CSCE608 Database Systems Fall 2020 Instructor Jianer Chen

CSCE-608 Database Systems Fall 2020 Instructor: Jianer Chen Office: HRBB 338 C Phone: 845 -4259 Email: chen@cse. tamu. edu Notes 26: Locking Protocols

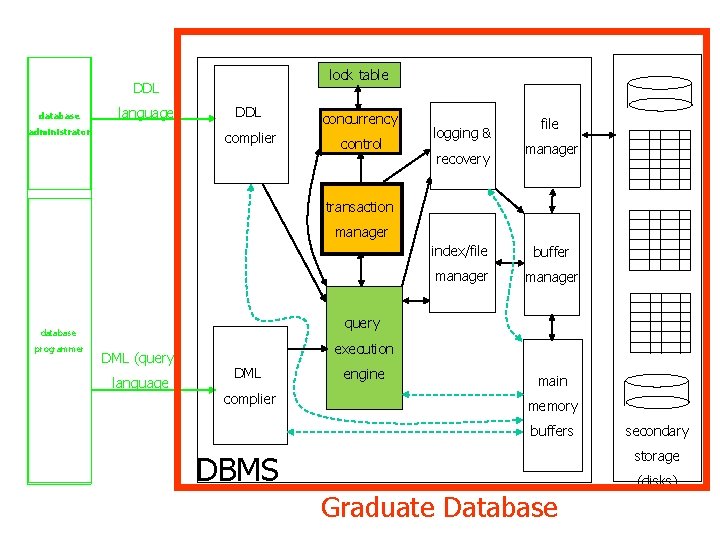

lock table DDL database language administrator DDL complier concurrency control logging & recovery file manager transaction manager buffer manager query database programmer index/file DML (query) language execution DML complier engine main memory buffers secondary storage DBMS Graduate Database (disks)

Observation. • In a schedule of a collection of transactions, if for every transaction T, the actions of T are scheduled consecutively without interlacing with actions from other transactions, then surely all transactions satisfy the Isolation condition. A schedule is serializable if it is equivalent to a serial schedule.

Conflict-Serializability (A sufficient condition for serializability) Two actions conflict if either they are by the same transaction, or they are by two transactions on the same element and at least one of the actions is write • Swapping two non-conflicting actions gives an equivalent schedule. • A schedule S 1 is conflict-serializable if it can be converted into a serial schedule by swapping nonconflicting actions. • A conflict-serializable schedule is serializable. • A serializable schedule may not be conflict-serializable. • How do we know if a schedule is conflict-serializable?

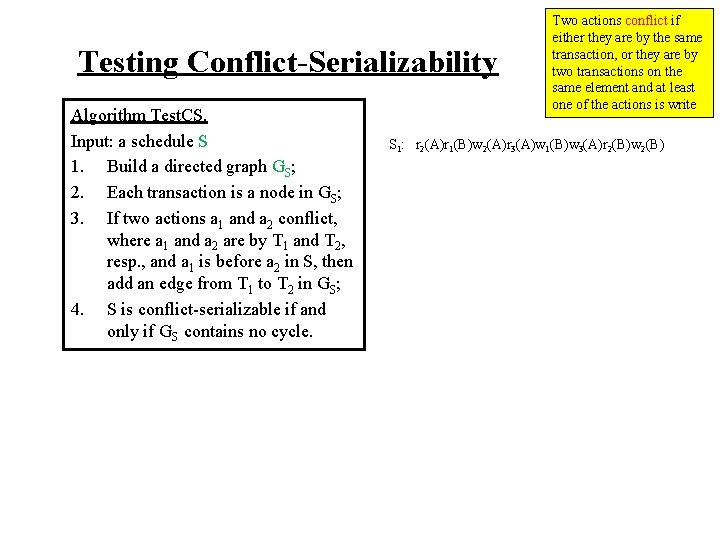

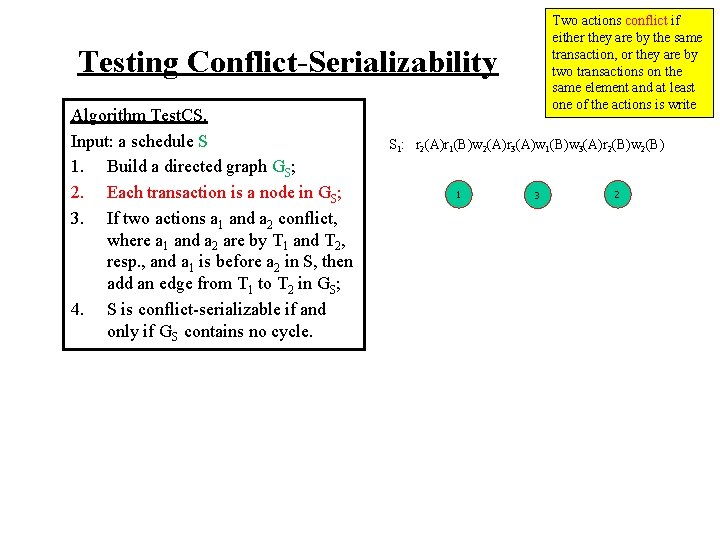

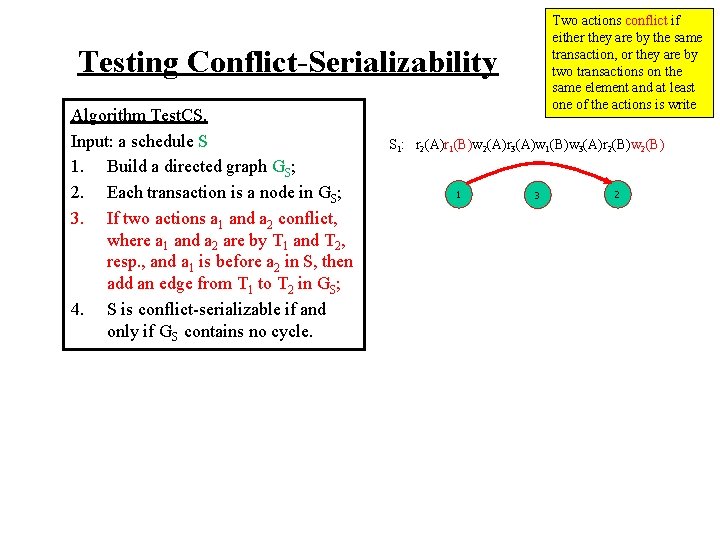

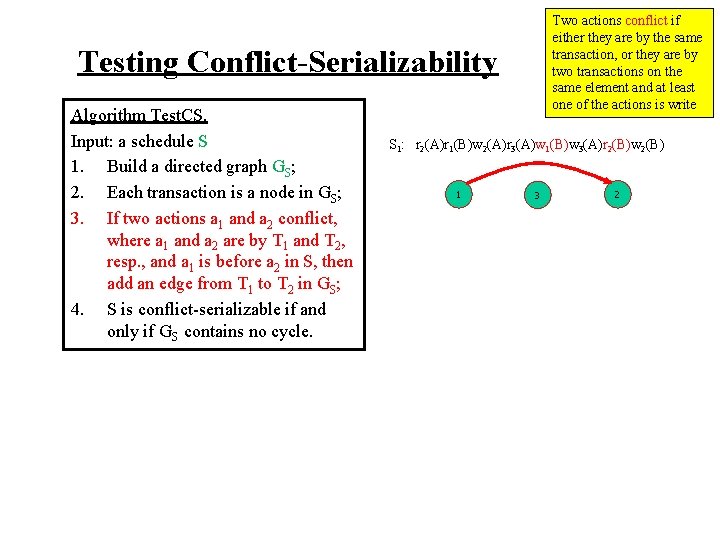

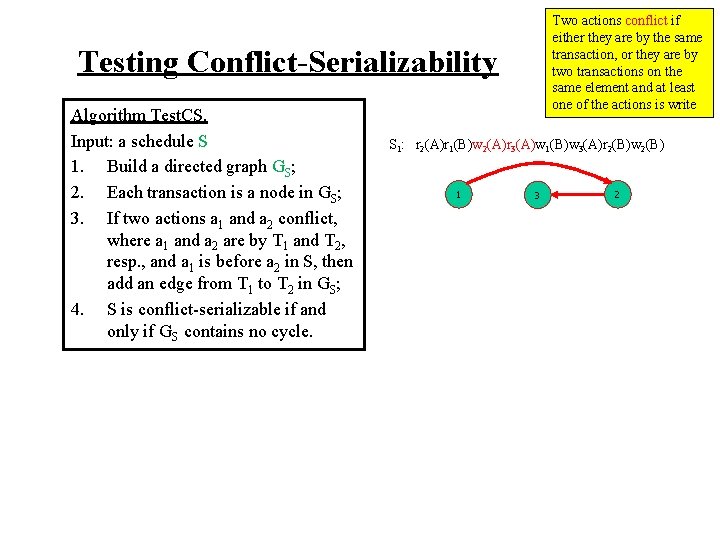

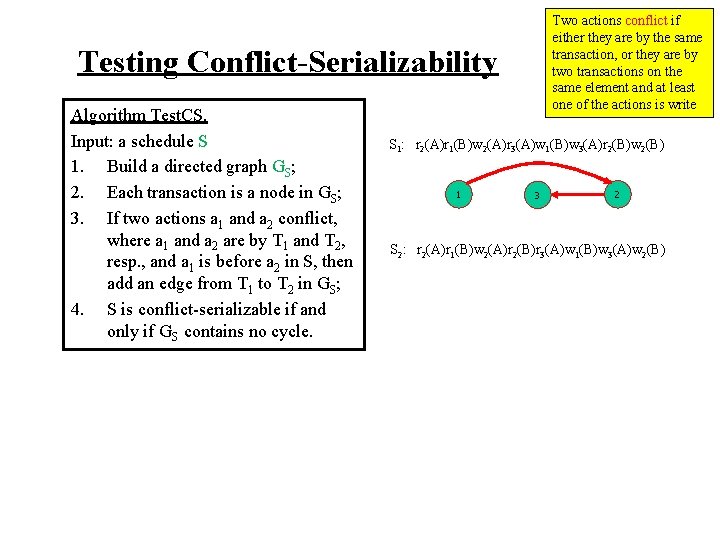

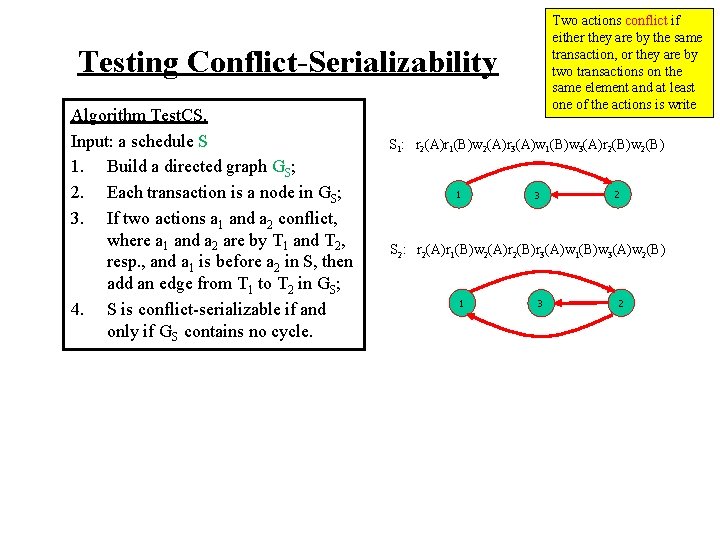

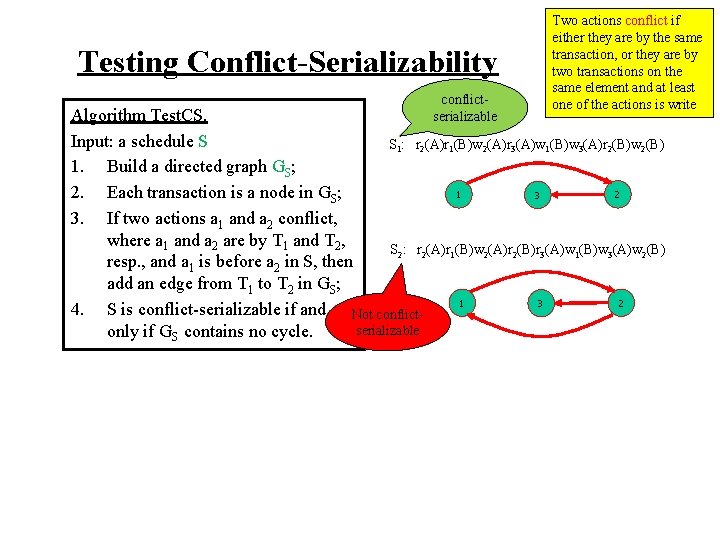

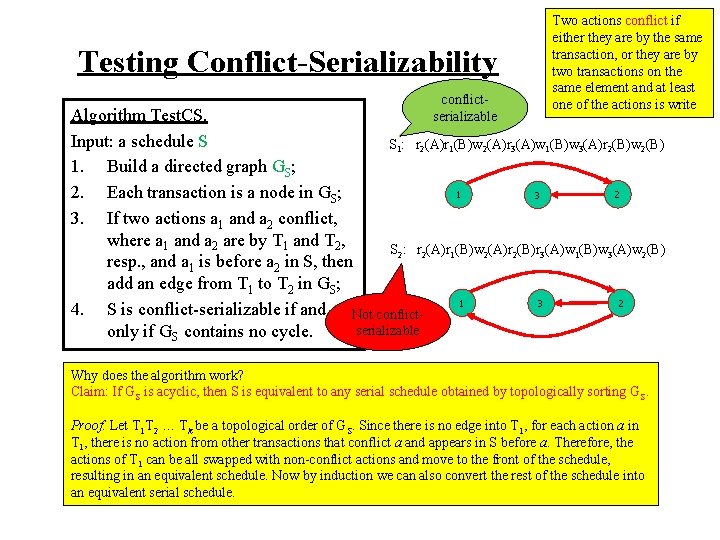

Testing Conflict-Serializability Algorithm Test. CS. Input: a schedule S 1. Build a directed graph GS; 2. Each transaction is a node in GS; 3. If two actions a 1 and a 2 conflict, where a 1 and a 2 are by T 1 and T 2, resp. , and a 1 is before a 2 in S, then add an edge from T 1 to T 2 in GS; 4. S is conflict-serializable if and only if GS contains no cycle. Two actions conflict if either they are by the same transaction, or they are by two transactions on the same element and at least one of the actions is write

