Designing IP EE 122 Intro to Communication Networks

- Slides: 48

Designing IP EE 122: Intro to Communication Networks Fall 2010 (MW 4 -5: 30 in 101 Barker) Scott Shenker TAs: Sameer Agarwal, Sara Alspaugh, Igor Ganichev, Prayag Narula http: //inst. eecs. berkeley. edu/~ee 122/ Materials with thanks to Jennifer Rexford, Ion Stoica, Vern Paxson and other colleagues at Princeton and UC Berkeley 1

Goals of Today’s Lecture Transitioning from high-level principles to low-level design • Review basic design decisions • Discuss the design of IP – The “what” and “why” of the IP header • Compare with IPv 6 2

Review of Basic Design Decisions 3

Five Basic Design Decisions (so far) 1. Packet-switching 2. Best-effort service model 3. Layering 4. A single internetworking layer 5. The end-to-end principle (and fate-sharing) 4

1. What is Packet Switching? • Divide messages into a sequence of packets • Network deals with each packet individually – What is an alternative to this? • Means that each packet must contain all relevant network information in its header – Design of protocol almost synonymous with header 5

Why Packet-Switching? • Achieve higher levels of utilization – Statistical multiplexing – Why is this more important for the Internet than for the phone network? • Avoid per-flow state inside the network – Plenty of routing state, but no per-flow state – Follows from notion of fate-sharing – Enables robust fail-over • Why not virtual circuits? – The notion of “soft-state” is midway between DG and 6 VC

2. What is “Best Effort”? • Network makes no service guarantees – Just gives its “best effort • Service can be imperfect – Packets may be lost – Packets may be corrupted – Packets may be delivered out of order – Packet may be significantly delayed source destination IP network 7

Why Best-Effort (BE)? • BE means never having to say you’re sorry… – No need to reserve bandwidth and memory – No need to do error detection & correction – No need to remember from one packet to next – No need to make packets follow same path • Easier to survive failures – Transient disruptions are okay during failover • Simplifies interconnection between networks – Minimal service promises 8

But What About Applications? • Some applications want more: – No losses or corruption, with packets delivered in order o They just want the data – Minimal and predictable delays o And they want it now! • Is Best Effort good enough for these applications? • Perhaps most important question Internet got right 9

Use Higher Layers to Compensate • No error detection or correction – Higher-level protocol can provide error checking • Successive packets may not follow the same path – Not a problem as long as packets reach the destination • Packets can be delivered out-of-order – Receiver can put packets back in order (if necessary) • Packets may be lost or arbitrarily delayed – Sender can send the packets again (if desired) – Receiver can buffer packets for smooth playout • No network congestion control (beyond “drop”) – Sender can slow down in response to loss or delay 10

What Can’t Higher Layers Do? • Higher layers cannot make delay smaller • If applications needs guarantee of low-delay, then need to ensure adequate bandwidth – Will keep queueing delay low – No way to help with speed-of-light latency • What applications need guaranteed low-delay? • Can the Internet support phone calls? 11

3. What is and Why Layering? • Modularity partitions functionality into modules • Laying is a particularly simple form of modularity • Modules only deal with layers above and below – Simplifies interactions between modules – Simplifies introduction of new protocols 12

4. Why one networking layer protocol? • Unifies the architecture • As long as applications can run over IP-based protocols, they can run on any network • As long as networks support IP, they can run any application 13

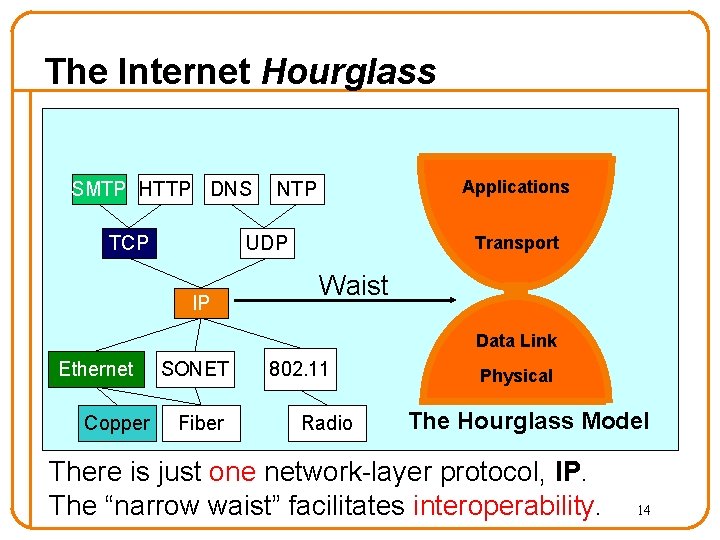

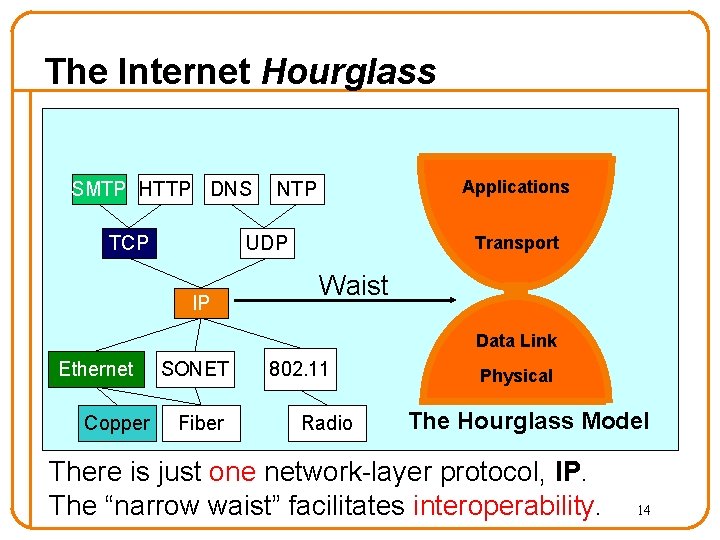

The Internet Hourglass SMTP HTTP DNS TCP Applications NTP UDP IP Transport Waist Data Link Ethernet Copper SONET Fiber 802. 11 Radio Physical The Hourglass Model There is just one network-layer protocol, IP. The “narrow waist” facilitates interoperability. 14

Alternatives to universal IP? • What would happen if we had more than one network layer protocol? • Are there disadvantages to having only one network layer protocol? – Some loss of flexibility, but the gain in interoperability more than makes up for this – Because IP is embedded in applications and in interdomain routing, it is very hard to change – Having IP be universal made this mistake easier to make, but it didn’t cause this problem 15

5. What is the End-to-End Principle? • E 2 E Principle guides placement of functionality – If hosts can implement functionality correctly, implement it in a lower layer only as a performance enhancement – But do so only if it does not impose burden on applications that do not require that functionality • Fate Sharing guides placement of state – Keep state on elements that rely on it, when possible 16

The Design of IP 17

Designing IP • What does it mean to “design” a protocol? • Answer: specify the syntax of its messages and their meaning (semantics). – Syntax = elements in packet header, their types & layout o representation – Semantics = interpretation of elements o information • What semantics do we need in the IP header? 18

What Info Should Header Provide? • Getting the packet there: – Where is packet going? – Which protocol will process packet on host? • Network handling of packet: – How should the packet be forwarded (e. g. , priority) – Where does header and packet end? • Dealing with problems: – Has header been corrupted? [Why not payload? ] – Has packet been fragmented? o If so, provide information needed to reconstruct – Is packet caught in a loop? o If so, drop packet 19

Header Info (continued) • Extensibility: (how can we let IP change? ) – Which IP version and options are expected? • Miscellaneous: – Where did packet come from? [Why is this needed? ] 20

From Semantics to Syntax • The past two slides discussed the kinds of information the header must provide • Will now show the syntax (layout) of the header, and discuss the semantics in more detail 21

