DECISION DANS LINCERTAIN ET THEORIE DES JEUX Stefano

- Slides: 50

DECISION DANS L'INCERTAIN ET THEORIE DES JEUX Stefano MORETTI 1, David RIOS 2 and Alexis TSOUKIAS 1 1 LAMSADE (CNRS), Paris Dauphine 2 Statistics and Operations Research Department, Rey Juan Carlos University (URJC), Madrid Tous les mercredis de 13 h 45 à 17 h 00 du 20/01 au 24/02

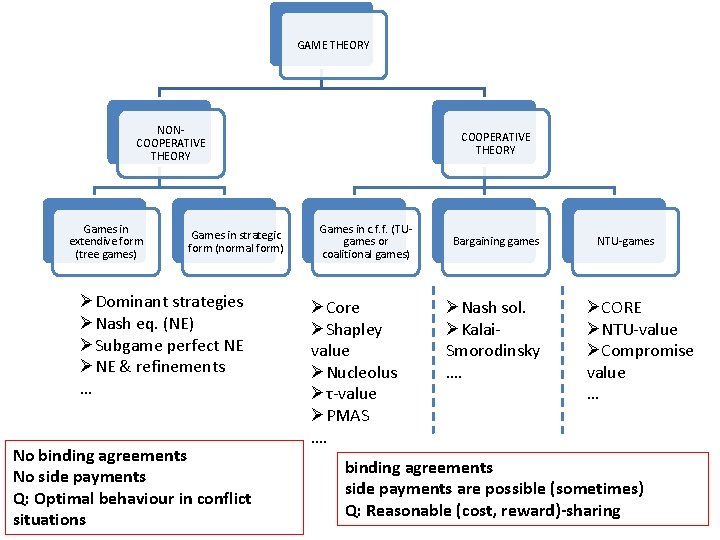

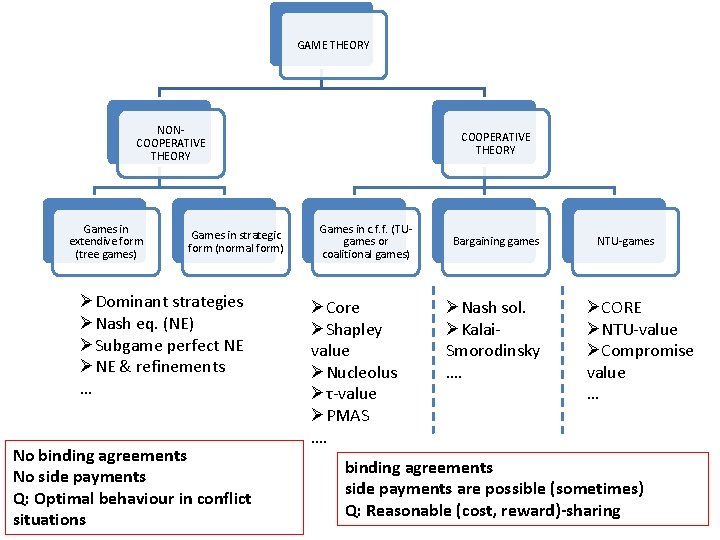

GAME THEORY NONCOOPERATIVE THEORY Games in extendive form (tree games) Games in strategic form (normal form) ØDominant strategies ØNash eq. (NE) ØSubgame perfect NE ØNE & refinements … No binding agreements No side payments Q: Optimal behaviour in conflict situations COOPERATIVE THEORY Games in c. f. f. (TUgames or coalitional games) ØCore ØShapley value ØNucleolus Øτ-value ØPMAS …. Bargaining games ØNash sol. ØKalai. Smorodinsky …. NTU-games ØCORE ØNTU-value ØCompromise value … binding agreements side payments are possible (sometimes) Q: Reasonable (cost, reward)-sharing

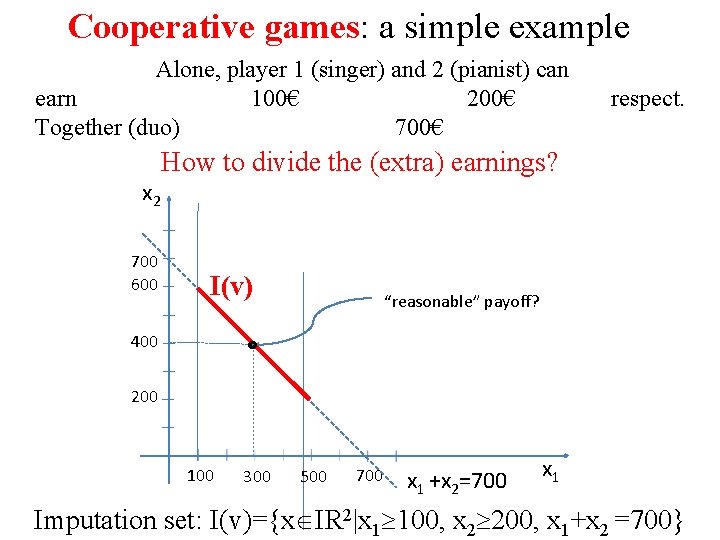

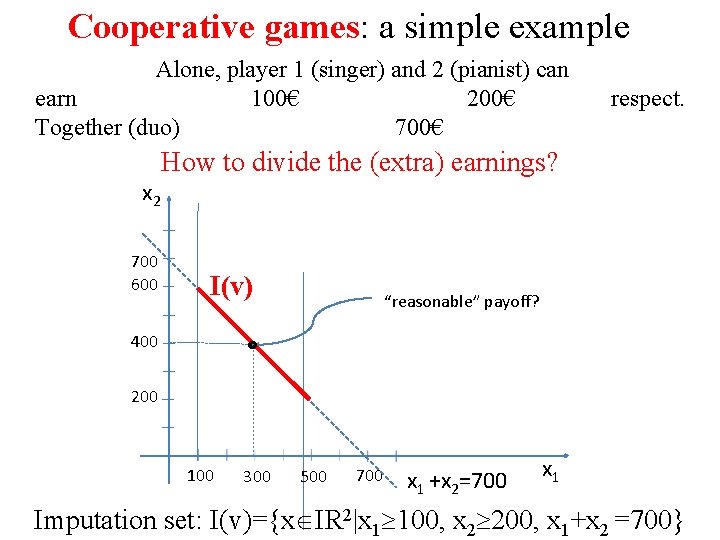

Cooperative games: a simple example Alone, player 1 (singer) and 2 (pianist) can earn 100€ 200€ Together (duo) 700€ respect. How to divide the (extra) earnings? x 2 700 600 I(v) “reasonable” payoff? 400 200 100 300 500 700 x 1 +x 2=700 x 1 Imputation set: I(v)={x IR 2|x 1 100, x 2 200, x 1+x 2 =700}

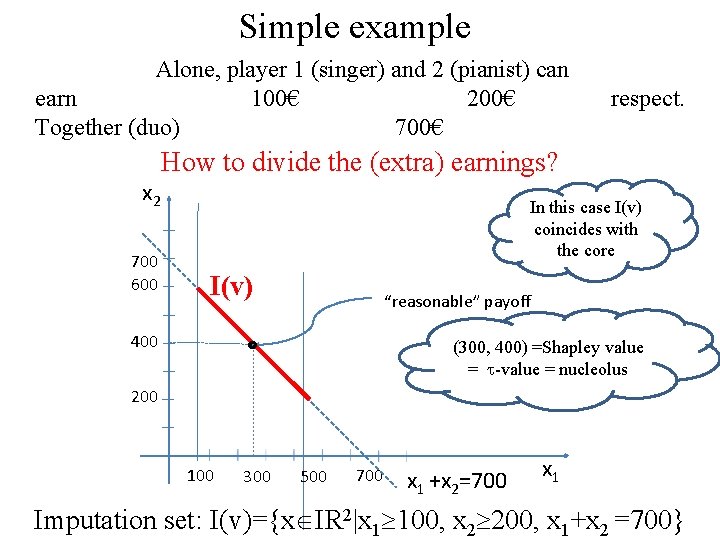

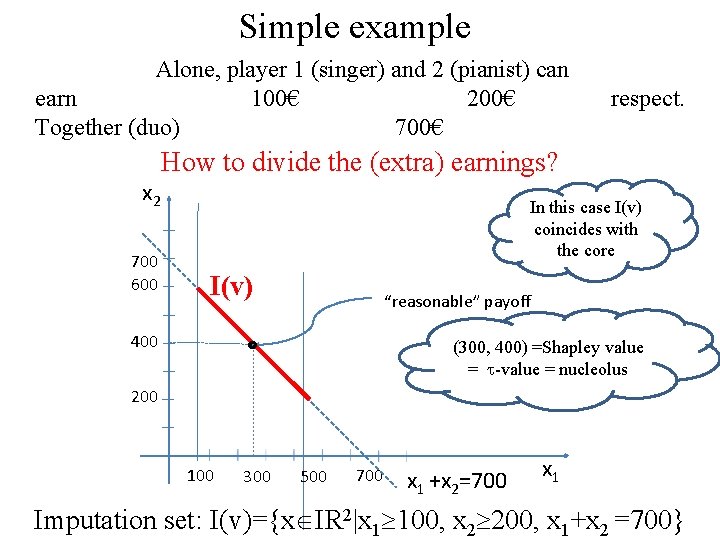

Simple example Alone, player 1 (singer) and 2 (pianist) can earn 100€ 200€ Together (duo) 700€ respect. How to divide the (extra) earnings? x 2 700 600 In this case I(v) coincides with the core I(v) “reasonable” payoff 400 (300, 400) =Shapley value = -value = nucleolus 200 100 300 500 700 x 1 +x 2=700 x 1 Imputation set: I(v)={x IR 2|x 1 100, x 2 200, x 1+x 2 =700}

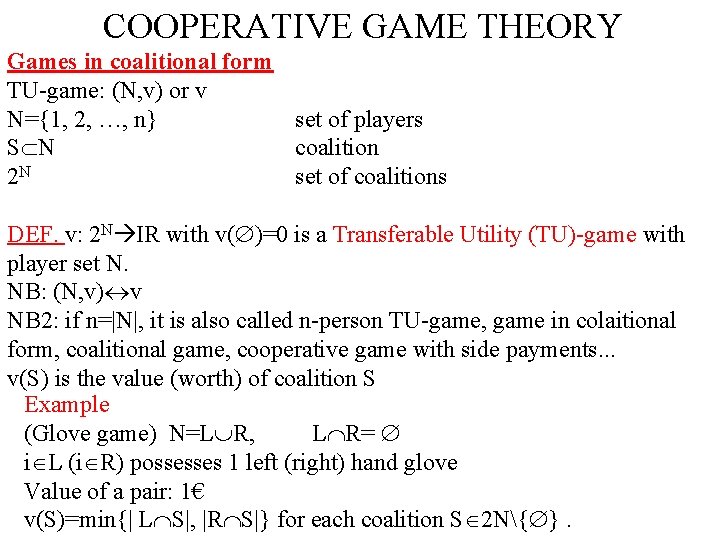

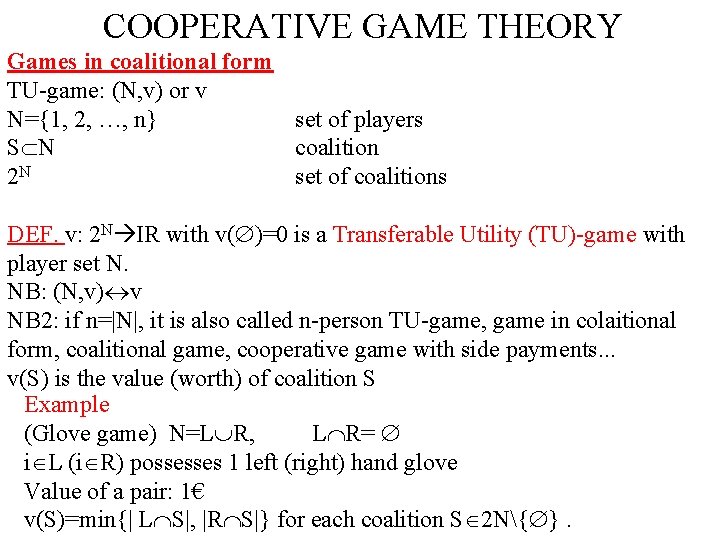

COOPERATIVE GAME THEORY Games in coalitional form TU-game: (N, v) or v N={1, 2, …, n} set of players S N coalition 2 N set of coalitions DEF. v: 2 N IR with v( )=0 is a Transferable Utility (TU)-game with player set N. NB: (N, v) v NB 2: if n=|N|, it is also called n-person TU-game, game in colaitional form, coalitional game, cooperative game with side payments. . . v(S) is the value (worth) of coalition S Example (Glove game) N=L R, L R= i L (i R) possesses 1 left (right) hand glove Value of a pair: 1€ v(S)=min{| L S|, |R S|} for each coalition S 2 N{ }.

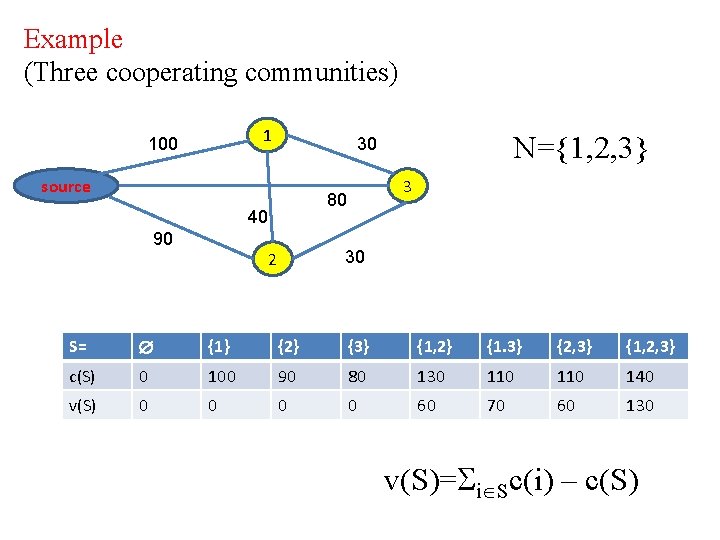

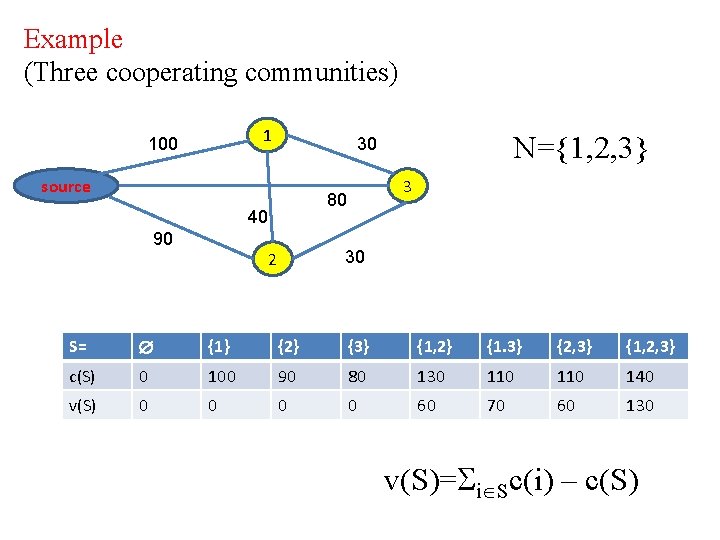

Example (Three cooperating communities) 1 100 source 3 80 40 90 N={1, 2, 3} 30 30 2 S= {1} {2} {3} {1, 2} {1. 3} {2, 3} {1, 2, 3} c(S) 0 100 90 80 130 110 140 v(S) 0 0 60 70 60 130 v(S)= i Sc(i) – c(S)

