cs 3102 Theory of Computation Class 21 Undecidability

cs 3102: Theory of Computation Class 21: Undecidability in Theory and Practice Exam 2: Out at end of class today, due Tuesday at 2: 01 pm Spring 2010 University of Virginia David Evans

Menu What does undecidability mean for problems real people (not just CS theorists and Busy Beavers) care about? • • Turing-equivalent Grammar Universal Programming Languages “Return-Oriented Programming” Problems Computers Can and Cannot Solve

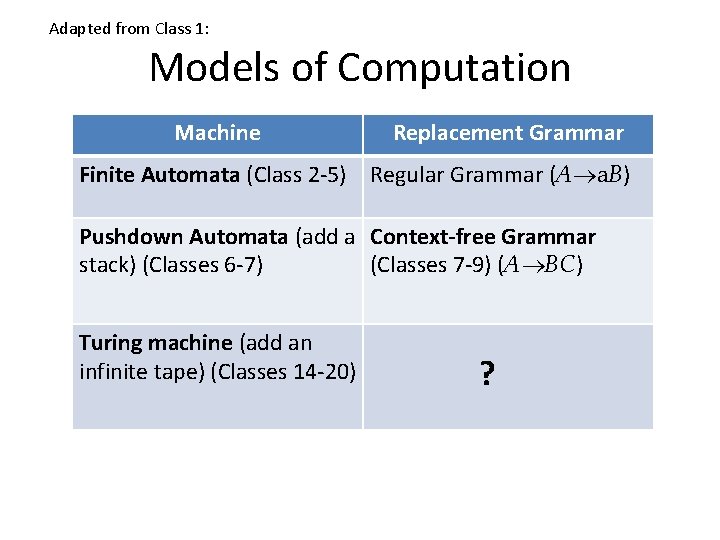

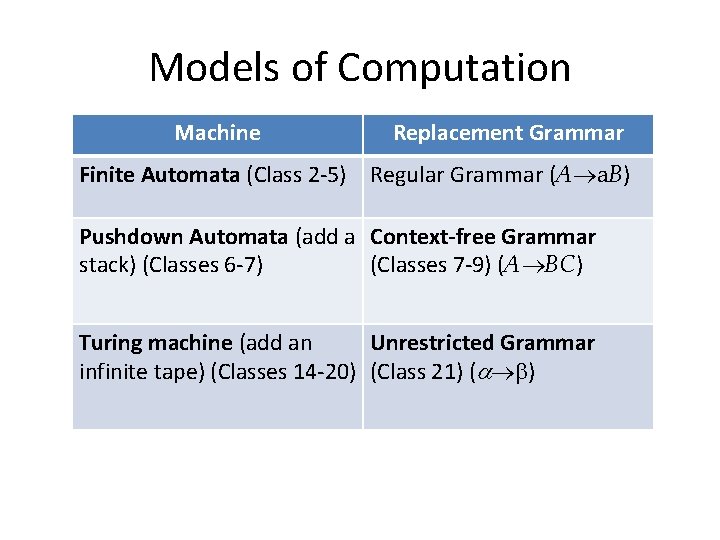

Adapted from Class 1: Models of Computation Machine Replacement Grammar Finite Automata (Class 2 -5) Regular Grammar (A a. B) Pushdown Automata (add a Context-free Grammar (Classes 7 -9) (A BC) stack) (Classes 6 -7) Turing machine (add an infinite tape) (Classes 14 -20) ?

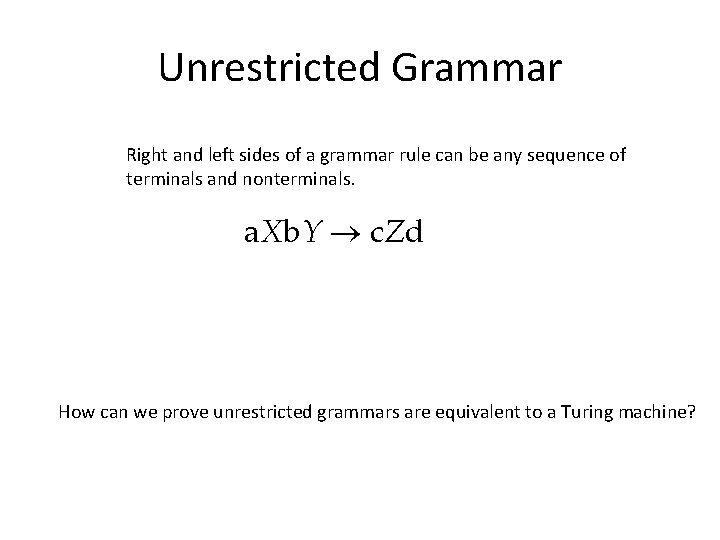

Unrestricted Grammar Right and left sides of a grammar rule can be any sequence of terminals and nonterminals. a. Xb. Y c. Zd How can we prove unrestricted grammars are equivalent to a Turing machine?

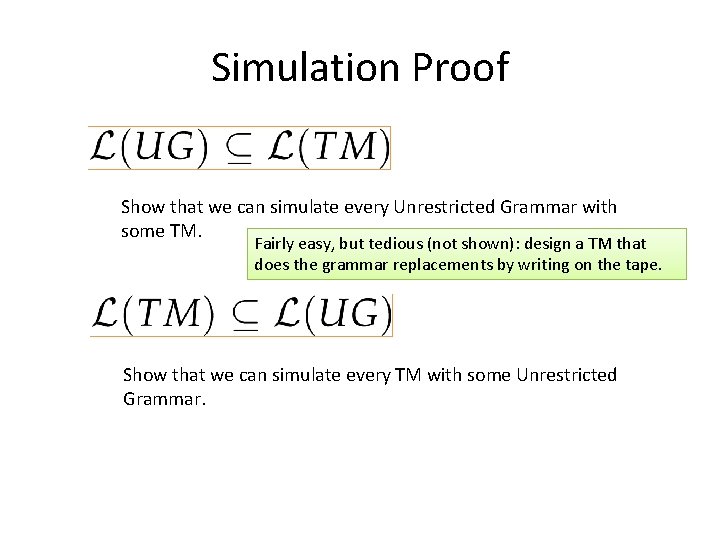

Simulation Proof Show that we can simulate every Unrestricted Grammar with some TM. Fairly easy, but tedious (not shown): design a TM that does the grammar replacements by writing on the tape. Show that we can simulate every TM with some Unrestricted Grammar.

