CS 3204 Operating Systems Lecture 12 Godmar Back

CS 3204 Operating Systems Lecture 12 Godmar Back CS 3204 Fall 2006

Announcements • Project 2 due Tuesday Oct 17, 11: 59 pm – 2 -people groups please send me email – Decide on groups • 2 nd Help Session tonight in Mc. B 126 • Midterm Oct 12 • Reading assignment: – Read Chapter 5 (best to read all of it – should be easy read after doing Project 1) CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 2

Plan of Attack • Multiprogramming Basics (today) • Sep 28 Thursday: Scheduling part 1 • Oct 3 Tuesday: (out of town) Guest lecture on real-time scheduling • Oct 5 Thursday + Oct 10 Tuesday: – Wrap-up Scheduling, Monitors, & Deadlock • Oct 10 Tuesday: – Deadlock • Oct 12: (out of town) Midterm CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 3

Scheduling CS 3204 Fall 2006

Resource Allocation & Scheduling • Resource management is primary OS function • Involves resource allocation & scheduling – Who gets to use what resource and for how long • Example resources: – – – CPU time Disk bandwidth Network bandwidth RAM Disk space • Processes are the principals that use resources – often on behalf of users CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 5

CPU vs. Other Resources • CPU is not the only resource that needs to be scheduled • Overall system performance depends on efficient use of all resources – Resource can be in use (busy) or be unused (idle) • Duty cycle: portion of time busy – Consider I/O device: busy after receiving I/O request – if CPU scheduler delays process that will issue I/O request, I/O device is underutilized • Ideal: want to keep all devices busy CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 6

Preemptible vs Nonpreemptible Resources • Nonpreemptible resources: – Once allocated, can’t easily ask for them back – must wait until process returns them (or exits) • Examples: Locks, Disk Space, Control of terminal • Preemptible resources: – Can be taken away (“preempted”) and returned without the process noticing it • Examples: CPU, Memory CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 7

Physical vs Virtual Memory • Classification of a resource as preemptible depends on price one is willing to pay to preempt it – Can theoretically preempt most resources via copying & indirection • Virtual Memory: mechanism to make physical memory preemptible – Take away by swapping to disk, return by reading from disk (possibly swapping out others) • Not always tolerable – resident portions of kernel – Pintos kernel stack pages CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 8

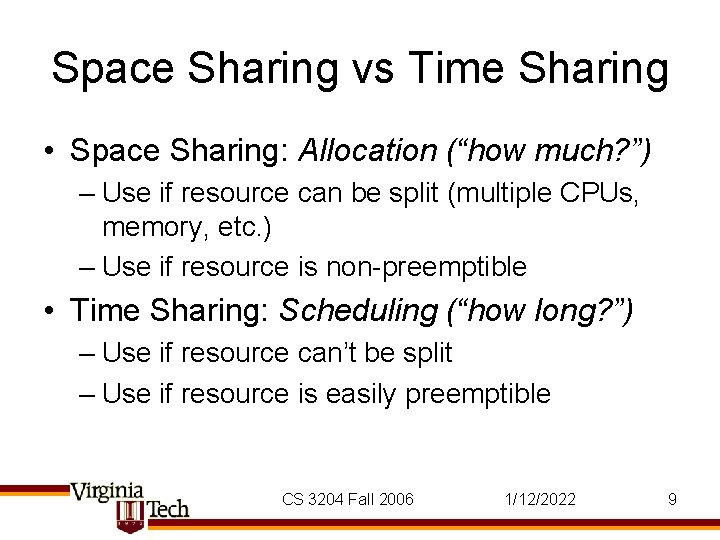

Space Sharing vs Time Sharing • Space Sharing: Allocation (“how much? ”) – Use if resource can be split (multiple CPUs, memory, etc. ) – Use if resource is non-preemptible • Time Sharing: Scheduling (“how long? ”) – Use if resource can’t be split – Use if resource is easily preemptible CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 9