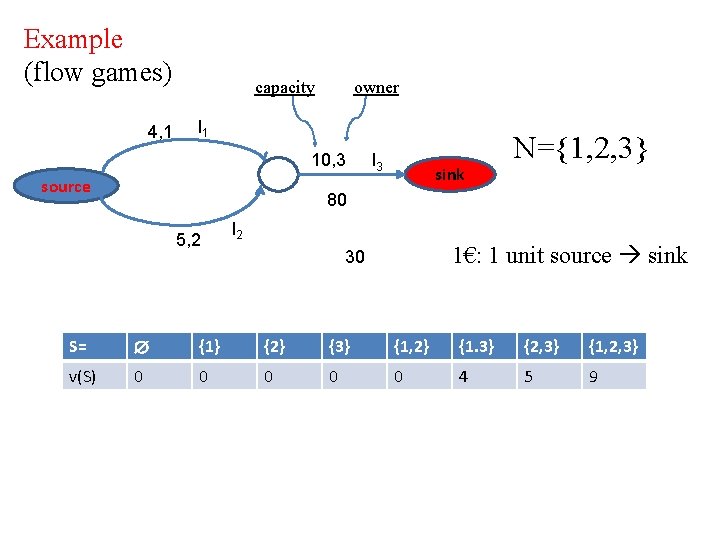

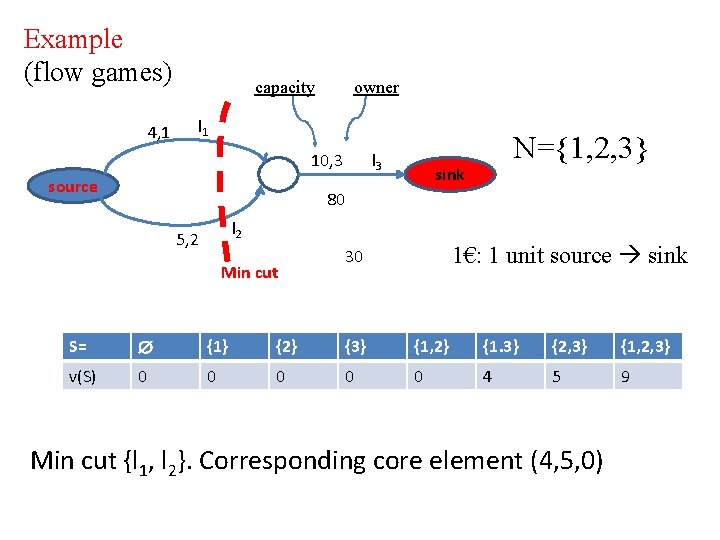

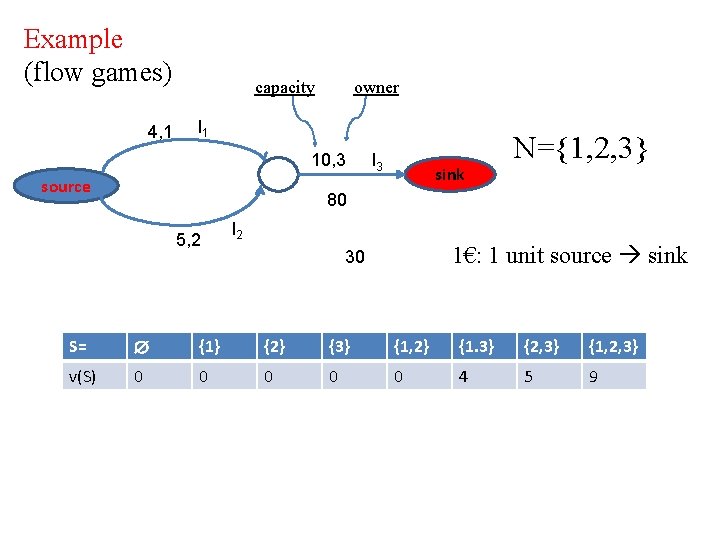

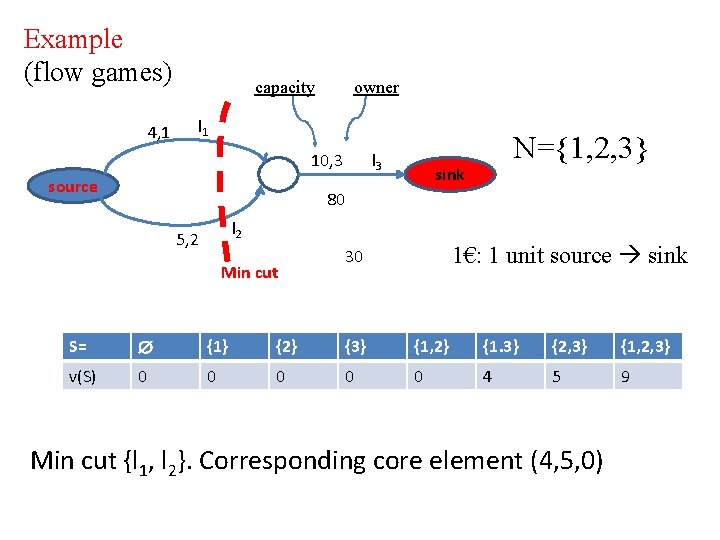

Example (flow games) 4, 1 capacity owner l 1 10, 3 source l 3 sink N={1, 2, 3} 80 5, 2 l 2 1€: 1 unit source sink 30 S= {1} {2} {3} {1, 2} {1. 3} {2, 3} {1, 2, 3} v(S) 0 0 0 4 5 9

DEF. (N, v) is a superadditive game iff v(S T) v(S)+v(T) for all S, T with S T= Q. 1: which coalitions form? Q. 2: If the grand coalition N forms, how to divide v(N)? (how to allocate costs? ) Many answers! (solution concepts) One-point concepts: - Shapley value (Shapley 1953) - nucleolus (Schmeidler 1969) - τ-value (Tijs, 1981) … Subset concepts: - Core (Gillies, 1954) - stable sets (von Neumann, Morgenstern, ’ 44) - kernel (Davis, Maschler) - bargaining set (Aumann, Maschler) …. .

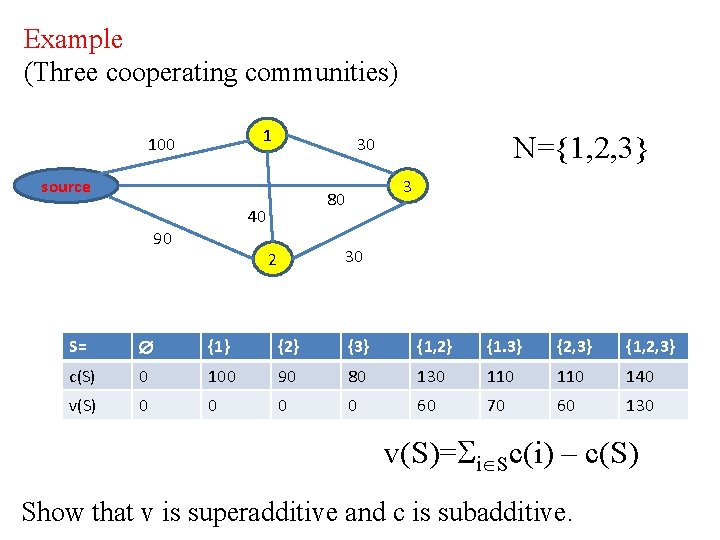

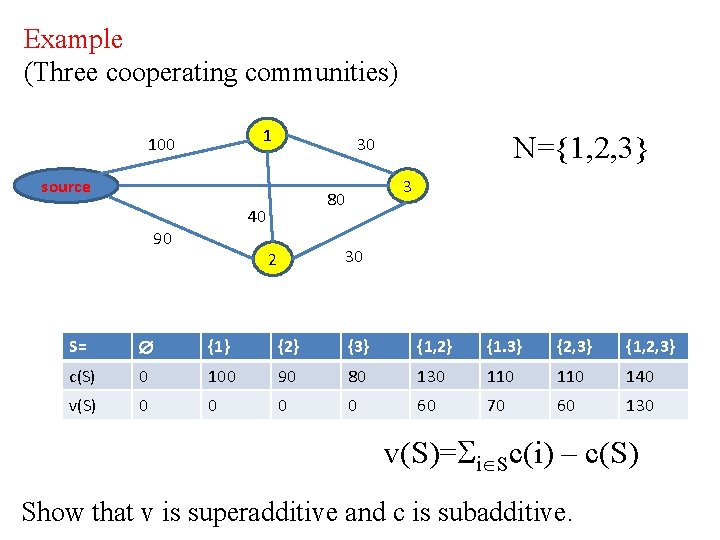

Example (Three cooperating communities) 1 100 source 3 80 40 90 N={1, 2, 3} 30 30 2 S= {1} {2} {3} {1, 2} {1. 3} {2, 3} {1, 2, 3} c(S) 0 100 90 80 130 110 140 v(S) 0 0 60 70 60 130 v(S)= i Sc(i) – c(S) Show that v is superadditive and c is subadditive.

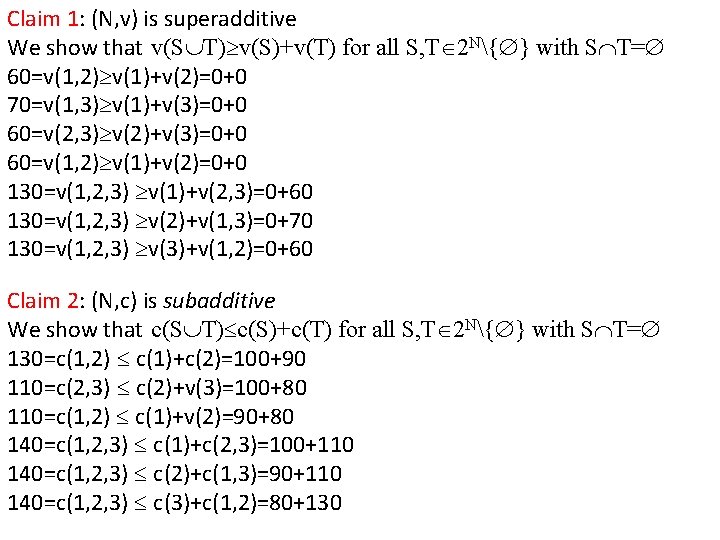

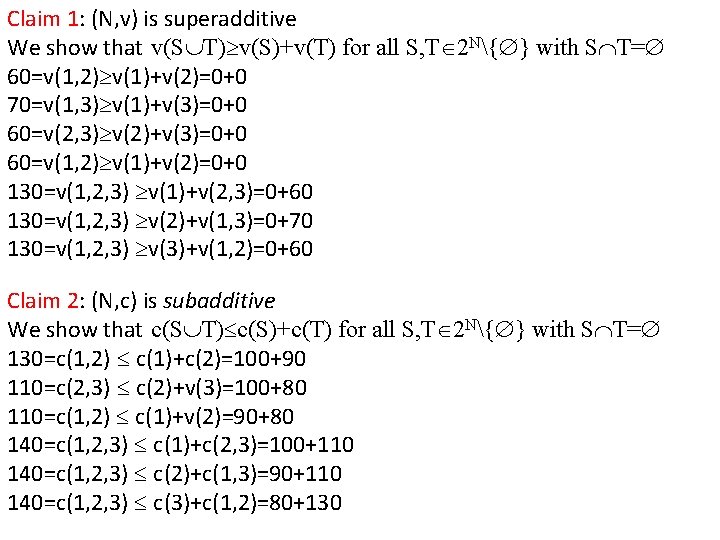

Claim 1: (N, v) is superadditive We show that v(S T) v(S)+v(T) for all S, T 2 N{ } with S T= 60=v(1, 2) v(1)+v(2)=0+0 70=v(1, 3) v(1)+v(3)=0+0 60=v(2, 3) v(2)+v(3)=0+0 60=v(1, 2) v(1)+v(2)=0+0 130=v(1, 2, 3) v(1)+v(2, 3)=0+60 130=v(1, 2, 3) v(2)+v(1, 3)=0+70 130=v(1, 2, 3) v(3)+v(1, 2)=0+60 Claim 2: (N, c) is subadditive We show that c(S T) c(S)+c(T) for all S, T 2 N{ } with S T= 130=c(1, 2) c(1)+c(2)=100+90 110=c(2, 3) c(2)+v(3)=100+80 110=c(1, 2) c(1)+v(2)=90+80 140=c(1, 2, 3) c(1)+c(2, 3)=100+110 140=c(1, 2, 3) c(2)+c(1, 3)=90+110 140=c(1, 2, 3) c(3)+c(1, 2)=80+130

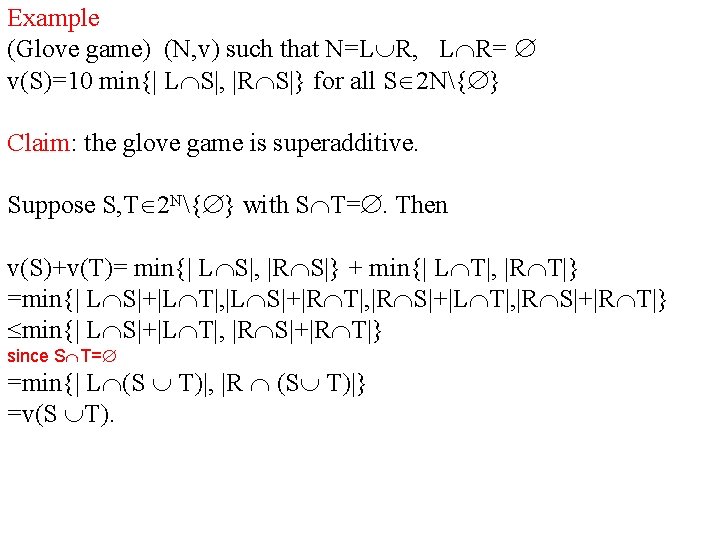

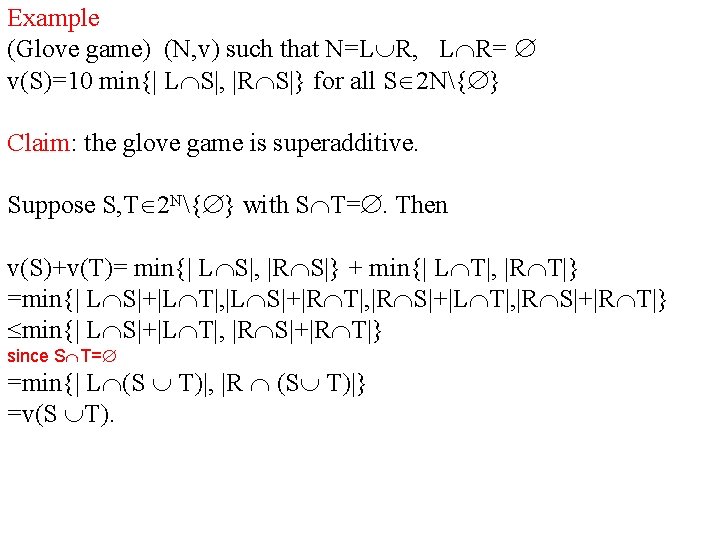

Example (Glove game) (N, v) such that N=L R, L R= v(S)=10 min{| L S|, |R S|} for all S 2 N{ } Claim: the glove game is superadditive. Suppose S, T 2 N{ } with S T=. Then v(S)+v(T)= min{| L S|, |R S|} + min{| L T|, |R T|} =min{| L S|+|L T|, |L S|+|R T|, |R S|+|L T|, |R S|+|R T|} min{| L S|+|L T|, |R S|+|R T|} since S T= =min{| L (S T)|, |R (S T)|} =v(S T).

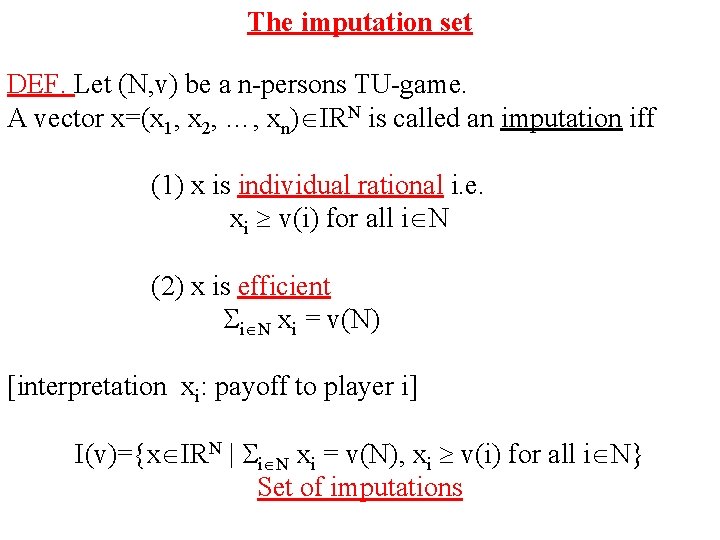

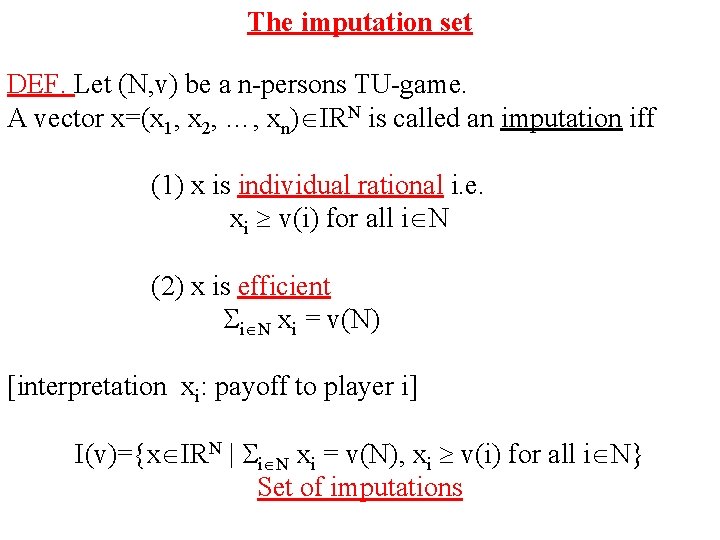

The imputation set DEF. Let (N, v) be a n-persons TU-game. A vector x=(x 1, x 2, …, xn) IRN is called an imputation iff (1) x is individual rational i. e. xi v(i) for all i N (2) x is efficient i N xi = v(N) [interpretation xi: payoff to player i] I(v)={x IRN | i N xi = v(N), xi v(i) for all i N} Set of imputations