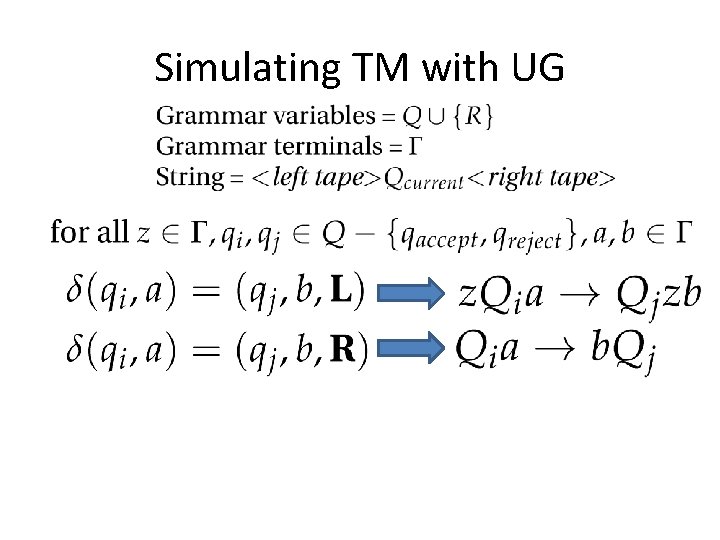

Simulating TM with UG

Simulating TM with UG

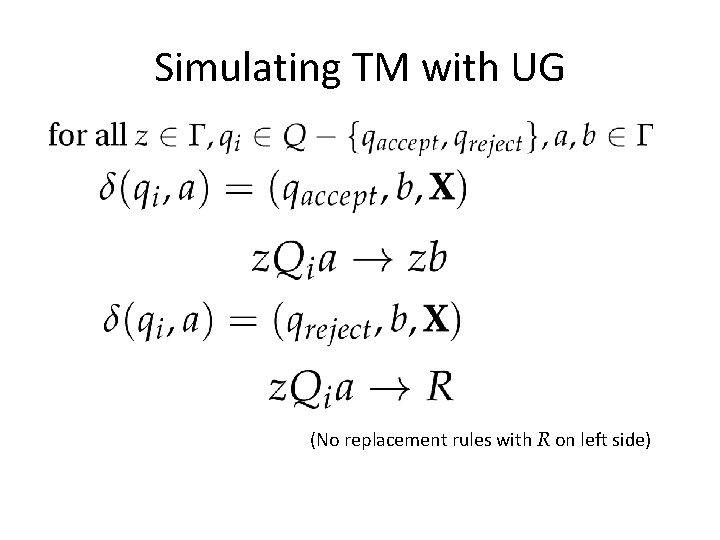

Simulating TM with UG (No replacement rules with R on left side)

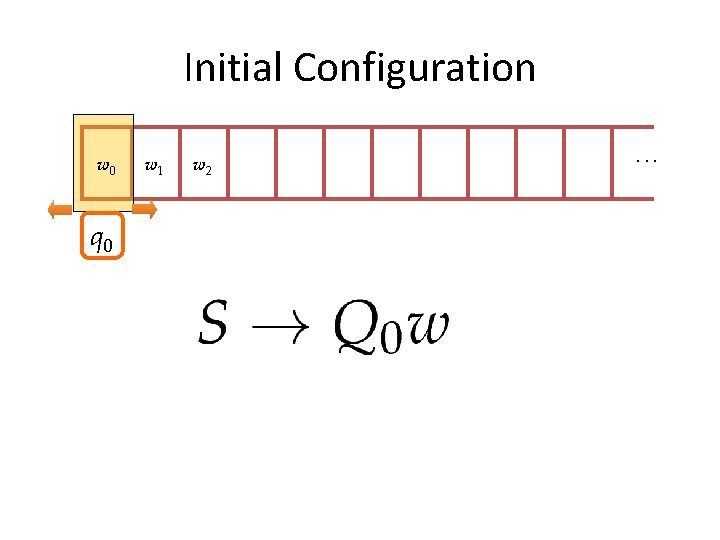

Initial Configuration w 0 q 0 w 1 w 2 . . .

Models of Computation Machine Replacement Grammar Finite Automata (Class 2 -5) Regular Grammar (A a. B) Pushdown Automata (add a Context-free Grammar (Classes 7 -9) (A BC) stack) (Classes 6 -7) Turing machine (add an Unrestricted Grammar infinite tape) (Classes 14 -20) (Class 21) ( )

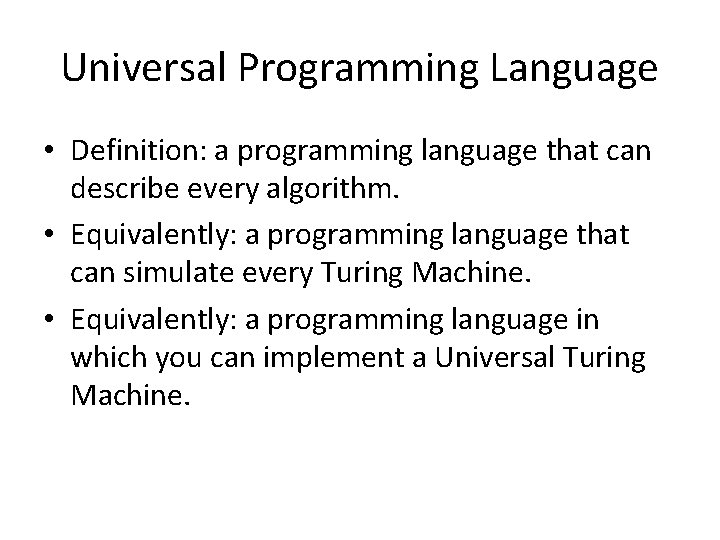

Universal Programming Language • Definition: a programming language that can describe every algorithm. • Equivalently: a programming language that can simulate every Turing Machine. • Equivalently: a programming language in which you can implement a Universal Turing Machine.

