Decision Making On the Reality of Cognitive Illusions

- Slides: 28

Decision Making On the Reality of Cognitive Illusions (Kahneman & Tversky, 1996) On Narrow Norms and Vague Heuristics: A Reply to Kahneman and Tversky (Gigerenzer, 1996) A reexamination of the evidence for the somatic marker hypothesis: What participants really know in the Iowa gambling task (Maia & Mc. Clelland, 2004) Expectations and outcomes: Decision-making in the primate brain (Mc. Coy & Platt, 2005) 1

Kahneman & Tversky (1996) VS. Gigerenzer (1996) 2

On the Reality of Cognitive Illusions (Kahneman & Tversky, 1996) • Judgmental heuristics – Useful BUT sometimes lead to errors or biases • Main goal of studying heuristics and biases : understand the cognitive processes that produce valid/invalid judgments. • Criticism : portrays human mind in an overly negative light 3

Base-Rate Neglect • Base rate that is known to subject, at least approximately, is ignored or significantly underweighted – Due to use of representativeness heuristics. – Representativeness: “Fit” or similiarity He must be a business man 4

Base-Rate Neglect • Diagnosing whether a patient has rare (25%) or common (75%) disease (Bluck & Bower, 1988) – Judgments of relative frequency of the two diseases were determined entirely by diagnosticity of symptom, with no regard for base-rate frequencies of the diseases – K & T : Our mind is not a frequency monitoring device! – G : Misinterpretation of the original study (“baserate info is not ignored, only underused”) 5

Base-Rate Neglect • Outcome Ranking paradigm • Give case data about person, ask subject to rank outcomes (e. g. , occupations) by different criteria (e. g. , representativeness, probability, base rate) – Rankings by representativeness and by probability were nearly identical – K & T : The role of representativeness in prediction is critical (underusing base-rate). – G : Use of random sampling makes this disappear. • → K & T: No! 6

Conjunction Errors • ∩ If A includes B then the probability of B cannot exceed the probability of A; A B implies P(A) ≥ P(B) – Conjunction Rule: P(A & B) ≤ P(A) – Because representativeness and availability are not constrained by this rule, violations are expected in situations where a conjunction is more representative or available than one of its components 7

Conjunction Errors • “Linda” Experiment • Imagine a young woman, named Linda, who resembles a feminist, but not a bank teller • Which is more probable? – (a) Linda is a bank teller – (b) Linda is a bank teller who is active in the feminist movement – K & T : Although (a) is more likely than (b), judgment based on representativeness results in conjunction error. – G : Content-blind! 8

Conjunction Errors • “Linda” Experiment – K & T : Although (a) is more likely than (b), judgment based on representativeness results in conjunction error. – G : Content-blind! – Sound reasoning starts w/ investigating content of problem • • What is 'probable' ? ? The meaning of AND in this context – According to K&T, content of problem is irrelevant and only terms probable and is important. 9

Conjunction Errors How detection of inclusion and appreciation of its significance affect conjunction errors • Estimating frequency of each category facilitates detection of inclusion – e. g. , estimate # of bank tellers & # of feminist bank tellers • → According to K & T : There are conditions under which the correct answer is made transparent, but the phenomenon is still very interesting! • → According to G : Why is this? ? What is the underlying process that makes the correct answer transparent? (critique about vague heuristics) 10

Overconfidence Mean confidence exceeds overall accuracy • Which city has the larger population? • • (a) Tokyo (b) New York How confident are you? (e. g. , 0% – 100%) Illusion of validity • Average confidence for single items VS. estimates of the percentage of items they answered correctly – Inside view (single-case approach) VS Outside view (frequentistic approach) • Does not contradict K&T's theoretical position: Diff perspectives yield diff estimates 11

Critiques of heuristics & biases Ex) Representativeness remain vague, undefined, and unspecified with respect to conditions that elicit them and to the cognitive processes that underlie them. <Narrow Norms> • Problems for “Linda” example: (1) prob. theory is imposed as a norm for single event (e. g. , whether Linda is a bank teller) (2) norm is applied in content-blind way <Vague Heuristics> (1) One-word-labels traded as explanation by redescription (2) 12

A reexamination of the evidence for the somatic marker hypothesis (Maia & Mc. Clelland, 2004) Somatic Marker Hypothesis (Bechara, Damasio, & Damasio, 2000) • Affective somatic states associated with prior decision outcomes are used to guide future decisions • Optimal decision making is not simply result of rational, cognitive calculation of gains & losses but based on good/bad emotional reactions to prior outcomes of choices (Hinson, Jameson, Whitney, 2002) 13

