Data collection Questions to ask ways to ask

- Slides: 38

Data collection Questions to ask & ways to ask them 1

Questions to generate data

You should be familiar with these terms: • Primary data • Secondary data • Population • Sample • Census • Survey Questionnaires are commonly used to collect primary data from surveys. 3

Choosing the sample…. O Practicalities – e. g. access to participants, sample size; O Nature of sample – is it particularly important to include some groups? O Possibility of contaminated/distorted answers – ensure the sample is representative; O This aspect of your research says a lot about the care that you have taken over your work. 4

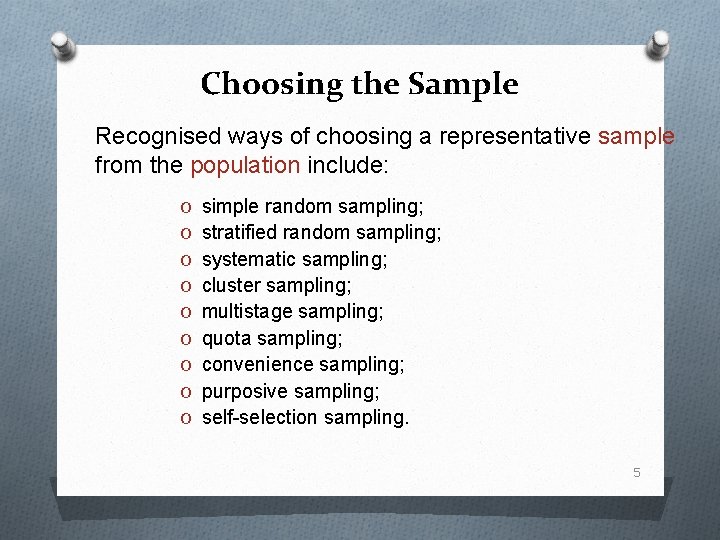

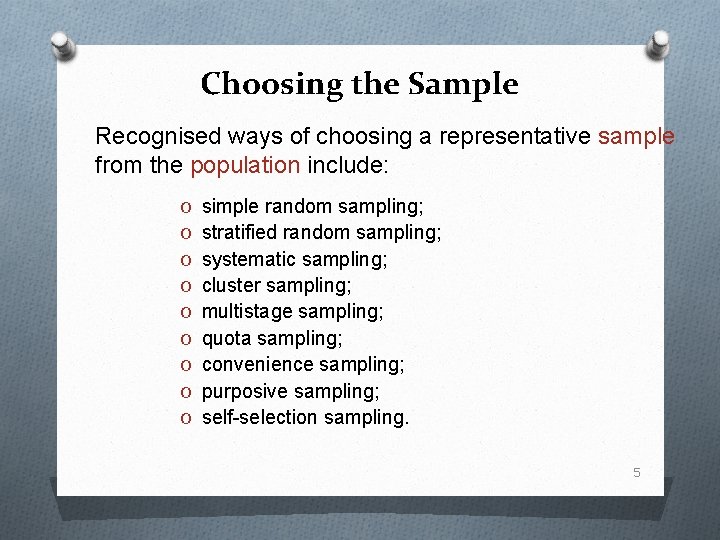

Choosing the Sample Recognised ways of choosing a representative sample from the population include: O simple random sampling; O stratified random sampling; O systematic sampling; O cluster sampling; O multistage sampling; O quota sampling; O convenience sampling; O purposive sampling; O self-selection sampling. 5

