Declarative Computation Model Memory management Exceptions From kernel

![A complete example fun {Map Xs F} case Xs of nil then nil [] A complete example fun {Map Xs F} case Xs of nil then nil []](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/b6dd12b283cc6e9c038c585b6557ba9c/image-17.jpg)

![Last call optimization ST: [ ({Loop 10 0}, E 0) ] proc {Loop 10 Last call optimization ST: [ ({Loop 10 0}, E 0) ] proc {Loop 10](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/b6dd12b283cc6e9c038c585b6557ba9c/image-20.jpg)

- Slides: 38

Declarative Computation Model Memory management, Exceptions, From kernel to practical language (2. 5 -2. 7) Carlos Varela RPI Adapted with permission from: Seif Haridi KTH Peter Van Roy UCL C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 1

From the kernel language to a practical language • Interactive interface – the declare statement and the global environment • Extend kernel syntax to give a full, practical syntax – – – nesting of partial values implicit variable initialization expressions nesting the if and case statements andthen and orelse operations • Linguistic abstraction – functions C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 2

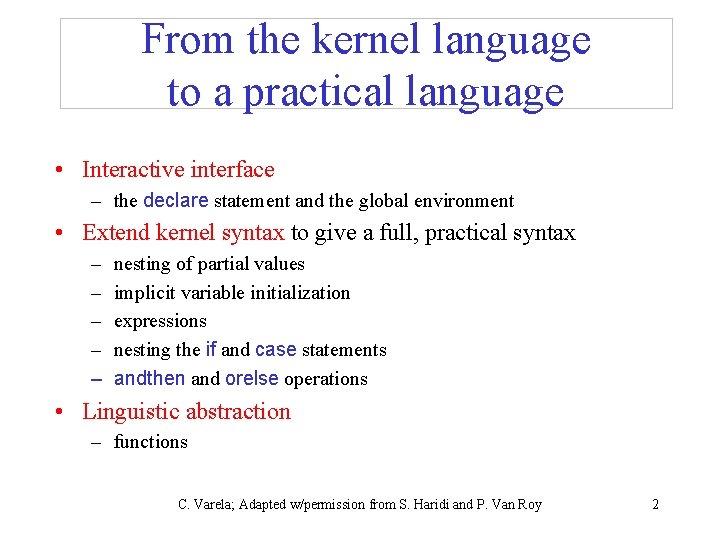

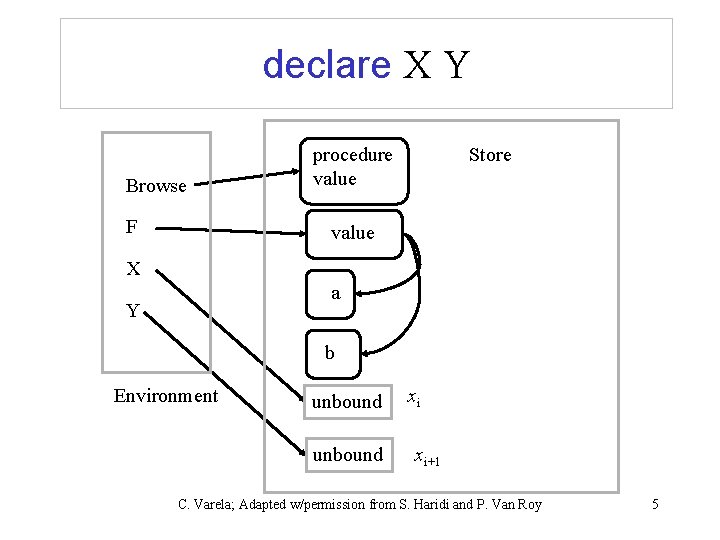

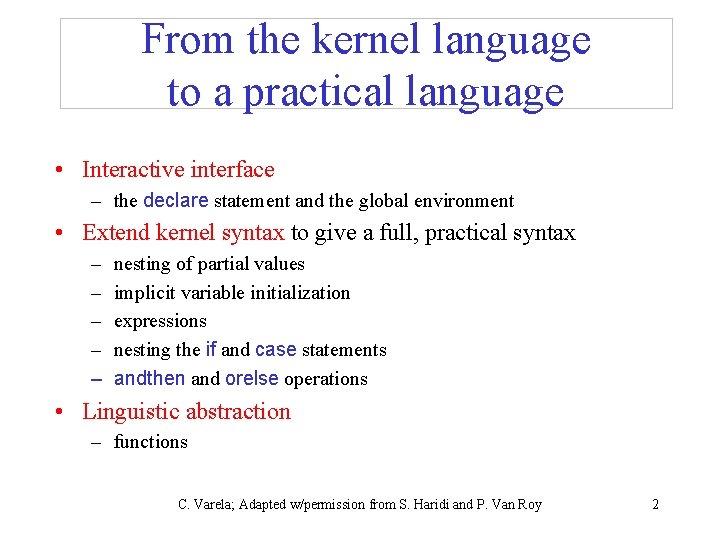

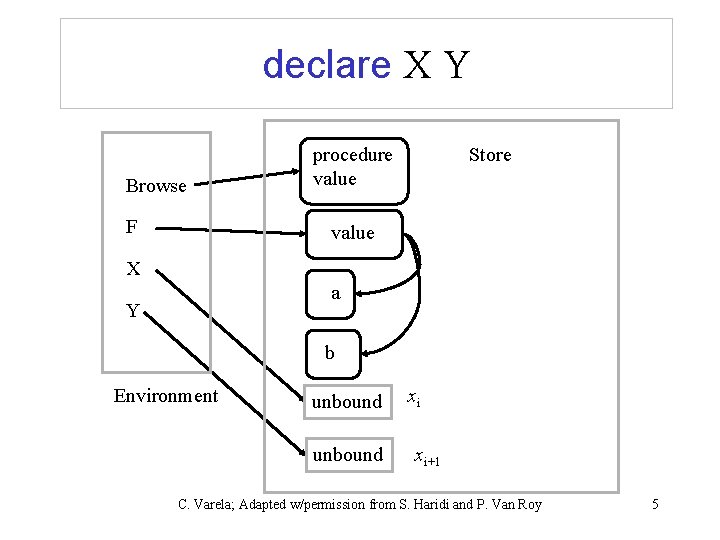

The interactive interface (declare) • The interactive interface is a program that has a single global environment declare X Y • Augments (and overrides) the environment with new mappings for X and Y {Browse X} • Inspects the store and shows partial values, and incremental changes C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 3

The interactive interface (declare) Browse procedure value Store F value X Y a b Environment C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 4

declare X Y Browse F procedure value Store value X a Y b Environment unbound xi xi+1 C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 5

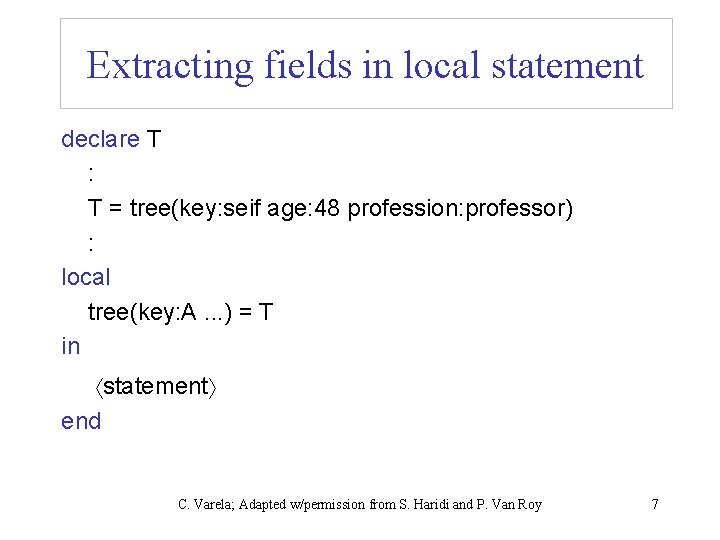

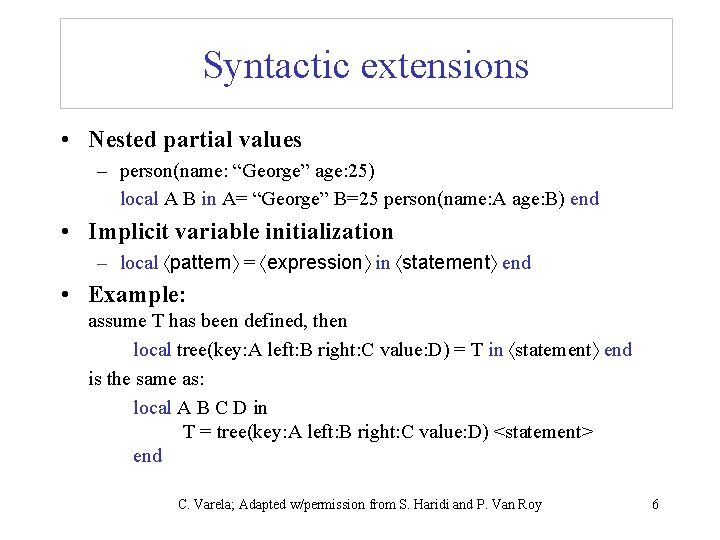

Syntactic extensions • Nested partial values – person(name: “George” age: 25) local A B in A= “George” B=25 person(name: A age: B) end • Implicit variable initialization – local pattern = expression in statement end • Example: assume T has been defined, then local tree(key: A left: B right: C value: D) = T in statement end is the same as: local A B C D in T = tree(key: A left: B right: C value: D) <statement> end C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 6

Extracting fields in local statement declare T : T = tree(key: seif age: 48 profession: professor) : local tree(key: A. . . ) = T in statement end C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 7

