DEOPTIMIZATION Finding the Limits of Hardware Optimization through

![Instruction Fetching and Decoding q De-optimization #1 - Decrease Decoding Bandwidth [AMD 05] Scenario Instruction Fetching and Decoding q De-optimization #1 - Decrease Decoding Bandwidth [AMD 05] Scenario](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e0194d01fcddaa985a91ada93f4460c5/image-18.jpg)

![Instruction Fetching and Decoding q De-optimization #2 - Increase execution latency [AMD 05] Scenario Instruction Fetching and Decoding q De-optimization #2 - Increase execution latency [AMD 05] Scenario](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e0194d01fcddaa985a91ada93f4460c5/image-24.jpg)

![Instruction Scheduling q De-optimization #1 - Address-generation interlocks [AMD 05] Scenario § Scheduling loads Instruction Scheduling q De-optimization #1 - Address-generation interlocks [AMD 05] Scenario § Scheduling loads](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e0194d01fcddaa985a91ada93f4460c5/image-28.jpg)

![Instruction Scheduling q De-optimization #2 - Increase register pressure [AMD 05] Scenario § Avoid Instruction Scheduling q De-optimization #2 - Increase register pressure [AMD 05] Scenario § Avoid](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e0194d01fcddaa985a91ada93f4460c5/image-31.jpg)

![References: [AMD 05] AMD 64 Technology. Software Optimization Guide for AMD 64 Processors, 2005 References: [AMD 05] AMD 64 Technology. Software Optimization Guide for AMD 64 Processors, 2005](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e0194d01fcddaa985a91ada93f4460c5/image-55.jpg)

- Slides: 56

DE-OPTIMIZATION Finding the Limits of Hardware Optimization through Software De-optimization Presented By: Derek Kern, Roqyah Alalqam, Ahmed Mehzer, Mohammed

Outline: Introduction Project Structure Judging de-optimizations What does a de-op look like? General Areas of Focus § § Instruction Fetching and Decoding Instruction Scheduling Instruction Type Usage (e. g. Integer vs. FP) Branch Prediction Conclusion

What are we doing? q q De-optimization? That's crazy! Why? ? ? In the world of hardware development, when optimizations are compared, the comparisons often concern just how fast a piece of hardware can run an algorithm Yet, in the world of software development, the hardware is often a distant afterthought Given this dichotomy, how relevant are these standard analyses and comparisons?

What are we doing? q q q So, why not find out how bad it can get? By de-optimizing software, we can see how bad algorithmic performance can be if hardware isn't considered At a minimum, we want to be able to answer two questions: § How good of a compiler writer must someone be? § How good of a programmer must someone be?

Our project structure § For our research project: � We have been studying instruction fetching/ decoding/ scheduling and branch optimization � We have been using knowledge of optimizations to design and predict de-optimizations � We have been studying the Opteron in detail

Our project structure § For our implementation project: � We � will choose de-optimizations to implement We will choose algorithms that may best reflect our deoptimizations � We will implement the de-optimizations � We will report the results

Judging de-optimizations (de-ops) We need to decide on an overall metric for comparison � Whether the de-op affects scheduling, caching, branching, etc, its impact will be felt in the clocks needed to execute an algorithm. � So, our metric of choice will be CPU clock cycles

Judging de-optimizations (de-ops) With our metric, we can compare de-ops, but should we? � Inevitably, we will ask which de-ops had greater impact, i. e. caused the greatest jump in clocks. So, yes, we should � But this has to be done very carefully since an intended deop may not be the actual or full cause of a bump in clocks. It could be a side effect caused by the new code combination � Of course, this would be still be some kind of a de-op, just not the intended de-op

What does a de-op look like? q Definition: A de-op is a change to an optimal implementation of an algorithm that increases the clock cycles needed to execute the algorithm and that demonstrates some interesting fact about the CPU in question q Is an infinite loop a de-op? -- NO Why not? It tells us nothing about the hardware q Is a loop that executes more cycles than necessary a de-op? -- NO Again, it tells us nothing about the CPU q Is a combination of instructions that causes increased branch mispredictions a de-op? -- YES

General Areas of Focus q q Given some CPU, what aspects can we optimize code for? These aspects will be our focus for de-optimization. In general, when optimizing software, the following are the areas to focus on: § § q Instruction Fetching and Decoding Instruction Scheduling Instruction Type Usage (e. g. Integer vs. FP) Branch Prediction These will be our areas for de-optimization

Some General Findings § In class, when we discussed dynamic scheduling, for example, our team was not sanguine about being able to truly de-optimize code § In fact, we even imagined that our result may be that CPUs are now generally so good that true de-optimization is very difficult to achieve. In principle, we still believe this § In retrospect, we should have been more wise. Just like Plato’s Forms, there is a significant, if not absolute, difference between something imagined in the abstract and its worldly representation. There can be no perfect circles in the real world § Thus, in practice, as Gita has stressed, CPU designers made choices in their designs that were driven by cost, energy consumption, aesthetics, etc.

Some General Findings § These choices, when it comes time to write software for a CPU, become idiosyncrasies that must be accounted for when optimizing § For those writing optimal code, they are hassles that one must pay attention to § For our project team, these idiosyncrasies are potential "gold mines" for de-optimization § In fact, the AMD Opteron (K 10 architecture) exhibits a number of idiosyncrasies. You will see some these today

Examples of idiosyncrasies q AMD Opetron (K 10) q The dynamic scheduling pick window is 32 bytes length while instructions can be 1 - 16 bytes in length. So, scheduling can be adversely affected by instruction length q The branch target buffer (BTB) can only maintain 3 branch history entries per 16 bytes q Branch indicators are aligned at odd numbered positions within 16 byte code blocks. So, 1 -byte branches like return instructions, if misaligned will be miss predicted

Examples of idiosyncrasies q Intel i 7 (Nehalem) q The number of read ports for the register file is too small. This can result in stalls when reading registers q Instruction fetch/decode bandwidth is limited to 16 bytes per cycle. Instruction density can overwhelm the predecoder, which can only manage 6 instructions (per 16 bytes) per cycle

Format of the de-op discussion q In the upcoming discussion of de-optimization techniques, we will present. . . � . . . an area of the CPU that it derives from � . . . some, hopefully, illuminating title � . . . a general characterization of the de-op. This characterization may apply to many different CPU architectures. Generally, each of these represents a choice that may be made by a hardware designer � . . . a specific characterization of the de-op on the AMD Opteron. This characterization will apply only to the Opterons on Hydra

So, without further adieu. . . The De-optimizations

Instruction Fetching and Decoding q q Decoding Bandwidth Execution Latency

![Instruction Fetching and Decoding q Deoptimization 1 Decrease Decoding Bandwidth AMD 05 Scenario Instruction Fetching and Decoding q De-optimization #1 - Decrease Decoding Bandwidth [AMD 05] Scenario](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e0194d01fcddaa985a91ada93f4460c5/image-18.jpg)

