CS 259 2008 Algorithmic Symbolic Analysis John Mitchell

CS 259 2008 Algorithmic Symbolic Analysis John Mitchell

Protocol analysis methods u. Cryptographic reductions • Bellare-Rogaway, Shoup, many others • UC [Canetti et al], Simulatability [BPW] • Prob poly-time process calculus [LMRST…] u. Symbolic methods • Model checking – FDR [Lowe, Roscoe, …], Murphi [M, Shmatikov, …], • Symbolic search – NRL protocol analyzer [Meadows] • Theorem proving – Isabelle [Paulson …], Specialized logics [BAN, …]

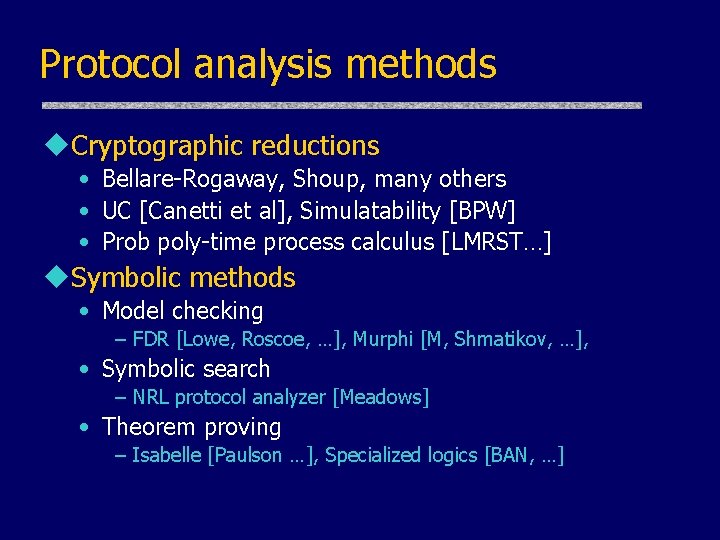

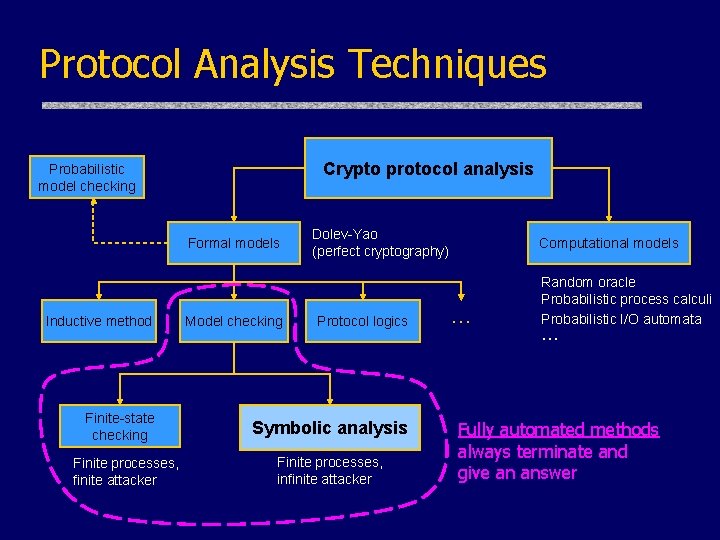

Protocol Analysis Techniques protocol security analysis Probabilistic model checking Formal models Inductive method Finite-state checking Finite processes, finite attacker Model checking Dolev-Yao (perfect cryptography) Protocol logics Symbolic analysis Finite processes, infinite attacker Computational models … Random oracle Probabilistic process calculi Probabilistic I/O automata … Fully automated methods always terminate and give an answer

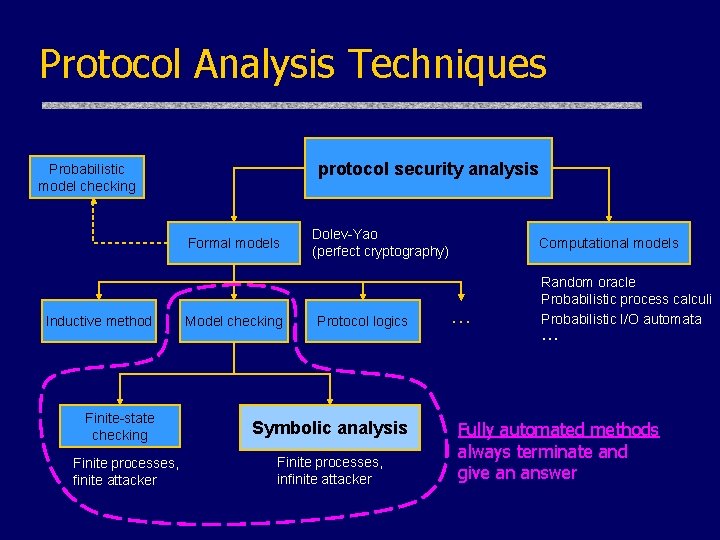

“The” Symbolic Model u. Messages are algebraic expressions • Nonce, Encrypt(K, M), Sign(K, M), … u. Adversary • Nondeterministic • Observe, store, direct all communication – Break messages into parts – Encrypt, decrypt, sign only if it has the key Example: K 1, Encrypt(K 1, “hi”) “hi” – Send messages derivable from stored parts

![Many formulations u Word problems [Dolev-Yao, Dolev-Even-Karp, …] • Each protocol step is symbolic Many formulations u Word problems [Dolev-Yao, Dolev-Even-Karp, …] • Each protocol step is symbolic](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/8a19dda6fd0e761156a02766c0359e47/image-5.jpg)

Many formulations u Word problems [Dolev-Yao, Dolev-Even-Karp, …] • Each protocol step is symbolic function from input message to output message; cancellation law dkekx = x u Rewrite systems [CDLMS] • Each protocol step is symbolic function from state and input message to state and output message u Logic programming [Meadows NRL Analyzer] • Each protocol step can be defined by logical clauses • Resolution used to perform reachability search u Constraint solving [Amadio-Lugiez, … ] • Write set constraints defining messages known at step i u Strand space model [MITRE] • Partial order (Lamport causality), reasoning methods u Process calculus [CSP, Spi-calculus, applied , …) • Each protocol step is process that reads, writes on channel • Spi-calculus: use for new values, private channels, simulate crypto

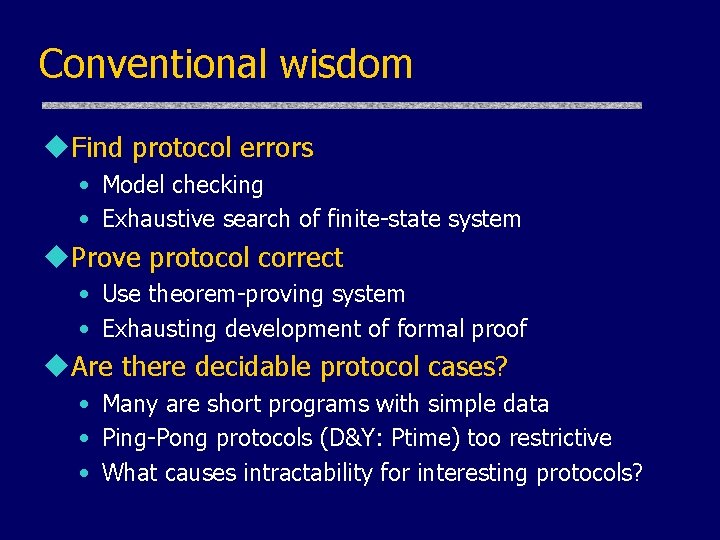

Conventional wisdom u. Find protocol errors • Model checking • Exhaustive search of finite-state system u. Prove protocol correct • Use theorem-proving system • Exhausting development of formal proof u. Are there decidable protocol cases? • Many are short programs with simple data • Ping-Pong protocols (D&Y: Ptime) too restrictive • What causes intractability for interesting protocols?

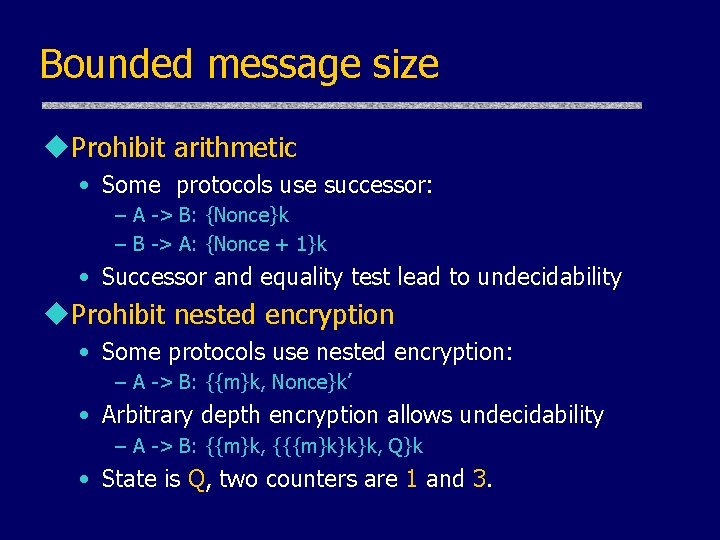

Bounded message size u. Prohibit arithmetic • Some protocols use successor: – A -> B: {Nonce}k – B -> A: {Nonce + 1}k • Successor and equality test lead to undecidability u. Prohibit nested encryption • Some protocols use nested encryption: – A -> B: {{m}k, Nonce}k’ • Arbitrary depth encryption allows undecidability – A -> B: {{m}k, {{{m}k}k}k, Q}k • State is Q, two counters are 1 and 3.