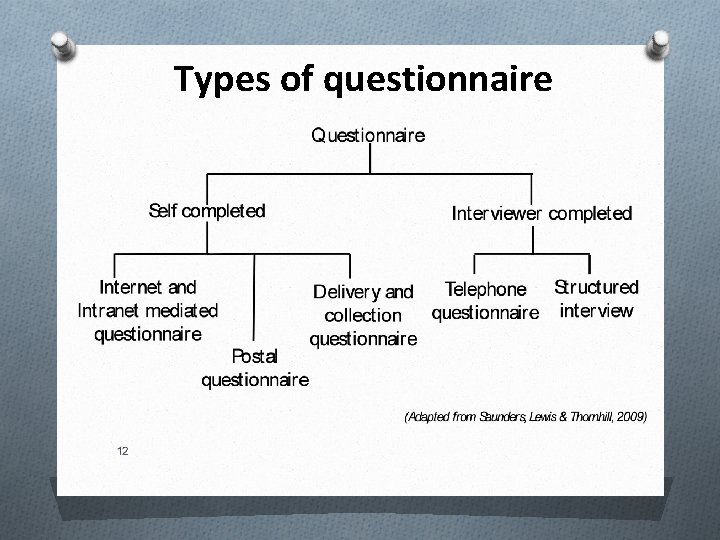

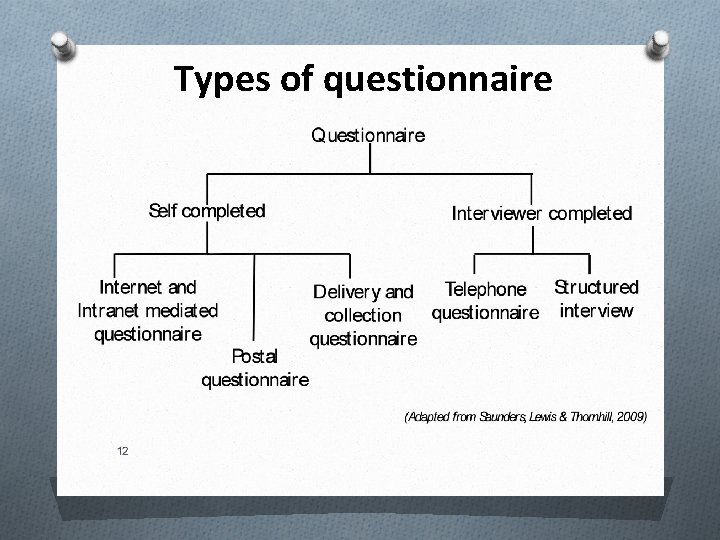

Types of questionnaire

Questionnaire Design Some general points to consider: • Effectiveness/limitations of the questions: what will you ask? ? • Use your theory to ground your questionnaire • Don’t underestimate the length of time it will take to devise a questionnaire – several iterations are needed • Consider the flow of questions, types of question, reliability of instructions, time required to complete • Linkage to proposed analysis must be considered early. 7

More design principles Also: • Design covering letter/introduction and coding plan (if needed) alongside the questionnaire • Use a pilot study to identify problems early • Think about the order of questions e. g. personal or open questions might be better placed at the end of the questionnaire • Support your main design decisions with reference to relevant research methods texts/journal articles. 8

Questioning Skills and Techniques 9

Questioning Skills and Techniques • • • Gathering information is a basic human activity – we use information to learn, to help us solve problems, to aid our decision making processes and to understand each other more clearly. Questioning is the key to gaining more information and without it interpersonal communications can fail. Questioning is fundamental to successful communication - we all ask and are asked questions when engaged in conversation. We find questions and answers fascinating and entertaining – politicians, reporters, celebrities and entrepreneurs are often successful based on their questioning skills – asking the right questions at the right time and also answering (or not) appropriately. Although questions are usually verbal in nature, they can also be non-verbal. Raising of the eyebrows could, for example, be asking, “Are you sure? ” facial expressions can ask all sorts of subtle questions at different times and in different contexts (note cultural differences). • Body Movements (Kinesics) • Posture • Eye Contact • Para-language (music of language) • Closeness or Personal Space (Proxemics) • Facial Expressions • Physiological Changes 10

Why Ask Questions? (1) Although the following list is not exhaustive it outlines the main reasons questions are asked in common situations. • To obtain information: The primary function of a question is to gain information – ‘ What time is it? ’ • To help maintain control of a conversation While you are asking questions you are in control of the conversation, assertive people are more likely to take control of conversations attempting to gain the information they need through questioning. • Express an interest in the other person Questioning allows us to find out more about the respondent, this can be useful when attempting to build rapport and show empathy or to simply get to know the other person better. • To clarify a point Questions are commonly used in communication to clarify something that the speaker has said. Questions used as clarification are essential in reducing misunderstanding and therefore more effective communication. 11

