CS 444CS 544 Operating Systems Introduction to Synchronization

- Slides: 20

CS 444/CS 544 Operating Systems Introduction to Synchronization 2/07/2007 Prof. Searleman jets@clarkson. edu

CS 444/CS 544 l l Spring 2007 CPU Scheduling Synchronization l l Need for synchronization primitives Locks and building locks from HW primitives Reading assignment: l Chapter 6 HW#4 posted, due: 2 -7 -2007 Exam#1: Thurs. Feb. 15 th, 7: 00 pm, Snell 213

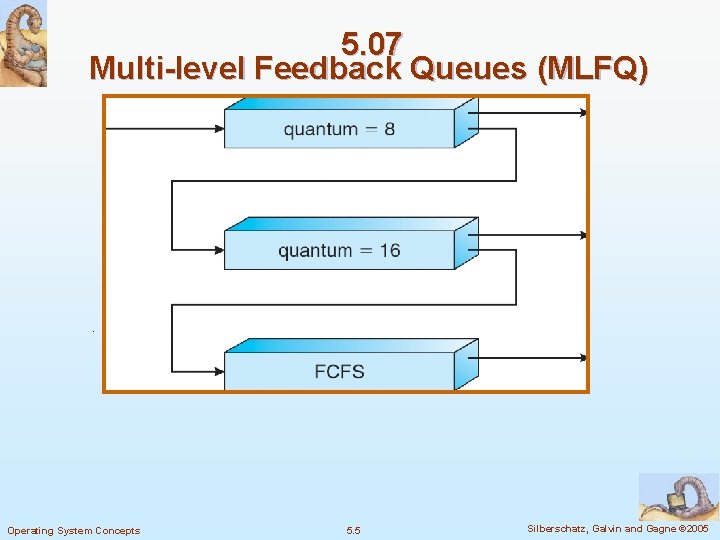

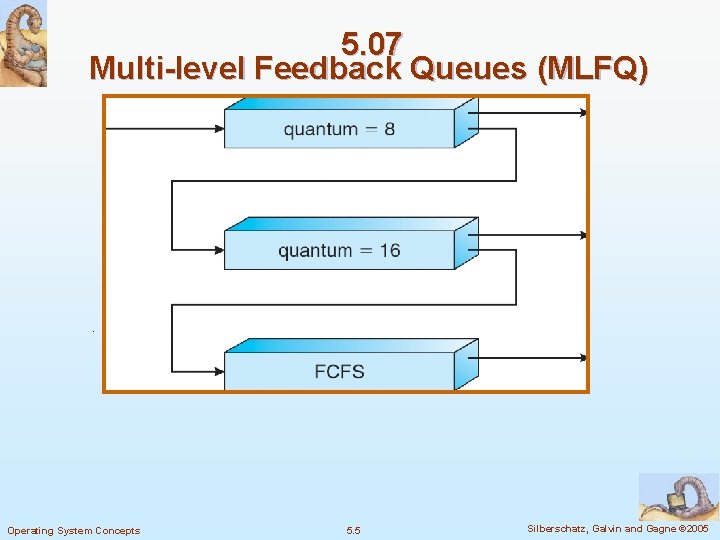

Multi-level Feedback Queues (MLFQ) l Multiple queues representing different types of jobs l l Example: I/O bound, CPU bound Queues have different priorities Jobs can move between queues based on execution history If any job can be guaranteed to eventually reach the top priority queue given enough waiting time, then MLFQ is starvation free

