Developing PG student writing the novice researcher enters

- Slides: 63

Developing PG student writing

“ …the novice researcher enters what we call occupied territory – with all the immanent danger that this metaphor implies – including possible ambushes, barbed wire fences, and unknown academics who patrol the boundaries of the already occupied territories” (Kamler and Thomson, 2006: 29).

“The novice researcher is not only alien in foreign fields, but is unaware of the rules of engagement, and the histories of the debates, feuds, alliances and accommodations that precede her entry into the field” (Kamler and Thomson, 2006: 29).

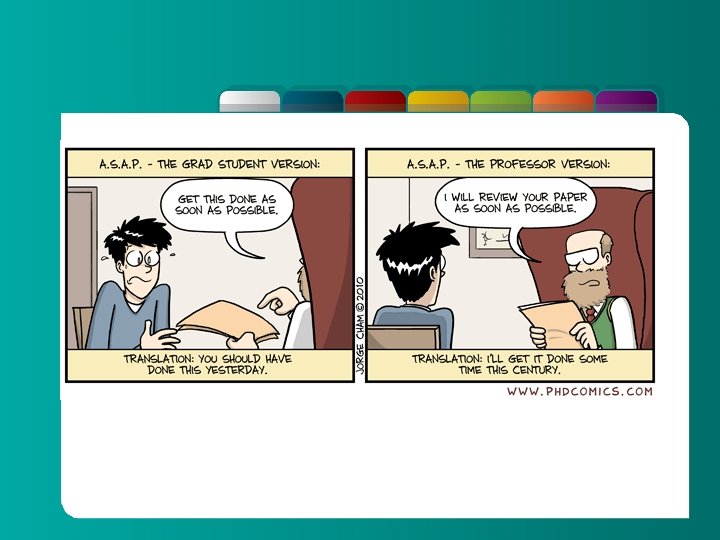

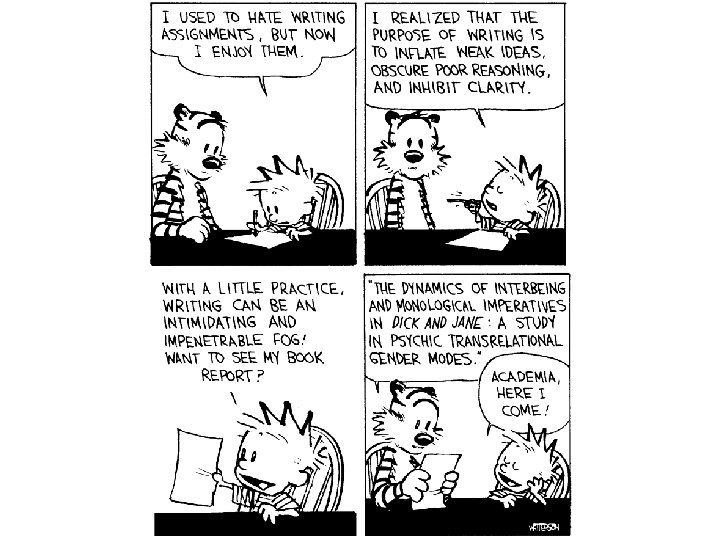

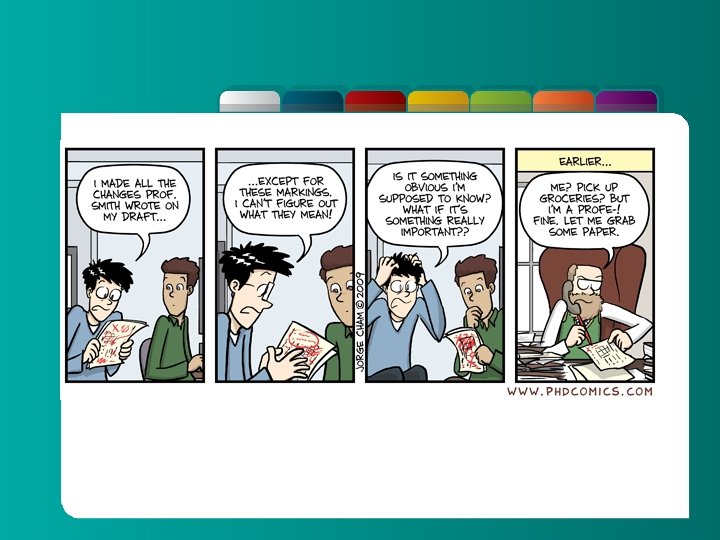

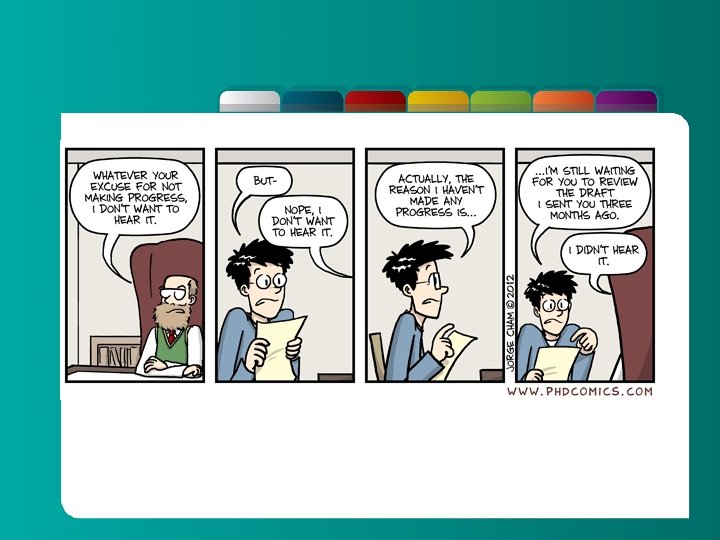

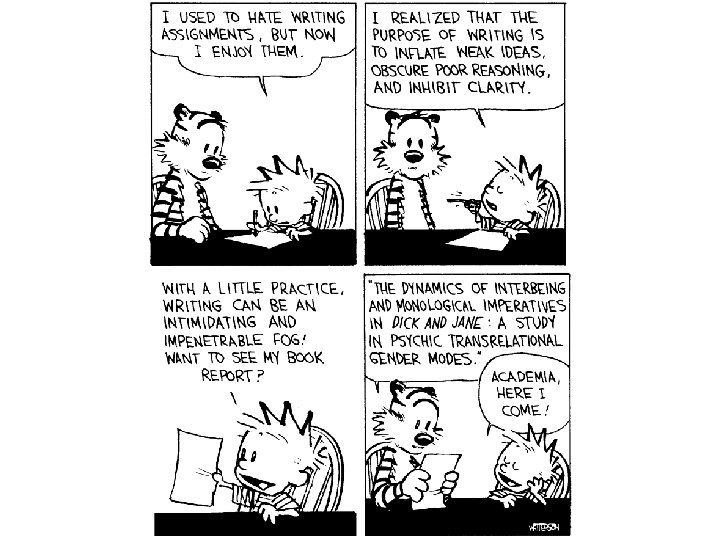

What can we learn from this cartoon? • Academic writing should aspire to simplicity and coherence When something can be read without effort, great effort has gone into its writing ~ Poncela • Writing is a practice – it is something acquired and developed. It is not a skill that is inherent. • Where and how do you develop student writing? If we fail to set aside time for getting the work of writing done, then we send the message that we don’t value the work ~ Badenhorst

Supervising the writing process Assumptions: • The thesis is a particular genre, with specific norms, emerging from the values of the discipline. Each aspect, from the way the chapters are structured, to the ways that prior research is referenced, to the levels of language formality, arises from a long history of knowledge construction in the discipline. • New writers have an important role to challenge such traditions, but they also have a right to be supported in accessing these powerful traditions. • As long at the PG qualification is assessed through a written thesis, assisting with discipline-specific writing development is a key aspect of supervision. • Many supervisors feel ill-equipped to develop students’ disciplinary writing. Do you agree with these assumptions?