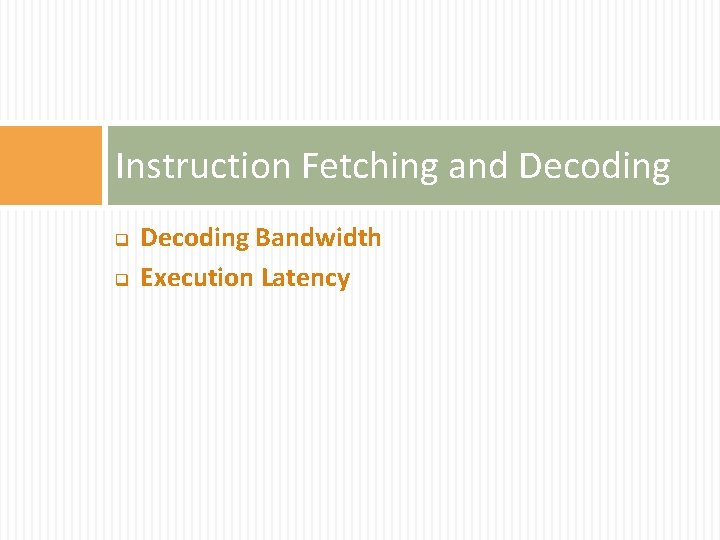

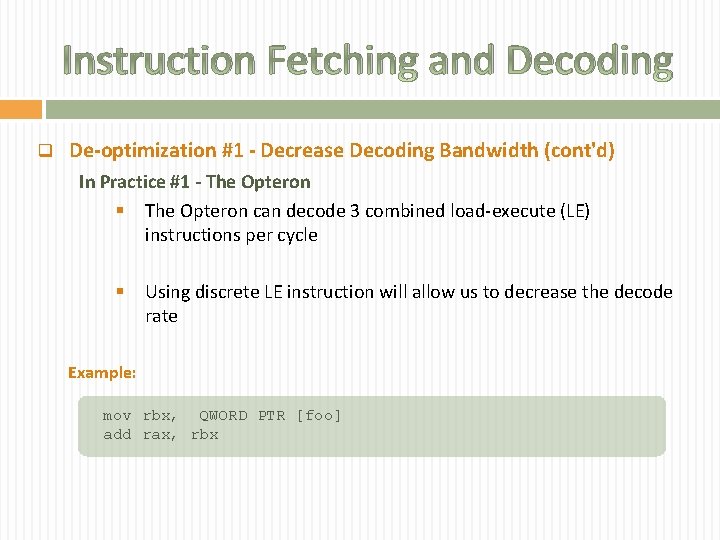

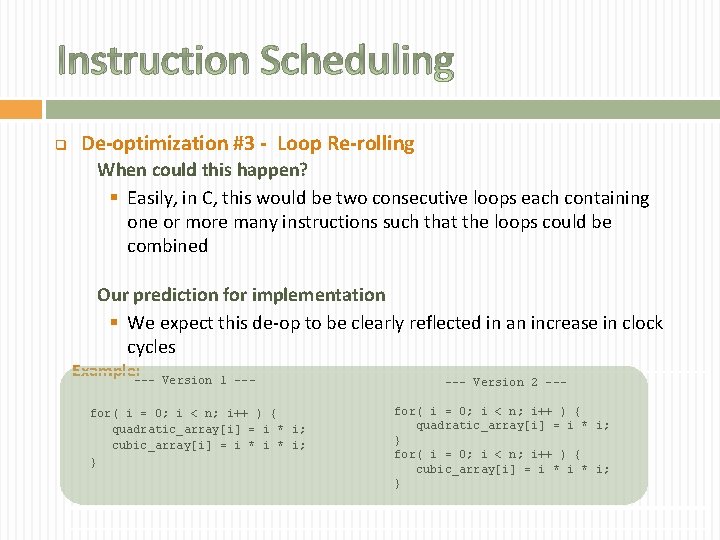

Instruction Fetching and Decoding q De-optimization #1 - Decrease Decoding Bandwidth [AMD 05] Scenario #1 § Many CISC architectures offer combined load and execute instructions as well as the typical discrete versions § Often, using the discrete versions can decrease the instruction decoding bandwidth Example: add rax, QWORD PTR [foo]

Instruction Fetching and Decoding q De-optimization #1 - Decrease Decoding Bandwidth (cont'd) In Practice #1 - The Opteron § The Opteron can decode 3 combined load-execute (LE) instructions per cycle § Using discrete LE instruction will allow us to decrease the decode rate Example: mov rbx, QWORD PTR [foo] add rax, rbx

Instruction Fetching and Decoding q De-optimization #1 - Decrease Decoding Bandwidth (cont'd) Scenario #2 § Use of instruction with longer encoding rather than those with shorter encoding to decrease the average decode rate by decreasing the number of instruction that can fit into the L 1 instruction cache § This also effectively “shrinks” the scheduling pick window § For example, use 32 -bit displacements instead of 8 -bit displacements and 2 -byte opcode form instead of 1 -byte opcode form of simple integer instructions

Instruction Fetching and Decoding q De-optimization #1 - Decrease Decoding Bandwidth (cont'd) In Practice #2 - The Opteron § The Opteron has short and long variants of a number of its instructions, like indirect add, for example. We can use the long variants of these instructions in order to drive down the decode rate § This will also have the affect of “shrinking” the Opteron’s 32 -byte pick window for instruction scheduling. Example of long variant: 81 C 0 78 56 34 12 83 C 3 FB FF FF FF 0 F 84 05 00 00 00 add eax, 12345678 h add ebx, -5 jz label 1 ; 2 -byte opcode form ; 32 -bit immediate value ; 2 -byte opcode, 32 -bit immediate ; value

Instruction Fetching and Decoding q De-optimization #1 - Decrease Decoding Bandwidth (cont'd) A balancing act § The scenarios for this de-optimization have flip sides that could make them difficult to implement § For example, scenario #1 describes using discrete load-execute instructions in order to decrease the average decode rate. However, sometimes discrete load-execute instructions are called for: § The discrete load-execute instructions can provide the scheduler with more flexibility when scheduling § In addition, on the Opteron, they consume less of the 32 -byte pick window, thereby giving the scheduler more options

Instruction Fetching and Decoding q De-optimization #1 - Decrease Decoding Bandwidth (cont'd) When could this happen? § This de-optimization could occur naturally when: q q A compiler does a very poor job The memory model forces long version encodings of instructions, e. g. 32 -bit displacements Our prediction for implementation § We predict mixed results when trying to implement this deoptimization

![Instruction Fetching and Decoding q Deoptimization 2 Increase execution latency AMD 05 Scenario Instruction Fetching and Decoding q De-optimization #2 - Increase execution latency [AMD 05] Scenario](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e0194d01fcddaa985a91ada93f4460c5/image-24.jpg)