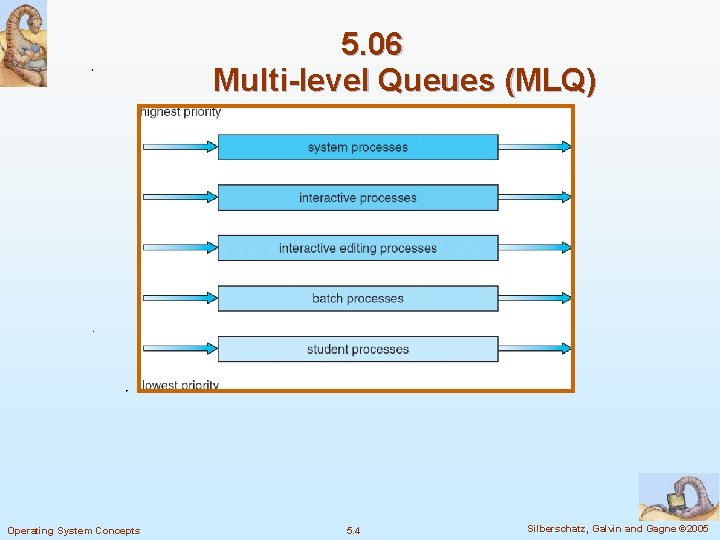

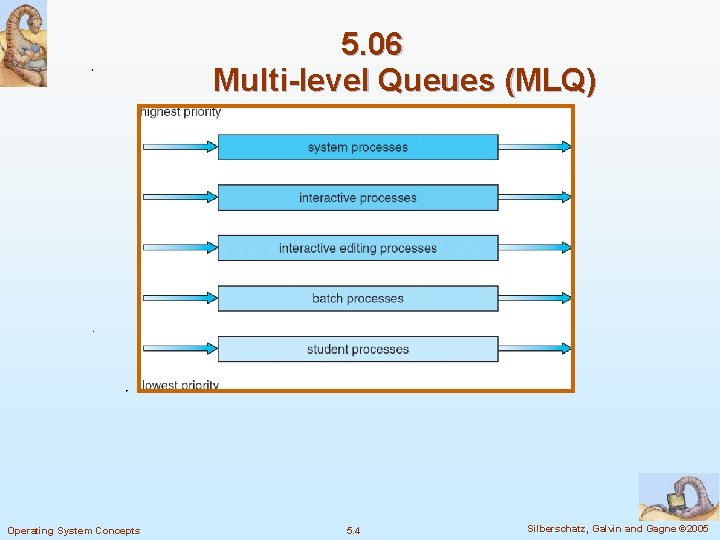

5. 06 Multi-level Queues (MLQ) Operating System Concepts 5. 4 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

5. 07 Multi-level Feedback Queues (MLFQ) Operating System Concepts 5. 5 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne © 2005

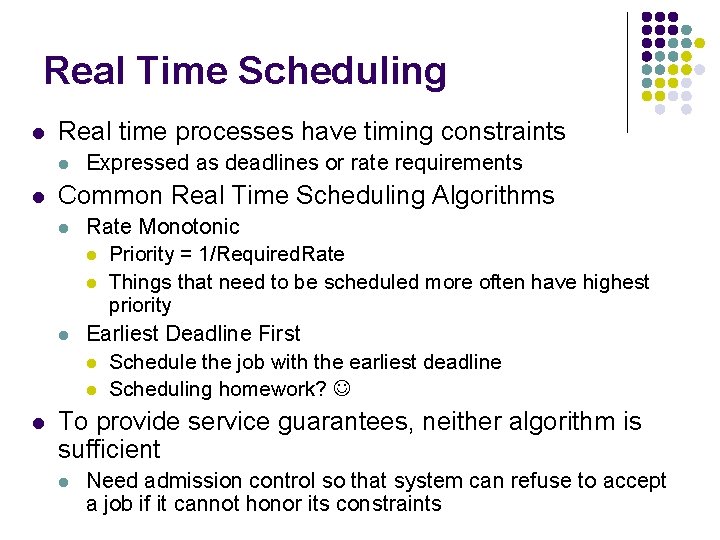

Real Time Scheduling l Real time processes have timing constraints l l Common Real Time Scheduling Algorithms l l l Expressed as deadlines or rate requirements Rate Monotonic l Priority = 1/Required. Rate l Things that need to be scheduled more often have highest priority Earliest Deadline First l Schedule the job with the earliest deadline l Scheduling homework? To provide service guarantees, neither algorithm is sufficient l Need admission control so that system can refuse to accept a job if it cannot honor its constraints