Which of these are Universal Programming Languages? BASIC C++ COBOL C# Python x 86 Java HTML PDF Java. Script Post. Script Fortran Scheme Te. X Ruby

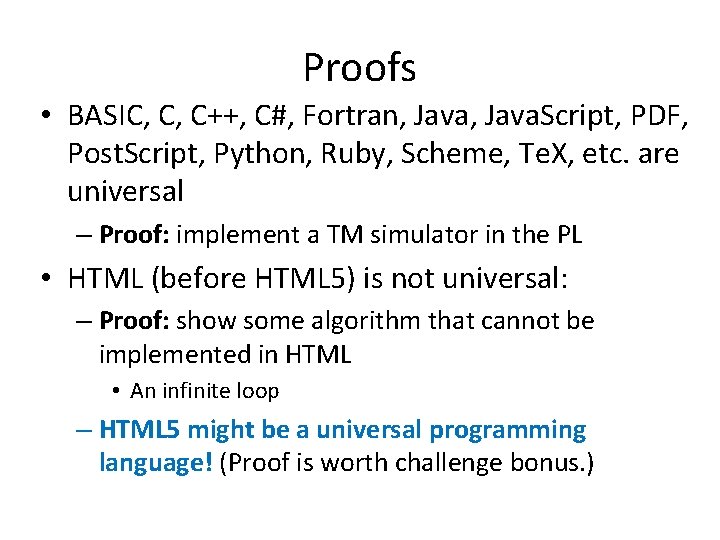

Proofs • BASIC, C, C++, C#, Fortran, Java. Script, PDF, Post. Script, Python, Ruby, Scheme, Te. X, etc. are universal – Proof: implement a TM simulator in the PL • HTML (before HTML 5) is not universal: – Proof: show some algorithm that cannot be implemented in HTML • An infinite loop – HTML 5 might be a universal programming language! (Proof is worth challenge bonus. )

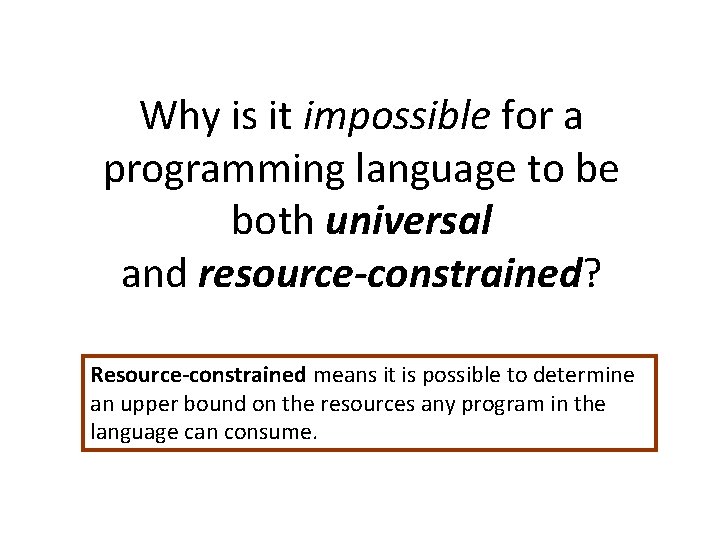

Why is it impossible for a programming language to be both universal and resource-constrained? Resource-constrained means it is possible to determine an upper bound on the resources any program in the language can consume.

All universal programming language are equivalent in power: they can all simulate a TM, which can carry out any mechanical algorithm.

Why so many equally powerful programming languages?

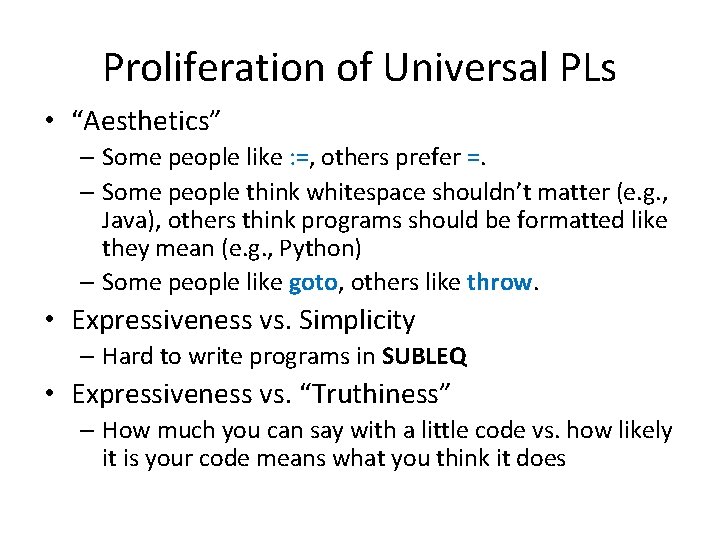

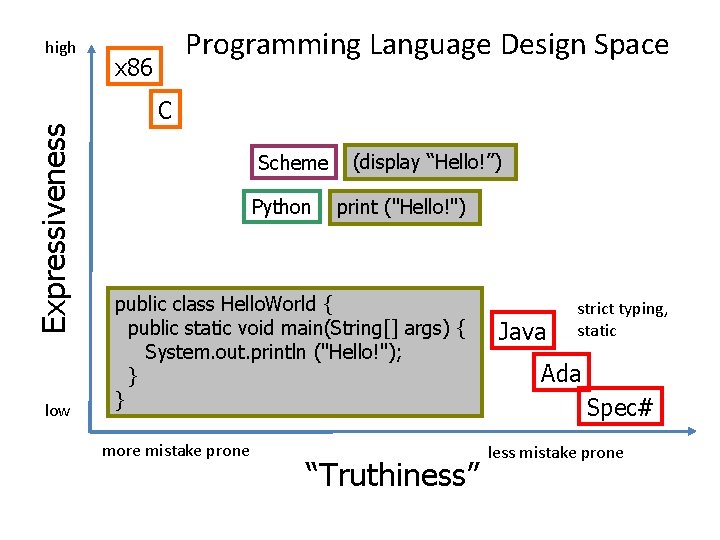

Proliferation of Universal PLs • “Aesthetics” – Some people like : =, others prefer =. – Some people think whitespace shouldn’t matter (e. g. , Java), others think programs should be formatted like they mean (e. g. , Python) – Some people like goto, others like throw. • Expressiveness vs. Simplicity – Hard to write programs in SUBLEQ • Expressiveness vs. “Truthiness” – How much you can say with a little code vs. how likely it is your code means what you think it does

Expressiveness high low Programming Language Design Space x 86 C Scheme Python (display “Hello!”) print ("Hello!") public class Hello. World { public static void main(String[] args) { System. out. println ("Hello!"); } } more mistake prone “Truthiness” Java strict typing, static Ada Spec# less mistake prone

Do most x 86 programs contain Universal Turing Machines? Hovav Shacham. The Geometry of Innocent Flesh on the Bone: Return-into-libc without Function Calls (on the x 86). CCS 2007. [Paper link]