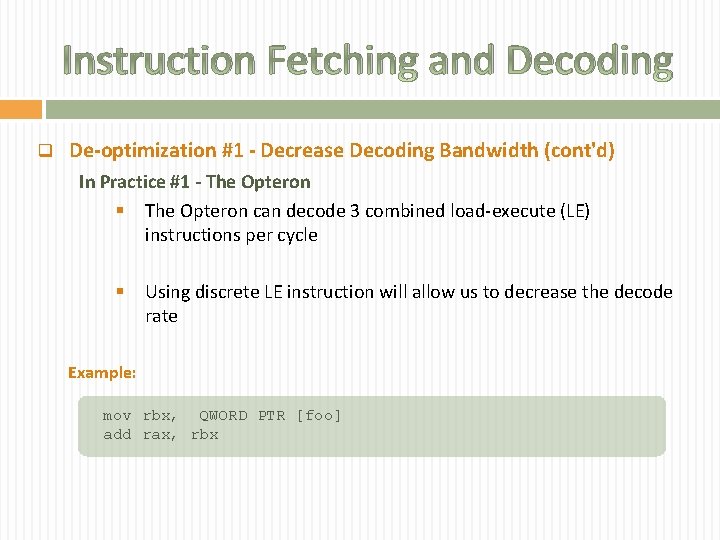

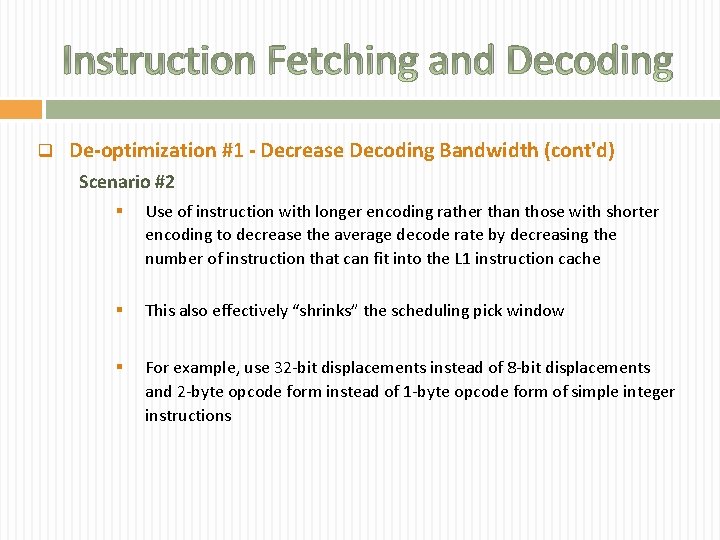

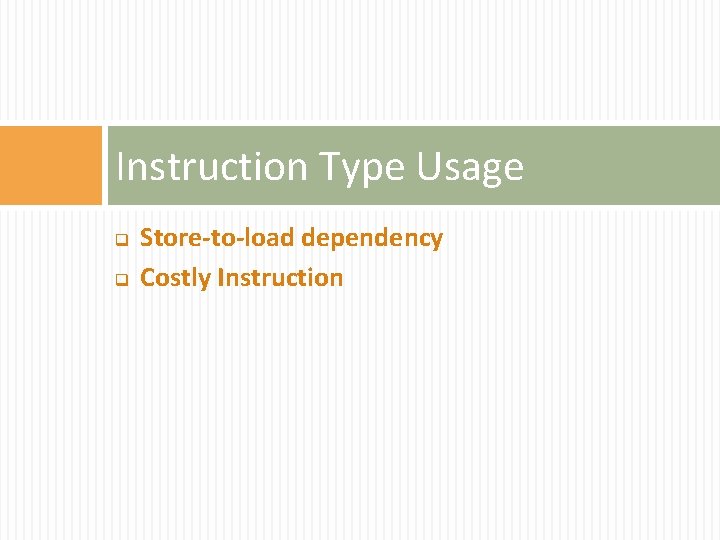

Instruction Fetching and Decoding q De-optimization #2 - Increase execution latency [AMD 05] Scenario § CPUs often have instructions that can perform almost the same operation § Yet, in spite of their seeming similarity, they have very different latencies. By choosing the high-latency version when the low latency version would suffice, code can be de-optimized

Instruction Fetching and Decoding q De-optimization #2 - Increase execution latency In Practice - The Opteron § We can use 16 -bit LEA instruction, which is a Vector. Path instruction to reduce the decode bandwidth and increase execution latency § The LOOP instruction on the Opteron has a latency of 8 cycles, while a test (like DEC) and jump (like JNZ) has a latency of less than 4 cycles § Therefore, substituting LOOP instructions for DEC/JNZ combinations will be a de-optimization.

Instruction Fetching and Decoding q De-optimization #2 - Increase execution latency (cont'd) When could this happen? § This de-optimization could occur if the user simply does the following: float a, b; b = a / 100. 0; instead of: float a, b; b = a * 0. 01 Our prediction for implementation § We expect this de-op to be clearly reflected in an increase in clock cycles

Instruction Scheduling q q q Address Generation interlocks Register Pressure Loop Re-rolling

![Instruction Scheduling q Deoptimization 1 Addressgeneration interlocks AMD 05 Scenario Scheduling loads Instruction Scheduling q De-optimization #1 - Address-generation interlocks [AMD 05] Scenario § Scheduling loads](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e0194d01fcddaa985a91ada93f4460c5/image-28.jpg)

