Design of Digital Circuits Lecture 6 Combinational Logic

Design of Digital Circuits Lecture 6: Combinational Logic, Hardware Description Lang. & Verilog Prof. Onur Mutlu ETH Zurich Spring 2018 9 March 2018

Required Lecture Video n Why study computer architecture? Why is it important? Future Computing Architectures n Required Assignment n n q q n Watch my inaugural lecture at ETH and understand it https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=kgi. Zl. SOc. GFM Optional Assignment q Write a summary of the lecture n n n What are your key takeaways? What did you learn? What did you like or dislike? 2

Required Readings n This week q Combinational Logic n q Hardware Description Languages and Verilog n n H&H Chapter 4 until 4. 3 and 4. 5 Next week q Sequential Logic n q P&P Chapter 3. 4 until end + H&H Chapter 3 in full Hardware Description Languages and Verilog n n P&P Chapter 3 until 3. 3 + H&H Chapter 2 H&H Chapter 4 in full Make sure you are done with q P&P Chapters 1 -3 + H&H Chapters 1 -4 3

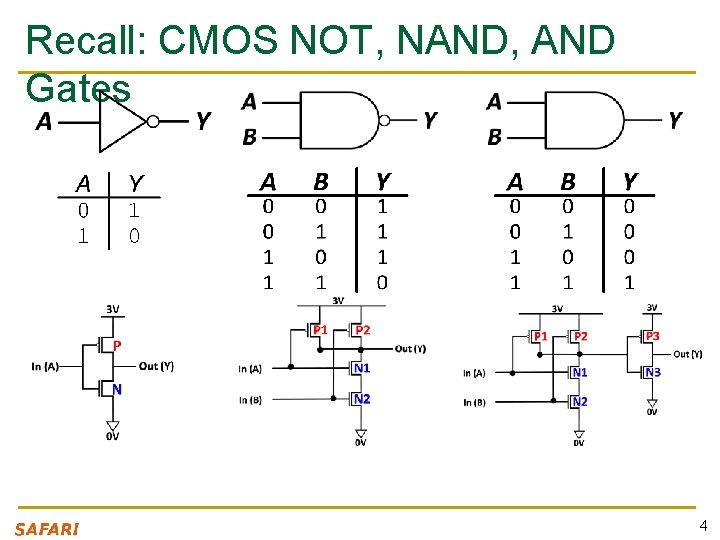

Recall: CMOS NOT, NAND, AND Gates 4

Recall: General CMOS Gate Structure n The general form used to construct any inverting logic gate, such as: NOT, NAND, or NOR q q q The networks may consist of transistors in series or in parallel When transistors are in parallel, the network is ON if one of the transistors is ON When transistors are in series, the network is ON only if all transistors are ON p. MOS transistors are used for pull-up n. MOS transistors are used for pull-down 5

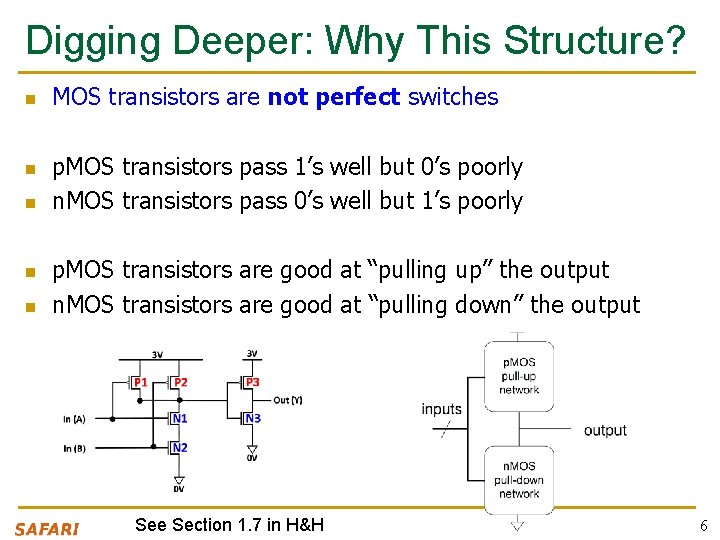

Digging Deeper: Why This Structure? n n n MOS transistors are not perfect switches p. MOS transistors pass 1’s well but 0’s poorly n. MOS transistors pass 0’s well but 1’s poorly p. MOS transistors are good at “pulling up” the output n. MOS transistors are good at “pulling down” the output See Section 1. 7 in H&H 6

Digging Deeper: Latency n Which one is faster? q q n Series connections are slower than parallel connections q n Transistors in series Transistors in parallel More resistance on the wire How do you alleviate this latency? q See H&H Section 1. 7. 8 for an example: pseudo-n. MOS Logic 7

Digging Deeper: Power Consumption n Dynamic Power Consumption q C * V 2 * f n n Static Power consumption q V * Ileakage n n C = capacitance of the circuit (wires and gates) V = supply voltage f = charging frequency of the capacitor supply voltage * leakage current See more in H&H Chapter 1. 8 8

Recall: De. Morgan’s Law (Continued) These are conversions between different types of logic functions They can prove useful if you do not have every type of gate NOR is equivalent to AND with inputs complemented NAND is equivalent to OR with inputs complemented 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 9

Using Boolean Equations to Represent a Logic Circuit 10

Sum of Products Form: Key Idea n n Assume we have the truth table of a Boolean Function How do we express the function in terms of the inputs in a standard manner? Idea: Sum of Products form Express the truth table as a two-level Boolean expression q q q that contains all input variable combinations that result in a 1 output If ANY of the combinations of input variables that results in a 1 is TRUE, then the output is 1 F = OR of all input variable combinations that result in a 1 11

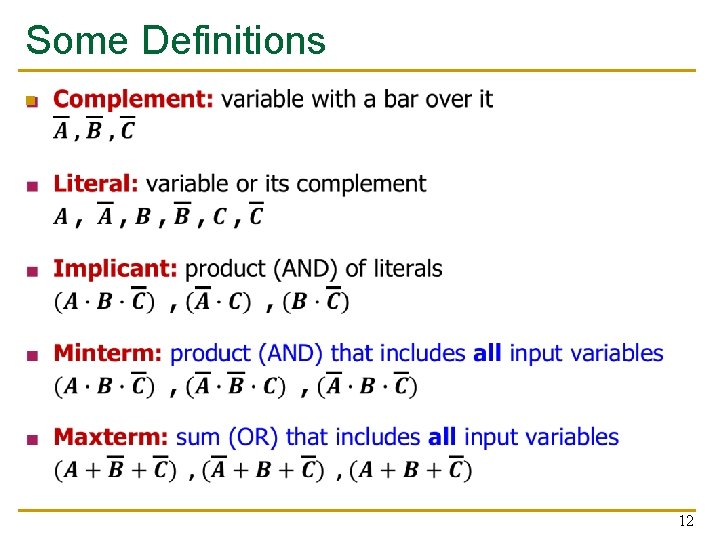

Some Definitions n 12

Two-Level Canonical (Standard) Forms n Truth table is the unique signature of a Boolean function … q n A Boolean function can have many alternative Boolean expressions q n But, it is an expensive representation i. e. , many alternative Boolean expressions (and gate realizations) may have the same truth table (and function) Canonical form: standard form for a Boolean expression q q Provides a unique algebraic signature If they all say the same thing, why do we care? n Different Boolean expressions lead to different gate realizations 13

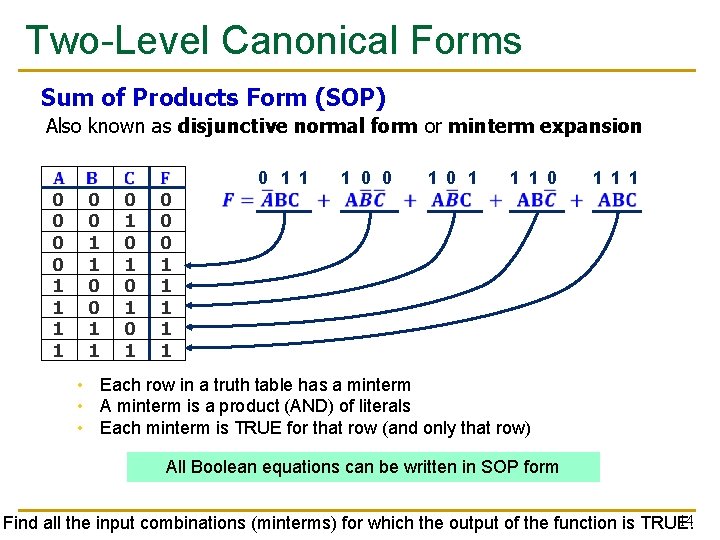

Two-Level Canonical Forms Sum of Products Form (SOP) Also known as disjunctive normal form or minterm expansion 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 • Each row in a truth table has a minterm • A minterm is a product (AND) of literals • Each minterm is TRUE for that row (and only that row) All Boolean equations can be written in SOP form 14 Find all the input combinations (minterms) for which the output of the function is TRUE.

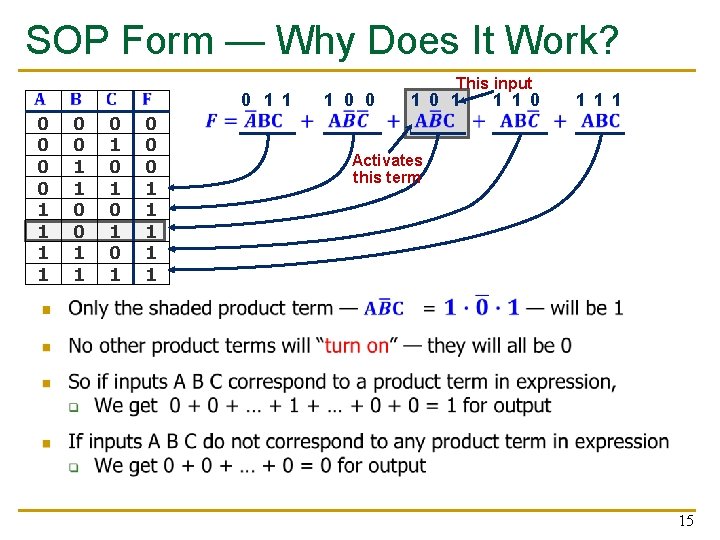

SOP Form — Why Does It Work? 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 This input 1 0 1 1 1 Activates this term 15

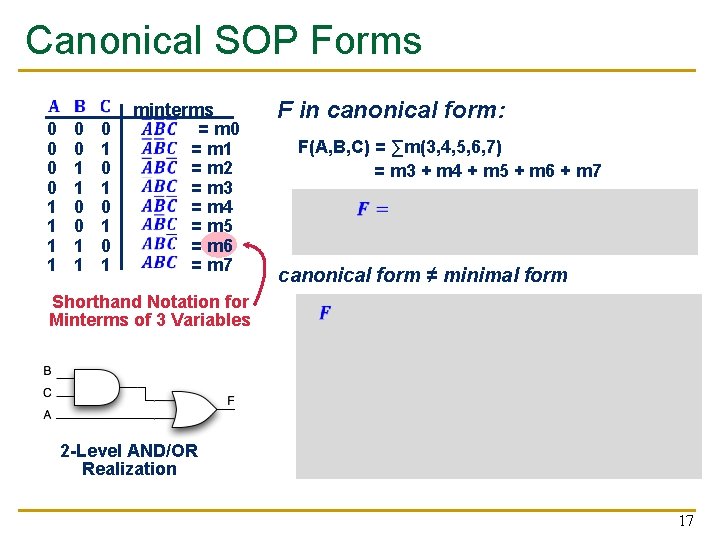

Aside: Notation for SOP Standard “shorthand” notation n q If we agree on the order of the variables in the rows of truth table… n 0 0 1 1 then we can enumerate each row with the decimal number that corresponds to the binary number created by the input pattern 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 100 = decimal 4 so this is minterm #4, or m 4 111 = decimal 7 so this is minterm #7, or m 7 f = m 3 + m 4 + m 5 + m 6 + m 7 = ∑m(3, 4, 5, 6, 7) We can write this as a sum of products Or, we can use a summation notation 16

Canonical SOP Forms 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 minterms = m 0 = m 1 = m 2 = m 3 = m 4 = m 5 = m 6 = m 7 Shorthand Notation for Minterms of 3 Variables F in canonical form: F(A, B, C) = ∑m(3, 4, 5, 6, 7) = m 3 + m 4 + m 5 + m 6 + m 7 canonical form ≠ minimal form 2 -Level AND/OR Realization 17

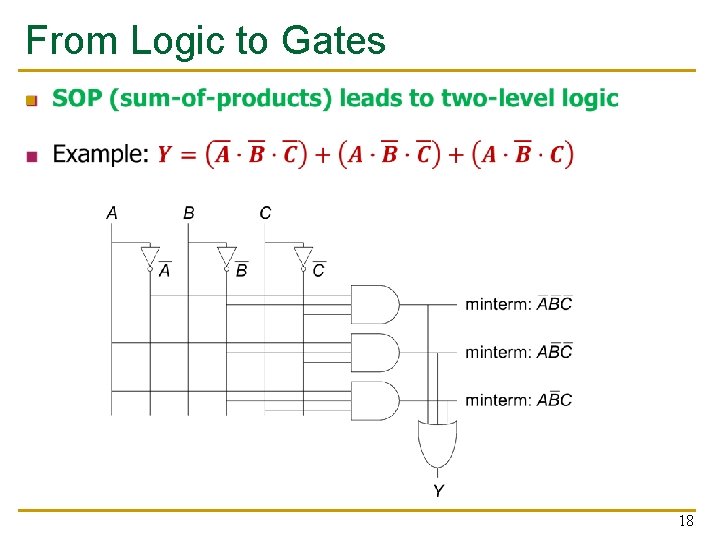

From Logic to Gates n 18

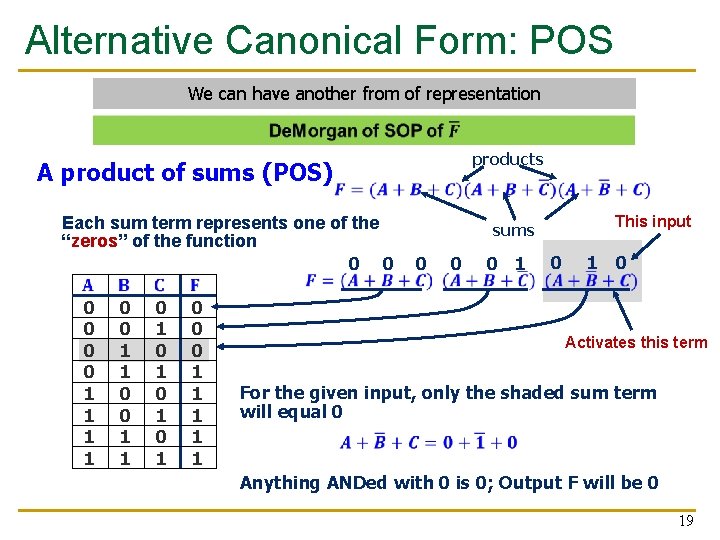

Alternative Canonical Form: POS We can have another from of representation A product of sums (POS) products This input Each sum term represents one of the sums “zeros” of the function 0 0 0 1 0 Activates this term 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 For the given input, only the shaded sum term 1 0 0 1 will equal 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 Anything ANDed with 0 is 0; Output F will be 0 19