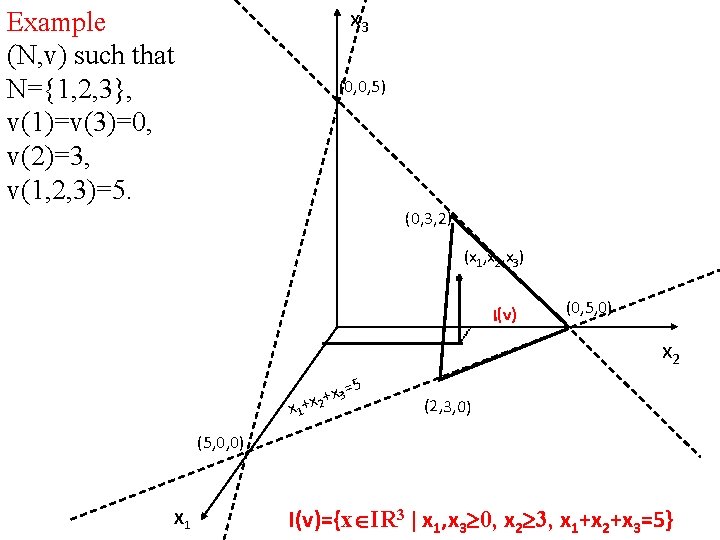

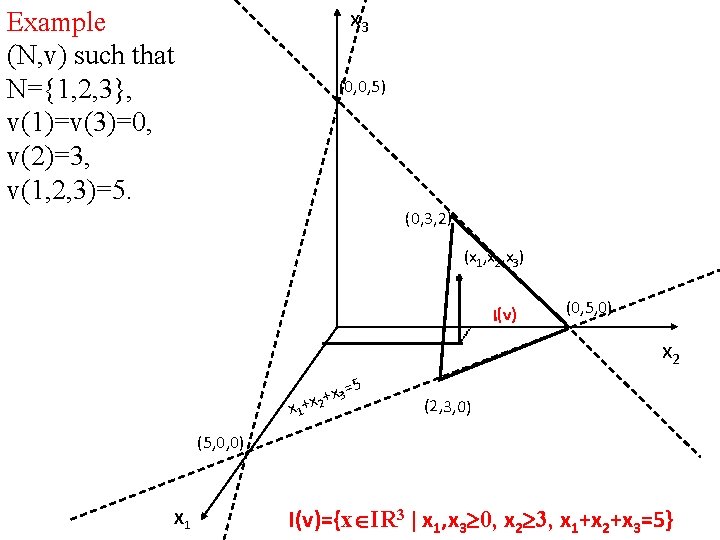

x 3 Example (N, v) such that N={1, 2, 3}, v(1)=v(3)=0, v(2)=3, v(1, 2, 3)=5. (0, 0, 5) (0, 3, 2) (x 1, x 2, x 3) I(v) (0, 5, 0) x 2 =5 x 3 + +x 2 x 1 (2, 3, 0) (5, 0, 0) X 1 I(v)={x IR 3 | x 1, x 3 0, x 2 3, x 1+x 2+x 3=5}

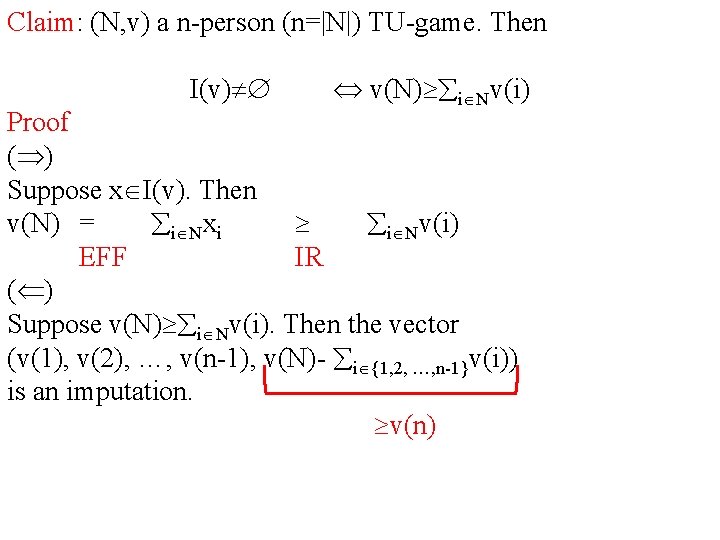

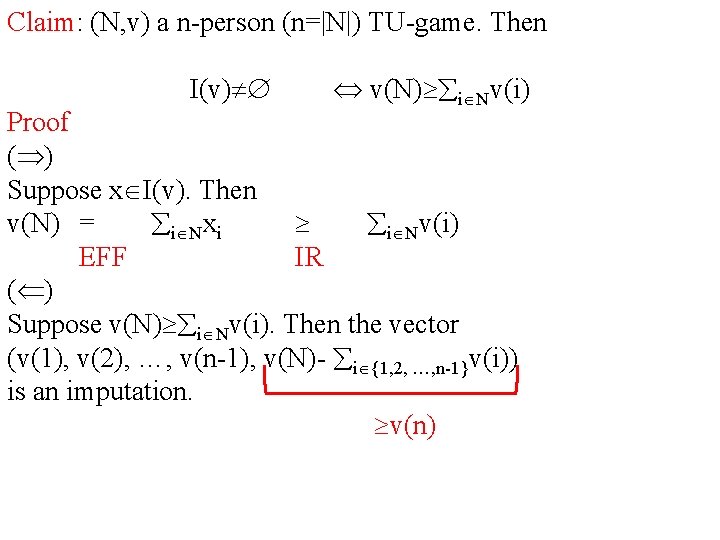

Claim: (N, v) a n-person (n=|N|) TU-game. Then I(v) v(N) i Nv(i) Proof ( ) Suppose x I(v). Then v(N) = i Nxi i Nv(i) EFF IR ( ) Suppose v(N) i Nv(i). Then the vector (v(1), v(2), …, v(n-1), v(N)- i {1, 2, …, n-1}v(i)) is an imputation. v(n)

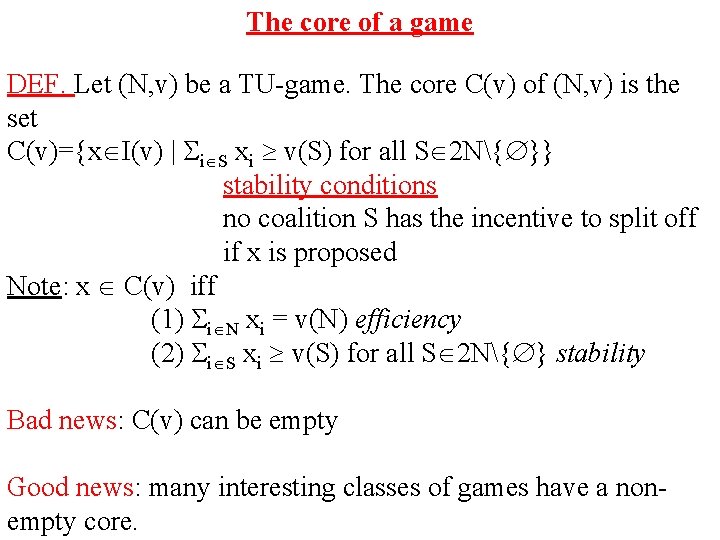

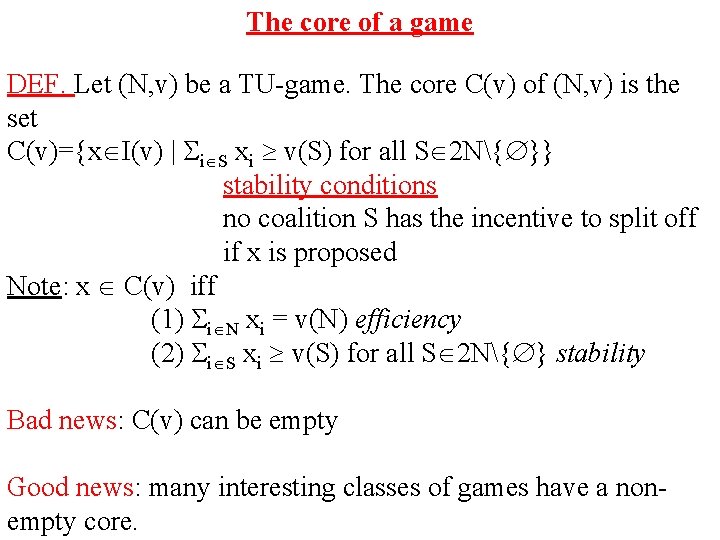

The core of a game DEF. Let (N, v) be a TU-game. The core C(v) of (N, v) is the set C(v)={x I(v) | i S xi v(S) for all S 2 N{ }} stability conditions no coalition S has the incentive to split off if x is proposed Note: x C(v) iff (1) i N xi = v(N) efficiency (2) i S xi v(S) for all S 2 N{ } stability Bad news: C(v) can be empty Good news: many interesting classes of games have a nonempty core.

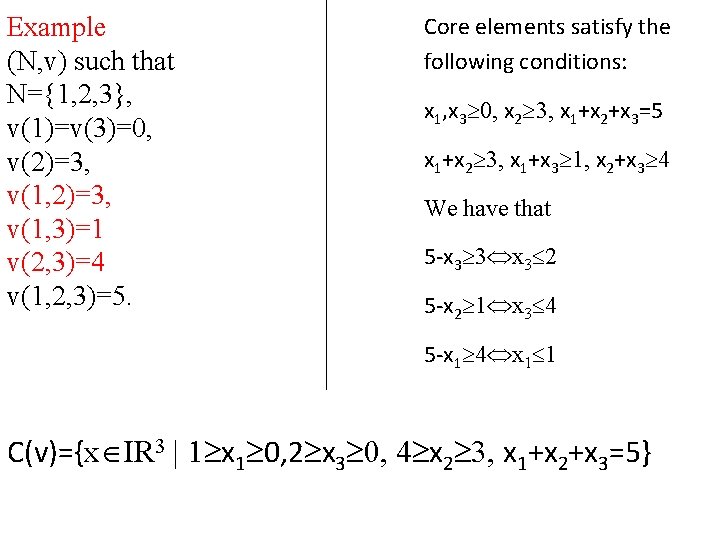

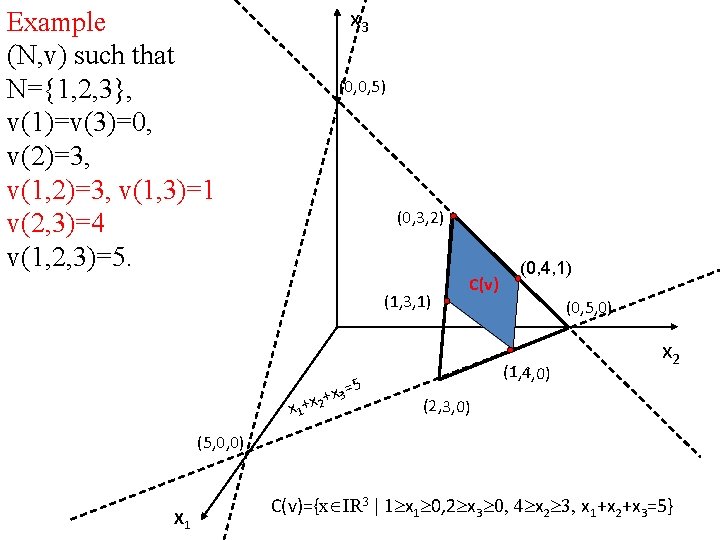

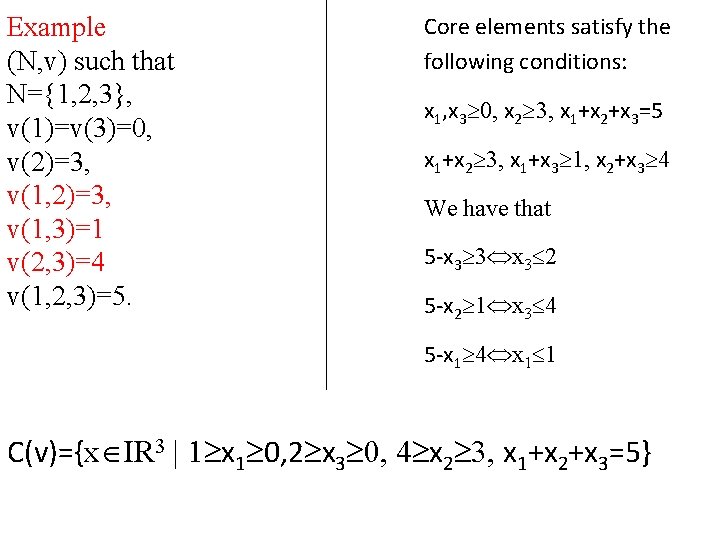

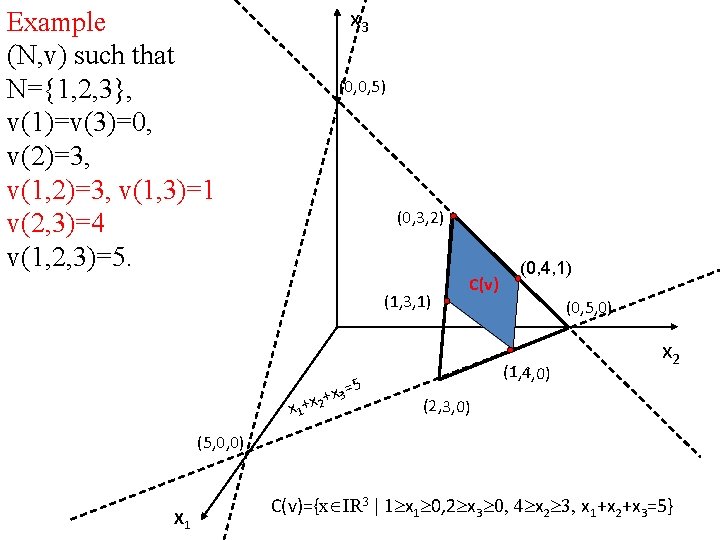

Example (N, v) such that N={1, 2, 3}, v(1)=v(3)=0, v(2)=3, v(1, 3)=1 v(2, 3)=4 v(1, 2, 3)=5. Core elements satisfy the following conditions: x 1, x 3 0, x 2 3, x 1+x 2+x 3=5 x 1+x 2 3, x 1+x 3 1, x 2+x 3 4 We have that 5 -x 3 3 x 3 2 5 -x 2 1 x 3 4 5 -x 1 4 x 1 1 C(v)={x IR 3 | 1 x 1 0, 2 x 3 0, 4 x 2 3, x 1+x 2+x 3=5}

x 3 Example (N, v) such that N={1, 2, 3}, v(1)=v(3)=0, v(2)=3, v(1, 3)=1 v(2, 3)=4 v(1, 2, 3)=5. (0, 0, 5) (0, 3, 2) (1, 3, 1) 5 +x 3= x 1+x 2 C(v) (0, 4, 1) (0, 5, 0) (1, 4, 0) x 2 (2, 3, 0) (5, 0, 0) X 1 C(v)={x IR 3 | 1 x 1 0, 2 x 3 0, 4 x 2 3, x 1+x 2+x 3=5}

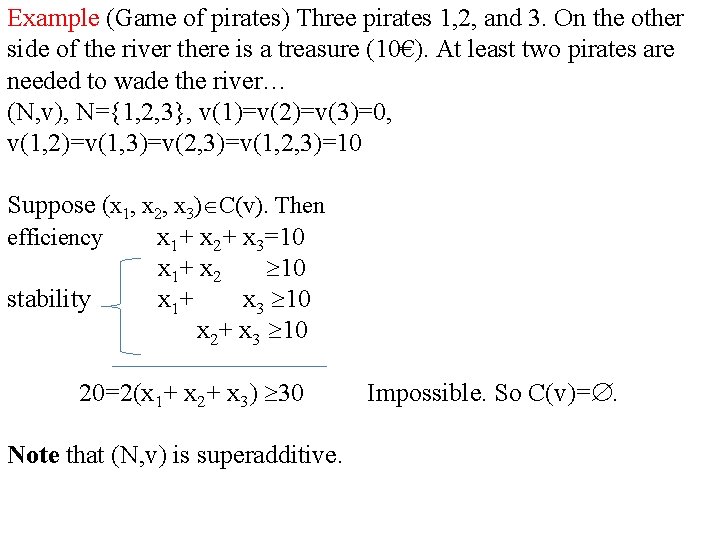

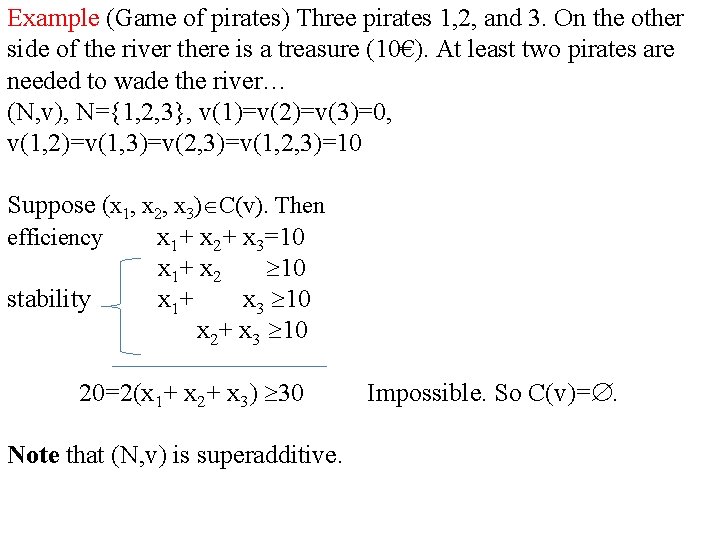

Example (Game of pirates) Three pirates 1, 2, and 3. On the other side of the river there is a treasure (10€). At least two pirates are needed to wade the river… (N, v), N={1, 2, 3}, v(1)=v(2)=v(3)=0, v(1, 2)=v(1, 3)=v(2, 3)=v(1, 2, 3)=10 Suppose (x 1, x 2, x 3) C(v). Then efficiency x 1+ x 2+ x 3=10 x 1+ x 2 10 stability x 1+ x 3 10 x 2+ x 3 10 20=2(x 1+ x 2+ x 3) 30 Note that (N, v) is superadditive. Impossible. So C(v)=.