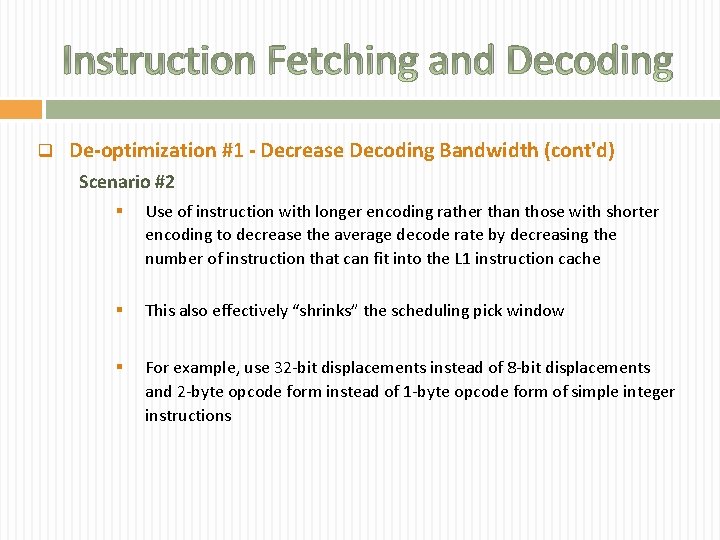

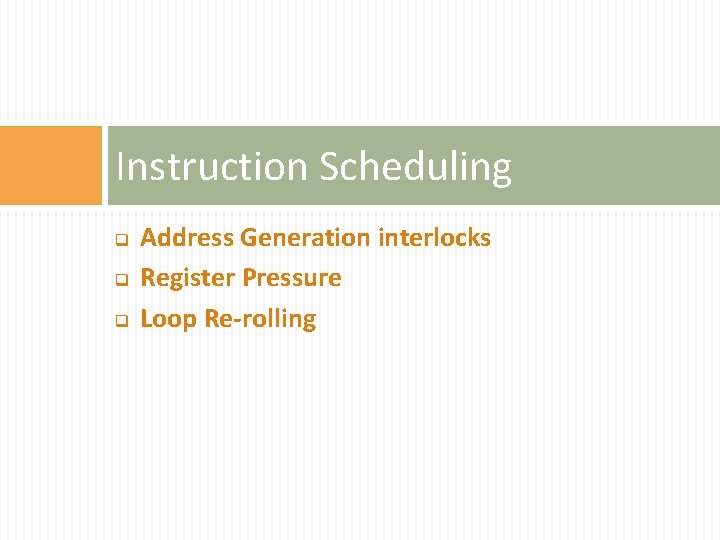

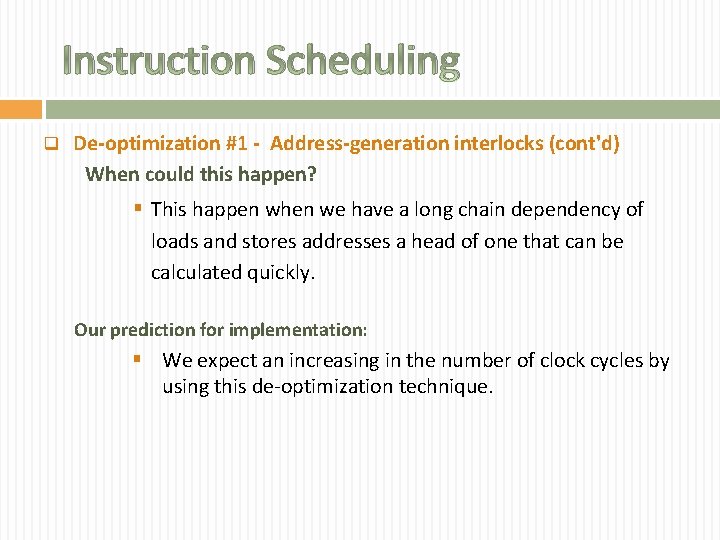

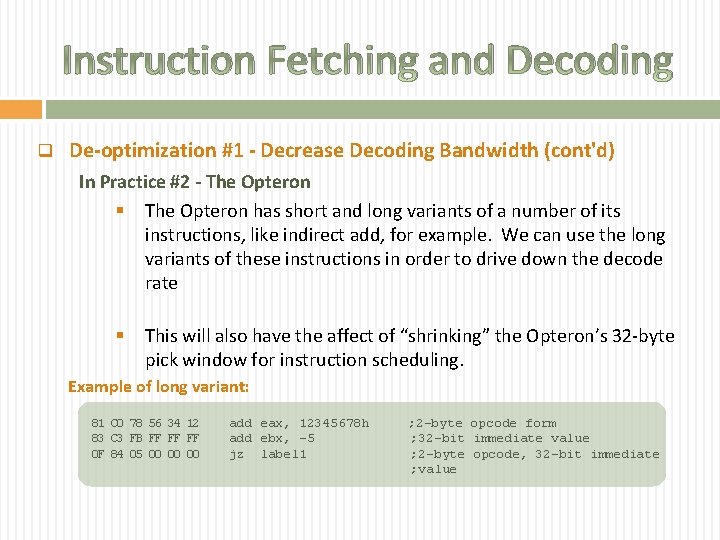

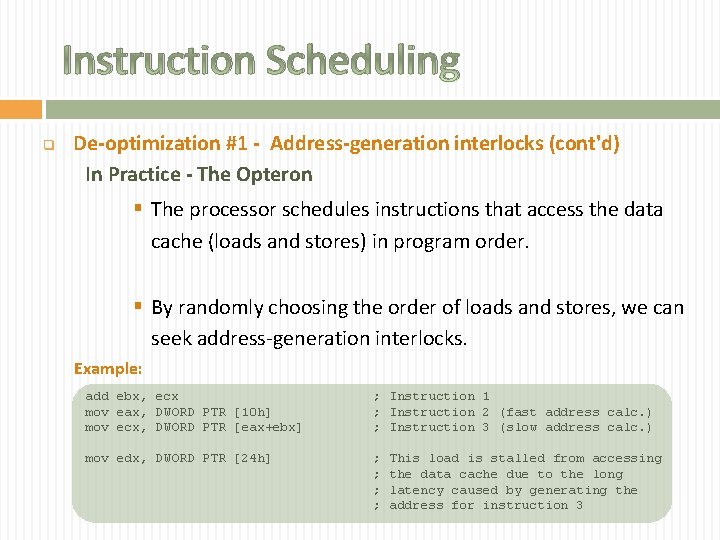

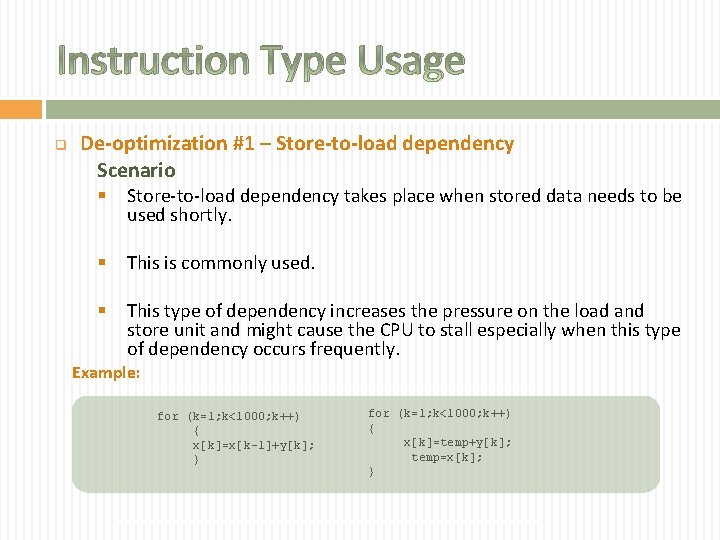

Instruction Scheduling q De-optimization #1 - Address-generation interlocks [AMD 05] Scenario § Scheduling loads and stores whose addresses cannot be calculated quickly ahead of loads and stores that require the declaration of a long dependency chain § In order to generate their addresses can create addressgeneration interlocks. Example: add ebx, ecx mov eax, DWORD PTR [10 h] mov edx, DWORD PTR [24 h] ; ; Instruction 1 Instruction 2 Place lode above instruction 3 to avoid AGI stall mov ecx, DWORD PTR [eax+ebx] ; Instruction 3

Instruction Scheduling q De-optimization #1 - Address-generation interlocks (cont'd) In Practice - The Opteron § The processor schedules instructions that access the data cache (loads and stores) in program order. § By randomly choosing the order of loads and stores, we can seek address-generation interlocks. Example: add ebx, ecx mov eax, DWORD PTR [10 h] mov ecx, DWORD PTR [eax+ebx] ; Instruction 1 ; Instruction 2 (fast address calc. ) ; Instruction 3 (slow address calc. ) mov edx, DWORD PTR [24 h] ; ; This load is stalled from accessing the data cache due to the long latency caused by generating the address for instruction 3

Instruction Scheduling q De-optimization #1 - Address-generation interlocks (cont'd) When could this happen? § This happen when we have a long chain dependency of loads and stores addresses a head of one that can be calculated quickly. Our prediction for implementation: § We expect an increasing in the number of clock cycles by using this de-optimization technique.

![Instruction Scheduling q Deoptimization 2 Increase register pressure AMD 05 Scenario Avoid Instruction Scheduling q De-optimization #2 - Increase register pressure [AMD 05] Scenario § Avoid](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e0194d01fcddaa985a91ada93f4460c5/image-31.jpg)

