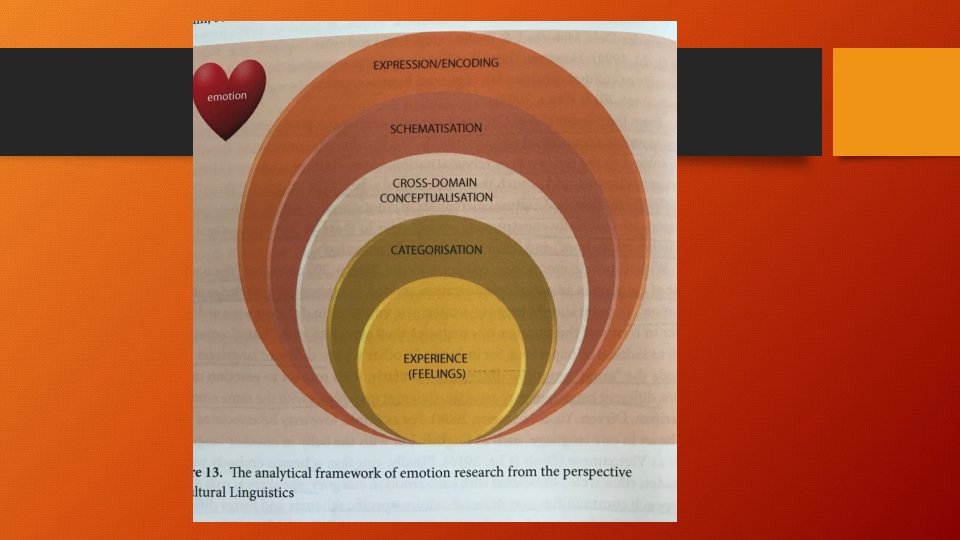

Cultural Linguistics and Emotion Research From the perspective

- Slides: 23

Cultural Linguistics and Emotion Research

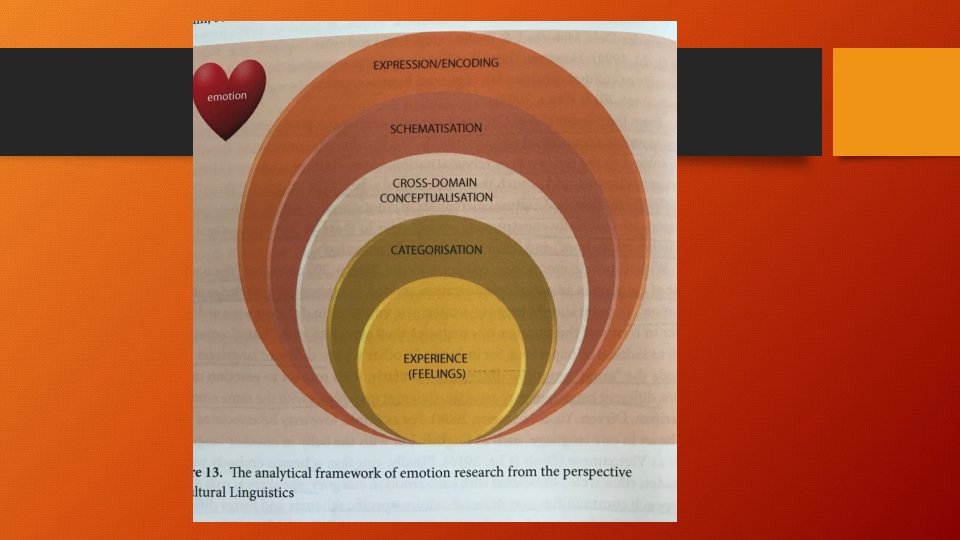

From the perspective of cultural linguistics, emotions have a physical dimension as well as a conceptual one

Different languages may encode the „same” emotions differently Different languages may associate different metaphors with the same emotion

Speakers across different speech communities may draw on culture-specific schemas and foster different values or attitudes towards similar emotion categories

Different cultural attitudes toward emotions exert a profound influence on the dynamics of everyday discourse…different cultures may vary in terms of the attitudes they foster in their members towards the expression or encoding of emotions.

Cultural conceptualisations relating to Persian qam --captures a whole range of emotional states that one goes through --overlaps with at least five categories in Western varieties of English: pain, sorrow, grief, sadness, and worry

Cultural metaphors where qam is used in expressions that envision absence of a beloved as physical pain • Pain-of absence you oh beloved devastated-me did (My beloved! Your absence has devastated me!) • Sadness-stricken to look you-do anything happened (You look sad! What has happened? )

It is considered a virtue to listen to and share others’ qam. The person who does this is referred to as a qam eater (the underlying cultural metaphor here is qam as an edible entity. )

Qam used in cross-domain conceptualisations: qam corner-of heart-mine nest has done qam has built a nest in the corner of my heart. (del as the seat of emotions + qam as a bird/animal that occupies a nest in it)

The emotional experience of qam has an important symbolic place in the religious and everyday life of many Iranians…discharging one’s qam can be a sign of piety, reflecting the concept of dysphoria

„Dysphoria” is hardly the simple lack of happiness or pleasure of the individual to be overcome by therapy or medical treatment…it is the central emotion of religious ritual, an important element of the definition of selfhood, a key quality of a developed and profound understanding of the social order

Qam is not viewed as an entirely negative emotion…a typical image associated with qam is that of a mother worrying about her children