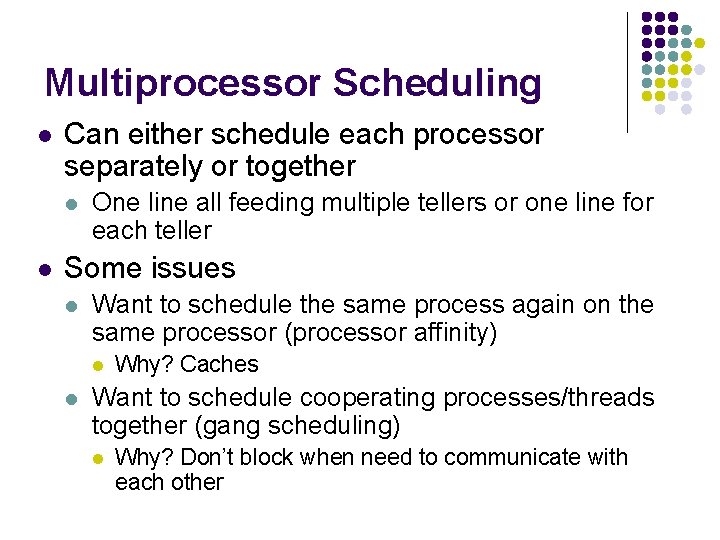

Multiprocessor Scheduling l Can either schedule each processor separately or together l l One line all feeding multiple tellers or one line for each teller Some issues l Want to schedule the same process again on the same processor (processor affinity) l l Why? Caches Want to schedule cooperating processes/threads together (gang scheduling) l Why? Don’t block when need to communicate with each other

Algorithm Evaluation: Deterministic Modeling l l Specifies algorithm *and* workload Example : l l Process 1 arrives at time 1 and has a running time of 10 and a priority of 2 Process 2 arrives at time 5, has a running time of 2 and a priority of 1 … What is the average waiting time if we use preemptive priority scheduling with FIFO among processes of the same priority?

Algorithm Evaluation: Queueing Models l l l Distribution of CPU and I/O bursts, arrival times, service times are all modeled as a probability distribution Mathematical analysis of these systems To make analysis tractable, model as well behaved but unrealistic distributions

Algorithm Evaluation: Simulation l l Implement a scheduler as a user process Drive scheduler with a workload that is either l l l randomly chosen according to some distribution measured on a real system and replayed Simulations can be just as complex as actual implementations l l At some level of effort, should just implement in real system and test with “real” workloads What is your benchmark/ common case?

Synchronization

Concurrency is a good thing l So far we have mostly been talking about constructs to enable concurrency l l l Concurrency critical to using the hardware devices to full capacity l l Multiple processes, inter-process communication Multiple threads in a process Always something that needs to be running on the CPU, using each device, etc. We don’t want to restrict concurrency unless we absolutely have to