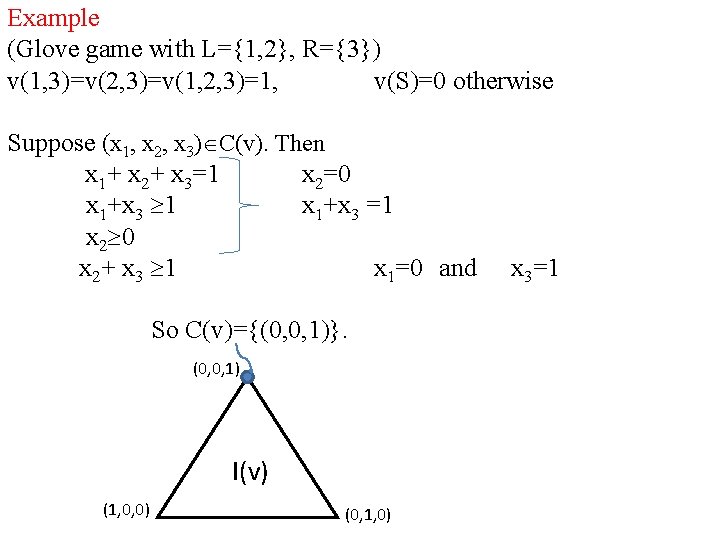

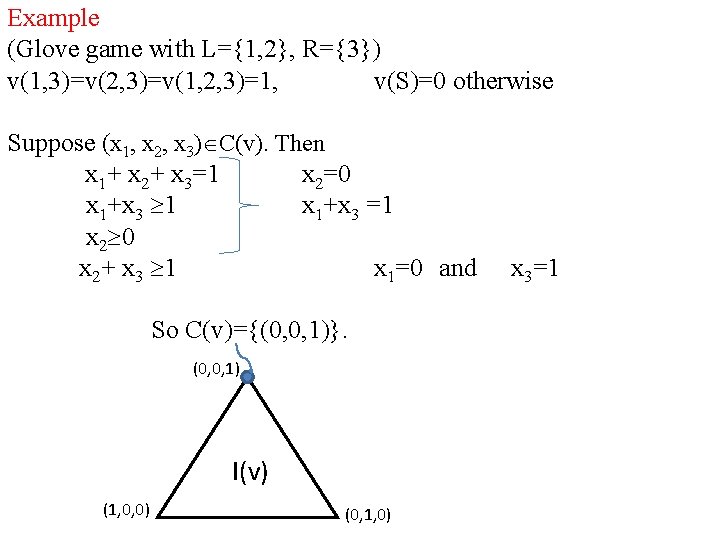

Example (Glove game with L={1, 2}, R={3}) v(1, 3)=v(2, 3)=v(1, 2, 3)=1, v(S)=0 otherwise Suppose (x 1, x 2, x 3) C(v). Then x 1+ x 2+ x 3=1 x 2=0 x 1+x 3 1 x 1+x 3 =1 x 2 0 x 2+ x 3 1 x 1=0 and So C(v)={(0, 0, 1)}. (0, 0, 1) I(v) (1, 0, 0) (0, 1, 0) x 3=1

Example (flow games) 4, 1 capacity owner l 1 10, 3 source l 3 N={1, 2, 3} sink 80 l 2 5, 2 Min cut 1€: 1 unit source sink 30 S= {1} {2} {3} {1, 2} {1. 3} {2, 3} {1, 2, 3} v(S) 0 0 0 4 5 9 Min cut {l 1, l 2}. Corresponding core element (4, 5, 0)

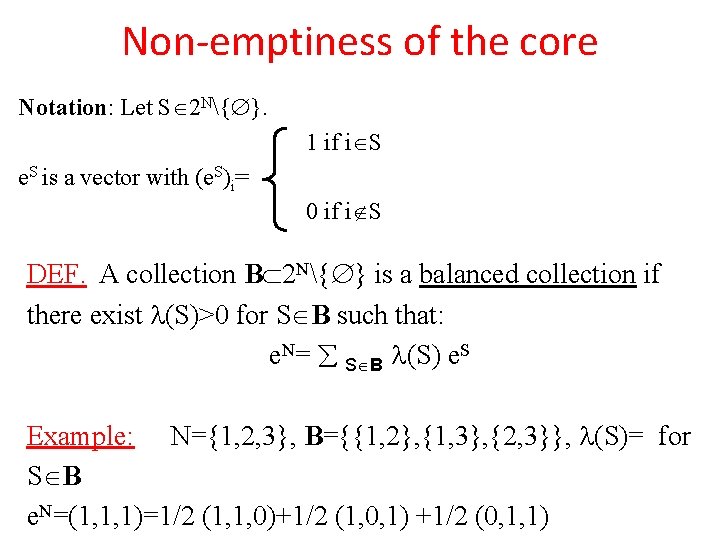

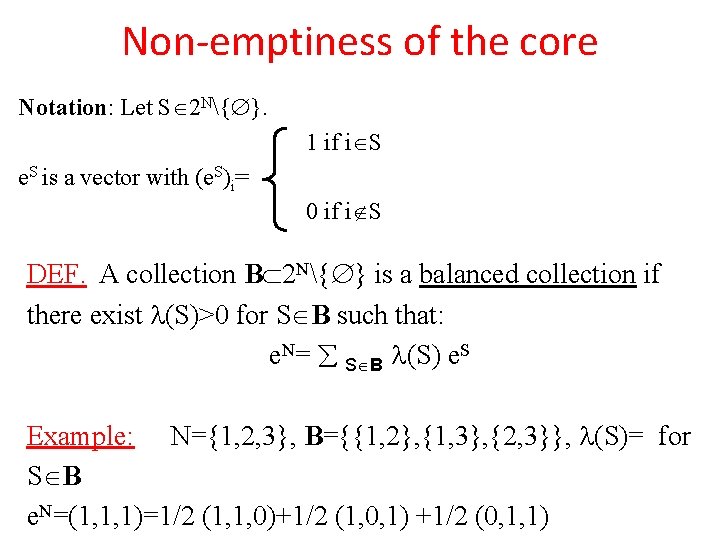

Non-emptiness of the core Notation: Let S 2 N{ }. 1 if i S e. S is a vector with (e. S)i= 0 if i S DEF. A collection B 2 N{ } is a balanced collection if there exist (S)>0 for S B such that: e. N= S B (S) e. S Example: N={1, 2, 3}, B={{1, 2}, {1, 3}, {2, 3}}, (S)= for S B e. N=(1, 1, 1)=1/2 (1, 1, 0)+1/2 (1, 0, 1) +1/2 (0, 1, 1)

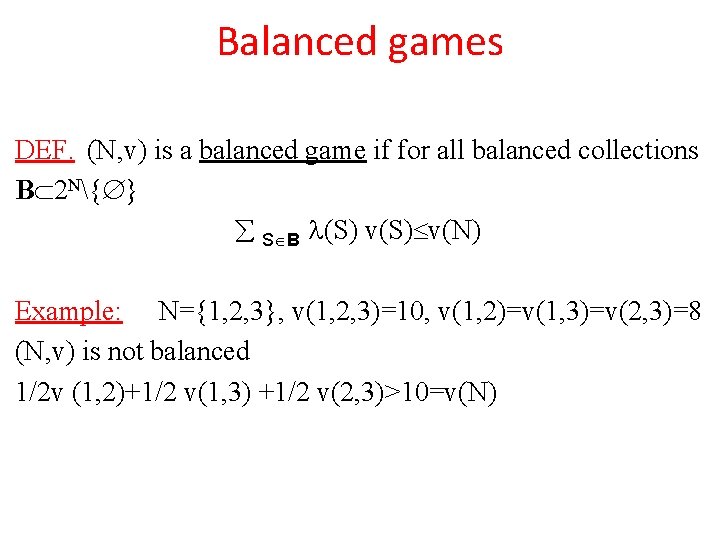

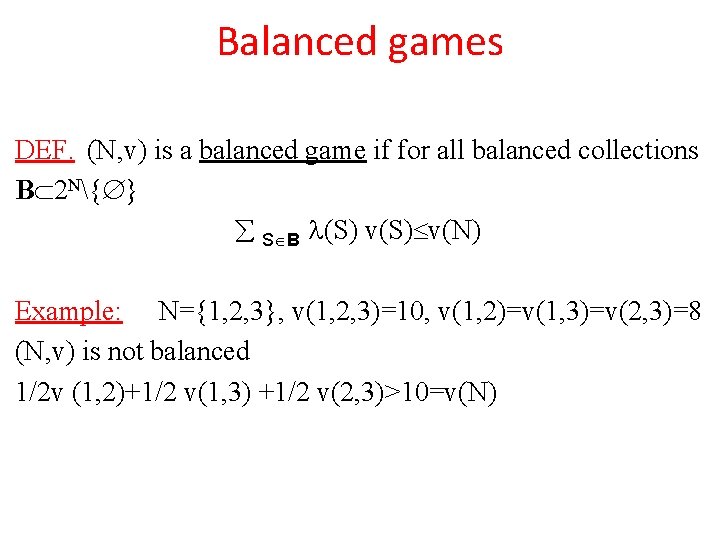

Balanced games DEF. (N, v) is a balanced game if for all balanced collections B 2 N{ } S B (S) v(N) Example: N={1, 2, 3}, v(1, 2, 3)=10, v(1, 2)=v(1, 3)=v(2, 3)=8 (N, v) is not balanced 1/2 v (1, 2)+1/2 v(1, 3) +1/2 v(2, 3)>10=v(N)

Variants of duality theorem Duality theorem. min{x. Tc|x. TA b} || max{b. Ty|Ay=c, y 0} y. T x A b. T (if both programs feasible) c

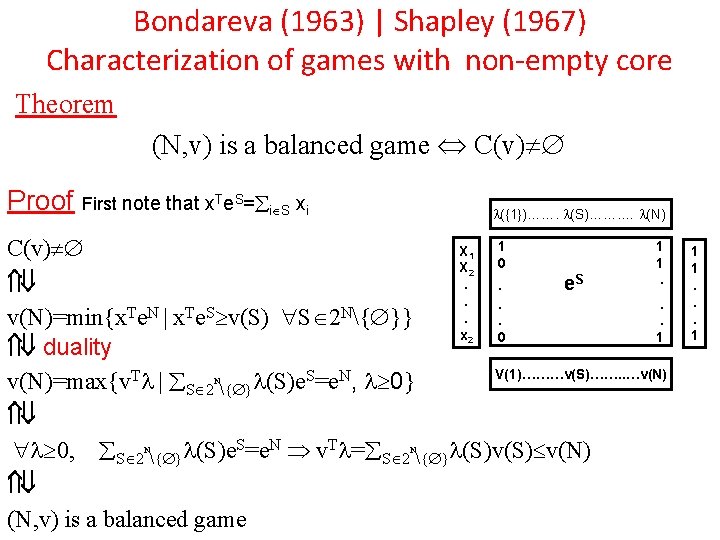

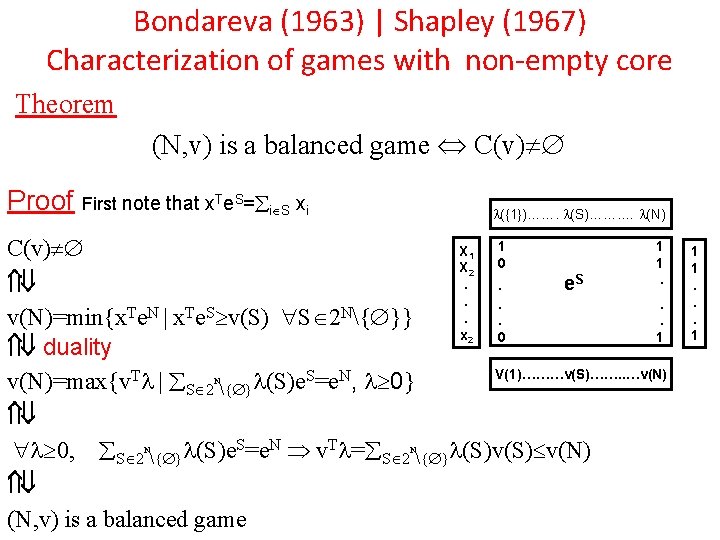

Bondareva (1963) | Shapley (1967) Characterization of games with non-empty core Theorem (N, v) is a balanced game C(v) Proof First note that x. Te. S= i S xi ({1})……. (S)……. … (N) 1 1 X C(v) 0 1 X. . . e. S . . . T N T S N. v(N)=min{x e | x e v(S) S 2 { }}. . x 0 1 duality V(1)………v(S)……. . …v(N)=max{v. T | S 2 { } (S)e. S=e. N, 0} 0, S 2 { } (S)e. S=e. N v. T = S 2 { } (S)v(S) v(N) (N, v) is a balanced game 1 2 2 N N N 1 1. . . 1

Convex games (1) DEF. An n-persons TU-game (N, v) is convex iff v(S)+v(T) v(S T)+v(S T) for each S, T 2 N. This condition is also known as submodularity. It can be rewritten as v(T)-v(S T)-v(S) for each S, T 2 N For each S, T 2 N, let C=(S T)S. Then we have: v(C (S T))-v(S T) v(C S)-v(S) Interpretation: the marginal contribution of a coalition C to a disjoint coalition S does not decrease if S becomes larger

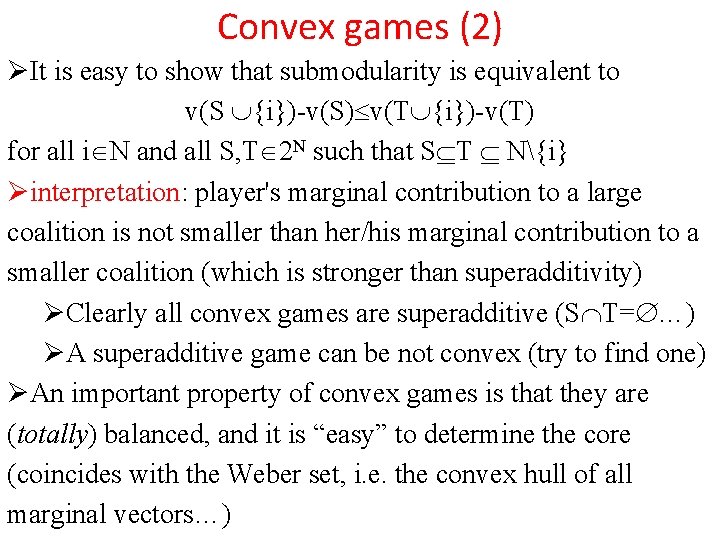

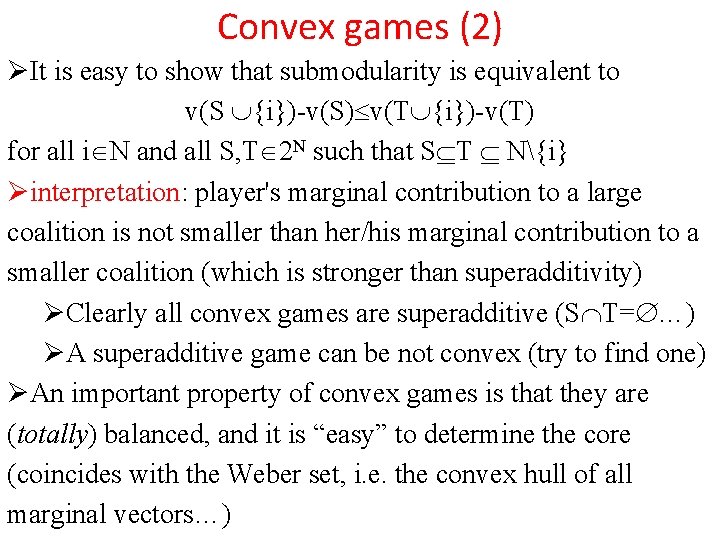

Convex games (2) ØIt is easy to show that submodularity is equivalent to v(S {i})-v(S) v(T {i})-v(T) for all i N and all S, T 2 N such that S T N{i} Øinterpretation: player's marginal contribution to a large coalition is not smaller than her/his marginal contribution to a smaller coalition (which is stronger than superadditivity) ØClearly all convex games are superadditive (S T= …) ØA superadditive game can be not convex (try to find one) ØAn important property of convex games is that they are (totally) balanced, and it is “easy” to determine the core (coincides with the Weber set, i. e. the convex hull of all marginal vectors…)