5 Minute Break Questions Before We Proceed? 22

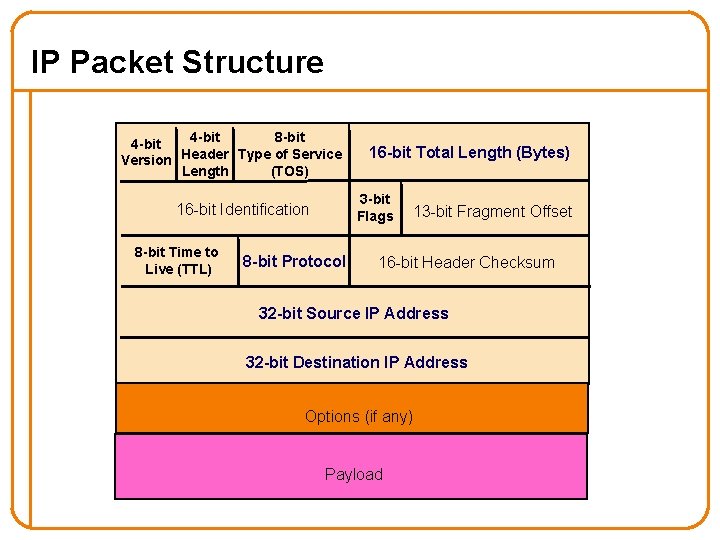

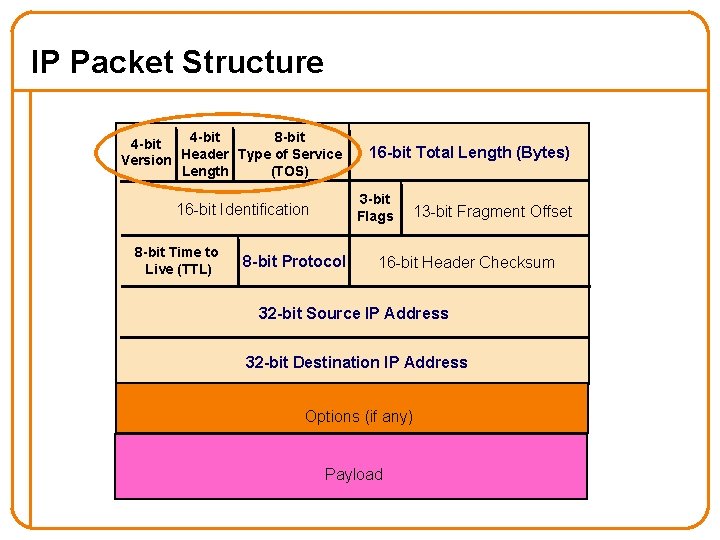

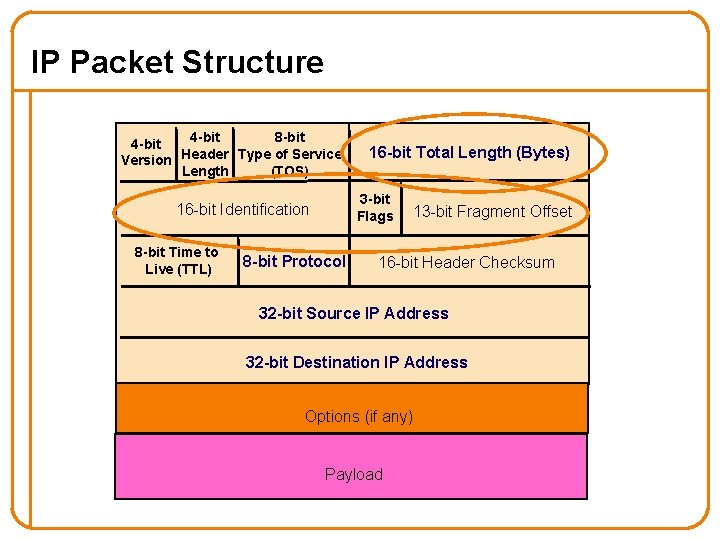

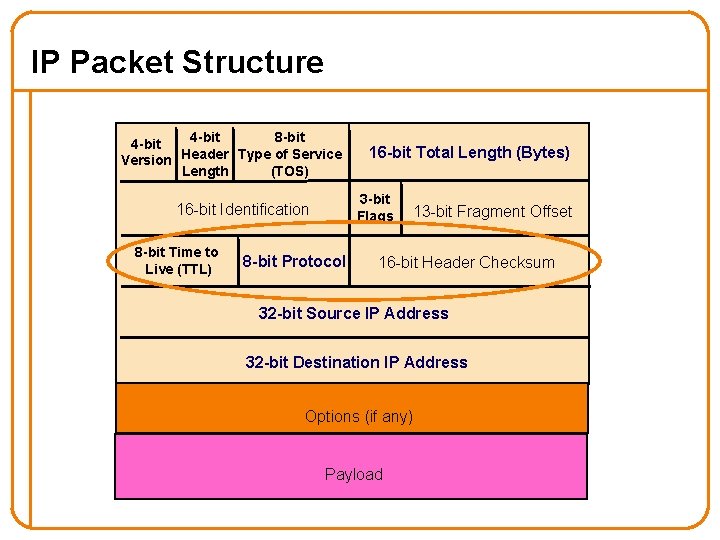

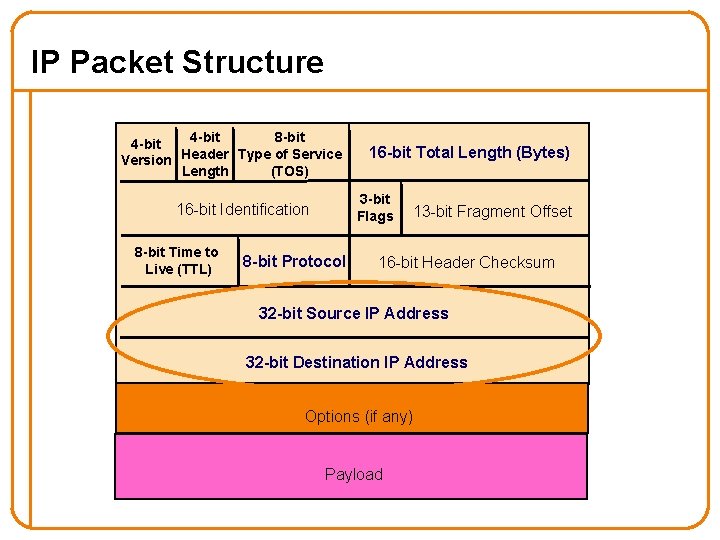

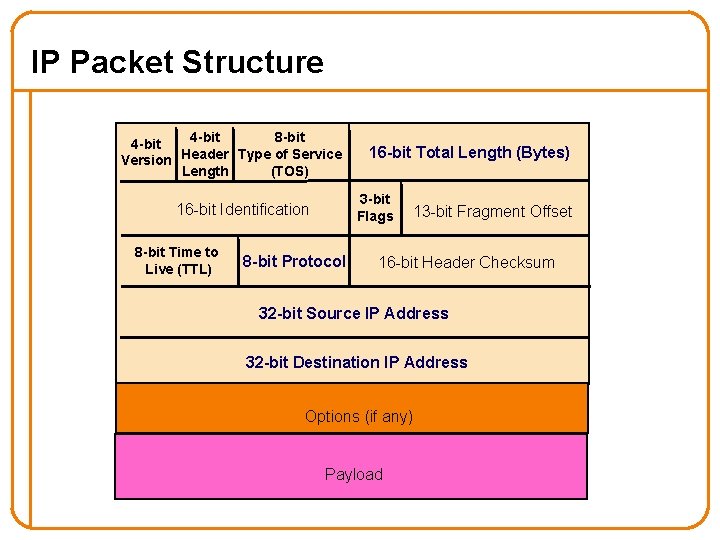

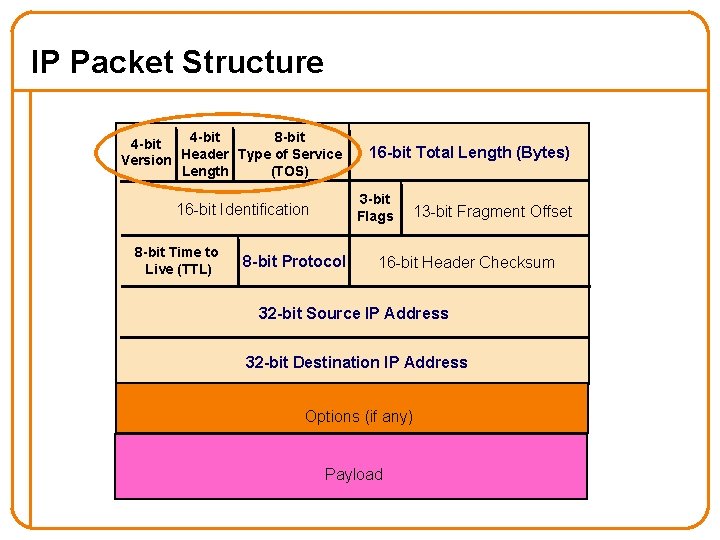

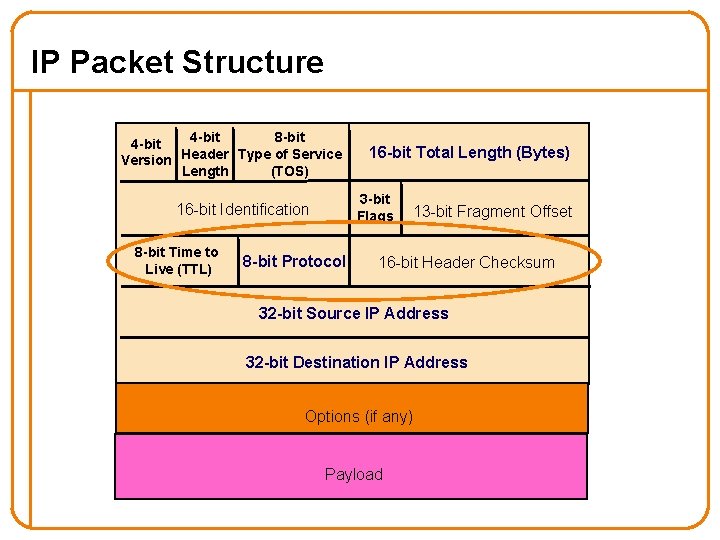

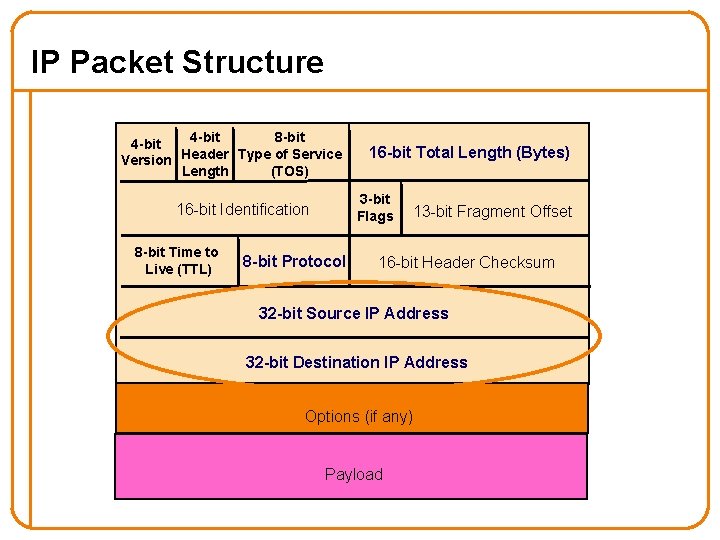

IP Packet Structure 4 -bit 8 -bit 4 -bit Version Header Type of Service Length (TOS) 3 -bit Flags 16 -bit Identification 8 -bit Time to Live (TTL) 16 -bit Total Length (Bytes) 8 -bit Protocol 13 -bit Fragment Offset 16 -bit Header Checksum 32 -bit Source IP Address 32 -bit Destination IP Address Options (if any) Payload

IP Packet Structure 4 -bit 8 -bit 4 -bit Version Header Type of Service Length (TOS) 3 -bit Flags 16 -bit Identification 8 -bit Time to Live (TTL) 16 -bit Total Length (Bytes) 8 -bit Protocol 13 -bit Fragment Offset 16 -bit Header Checksum 32 -bit Source IP Address 32 -bit Destination IP Address Options (if any) Payload

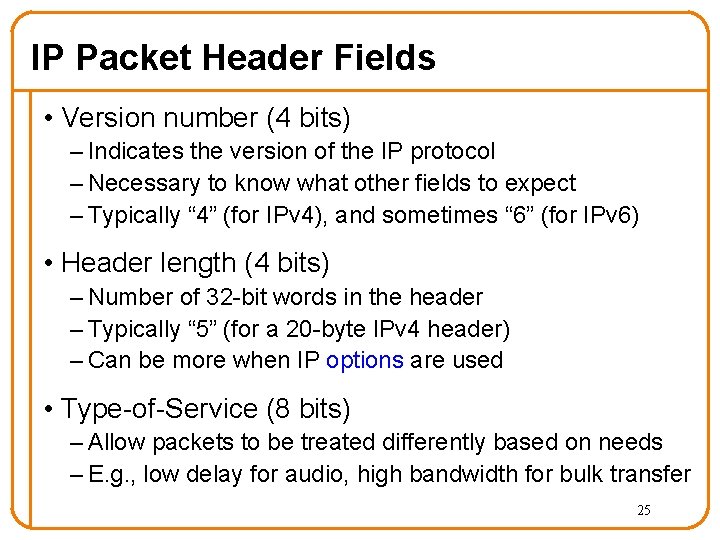

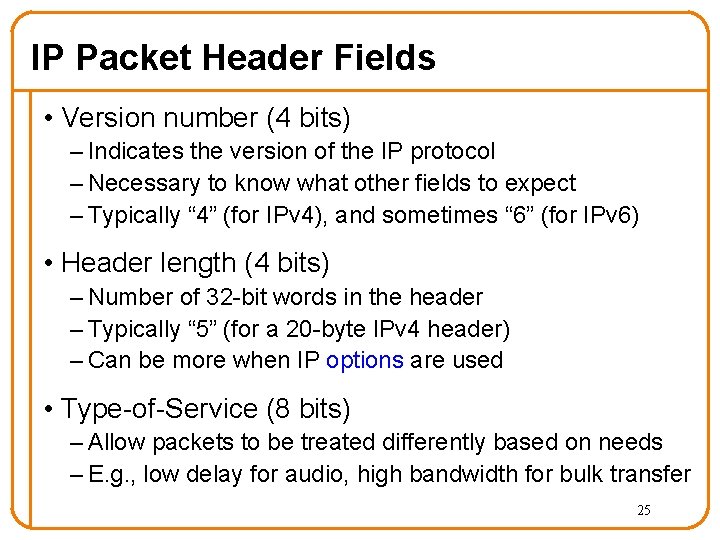

