CS 267 Shared Memory Machines Programming Example Sharks

![Shared Memory Code for Computing a Sum s = f(A[0]) + f(A[1]) static int Shared Memory Code for Computing a Sum s = f(A[0]) + f(A[1]) static int](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/ac720d992cedeb1d3257ea65b246b09b/image-5.jpg)

![Improved Code for Computing a Sum s = f(A[0]) + … + f(A[n-1]) static Improved Code for Computing a Sum s = f(A[0]) + … + f(A[n-1]) static](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/ac720d992cedeb1d3257ea65b246b09b/image-22.jpg)

![Improved Code for Computing a Sum s = f(A[0]) + … + f(A[n-1]) static Improved Code for Computing a Sum s = f(A[0]) + … + f(A[n-1]) static](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/ac720d992cedeb1d3257ea65b246b09b/image-23.jpg)

- Slides: 60

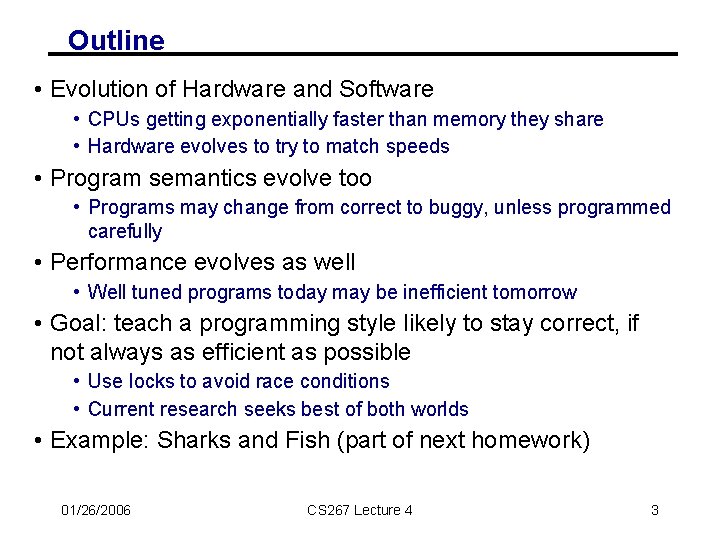

CS 267: Shared Memory Machines Programming Example: Sharks and Fish James Demmel demmel@cs. berkeley. edu www. cs. berkeley. edu/~demmel/cs 267_Spr 06 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 1

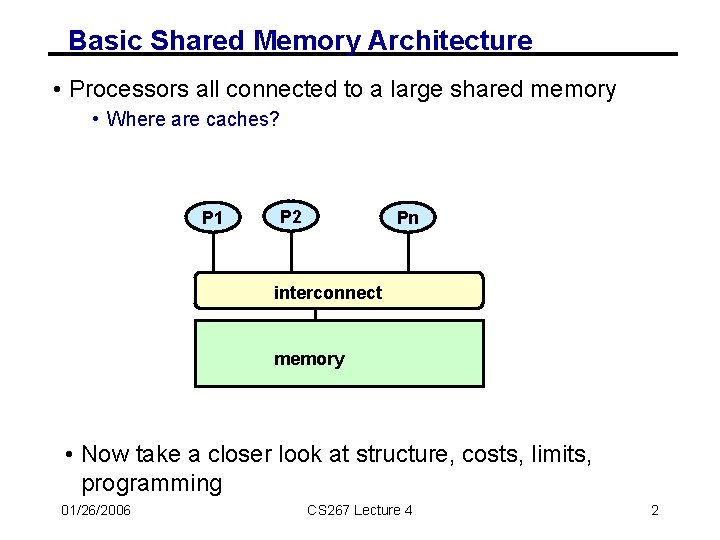

Basic Shared Memory Architecture • Processors all connected to a large shared memory • Where are caches? P 1 P 2 Pn interconnect memory • Now take a closer look at structure, costs, limits, programming 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 2

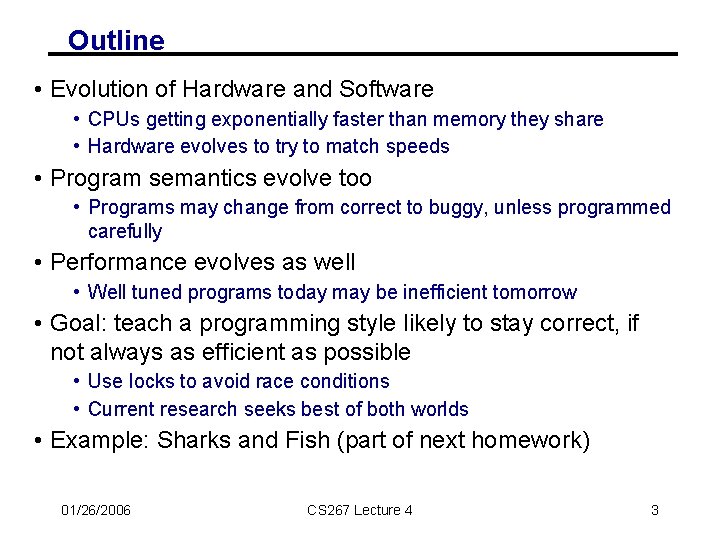

Outline • Evolution of Hardware and Software • CPUs getting exponentially faster than memory they share • Hardware evolves to try to match speeds • Program semantics evolve too • Programs may change from correct to buggy, unless programmed carefully • Performance evolves as well • Well tuned programs today may be inefficient tomorrow • Goal: teach a programming style likely to stay correct, if not always as efficient as possible • Use locks to avoid race conditions • Current research seeks best of both worlds • Example: Sharks and Fish (part of next homework) 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 3

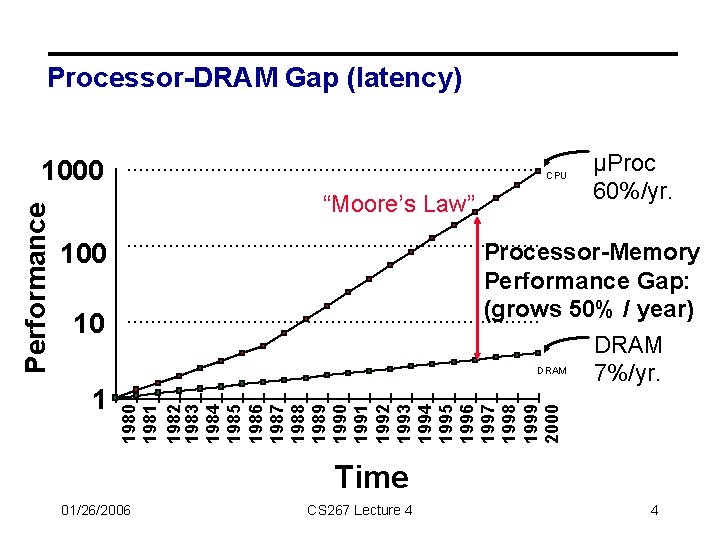

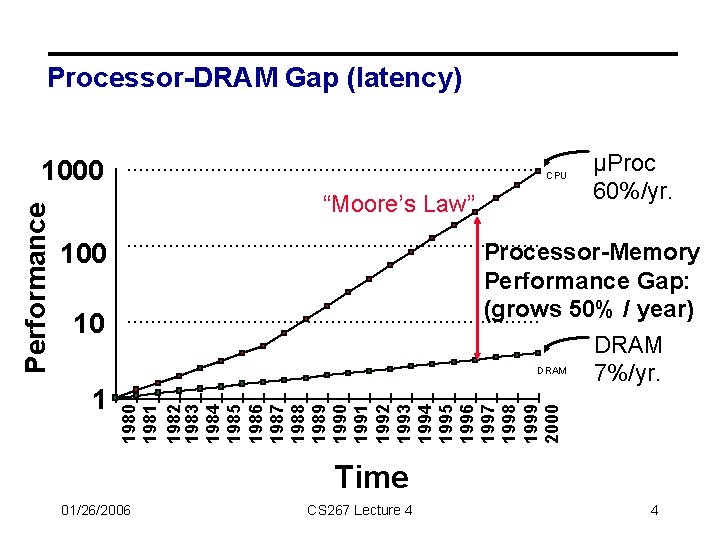

Processor-DRAM Gap (latency) CPU “Moore’s Law” 100 Processor-Memory Performance Gap: (grows 50% / year) DRAM 7%/yr. 10 1 µProc 60%/yr. 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 Performance 1000 Time 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 4

![Shared Memory Code for Computing a Sum s fA0 fA1 static int Shared Memory Code for Computing a Sum s = f(A[0]) + f(A[1]) static int](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/ac720d992cedeb1d3257ea65b246b09b/image-5.jpg)