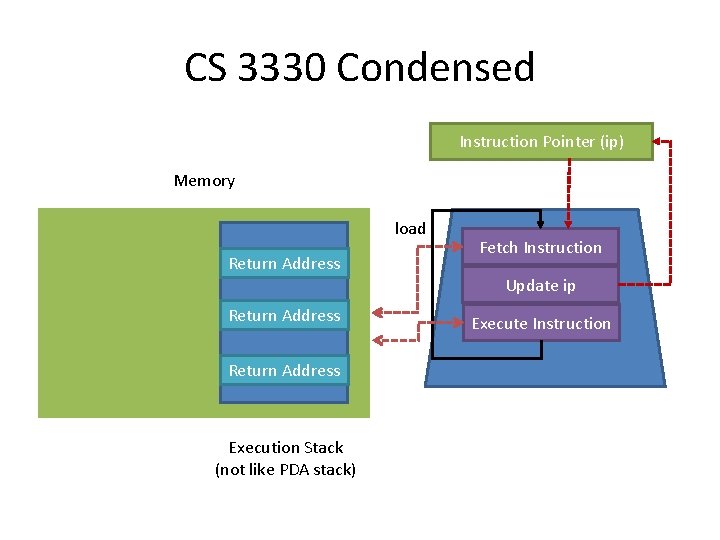

CS 3330 Condensed Instruction Pointer (ip) Memory load Return Address Fetch Instruction Update ip Stack Return Address Execution Stack (not like PDA stack) Execute Instruction

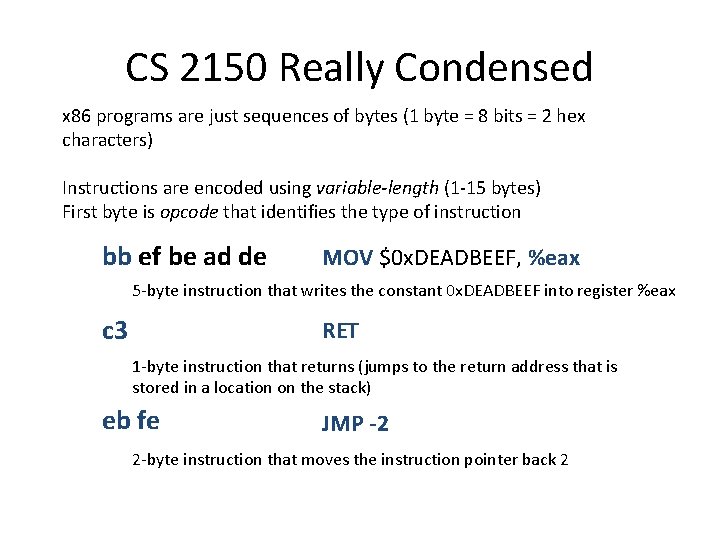

CS 2150 Really Condensed x 86 programs are just sequences of bytes (1 byte = 8 bits = 2 hex characters) Instructions are encoded using variable-length (1 -15 bytes) First byte is opcode that identifies the type of instruction bb ef be ad de MOV $0 x. DEADBEEF, %eax 5 -byte instruction that writes the constant 0 x. DEADBEEF into register %eax c 3 RET 1 -byte instruction that returns (jumps to the return address that is stored in a location on the stack) eb fe JMP -2 2 -byte instruction that moves the instruction pointer back 2

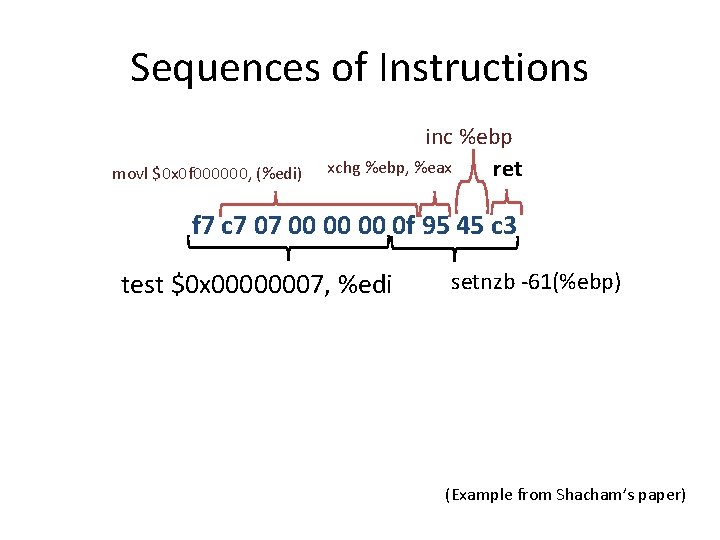

Sequences of Instructions movl $0 x 0 f 000000, (%edi) inc %ebp xchg %ebp, %eax ret f 7 c 7 07 00 00 00 0 f 95 45 c 3 test $0 x 00000007, %edi setnzb -61(%ebp) (Example from Shacham’s paper)