The nature of PG writing • PG writing is contextualised within a university, a discipline and a broader social context: it is not a set of isolated skills • Writing is not transparent - connected to disciplinary values and attitudes • Writing creates a particular version of reality – it is about choices about what is written

Writing as social practice In broad terms, what this entails is that student academic writing, like all other writing, is a social act. That is, student writing takes place within a particular institution, which has particular history, culture, values, practices. It involves a shift away from thinking of language or writing skills as individual possession, towards the notion of an individual engaged in socially situated action; from an individual student having writing skills, to a student doing writing in specific contexts (Lillis, 2001: 31).

Regular, habitual approach to writing • A work in progress quickly becomes feral if it is left alone for too long. It reverts to a wild state … as the work grows it becomes harder to control; it is a lion growing in strength. You must visit it every day and reassert your mastery over it. If you skip a day or two, you are quite rightly afraid to open the door to its room. ~ Dillard 1989

Writing as a process • Most students think that all writing is about crafting and proofing the final product. They are unaware of the stages involved. Current advice on writing does not, we believe, give sufficient weight to the initial stages of writing which focus on the generation of ideas. ~ Grainger, Gouch and Lambirth 2005

Common sense about writing abounds… • Writing is about spelling, grammar and punctuation. • Writing is a second language problem. • If you can speak you should be able to write. Research disputes all these claims…

Are these problems familiar? • “Recent graduates seem to have no mastery of the language at all. They cannot construct a simple declarative sentence, either orally or in writing. They cannot spell common, everyday words. Punctuation is apparently no longer taught. Grammar is a complete mystery to almost all recent graduates. ” J. Mersand, Attitudes toward English Teaching, 1961 • “Practically everyone…in the old days spoke correctly. But the lapse of time has certainly had a deteriorating effect in this respect. ” Cicero 1 BC When was this said?

What does the research on academic writing tell us? • Are reading and writing two separate processes? Why / why not? • The most important findings are that you don’t learn and then write the learning. – You learn by writing. • The writing is the learning.

An academic reader expects: • An authoritative text (Clear voice and argument) • Mastery of the field/territory • The argument is built from knowledge claims that are appropriate to the discipline, each of which is substantiated by evidence appropriate to the discipline. • How can students meet these expectations in their writing?

