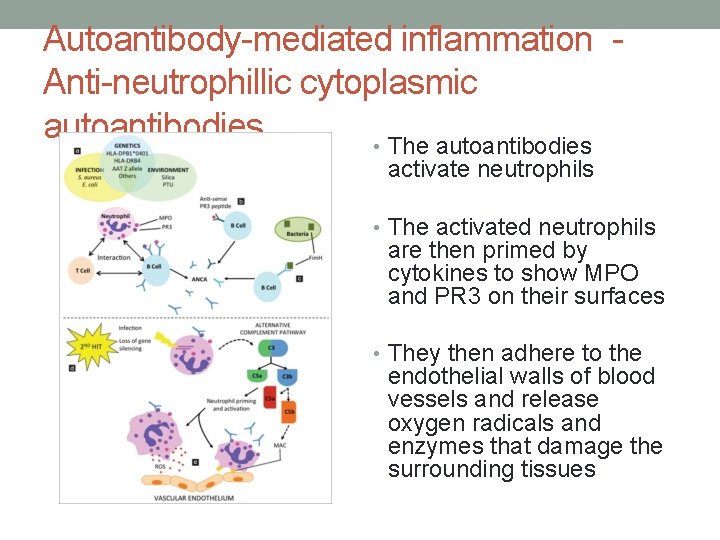

Autoantibody-mediated inflammation Anti-neutrophillic cytoplasmic autoantibodies • The autoantibodies activate neutrophils • The activated neutrophils are then primed by cytokines to show MPO and PR 3 on their surfaces • They then adhere to the endothelial walls of blood vessels and release oxygen radicals and enzymes that damage the surrounding tissues

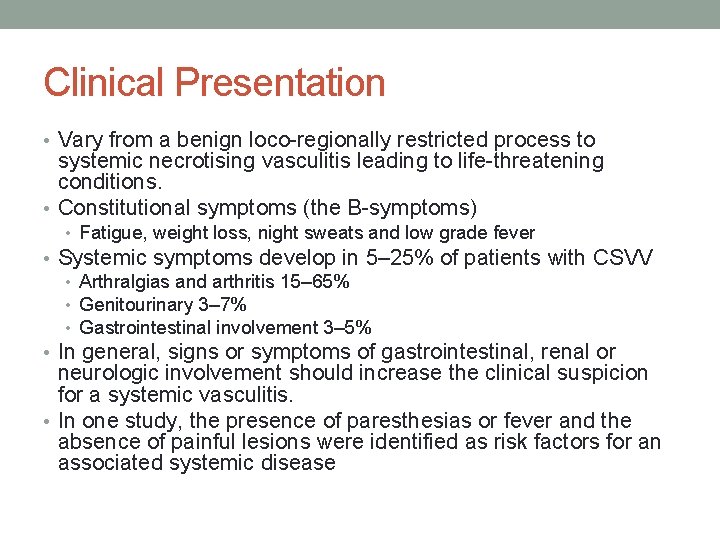

Clinical Presentation • Vary from a benign loco-regionally restricted process to systemic necrotising vasculitis leading to life-threatening conditions. • Constitutional symptoms (the B-symptoms) • Fatigue, weight loss, night sweats and low grade fever • Systemic symptoms develop in 5– 25% of patients with CSVV • Arthralgias and arthritis 15– 65% • Genitourinary 3– 7% • Gastrointestinal involvement 3– 5% • In general, signs or symptoms of gastrointestinal, renal or neurologic involvement should increase the clinical suspicion for a systemic vasculitis. • In one study, the presence of paresthesias or fever and the absence of painful lesions were identified as risk factors for an associated systemic disease

Think Vasculitis if? • Unexplained systemic illness • Symptoms of organ system ischaemia • Nephritic syndrome

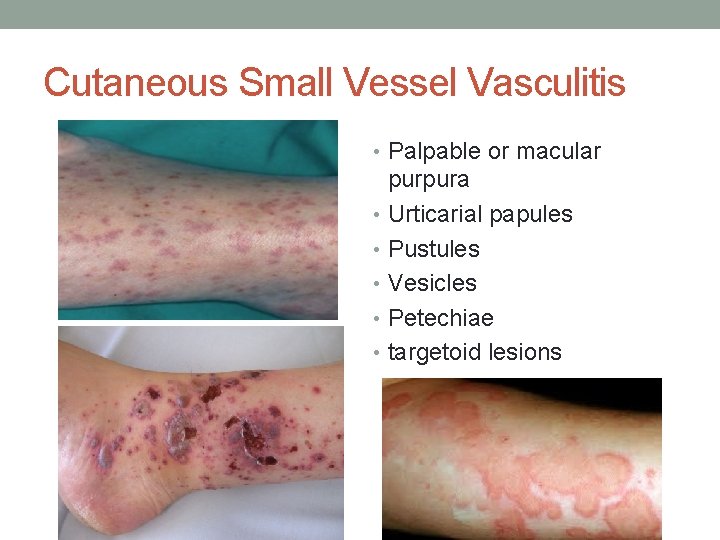

Cutaneous Small Vessel Vasculitis • The skin lesions of CSVV usually appear 7– 10 days after the triggering event. • In systemic vasculitic syndromes, signs of systemic involvement often precede the appearance of associated cutaneous lesions. • The lesions favor dependent sites, as well as areas under tight-fitting clothing, reflecting the influence of hydrostatic pressure and stasis on the pathophysiology. • In general, the lesions are asymptomatic, but they may itch, burn or sting.