Testing Conflict-Serializability Algorithm Test. CS. Input: a schedule S 1. Build a directed graph GS; 2. Each transaction is a node in GS; 3. If two actions a 1 and a 2 conflict, where a 1 and a 2 are by T 1 and T 2, resp. , and a 1 is before a 2 in S, then add an edge from T 1 to T 2 in GS; 4. S is conflict-serializable if and only if GS contains no cycle. Two actions conflict if either they are by the same transaction, or they are by two transactions on the same element and at least one of the actions is write S 1: r 2(A)r 1(B)w 2(A)r 3(A)w 1(B)w 3(A)r 2(B)w 2(B)

Two actions conflict if either they are by the same transaction, or they are by two transactions on the same element and at least one of the actions is write Testing Conflict-Serializability Algorithm Test. CS. Input: a schedule S 1. Build a directed graph GS; 2. Each transaction is a node in GS; 3. If two actions a 1 and a 2 conflict, where a 1 and a 2 are by T 1 and T 2, resp. , and a 1 is before a 2 in S, then add an edge from T 1 to T 2 in GS; 4. S is conflict-serializable if and only if GS contains no cycle. S 1: r 2(A)r 1(B)w 2(A)r 3(A)w 1(B)w 3(A)r 2(B)w 2(B) 1 3 2

Two actions conflict if either they are by the same transaction, or they are by two transactions on the same element and at least one of the actions is write Testing Conflict-Serializability Algorithm Test. CS. Input: a schedule S 1. Build a directed graph GS; 2. Each transaction is a node in GS; 3. If two actions a 1 and a 2 conflict, where a 1 and a 2 are by T 1 and T 2, resp. , and a 1 is before a 2 in S, then add an edge from T 1 to T 2 in GS; 4. S is conflict-serializable if and only if GS contains no cycle. S 1: r 2(A)r 1(B)w 2(A)r 3(A)w 1(B)w 3(A)r 2(B)w 2(B) 1 3 2

Two actions conflict if either they are by the same transaction, or they are by two transactions on the same element and at least one of the actions is write Testing Conflict-Serializability Algorithm Test. CS. Input: a schedule S 1. Build a directed graph GS; 2. Each transaction is a node in GS; 3. If two actions a 1 and a 2 conflict, where a 1 and a 2 are by T 1 and T 2, resp. , and a 1 is before a 2 in S, then add an edge from T 1 to T 2 in GS; 4. S is conflict-serializable if and only if GS contains no cycle. S 1: r 2(A)r 1(B)w 2(A)r 3(A)w 1(B)w 3(A)r 2(B)w 2(B) 1 3 2

Two actions conflict if either they are by the same transaction, or they are by two transactions on the same element and at least one of the actions is write Testing Conflict-Serializability Algorithm Test. CS. Input: a schedule S 1. Build a directed graph GS; 2. Each transaction is a node in GS; 3. If two actions a 1 and a 2 conflict, where a 1 and a 2 are by T 1 and T 2, resp. , and a 1 is before a 2 in S, then add an edge from T 1 to T 2 in GS; 4. S is conflict-serializable if and only if GS contains no cycle. S 1: r 2(A)r 1(B)w 2(A)r 3(A)w 1(B)w 3(A)r 2(B)w 2(B) 1 3 2

Two actions conflict if either they are by the same transaction, or they are by two transactions on the same element and at least one of the actions is write Testing Conflict-Serializability Algorithm Test. CS. Input: a schedule S 1. Build a directed graph GS; 2. Each transaction is a node in GS; 3. If two actions a 1 and a 2 conflict, where a 1 and a 2 are by T 1 and T 2, resp. , and a 1 is before a 2 in S, then add an edge from T 1 to T 2 in GS; 4. S is conflict-serializable if and only if GS contains no cycle. S 1: r 2(A)r 1(B)w 2(A)r 3(A)w 1(B)w 3(A)r 2(B)w 2(B) 1 3 2 S 2: r 2(A)r 1(B)w 2(A)r 2(B)r 3(A)w 1(B)w 3(A)w 2(B)

Two actions conflict if either they are by the same transaction, or they are by two transactions on the same element and at least one of the actions is write Testing Conflict-Serializability Algorithm Test. CS. Input: a schedule S 1. Build a directed graph GS; 2. Each transaction is a node in GS; 3. If two actions a 1 and a 2 conflict, where a 1 and a 2 are by T 1 and T 2, resp. , and a 1 is before a 2 in S, then add an edge from T 1 to T 2 in GS; 4. S is conflict-serializable if and only if GS contains no cycle. S 1: r 2(A)r 1(B)w 2(A)r 3(A)w 1(B)w 3(A)r 2(B)w 2(B) 1 3 2 S 2: r 2(A)r 1(B)w 2(A)r 2(B)r 3(A)w 1(B)w 3(A)w 2(B) 1 3 2

Testing Conflict-Serializability conflictserializable Two actions conflict if either they are by the same transaction, or they are by two transactions on the same element and at least one of the actions is write Algorithm Test. CS. Input: a schedule S S 1: r 2(A)r 1(B)w 2(A)r 3(A)w 1(B)w 3(A)r 2(B)w 2(B) 1. Build a directed graph GS; 1 2 2. Each transaction is a node in GS; 3 3. If two actions a 1 and a 2 conflict, where a 1 and a 2 are by T 1 and T 2, S 2: r 2(A)r 1(B)w 2(A)r 2(B)r 3(A)w 1(B)w 3(A)w 2(B) resp. , and a 1 is before a 2 in S, then add an edge from T 1 to T 2 in GS; 1 2 3 4. S is conflict-serializable if and Not conflictserializable only if GS contains no cycle.

Testing Conflict-Serializability conflictserializable Two actions conflict if either they are by the same transaction, or they are by two transactions on the same element and at least one of the actions is write Algorithm Test. CS. Input: a schedule S S 1: r 2(A)r 1(B)w 2(A)r 3(A)w 1(B)w 3(A)r 2(B)w 2(B) 1. Build a directed graph GS; 1 2 2. Each transaction is a node in GS; 3 3. If two actions a 1 and a 2 conflict, where a 1 and a 2 are by T 1 and T 2, S 2: r 2(A)r 1(B)w 2(A)r 2(B)r 3(A)w 1(B)w 3(A)w 2(B) resp. , and a 1 is before a 2 in S, then add an edge from T 1 to T 2 in GS; 1 2 3 4. S is conflict-serializable if and Not conflictserializable only if GS contains no cycle. Why does the algorithm work? Claim: If GS is acyclic, then S is equivalent to any serial schedule obtained by topologically sorting G S. Proof. Let T 1 T 2 … Tk be a topological order of GS. Since there is no edge into T 1, for each action a in T 1, there is no action from other transactions that conflict a and appears in S before a. Therefore, the actions of T 1 can be all swapped with non-conflict actions and move to the front of the schedule, resulting in an equivalent schedule. Now by induction we can also convert the rest of the schedule into an equivalent serial schedule.

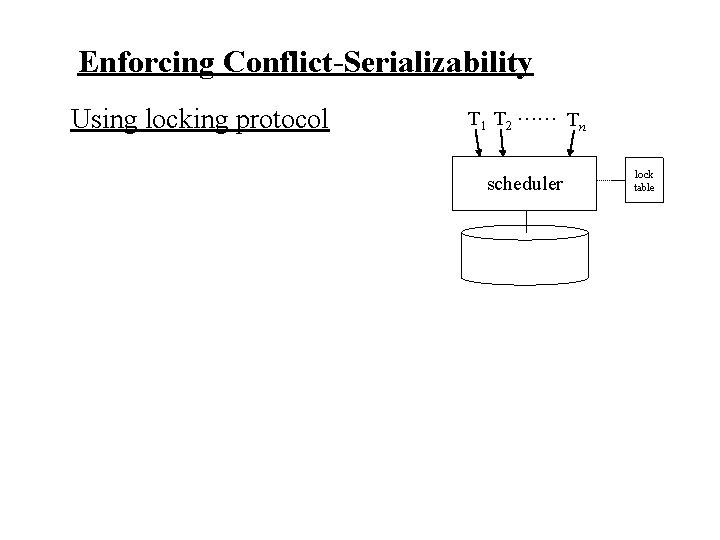

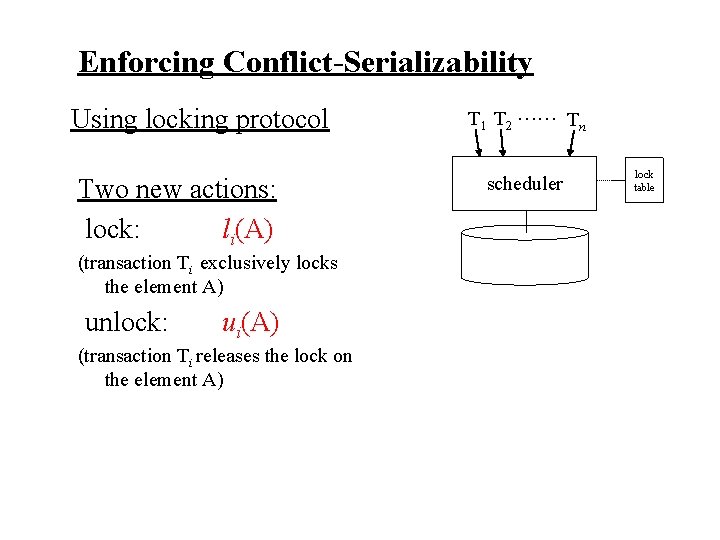

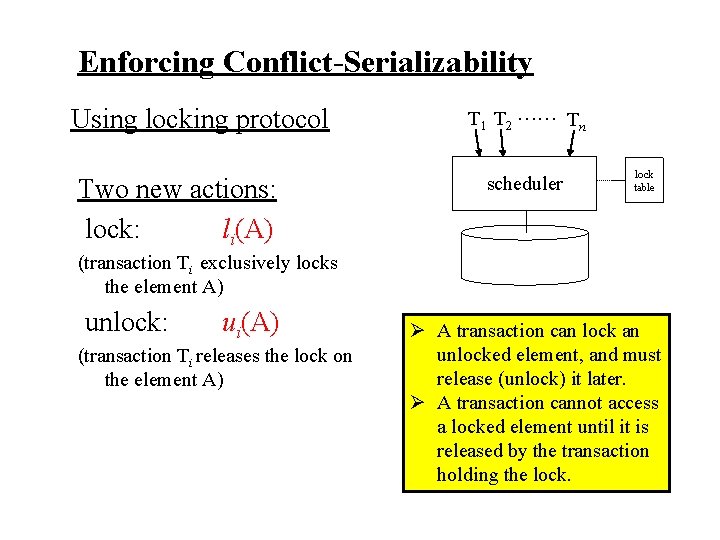

Enforcing Conflict-Serializability Using locking protocol T 1 T 2 …… Tn scheduler lock table

Enforcing Conflict-Serializability Using locking protocol Two new actions: lock: li(A) (transaction Ti exclusively locks the element A) unlock: ui(A) (transaction Ti releases the lock on the element A) T 1 T 2 …… Tn scheduler lock table

Enforcing Conflict-Serializability Using locking protocol Two new actions: lock: li(A) T 1 T 2 …… Tn scheduler lock table (transaction Ti exclusively locks the element A) unlock: ui(A) (transaction Ti releases the lock on the element A) Ø A transaction can lock an unlocked element, and must release (unlock) it later. Ø A transaction cannot access a locked element until it is released by the transaction holding the lock.

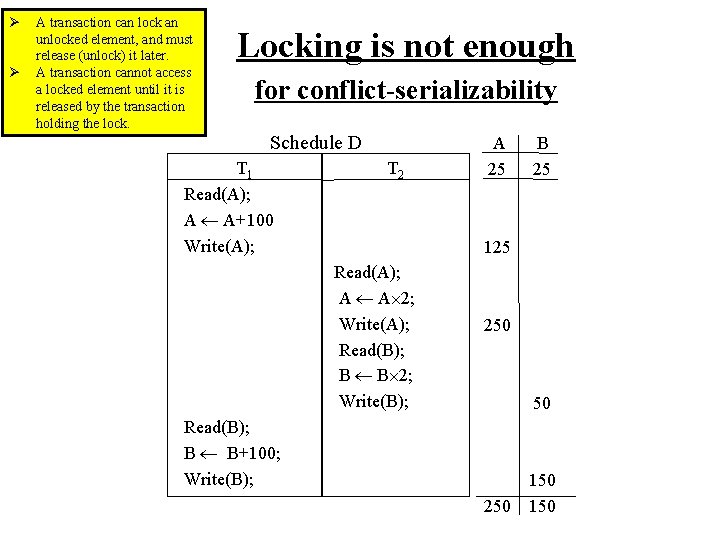

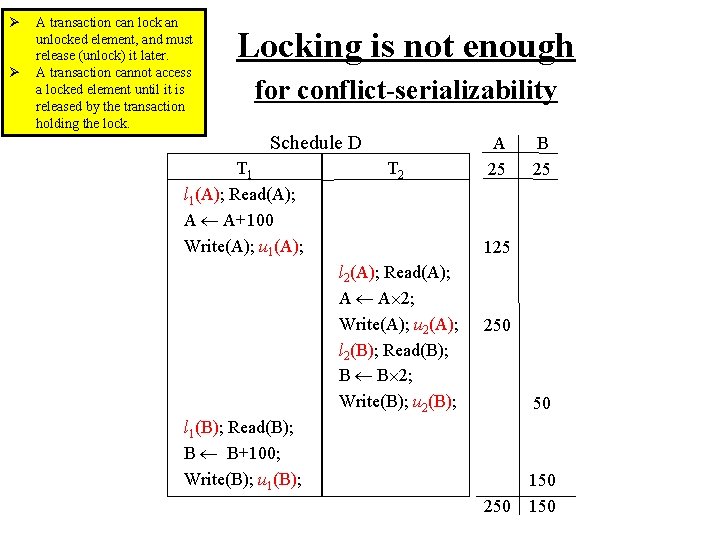

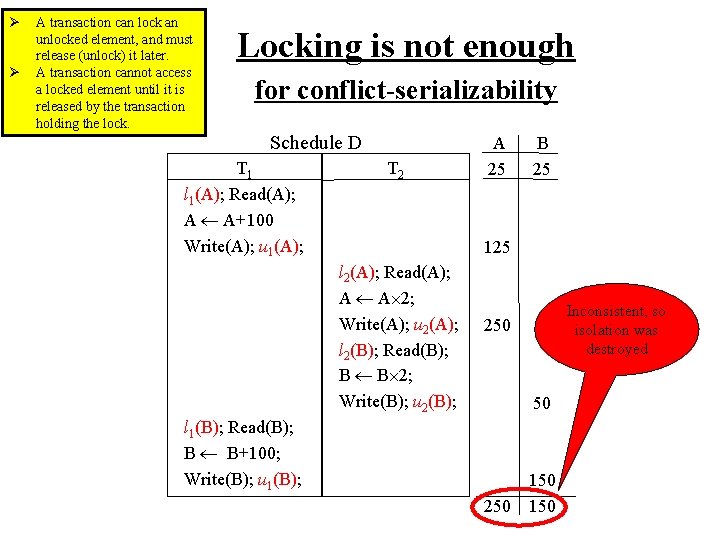

Ø Ø A transaction can lock an unlocked element, and must release (unlock) it later. A transaction cannot access a locked element until it is released by the transaction holding the lock. Locking is not enough for conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); T 2 A 25 B 25 125 Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); 250 50 Read(B); B B+100; Write(B); 250 150