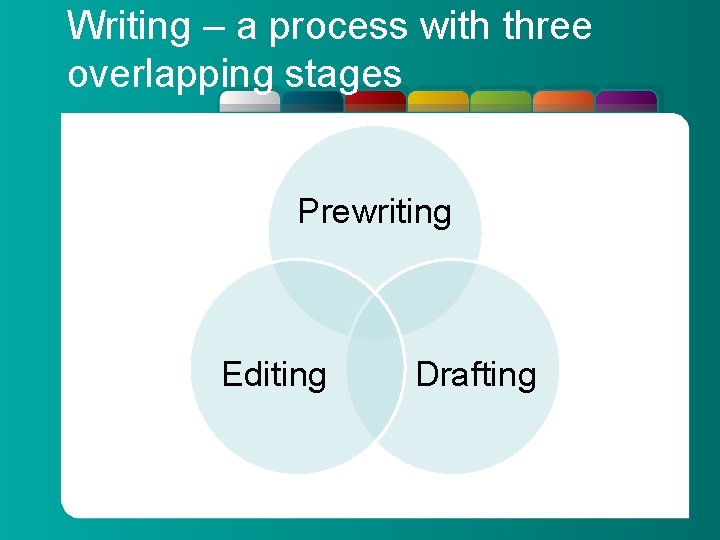

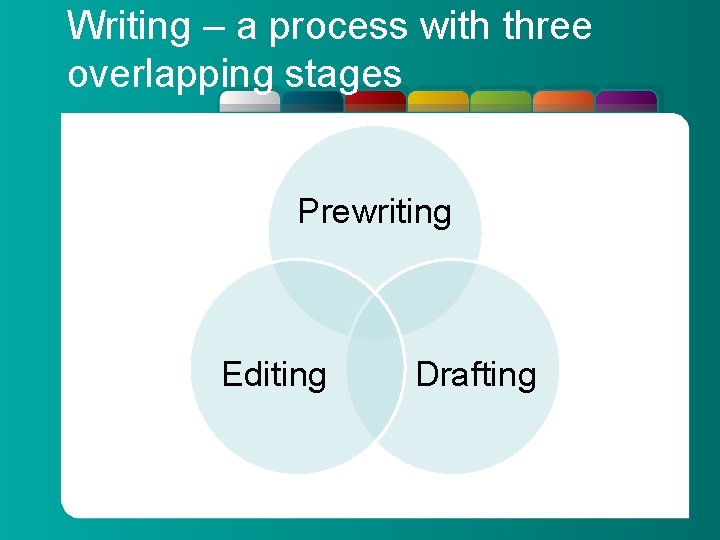

Writing – a process with three overlapping stages Prewriting Editing Drafting

What do successful writers do? 1. They write for themselves first (pre-writing) 2. They move into writing for others only once they have more or less established what they want to say (drafting). 3. When they move to drafting, they have an imaginary conversation with potential readers. 4. They edit at the end of the process (editing).

Pre-writing • Creative space for making meaning. • Personal space where the only reader will be the writer of the text. • Space through which to ensure ‘ownership’ of theory, to develop own writing ‘voice’, to creatively engage with the various issues, concepts and theories. • Four possible pre-writing tasks will now be introduced. – – Freewriting Research journal Reading journal Mind mapping

1

Freewriting – Approach 1 • Set a question or topic for yourself and write it at the top of the page • Set a short time limit (typically 3, 5 or 7 minutes) • Write without stopping. If you get stuck keep writing the same word until further thoughts flow. • Do not pause, look back or worry about neatness, spelling or grammar. Nobody else will read this. • When the time is up, stop. • Read what has emerged.

Benefits of Freewriting … • Focuses thinking • Captures thoughts and allows this to be revisited and interrogated at a later stage of the writing process • Helps writers to identify what they know and don’t know • Doesn’t take much time

Freewriting task • You will now undertake a freewriting task for yourselves. • Set a question or topic at the top of the page – choose something you are working on at the moment and be as specific as possible. (For example: A key concept in my study is X. X can be explained as…) • Write for 3 minutes without pausing when the facilitator tells you to do so. • When the facilitator tells you to, stop writing; turn to the person next to you and discuss what you learnt from this experience.

2 l a n r u o J h c r a e s e R

A diary of the research journey • Dear Diary, – – – What I did today, what I need to do tomorrow… What did I learn, what is puzzling me? What do I need to ask my supervisor? What readings do I need to seek out? Etc. etc.

3 g in ad Re l na ur Jo

Many students when they read… • • Underline key words Copy out key quotes Make notes in margins Write summaries • But this doesn’t help develop higher level understanding of the concepts or the ability to apply such concepts to the students’ own work…