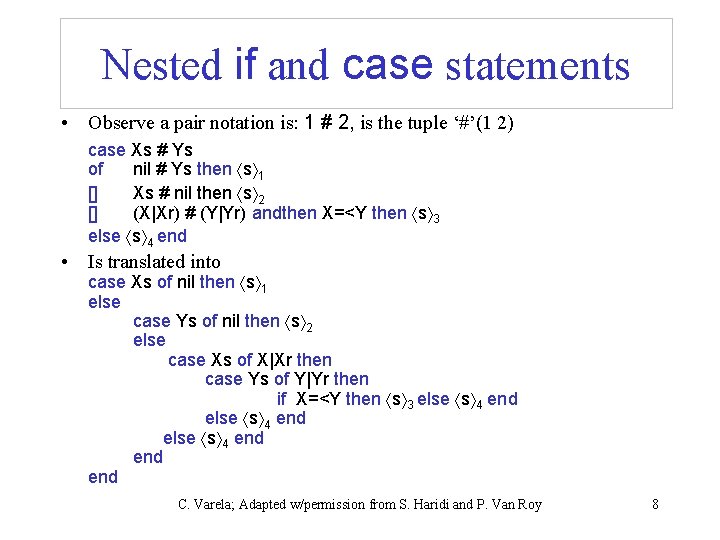

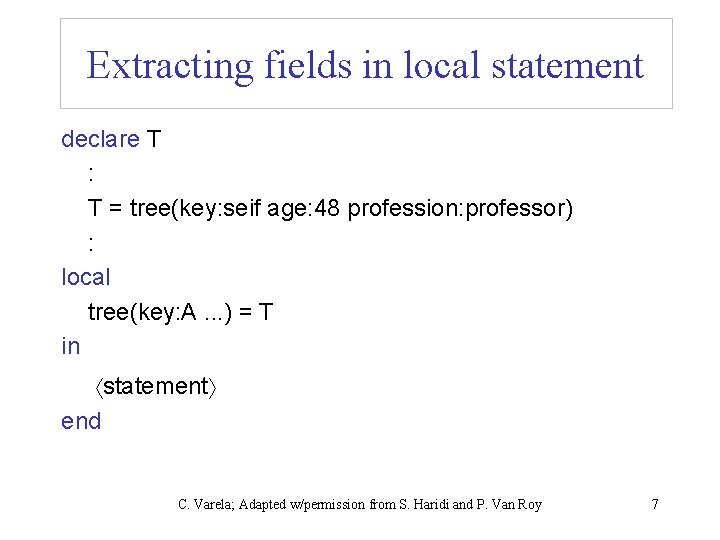

Nested if and case statements • Observe a pair notation is: 1 # 2, is the tuple ‘#’(1 2) case Xs # Ys of nil # Ys then s 1 [] Xs # nil then s 2 [] (X|Xr) # (Y|Yr) andthen X=<Y then s 3 else s 4 end • Is translated into case Xs of nil then s 1 else case Ys of nil then s 2 else case Xs of X|Xr then case Ys of Y|Yr then if X=<Y then s 3 else s 4 end end C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 8

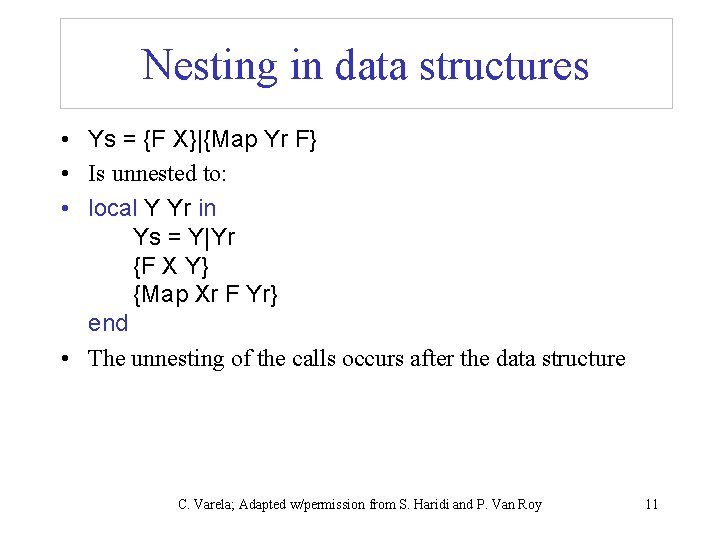

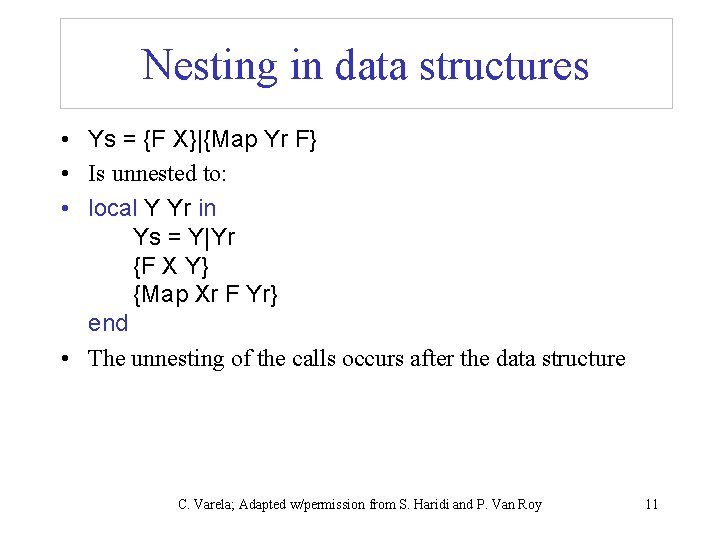

Expressions • An expression is a sequence of operations that returns a value • A statement is a sequence of operations that does not return a value. Its effect is on the store, or outside of the system (e. g. read/write a file) • 11*11 X=11*11 expression statement C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 9

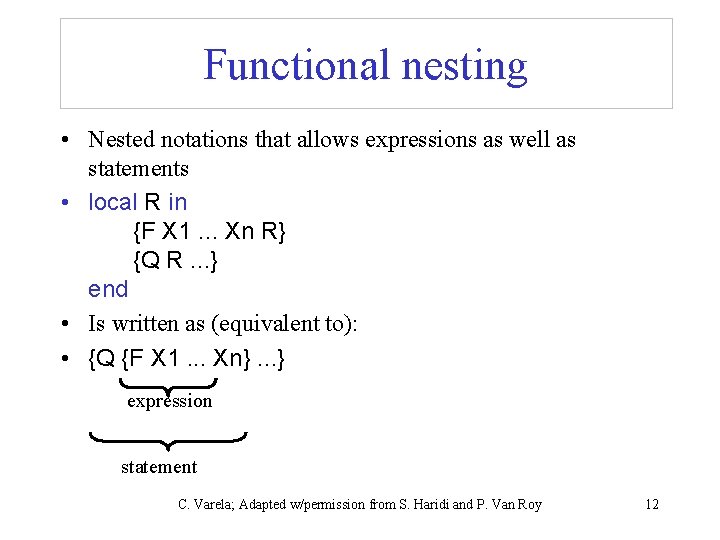

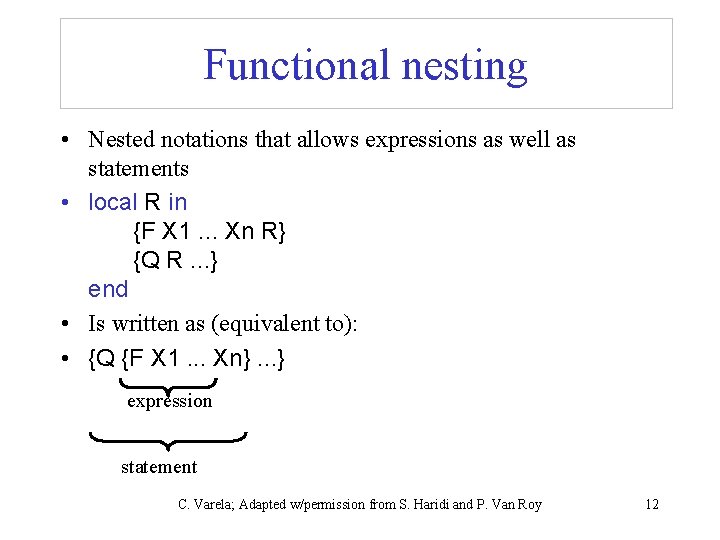

Functions as linguistic abstraction • {F X 1. . . Xn R} • R = {F X 1. . . Xn} fun {F X 1. . . Xn} statement expressio n end statemen t proc {F X 1. . . Xn R} statement R = expression end statemen t C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 10

Nesting in data structures • Ys = {F X}|{Map Yr F} • Is unnested to: • local Y Yr in Ys = Y|Yr {F X Y} {Map Xr F Yr} end • The unnesting of the calls occurs after the data structure C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 11

Functional nesting • Nested notations that allows expressions as well as statements • local R in {F X 1. . . Xn R} {Q R. . . } end • Is written as (equivalent to): • {Q {F X 1. . . Xn}. . . } expression statement C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 12

