DEPARTMENT OF MARINE SCIENCES SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT COASTAL

- Slides: 37

DEPARTMENT OF MARINE SCIENCES SCHOOL OF ENVIRONMENT COASTAL GEOLOGY 4 Waves Ι: Introduction to wave theories A. F. Velegrakis

4 Waves Ι: Introduction to wave theories 4. 1 Types of waves 4. 2 Progressive waves 4. 3 Wave theories 4. 3. 1 Airy theory (linear wave theory) 4. 3. 2 Stokes theory 4. 3. 3 Shallow water wave theories (a) Solitary waves (b) Cnoidal waves

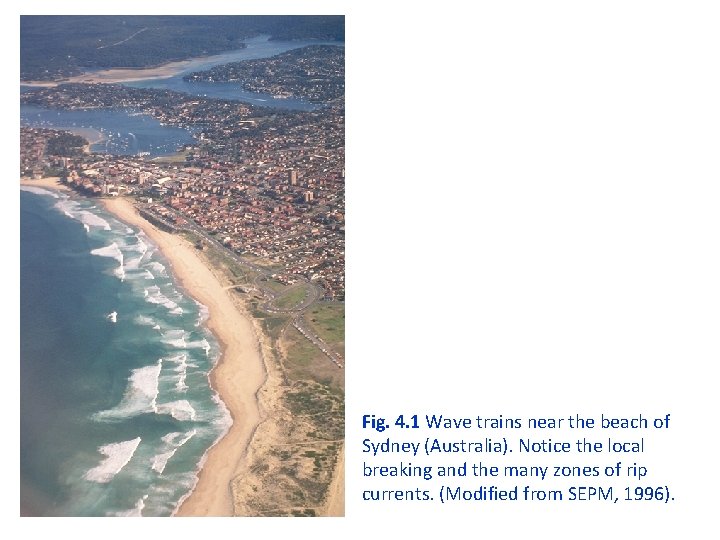

The waves are the biggest source of energy for the coasts/beaches

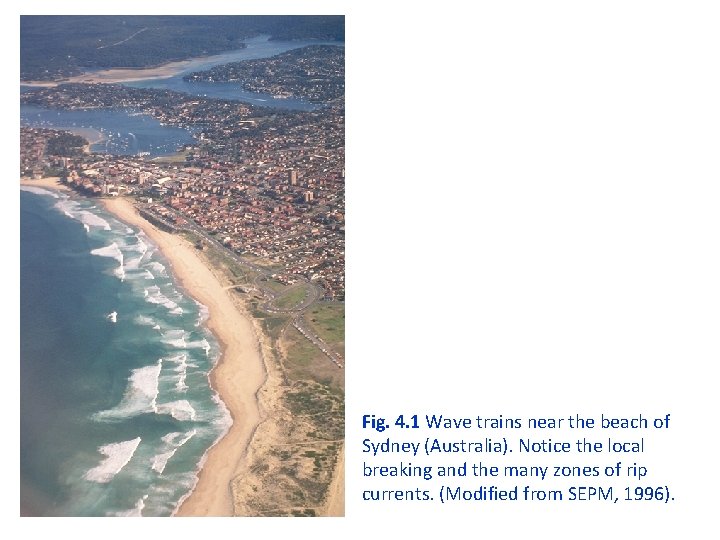

Fig. 4. 1 Wave trains near the beach of Sydney (Australia). Notice the local breaking and the many zones of rip currents. (Modified from SEPM, 1996).

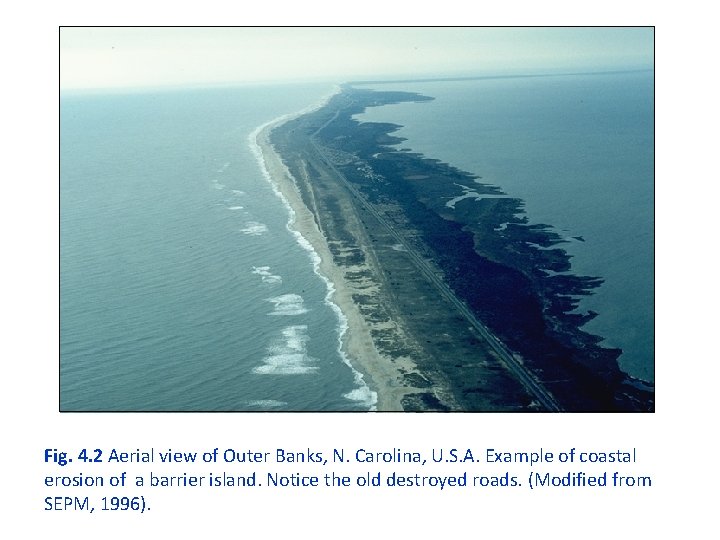

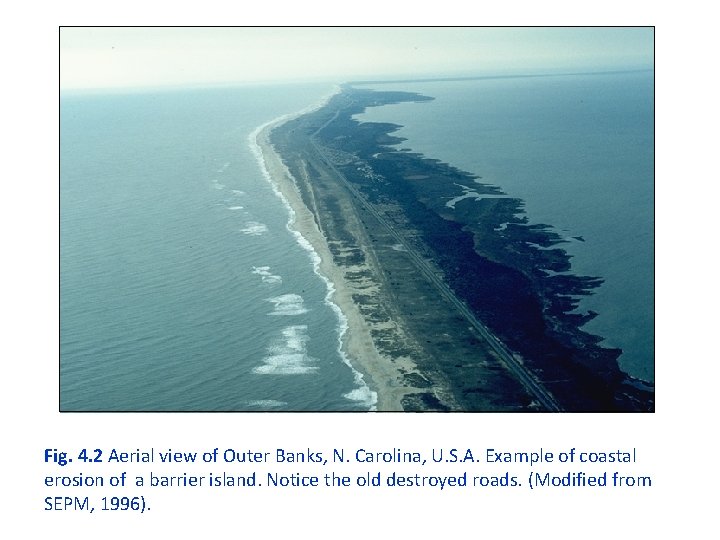

Fig. 4. 2 Aerial view of Outer Banks, N. Carolina, U. S. A. Example of coastal erosion of a barrier island. Notice the old destroyed roads. (Modified from SEPM, 1996).

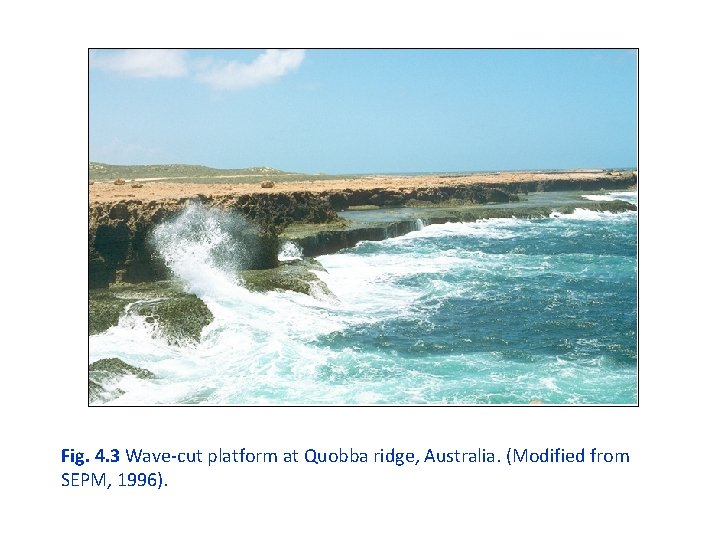

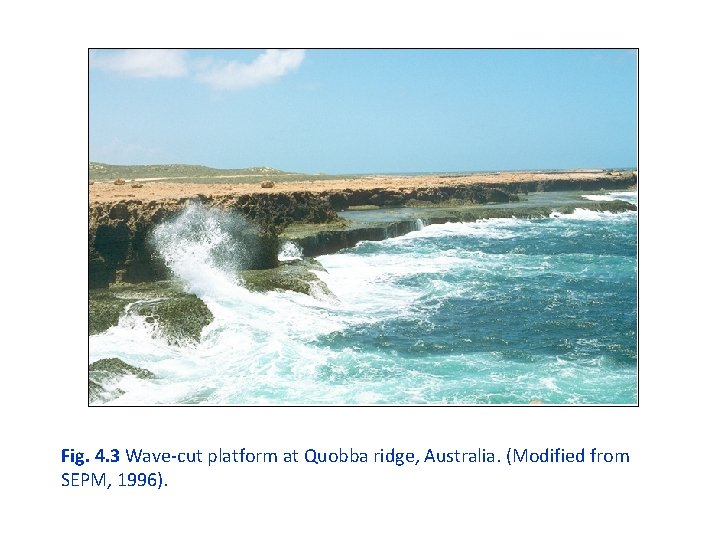

Fig. 4. 3 Wave-cut platform at Quobba ridge, Australia. (Modified from SEPM, 1996).

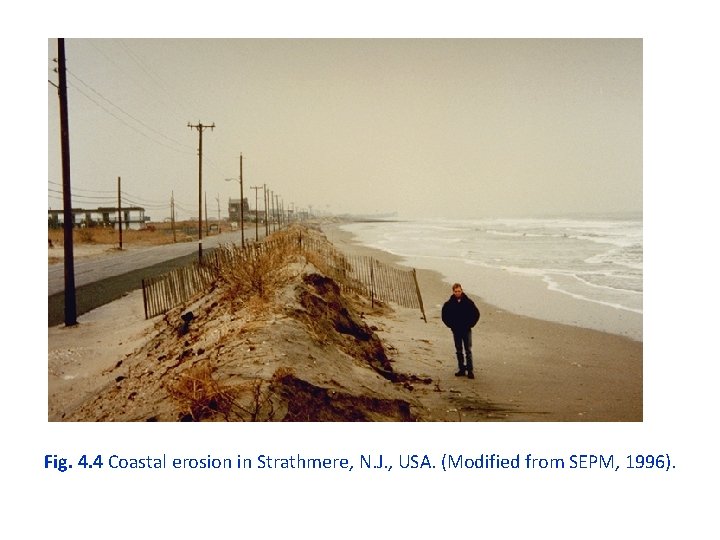

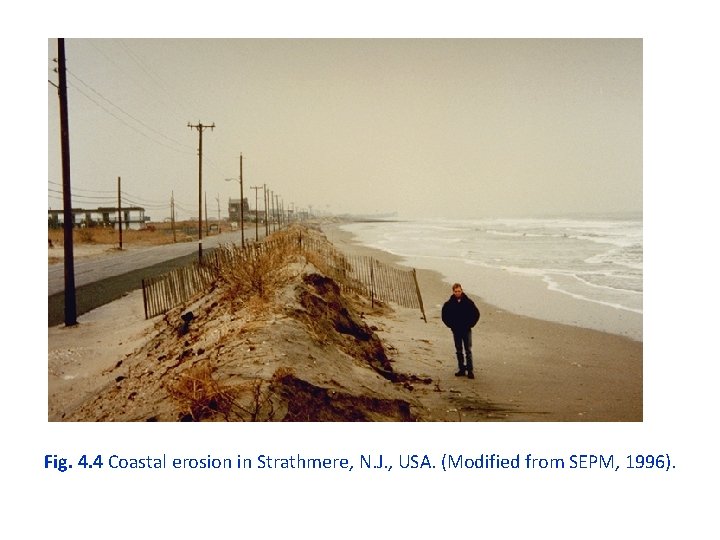

Fig. 4. 4 Coastal erosion in Strathmere, N. J. , USA. (Modified from SEPM, 1996).