Cutaneous Small Vessel Vasculitis • Palpable or macular purpura • Urticarial papules • Pustules • Vesicles • Petechiae • targetoid lesions

Small and medium-sized (“mixed”) • Cryoglobulinemia -Types II and III • Petechiae • Palpable purpura • ANCA-associated • Microscopic polyangiitis • Wegener’s granulomatosis • Churg–Strauss syndrome • Livedo racemosa • Retiform purpura • Ulcers • Secondary causes • Infections • Inflammatory disorders (e. g. AICTD) • Subcutaneous nodules • Digital necrosis

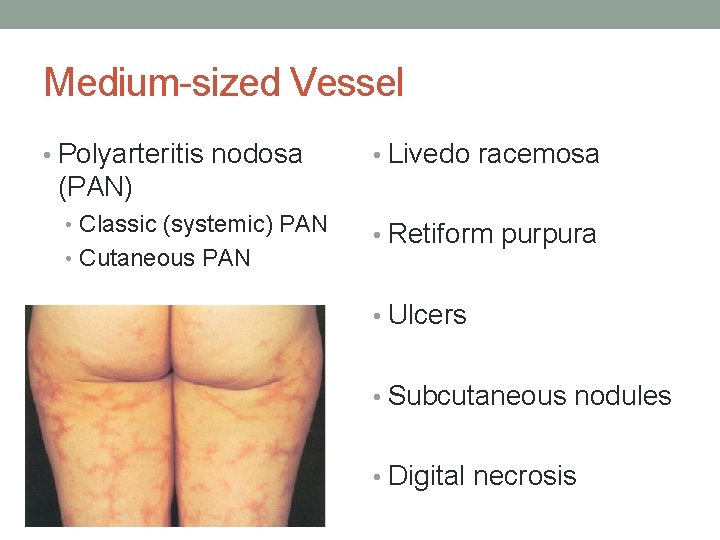

Medium-sized Vessel • Polyarteritis nodosa • Livedo racemosa (PAN) • Classic (systemic) PAN • Cutaneous PAN • Retiform purpura • Ulcers • Subcutaneous nodules • Digital necrosis

Large Vessel • Temporal Arteritis • Early – erythematous or cyanotic skin, alopecia, purpura, tender nodules on frontotemporal scalp • Late – Ulceration and/or gangrene of frontotemporal scalp or tongue • Takayasu’s arteritis • Erythematous subcutaneous nodules +/− ulceration, pyoderma gangrenosum-like lesions on the extremities (lower > upper) • May have evidence of small and/or medium-sized vessel vasculitis

Mimics of vasculitis • Infections • Embolic disorders • Malignancy • Drugs

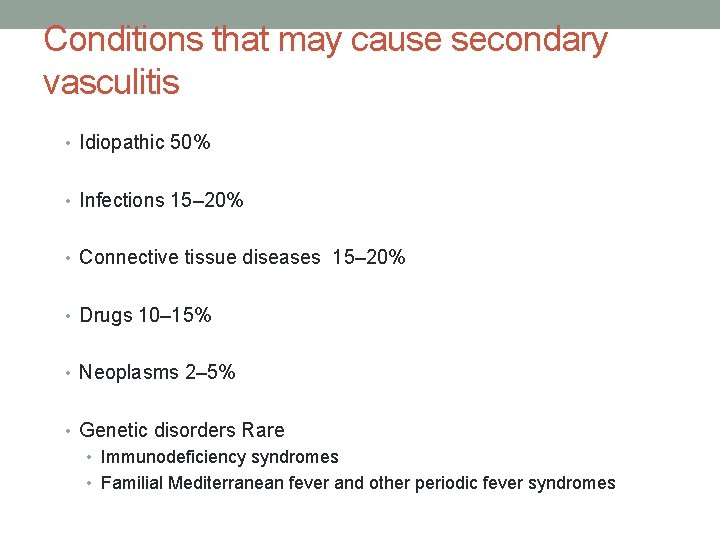

Conditions that may cause secondary vasculitis • Idiopathic 50% • Infections 15– 20% • Connective tissue diseases 15– 20% • Drugs 10– 15% • Neoplasms 2– 5% • Genetic disorders Rare • Immunodeficiency syndromes • Familial Mediterranean fever and other periodic fever syndromes

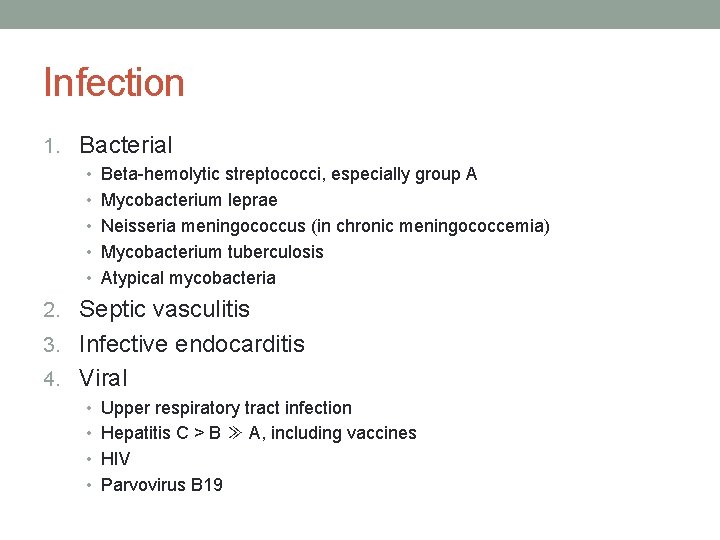

Infection 1. Bacterial • Beta-hemolytic streptococci, especially group A • Mycobacterium leprae • Neisseria meningococcus (in chronic meningococcemia) • Mycobacterium tuberculosis • Atypical mycobacteria 2. Septic vasculitis 3. Infective endocarditis 4. Viral • Upper respiratory tract infection • Hepatitis C > B ≫ A, including vaccines • HIV • Parvovirus B 19