A reexamination of the evidence for the somatic marker hypothesis (Maia & Mc. Clelland, 2004) Iowa Gambling Task (IGT) • Task: select a card from 4 decks on each trial with a goal to have the best possible net outcome • Two $100 decks and two $50 decks • – $100 decks: longterm net loss (avg of $25/trial) – $50 decks: longterm net gain (avg of $25/trial) Provide evidence for somatic marker hypothesis – e. g. , skin-conductance response 14

A reexamination of the evidence for the somatic marker hypothesis (Maia & Mc. Clelland, 2004) Problems w/ previous studies using IGT • Prior studies (Bechera et al, 1997) asked subjects about explicit knowledge w/ questions such as “tell me all you know about what is going on in this game” – • Open-ended questions often fail to identify all of conscious knoweldge. (MAYBE THEY KNOW BUT THEIR KNOWLEDGE WASN'T ASSESSED PROPERLY) “Good Deck” VS “Bad Deck” – Good and bad decks should be determined on each trial based on mean net outcomes a subject has had w/ each deck up until that trial 15

A reexamination of the evidence for the somatic marker hypothesis (Maia & Mc. Clelland, 2004) • • Defining levels of conscious knowledge – Level 0. No conscious knowledge for preference – Level 1. Conscious knowledge specifying pref. for one of two best decks but no conscious knowledge about outcomes of decks – Level 2. Conscious knowledge specifying a pref. & about outcomes Question: Do individuals behave advantageously even when they are at Level 0 or 1? 16