Consider A=0, B=1, C=0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 Input 0 1 0 1 1 0 Only one of the products will be 0, anything ANDed with 0 is 0 Therefore, the output is F = 0 20

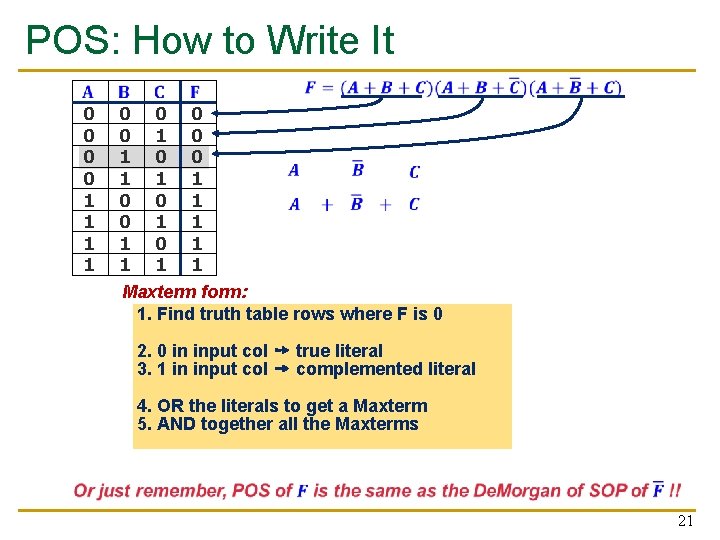

POS: How to Write It 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 Maxterm form: 1. Find truth table rows where F is 0 2. 0 in input col ➙ true literal 3. 1 in input col ➙ complemented literal 4. OR the literals to get a Maxterm 5. AND together all the Maxterms 21

Canonical POS Forms Product of Sums / Conjunctive Normal Form / Maxterm Expansion 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 Maxterms = M 0 = M 1 = M 2 = M 3 = M 4 = M 5 = M 6 = M 7 Maxterm shorthand notation for a function of three variables 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 Note that you form the maxterms around the “zeros” of the function This is not the complement of the function! 22

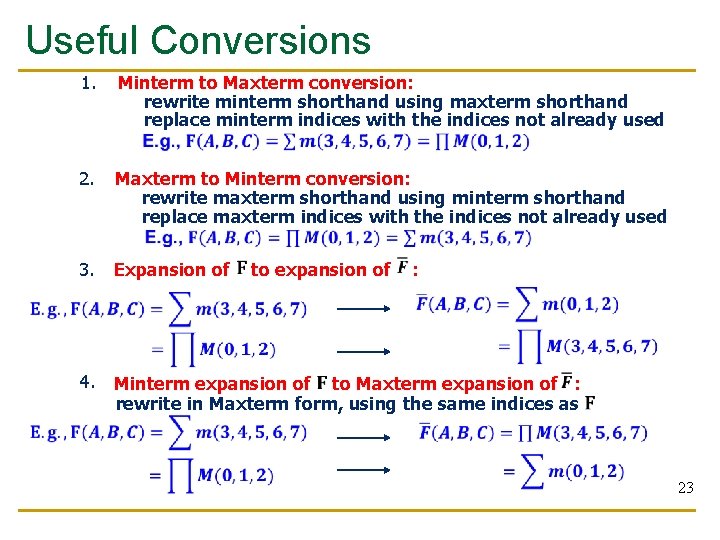

Useful Conversions 1. Minterm to Maxterm conversion: rewrite minterm shorthand using maxterm shorthand replace minterm indices with the indices not already used 2. Maxterm to Minterm conversion: rewrite maxterm shorthand using minterm shorthand replace maxterm indices with the indices not already used 3. Expansion of to expansion of : 4. Minterm expansion of to Maxterm expansion of : rewrite in Maxterm form, using the same indices as 23

Combinational Building Blocks used in Modern Computers 24

Combinational Building Blocks n n n Combinational logic is often grouped into larger building blocks to build more complex systems Hides the unnecessary gate-level details to emphasize the function of the building block We now look at: q q Decoders Multiplexers Full adder PLA 25

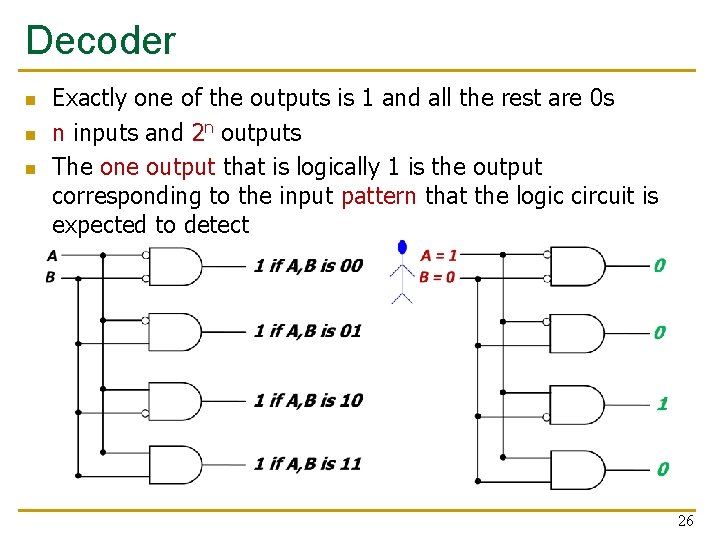

Decoder n n n Exactly one of the outputs is 1 and all the rest are 0 s n inputs and 2 n outputs The one output that is logically 1 is the output corresponding to the input pattern that the logic circuit is expected to detect 26

Decoder n The decoder is useful in determining how to interpret a bit pattern q q It could be the address of a row in DRAM, that the processor intends to read from It could be an instruction in the program and the processor has to decide what action to do! (based on instruction opcode) 27

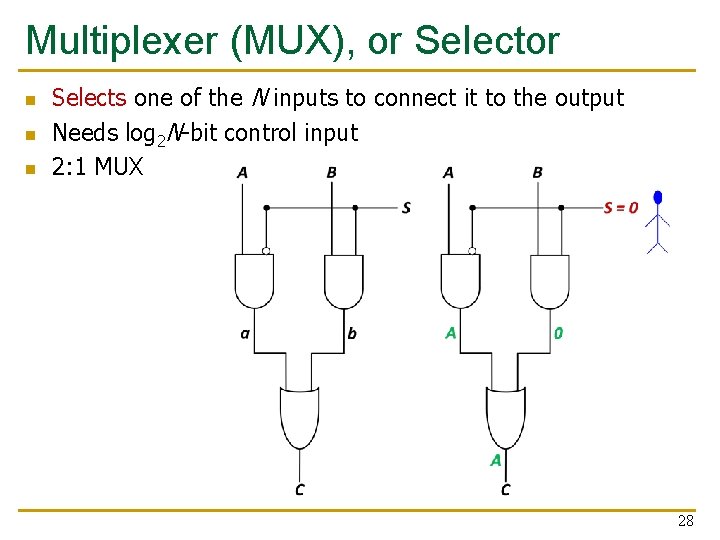

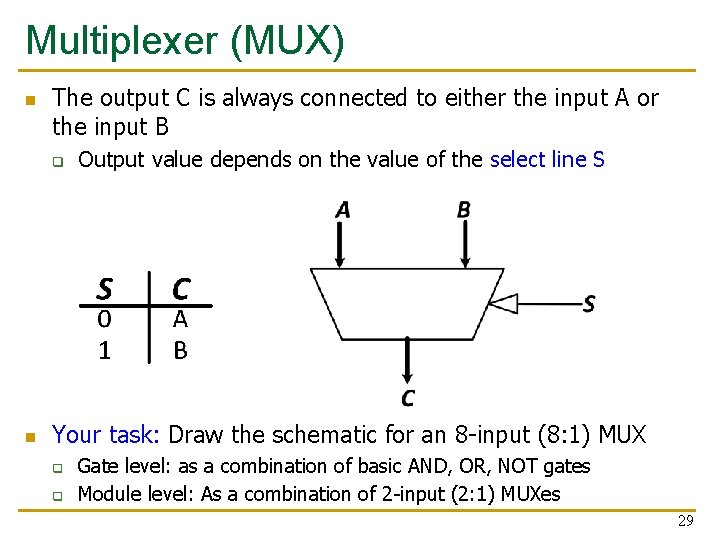

Multiplexer (MUX), or Selector n n n Selects one of the N inputs to connect it to the output Needs log 2 N-bit control input 2: 1 MUX 28

Multiplexer (MUX) n The output C is always connected to either the input A or the input B q n Output value depends on the value of the select line S Your task: Draw the schematic for an 8 -input (8: 1) MUX q q Gate level: as a combination of basic AND, OR, NOT gates Module level: As a combination of 2 -input (2: 1) MUXes 29

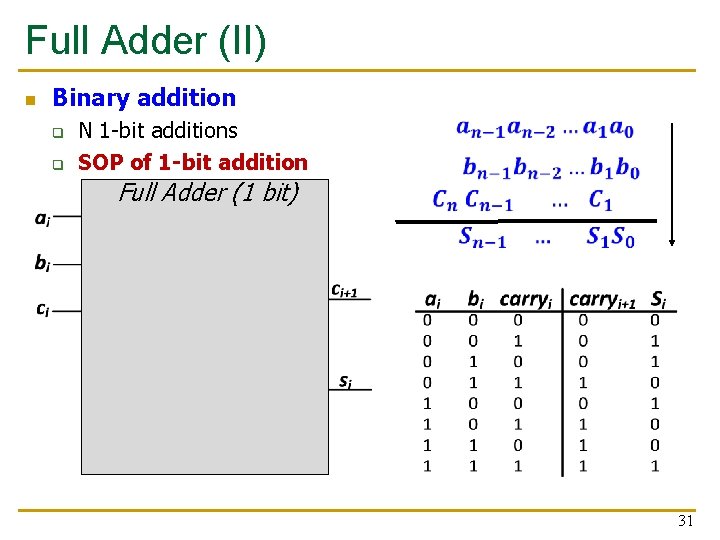

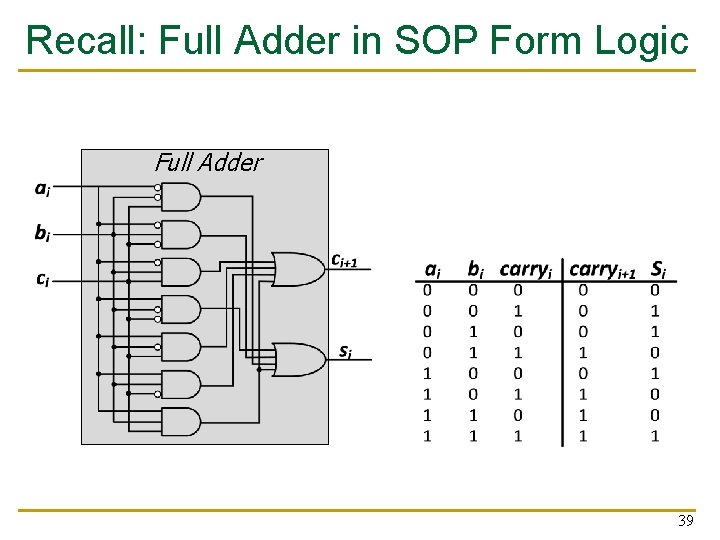

Full Adder (I) n Binary addition q q n Similar to decimal addition From right to left One column at a time One sum and one carry bit Truth table of binary addition on one column of bits within two n-bit operands 30

Full Adder (II) n Binary addition q q N 1 -bit additions SOP of 1 -bit addition Full Adder (1 bit) 31

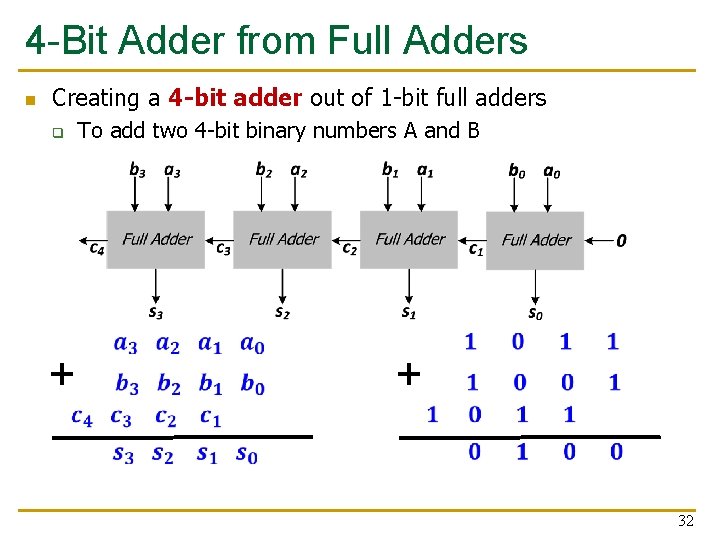

4 -Bit Adder from Full Adders n Creating a 4 -bit adder out of 1 -bit full adders To add two 4 -bit binary numbers A and B q + + 32

