Data representation Integers Modular arithmetic Real numbers Text

Data representation Integers Modular arithmetic Real numbers Text January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 1

Announcements • Pre-class quiz #5, due Sunday, Feb. 02, 19: 00 – Epp 4 e/5 e: Chapter 3. 1, 3. 3 • HW 2 out, due Tuesday, Feb. 04, 19: 00 January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 2

Signed integers • • A finite set of integers encoded with n bits should satisfy: – The number 0 will be represented – For every positive number, its negative counterpart will be represented – The integers should be consecutive • Multiple different methods exist for encoding signed integers, but the one most commonly used is two's complement January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 3

Two's complement • January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 4

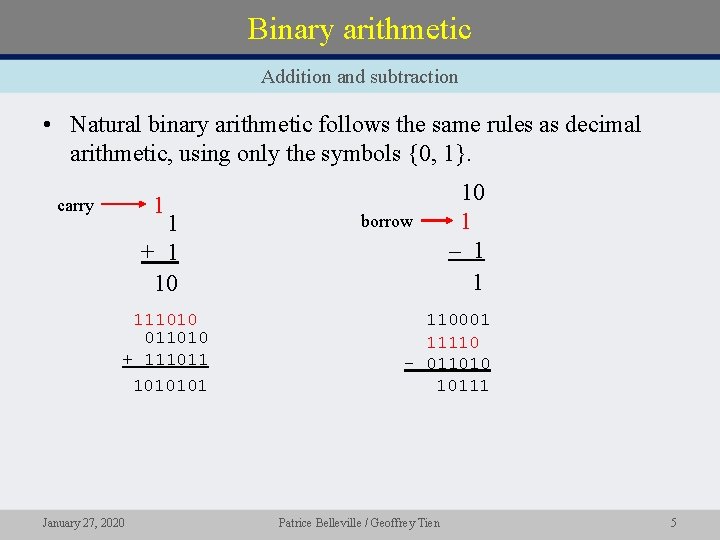

Binary arithmetic Addition and subtraction • Natural binary arithmetic follows the same rules as decimal arithmetic, using only the symbols {0, 1}. 1 carry 1 + 1 10 111010 011010 + 111011 1010101 January 27, 2020 borrow 10 1 – 1 1 110001 11110 - 011010 10111 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 5

Subtraction Back to two's complement • January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 6

Subtraction • January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 7

Overflow and underflow • The sum or difference of two n-bit integers may produce a result not within the range of values represented by n bits. – Must be able to detect whether a result is valid January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 8

Modular arithmetic January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 9

Modular arithmetic • January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 10

Modular arithmetic • January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 11

Modular arithmetic • January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 12

Modular arithmetic • January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 13

Modular arithmetic • January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 14

Modular arithmetic • January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 15

Data representation, continued Characters Real numbers Hexadecimal January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 16

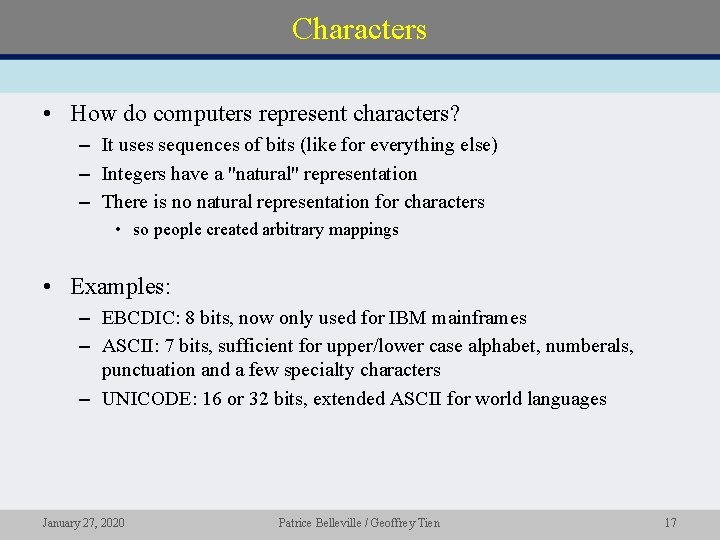

Characters • How do computers represent characters? – It uses sequences of bits (like for everything else) – Integers have a "natural" representation – There is no natural representation for characters • so people created arbitrary mappings • Examples: – EBCDIC: 8 bits, now only used for IBM mainframes – ASCII: 7 bits, sufficient for upper/lower case alphabet, numberals, punctuation and a few specialty characters – UNICODE: 16 or 32 bits, extended ASCII for world languages January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 17