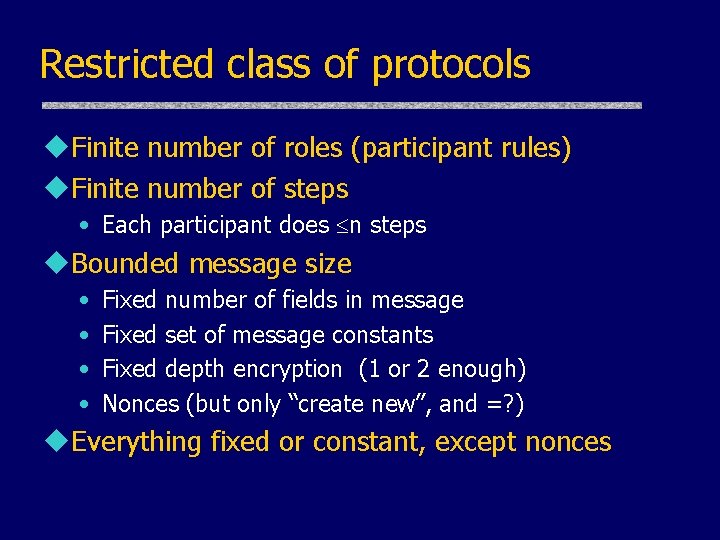

Restricted class of protocols u. Finite number of roles (participant rules) u. Finite number of steps • Each participant does n steps u. Bounded message size • • Fixed number of fields in message Fixed set of message constants Fixed depth encryption (1 or 2 enough) Nonces (but only “create new”, and =? ) u. Everything fixed or constant, except nonces

Still undecidable

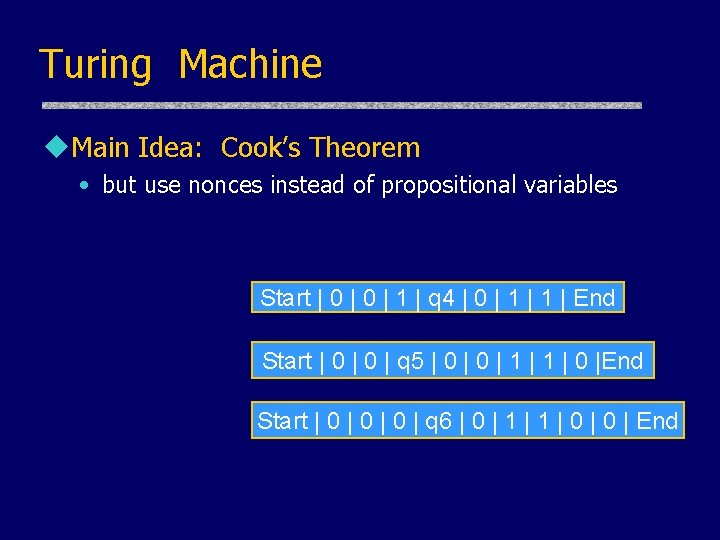

Turing Machine u. Main Idea: Cook’s Theorem • but use nonces instead of propositional variables Start | 0 | 1 | q 4 | 0 | 1 | End Start | 0 | q 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 |End Start | 0 | 0 | q 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | End

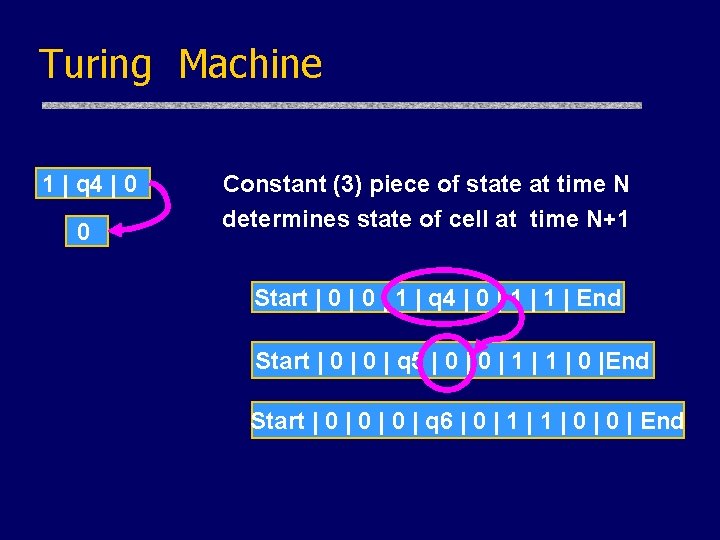

Turing Machine 1 | q 4 | 0 0 Constant (3) piece of state at time N determines state of cell at time N+1 Start | 0 | 1 | q 4 | 0 | 1 | End Start | 0 | q 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 |End Start | 0 | 0 | q 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | End

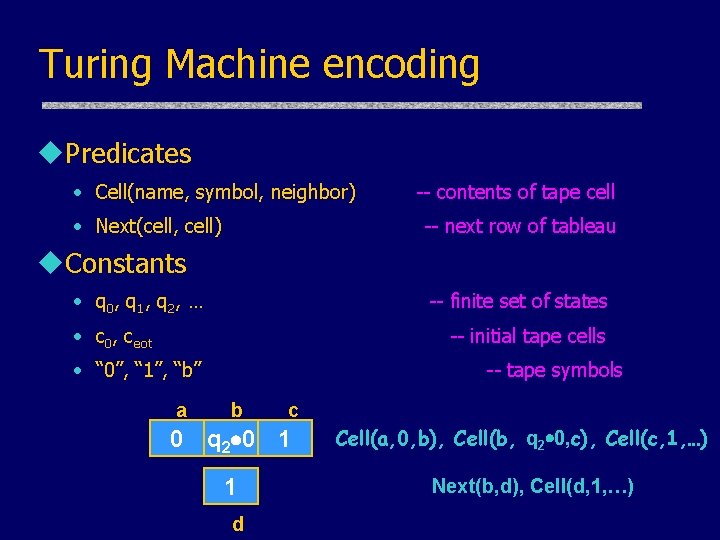

Turing Machine encoding u. Predicates • Cell(name, symbol, neighbor) • Next(cell, cell) -- contents of tape cell -- next row of tableau u. Constants • q 0 , q 1 , q 2 , … -- finite set of states • c 0, ceot -- initial tape cells • “ 0”, “ 1”, “b” a -- tape symbols b c 0 q 2 0 1 1 d Cell(a, 0, b), Cell(b, q 2 0, c), Cell(c, 1, …) Next(b, d), Cell(d, 1, …)

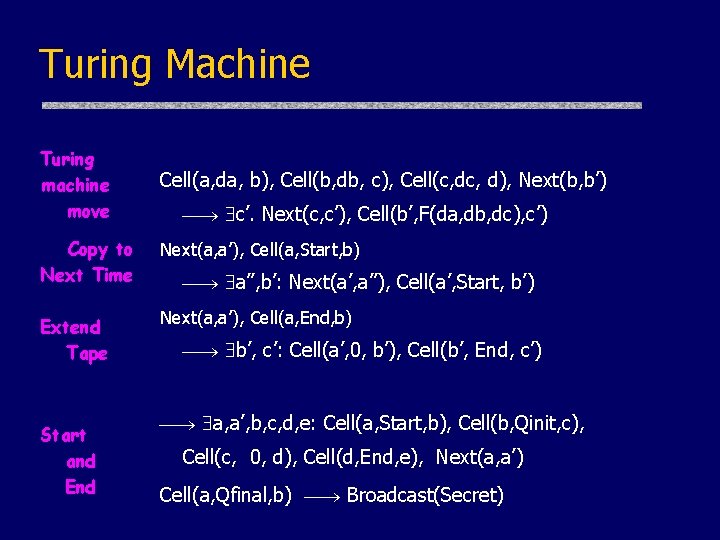

Turing Machine Turing machine move Cell(a, da, b), Cell(b, db, c), Cell(c, d), Next(b, b’) c’. Next(c, c’), Cell(b’, F(da, db, dc), c’) Copy to Next Time Next(a, a’), Cell(a, Start, b) Extend Tape Next(a, a’), Cell(a, End, b) Start and End a’’, b’: Next(a’, a’’), Cell(a’, Start, b’) b’, c’: Cell(a’, 0, b’), Cell(b’, End, c’) a, a’, b, c, d, e: Cell(a, Start, b), Cell(b, Qinit, c), Cell(c, 0, d), Cell(d, End, e), Next(a, a’) Cell(a, Qfinal, b) Broadcast(Secret)

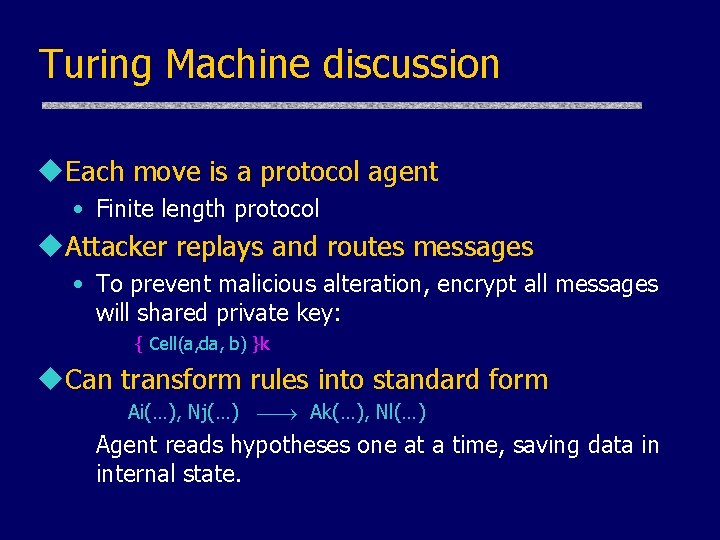

Turing Machine discussion u. Each move is a protocol agent • Finite length protocol u. Attacker replays and routes messages • To prevent malicious alteration, encrypt all messages will shared private key: { Cell(a, da, b) }k u. Can transform rules into standard form Ai(…), Nj(…) Ak(…), Nl(…) Agent reads hypotheses one at a time, saving data in internal state.