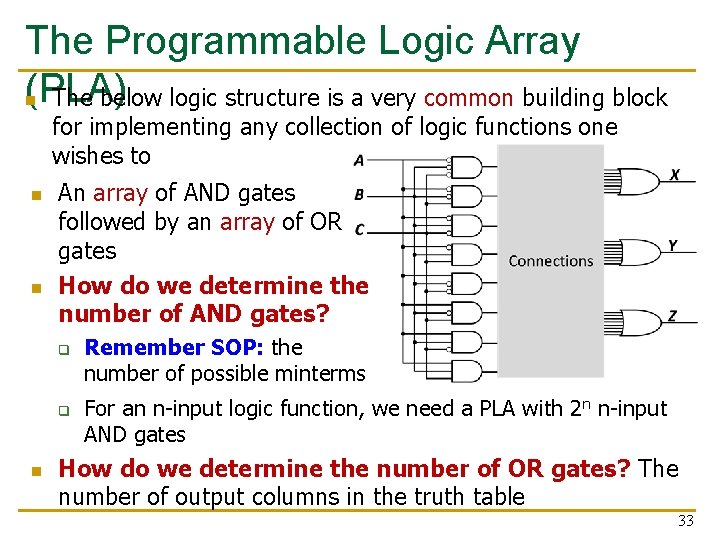

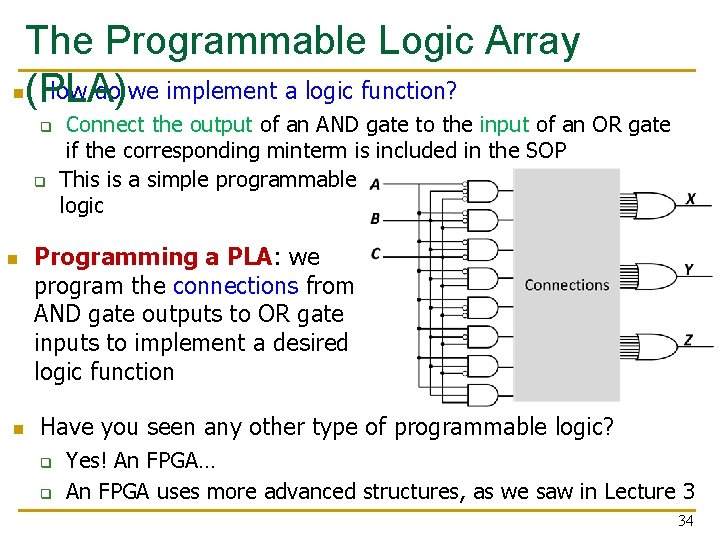

The Programmable Logic Array (PLA) n The below logic structure is a very common building block for implementing any collection of logic functions one wishes to n n An array of AND gates followed by an array of OR gates How do we determine the number of AND gates? q q n Remember SOP: the number of possible minterms For an n-input logic function, we need a PLA with 2 n n-input AND gates How do we determine the number of OR gates? The number of output columns in the truth table 33

The Programmable Logic Array n(PLA) How do we implement a logic function? q q n n Connect the output of an AND gate to the input of an OR gate if the corresponding minterm is included in the SOP This is a simple programmable logic Programming a PLA: we program the connections from AND gate outputs to OR gate inputs to implement a desired logic function Have you seen any other type of programmable logic? q q Yes! An FPGA… An FPGA uses more advanced structures, as we saw in Lecture 3 34

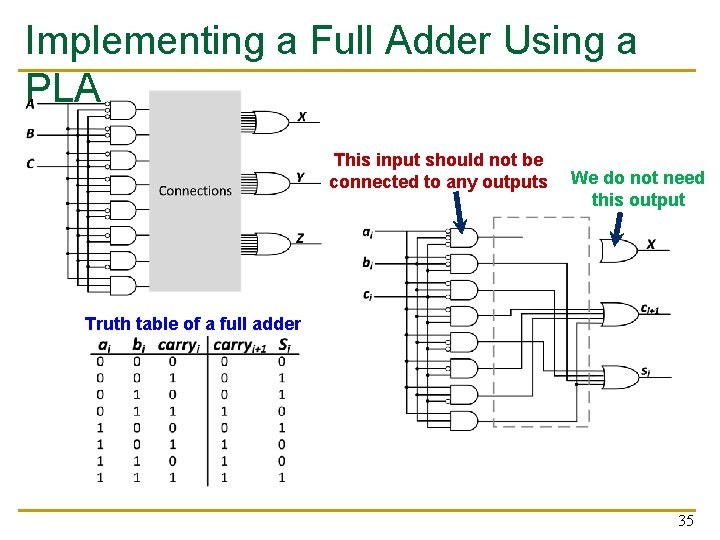

Implementing a Full Adder Using a PLA This input should not be connected to any outputs We do not need this output Truth table of a full adder 35

Logical (Functional) Completeness n Any logic function we wish to implement could be accomplished with PLA q q n n PLA consists of only AND gates, OR gates, and inverters We just have to program connections based on SOP of the intended logic function The set of gates {AND, OR, NOT} is logically complete because we can build a circuit to carry out the specification of any truth table we wish, without using any other kind of gate NAND is also logically complete. So is NOR. q Your task: Prove this. 36

More Combinational Building Blocks n H&H Chapter 5 n Will be required reading soon. n You will benefit greatly by reading the “combinational” parts of that chapter soon. q Sections 5. 1 and 5. 2 37

Logic Simplification: Karnaugh Maps (KMaps) 38

Recall: Full Adder in SOP Form Logic Full Adder 39

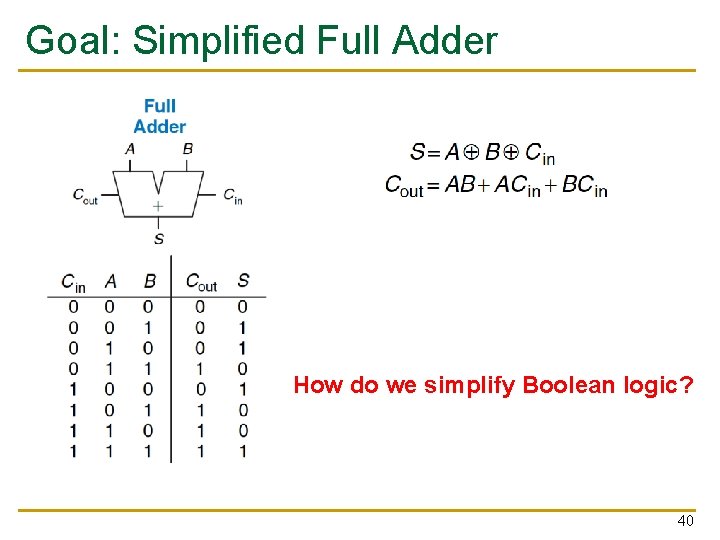

Goal: Simplified Full Adder How do we simplify Boolean logic? 40

Quick Recap on Logic Simplification n The original Boolean expression (i. e. , logic circuit) may not be optimal F = ~A(A + B) + (B + AA)(A + ~B) n Can we reduce a given Boolean expression to an equivalent expression with fewer terms? F = A + B n The goal of logic simplification: q q Reduce the number of gates/inputs Reduce implementation cost A basis for what the automated design tools are doing today 41

Logic Simplification n Systematic techniques for simplifications q amenable to automation Key Tool: The Uniting Theorem — B's values change within the rows where F==1 (“ON set”) Essence of Simplification: A's values don't change within the ON-set rows Find two element subsets of the ON-set where only one variable If an input (B) can change without changing the output, that input changes its value. This single varying variable can be eliminated! value is not needed ➙ B is eliminated, A remains B's values stay the same within the ON-set rows A's values change within the ON-set rows ➙ A is eliminated, B remains 42

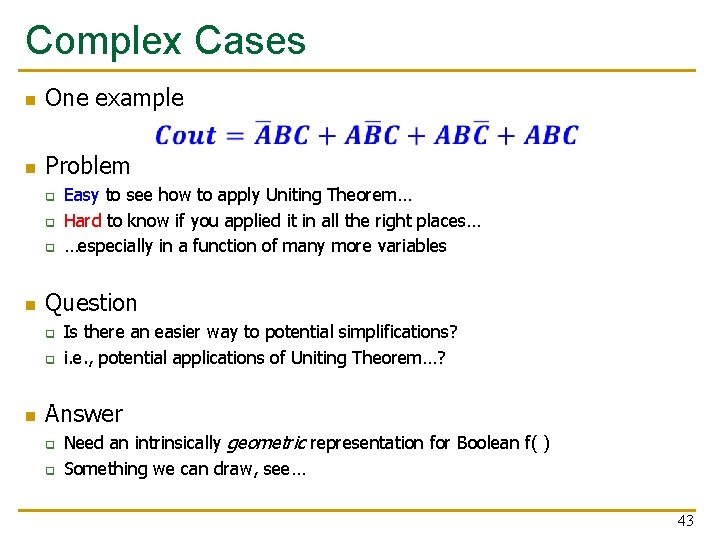

Complex Cases One example n Problem n q q q n Question q q n Easy to see how to apply Uniting Theorem… Hard to know if you applied it in all the right places… …especially in a function of many more variables Is there an easier way to potential simplifications? i. e. , potential applications of Uniting Theorem…? Answer q q Need an intrinsically geometric representation for Boolean f( ) Something we can draw, see… 43

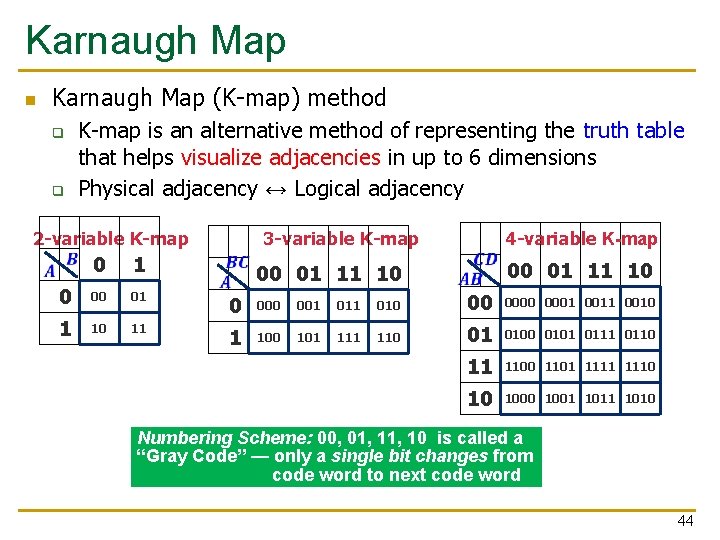

Karnaugh Map n Karnaugh Map (K-map) method q q K-map is an alternative method of representing the truth table that helps visualize adjacencies in up to 6 dimensions Physical adjacency ↔ Logical adjacency 2 -variable K-map 0 1 0 00 01 1 10 11 3 -variable K-map 00 01 11 10 4 -variable K-map 00 01 11 10 0 001 010 00 0001 0010 1 100 101 110 01 0100 0101 0110 11 1100 1101 1110 10 1001 1010 Numbering Scheme: 00, 01, 10 is called a “Gray Code” — only a single bit changes from code word to next code word 44

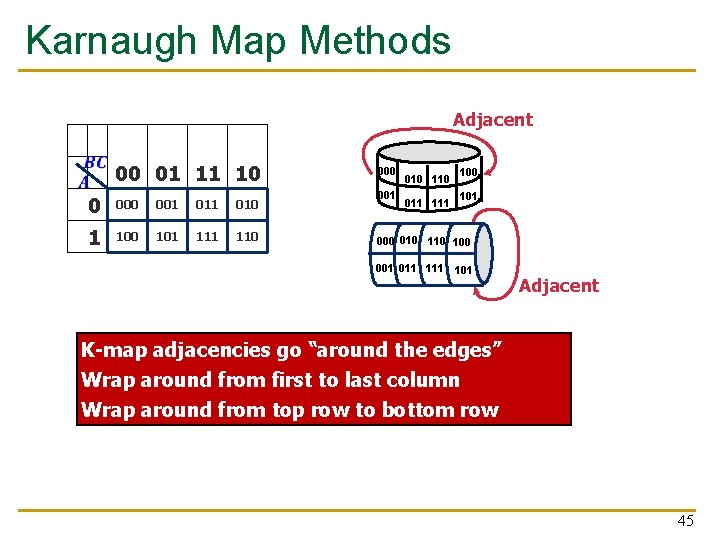

Karnaugh Map Methods Adjacent 00 01 11 10 0 001 010 1 100 101 110 001 010 110 011 100 101 000 010 100 001 011 101 Adjacent K-map adjacencies go “around the edges” Wrap around from first to last column Wrap around from top row to bottom row 45

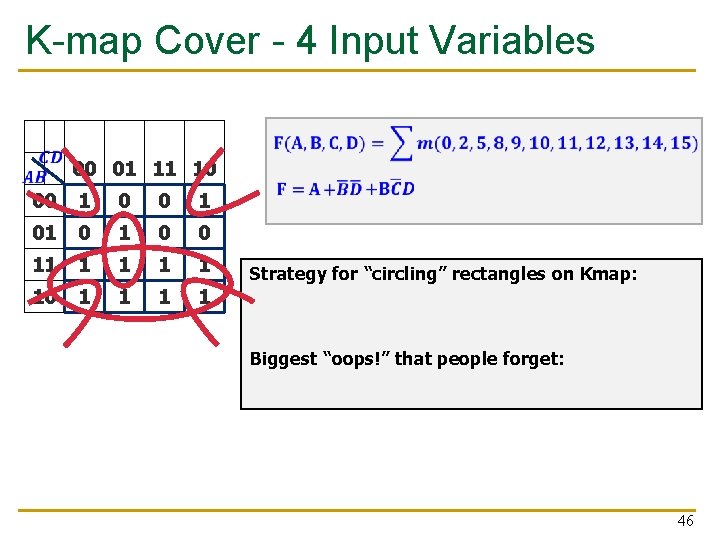

K-map Cover - 4 Input Variables 00 01 11 10 00 1 01 0 0 11 1 1 10 1 1 Strategy for “circling” rectangles on Kmap: As big as possible Biggest “oops!” that people forget: Wrap-arounds 46