IP Packet Header Fields • Version number (4 bits) – Indicates the version of the IP protocol – Necessary to know what other fields to expect – Typically “ 4” (for IPv 4), and sometimes “ 6” (for IPv 6) • Header length (4 bits) – Number of 32 -bit words in the header – Typically “ 5” (for a 20 -byte IPv 4 header) – Can be more when IP options are used • Type-of-Service (8 bits) – Allow packets to be treated differently based on needs – E. g. , low delay for audio, high bandwidth for bulk transfer 25

IP Packet Structure 4 -bit 8 -bit 4 -bit Version Header Type of Service Length (TOS) 3 -bit Flags 16 -bit Identification 8 -bit Time to Live (TTL) 16 -bit Total Length (Bytes) 8 -bit Protocol 13 -bit Fragment Offset 16 -bit Header Checksum 32 -bit Source IP Address 32 -bit Destination IP Address Options (if any) Payload

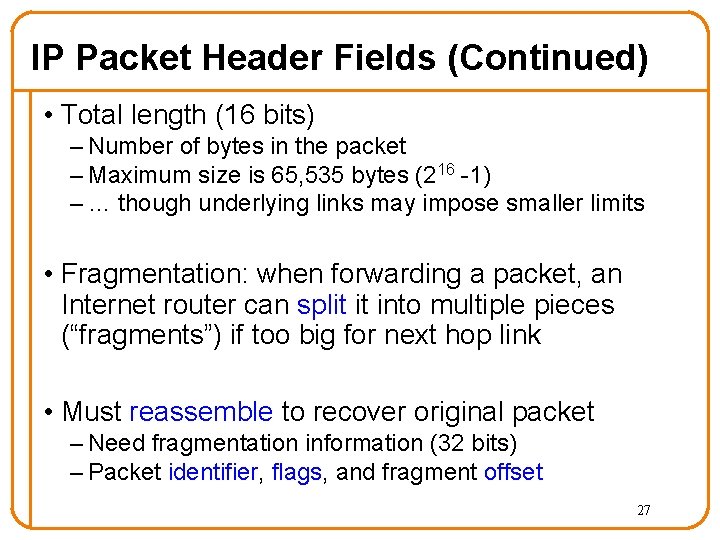

IP Packet Header Fields (Continued) • Total length (16 bits) – Number of bytes in the packet – Maximum size is 65, 535 bytes (216 -1) – … though underlying links may impose smaller limits • Fragmentation: when forwarding a packet, an Internet router can split it into multiple pieces (“fragments”) if too big for next hop link • Must reassemble to recover original packet – Need fragmentation information (32 bits) – Packet identifier, flags, and fragment offset 27