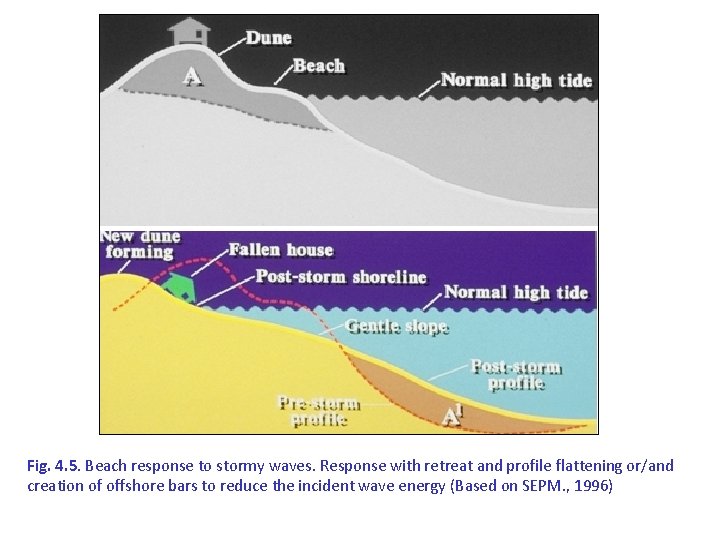

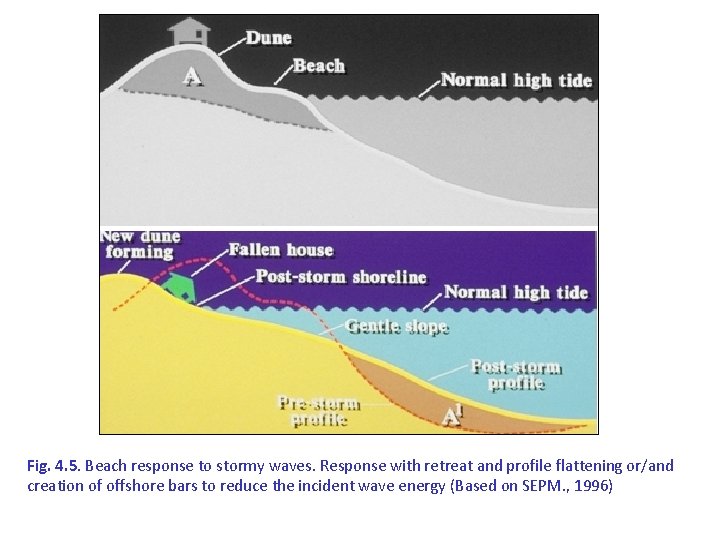

Fig. 4. 5. Beach response to stormy waves. Response with retreat and profile flattening or/and creation of offshore bars to reduce the incident wave energy (Based on SEPM. , 1996)

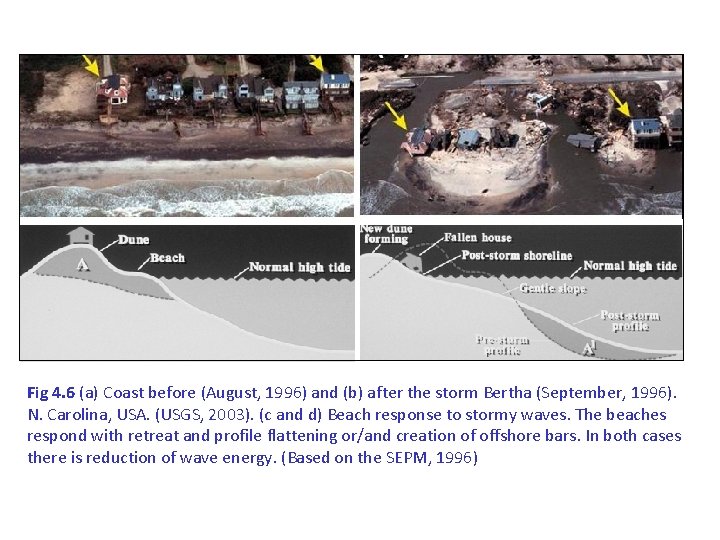

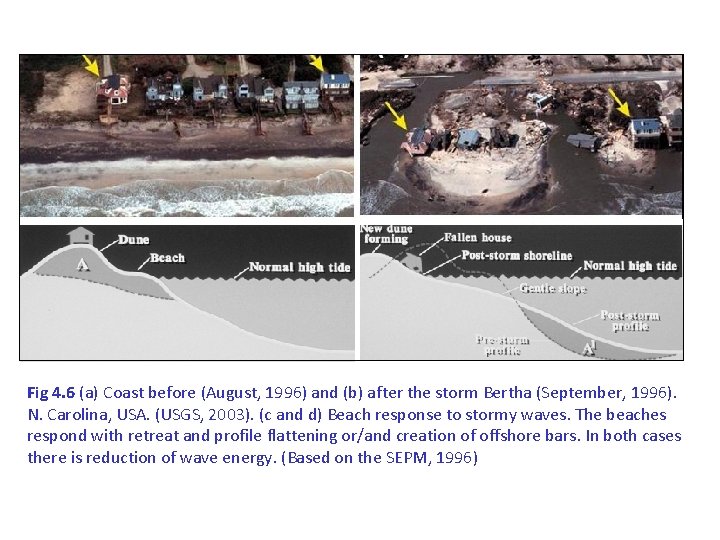

Fig 4. 6 (a) Coast before (August, 1996) and (b) after the storm Bertha (September, 1996). N. Carolina, USA. (USGS, 2003). (c and d) Beach response to stormy waves. The beaches respond with retreat and profile flattening or/and creation of offshore bars. In both cases there is reduction of wave energy. (Based on the SEPM, 1996)

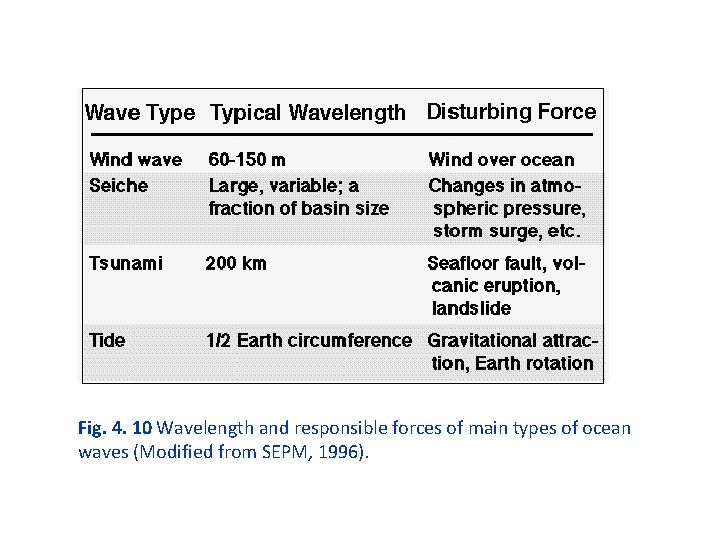

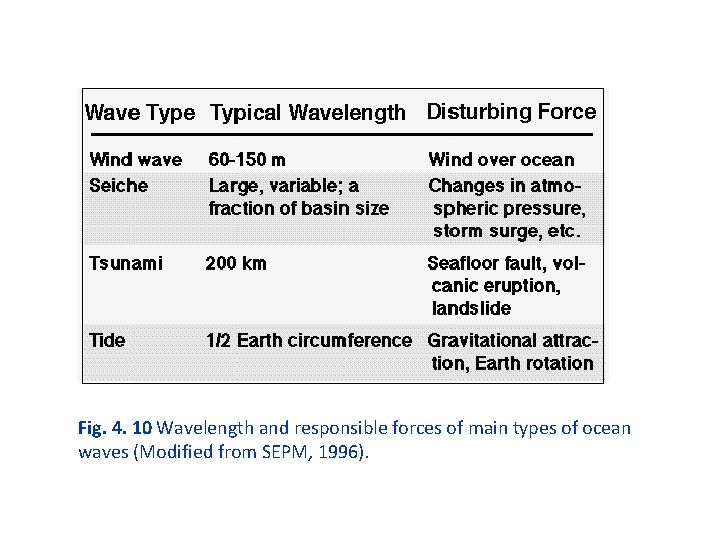

4. 1 Types of waves There are many kinds of waves in the oceans Their differentiation is based on (a) the responsible forces and (b) its characteristics i. e. the period, wavelength, normality, etc

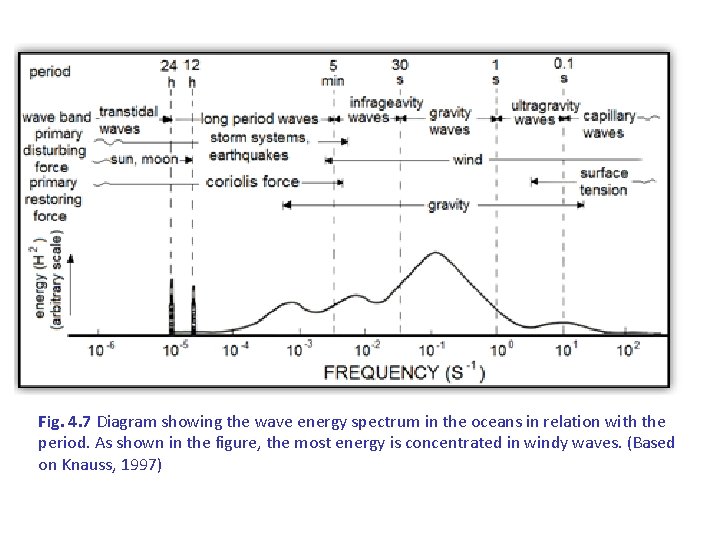

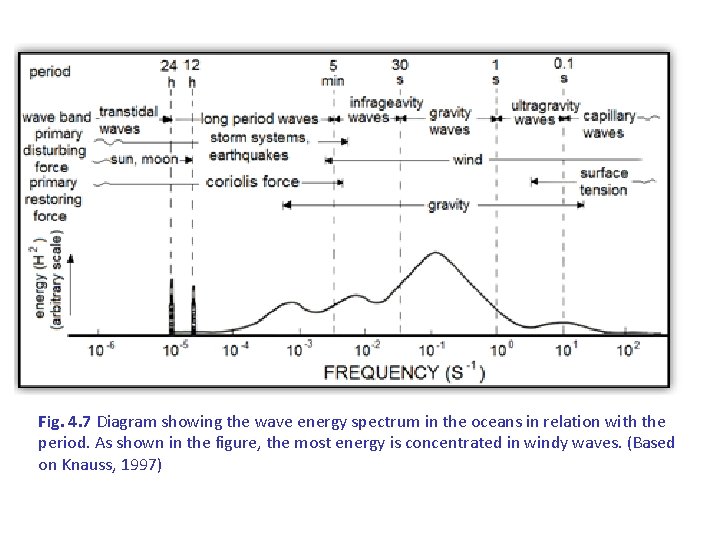

Fig. 4. 7 Diagram showing the wave energy spectrum in the oceans in relation with the period. As shown in the figure, the most energy is concentrated in windy waves. (Based on Knauss, 1997)