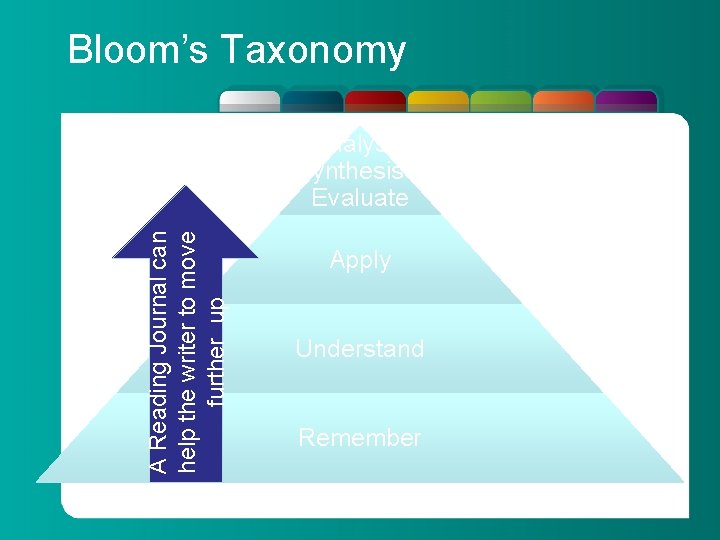

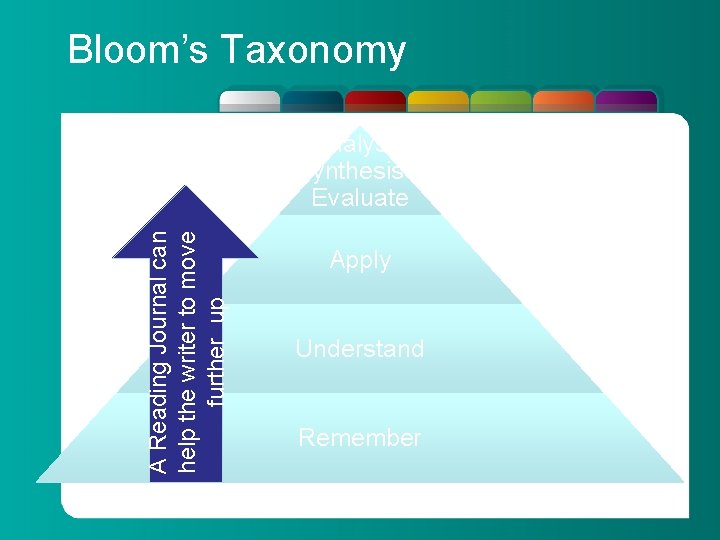

Bloom’s Taxonomy A Reading Journal can help the writer to move further up Analyse/ Synthesise/ Evaluate Apply Understand Remember

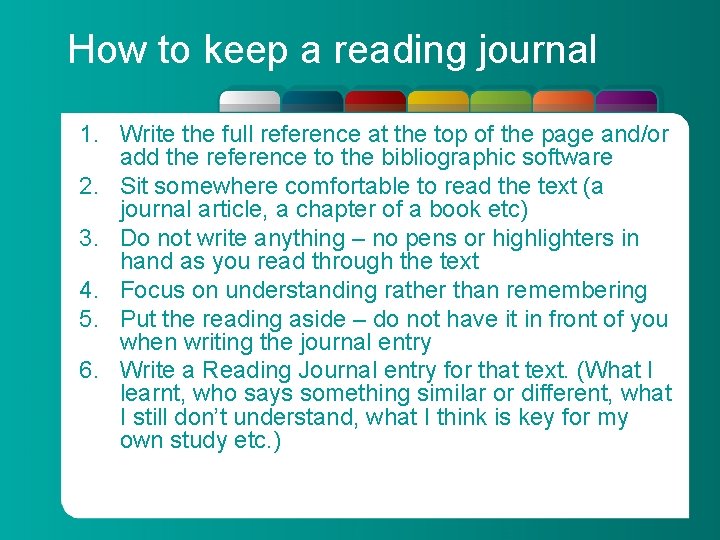

How to keep a reading journal 1. Write the full reference at the top of the page and/or add the reference to the bibliographic software 2. Sit somewhere comfortable to read the text (a journal article, a chapter of a book etc) 3. Do not write anything – no pens or highlighters in hand as you read through the text 4. Focus on understanding rather than remembering 5. Put the reading aside – do not have it in front of you when writing the journal entry 6. Write a Reading Journal entry for that text. (What I learnt, who says something similar or different, what I still don’t understand, what I think is key for my own study etc. )