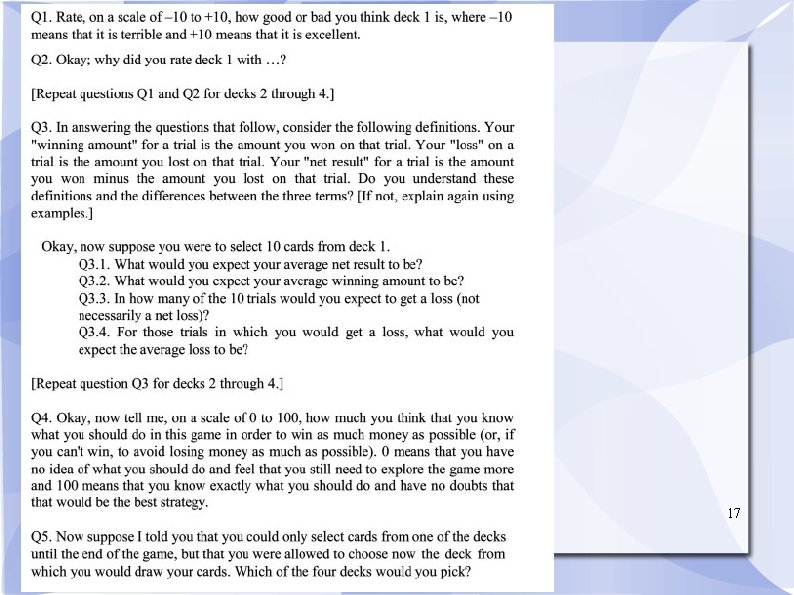

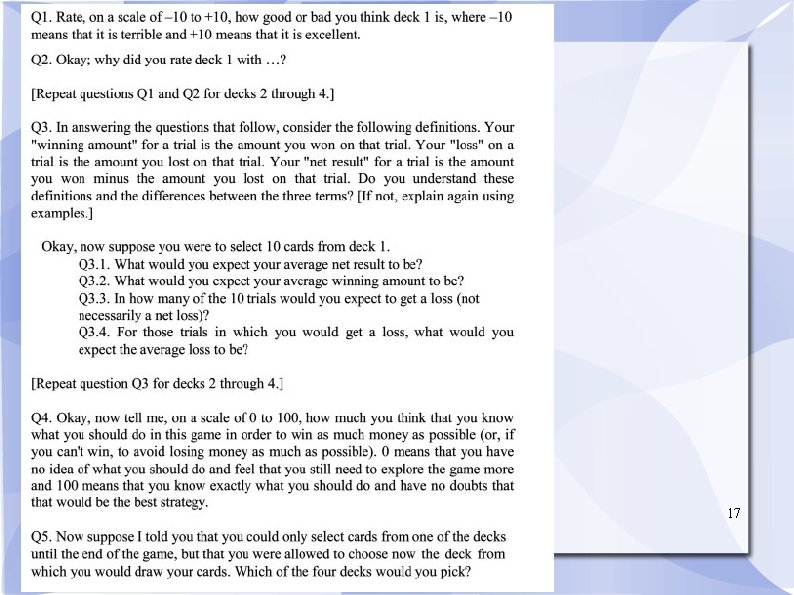

17

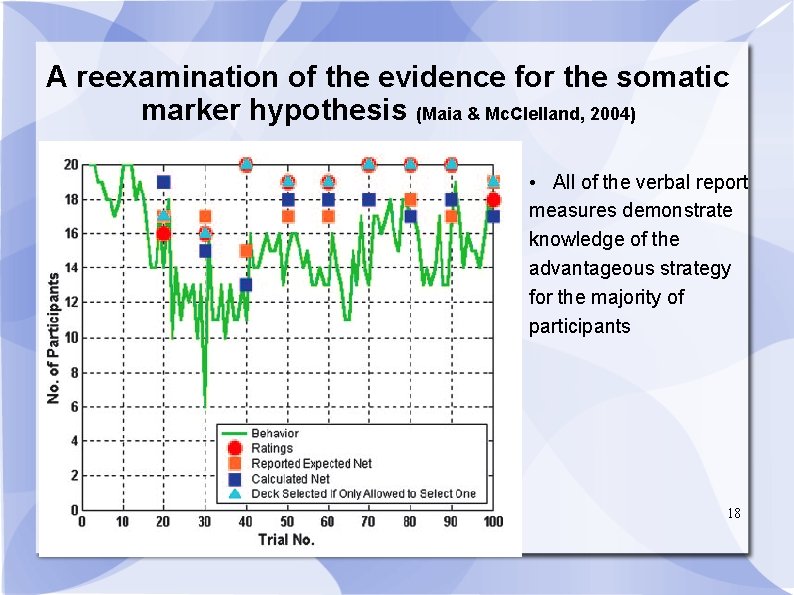

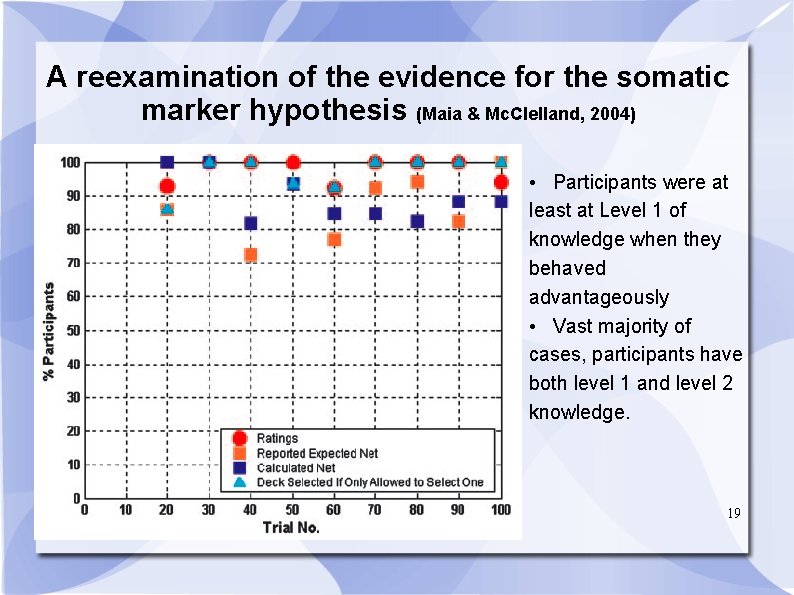

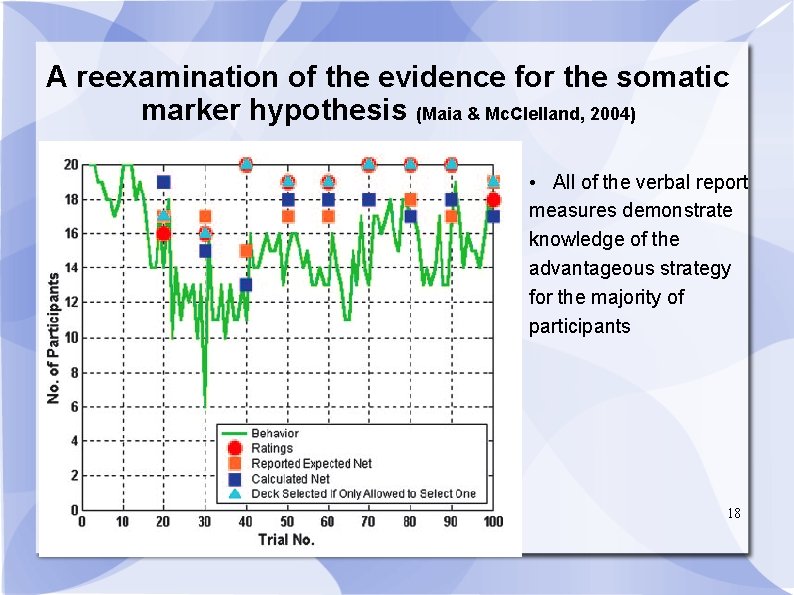

A reexamination of the evidence for the somatic marker hypothesis (Maia & Mc. Clelland, 2004) • All of the verbal report measures demonstrate knowledge of the advantageous strategy for the majority of participants 18

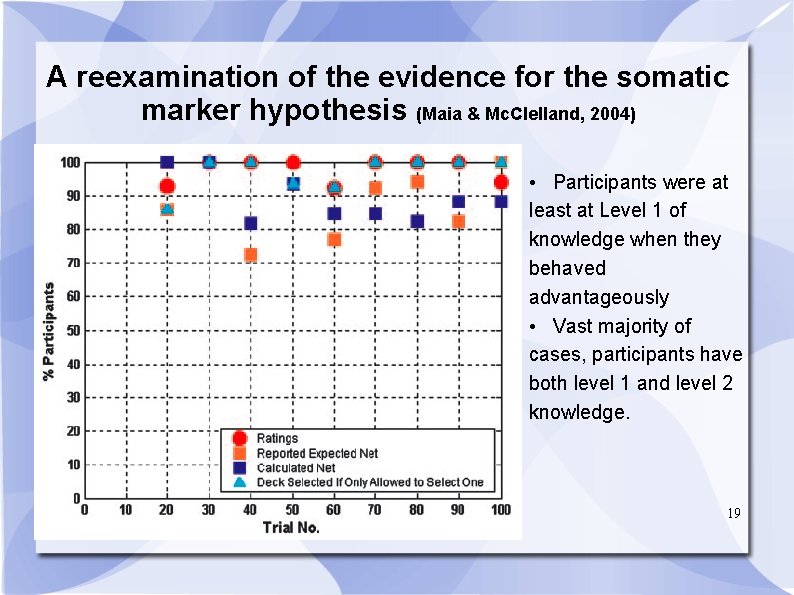

A reexamination of the evidence for the somatic marker hypothesis (Maia & Mc. Clelland, 2004) • Participants were at least at Level 1 of knowledge when they behaved advantageously • Vast majority of cases, participants have both level 1 and level 2 knowledge. 19

A reexamination of the evidence for the somatic marker hypothesis (Maia & Mc. Clelland, 2004) • Seems that people know what they're doing in IGT. – Knowledge may be sufficient to explain behavior in IGT • Possibility that SCRs reflect emotional responses elicited by knowledge that is consciously accessible 20

Expectations and outcomes: decision-making in the primate brain (Mc. Coy & Plan, 2005) Expected Value Theory → choose option w/ highest expected value (probability x expected reward) • Humans/animals are sensitive to expected value of available options – → suggests that nervous systems somehow represent info about estimated costs and benefits of potential behav. to link sensation to action • Stages of Oculomotor decision-making Sensation → reward expectation → action → outcome evaluation 21