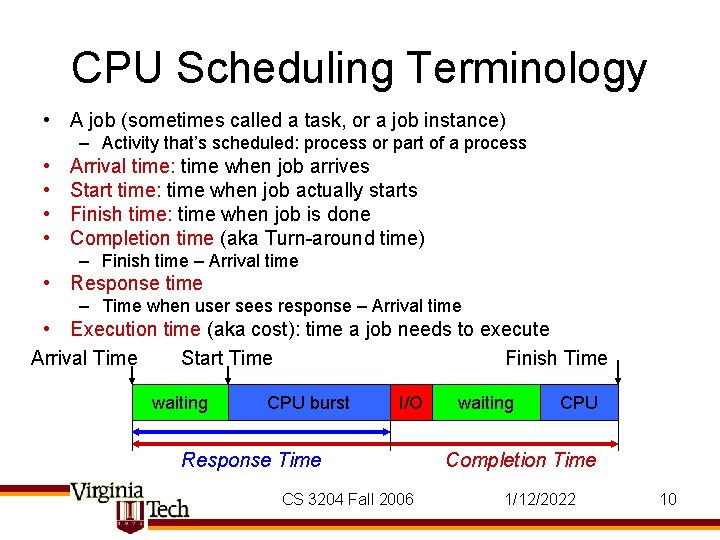

CPU Scheduling Terminology • A job (sometimes called a task, or a job instance) – Activity that’s scheduled: process or part of a process • • Arrival time: time when job arrives Start time: time when job actually starts Finish time: time when job is done Completion time (aka Turn-around time) – Finish time – Arrival time • Response time – Time when user sees response – Arrival time • Execution time (aka cost): time a job needs to execute Arrival Time Start Time Finish Time waiting CPU burst I/O Response Time CS 3204 Fall 2006 waiting CPU Completion Time 1/12/2022 10

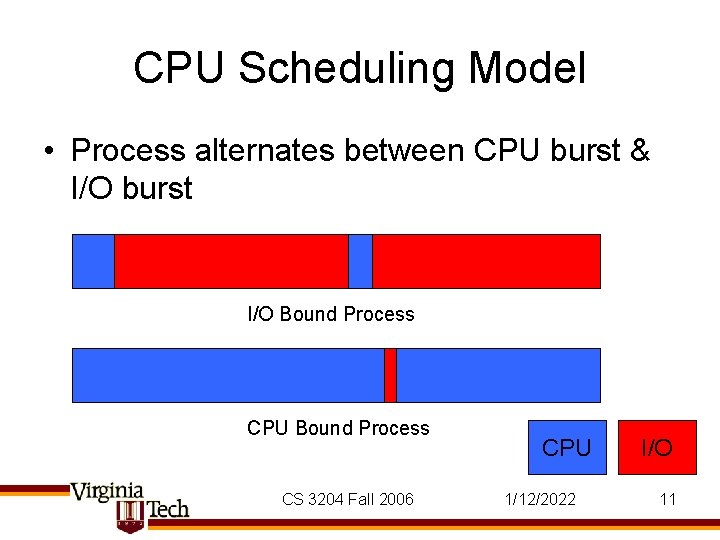

CPU Scheduling Model • Process alternates between CPU burst & I/O burst I/O Bound Process CPU Bound Process CS 3204 Fall 2006 CPU 1/12/2022 I/O 11