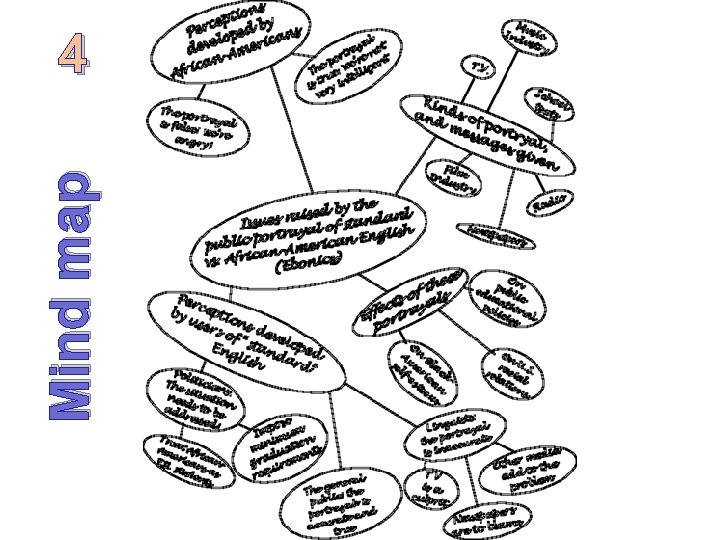

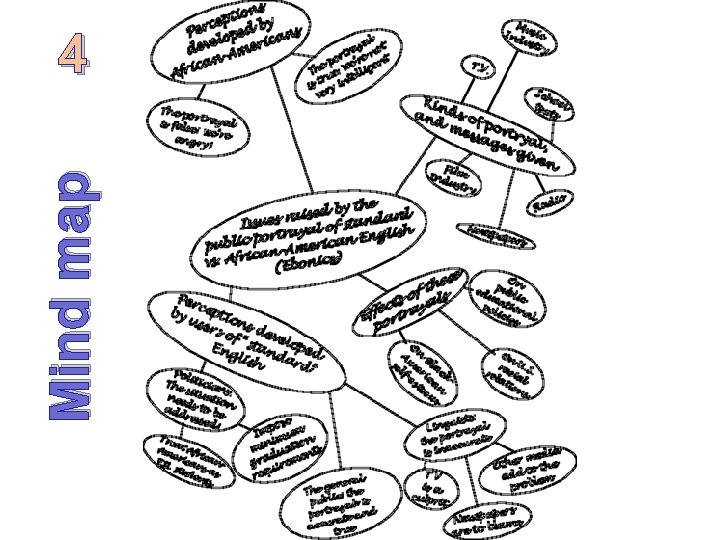

Mind map 4

Mind maps – show the connections • Allows writer to plot out how different points connect • Allows writer to consider the flow of the writing – what issue will I need to raise first, what theories do I need to explain when etc. • Helps to explain relationships between thoughts and concepts

Recapping There are other approaches to pre-writing beyond the 4 introduced here. Pre-writing approaches have the following in common: • They are for the writer only. No other reader. • The writer doesn’t concern his or herself with spelling or grammar; s/he uses the space to develop her meaning making. • The relationship between reading and writing is very strong.

Drafting and Re-drafting

Drafting • The second stage of the writing process is drafting. • Moves focus to coherence and flow in the writing. • Focus on the ‘golden thread’ or central purpose of the text as a whole • Clear understanding of how the particular section being drafted is attached to that ‘golden thread’. • The author now needs to start to consider the potential reader.

Drafting At the drafting stage, students need to ask: • Is there another way to understand or approach this problem/ question/ issue? • What are the objections to this approach? • If an alternative exists, acknowledge it and explain its shortcomings. • Do not belittle the alternative.

Knowledge claims and evidence • Any piece of academic writing consists of a series of knowledge claims (statements about what you believe to be the truth) • Each claim has to be supported by evidence. • The evidence comes from the work of others (the literature) • Or the evidence can come from the research itself • Examine all your claims for weakness and either substantiate them more strongly or limit the claim

Drafting and Re-drafting • This often entails major changes. • Students need to understand that they will do this again and again – both before and after feedback from supervisor. • Best done in a ‘chunk’ of time – 2 or 3 hours – to ensure flow and coherence. • This is not the same as editing / proofreading. • The writer needs to have the potential reader foremost in their mind. Who is the reader your students are writing for at this stage?