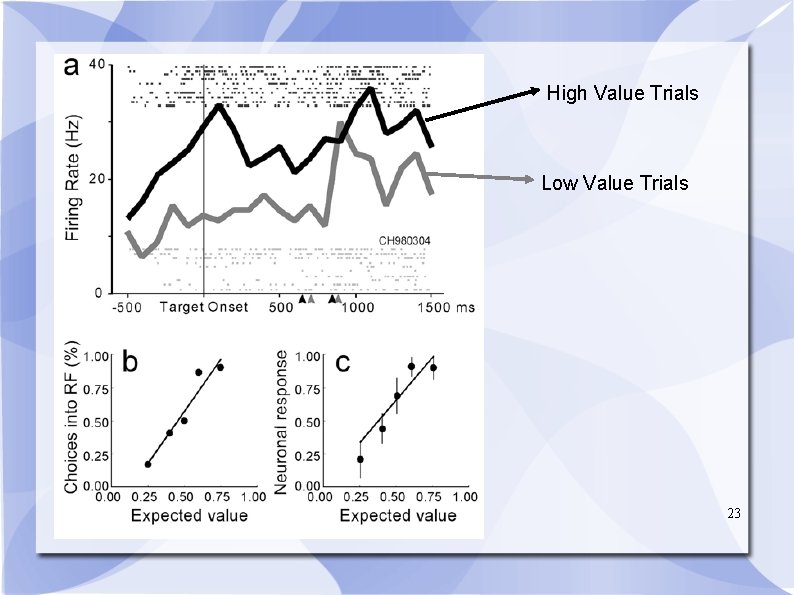

Expectations and outcomes: decision-making in the primate brain (Mc. Coy & Plan, 2005) Expected value and primate parietal cortex • The role of Lateral Intraparietal area (LIT) – When monkeys were permitted to freely choose between two eye movements (looking up VS down) • modulated by both the size of reward and the probability of reinforcement. Sensation → reward expectation → action → outcome evaluation 22

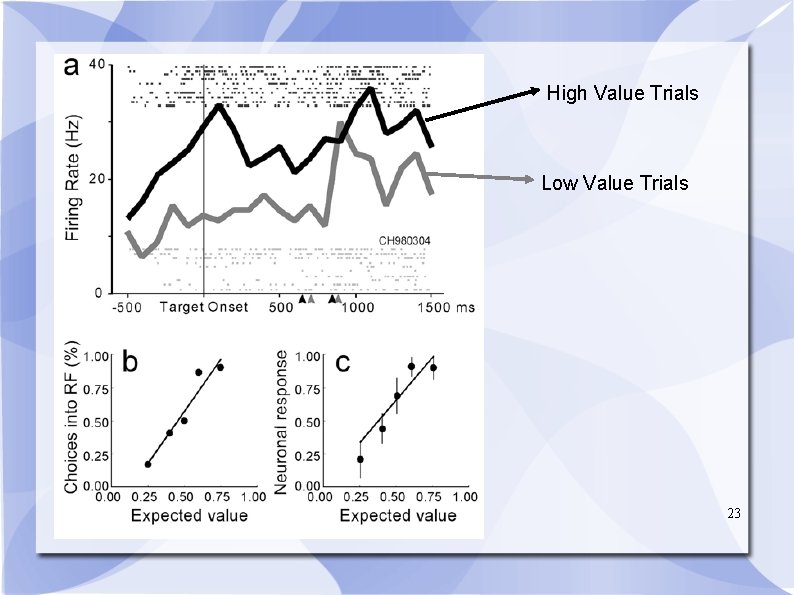

High Value Trials Low Value Trials 23

Expectations and outcomes: decision-making in the primate brain (Mc. Coy & Plan, 2005) Expected value and primate cortex • Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, supplementary eye fields, substantia nigra pars reticulata, superior colluculus – Expected value systematically biases neuronal activity throughout the cortical and subcortical oculomotor afferents to the superior colliculus 24