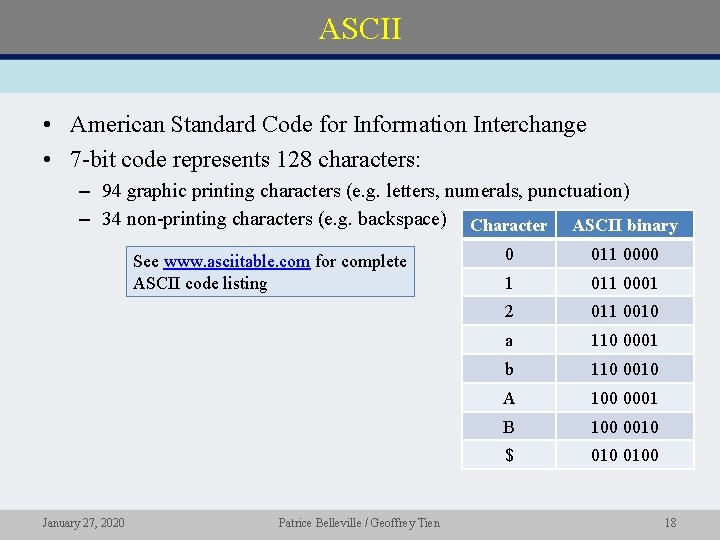

ASCII • American Standard Code for Information Interchange • 7 -bit code represents 128 characters: – 94 graphic printing characters (e. g. letters, numerals, punctuation) – 34 non-printing characters (e. g. backspace) Character ASCII binary See www. asciitable. com for complete ASCII code listing January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 0 011 0000 1 011 0001 2 011 0010 a 110 0001 b 110 0010 A 100 0001 B 100 0010 $ 0100 18

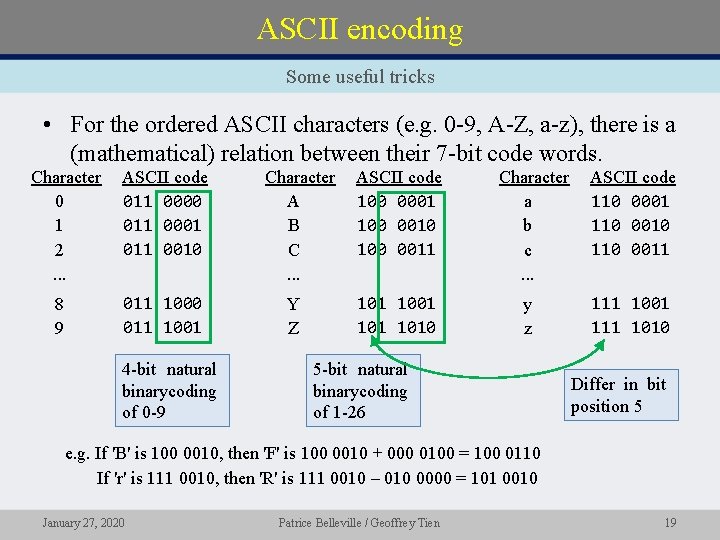

ASCII encoding Some useful tricks • For the ordered ASCII characters (e. g. 0 -9, A-Z, a-z), there is a (mathematical) relation between their 7 -bit code words. Character 0 1 2. . . 8 9 ASCII code 011 0000 011 0001 011 0010 011 1001 4 -bit natural binarycoding of 0 -9 Character A B C. . . Y Z ASCII code 100 0001 100 0010 100 0011 1001 1010 Character a b c. . . y z 5 -bit natural binarycoding of 1 -26 ASCII code 110 0001 110 0010 110 0011 1001 111 1010 Differ in bit position 5 e. g. If 'B' is 100 0010, then 'F' is 100 0010 + 000 0100 = 100 0110 If 'r' is 111 0010, then 'R' is 111 0010 – 010 0000 = 101 0010 January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 19