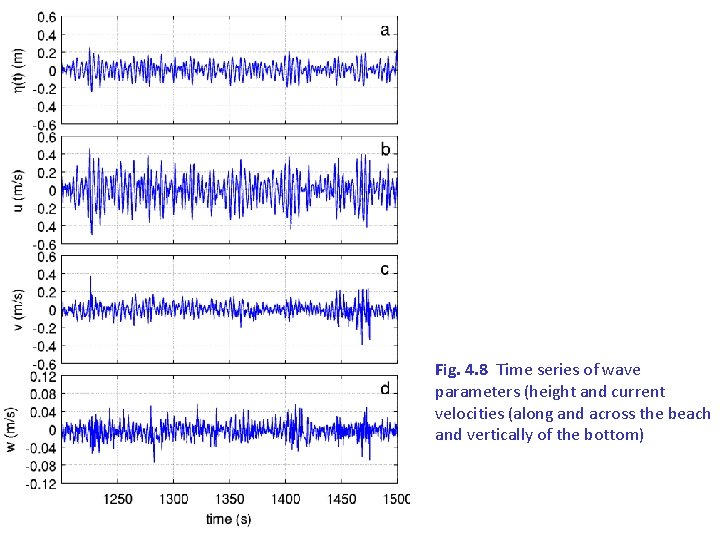

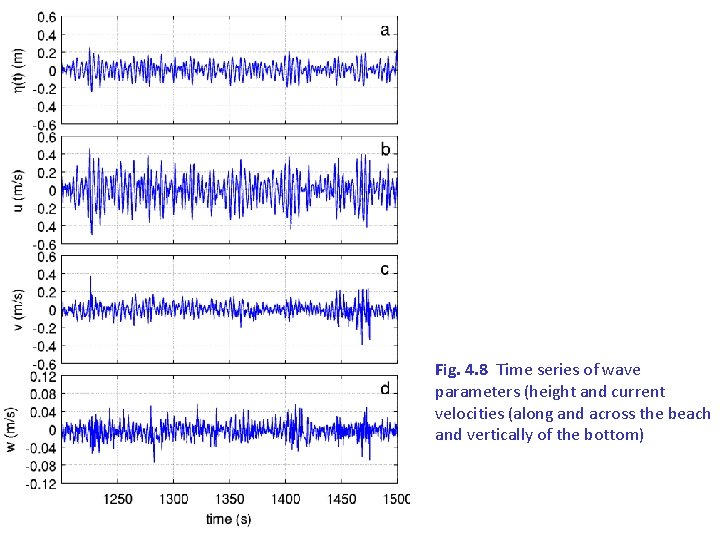

Fig. 4. 8 Time series of wave parameters (height and current velocities (along and across the beach and vertically of the bottom)

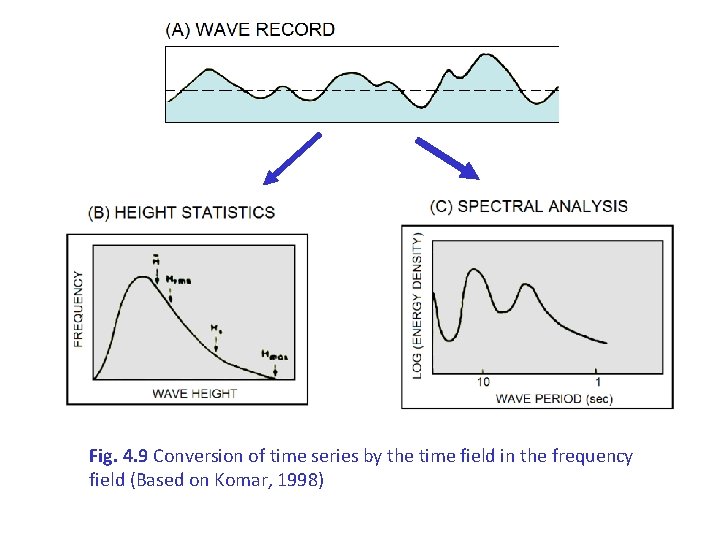

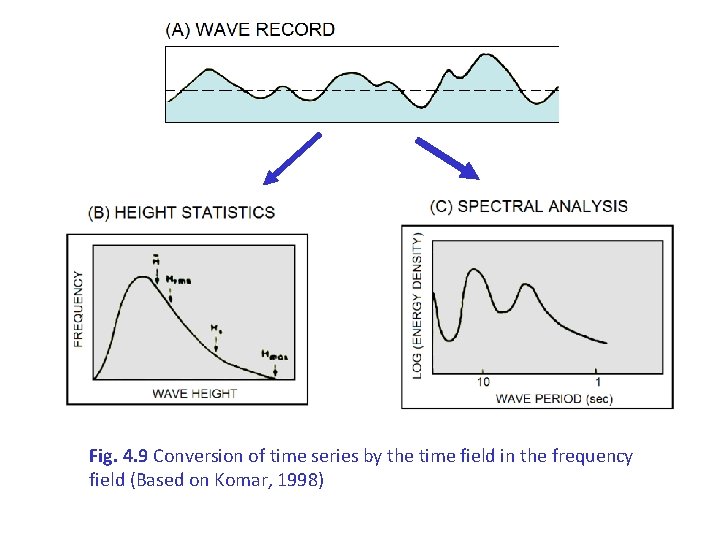

Fig. 4. 9 Conversion of time series by the time field in the frequency field (Based on Komar, 1998)

Fig. 4. 10 Wavelength and responsible forces of main types of ocean waves (Modified from SEPM, 1996).

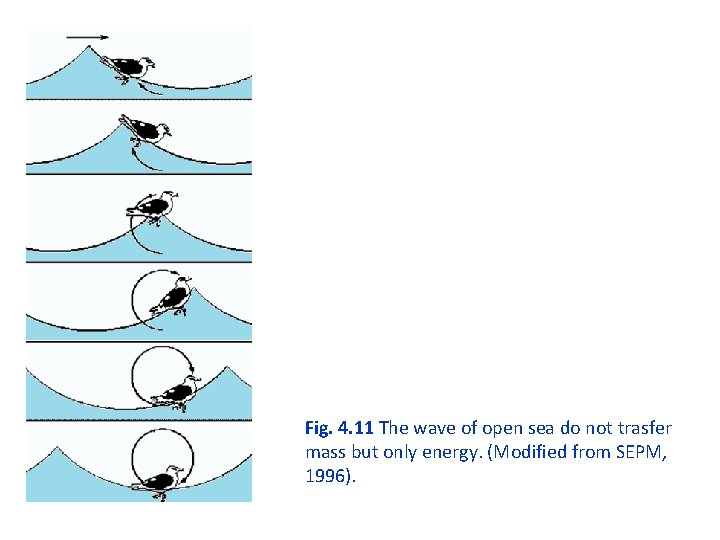

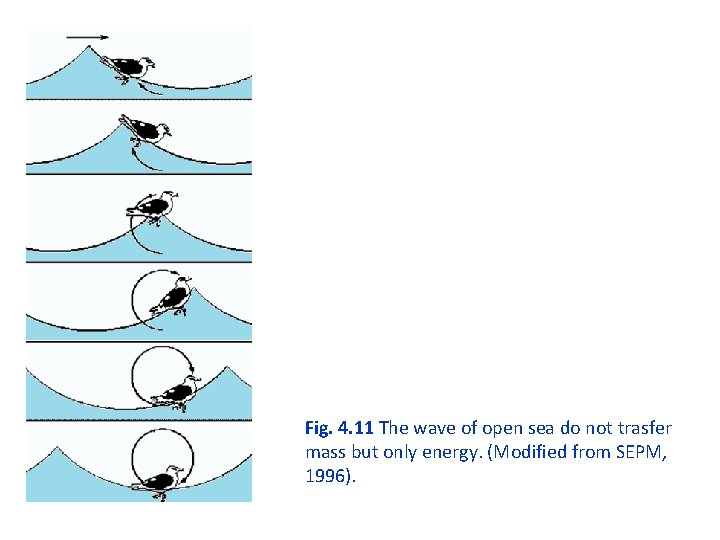

Fig. 4. 11 The wave of open sea do not trasfer mass but only energy. (Modified from SEPM, 1996).

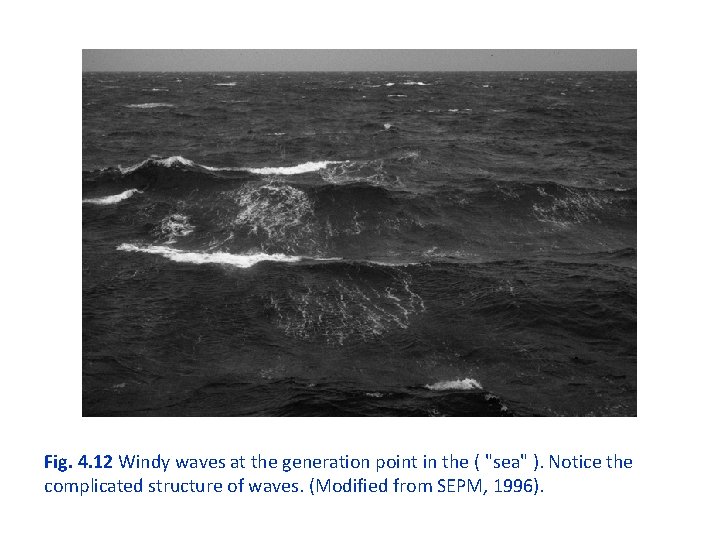

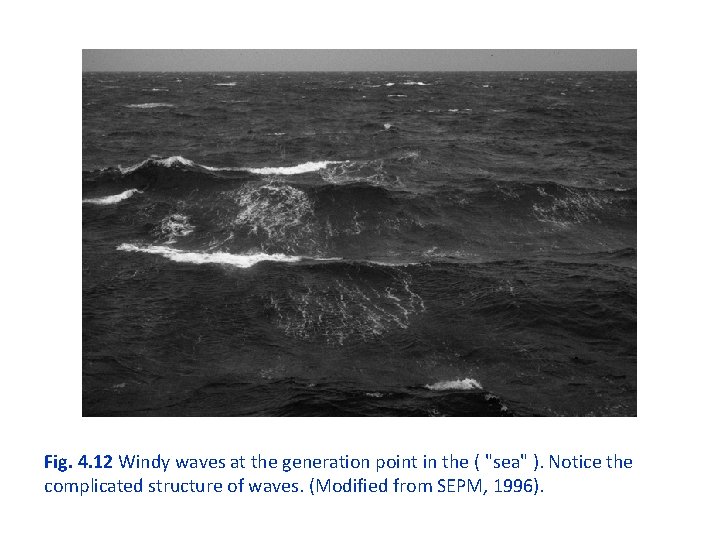

Fig. 4. 12 Windy waves at the generation point in the ( "sea" ). Notice the complicated structure of waves. (Modified from SEPM, 1996).

