Detlef Briesen JustusLiebigUniversitt Gieen HOW TO WRITE A

Detlef Briesen, Justus-Liebig-Universität, Gießen HOW TO WRITE A LITERATURE REVIEW

DEFINITION OF �A literature review is a summary and an analysis of what has been published in a specific field of research or on a topic in a respective scientific community. � For several issues researchers are asked to write reviews of literature, either as a separate chapter for a thesis or a volume, or more commonly as part of the introduction to an application, an essay, or a report.

IMPORTANCE As a piece of writing, a literature review is by far more than just a descriptive list of books and articles. � It is one of the most important parts of any scientific publication as it indicates the standard of knowledge about the topic, and the creativity of the respective scientific approach. � As such the review of literature is intensively influencing the success of applications and publications. � The seminar introduces into concepts and strategies to compose reviews of literature successfully. �

AIMS The aim of a literature review is � to demonstrate knowledge about the already published books, articles etc. as well as in printed as in electronic form, � to give the quintessence of existing literature, � to outline traditions and theoretical concepts of research including methods, � to discuss strengths and weaknesses of existing research, � to identify research gaps, and desiderata, � to develop ideas and hypothesis to guide research. �

STEP BY STEP

TOPICS

1. PICK A TOPIC � It can be as broad as you like, because this is just a starting point. � If you are still picking your specific topic for your Ph. D, that’s fine, but you should at least know roughly what area you want to explore.

WHERE TO BEGIN?

2. FIND YOUR WAY IN � � � A quick google scholar search for your subject area could turn up as many as 1 million results. Clearly you can’t read them all, so you need to look for an easy way in. The vast majority of academic papers are written for people already familiar with the subject. They will refer to theories and methodologies assuming that the reader knows what they are. So to start with just any paper at random would be a demoralizing waste of time, as you’ll be overwhelmed by the jargon. Instead, you need something you can understand easily to give yourself a foundation of knowledge to build upon. Textbooks and review articles can be good places to start, though even these can be highly technical. If you can’t find one you can understand easily, then look for a book written for the general, non-academic public. The idea is to gain a quick, broad background knowledge before getting into more specialized technical detail.

3. HISTORY, PEOPLE & IDEAS � � � The idea of a literature review is to give some background and context to your own work. You need to show your research fits into the big picture, relating it to what has been done before. You don’t need to write a comprehensive history of your subject, but it helps if you know roughly how it has developed over time. So as you read a few general introductions to your topic, you’ll start to get an overview of the key ideas and theories, who developed them, and when. Also note any conflicting ideas, any controversy or disagreement in the field, as you’ll need to know this kind of thing. Now you can start to look for specific papers.

4. FIND THE WORLD-CHANGING LITERATURE � Once you know who the world changers were, you can go in search of their papers. � You need to make sure you understand these key concepts, as they will help you decipher other papers which built upon these ideas. � Sometimes, those world changing papers can be tough to read, but as long as you know roughly what they did and understand the key principle, that’s enough.

5. GET SPECIFIC � Only once you have a grasp of the key ideas in your field should you get more specific. � There may be several angles you can take in your research, and you may have to explore many areas of the literature. So divide your literature search into sections to make it easier to manage. For each section, think of several keywords to try out in different combinations.

6. FILTER � Even when you look at highly specialised subtopics, there may still be thousands upon thousands of papers, so you need to filter them. Here a few ways to reduce the numbers: � Look at the number of citations as an indication of quality � Make your keywords more specific � Don’t be afraid to reject papers. You can always come back to them later, but you have to start with something manageable.

7. FILTER AGAIN � You might not be able to read everything in depth immediately. From the papers you selected, give them a ranking A, B, or C. � A = must read, highly relevant, high quality � B = unsure, probably relevant, but not yet sure how � C = probably irrelevant, not what you thought it was when you read the title � If you’ve printed them , put the letter A, B, or C on the front so you can tell quickly when you come back to them (maybe months or years later)