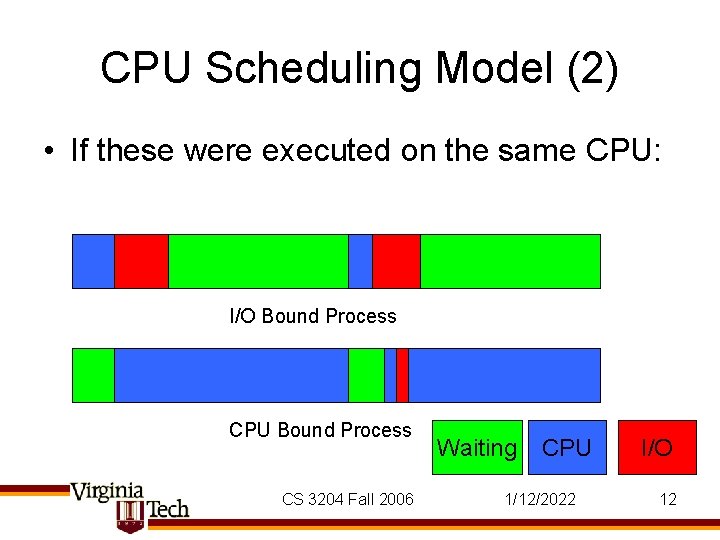

CPU Scheduling Model (2) • If these were executed on the same CPU: I/O Bound Process CPU Bound Process CS 3204 Fall 2006 Waiting CPU 1/12/2022 I/O 12

CPU Scheduling Terminology (2) • Waiting time = time when job was ready-to -run – didn’t run because CPU scheduler picked another job • Blocked time = time when job was blocked – while I/O device is in use • Completion time – Execution time + Waiting time + Blocked time CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 13

Static vs Dynamic Scheduling • Static – All jobs, their arrival & execution times are known in advance, create a schedule, execute it • Used in statically configured systems, such as embedded real-time systems • Dynamic or Online Scheduling – Jobs are not known in advance, scheduler must make online decision whenever jobs arrives or leaves • Execution time may or may not be known • Behavior can be modeled by making assumptions about nature of arrival process CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 14

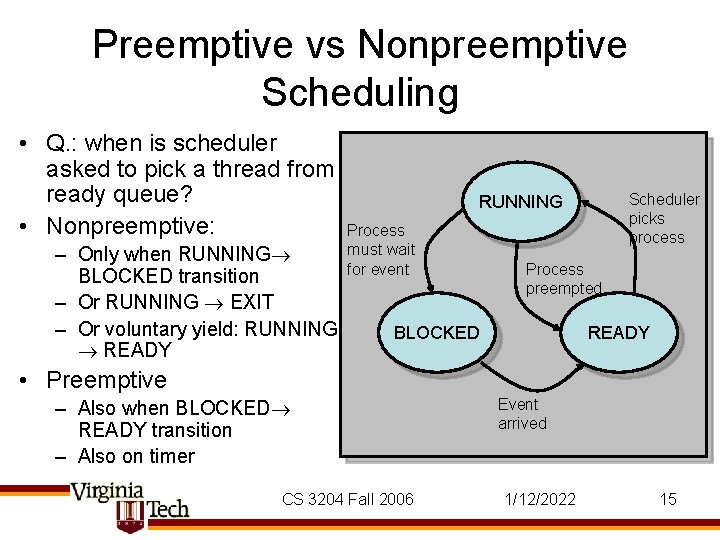

Preemptive vs Nonpreemptive Scheduling • Q. : when is scheduler asked to pick a thread from ready queue? • Nonpreemptive: – Only when RUNNING BLOCKED transition – Or RUNNING EXIT – Or voluntary yield: RUNNING READY Scheduler picks process RUNNING Process must wait for event Process preempted BLOCKED READY • Preemptive – Also when BLOCKED READY transition – Also on timer CS 3204 Fall 2006 Event arrived 1/12/2022 15

CPU Scheduling Goals • Minimize latency – Can mean (avg) completion time – Can mean (avg) response time • Maximize throughput – Throughput: number of finished jobs per time-unit – Implies minimizing overhead (for context-switching, for scheduling algorithm itself) – Requires efficient use of non-CPU resources • Fairness – Minimize variance in waiting time/completion time CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 16

Scheduling Constraints • Reaching those goals is difficult, because – Goals are conflicting: • Latency vs. throughput • Fairness vs. low overhead – Scheduler must operate with incomplete knowledge • Execution time may not be known • I/O device use may not be known – Scheduler must make decision fast • Approximate best solution from huge solution space CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 17