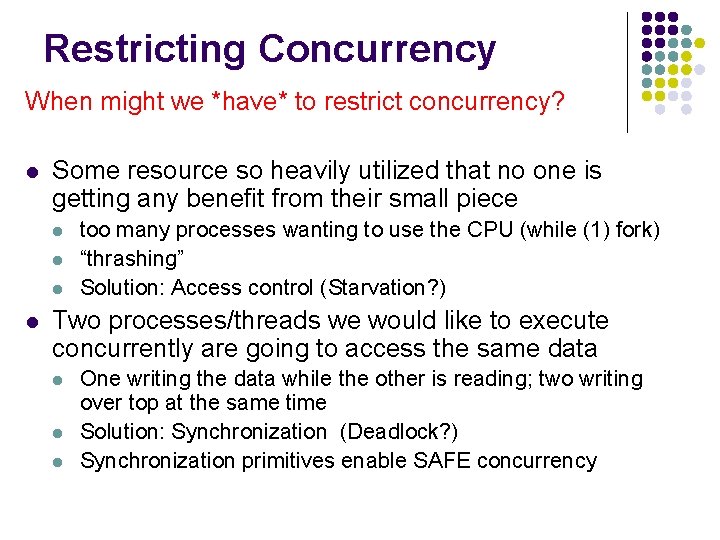

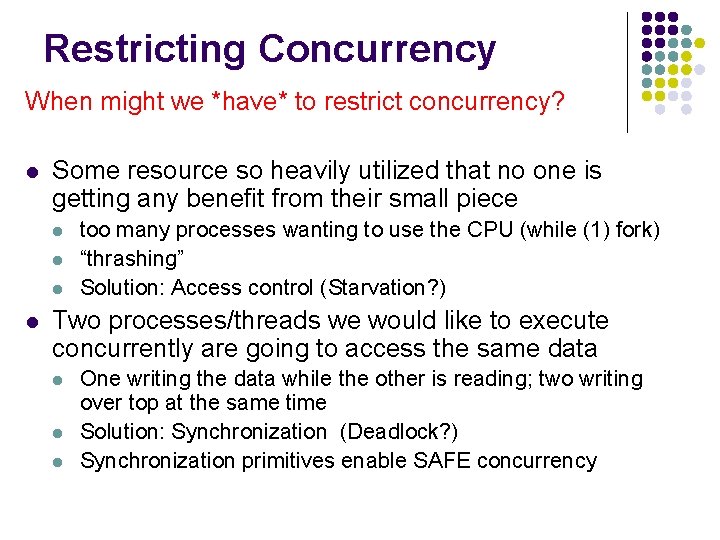

Restricting Concurrency When might we *have* to restrict concurrency? l Some resource so heavily utilized that no one is getting any benefit from their small piece l l too many processes wanting to use the CPU (while (1) fork) “thrashing” Solution: Access control (Starvation? ) Two processes/threads we would like to execute concurrently are going to access the same data l l l One writing the data while the other is reading; two writing over top at the same time Solution: Synchronization (Deadlock? ) Synchronization primitives enable SAFE concurrency

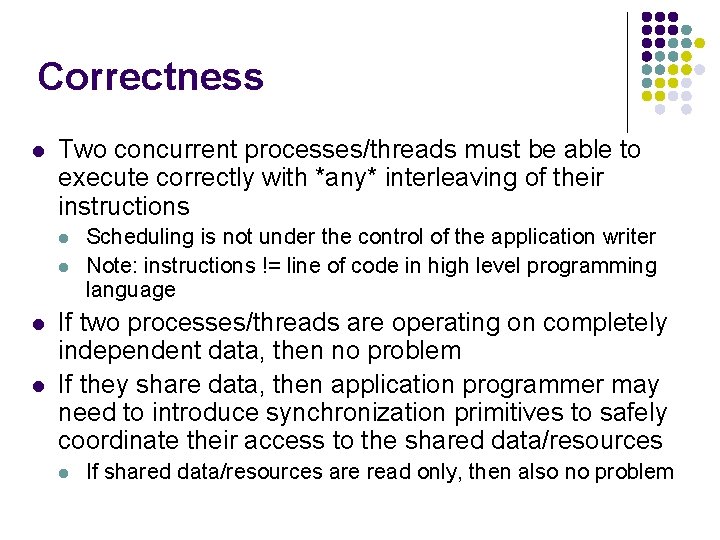

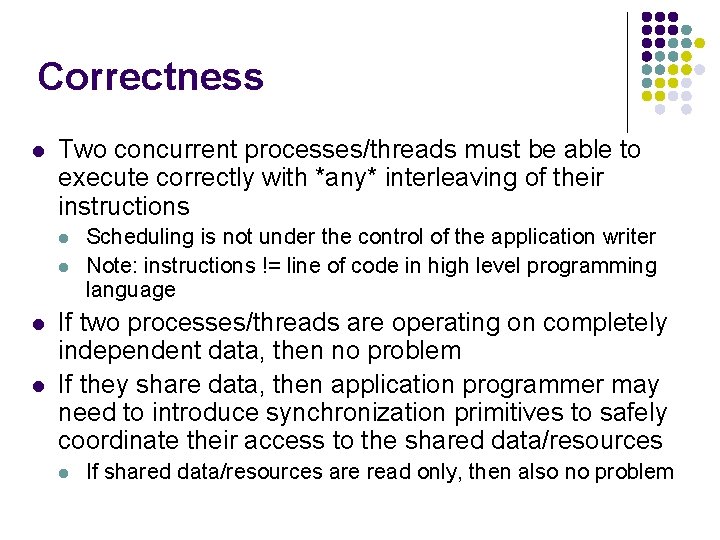

Correctness l Two concurrent processes/threads must be able to execute correctly with *any* interleaving of their instructions l l Scheduling is not under the control of the application writer Note: instructions != line of code in high level programming language If two processes/threads are operating on completely independent data, then no problem If they share data, then application programmer may need to introduce synchronization primitives to safely coordinate their access to the shared data/resources l If shared data/resources are read only, then also no problem