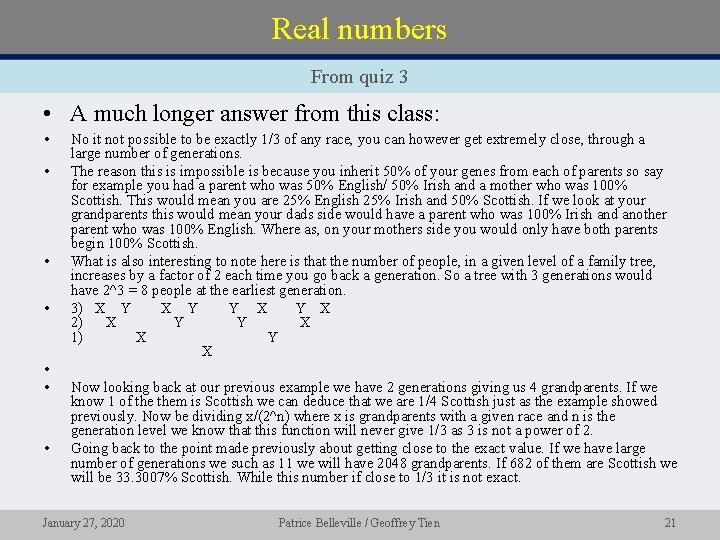

Real numbers From quiz 3 • Can someone be 1/3 Scottish? • Another response from our class: – To be Scottish what matters more than the percentage of Scottish DNA is how long you have lived in Scotland. You can be 1/4 Scot and still hate kilts and bagpipes. So, if you are 60 years old and you have lived in Scotland for 20 years then you are 1/3 Scottish. However, if you have lived in Scotland for the first 20 years of your life then maybe you are a little bit more Scottish because you are more impressionable when you are young. So maybe living 15 years after you are born could mean you are 1/3 Scottish. So, theoretically, you can be 1/3 Scottish with this method. January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 20

Real numbers From quiz 3 • A much longer answer from this class: • • No it not possible to be exactly 1/3 of any race, you can however get extremely close, through a large number of generations. The reason this is impossible is because you inherit 50% of your genes from each of parents so say for example you had a parent who was 50% English/ 50% Irish and a mother who was 100% Scottish. This would mean you are 25% English 25% Irish and 50% Scottish. If we look at your grandparents this would mean your dads side would have a parent who was 100% Irish and another parent who was 100% English. Where as, on your mothers side you would only have both parents begin 100% Scottish. What is also interesting to note here is that the number of people, in a given level of a family tree, increases by a factor of 2 each time you go back a generation. So a tree with 3 generations would have 2^3 = 8 people at the earliest generation. 3) X Y Y X 2) X Y Y X 1) X Y X Now looking back at our previous example we have 2 generations giving us 4 grandparents. If we know 1 of them is Scottish we can deduce that we are 1/4 Scottish just as the example showed previously. Now be dividing x/(2^n) where x is grandparents with a given race and n is the generation level we know that this function will never give 1/3 as 3 is not a power of 2. Going back to the point made previously about getting close to the exact value. If we have large number of generations we such as 11 we will have 2048 grandparents. If 682 of them are Scottish we will be 33. 3007% Scottish. While this number if close to 1/3 it is not exact. January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 21