Ø Ø A transaction can lock an unlocked element, and must release (unlock) it later. A transaction cannot access a locked element until it is released by the transaction holding the lock. Locking is not enough for conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); T 2 A 25 B 25 125 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(B); 250 50 l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; Write(B); u 1(B); 250 150

Ø Ø A transaction can lock an unlocked element, and must release (unlock) it later. A transaction cannot access a locked element until it is released by the transaction holding the lock. Locking is not enough for conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); T 2 A 25 B 25 125 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(B); Inconsistent, so isolation was destroyed 250 50 l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; Write(B); u 1(B); 250 150

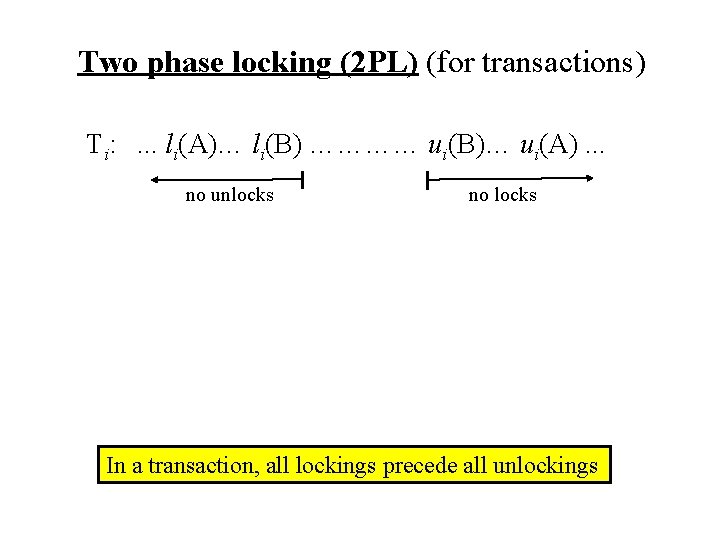

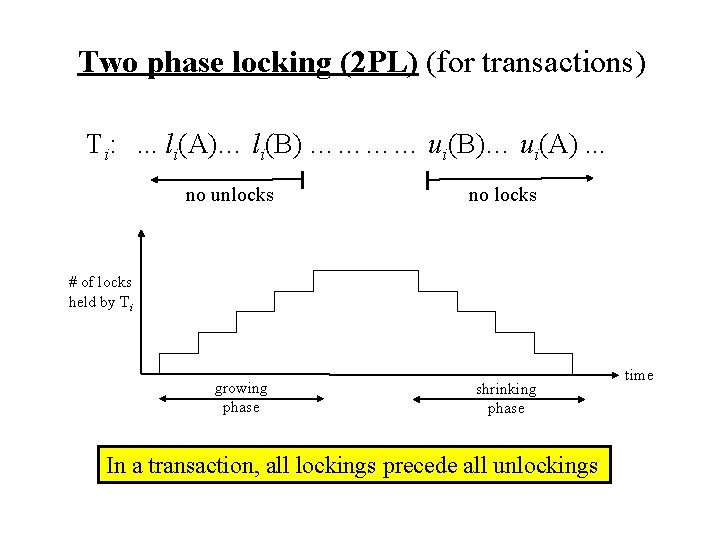

Two phase locking (2 PL) (for transactions) Ti: . . . li(A)… li(B) ………… ui(B)… ui(A). . . no unlocks no locks In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings

Two phase locking (2 PL) (for transactions) Ti: . . . li(A)… li(B) ………… ui(B)… ui(A). . . no unlocks no locks # of locks held by Ti growing phase shrinking phase In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings time

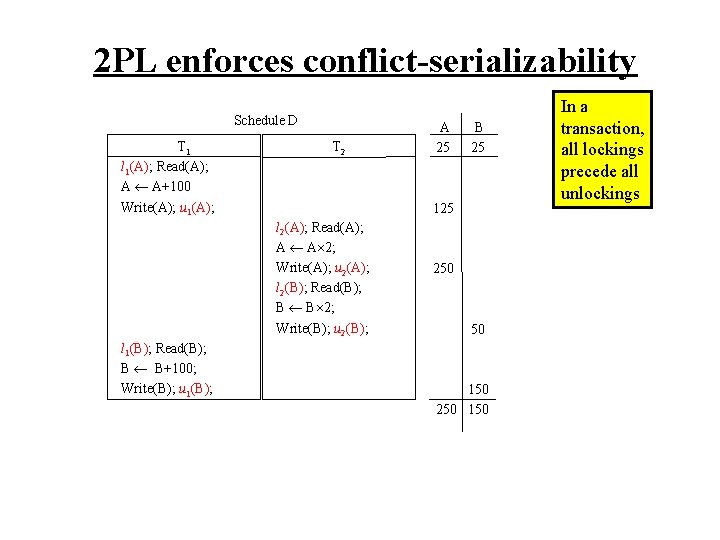

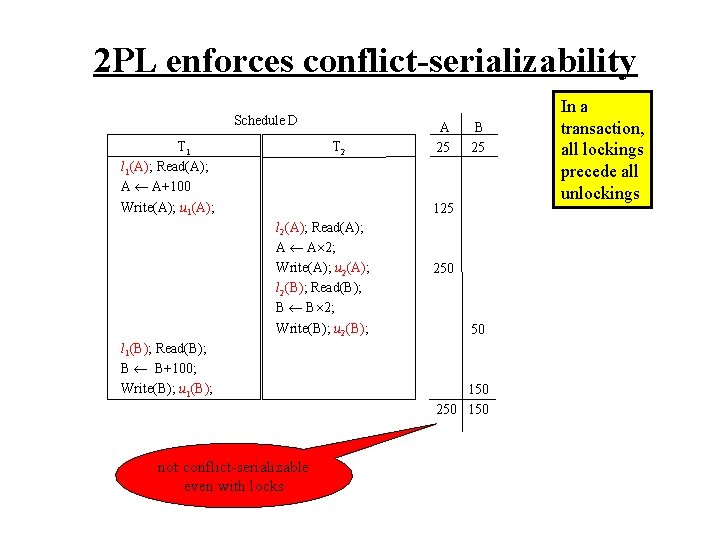

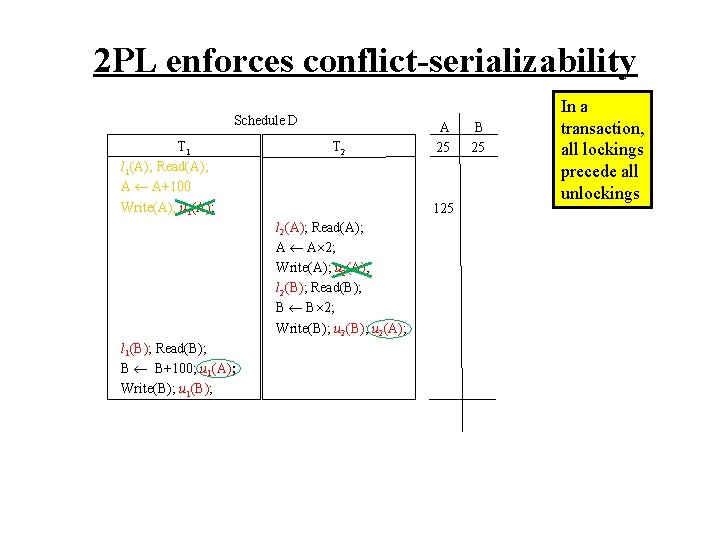

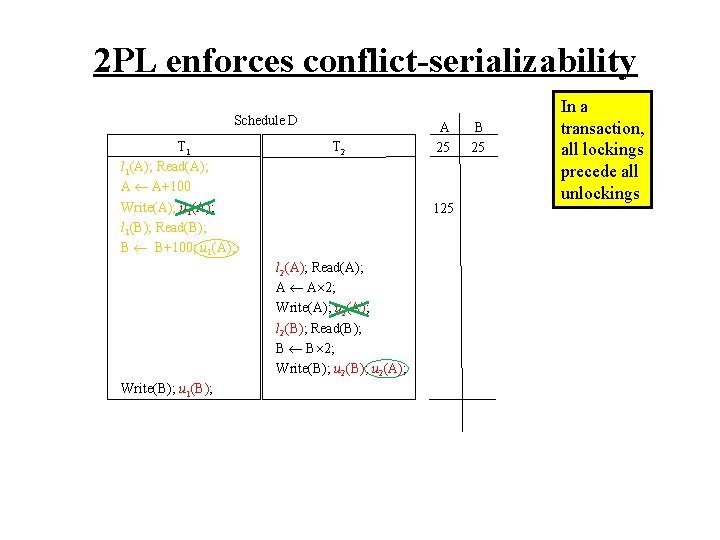

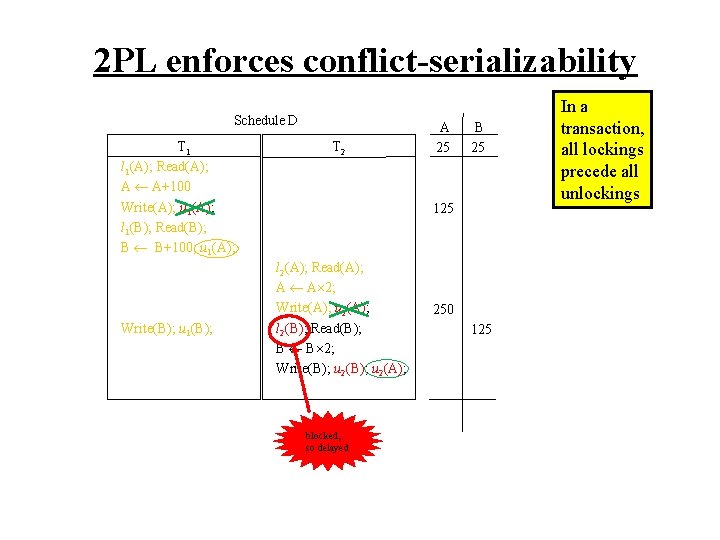

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); T 2 B 25 125 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(B); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; Write(B); u 1(B); A 25 250 50 150 250 150 In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); T 2 A 25 B 25 125 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(B); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; Write(B); u 1(B); not conflict-serializable even with locks 250 50 150 250 150 In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings

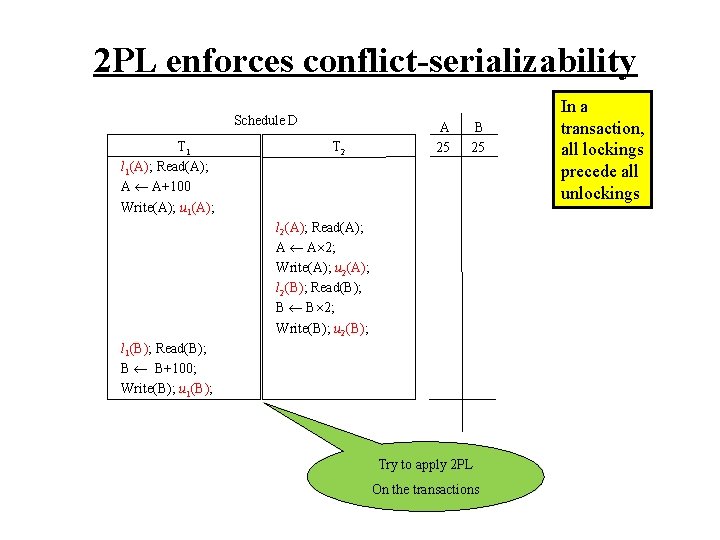

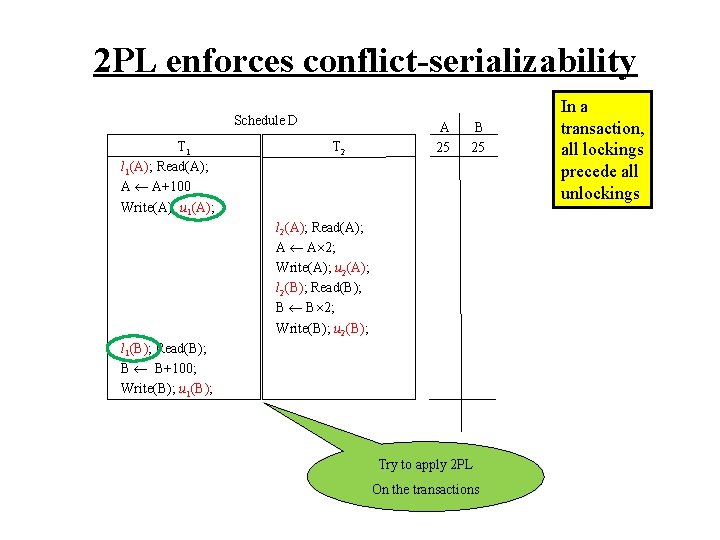

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); T 2 A 25 B 25 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(B); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; Write(B); u 1(B); Try to apply 2 PL On the transactions In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); T 2 A 25 B 25 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(B); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; Write(B); u 1(B); Try to apply 2 PL On the transactions In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings

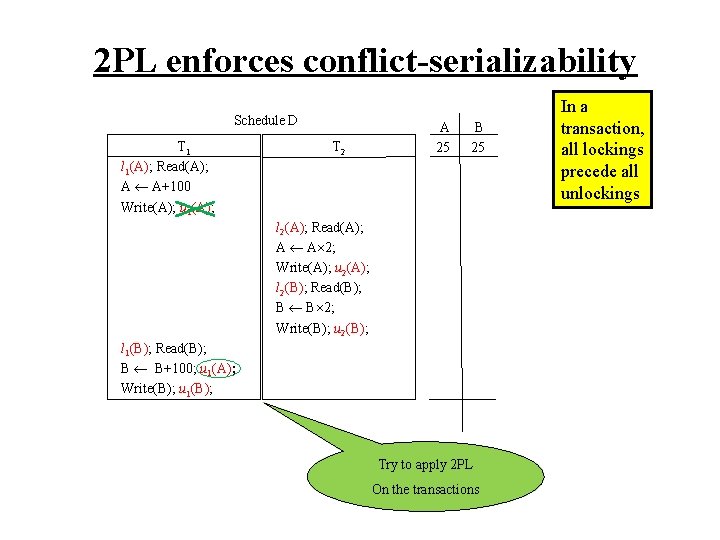

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); T 2 A 25 B 25 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(B); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; u 1(A); Write(B); u 1(B); Try to apply 2 PL On the transactions In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings