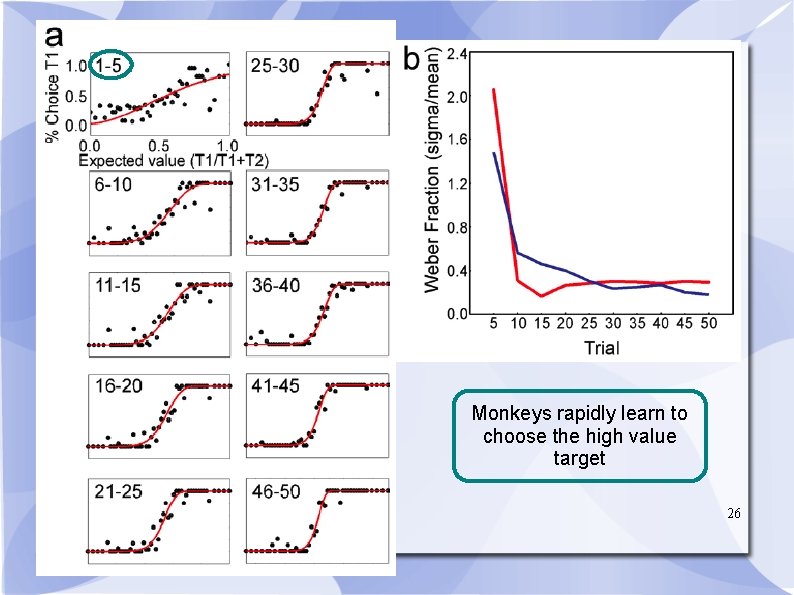

Expectations and outcomes: decision-making in the primate brain (Mc. Coy & Plan, 2005) Learning from mistakes: dopamine and prediction error • Expected value of eye movements is rapidly updated in primate brain when reward contingencies change • Reward prediction error – – comparison of expected and actual reward dopamine neurons in substantia nigra & ventral tegmental area: elevated by delivery of unpredicted rewards, unchanged following predicted reward, depressed when expected rewards are withheld. → these neurons encode reward prediction error, thus determining the direction and rate of learning Sensation → reward expectation → action → outcome evaluation 25

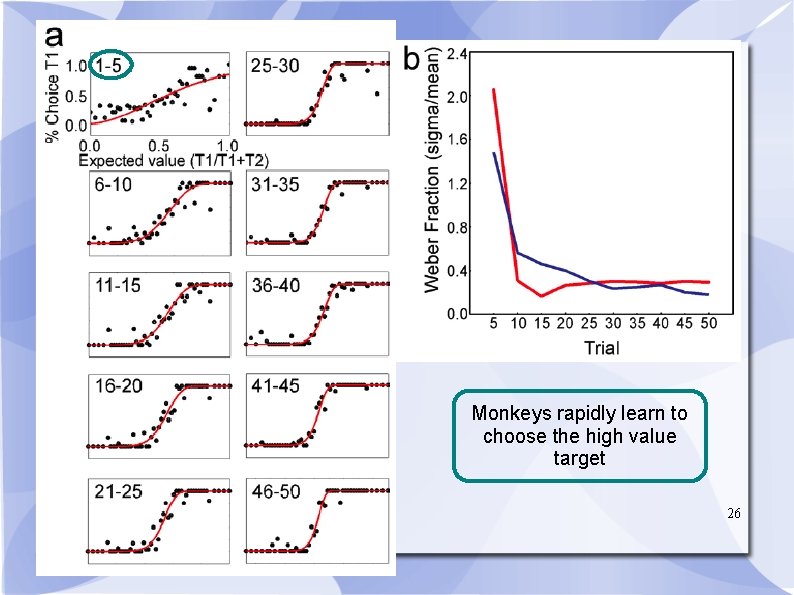

Monkeys rapidly learn to choose the high value target 26

Expectations and outcomes: decision-making in the primate brain (Mc. Coy & Plan, 2005) Updating expectations: posterior cingulate cortex • • Neurons in posterior cingulate cortex (CGp) – carries info about the predicted and experienced reward value of eye movement – reward modulation of neuronal activity in CGp: When reward differs from expectation, learning occurs (useful for instructing “when” & “how rapidly” learning should occur) Role of cingulate cortex in linking motivational outcomes to action Sensation → reward expectation → action → outcome evaluation 27