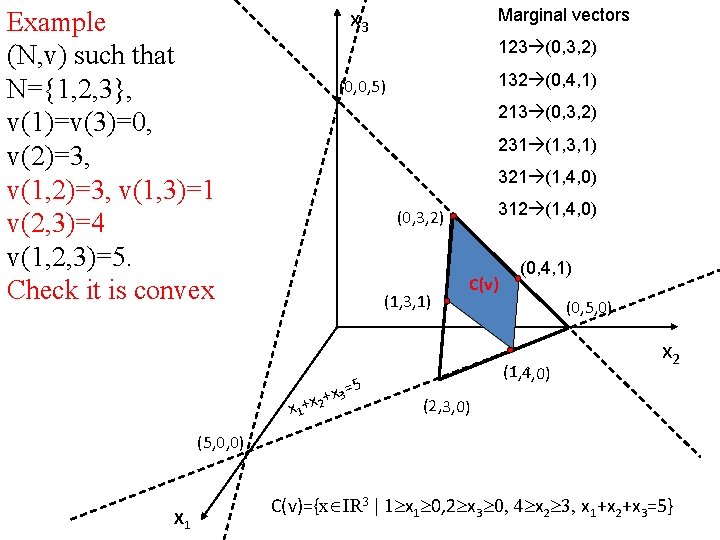

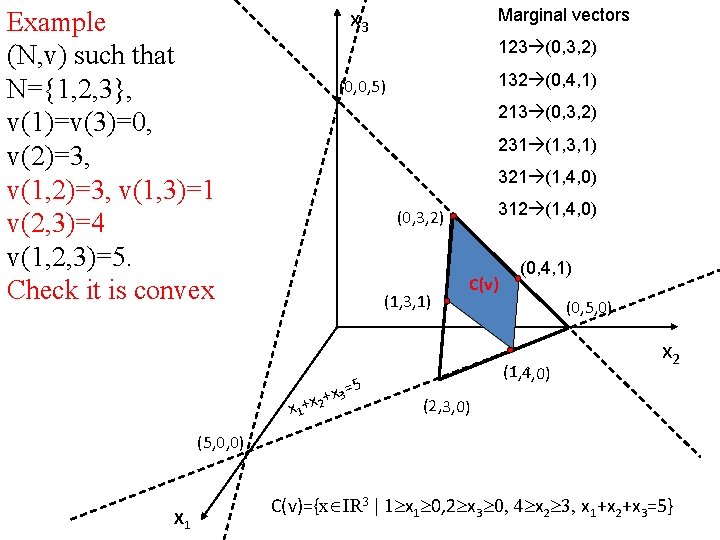

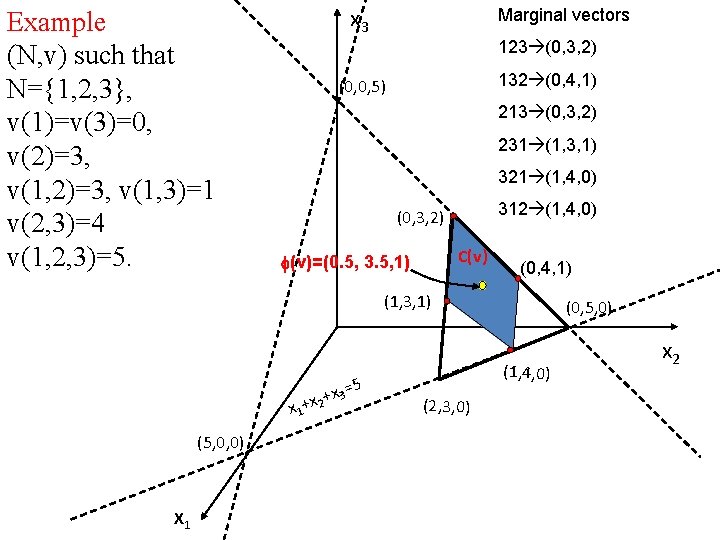

x 3 Example (N, v) such that N={1, 2, 3}, v(1)=v(3)=0, v(2)=3, v(1, 3)=1 v(2, 3)=4 v(1, 2, 3)=5. Check it is convex Marginal vectors 123 (0, 3, 2) 132 (0, 4, 1) (0, 0, 5) 213 (0, 3, 2) 231 (1, 3, 1) 321 (1, 4, 0) 312 (1, 4, 0) (0, 3, 2) (1, 3, 1) 5 +x 3= x 1+x 2 C(v) (0, 4, 1) (0, 5, 0) (1, 4, 0) x 2 (2, 3, 0) (5, 0, 0) X 1 C(v)={x IR 3 | 1 x 1 0, 2 x 3 0, 4 x 2 3, x 1+x 2+x 3=5}

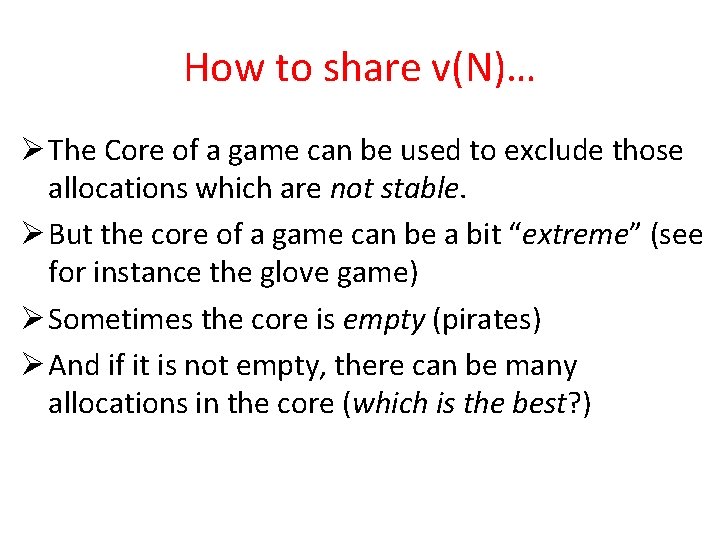

How to share v(N)… Ø The Core of a game can be used to exclude those allocations which are not stable. Ø But the core of a game can be a bit “extreme” (see for instance the glove game) Ø Sometimes the core is empty (pirates) Ø And if it is not empty, there can be many allocations in the core (which is the best? )

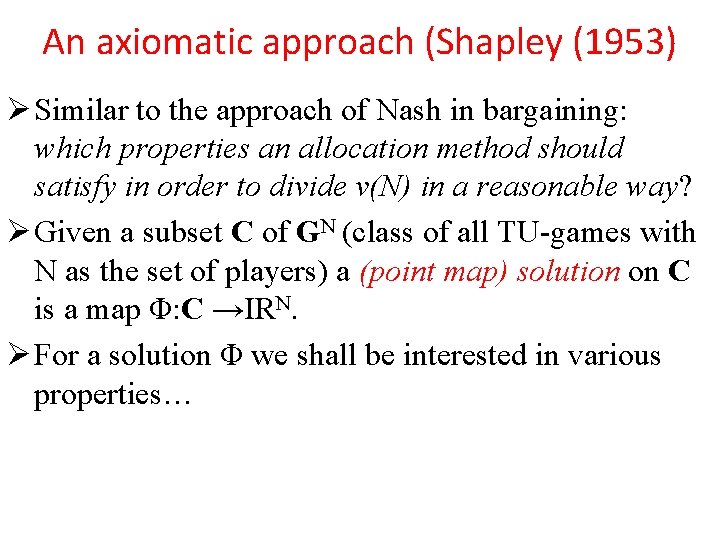

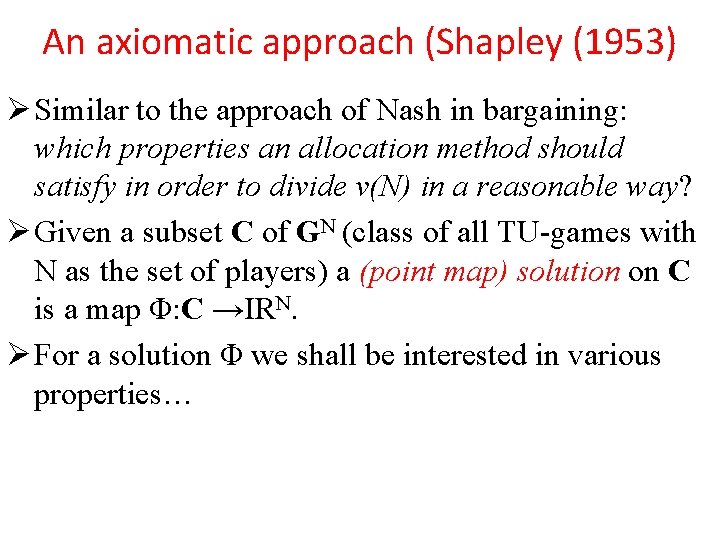

An axiomatic approach (Shapley (1953) Ø Similar to the approach of Nash in bargaining: which properties an allocation method should satisfy in order to divide v(N) in a reasonable way? Ø Given a subset C of GN (class of all TU-games with N as the set of players) a (point map) solution on C is a map Φ: C →IRN. Ø For a solution Φ we shall be interested in various properties…

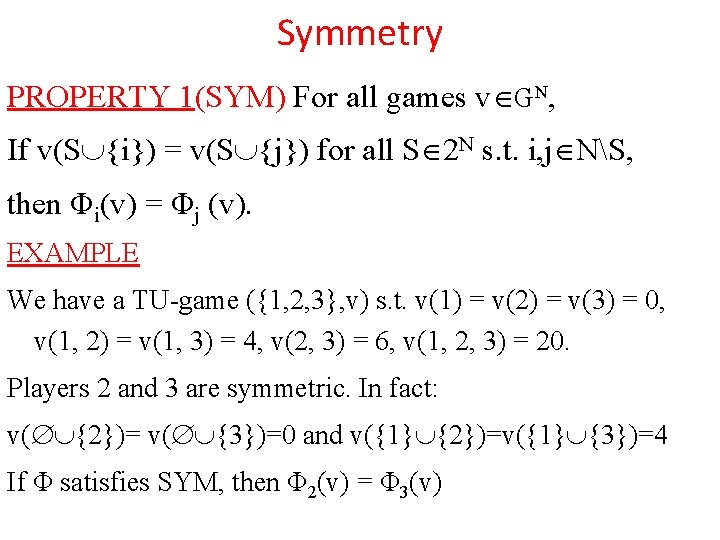

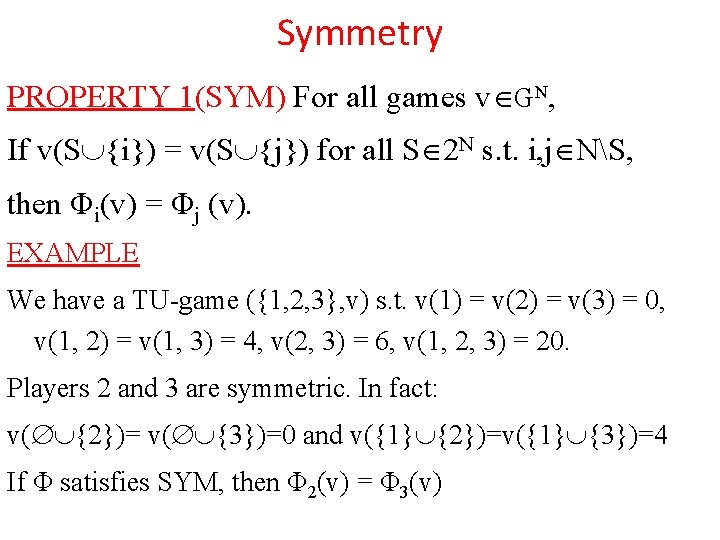

Symmetry PROPERTY 1(SYM) For all games v GN, If v(S {i}) = v(S {j}) for all S 2 N s. t. i, j NS, then Φi(v) = Φj (v). EXAMPLE We have a TU-game ({1, 2, 3}, v) s. t. v(1) = v(2) = v(3) = 0, v(1, 2) = v(1, 3) = 4, v(2, 3) = 6, v(1, 2, 3) = 20. Players 2 and 3 are symmetric. In fact: v( {2})= v( {3})=0 and v({1} {2})=v({1} {3})=4 If Φ satisfies SYM, then Φ 2(v) = Φ 3(v)

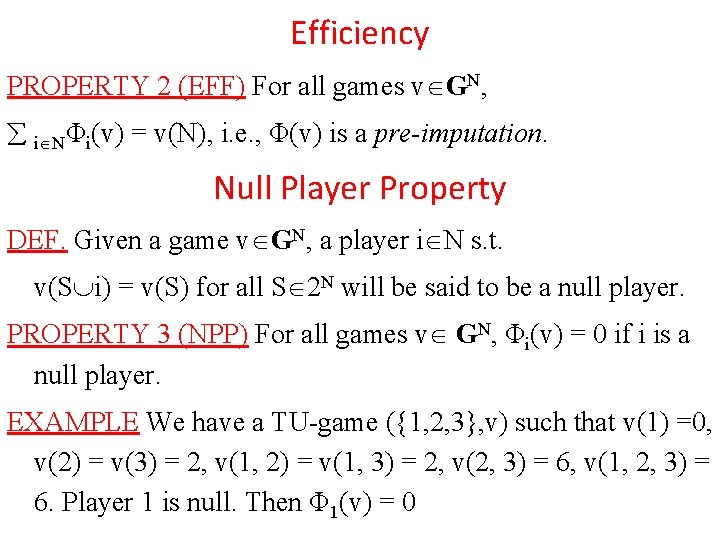

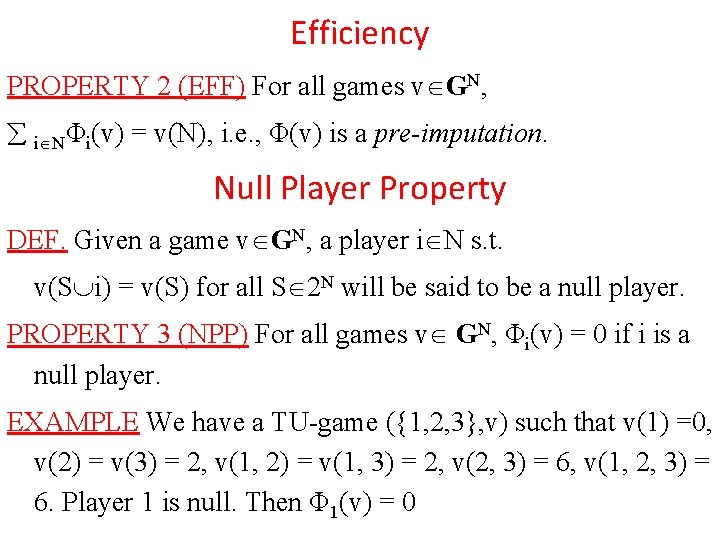

Efficiency PROPERTY 2 (EFF) For all games v GN, i NΦi(v) = v(N), i. e. , Φ(v) is a pre-imputation. Null Player Property DEF. Given a game v GN, a player i N s. t. v(S i) = v(S) for all S 2 N will be said to be a null player. PROPERTY 3 (NPP) For all games v GN, Φi(v) = 0 if i is a null player. EXAMPLE We have a TU-game ({1, 2, 3}, v) such that v(1) =0, v(2) = v(3) = 2, v(1, 2) = v(1, 3) = 2, v(2, 3) = 6, v(1, 2, 3) = 6. Player 1 is null. Then Φ 1(v) = 0

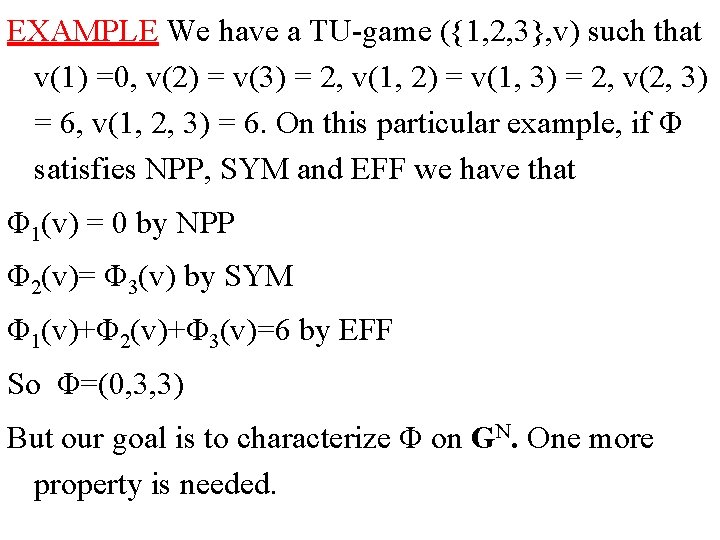

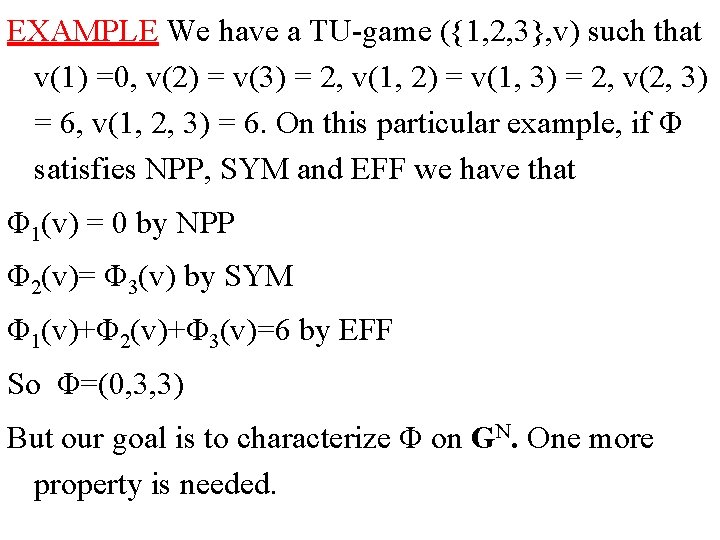

EXAMPLE We have a TU-game ({1, 2, 3}, v) such that v(1) =0, v(2) = v(3) = 2, v(1, 2) = v(1, 3) = 2, v(2, 3) = 6, v(1, 2, 3) = 6. On this particular example, if Φ satisfies NPP, SYM and EFF we have that Φ 1(v) = 0 by NPP Φ 2(v)= Φ 3(v) by SYM Φ 1(v)+Φ 2(v)+Φ 3(v)=6 by EFF So Φ=(0, 3, 3) But our goal is to characterize Φ on GN. One more property is needed.