� � � � � References Benda-Beckmann, Franz von (1992): Symbiosis of Indigenous and Western Law in Africa and Asia: An Essay on Legal Pluralism. In: Mommsen, Wolfgang J. /de Moor, J. A. (Hrsg. ): European Expansion and Law. The Encounter of European and Indigenous Law in 19 th- and 20 th-Century Africa and Asia. Oxford. 307 -325. Bell, Daniel A. /Chaibong, Hahm (2003): Confucianism for the Modern World. Cambridge. Bell, John (2008): Administrative Law. In: Bell, John (et al. ): Principles of French Law. Oxford. 168 -200. Betts, Raymond F. (1961): Assimilation and Association in French Colonial Theory 1890 -1914. New York. Brötel, Dieter (1971). Französischer Imperialismus in Vietnam. Die koloniale Expansion und die Errichtung des Protektorates Annam-Tongking. Zürich. Bureau International du Travail (Hrsg. ) (1937): Problème de travail en Indochine. Genf. Chanock, Martin (1992): The Law Market: The Legal Encounter in British East and Central Africa. In: Mommsen, Wolfgang J. /de Moor, J. A. (Hrsg. ): European Expansion and Law. The Encounter of European and Indigenous Law in 19 th- and 20 th-Century Africa and Asia. Oxford. 279305. Deloustal, M. R. (1908): La justice dans l’ancien Annam: Code des Lê. In: Bulletin de l’Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient 8, 177 -220. Deroche, Alexandre (2004): France coloniale et droit de propriété. Les concessions en Indochine. Paris. Doumer, Paul (1905): L’Indo-Chine française (Souvenirs). Paris Durand, Bernard (2015): Introduction historique au droit colonial. Un ordre au gré des vents. Paris. Eli, Barbara (1967): Paul Doumer in Indochina 1897 -1902. Heidelberg. Fourniau, Charles (2002): Vietnam. Domination coloniale et résistance nationale 1858 -1914. Paris. Gantès, G. de (1994): Coloniaux et gouverneurs en Indochine française 1902 -1914. Paris. Girault, Arthur (1922): Principes de colonisation et de législation coloniale. Les Colonies françaises depuis 1815 I. Paris. Girault, Arthur (1923): Principes de colonisation et de législation coloniale. Les Colonies françaises depuis 1815 II. Paris. Harmand, Jules (1885): Notes diverses sur quelquestions relatives à l’Indochine, Juin-Juil, Note III: Du protectorat et de l’administration directe. Ministère des Affaires Etrangères. Mémoires et Documents. Asie 24, 58, 1884 -1887. Holz, Harald/Wegmann, Konrad (Hrsg. ) (2005): Rechtsdenken: Schnittpunkte West und Ost. Recht in den gesellschafts- und staatstragenden Institutionen Europas und Chinas. Münster. Huard, Pierre/Durand, Maurice (1954): Connaissance du Vietnam. Paris.

8. USE OTHER PEOPLE’S BIBLIOGRAPHIES � Even if you can only find one good quality paper, read the introduction carefully and see who they cite. There may be a few gems there you didn’t find with the search engine. � Also see who else has cited that one paper since it was published (this is also a very quick way to update your bibliography if you are coming back to it a year or more later).

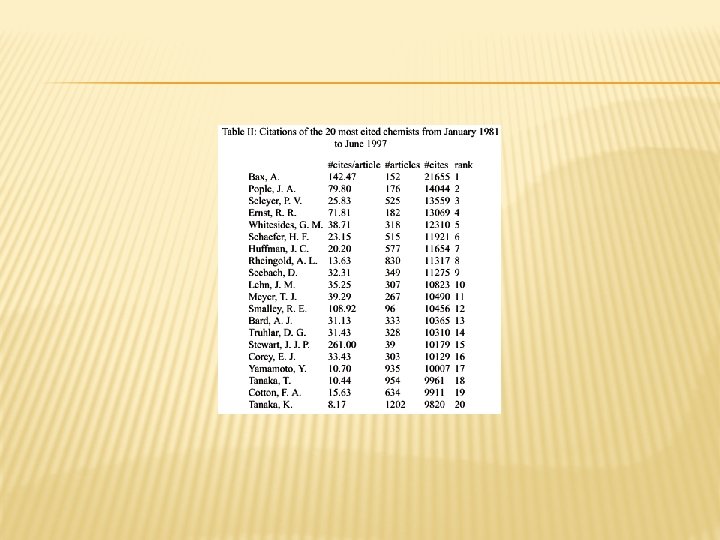

9. GET TO KNOW THE BIG PLAYERS � In any research field, no matter how specialised, there will be leading experts or competing research groups. Figure out who they are, and read their work.

10. MAKE SURE YOUR IDEAS ARE ORIGINAL � How can you prove that nobody else has done what you plan to do, without searching every paper ever published? � Well, it’s worth spending a day or two searching every keyword combination you can think of related to your specific research plan.

11. WRITE ABOUT IDEAS � When you finally start writing your literature review, focus on ideas and use examples from the literature to illustrate them. � Don’t just write about every paper you have found (I call this the telephone-directory approach), as it will be tedious to write and impossible to read. � The aim should always be to cite the best and most relevant research, rather than going for sheer quantity.

12. YOU AREN’T WRITING A TEXTBOOK � So you can leave out big chunks. Write about what is relevant to your research.

13. VARY THE DETAIL � When talking about a broad topic, only cite the very, very best papers. You’ll have a lot to choose from , so why choose anything but the best? � Then when you get into more specialised sections, you can include a larger number of less well-known papers (but still the highest quality you can find).

14. DON’T CITE ANYTHING � Don’t cite anything you haven’t read or don’t understand

15. GET EXPERIENCE � Your perspective on the literature will be quite different once you have done your own research. If you are in your first year, get your literature review done quickly so you can move on with your own work, and don’t let it hold you back. � It takes time to figure out what makes a good paper and what makes a bad one, and that comes with experience of carrying out research, talking to other researchers, and just reading more.

- Slides: 39