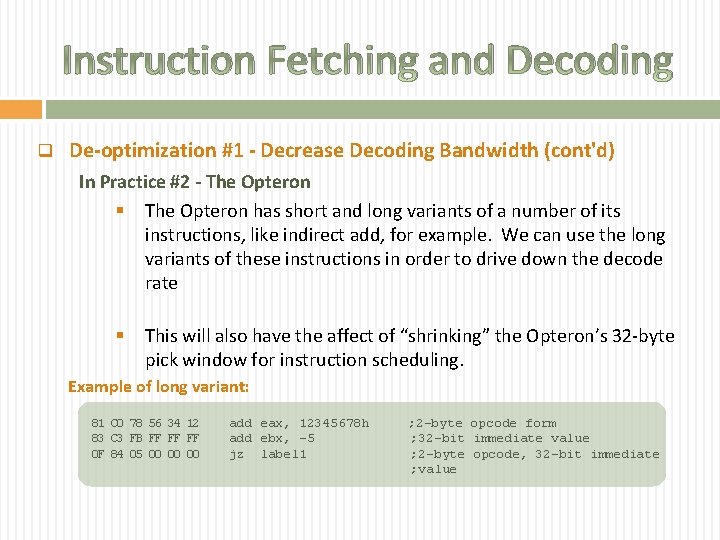

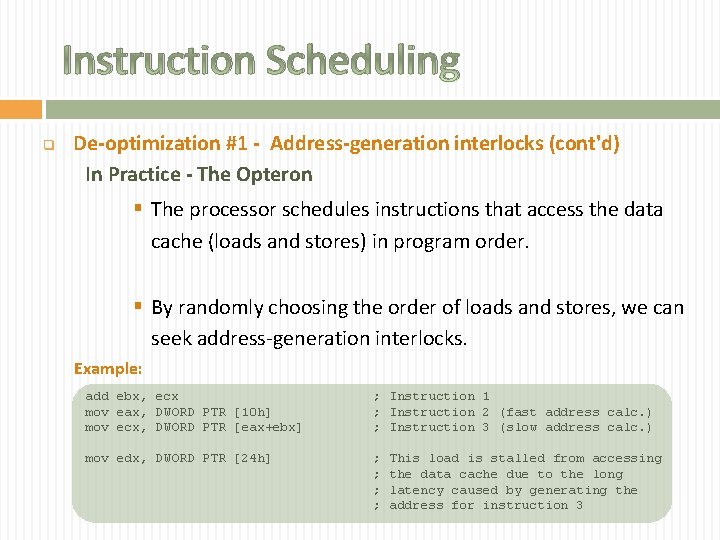

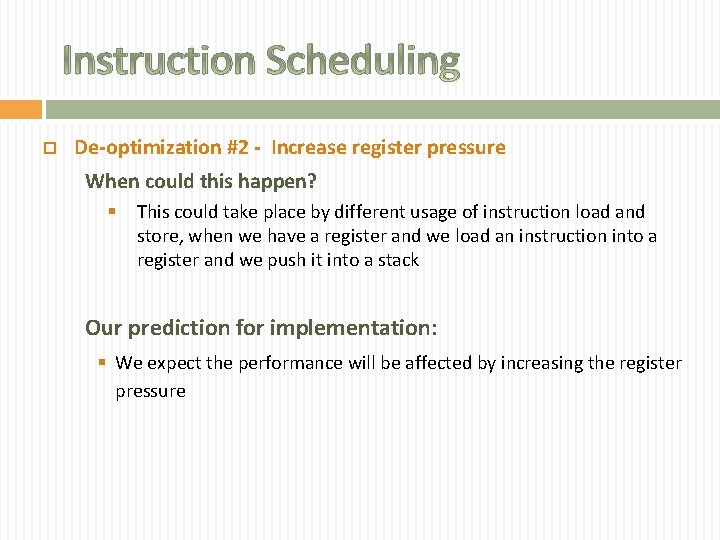

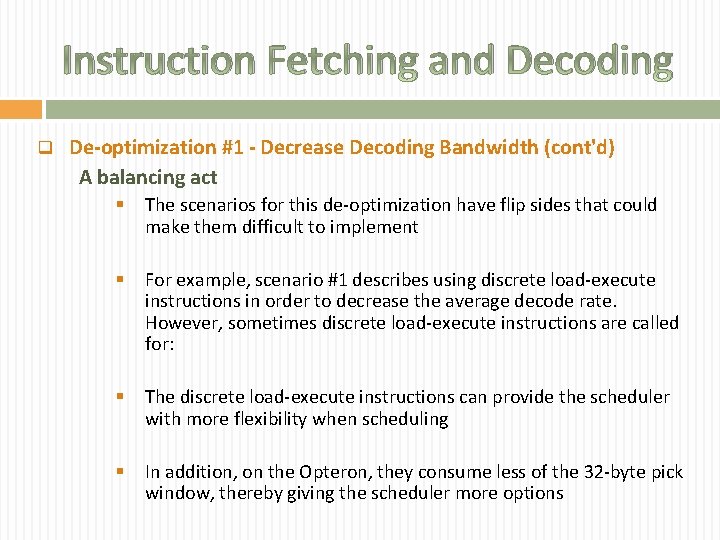

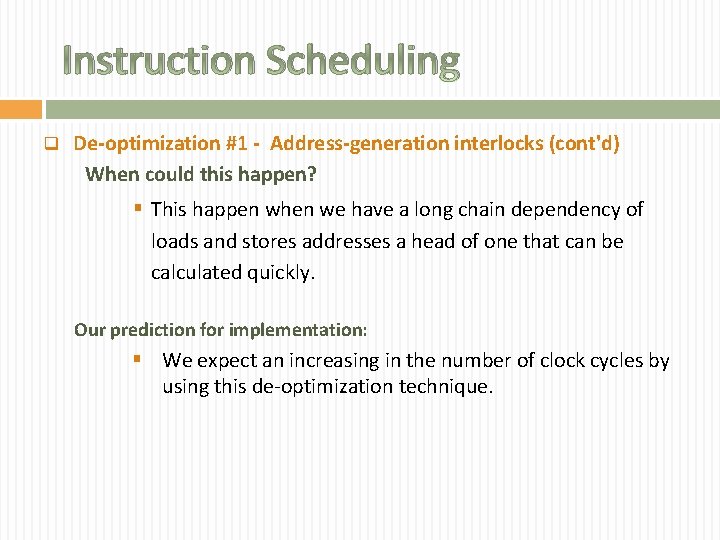

Instruction Scheduling q De-optimization #2 - Increase register pressure [AMD 05] Scenario § Avoid pushing memory data directly onto the stack and instead load it into a register to increase register pressure and create data dependencies. Example: push mem In Practice - The Opteron § Permit code that first loads the memory data into a register and then pushes it into the stack to increase register pressure and allows data dependencies. Example: mov rax, mem push rax

Instruction Scheduling De-optimization #2 - Increase register pressure When could this happen? § This could take place by different usage of instruction load and store, when we have a register and we load an instruction into a register and we push it into a stack Our prediction for implementation: § We expect the performance will be affected by increasing the register pressure

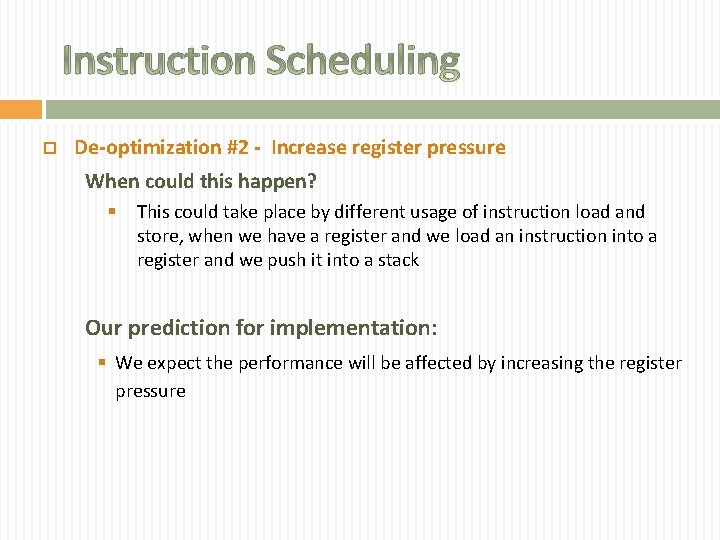

Instruction Scheduling q De-optimization #3 - Loop Re-rolling Scenario § Loops not only affect branch prediction. They can also affect dynamic scheduling § How ? § Let instructions 1 and 2 be within loops A and B, respectively. 1 and 2 could be part of a unified loop. If they were, then they could be scheduled together. Yet, they are separate and cannot be In Practice - The Opteron § Given that the Opteron is 3 -way scalar, this de-optimization could significantly reduce IPC

Instruction Scheduling q De-optimization #3 - Loop Re-rolling When could this happen? § Easily, in C, this would be two consecutive loops each containing one or more many instructions such that the loops could be combined Our prediction for implementation § We expect this de-op to be clearly reflected in an increase in clock cycles Example: --- Version 1 --- for( i = 0; i < n; i++ ) { quadratic_array[i] = i * i; cubic_array[i] = i * i; } --- Version 2 --for( i = 0; i < n; i++ ) { quadratic_array[i] = i * i; } for( i = 0; i < n; i++ ) { cubic_array[i] = i * i; }