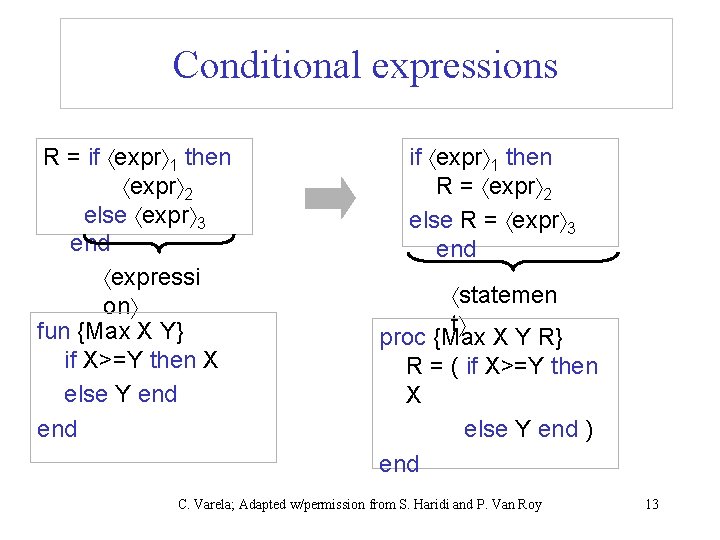

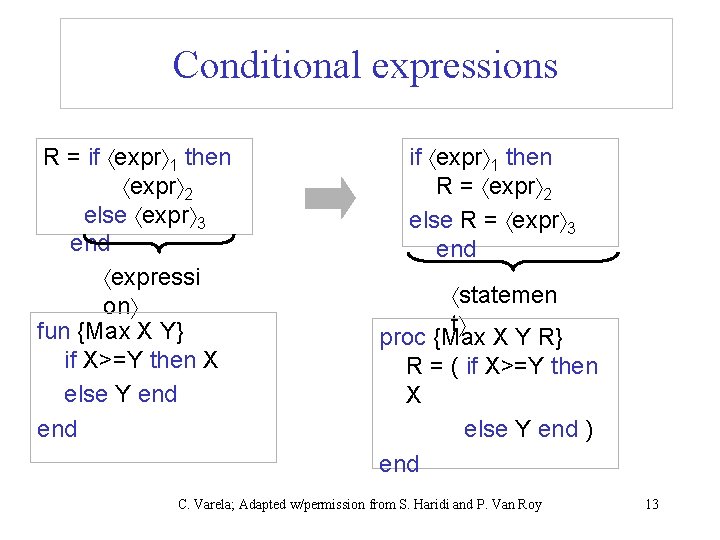

Conditional expressions R = if expr 1 then expr 2 else expr 3 end expressi on fun {Max X Y} if X>=Y then X else Y end if expr 1 then R = expr 2 else R = expr 3 end statemen t proc {Max X Y R} R = ( if X>=Y then X else Y end ) end C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 13

Example fun {Max X Y} if X>=Y then X else Y end proc {Max X Y R} R = ( if X>=Y then X else Y end ) end proc {Max X Y R} if X>=Y then R = X else R = Y end C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 14

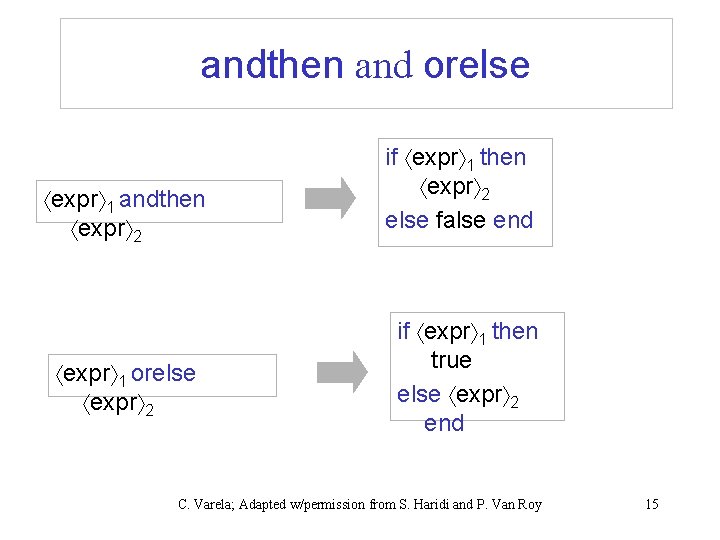

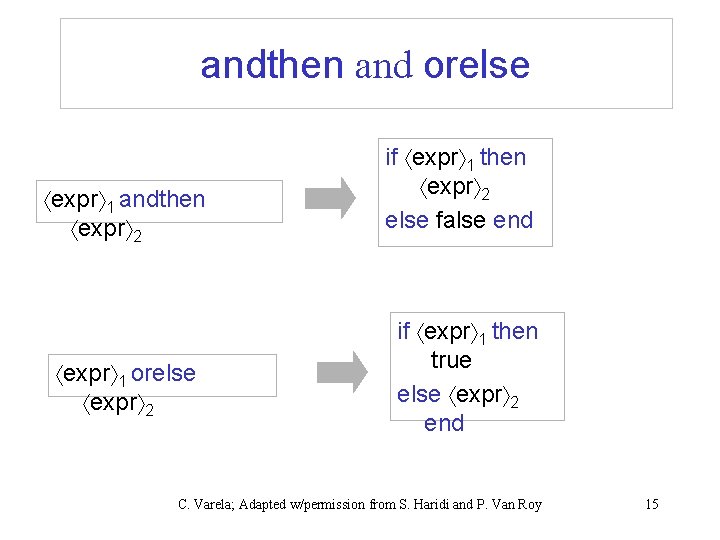

andthen and orelse expr 1 andthen expr 2 expr 1 orelse expr 2 if expr 1 then expr 2 else false end if expr 1 then true else expr 2 end C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 15

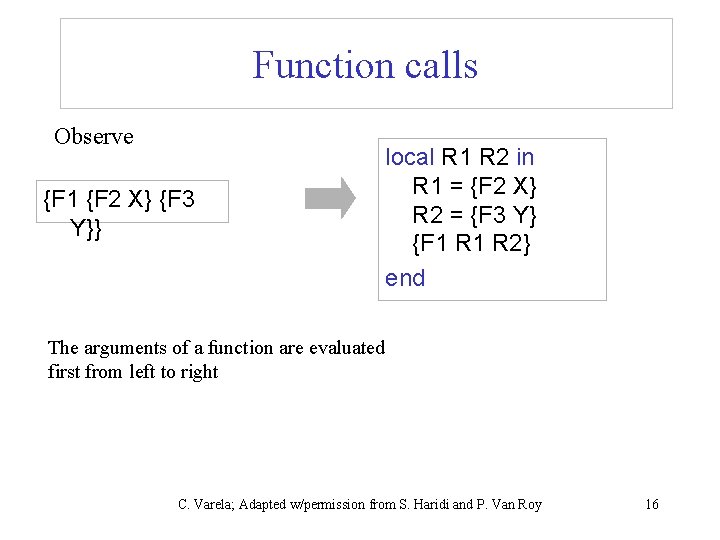

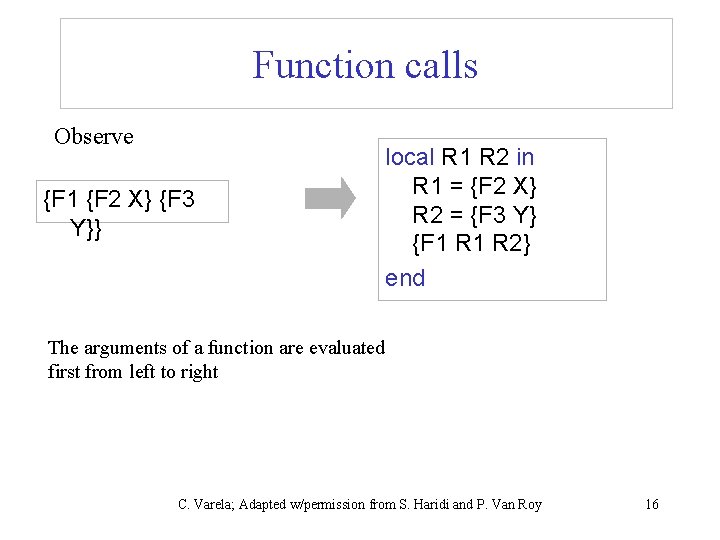

Function calls Observe {F 1 {F 2 X} {F 3 Y}} local R 1 R 2 in R 1 = {F 2 X} R 2 = {F 3 Y} {F 1 R 2} end The arguments of a function are evaluated first from left to right C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 16

![A complete example fun Map Xs F case Xs of nil then nil A complete example fun {Map Xs F} case Xs of nil then nil []](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/b6dd12b283cc6e9c038c585b6557ba9c/image-17.jpg)