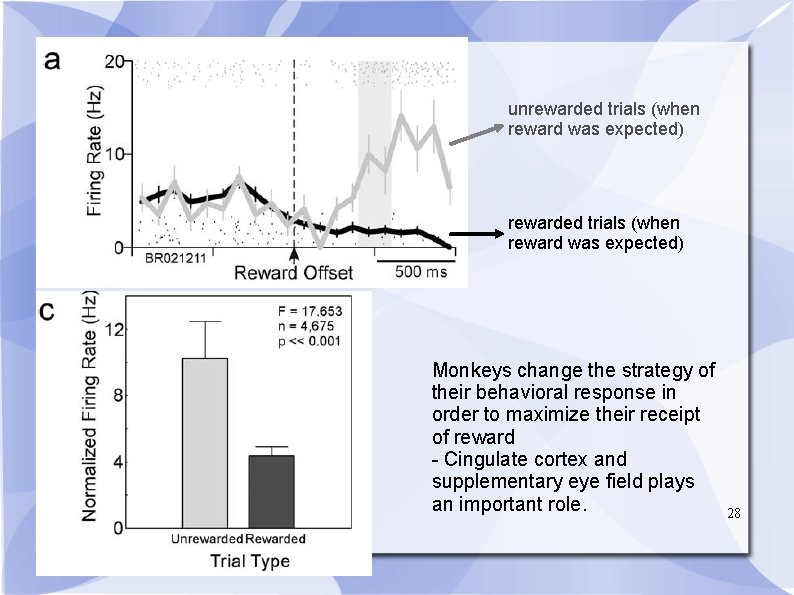

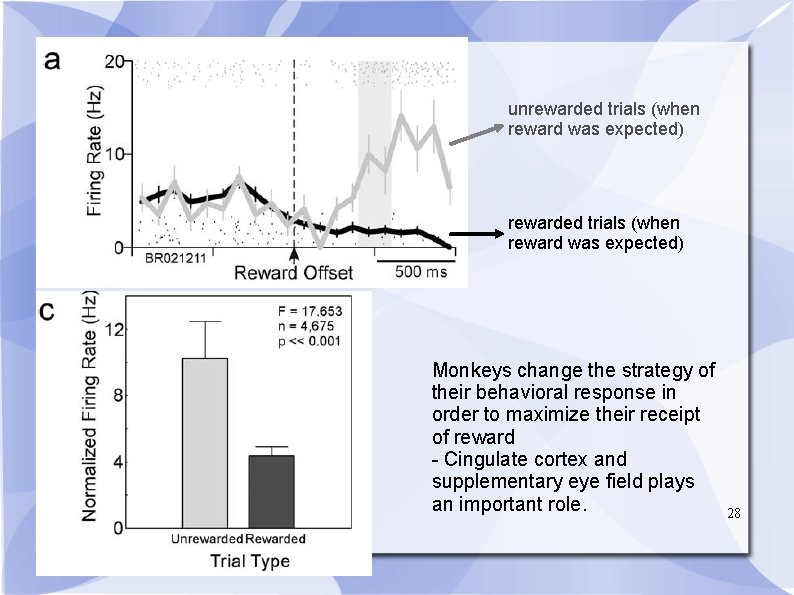

unrewarded trials (when reward was expected) Monkeys change the strategy of their behavioral response in order to maximize their receipt of reward - Cingulate cortex and supplementary eye field plays an important role. 28

Cognitive illusions in decision making

Cognitive illusions in decision making Financial decision

Financial decision Objectives of decision making

Objectives of decision making Cognitive and non cognitive religious language

Cognitive and non cognitive religious language The process of making an expectation a reality

The process of making an expectation a reality Mc escher optical illusions

Mc escher optical illusions Optical illusion elephant

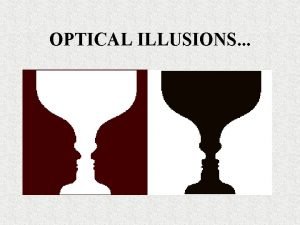

Optical illusion elephant Ambiguous images

Ambiguous images Optical illusions test

Optical illusions test What are positive illusions

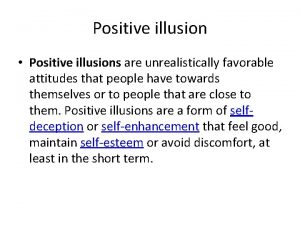

What are positive illusions Math illusions

Math illusions Hardest illusion

Hardest illusion Optical illusions

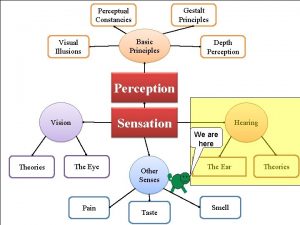

Optical illusions Module 9 gestalt psychology

Module 9 gestalt psychology Echalk optical illusions

Echalk optical illusions Optical illusions perspective

Optical illusions perspective Macbeth illusions

Macbeth illusions Elephant optical illusion

Elephant optical illusion By communicating the outside world

By communicating the outside world Optcl wikipedia

Optcl wikipedia Cat or moose illusion explained

Cat or moose illusion explained Gestalt psychology illusions

Gestalt psychology illusions Optical illusions how many faces

Optical illusions how many faces Optical illusions science fair project hypothesis

Optical illusions science fair project hypothesis Gestalt psychology strengths and weaknesses

Gestalt psychology strengths and weaknesses Decision tree and decision table

Decision tree and decision table Systematic decision making process

Systematic decision making process Making judgement in reasoning

Making judgement in reasoning The perceived relevance or importance of an ethical issue

The perceived relevance or importance of an ethical issue