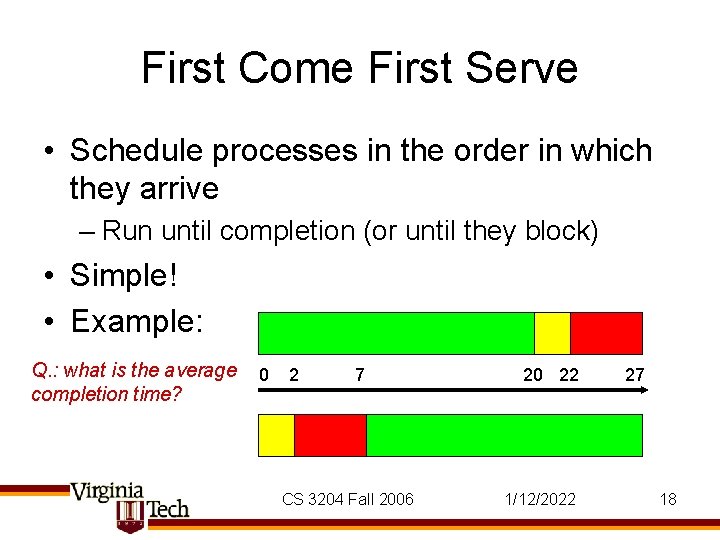

First Come First Serve • Schedule processes in the order in which they arrive – Run until completion (or until they block) • Simple! • Example: Q. : what is the average completion time? 0 2 7 CS 3204 Fall 2006 20 22 1/12/2022 27 18

FCFS (cont’d) • Disadvantage: completion time depends on arrival order – Unfair to short jobs • Possible Convoy Effect: – 1 CPU bound (long CPU bursts, infrequent I/O bursts), multiple I/O bound jobs (frequent I/O bursts, short CPU bursts). – CPU bound process monopolizes CPU: I/O devices are idle – New I/O requests by I/O bound jobs are only issued when CPU bound job blocks – CPU bound job “leads” convoy of I/O bound processes • FCFS not usually used for CPU scheduling, but often used for other resources (network device) CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 19

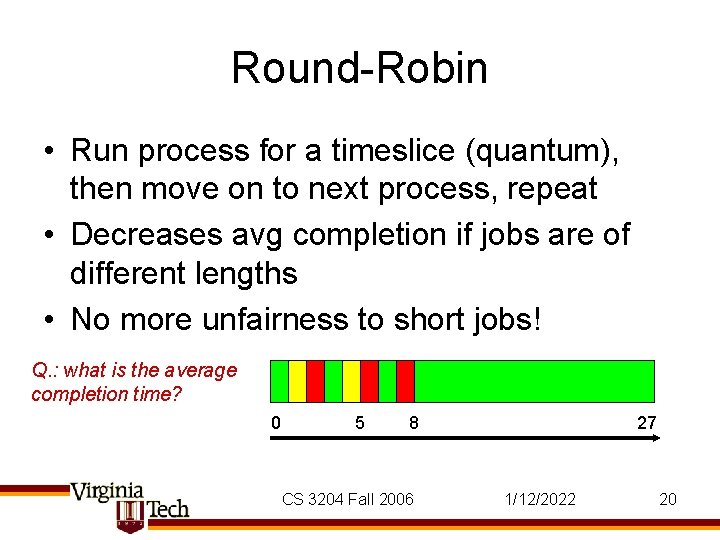

Round-Robin • Run process for a timeslice (quantum), then move on to next process, repeat • Decreases avg completion if jobs are of different lengths • No more unfairness to short jobs! Q. : what is the average completion time? 0 5 8 CS 3204 Fall 2006 27 1/12/2022 20