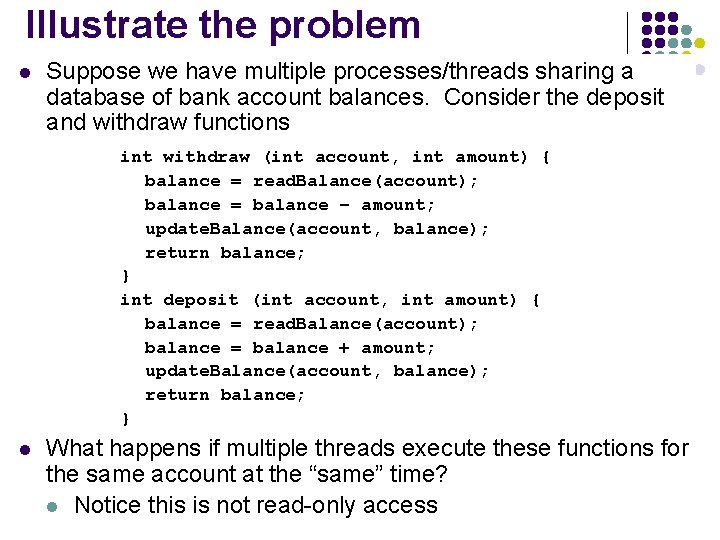

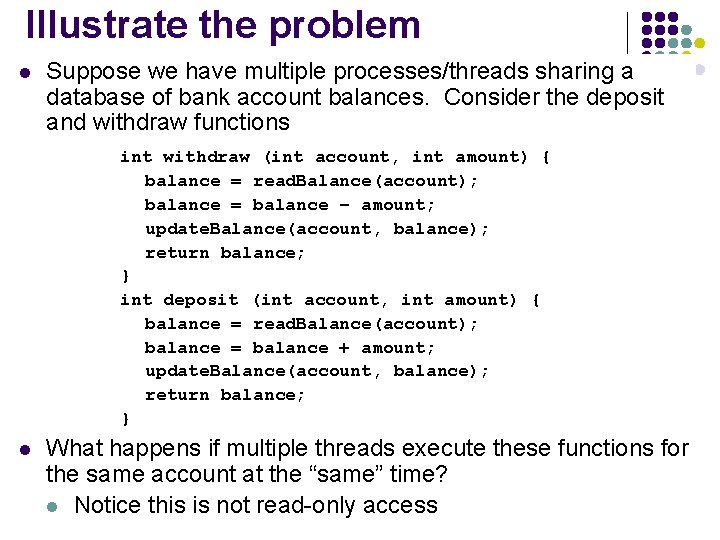

Illustrate the problem l Suppose we have multiple processes/threads sharing a database of bank account balances. Consider the deposit and withdraw functions int withdraw (int account, int amount) { balance = read. Balance(account); balance = balance – amount; update. Balance(account, balance); return balance; } int deposit (int account, int amount) { balance = read. Balance(account); balance = balance + amount; update. Balance(account, balance); return balance; } l What happens if multiple threads execute these functions for the same account at the “same” time? l Notice this is not read-only access

