DAVID HUME Empiricism Imagination and Skepticism Hume and

- Slides: 18

DAVID HUME Empiricism, Imagination, and Skepticism

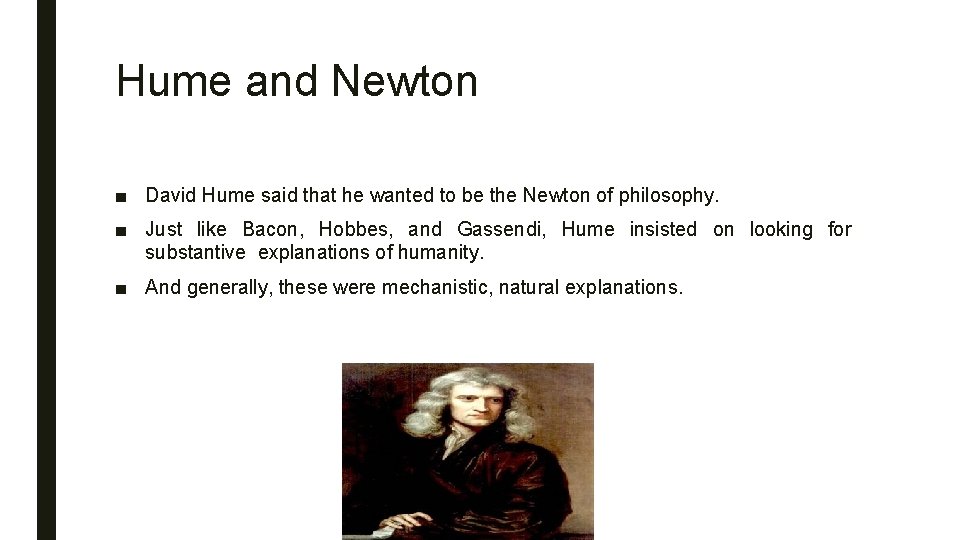

Hume and Newton ■ David Hume said that he wanted to be the Newton of philosophy. ■ Just like Bacon, Hobbes, and Gassendi, Hume insisted on looking for substantive explanations of humanity. ■ And generally, these were mechanistic, natural explanations.

Hume and Human Nature ■ David Hume, following Newton, aspires apply scientific method to human nature. ■ Hypotheses, he says, are worthless. They are not properly a science; but arise either from the fruitless efforts of human vanity, which would penetrate into subjects utterly inaccessible to the understanding, or from the craft of popular superstitions, which, being able to defend themselves on fair ground, raise these entangling brambles to cover any weakness. ■ Indeed, the mystical and arcane nature of hypotheses is itself an objection to them, making them mere superstition. ■ Scientific method, he says, is all we have.

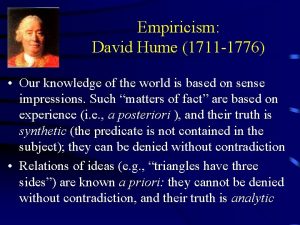

Empiricism ■ Hume is an empiricist. ■ In other words, he says, all knowledge comes from experience. ■ What does this mean? ■ Experience, Hume says, comes from the senses. ■ Hume, indeed, holds that the senses are primary, but can be indirect. ■ And, our experiences have components. ■ Still, empiricism is compatible with different epistemological views. ■ Hume, though, is a skeptic. But unlike many skeptics, he is happy being one, and does not try to escape it.

Beliefs and Causes ■ Hume argues that we cannot help but believe in external objects. ■ Yet we have no reasons to do so. – Nature has not left this to his choice, and has doubtless esteemed it an affair of too great importance to be trusted to our uncertain reasonings and speculations. ■ In other words, nature makes us believe, irrationally so. ■ As Hume says, the only question, then, is what causes us to believe in the existence of body.

Distinctions ■ Yet Hume proposes to keep two questions separate that are usually identified. ■ In other words, he distinguishes – What causes us to think that bodies are continuous? – What causes us to think that bodies are distinct, or independent of us? ■ Hume says that even if if these questions are related, it will help to separate them. ■ If we put these questions together, we can ask what causes us to believe in continuous and distinct objects?

Three Possibilities ■ As Hume says, there are only three possibilities. ■ In particular, he insists that there are only three faculties of the mind, each of which might make us believe. – Senses – Reason – Imagination ■ But as he says, the prospects are dim for each. ■ Skepticism might be inevitable.

Continuous? ■ The senses, Hume says, do not present anything continuously. ■ In particular, he insists that the content of any given perception lasts for a distinct period of time. – It is event these faculties are incapable of giving rise to the notion of continued existence of their objects, after they no longer appear to the senses. That is a contradiction in terms, and supposes that the senses continue to operate, even after they have ceased. ■ The contradiction, Hume says, is that since our perceptions are not continuous, they do not present objects as continuous. ■ Therefore, the senses cannot show objects are continuous, if they are.

Distinct? ■ Hume has a few arguments against the idea that the senses present objects to us as distinct. ■ In particular, the content of any perception is of some object but not of the distinctness of that object. ■ The content of perceptions is not of a double existence. – What the perception is about – And, that the perception or that the object is external to us. ■ Instead, Hume says, the content of our perceptions just concerns what they are about. ■ Therefore, the senses do not present objects to us as external.