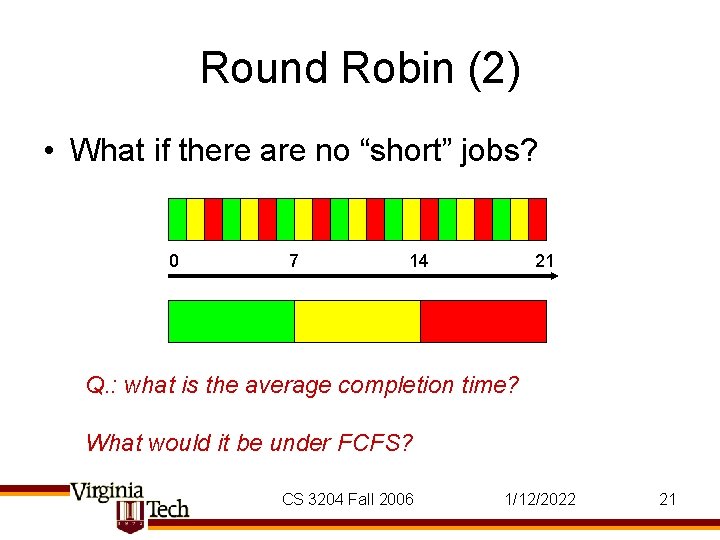

Round Robin (2) • What if there are no “short” jobs? 0 7 14 21 Q. : what is the average completion time? What would it be under FCFS? CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 21

Round Robin – Cost of Time Slicing • Context switching incurs a cost – Direct cost (execute scheduler & context switch) + indirect cost (cache & TLB misses) • Long time slices lower overhead, but approaches FCFS if processes finish before timeslice expires • Short time slices lots of context switches, high overhead • Typical cost: context switch < 10µs • Time slice typically around 100 ms • Note: time slice length != interval between timer interrupts (as you know from Pintos…) – Timer frequency usually 1000 Hz CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 22

Shortest Process Next (SPN) • Idea: remove unfairness towards short processes by always picking the shortest job • If done nonpreemptively also known as: – Shortest Job First (SJF), Shortest Time to Completion First (STCF) • If done preemptively known as: – Shortest Remaining Time (SRT), Shortest Remaining Time to Completion First (SRTCF) CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 23

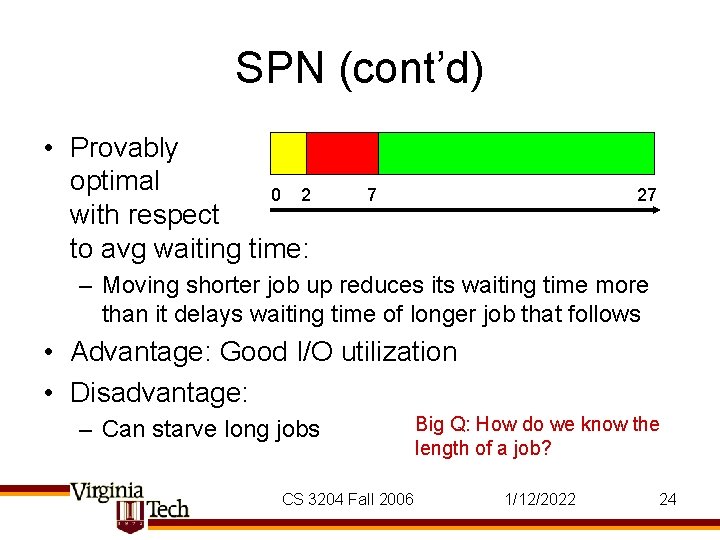

SPN (cont’d) • Provably optimal 0 2 with respect to avg waiting time: 7 27 – Moving shorter job up reduces its waiting time more than it delays waiting time of longer job that follows • Advantage: Good I/O utilization • Disadvantage: – Can starve long jobs CS 3204 Fall 2006 Big Q: How do we know the length of a job? 1/12/2022 24

Practical SPN • Usually don’t know (remaining) execution time – Exception: profiled code in real-time system; or worstcase execution time analysis (WCET) • Idea: determine future from past: – Assume next CPU burst will be as long as previous CPU burst – Or: weigh history using (potentially exponential) average: more recent burst lengths more predictive than past CPU bursts • Note: for some resources, we know or can compute length of next “job”: – Example: disk scheduling (shortest-seek time first) CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 25