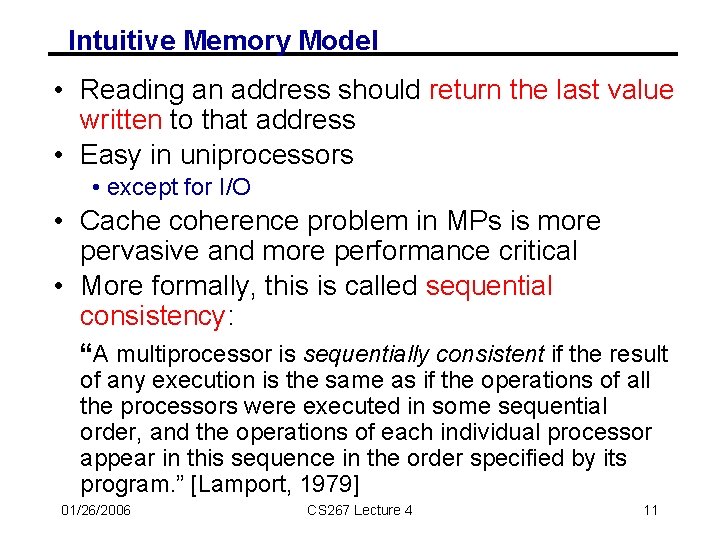

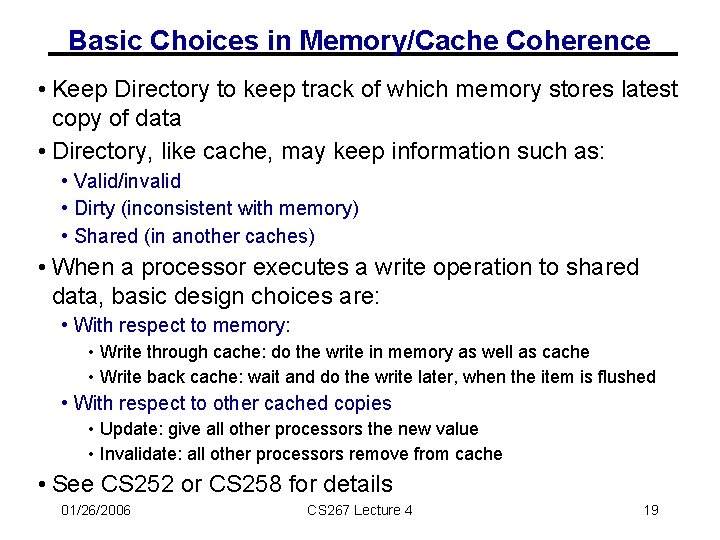

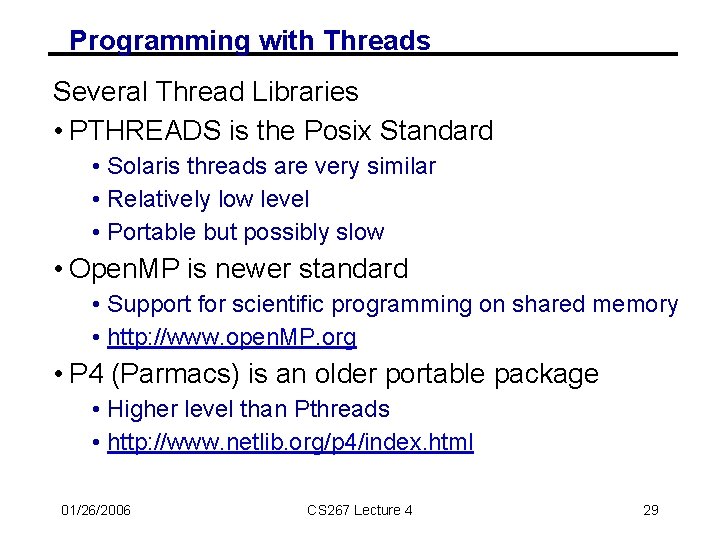

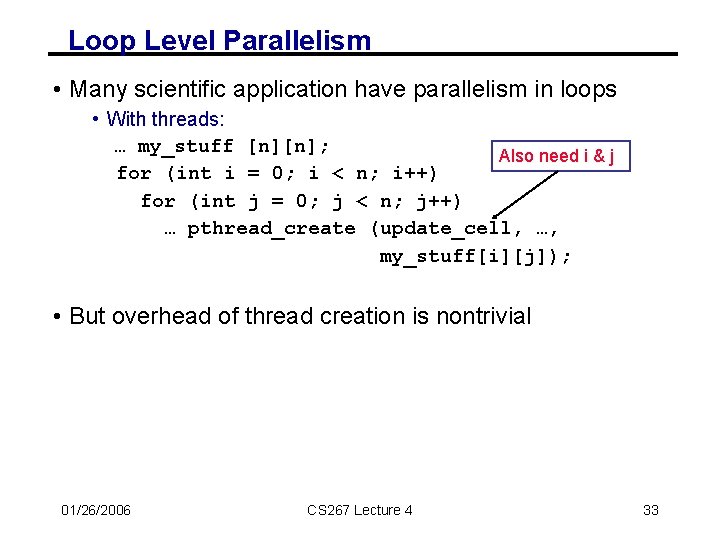

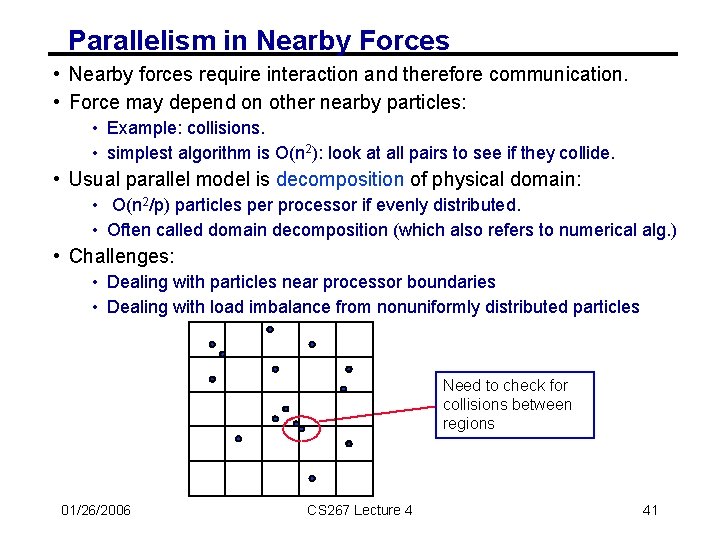

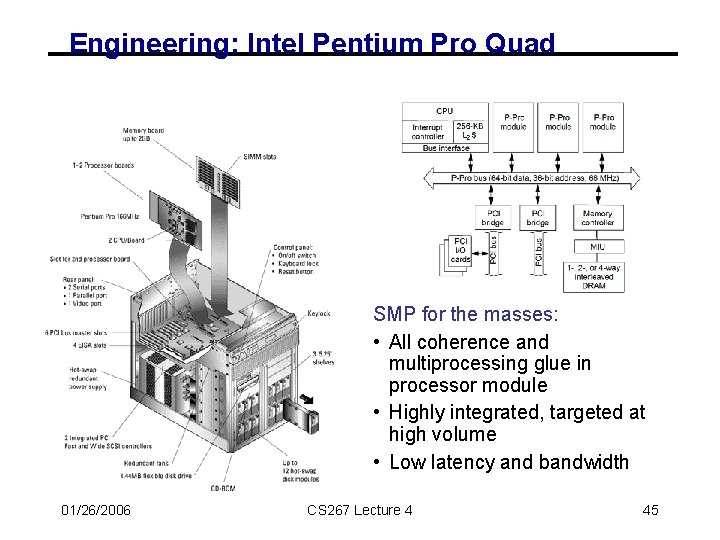

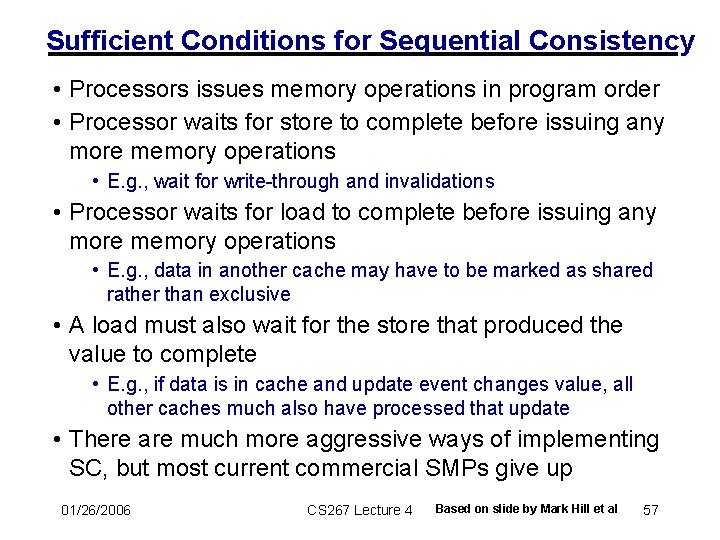

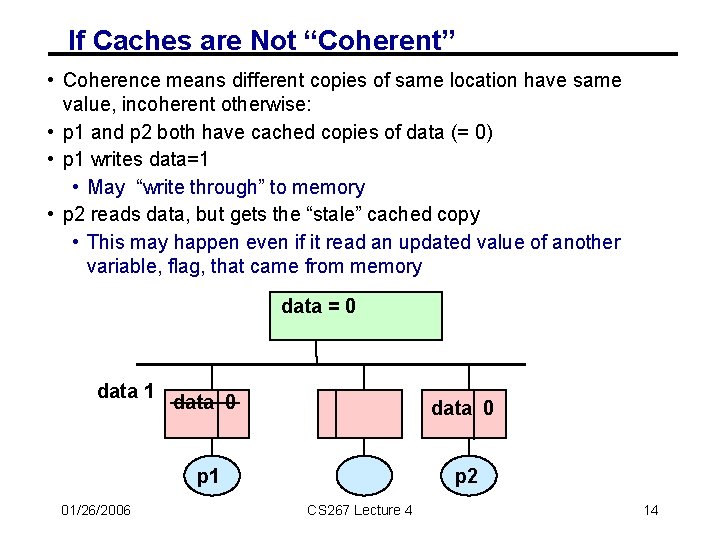

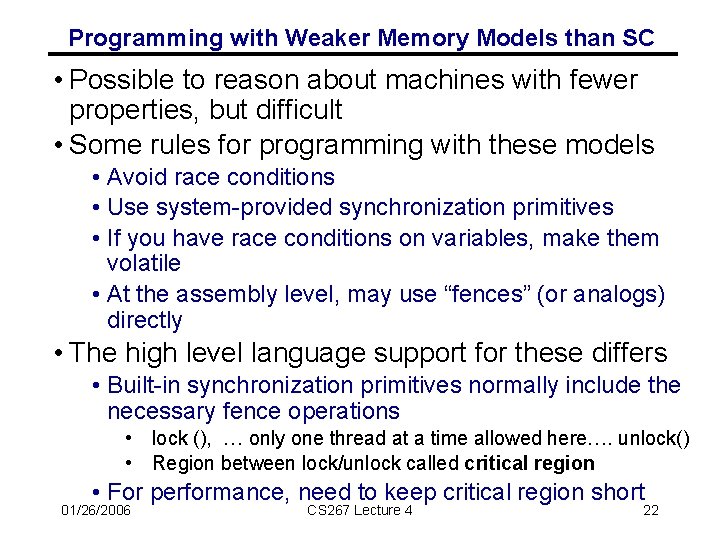

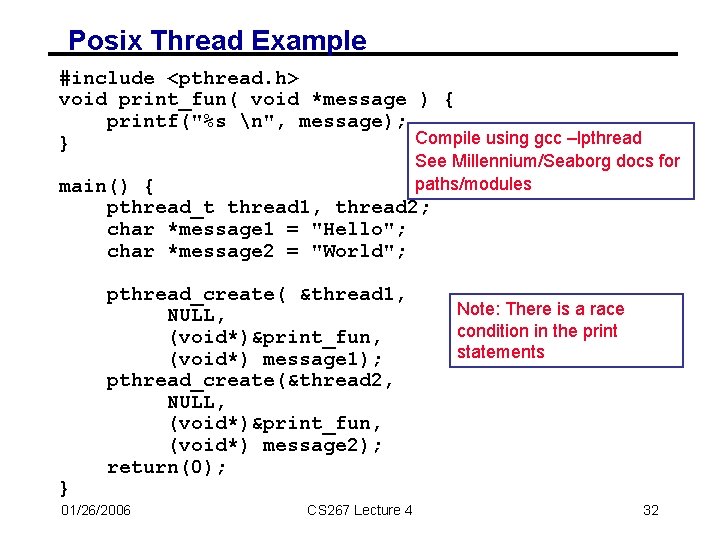

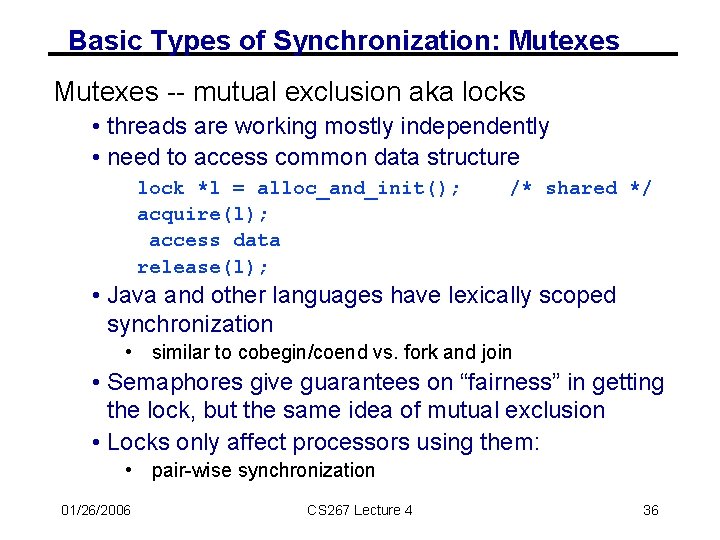

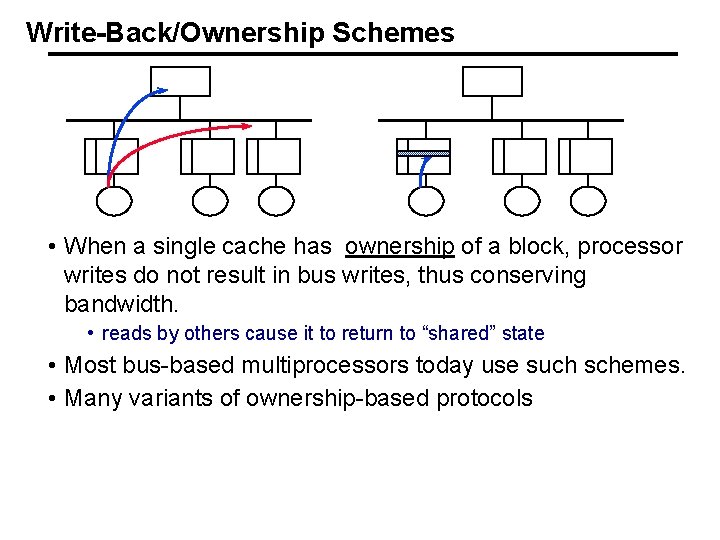

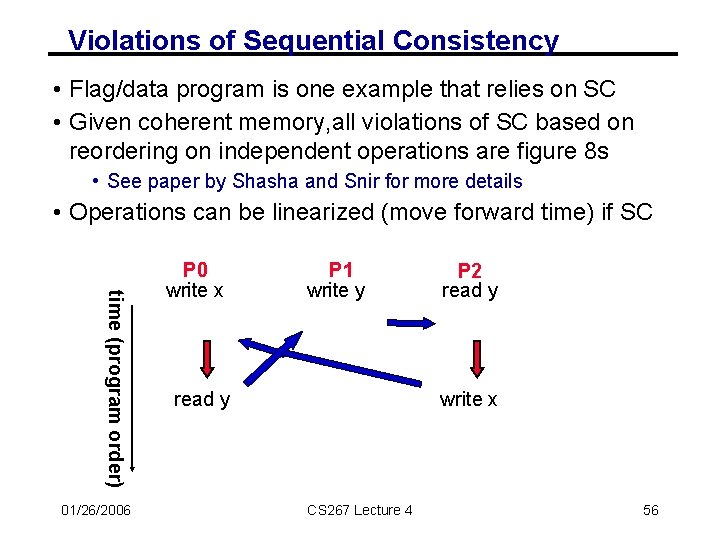

Shared Memory Code for Computing a Sum s = f(A[0]) + f(A[1]) static int s = 0; Thread 0 Thread 1 s = s + f(A[0]) s = s + f(A[1]) • Might get f(A[0]) + f(A[1]) or f(A[0]) or f(A[1]) • Problem is a race condition on variable s in the program • A race condition or data race occurs when: - two processors (or two threads) access the same variable, and at least one does a write. - The accesses are concurrent (not synchronized) so they could happen simultaneously 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 5

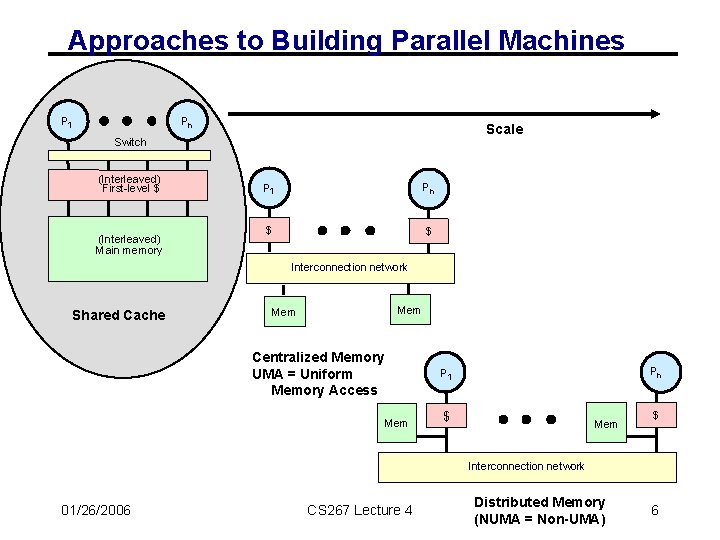

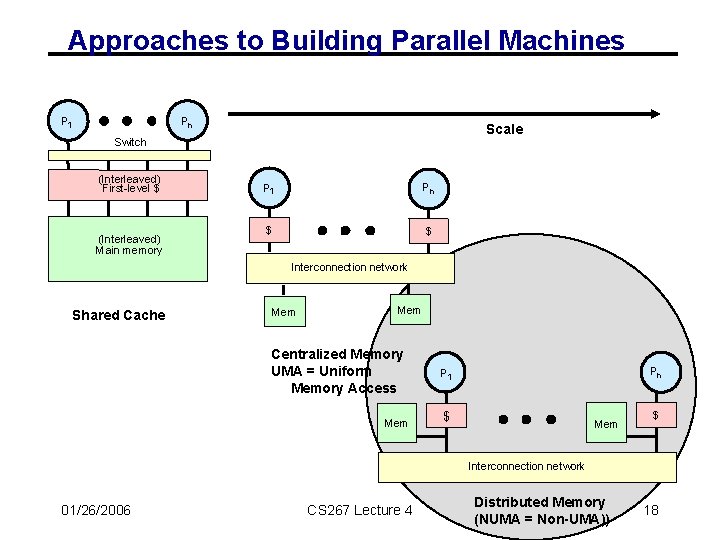

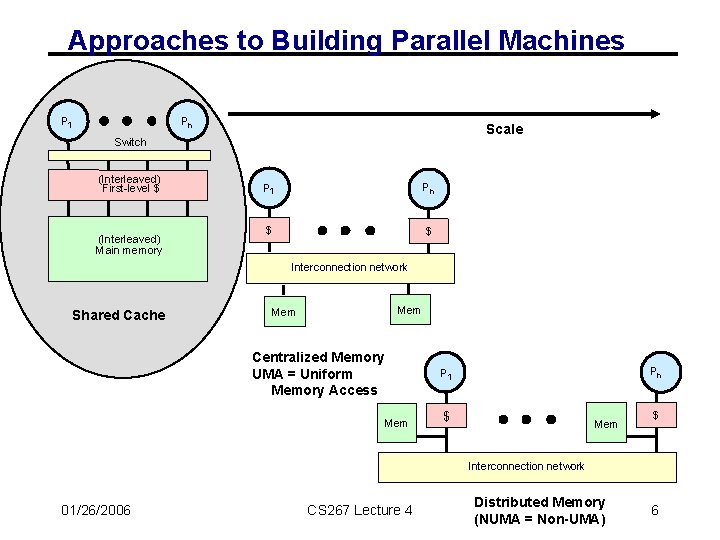

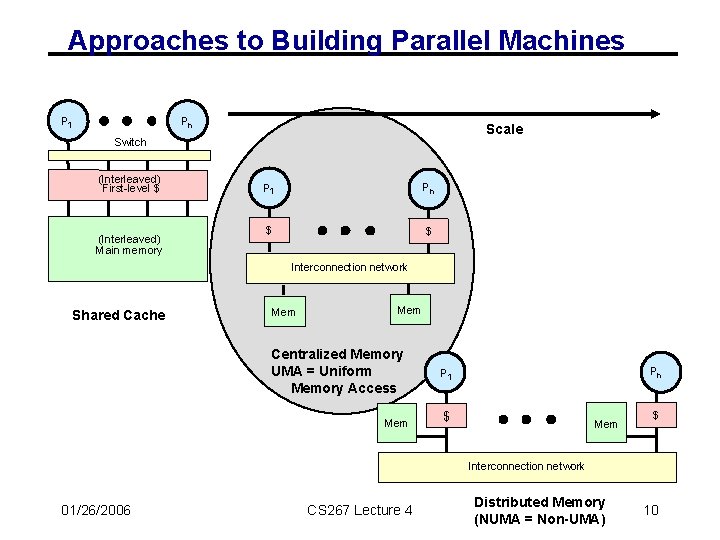

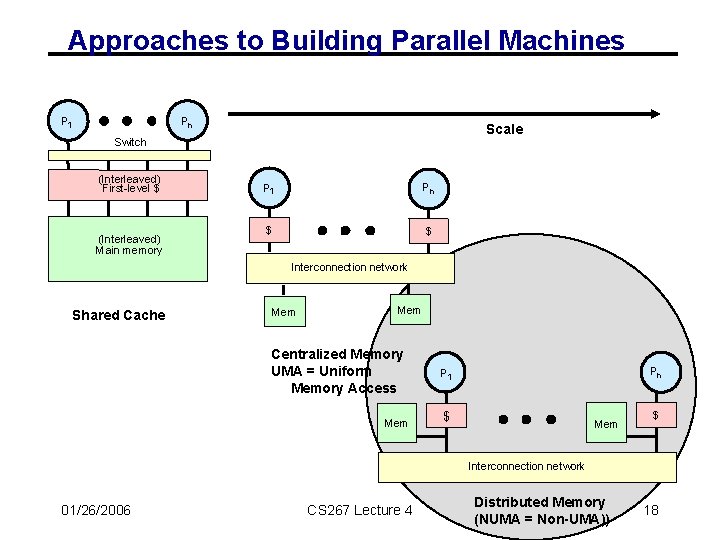

Approaches to Building Parallel Machines P 1 Pn Scale Switch (Interleaved) First-level $ (Interleaved) Main memory P 1 Pn $ $ Interconnection network Shared Cache Mem Centralized Memory UMA = Uniform Memory Access Mem Pn P 1 $ Mem $ Interconnection network 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 Distributed Memory (NUMA = Non-UMA) 6