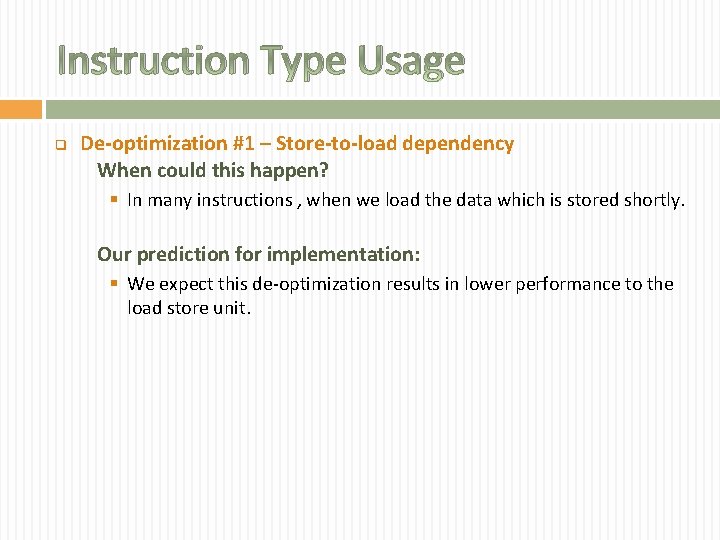

Instruction Type Usage q q Store-to-load dependency Costly Instruction

Instruction Type Usage q De-optimization #1 – Store-to-load dependency Scenario § Store-to-load dependency takes place when stored data needs to be used shortly. § This is commonly used. § This type of dependency increases the pressure on the load and store unit and might cause the CPU to stall especially when this type of dependency occurs frequently. Example: for (k=1; k<1000; k++) { x[k]=x[k-1]+y[k]; } for (k=1; k<1000; k++) { x[k]=temp+y[k]; temp=x[k]; }

Instruction Type Usage q De-optimization #1 – Store-to-load dependency When could this happen? § In many instructions , when we load the data which is stored shortly. Our prediction for implementation: § We expect this de-optimization results in lower performance to the load store unit.

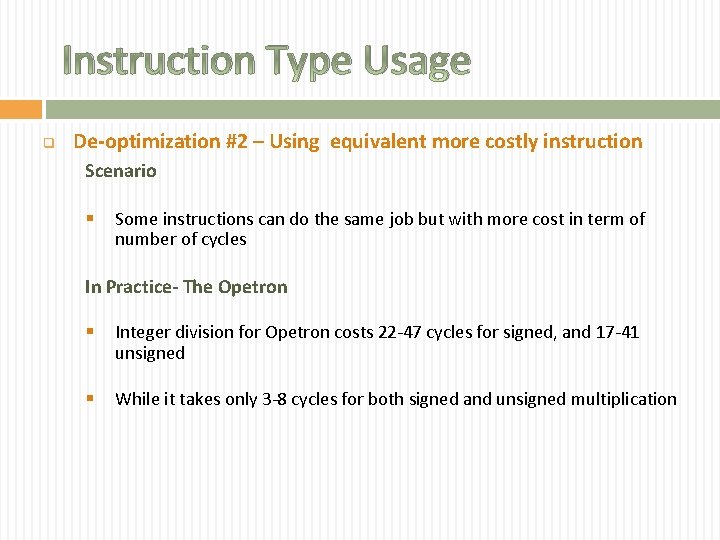

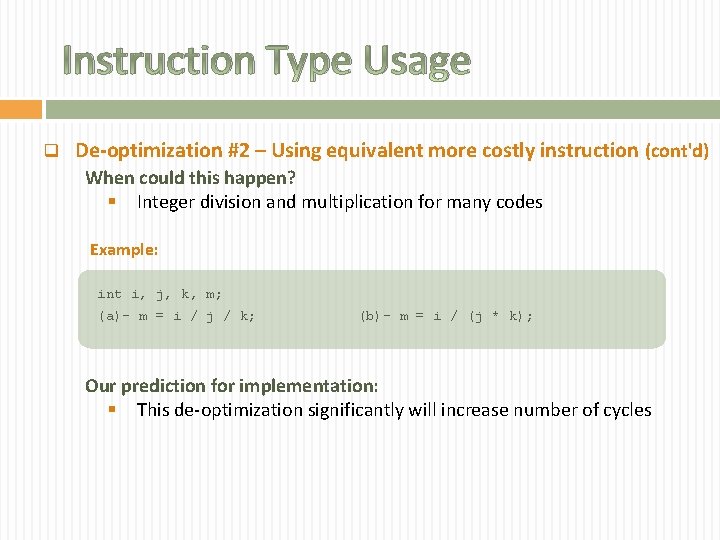

Instruction Type Usage q De-optimization #2 – Using equivalent more costly instruction Scenario § Some instructions can do the same job but with more cost in term of number of cycles In Practice- The Opetron § Integer division for Opetron costs 22 -47 cycles for signed, and 17 -41 unsigned § While it takes only 3 -8 cycles for both signed and unsigned multiplication

Instruction Type Usage q De-optimization #2 – Using equivalent more costly instruction (cont'd) When could this happen? § Integer division and multiplication for many codes Example: int i, j, k, m; (a)- m = i / j / k; (b)- m = i / (j * k); Our prediction for implementation: § This de-optimization significantly will increase number of cycles

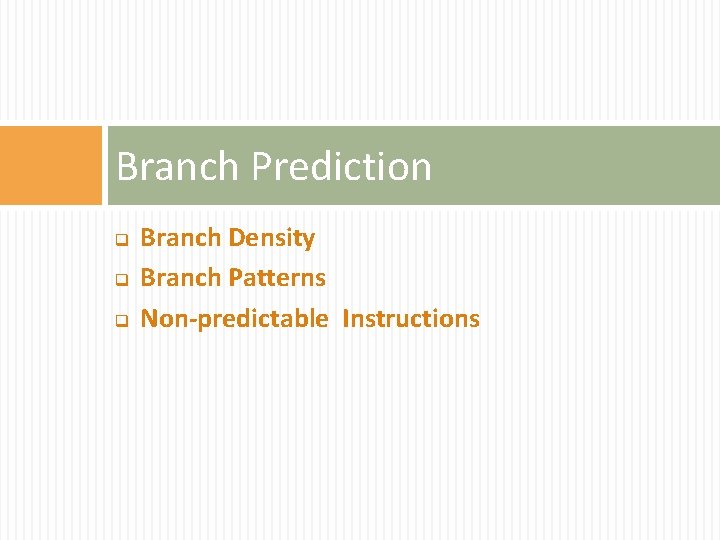

Branch Prediction q q q Branch Density Branch Patterns Non-predictable Instructions

