Developing algebraic thinking in primary school an italian

Developing algebraic thinking in primary school: an italian adaptation of Davydov’s approach *Maria Mellone, *Roberto Tortora, **Colomba Punzo *University Federico II of Naples, (Italy); **70° Circolo Didattico of Naples, (Italy)

The algebraic skills of young children The evidence that very young children have some rough algebraic thinking forms seems to be increasingly spreading (e. g. Radford, 2010, 2011). … no educational strategy should be planned without giving care to this early skills, the goals of education to mathematical thinking should include the need to refine these early forms of competence, acknowledging and appreciating their natural character and driving their development towards culturally stable forms.

Some research about algebraic thinking in very young children • • • Carraher et al. , 2001; Radford, 2001; Dougherty & Slovin, 2004; Malara & Navarra, 2008; Caspi & Sfard, 2010. It is possible that these days algebra is simply “in the air”: elements of algebraic discourse may be present in other school discourse well before its formal introduction in 7 th grade. With help from the media, algebraic forms of expression may even be infiltrating colloquial discourses. (p. 256) A complex relationship has been proposed between arithmetic and algebraic thinking (Radford, 2010) How to favour the development of these embodied, non symbolic forms of algebraic thinking? What kind of early work leads to the development of algebraic thinking toward a conscious use of formal algebraic language?

Algebraic thinking - The awareness of, or attention to, structure. Learners exhibit this kind of attention when they begin to focus on what stays and what changes – that is, “become accustomed to considering invariance in the midst of change” (Mason et al. , 2009, p. 13) - A vision of thinking as interpersonal and intrapersonal communication (Sfard, 2008) - Thinking is made tangible by social practice and materialized in the body, in the use of signs and artefacts: “we argue that thinking is made up of material and ideational components—such as (inner and outer) speech, forms of sensuous imagination, gestures, tactility, and actual actions with signs and cultural artifacts” (Radford, 2010)

Algebraic thinking can be seen as a kind of (inter/intrapersonal) “discourse” in which we can recognize this attention to structure.

An Italian adaptation of Davydov’s approach “Course on re-discovery of arithmetical and algebraic sense, by working with quantities”

Method - Design based research (Cobb et al. , 2003) ; - One year of experimentation in a fifth grade class; - That class had completed a relatively traditional mathematics curriculum up to that time; “Algebraic thinking does not appear in ontogeny by chance, nor does it appear as necessary consequence of cognitive maturation. To make algebraic thinking appear, and to make it accessible to the students, some pedagogical conditions need to be created” (Radford, 2011, p. 308 -309) - We proposed several activities, in particular those that Davydov imagined for first grade classes.

Design - Observation, description and representation (natural language, graphical representation and symbol) of simple equalities and inequalities among continuous physical quantities (Davydov, 1982). - Collective discussion about the build and the use of “graphical qualitative representation” (this represents a point of innovation compared to the courses proposed by Davydov, where the graphical representations are given by the teacher). - Identification and recognition of structures in diverse problematic situations, and their use for the solution of equations. This phase is meant both as an integral part of the development of algebraic thought, and as a moment of evaluation, allowing us to trace the effects of the prior course in the children’s reasoning.

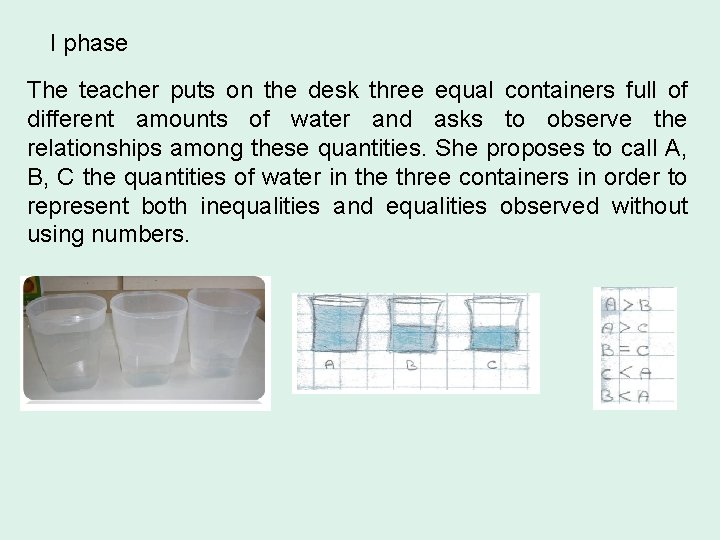

I phase The teacher puts on the desk three equal containers full of different amounts of water and asks to observe the relationships among these quantities. She proposes to call A, B, C the quantities of water in the three containers in order to represent both inequalities and equalities observed without using numbers.