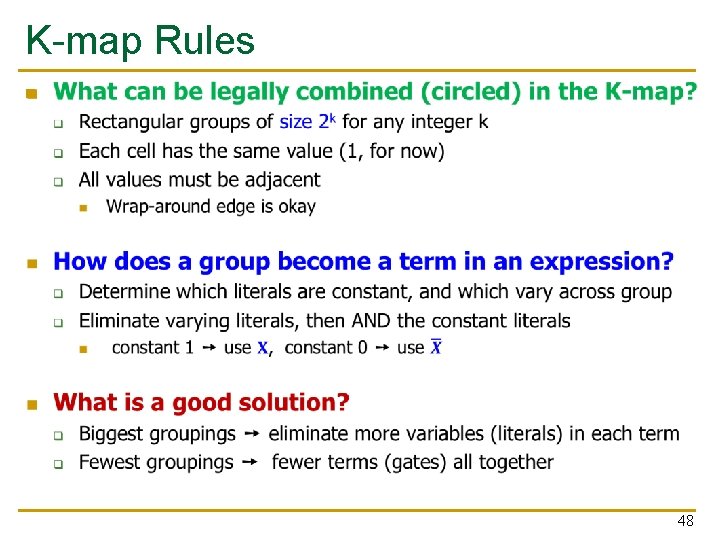

K-map Rules n 48

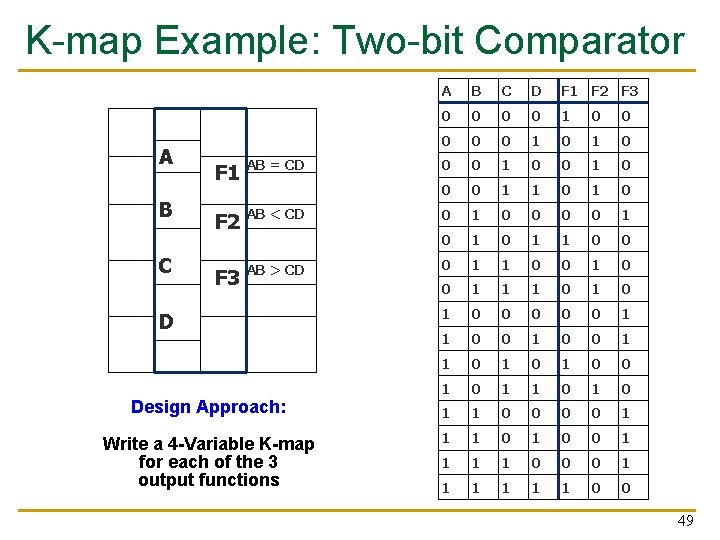

K-map Example: Two-bit Comparator A B C F 1 AB = CD F 2 AB < CD F 3 AB > CD D Design Approach: Write a 4 -Variable K-map for each of the 3 output functions A B C D F 1 F 2 F 3 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 49

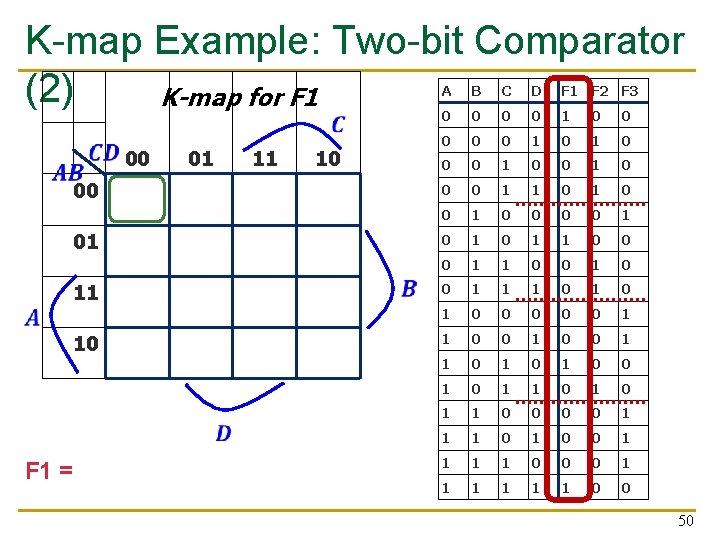

K-map Example: Two-bit Comparator (2) K-map for F 1 00 01 11 10 1 F 1 = A'B'C'D' + A'BC'D + ABCD + AB'CD' A B C D F 1 F 2 F 3 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 50

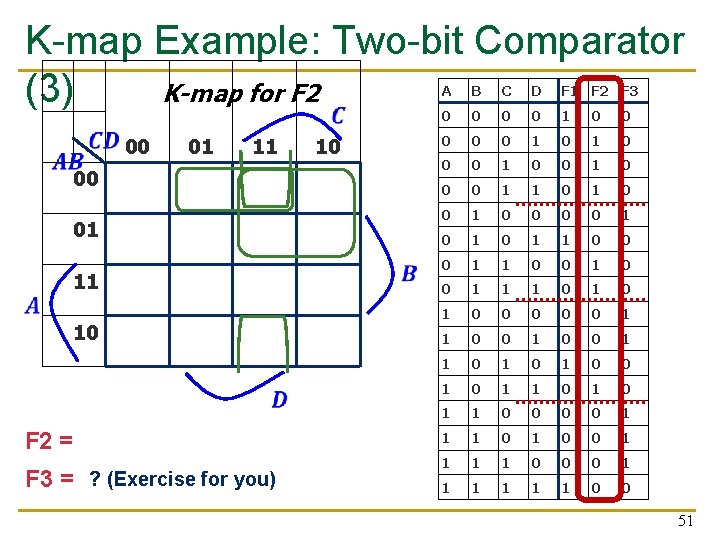

K-map Example: Two-bit Comparator K-map for F 2 (3) A B C D F 1 F 2 F 3 0 0 1 0 0 01 11 10 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 F 2 = A'C + A'B'D + B'CD 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 00 01 00 1 11 10 1 F 3 = ? (Exercise for you) 51

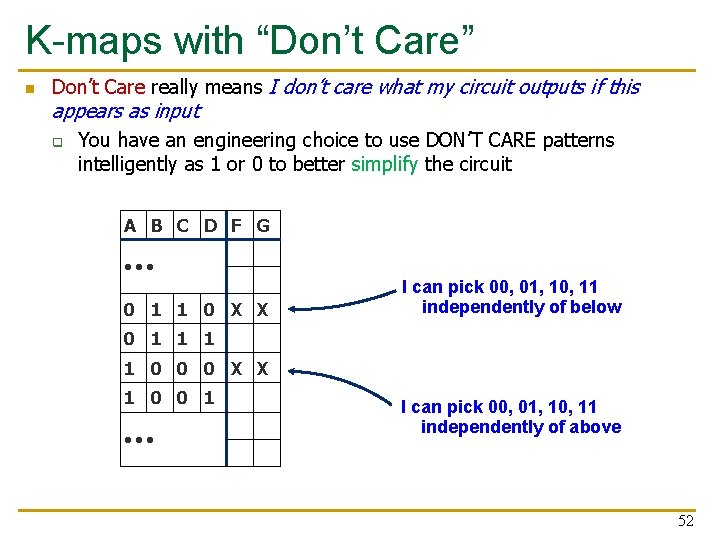

K-maps with “Don’t Care” n Don’t Care really means I don’t care what my circuit outputs if this appears as input q You have an engineering choice to use DON’T CARE patterns intelligently as 1 or 0 to better simplify the circuit A B C D F G • • • 0 1 1 0 X X I can pick 00, 01, 10, 11 independently of below 0 1 1 0 0 0 X X 1 0 0 1 • • • I can pick 00, 01, 10, 11 independently of above 52

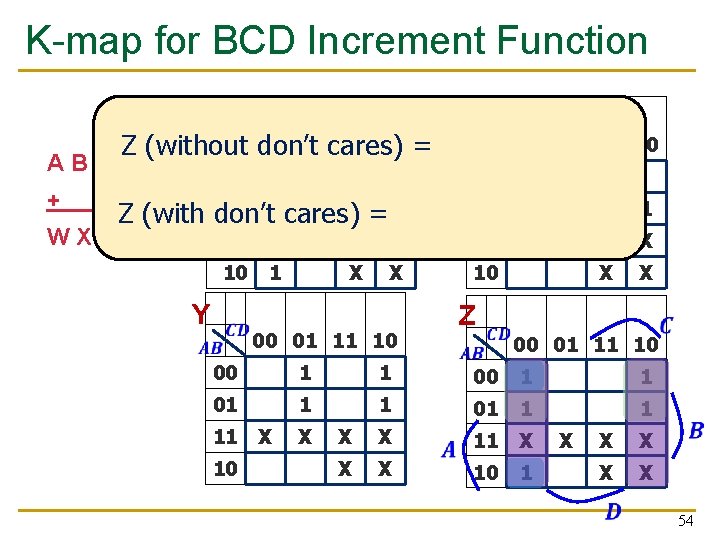

Example: BCD Increment Function n BCD (Binary Coded Decimal) digits q q Encode decimal digits 0 - 9 with bit patterns 00002 — 10012 When incremented, the decimal sequence is 0, 1, …, 8, 9, 0, 1 A 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 B 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 C 0 0 1 1 D 0 1 0 1 W 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 X X X X 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 X X X Y 0 1 1 0 0 0 X X X Z 1 0 1 0 1 0 X X X These input patterns should never be encountered in practice (hey -- it’s a BCD number!) So, associated output values are “Don’t Cares” 53

K-map for BCD Increment Function W X 00 01 11 10 00 B'C'D’ 01 11 Z (without don’t cares) = A'D' + ABCD + 00 1 00 01 1 Z (with don’t cares) = D' WXYZ Y 11 X 10 01 1 10 X X 1 X 1 11 00 11 1 X Z 00 01 11 10 1 01 X 10 1 X X 00 01 11 10 00 1 1 1 01 1 1 X X 11 X X X 10 1 X X X 54

K-map Summary n Karnaugh maps as a formal systematic approach for logic simplification n 2 -, 3 -, 4 -variable K-maps n K-maps with “Don’t Care” outputs 55

Hardware Description Languages & Verilog (Combinational Logic) 56

Agenda n Implementing Combinational Logic q q q Hardware Description Languages Hardware Design Methodologies Verilog 57

2017: Intel Kaby Lake • 64 -bit processor • 4 cores, 8 threads • 14 -19 stage pipeline • 3. 9 GHz clock • 1. 75 B transistors • In ~47 years, https: //en. wikichip. org/wiki/intel/microarchitectures/kaby_lake about 1, 000 fold growth in transistor count and performance! 59

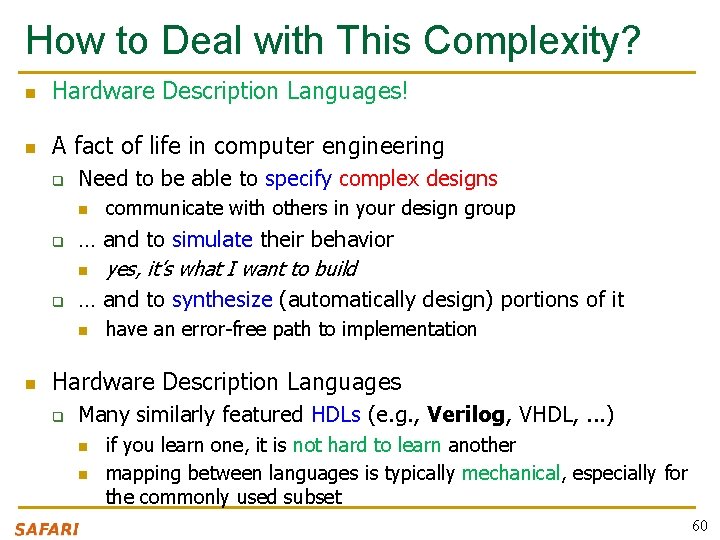

How to Deal with This Complexity? n Hardware Description Languages! n A fact of life in computer engineering q Need to be able to specify complex designs n q q … and to simulate their behavior n yes, it’s what I want to build … and to synthesize (automatically design) portions of it n n communicate with others in your design group have an error-free path to implementation Hardware Description Languages q Many similarly featured HDLs (e. g. , Verilog, VHDL, . . . ) n n if you learn one, it is not hard to learn another mapping between languages is typically mechanical, especially for the commonly used subset 60

Hardware Description Languages n Two well-known hardware description languages n Verilog q q q n VHDL (VHSIC Hardware Description Language) q q q n Developed in 1984 by Gateway Design Automation Became an IEEE standard (1364) in 1995 More popular in US Developed in 1981 by the Department of Defense Became an IEEE standard (1076) in 1987 More popular in Europe In this course we will use Verilog 61

Hardware Design Using Verilog 62

Hierarchical Design n Design hierarchy of modules is built using instantiation q q q n Predefined “primitive” gates (AND, OR, …) Simple modules are built by instantiating these gates (components like MUXes) Other modules are built by instantiating simple components, … Hierarchy controls complexity q n https: //techreport. com/review/21987/intel -core-i 7 -3960 x-processor Analogous to the use of function abstraction in SW Complexity is a BIG deal q In real world how big is size of one “blob” of random logic that we would describe as an HDL, then synthesize to gates? How many? 63

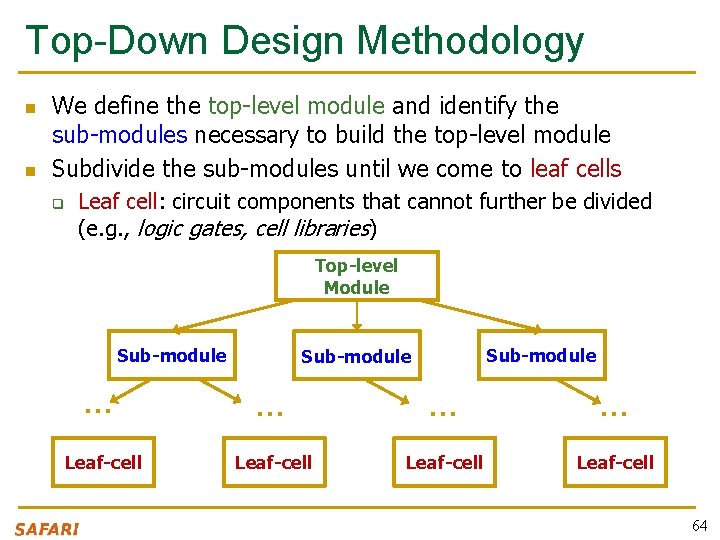

Top-Down Design Methodology n n We define the top-level module and identify the sub-modules necessary to build the top-level module Subdivide the sub-modules until we come to leaf cells q Leaf cell: circuit components that cannot further be divided (e. g. , logic gates, cell libraries) Top-level Module Sub-module … … Leaf-cell 64

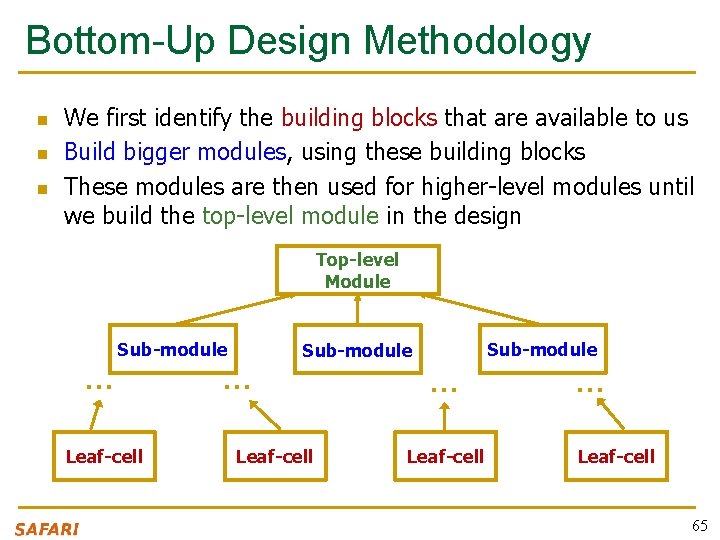

Bottom-Up Design Methodology n n n We first identify the building blocks that are available to us Build bigger modules, using these building blocks These modules are then used for higher-level modules until we build the top-level module in the design Top-level Module … Sub-module Leaf-cell Sub-module … Leaf-cell 65