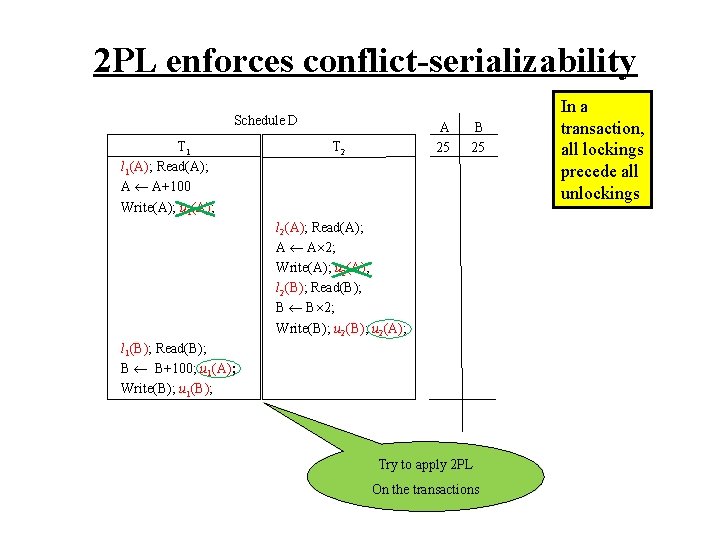

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); A 25 T 2 B 25 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(A); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; u 1(A); Write(B); u 1(B); Try to apply 2 PL On the transactions In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings

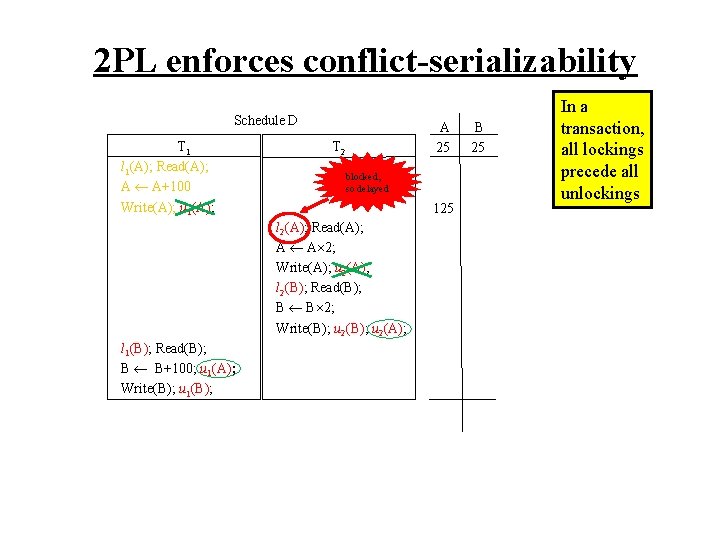

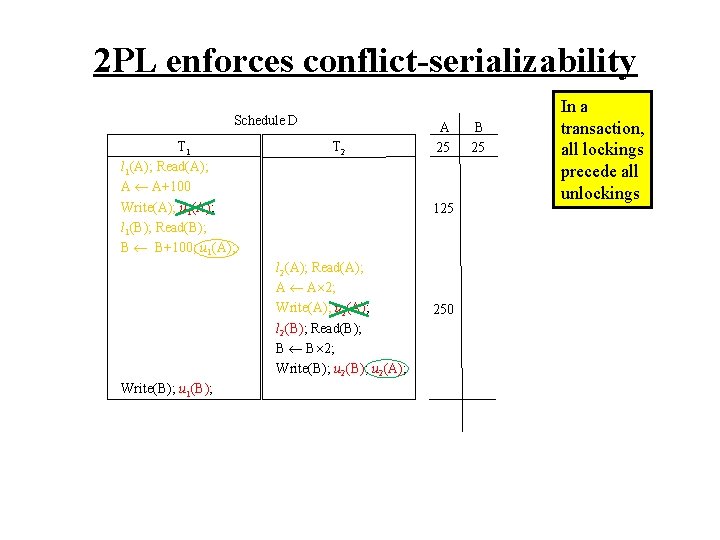

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); T 2 125 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(A); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; u 1(A); Write(B); u 1(B); A 25 B 25 In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); A 25 T 2 blocked, so delayed 125 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(A); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; u 1(A); Write(B); u 1(B); B 25 In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings

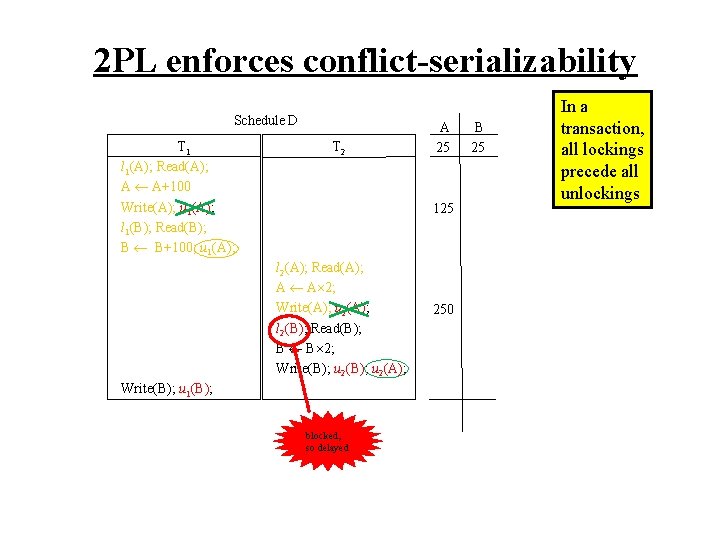

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; u 1(A); Write(B); u 1(B); A 25 T 2 blocked, so delayed 125 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(A); B 25 In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; u 1(A); Write(B); u 1(B); A 25 T 2 blocked, so delayed 125 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(A); B 25 In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; u 1(A); T 2 125 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(A); Write(B); u 1(B); A 25 B 25 In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; u 1(A); T 2 125 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(A); Write(B); u 1(B); A 25 250 B 25 In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; u 1(A); T 2 A 25 125 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(A); Write(B); u 1(B); blocked, so delayed 250 B 25 In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings

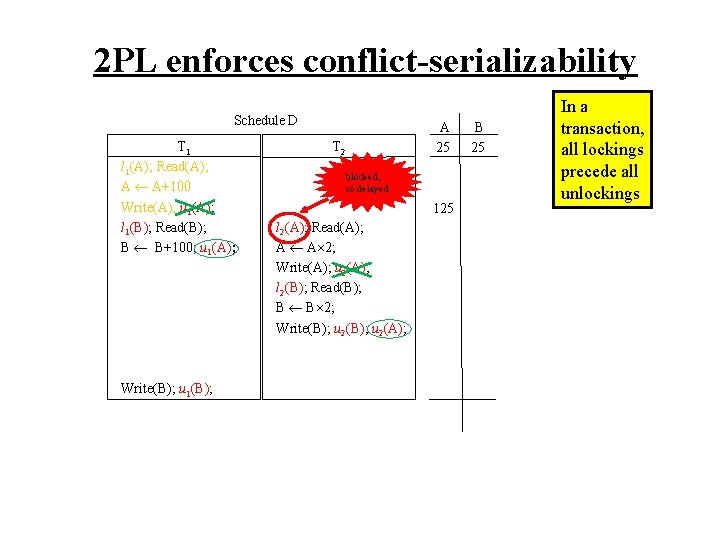

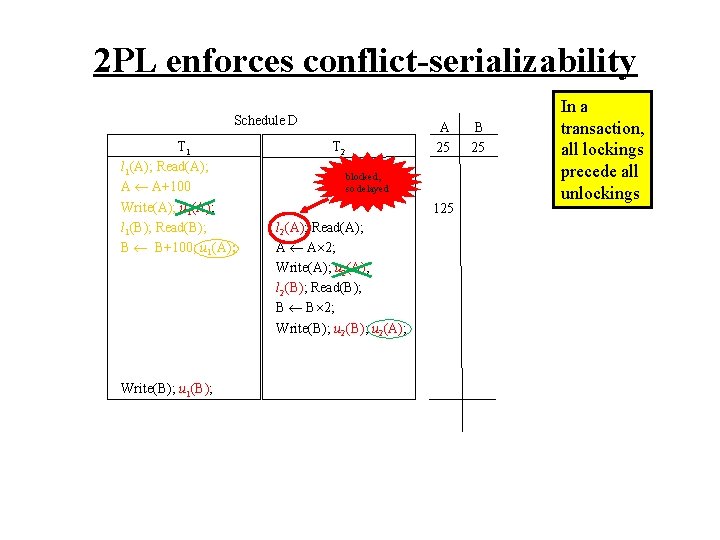

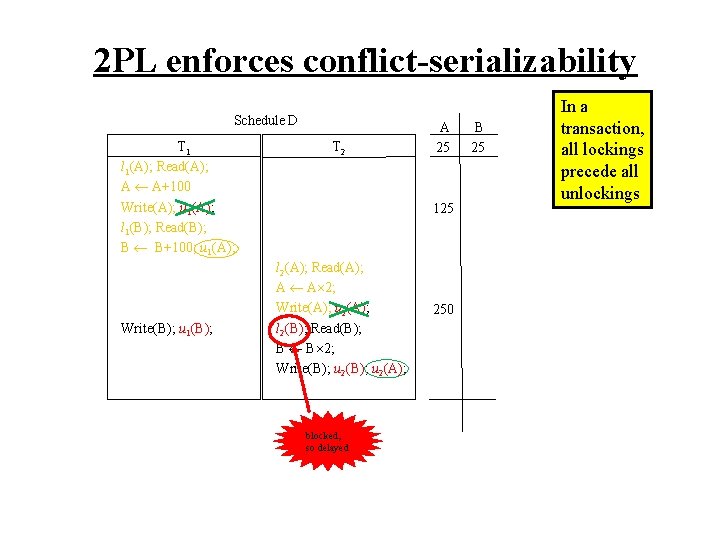

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; u 1(A); Write(B); u 1(B); T 2 A 25 125 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(A); blocked, so delayed 250 B 25 In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; u 1(A); Write(B); u 1(B); T 2 A 25 B 25 125 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(A); blocked, so delayed 250 125 In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings

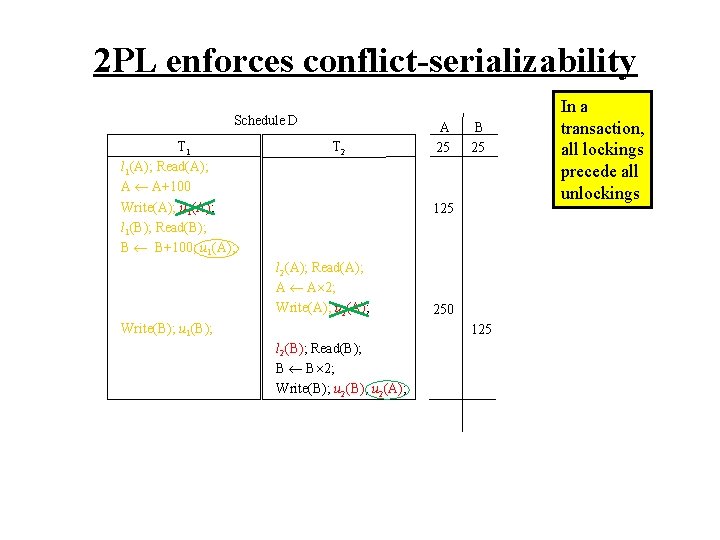

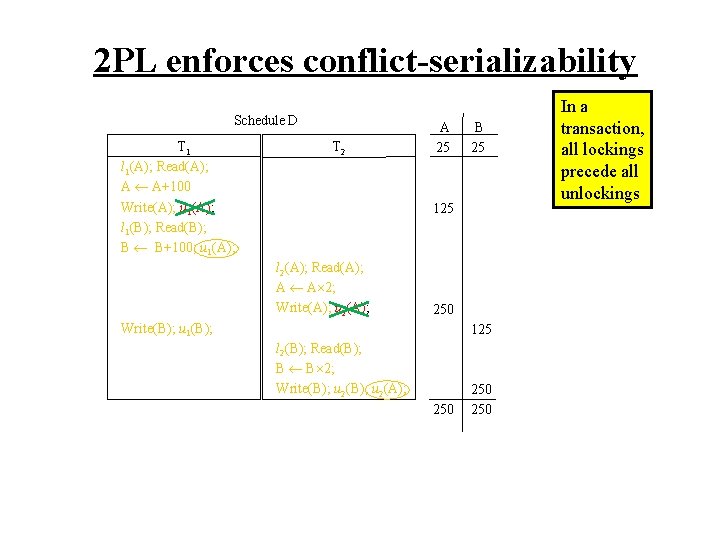

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; u 1(A); T 2 A 25 B 25 125 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); Write(B); u 1(B); 250 125 l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(A); In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; u 1(A); T 2 A 25 B 25 125 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); 250 Write(B); u 1(B); 125 l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(A); 250 250 In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings