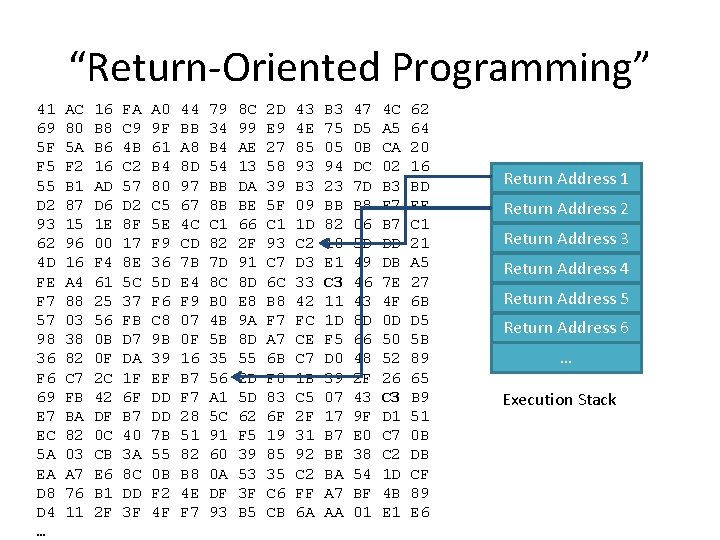

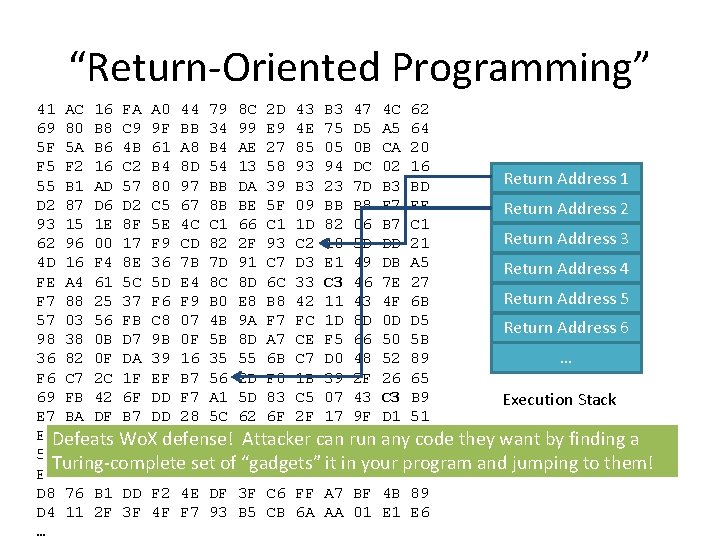

“Return-Oriented Programming” 41 69 5 F F 5 55 D 2 93 62 4 D FE F 7 57 98 36 F 6 69 E 7 EC 5 A EA D 8 D 4 … AC 80 5 A F 2 B 1 87 15 96 16 A 4 88 03 38 82 C 7 FB BA 82 03 A 7 76 11 16 B 8 B 6 16 AD D 6 1 E 00 F 4 61 25 56 0 B 0 F 2 C 42 DF 0 C CB E 6 B 1 2 F FA C 9 4 B C 2 57 D 2 8 F 17 8 E 5 C 37 FB D 7 DA 1 F 6 F B 7 40 3 A 8 C DD 3 F A 0 9 F 61 B 4 80 C 5 5 E F 9 36 5 D F 6 C 8 9 B 39 EF DD DD 7 B 55 0 B F 2 4 F 44 BB A 8 8 D 97 67 4 C CD 7 B E 4 F 9 07 0 F 16 B 7 F 7 28 51 82 B 8 4 E F 7 79 34 B 4 54 BB 8 B C 1 82 7 D 8 C B 0 4 B 5 B 35 56 A 1 5 C 91 60 0 A DF 93 8 C 99 AE 13 DA BE 66 2 F 91 8 D E 8 9 A 8 D 55 2 D 5 D 62 F 5 39 53 3 F B 5 2 D E 9 27 58 39 5 F C 1 93 C 7 6 C B 8 F 7 A 7 6 B F 0 83 6 F 19 85 35 C 6 CB 43 4 E 85 93 B 3 09 1 D C 2 D 3 33 42 FC CE C 7 1 B C 5 2 F 31 92 C 2 FF 6 A B 3 75 05 94 23 BB 82 10 E 1 C 3 11 1 D F 5 D 0 39 07 17 B 7 BE BA A 7 AA 47 D 5 0 B DC 7 D B 8 06 5 D 49 46 43 8 D 66 48 2 F 43 9 F E 0 38 54 BF 01 4 C A 5 CA 02 B 3 F 7 B 7 DD DB 7 E 4 F 0 D 50 52 26 C 3 D 1 C 7 C 2 1 D 4 B E 1 62 64 20 16 BD EF C 1 21 A 5 27 6 B D 5 5 B 89 65 B 9 51 0 B DB CF 89 E 6 Return Address 1 Return Address 2 Return Address 3 Return Address 4 Return Address 5 Return Address 6 … Execution Stack

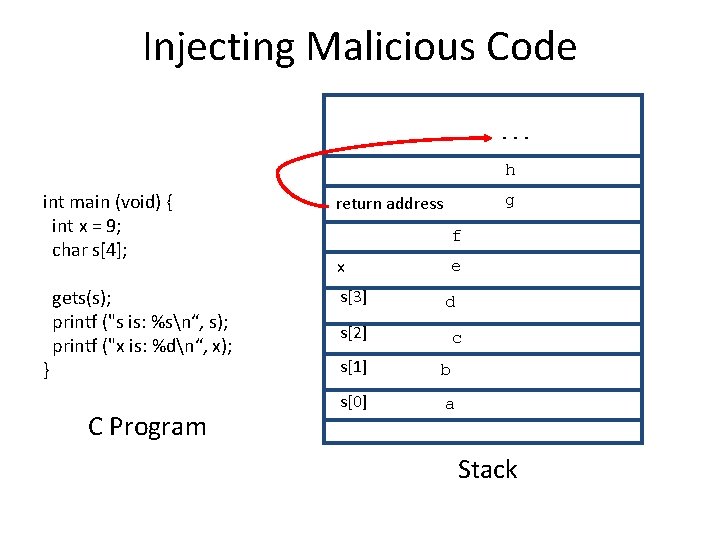

Injecting Malicious Code. . . h int main (void) { int x = 9; char s[4]; } gets(s); printf ("s is: %sn“, s); printf ("x is: %dn“, x); C Program g return address f x s[3] e d s[2] c s[1] b s[0] a Stack

![Buffer Overflows int main (void) { int x = 9; char s[4]; } gets(s); Buffer Overflows int main (void) { int x = 9; char s[4]; } gets(s);](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/18aa9b851aceab269afda703d3add196/image-25.jpg)

Buffer Overflows int main (void) { int x = 9; char s[4]; } gets(s); printf ("s is: %sn“, s); printf ("x is: %dn“, x); Note: your results may vary (depending on machine, compiler, what else is running, time of day, etc. ). This is what makes C fun! > gcc -o bounds. c > bounds abcdefghijkl (User input) s is: abcdefghijkl x is: 9 > bounds abcdefghijklm s is: abcdefghijklmn x is: 1828716553 = 0 x 6 d 000009 > bounds abcdefghijkln s is: abcdefghijkln x is: 1845493769 = 0 x 6 e 000009 > bounds aaa. . . [a few thousand characters] crashes shell What does this kind of mistake look like in a popular server?