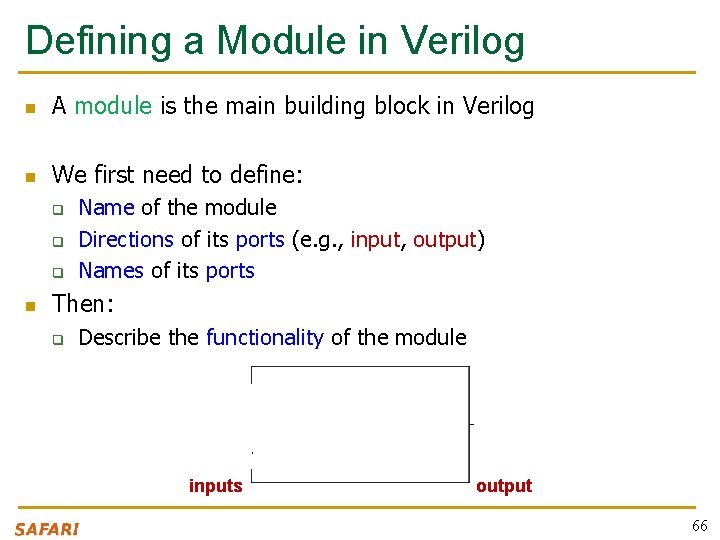

Defining a Module in Verilog n A module is the main building block in Verilog n We first need to define: q q q n Name of the module Directions of its ports (e. g. , input, output) Names of its ports Then: q Describe the functionality of the module example inputs output 66

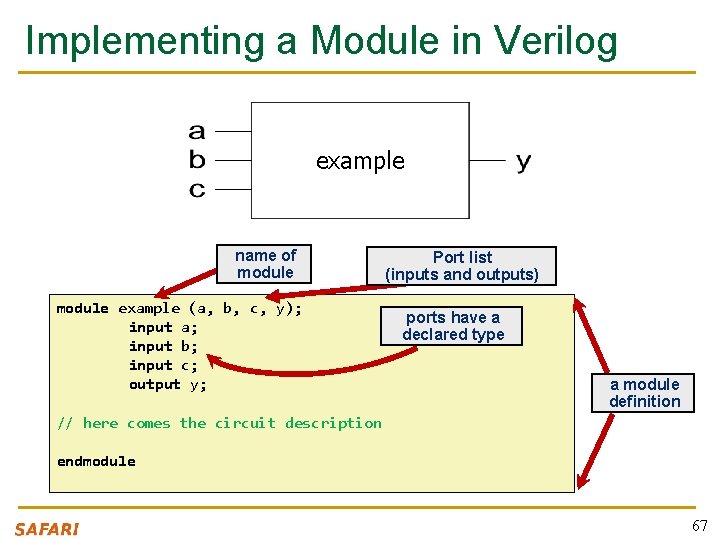

Implementing a Module in Verilog example name of module example (a, b, c, y); input a; input b; input c; output y; Port list (inputs and outputs) ports have a declared type a module definition // here comes the circuit description endmodule 67

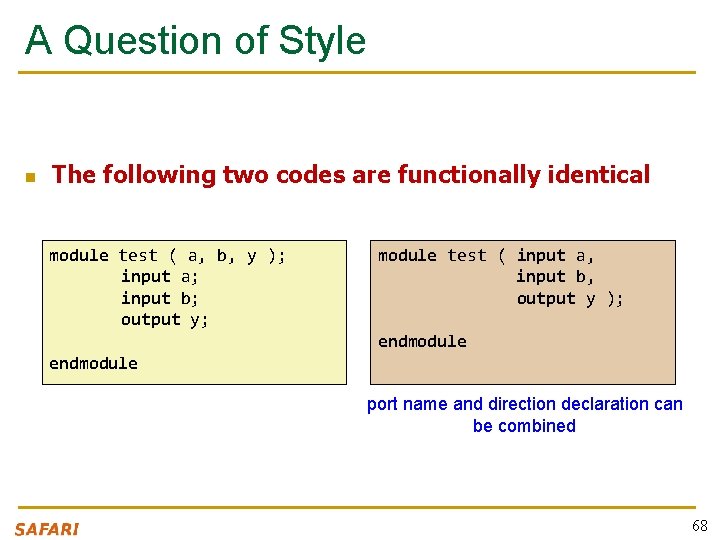

A Question of Style n The following two codes are functionally identical module test ( a, b, y ); input a; input b; output y; module test ( input a, input b, output y ); endmodule port name and direction declaration can be combined 68

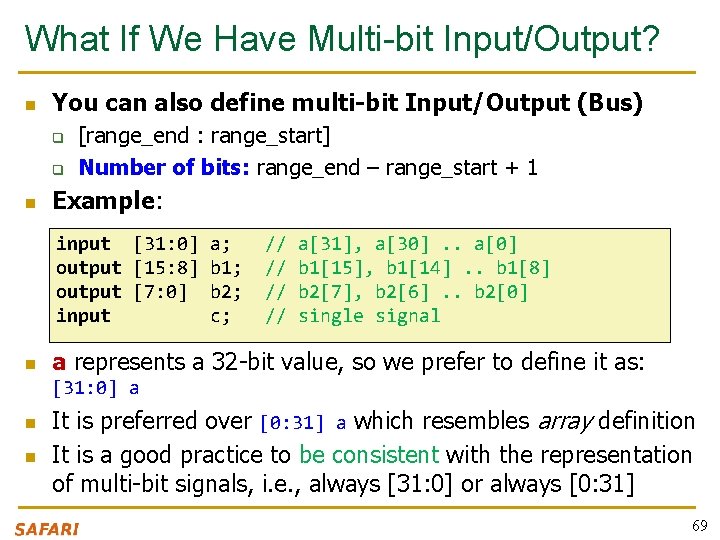

What If We Have Multi-bit Input/Output? n You can also define multi-bit Input/Output (Bus) q q n [range_end : range_start] Number of bits: range_end – range_start + 1 Example: input [31: 0] a; output [15: 8] b 1; output [7: 0] b 2; input c; n // // a[31], a[30]. . a[0] b 1[15], b 1[14]. . b 1[8] b 2[7], b 2[6]. . b 2[0] single signal a represents a 32 -bit value, so we prefer to define it as: [31: 0] a n n It is preferred over [0: 31] a which resembles array definition It is a good practice to be consistent with the representation of multi-bit signals, i. e. , always [31: 0] or always [0: 31] 69

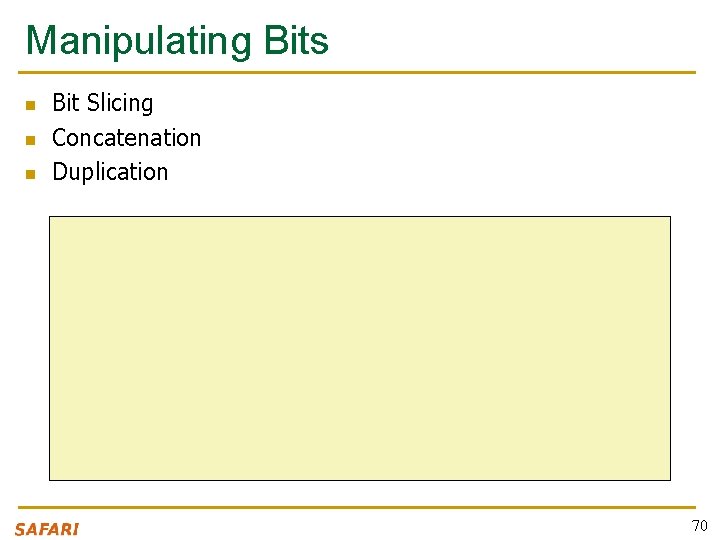

Manipulating Bits n n n Bit Slicing Concatenation Duplication // You can assign partial buses wire [15: 0] longbus; wire [7: 0] shortbus; assign shortbus = longbus[12: 5]; // Concatenating is by {} assign y = {a[2], a[1], a[0]}; // Possible to define multiple copies assign x = {a[0], a[0]} assign y = { 4{a[0]} } 70

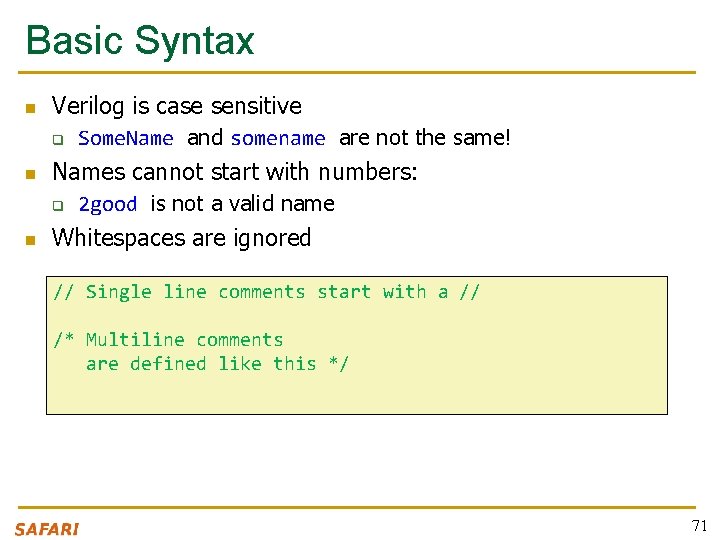

Basic Syntax n Verilog is case sensitive q n Names cannot start with numbers: q n Some. Name and somename are not the same! 2 good is not a valid name Whitespaces are ignored // Single line comments start with a // /* Multiline comments are defined like this */ 71

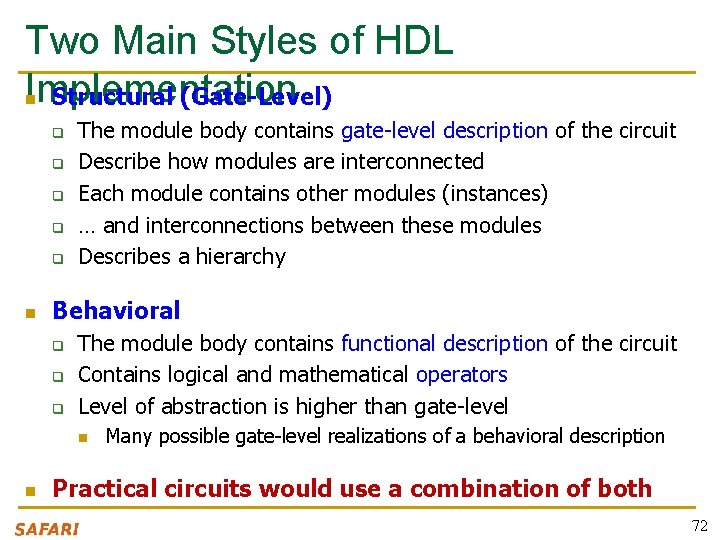

Two Main Styles of HDL Implementation n Structural (Gate-Level) q q q n The module body contains gate-level description of the circuit Describe how modules are interconnected Each module contains other modules (instances) … and interconnections between these modules Describes a hierarchy Behavioral q q q The module body contains functional description of the circuit Contains logical and mathematical operators Level of abstraction is higher than gate-level n n Many possible gate-level realizations of a behavioral description Practical circuits would use a combination of both 72

Structural HDL 73

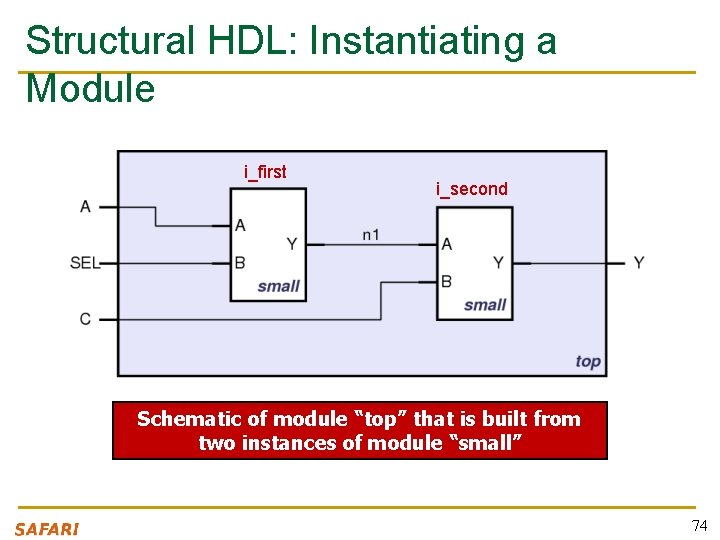

Structural HDL: Instantiating a Module i_first i_second Schematic of module “top” that is built from two instances of module “small” 74