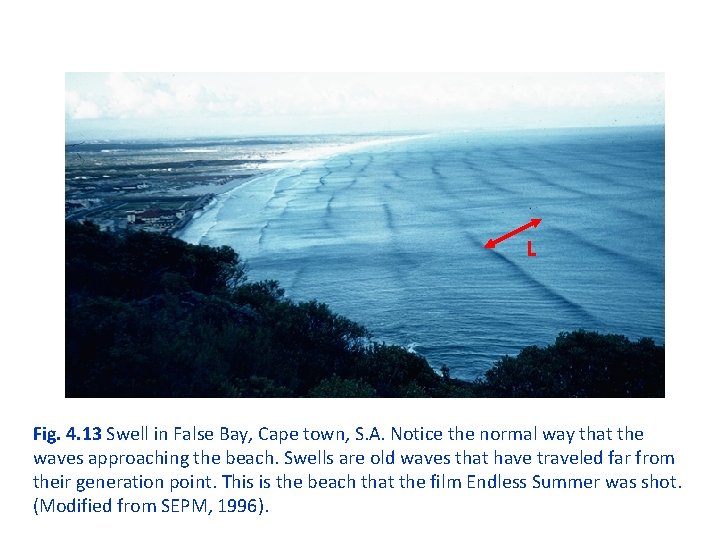

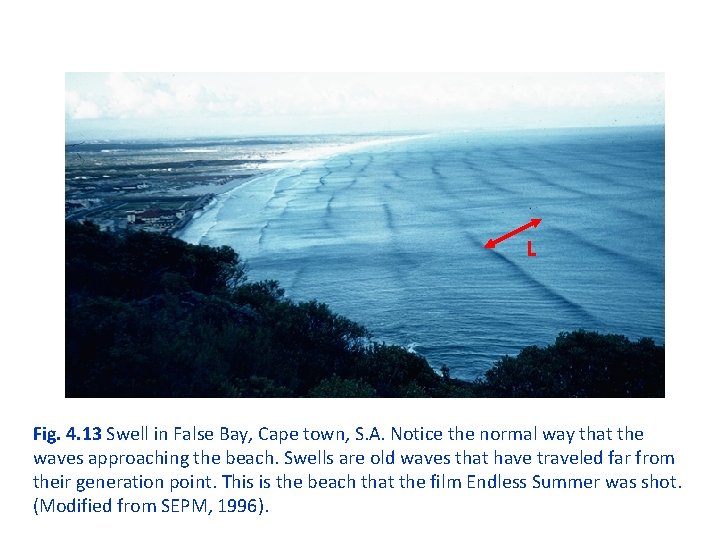

L Fig. 4. 13 Swell in False Bay, Cape town, S. A. Notice the normal way that the waves approaching the beach. Swells are old waves that have traveled far from their generation point. This is the beach that the film Endless Summer was shot. (Modified from SEPM, 1996).

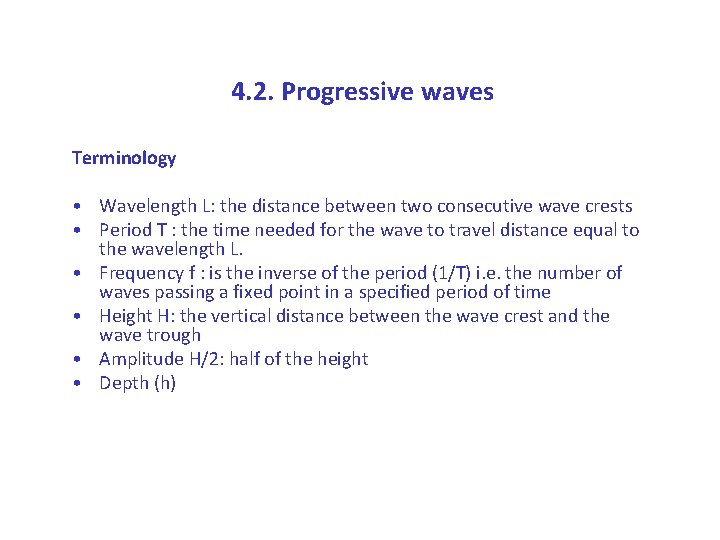

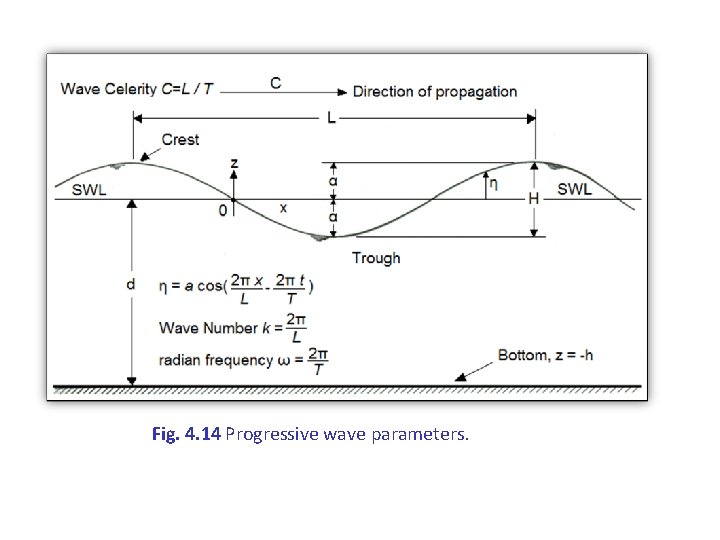

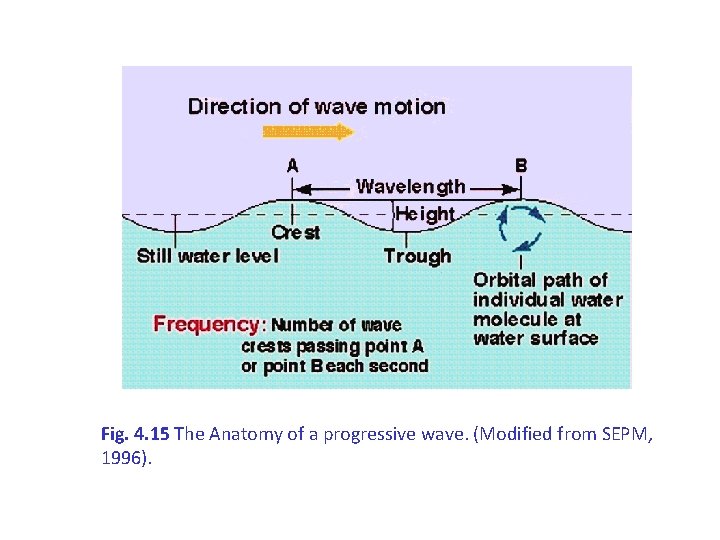

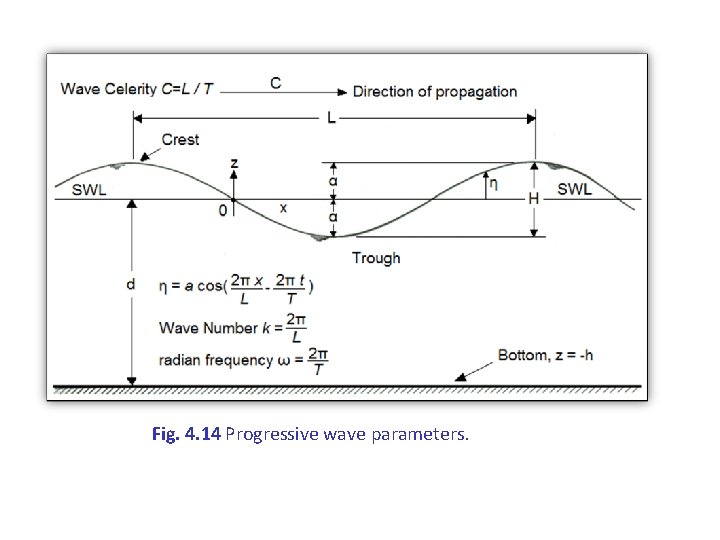

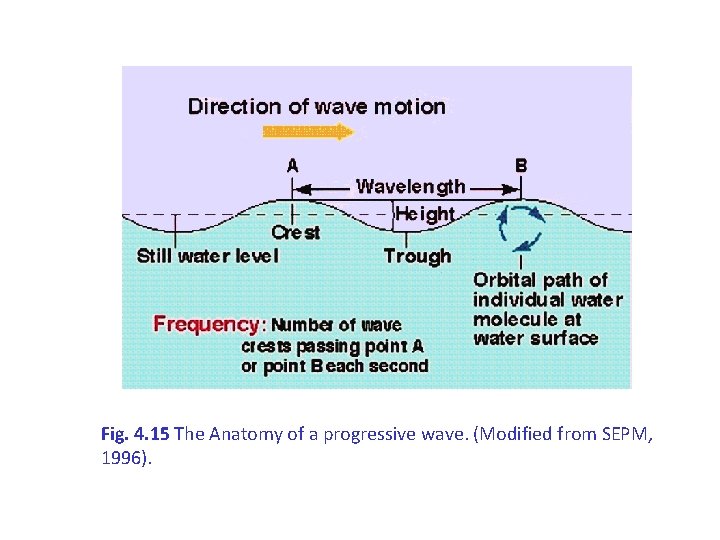

4. 2. Progressive waves Terminology • Wavelength L: the distance between two consecutive wave crests • Period T : the time needed for the wave to travel distance equal to the wavelength L. • Frequency f : is the inverse of the period (1/T) i. e. the number of waves passing a fixed point in a specified period of time • Height H: the vertical distance between the wave crest and the wave trough • Amplitude H/2: half of the height • Depth (h)

Fig. 4. 14 Progressive wave parameters.

Fig. 4. 15 The Anatomy of a progressive wave. (Modified from SEPM, 1996).