Why Ask Questions? (2) To explore the personality and or difficulties the other person may have Questions are used to explore the feelings, beliefs, opinions, ideas and attitudes of the person being questioned. They can also be used to better understand problems that another person maybe experiencing – like in the example of a doctor trying to diagnose a patient. • • To test knowledge Questions are used in all sorts of quiz, test and exam situations to ascertain the knowledge of the respondent e. g. ‘What is the capital of France? ’ • To encourage further thought Questions may be used to encourage people think about something more deeply. Questions can be worded in such a way as to get the person to think about a topic in a new way ‘Why do you think Paris is the capital of France? ” • In group situations Questioning in group situations can be very useful for a number of reasons, to include all members of the group, to encourage more discussion of a point, to keep attention by asking questions without advance warning. These examples can be easily related to a classroom of school children.

Types of questions (1) Closed Questions Closed questions invite a short focused answer- answers to closed questions can often (but not always) be either right or wrong. Closed questions are usually easy to answer as the choice of answer is limited - they can be effectively used early in conversations to encourage participation and can be very useful in fact-finding scenarios such as research. • Closed questions can simply require a ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ answer, for example: ‘Do you smoke? ’, ‘Did you feed the cat? ’, ‘Would you like a cup of tea? ’ • Closed questions can require that a choice is made from a list of possible options, for example: ‘Would you like beef, chicken or the vegetarian option? ’, ‘Did you travel by train or car today? ’ • Closed questions can be asked to identify a certain piece of information, again with a limited set of answers, for example: ‘What is your name? ’, ‘What time does the supermarket open? ’, ‘Where did you go to University? Open Questions By contrast, to closed questions, open questions allow for much longer responses and therefore potentially more creativity and information. There are lots of different types of open question; some are more closed than others! 13

Types of questions (2) Leading or ‘Loaded’ Questions A leading question, usually subtly, points the respondent’s answer in a certain direction. Asking an employee, ‘How are you getting on with the new finance system? ’ In a very subtle way it raises the prospect that maybe they are not finding the new system so good. ‘Tell me how you’re getting on with the new finance system’ is a less leading question – the question does not require any judgement to be made and therefore does not imply that there may be something wrong with the new system. Children are particularly susceptible to leading questions and are more likely to take the lead for an answer from an adult. • Something simple like, ‘Did you have a good day at school? ’ points the child towards thinking about good things that happened at school. • By asking, ‘How was school today? ’ you are not asking for any judgement about how good or bad the day has been and you are more likely to get a more balanced, accurate answer. • This can shape the rest of the conversation, the next question may be, ‘ What did you do at school? ’ - the answer to this may vary based on the first question you asked – good things or just things 14

Types of questions (3) Rhetorical Questions Rhetorical questions are often humorous and don’t require an answer. ‘If you set out to fail and then succeed have you failed or succeeded? ’ or ‘Do you live to eat or eat to live? ‘ Rhetorical questions are often used by speakers in presentations to get the audience to think – rhetorical questions are, by design, used to promote thought. Politicians, lecturers, priests and others may use rhetorical questions when addressing large audiences to help keep attention. ‘Who would not hope to stay healthy into old age? ’, is not a question that requires an answer, but our brains are programmed to think about it thus keeping us more engaged with the speaker. 15

Types of questions (4) Funnelling/Laddering of questions We can use clever questioning to essentially funnel the respondent’s answers – that is ask a series of questions that become more (or less) restrictive at each step, starting with open questions and ending with closed questions or vice-versa. For example: "Tell me about your most recent holiday. " "What did you see while you were there? " "Were there any good restaurants? " "Did you try some local delicacies? " "Did you try Clam Chowder? " The questions in this example become more restrictive, starting with open questions which allow for very broad answers, at each step the questions become more focused and the answers become more restrictive. • Funnelling can work the other way around, starting with closed questions and working up to more open questions. • For a counsellor or interrogator these funnelling techniques can be a very useful tactic to find out the maximum amount of information, by beginning with open questions and then working towards more closed questions. • In contrast, when meeting somebody new it is common to start by asking more closed questions and progressing to open questions as both parties relax. 16

