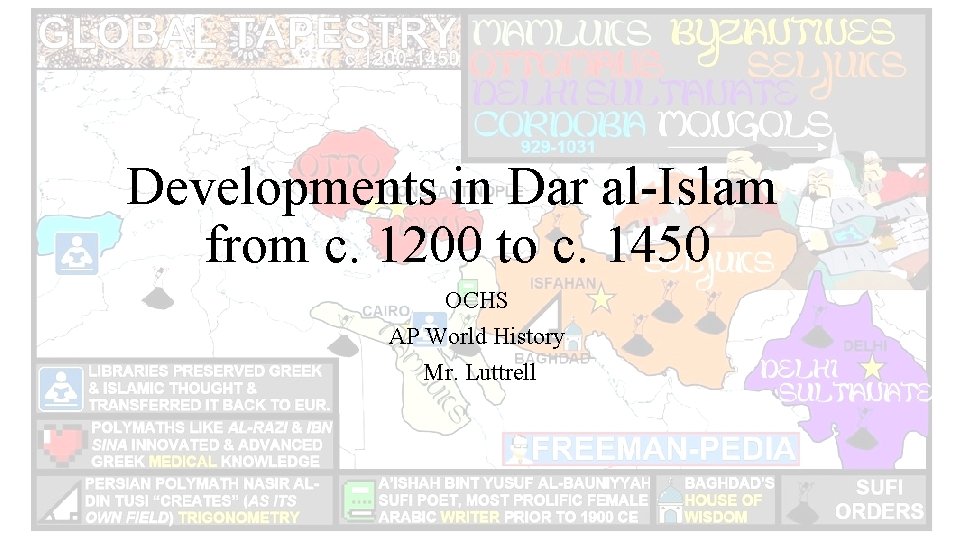

Developments in Dar alIslam from c 1200 to

- Slides: 20

Developments in Dar al-Islam from c. 1200 to c. 1450 OCHS AP World History Mr. Luttrell

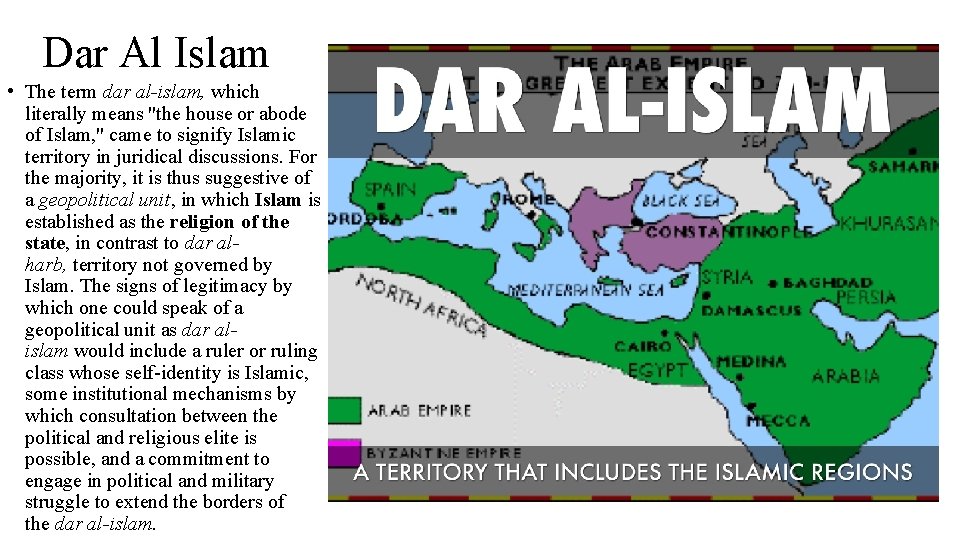

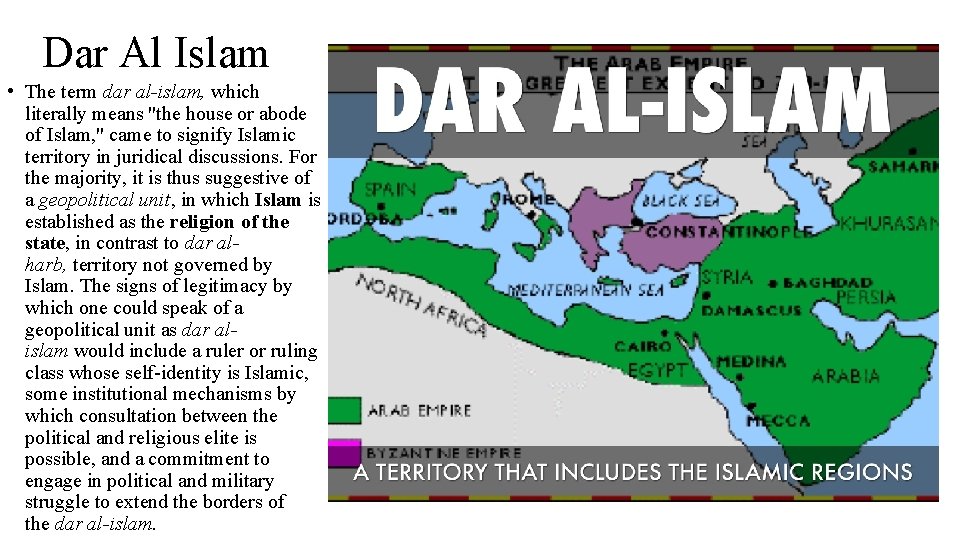

Dar Al Islam • The term dar al-islam, which literally means "the house or abode of Islam, " came to signify Islamic territory in juridical discussions. For the majority, it is thus suggestive of a geopolitical unit, in which Islam is established as the religion of the state, in contrast to dar alharb, territory not governed by Islam. The signs of legitimacy by which one could speak of a geopolitical unit as dar alislam would include a ruler or ruling class whose self-identity is Islamic, some institutional mechanisms by which consultation between the political and religious elite is possible, and a commitment to engage in political and military struggle to extend the borders of the dar al-islam.