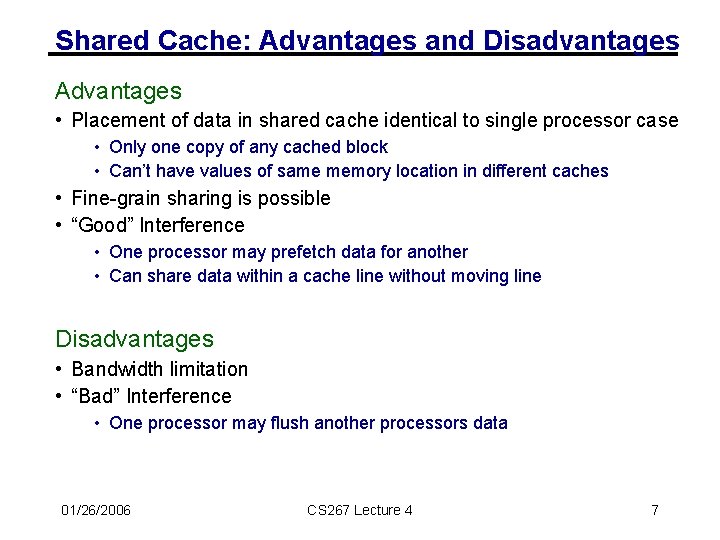

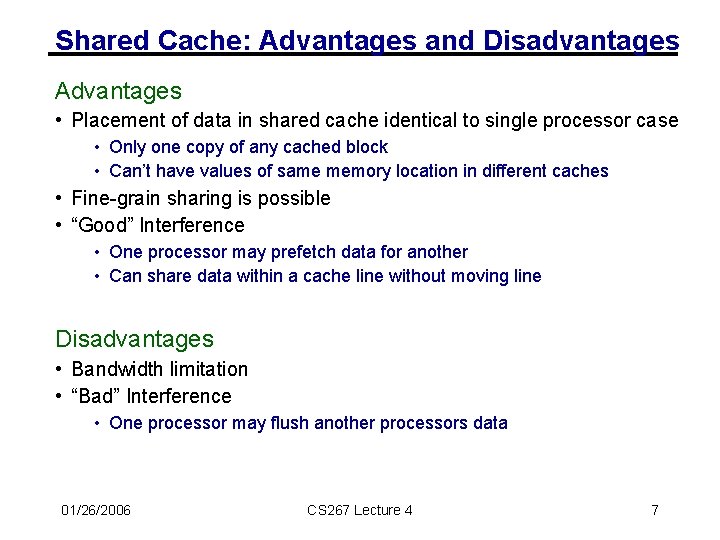

Shared Cache: Advantages and Disadvantages Advantages • Placement of data in shared cache identical to single processor case • Only one copy of any cached block • Can’t have values of same memory location in different caches • Fine-grain sharing is possible • “Good” Interference • One processor may prefetch data for another • Can share data within a cache line without moving line Disadvantages • Bandwidth limitation • “Bad” Interference • One processor may flush another processors data 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 7

Evolution of Shared Cache • Alliant FX-8 (early 1980 s) • eight 68020 s with x-bar to 512 KB interleaved cache • Encore & Sequent (1980 s) • first 32 -bit micros (N 32032) • two to a board with a shared cache • Disappeared for a while, and then … • Cray X 1 shares L 3 cache • IBM Power 4, Power 5, Blue. Gene nodes share L 2 cache • If switch and cache on chip, may have enough bandwidth again 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 9

Approaches to Building Parallel Machines P 1 Pn Scale Switch (Interleaved) First-level $ (Interleaved) Main memory P 1 Pn $ $ Interconnection network Shared Cache Mem Centralized Memory UMA = Uniform Memory Access Mem Pn P 1 $ Mem $ Interconnection network 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 Distributed Memory (NUMA = Non-UMA) 10

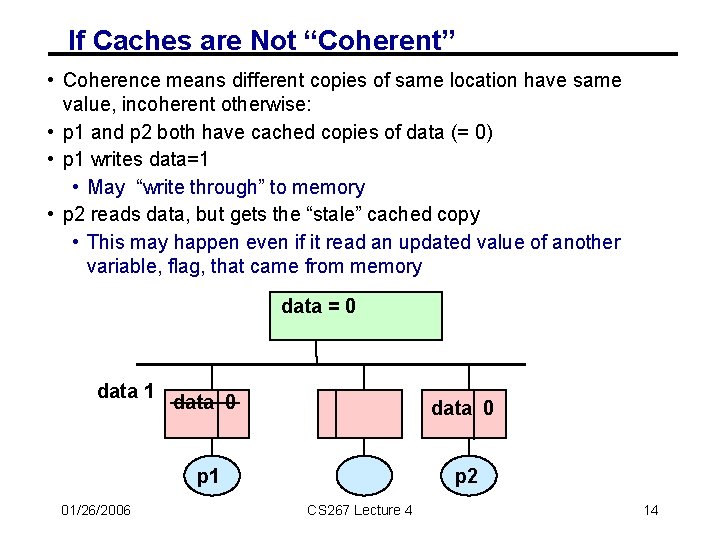

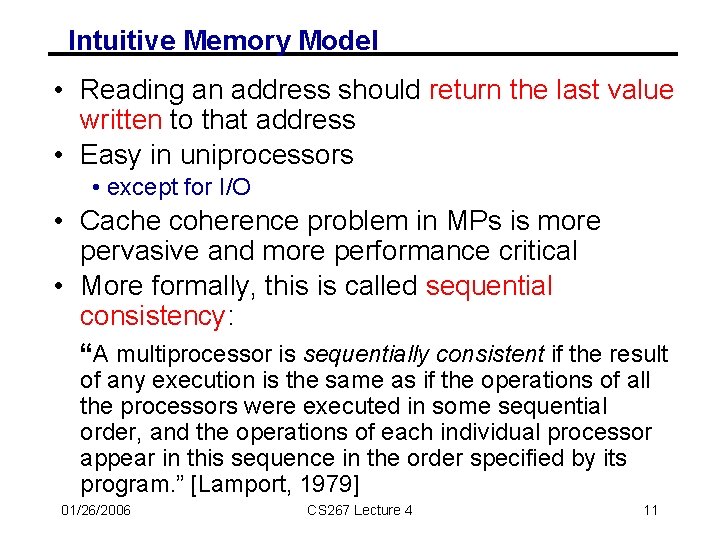

Intuitive Memory Model • Reading an address should return the last value written to that address • Easy in uniprocessors • except for I/O • Cache coherence problem in MPs is more pervasive and more performance critical • More formally, this is called sequential consistency: “A multiprocessor is sequentially consistent if the result of any execution is the same as if the operations of all the processors were executed in some sequential order, and the operations of each individual processor appear in this sequence in the order specified by its program. ” [Lamport, 1979] 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 11

Sequential Consistency Intuition • Sequential consistency says the machine behaves as if it does the following P 0 P 1 P 2 P 3 memory 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 12

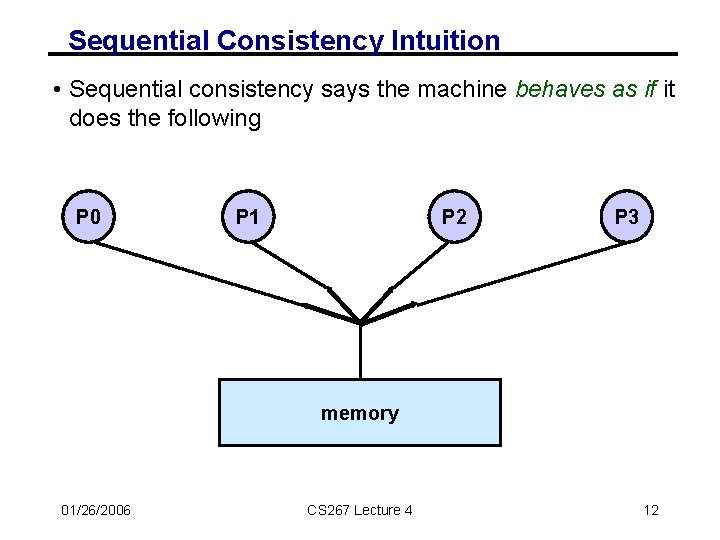

Memory Consistency Semantics What does this imply about program behavior? • No process ever sees “garbage” values, I. e. , average of 2 values • Processors always see values written by some processor • The value seen is constrained by program order on all processors If P 2 sees the new value of • Time always moves forward flag (=1), it must see the • Example: spin lock new value of data (=1) • P 1 writes data=1, then writes flag=1 • P 2 waits until flag=1, then reads data initially: P 1 data = 1 flag = 1 01/26/2006 flag=0 data=0 P 2 10: if flag=0, goto 10 …= data CS 267 Lecture 4 If P 2 Then P 2 may reads flag read data 0 1 0 0 1 1 13

If Caches are Not “Coherent” • Coherence means different copies of same location have same value, incoherent otherwise: • p 1 and p 2 both have cached copies of data (= 0) • p 1 writes data=1 • May “write through” to memory • p 2 reads data, but gets the “stale” cached copy • This may happen even if it read an updated value of another variable, flag, that came from memory data = 0 data 1 01/26/2006 data 0 p 1 p 2 CS 267 Lecture 4 14

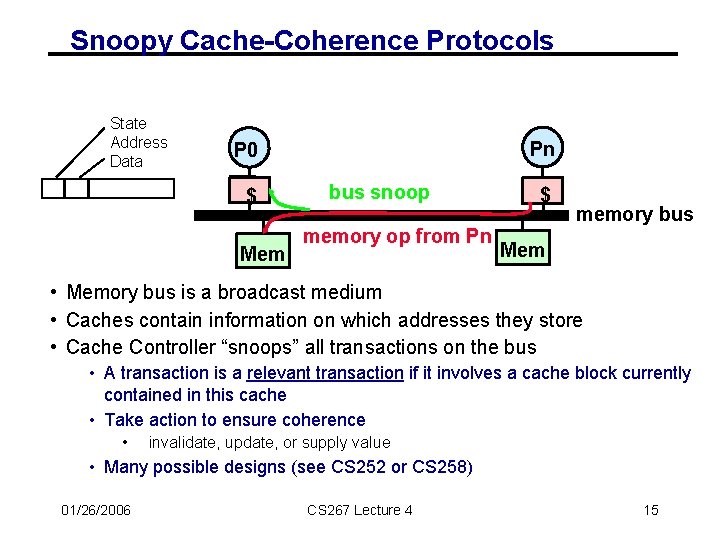

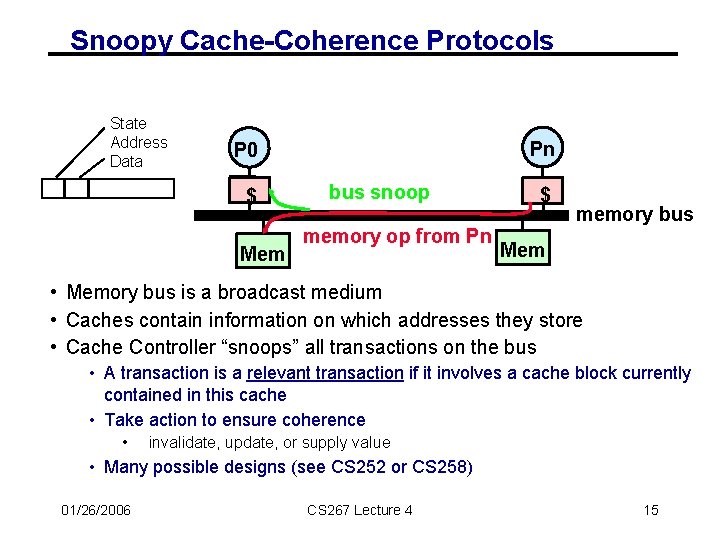

Snoopy Cache-Coherence Protocols State Address Data Pn P 0 $ Mem bus snoop memory op from Pn $ memory bus Mem • Memory bus is a broadcast medium • Caches contain information on which addresses they store • Cache Controller “snoops” all transactions on the bus • A transaction is a relevant transaction if it involves a cache block currently contained in this cache • Take action to ensure coherence • invalidate, update, or supply value • Many possible designs (see CS 252 or CS 258) 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 15

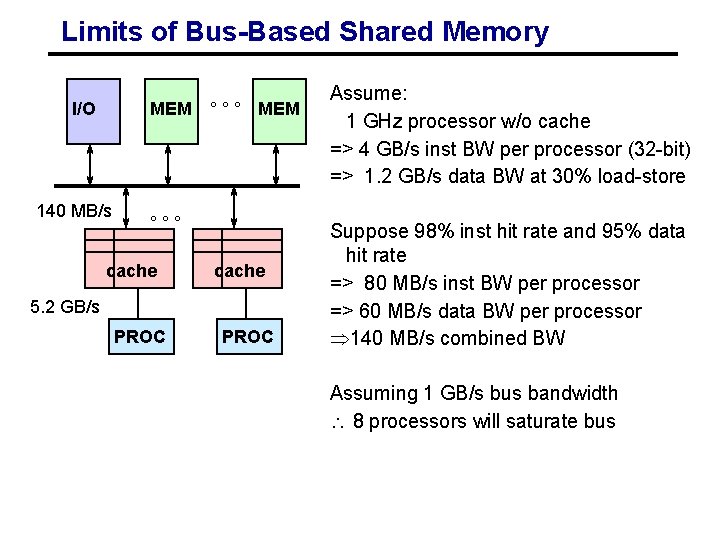

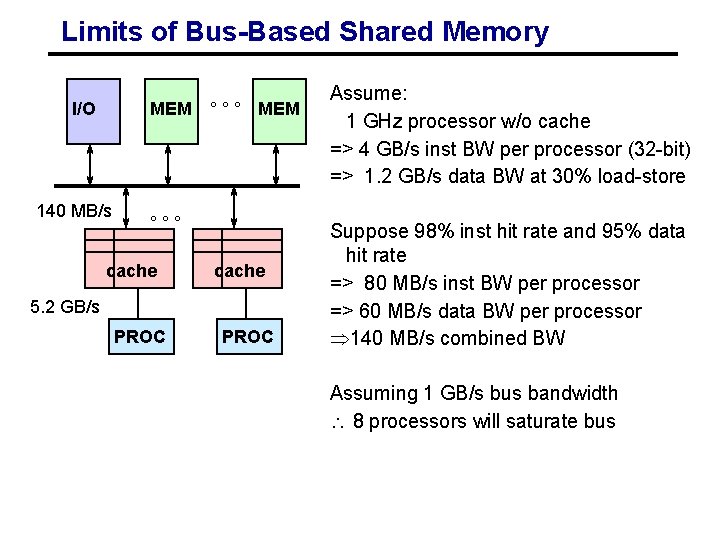

Limits of Bus-Based Shared Memory I/O MEM 140 MB/s ° ° ° MEM °°° cache 5. 2 GB/s PROC Assume: 1 GHz processor w/o cache => 4 GB/s inst BW per processor (32 -bit) => 1. 2 GB/s data BW at 30% load-store Suppose 98% inst hit rate and 95% data hit rate => 80 MB/s inst BW per processor => 60 MB/s data BW per processor 140 MB/s combined BW Assuming 1 GB/s bus bandwidth 8 processors will saturate bus

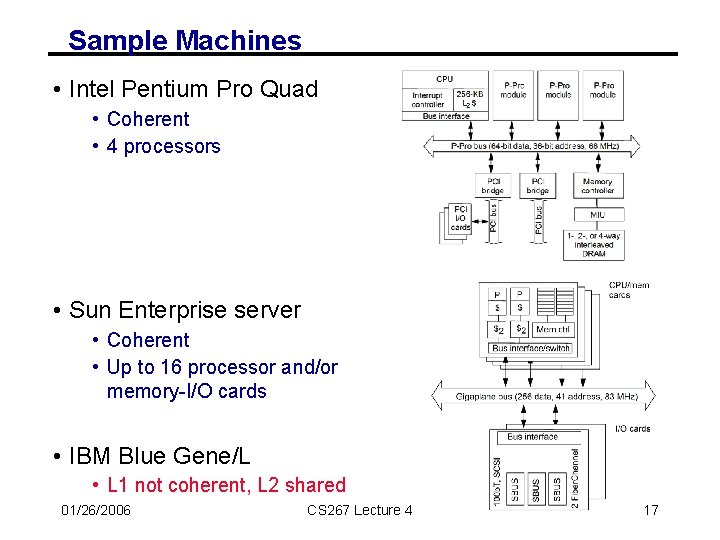

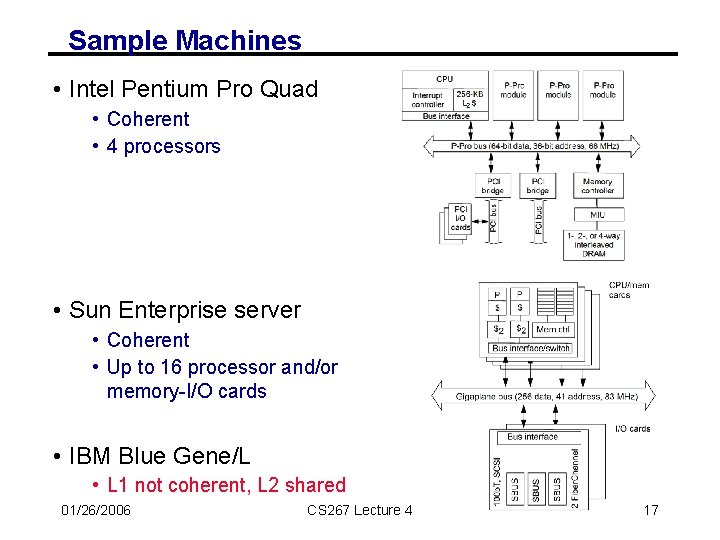

Sample Machines • Intel Pentium Pro Quad • Coherent • 4 processors • Sun Enterprise server • Coherent • Up to 16 processor and/or memory-I/O cards • IBM Blue Gene/L • L 1 not coherent, L 2 shared 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 17