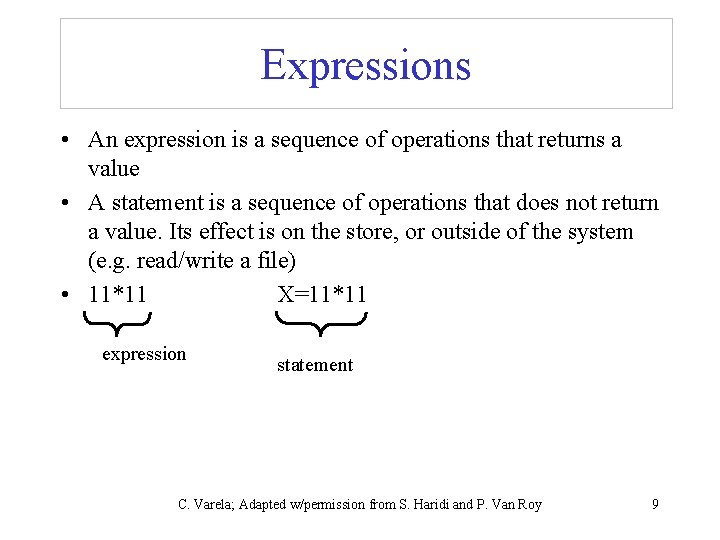

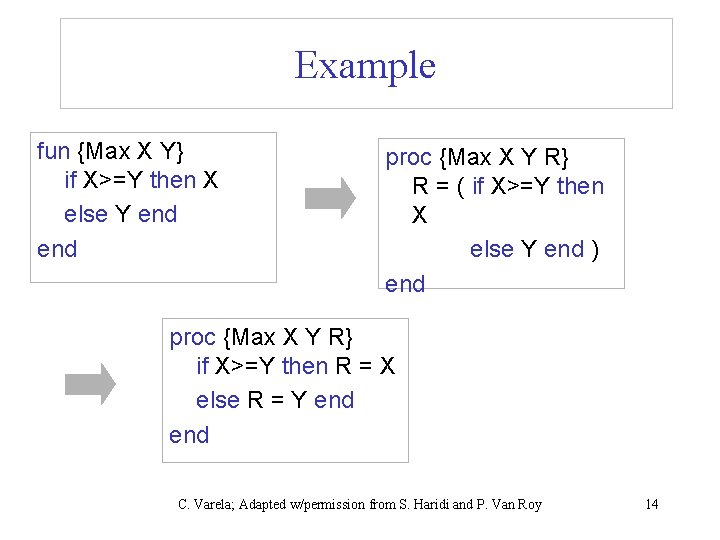

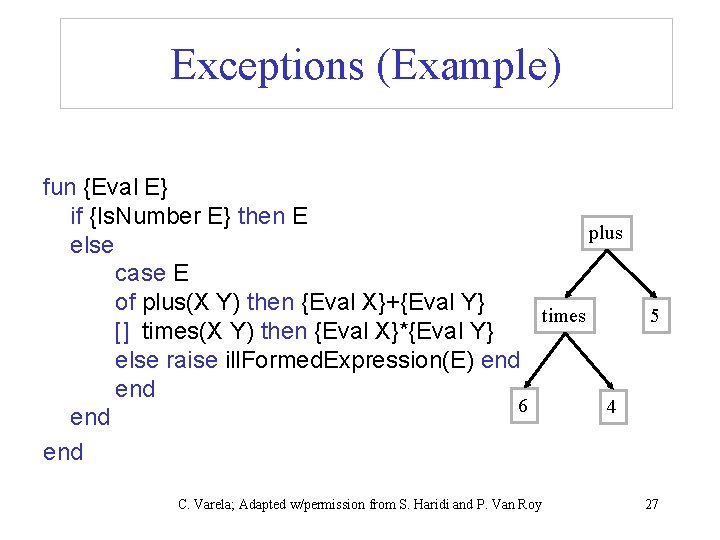

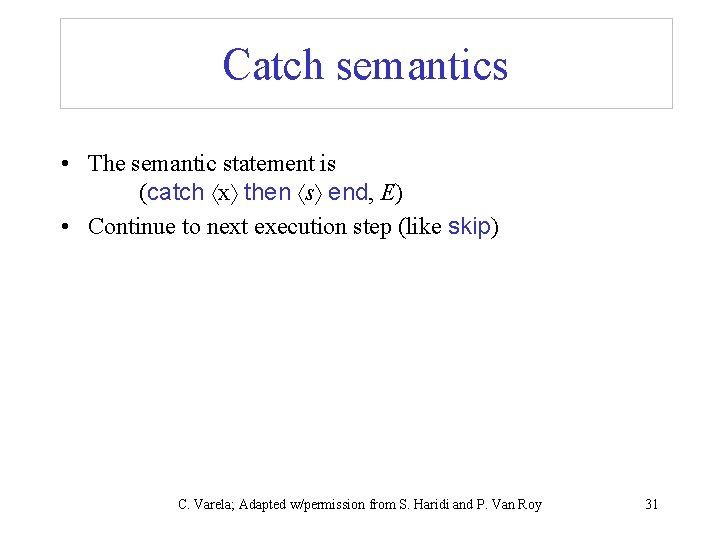

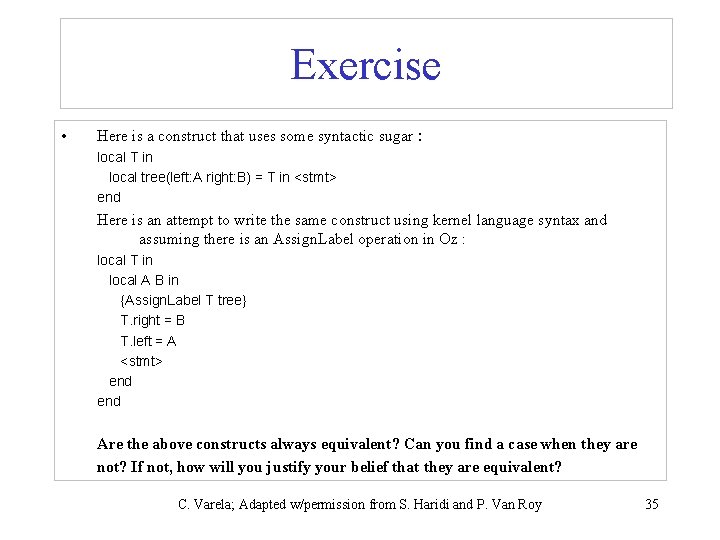

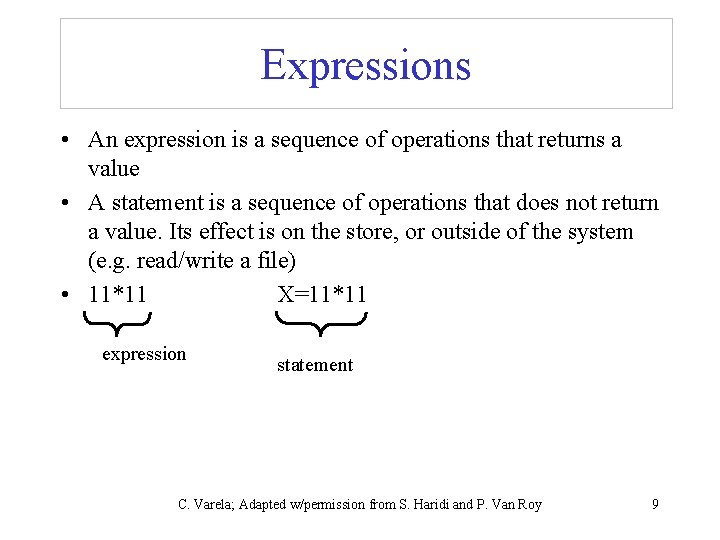

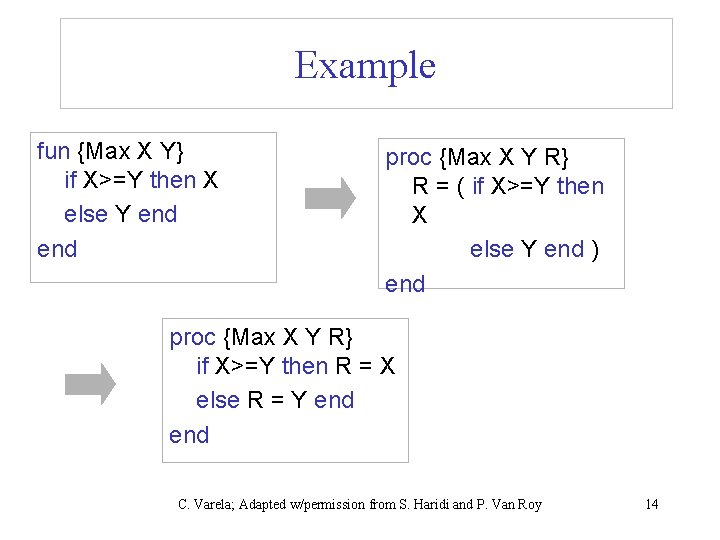

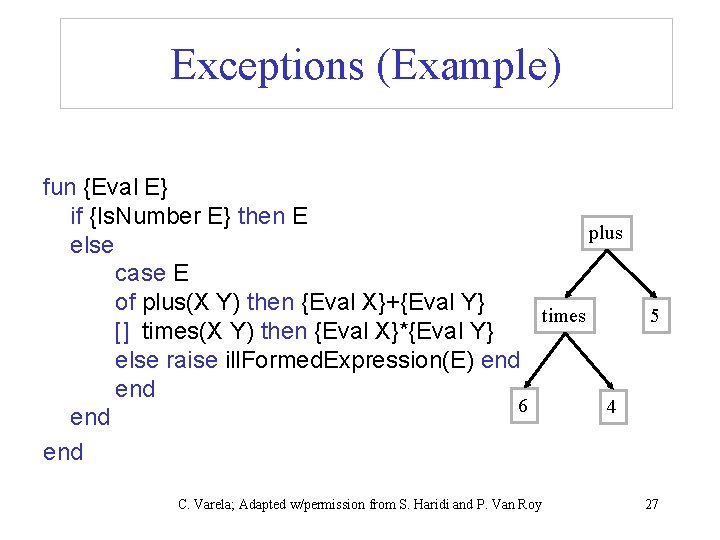

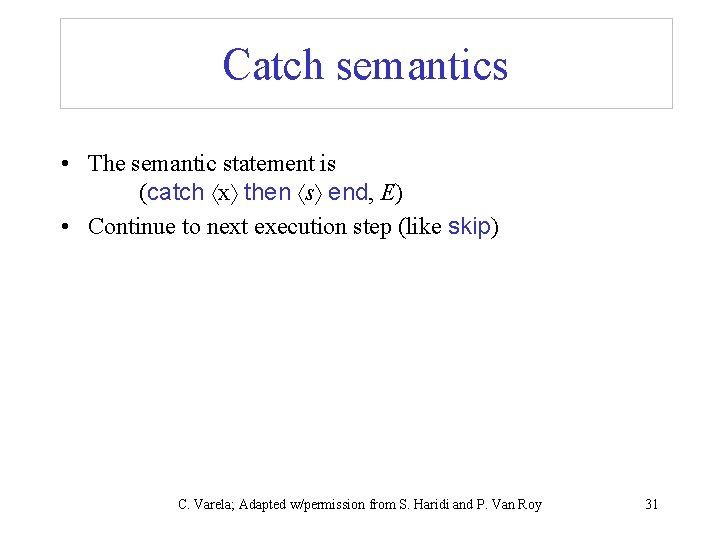

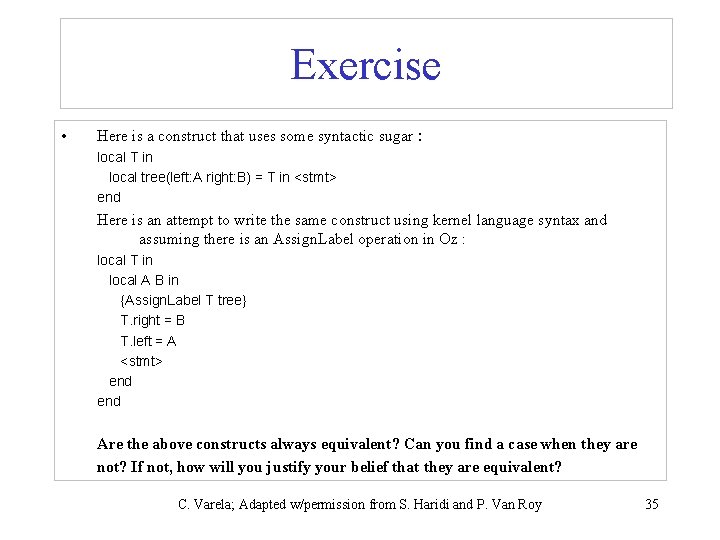

A complete example fun {Map Xs F} case Xs of nil then nil [] X|Xr then {F X}|{Map Xr F} end proc {Map Xs F Ys} case Xs of nil then Ys = nil [] X|Xr then Y Yr in Ys = Y|Yr {F X Y} {Map Xr F Yr} end C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 17

Back to semantics • Efficient loops in the declarative model – recursion used for looping – is efficient because of last call optimization – memory management and garbage collection • Exceptions • Functional programming C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 18