THEME Essential Question Explain how systems of belief and their practices affected society in the period from c. 1200 to c. 1450. The development of ideas, beliefs, and religions illustrates how groups in society view themselves, and the interactions of societies and their beliefs often have political, social, and cultural implications.

Nizam al-Mulk, senior adviser to the sultan of the Muslim Seljuq Empire, The Book of Government, treatise composed circa 1092 “In the past, many [Muslim] rulers have had the following practices regarding the training of military slaves (ghulam): after young male slaves had been bought for government service, they would be given gradual advancement in rank, according to their length of service, education, skill, and general merit. Thus, after a ghulam had been bought, he would serve on foot as an assistant to a cavalryman for one year. After that, he would be given a horse and trained to ride for three more years. By his fourth year, he would receive a quiver of arrows and a bow case and would start training to shoot and fight. With each passing year of loyal service, his rank and honors would be increased, as would his responsibilities. He would become a troop leader and, finally, when he turned 35 years of age and assuming he had served the ruler honorably in every respect, he would be appointed governor of a province or would become a minister. Unfortunately, this system has not been followed by rulers lately. ”

THEME Essential Question Explain the causes and effects of the rise of Islamic states over time. A variety of internal and external factors contribute to state formation, expansion, and decline. Governments maintain order through a variety of administrative institutions, policies, and procedures, and governments obtain, retain, and exercise power in different ways and for different purposes.