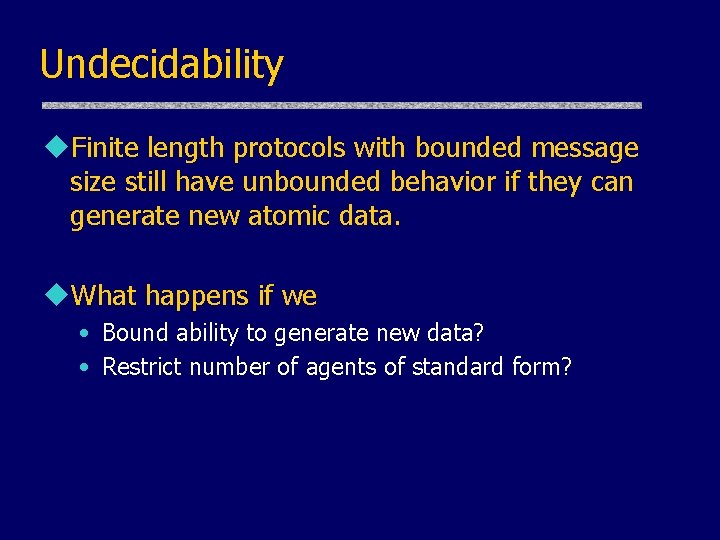

Undecidability u. Finite length protocols with bounded message size still have unbounded behavior if they can generate new atomic data. u. What happens if we • Bound ability to generate new data? • Restrict number of agents of standard form?

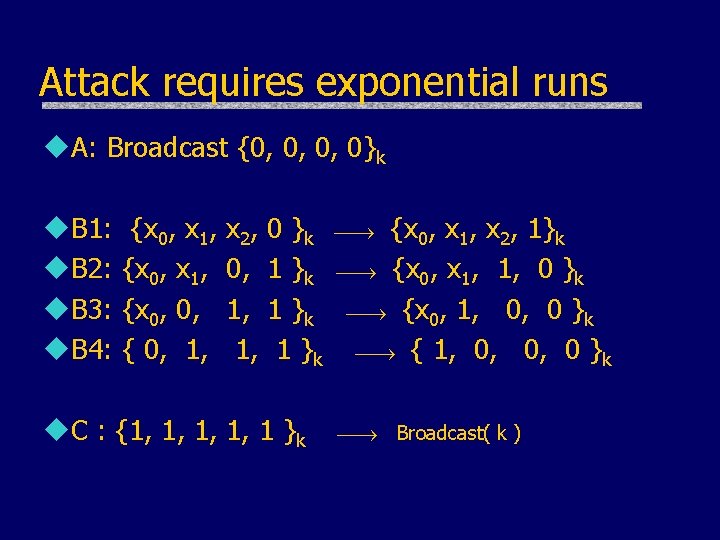

Attack requires exponential runs u. A: Broadcast {0, 0, 0, 0}k u. B 1: u. B 2: u. B 3: u. B 4: {x 0, x 1, {x 0, 0, { 0, 1, x 2, 0, 1, 1, 0 }k 1 }k u. C : {1, 1, 1 }k {x 0, x 1, x 2, 1}k {x 0, x 1, 1, 0 }k {x 0, 1, 0, 0 }k { 1, 0, 0, 0 }k Broadcast( k )

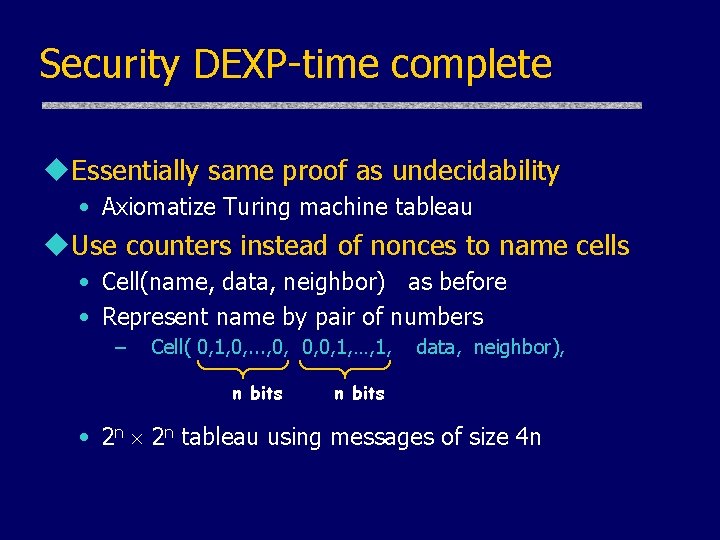

Security DEXP-time complete u. Essentially same proof as undecidability • Axiomatize Turing machine tableau u. Use counters instead of nonces to name cells • Cell(name, data, neighbor) as before • Represent name by pair of numbers – Cell( 0, 1, 0, . . . , 0, 0, 0, 1, …, 1, n bits data, neighbor), n bits • 2 n tableau using messages of size 4 n

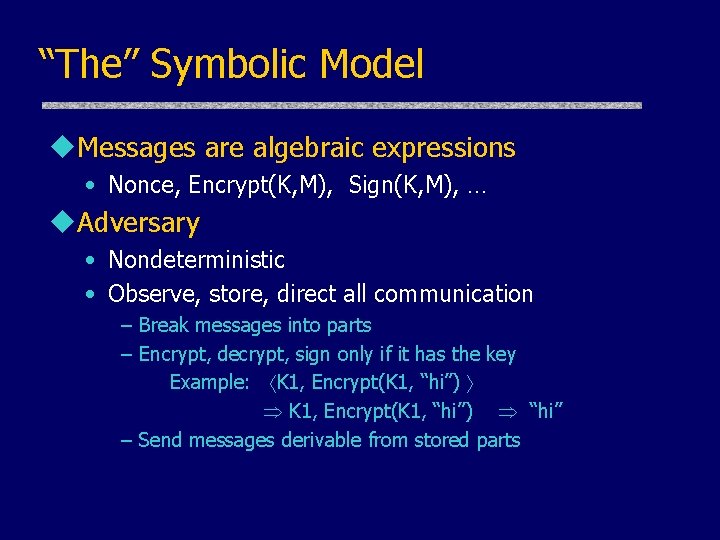

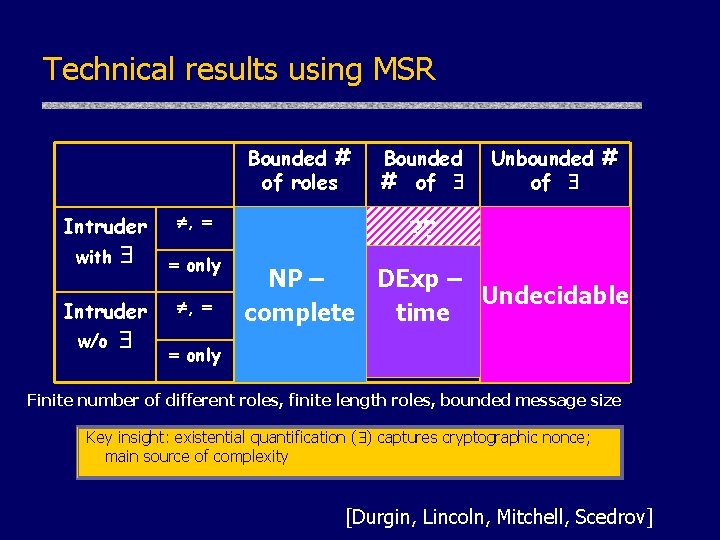

Technical results using MSR Bounded # of roles Intruder with Intruder w/o , only , Bounded # of Unbounded # of ? ? NP – DExp – Undecidable complete time only Finite number of different roles, finite length roles, bounded message size Key insight: existential quantification ( ) captures cryptographic nonce; main source of complexity [Durgin, Lincoln, Mitchell, Scedrov]

![Complexity results (see [Cortier et al]) Bounded # of sessions Unbounded number of sessions Complexity results (see [Cortier et al]) Bounded # of sessions Unbounded number of sessions](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/8a19dda6fd0e761156a02766c0359e47/image-19.jpg)