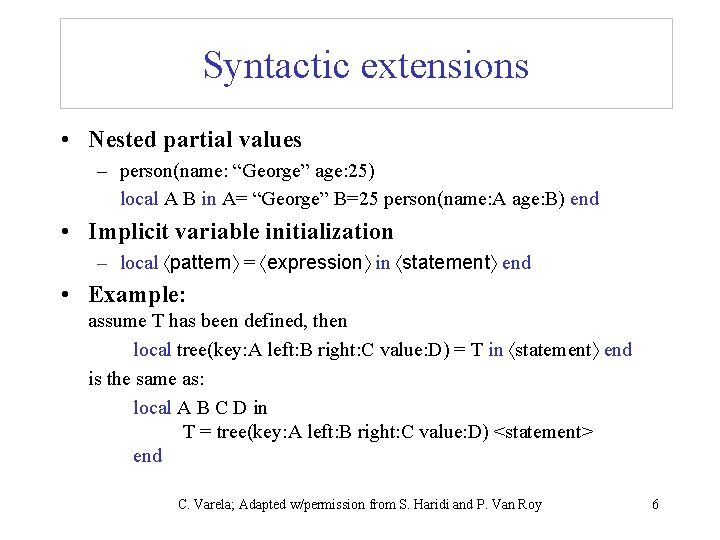

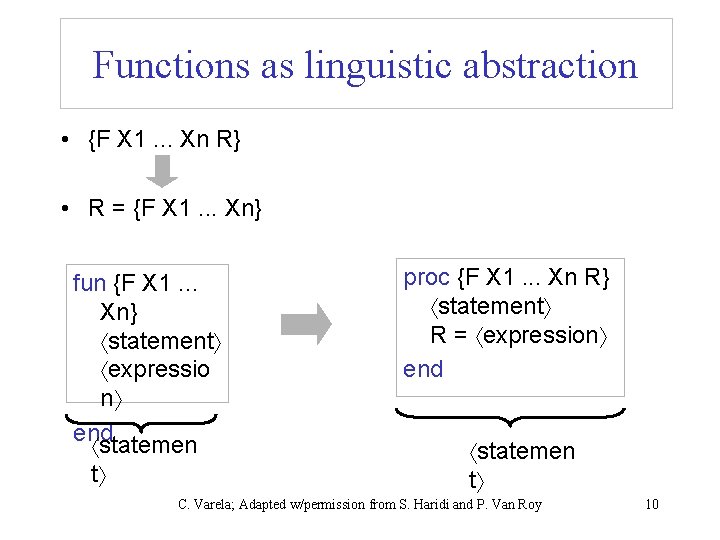

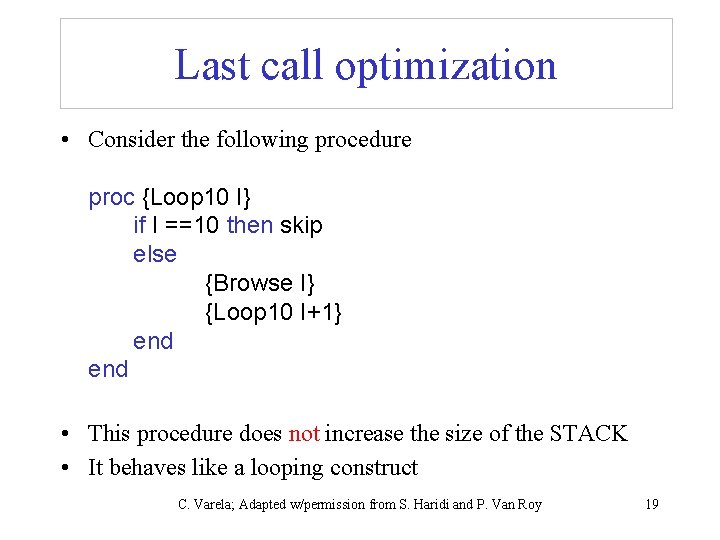

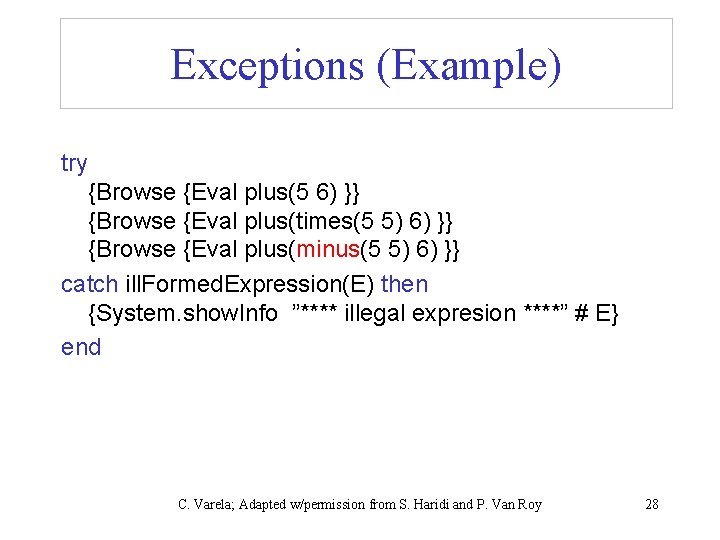

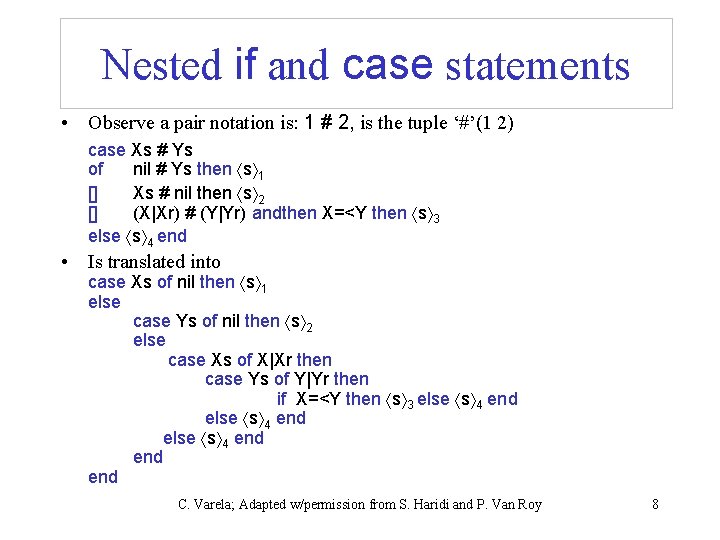

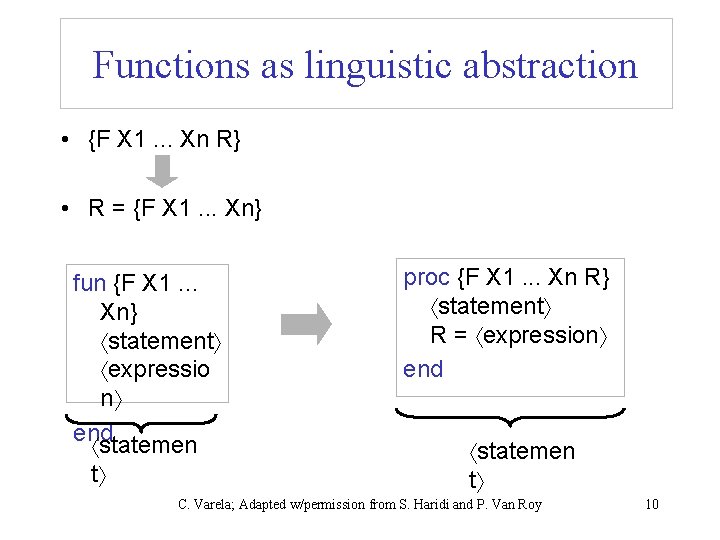

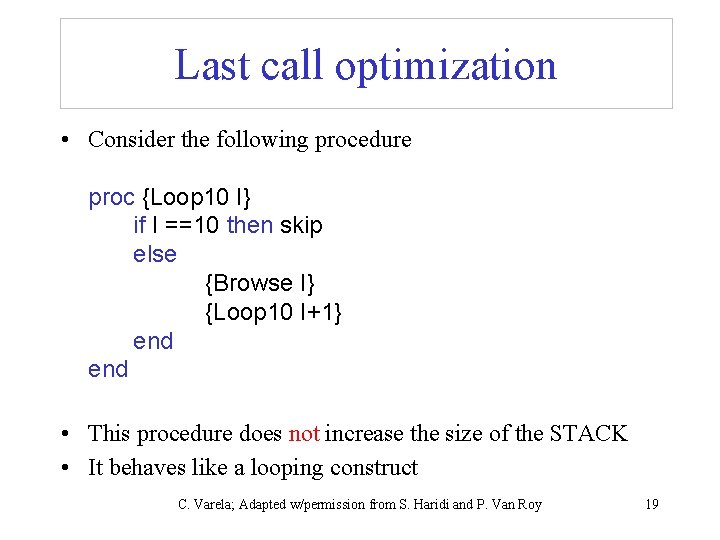

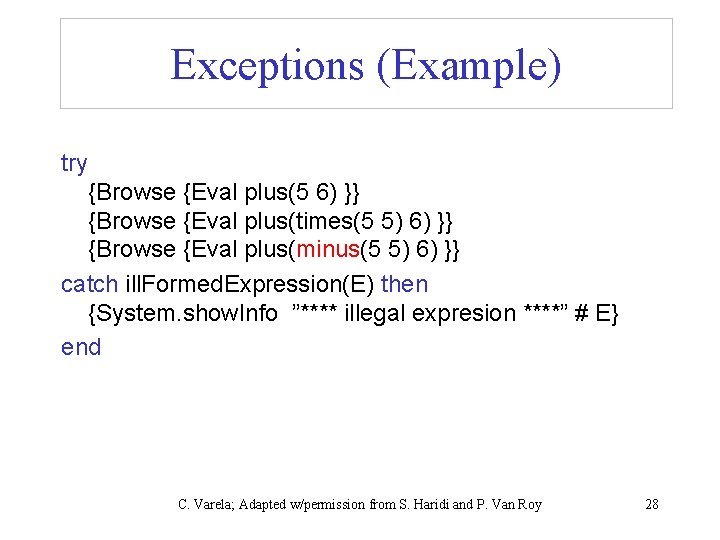

Last call optimization • Consider the following procedure proc {Loop 10 I} if I ==10 then skip else {Browse I} {Loop 10 I+1} end • This procedure does not increase the size of the STACK • It behaves like a looping construct C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 19