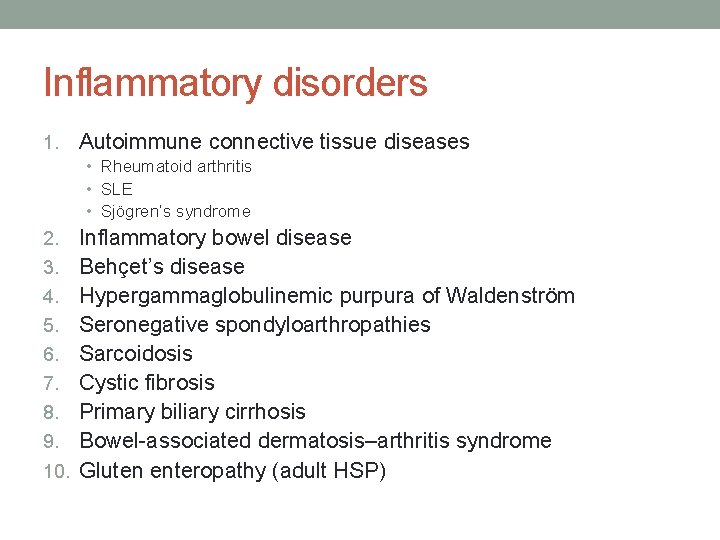

Inflammatory disorders 1. Autoimmune connective tissue diseases • Rheumatoid arthritis • SLE • Sjögren’s syndrome 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Inflammatory bowel disease Behçet’s disease Hypergammaglobulinemic purpura of Waldenström Seronegative spondyloarthropathies Sarcoidosis Cystic fibrosis Primary biliary cirrhosis Bowel-associated dermatosis–arthritis syndrome Gluten enteropathy (adult HSP)

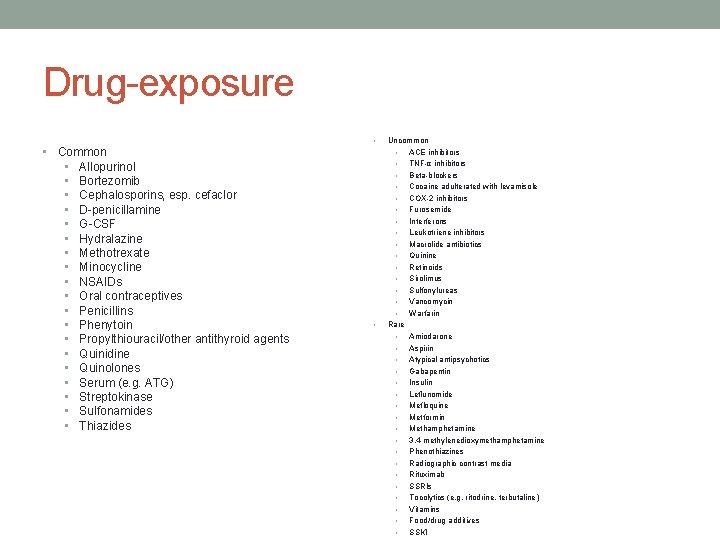

Drug-exposure • • Common • Allopurinol • Bortezomib • Cephalosporins, esp. cefaclor • D-penicillamine • G-CSF • Hydralazine • Methotrexate • Minocycline • NSAIDs • Oral contraceptives • Penicillins • Phenytoin • Propylthiouracil/other antithyroid agents • Quinidine • Quinolones • Serum (e. g. ATG) • Streptokinase • Sulfonamides • Thiazides • Uncommon • ACE inhibitors • TNF-α inhibitors • Beta-blockers • Cocaine adulterated with levamisole • COX-2 inhibitors • Furosemide • Interferons • Leukotriene inhibitors • Macrolide antibiotics • Quinine • Retinoids • Sirolimus • Sulfonylureas • Vancomycin • Warfarin Rare • Amiodarone • Aspirin • Atypical antipsychotics • Gabapentin • Insulin • Leflunomide • Mefloquine • Metformin • Methamphetamine • 3, 4 -methylenedioxymethamphetamine • Phenothiazines • Radiographic contrast media • Rituximab • SSRIs • Tocolytics (e. g. ritodrine, terbutaline) • Vitamins • Food/drug additives • SSKI

Neoplasms • Plasma cell dyscrasias • Monoclonal gammopathies • Multiple myeloma • Myelodysplasia • Myeloproliferative disorders • Lymphoproliferative disorders • Hairy cell leukemia • Solid organ carcinomas (adults with Ig. A-positive vasculitis)

Skin Biopsy • Within the first 24 to 48 hours of appearance • > 48 to 72 hours may have a predominantly mononuclear rather • • • than neutrophilic infiltrate Perilesional skin for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) ~80% of cases of CSVV DIF demonstrates deposition of C 3, Ig. M, Ig. A and/or Ig. G in a granular pattern within the vessel walls Immunoglobulin deposition is highest (up to 100%) in skin lesions present for ≤ 48 hours. 30% of samples obtained 48– 72 hours after lesion onset, DIF will be negative for immunoglobulins, and only C 3 will be detected in lesions present for >72 hours. In ANCA-positive vasculitis, the DIF of lesional skin is usually negative.