Multi-Level Feedback Queue Scheduling • Kleinrock 1969 • Want: – preference for short jobs (tends to lead to good I/O utilization) – longer timeslices for CPU bound jobs (reduces context-switching overhead) • Problem: – Don’t know type of each process – algorithm needs to figure out • Use multiple queues – queue determines priority – usually combined with static priorities (nice values) – many variations of this idea exist CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 26

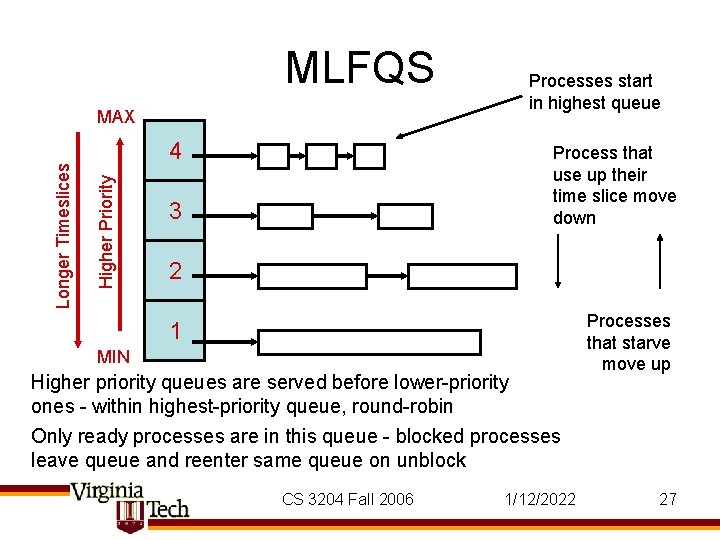

MLFQS 4 Higher Priority Longer Timeslices MAX Processes start in highest queue Process that use up their time slice move down 3 2 1 MIN Higher priority queues are served before lower-priority ones - within highest-priority queue, round-robin Only ready processes are in this queue - blocked processes leave queue and reenter same queue on unblock CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 Processes that starve move up 27

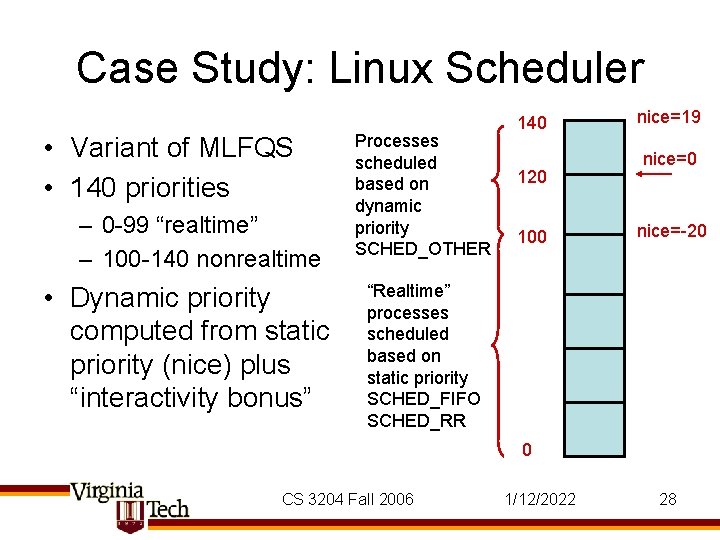

Case Study: Linux Scheduler • Variant of MLFQS • 140 priorities – 0 -99 “realtime” – 100 -140 nonrealtime • Dynamic priority computed from static priority (nice) plus “interactivity bonus” Processes scheduled based on dynamic priority SCHED_OTHER 140 120 100 nice=19 nice=0 nice=-20 “Realtime” processes scheduled based on static priority SCHED_FIFO SCHED_RR 0 CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 28