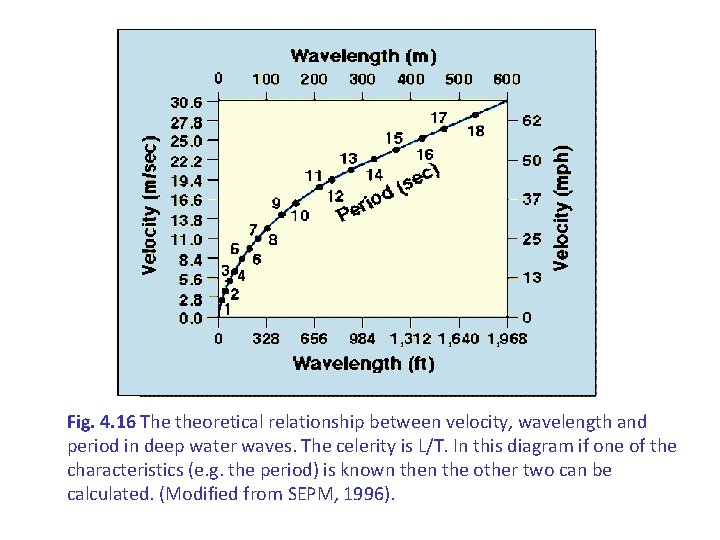

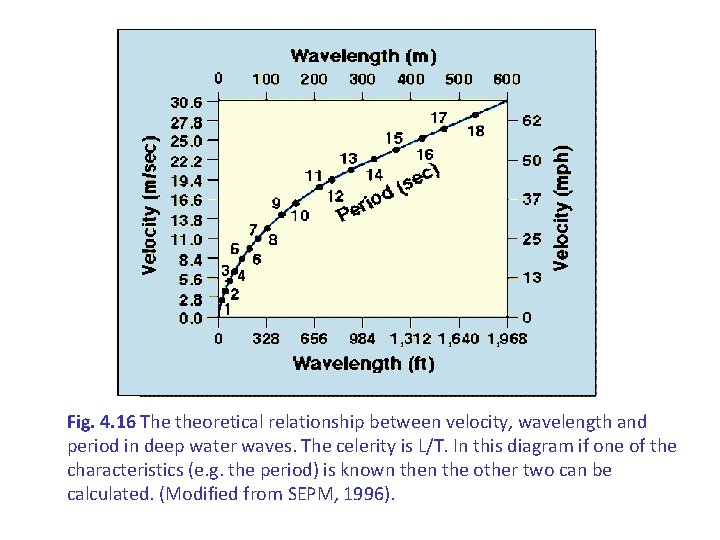

Fig. 4. 16 The theoretical relationship between velocity, wavelength and period in deep water waves. The celerity is L/T. In this diagram if one of the characteristics (e. g. the period) is known the other two can be calculated. (Modified from SEPM, 1996).

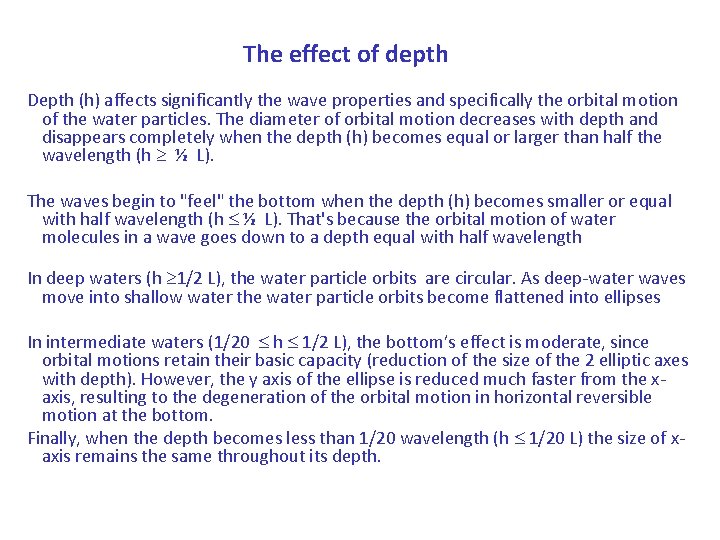

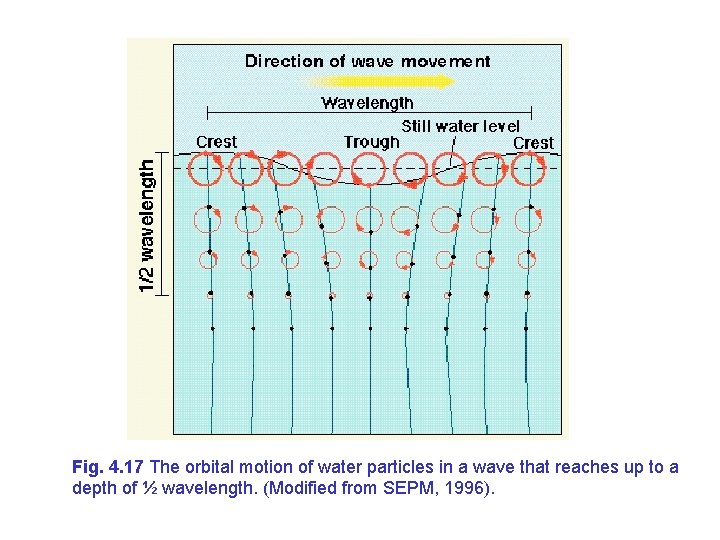

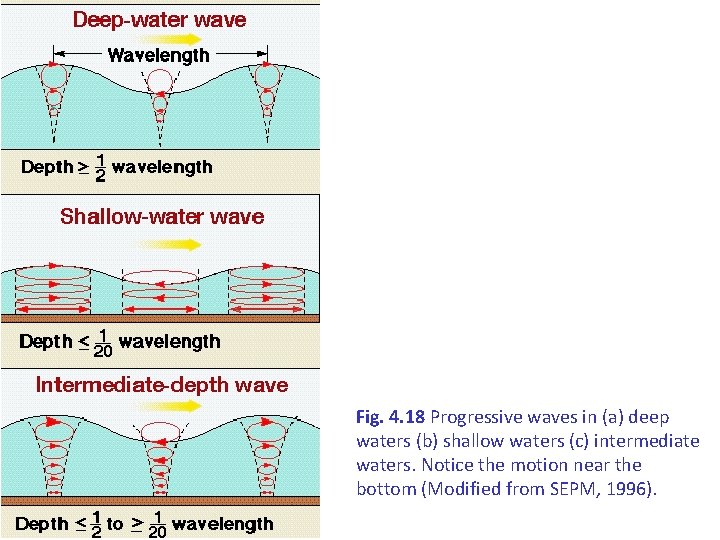

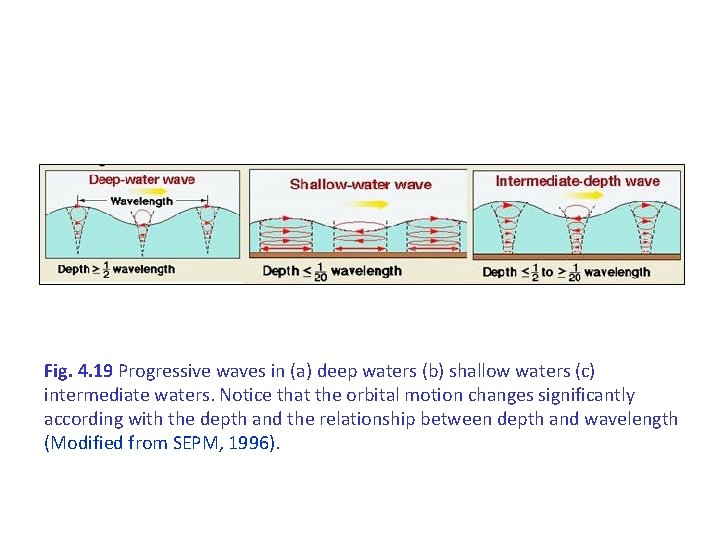

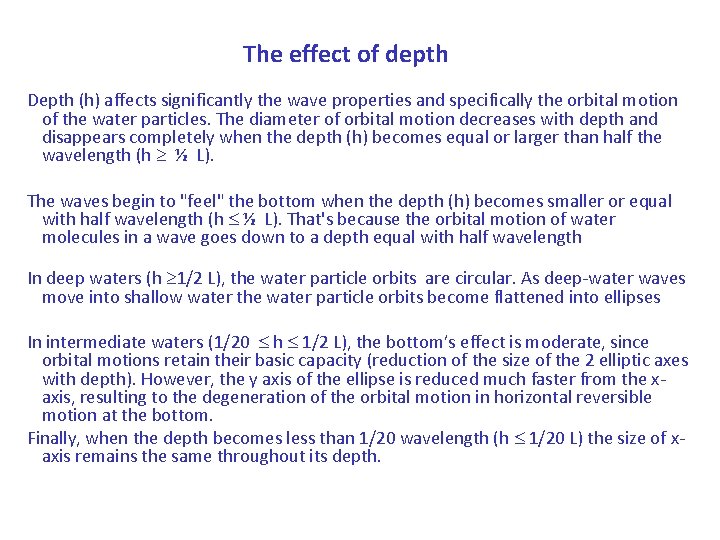

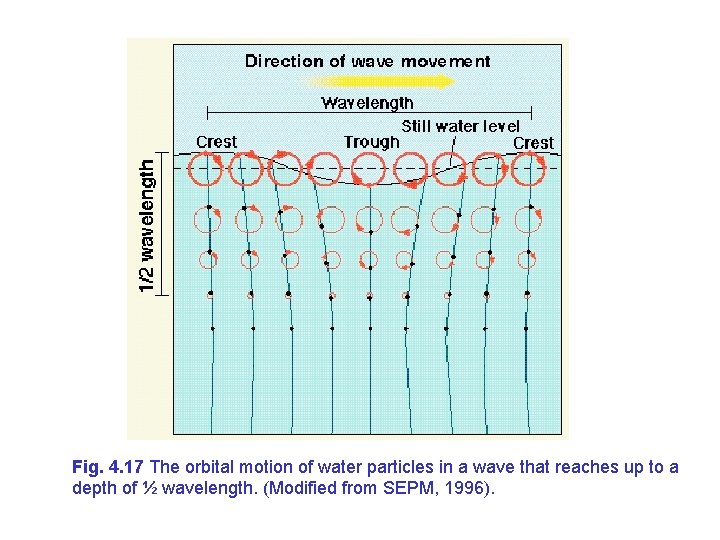

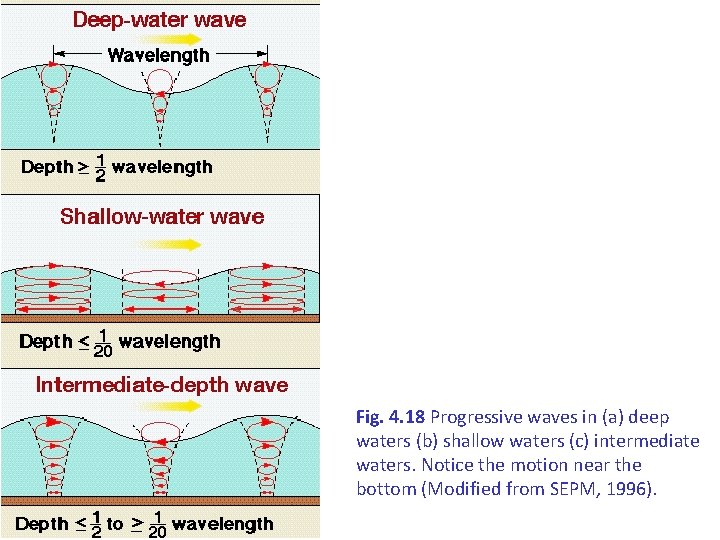

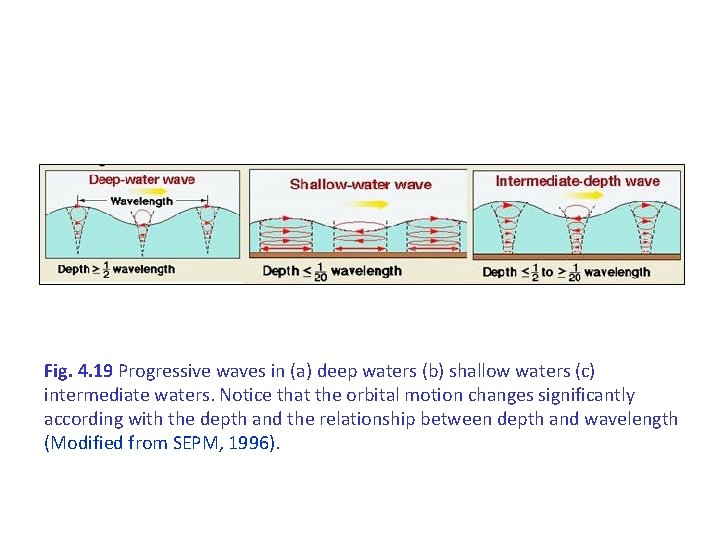

The effect of depth Depth (h) affects significantly the wave properties and specifically the orbital motion of the water particles. The diameter of orbital motion decreases with depth and disappears completely when the depth (h) becomes equal or larger than half the wavelength (h ½ L). The waves begin to "feel" the bottom when the depth (h) becomes smaller or equal with half wavelength (h ½ L). That's because the orbital motion of water molecules in a wave goes down to a depth equal with half wavelength In deep waters (h 1/2 L), the water particle orbits are circular. As deep-water waves move into shallow water the water particle orbits become flattened into ellipses In intermediate waters (1/20 h 1/2 L), the bottom’s effect is moderate, since orbital motions retain their basic capacity (reduction of the size of the 2 elliptic axes with depth). However, the y axis of the ellipse is reduced much faster from the xaxis, resulting to the degeneration of the orbital motion in horizontal reversible motion at the bottom. Finally, when the depth becomes less than 1/20 wavelength (h 1/20 L) the size of xaxis remains the same throughout its depth.