Approaches to Building Parallel Machines P 1 Pn Scale Switch (Interleaved) First-level $ (Interleaved) Main memory P 1 Pn $ $ Interconnection network Shared Cache Mem Centralized Memory UMA = Uniform Memory Access Mem Pn P 1 $ Mem $ Interconnection network 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 Distributed Memory (NUMA = Non-UMA)) 18

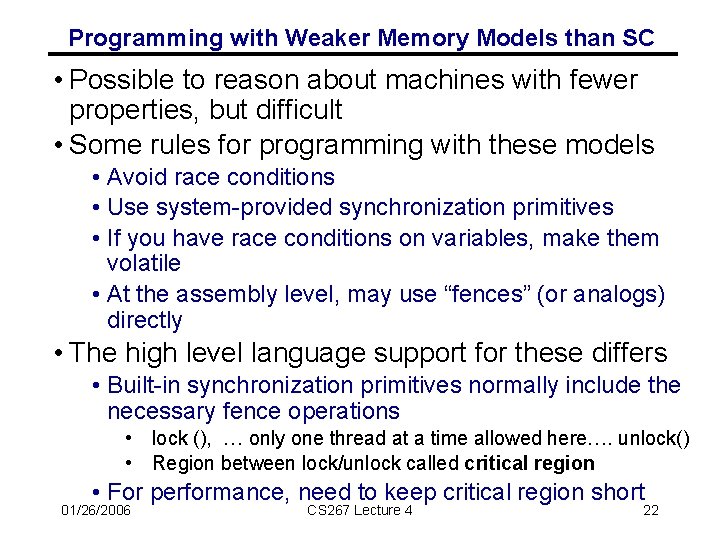

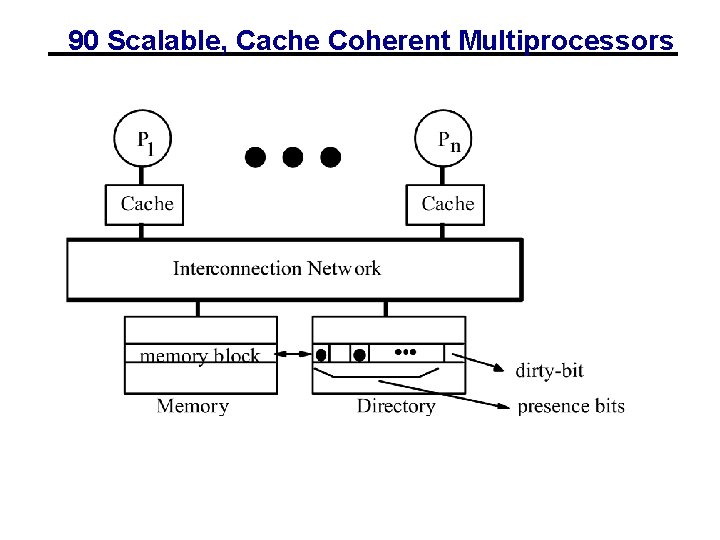

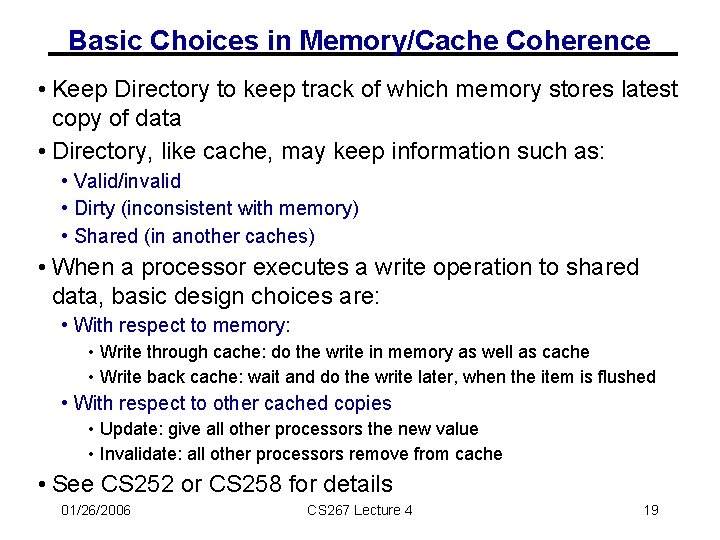

Basic Choices in Memory/Cache Coherence • Keep Directory to keep track of which memory stores latest copy of data • Directory, like cache, may keep information such as: • Valid/invalid • Dirty (inconsistent with memory) • Shared (in another caches) • When a processor executes a write operation to shared data, basic design choices are: • With respect to memory: • Write through cache: do the write in memory as well as cache • Write back cache: wait and do the write later, when the item is flushed • With respect to other cached copies • Update: give all other processors the new value • Invalidate: all other processors remove from cache • See CS 252 or CS 258 for details 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 19

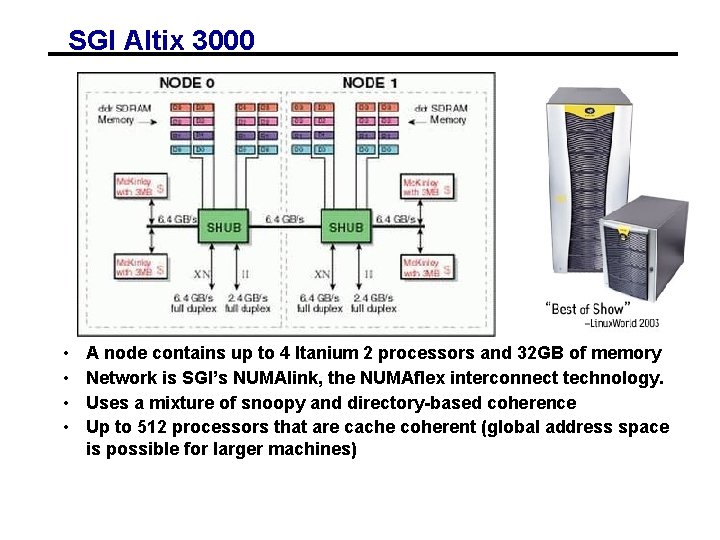

SGI Altix 3000 • • A node contains up to 4 Itanium 2 processors and 32 GB of memory Network is SGI’s NUMAlink, the NUMAflex interconnect technology. Uses a mixture of snoopy and directory-based coherence Up to 512 processors that are cache coherent (global address space is possible for larger machines)

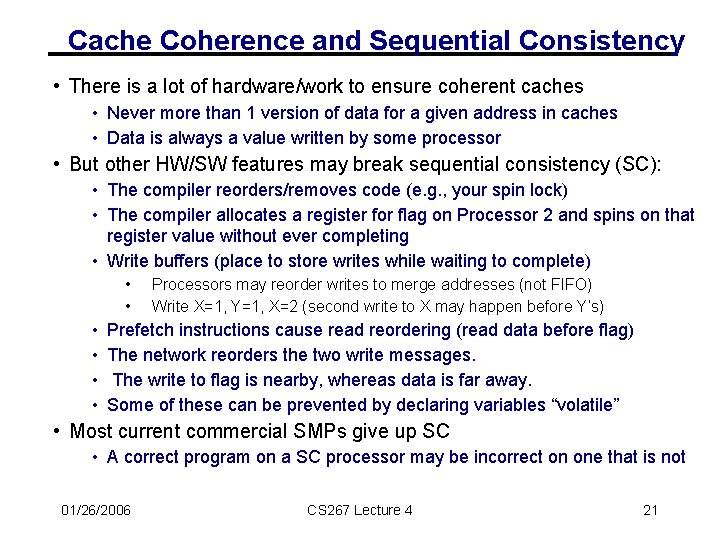

Cache Coherence and Sequential Consistency • There is a lot of hardware/work to ensure coherent caches • Never more than 1 version of data for a given address in caches • Data is always a value written by some processor • But other HW/SW features may break sequential consistency (SC): • The compiler reorders/removes code (e. g. , your spin lock) • The compiler allocates a register for flag on Processor 2 and spins on that register value without ever completing • Write buffers (place to store writes while waiting to complete) • • • Processors may reorder writes to merge addresses (not FIFO) Write X=1, Y=1, X=2 (second write to X may happen before Y’s) Prefetch instructions cause read reordering (read data before flag) The network reorders the two write messages. The write to flag is nearby, whereas data is far away. Some of these can be prevented by declaring variables “volatile” • Most current commercial SMPs give up SC • A correct program on a SC processor may be incorrect on one that is not 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 21

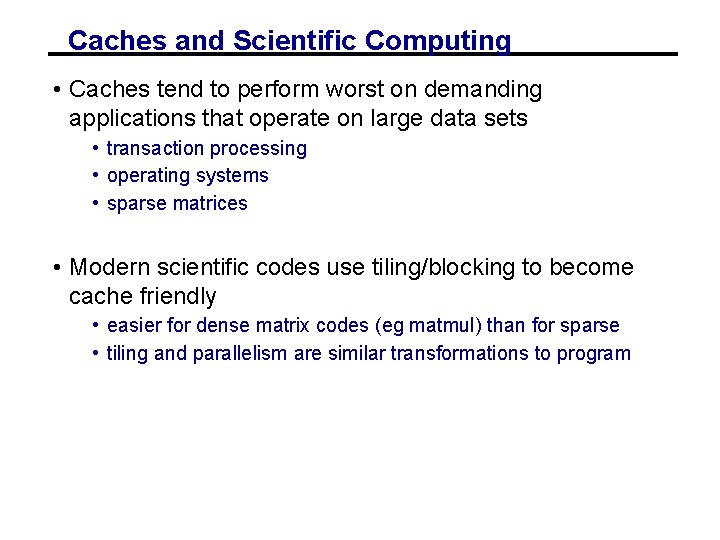

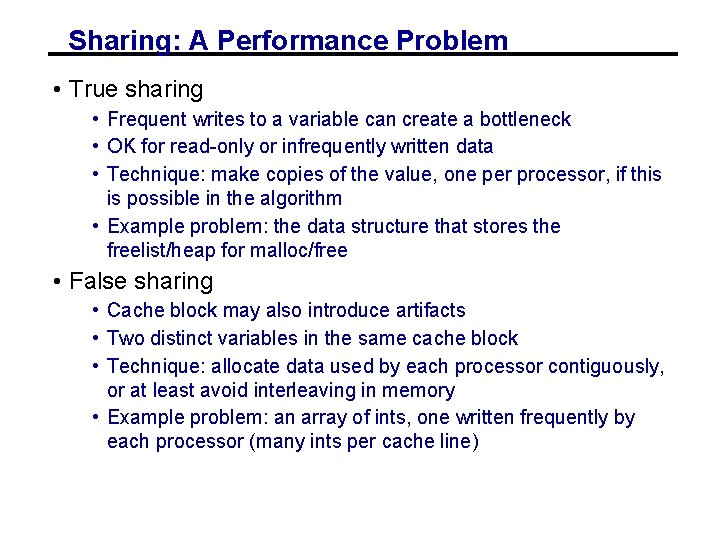

Programming with Weaker Memory Models than SC • Possible to reason about machines with fewer properties, but difficult • Some rules for programming with these models • Avoid race conditions • Use system-provided synchronization primitives • If you have race conditions on variables, make them volatile • At the assembly level, may use “fences” (or analogs) directly • The high level language support for these differs • Built-in synchronization primitives normally include the necessary fence operations • lock (), … only one thread at a time allowed here…. unlock() • Region between lock/unlock called critical region • For performance, need to keep critical region short 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 22

![Improved Code for Computing a Sum s fA0 fAn1 static Improved Code for Computing a Sum s = f(A[0]) + … + f(A[n-1]) static](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/ac720d992cedeb1d3257ea65b246b09b/image-22.jpg)

