Developing Theoretical Perspectives from your Research Paul Ashwin

- Slides: 21

Developing Theoretical Perspectives from your Research Paul Ashwin, Department of Educational Research, Lancaster University p. ashwin@lancaster. ac. uk Tuesday 18 June 2013 Society for Research into Higher Education, London 1

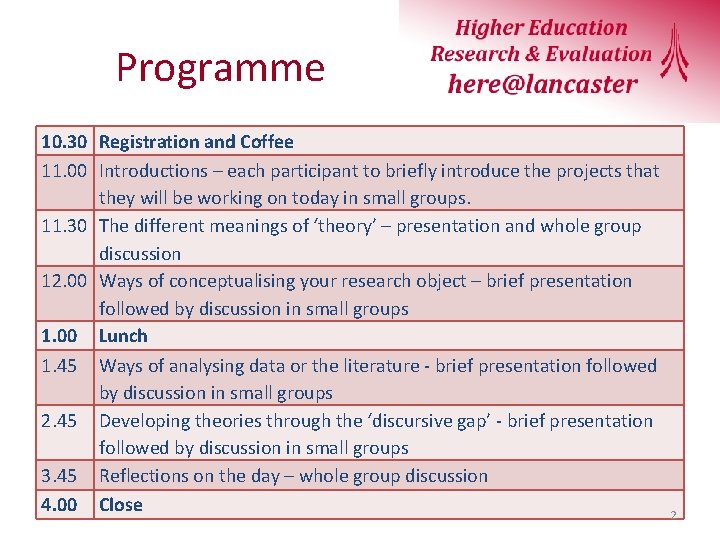

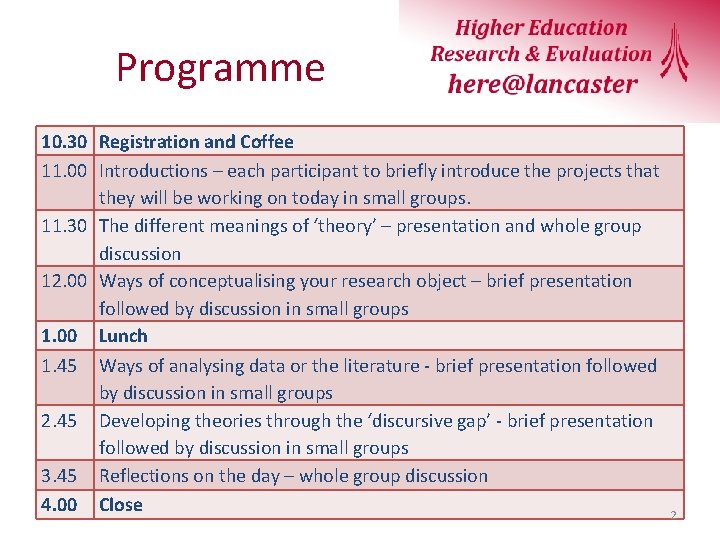

Programme 10. 30 Registration and Coffee 11. 00 Introductions – each participant to briefly introduce the projects that they will be working on today in small groups. 11. 30 The different meanings of ‘theory’ – presentation and whole group discussion 12. 00 Ways of conceptualising your research object – brief presentation followed by discussion in small groups 1. 00 Lunch 1. 45 Ways of analysing data or the literature - brief presentation followed by discussion in small groups 2. 45 Developing theories through the ‘discursive gap’ - brief presentation followed by discussion in small groups 3. 45 Reflections on the day – whole group discussion 4. 00 Close 2

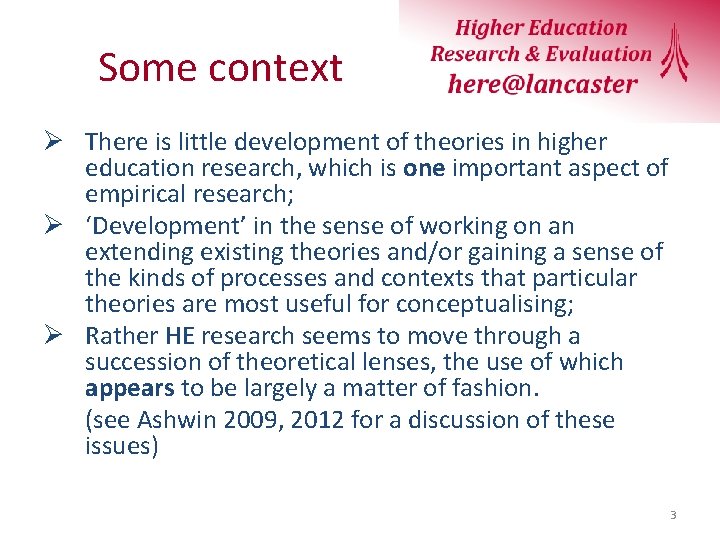

Some context Ø There is little development of theories in higher education research, which is one important aspect of empirical research; Ø ‘Development’ in the sense of working on an extending existing theories and/or gaining a sense of the kinds of processes and contexts that particular theories are most useful for conceptualising; Ø Rather HE research seems to move through a succession of theoretical lenses, the use of which appears to be largely a matter of fashion. (see Ashwin 2009, 2012 for a discussion of these issues) 3