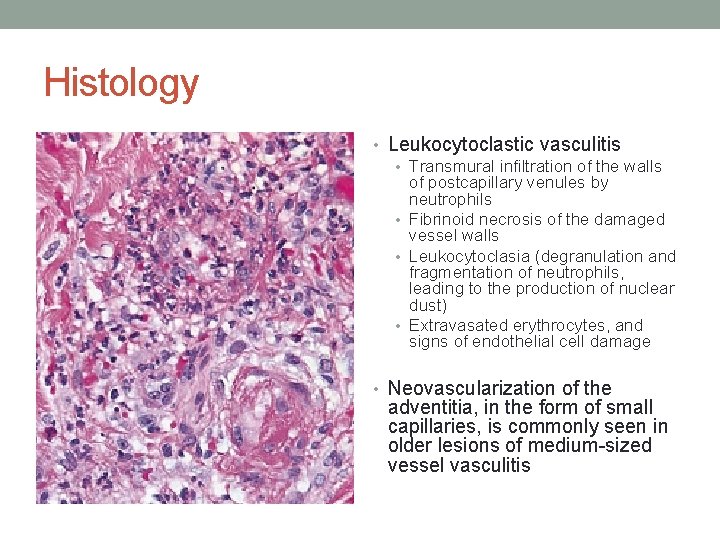

Histology • Leukocytoclastic vasculitis • Transmural infiltration of the walls of postcapillary venules by neutrophils • Fibrinoid necrosis of the damaged vessel walls • Leukocytoclasia (degranulation and fragmentation of neutrophils, leading to the production of nuclear dust) • Extravasated erythrocytes, and signs of endothelial cell damage • Neovascularization of the adventitia, in the form of small capillaries, is commonly seen in older lesions of medium-sized vessel vasculitis

Prognosis • Depends upon the severity of systemic involvement • ~ 90% spontaneous resolution of cutaneous lesions within several weeks or a few months • 10% will have chronic or recurrent disease at intervals of months to years • Average duration of disease activity is 28 months • The presence of arthralgias or cryoglobulinemia and an absence of fever may portend chronicity • Autoimmune connective tissue disease or neoplasm, will also affect prognosis

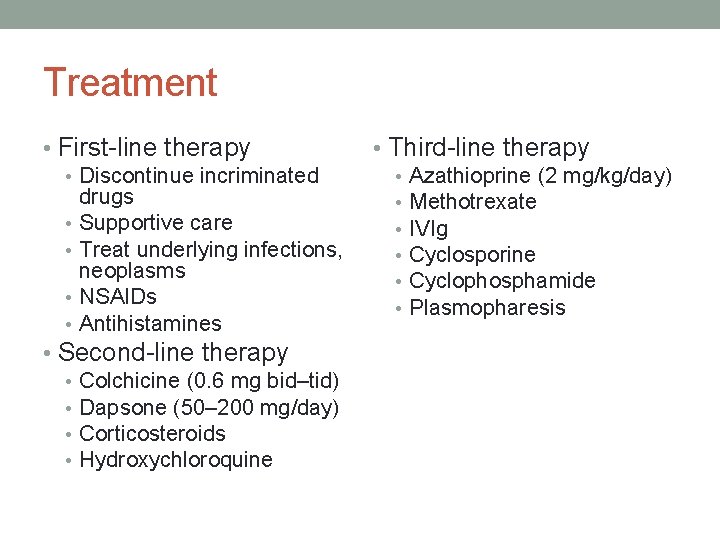

Treatment • First-line therapy • Discontinue incriminated drugs • Supportive care • Treat underlying infections, neoplasms • NSAIDs • Antihistamines • Second-line therapy • Colchicine (0. 6 mg bid–tid) • Dapsone (50– 200 mg/day) • Corticosteroids • Hydroxychloroquine • Third-line therapy • Azathioprine (2 mg/kg/day) • Methotrexate • IVIg • Cyclosporine • Cyclophosphamide • Plasmopharesis

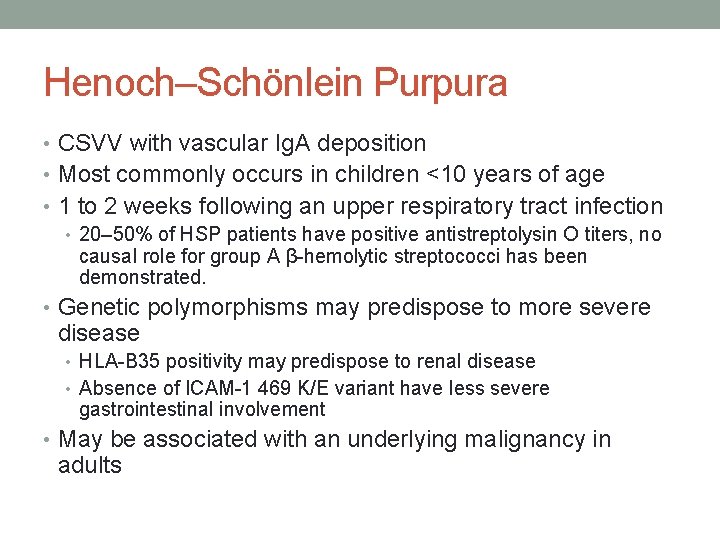

Henoch–Schönlein Purpura • CSVV with vascular Ig. A deposition • Most commonly occurs in children <10 years of age • 1 to 2 weeks following an upper respiratory tract infection • 20– 50% of HSP patients have positive antistreptolysin O titers, no causal role for group A β-hemolytic streptococci has been demonstrated. • Genetic polymorphisms may predispose to more severe disease • HLA-B 35 positivity may predispose to renal disease • Absence of ICAM-1 469 K/E variant have less severe gastrointestinal involvement • May be associated with an underlying malignancy in adults