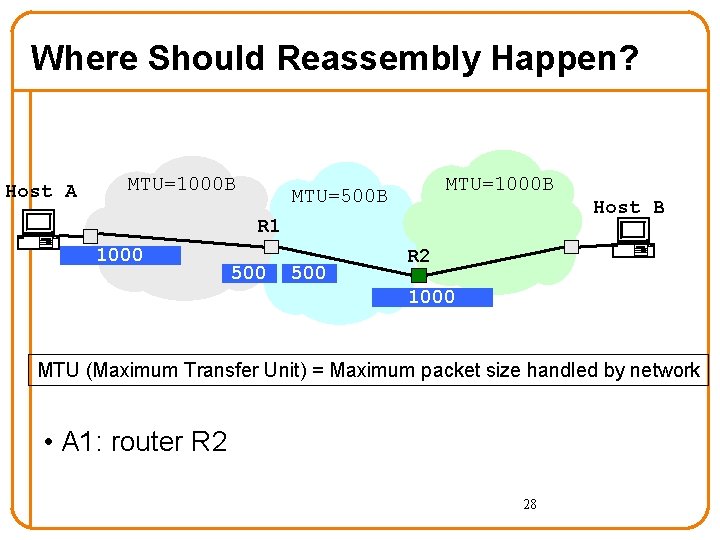

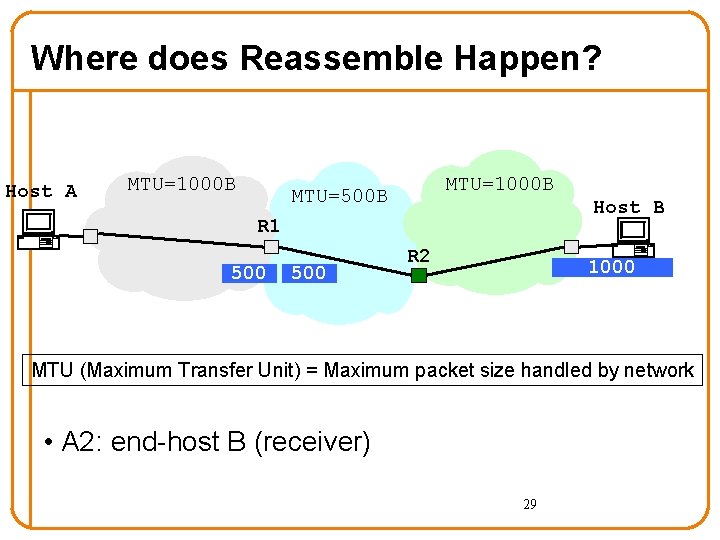

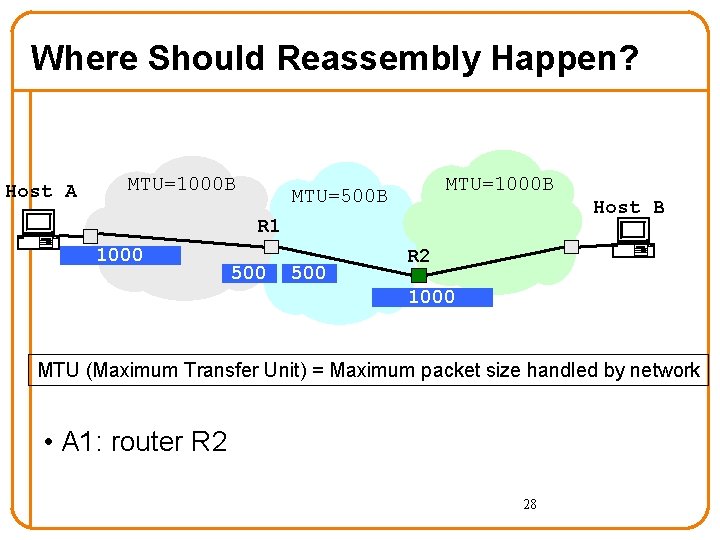

Where Should Reassembly Happen? Host A MTU=1000 B MTU=500 B Host B R 1 1000 500 R 2 1000 MTU (Maximum Transfer Unit) = Maximum packet size handled by network • A 1: router R 2 28

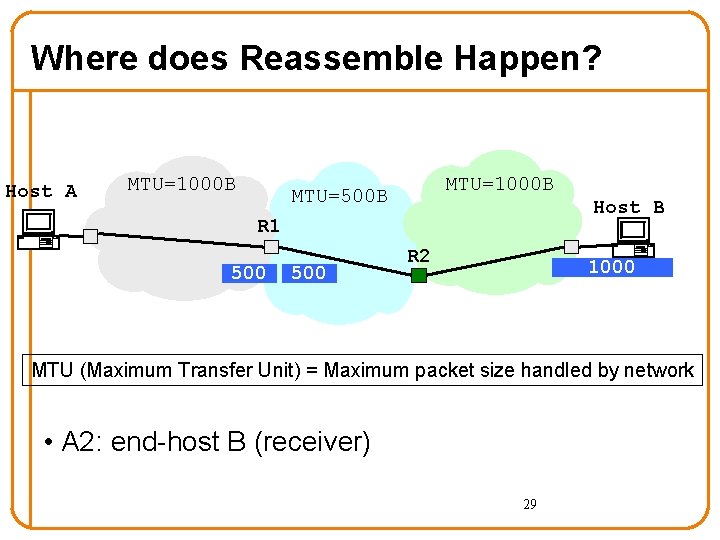

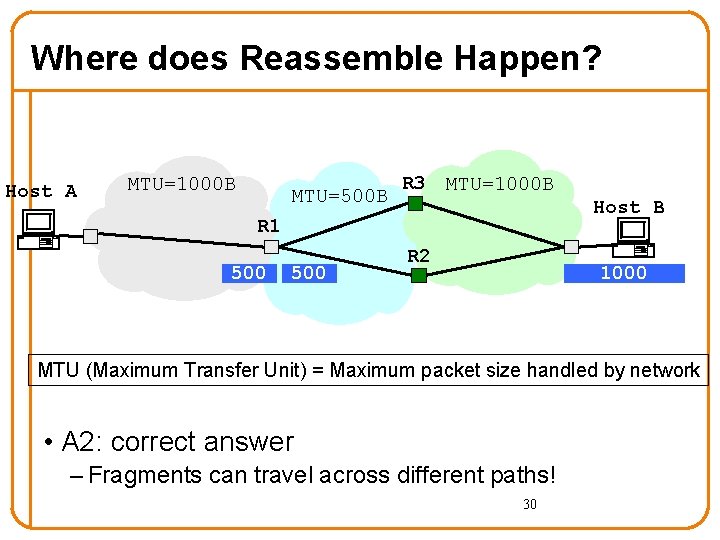

Where does Reassemble Happen? Host A MTU=1000 B MTU=500 B Host B R 1 500 R 2 1000 MTU (Maximum Transfer Unit) = Maximum packet size handled by network • A 2: end-host B (receiver) 29

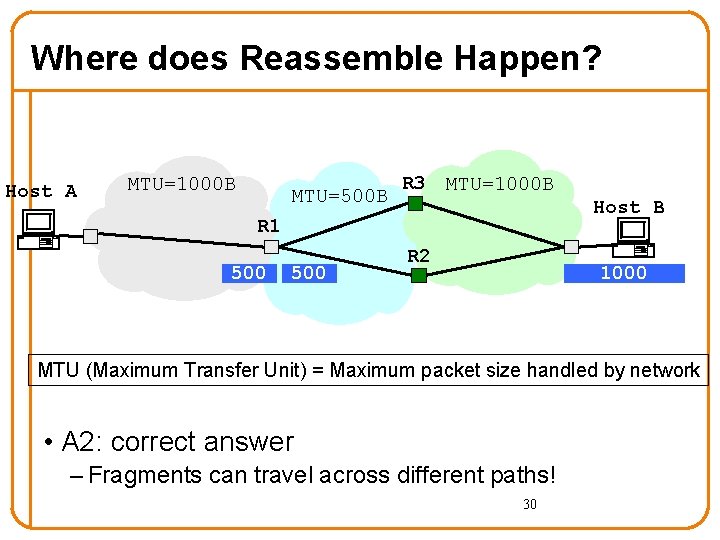

Where does Reassemble Happen? Host A MTU=1000 B MTU=500 B R 3 MTU=1000 B Host B R 1 500 R 2 1000 MTU (Maximum Transfer Unit) = Maximum packet size handled by network • A 2: correct answer – Fragments can travel across different paths! 30

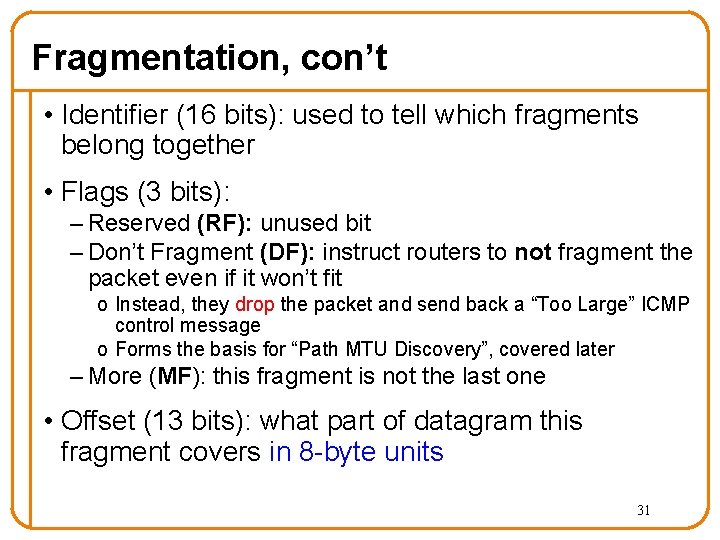

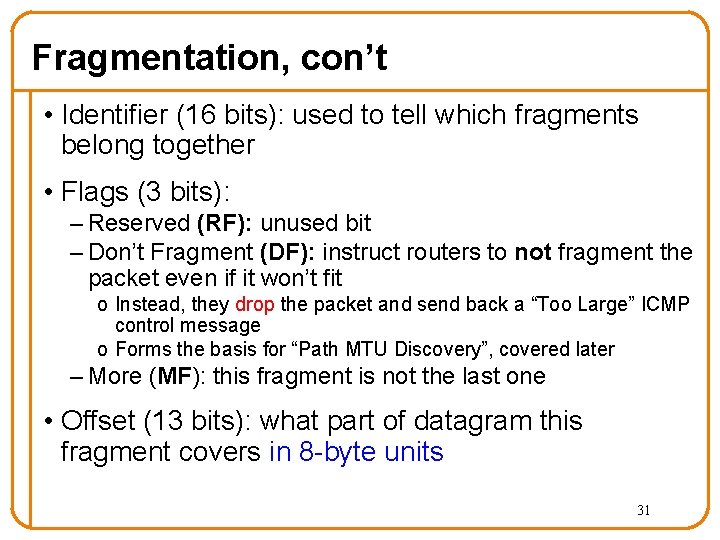

Fragmentation, con’t • Identifier (16 bits): used to tell which fragments belong together • Flags (3 bits): – Reserved (RF): unused bit – Don’t Fragment (DF): instruct routers to not fragment the packet even if it won’t fit o Instead, they drop the packet and send back a “Too Large” ICMP control message o Forms the basis for “Path MTU Discovery”, covered later – More (MF): this fragment is not the last one • Offset (13 bits): what part of datagram this fragment covers in 8 -byte units 31