How to Ask Questions (1) Being an effective communicator has a lot to do with how questions are asked. Once the purpose of the question has been established you should ask yourself a number of questions: • What type of question should be asked – Later • Is the question appropriate to the person/group? • Is this the right time to ask the question? • How do I expect the respondent will reply? When actually asking questions – especially in more formal settings some of the mechanics to take into account include: Structure It is usually a good idea to inform the respondent what you are researching and why before you start, provide some background information and reasoning behind your motive of asking questions. By doing this the respondent becomes more open to questions and why it is acceptable for you to be asking them. They also know and can accept the type of questions that are likely to come up, for example, ‘In order to help you with your insurance claim it will be necessary for me to ask you about your car, your health and the circumstances that led up to the accident”. In most cases the interaction between questioner and respondent will run more smoothly if there is some structure to the exchange. 17

How to Ask Questions (2) The use of silence • Using silence is a powerful way of delivering questions. • As with other interpersonal interactions pauses in speech can help to emphasise points and give all parties a few moments to gather their thoughts before continuing. • A pause of at least three seconds before a question can help to emphasise the importance of what is being asked. • A three second pause directly after a question can also be advantageous; it can prevent the questioner from immediately asking another question and indicates to the respondent that a response is required. • Pausing again after an initial response can encourage the respondent to continue with their answer in more detail. Pauses of less than three seconds have been proven to be less effective.

How to Ask Questions (3) Encouraging participation • In group situations leaders often want to involve as many people as possible in the discussion or debate. • This can be at least partially achieved by asking questions of individual members of the group. One way that the benefits of this technique can be maximised is to redirect a question from an active member of the group to one who is less active or less inclined to answer without a direct opportunity. • Care should be taken in such situations as some people find speaking in group situations very stressful and can easily be made to feel uncomfortable, embarrassed or awkward. Encourage but do not force quieter members of the group to participate.

Responses to questions (1) As there a myriad of questions and question types so there must also be a myriad of possible responses. Theorists have tried to define the types of responses that people may have to questions, the main and most important ones are: • A direct and honest response – this is what the questioner would usually want to achieve from asking their question. • A lie – the respondent may lie in response to a question. The questioner may be able to pick up on a lie based on plausibility of the answer but also on the non-verbal communication that was used immediately before, during and after the answer is given. • Out of context – The respondent may something that is totally unconnected or irrelevant to the question or attempt to change the topic. It may be appropriate to reword a question in these cases. • Partially Answering – People can often be selective about which questions or parts of questions they wish to answer. 20

Responses to questions (2) • Avoiding the answer – Politicians are especially well known for this trait. When asked a ‘difficult question’ which probably has an answer that would be negative to the politician or their political party, avoidance can be a useful tact. Answering a question with a question or trying to draw attention to some positive aspect of the topic are methods of avoidance. • Stalling – Although similar to avoiding answering a question, stalling can be used when more time is needed to formulate an acceptable answer. One way to do this is to answer the question with another question. • Distortion – People can give distorted answers to questions based on their perceptions of social norms, stereotypes and other forms of bias. Different from lying, respondents may not realise their answers are influenced by bias or they exaggerate in some way to come across as more ‘normal’ or successful. People often exaggerate about their salaries. • Refusal – The respondent may simply refuse to answer, either by remaining silent or by saying, ‘I am not answering’.

Interview techniques

Holding the floor (Gail Jefferson) Interrupting vs. Interjecting A debate is as much about performance and rhetoric (and snappy one-liners) as it is about meaningful dialogue. But our ideas about conversation inevitably shape how we perceive the debates. This means, for example, that what seems an interruption to one viewer might be merely an interjection to another. Conversation is an exchange of turns and having a turn means having a right to hold the floor until you have finished what you want to say. So interrupting is not a violation if it doesn’t steal the floor. (Deborah Tannen, "Would You Please Let Me Finish. . . " The New York Times, October 17, 2012) Sustaining the conversation If others are attempting to interrupt you can • Keep talking without pausing • Anticipate what they are going to say and answer them whilst maintaining your flow • Indicate you are about to finish (but carry on) • Subtlety change the subject • Raise your voice and pitch (and establish eye contact) to indicate that you are coming to the end (without actually doing so).