Code Red

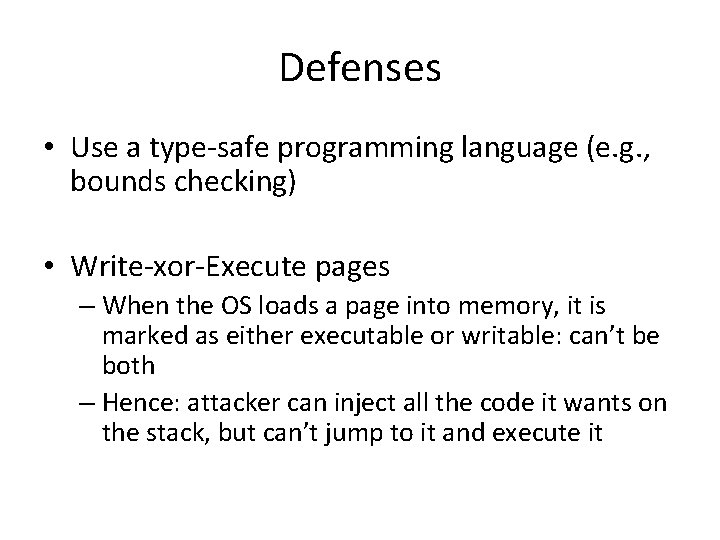

Defenses • Use a type-safe programming language (e. g. , bounds checking) • Write-xor-Execute pages – When the OS loads a page into memory, it is marked as either executable or writable: can’t be both – Hence: attacker can inject all the code it wants on the stack, but can’t jump to it and execute it

“Return-Oriented Programming” 41 AC 16 FA A 0 44 79 8 C 2 D 43 B 3 47 4 C 62 69 80 B 8 C 9 9 F BB 34 99 E 9 4 E 75 D 5 A 5 64 5 F 5 A B 6 4 B 61 A 8 B 4 AE 27 85 05 0 B CA 20 F 5 F 2 16 C 2 B 4 8 D 54 13 58 93 94 DC 02 16 Return Address 1 55 B 1 AD 57 80 97 BB DA 39 B 3 23 7 D B 3 BD D 2 87 D 6 D 2 C 5 67 8 B BE 5 F 09 BB B 8 F 7 EF Return Address 2 93 15 1 E 8 F 5 E 4 C C 1 66 C 1 1 D 82 06 B 7 C 1 Return Address 3 62 96 00 17 F 9 CD 82 2 F 93 C 2 10 5 D DD 21 4 D 16 F 4 8 E 36 7 B 7 D 91 C 7 D 3 E 1 49 DB A 5 Return Address 4 FE A 4 61 5 C 5 D E 4 8 C 8 D 6 C 33 C 3 46 7 E 27 Return Address 5 F 7 88 25 37 F 6 F 9 B 0 E 8 B 8 42 11 43 4 F 6 B 57 03 56 FB C 8 07 4 B 9 A F 7 FC 1 D 8 D 0 D D 5 Return Address 6 98 38 0 B D 7 9 B 0 F 5 B 8 D A 7 CE F 5 66 50 5 B 36 82 0 F DA 39 16 35 55 6 B C 7 D 0 48 52 89 … F 6 C 7 2 C 1 F EF B 7 56 2 D F 0 1 B 39 2 F 26 65 69 FB 42 6 F DD F 7 A 1 5 D 83 C 5 07 43 C 3 B 9 Execution Stack E 7 BA DF B 7 DD 28 5 C 62 6 F 2 F 17 9 F D 1 51 ECDefeats 82 0 C Wo. X 40 7 B 51 91 F 5 19 31 can B 7 run E 0 any C 7 0 B defense! Attacker code they want by finding a 5 A 03 CB 3 A 55 82 60 39 85 92 BE 38 C 2 DB Turing-complete set of “gadgets” it in your program and jumping to them! EA A 7 E 6 8 C 0 B B 8 0 A 53 35 C 2 BA 54 1 D CF D 8 76 B 1 DD F 2 4 E DF 3 F C 6 FF A 7 BF 4 B 89 D 4 11 2 F 3 F 4 F F 7 93 B 5 CB 6 A AA 01 E 6 …

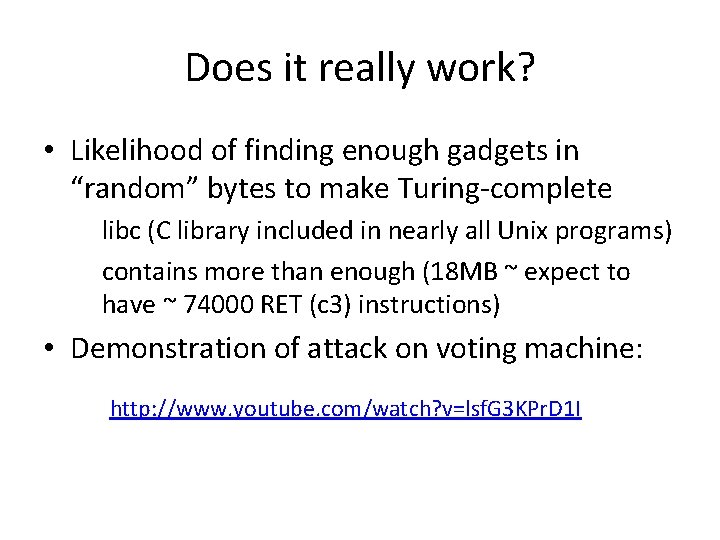

Does it really work? • Likelihood of finding enough gadgets in “random” bytes to make Turing-complete libc (C library included in nearly all Unix programs) contains more than enough (18 MB ~ expect to have ~ 74000 RET (c 3) instructions) • Demonstration of attack on voting machine: http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=lsf. G 3 KPr. D 1 I

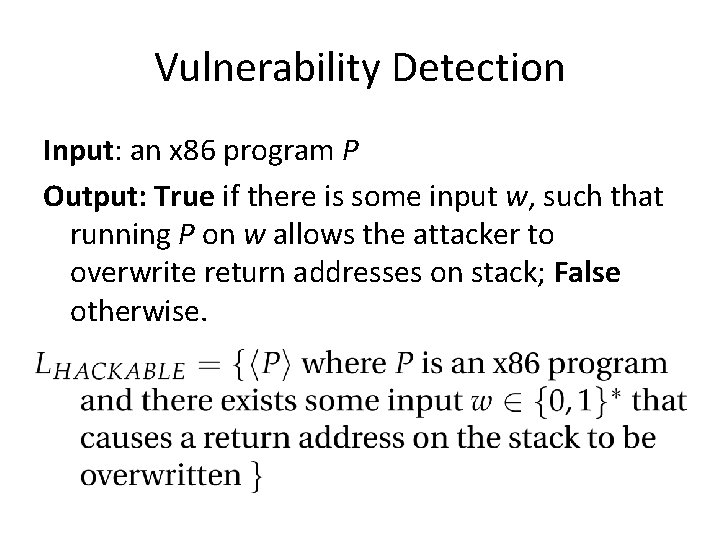

Vulnerability Detection Input: an x 86 program P Output: True if there is some input w, such that running P on w allows the attacker to overwrite return addresses on stack; False otherwise.