Linux Scheduler (2) • Instead of recomputation loop, recompute priority at end of each timeslice – dyn_prio = nice + interactivity bonus (-5… 5) • Interactivity bonus depends on sleep_avg – measures time a process was blocked • 2 priority arrays (“active” & “expired”) in each runqueue (Linux calls ready queues “runqueue”) CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 29

![Linux Scheduler (3) struct prio_array { unsigned int nr_active; unsigned long bitmap[BITMAP_SIZE]; struct list_head Linux Scheduler (3) struct prio_array { unsigned int nr_active; unsigned long bitmap[BITMAP_SIZE]; struct list_head](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/6ccbda1d7b5a91c492c8c88a76500aea/image-30.jpg)

Linux Scheduler (3) struct prio_array { unsigned int nr_active; unsigned long bitmap[BITMAP_SIZE]; struct list_head queue[MAX_PRIO]; }; typedef struct prio_array_t; /* Per CPU runqueue */ struct runqueue { prio_array_t *active; prio_array_t *expired; prio_array_t arrays[2]; … } /* find the highest-priority ready thread */ idx = sched_find_first_bit(array->bitmap); queue = array->queue + idx; next = list_entry(queue->next, task_t, run_list); • Finds highest-priority ready thread quickly • Switching active & expired arrays at end of epoch is simple pointer swap (“O(1)” claim) CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 30

Linux Timeslice Computation • Linux scales static priority to timeslice – Nice [ -20 … 19 ] maps to [800 ms … 100 ms … 5 ms] • Various tweaks: – “interactive processes” are reinserted into active array even after timeslice expires • Unless processes in expired array are starving – processes with long timeslices are roundrobin’d with other of equal priority at subtimeslice granularity CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 31

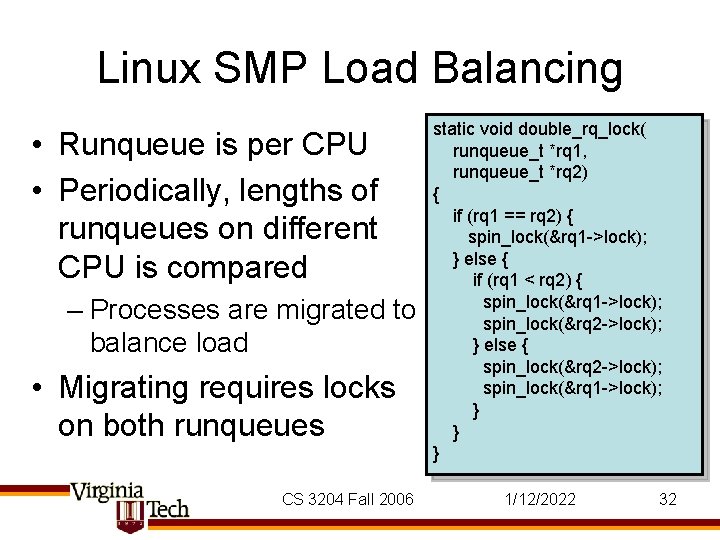

Linux SMP Load Balancing • Runqueue is per CPU • Periodically, lengths of runqueues on different CPU is compared – Processes are migrated to balance load • Migrating requires locks on both runqueues CS 3204 Fall 2006 static void double_rq_lock( runqueue_t *rq 1, runqueue_t *rq 2) { if (rq 1 == rq 2) { spin_lock(&rq 1 ->lock); } else { if (rq 1 < rq 2) { spin_lock(&rq 1 ->lock); spin_lock(&rq 2 ->lock); } else { spin_lock(&rq 2 ->lock); spin_lock(&rq 1 ->lock); } } } 1/12/2022 32

Basic Scheduling: Summary • FCFS: simple – unfair to short jobs & poor I/O performance (convoy effect) • RR: helps short jobs – loses when jobs are equal length • SPN: optimal average waiting time – which, if ignoring blocking time, leads to optimal average completion time – unfair to long jobs – requires knowing (or guessing) the future • MLFQS: approximates SPN without knowing execution time – Can still be unfair to long jobs CS 3204 Fall 2006 1/12/2022 33

- Slides: 33