Complexity results (see [Cortier et al]) Bounded # of sessions Unbounded number of sessions Co-NP complete General: undecidable Without nonces With nonces Bounded msg length: DEXP-time complete undecidable Tagged: exptime Tagged: decidable One-copy: DEXP-time complete Ping-pong protocols: Ptime Additional results for variants of basic model (AC, xor, modular exp,

Protocol Analysis Techniques Crypto protocol analysis Probabilistic model checking Formal models Inductive method Finite-state checking Finite processes, finite attacker Model checking Dolev-Yao (perfect cryptography) Protocol logics Symbolic analysis Finite processes, infinite attacker Computational models … Random oracle Probabilistic process calculi Probabilistic I/O automata … Fully automated methods always terminate and give an answer

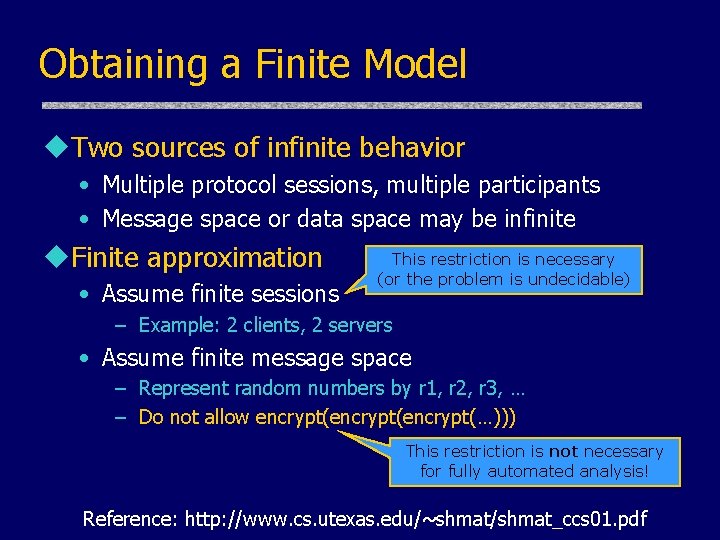

Obtaining a Finite Model u. Two sources of infinite behavior • Multiple protocol sessions, multiple participants • Message space or data space may be infinite u. Finite approximation • Assume finite sessions This restriction is necessary (or the problem is undecidable) – Example: 2 clients, 2 servers • Assume finite message space – Represent random numbers by r 1, r 2, r 3, … – Do not allow encrypt(encrypt(…))) This restriction is not necessary for fully automated analysis! Reference: http: //www. cs. utexas. edu/~shmat/shmat_ccs 01. pdf

![Strand Space Model [Thayer, Herzog, Guttman ’ 98] u. A strand is a representation Strand Space Model [Thayer, Herzog, Guttman ’ 98] u. A strand is a representation](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/8a19dda6fd0e761156a02766c0359e47/image-22.jpg)

Strand Space Model [Thayer, Herzog, Guttman ’ 98] u. A strand is a representation of a protocol “role” • Sequence of “nodes” • Describes what a participant playing one side of the protocol must do according to protocol specification u. A node is an observable action • “+” node: sending a message • “-” node: receiving a message u. Messages are ground terms • Standard formalization of cryptographic operations: pairing, encryption, one-way functions, …

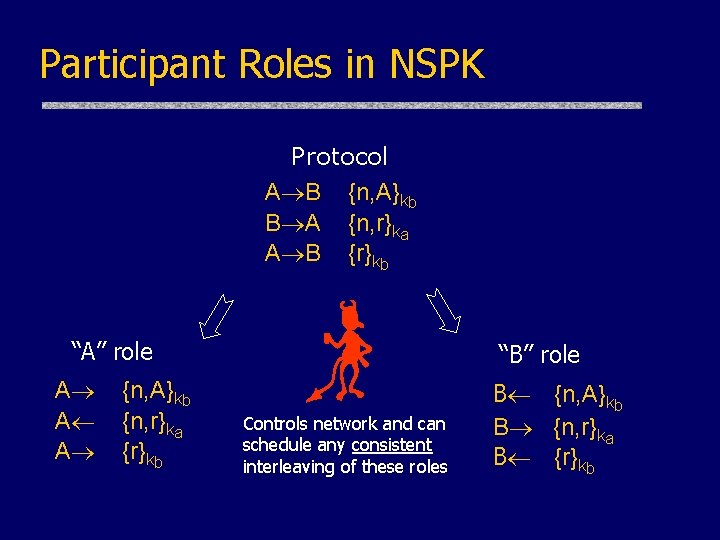

Participant Roles in NSPK Protocol A B {n, A}kb B A {n, r}ka A B {r}kb “A” role A A A {n, A}kb {n, r}ka {r}kb “B” role Controls network and can schedule any consistent interleaving of these roles B {n, A}kb B {n, r}ka B {r}kb

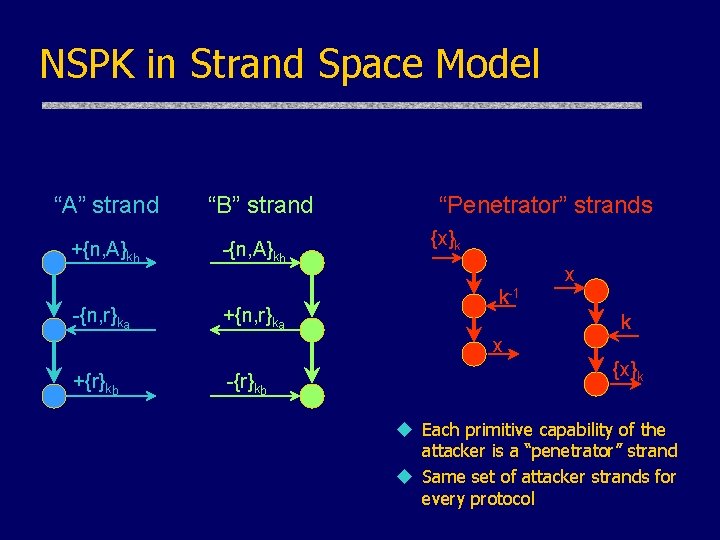

NSPK in Strand Space Model “A” strand +{n, A}kb -{n, r}ka “B” strand -{n, A}kb +{n, r}ka “Penetrator” strands {x}k x k-1 k x +{r}kb -{r}kb {x}k u Each primitive capability of the attacker is a “penetrator” strand u Same set of attacker strands for every protocol

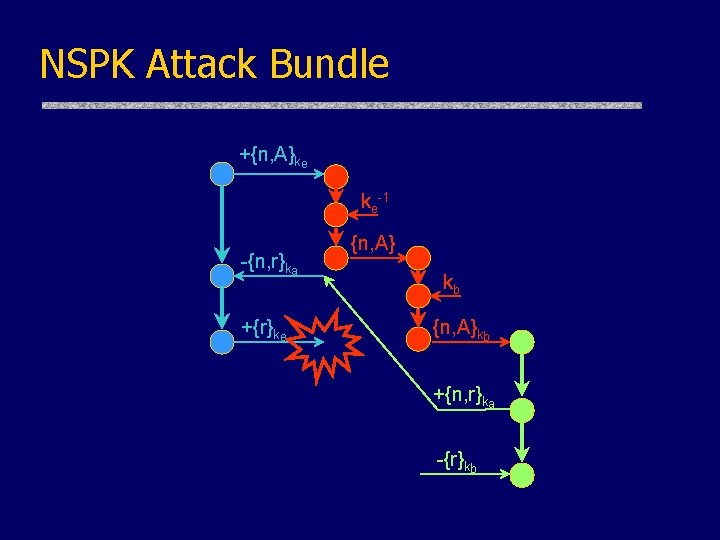

NSPK Attack Bundle +{n, A}ke ke-1 -{n, r}ka +{r}ke {n, A} kb {n, A}kb +{n, r}ka -{r}kb

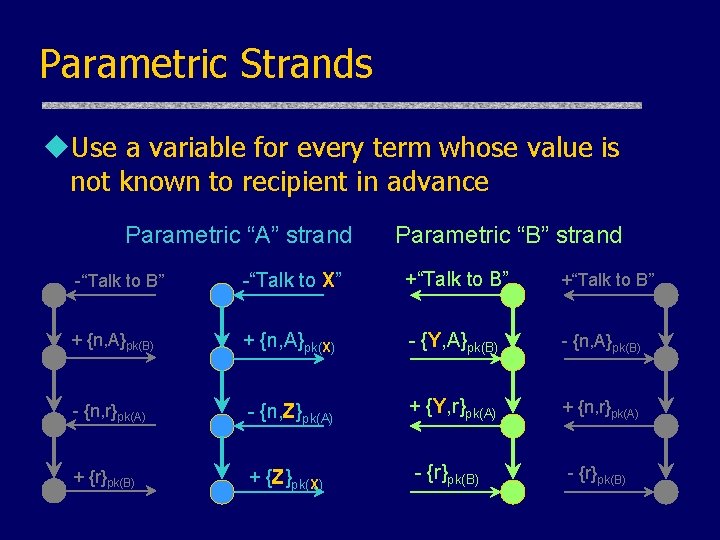

Parametric Strands u. Use a variable for every term whose value is not known to recipient in advance Parametric “A” strand Parametric “B” strand -“Talk to B” -“Talk to X” +“Talk to B” + {n, A}pk(B) + {n, A}pk(X) - {Y, A}pk(B) - {n, r}pk(A) - {n, Z}pk(A) + {Y, r}pk(A) + {n, r}pk(A) + {r}pk(B) + {Z}pk(X) - {r}pk(B)