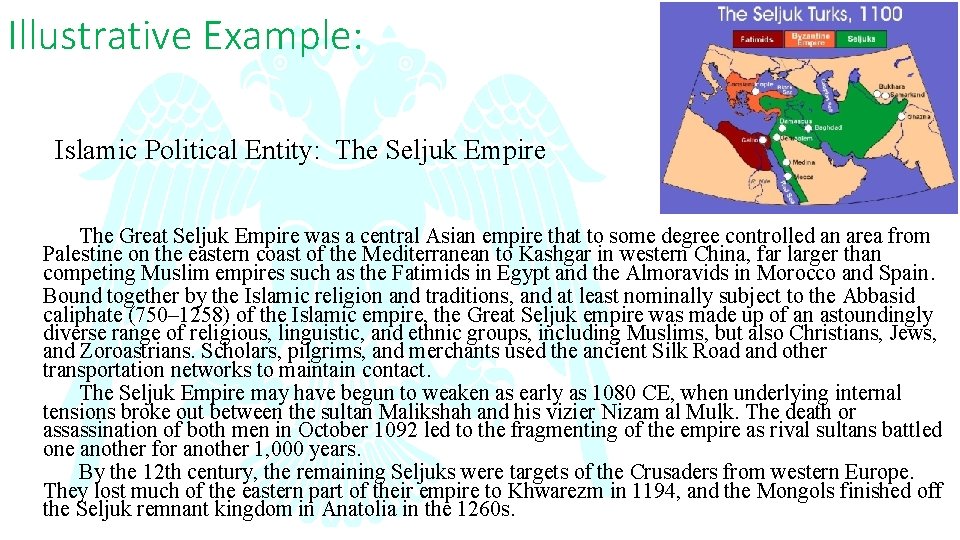

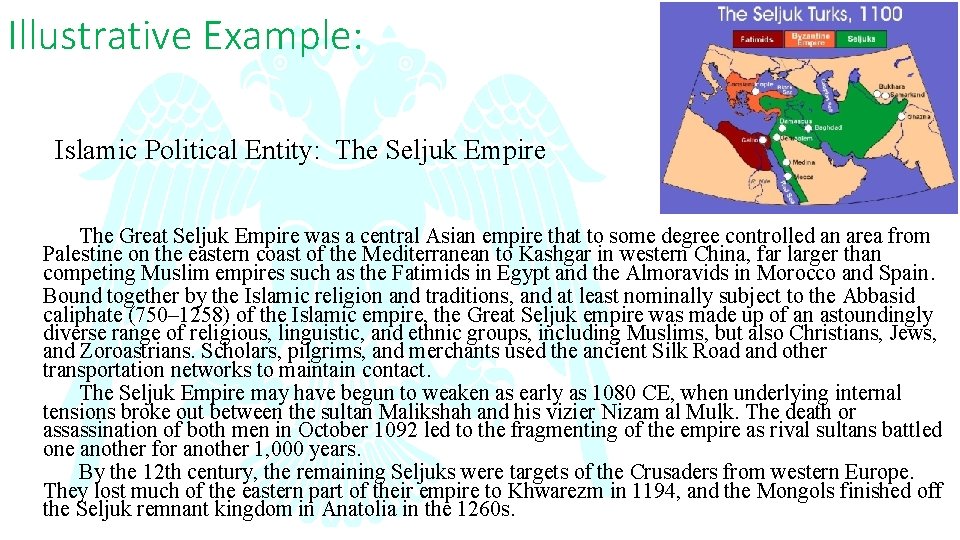

Illustrative Example: Islamic Political Entity: The Seljuk Empire The Great Seljuk Empire was a central Asian empire that to some degree controlled an area from Palestine on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean to Kashgar in western China, far larger than competing Muslim empires such as the Fatimids in Egypt and the Almoravids in Morocco and Spain. Bound together by the Islamic religion and traditions, and at least nominally subject to the Abbasid caliphate (750– 1258) of the Islamic empire, the Great Seljuk empire was made up of an astoundingly diverse range of religious, linguistic, and ethnic groups, including Muslims, but also Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians. Scholars, pilgrims, and merchants used the ancient Silk Road and other transportation networks to maintain contact. The Seljuk Empire may have begun to weaken as early as 1080 CE, when underlying internal tensions broke out between the sultan Malikshah and his vizier Nizam al Mulk. The death or assassination of both men in October 1092 led to the fragmenting of the empire as rival sultans battled one another for another 1, 000 years. By the 12 th century, the remaining Seljuks were targets of the Crusaders from western Europe. They lost much of the eastern part of their empire to Khwarezm in 1194, and the Mongols finished off the Seljuk remnant kingdom in Anatolia in the 1260 s.

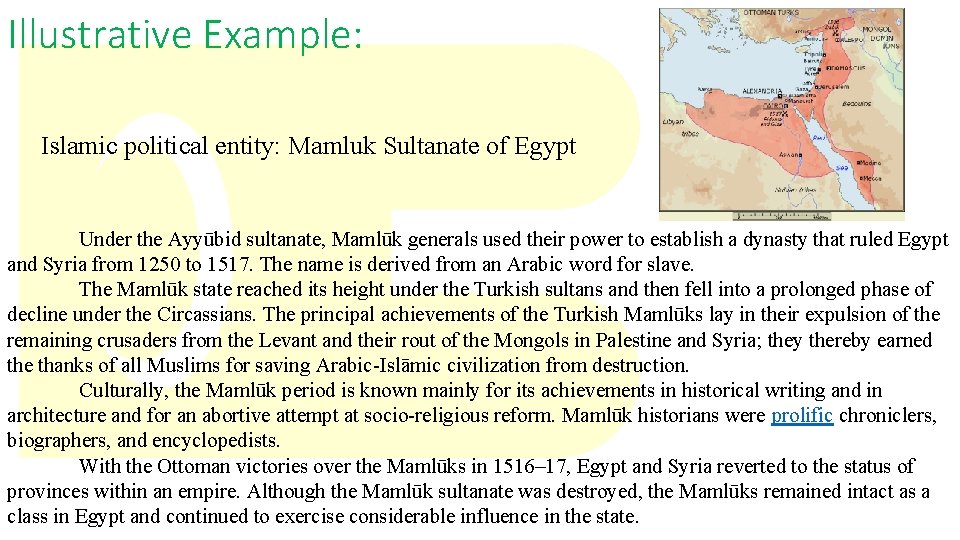

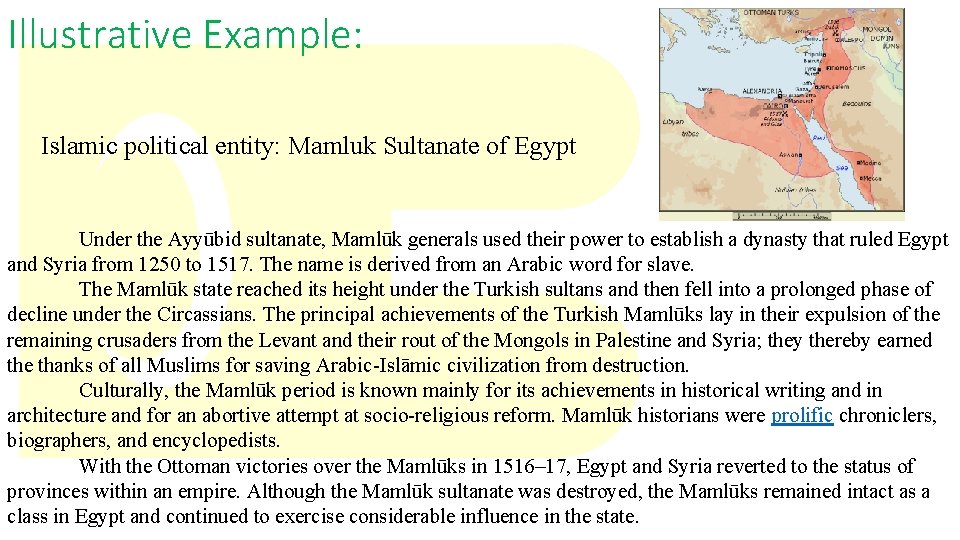

Illustrative Example: Islamic political entity: Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt Under the Ayyūbid sultanate, Mamlūk generals used their power to establish a dynasty that ruled Egypt and Syria from 1250 to 1517. The name is derived from an Arabic word for slave. The Mamlūk state reached its height under the Turkish sultans and then fell into a prolonged phase of decline under the Circassians. The principal achievements of the Turkish Mamlūks lay in their expulsion of the remaining crusaders from the Levant and their rout of the Mongols in Palestine and Syria; they thereby earned the thanks of all Muslims for saving Arabic-Islāmic civilization from destruction. Culturally, the Mamlūk period is known mainly for its achievements in historical writing and in architecture and for an abortive attempt at socio-religious reform. Mamlūk historians were prolific chroniclers, biographers, and encyclopedists. With the Ottoman victories over the Mamlūks in 1516– 17, Egypt and Syria reverted to the status of provinces within an empire. Although the Mamlūk sultanate was destroyed, the Mamlūks remained intact as a class in Egypt and continued to exercise considerable influence in the state.