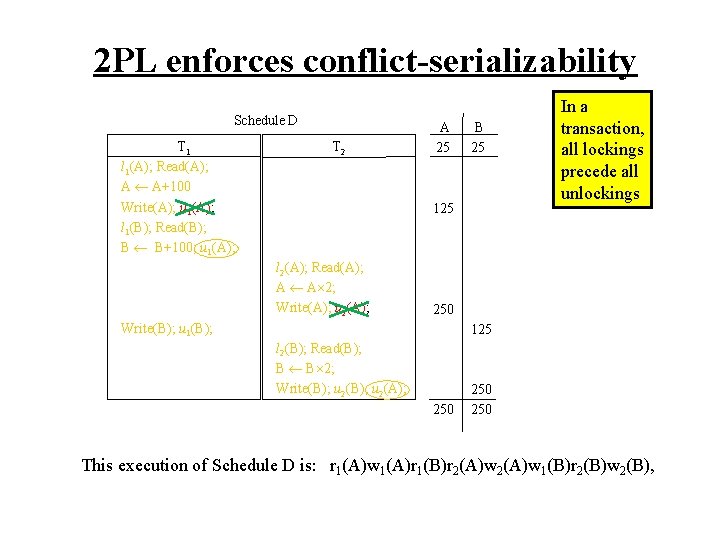

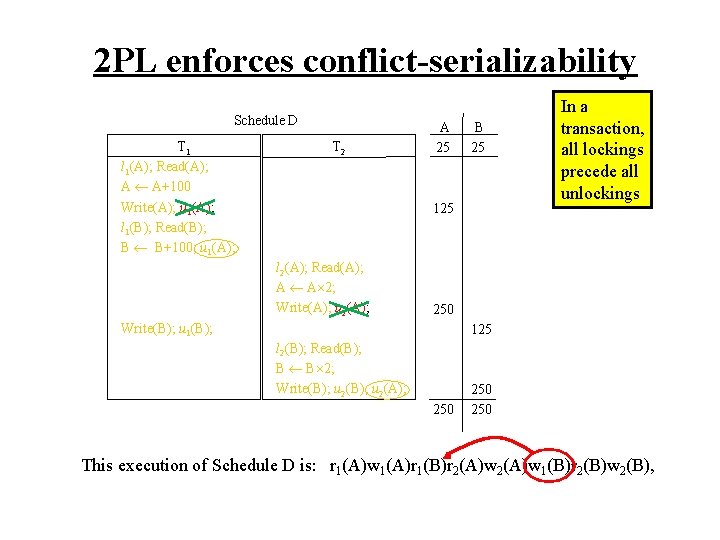

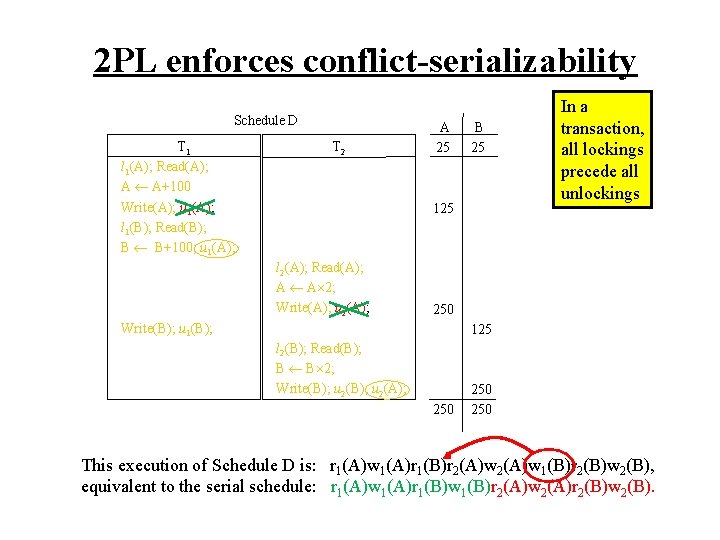

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; u 1(A); T 2 A 25 B 25 125 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings 250 Write(B); u 1(B); 125 l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(A); 250 250 This execution of Schedule D is: r 1(A)w 1(A)r 1(B)r 2(A)w 1(B)r 2(B)w 2(B),

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; u 1(A); T 2 A 25 B 25 125 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings 250 Write(B); u 1(B); 125 l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(A); 250 250 This execution of Schedule D is: r 1(A)w 1(A)r 1(B)r 2(A)w 1(B)r 2(B)w 2(B),

2 PL enforces conflict-serializability Schedule D T 1 l 1(A); Read(A); A A+100 Write(A); u 1(A); l 1(B); Read(B); B B+100; u 1(A); T 2 A 25 B 25 125 l 2(A); Read(A); A A 2; Write(A); u 2(A); In a transaction, all lockings precede all unlockings 250 Write(B); u 1(B); 125 l 2(B); Read(B); B B 2; Write(B); u 2(A); 250 250 This execution of Schedule D is: r 1(A)w 1(A)r 1(B)r 2(A)w 1(B)r 2(B)w 2(B), equivalent to the serial schedule: r 1(A)w 1(A)r 1(B)w 1(B)r 2(A)w 2(A)r 2(B)w 2(B).

Why does 2 PL work?

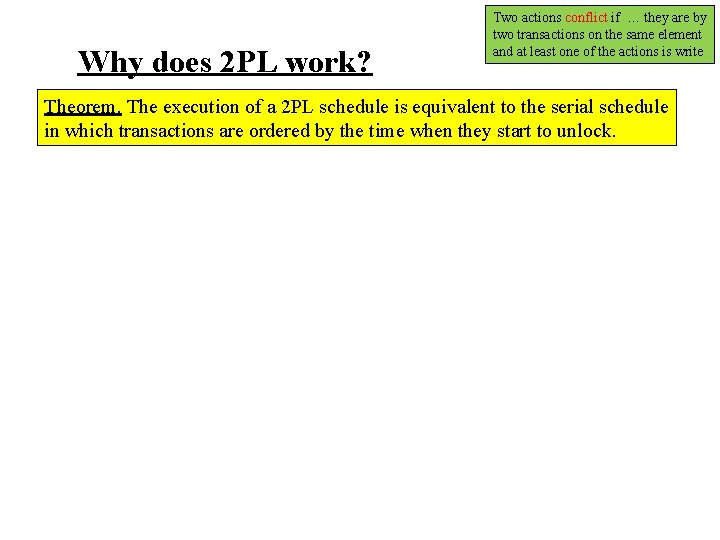

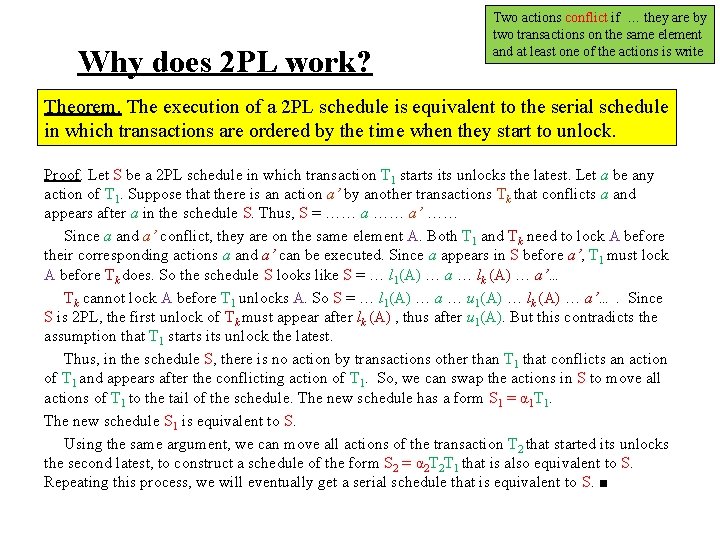

Why does 2 PL work? Two actions conflict if … they are by two transactions on the same element and at least one of the actions is write Theorem. The execution of a 2 PL schedule is equivalent to the serial schedule in which transactions are ordered by the time when they start to unlock.

Why does 2 PL work? Two actions conflict if … they are by two transactions on the same element and at least one of the actions is write Theorem. The execution of a 2 PL schedule is equivalent to the serial schedule in which transactions are ordered by the time when they start to unlock. Proof. Let S be a 2 PL schedule in which transaction T 1 starts its unlocks the latest. Let a be any action of T 1. Suppose that there is an action a’ by another transactions Tk that conflicts a and appears after a in the schedule S. Thus, S = …… a’ ……

Why does 2 PL work? Two actions conflict if … they are by two transactions on the same element and at least one of the actions is write Theorem. The execution of a 2 PL schedule is equivalent to the serial schedule in which transactions are ordered by the time when they start to unlock. Proof. Let S be a 2 PL schedule in which transaction T 1 starts its unlocks the latest. Let a be any action of T 1. Suppose that there is an action a’ by another transactions Tk that conflicts a and appears after a in the schedule S. Thus, S = …… a’ …… Since a and a’ conflict, they are on the same element A. Both T 1 and Tk need to lock A before their corresponding actions a and a’ can be executed. Since a appears in S before a’, T 1 must lock A before Tk does. So the schedule S looks like S = … l 1(A) … a … lk (A) … a’…

Why does 2 PL work? Two actions conflict if … they are by two transactions on the same element and at least one of the actions is write Theorem. The execution of a 2 PL schedule is equivalent to the serial schedule in which transactions are ordered by the time when they start to unlock. Proof. Let S be a 2 PL schedule in which transaction T 1 starts its unlocks the latest. Let a be any action of T 1. Suppose that there is an action a’ by another transactions Tk that conflicts a and appears after a in the schedule S. Thus, S = …… a’ …… Since a and a’ conflict, they are on the same element A. Both T 1 and Tk need to lock A before their corresponding actions a and a’ can be executed. Since a appears in S before a’, T 1 must lock A before Tk does. So the schedule S looks like S = … l 1(A) … a … lk (A) … a’… Tk cannot lock A before T 1 unlocks A. So S = … l 1(A) … a … u 1(A) … lk (A) … a’…. Since S is 2 PL, the first unlock of Tk must appear after lk (A) , thus after u 1(A). But this contradicts the assumption that T 1 starts its unlock the latest.

Why does 2 PL work? Two actions conflict if … they are by two transactions on the same element and at least one of the actions is write Theorem. The execution of a 2 PL schedule is equivalent to the serial schedule in which transactions are ordered by the time when they start to unlock. Proof. Let S be a 2 PL schedule in which transaction T 1 starts its unlocks the latest. Let a be any action of T 1. Suppose that there is an action a’ by another transactions Tk that conflicts a and appears after a in the schedule S. Thus, S = …… a’ …… Since a and a’ conflict, they are on the same element A. Both T 1 and Tk need to lock A before their corresponding actions a and a’ can be executed. Since a appears in S before a’, T 1 must lock A before Tk does. So the schedule S looks like S = … l 1(A) … a … lk (A) … a’… Tk cannot lock A before T 1 unlocks A. So S = … l 1(A) … a … u 1(A) … lk (A) … a’…. Since S is 2 PL, the first unlock of Tk must appear after lk (A) , thus after u 1(A). But this contradicts the assumption that T 1 starts its unlock the latest. Thus, in the schedule S, there is no action by transactions other than T 1 that conflicts an action of T 1 and appears after the conflicting action of T 1. So, we can swap the actions in S to move all actions of T 1 to the tail of the schedule. The new schedule has a form S 1 = α 1 T 1. The new schedule S 1 is equivalent to S.

Why does 2 PL work? Two actions conflict if … they are by two transactions on the same element and at least one of the actions is write Theorem. The execution of a 2 PL schedule is equivalent to the serial schedule in which transactions are ordered by the time when they start to unlock. Proof. Let S be a 2 PL schedule in which transaction T 1 starts its unlocks the latest. Let a be any action of T 1. Suppose that there is an action a’ by another transactions Tk that conflicts a and appears after a in the schedule S. Thus, S = …… a’ …… Since a and a’ conflict, they are on the same element A. Both T 1 and Tk need to lock A before their corresponding actions a and a’ can be executed. Since a appears in S before a’, T 1 must lock A before Tk does. So the schedule S looks like S = … l 1(A) … a … lk (A) … a’… Tk cannot lock A before T 1 unlocks A. So S = … l 1(A) … a … u 1(A) … lk (A) … a’…. Since S is 2 PL, the first unlock of Tk must appear after lk (A) , thus after u 1(A). But this contradicts the assumption that T 1 starts its unlock the latest. Thus, in the schedule S, there is no action by transactions other than T 1 that conflicts an action of T 1 and appears after the conflicting action of T 1. So, we can swap the actions in S to move all actions of T 1 to the tail of the schedule. The new schedule has a form S 1 = α 1 T 1. The new schedule S 1 is equivalent to S. Using the same argument, we can move all actions of the transaction T 2 that started its unlocks the second latest, to construct a schedule of the form S 2 = α 2 T 2 T 1 that is also equivalent to S. Repeating this process, we will eventually get a serial schedule that is equivalent to S. ■