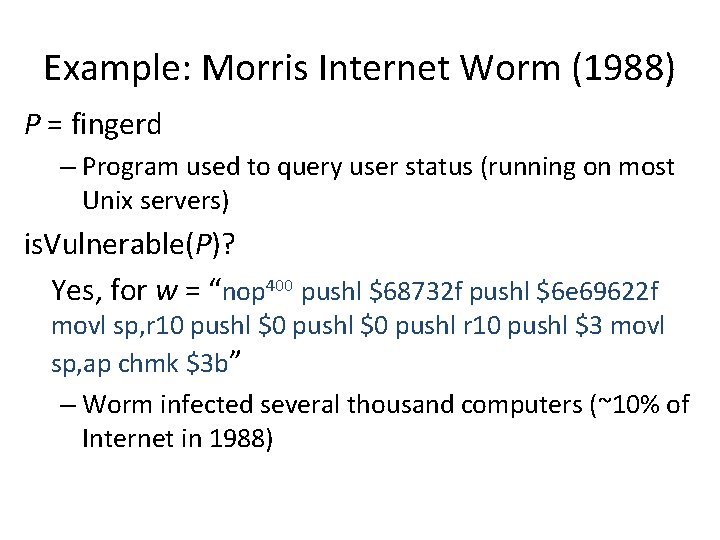

Example: Morris Internet Worm (1988) P = fingerd – Program used to query user status (running on most Unix servers) is. Vulnerable(P)? Yes, for w = “nop 400 pushl $68732 f pushl $6 e 69622 f movl sp, r 10 pushl $0 pushl r 10 pushl $3 movl sp, ap chmk $3 b” – Worm infected several thousand computers (~10% of Internet in 1988)

Vulnerability Detection Input: an x 86 program P Output: True if there is some input w, such that running P on w allows the attacker to overwrite return addresses on stack; False otherwise.

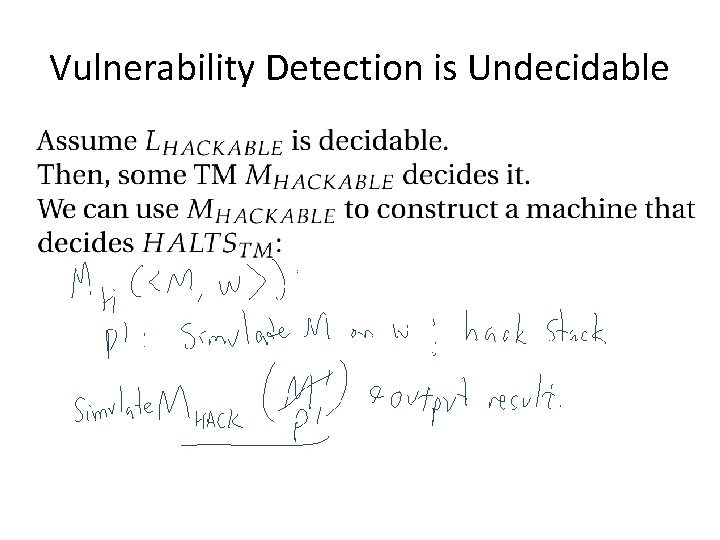

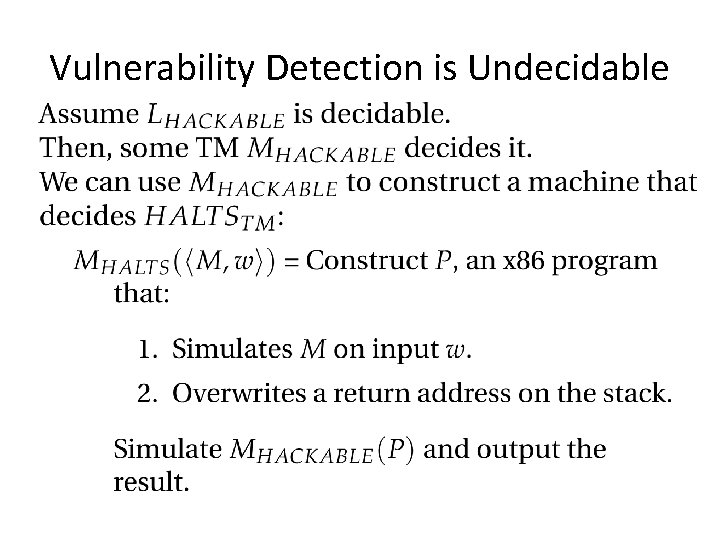

Vulnerability Detection is Undecidable

Vulnerability Detection is Undecidable

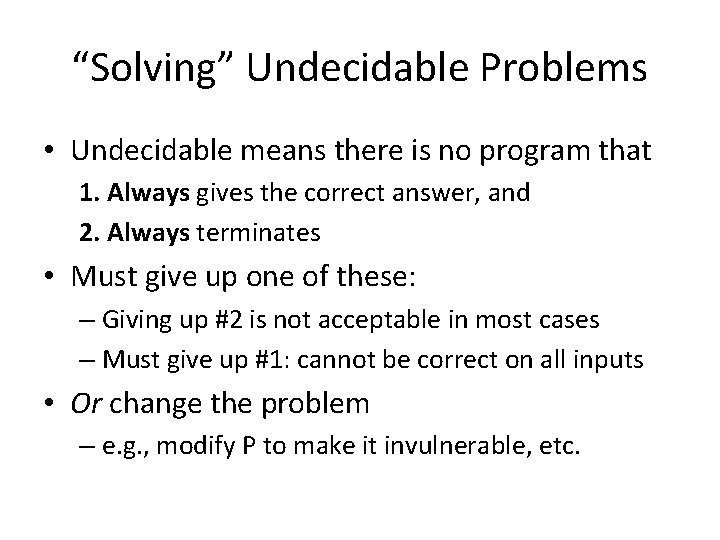

“Solving” Undecidable Problems • Undecidable means there is no program that 1. Always gives the correct answer, and 2. Always terminates • Must give up one of these: – Giving up #2 is not acceptable in most cases – Must give up #1: cannot be correct on all inputs • Or change the problem – e. g. , modify P to make it invulnerable, etc.