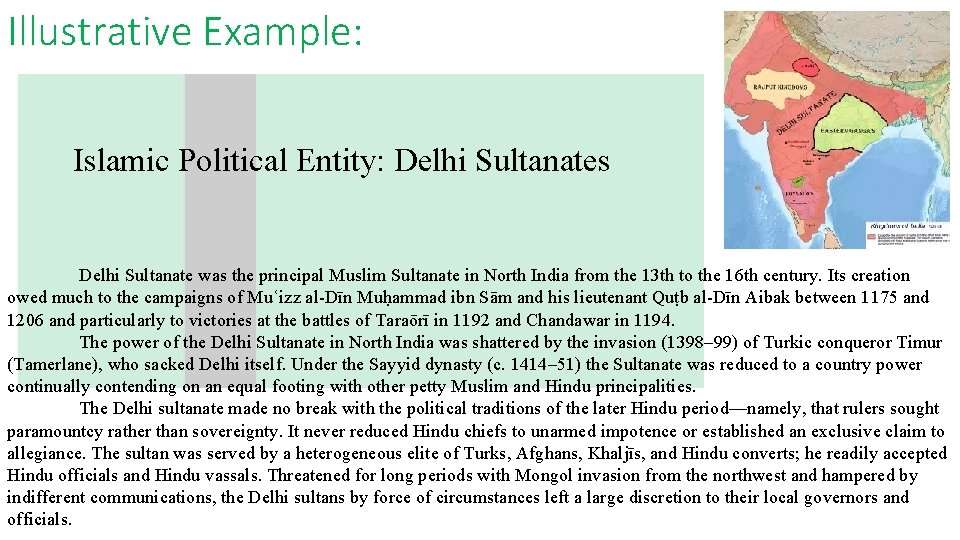

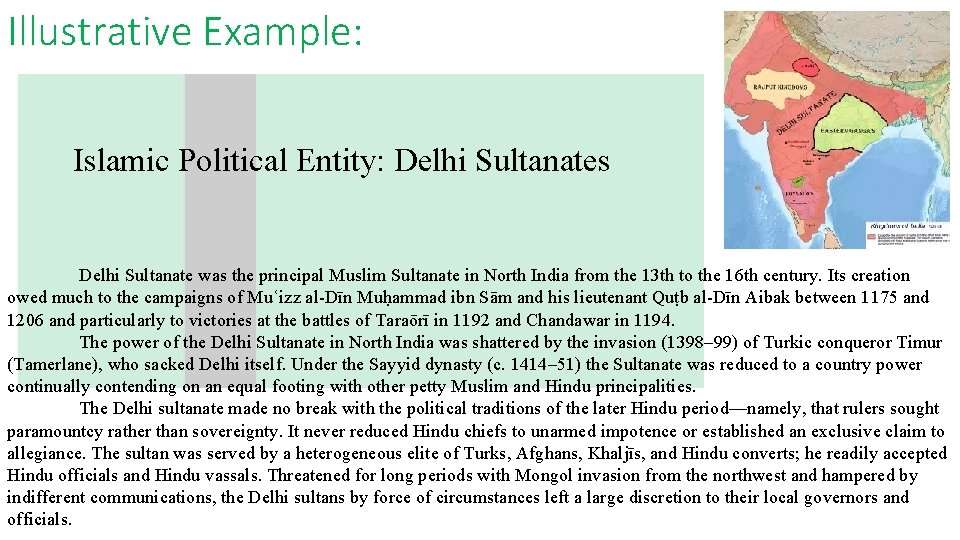

Illustrative Example: Islamic Political Entity: Delhi Sultanates Delhi Sultanate was the principal Muslim Sultanate in North India from the 13 th to the 16 th century. Its creation owed much to the campaigns of Muʿizz al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Sām and his lieutenant Quṭb al-Dīn Aibak between 1175 and 1206 and particularly to victories at the battles of Taraōrī in 1192 and Chandawar in 1194. The power of the Delhi Sultanate in North India was shattered by the invasion (1398– 99) of Turkic conqueror Timur (Tamerlane), who sacked Delhi itself. Under the Sayyid dynasty (c. 1414– 51) the Sultanate was reduced to a country power continually contending on an equal footing with other petty Muslim and Hindu principalities. The Delhi sultanate made no break with the political traditions of the later Hindu period—namely, that rulers sought paramountcy rather than sovereignty. It never reduced Hindu chiefs to unarmed impotence or established an exclusive claim to allegiance. The sultan was served by a heterogeneous elite of Turks, Afghans, Khaljīs, and Hindu converts; he readily accepted Hindu officials and Hindu vassals. Threatened for long periods with Mongol invasion from the northwest and hampered by indifferent communications, the Delhi sultans by force of circumstances left a large discretion to their local governors and officials.

THEME Essential Question Explain the effects of intellectual innovation in Dar al-Islam. Human adaptation and innovation have resulted in increased efficiency, comfort, and security, and technological advances have shaped human development and interactions with both intended and unintended consequences.