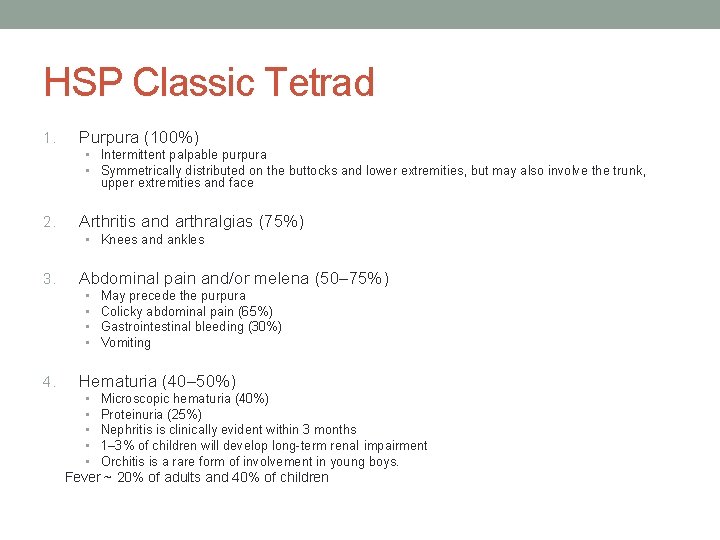

HSP Classic Tetrad 1. Purpura (100%) • Intermittent palpable purpura • Symmetrically distributed on the buttocks and lower extremities, but may also involve the trunk, upper extremities and face 2. Arthritis and arthralgias (75%) • Knees and ankles 3. Abdominal pain and/or melena (50– 75%) • • 4. May precede the purpura Colicky abdominal pain (65%) Gastrointestinal bleeding (30%) Vomiting Hematuria (40– 50%) • • • Microscopic hematuria (40%) Proteinuria (25%) Nephritis is clinically evident within 3 months 1– 3% of children will develop long-term renal impairment Orchitis is a rare form of involvement in young boys. Fever ~ 20% of adults and 40% of children

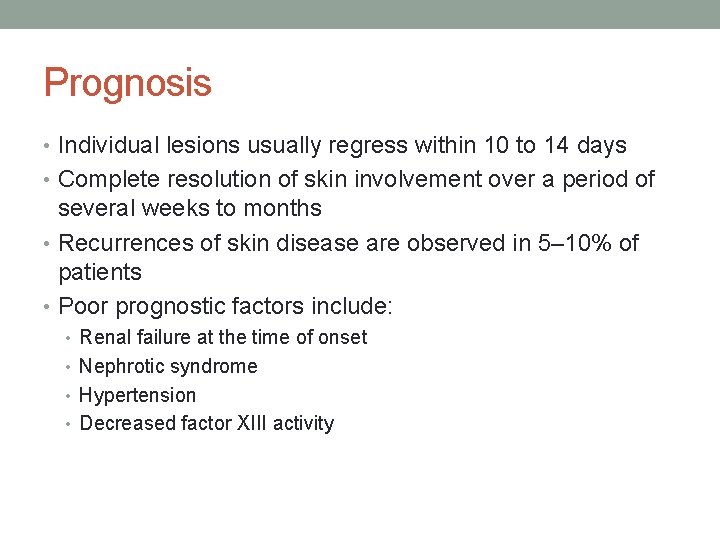

Prognosis • Individual lesions usually regress within 10 to 14 days • Complete resolution of skin involvement over a period of several weeks to months • Recurrences of skin disease are observed in 5– 10% of patients • Poor prognostic factors include: • Renal failure at the time of onset • Nephrotic syndrome • Hypertension • Decreased factor XIII activity

Adult HSP • Necrotic skin lesions are present in 60% of adults while cutaneous necrosis is observed in <5% of children • 30% will develop chronic renal insufficiency • Purpura above the waist • Fever • Elevated ESR • 60– 90% of patients with neoplasm-associated Ig. A vasculitis will have cancer of a solid organ - lung

Diagnosis • Leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the small dermal blood vessels • DIF demonstrates perivascular Ig. A, C 3 and fibrin deposits, Ig. A ANCA may be present in some patients • 80% of all adults with CSVV may demonstrate some vascular Ig. A deposition and Ig. A deposition can be seen in other diseases (e. g. drug hypersensitivity), a diagnosis of HSP is supported by Ig. A predominance in the correct clinical setting EULAR/PRe. S: • Palpable purpura and at least one of the following must be present: • • arthritis (acute, any joint) or arthralgia diffuse abdominal pain any biopsy demonstrating predominant Ig. A deposition renal involvement (hematuria and/or proteinuria) • Evidence of medium-sized vessel disease or widespread lesions (including the face) may indicate an underlying Ig. A paraproteinemia