“Impossibility” of Vulnerability Detection

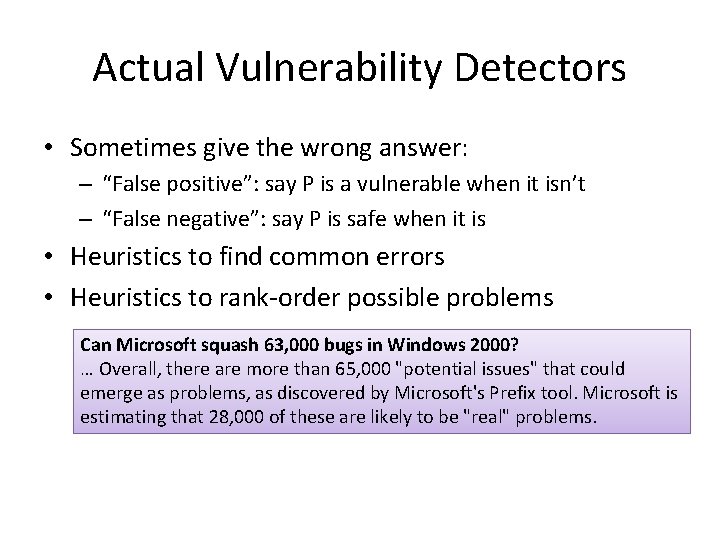

Actual Vulnerability Detectors • Sometimes give the wrong answer: – “False positive”: say P is a vulnerable when it isn’t – “False negative”: say P is safe when it is • Heuristics to find common errors • Heuristics to rank-order possible problems Can Microsoft squash 63, 000 bugs in Windows 2000? … Overall, there are more than 65, 000 "potential issues" that could emerge as problems, as discovered by Microsoft's Prefix tool. Microsoft is estimating that 28, 000 of these are likely to be "real" problems.

Computability in Theory and Practice (Intellectual Computability Discussion on TV) http: //video. google. com/videoplay? docid=1623254076490030585#

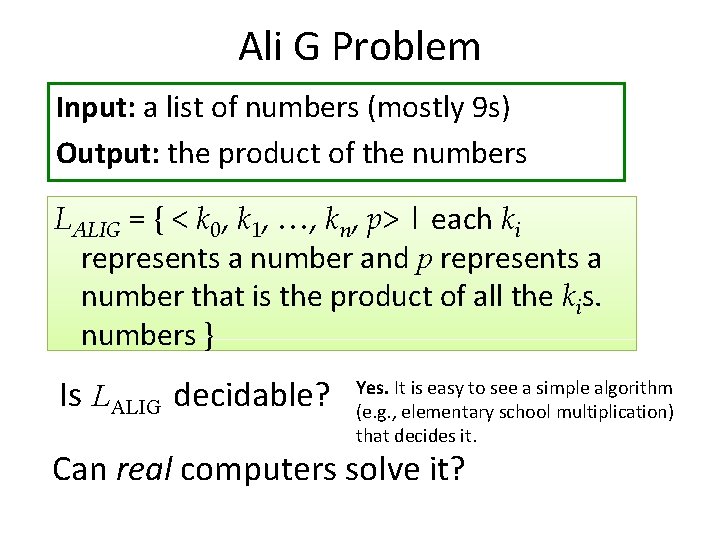

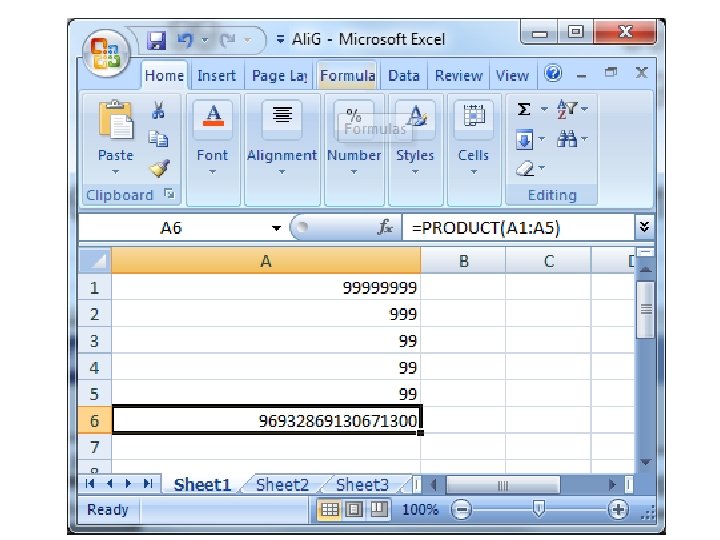

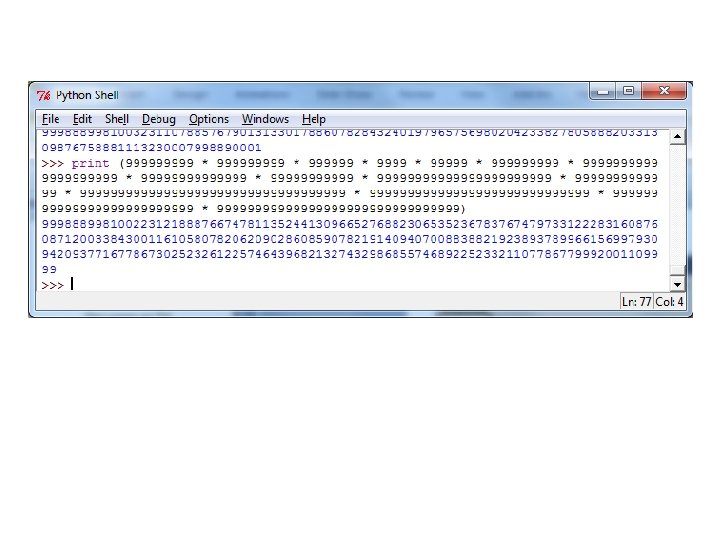

Ali G Problem Input: a list of numbers (mostly 9 s) Output: the product of the numbers LALIG = { < k 0, k 1, …, kn, p> | each ki represents a number and p represents a number that is the product of all the kis. numbers } Is LALIG decidable? Yes. It is easy to see a simple algorithm (e. g. , elementary school multiplication) that decides it. Can real computers solve it?

Ali G was Right! • Theory assumes ideal computers: – Unlimited, perfect memory – Unlimited (finite) time • Real computers have: – Limited memory, time, power outages, flaky programming languages, etc. – There are many decidable problems we cannot solve with real computer: the actual inputs do matter (in practice, but not in theory!)

Charge • Exam 2 out now • Due at beginning of class, Tuesday • It has some pretty tough questions (and no really easy questions): don’t get stressed out if you can’t answer everything

- Slides: 43