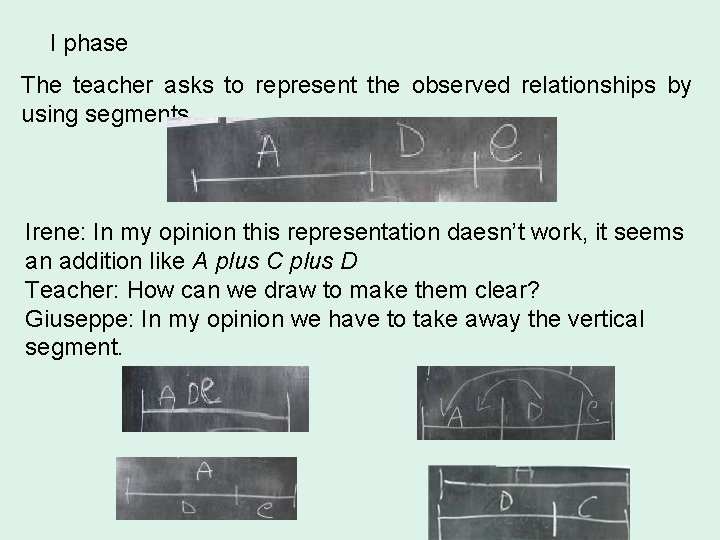

I phase The teacher asks to represent the observed relationships by using segments. Irene: In my opinion this representation daesn’t work, it seems an addition like A plus C plus D Teacher: How can we draw to make them clear? Giuseppe: In my opinion we have to take away the vertical segment.

II phase The teacher propose to play thinking how to obtain equalities by adding or taking way these quantities and invites the children to write these equalities using letters. The work carries on thanks to the synergy of natural language, drawings and algebraic language.

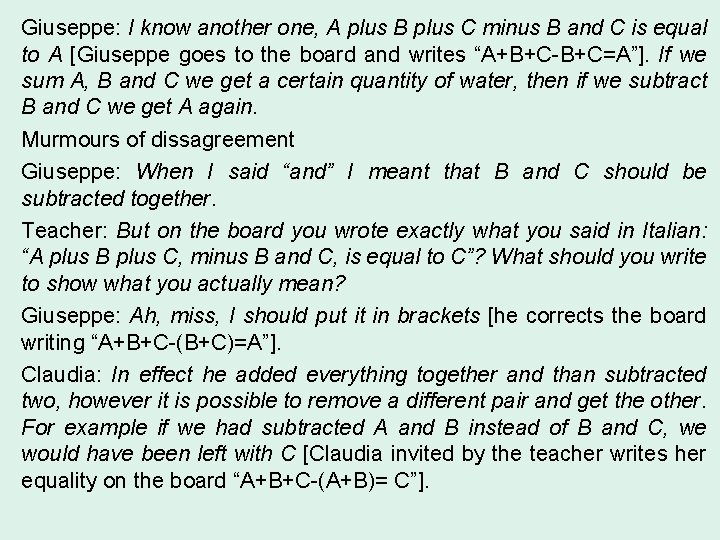

Giuseppe: I know another one, A plus B plus C minus B and C is equal to A [Giuseppe goes to the board and writes “A+B+C-B+C=A”]. If we sum A, B and C we get a certain quantity of water, then if we subtract B and C we get A again. Murmours of dissagreement Giuseppe: When I said “and” I meant that B and C should be subtracted together. Teacher: But on the board you wrote exactly what you said in Italian: “A plus B plus C, minus B and C, is equal to C”? What should you write to show what you actually mean? Giuseppe: Ah, miss, I should put it in brackets [he corrects the board writing “A+B+C-(B+C)=A”]. Claudia: In effect he added everything together and than subtracted two, however it is possible to remove a different pair and get the other. For example if we had subtracted A and B instead of B and C, we would have been left with C [Claudia invited by the teacher writes her equality on the board “A+B+C-(A+B)= C”].

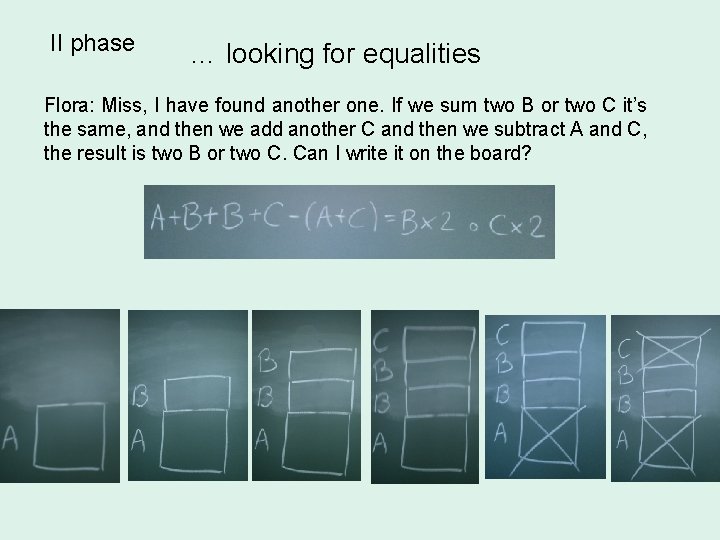

II phase … looking for equalities Flora: Miss, I have found another one. If we sum two B or two C it’s the same, and then we add another C and then we subtract A and C, the result is two B or two C. Can I write it on the board?