Distinct Again ■ Hume also notes that the senses only would present objects to us as external if we could compare them. ■ In other words, we must compare objects and ourselves. – If the senses present our impressions as external to, and independent of, ourselves, both the objects and ourselves must be obvious to our senses, otherwise they could not be compared by these faculties. The difficulty is that how far we are the objects of our senses. ■ Yet as Hume says, this is a problem, since we do not really know what selves are, and we especially not by the sense. ■ Therefore, the senses, alone, cannot compare selves and objects.

The Senses Conclusion ■ Hume concludes this bit on the senses as follows – We may, therefore, conclude with certainty that the opinion of a continued distinct existence never arises from the senses. ■ Yet, since all we all believe this that objects are continuous and distinct, why do we

What about Reason? ■ Hume pauses briefly to discuss the possibility that reason might lead us to believe in continuous or distinct objects. ■ So with Locke and Berkeley, he distinguishes between – Primary qualities, such as figure, or density. – Secondary, like color – Internal affects, such as pain and pleasure ■ Hume insists that while some say that primary qualities exist but secondary ones do not. ■ But there is no real distinction here. ■ Therefore, all properties are internal, and imply nothing beyond themselves.

Vulgar Reason ■ But as Hume says, these are philosophers distinctions. ■ Philosophers may say that all we experience is in the mind, but that is now how the vulgar see things. – The vulgar confound perceptions and objects, and attribute a continued distinct existence to the very things they feel and see. This sentiment, then, is entirely unreasonable, and must proceed from some other faculty than the understanding. But who knows what they are. ■ In other words, if we directly perceive objects, reason has no role to play. ■ So, Hume says that reason does not, nor could it, give us any assurance about continued or distinct objects.

Imagination ■ Yet given all this, Hume says, if neither our senses or reason make us believe in continuous and distinct objects, the imagination does. ■ The imagination follows two qualities here – Coherence – Constancy ■ Hume spends the rest of the essay elaborating why the imagination responds to these qualities. ■ Yet also, why nature will make us ignore all this.

Imagination ■ What is the imagination? ■ Hume insists that the imagination is admirably facile. ■ Nothing is more admirable, than the readiness, with which the imagination suggests ideas, and presents them at the very instant they become necessary or useful. The fancy runs from one end of the universe to the other collecting those ideas, which belong to any subject. One might that the whole world of ideas was at once subjected to our view, and that we did nothing but pick out those that were proper for our purpose. ■ Yet there seem to be no limits here. ■ So we can easily imagine things in a way that seems to be rational, when it is clearly not.

Coherence and Continuation ■ Coherence, Hume says, is the fact that objects have a regular dependence on each other. ■ And this is is the foundation of much of our causal reasoning. ■ Without this interrelated coherence, Hume says, objects would lose the regularities in their operations. – There is scarce a moment of my life, wherein there is not a similar instance presented to me, and I have not the occasion to suppose the continued existence of bodies, in order to connect their past and present appearances, and given them union with one another ■ Yet as Hume says, our imagination exaggerates this coherence. ■ So, our imagination assumes continued existence, and so makes such coherence as complete as possible. ■ But this rational?

Constancy and Distinctness ■ Coherence, Hume says, is not enough. ■ The imagination helps us believe in the constancy of objects, or their ability to occur in a regular way. ■ Yet here, our imaginations are seduced – The imagination is seduced into that opinion by only by means of the resemblance of certain perceptions, Since we find that they are our only resembling impressions, which we have a propensity to suppose the same. The propensity to bestow an identity on our resembling perceptions produces the fiction of a continued existence of objects. ■ As Hume says, because our imaginations postulate continuing objects, we naturally infer that they are distinct too. ■ So our imaginations move from continued to distinct objects. ■ But none of this is rational.

Reason and Nature ■ Hume ends where he began, by contrasting reason and nature ■ Philosophers, he says, may say that all is perception, but also that our perceptions match continuing and distinct objects. ■ But this is an illusion. – Not being able to reconcile these two enemies, we endeavor to set ourselves at ease by as much as possible by successively granting to each whatever it demands and by feigning a double existence, where each may find something that has all the conditions it desires. ■ In other words, reason and nature are different. ■ And nature, Hume says, is obstinate, and has the upper hand When we are not vigilant, we revert back to believing in reality. ■ So in the end, skepticism is psychologically impossible.

Kelly inglis

Kelly inglis Organized skepticism definition

Organized skepticism definition Is constant and consistent the same

Is constant and consistent the same David hume nationality

David hume nationality Teoria da tabula rasa

Teoria da tabula rasa Conocimiento segun hume

Conocimiento segun hume Problem of evil hume

Problem of evil hume David hume definition of self

David hume definition of self Malcolm budd

Malcolm budd Hume aesthetics

Hume aesthetics David hume inconsistent triad

David hume inconsistent triad Hume y el escepticismo

Hume y el escepticismo Universidad nacional federico villarreal postgrado

Universidad nacional federico villarreal postgrado Kritik david hume terhadap merkantilisme

Kritik david hume terhadap merkantilisme David wechsler biography

David wechsler biography David hume tıp etiği ilkesi

David hume tıp etiği ilkesi David hume naturalism

David hume naturalism Empiricism and experimentalism

Empiricism and experimentalism Empiricism and the philosophy of mind

Empiricism and the philosophy of mind