Drafting task Consider doing a drafting task with a few Ph. D scholars together. Get students to read through their draft text and ask themselves the following: • Is your work organised around the claim and evidence structure? • Are you using specialised vocabulary correctly? • Are your sentences too long? (The best way to find out is to read the text aloud. ) • Are your references correct and consistent?

“The beautiful thing about writing is that you don’t have to get it right the first time, unlike, say, brain surgery. You can always do it better” ~ Cormier.

Editing / Proofreading

Proofreading • Judgments are made as to the quality of students’ work and even their intelligence based on the surface level correction of their work • Spelling, grammar and punctuation do not tell us about either research quality or intelligence but we still get judged on this. So students need to get this right! • BUT students can only attend to this after they have made meaning for themselves (pre-writing) and developed a coherent text (drafting).

Proofreading • Don’t focus on surface issues too early, • Students need to be sure of what they want to say before they can get the surface level correct. • Giving detailed feedback or correction on surface level issues might hamper students from progressing. • This is NOT to say that surface level language issues, correct referencing and formatting are unimportant; it is simply that these are the last stage of writing.

Using a professional proofreader • Does your department encourage the use of a proofreader? • If so, when is the appropriate time to use a proofreader? • What should a proofreader do? What should a proofreader not do?

Conclusion So… learning to write: • is achieved over time • is achieved through writing • is achieved through getting constructive feedback The ability to write a coherent text is linked to: • an individual’s mastery of what s/he wants to say (lots of pre-writing), • His or her familiarity with the disciplinary discourse and norms (lots of reading and feedback)

Theme 4 Giving Feedback on Student Writing

Feedback • What was the most useful and least useful feedback you received as a student? • What are your major difficulties with giving feedback? Some of the content in this presentation comes from “A Brief Guide to Responding to Students’ Writing” (Rhodes University 2009), which can be found on the online space.

Feedback as crucial part of supervision • Providing feedback on students’ writing (verbally and in writing) is part of developing students as novice members of the discipline • It helps in the acquisition of the knowledge construction processes. • We need to be accessible as supervisors in order for students to seek feedback.

What, when and how of feedback • • What makes for good feedback? What kind of feedback is unhelpful? What kind of feedback do you give? Do you give feedback orally or in writing? In the text or at the end? What do you focus on? What is your intention when you give feedback on students’ writing? • How long should students wait to get feedback on their writing?

• Research has shown that students pay far more attention to comments on written work that is in progress than to comments on a final draft (Flower 1979; Paxton 1994).

Being a respondent, rather than an assessor The role of the respondent as opposed to the traditional teacher/assessor is to: • coach or guide rather than instruct, • respond rather than mark, and • provide formative assessment (to encourage learning).

• Comments to make explicit to students how to construct knowledge and what counts as knowledge in specific disciplines • Make the discourse conventions of thesis made more explicit • Students may be able to express their knowledge in more appropriate ways • Encourages students to view writing as a process rather than just a product.

Focus on meaning, not correction • Comments can assist students to reformulate ideas and focus on the meanings expressed in the writing. • Research shows that – it is essential for writers first to concentrate on revision and when they feel they have expressed their understandings clearly, etc. only then should they concentrate on editing their writing. • The respondent’s task to develop, help and support students – to clarify their understanding of concepts, – to learn how knowledge is constructed and – to express it as clearly and coherently

Asking questions in the body of text • The idea is to give the writer a sense of taking part in a dialogue with the reader; • Negotiating meaning with the reader and also to • Direct the writer to problem areas in his/her writing without telling him/her what to do but encouraging him/her to formulate ideas for him/herself. • The questioning format is generally more tentative and allows students to disagree with the respondent and retain ownership of their writing.