![Last call optimization ST Loop 10 0 E 0 proc Loop 10 Last call optimization ST: [ ({Loop 10 0}, E 0) ] proc {Loop 10](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/b6dd12b283cc6e9c038c585b6557ba9c/image-20.jpg)

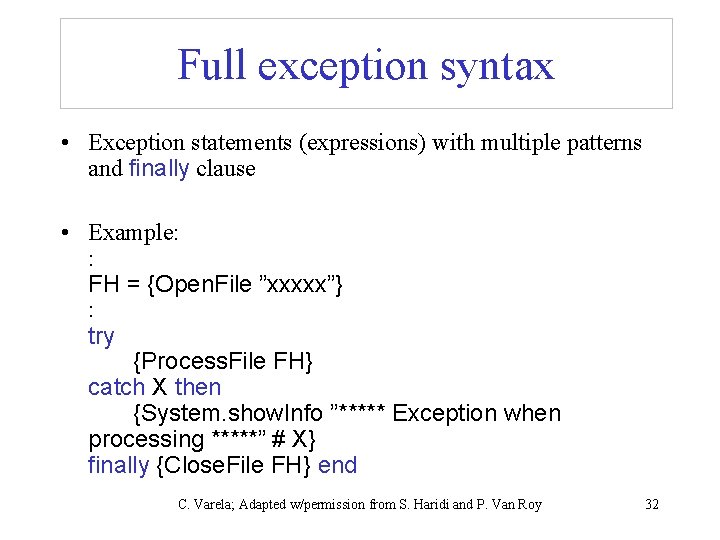

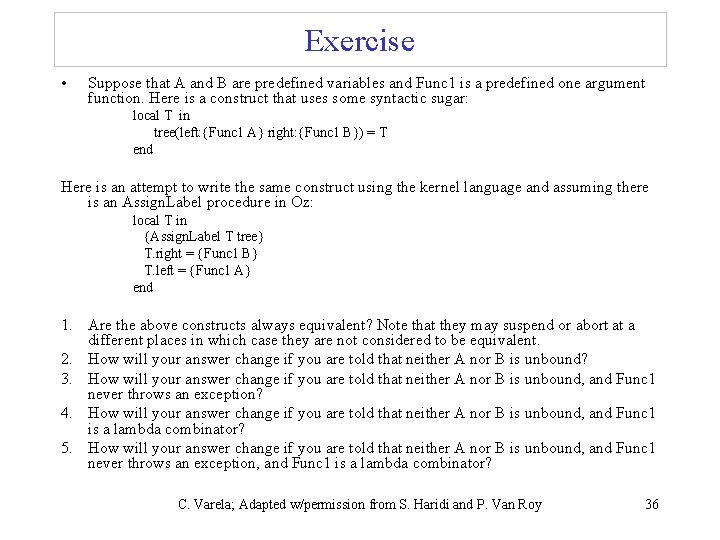

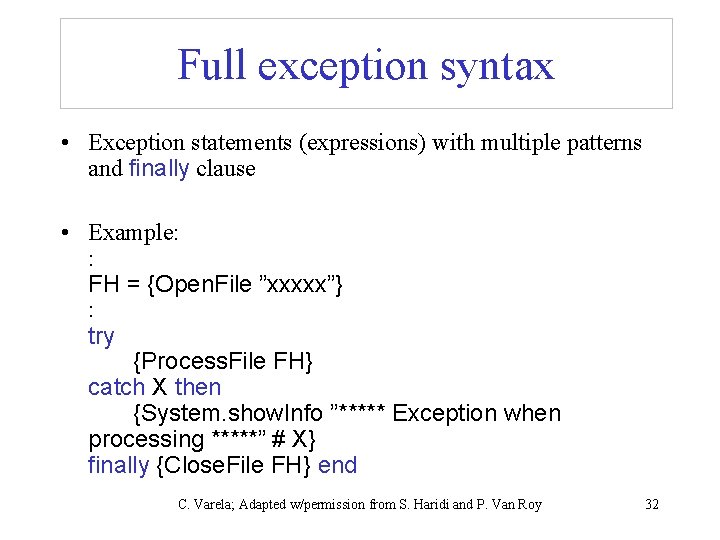

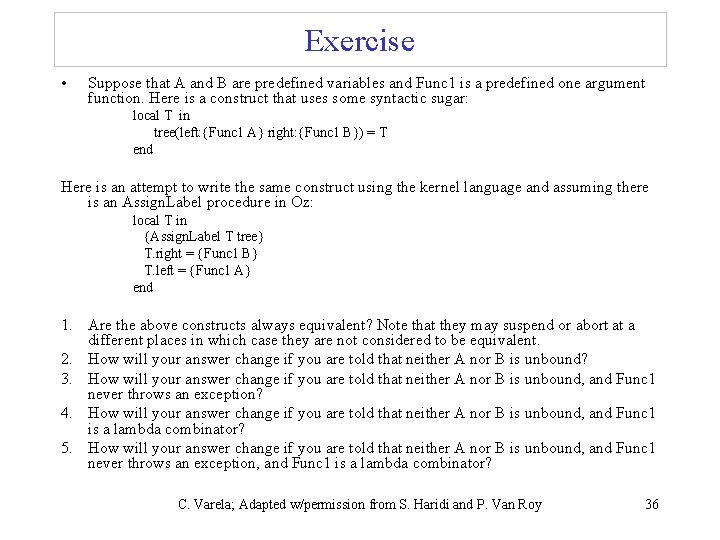

Last call optimization ST: [ ({Loop 10 0}, E 0) ] proc {Loop 10 I} if I ==10 then skip else {Browse I} {Loop 10 I+1} end ST: [({Browse I}, {I i 0, . . . }) ({Loop 10 I+1}, {I i 0, . . . }) ] : {i 0=0, . . . } ST: [({Browse I}, {I i 1, . . . }) ({Loop 10 I+1}, {I i 1, . . . }) ] : {i 0=0, i 1=1, . . . } C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 20