Intercultural misunderstandings may occur either because one language does not have a specific word for that particular emotion, or because an emotion is understood as negative in one culture while it is positive in another

Two examples from Hungarian: szeretet & szerelem can both be expressed only with „love” in English Ancient Greek was even richer, with four different kinds of love: philia, eros, agape & storge

In English „incentive” is only understood in a positive sense, i. e. something that prompts you or encourages you to do something, while in Hungarian it can be translated in a negative sense as well „ingerlő”

An example from Aboriginal English where a word that is normally emotionally neutral acquires an emotional and spiritual dimension: Rain For Aboriginals, rain is often used to conceptualise the emotions of the Ancestors: their sadness, their anger

„When it’s death or funeral times…then this cloud comes and it’s the rain it’s called the midjal, it rain, it’s a sad rain, it’s crying rain…the old fallas crying for, um, not crying for the falla who’s gone cause they’re with them, they’re crying for the fallas that’re there, they’re cryin’ sad for watchin’ all the people mob cryin’, you know, and it’s a soft rain, a different rain. ”

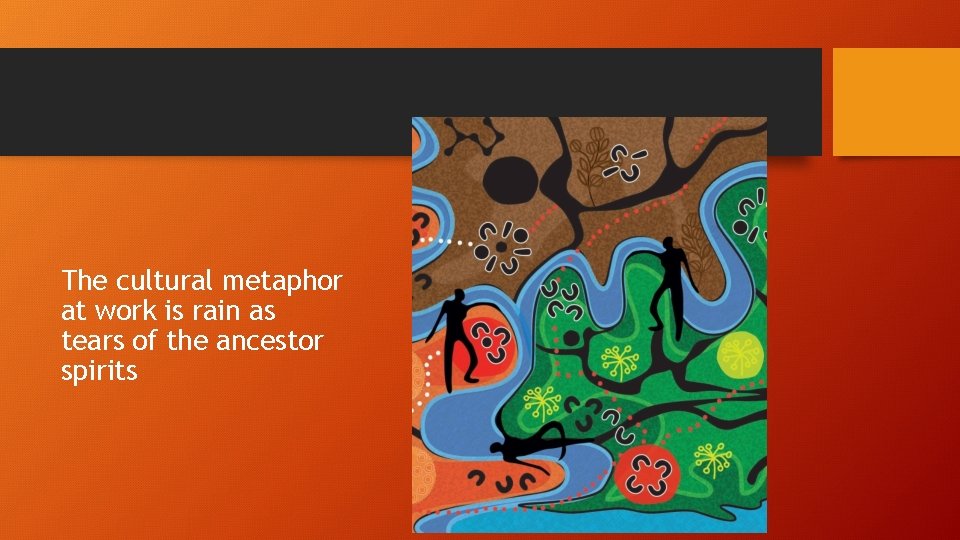

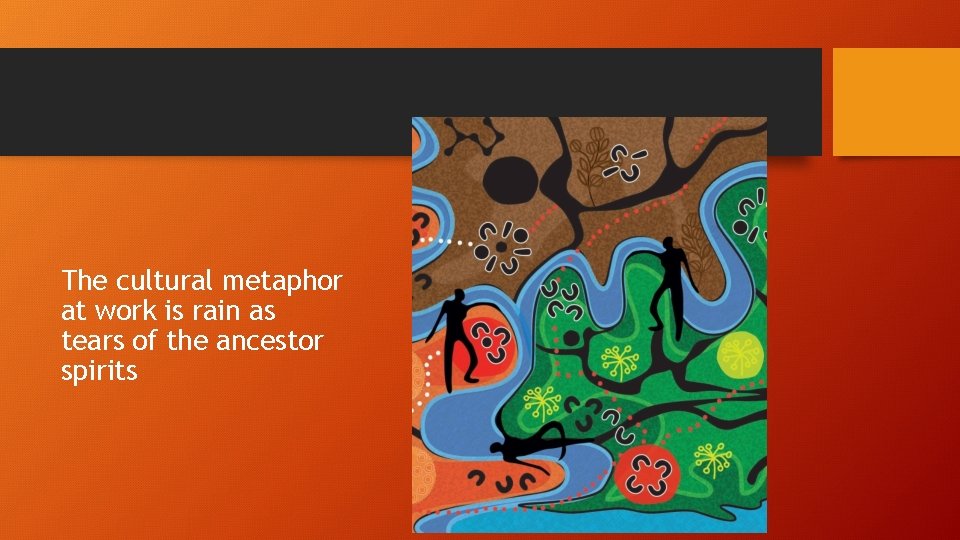

The cultural metaphor at work is rain as tears of the ancestor spirits

Angry rain: --falls when someone has done something wrong --could be the result of „someone savage” earning the wrath of the Ancestor Spirits

The word „Sorry” in Aboriginal English: „Sometimes Kardiya (non-Aboriginal people), they feel sorry for Yapa (Aboriginals) when they’re in Sorry and that means that they share their sorrows with us and that’s really good. ”

The example of the Stolen Generations what was meant by a demand for a „sorry” was more an expression of empathy than a statement of guilt; what was needed was a statement or gesture of compassion that would allow the victims of a bad policy to have their pain and suffering acknowledged

„Parents often dealt with their loss by trying to forget or by burying memories deep in their hearts or, in traditional cultural environments, by imposing a ‚sorry’ silence usually reserved for the dead. Sometimes this silence attracted the mistaken assumption from non-Indigenous observers that the children were not important to their families. ”