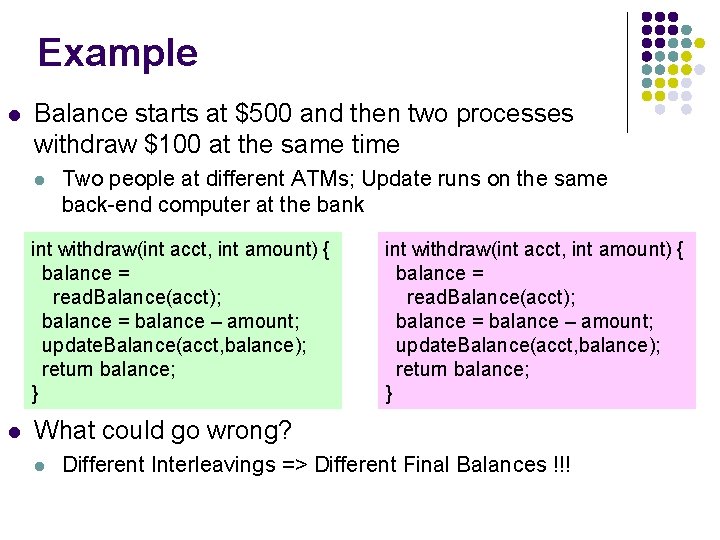

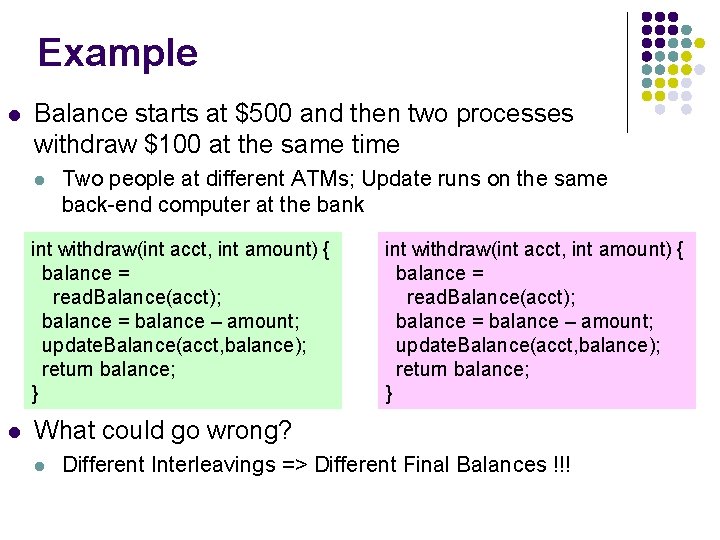

Example l Balance starts at $500 and then two processes withdraw $100 at the same time l Two people at different ATMs; Update runs on the same back-end computer at the bank int withdraw(int acct, int amount) { balance = read. Balance(acct); balance = balance – amount; update. Balance(acct, balance); return balance; } l int withdraw(int acct, int amount) { balance = read. Balance(acct); balance = balance – amount; update. Balance(acct, balance); return balance; } What could go wrong? l Different Interleavings => Different Final Balances !!!

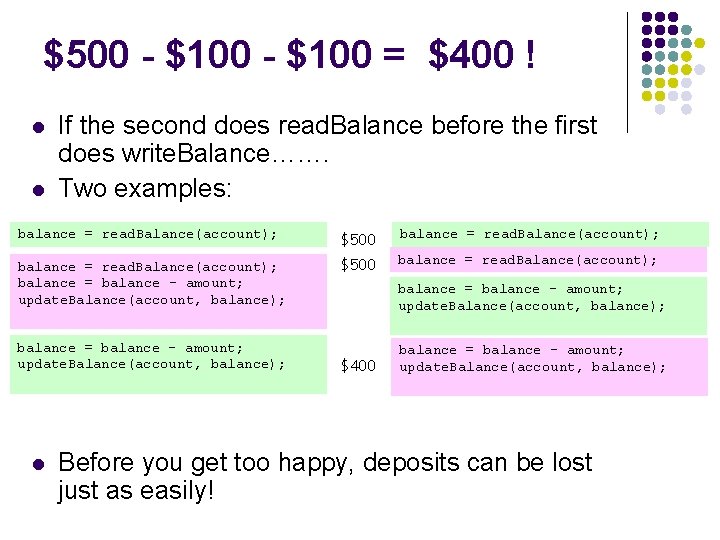

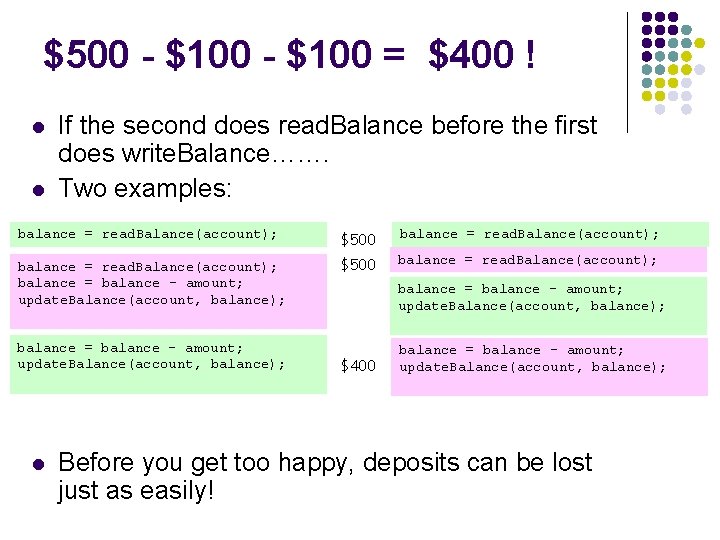

$500 - $100 = $400 ! l l If the second does read. Balance before the first does write. Balance……. Two examples: balance = read. Balance(account); $500 balance = read. Balance(account); balance = balance - amount; update. Balance(account, balance); $500 balance = read. Balance(account); balance = balance - amount; update. Balance(account, balance); l balance = balance - amount; update. Balance(account, balance); $400 balance = balance - amount; update. Balance(account, balance); Before you get too happy, deposits can be lost just as easily!