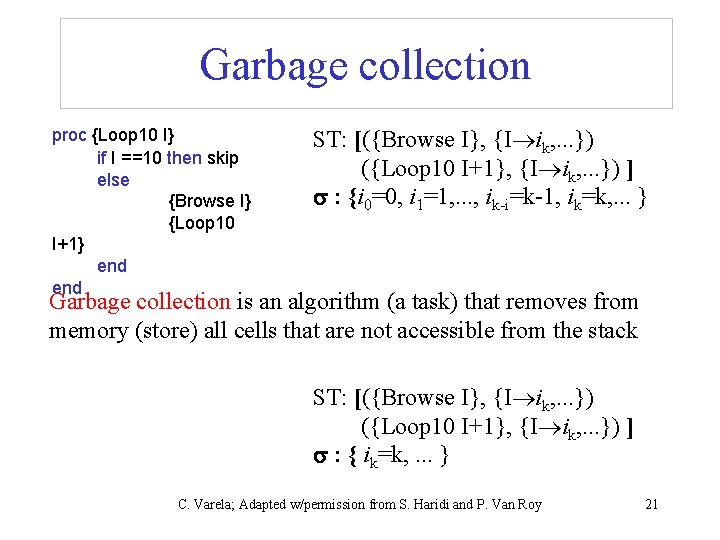

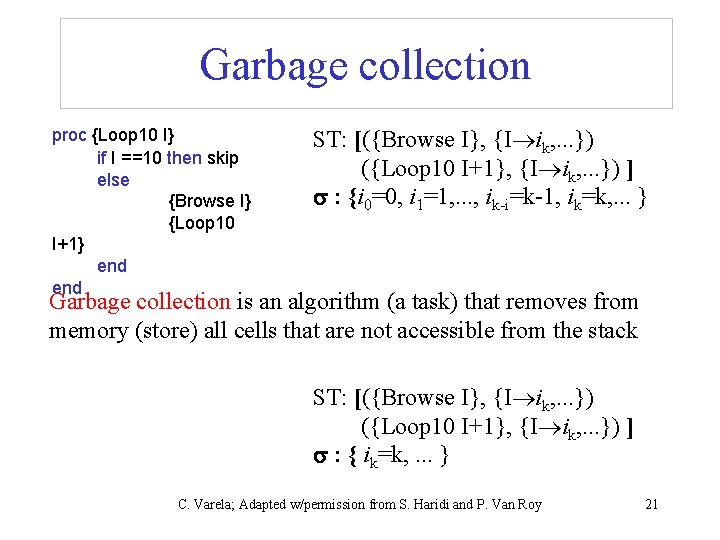

Garbage collection proc {Loop 10 I} if I ==10 then skip else {Browse I} {Loop 10 I+1} end ST: [({Browse I}, {I ik, . . . }) ({Loop 10 I+1}, {I ik, . . . }) ] : {i 0=0, i 1=1, . . . , ik-i=k-1, ik=k, . . . } Garbage collection is an algorithm (a task) that removes from memory (store) all cells that are not accessible from the stack ST: [({Browse I}, {I ik, . . . }) ({Loop 10 I+1}, {I ik, . . . }) ] : { ik=k, . . . } C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 21

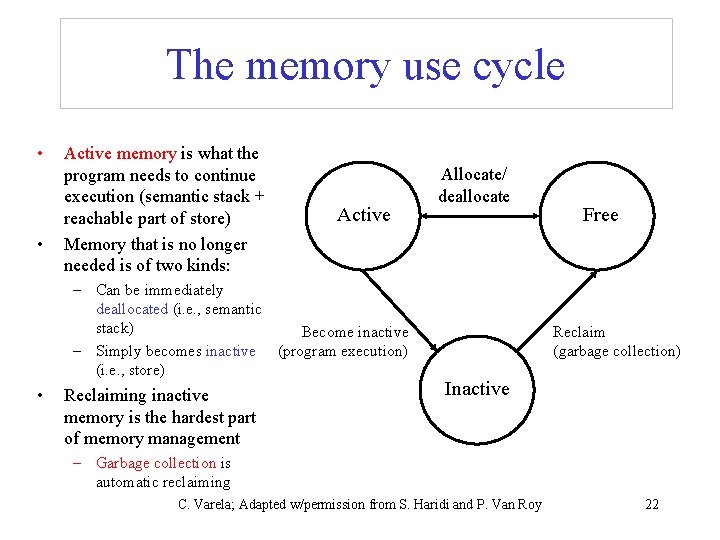

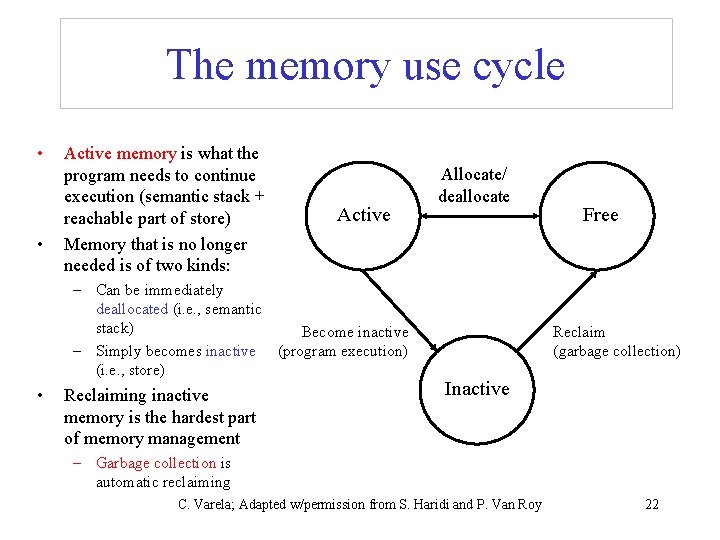

The memory use cycle • • Active memory is what the program needs to continue execution (semantic stack + reachable part of store) Memory that is no longer needed is of two kinds: Active – Can be immediately deallocated (i. e. , semantic stack) Become inactive – Simply becomes inactive (program execution) (i. e. , store) • Reclaiming inactive memory is the hardest part of memory management Allocate/ deallocate Free Reclaim (garbage collection) Inactive – Garbage collection is automatic reclaiming C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 22

The Mozart Garbage Collector • Copying dual-space algorithm • Advantage : Execution time is proportional to the active memory size • Disadvantage : Half of the total memory is unusable at any given time C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 23

Exceptions • How to handle exceptional situations in the program? • Examples: – divide by 0 – opening a nonexistent file • Some errors are programming errors • Some errors are imposed by the external environment • Exception handling statements allow programs to handle and recover from errors C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 24

Exceptions • Exception handling statements allow programs to handle and recover from errors • The error confinement principle: – Define your program as a structured layers of components – Errors are visible only internally and a recovery procedure corrects the errors: either errors are not visible at the component boundary or are reported (nicely) to a higher level • In one operation, exit from arbitrary depth of nested contexts – Essential for program structuring; else programs get complicated (use boolean variables everywhere, etc. ) C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 25

Basic concepts • A program that encounters an error (exception) should transfer execution to another part, the exception handler and give it a (partial) value that describes the error • try s 1 catch x then s 2 end • raise x end • Introduce an exception marker on the semantic stack • The execution is equivalent to s 1 if it executes without raising an error • Otherwise, s 1 is aborted and the stack is popped up to the marker, the error value is transferred through x , and s 2 is executed C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 26

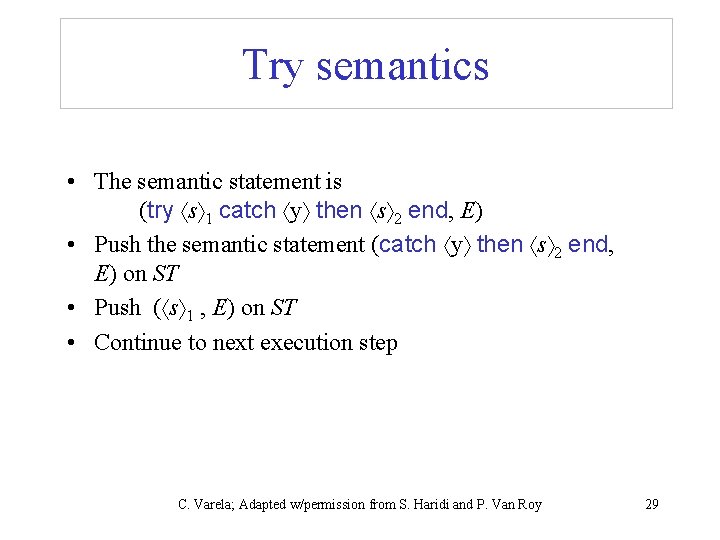

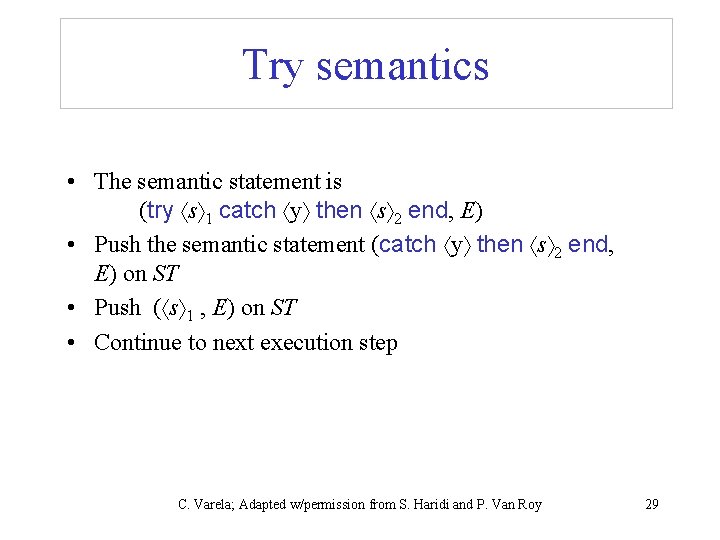

Exceptions (Example) fun {Eval E} if {Is. Number E} then E plus else case E of plus(X Y) then {Eval X}+{Eval Y} times [] times(X Y) then {Eval X}*{Eval Y} else raise ill. Formed. Expression(E) end 6 4 end C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 5 27

Exceptions (Example) try {Browse {Eval plus(5 6) }} {Browse {Eval plus(times(5 5) 6) }} {Browse {Eval plus(minus(5 5) 6) }} catch ill. Formed. Expression(E) then {System. show. Info ”**** illegal expresion ****” # E} end C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 28