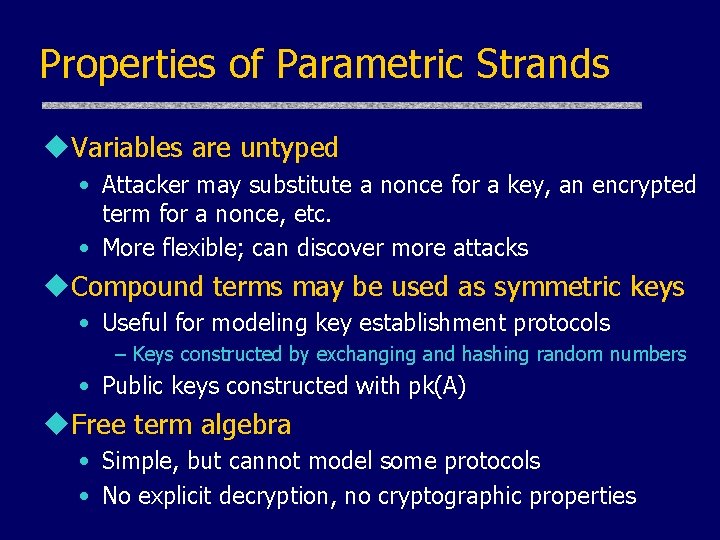

Properties of Parametric Strands u. Variables are untyped • Attacker may substitute a nonce for a key, an encrypted term for a nonce, etc. • More flexible; can discover more attacks u. Compound terms may be used as symmetric keys • Useful for modeling key establishment protocols – Keys constructed by exchanging and hashing random numbers • Public keys constructed with pk(A) u. Free term algebra • Simple, but cannot model some protocols • No explicit decryption, no cryptographic properties

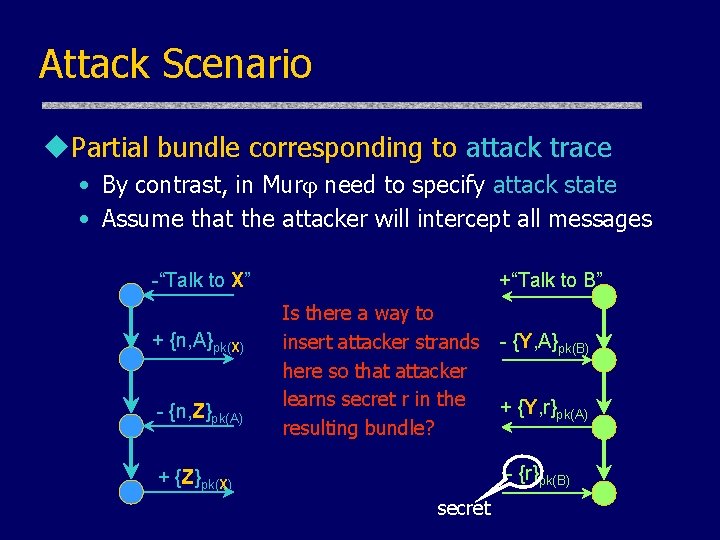

Attack Scenario u. Partial bundle corresponding to attack trace • By contrast, in Mur need to specify attack state • Assume that the attacker will intercept all messages -“Talk to X” + {n, A}pk(X) - {n, Z}pk(A) +“Talk to B” Is there a way to insert attacker strands here so that attacker learns secret r in the resulting bundle? - {Y, A}pk(B) + {Y, r}pk(A) - {r}pk(B) + {Z}pk(X) secret

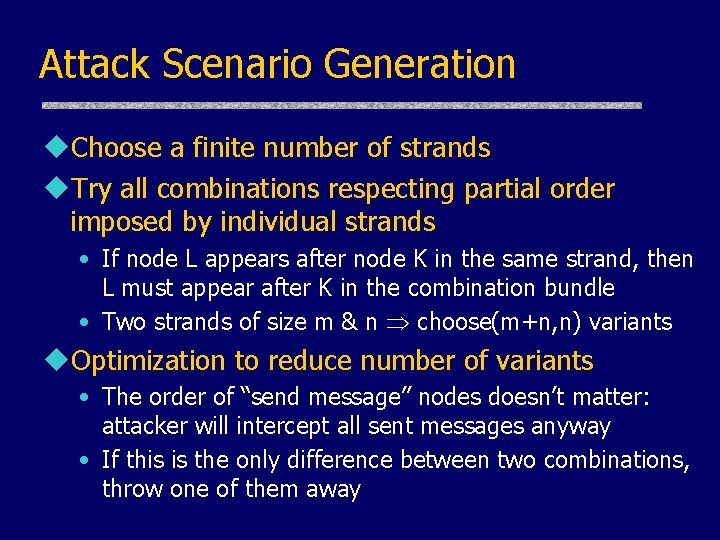

Attack Scenario Generation u. Choose a finite number of strands u. Try all combinations respecting partial order imposed by individual strands • If node L appears after node K in the same strand, then L must appear after K in the combination bundle • Two strands of size m & n choose(m+n, n) variants u. Optimization to reduce number of variants • The order of “send message” nodes doesn’t matter: attacker will intercept all sent messages anyway • If this is the only difference between two combinations, throw one of them away

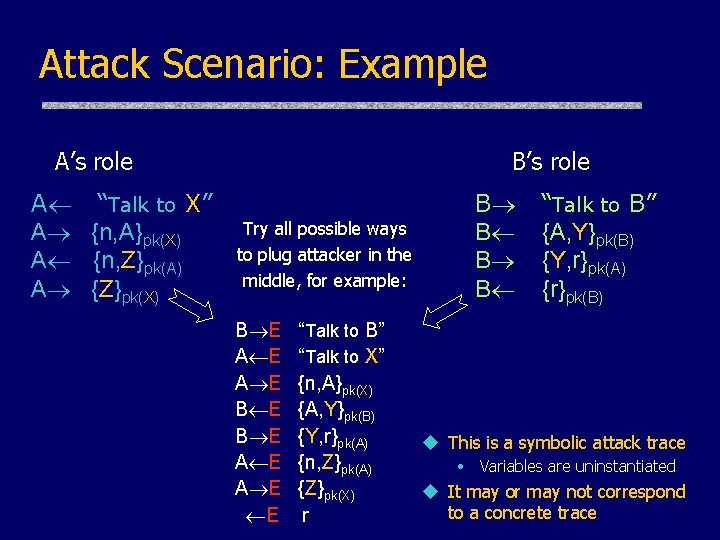

Attack Scenario: Example A’s role A “Talk to X” A {n, A}pk(X) A {n, Z}pk(A) A {Z}pk(X) B’s role Try all possible ways to plug attacker in the middle, for example: B E A E E “Talk to B” “Talk to X” {n, A}pk(X) {A, Y}pk(B) {Y, r}pk(A) {n, Z}pk(A) {Z}pk(X) r B B “Talk to B” {A, Y}pk(B) {Y, r}pk(A) {r}pk(B) u This is a symbolic attack trace • Variables are uninstantiated u It may or may not correspond to a concrete trace

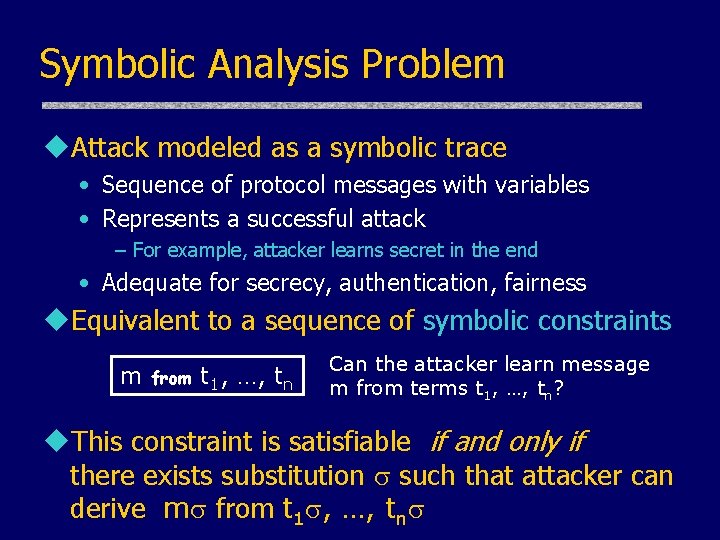

Symbolic Analysis Problem u. Attack modeled as a symbolic trace • Sequence of protocol messages with variables • Represents a successful attack – For example, attacker learns secret in the end • Adequate for secrecy, authentication, fairness u. Equivalent to a sequence of symbolic constraints m from t 1, …, tn Can the attacker learn message m from terms t 1, …, tn? u. This constraint is satisfiable if and only if there exists substitution such that attacker can derive m from t 1 , …, tn