Fig. 4. 17 The orbital motion of water particles in a wave that reaches up to a depth of ½ wavelength. (Modified from SEPM, 1996).

Fig. 4. 18 Progressive waves in (a) deep waters (b) shallow waters (c) intermediate waters. Notice the motion near the bottom (Modified from SEPM, 1996).

Fig. 4. 19 Progressive waves in (a) deep waters (b) shallow waters (c) intermediate waters. Notice that the orbital motion changes significantly according with the depth and the relationship between depth and wavelength (Modified from SEPM, 1996).

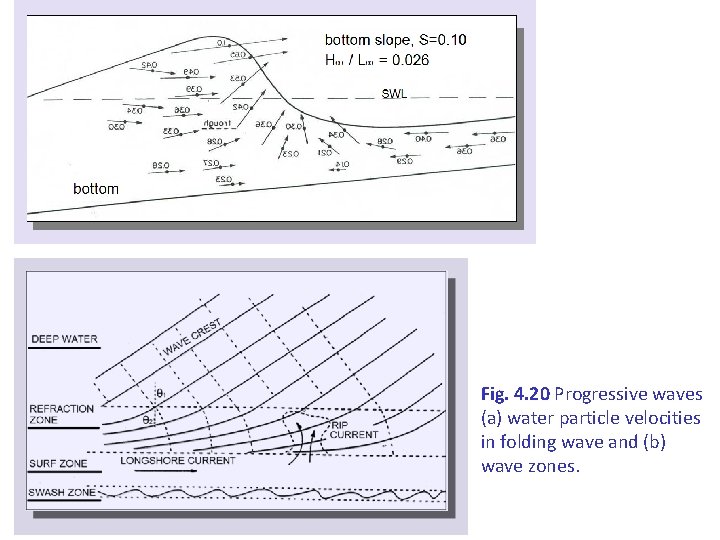

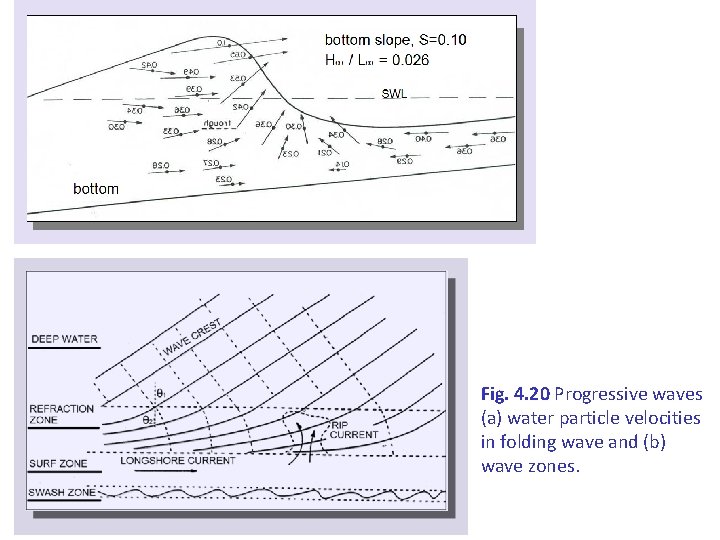

Fig. 4. 20 Progressive waves (a) water particle velocities in folding wave and (b) wave zones.

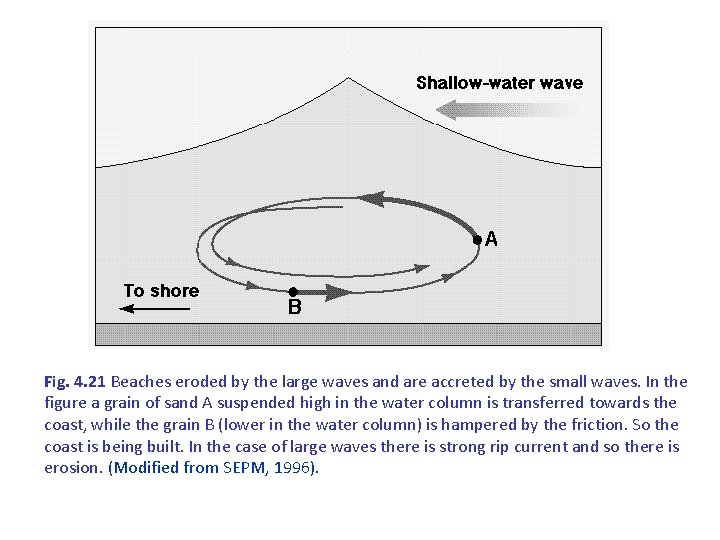

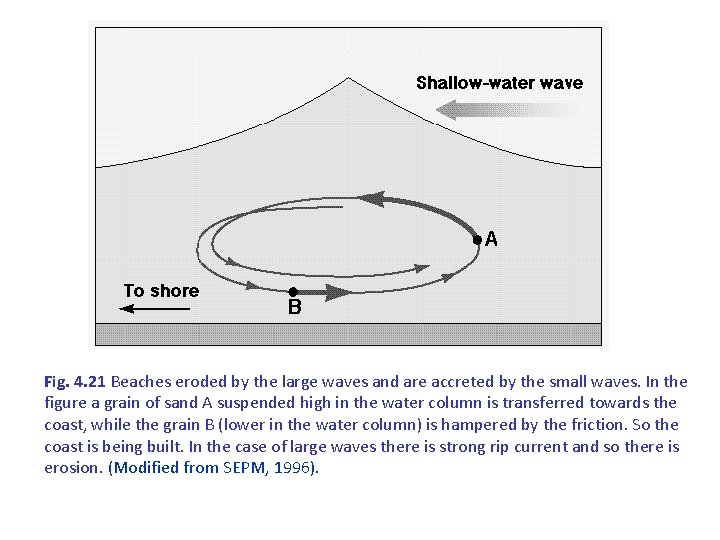

Fig. 4. 21 Beaches eroded by the large waves and are accreted by the small waves. In the figure a grain of sand A suspended high in the water column is transferred towards the coast, while the grain B (lower in the water column) is hampered by the friction. So the coast is being built. In the case of large waves there is strong rip current and so there is erosion. (Modified from SEPM, 1996).

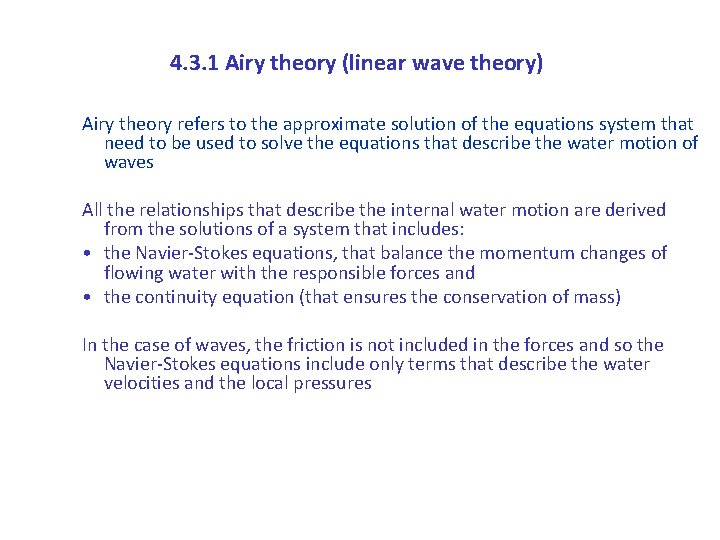

4. 3. 1 Airy theory (linear wave theory) Airy theory refers to the approximate solution of the equations system that need to be used to solve the equations that describe the water motion of waves All the relationships that describe the internal water motion are derived from the solutions of a system that includes: • the Navier-Stokes equations, that balance the momentum changes of flowing water with the responsible forces and • the continuity equation (that ensures the conservation of mass) In the case of waves, the friction is not included in the forces and so the Navier-Stokes equations include only terms that describe the water velocities and the local pressures

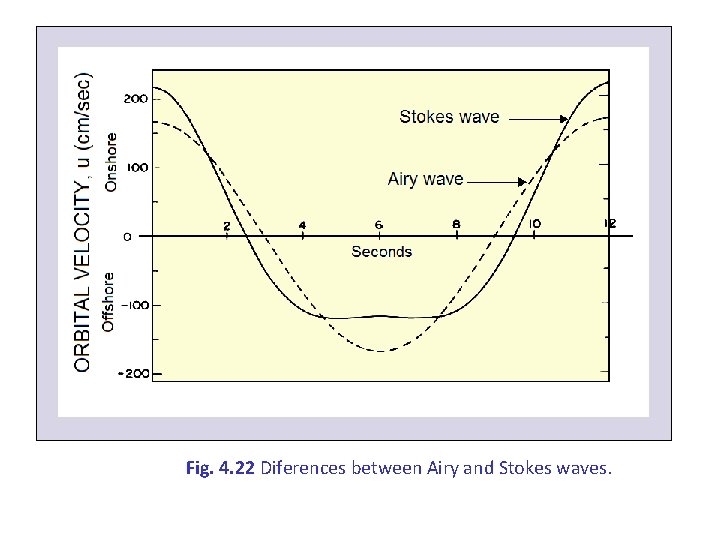

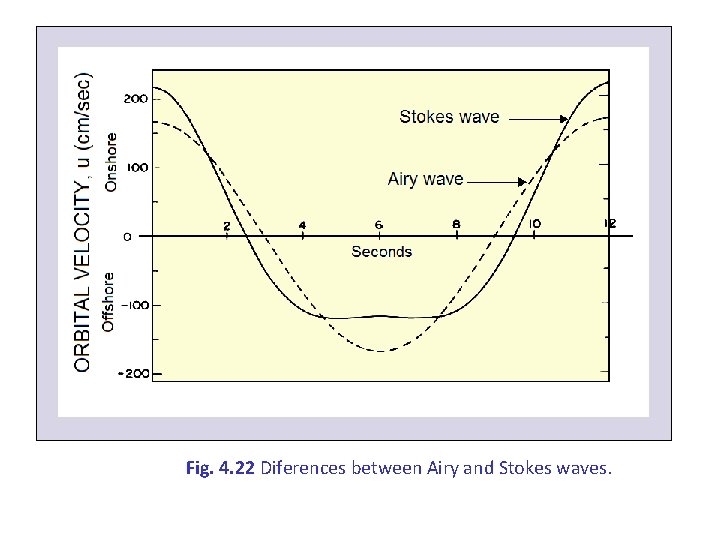

Fig. 4. 22 Diferences between Airy and Stokes waves.