Controlling conversations These are three techniques for controlling the conversation or interview so that you are sure to get the main point or points that you want remembered across. Bridge. This technique will allow you to move from an area in the conversation that you don’t want to discuss and get the conversation back to your message. If the interviewer says, for example, “wouldn’t it help the museum if you began to charge user fees? ” You can get the conversation back to your message by responding, “I think the real question is, how important is the museum to the well being of this community? ” You don’t have to come up with this off the top of your head – you should be prepared with this bridging statement prior to your interview. Hook. This is a technique that gets the interviewer to follow-up on your first point allowing you to get a second point in. For example, you can say, “There are two very important considerations that must be taken into account before we support this proposed policy. The first is. . . “ then expand on that point. The interview will seem incomplete when aired if the reporter doesn’t follow-up with, “and the second point? ” This is a good way to ensure that both your points get air time. Flag. This technique is the easiest and most people use it unconsciously all the time. Flagging alerts your listeners to what you consider most important. It’s a good way to emphasize the key point or points you want the audience to remember. Flagging is simply giving your audience a verbal clue about what is important: “The most important thing to remember is. . . “ or “If you remember nothing else, please remember these two points. . . ”

Avoiding Questions Question avoidance is a key strategy on topics a) that you don’t want to talk about b) when you want to get other points over Avoidance can be done through a change of topic or plain refusal. The following typical phrases illustrate the point • • • I am not sure that is really the question to be asked, what is really important is… What people really want to know is… Before I answer that question it is very important that we discuss … I’m not going to answer that question You will have to ask them that… Gordon Brown answers his own questions, never the interviewer's, and is utterly shameless. He will say what he wants to say and that's it. And he'll say it fifty times in one interview without any embarrassment at all. I've never met anyone quite like him in that respect. http: //maxatkinson. blogspot. co. uk/2009/05/prime-minister-who-openly-refused-to. html

Sound-bites & getting your message across A lift speech: A lift speech gets its name from an imaginary scenario in which you find yourself in a lift with someone you would like to impress with information about your group. The scenario dictates that you only have 30 seconds to "sell" your idea and get your message through to the person in the lift. Sound Bites: The concept of a sound bite is similar to a lift speech. A sound bite is the verbal equivalent of a newspaper "quote". It is a short, catchy snippet of speech, usually between 5 and 10 seconds, which television and radio use in their reports to summarise your opinion or make a point. Sound bites are not a new thing e. g. "The only thing we have to fear is fear itself“ the most famous phrase in Franklin D. Roosevelt's first inaugural address—were examples of eloquent speakers unselfconsciously and simply trying in words to capture the essence of the thought they wished to communicate. In journalism, sound bites are used to summarize the position of the speaker, as well as to increase the interest of the reader or viewer in the piece. In both print and broadcast journalism, sound bites are conventionally juxtaposed and interspersed with commentary from the journalist to create a news story. A balanced news report is expected to contain sound bites representing both sides of the debate. This technique, however, can lead to biased reporting when a sound bite is selected for sensationalism, or is used to promote the point of view of one individual or group over another