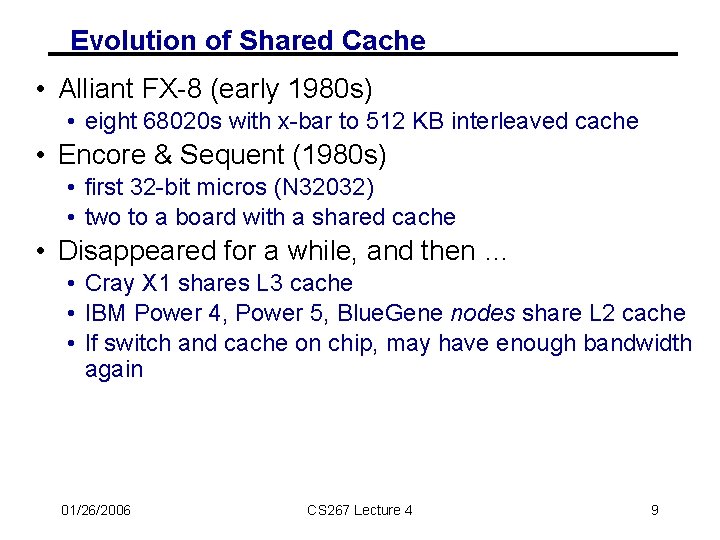

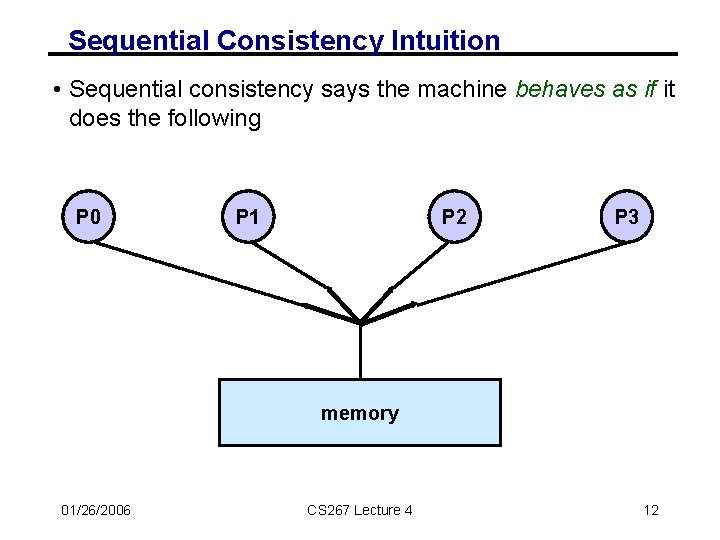

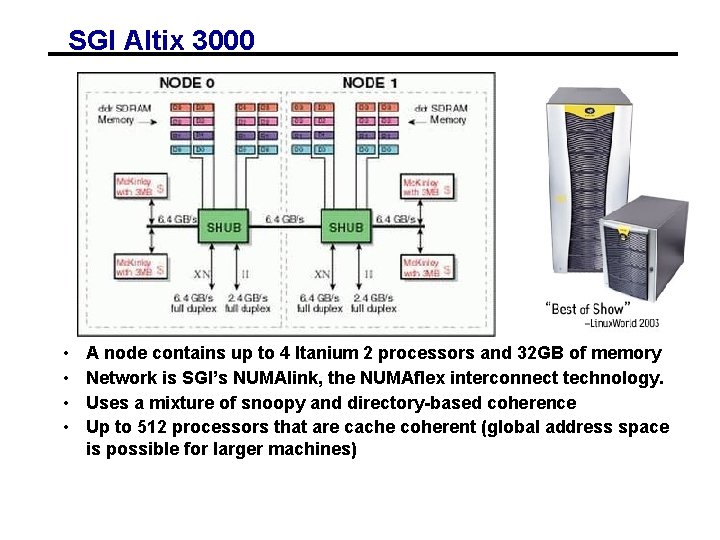

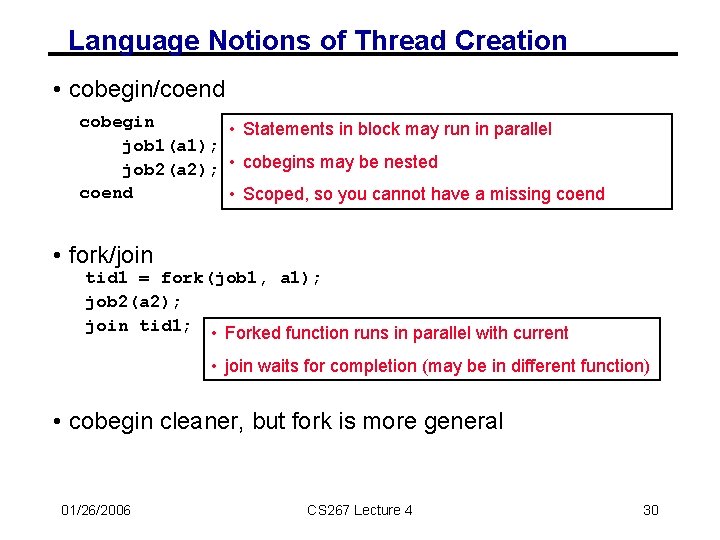

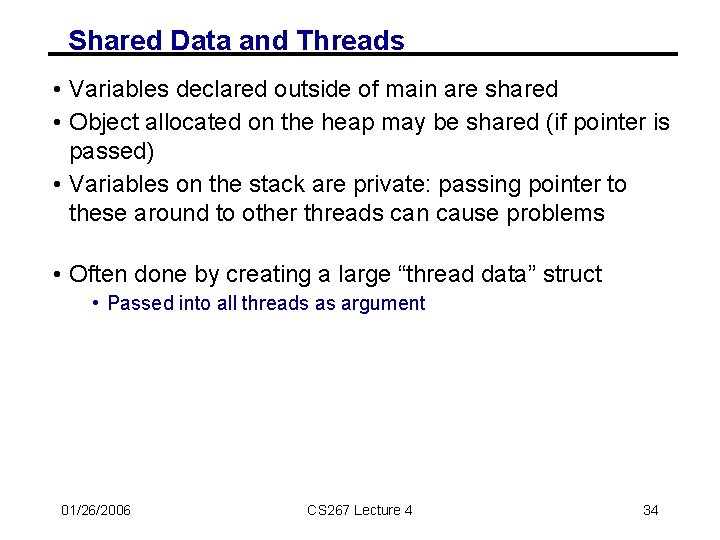

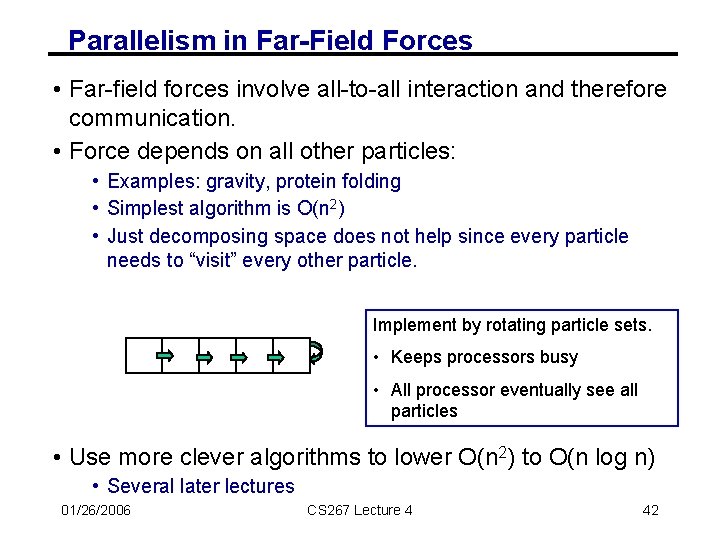

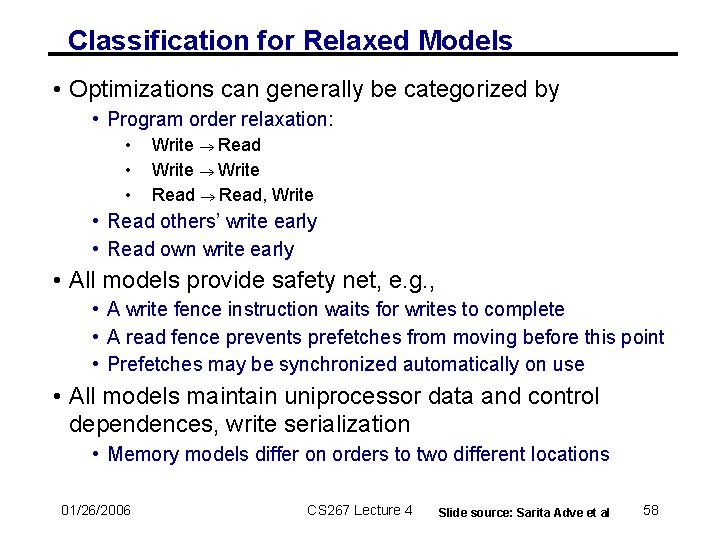

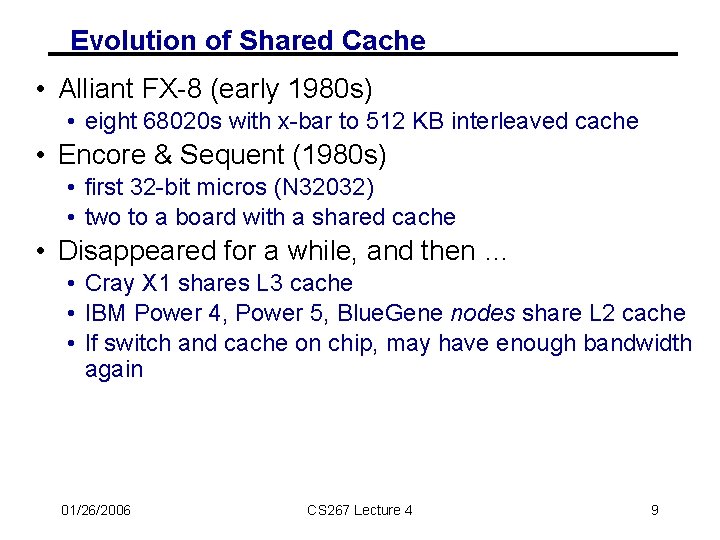

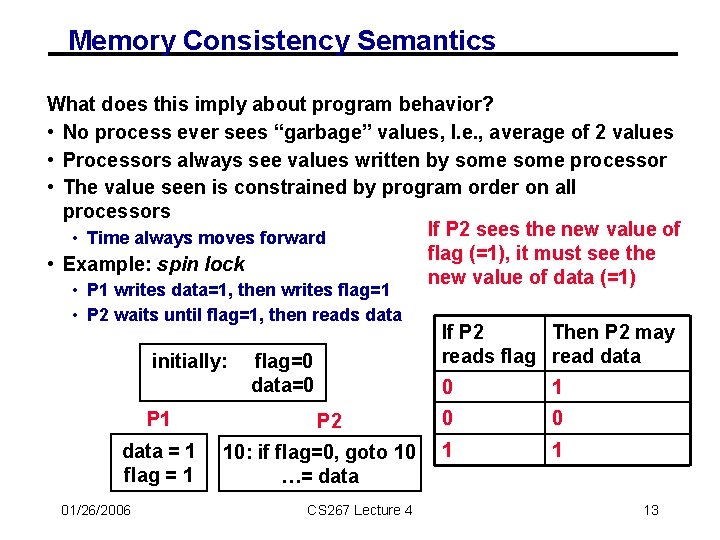

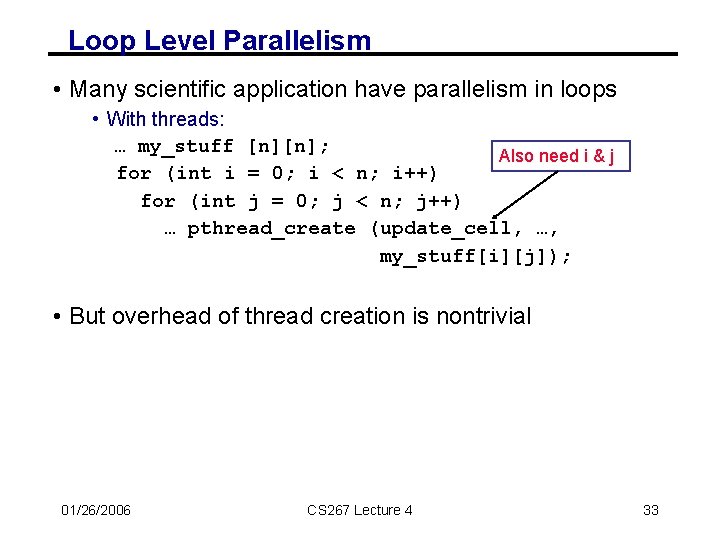

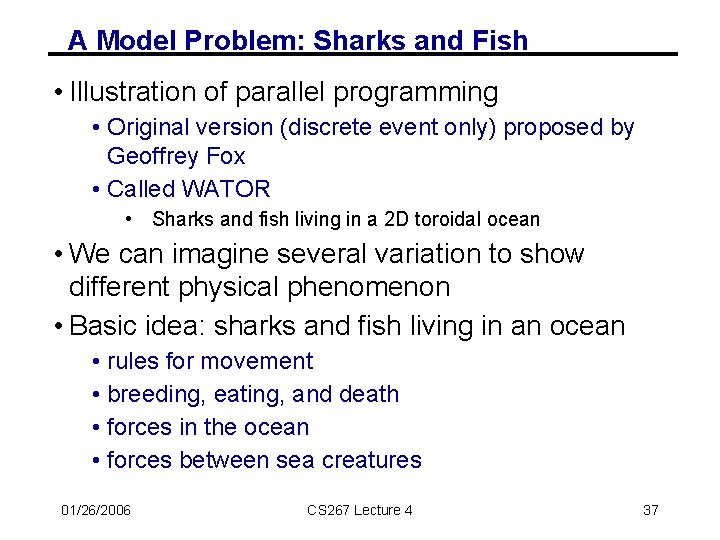

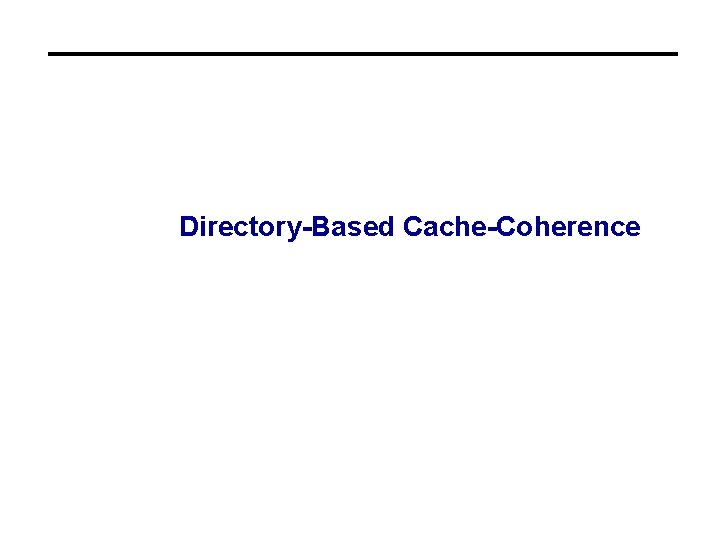

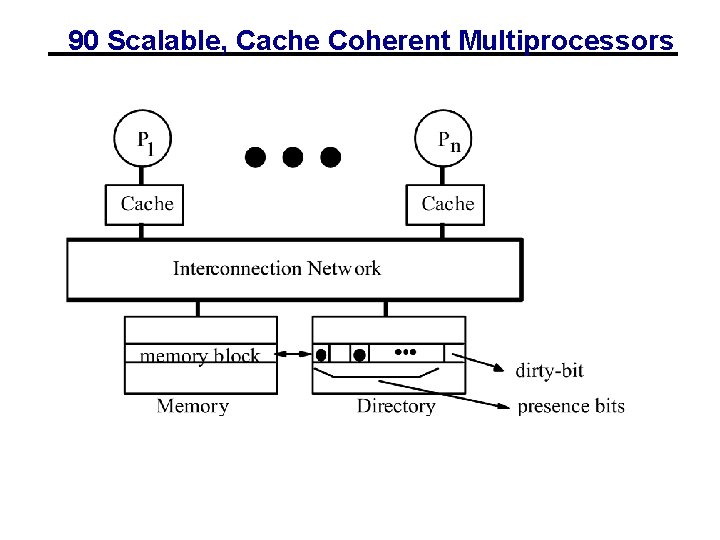

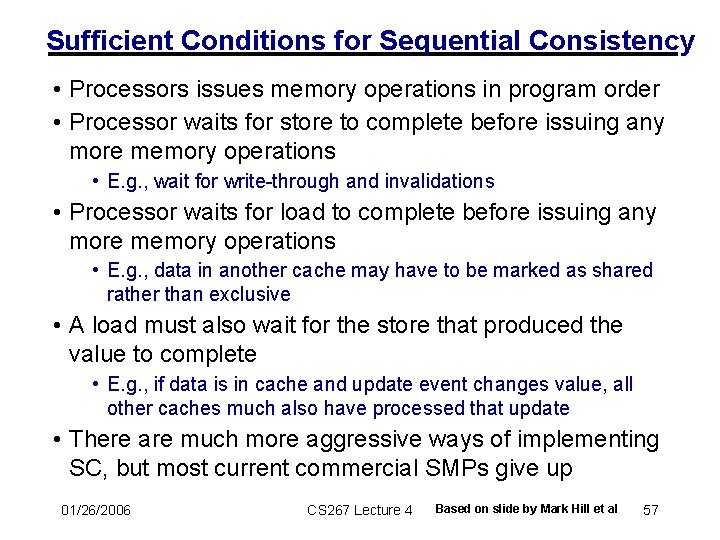

Improved Code for Computing a Sum s = f(A[0]) + … + f(A[n-1]) static int s = 0; static lock lk; Thread 1 lock(lk); local_s 1= 0 for i = 0, n/2 -1 local_s 1 = local_s 1 + f(A[i]) s = s + local_s 1 unlock(lk); Thread 2 lock(lk); local_s 2 = 0 for i = n/2, n-1 local_s 2= local_s 2 + f(A[i]) s = s +local_s 2 unlock(lk); • Since addition is associative, it’s OK to rearrange order 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 23

![Improved Code for Computing a Sum s fA0 fAn1 static Improved Code for Computing a Sum s = f(A[0]) + … + f(A[n-1]) static](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/ac720d992cedeb1d3257ea65b246b09b/image-23.jpg)