Providing explicit and direct comments • Explicit and direct comments help the student know exactly what is required. • Comments should, where possible, provide writers with clear and specific suggestions for revising text.

Comments in the text • It is important that comments appear in the body of the text. • Successful comments are both local (i. e. target a specific statement, passage or point in the text) as well as global (i. e. those that give overviews of the text and that give cohesion to local comments).

Prioritise issues in a piece of writing. • Students can seldom benefit from criticism of more than two or three problems. • As a general rule focus first on the meaning which the writer is trying to express.

Constructive, not destructive, comments • Consider how the student will read the feedback. • Provide detailed positive feedback where possible. Students don’t always know what they have done right. • Descriptive, observational feedback will help the student to identify what they are doing right and repeat this.

Respond to the person • Use the student’s name in your comments. • Be specific and detailed. Comments such as “This makes no sense” or “What does this mean? ” are not helpful. • Avoid taking over student’s writing - use ‘comments’ rather than simply correcting text. • Use ‘Track changes’ to monitor the extent to which you’re doing the writing for the student.

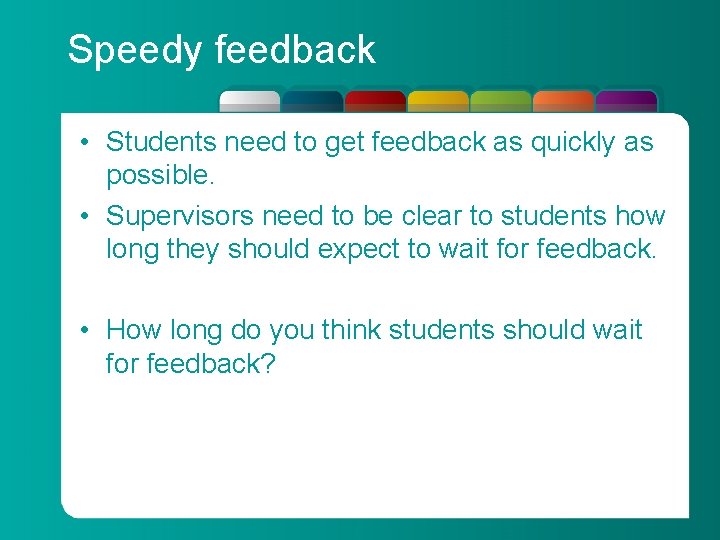

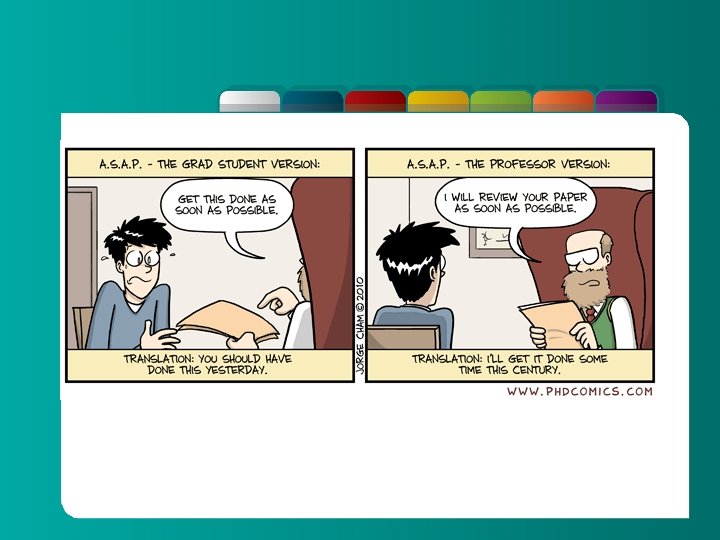

Speedy feedback • Students need to get feedback as quickly as possible. • Supervisors need to be clear to students how long they should expect to wait for feedback. • How long do you think students should wait for feedback?