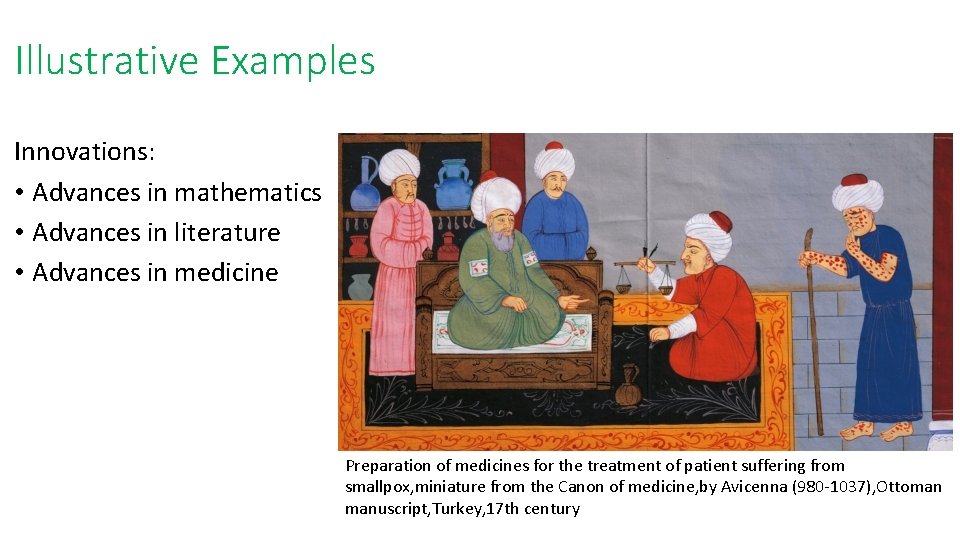

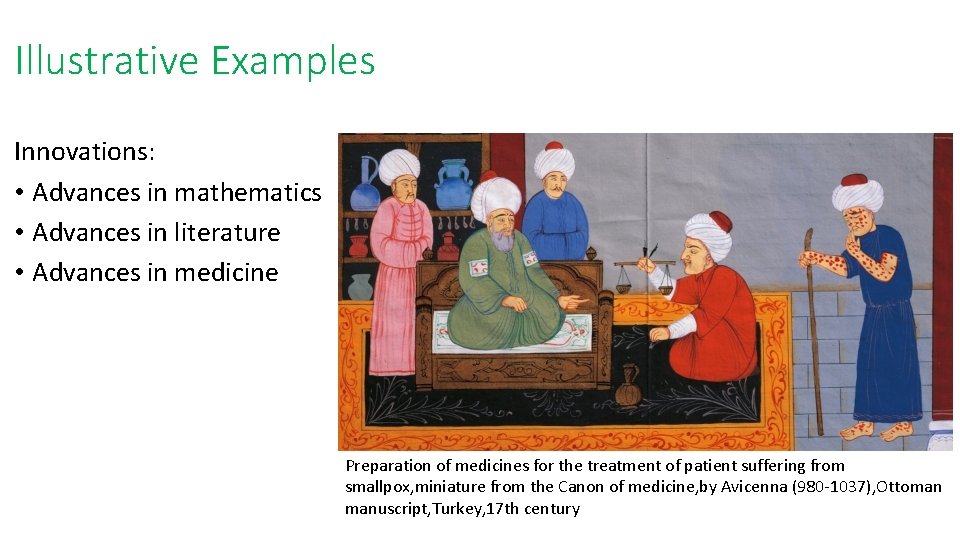

Illustrative Examples Innovations: • Advances in mathematics • Advances in literature • Advances in medicine Preparation of medicines for the treatment of patient suffering from smallpox, miniature from the Canon of medicine, by Avicenna (980 -1037), Ottoman manuscript, Turkey, 17 th century

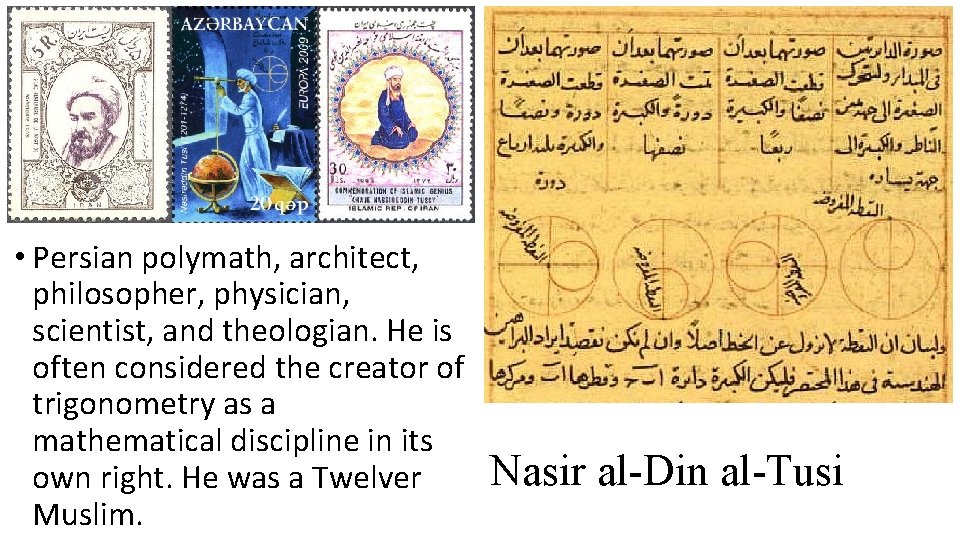

• Persian polymath, architect, philosopher, physician, scientist, and theologian. He is often considered the creator of trigonometry as a mathematical discipline in its own right. He was a Twelver Muslim. Nasir al-Din al-Tusi