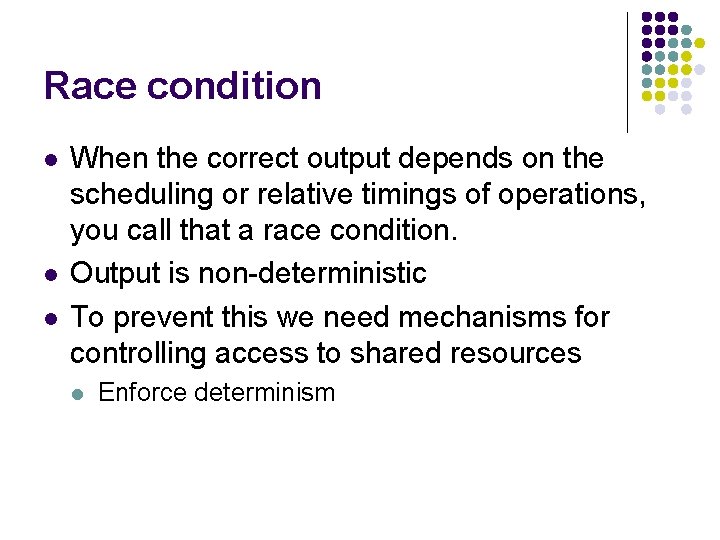

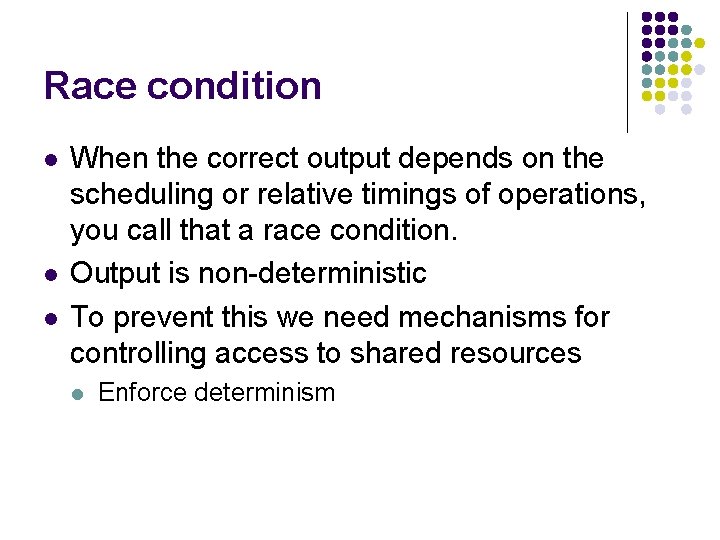

Race condition l l l When the correct output depends on the scheduling or relative timings of operations, you call that a race condition. Output is non-deterministic To prevent this we need mechanisms for controlling access to shared resources l Enforce determinism