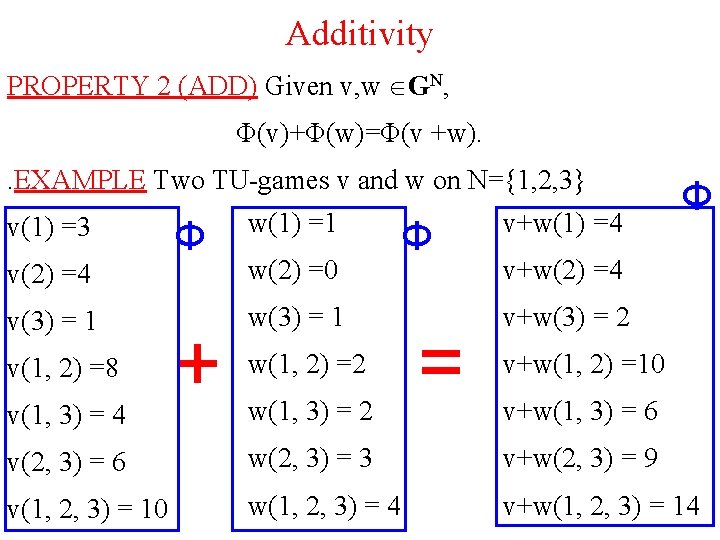

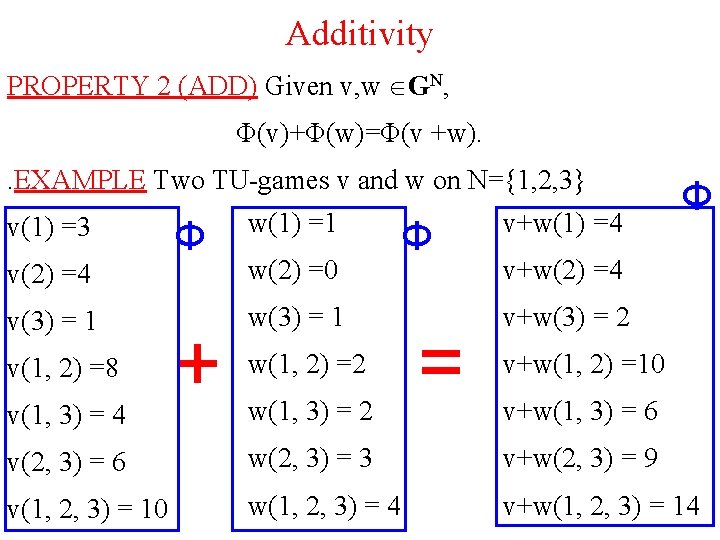

Additivity PROPERTY 2 (ADD) Given v, w GN, Φ(v)+Φ(w)=Φ(v +w). . EXAMPLE Two TU-games v and w on N={1, 2, 3} v(1) =3 v(2) =4 v(3) = 1 v(1, 2) =8 v(1, 3) = 4 Φ + w(1) =1 w(2) =0 w(3) = 1 w(1, 2) =2 w(1, 3) = 2 Φ = v+w(1) =4 Φ v+w(2) =4 v+w(3) = 2 v+w(1, 2) =10 v+w(1, 3) = 6 v(2, 3) = 6 w(2, 3) = 3 v+w(2, 3) = 9 v(1, 2, 3) = 10 w(1, 2, 3) = 4 v+w(1, 2, 3) = 14

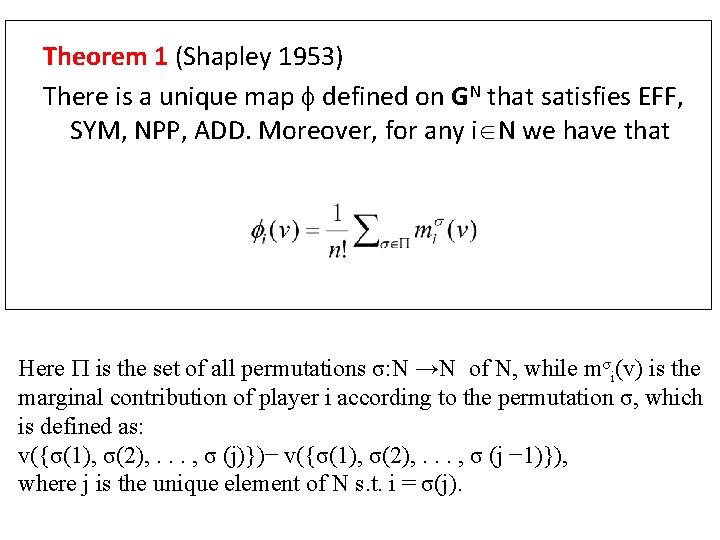

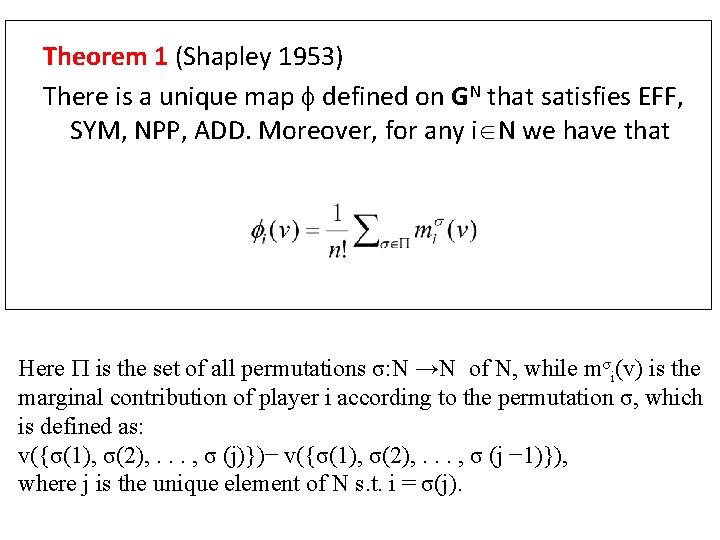

Theorem 1 (Shapley 1953) There is a unique map defined on GN that satisfies EFF, SYM, NPP, ADD. Moreover, for any i N we have that Here is the set of all permutations σ: N →N of N, while mσi(v) is the marginal contribution of player i according to the permutation σ, which is defined as: v({σ(1), σ(2), . . . , σ (j)})− v({σ(1), σ(2), . . . , σ (j − 1)}), where j is the unique element of N s. t. i = σ(j).

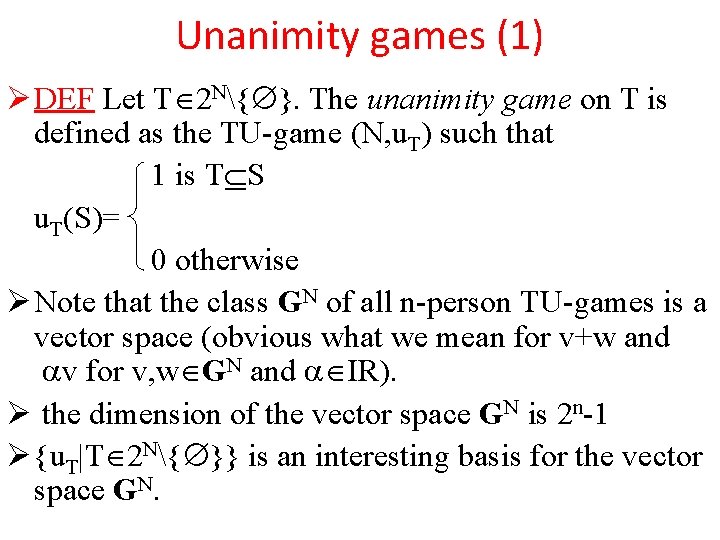

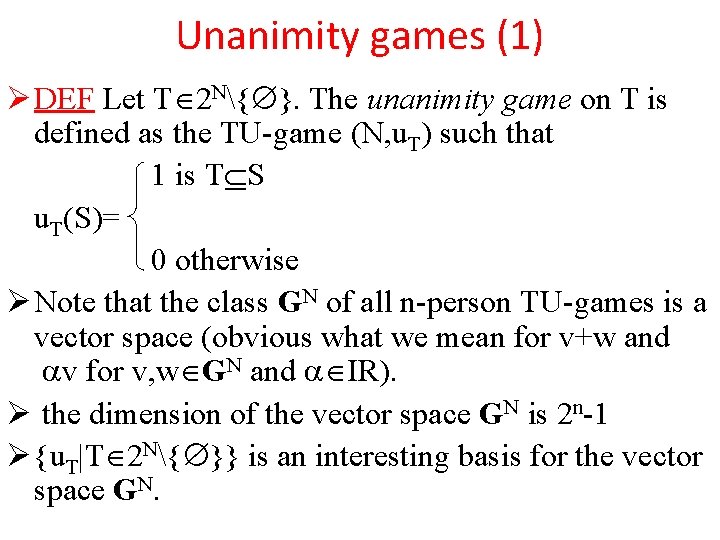

Unanimity games (1) Ø DEF Let T 2 N{ }. The unanimity game on T is defined as the TU-game (N, u. T) such that 1 is T S u. T(S)= 0 otherwise Ø Note that the class GN of all n-person TU-games is a vector space (obvious what we mean for v+w and v for v, w GN and IR). Ø the dimension of the vector space GN is 2 n-1 Ø {u. T|T 2 N{ }} is an interesting basis for the vector space GN.

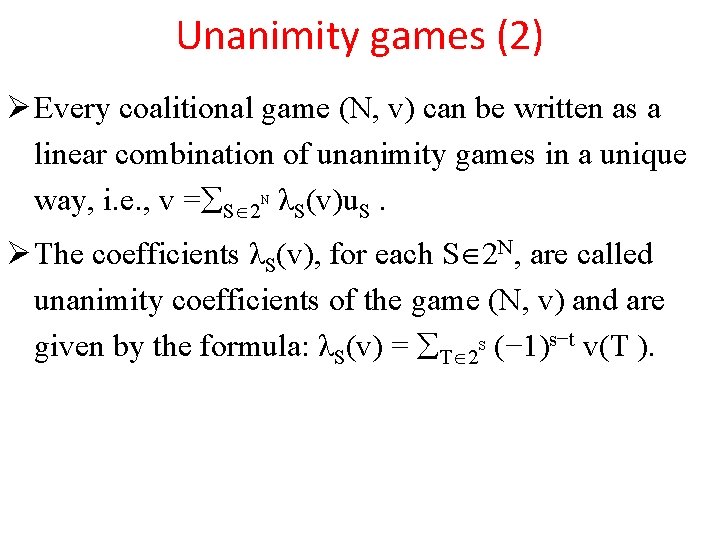

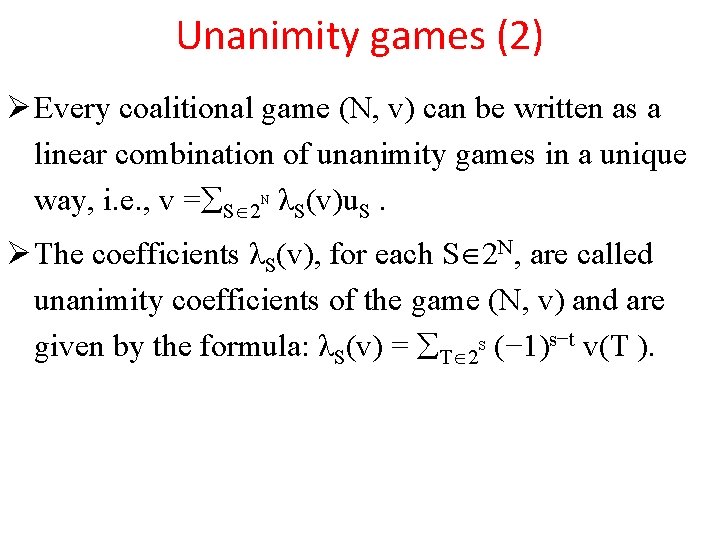

Unanimity games (2) Ø Every coalitional game (N, v) can be written as a linear combination of unanimity games in a unique way, i. e. , v = S 2 N λS(v)u. S. Ø The coefficients λS(v), for each S 2 N, are called unanimity coefficients of the game (N, v) and are given by the formula: λS(v) = T 2 S (− 1)s−t v(T ).

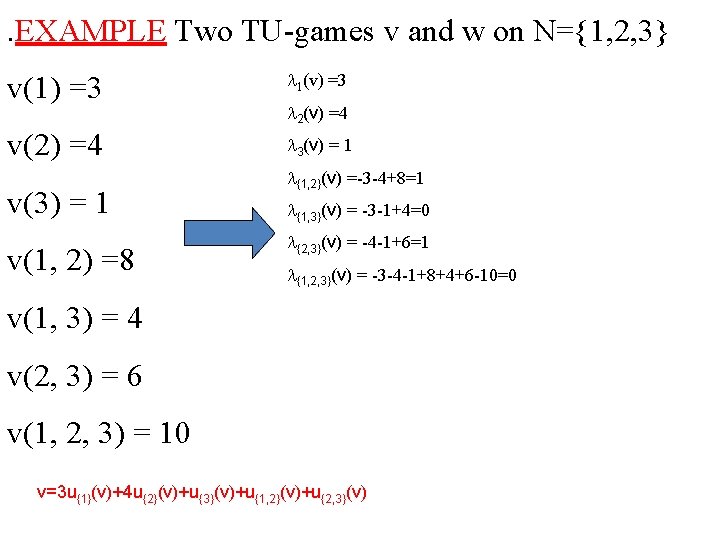

. EXAMPLE Two TU-games v and w on N={1, 2, 3} v(1) =3 1(v) =3 v(2) =4 3(v) = 1 v(3) = 1 v(1, 2) =8 2(v) =4 {1, 2}(v) =-3 -4+8=1 {1, 3}(v) = -3 -1+4=0 {2, 3}(v) = -4 -1+6=1 {1, 2, 3}(v) = -3 -4 -1+8+4+6 -10=0 v(1, 3) = 4 v(2, 3) = 6 v(1, 2, 3) = 10 v=3 u{1}(v)+4 u{2}(v)+u{3}(v)+u{1, 2}(v)+u{2, 3}(v)

Sketch of the Proof of Theorem 1 Ø Shapley value satisfies the four properties (easy). Ø Properties EFF, SYM, NPP determine on the class of all games αv, with v a unanimity game and α IR. ØLet S 2 N. The Shapley value of the unanimity game (N, u. S) is given by /|S| if i S i(αu. S)= 0 otherwise Ø Since the class of unanimity games is a basis for the vector space, ADD allows to extend in a unique way to GN.

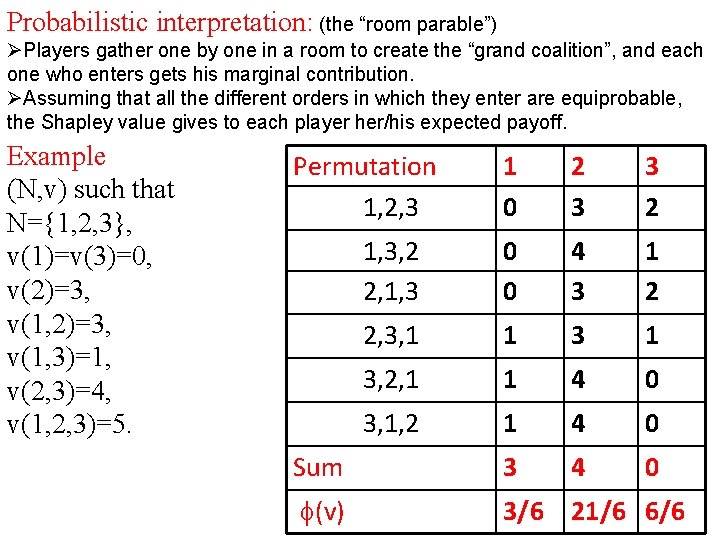

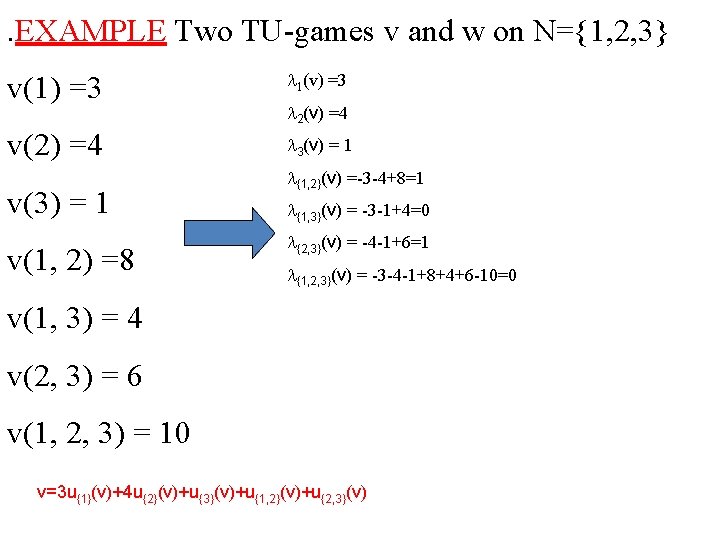

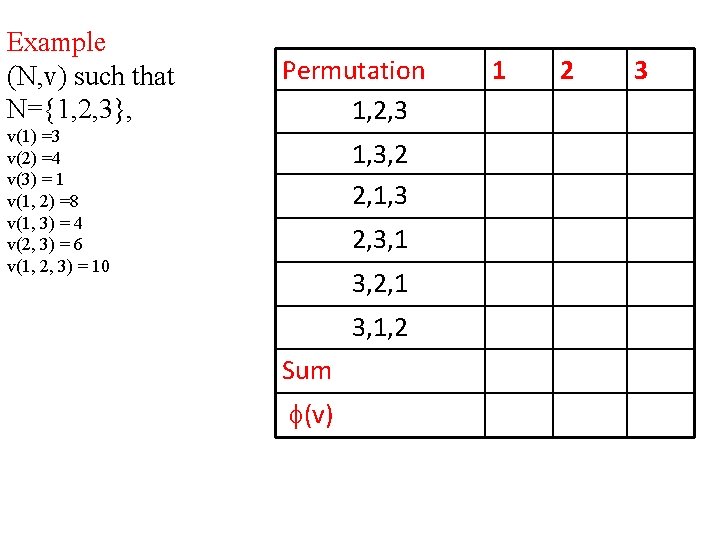

Probabilistic interpretation: (the “room parable”) ØPlayers gather one by one in a room to create the “grand coalition”, and each one who enters gets his marginal contribution. ØAssuming that all the different orders in which they enter are equiprobable, the Shapley value gives to each player her/his expected payoff. Example (N, v) such that N={1, 2, 3}, v(1)=v(3)=0, v(2)=3, v(1, 3)=1, v(2, 3)=4, v(1, 2, 3)=5. Permutation 1, 2, 3 1 0 2 3 3 2 1, 3, 2 2, 1, 3 0 0 4 3 1 2 2, 3, 1 1 3, 2, 1 1 4 0 3, 1, 2 1 4 0 Sum 3 4 0 (v) 3/6 21/6 6/6