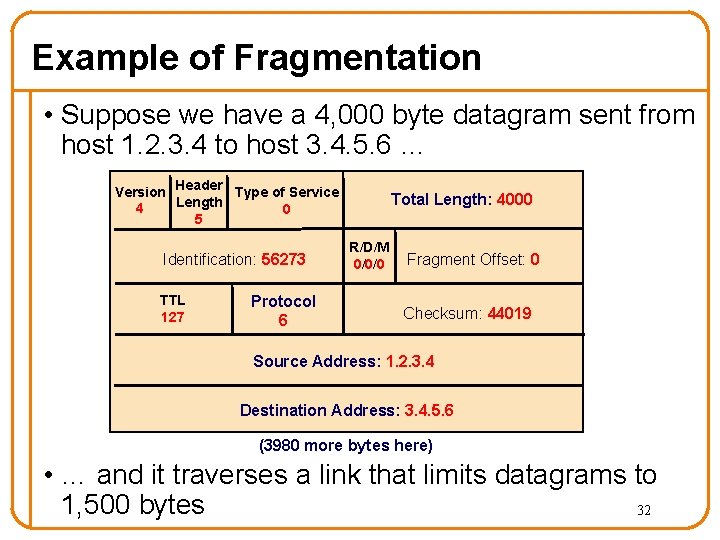

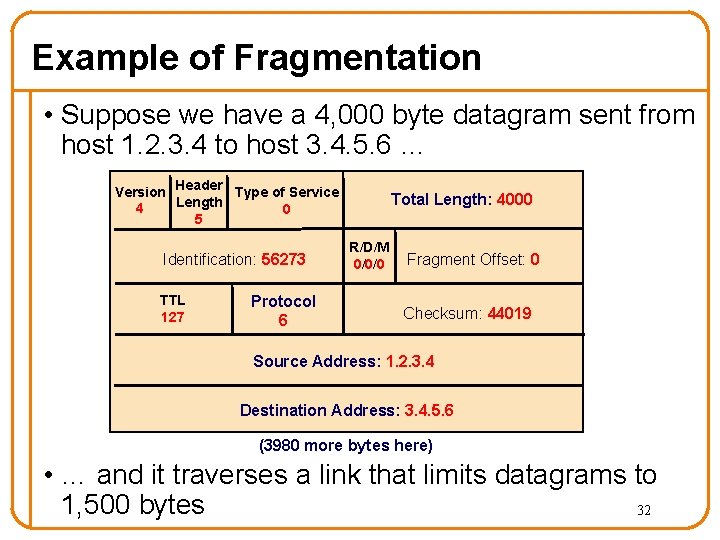

Example of Fragmentation • Suppose we have a 4, 000 byte datagram sent from host 1. 2. 3. 4 to host 3. 4. 5. 6 … Version Header Type of Service Length 4 0 5 Identification: 56273 TTL 127 Protocol 6 Total Length: 4000 R/D/M 0/0/0 Fragment Offset: 0 Checksum: 44019 Source Address: 1. 2. 3. 4 Destination Address: 3. 4. 5. 6 (3980 more bytes here) • … and it traverses a link that limits datagrams to 1, 500 bytes 32

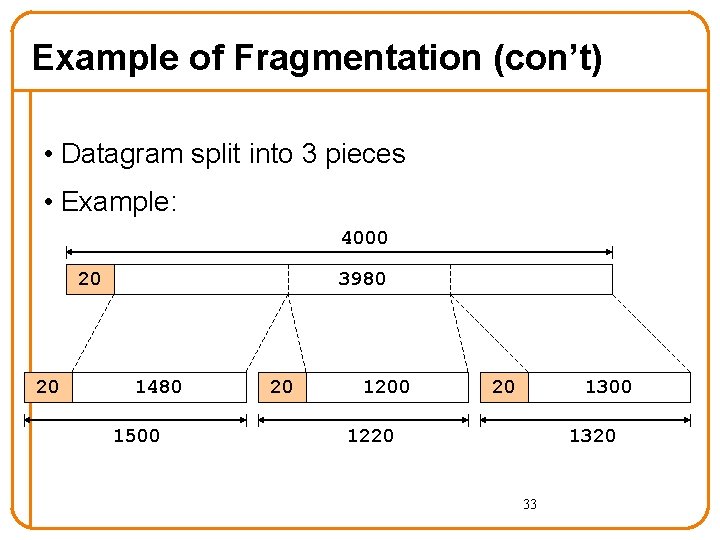

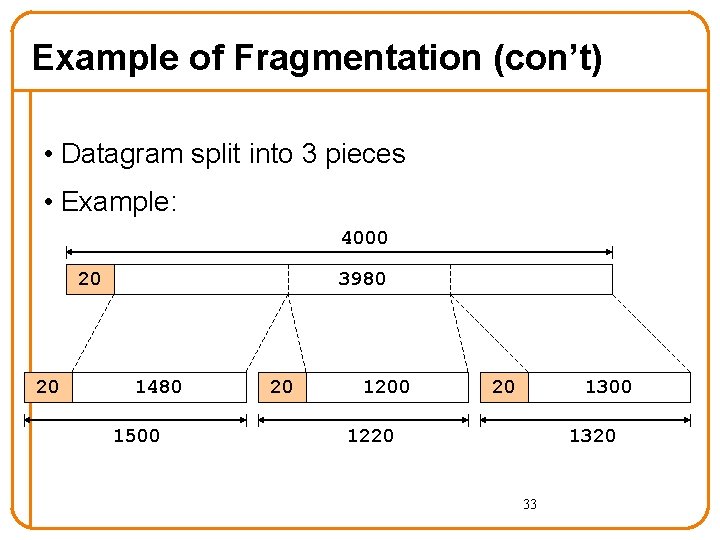

Example of Fragmentation (con’t) • Datagram split into 3 pieces • Example: 4000 20 20 3980 1480 1500 20 1200 20 1300 1220 1320 33

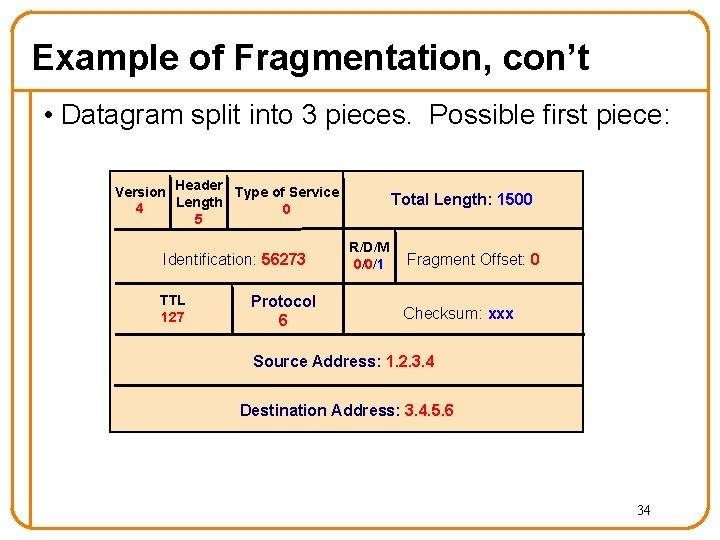

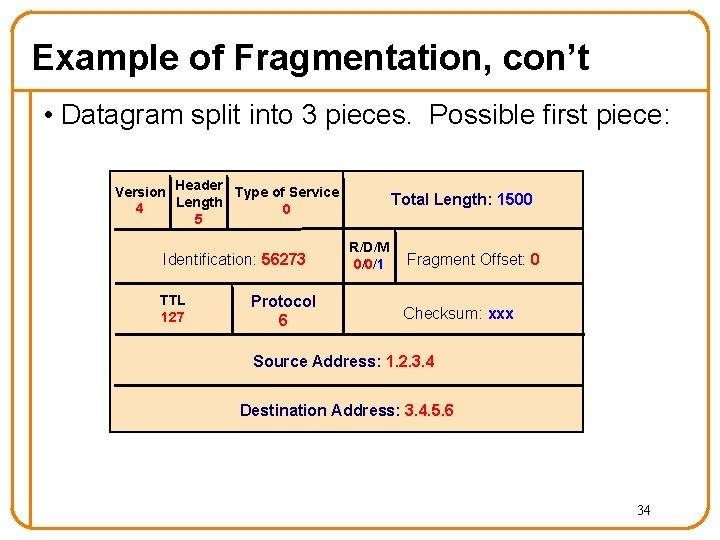

Example of Fragmentation, con’t • Datagram split into 3 pieces. Possible first piece: Version Header Type of Service Length 4 0 5 Identification: 56273 TTL 127 Protocol 6 Total Length: 1500 R/D/M 0/0/1 Fragment Offset: 0 Checksum: xxx Source Address: 1. 2. 3. 4 Destination Address: 3. 4. 5. 6 34