Tips for a News Interview Tip 1: Talk in sound bites. Although the camera may film you for 15 minutes, you will only be on the air for about 10 to 20 seconds (unless it’s a documentary), so use brief, concise statements. Tip 2: Use memorable words. State your message clearly and powerfully. Tip 3: Look your best. Take advantage of television makeup artists, if offered. Consider having your hair professionally cut or styled. Don’t wear multiple patterns (e. g. , stripes or checks) or colors because it causes vibrating lines on the camera. Men should wear neutralcolor suits with solid-color shirts, and ties with simple patterns. Women should wear business like dresses, with or without jackets, or suits. Avoid large earrings or jewelry that could be distracting. Don’t wear extremely short skirts. Tip 4: Concentrate on the interviewer, not the camera. Maintain eye contact with the interviewer and smile. Tip 5: Talk to the floor manager and camera crew prior to the show. One of their responsibilities is to help you do a great job by making you comfortable. Tip 6: Watch your body language. Stand or sit straight. Don’t fold your arms, and appear open and in control. Don’t let your shoulder blades touch the back of your chair. Tip 7: Television talk shows. Don't be afraid to engage in discussions when there are other people on the show with you. This is essential to communicating your message. Tip 8: Stand-up interviews. Take command of your space by standing with one foot slightly ahead of the other, toward the interviewer

Discourse Analysis

Conversation analysis (Gail Jefferson) So basic is the ‘one speaker at a time’ rule that we get uneasy when we find ourselves in situations where it is being violated, whether by ourselves or by someone else. As a result, one or other of the speakers will always eventually give way, thereby enabling a return to orderly turn-taking where ‘one speaker speaks at a time’. To win, all you have to do is to carry on speaking and ignore anyone else’s attempts to ‘get a word in edgeways’ (continuo). It’s no use just trying to get the odd word or two in - e. g. ‘but- but' - and expect that the other person will give way (staccato ), because, so long as you proceed no further than that, they won’t. Next time you find yourself in a situation where you’re competing to get a chance to speak, remember that the staccato technique is unlikely to succeed, but that you're almost certain to win if you’re prepared to use the continuo technique. But remember too that the only thing you'll win is the space to say whatever it is you want to say and that such victories come at a price - namely that people will not only notice what you're doing but will also use such behaviour as a basis for drawing negative conclusions about you and the kind of person you are http: //maxatkinson. blogspot. co. uk

Argument "Argument, in its most basic form, can be described as a claim (the arguer's position on a controversial issue) which is supported by reasons and evidence to make the claim convincing to an audience. All of the forms of argument described below include these components. • Debate, with participants on both sides trying to win. • Courtroom argument, with lawyers pleading before a judge and jury. • Dialectic, with people taking opposing views and finally resolving the conflict. • Single-perspective argument, with one person arguing to convince a mass audience. • One-on-one everyday argument, with one person trying to convince another. • Academic inquiry, with one or more people examining a complicated issue. • Negotiation, with two or more people working to reach consensus. • Internal argument, or working to convince yourself. (Nancy C. Wood, Perspectives on Argument. Pearson, 2004) Monty Python Argument Clinic (approx 5 mins) http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=k. QFKt. I 6 gn 9 Y

Rhetoric Definitions: Is the art of ruling the minds of men (Plato) Refers but to 'the use of language in such a way as to produce a desired impression upon the hearer or reader (Kenneth Burke, Counter-Statement, 1952). Aristotle organized the art of rhetoric into three parts: 1. Ethos -- Ethos is all about how an audience views a speaker. Are they 2. 3. credible? Do they have authority or expertise on this topic? Are they impartial -- or do they have a stake in the outcome? Pathos -- Pathos is the use of emotion and passion in rhetoric and writing. Your arguments can't be made entirely up of emotional appeals -- but they can't be cold recitations of statistics, either Logos -- Logos is how arrange and structure your arguments to build a case. This is a difficult and interesting subject, and it can make all the difference in whether you persuade an audience or not

Oratory • It has become commonplace today to lament the loss of the art of eloquence. • In our electronic age, it is said, the conditions which once allowed oratory to flourish have all but disappeared. • Speech communities have been fractured; the ambitions of political oratory have been trivialised, its passions and arguments reduced to mere sound bites; and the sites of public debate have been privatised and rededicated to the gods of a consumer culture. • Striking examples of public speech, such as the Earl Spencer's eulogy on Princess Diana, are greeted with surprise as the last gasps of a dying art rather than as proof of the vitality of the tradition