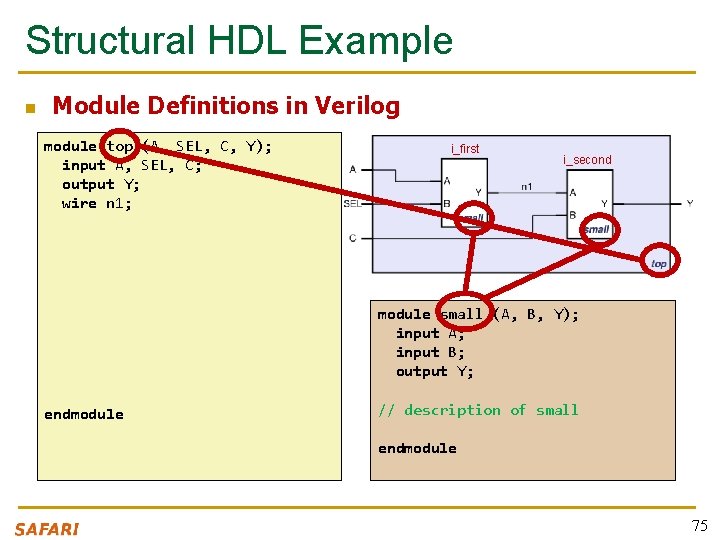

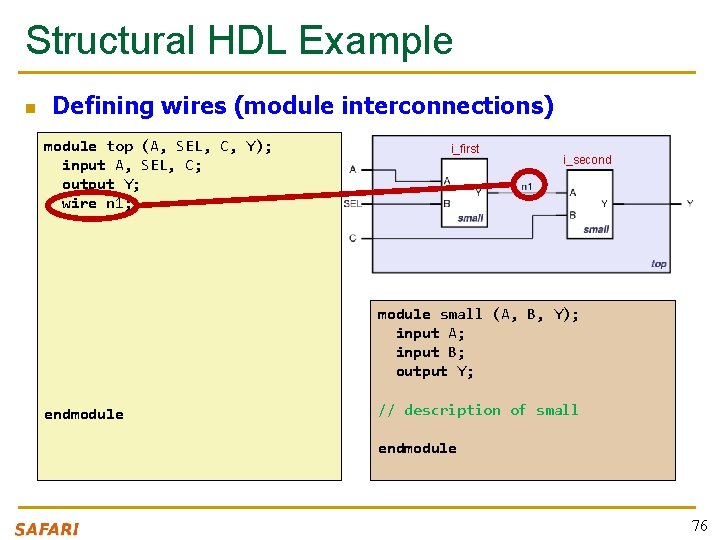

Structural HDL Example n Module Definitions in Verilog module top (A, SEL, C, Y); input A, SEL, C; output Y; wire n 1; i_first i_second module small (A, B, Y); input A; input B; output Y; endmodule // description of small endmodule 75

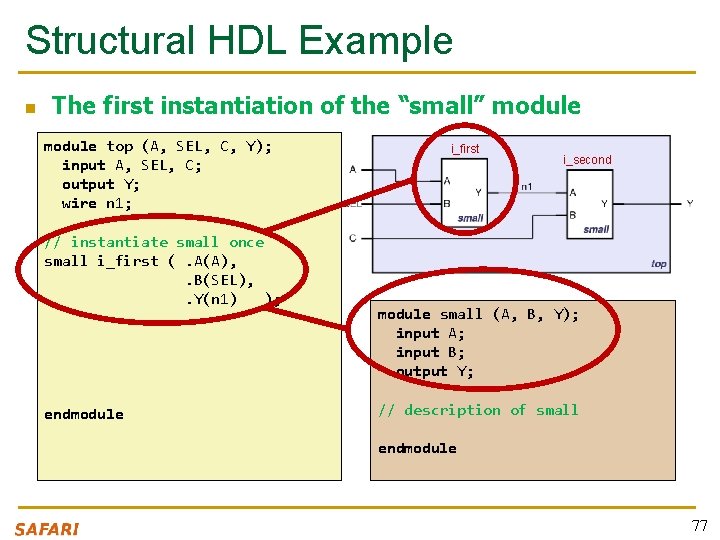

Structural HDL Example n Defining wires (module interconnections) module top (A, SEL, C, Y); input A, SEL, C; output Y; wire n 1; i_first i_second module small (A, B, Y); input A; input B; output Y; endmodule // description of small endmodule 76

Structural HDL Example n The first instantiation of the “small” module top (A, SEL, C, Y); input A, SEL, C; output Y; wire n 1; // instantiate small once small i_first (. A(A), . B(SEL), . Y(n 1) ); endmodule i_first i_second module small (A, B, Y); input A; input B; output Y; // description of small endmodule 77

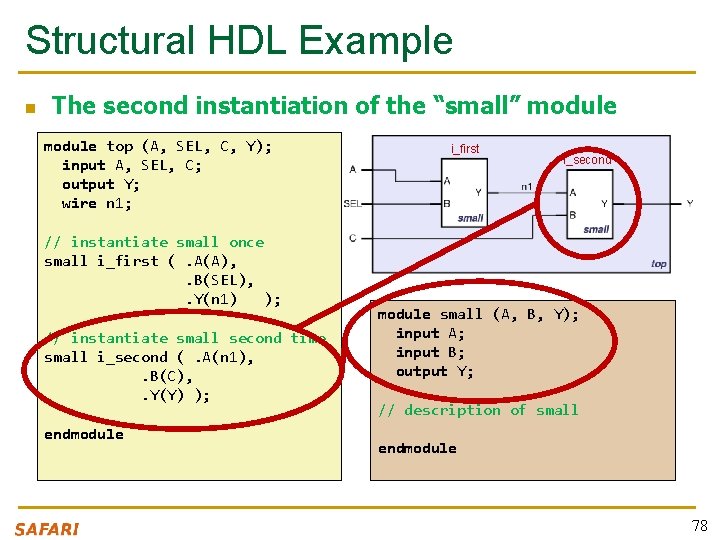

Structural HDL Example n The second instantiation of the “small” module top (A, SEL, C, Y); input A, SEL, C; output Y; wire n 1; // instantiate small once small i_first (. A(A), . B(SEL), . Y(n 1) ); // instantiate small second time small i_second (. A(n 1), . B(C), . Y(Y) ); endmodule i_first i_second module small (A, B, Y); input A; input B; output Y; // description of small endmodule 78

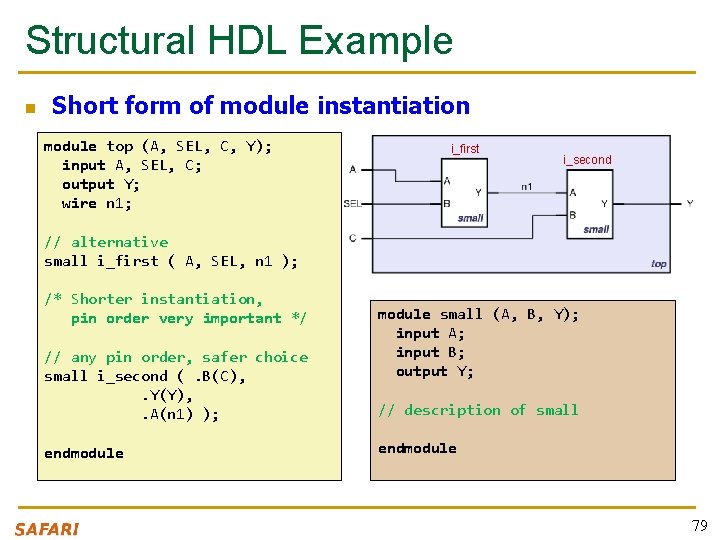

Structural HDL Example n Short form of module instantiation module top (A, SEL, C, Y); input A, SEL, C; output Y; wire n 1; i_first i_second // alternative small i_first ( A, SEL, n 1 ); /* Shorter instantiation, pin order very important */ // any pin order, safer choice small i_second (. B(C), . Y(Y), . A(n 1) ); endmodule small (A, B, Y); input A; input B; output Y; // description of small endmodule 79

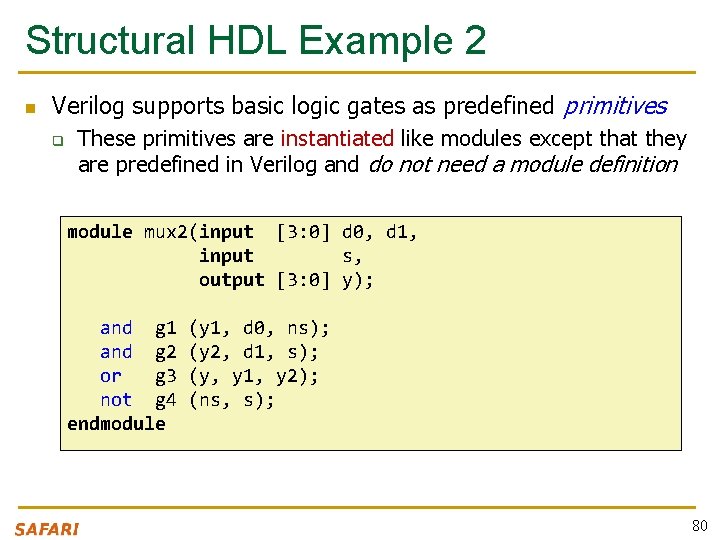

Structural HDL Example 2 n Verilog supports basic logic gates as predefined primitives q These primitives are instantiated like modules except that they are predefined in Verilog and do not need a module definition module mux 2(input [3: 0] d 0, d 1, input s, output [3: 0] y); and g 1 and g 2 or g 3 not g 4 endmodule (y 1, d 0, ns); (y 2, d 1, s); (y, y 1, y 2); (ns, s); 80

Behavioral HDL 81

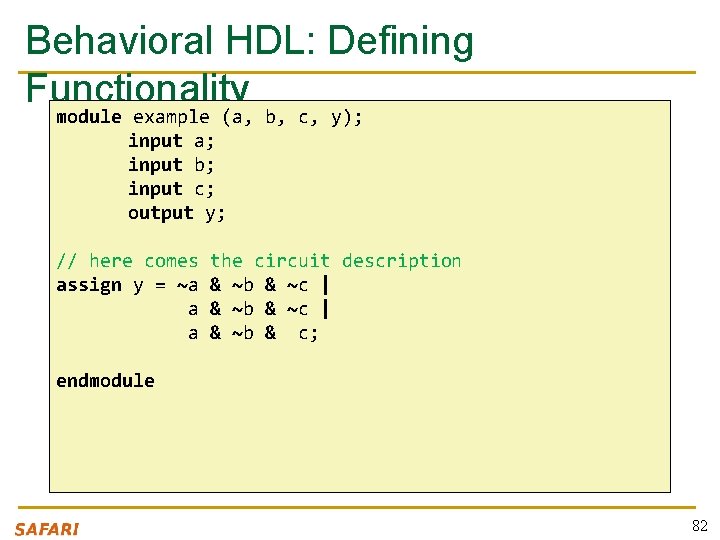

Behavioral HDL: Defining Functionality module example (a, b, c, y); input a; input b; input c; output y; // here comes assign y = ~a a a the circuit description & ~b & ~c | & ~b & c; endmodule 82

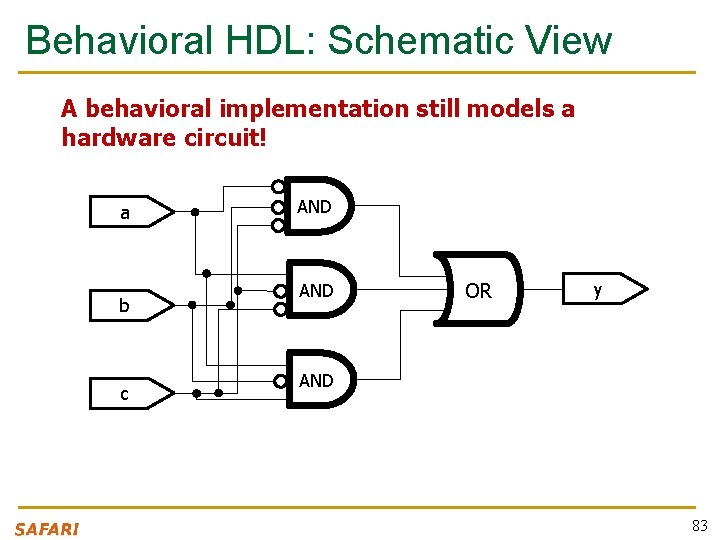

Behavioral HDL: Schematic View A behavioral implementation still models a hardware circuit! a b c AND OR y AND 83

![Bitwise Operators in Behavioral Verilog module gates(input [3: 0] a, b, output [3: 0] Bitwise Operators in Behavioral Verilog module gates(input [3: 0] a, b, output [3: 0]](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/28aa08800e5c2653690ff543d8fa8100/image-82.jpg)

Bitwise Operators in Behavioral Verilog module gates(input [3: 0] a, b, output [3: 0] y 1, y 2, y 3, y 4, y 5); /* Five different two-input logic gates acting on 4 bit buses */ assign assign y 1 y 2 y 3 y 4 y 5 = = = a & a | a ^ ~(a b; b; b; & b); | b); // // // AND OR XOR NAND NOR endmodule 84

Bitwise Operators: Schematic View 85

![Reduction Operators in Behavioral Verilog module and 8(input [7: 0] a, output y); assign Reduction Operators in Behavioral Verilog module and 8(input [7: 0] a, output y); assign](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/28aa08800e5c2653690ff543d8fa8100/image-84.jpg)

Reduction Operators in Behavioral Verilog module and 8(input [7: 0] a, output y); assign y = &a; // &a is much easier to write than // assign y = a[7] & a[6] & a[5] & a[4] & // a[3] & a[2] & a[1] & a[0]; endmodule 86

![Reduction Operators: Schematic View [0] [1] [2] a[7: 0] [3] [4] AND y [5] Reduction Operators: Schematic View [0] [1] [2] a[7: 0] [3] [4] AND y [5]](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/28aa08800e5c2653690ff543d8fa8100/image-85.jpg)

Reduction Operators: Schematic View [0] [1] [2] a[7: 0] [3] [4] AND y [5] [6] [7] 8 -input AND gate 87

![Conditional Assignment in Behavioral Verilog module mux 2(input [3: 0] d 0, d 1, Conditional Assignment in Behavioral Verilog module mux 2(input [3: 0] d 0, d 1,](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/28aa08800e5c2653690ff543d8fa8100/image-86.jpg)

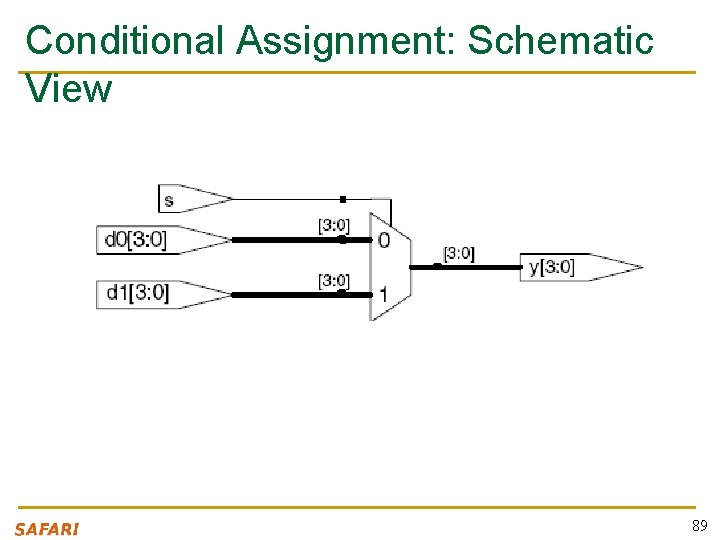

Conditional Assignment in Behavioral Verilog module mux 2(input [3: 0] d 0, d 1, input s, output [3: 0] y); assign y = s ? d 1 : d 0; // if (s) then y=d 1 else y=d 0; endmodule n ? : is also called a ternary operator as it operates on three inputs: q q q s d 1 d 0 88