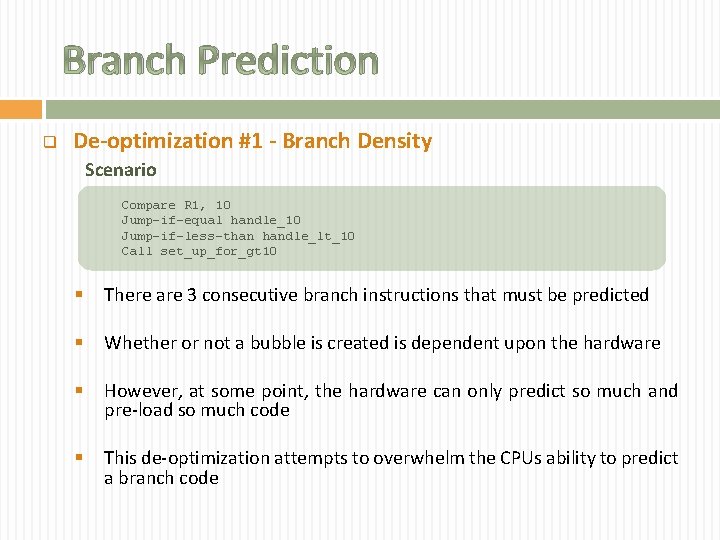

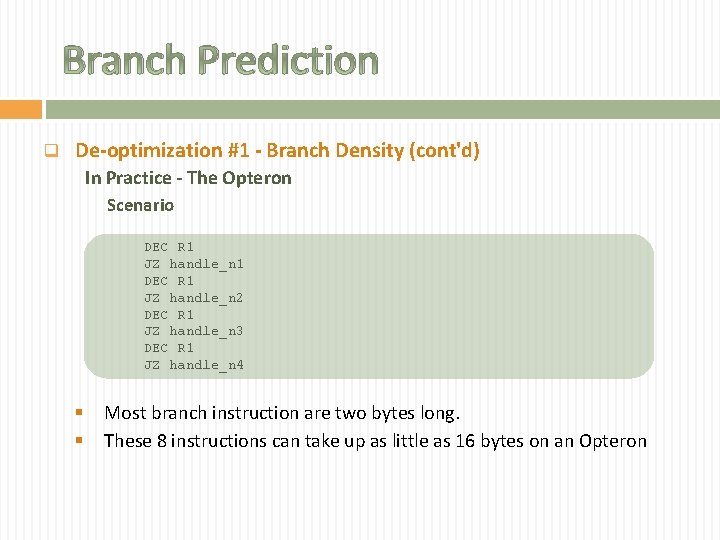

Branch Prediction q De-optimization #1 - Branch Density Scenario Compare R 1, 10 Jump-if-equal handle_10 Jump-if-less-than handle_lt_10 Call set_up_for_gt 10 § There are 3 consecutive branch instructions that must be predicted § Whether or not a bubble is created is dependent upon the hardware § However, at some point, the hardware can only predict so much and pre-load so much code § This de-optimization attempts to overwhelm the CPUs ability to predict a branch code

Branch Prediction q De-optimization #1 - Branch Density (cont'd) In Practice - The Opteron Scenario DEC R 1 JZ handle_n 1 DEC R 1 JZ handle_n 2 DEC R 1 JZ handle_n 3 DEC R 1 JZ handle_n 4 § § Most branch instruction are two bytes long. These 8 instructions can take up as little as 16 bytes on an Opteron

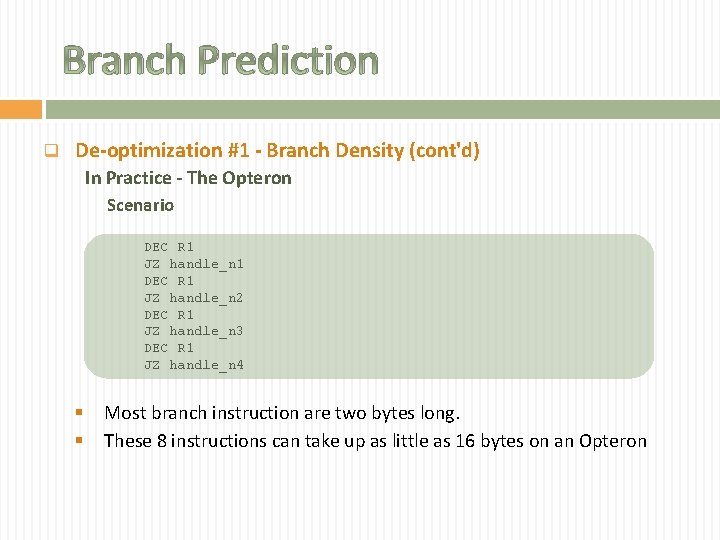

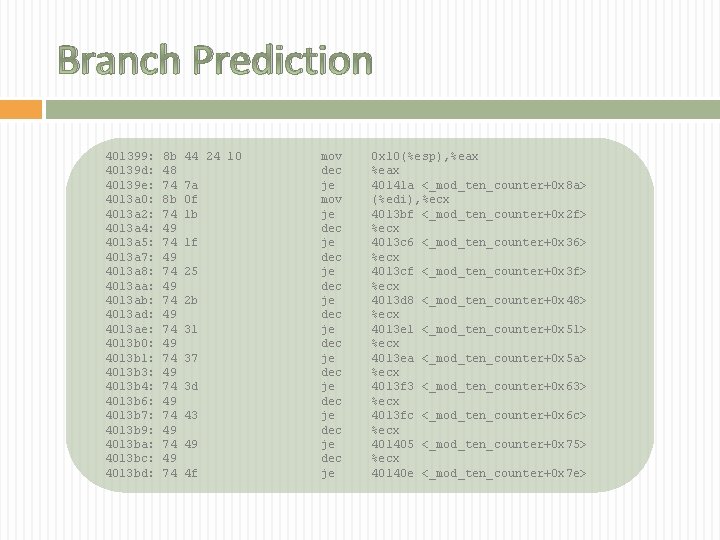

Branch Prediction 401399: 40139 d: 40139 e: 4013 a 0: 4013 a 2: 4013 a 4: 4013 a 5: 4013 a 7: 4013 a 8: 4013 aa: 4013 ab: 4013 ad: 4013 ae: 4013 b 0: 4013 b 1: 4013 b 3: 4013 b 4: 4013 b 6: 4013 b 7: 4013 b 9: 4013 ba: 4013 bc: 4013 bd: 8 b 48 74 8 b 74 49 74 49 74 49 74 44 24 10 7 a 0 f 1 b 1 f 25 2 b 31 37 3 d 43 49 4 f mov dec je mov je dec je dec je dec je 0 x 10(%esp), %eax 40141 a <_mod_ten_counter+0 x 8 a> (%edi), %ecx 4013 bf <_mod_ten_counter+0 x 2 f> %ecx 4013 c 6 <_mod_ten_counter+0 x 36> %ecx 4013 cf <_mod_ten_counter+0 x 3 f> %ecx 4013 d 8 <_mod_ten_counter+0 x 48> %ecx 4013 e 1 <_mod_ten_counter+0 x 51> %ecx 4013 ea <_mod_ten_counter+0 x 5 a> %ecx 4013 f 3 <_mod_ten_counter+0 x 63> %ecx 4013 fc <_mod_ten_counter+0 x 6 c> %ecx 401405 <_mod_ten_counter+0 x 75> %ecx 40140 e <_mod_ten_counter+0 x 7 e>

Branch Prediction q De-optimization #1 - Branch Density (cont'd) In Practice - The Opteron § However, the Opteron's BTB (Branch Target Buffer) can only maintain 3 (used) branch entries per (aligned) 16 bytes of code [AMD 05] § Thus, the Opteron cannot successfully maintain predictions for all of the branches within previous sequence of instructions § Why? 9 branch indicators associated with byte# 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, & 15 § Only 3 branch selectors

Branch Prediction q De-optimization #1 - Branch Density (cont'd) When could this happen? § Having dense branches is not that unusual. Most compilers translate case/switch statement to a comparison chain, which is implemented as dec/jz instruction. Our prediction for implementation § By seeking dense branches we expect the branch prediction unit to have more mispredictions.

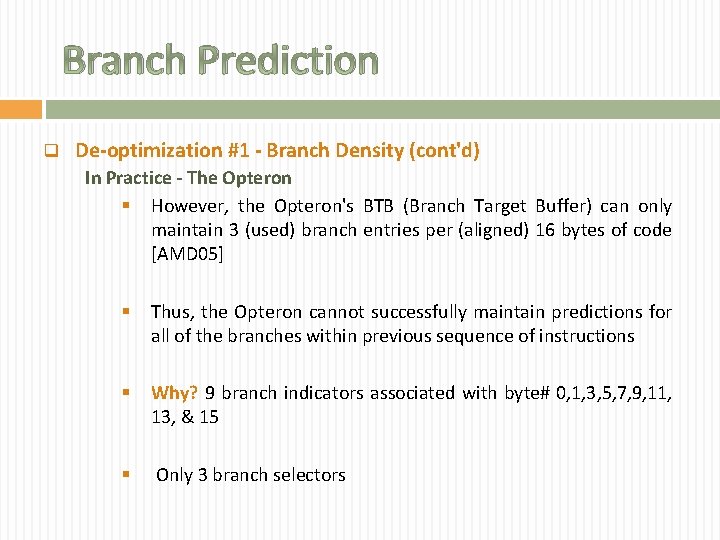

Branch Prediction q De-optimization #2 - Branch Patterns Scenario Consider the following algorithm: Algorithm Even-Number-Sieve § Input: An array of random numbers § Output: An array of numbers where the odd numbers have been replaced with zero § Even-Number-Sieve must have a branch within that depends upon whether the current array entry is even or odd § Given an even probability distribution, there will be no pattern that can be selected that will yield better than 50% success