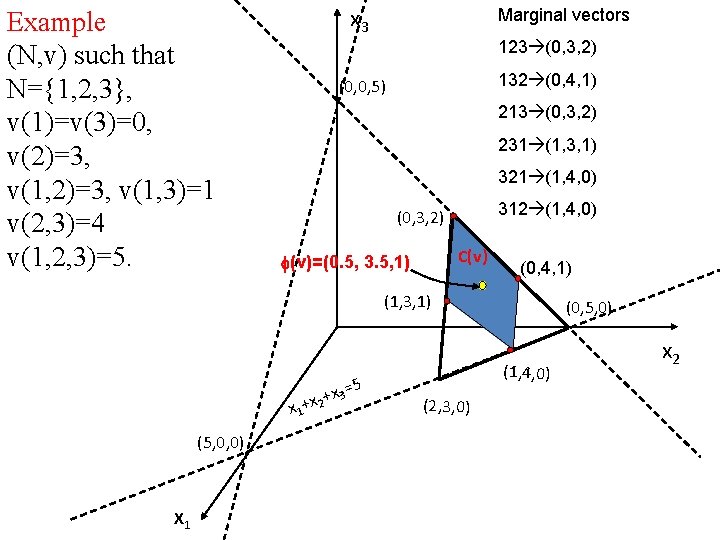

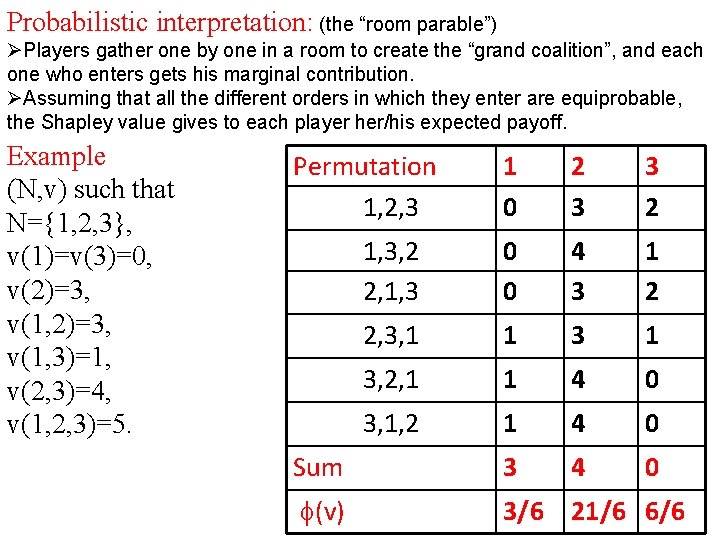

Example (N, v) such that N={1, 2, 3}, v(1)=v(3)=0, v(2)=3, v(1, 3)=1 v(2, 3)=4 v(1, 2, 3)=5. x 3 Marginal vectors 123 (0, 3, 2) 132 (0, 4, 1) (0, 0, 5) 213 (0, 3, 2) 231 (1, 3, 1) 321 (1, 4, 0) 312 (1, 4, 0) (0, 3, 2) C(v) (v)=(0. 5, 3. 5, 1) (0, 4, 1) (1, 3, 1) 5 +x 3= x 1+x 2 (5, 0, 0) X 1 (0, 5, 0) (1, 4, 0) (2, 3, 0) x 2

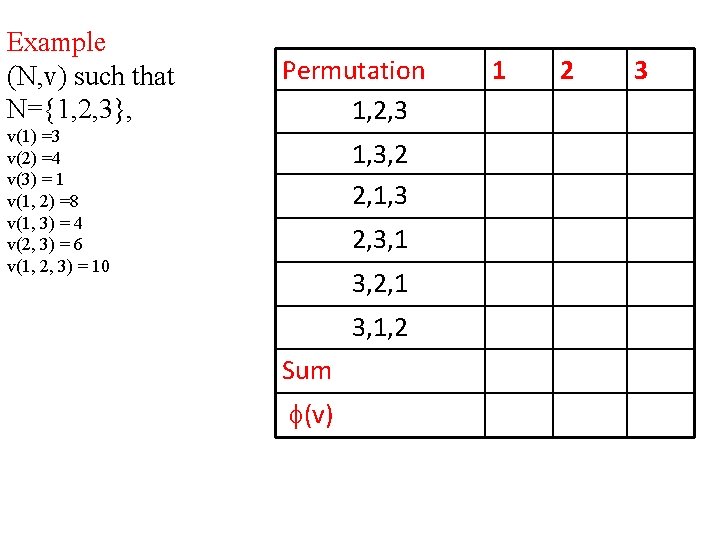

Example (N, v) such that N={1, 2, 3}, v(1) =3 v(2) =4 v(3) = 1 v(1, 2) =8 v(1, 3) = 4 v(2, 3) = 6 v(1, 2, 3) = 10 Permutation 1, 2, 3 1, 3, 2 2, 1, 3 2, 3, 1 3, 2, 1 3, 1, 2 Sum (v) 1 2 3

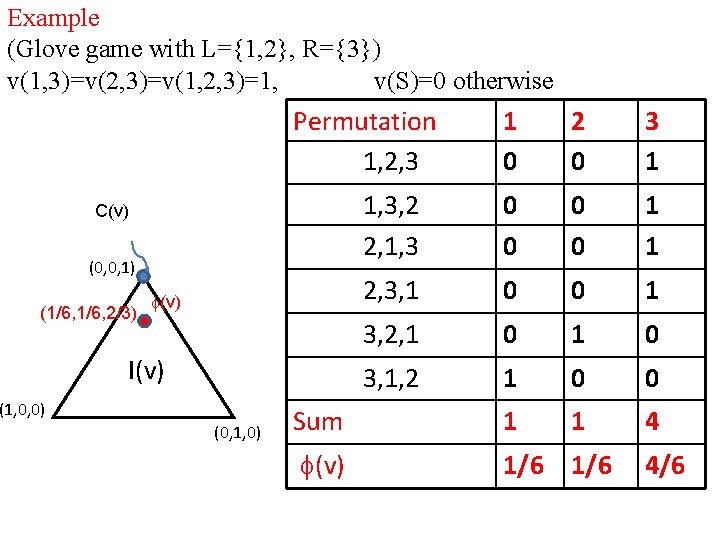

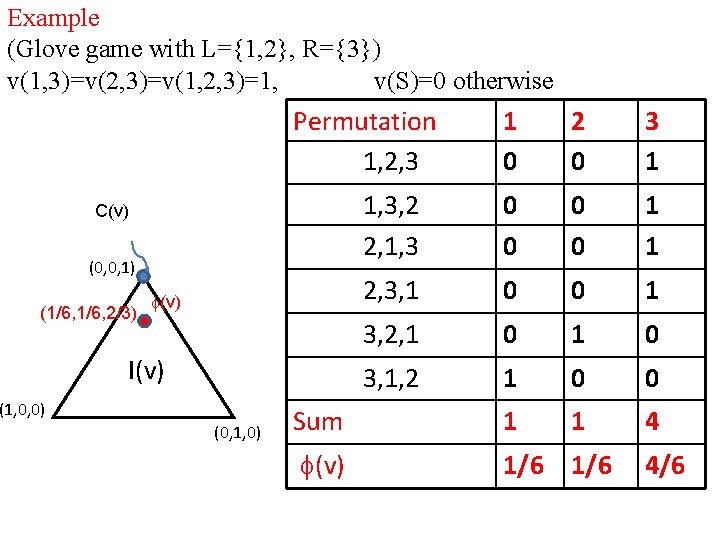

Example (Glove game with L={1, 2}, R={3}) v(1, 3)=v(2, 3)=v(1, 2, 3)=1, v(S)=0 otherwise Permutation 1, 2, 3 1 0 2 0 3 1 1, 3, 2 2, 1, 3 0 0 1 1 2, 3, 1 0 0 1 3, 2, 1 0 3, 1, 2 1 0 0 Sum 1 1 4 (v) 1/6 C(v) (0, 0, 1) (1/6, 2/3) (v) I(v) (1, 0, 0) (0, 1, 0) 4/6

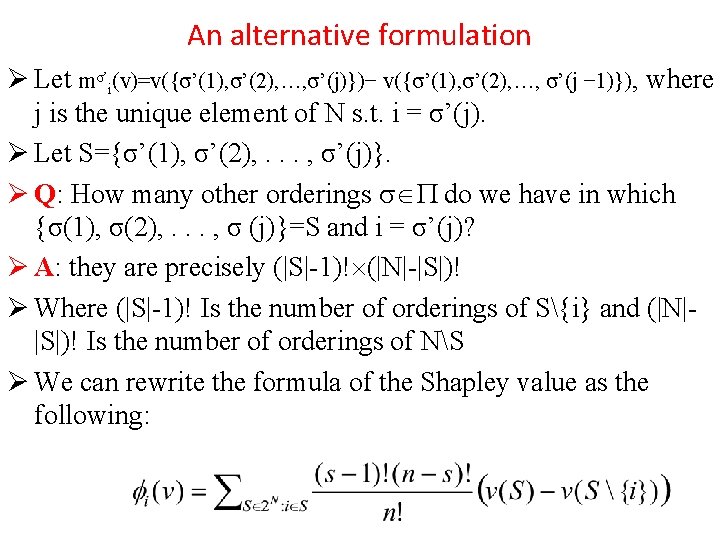

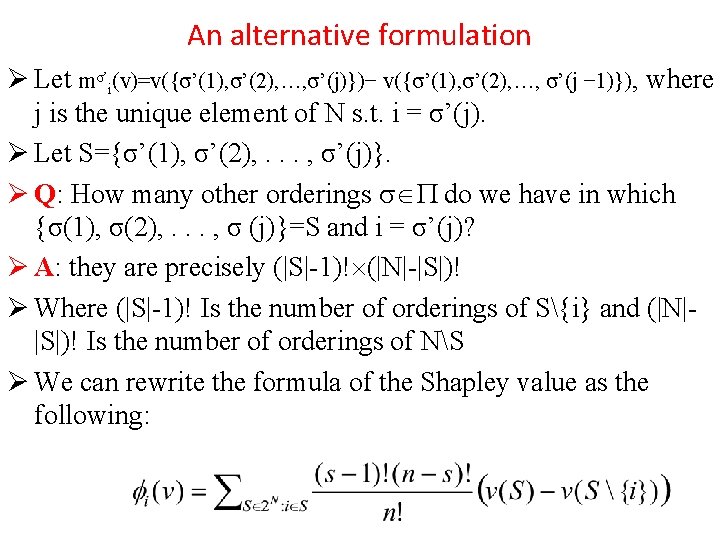

An alternative formulation Ø Let mσ’i(v)=v({σ’(1), σ’(2), …, σ’(j)})− v({σ’(1), σ’(2), …, σ’(j − 1)}), where j is the unique element of N s. t. i = σ’(j). Ø Let S={σ’(1), σ’(2), . . . , σ’(j)}. Ø Q: How many other orderings do we have in which {σ(1), σ(2), . . . , σ (j)}=S and i = σ’(j)? Ø A: they are precisely (|S|-1)! (|N|-|S|)! Ø Where (|S|-1)! Is the number of orderings of S{i} and (|N||S|)! Is the number of orderings of NS Ø We can rewrite the formula of the Shapley value as the following:

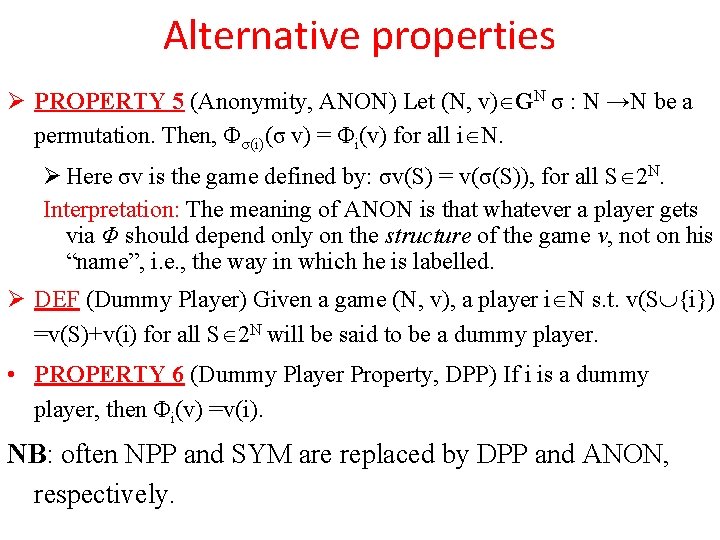

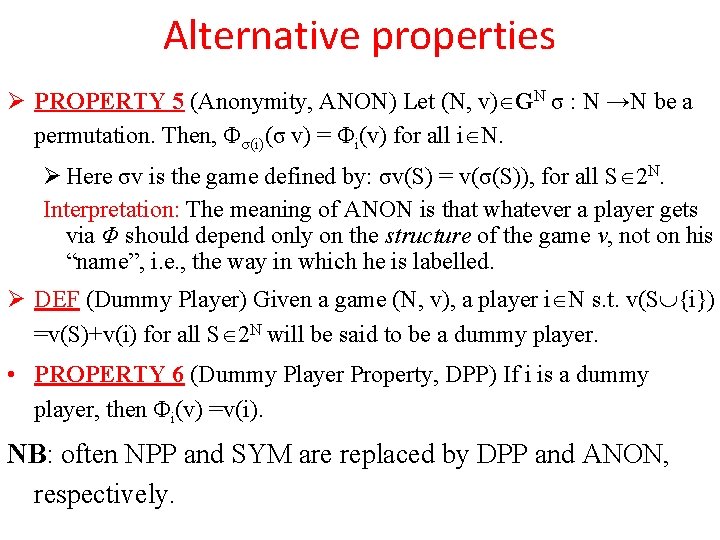

Alternative properties Ø PROPERTY 5 (Anonymity, ANON) Let (N, v) GN σ : N →N be a permutation. Then, Φσ(i)(σ v) = Φi(v) for all i N. Ø Here σv is the game defined by: σv(S) = v(σ(S)), for all S 2 N. Interpretation: The meaning of ANON is that whatever a player gets via Φ should depend only on the structure of the game v, not on his “name”, i. e. , the way in which he is labelled. Ø DEF (Dummy Player) Given a game (N, v), a player i N s. t. v(S {i}) =v(S)+v(i) for all S 2 N will be said to be a dummy player. • PROPERTY 6 (Dummy Player Property, DPP) If i is a dummy player, then Φi(v) =v(i). NB: often NPP and SYM are replaced by DPP and ANON, respectively.