WARNING: This event offers one way of developing theories. There are others. 4

Different meanings of ‘theories’ Ø Current debates around theories in educational research tend be all-ornothing affairs. Ø For example Thomas (1997, 2007) has repeatedly argued for a move away from theories, whilst others have argued (see for example Ball, 1995; Anyon et al. 2009) that it plays an essential role in educational research. Ø These debates seem to be sterile and repetitive (for a very similar debate see Gage 1978, 1994; Garrison, 1988; Garrison and Macmillan, 1994). Ø In a way these debates are too serious, which perhaps reflects a lack of confidence in the use of theories. Ø My argument is these debates around the role of theories do not take sufficient account of the different roles that theories play in different types of research and the different role that in can play within a particular type of research. 5

The use of theories in different educational practices Ø The different meanings of ‘theory’ have been discussed many times in educational research (for example see Chambers 1992; Thomas 2007; Hammersley 2012) Ø The meaning of ‘theory’ is relational (Alexander 1982; Abend 2008). Ø For this reason it is particularly important to be clear about the educational activity in relation to which theories are being discussed. v Differences between the role of theories in educative practices and carrying out educational research; v Differences between the roles of theories in empirical and conceptual research. Ø The strongest criticisms of the ways that theories are used in education research tend to elide these different practices and subtlety change the meaning of ‘theory’. 6

Theory’s secure place in qualitative inquiry is challenged on three counts. First, it is argued that the search for theory in such inquiry originates in a kind of crypto-functionalism, and makes any inquiry dependent on its discovery inconsistent with the starting points of qualitative inquiry. Second, theory’s supposed importance for policy formulation cannot in itself justify it. . . Third, arguments that it is used successfully and uncontroversially in the arts and humanities. Thomas (2002) 7

The roles of theories in empirical research into education Theories play three major roles in empirical research. Shaping: Ø how researchers see the objects of their research, Ø how they see their empirical data ; Ø how they relate these two different ways of seeing. These distinctions are not new ( for example see Carnap, 1956; Merton, 1968; Althusser, 1969; Barlett, 1991; Bernstein 2000) but in practice tend to get elided. 8

“Theory helps us to decide what and how we research. It helps us to measure and explain. It can be crucial in the transfer of research findings to new settings, and an important end-product of research”. Gorard (2004, p. 14) 9

Conceptualising research objects in empirical research Ø One of the key roles that theories play in empirical research is in allowing researchers to conceptualise the objects of their research (Bourdieu et al 1991; Garrison 1988; Rajagopalan 1998; Pring 2000). Ø Whilst many argue (for example Alexander 1987; Thomas 2002, 2007; Gardner 2011) that theories involve generalisations, in this role theories involve simplification. Ø In order to deal with this messy reality, we have to simplify our research objects by seeing them in certain ways and not others. Ø In higher education research, popular simplifications include: communities of practice, approaches to learning, actor-network theory, field-habitus-capital, 10

Question 1 Think about a single research project you are involved in. Ø How are you conceptualising your research object? Ø What alternatives have you considered? Ø Has this changed through the project? Please share your thoughts with the rest of your table. 11

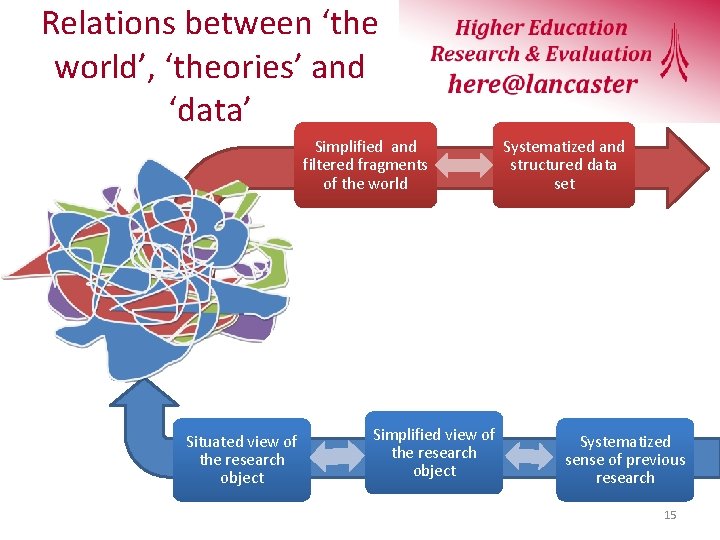

Generating and analysing data in empirical research Ø Theories are involved in many aspects including what counts as evidence in empirical research, the meaning of the data generated through particular research methods. Ø Data are simplified and filtered fragments of the empirical world. Ø These fragments are then ordered into systematised and structured data sets. Ø Theories of data generation tell us about how the data are filtered and simplified through research methods; Ø Theories of data analysis tell us about how to organise these data into systematised and structured data sets; Ø These are often elided with theories of research objects, but these are different kinds of theories. Ø Examples of these theories in higher education include: phenomenography, discourse analysis, interpretative phenomenological analysis 12