Treatment • First-Line – Supportive care • Second-Line therapy • Dapsone • Colchicine • Corticosteroids • Azathioprine ± Corticosteroids • Cyclophosphamide ± Corticosteroids • Cyclosporine ± Corticosteroids • Antihistamines • Third-Line therapy • IVIg • Rituximab • Mycophenolate mofetil • Corticosteroids + tacrolimus • Aminocaproic acid • Plasmapharesis • Factor XIII

Cryoglobulinemic Vasculitis • Cryoglobulins are cold-precipitable immunoglobulins that can be divided into three subtypes, all of which have cutaneous manifestations • Palpable purpura, typically on the lower extremities • Myalgias and arthralgias (70%) • Associated with mixed serum cryoglobulins (Ig. M and Ig. G), most commonly in the setting of HCV infection • Peripheral neuropathy (Sensory – 40%) • Glomerulonephritis (Membranoproliferative -25%) • GI or Hepatitis (30%) – Viral or autoimmune hepatitis

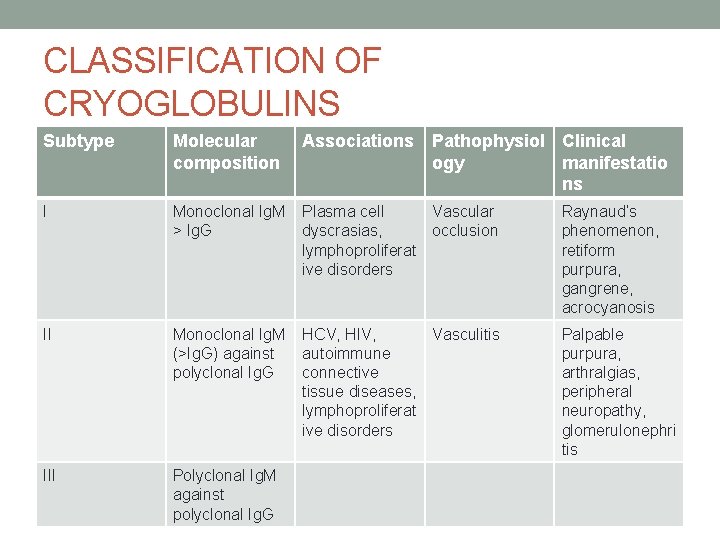

CLASSIFICATION OF CRYOGLOBULINS Subtype Molecular composition Associations Pathophysiol Clinical ogy manifestatio ns I Monoclonal Ig. M > Ig. G Plasma cell Vascular dyscrasias, occlusion lymphoproliferat ive disorders Raynaud’s phenomenon, retiform purpura, gangrene, acrocyanosis II Monoclonal Ig. M (>Ig. G) against polyclonal Ig. G HCV, HIV, Vasculitis autoimmune connective tissue diseases, lymphoproliferat ive disorders Palpable purpura, arthralgias, peripheral neuropathy, glomerulonephri tis III Polyclonal Ig. M against polyclonal Ig. G

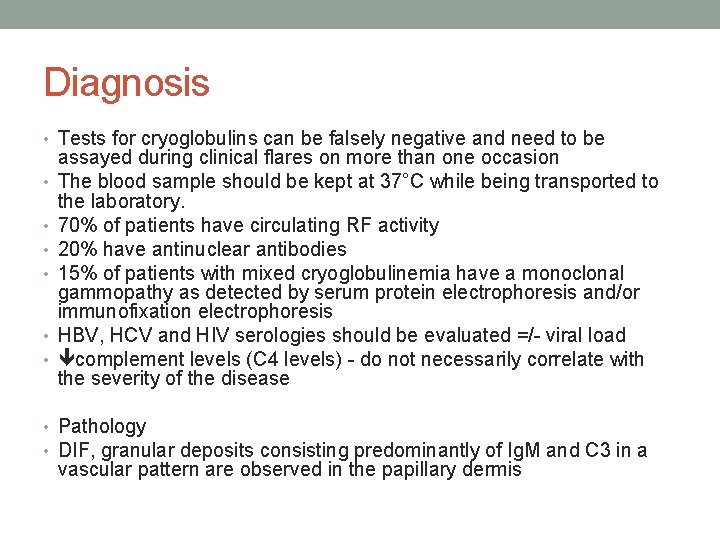

Diagnosis • Tests for cryoglobulins can be falsely negative and need to be • • • assayed during clinical flares on more than one occasion The blood sample should be kept at 37°C while being transported to the laboratory. 70% of patients have circulating RF activity 20% have antinuclear antibodies 15% of patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia have a monoclonal gammopathy as detected by serum protein electrophoresis and/or immunofixation electrophoresis HBV, HCV and HIV serologies should be evaluated =/- viral load complement levels (C 4 levels) - do not necessarily correlate with the severity of the disease • Pathology • DIF, granular deposits consisting predominantly of Ig. M and C 3 in a vascular pattern are observed in the papillary dermis