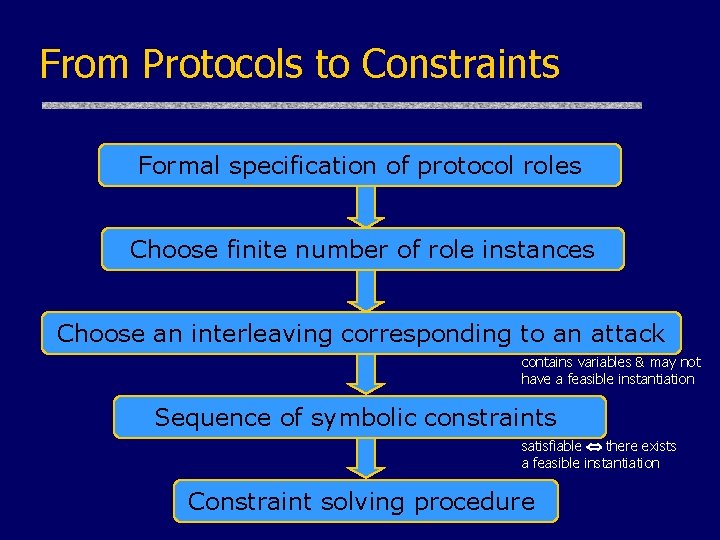

From Protocols to Constraints Formal specification of protocol roles Choose finite number of role instances Choose an interleaving corresponding to an attack contains variables & may not have a feasible instantiation Sequence of symbolic constraints satisfiable there exists a feasible instantiation Constraint solving procedure

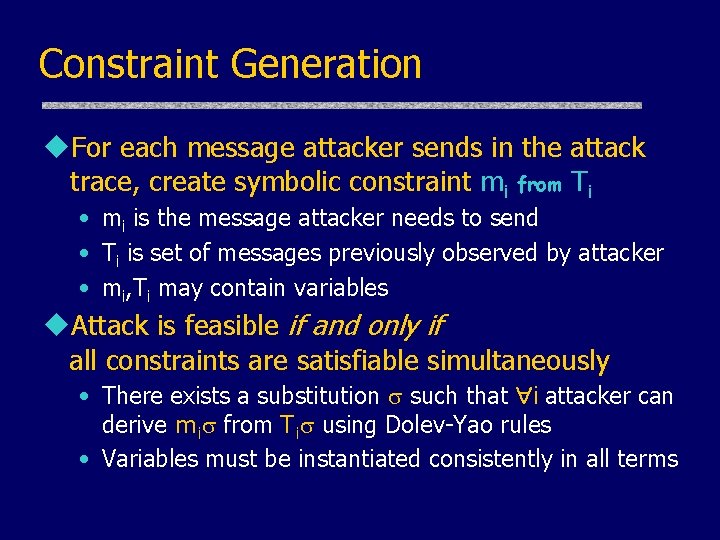

Constraint Generation u. For each message attacker sends in the attack trace, create symbolic constraint mi from Ti • mi is the message attacker needs to send • Ti is set of messages previously observed by attacker • mi, Ti may contain variables u. Attack is feasible if and only if all constraints are satisfiable simultaneously • There exists a substitution such that i attacker can derive mi from Ti using Dolev-Yao rules • Variables must be instantiated consistently in all terms

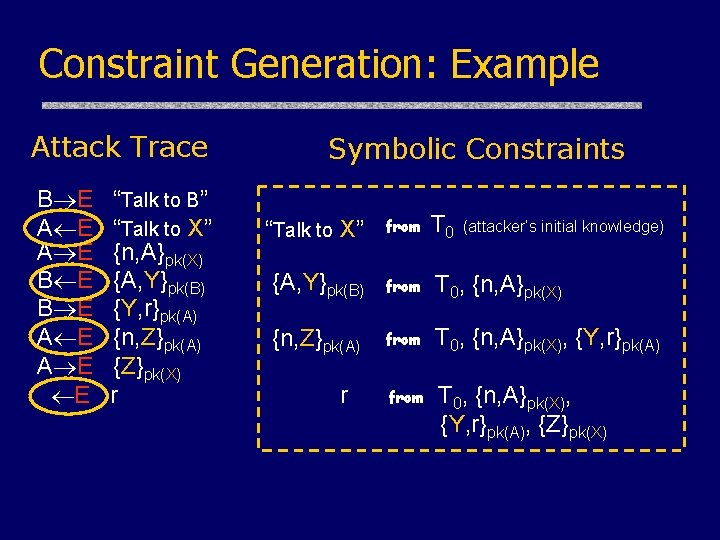

Constraint Generation: Example Attack Trace B E A E E “Talk to B” “Talk to X” {n, A}pk(X) {A, Y}pk(B) {Y, r}pk(A) {n, Z}pk(A) {Z}pk(X) r Symbolic Constraints “Talk to X” from T 0 {A, Y}pk(B) from T 0, {n, A}pk(X) {n, Z}pk(A) from T 0, {n, A}pk(X), {Y, r}pk(A), {Z}pk(X) r (attacker’s initial knowledge)

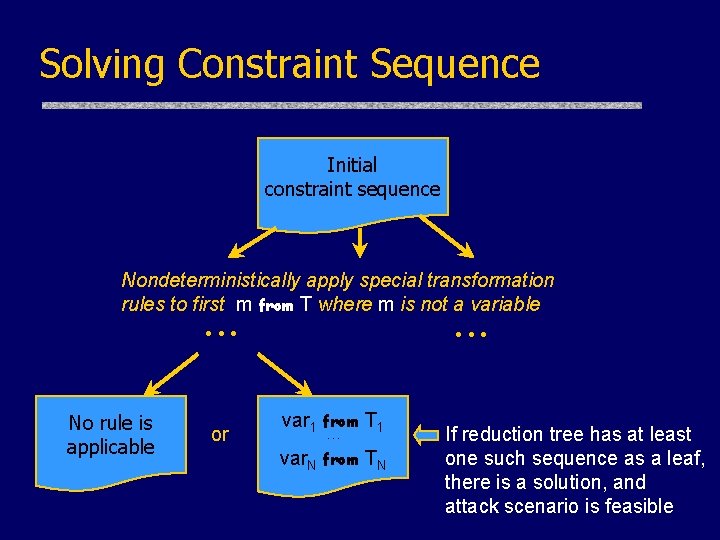

Solving Constraint Sequence Initial constraint sequence Nondeterministically apply special transformation rules to first m from T where m is not a variable • • • No rule is applicable or var 1 from T 1 • • • var. N from TN If reduction tree has at least one such sequence as a leaf, there is a solution, and attack scenario is feasible

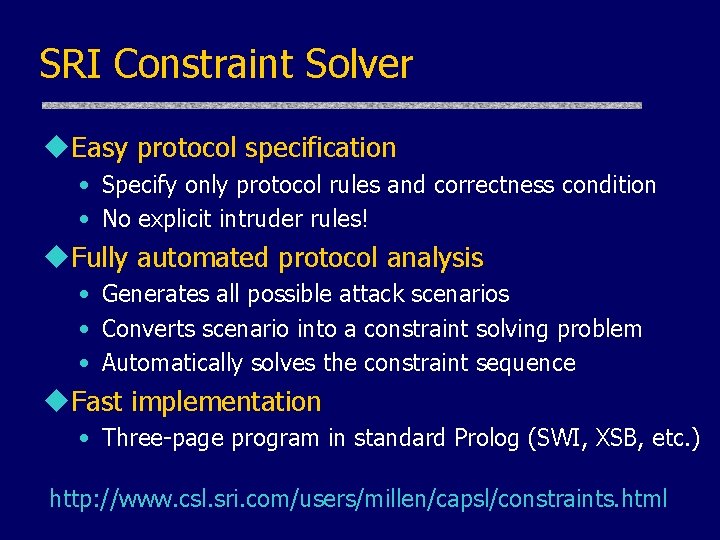

SRI Constraint Solver u. Easy protocol specification • Specify only protocol rules and correctness condition • No explicit intruder rules! u. Fully automated protocol analysis • Generates all possible attack scenarios • Converts scenario into a constraint solving problem • Automatically solves the constraint sequence u. Fast implementation • Three-page program in standard Prolog (SWI, XSB, etc. ) http: //www. csl. sri. com/users/millen/capsl/constraints. html

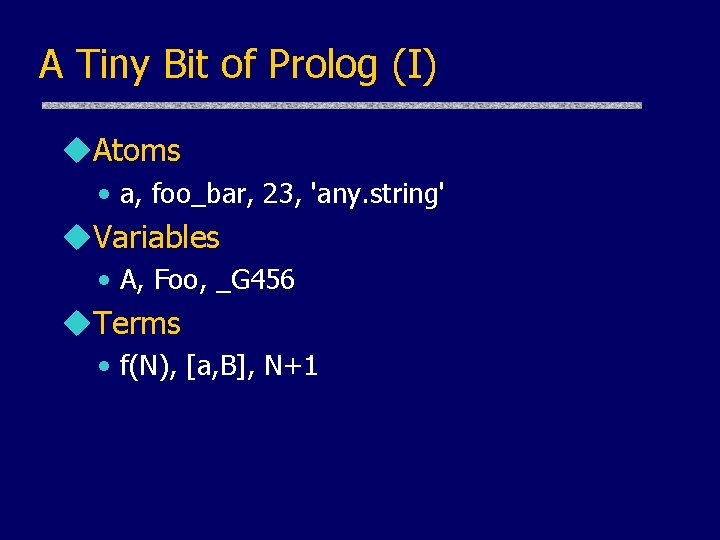

A Tiny Bit of Prolog (I) u. Atoms • a, foo_bar, 23, 'any. string' u. Variables • A, Foo, _G 456 u. Terms • f(N), [a, B], N+1