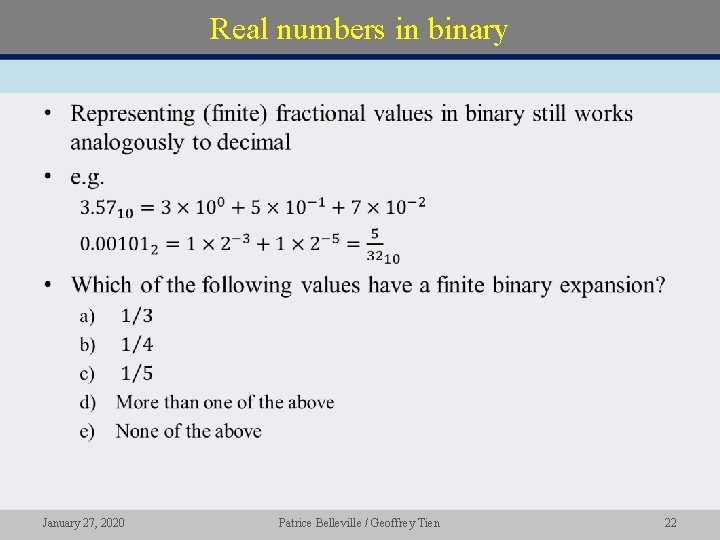

Real numbers in binary • January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 22

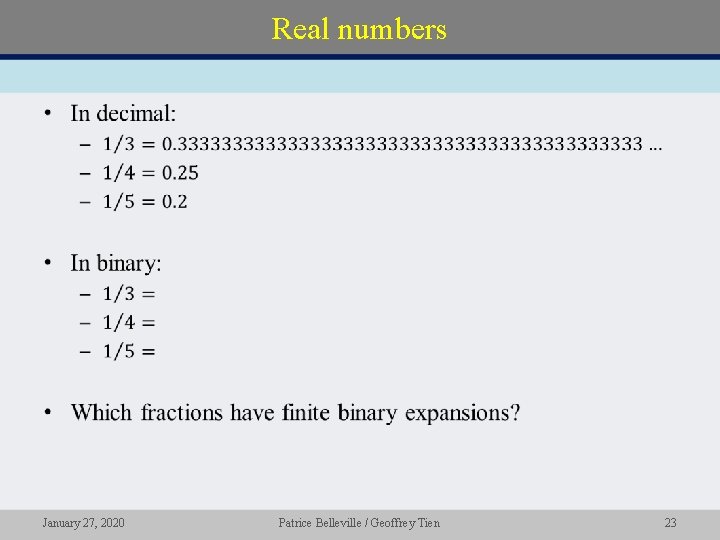

Real numbers • January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 23

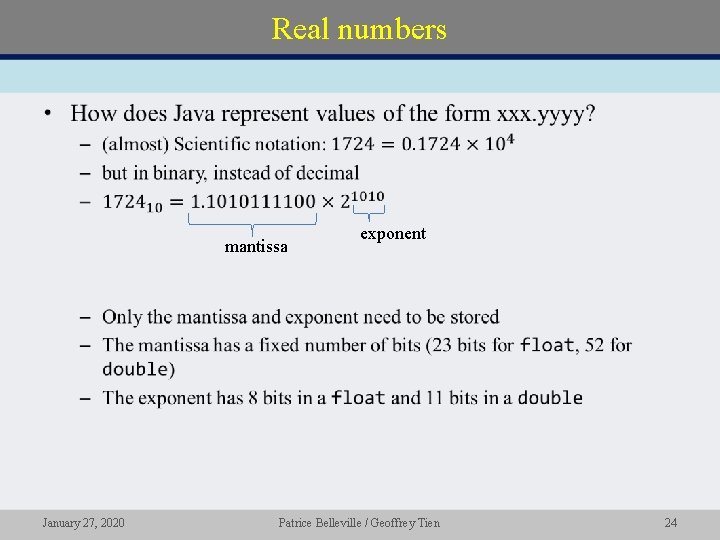

Real numbers • mantissa January 27, 2020 exponent Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 24