Branch Prediction q De-optimization #2 - Branch Patterns § Let the word “parity” refer to a branch that has an even chance of being taken as not taken § The Odd/Even branch within Even-Number-Sieve has parity § Furthermore, it has no simple pattern that can be predicted § Yet, data need not be random. All we need is a pattern whose repetition outstrips the hardware bits used to predict it § In fact, given the right pattern, branch prediction can be forced to perform with a success rate well less than 50%

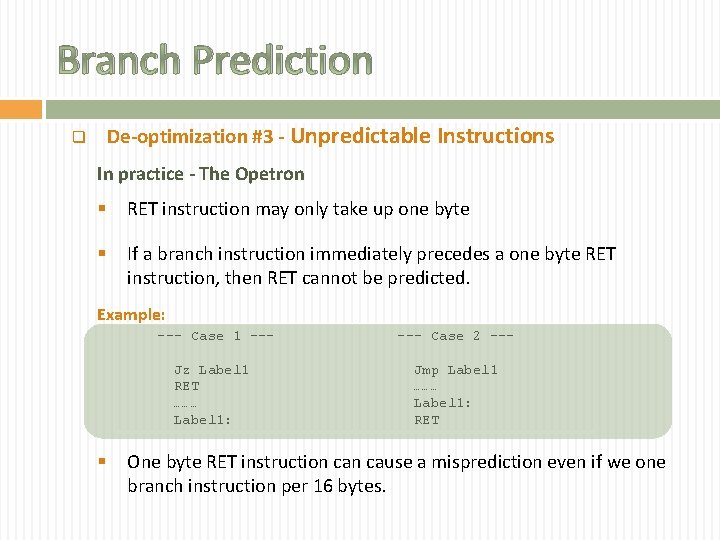

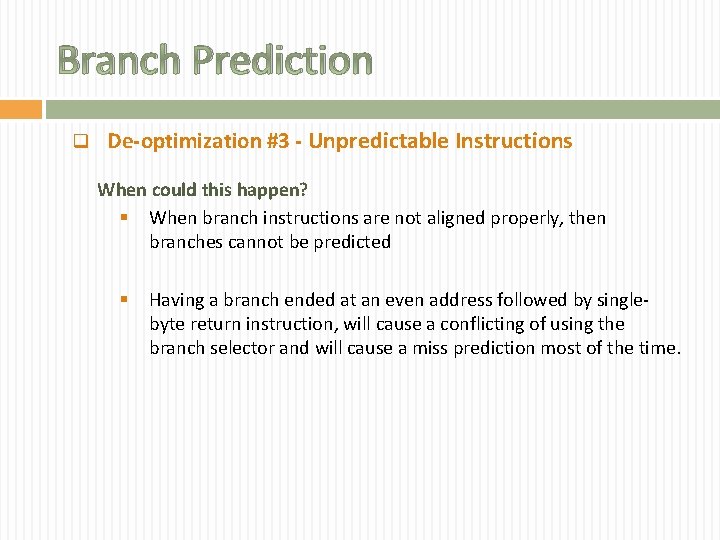

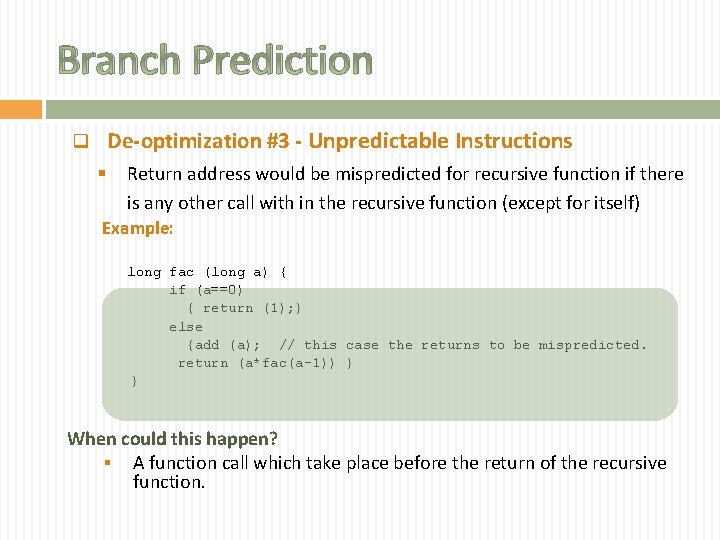

Branch Prediction q De-optimization #3 - Unpredictable Instructions Scenario § Some CPUs restricts only one branch instruction be within a certain number bytes § If this exceeded or if branch instructions are not aligned properly, then branches cannot be predicted § Misprediction can take place with undesirable usage of recursion [AMD 05] § Far control transfer usually mispredicted for different types of architecture

Branch Prediction q De-optimization #3 - Unpredictable Instructions In practice - The Opetron § RET instruction may only take up one byte § If a branch instruction immediately precedes a one byte RET instruction, then RET cannot be predicted. Example: --- Case 1 --Jz Label 1 RET ……… Label 1: § --- Case 2 --Jmp Label 1 ……… Label 1: RET One byte RET instruction cause a misprediction even if we one branch instruction per 16 bytes.

Branch Prediction q De-optimization #3 - Unpredictable Instructions When could this happen? § When branch instructions are not aligned properly, then branches cannot be predicted § Having a branch ended at an even address followed by singlebyte return instruction, will cause a conflicting of using the branch selector and will cause a miss prediction most of the time.

Branch Prediction De-optimization #3 - Unpredictable Instructions q § Return address would be mispredicted for recursive function if there is any other call with in the recursive function (except for itself) Example: long fac (long a) { if (a==0) { return (1); } else {add (a); // this case the returns to be mispredicted. return (a*fac(a-1)) } } When could this happen? § A function call which take place before the return of the recursive function.

Branch Prediction q De-optimization #3 - Unpredictable Instructions Our prediction for implementation § We expect this de-op technique to have a real affect on the performance in term of increasing the number of misprediction § Minimum penalty of misprediction for Opetron is 10 cycles [AMD 11]

Conclusion q Whether based on cost or some other reason, the decisions made by CPU designers introduced many idiosyncrasies into various CPU designs q As we’ve shown, these idiosyncrasies offer manifest opportunities to de-optimize software. All of this is in spite of how far abstract hardware design techniques, like dynamic scheduling, have come q So, like Plato’s circle, the difference between the abstract and the concrete is significant q By examining these idiosyncrasies as de-optimizations, you’ve seen that ignoring hardware is to be done at your peril…or you’d better have a fantastic compiler

Conclusion q In the next phase, we will show the practical effects of ignoring hardware q We will show that some of these de-optimizations have teeth

![References AMD 05 AMD 64 Technology Software Optimization Guide for AMD 64 Processors 2005 References: [AMD 05] AMD 64 Technology. Software Optimization Guide for AMD 64 Processors, 2005](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e0194d01fcddaa985a91ada93f4460c5/image-55.jpg)

References: [AMD 05] AMD 64 Technology. Software Optimization Guide for AMD 64 Processors, 2005 [AMD 11] AMD 64 Technology. AMD 64 Architecture Programmers Manual, Volume 1: Application Programming. 2011 [AMD 11] AMD 64 Technology. AMD 64 Architecture Programmers Manual, Volume 2: System Programming. 2011 [AMD 11] AMD 64 Technology. AMD 64 Architecture Programmers Manual, Volume 3: General Purpose and System Instructions. 2011

Questions? Thank You