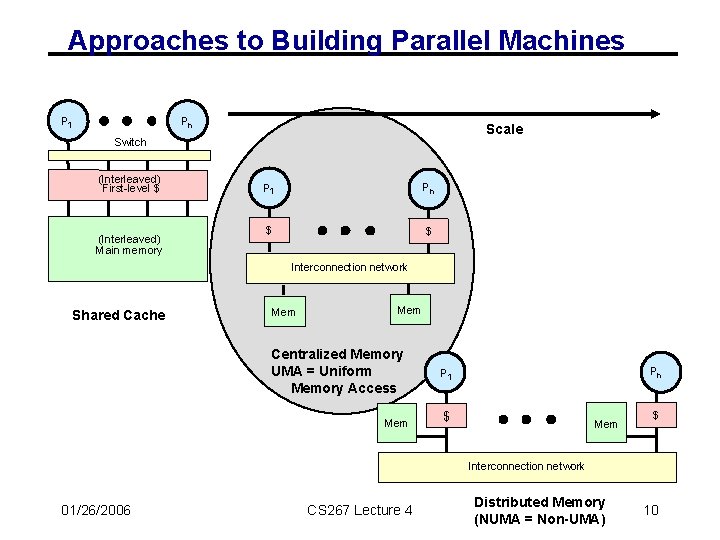

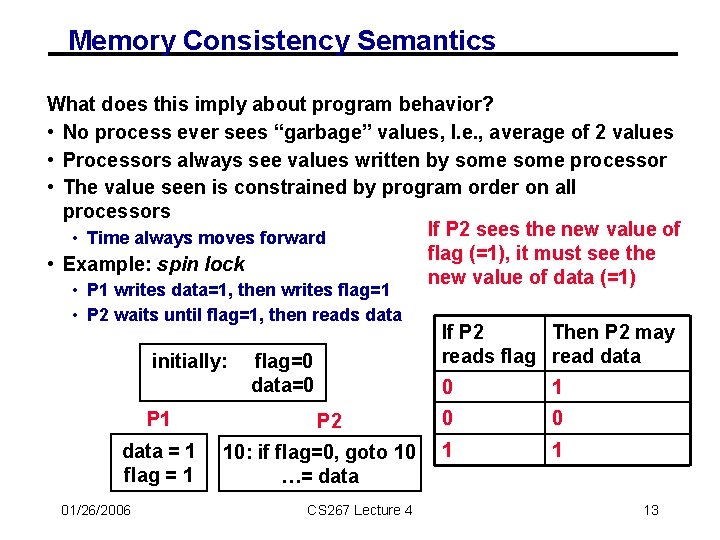

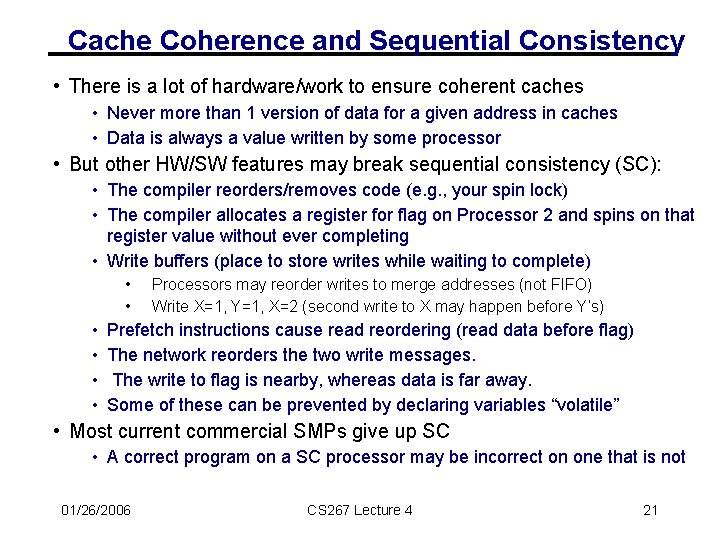

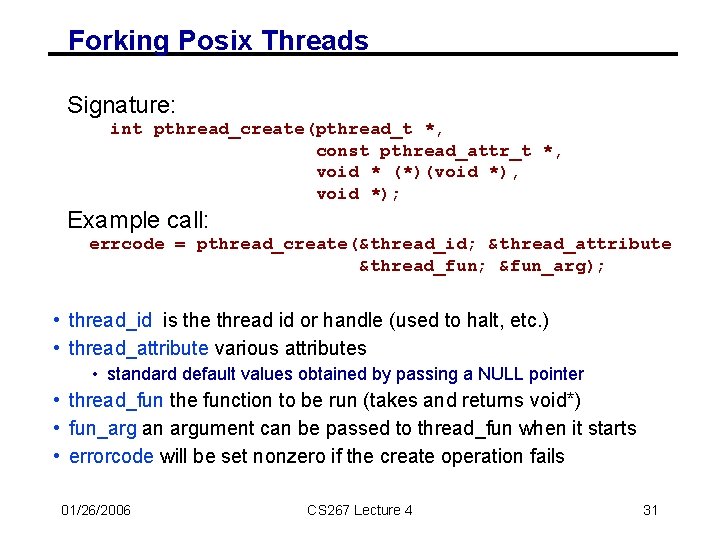

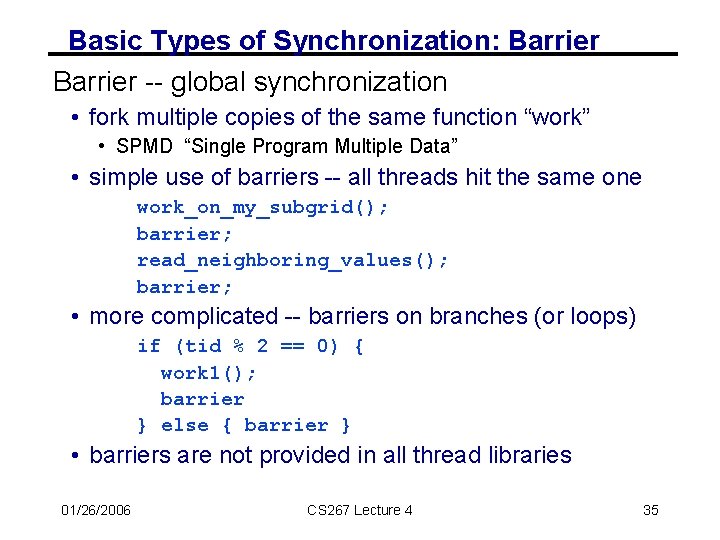

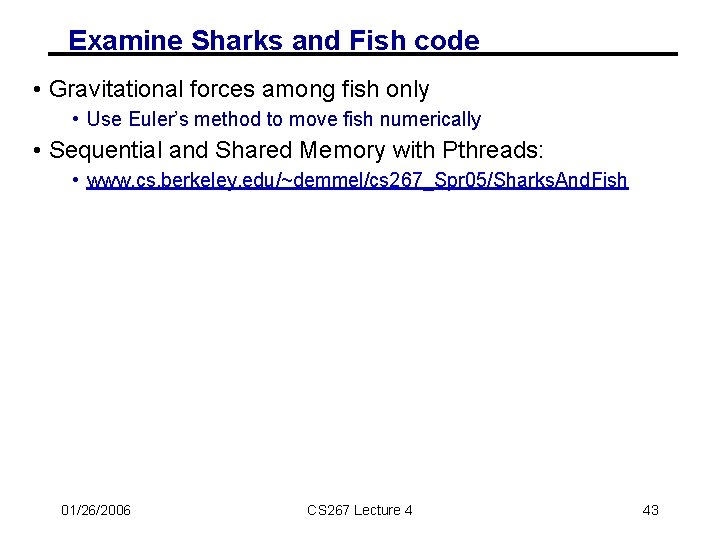

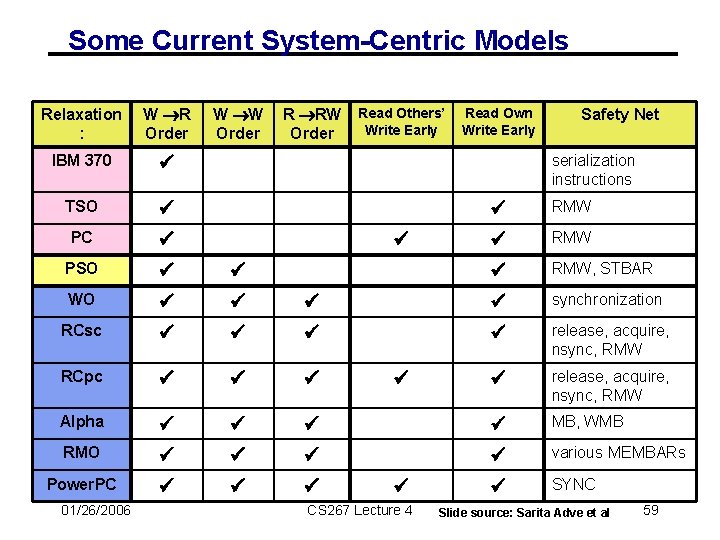

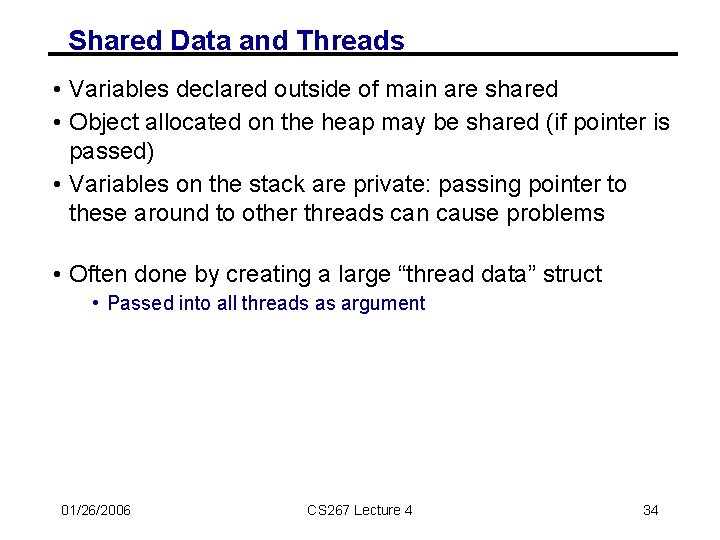

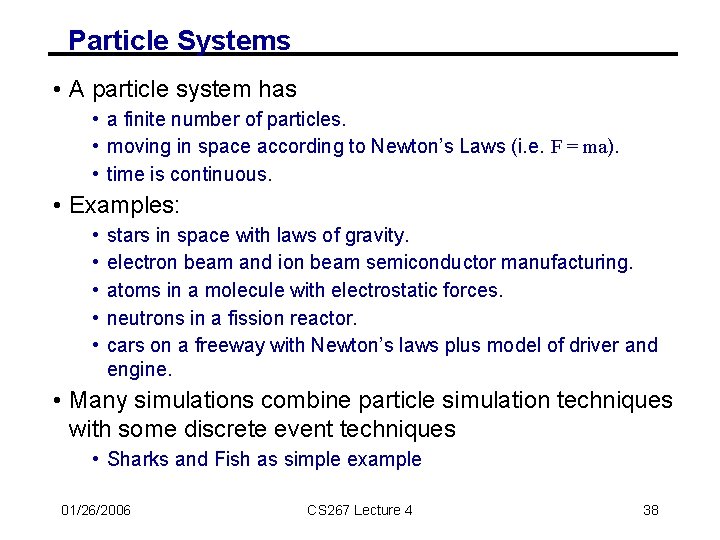

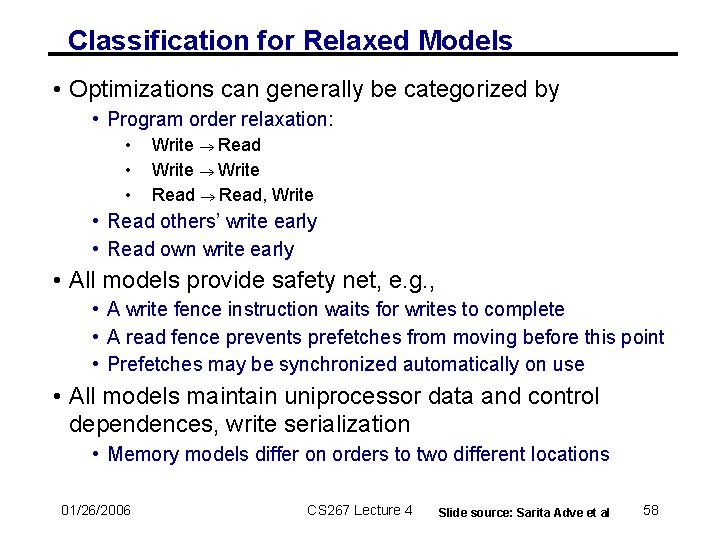

Improved Code for Computing a Sum s = f(A[0]) + … + f(A[n-1]) static int s = 0; static lock lk; Thread 1 Thread 2 local_s 1= 0 for i = 0, n/2 -1 local_s 1 = local_s 1 + f(A[i]) lock(lk); s = s + local_s 1 unlock(lk); local_s 2 = 0 for i = n/2, n-1 local_s 2= local_s 2 + f(A[i]) lock(lk); s = s +local_s 2 unlock(lk); • Since addition is associative, it’s OK to rearrange order • Critical section smaller • Most work outside it 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 24

Caches and Scientific Computing • Caches tend to perform worst on demanding applications that operate on large data sets • transaction processing • operating systems • sparse matrices • Modern scientific codes use tiling/blocking to become cache friendly • easier for dense matrix codes (eg matmul) than for sparse • tiling and parallelism are similar transformations to program

Sharing: A Performance Problem • True sharing • Frequent writes to a variable can create a bottleneck • OK for read-only or infrequently written data • Technique: make copies of the value, one per processor, if this is possible in the algorithm • Example problem: the data structure that stores the freelist/heap for malloc/free • False sharing • Cache block may also introduce artifacts • Two distinct variables in the same cache block • Technique: allocate data used by each processor contiguously, or at least avoid interleaving in memory • Example problem: an array of ints, one written frequently by each processor (many ints per cache line)

What to Take Away? • Programming shared memory machines • May allocate data in large shared region without too many worries about where • Memory hierarchy is critical to performance • Even more so than on uniprocessors, due to coherence traffic • For performance tuning, watch sharing (both true and false) • Semantics • Need to lock access to shared variable for read-modify-write • Sequential consistency is the natural semantics • Architects worked hard to make this work • • Caches are coherent with buses or directories No caching of remote data on shared address space machines • But compiler and processor may still get in the way • • 01/26/2006 Non-blocking writes, read prefetching, code motion… Avoid races or use machine-specific fences carefully CS 267 Lecture 4 27

Creating Parallelism with Threads 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 28

Programming with Threads Several Thread Libraries • PTHREADS is the Posix Standard • Solaris threads are very similar • Relatively low level • Portable but possibly slow • Open. MP is newer standard • Support for scientific programming on shared memory • http: //www. open. MP. org • P 4 (Parmacs) is an older portable package • Higher level than Pthreads • http: //www. netlib. org/p 4/index. html 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 29

Language Notions of Thread Creation • cobegin/coend cobegin • Statements in block may run in parallel job 1(a 1); job 2(a 2); • cobegins may be nested coend • Scoped, so you cannot have a missing coend • fork/join tid 1 = fork(job 1, a 1); job 2(a 2); join tid 1; • Forked function runs in parallel with current • join waits for completion (may be in different function) • cobegin cleaner, but fork is more general 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 30

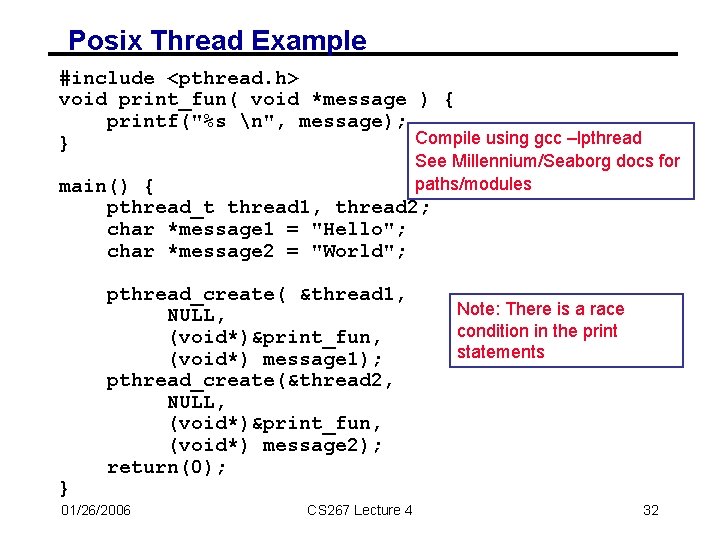

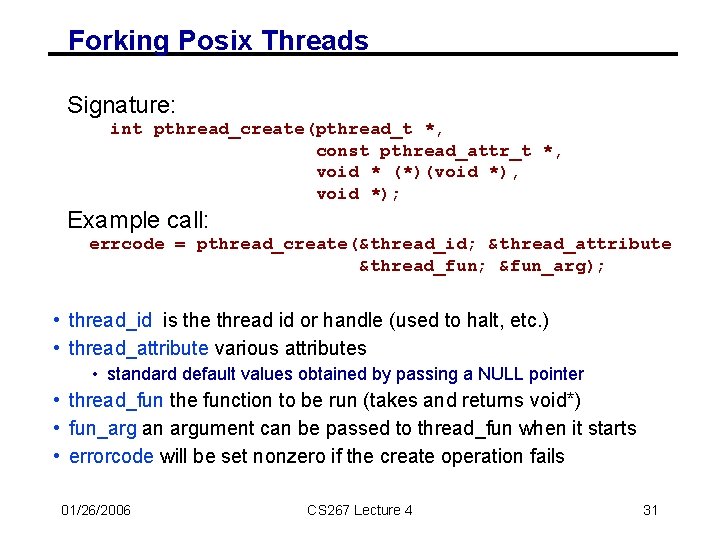

Forking Posix Threads Signature: int pthread_create(pthread_t *, const pthread_attr_t *, void * (*)(void *), void *); Example call: errcode = pthread_create(&thread_id; &thread_attribute &thread_fun; &fun_arg); • thread_id is the thread id or handle (used to halt, etc. ) • thread_attribute various attributes • standard default values obtained by passing a NULL pointer • thread_fun the function to be run (takes and returns void*) • fun_arg an argument can be passed to thread_fun when it starts • errorcode will be set nonzero if the create operation fails 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 31