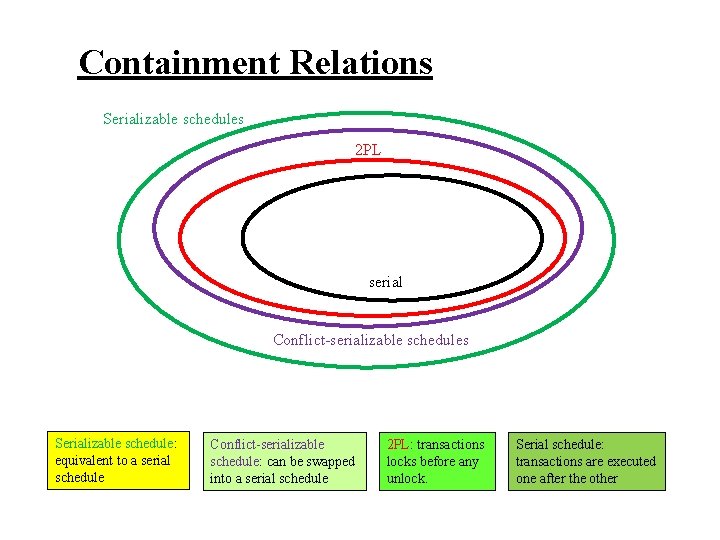

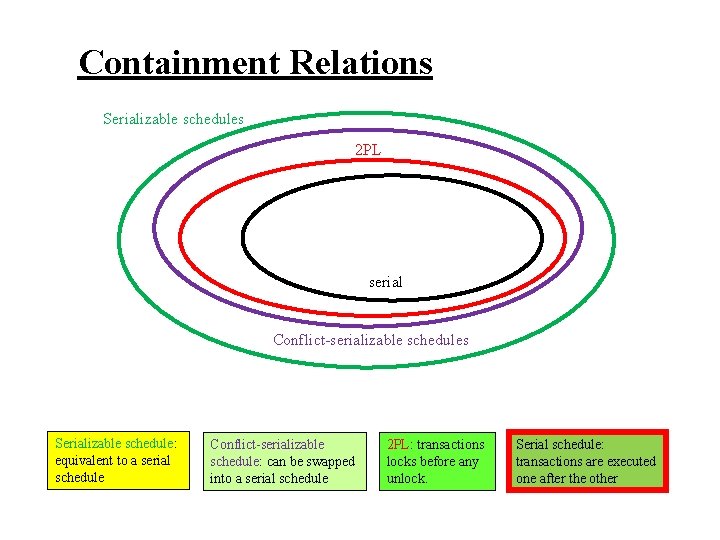

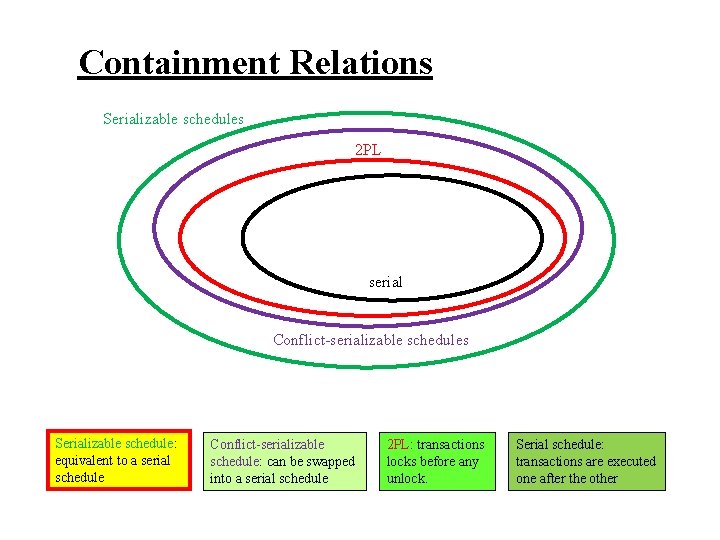

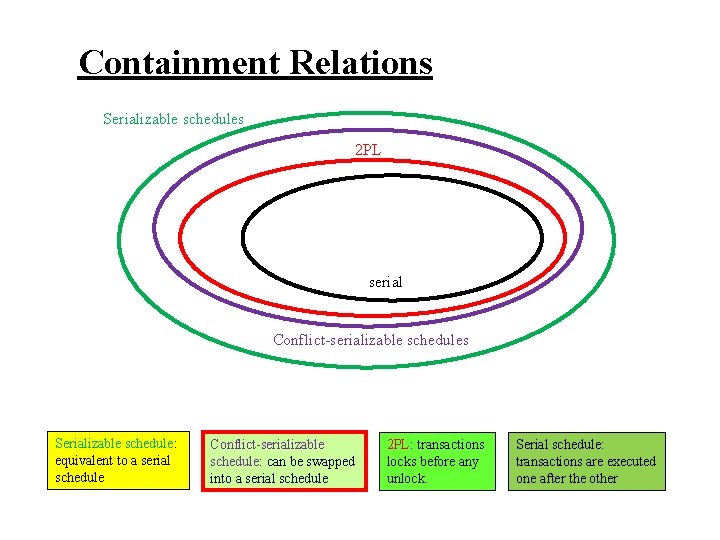

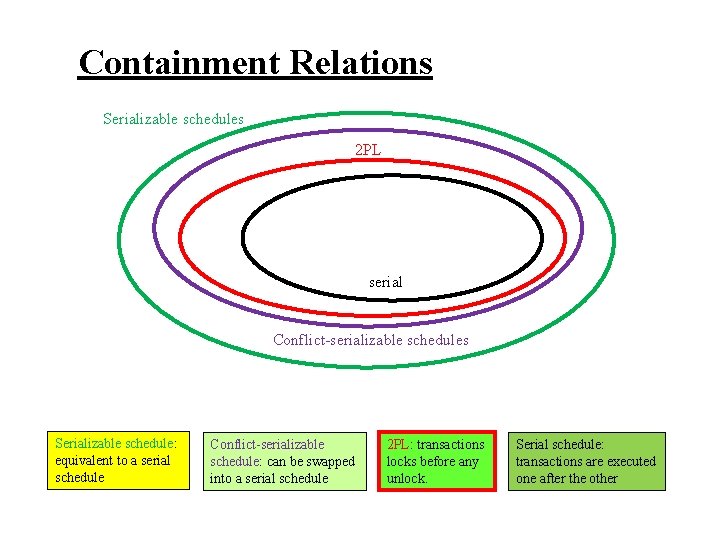

Containment Relations Serializable schedules 2 PL serial Conflict-serializable schedules Serializable schedule: equivalent to a serial schedule Conflict-serializable schedule: can be swapped into a serial schedule 2 PL: transactions locks before any unlock. Serial schedule: transactions are executed one after the other

Containment Relations Serializable schedules 2 PL serial Conflict-serializable schedules Serializable schedule: equivalent to a serial schedule Conflict-serializable schedule: can be swapped into a serial schedule 2 PL: transactions locks before any unlock. Serial schedule: transactions are executed one after the other

Containment Relations Serializable schedules 2 PL serial Conflict-serializable schedules Serializable schedule: equivalent to a serial schedule Conflict-serializable schedule: can be swapped into a serial schedule 2 PL: transactions locks before any unlock. Serial schedule: transactions are executed one after the other

Containment Relations Serializable schedules 2 PL serial Conflict-serializable schedules Serializable schedule: equivalent to a serial schedule Conflict-serializable schedule: can be swapped into a serial schedule 2 PL: transactions locks before any unlock. Serial schedule: transactions are executed one after the other

Containment Relations Serializable schedules 2 PL serial Conflict-serializable schedules Serializable schedule: equivalent to a serial schedule Conflict-serializable schedule: can be swapped into a serial schedule 2 PL: transactions locks before any unlock. Serial schedule: transactions are executed one after the other

Beyond the simple 2 PL protocol, it is all a matter of improving performance and allowing more concurrency …….

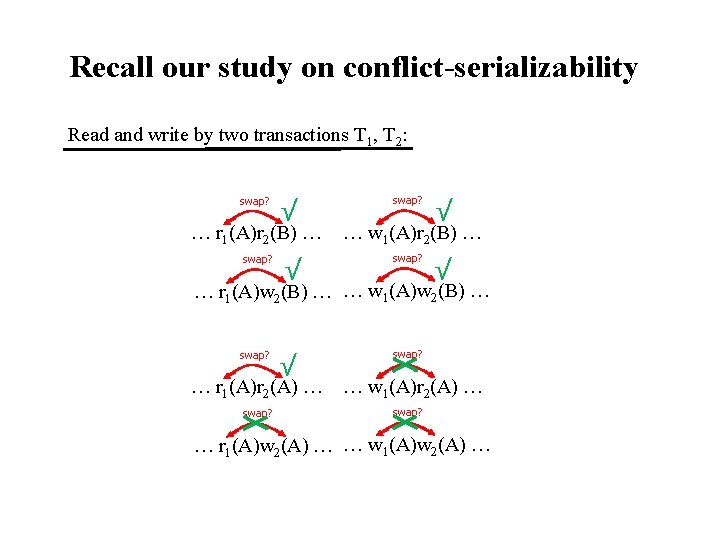

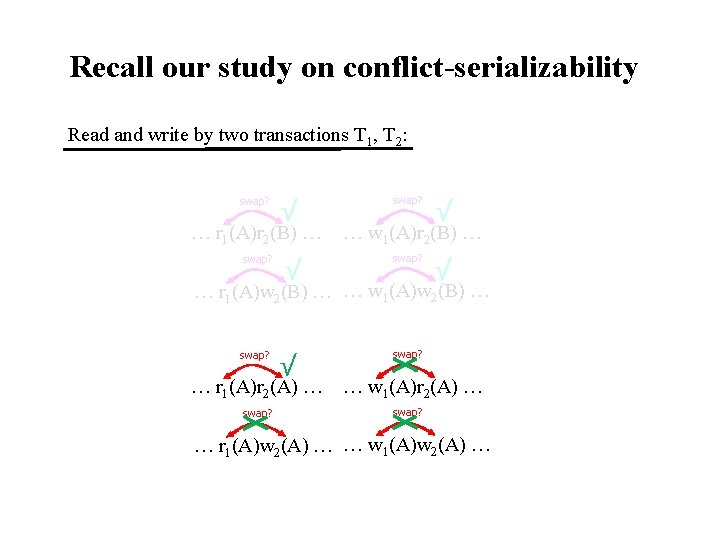

Recall our study on conflict-serializability Read and write by two transactions T 1, T 2: swap? √ … r 1(A)r 2(B) … swap? √ … w 1(A)r 2(B) … swap? √ … r 1(A)w 2(B) … … w 1(A)w 2(B) … swap? √ … r 1(A)r 2(A) … swap? … w 1(A)r 2(A) … swap? … r 1(A)w 2(A) … … w 1(A)w 2(A) …

Recall our study on conflict-serializability Read and write by two transactions T 1, T 2: swap? √ … r 1(A)r 2(B) … swap? √ … w 1(A)r 2(B) … swap? √ … r 1(A)w 2(B) … … w 1(A)w 2(B) … swap? √ … r 1(A)r 2(A) … swap? … w 1(A)r 2(A) … swap? … r 1(A)w 2(A) … … w 1(A)w 2(A) …

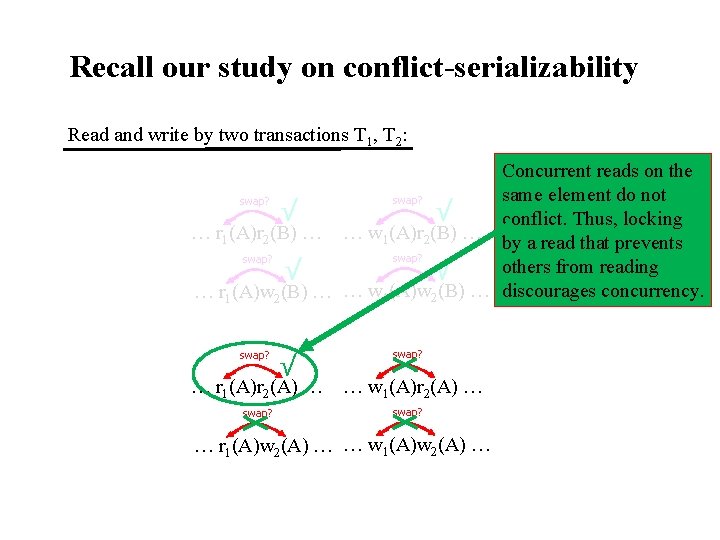

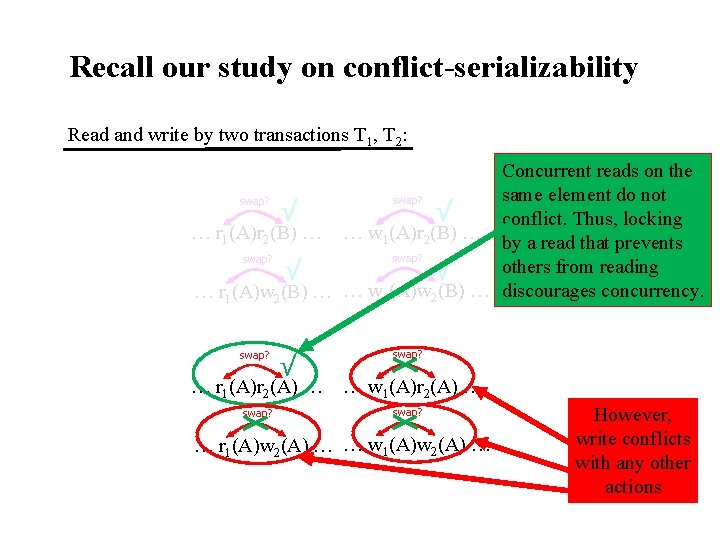

Recall our study on conflict-serializability Read and write by two transactions T 1, T 2: Concurrent reads on the same element do not swap? √ √ conflict. Thus, locking … r 1(A)r 2(B) … … w 1(A)r 2(B) … by a read that prevents swap? others from reading √ √ … r 1(A)w 2(B) … … w 1(A)w 2(B) … discourages concurrency. swap? √ … r 1(A)r 2(A) … swap? … w 1(A)r 2(A) … swap? … r 1(A)w 2(A) … … w 1(A)w 2(A) …

Recall our study on conflict-serializability Read and write by two transactions T 1, T 2: Concurrent reads on the same element do not swap? √ √ conflict. Thus, locking … r 1(A)r 2(B) … … w 1(A)r 2(B) … by a read that prevents swap? others from reading √ √ … r 1(A)w 2(B) … … w 1(A)w 2(B) … discourages concurrency. swap? √ … r 1(A)r 2(A) … swap? … w 1(A)r 2(A) … swap? … r 1(A)w 2(A) … … w 1(A)w 2(A) … However, write conflicts with any other actions

Thus, We may have two different kinds of locks on elements:

Thus, We may have two different kinds of locks on elements: Read-lock (shared-lock slk(A)) by Tk on A: friendly to reads, but block writes Write-lock (exclusive-lock xlk(A)) by Tk on A: block any other actions.

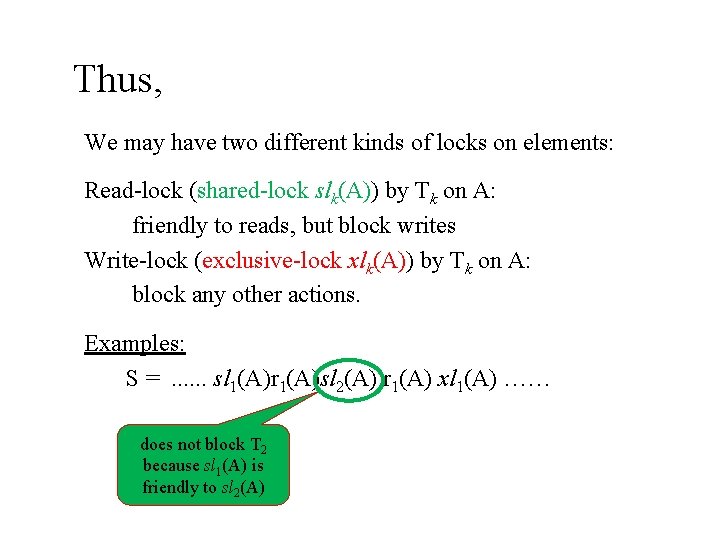

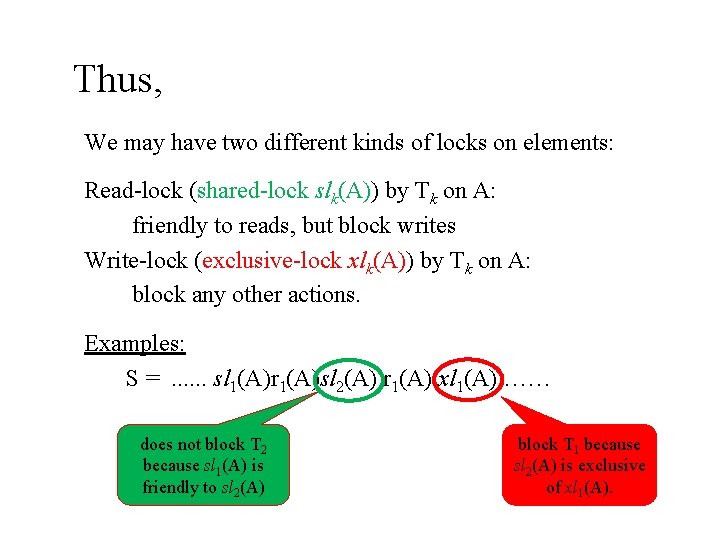

Thus, We may have two different kinds of locks on elements: Read-lock (shared-lock slk(A)) by Tk on A: friendly to reads, but block writes Write-lock (exclusive-lock xlk(A)) by Tk on A: block any other actions. Examples: S =. . . sl 1(A)r 1(A)sl 2(A) r 1(A) xl 1(A) ……

Thus, We may have two different kinds of locks on elements: Read-lock (shared-lock slk(A)) by Tk on A: friendly to reads, but block writes Write-lock (exclusive-lock xlk(A)) by Tk on A: block any other actions. Examples: S =. . . sl 1(A)r 1(A)sl 2(A) r 1(A) xl 1(A) …… does not block T 2 because sl 1(A) is friendly to sl 2(A)

Thus, We may have two different kinds of locks on elements: Read-lock (shared-lock slk(A)) by Tk on A: friendly to reads, but block writes Write-lock (exclusive-lock xlk(A)) by Tk on A: block any other actions. Examples: S =. . . sl 1(A)r 1(A)sl 2(A) r 1(A) xl 1(A) …… does not block T 2 because sl 1(A) is friendly to sl 2(A) block T 1 because sl 2(A) is exclusive of xl 1(A).