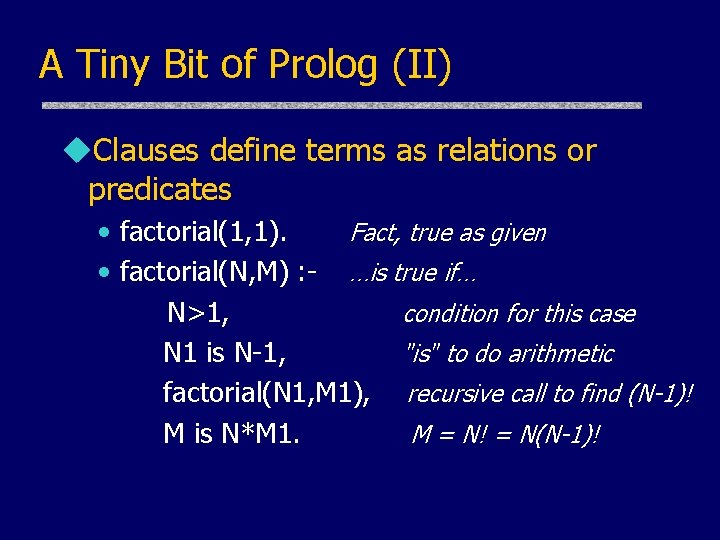

A Tiny Bit of Prolog (II) u. Clauses define terms as relations or predicates • factorial(1, 1). Fact, true as given • factorial(N, M) : - …is true if… N>1, condition for this case N 1 is N-1, "is" to do arithmetic factorial(N 1, M 1), recursive call to find (N-1)! M is N*M 1. M = N! = N(N-1)!

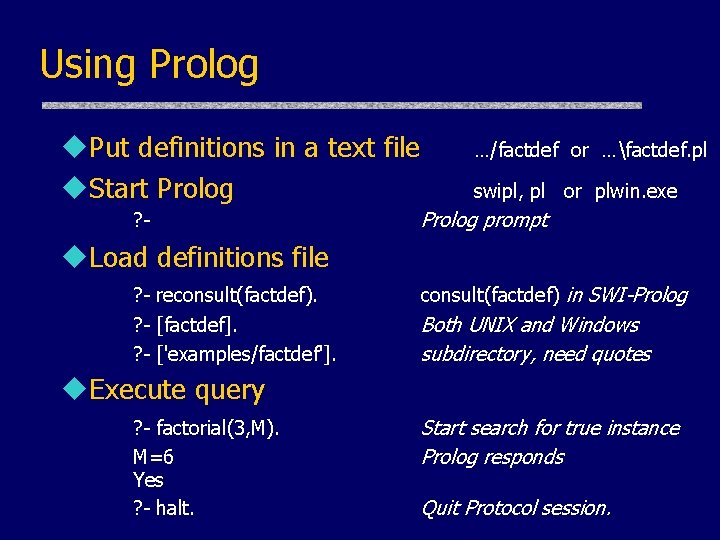

Using Prolog u. Put definitions in a text file u. Start Prolog ? - …/factdef or …factdef. pl swipl, pl or plwin. exe Prolog prompt u. Load definitions file ? - reconsult(factdef). ? - [factdef]. ? - ['examples/factdef']. consult(factdef) in SWI-Prolog Both UNIX and Windows subdirectory, need quotes u. Execute query ? - factorial(3, M). M=6 Yes ? - halt. Start search for true instance Prolog responds Quit Protocol session.

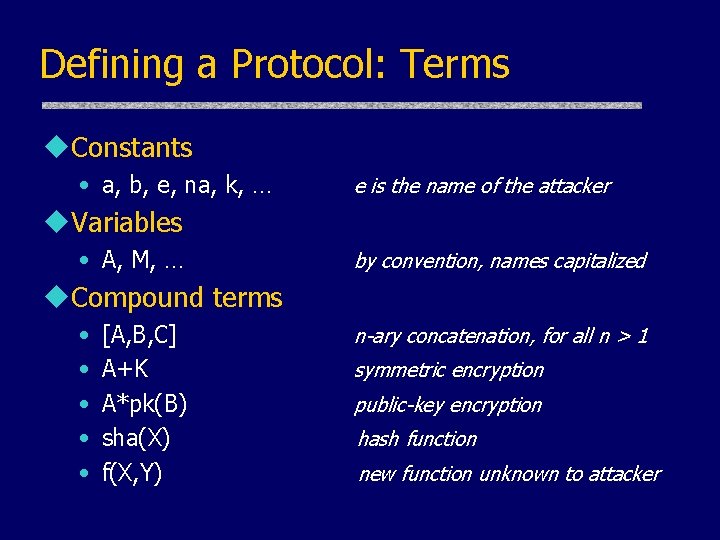

Defining a Protocol: Terms u. Constants • a, b, e, na, k, … e is the name of the attacker u. Variables • A, M, … by convention, names capitalized u. Compound terms • • • [A, B, C] A+K A*pk(B) sha(X) f(X, Y) n-ary concatenation, for all n > 1 symmetric encryption public-key encryption hash function new function unknown to attacker

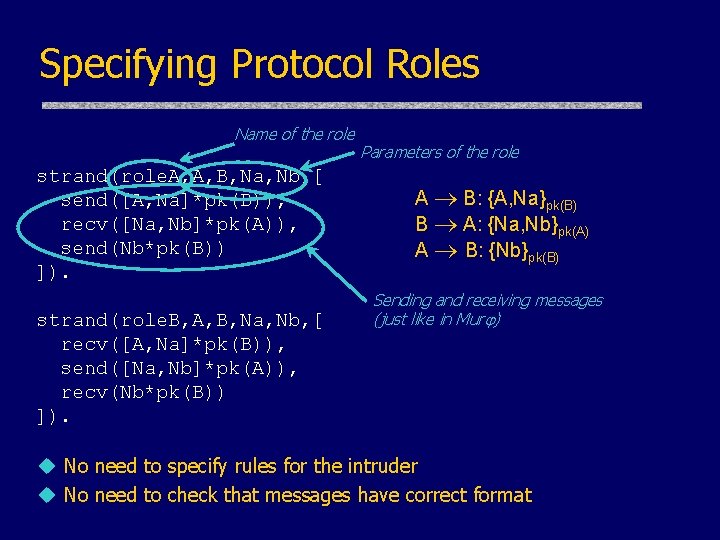

Specifying Protocol Roles Name of the role strand(role. A, A, B, Na, Nb, [ send([A, Na]*pk(B)), recv([Na, Nb]*pk(A)), send(Nb*pk(B)) ]). strand(role. B, A, B, Na, Nb, [ recv([A, Na]*pk(B)), send([Na, Nb]*pk(A)), recv(Nb*pk(B)) ]). Parameters of the role A B: {A, Na}pk(B) B A: {Na, Nb}pk(A) A B: {Nb}pk(B) Sending and receiving messages (just like in Mur ) u No need to specify rules for the intruder u No need to check that messages have correct format

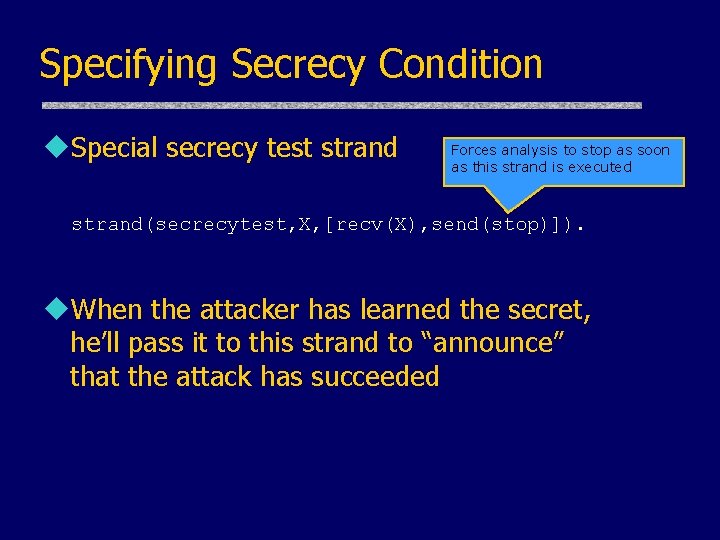

Specifying Secrecy Condition u. Special secrecy test strand Forces analysis to stop as soon as this strand is executed strand(secrecytest, X, [recv(X), send(stop)]). u. When the attacker has learned the secret, he’ll pass it to this strand to “announce” that the attack has succeeded