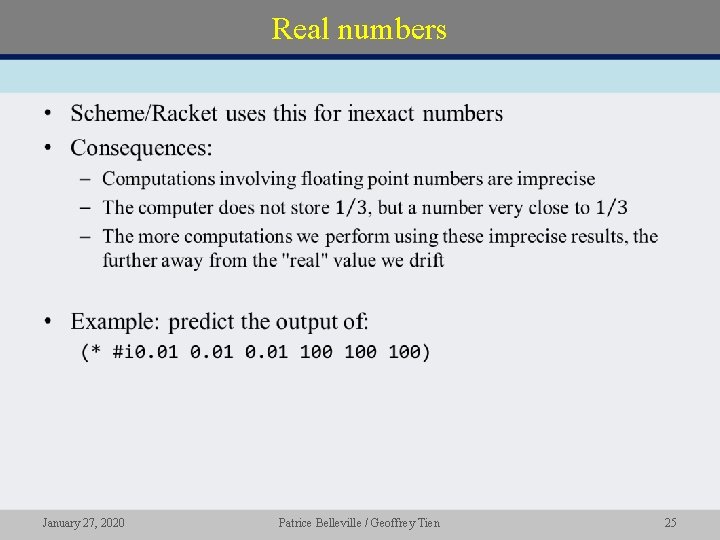

Real numbers • January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 25

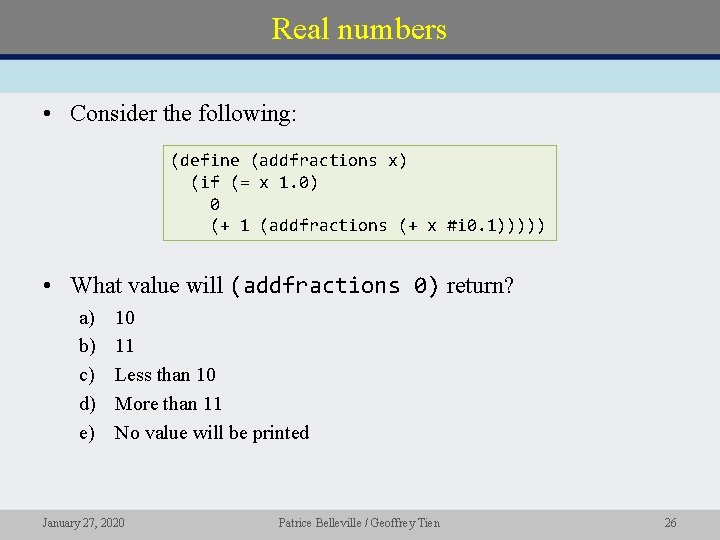

Real numbers • Consider the following: (define (addfractions x) (if (= x 1. 0) 0 (+ 1 (addfractions (+ x #i 0. 1))))) • What value will (addfractions 0) return? a) b) c) d) e) 10 11 Less than 10 More than 11 No value will be printed January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 26

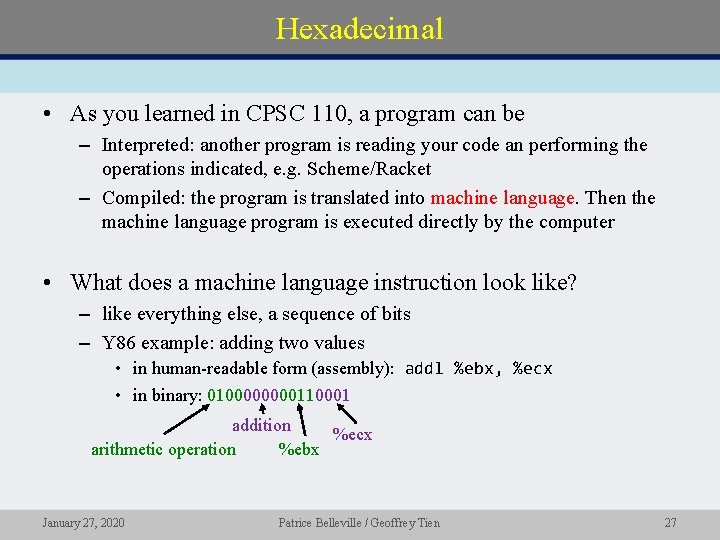

Hexadecimal • As you learned in CPSC 110, a program can be – Interpreted: another program is reading your code an performing the operations indicated, e. g. Scheme/Racket – Compiled: the program is translated into machine language. Then the machine language program is executed directly by the computer • What does a machine language instruction look like? – like everything else, a sequence of bits – Y 86 example: adding two values • in human-readable form (assembly): addl %ebx, %ecx • in binary: 010000110001 addition %ecx %ebx arithmetic operation January 27, 2020 Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 27