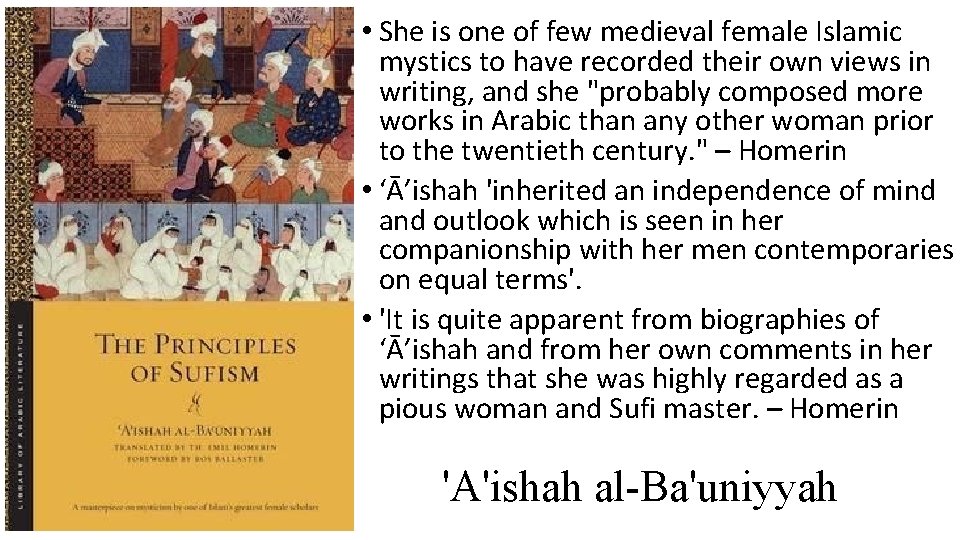

• She is one of few medieval female Islamic mystics to have recorded their own views in writing, and she "probably composed more works in Arabic than any other woman prior to the twentieth century. " – Homerin • ‘Ā’ishah 'inherited an independence of mind and outlook which is seen in her companionship with her men contemporaries on equal terms'. • 'It is quite apparent from biographies of ‘Ā’ishah and from her own comments in her writings that she was highly regarded as a pious woman and Sufi master. – Homerin 'A'ishah al-Ba'uniyyah

Medicine in the medieval Islamic world In medieval times, Islamic thinkers elaborated theories of the ancient Greeks and made extensive medical discoveries. There was a wide-ranging interest in health and disease, and Islamic doctors and scholars wrote extensively, developing complex literature on medication, clinical practice, diseases, cures, treatments, and diagnoses. Often, in these medical texts, they incorporated theories relating to natural science, astrology, alchemy, religion, philosophy, and mathematics. In the "General Prologue" to the "Canterbury Tales, " contemporary English poet Geoffrey Chaucer referred to the authorities of Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariya' al-Razi, a Persian clinician, and Abu 'Ali al. Husayn ibn Sina, a renowned physician, among other Islamic polymaths. In fact, Western doctors first learned of Greek medicine, including the works of Hippocrates and Galen, by reading Arabic translations. Mansur ibn Ilyas: Anatomy of the human body ( , ﺗﺸﺮﻳﺢ ﺑﺪﻥ ﺍﻧﺴﺎﻥ Tashrīḥ -i badan-i insān), c. 1450, U. S. National Library of Medicine.