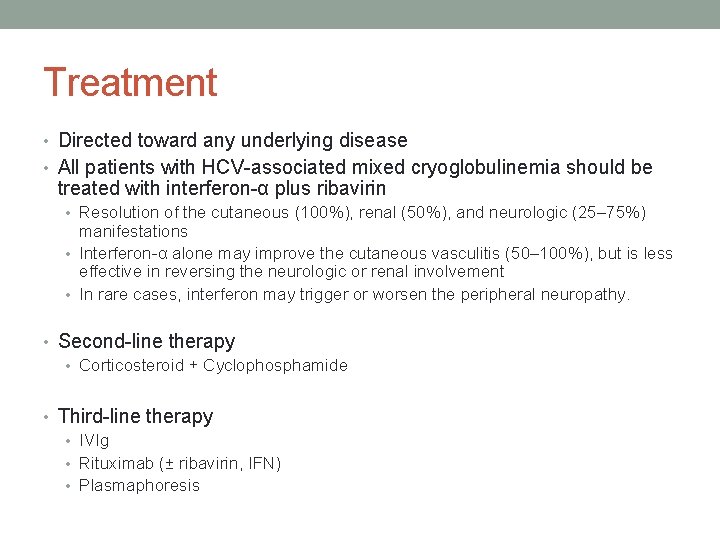

Treatment • Directed toward any underlying disease • All patients with HCV-associated mixed cryoglobulinemia should be treated with interferon-α plus ribavirin • Resolution of the cutaneous (100%), renal (50%), and neurologic (25– 75%) manifestations • Interferon-α alone may improve the cutaneous vasculitis (50– 100%), but is less effective in reversing the neurologic or renal involvement • In rare cases, interferon may trigger or worsen the peripheral neuropathy. • Second-line therapy • Corticosteroid + Cyclophosphamide • Third-line therapy • IVIg • Rituximab (± ribavirin, IFN) • Plasmaphoresis

Summary • Think Vasculitis if: Unexplained systemic illness, Symptoms of organ system ischaemia, Nephritic syndrome • Biopsy early lesions (24 -48 hrs) and send perilesional skin for Direct immunofluorescence • Always consider mimickers of Vasculitis first - Infections, embolic disorders, malignancy and drugs • Search for Secondary causes of CSVV – Infections, connective tissue diseases, drugs, neoplasms, rarely genetic disorders • Clinical Tetrad of HSP – palpable purpura, arthritis/arthralgia, abdominal pain and hematuria

References • Jennette JC, Falk RJ. Small‐vessel vasculitis. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 1512– 23. • Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2005 Aug; 7(4): 270 -5 • Lupus (1998) 7, 280± 284 Pathogenesis of vasculitis • Bolognia Dermatology 3 rd Ed. By Jean Bolognia • EULAR Textbook on Rheumatic Diseases, Johannes Bijlsma

• Major categories of non‐infectious vasculitis • • • • • • • • Large vessel vasculitis Giant cell arteritis Takayasu arteritis Medium‐sized vessel vasculitis Polyarteritis nodosa Kawasaki disease Small vessel vasculitis ANCA‐associated small vessel vasculitis MPA WG CSS Drug‐induced ANCA‐associated vasculitis Immune complex small vessel vasculitis Henoch–Schönlein purpura Cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis Lupus vasculitis Rheumatoid vasculitis Sjögren's syndrome vasculitis Hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis Behcet's disease Goodpasture's syndrome Serum sickness vasculitis Drug‐induced immune complex vasculitis Infection‐induced immune complex vasculitis Paraneoplastic small vessel vasculitis Lymphoproliferative neoplasm‐induced vasculitis Myeloproliferative neoplasm‐induced vasculitis Carcinoma‐induced vasculitis Inflammatory bowel disease vasculitis

Pathogenesis • CSVV - mediated by immune complexes that form in the presence of antigen excess. • Immune complex deposition in postcapillary venules activates complement, which, in turn, induces mast cell degranulation and neutrophil chemotaxis. Neutrophils release proteolytic enzymes and free oxygen radicals, leading to damage of the vessel wall (Fig. 24. 1 A). Increased adhesiveness between inflammatory cells and the endothelium, due to enhanced expression of adhesion molecules (e. g. selectins, LFA-1), also plays a role in the pathogenesis of cutaneous vasculitis