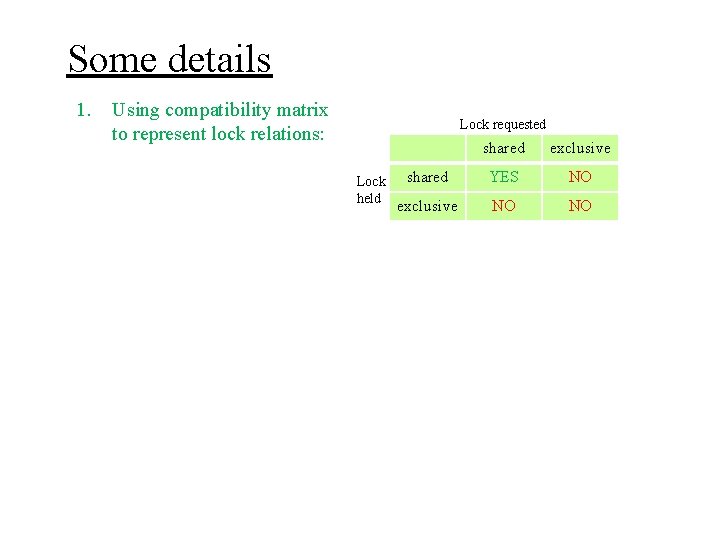

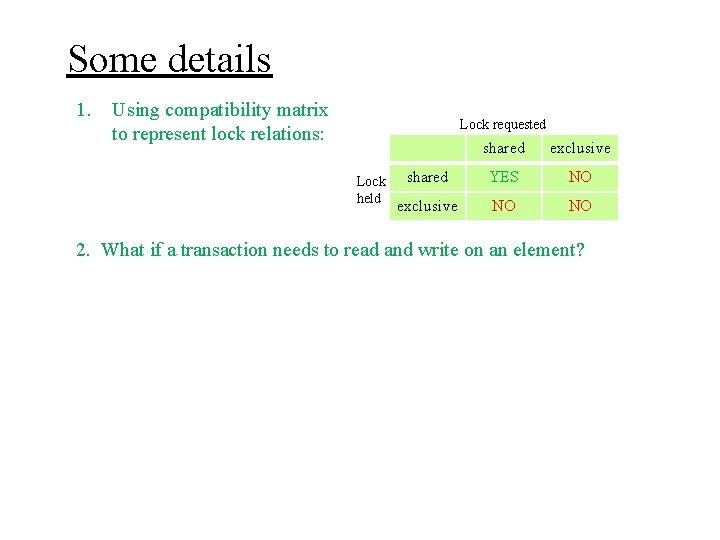

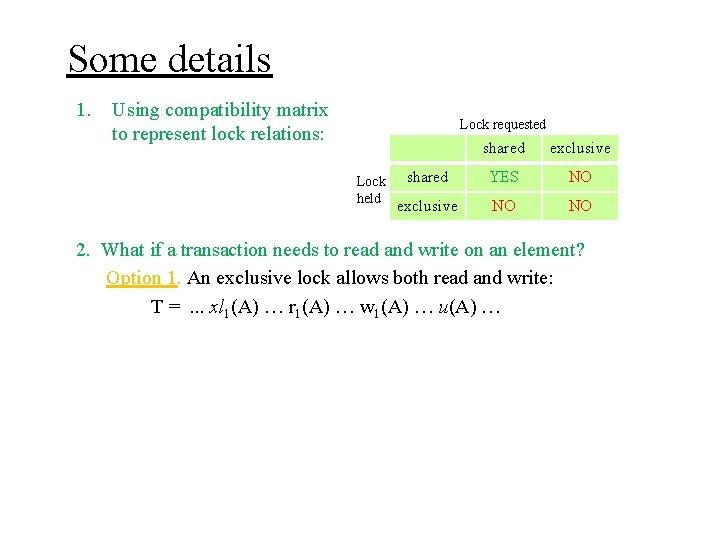

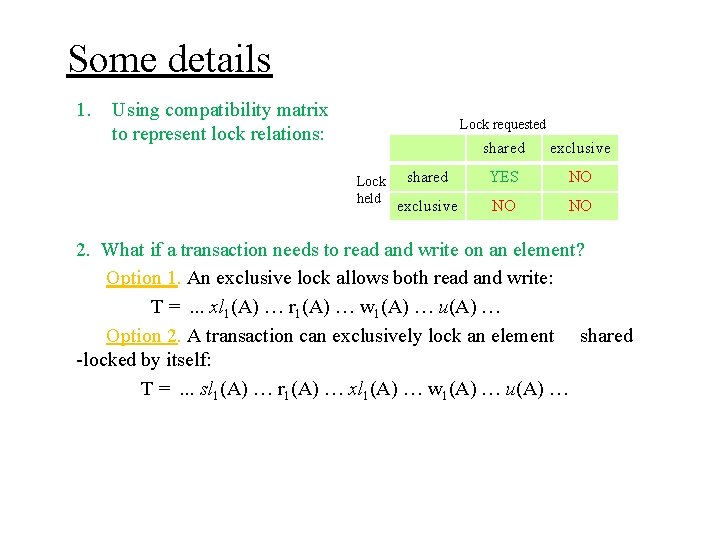

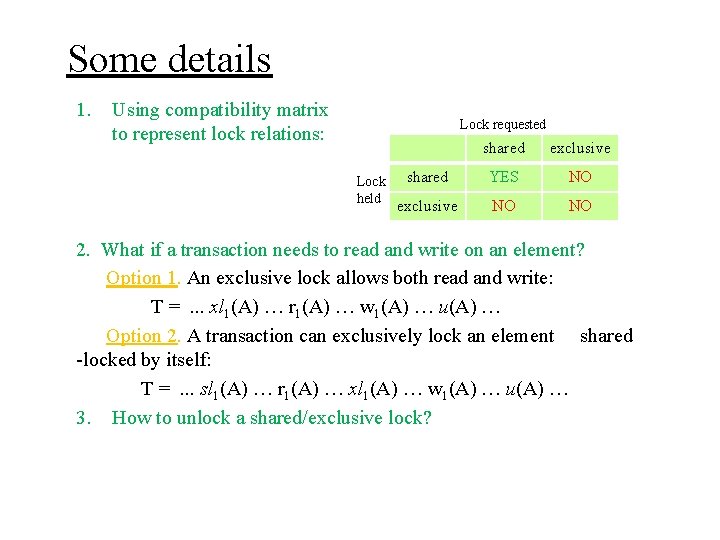

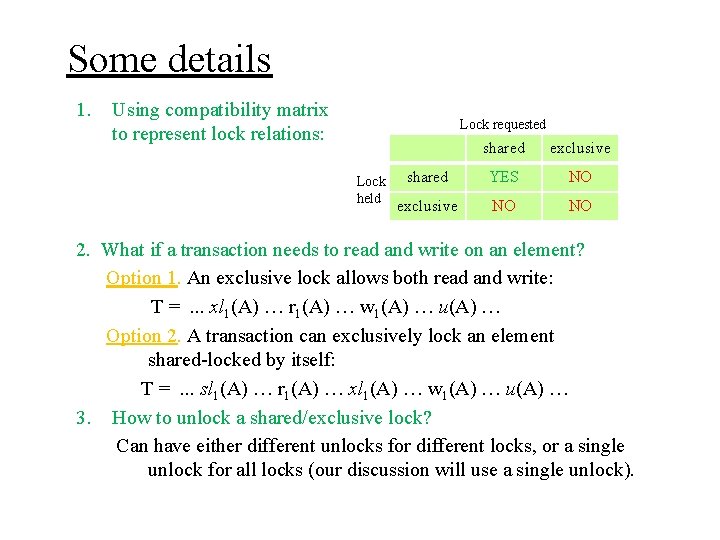

Some details 1. Using compatibility matrix to represent lock relations: Lock requested Lock held shared exclusive shared YES NO exclusive NO NO

Some details 1. Using compatibility matrix to represent lock relations: Lock requested Lock held shared exclusive shared YES NO exclusive NO NO 2. What if a transaction needs to read and write on an element?

Some details 1. Using compatibility matrix to represent lock relations: Lock requested Lock held shared exclusive shared YES NO exclusive NO NO 2. What if a transaction needs to read and write on an element? Option 1. An exclusive lock allows both read and write: T =. . . xl 1(A) … r 1(A) … w 1(A) … u(A) …

Some details 1. Using compatibility matrix to represent lock relations: Lock requested Lock held shared exclusive shared YES NO exclusive NO NO 2. What if a transaction needs to read and write on an element? Option 1. An exclusive lock allows both read and write: T =. . . xl 1(A) … r 1(A) … w 1(A) … u(A) … Option 2. A transaction can exclusively lock an element shared -locked by itself: T =. . . sl 1(A) … r 1(A) … xl 1(A) … w 1(A) … u(A) …

Some details 1. Using compatibility matrix to represent lock relations: Lock requested Lock held shared exclusive shared YES NO exclusive NO NO 2. What if a transaction needs to read and write on an element? Option 1. An exclusive lock allows both read and write: T =. . . xl 1(A) … r 1(A) … w 1(A) … u(A) … Option 2. A transaction can exclusively lock an element shared -locked by itself: T =. . . sl 1(A) … r 1(A) … xl 1(A) … w 1(A) … u(A) … 3. How to unlock a shared/exclusive lock?

Some details 1. Using compatibility matrix to represent lock relations: Lock requested Lock held shared exclusive shared YES NO exclusive NO NO 2. What if a transaction needs to read and write on an element? Option 1. An exclusive lock allows both read and write: T =. . . xl 1(A) … r 1(A) … w 1(A) … u(A) … Option 2. A transaction can exclusively lock an element shared-locked by itself: T =. . . sl 1(A) … r 1(A) … xl 1(A) … w 1(A) … u(A) … 3. How to unlock a shared/exclusive lock? Can have either different unlocks for different locks, or a single unlock for all locks (our discussion will use a single unlock).