Question 2 Thinking again about the research project you discussed under question 1: Ø How did you generate and analyse your data or search for and analyse your literature? Ø Did your way of seeing your research object inform this? Ø Please share your thoughts with the rest of your table. 13

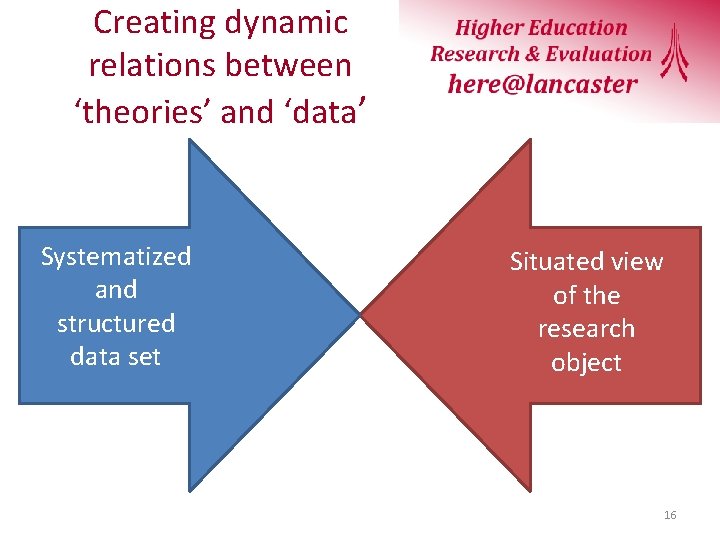

Relating research objects to data Ø How can we relate our views of our research object to the outcomes of our data analysis? Ø Most often done in terms of ‘theory’ explaining ‘data’. Ø This has led some to claim there is a problem with theorybuilding in educational research (for example see Thomas 2007; Kettley 2010). Ø My sense is that this is based on the ambiguity of the word ‘theory’ and can be addressed by: § Analytically separating views of research objects (theories) from data generation and analysis (data); § being more careful about what aspects of theories and data are brought into relation to each other. Ø This is something done more at the level of a project than a single paper. 14

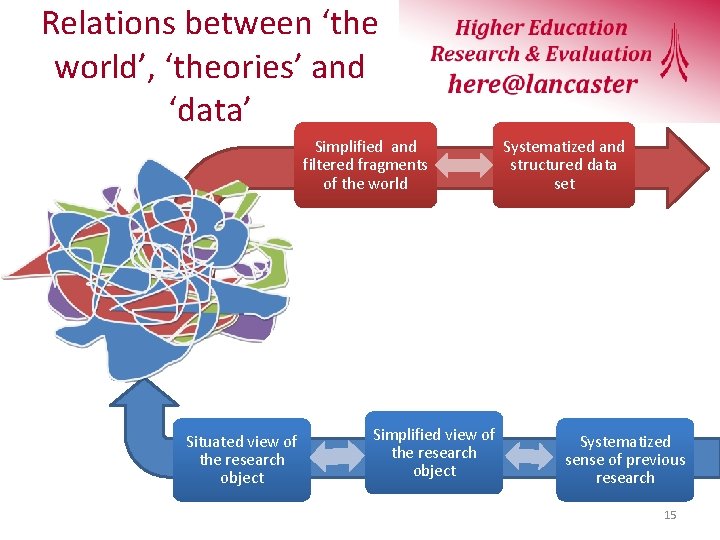

Relations between ‘the world’, ‘theories’ and ‘data’ Simplified and filtered fragments of the world Situated view of the research object Simplified view of the research object Systematized and structured data set Systematized sense of previous research 15

Creating dynamic relations between ‘theories’ and ‘data’ Systematized and structured data set Situated view of the research object 16

Question 3 Thinking again about the research project you discussed under question 1 and 2: Ø How does your way of seeing your research object relate to your way of analyse your data or literature? Ø Does it allow you to create a ‘discursive gap’? Ø Does this way of thinking help you to think about how you might develop theories? 17

Conclusions My argument is that in being clearer about the different roles of theories in empirical research in higher education, we can: Ø Develop more dynamic relations between theories and data Ø Extend theories and gain a better sense of the kinds of processes and contexts that particular theories are most useful for conceptualising; Ø Encourage a greater number of different ways of seeing research objects and generating and analysing data; Ø Encourage more dialogue about new and old ways of seeing higher education; Ø Become more playful and confident in the ways in which we research and think about higher education. 18