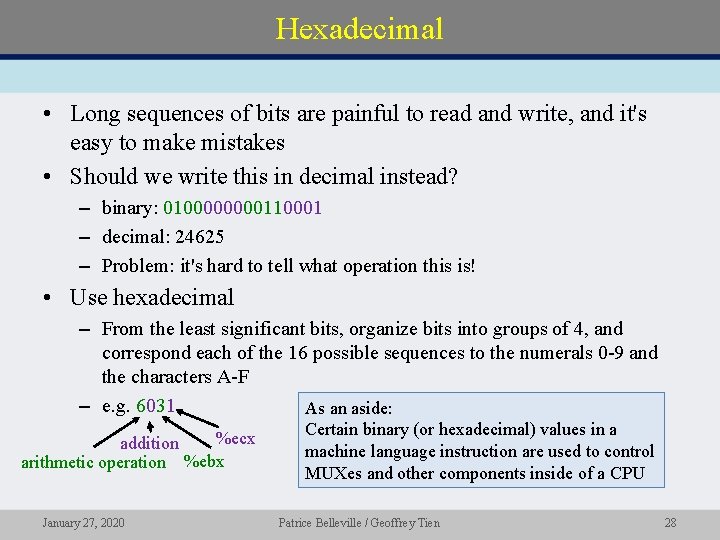

Hexadecimal • Long sequences of bits are painful to read and write, and it's easy to make mistakes • Should we write this in decimal instead? – binary: 010000110001 – decimal: 24625 – Problem: it's hard to tell what operation this is! • Use hexadecimal – From the least significant bits, organize bits into groups of 4, and correspond each of the 16 possible sequences to the numerals 0 -9 and the characters A-F – e. g. 6031 As an aside: %ecx addition arithmetic operation %ebx January 27, 2020 Certain binary (or hexadecimal) values in a machine language instruction are used to control MUXes and other components inside of a CPU Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 28

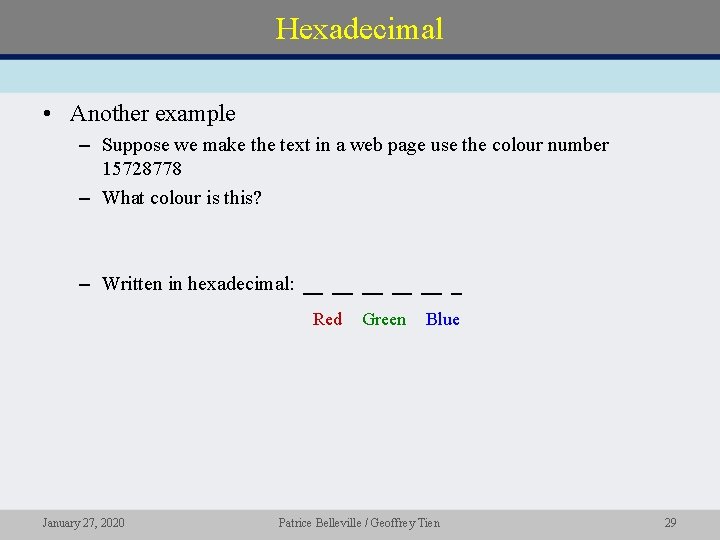

Hexadecimal • Another example – Suppose we make the text in a web page use the colour number 15728778 – What colour is this? – Written in hexadecimal: Red January 27, 2020 Green Blue Patrice Belleville / Geoffrey Tien 29

- Slides: 29