Oratory and the rule of three The rule of three is a writing principle that suggests that things that come in threes are inherently funnier, more satisfying, or more effective than other numbers of things. The reader or audience of this form of text is also more likely to consume information if it is written in groups of threes Max Atkinson, in his book on oratory entitled Our Masters' Voices gives examples of how public speakers use three-part phrases to generate what he calls 'claptraps', evoking anticipatory audience applause. • Martin Luther King Jr. , in his speech "Non-Violence and Racial Justice" contained a binary opposition made up of the rule of three: "insult, injustice and exploitation, " followed a few lines later by "justice, goodwill and brotherhood. " • Conversely, segregationist Alabama governor George Wallace said: "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever" during his 1963 inaugural address. • The appeal of the three-fold pattern is illustrated by the transformation of Winston Churchill's reference to "blood, toil, tears and sweat"

Oratory & the importance of transitions "To move from one to another of the three major parts of a speech (i. e. , introduction, body, and conclusion), you can signal your audience with statements that summarize what you've said in one part and point the way to the next. For example, here is an internal summary and a transition between the body of a speech and the conclusion: "I've now explained in some detail why we need stronger educational and health programs for new immigrants. Let me close by reminding you of what's at stake” If the introduction, body, and conclusion are the bones of a speech, the transitions are the sinews that hold the bones together. Without them, a speech may seem more like a laundry list of unconnected ideas than like a coherent whole. “ (Julia T. Wood, Communication in Our Lives, 6 th ed. Wadsworth, 2012)

Great Oration In 1957, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which organized civil rights activities throughout the United States. In August 1963, he led the great march on Washington, where he delivered this memorable speech in front of 250, 000 people gathered by the Lincoln Memorial and millions more who watched on television Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929 -1968) “Let us not wallow in the valley of despair, I say to you today, my friends. And so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal. " I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice. I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today! I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of "interposition" and "nullification"--one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today! I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight; and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together. This is our hope, and this is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith, we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day”…. . etc.

I Have a Dream, by Martin Luther King (1) Martin Luther King Jr’s “I have a dream” speech put the civil rights movement into the hearts and minds of Americans and beyond. It contributed to him being named Man of the Year by Time magazine in 1963 and to his Nobel Peace Prize the following year. (Sarah Lloyd- Hughes; Ginger Training and Coaching). 1) Rock solid, unshakeable confidence You can see from Martin Luther King’s body language that he was calm and grounded as he delivered his speech. Although you can’t see his feet as he’s speaking, I’d imagine him to be heavily planted to the ground, with a solid posture that says “Here I am. I’m not budging. Now, you come to me. ” Self-belief from a beyond-personal source gives this sort of power – and you can see the impact. 2) The Voice It would always take a commanding voice to inspire thousands and Martin Luther King’s booming voice was well practiced in his capacity as a Baptist preacher. His cadence, his pacing and his preacher-like drama bring real passion to the speech. Martin Luther King used powerful, evocative language to draw emotional connection to his audience, such as: • “Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. ” • “This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. ” • “We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities

I Have a Dream, by Martin Luther King (2) 3) Rhythm & Repetition The intensity of King’s speech is built through bold statements and rhythmic repetition. Each repetition builds on the one before and is reinforced by Martin Luther King’s ever increasing passion. • “We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. • “Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina…” • “Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia. Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee. Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring. ” • As the speech comes to a close the pace of Martin Luther King’s repetition increases, helping to build to a crescendo.

I Have a Dream, by Martin Luther King (3) 4) Ditching the Script If that wasn’t dramatic enough, Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech was never meant to even include its most famous sequence and climax. King put aside his script ten minutes into the speech. Few would dare risk it at such a moment, but King was said to have responded to the cry of Gospel singer Mahalia Jackson “Tell ‘em about the dream, Martin!” and ad-libbed what came next. This is what gave “I have a dream” its raw power and edge – King was living the words that he spoke. 5) With his people So often it is the speaker who is flexible and vulnerable enough to connect with their audience who has the most powerful impact. “I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations, ” he begins. King goes on to talk to his audience and their personal situations directly. “Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. ” King is with the people, fully connecting to them with his eyes and delivering a powerful rhythm in his speaking. Martin Luther King’s script writer, Clarence B Jones reflected, “It was like he had an out-of-body experience. ”