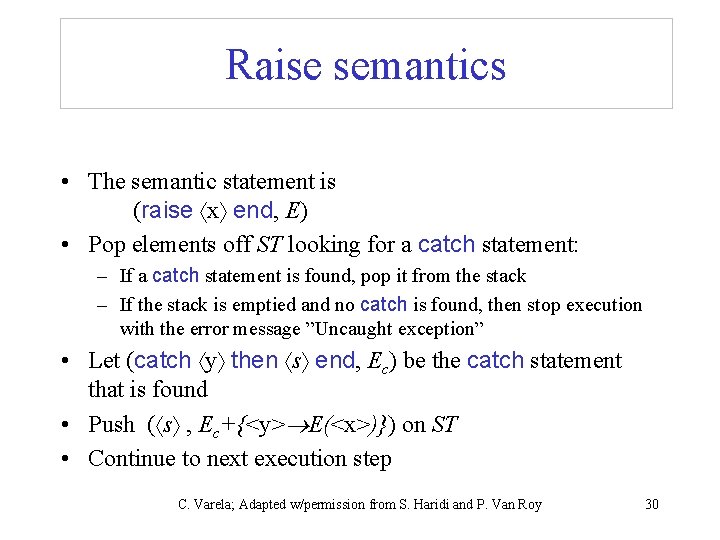

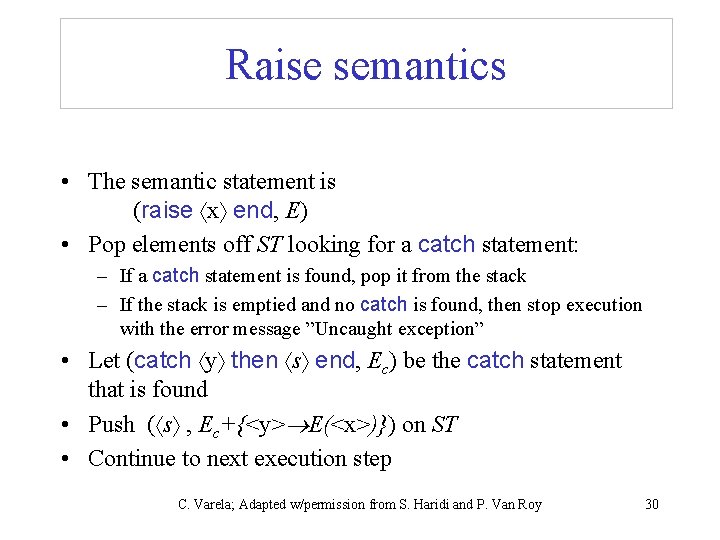

Try semantics • The semantic statement is (try s 1 catch y then s 2 end, E) • Push the semantic statement (catch y then s 2 end, E) on ST • Push ( s 1 , E) on ST • Continue to next execution step C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 29

Raise semantics • The semantic statement is (raise x end, E) • Pop elements off ST looking for a catch statement: – If a catch statement is found, pop it from the stack – If the stack is emptied and no catch is found, then stop execution with the error message ”Uncaught exception” • Let (catch y then s end, Ec) be the catch statement that is found • Push ( s , Ec+{<y> E(<x>)}) on ST • Continue to next execution step C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 30

Catch semantics • The semantic statement is (catch x then s end, E) • Continue to next execution step (like skip) C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 31

Full exception syntax • Exception statements (expressions) with multiple patterns and finally clause • Example: : FH = {Open. File ”xxxxx”} : try {Process. File FH} catch X then {System. show. Info ”***** Exception when processing *****” # X} finally {Close. File FH} end C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 32

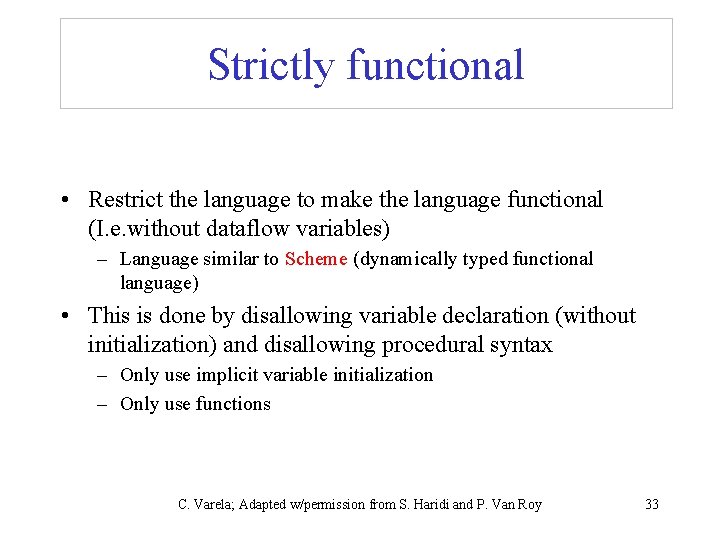

Strictly functional • Restrict the language to make the language functional (I. e. without dataflow variables) – Language similar to Scheme (dynamically typed functional language) • This is done by disallowing variable declaration (without initialization) and disallowing procedural syntax – Only use implicit variable initialization – Only use functions C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 33

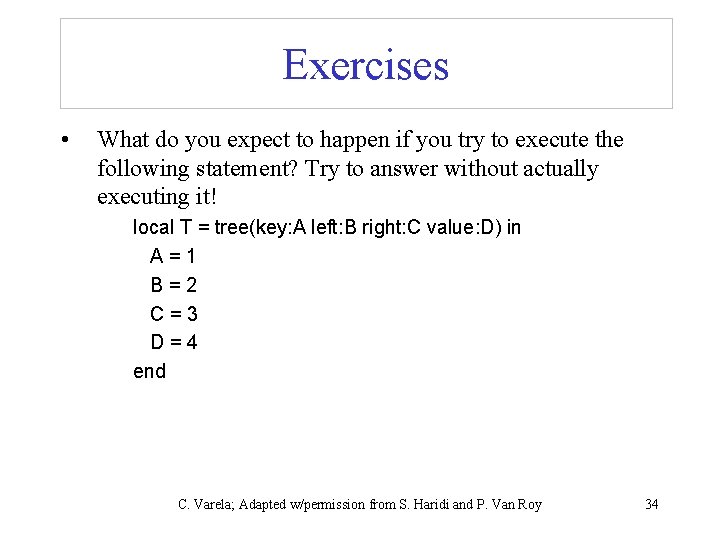

Exercises • What do you expect to happen if you try to execute the following statement? Try to answer without actually executing it! local T = tree(key: A left: B right: C value: D) in A=1 B=2 C=3 D=4 end C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 34

Exercise • Here is a construct that uses some syntactic sugar : local T in local tree(left: A right: B) = T in <stmt> end Here is an attempt to write the same construct using kernel language syntax and assuming there is an Assign. Label operation in Oz : local T in local A B in {Assign. Label T tree} T. right = B T. left = A <stmt> end Are the above constructs always equivalent? Can you find a case when they are not? If not, how will you justify your belief that they are equivalent? C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 35

Exercise • Suppose that A and B are predefined variables and Func 1 is a predefined one argument function. Here is a construct that uses some syntactic sugar: local T in tree(left: {Func 1 A} right: {Func 1 B}) = T end Here is an attempt to write the same construct using the kernel language and assuming there is an Assign. Label procedure in Oz: local T in {Assign. Label T tree} T. right = {Func 1 B} T. left = {Func 1 A} end 1. Are the above constructs always equivalent? Note that they may suspend or abort at a different places in which case they are not considered to be equivalent. 2. How will your answer change if you are told that neither A nor B is unbound? 3. How will your answer change if you are told that neither A nor B is unbound, and Func 1 never throws an exception? 4. How will your answer change if you are told that neither A nor B is unbound, and Func 1 is a lambda combinator? 5. How will your answer change if you are told that neither A nor B is unbound, and Func 1 never throws an exception, and Func 1 is a lambda combinator? C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 36

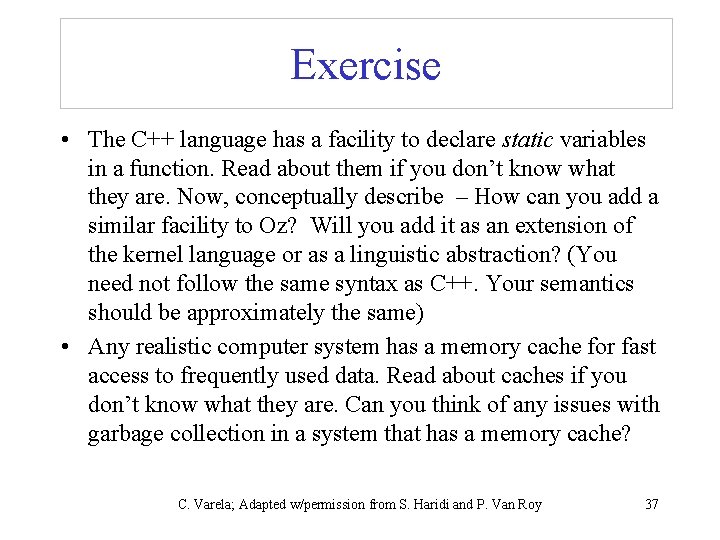

Exercise • The C++ language has a facility to declare static variables in a function. Read about them if you don’t know what they are. Now, conceptually describe – How can you add a similar facility to Oz? Will you add it as an extension of the kernel language or as a linguistic abstraction? (You need not follow the same syntax as C++. Your semantics should be approximately the same) • Any realistic computer system has a memory cache for fast access to frequently used data. Read about caches if you don’t know what they are. Can you think of any issues with garbage collection in a system that has a memory cache? C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 37

Exercise • Do problems 3, 9 and 12 in Section 2. 9 • Read Sections 3. 7 and 6. 4 C. Varela; Adapted w/permission from S. Haridi and P. Van Roy 38