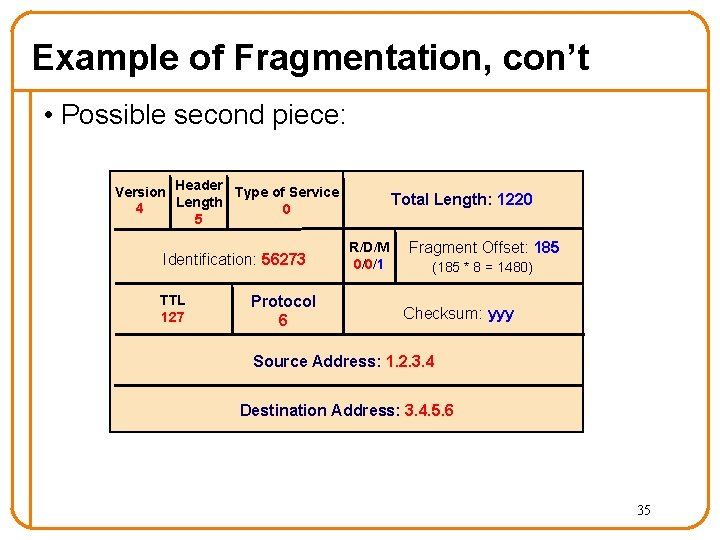

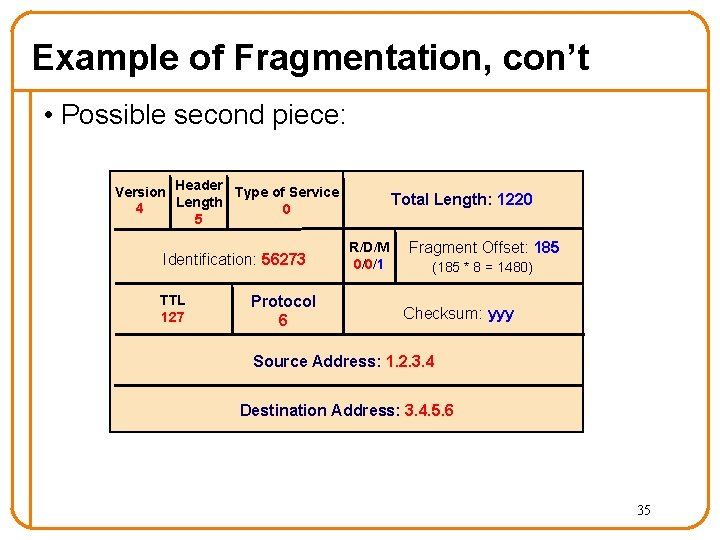

Example of Fragmentation, con’t • Possible second piece: Version Header Type of Service Length 4 0 5 Identification: 56273 TTL 127 Protocol 6 Total Length: 1220 R/D/M 0/0/1 Fragment Offset: 185 (185 * 8 = 1480) Checksum: yyy Source Address: 1. 2. 3. 4 Destination Address: 3. 4. 5. 6 35

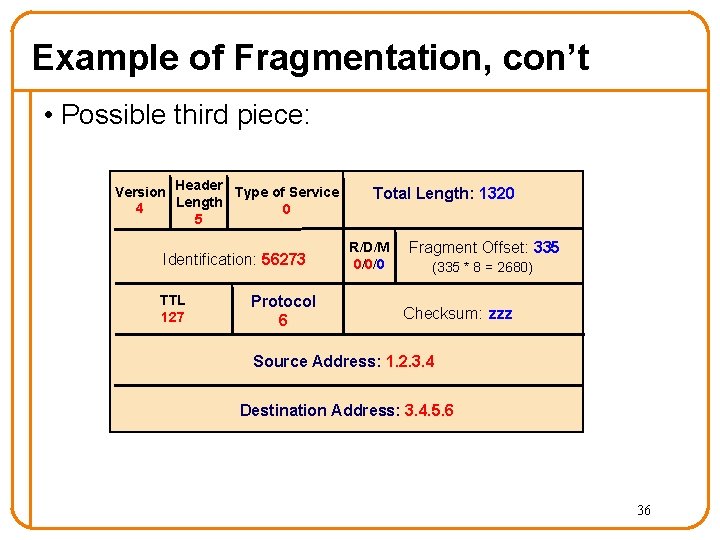

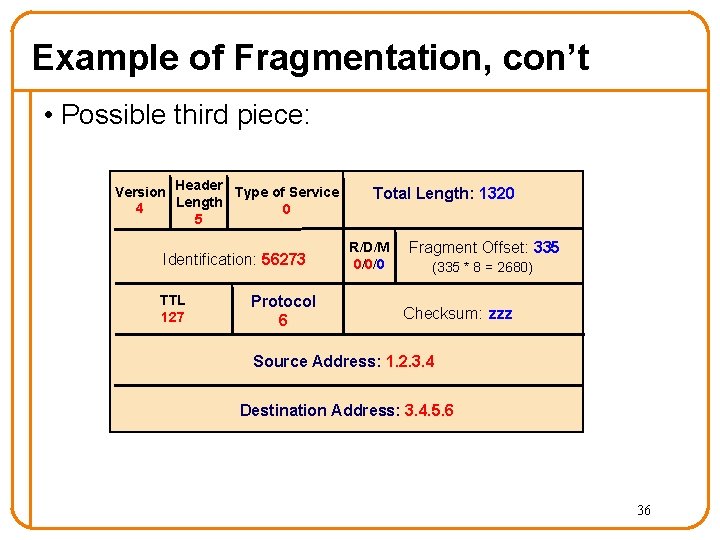

Example of Fragmentation, con’t • Possible third piece: Version Header Type of Service Length 4 0 5 Identification: 56273 TTL 127 Protocol 6 Total Length: 1320 R/D/M 0/0/0 Fragment Offset: 335 (335 * 8 = 2680) Checksum: zzz Source Address: 1. 2. 3. 4 Destination Address: 3. 4. 5. 6 36

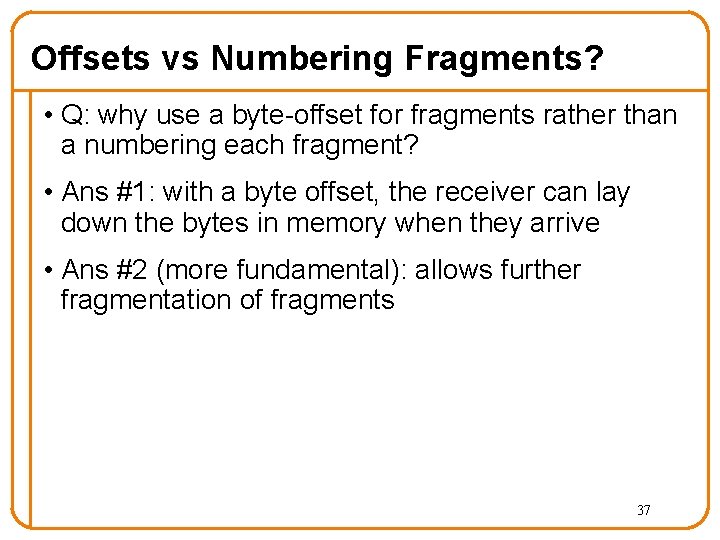

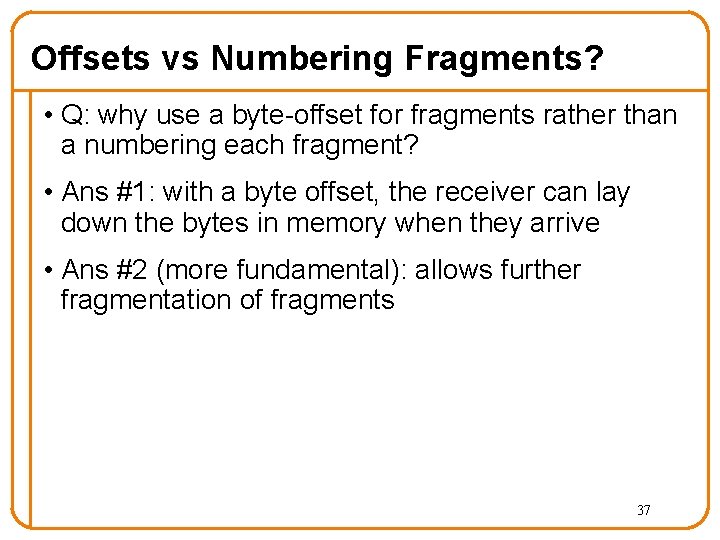

Offsets vs Numbering Fragments? • Q: why use a byte-offset for fragments rather than a numbering each fragment? • Ans #1: with a byte offset, the receiver can lay down the bytes in memory when they arrive • Ans #2 (more fundamental): allows further fragmentation of fragments 37