Conditional Assignment: Schematic View 89

![More Complex Conditional Assignments module mux 4(input [3: 0] d 0, d 1, d More Complex Conditional Assignments module mux 4(input [3: 0] d 0, d 1, d](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/28aa08800e5c2653690ff543d8fa8100/image-88.jpg)

More Complex Conditional Assignments module mux 4(input [3: 0] d 0, d 1, d 2, d 3 input [1: 0] s, output [3: 0] y); assign y = s[1] ? ( : ( // if (s 1) then // if (s 0) then // else // if (s 0) then s[0] ? d 3 : d 2) s[0] ? d 1 : d 0); y=d 3 else y=d 2 y=d 1 else y=d 0 endmodule 90

![Even More Complex Conditional Assignments module mux 4(input [3: 0] d 0, d 1, Even More Complex Conditional Assignments module mux 4(input [3: 0] d 0, d 1,](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/28aa08800e5c2653690ff543d8fa8100/image-89.jpg)

Even More Complex Conditional Assignments module mux 4(input [3: 0] d 0, d 1, d 2, d 3 input [1: 0] s, output [3: 0] y); // // assign y = (s == 2’b 11) ? d 3 : (s == 2’b 10) ? d 2 : (s == 2’b 01) ? d 1 : d 0; if (s = “ 11” ) then y= d 3 else if (s = “ 10” ) then y= d 2 else if (s = “ 01” ) then y= d 1 else y= d 0 endmodule 91

Precedence of Operations in Verilog Highest Lowest 92

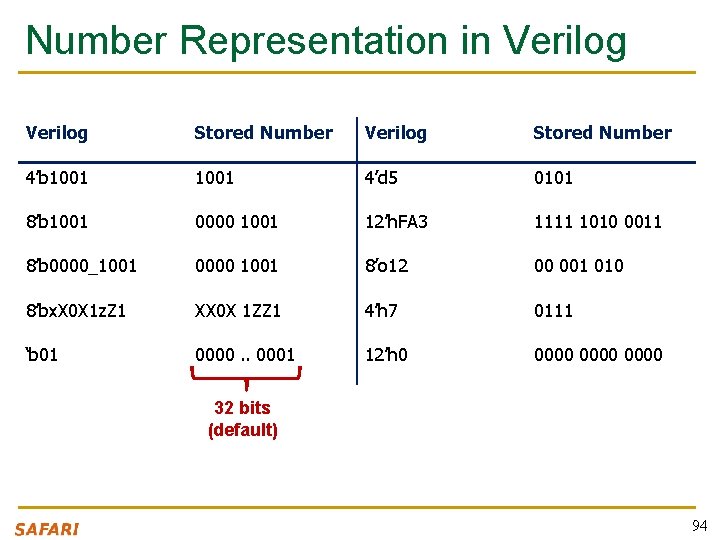

How to Express Numbers ? N’Bxx 8’b 0000_0001 n (N) Number of bits q n (B) Base q n Expresses how many bits will be used to store the value Can be b (binary), h (hexadecimal), d (decimal), o (octal) (xx) Number q q q The value expressed in base Apart from numbers, it can also have X and Z as values Underscore _ can be used to improve readability 93

Number Representation in Verilog Stored Number 4’b 1001 4’d 5 0101 8’b 1001 0000 1001 12’h. FA 3 1111 1010 0011 8’b 0000_1001 0000 1001 8’o 12 00 001 010 8’bx. X 0 X 1 z. Z 1 XX 0 X 1 ZZ 1 4’h 7 0111 ‘b 01 0000. . 0001 12’h 0 0000 32 bits (default) 94

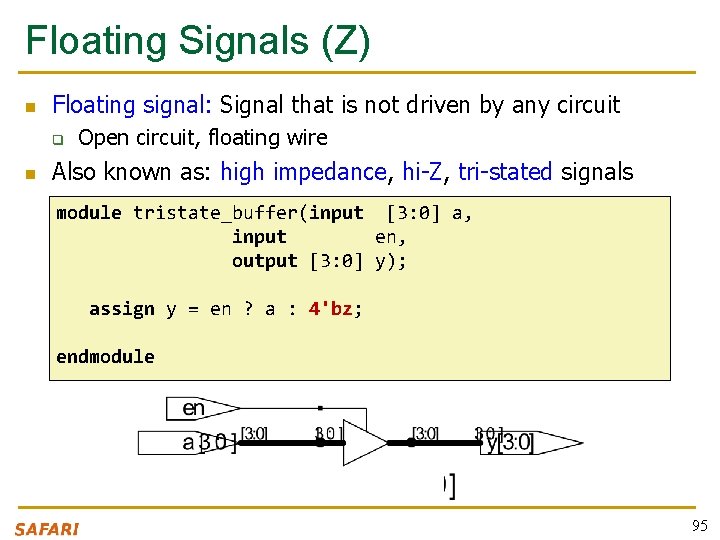

Floating Signals (Z) n Floating signal: Signal that is not driven by any circuit q n Open circuit, floating wire Also known as: high impedance, hi-Z, tri-stated signals module tristate_buffer(input [3: 0] a, input en, output [3: 0] y); assign y = en ? a : 4'bz; endmodule 95

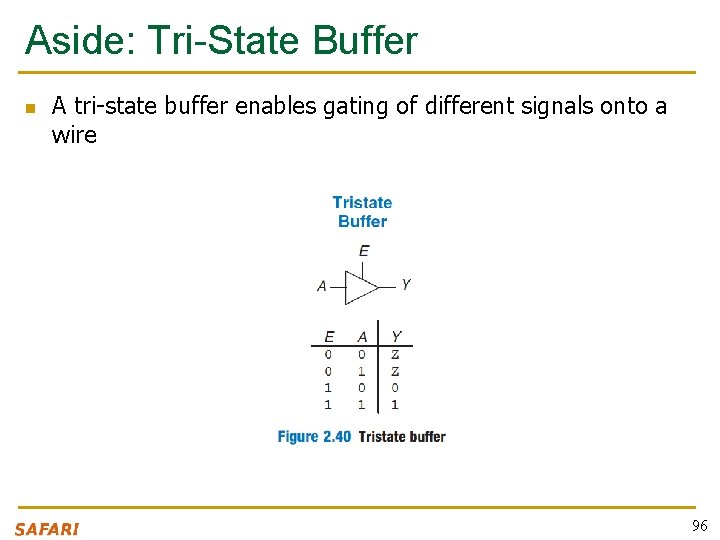

Aside: Tri-State Buffer n A tri-state buffer enables gating of different signals onto a wire 96

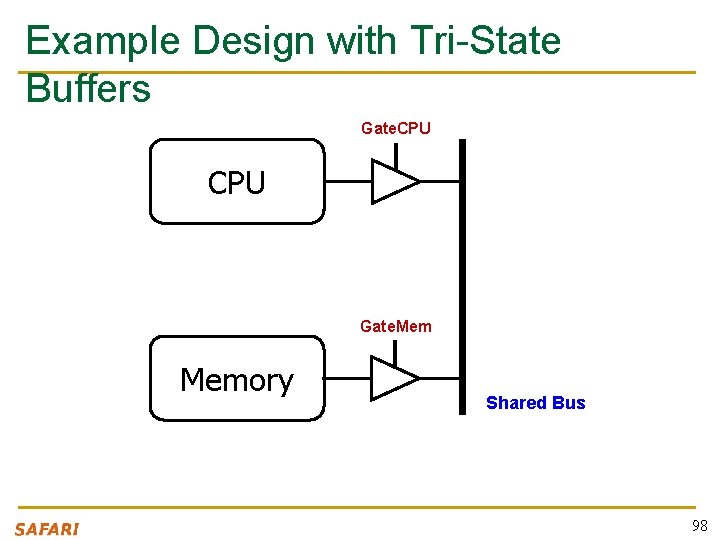

Example: Use of Tri-State Buffers n Imagine a wire connecting the CPU and memory q q At any time only the CPU or the memory can place a value on the wire, both not both You can have two tri-state buffers: one driven by CPU, the other memory; and ensure at most one is enabled at any time 97

Example Design with Tri-State Buffers Gate. CPU Gate. Memory Shared Bus 98

Truth Table for AND with Z and X AND B A 0 1 Z X 0 0 0 1 X X Z 0 X X X 99

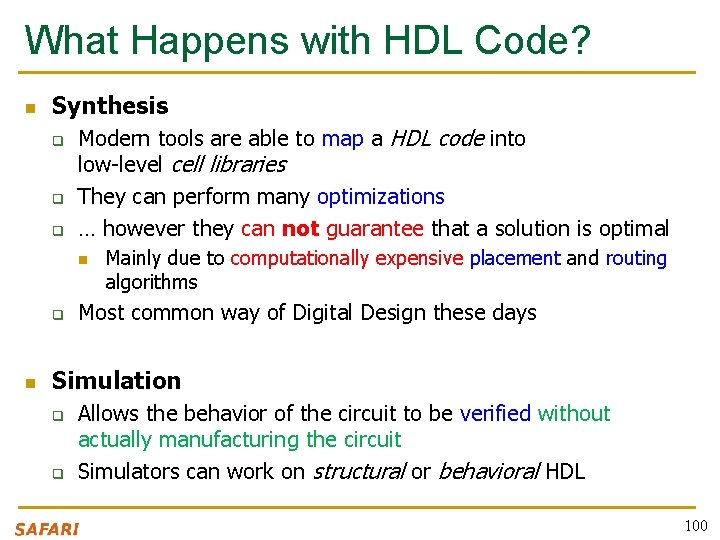

What Happens with HDL Code? n Synthesis q q q Modern tools are able to map a HDL code into low-level cell libraries They can perform many optimizations … however they can not guarantee that a solution is optimal n q n Mainly due to computationally expensive placement and routing algorithms Most common way of Digital Design these days Simulation q q Allows the behavior of the circuit to be verified without actually manufacturing the circuit Simulators can work on structural or behavioral HDL 100

We did not cover the following. They are for your preparation. 101

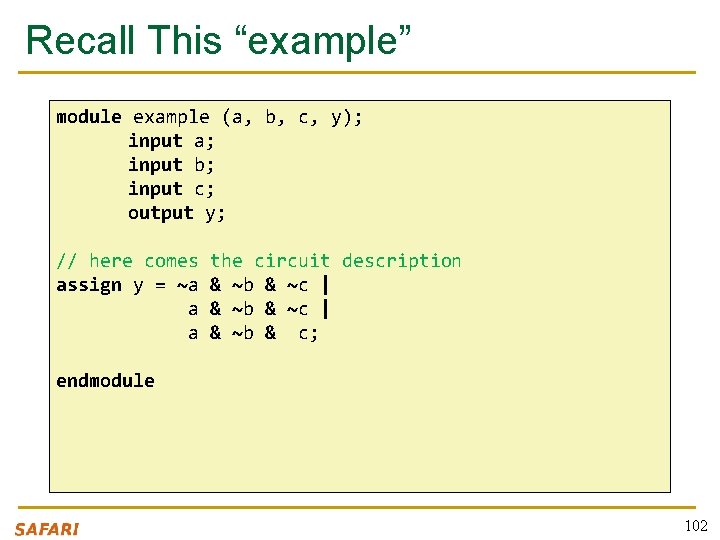

Recall This “example” module example (a, b, c, y); input a; input b; input c; output y; // here comes assign y = ~a a a the circuit description & ~b & ~c | & ~b & c; endmodule 102

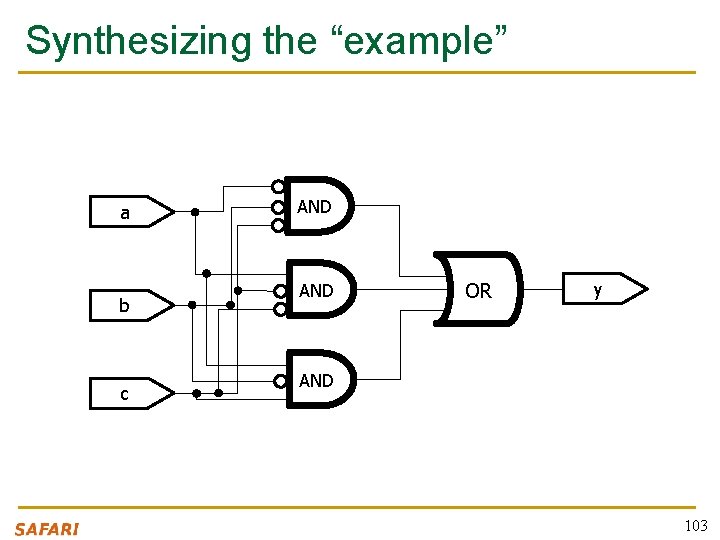

Synthesizing the “example” a b c AND OR y AND 103

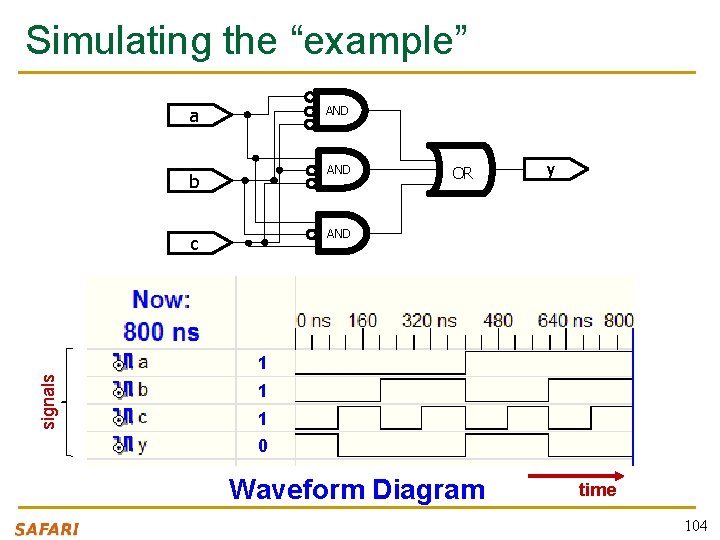

Simulating the “example” AND a AND b OR y AND c signals 1 1 1 0 Waveform Diagram time 104

What We Have Seen So Far n Describing structural hierarchy with Verilog q Instantiate modules in an other module n Describing functionality using behavioral modeling n Writing simple logic equations q n We can write AND, OR, XOR, … Multiplexer functionality q If … then … else n We can describe constants n But there is more. . . 105