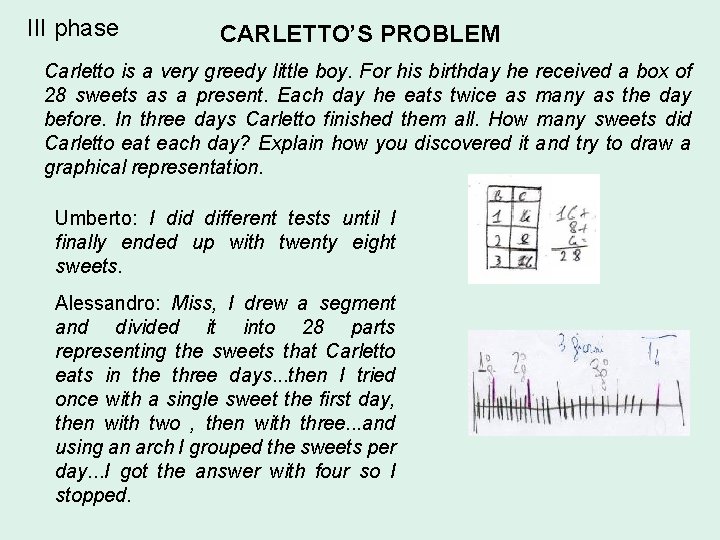

III phase CARLETTO’S PROBLEM Carletto is a very greedy little boy. For his birthday he 28 sweets as a present. Each day he eats twice as before. In three days Carletto finished them all. How Carletto eat each day? Explain how you discovered it graphical representation. Umberto: I did different tests until I finally ended up with twenty eight sweets. Alessandro: Miss, I drew a segment and divided it into 28 parts representing the sweets that Carletto eats in the three days. . . then I tried once with a single sweet the first day, then with two , then with three. . . and using an arch I grouped the sweets per day. . . I got the answer with four so I stopped. received a box of many as the day many sweets did and try to draw a

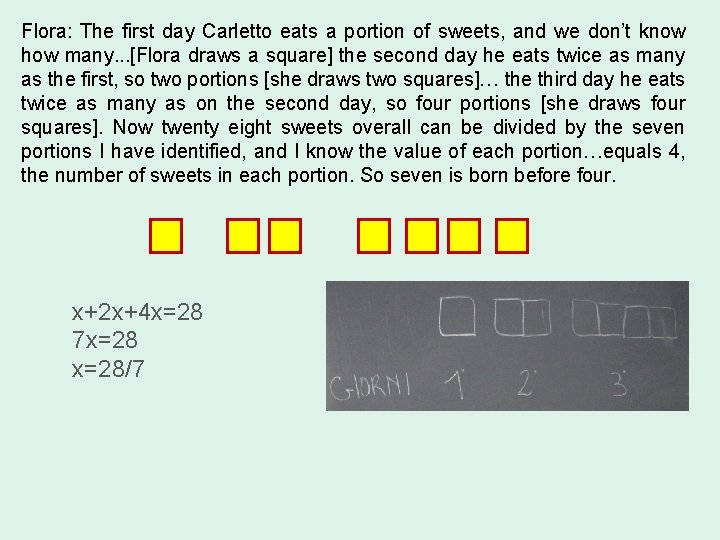

Flora: The first day Carletto eats a portion of sweets, and we don’t know how many. . . [Flora draws a square] the second day he eats twice as many as the first, so two portions [she draws two squares]… the third day he eats twice as many as on the second day, so four portions [she draws four squares]. Now twenty eight sweets overall can be divided by the seven portions I have identified, and I know the value of each portion…equals 4, the number of sweets in each portion. So seven is born before four. x+2 x+4 x=28 7 x=28/7

Some conclusive reflections - There could be a recognition of the algebraic structure independent from arithmetic (like in Davydov’s prospective), but there could be a recognition of the algebraic structure as formal meta-arithmetic (like in the more traditional western approach). In this sense we think that Davydov’s approach can be used in different school grades. - In our experience, the use of Davydov’s approach in an Italian fifth grade was lived as opportunity to re-discover structural relationships already met by pupils, but not really internalized. In this process was crucial the synergistic use of different tools: natural language, graphical representations and algebraic language.

Thank you!

- Slides: 17