Posix Thread Example #include <pthread. h> void print_fun( void *message ) { printf("%s n", message); Compile using gcc –lpthread } See Millennium/Seaborg docs for paths/modules main() { pthread_t thread 1, thread 2; char *message 1 = "Hello"; char *message 2 = "World"; } pthread_create( &thread 1, NULL, (void*)&print_fun, (void*) message 1); pthread_create(&thread 2, NULL, (void*)&print_fun, (void*) message 2); return(0); 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 Note: There is a race condition in the print statements 32

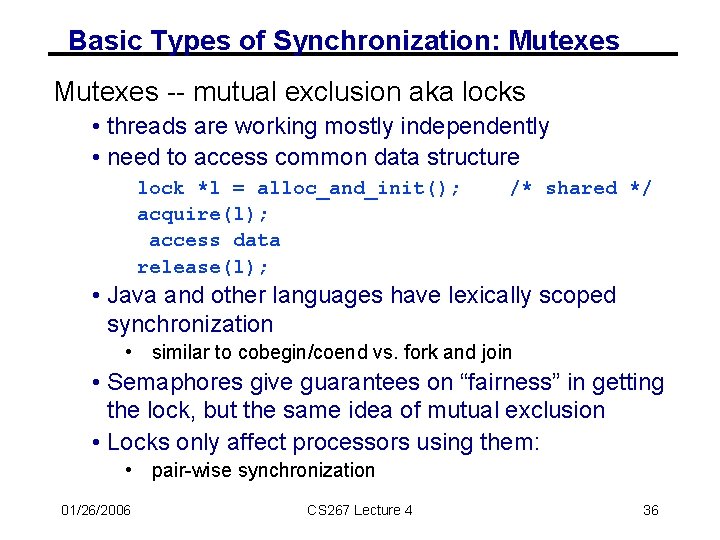

Loop Level Parallelism • Many scientific application have parallelism in loops • With threads: … my_stuff [n][n]; Also need i & j for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) for (int j = 0; j < n; j++) … pthread_create (update_cell, …, my_stuff[i][j]); • But overhead of thread creation is nontrivial 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 33

Shared Data and Threads • Variables declared outside of main are shared • Object allocated on the heap may be shared (if pointer is passed) • Variables on the stack are private: passing pointer to these around to other threads can cause problems • Often done by creating a large “thread data” struct • Passed into all threads as argument 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 34

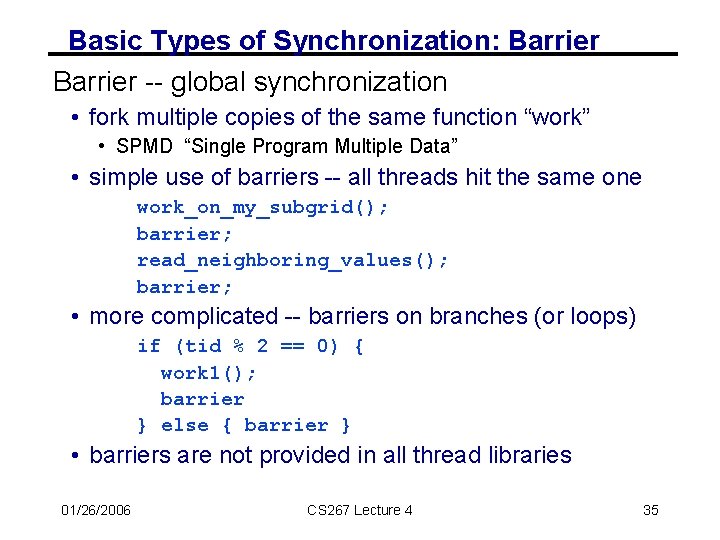

Basic Types of Synchronization: Barrier -- global synchronization • fork multiple copies of the same function “work” • SPMD “Single Program Multiple Data” • simple use of barriers -- all threads hit the same one work_on_my_subgrid(); barrier; read_neighboring_values(); barrier; • more complicated -- barriers on branches (or loops) if (tid % 2 == 0) { work 1(); barrier } else { barrier } • barriers are not provided in all thread libraries 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 35

Basic Types of Synchronization: Mutexes -- mutual exclusion aka locks • threads are working mostly independently • need to access common data structure lock *l = alloc_and_init(); acquire(l); access data release(l); /* shared */ • Java and other languages have lexically scoped synchronization • similar to cobegin/coend vs. fork and join • Semaphores give guarantees on “fairness” in getting the lock, but the same idea of mutual exclusion • Locks only affect processors using them: • pair-wise synchronization 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 36

A Model Problem: Sharks and Fish • Illustration of parallel programming • Original version (discrete event only) proposed by Geoffrey Fox • Called WATOR • Sharks and fish living in a 2 D toroidal ocean • We can imagine several variation to show different physical phenomenon • Basic idea: sharks and fish living in an ocean • rules for movement • breeding, eating, and death • forces in the ocean • forces between sea creatures 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 37

Particle Systems • A particle system has • a finite number of particles. • moving in space according to Newton’s Laws (i. e. F = ma). • time is continuous. • Examples: • • • stars in space with laws of gravity. electron beam and ion beam semiconductor manufacturing. atoms in a molecule with electrostatic forces. neutrons in a fission reactor. cars on a freeway with Newton’s laws plus model of driver and engine. • Many simulations combine particle simulation techniques with some discrete event techniques • Sharks and Fish as simple example 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 38

Forces in Particle Systems • Force on each particle decomposed into near and far: force = external_force + nearby_force + far_field_force • External force • ocean current in sharks and fish • externally imposed electric field in electron beam. • Nearby force • sharks attracted to eat nearby fish • balls on a billiard table bounce off of each other. • Van der Waals forces in fluid (1/r 6). • Far-field force • fish attract other fish by gravity-like (1/r 2 ) force • gravity, electrostatics • forces governed by elliptic PDE. 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 39

Parallelism in External Forces • External forces are the simplest to implement. • The force on each particle is independent of other particles. • Called “embarrassingly parallel”. • Evenly distribute particles on processors • Any even distribution works. • Locality is not an issue, no communication. • For each particle on processor, apply the external force. 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 40

Parallelism in Nearby Forces • Nearby forces require interaction and therefore communication. • Force may depend on other nearby particles: • Example: collisions. • simplest algorithm is O(n 2): look at all pairs to see if they collide. • Usual parallel model is decomposition of physical domain: • O(n 2/p) particles per processor if evenly distributed. • Often called domain decomposition (which also refers to numerical alg. ) • Challenges: • Dealing with particles near processor boundaries • Dealing with load imbalance from nonuniformly distributed particles Need to check for collisions between regions 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 41

Parallelism in Far-Field Forces • Far-field forces involve all-to-all interaction and therefore communication. • Force depends on all other particles: • Examples: gravity, protein folding • Simplest algorithm is O(n 2) • Just decomposing space does not help since every particle needs to “visit” every other particle. Implement by rotating particle sets. • Keeps processors busy • All processor eventually see all particles • Use more clever algorithms to lower O(n 2) to O(n log n) • Several later lectures 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 42

Examine Sharks and Fish code • Gravitational forces among fish only • Use Euler’s method to move fish numerically • Sequential and Shared Memory with Pthreads: • www. cs. berkeley. edu/~demmel/cs 267_Spr 05/Sharks. And. Fish 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 43

Extra Slides 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 44

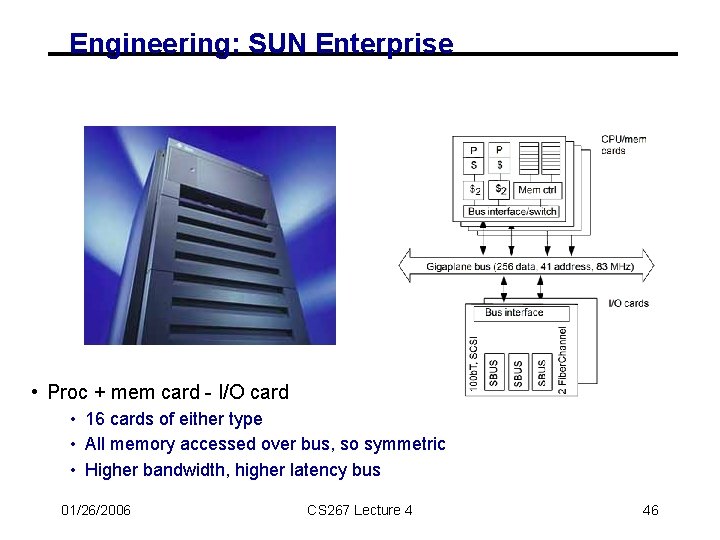

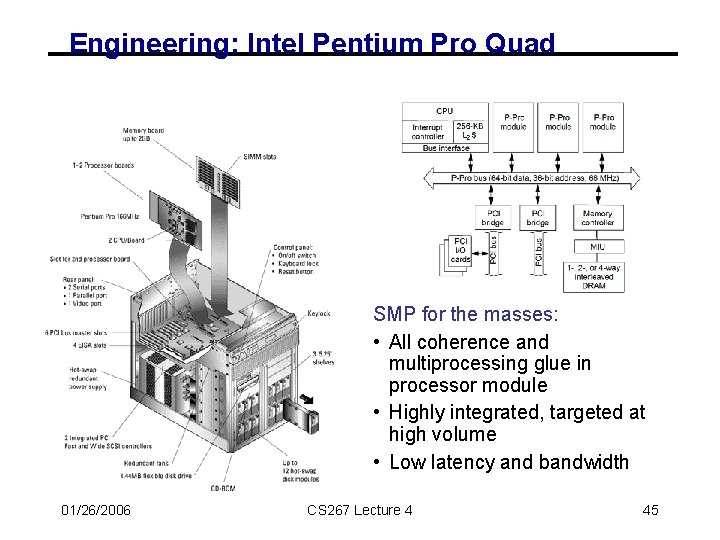

Engineering: Intel Pentium Pro Quad SMP for the masses: • All coherence and multiprocessing glue in processor module • Highly integrated, targeted at high volume • Low latency and bandwidth 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 45

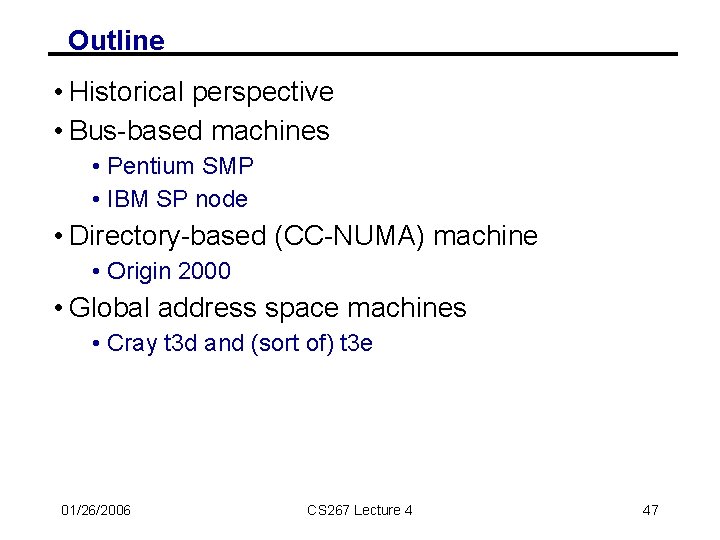

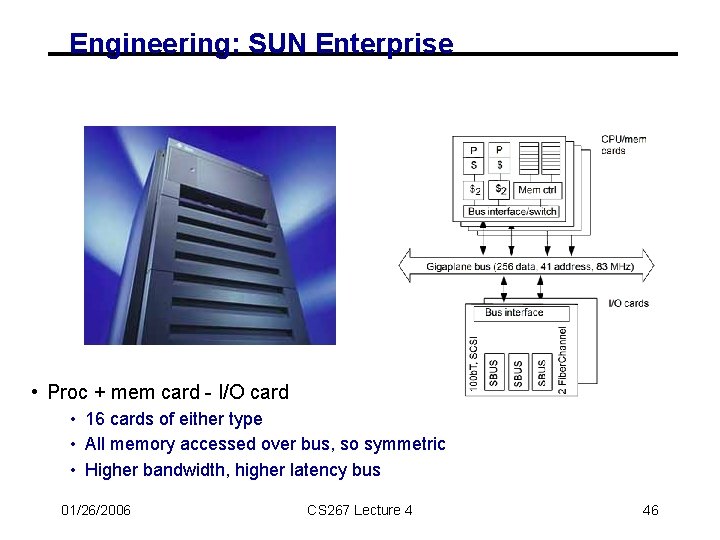

Engineering: SUN Enterprise • Proc + mem card - I/O card • 16 cards of either type • All memory accessed over bus, so symmetric • Higher bandwidth, higher latency bus 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 46

Outline • Historical perspective • Bus-based machines • Pentium SMP • IBM SP node • Directory-based (CC-NUMA) machine • Origin 2000 • Global address space machines • Cray t 3 d and (sort of) t 3 e 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 47

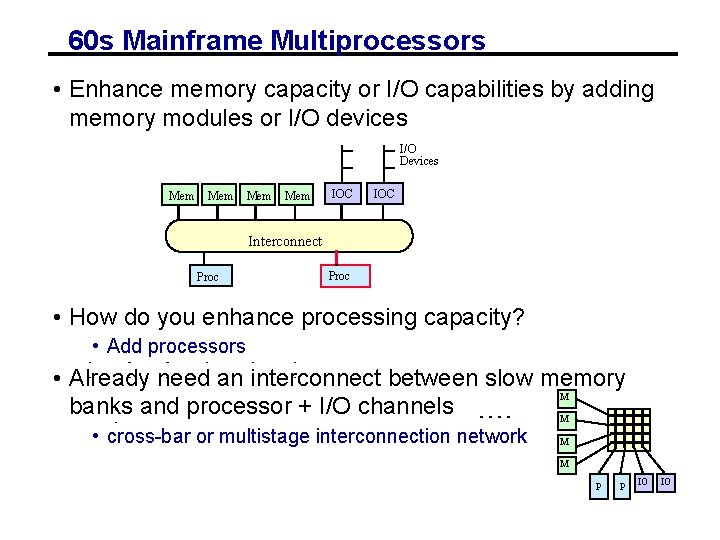

60 s Mainframe Multiprocessors • Enhance memory capacity or I/O capabilities by adding memory modules or I/O devices I/O Devices Mem Mem IOC Interconnect Proc • How do you enhance processing capacity? • Add processors • Already need an interconnect between slow memory M banks and processor + I/O channels M • cross-bar or multistage interconnection network M M P P IO IO