More Verilog Examples n n We can write Verilog code in many different ways Let’s see how we can express the same functionality by developing Verilog code q At low-level n n q Poor readability More optimization opportunities At a higher-level of abstraction n n Better readability Limited optimization 106

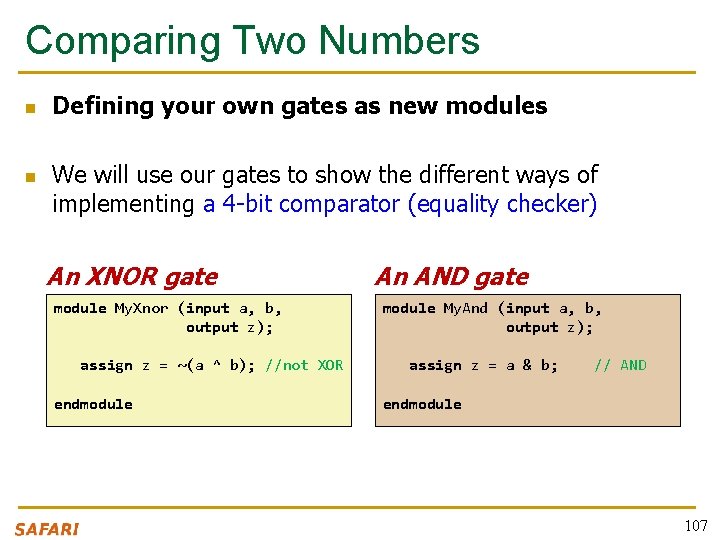

Comparing Two Numbers n n Defining your own gates as new modules We will use our gates to show the different ways of implementing a 4 -bit comparator (equality checker) An XNOR gate module My. Xnor (input a, b, output z); assign z = ~(a ^ b); //not XOR endmodule An AND gate module My. And (input a, b, output z); assign z = a & b; // AND endmodule 107

Gate-Level Implementation module compare (input a 0, a 1, a 2, a 3, b 0, b 1, b 2, b 3, output eq); wire c 0, c 1, c 2, c 3, c 01, c 23; My. Xnor i 0 (. A(a 0), . B(b 0), . Z(c 0) ); // XNOR My. Xnor i 1 (. A(a 1), . B(b 1), . Z(c 1) ); // XNOR My. Xnor i 2 (. A(a 2), . B(b 2), . Z(c 2) ); // XNOR My. Xnor i 3 (. A(a 3), . B(b 3), . Z(c 3) ); // XNOR My. And haha (. A(c 0), . B(c 1), . Z(c 01) ); // AND My. And hoho (. A(c 2), . B(c 3), . Z(c 23) ); // AND My. And bubu (. A(c 01), . B(c 23), . Z(eq) ); // AND endmodule 108

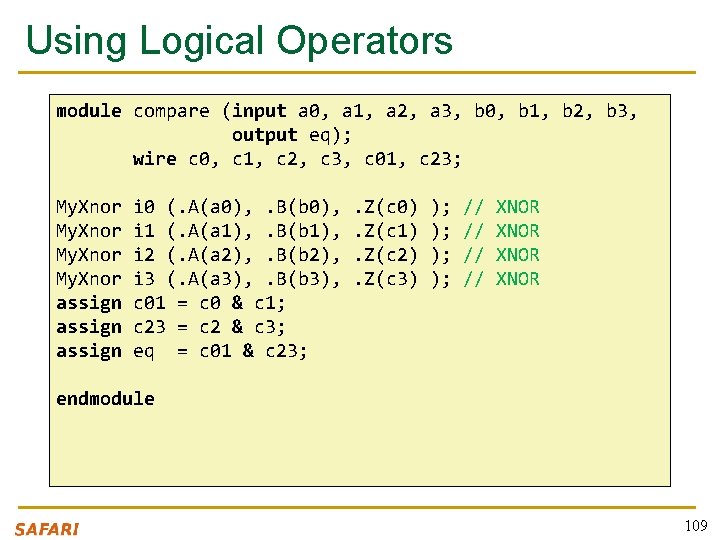

Using Logical Operators module compare (input a 0, a 1, a 2, a 3, b 0, b 1, b 2, b 3, output eq); wire c 0, c 1, c 2, c 3, c 01, c 23; My. Xnor assign i 0 (. A(a 0), . B(b 0), i 1 (. A(a 1), . B(b 1), i 2 (. A(a 2), . B(b 2), i 3 (. A(a 3), . B(b 3), c 01 = c 0 & c 1; c 23 = c 2 & c 3; eq = c 01 & c 23; . Z(c 0). Z(c 1). Z(c 2). Z(c 3) ); ); // // XNOR endmodule 109

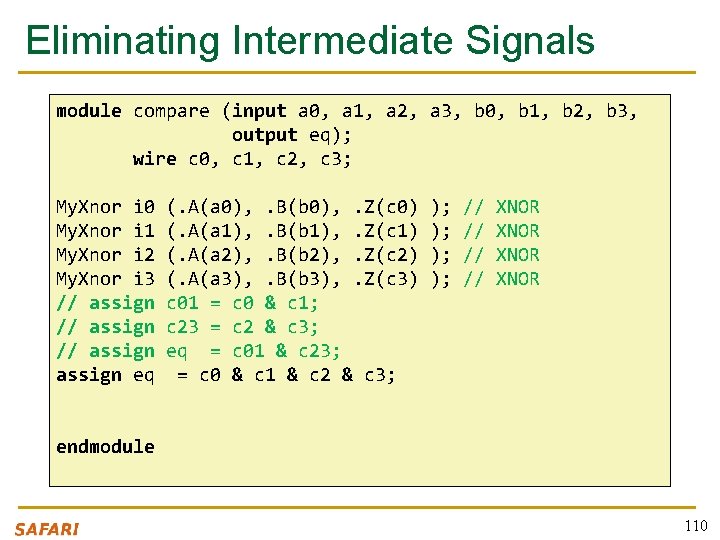

Eliminating Intermediate Signals module compare (input a 0, a 1, a 2, a 3, b 0, b 1, b 2, b 3, output eq); wire c 0, c 1, c 2, c 3; My. Xnor i 0 My. Xnor i 1 My. Xnor i 2 My. Xnor i 3 // assign eq (. A(a 0), . B(b 0), . Z(c 0) (. A(a 1), . B(b 1), . Z(c 1) (. A(a 2), . B(b 2), . Z(c 2) (. A(a 3), . B(b 3), . Z(c 3) c 01 = c 0 & c 1; c 23 = c 2 & c 3; eq = c 01 & c 23; = c 0 & c 1 & c 2 & c 3; ); ); // // XNOR endmodule 110

![Multi-Bit Signals (Bus) module compare (input [3: 0] a, input [3: 0] b, output Multi-Bit Signals (Bus) module compare (input [3: 0] a, input [3: 0] b, output](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/28aa08800e5c2653690ff543d8fa8100/image-109.jpg)

Multi-Bit Signals (Bus) module compare (input [3: 0] a, input [3: 0] b, output eq); wire [3: 0] c; // bus definition My. Xnor i 0 i 1 i 2 i 3 assign eq (. A(a[0]), (. A(a[1]), (. A(a[2]), (. A(a[3]), . B(b[0]), . B(b[1]), . B(b[2]), . B(b[3]), . Z(c[0]). Z(c[1]). Z(c[2]). Z(c[3]) ); ); // // XNOR = &c; // short format endmodule 111

![Bitwise Operations module compare (input [3: 0] a, input [3: 0] b, output eq); Bitwise Operations module compare (input [3: 0] a, input [3: 0] b, output eq);](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/28aa08800e5c2653690ff543d8fa8100/image-110.jpg)

Bitwise Operations module compare (input [3: 0] a, input [3: 0] b, output eq); wire [3: 0] c; // bus definition // // My. Xnor i 0 i 1 i 2 i 3 (. A(a[0]), (. A(a[1]), (. A(a[2]), (. A(a[3]), . B(b[0]), . B(b[1]), . B(b[2]), . B(b[3]), . Z(c[0]). Z(c[1]). Z(c[2]). Z(c[3]) ); ); assign c = ~(a ^ b); // XNOR assign eq = &c; // short format endmodule 112

![Highest Abstraction Level: Comparing Two Numbers module compare (input [3: 0] a, input [3: Highest Abstraction Level: Comparing Two Numbers module compare (input [3: 0] a, input [3:](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/28aa08800e5c2653690ff543d8fa8100/image-111.jpg)

Highest Abstraction Level: Comparing Two Numbers module compare (input [3: 0] a, input [3: 0] b, output eq); // assign c = ~(a ^ b); // XNOR // assign eq = &c; // short format assign eq = (a == b) ? 1 : 0; // really short endmodule 113

Writing More Reusable Verilog Code n We have a module that can compare two 4 -bit numbers n What if in the overall design we need to compare: q q q n 5 -bit numbers? 6 -bit numbers? … N-bit numbers? Writing code for each case looks tedious What could be a better way? 114

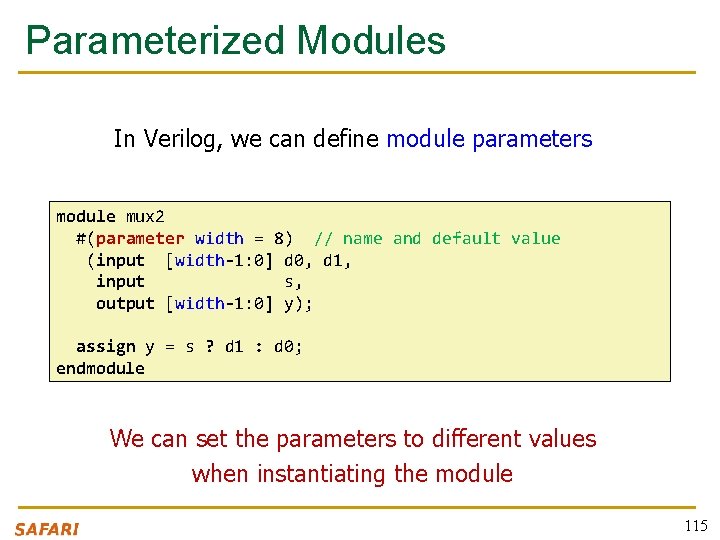

Parameterized Modules In Verilog, we can define module parameters module mux 2 #(parameter width = 8) // name and default value (input [width-1: 0] d 0, d 1, input s, output [width-1: 0] y); assign y = s ? d 1 : d 0; endmodule We can set the parameters to different values when instantiating the module 115

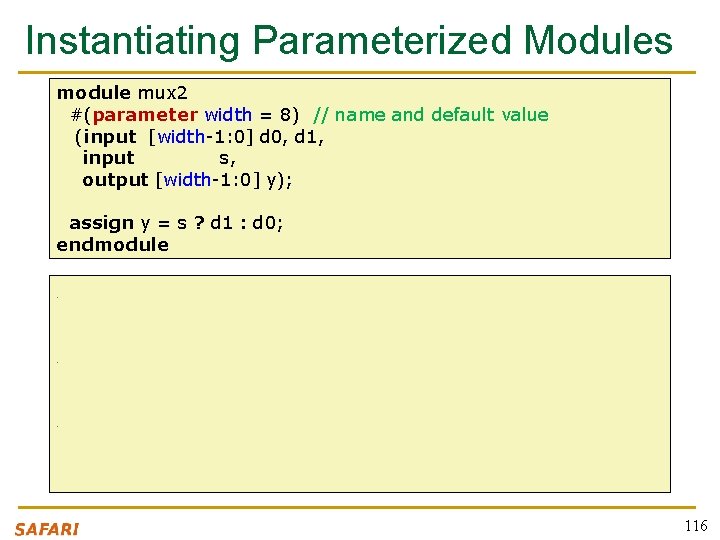

Instantiating Parameterized Modules module mux 2 #(parameter width = 8) // name and default value (input [width-1: 0] d 0, d 1, input s, output [width-1: 0] y); assign y = s ? d 1 : d 0; endmodule // If the parameter is not given, the default (8) is assumed mux 2 i_mux (d 0, d 1, s, out); // The same module with 12 -bit bus width: mux 2 #(12) i_mux_b (d 0, d 1, s, out); // A more verbose version: mux 2 #(. width(12)) i_mux_b (. d 0(d 0), . d 1(d 1), . s(s), . out(out)); 116

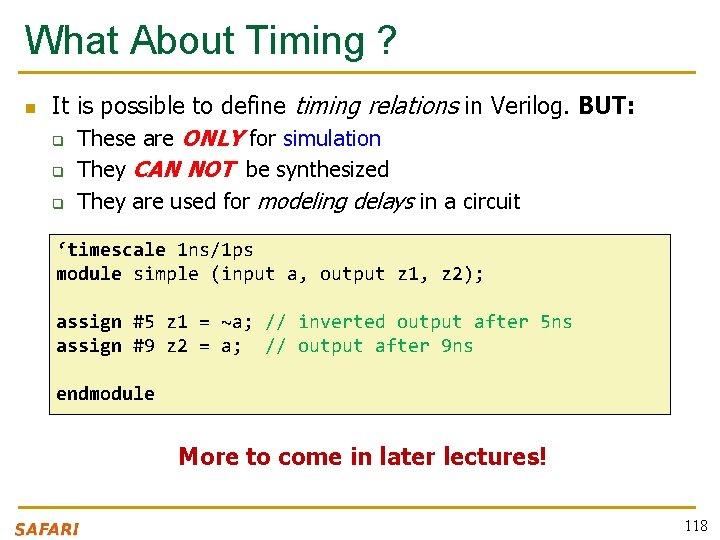

What About Timing ? n It is possible to define timing relations in Verilog. BUT: q These are ONLY for simulation q They CAN NOT be synthesized q They are used for modeling delays in a circuit ‘timescale 1 ns/1 ps module simple (input a, output z 1, z 2); assign #5 z 1 = ~a; // inverted output after 5 ns assign #9 z 2 = a; // output after 9 ns endmodule More to come in later lectures! 118

Good Practices n Develop/use a consistent naming style n Use MSB to LSB ordering for buses q n Define one module per file q n Makes managing your design hierarchy easier Use a file name that equals module name q n Use “a[31: 0]”, not “a[0: 31]” i. e. , module Try. This is defined in a file called Try. This. v Always keep in mind that Verilog describes hardware 119

Summary n We have seen an overview of Verilog n Discussed structural and behavioral modeling n Showed combinational logic constructs 120

Next Lecture: Sequential Logic 121

Design of Digital Circuits Lecture 6: Combinational Logic, Hardware Description Lang. & Verilog Prof. Onur Mutlu ETH Zurich Spring 2018 9 March 2018

- Slides: 119