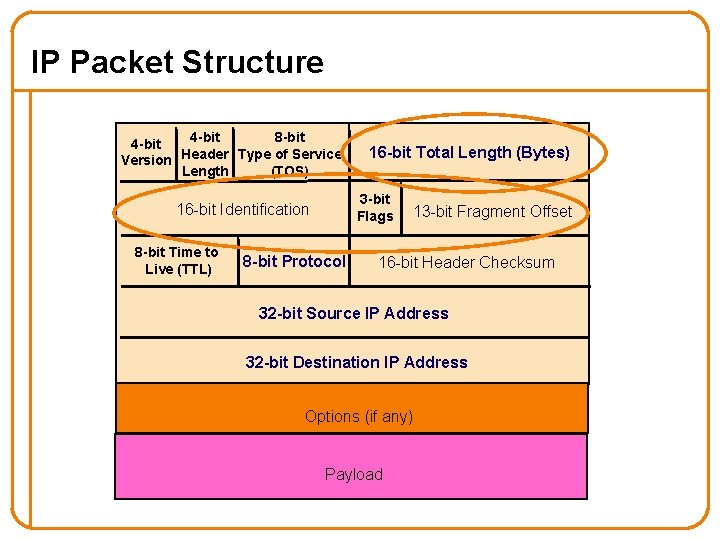

IP Packet Structure 4 -bit 8 -bit 4 -bit Version Header Type of Service Length (TOS) 3 -bit Flags 16 -bit Identification 8 -bit Time to Live (TTL) 16 -bit Total Length (Bytes) 8 -bit Protocol 13 -bit Fragment Offset 16 -bit Header Checksum 32 -bit Source IP Address 32 -bit Destination IP Address Options (if any) Payload

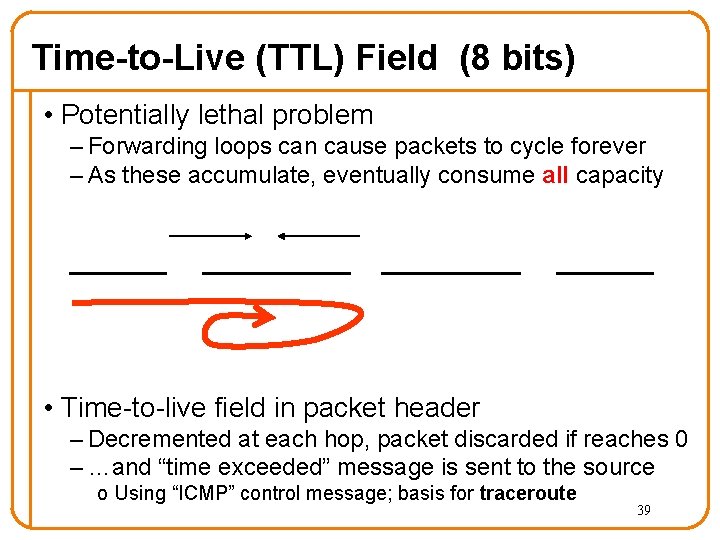

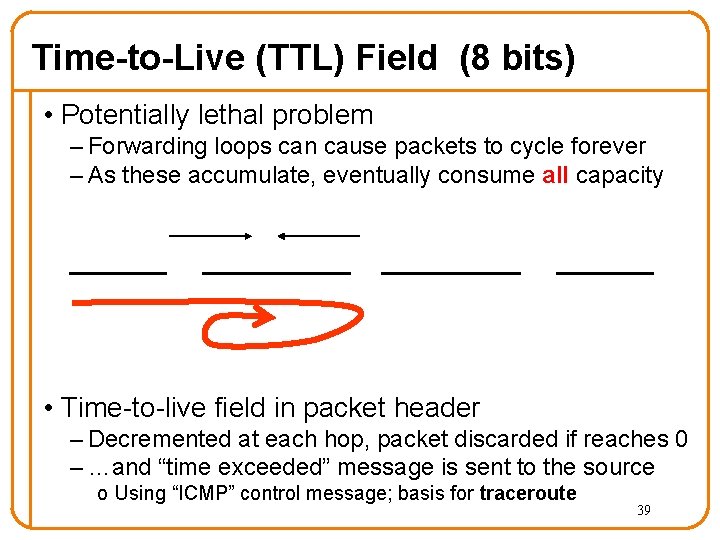

Time-to-Live (TTL) Field (8 bits) • Potentially lethal problem – Forwarding loops can cause packets to cycle forever – As these accumulate, eventually consume all capacity • Time-to-live field in packet header – Decremented at each hop, packet discarded if reaches 0 – …and “time exceeded” message is sent to the source o Using “ICMP” control message; basis for traceroute 39

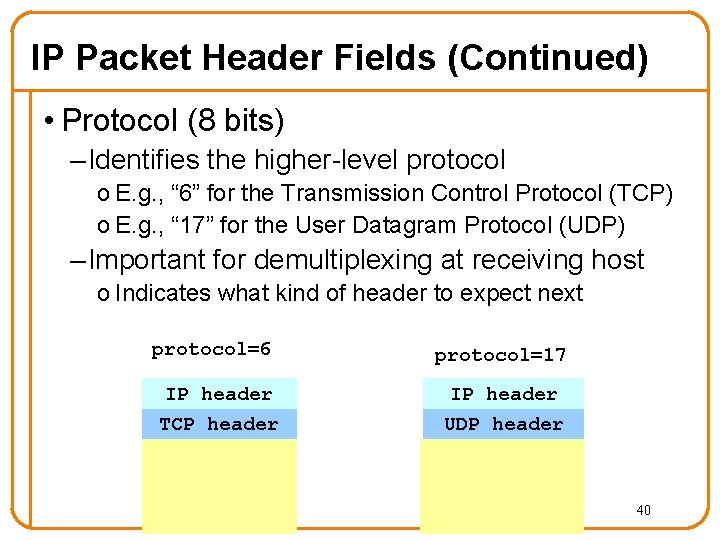

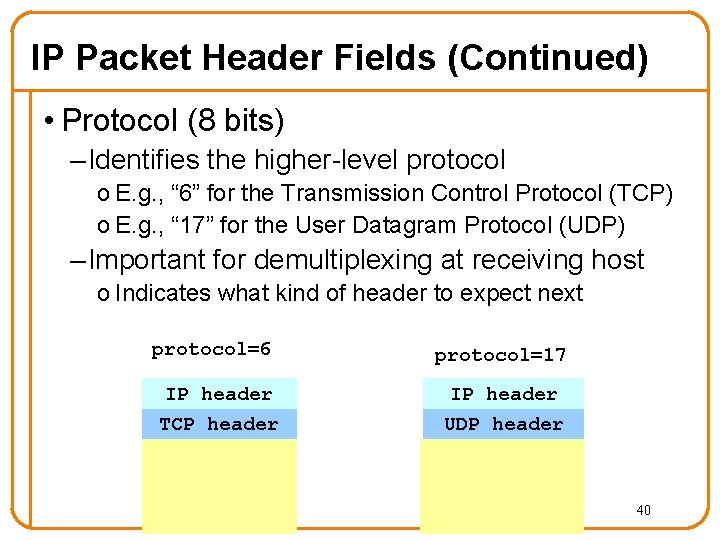

IP Packet Header Fields (Continued) • Protocol (8 bits) – Identifies the higher-level protocol o E. g. , “ 6” for the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) o E. g. , “ 17” for the User Datagram Protocol (UDP) – Important for demultiplexing at receiving host o Indicates what kind of header to expect next protocol=6 protocol=17 IP header TCP header UDP header 40

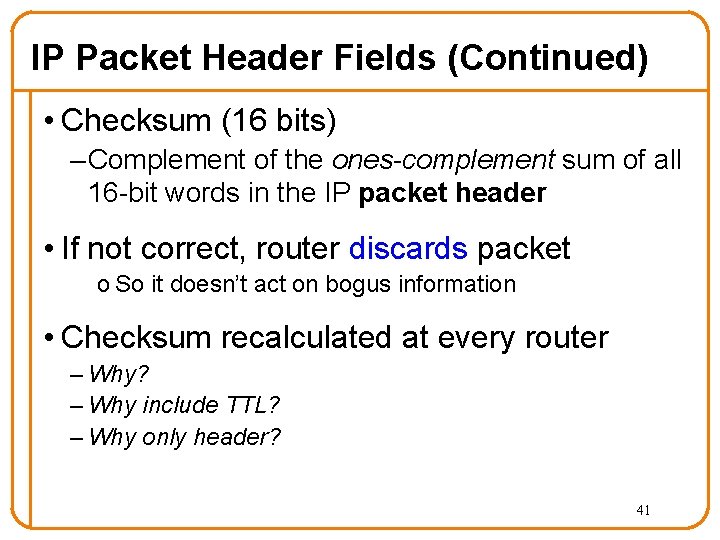

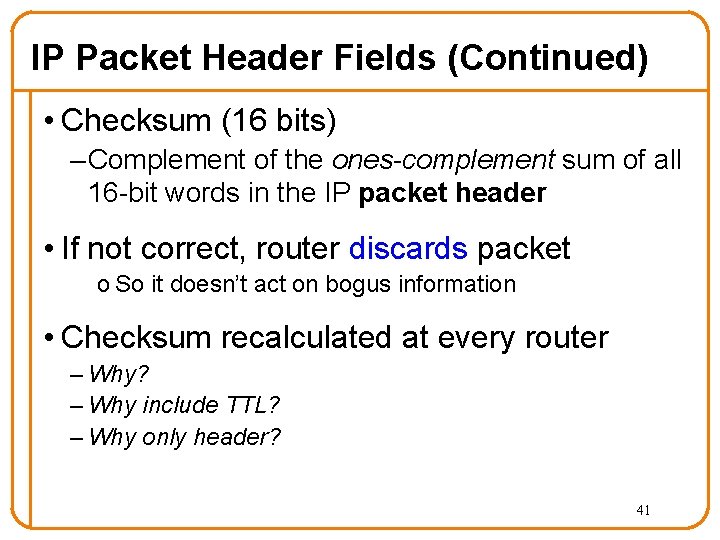

IP Packet Header Fields (Continued) • Checksum (16 bits) – Complement of the ones-complement sum of all 16 -bit words in the IP packet header • If not correct, router discards packet o So it doesn’t act on bogus information • Checksum recalculated at every router – Why? – Why include TTL? – Why only header? 41