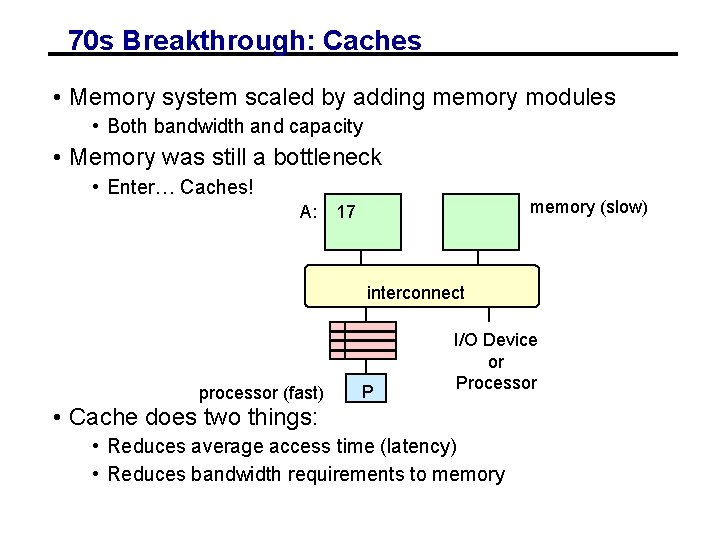

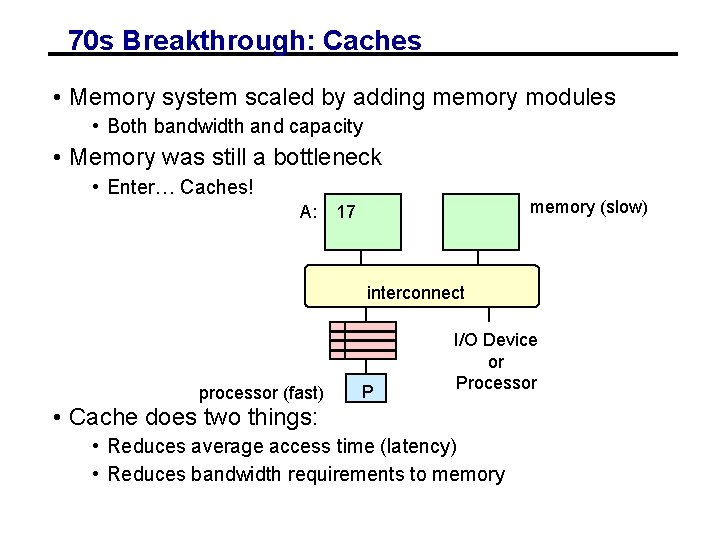

70 s Breakthrough: Caches • Memory system scaled by adding memory modules • Both bandwidth and capacity • Memory was still a bottleneck • Enter… Caches! A: memory (slow) 17 interconnect processor (fast) P I/O Device or Processor • Cache does two things: • Reduces average access time (latency) • Reduces bandwidth requirements to memory

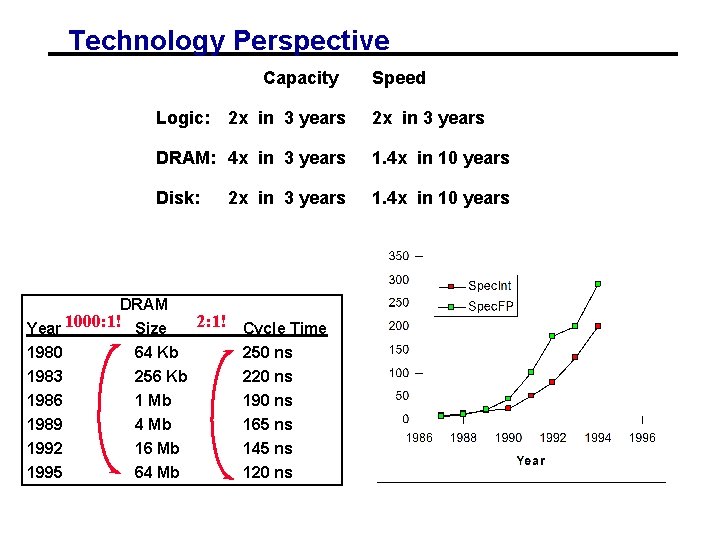

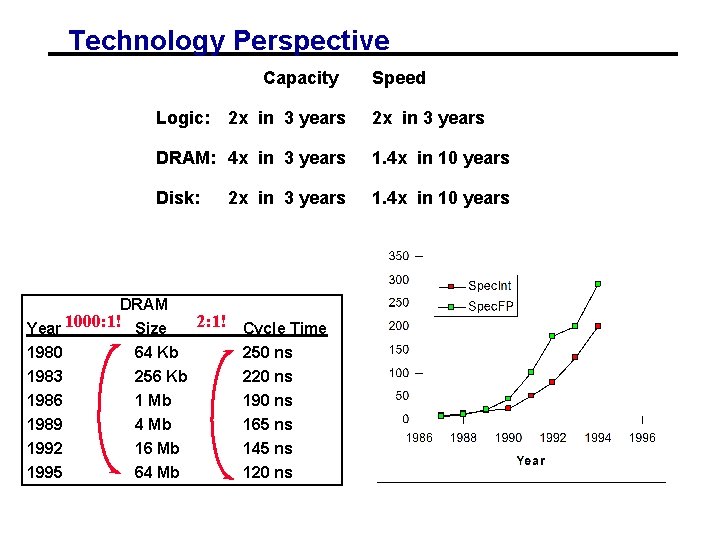

Technology Perspective Capacity Logic: 2 x in 3 years DRAM: 4 x in 3 years 1. 4 x in 10 years Disk: 1. 4 x in 10 years DRAM Year 1000: 1! Size 1980 1983 1986 1989 1992 1995 2 x in 3 years Speed 64 Kb 256 Kb 1 Mb 4 Mb 16 Mb 64 Mb 2 x in 3 years 2: 1! Cycle Time 250 ns 220 ns 190 ns 165 ns 145 ns 120 ns

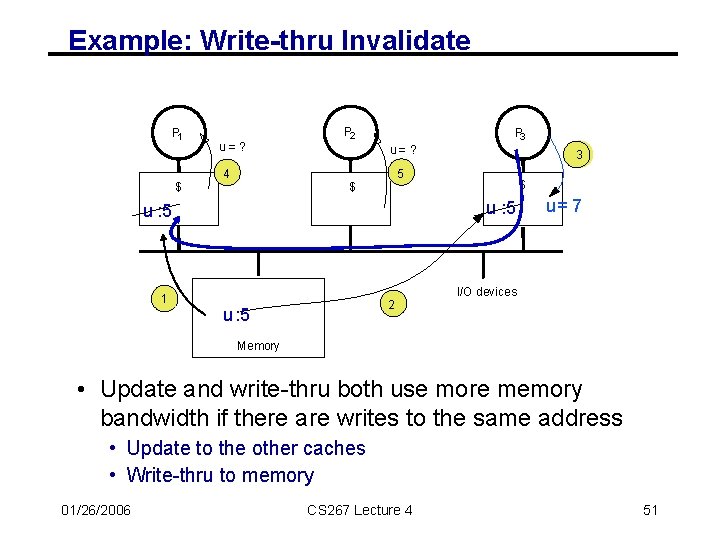

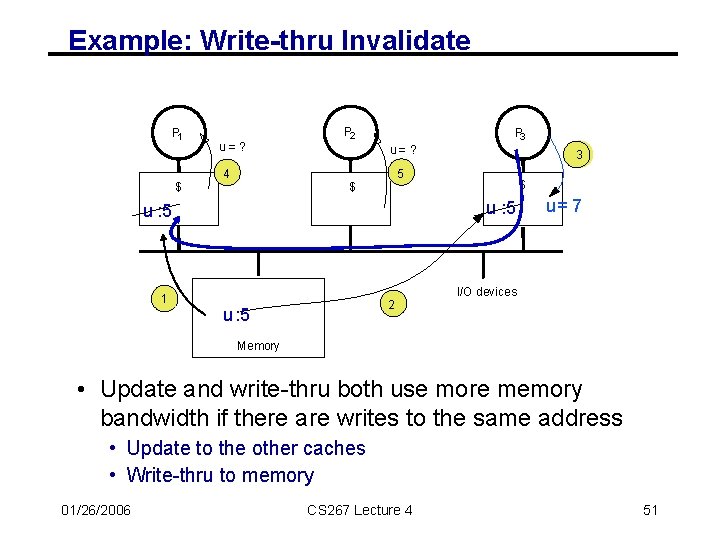

Example: Write-thru Invalidate P 1 $ u=? 4 P 2 P 3 u=? 5 $ $ u : 5 1 3 2 u : 5 u= 7 I/O devices Memory • Update and write-thru both use more memory bandwidth if there are writes to the same address • Update to the other caches • Write-thru to memory 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 51

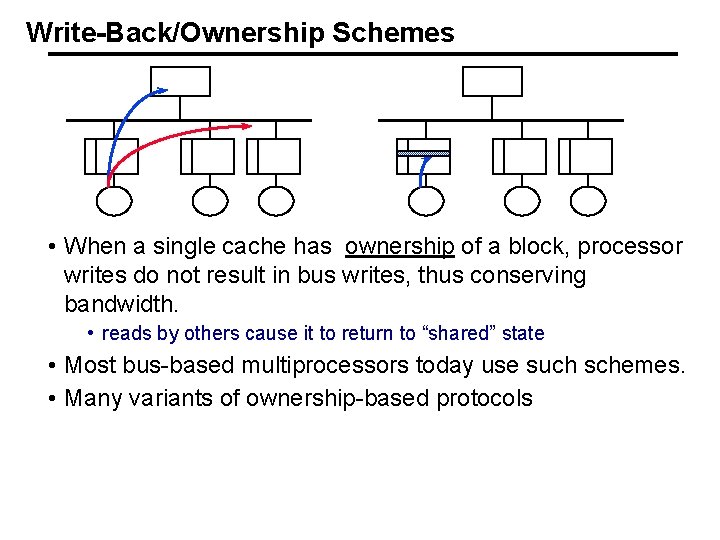

Write-Back/Ownership Schemes • When a single cache has ownership of a block, processor writes do not result in bus writes, thus conserving bandwidth. • reads by others cause it to return to “shared” state • Most bus-based multiprocessors today use such schemes. • Many variants of ownership-based protocols

Directory-Based Cache-Coherence

90 Scalable, Cache Coherent Multiprocessors

Cache Coherence and Memory Consistency

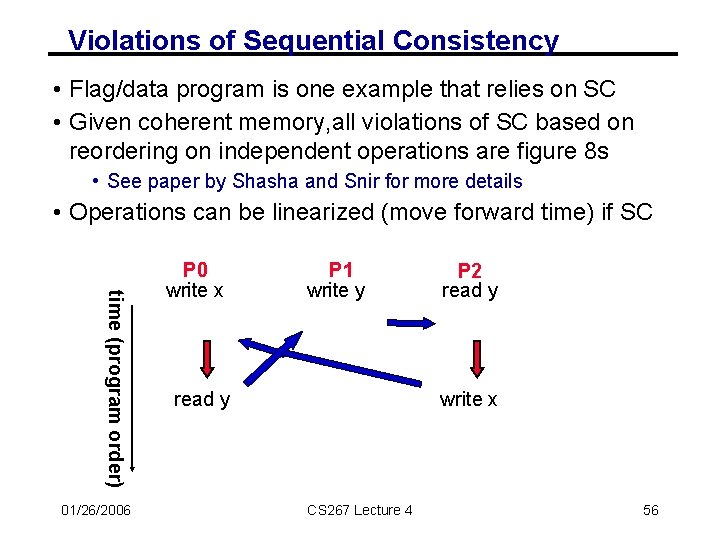

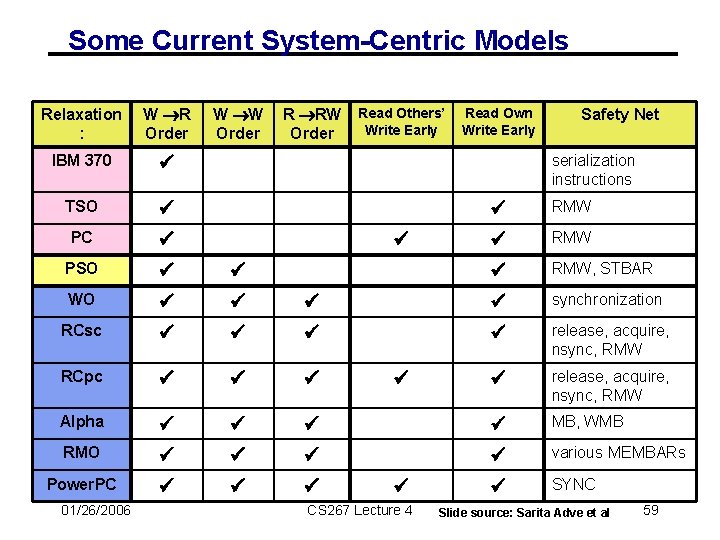

Violations of Sequential Consistency • Flag/data program is one example that relies on SC • Given coherent memory, all violations of SC based on reordering on independent operations are figure 8 s • See paper by Shasha and Snir for more details • Operations can be linearized (move forward time) if SC time (program order) 01/26/2006 P 0 write x P 1 write y read y P 2 read y write x CS 267 Lecture 4 56

Sufficient Conditions for Sequential Consistency • Processors issues memory operations in program order • Processor waits for store to complete before issuing any more memory operations • E. g. , wait for write-through and invalidations • Processor waits for load to complete before issuing any more memory operations • E. g. , data in another cache may have to be marked as shared rather than exclusive • A load must also wait for the store that produced the value to complete • E. g. , if data is in cache and update event changes value, all other caches much also have processed that update • There are much more aggressive ways of implementing SC, but most current commercial SMPs give up 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 Based on slide by Mark Hill et al 57

Classification for Relaxed Models • Optimizations can generally be categorized by • Program order relaxation: • • • Write Read Write Read, Write • Read others’ write early • Read own write early • All models provide safety net, e. g. , • A write fence instruction waits for writes to complete • A read fence prevents prefetches from moving before this point • Prefetches may be synchronized automatically on use • All models maintain uniprocessor data and control dependences, write serialization • Memory models differ on orders to two different locations 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 Slide source: Sarita Adve et al 58

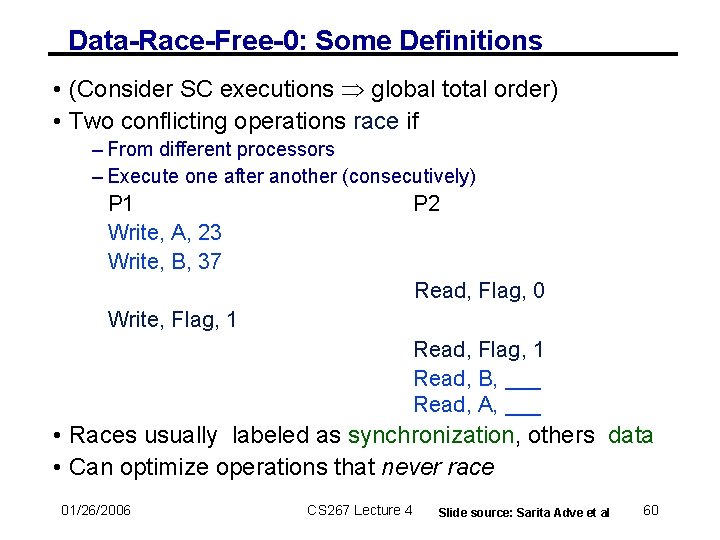

Some Current System-Centric Models Relaxation : W R Order W W Order IBM 370 TSO PC PSO WO RCsc RCpc R RW Order Read Others’ Write Early Read Own Write Early Safety Net serialization instructions RMW RMW, STBAR synchronization release, acquire, nsync, RMW Alpha MB, WMB RMO various MEMBARs Power. PC SYNC 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 Slide source: Sarita Adve et al 59

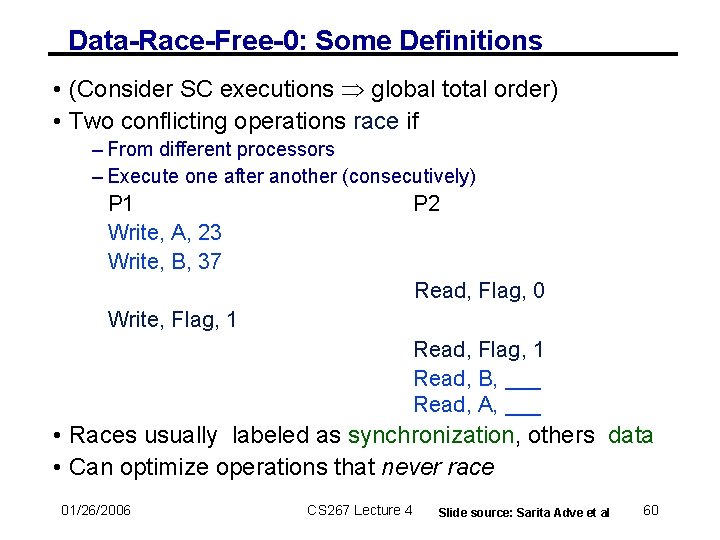

Data-Race-Free-0: Some Definitions • (Consider SC executions global total order) • Two conflicting operations race if – From different processors – Execute one after another (consecutively) P 1 Write, A, 23 Write, B, 37 P 2 Read, Flag, 0 Write, Flag, 1 Read, B, ___ Read, A, ___ • Races usually labeled as synchronization, others data • Can optimize operations that never race 01/26/2006 CS 267 Lecture 4 Slide source: Sarita Adve et al 60

Cache-Coherent Shared Memory and Performance