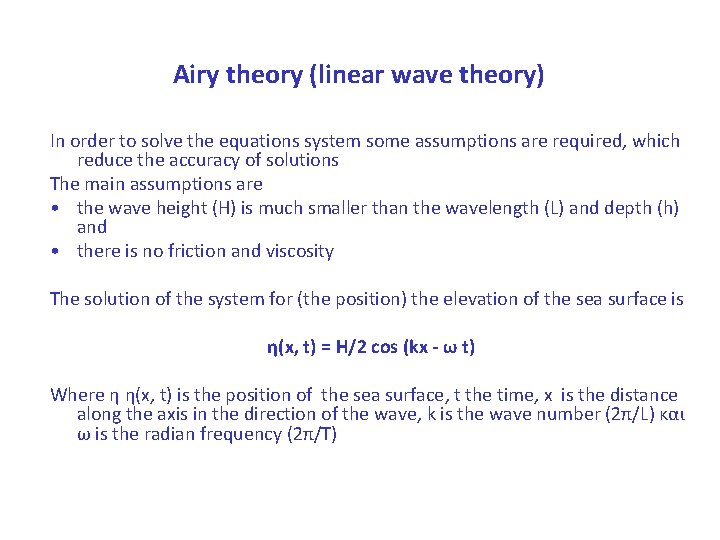

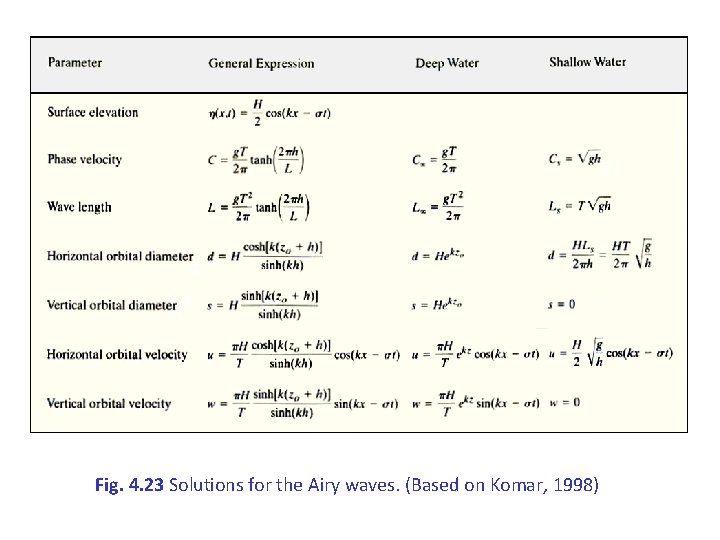

Airy theory (linear wave theory) In order to solve the equations system some assumptions are required, which reduce the accuracy of solutions The main assumptions are • the wave height (H) is much smaller than the wavelength (L) and depth (h) and • there is no friction and viscosity The solution of the system for (the position) the elevation of the sea surface is η(x, t) = H/2 cos (kx - ω t) Where η η(x, t) is the position of the sea surface, t the time, x is the distance along the axis in the direction of the wave, k is the wave number (2π/L) και ω is the radian frequency (2π/Τ)

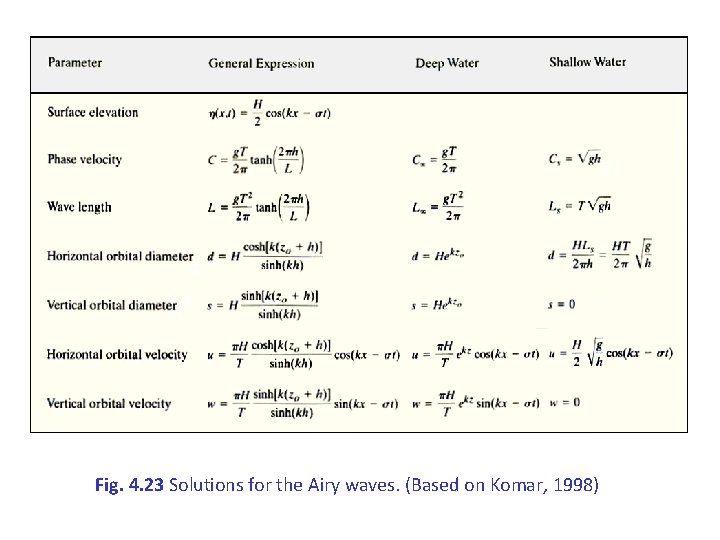

Fig. 4. 23 Solutions for the Airy waves. (Based on Komar, 1998)

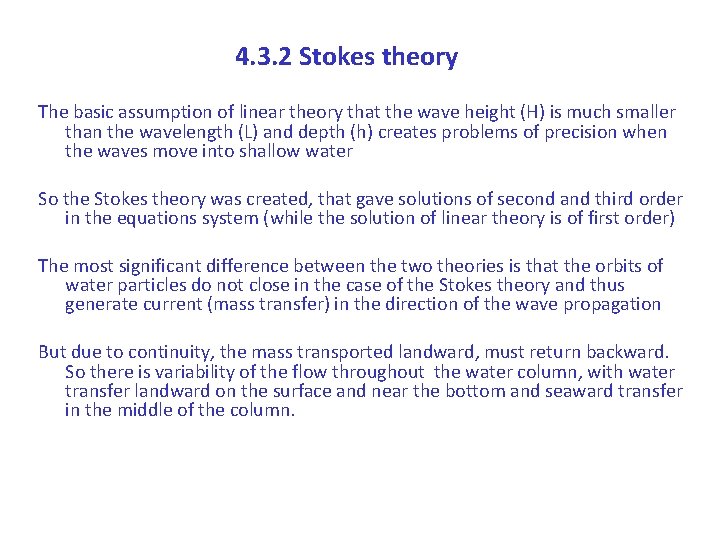

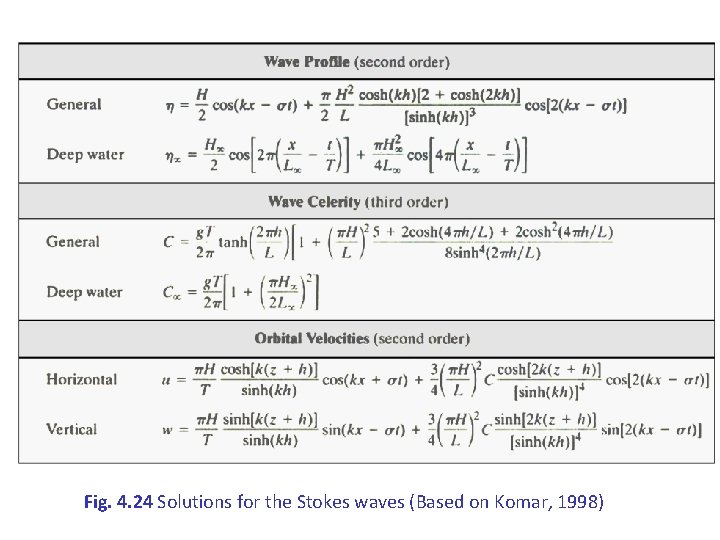

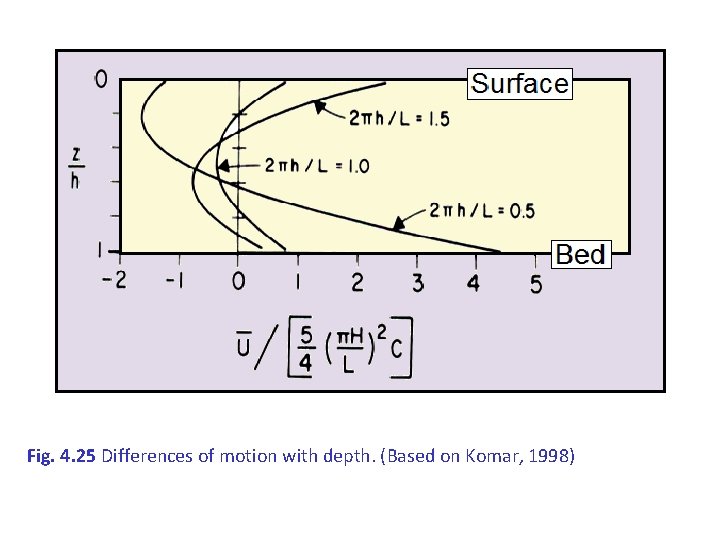

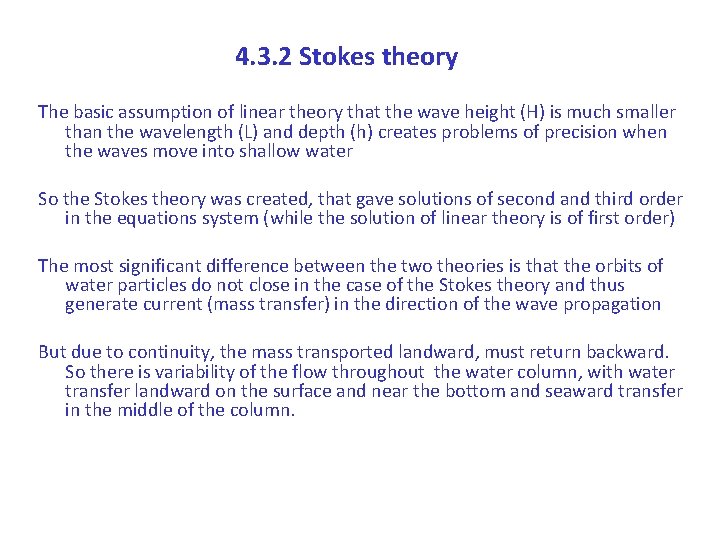

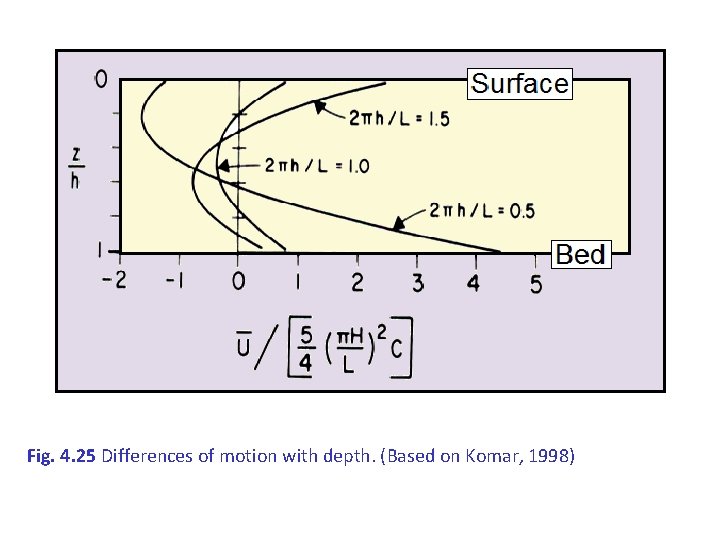

4. 3. 2 Stokes theory The basic assumption of linear theory that the wave height (H) is much smaller than the wavelength (L) and depth (h) creates problems of precision when the waves move into shallow water So the Stokes theory was created, that gave solutions of second and third order in the equations system (while the solution of linear theory is of first order) The most significant difference between the two theories is that the orbits of water particles do not close in the case of the Stokes theory and thus generate current (mass transfer) in the direction of the wave propagation But due to continuity, the mass transported landward, must return backward. So there is variability of the flow throughout the water column, with water transfer landward on the surface and near the bottom and seaward transfer in the middle of the column.