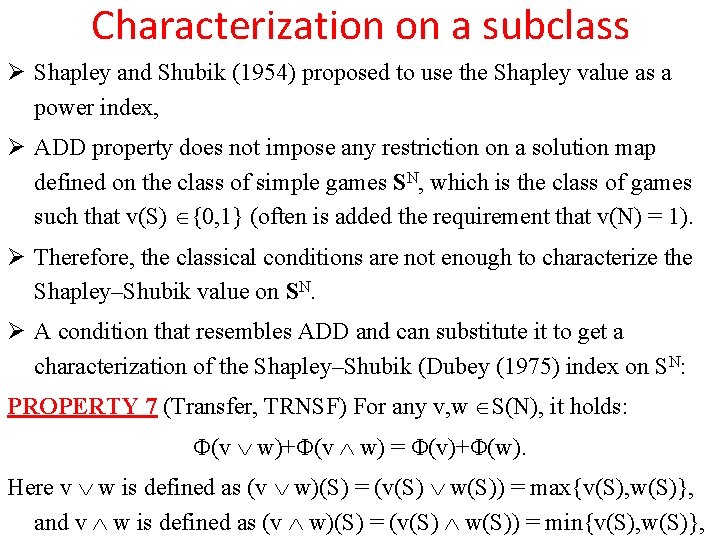

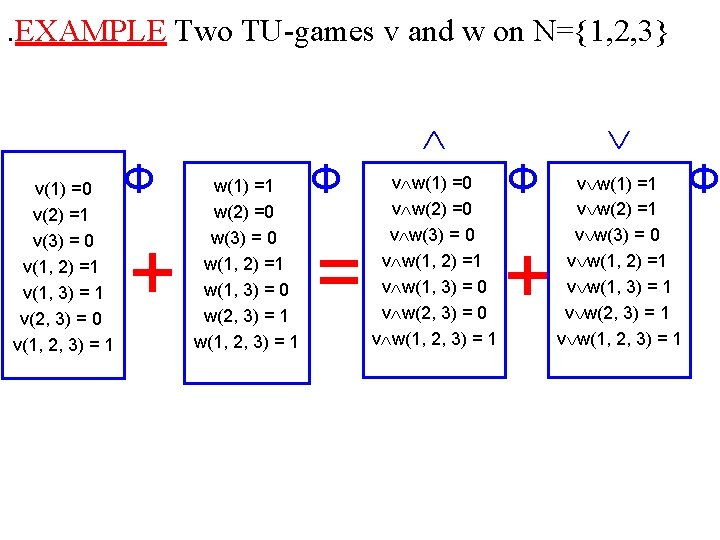

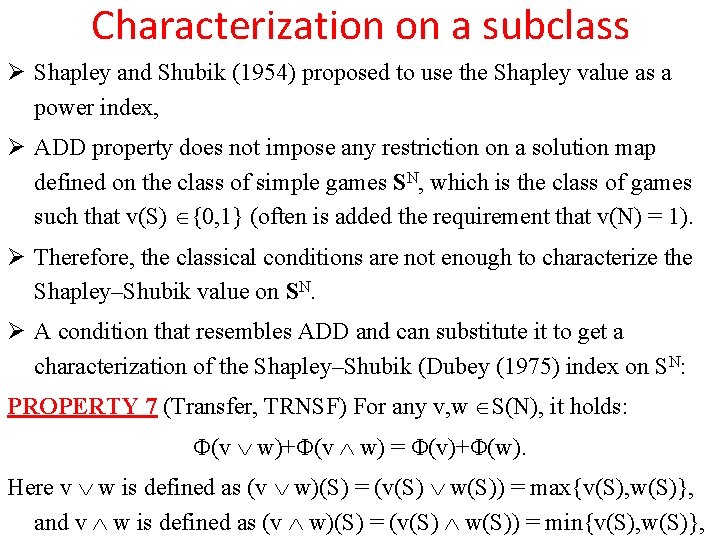

Characterization on a subclass Ø Shapley and Shubik (1954) proposed to use the Shapley value as a power index, Ø ADD property does not impose any restriction on a solution map defined on the class of simple games SN, which is the class of games such that v(S) {0, 1} (often is added the requirement that v(N) = 1). Ø Therefore, the classical conditions are not enough to characterize the Shapley–Shubik value on SN. Ø A condition that resembles ADD and can substitute it to get a characterization of the Shapley–Shubik (Dubey (1975) index on SN: PROPERTY 7 (Transfer, TRNSF) For any v, w S(N), it holds: Φ(v w)+Φ(v w) = Φ(v)+Φ(w). Here v w is defined as (v w)(S) = (v(S) w(S)) = max{v(S), w(S)}, and v w is defined as (v w)(S) = (v(S) w(S)) = min{v(S), w(S)},

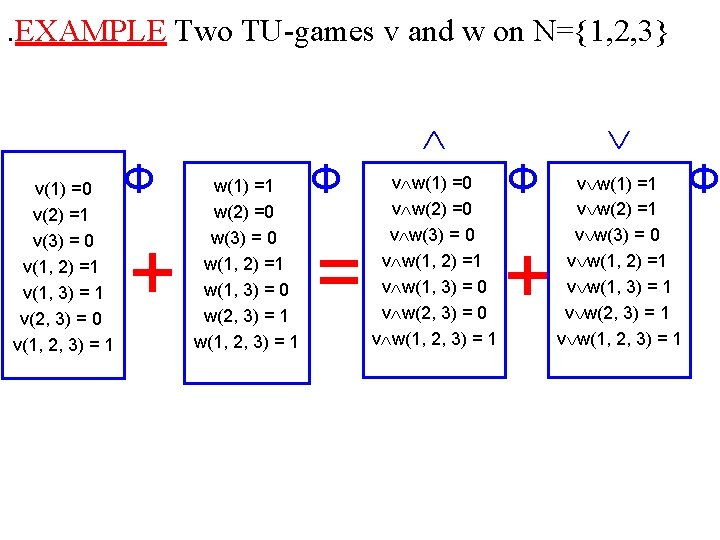

. EXAMPLE Two TU-games v and w on N={1, 2, 3} v(1) =0 v(2) =1 v(3) = 0 v(1, 2) =1 v(1, 3) = 1 v(2, 3) = 0 v(1, 2, 3) = 1 Φ + w(1) =1 w(2) =0 w(3) = 0 w(1, 2) =1 w(1, 3) = 0 w(2, 3) = 1 w(1, 2, 3) = 1 Φ = v w(1) =0 v w(2) =0 v w(3) = 0 v w(1, 2) =1 v w(1, 3) = 0 v w(2, 3) = 0 v w(1, 2, 3) = 1 Φ + v w(1) =1 v w(2) =1 v w(3) = 0 v w(1, 2) =1 v w(1, 3) = 1 v w(2, 3) = 1 v w(1, 2, 3) = 1 Φ

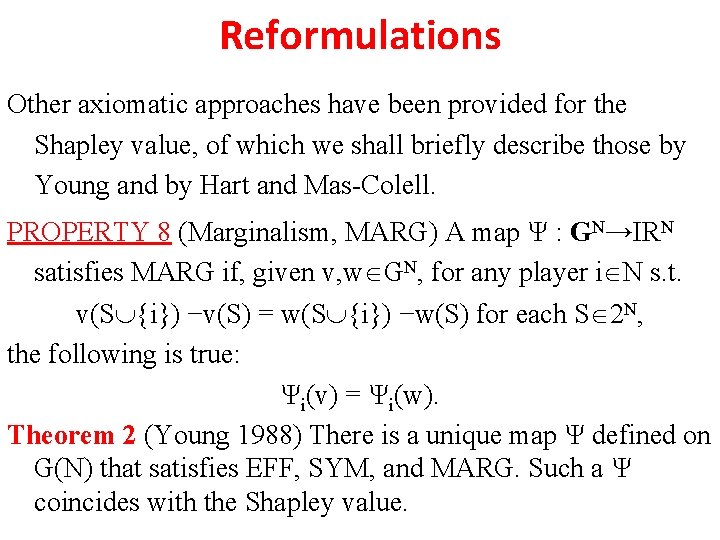

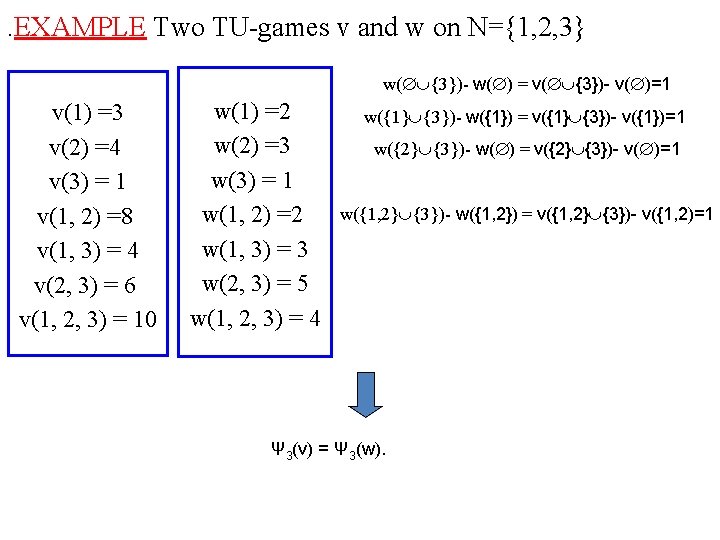

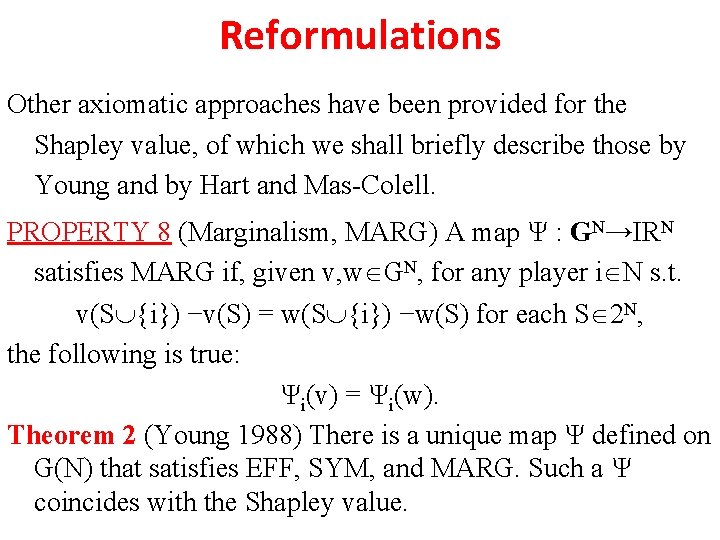

Reformulations Other axiomatic approaches have been provided for the Shapley value, of which we shall briefly describe those by Young and by Hart and Mas-Colell. PROPERTY 8 (Marginalism, MARG) A map Ψ : GN→IRN satisfies MARG if, given v, w GN, for any player i N s. t. v(S {i}) −v(S) = w(S {i}) −w(S) for each S 2 N, the following is true: Ψi(v) = Ψi(w). Theorem 2 (Young 1988) There is a unique map Ψ defined on G(N) that satisfies EFF, SYM, and MARG. Such a Ψ coincides with the Shapley value.

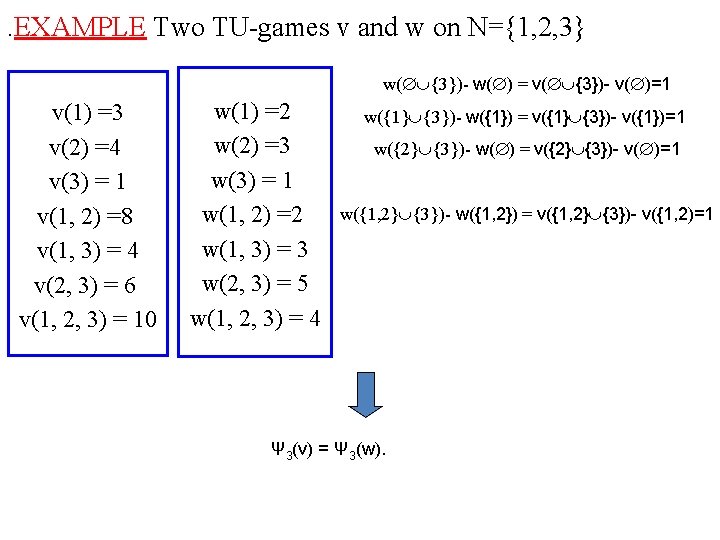

. EXAMPLE Two TU-games v and w on N={1, 2, 3} w( {3})- w( ) = v( {3})- v( )=1 v(1) =3 v(2) =4 v(3) = 1 v(1, 2) =8 v(1, 3) = 4 v(2, 3) = 6 v(1, 2, 3) = 10 w(1) =2 w(2) =3 w(3) = 1 w(1, 2) =2 w(1, 3) = 3 w(2, 3) = 5 w(1, 2, 3) = 4 w({1} {3})- w({1}) = v({1} {3})- v({1})=1 w({2} {3})- w( ) = v({2} {3})- v( )=1 w({1, 2} {3})- w({1, 2}) = v({1, 2} {3})- v({1, 2)=1 Ψ 3(v) = Ψ 3(w).

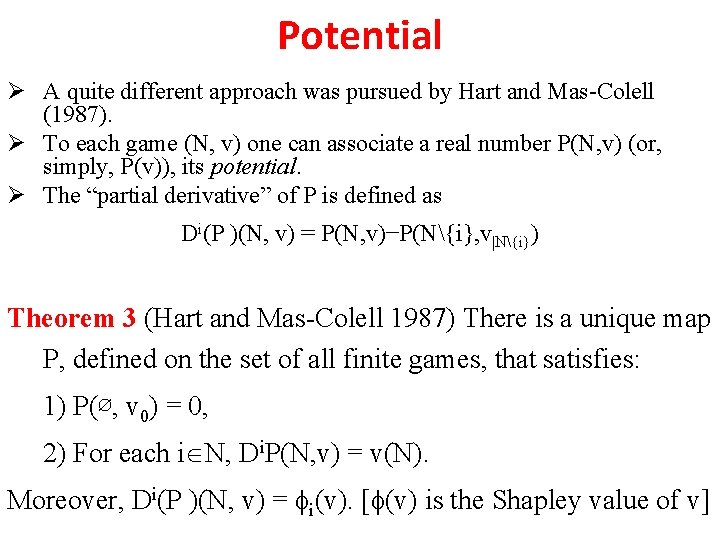

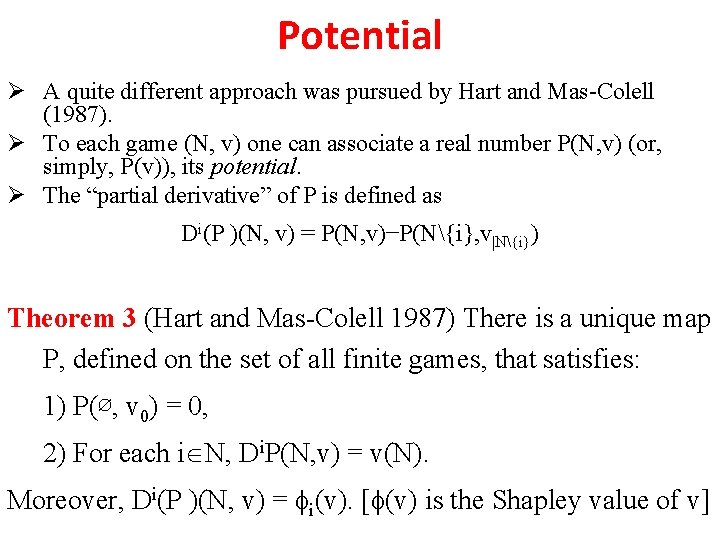

Potential Ø A quite different approach was pursued by Hart and Mas-Colell (1987). Ø To each game (N, v) one can associate a real number P(N, v) (or, simply, P(v)), its potential. Ø The “partial derivative” of P is defined as Di(P )(N, v) = P(N, v)−P(N{i}, v|N{i}) Theorem 3 (Hart and Mas-Colell 1987) There is a unique map P, defined on the set of all finite games, that satisfies: 1) P(∅, v 0) = 0, 2) For each i N, Di. P(N, v) = v(N). Moreover, Di(P )(N, v) = i(v). [ (v) is the Shapley value of v]

Ø there are formulas for the calculation of the potential. Ø For example, P(N, v)= S 2 N S/|S| (Harsanyi dividends) Example v(1) =3 v(2) =4 v(3) = 1 v(1, 2) =8 v(1, 3) = 4 v(2, 3) = 6 v(1, 2, 3) = 10 1(v) =3 2(v) =4 3(v) = 1 {1, 2}(v) =1 {1, 3}(v)=0 {2, 3}(v)=1 {1, 2, 3}(v)=0 1(v)=P({1, 2, 3}, v)-P({2, 3}, v|{2, 3})=9 -11/2=7/2 2(v)=P({1, 2, 3}, v)-P({1, 3}, v|{2, 3})=9 -4=5 3(v)=P({1, 2, 3}, v)-P({1, 2}, v|{2, 3})=9 -15/2=3/2 P({1, 2, 3}, v)=3+4+1+1/2=9 P({1, 2}, v)=3+4+1/2=15/2 P({1, 3}, v)=3+1=4 P({2, 3}, v)=4+1+1/2=11/2

équilibre de nash

équilibre de nash Théorie des jeux

Théorie des jeux Monstres verts

Monstres verts No decision snap decision responsible decision

No decision snap decision responsible decision Financial management process

Financial management process Théorie des deux facteurs de herzberg

Théorie des deux facteurs de herzberg Theorie des graphe

Theorie des graphe Limites de la théorie des attentes de vroom

Limites de la théorie des attentes de vroom La théorie des attentes de vroom

La théorie des attentes de vroom On me prend sans me toucher qui suis je

On me prend sans me toucher qui suis je Des des des

Des des des Exemple de remerciements dans un rapport de stage

Exemple de remerciements dans un rapport de stage Schéma fonctionnel d'une villosité intestinale

Schéma fonctionnel d'une villosité intestinale Dans le ciel d abraham

Dans le ciel d abraham Trajet des aliments dans le corps

Trajet des aliments dans le corps La famille des cochons ramenée dans l'étable analyse

La famille des cochons ramenée dans l'étable analyse Il ya des moments dans la vie

Il ya des moments dans la vie Les caractéristiques du début d'un conte

Les caractéristiques du début d'un conte Il y a des moments dans la vie

Il y a des moments dans la vie Il y a des moments dans la vie

Il y a des moments dans la vie Il y a des moments dans la vie

Il y a des moments dans la vie Futur simple jeu

Futur simple jeu Lutte cycle 2

Lutte cycle 2 Jeux traditionnels sportifs

Jeux traditionnels sportifs Jeux à essayer

Jeux à essayer Jeux symbolique montessori

Jeux symbolique montessori Bulgarie aux jeux olympiques d

Bulgarie aux jeux olympiques d Sous forme de jeu

Sous forme de jeu Construire un pont

Construire un pont Jeux en lige

Jeux en lige Fiche metier concepteur de jeux video

Fiche metier concepteur de jeux video Sexe.vidos

Sexe.vidos Jeux collectifs maternelleanimation

Jeux collectifs maternelleanimation Nnnn jeux

Nnnn jeux La marée fraternelle

La marée fraternelle Jeux vido

Jeux vido Anverten

Anverten Les rimes

Les rimes Decision table and decision tree examples

Decision table and decision tree examples Théorie néoclassique

Théorie néoclassique Taylor théorie

Taylor théorie Zelfcontroletheorie

Zelfcontroletheorie Polyvagal theorie

Polyvagal theorie Wachtrij theorie

Wachtrij theorie Ronald westra

Ronald westra Ronald westra

Ronald westra Sdt theorie

Sdt theorie Satisfaktoren

Satisfaktoren La théorie du grand homme leadership

La théorie du grand homme leadership Framing

Framing L'environnement selon callista roy

L'environnement selon callista roy