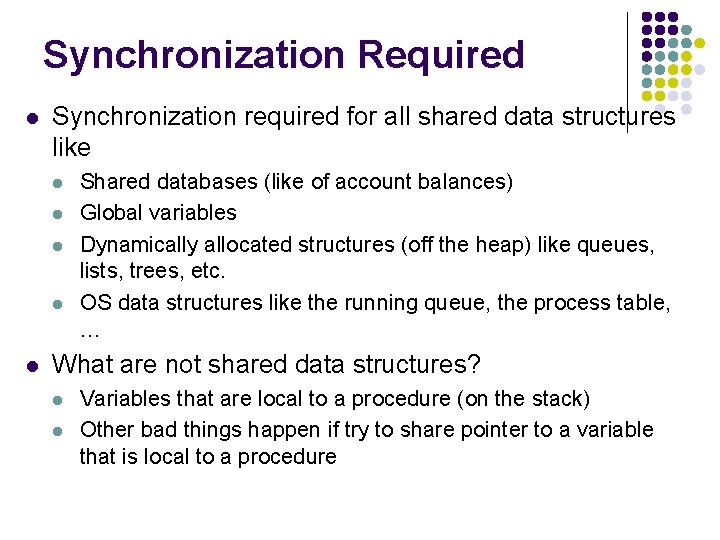

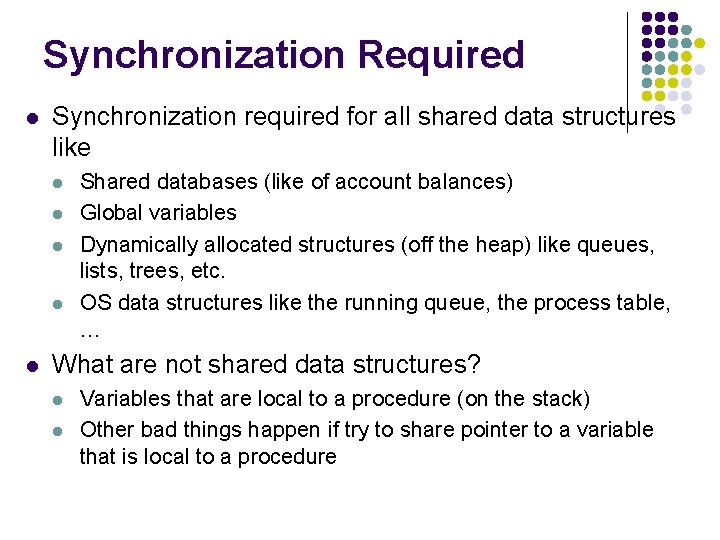

Synchronization Required l Synchronization required for all shared data structures like l l l Shared databases (like of account balances) Global variables Dynamically allocated structures (off the heap) like queues, lists, trees, etc. OS data structures like the running queue, the process table, … What are not shared data structures? l l Variables that are local to a procedure (on the stack) Other bad things happen if try to share pointer to a variable that is local to a procedure

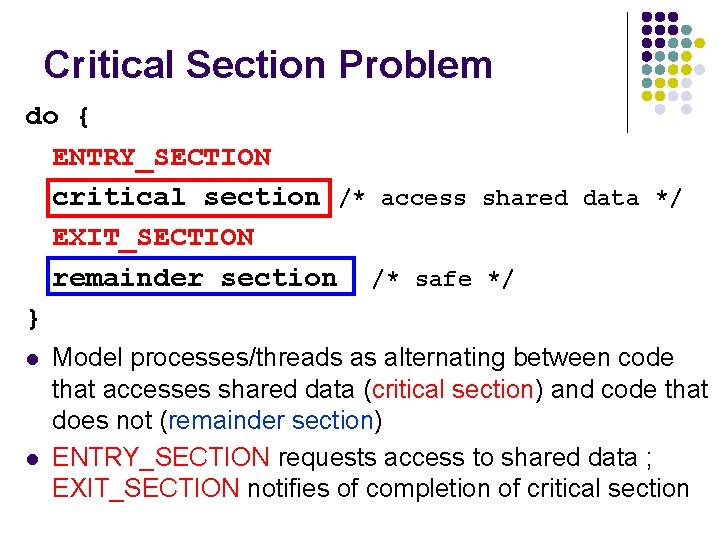

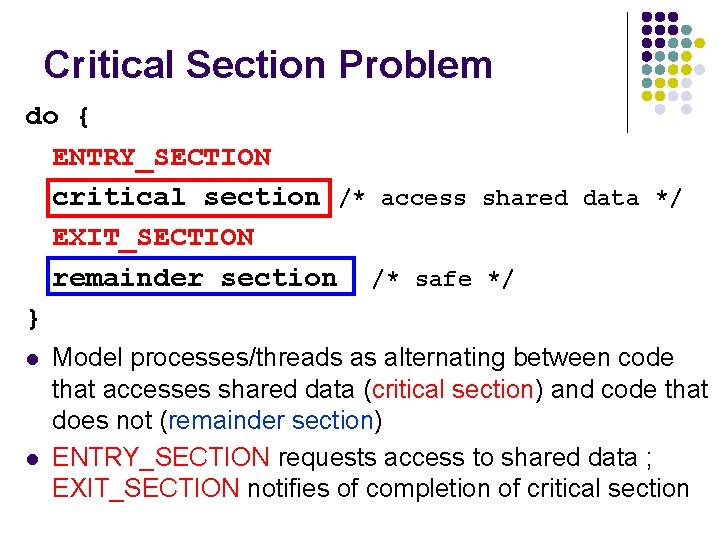

Critical Section Problem do { ENTRY_SECTION critical section /* access shared data */ EXIT_SECTION remainder section /* safe */ } l l Model processes/threads as alternating between code that accesses shared data (critical section) and code that does not (remainder section) ENTRY_SECTION requests access to shared data ; EXIT_SECTION notifies of completion of critical section