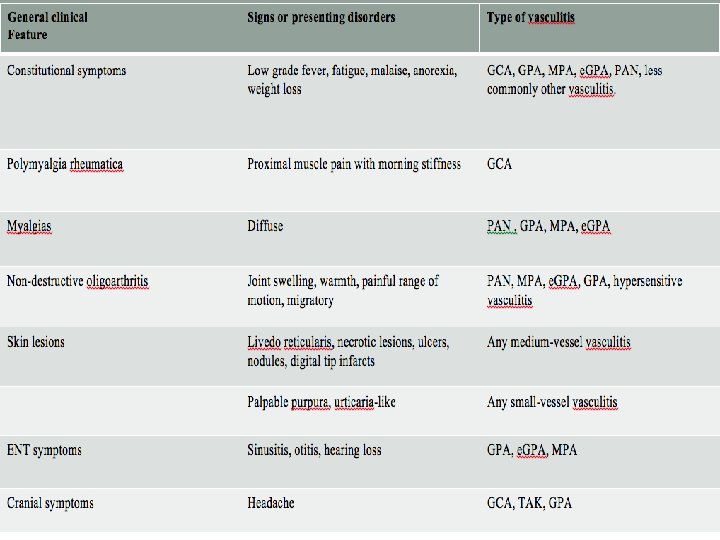

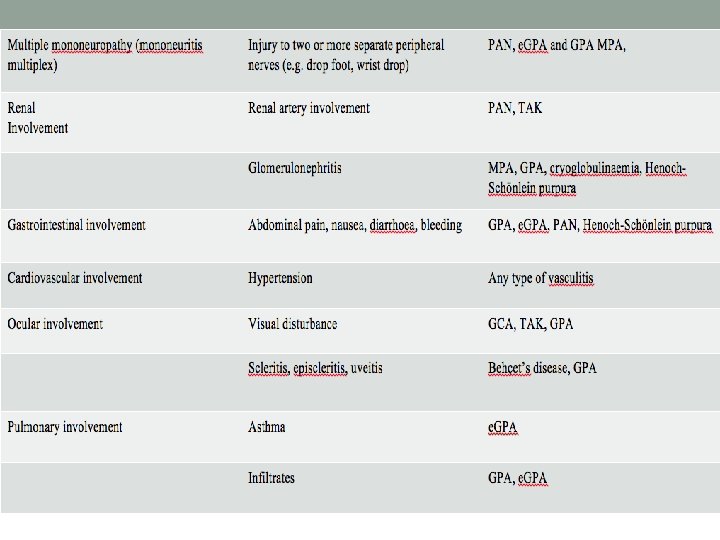

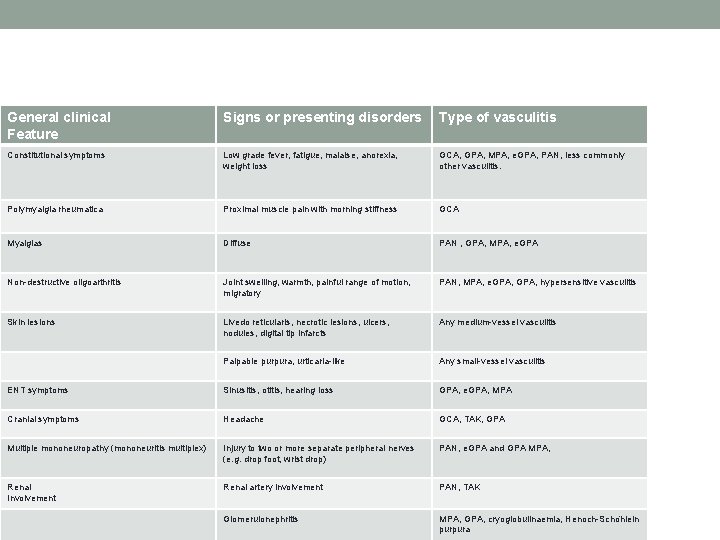

General clinical Feature Signs or presenting disorders Type of vasculitis Constitutional symptoms Low grade fever, fatigue, malaise, anorexia, weight loss GCA, GPA, MPA, e. GPA, PAN, less commonly other vasculitis. Polymyalgia rheumatica Proximal muscle pain with morning stiffness GCA Myalgias Diffuse PAN , GPA, MPA, e. GPA Non-destructive oligoarthritis Joint swelling, warmth, painful range of motion, migratory PAN, MPA, e. GPA, hypersensitive vasculitis Skin lesions Livedo reticularis, necrotic lesions, ulcers, nodules, digital tip infarcts Any medium-vessel vasculitis Palpable purpura, urticaria-like Any small-vessel vasculitis ENT symptoms Sinusitis, otitis, hearing loss GPA, e. GPA, MPA Cranial symptoms Headache GCA, TAK, GPA Multiple mononeuropathy (mononeuritis multiplex) Injury to two or more separate peripheral nerves (e. g. drop foot, wrist drop) PAN, e. GPA and GPA MPA, Renal Involvement Renal artery involvement PAN, TAK Glomerulonephritis MPA, GPA, cryoglobulinaemia, Henoch-Scho nlein purpura

• Eosinophilia and elevated Ig. E in the blood and tissues (in situ) are characteristically associated with allergic angiitis and granulomatosis eg. Churg–Strauss syndrome’; CSS

Pathogenesis of Vasculitis

Anti-neutrophillic cytoplasmic autoantibodies • Primarily directed against intracellular neutrophilic proteins (e. g. proteinase-3, myeloperoxidase), which can translocate to the neutrophil’s cell surface following primary activation by cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. • Binding to the surface of neutrophils results in neutrophilmediated vessel damage. • Because the vessel damage in ANCA-positive vasculitides is directly mediated by neutrophils rather than by immune complex deposition, they are referred to as “pauci-immune” vasculitides. • Formation of ANCA may be related to an impairment in neutrophil apoptosis which results in a prolonged opportunity for autoantibody development

• In medium-sized vessel vasculitis, the affected blood vessels reside within the reticular dermis or subcutis. As a result, the latter typically presents with livedo racemosa, retiform purpura, ulcers, subcutaneous nodules and/or digital necrosis. In general, the presence of ulcers or necrosis suggests deeper arterial involvement. The combination of palpable purpura (or other signs of CSVV) plus signs of medium-sized vessel disease points to a “mixed” pattern of vasculitis (see Table 24. 1), as is seen in ANCA-associated vasculitides, mixed cryoglobulinemia, or autoimmune connective tissue disease-associated vasculitis. Since polyarteritis nodosa affects only medium-sized vessels, it rarely presents with cutaneous signs of small vessel involvement. • Arthralgias and arthritis as well as constitutional symptoms such as fever, weight loss and malaise can be manifestations of vasculitis of any size vessel 2. For patients with systemic involvement, presenting symptoms and signs (e. g. abdominal pain, paresthesias, hematuria) will vary according to the affected organs.

Small Vessel (Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis) • Henoch–Schönlein purpura • Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy • Urticarial vasculitis • Erythema elevatum diutinum • Secondary causes of CSVV: • Drug exposure • Infections • Malignancies, most often hematologic

- Slides: 57