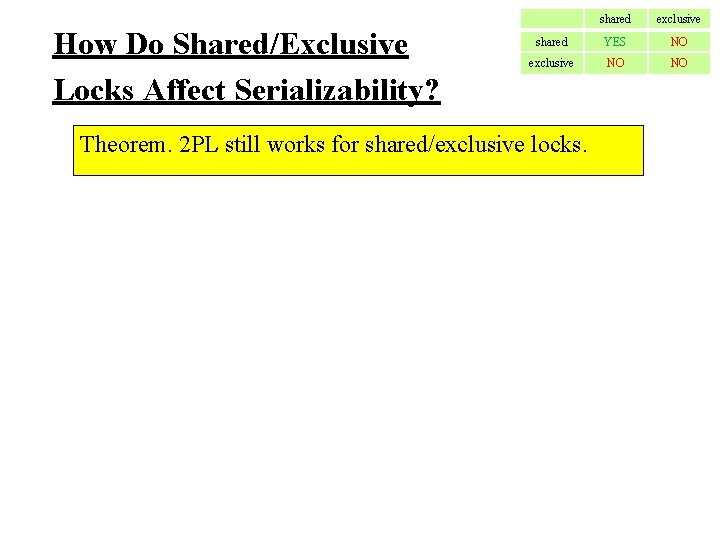

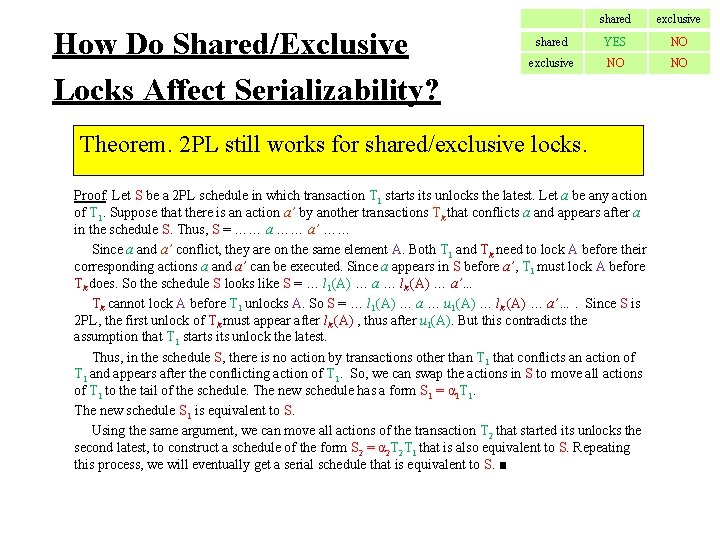

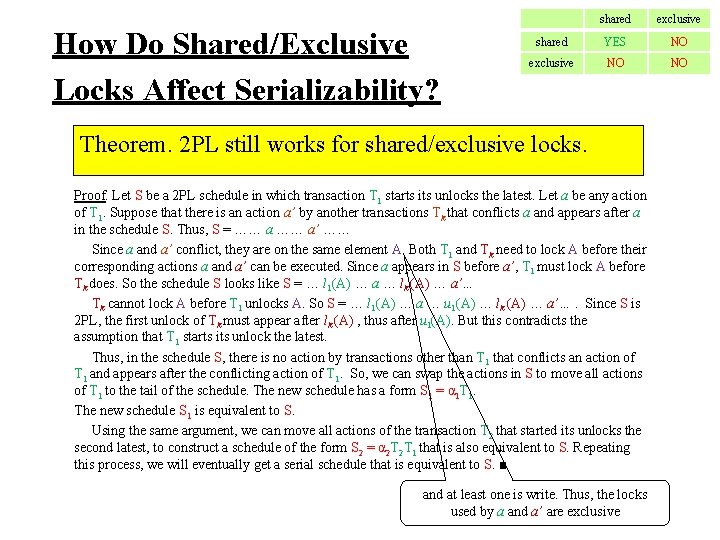

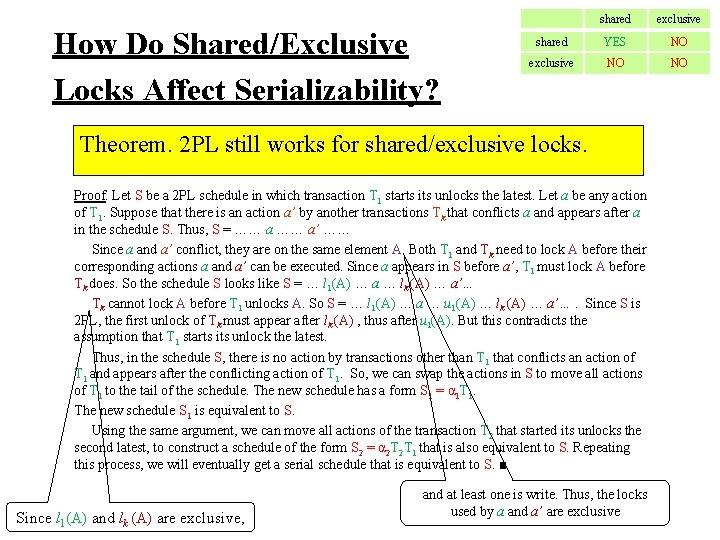

How Do Shared/Exclusive Locks Affect Serializability? shared exclusive shared YES NO exclusive NO NO Theorem. 2 PL still works for shared/exclusive locks.

How Do Shared/Exclusive Locks Affect Serializability? shared exclusive shared YES NO exclusive NO NO Theorem. 2 PL still works for shared/exclusive locks. Proof. Let S be a 2 PL schedule in which transaction T 1 starts its unlocks the latest. Let a be any action of T 1. Suppose that there is an action a’ by another transactions Tk that conflicts a and appears after a in the schedule S. Thus, S = …… a’ …… Since a and a’ conflict, they are on the same element A. Both T 1 and Tk need to lock A before their corresponding actions a and a’ can be executed. Since a appears in S before a’, T 1 must lock A before Tk does. So the schedule S looks like S = … l 1(A) … a … lk (A) … a’… Tk cannot lock A before T 1 unlocks A. So S = … l 1(A) … a … u 1(A) … lk (A) … a’…. Since S is 2 PL, the first unlock of Tk must appear after lk (A) , thus after u 1(A). But this contradicts the assumption that T 1 starts its unlock the latest. Thus, in the schedule S, there is no action by transactions other than T 1 that conflicts an action of T 1 and appears after the conflicting action of T 1. So, we can swap the actions in S to move all actions of T 1 to the tail of the schedule. The new schedule has a form S 1 = α 1 T 1. The new schedule S 1 is equivalent to S. Using the same argument, we can move all actions of the transaction T 2 that started its unlocks the second latest, to construct a schedule of the form S 2 = α 2 T 2 T 1 that is also equivalent to S. Repeating this process, we will eventually get a serial schedule that is equivalent to S. ■

How Do Shared/Exclusive Locks Affect Serializability? shared exclusive shared YES NO exclusive NO NO Theorem. 2 PL still works for shared/exclusive locks. Proof. Let S be a 2 PL schedule in which transaction T 1 starts its unlocks the latest. Let a be any action of T 1. Suppose that there is an action a’ by another transactions Tk that conflicts a and appears after a in the schedule S. Thus, S = …… a’ …… Since a and a’ conflict, they are on the same element A. Both T 1 and Tk need to lock A before their corresponding actions a and a’ can be executed. Since a appears in S before a’, T 1 must lock A before Tk does. So the schedule S looks like S = … l 1(A) … a … lk (A) … a’… Tk cannot lock A before T 1 unlocks A. So S = … l 1(A) … a … u 1(A) … lk (A) … a’…. Since S is 2 PL, the first unlock of Tk must appear after lk (A) , thus after u 1(A). But this contradicts the assumption that T 1 starts its unlock the latest. Thus, in the schedule S, there is no action by transactions other than T 1 that conflicts an action of T 1 and appears after the conflicting action of T 1. So, we can swap the actions in S to move all actions of T 1 to the tail of the schedule. The new schedule has a form S 1 = α 1 T 1. The new schedule S 1 is equivalent to S. Using the same argument, we can move all actions of the transaction T 2 that started its unlocks the second latest, to construct a schedule of the form S 2 = α 2 T 2 T 1 that is also equivalent to S. Repeating this process, we will eventually get a serial schedule that is equivalent to S. ■ and at least one is write. Thus, the locks used by a and a’ are exclusive

How Do Shared/Exclusive Locks Affect Serializability? shared exclusive shared YES NO exclusive NO NO Theorem. 2 PL still works for shared/exclusive locks. Proof. Let S be a 2 PL schedule in which transaction T 1 starts its unlocks the latest. Let a be any action of T 1. Suppose that there is an action a’ by another transactions Tk that conflicts a and appears after a in the schedule S. Thus, S = …… a’ …… Since a and a’ conflict, they are on the same element A. Both T 1 and Tk need to lock A before their corresponding actions a and a’ can be executed. Since a appears in S before a’, T 1 must lock A before Tk does. So the schedule S looks like S = … l 1(A) … a … lk (A) … a’… Tk cannot lock A before T 1 unlocks A. So S = … l 1(A) … a … u 1(A) … lk (A) … a’…. Since S is 2 PL, the first unlock of Tk must appear after lk (A) , thus after u 1(A). But this contradicts the assumption that T 1 starts its unlock the latest. Thus, in the schedule S, there is no action by transactions other than T 1 that conflicts an action of T 1 and appears after the conflicting action of T 1. So, we can swap the actions in S to move all actions of T 1 to the tail of the schedule. The new schedule has a form S 1 = α 1 T 1. The new schedule S 1 is equivalent to S. Using the same argument, we can move all actions of the transaction T 2 that started its unlocks the second latest, to construct a schedule of the form S 2 = α 2 T 2 T 1 that is also equivalent to S. Repeating this process, we will eventually get a serial schedule that is equivalent to S. ■ Since l 1(A) and lk (A) are exclusive, and at least one is write. Thus, the locks used by a and a’ are exclusive

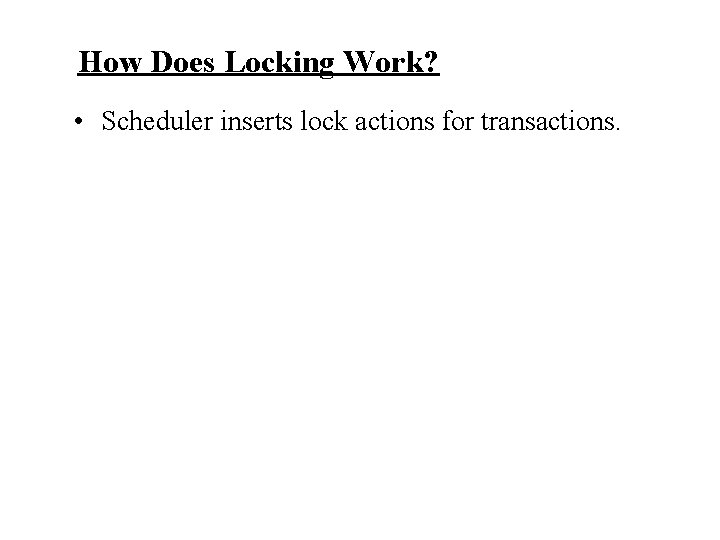

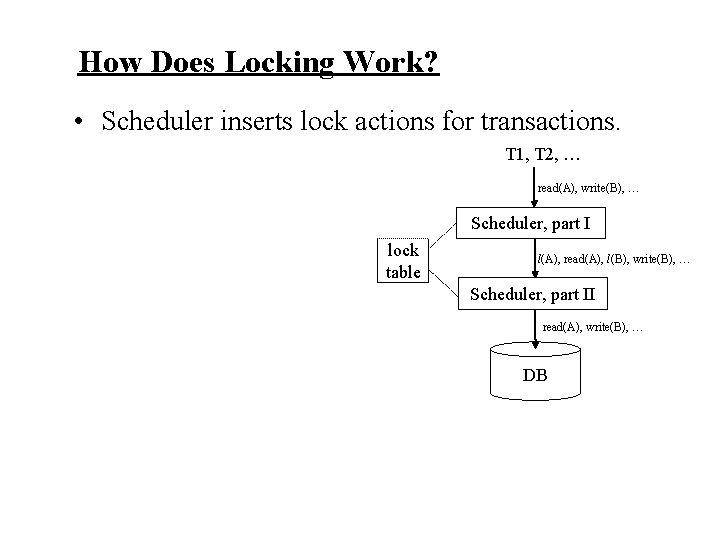

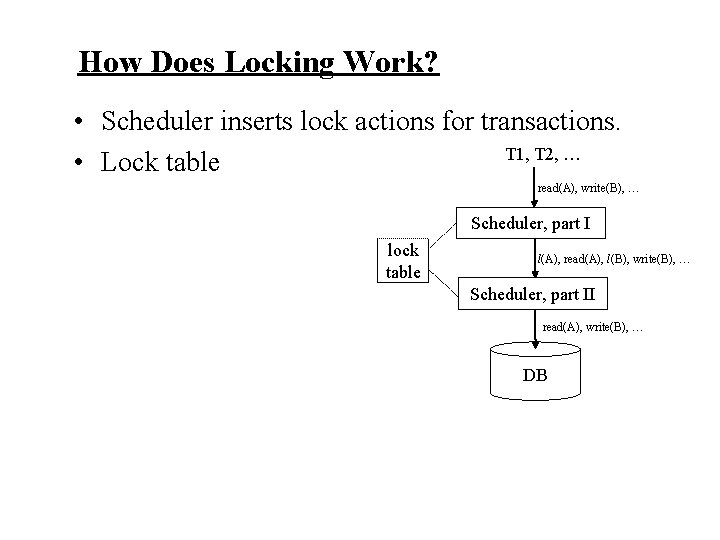

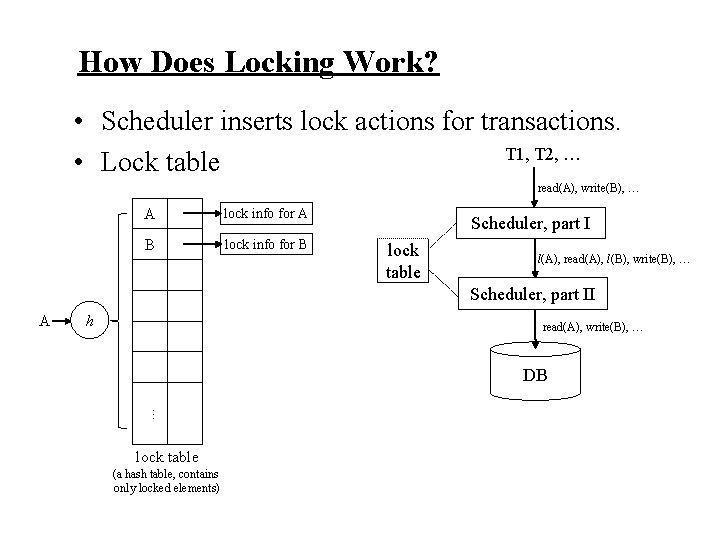

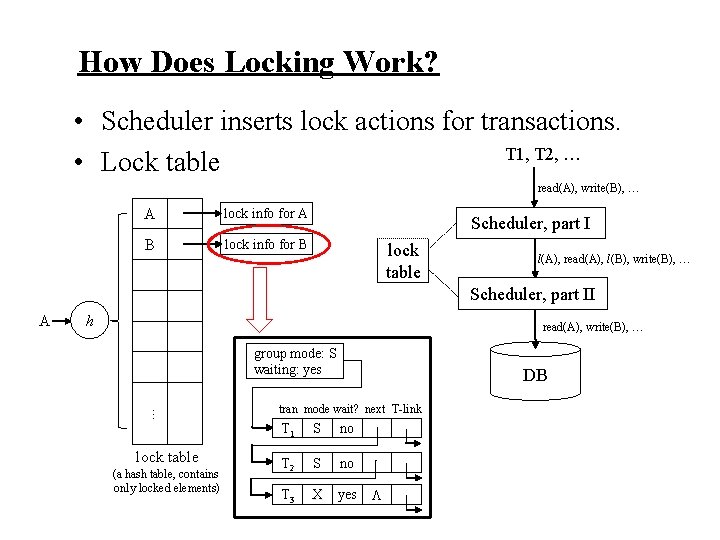

How Does Locking Work?

How Does Locking Work? • Scheduler inserts lock actions for transactions.

How Does Locking Work? • Scheduler inserts lock actions for transactions. T 1, T 2, … read(A), write(B), … Scheduler, part I lock table l(A), read(A), l(B), write(B), … Scheduler, part II read(A), write(B), … DB

How Does Locking Work? • Scheduler inserts lock actions for transactions. T 1, T 2, … • Lock table read(A), write(B), … Scheduler, part I lock table l(A), read(A), l(B), write(B), … Scheduler, part II read(A), write(B), … DB

How Does Locking Work? • Scheduler inserts lock actions for transactions. T 1, T 2, … • Lock table read(A), write(B), … A lock info for A B lock info for B Scheduler, part I lock table l(A), read(A), l(B), write(B), … Scheduler, part II A h read(A), write(B), … DB. . . lock table (a hash table, contains only locked elements)

How Does Locking Work? • Scheduler inserts lock actions for transactions. T 1, T 2, … • Lock table read(A), write(B), … A lock info for A B lock info for B Scheduler, part I lock table l(A), read(A), l(B), write(B), … Scheduler, part II A h read(A), write(B), … group mode: S waiting: yes . . . lock table (a hash table, contains only locked elements) DB tran mode wait? next T-link T 1 S no T 2 S no T 3 X yes

- Slides: 80