IP Packet Structure 4 -bit 8 -bit 4 -bit Version Header Type of Service Length (TOS) 3 -bit Flags 16 -bit Identification 8 -bit Time to Live (TTL) 16 -bit Total Length (Bytes) 8 -bit Protocol 13 -bit Fragment Offset 16 -bit Header Checksum 32 -bit Source IP Address 32 -bit Destination IP Address Options (if any) Payload

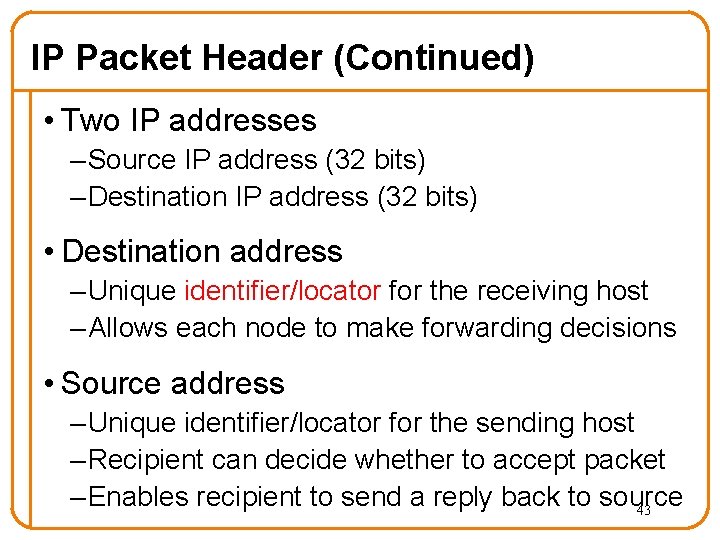

IP Packet Header (Continued) • Two IP addresses – Source IP address (32 bits) – Destination IP address (32 bits) • Destination address – Unique identifier/locator for the receiving host – Allows each node to make forwarding decisions • Source address – Unique identifier/locator for the sending host – Recipient can decide whether to accept packet – Enables recipient to send a reply back to source 43

IPv 6

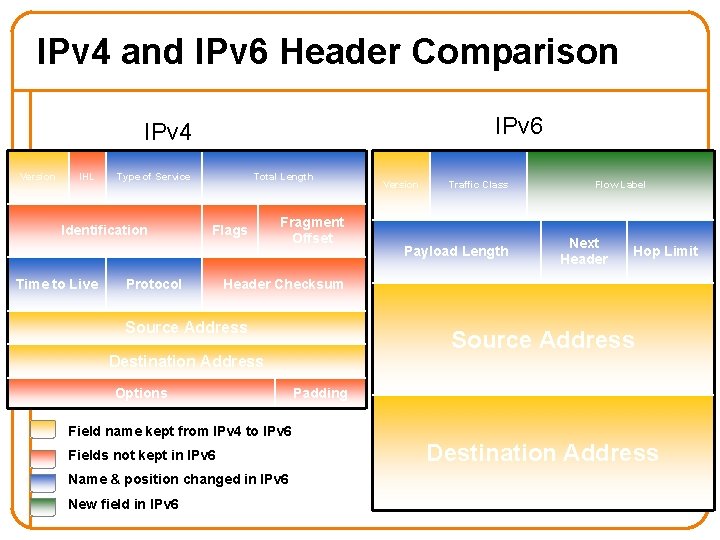

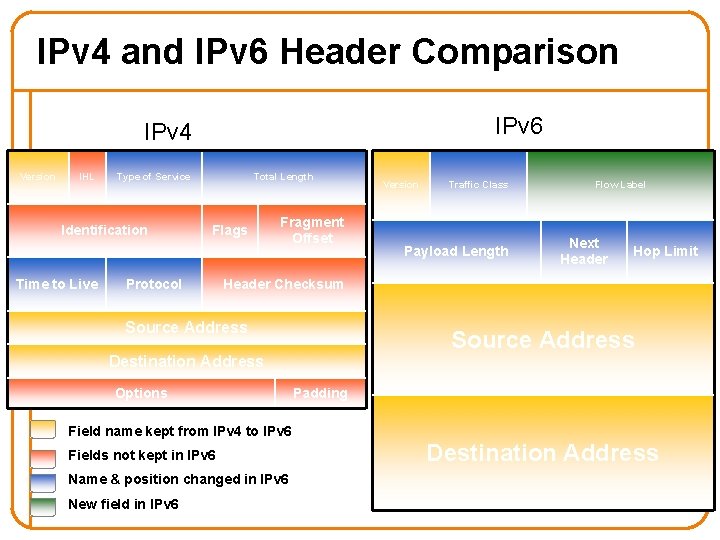

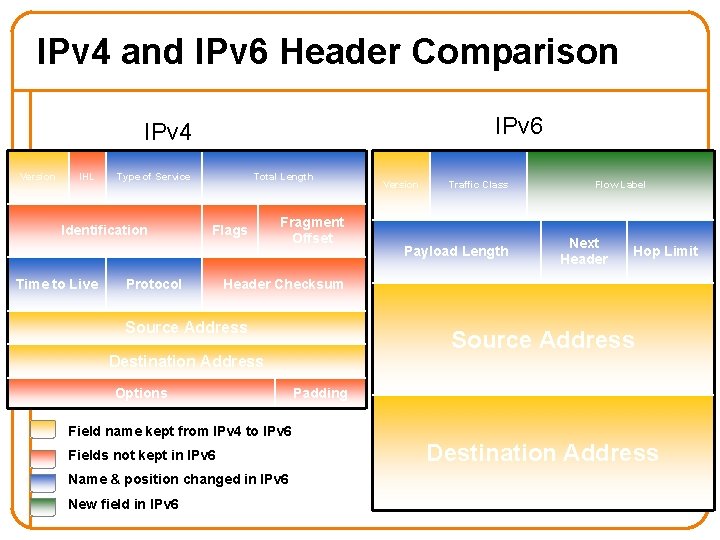

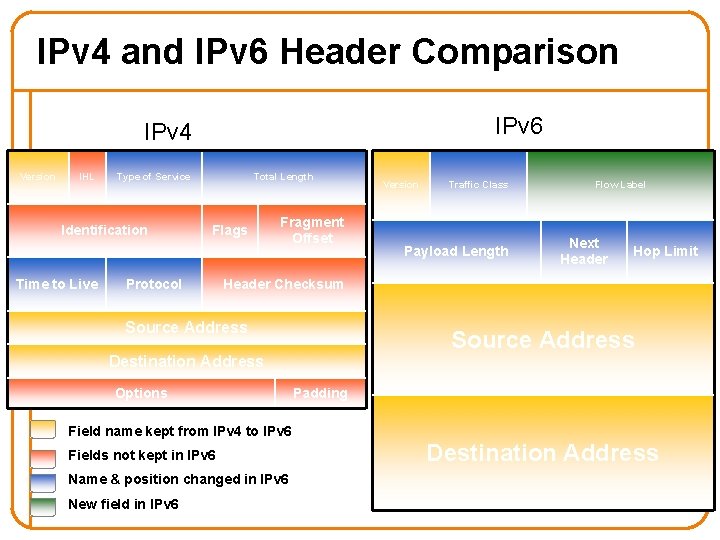

IPv 4 and IPv 6 Header Comparison IPv 6 IPv 4 Version IHL Type of Service Identification Time to Live Total Length Flags Protocol Fragment Offset Version Traffic Class Payload Length Flow Label Next Header Hop Limit Header Checksum Source Address Destination Address Options Padding Field name kept from IPv 4 to IPv 6 Fields not kept in IPv 6 Name & position changed in IPv 6 New field in IPv 6 Destination Address

Summary of Changes • Eliminated fragmentation • Eliminated header length • Eliminated checksum • New options mechanism (next header) • Expanded addresses • Added Flow Label 46

IPv 4 and IPv 6 Header Comparison IPv 6 IPv 4 Version IHL Type of Service Identification Time to Live Total Length Flags Protocol Fragment Offset Version Traffic Class Payload Length Flow Label Next Header Hop Limit Header Checksum Source Address Destination Address Options Padding Field name kept from IPv 4 to IPv 6 Fields not kept in IPv 6 Name & position changed in IPv 6 New field in IPv 6 Destination Address

Next Lecture • IP Addressing • Read K&R: 4. 4. 2 • If you want to check out IPv 6: K&R 4. 4. 4 48