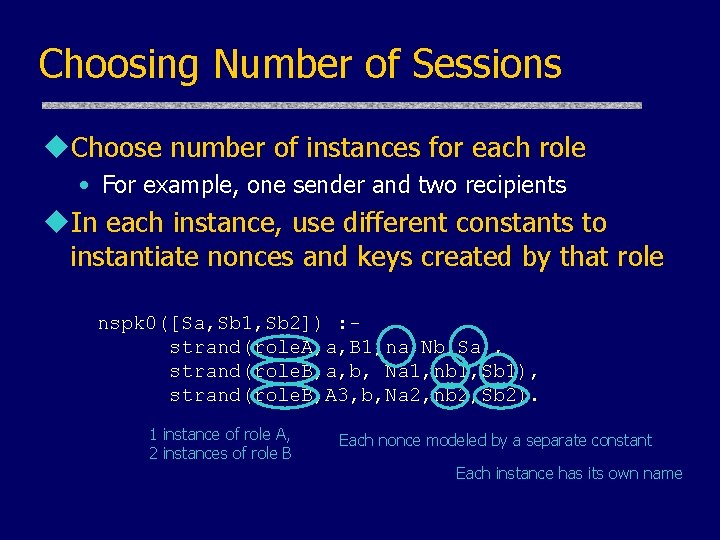

Choosing Number of Sessions u. Choose number of instances for each role • For example, one sender and two recipients u. In each instance, use different constants to instantiate nonces and keys created by that role nspk 0([Sa, Sb 1, Sb 2]) : strand(role. A, a, B 1, na, Nb, Sa), strand(role. B, a, b, Na 1, nb 1, Sb 1), strand(role. B, A 3, b, Na 2, nb 2, Sb 2). 1 instance of role A, 2 instances of role B Each nonce modeled by a separate constant Each instance has its own name

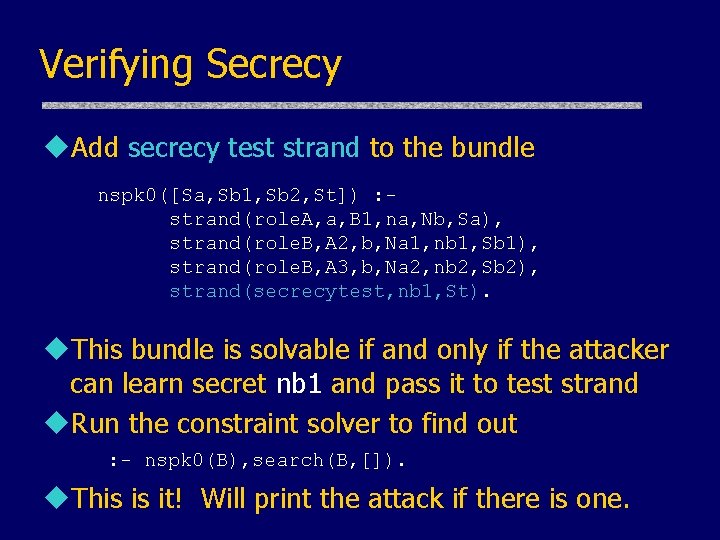

Verifying Secrecy u. Add secrecy test strand to the bundle nspk 0([Sa, Sb 1, Sb 2, St]) : strand(role. A, a, B 1, na, Nb, Sa), strand(role. B, A 2, b, Na 1, nb 1, Sb 1), strand(role. B, A 3, b, Na 2, nb 2, Sb 2), strand(secrecytest, nb 1, St). u. This bundle is solvable if and only if the attacker can learn secret nb 1 and pass it to test strand u. Run the constraint solver to find out : - nspk 0(B), search(B, []). u. This is it! Will print the attack if there is one.

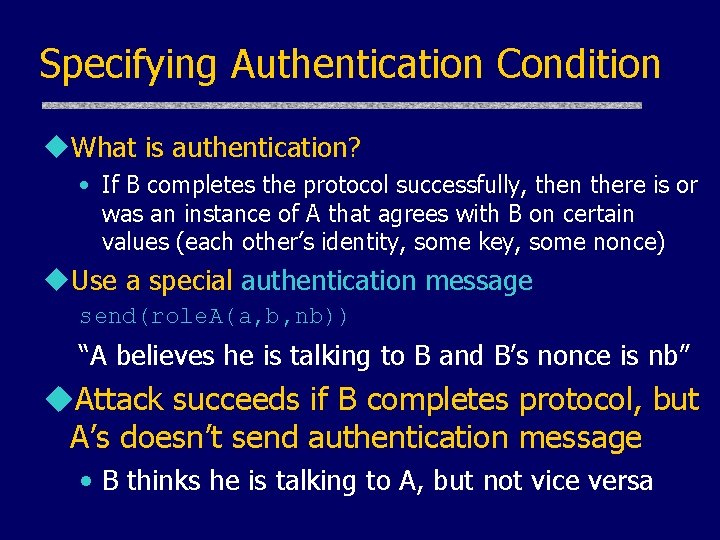

Specifying Authentication Condition u. What is authentication? • If B completes the protocol successfully, then there is or was an instance of A that agrees with B on certain values (each other’s identity, some key, some nonce) u. Use a special authentication message send(role. A(a, b, nb)) “A believes he is talking to B and B’s nonce is nb” u. Attack succeeds if B completes protocol, but A’s doesn’t send authentication message • B thinks he is talking to A, but not vice versa

![NSPK Strands for Authentication strand(role. A, A, B, Na, Nb, [ send([A, Na]*pk(B)), recv([Na, NSPK Strands for Authentication strand(role. A, A, B, Na, Nb, [ send([A, Na]*pk(B)), recv([Na,](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/8a19dda6fd0e761156a02766c0359e47/image-46.jpg)

NSPK Strands for Authentication strand(role. A, A, B, Na, Nb, [ send([A, Na]*pk(B)), recv([Na, Nb]*pk(A)), send(role. A(A, B, Nb)), send(Nb*pk(B)) ]). strand(role. B, A, B, Na, Nb, [ recv([A, Na]*pk(B)), send([Na, Nb]*pk(A)), recv(Nb*pk(B)), send(role. B(A, B, Na)) ]). A announces who he thinks he is talking to B announces who he thinks he is talking to

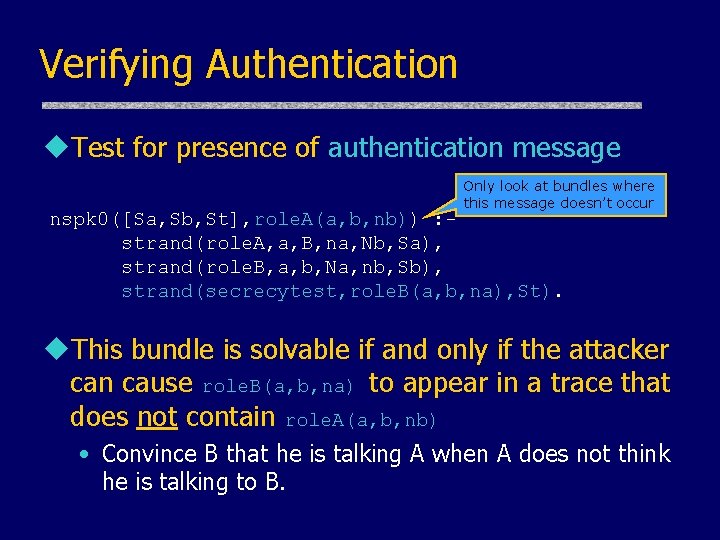

Verifying Authentication u. Test for presence of authentication message Only look at bundles where this message doesn’t occur nspk 0([Sa, Sb, St], role. A(a, b, nb)) : strand(role. A, a, B, na, Nb, Sa), strand(role. B, a, b, Na, nb, Sb), strand(secrecytest, role. B(a, b, na), St). u. This bundle is solvable if and only if the attacker can cause role. B(a, b, na) to appear in a trace that does not contain role. A(a, b, nb) • Convince B that he is talking A when A does not think he is talking to B.

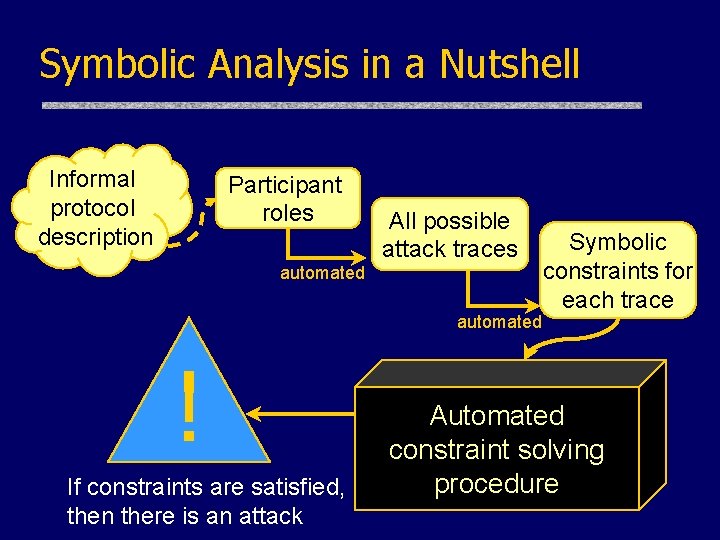

Symbolic Analysis in a Nutshell Informal protocol description Participant roles All possible attack traces automated ! If constraints are satisfied, then there is an attack Symbolic constraints for each trace Automated constraint solving procedure

- Slides: 48