References Abend, G. (2008) The meaning of ‘theory’. Sociological Theory, 26, 2: 173 -199. Alexander, J. (1982) Positivism, Presuppositions, and Current Controversies: Theoretical Logic in Sociology, Volume One. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Althusser, L. (1969) For Marx. Translated by B. Brewster. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Anyon, J. , with M. Dumas, D. Linville, D. Nolan, M. Perez, E. Tuck, and J. Weiss. (2009) Theory and educational research: toward critical social explanation. New York and London: Routledge. Ashwin, P. (2009) Analysing teaching-learning interactions in higher education: accounting for structure and agency. London Continuum. Ashwin, P (2012) How often are theories developed through empirical research in higher education? Studies in Higher Education, 37: 941 -955. Ball, S. (1995) Intellectuals or technicians? The urgent role of theory in educational studies. British Journal of Educational Studies 43: 255 -271. Barlett, L. (1991) The dialectical relationship between theory and method in critical interpretative research. British Educational Research Journal 17, 1: 19 -33. Bernstein, B. (2000) Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: theory, research and critique. Rev. ed. Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. 19

Bourdieu, P. , J-C. Chamberon, and J-C. Passeron. (1991) The craft of sociology: epistemological preliminaries. Ed B. Krais, trans. R. Nice. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Carnap, R. (1956). The methodological character of theoretical concepts. Minnesota Studies in the Philosophy of Science 1: 38 -76. Chambers, J. (1992) Empiricist research on teaching: a philosophical and practical critique of its scientific pretensions. Dordrecht; Kluwer) Gage, N. (1978) The scientific basis of the art of teaching. New York: Teachers College Press, Columbia University. Gage, N. (1994) The scientific status of research on teaching. Educational Theory, 44: 371 -383. Gardner, J. (2011) Educational research : what (a) to do about impact. The 2010 Presidential Address. British Educational Research Journal, 37: 543 -561. Garrison, J. (1988) The impossibility of atheoretical educational science. The Journal of Educational Thought, 22: 21 -26. Garrison, J. and Macmillan, C. (1994) Process-product research on teaching; ten years later. Educational Theory, 44: 385 -397. 20

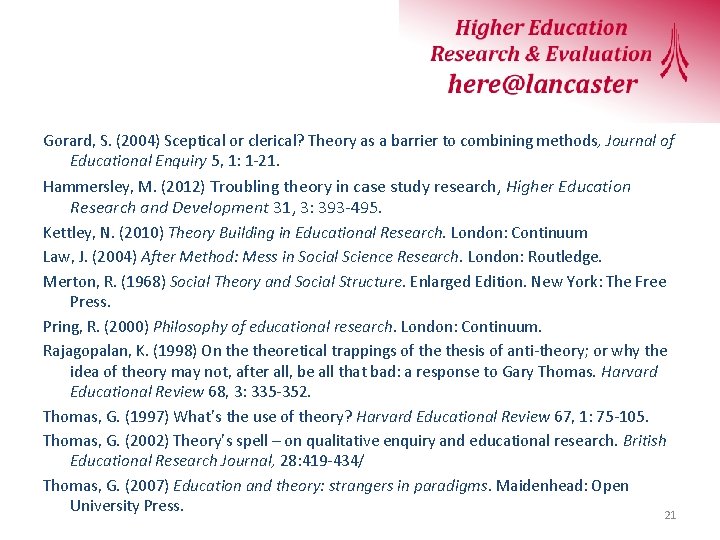

Gorard, S. (2004) Sceptical or clerical? Theory as a barrier to combining methods, Journal of Educational Enquiry 5, 1: 1 -21. Hammersley, M. (2012) Troubling theory in case study research, Higher Education Research and Development 31, 3: 393 -495. Kettley, N. (2010) Theory Building in Educational Research. London: Continuum Law, J. (2004) After Method: Mess in Social Science Research. London: Routledge. Merton, R. (1968) Social Theory and Social Structure. Enlarged Edition. New York: The Free Press. Pring, R. (2000) Philosophy of educational research. London: Continuum. Rajagopalan, K. (1998) On theoretical trappings of thesis of anti-theory; or why the idea of theory may not, after all, be all that bad: a response to Gary Thomas. Harvard Educational Review 68, 3: 335 -352. Thomas, G. (1997) What’s the use of theory? Harvard Educational Review 67, 1: 75 -105. Thomas, G. (2002) Theory’s spell – on qualitative enquiry and educational research. British Educational Research Journal, 28: 419 -434/ Thomas, G. (2007) Education and theory: strangers in paradigms. Maidenhead: Open University Press. 21