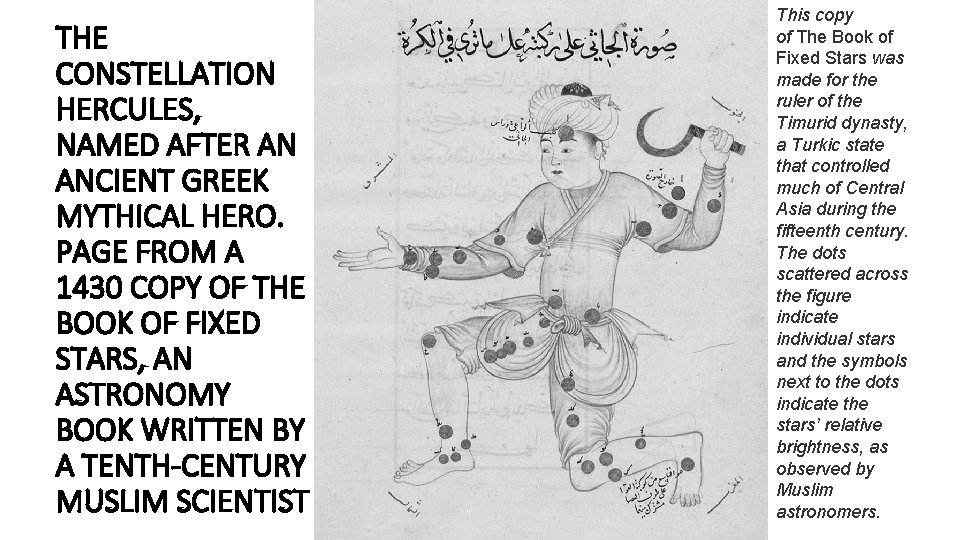

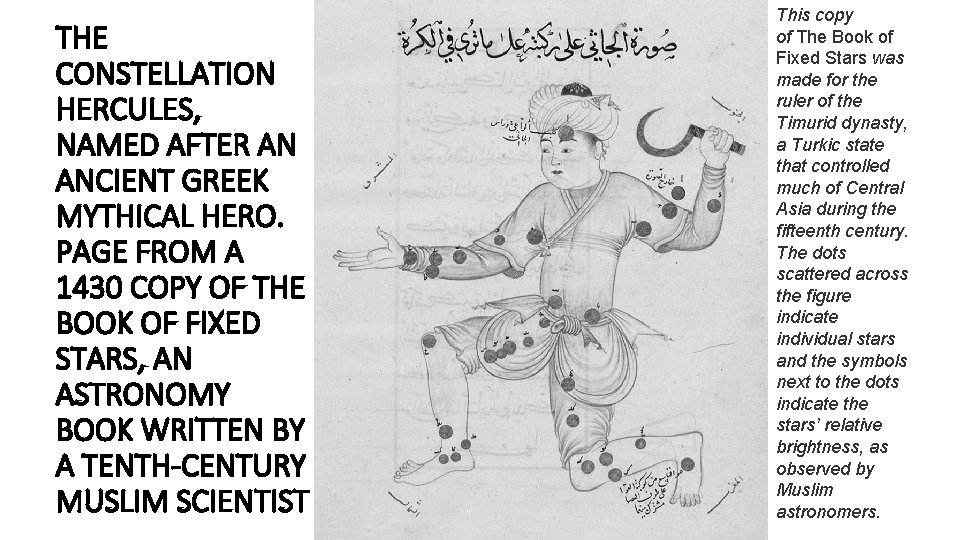

THE CONSTELLATION HERCULES, NAMED AFTER AN ANCIENT GREEK MYTHICAL HERO. PAGE FROM A 1430 COPY OF THE BOOK OF FIXED STARS, AN ASTRONOMY BOOK WRITTEN BY A TENTH-CENTURY MUSLIM SCIENTIST This copy of The Book of Fixed Stars was made for the ruler of the Timurid dynasty, a Turkic state that controlled much of Central Asia during the fifteenth century. The dots scattered across the figure indicate individual stars and the symbols next to the dots indicate the stars’ relative brightness, as observed by Muslim astronomers.

Illustrative Examples Transfers: • Preservation and commentaries on Greek moral and natural philosophy • House of Wisdom in Abbasid Bagdad • Scholarly and cultural transfers in Muslim and Christian Spain

How Arabic Translators Helped Preserve Greek Philosophy … and the Classical Tradition. History, June 15 th, 2017 In the ancient world, the language of philosophy—and therefore of science and medicine—was primarily Greek. “Even after the Roman conquest of the Mediterranean and the demise of paganism, philosophy was strongly associated with Hellenic culture, ” writes philosophy professor and History of Philosophy without any Gaps host Peter Adamson. “The leading thinkers of the Roman world, such as Cicero and Seneca, were steeped in Greek literature. ” And in the eastern empire, “the Greek-speaking Byzantines could continue to read Plato and Aristotle in the original. ” Greek thinkers also had significant influence in Egypt. During the building of the Library of Alexandria, “scholars copied and stored books that were borrowed, bought, and even stolen from other places in the Mediterranean, ” writes Aileen Das, Professor of Mediterranean Studies at the University of Michigan. “The librarians gathered texts circulating under the names of Plato (d. 348/347 BCE), Aristotle and Hippocrates (c. 460–c. 370 BCE), and published them as collections. ” The scroll above, part of an Aristotelian transcription of the Athenian constitution, was believed lost for hundreds of years until it was discovered in the 19 th century in Egypt, in the original Greek. The text, writes the British Library, "has had a major impact in our knowledge of the development of Athenian democracy and the workings of the Athenian city-state in antiquity. “ Alexandria “rivalled Athens and Rome as the place to study philosophy and medicine in the Mediterranean, ” and young men of means like the 6 th century priest Sergius of Reshaina, doctor-in-chief in Northern Syria, traveled there to learn the tradition. Sergius “translated around 30 works of Galen [the Greek physician]” and other known and unknown philosophers and ancient scientists into Syriac. Later, as Syriac and Arabic came to dominate former Greek-speaking regions, the Greek texts became intense objects of focus for Islamic thinkers, and the caliphs spared no expense to have them translated and disseminated, often contracting with Christian and Jewish scholars to accomplish the task. The transmission of Greek philosophy and medicine was an international phenomenon, which involved bilingual speakers from pagan, Christian, Muslim, and Jewish backgrounds. This movement spanned not only religious and linguistic but also geographical boundaries, for it occurred in cities as far apart as Baghdad in the East and Toledo in the West. In Baghdad, especially, by the 10 th century, “readers of Arabic, ” writes Adamson, “had about the same degree of access to Aristotle that readers of English do today” thanks to a “well-funded translation movement that unfolded during the Abbasid caliphate, beginning in the second half of the eighth century. ” The work done during the Abbasid period—from about 750 to 950—“generated a highly sophisticated scientific language and a massive amount of source material, ” we learn in Harvard University Press’s The Classical Tradition. Such material “would feed scientific research for the following centuries, not only in the Islamic world but beyond it, in Greek and Latin Christendom and, within it, among the Jewish populations as well. ” Indeed this “Byzantine humanism, ” as it’s called, “helped the classical tradition survive, at least to the large extent that it has. ” As ancient texts and traditions disappeared in Europe during the socalled “Dark Ages, ” Arabic and Syriac-speaking scholars and translators incorporated them into an Islamic philosophical tradition called falsafa. The motivations for fostering the study of Greek thought were complex. On the one hand, writes Adamson, the move was political; “the caliphs wanted to establish their own cultural hegemony, ” in competition with Persians and Greek-speaking Byzantine Christians, “benighted as they were by the irrationalities of Christian theology. ” On the other hand, “Muslim intellectuals also saw resources in the Greek texts for defending, and better understanding their own religion. ” One well-known figure from the period, al-Kindi, is thought to be the first philosopher to write in Arabic. He oversaw the translations of hundreds of texts by Christian scholars who read both Greek and Arabic, and he may also have added his own ideas to the works of Plotinus, for example, and other Greek thinkers. Like Thomas Aquinas a few hundred years later, al-Kindi attempted to “establish the identity of the first principle in Aristotle and Plotinus” as theistic God. In this way, Islamic translations of Greek texts prepared the way for interpretations that “treat that principle as a Creator, ” a central idea in Medieval scholastic philosophy and Catholic thought generally. The translations by al-Kindi and his associates are grouped into what scholars call the "circle of al-Kindi, " which preserved and elaborated on Aristotle and the Neoplatonists. Thanks to al-Kindi's "first set of translations, " notes the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "learned Muslims became acquainted with Plato's Demiurge and immortal soul; with Aristotle's search for science and knowledge of the causes of all the phenomena on earth and in the heavens, " and many more ancient Greek metaphysical doctrines. Later translators working under physician and scientist Hunayn ibn Ishaq and his son "made available in Syriac and/or Arabic other works by Plato, Aristotle, Theophrastus, some philosophical writings by Galen, " and other Greek thinkers and scientists. This tradition of translation, philosophical debate, and scientific discovery in Islamic societies continued into the 10 th and 11 th centuries, when Averroes, the "Islamic scholar who gave us modern philosophy, " wrote his commentary on the works of Aristotle. "For several centuries, " writes the University of Colorado's Robert Pasnau, "a series of brilliant philosophers and scientists made Baghdad the intellectual center of the medieval world, " preserving ancient Greek knowledge and wisdom that may otherwise have disappeared. When it seems in our study of history that the light of the ancient philosophy was extinguished in Western Europe, we need only look to North Africa and the Near East to see that tradition, with its humanistic exchange of ideas, flourishing for centuries in a world closely connected by trade and empire.