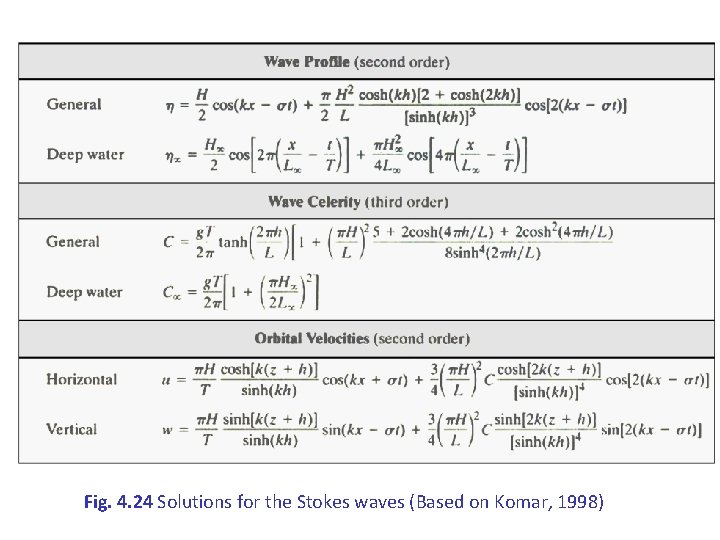

Fig. 4. 24 Solutions for the Stokes waves (Based on Komar, 1998)

Fig. 4. 25 Differences of motion with depth. (Based on Komar, 1998)

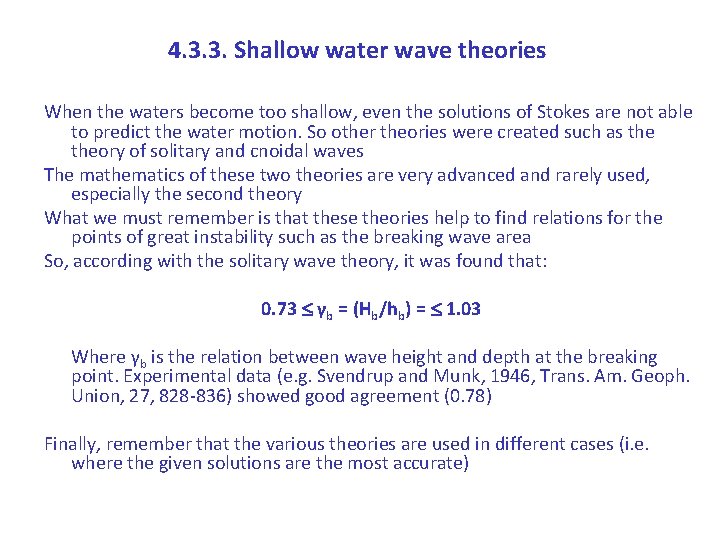

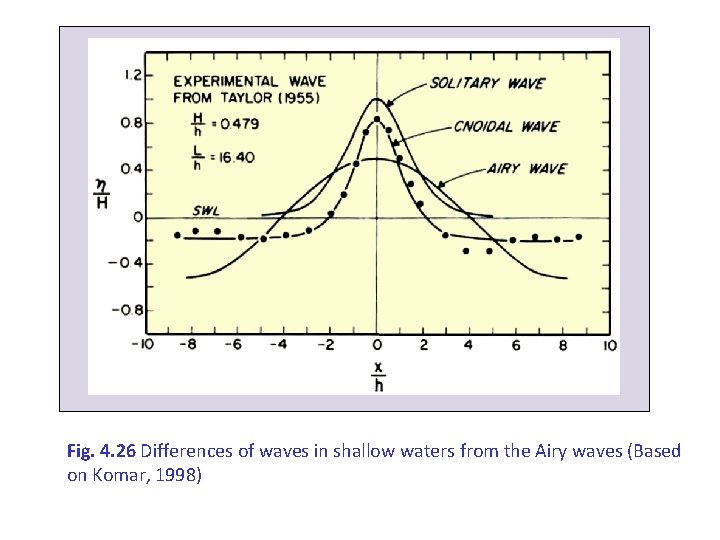

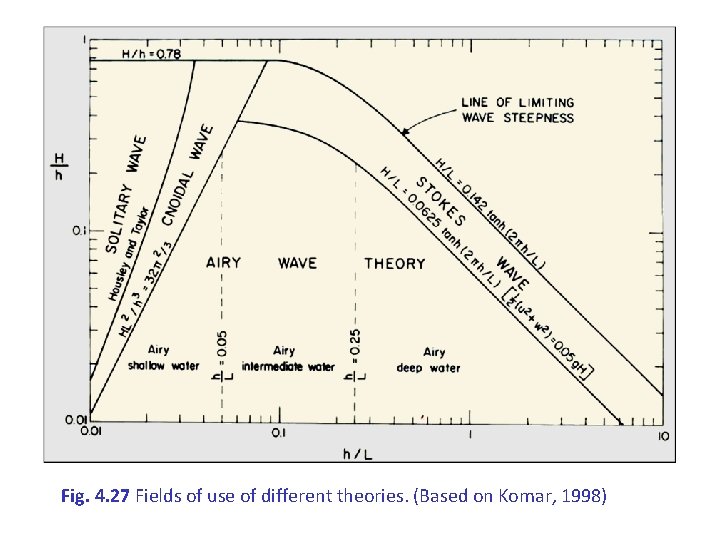

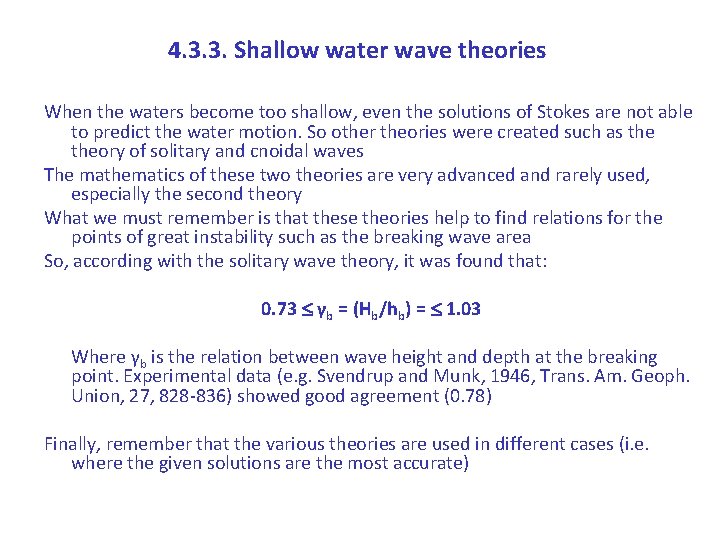

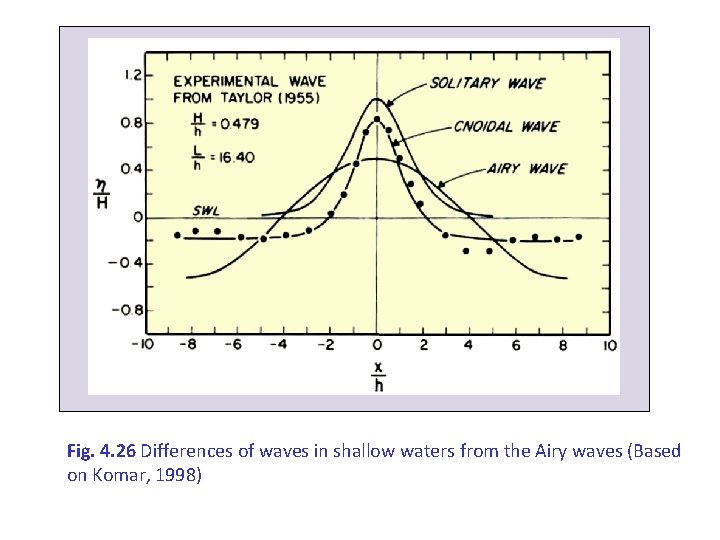

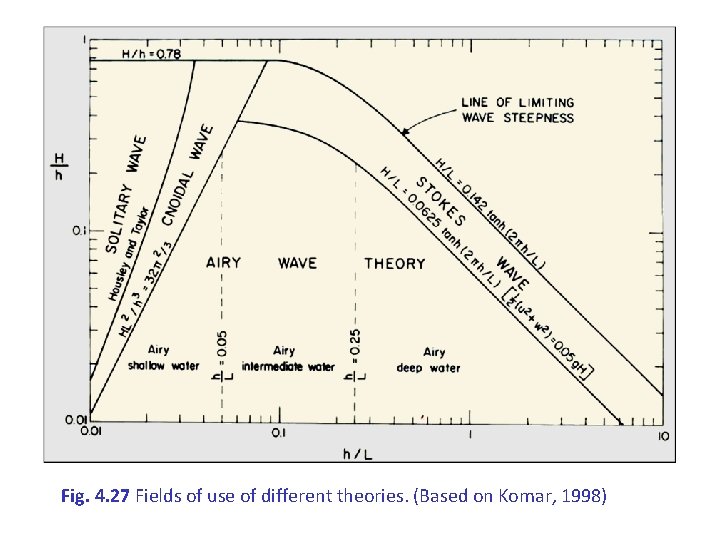

4. 3. 3. Shallow water wave theories When the waters become too shallow, even the solutions of Stokes are not able to predict the water motion. So other theories were created such as theory of solitary and cnoidal waves The mathematics of these two theories are very advanced and rarely used, especially the second theory What we must remember is that these theories help to find relations for the points of great instability such as the breaking wave area So, according with the solitary wave theory, it was found that: 0. 73 γb = (Hb/hb) = 1. 03 Where γb is the relation between wave height and depth at the breaking point. Experimental data (e. g. Svendrup and Munk, 1946, Trans. Am. Geoph. Union, 27, 828 -836) showed good agreement (0. 78) Finally, remember that the various theories are used in different cases (i. e. where the given solutions are the most accurate)

Fig. 4. 26 Differences of waves in shallow waters from the Airy waves (Based on Komar, 1998)

Fig. 4. 27 Fields of use of different theories. (Based on Komar, 1998)