House of Wisdom in Abbasid Bagdad

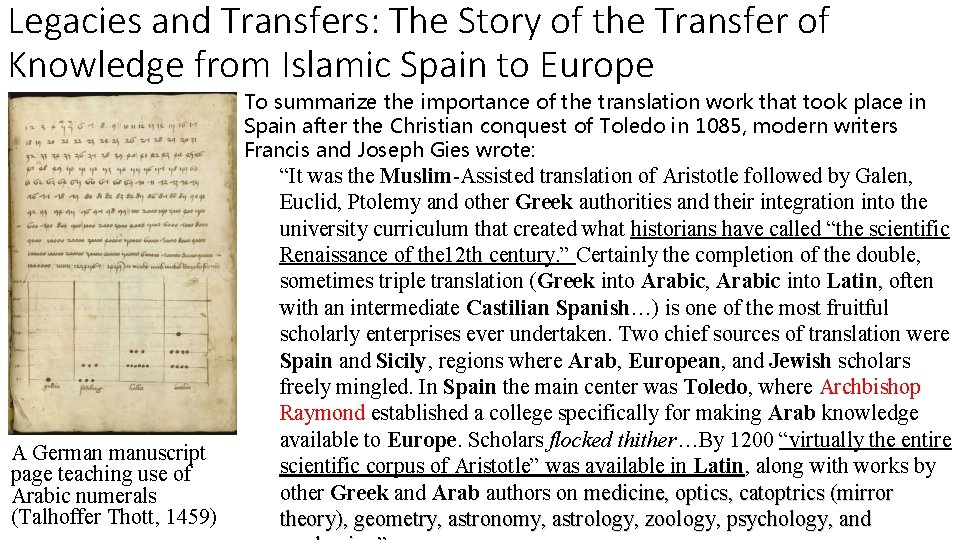

Legacies and Transfers: The Story of the Transfer of Knowledge from Islamic Spain to Europe To summarize the importance of the translation work that took place in Spain after the Christian conquest of Toledo in 1085, modern writers Francis and Joseph Gies wrote: A German manuscript page teaching use of Arabic numerals (Talhoffer Thott, 1459) “It was the Muslim-Assisted translation of Aristotle followed by Galen, Euclid, Ptolemy and other Greek authorities and their integration into the university curriculum that created what historians have called “the scientific Renaissance of the 12 th century. ” Certainly the completion of the double, sometimes triple translation (Greek into Arabic, Arabic into Latin, often with an intermediate Castilian Spanish…) is one of the most fruitful scholarly enterprises ever undertaken. Two chief sources of translation were Spain and Sicily, regions where Arab, European, and Jewish scholars freely mingled. In Spain the main center was Toledo, where Archbishop Raymond established a college specifically for making Arab knowledge available to Europe. Scholars flocked thither…By 1200 “virtually the entire scientific corpus of Aristotle” was available in Latin, along with works by other Greek and Arab authors on medicine, optics, catoptrics (mirror theory), geometry, astronomy, astrology, zoology, psychology, and